95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 17 February 2025

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2025.1541887

This article is part of the Research Topic The Politics of Crises - The Crisis of Politics in Central and Eastern Europe View all 10 articles

The prime minister, and thus indirectly the government, had a strong position in the Hungarian chancellor-type parliamentary system established at the time of the transition to democracy. Since the 1990s, as a result of the de facto presidentialisation, this initially stronger position has been continuously and systematically strengthened. Since the balance of power between the legislature and the executive has shifted significantly in favour of the later. All these developments make it particularly interesting to describe the extraordinary measures taken in recent years and to assess their impact on the already modified system of separation of powers. Based on the relevant legislation, statistics and practice, the manuscript discusses and analyses how the congestion of legally and politically overlapping periods of emergency and special legal order has affected the already changed balance of power between the government and parliament, to what extent and how it has influenced the instruments used by the government for decision-making, and the dynamics of parliamentary work.

There is a consensus in both Hungarian and foreign academic literature that the power available to the Prime Minister (PM) has been steadily increasing, and that the PM’s room for manoeuvre in the legal and political dimensions has been expanding in Hungary over the past decades.

This research examines how, and to what extent, the prolonged state of emergency since 2015 has contributed to this trend.

During a state of emergency, the executive is expected to play a more central role vis-à-vis parliament and other political institutions. A state of emergency requires a massive delegation of power to the executive, as it is the only branch of power that has sufficient information to make the necessary decisions in the shortest possible time (Ginsburg and Versteeg, 2021, p. 1499).

The study examines what happens in a significantly prolonged state of emergency such as the one in Hungary, taking into account the fact that both the position of the government and that of the PM were explicitly strengthened in Hungary long before the first state of emergency was introduced.

The hypothesis of the study is that the degree of the government’s strengthening (including the PM) in relation to parliament, resulting from the continuous and successive periods of states of emergency and special legal orders introduced in the last decade due to a series of crises (migration crisis, health crisis, economic crisis, war crisis), is caused by the level of dominance of the executive (including the PM) prior to the crises. The de facto presidentialisation of the Hungarian political system, which has been observed and developed since the beginning of the 1990s (Körösényi, 2001; Mandák, 2014), has mainly determined the further strengthening of the position of the Hungarian government and the PM in the last decade (Kosztrihán, 2024; Mandák, 2015; Musella, 2019; Stumpf, 2015, 2020; Stumpf and Kis, 2023; Tóth, 2017, 2018, 2022).

The article is structured as follows: first, the conceptual and theoretical framework describing de facto presidentialisation is discussed, then the methods are presented, explaining the studied indicators, followed by the analysis and the results. The article ends with concluding remarks.

The theoretical framework of the research is de facto presidentialisation. The majority of studies analysing the strengthening of the government and the PM as a result of the state of emergency or the special legal order introduced along the lines of COVID-19 use the concept of executive aggrandisement (Bromo et al., 2024; Bolleyer and Salát, 2021; Edgar, 2024; Farrell et al., 2024; Guasti and Bustikova, 2022). According to Bermeo (2016), executive aggrandisement is a temporary reduction in the influence and oversight capacity of formal institutions vis-à-vis the executive. In my opinion, the concept of executive aggrandisement would not be the most appropriate theoretical framework for the case of Hungary, because this concept is used only to describe temporary changes, the longest time frame studied by executive aggrandisement was 4–5 years (Khaitan, 2019; Khaitan, 2020), while executive empowerment is a decades-long phenomenon in the Hungarian political system, as this research will explain.

Presidentialisation of politics means that some parliamentary democracies have become more presidential in their political attitudes without changing their formal institutional structure (Poguntke, 2000; Poguntke and Webb, 2005). De facto presidentialisation makes the operating logic of the political system more presidential without formally changing the institutional system and the constitution (Elia, 2006). The de facto presidentialisation of politics appears in three areas: the executive, the party and the electoral arena. The paper analyses the changes in the Hungarian executive arena with a special focus on the decade of crises and its impact on the presidentialisation of Hungarian politics.

The Hungarian political science literature started to deal with the phenomenon of presidentialisation and its signs in the Hungarian government in 2001, when András Körösényi (2001) published the first article on the subject. Körösényi identified presidentialisation with the rearrangement of power within the executive, the change in the style of politics, the nature of political competition and the operating logic of the entire political system. At the same time, he emphasised that the concept of presidentialisation should not be interpreted strictly in constitutional terms, but should be used as an analogy and metaphor. The publication triggered a major academic debate at the time (Ilonszki, 2002; Csizmadia, 2001; Tőkés, 2001; Körösényi, 2003; Enyedi, 2001), but shortly afterwards the issue lost its centrality until 2014. After the reforms of the second Orbán government concerning the organisation and functioning of the government, the issue returned to the centre of political science literature (Kosztrihán, 2024; Mandák, 2015; Musella, 2019; Stumpf, 2020; Stumpf and Kis, 2023; Tóth, 2017, 2018, 2022).

In my understanding, presidentialisation is the concentration of formal and informal power in the hands of the PM and the government he or she controls, which consists of an increase in the number of rights, powers and instruments. This kind of centralisation, as we will see in later sections, has been fundamentally brought about by changes in the decision-making processes of international politics, the growth and complexity of the role of the state, and the erosion of social fault lines.

At the level of the executive, the presidentialisation of politics means a weakening of the collective character of government and a strengthening of the power of the PM. De facto presidentialisation increases the resources available to the PM, as well as his autonomy within his party and the entire political executive, and develops the personalisation of electoral processes.

The PM’s increased power derives from two things: an increase in the number of areas he or she controls and an increase in his or her ability to successfully confront political actors who hold different views from his or her own. In the executive, the PM’s power is based on a combination of two factors: the total number of areas in which he can make decisions independently, and the extent to which he can fend off opposition to his initiative in other areas where he does not have unlimited decision-making potential. According to this logic, the PM’s power can be strengthened by increasing the number of policy areas in which he can decide independently and by increasing his ability to counter opposition from other political actors. This latter capacity is based on the following resources: his formal power; his staff; the extent of his financial resources; his ability to set and shape the agenda; the extent of his control over communication; and his increasing ability to participate in international negotiations and decision-making since most decisions taken in such fora can no longer be renegotiated at the national level, but only ratified (Poguntke and Webb, 2005).

The increase of areas in which the head of the executive has individual decision-making power may result from an increase in the formal power granted to the PM or from a more frequent use of the personal power of the head of the executive. The institutional position of the head of the executive in the nation state is fundamentally determined by two types of relationship: the balance of power between the executive and the legislature, and the balance of power within the executive, i.e., the relationship between the PM, ministers and specific members of the government (Mandák, 2014, p. 43–44).

The research relies on a number of different indicators to measure the degree of de facto presidentialisation at the executive level, focusing on the strengthening of the PM within the government and the strengthening of the government vis-à-vis parliament.

The presidentialisation of politics can be seen through numerous changes at the level of the PM, the cabinet and in the relationship between parliament and government. The conceptualisation of these phenomena is crucial because these conceptual criteria will be used to examine the events in the country study later in this paper. The changes do not have the same weight in all cases (Mandák, 2015); and it is important to note that, due to the limitations of this article, we focus only on those criteria that could be influenced by the decisions and changes made by the state of emergency and the special legal order, both in the case of strengthening the government vis-à-vis the parliament and in the case of changing the relations between the PM and the government.

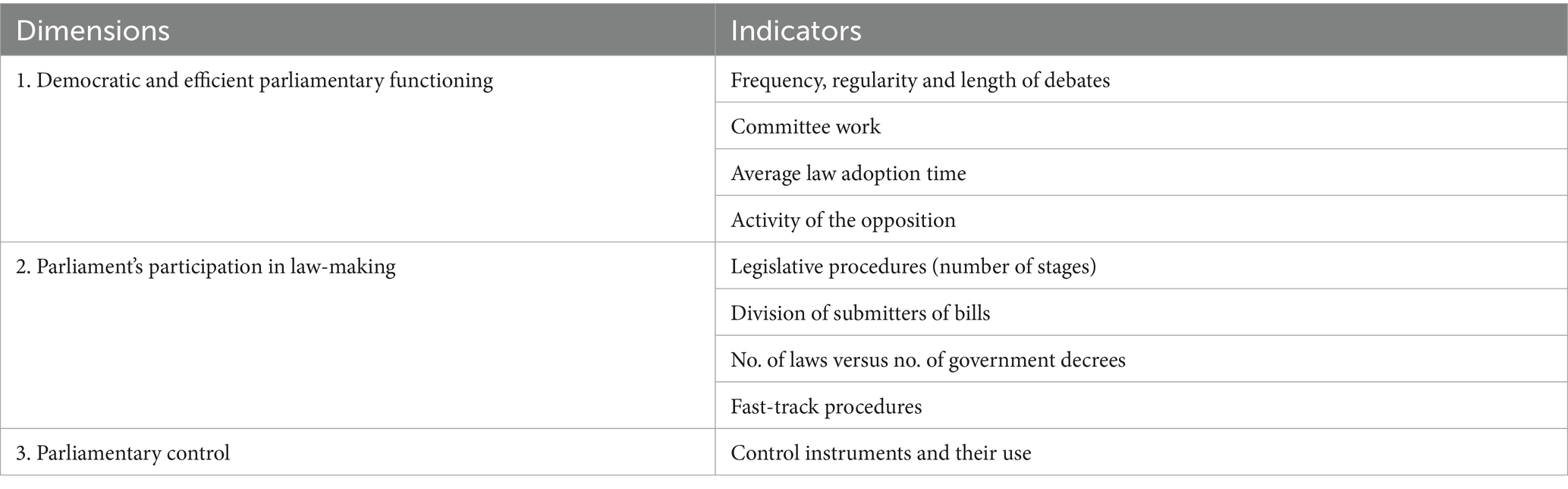

I have prioritised the following list of criteria, dividing them into two main categories: the first examines the strengthening of the government vis-à-vis parliament, while the second includes the indicators measuring the increase in the PM’s powers and degree of autonomy within the government. All dimensions of these two categories are examined through qualitative analysis (Tables 1–3).

Table 2. Indicators of the dimensions of the strengthening of the government vis-à-vis parliament (author’s own elaboration).

Table 3. Indicators of the dimensions of the PM’s empowerment within the government (author’s own elaboration).

The criteria of presidentialisation with regard to the change in the relationship between the PM and the government are organised in two dimensions, the first being the institutional body(ies) directly led and controlled by the PM and their position in political decision-making, while the second dimension refers to the possible counterweights within the cabinet (Mandák, 2015).

In order to analyse the extent to which the above-mentioned changes can be observed in Hungary, I examine the constitutions, the rules of procedure and the regulations on governments, the rules on states of emergency and special legal orders, and the practical functioning of everyday politics through parliamentary statistics.

It is beyond the scope of the research to examine all the indicators. Of the political institutions that can act as a counterweight to the government and the PM, I will focus only on the parliament. This decision is justified by the limitations of the scope of the study and by the fact that it is responsible for ex ante and ex post control of the executive, i.e., it can act as a veto player and supervisor of legislative outcomes. For further analysis of the other counterweight institutions (see Gárdos-Orosz, 2024; Paczolay, 2015; Steuer, 2024; Szente, 2015).

This section briefly describes the main elements of the political system established at the time of and after the democratic transition in 1989–1990, as well as the state of emergency and special legal order as of 2015.

In the new democratic political system that emerged from the transition to democracy, the PM had a particularly strong position when the chancellor-type parliamentary system was introduced in 1990. The main framework of the system has remained essentially unchanged over the past decades, but the actors, institutions and rules of the political system have changed significantly.

The main features of the parliamentary form of government introduced in 1989–1990, which aimed to create a consensual democracy as defined by Lijphart (1999), included a unicameral parliament, a government responsible to parliament, a basically monist executive headed by the government and the PM, an independent government from parliament and vice versa,1 a relatively high number of two-thirds laws (for more than 30 subjects), and the indirect election of the President of the Republic (Körösényi et al., 2003; Körösényi, 2006; Smuk, 2011; Jakab, 2009; Küpper and Térey, 2009; Szente, 2008).

Unlike in other parliamentary systems, the President of the Republic played a relatively minor role in the formation of the government and had limited power to dissolve the National Assembly, but his constitutional and political veto power allowed him to act as a counterweight to the government.

Other important features include the broad powers of the Constitutional Court, the institution of ombudsmen (Körösényi et al., 2003, p. 360) and the independence of the Public Prosecutor’s Office from the government (Körösényi, 2006, p. 10–11).

In terms of government relations, an important pillar of the system was the strong position of the PM, the formal equality of ministers within the cabinet, the institution of ministerial responsibility and a model of state governance based on the principle of separation of politics and administration (Müller, 2011, p. 21–22).

The strengthened position of the PM, based on his constitutional rights were to determine the government programme, to choose his deputy, to form the government and to chair cabinet meetings.2 The PM was given a policy-making role, but the system based on the principle of separation of powers also introduced a number of checks and balances that made the PM’s power controllable (Tölgyessy, 2006, p. 114–116). Overall, the PM had a government rather than the government having a leader (Paczolay, 2007; Romsics, 2010).

Although a number of counterbalancing institutions were added to the political system in the early 1990s, they saw a gradual and steady decline in their potential in the first two decades, while at the same time the PM continued to be strengthened.

It is also important to briefly outline the political context of the last 15 years, which confirms and in some cases reinforces the effects of presidentialisation in the case of several indicators.

With the exception of a 3-year period, Fidesz has had a two-thirds majority for the last 15 years,3 and a predominant party system has emerged, which represents a significant power potential that further increases the impact of the phenomenon of presidentialisation.

Since 2010, there has been no need to form a coalition after election,4 so in practice Fidesz and its leader, Viktor Orbán, have been able to decide alone on the structure and composition of the government. The executive role of the governing party group(s) has informally shifted the balance of power between the legislature and the executive towards the executive and its leader. In this situation, Hungary entered the so-called decade of crises, initiated by the declaration of a state of emergency due to the migration crisis in 2015 (Gellén, 2024).5

Then, on 11 March 2020, the Hungarian government declared a state of emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic, referring to the emergency chapter of the Fundamental Law (FL), and approved an authorisation act6 granting the government broad powers to manage the situation. It was the first national emergency since the democratic transition.

It soon became clear that the special legal regime would not last for a short period of time, measurable in weeks or months—at the time of writing it has been in force for 4 years, albeit with interruptions—although from 25 May 2022 the reason for the declaration of a state of emergency has been the armed conflict and humanitarian disaster on the territory of Ukraine (Szente and Gárdos-Orosz, 2022).

The FL and its amendments, especially the 6th, 9th, and 10th amendments, significantly changed the previous special legal order, and by November 2022, the solution of blurring the boundaries between the branches of power was abolished and the government became the sole crisis manager.

The ninth amendment formally increased the role of the government in the special legal order, stating as a general rule that the government may issue decrees in all situations of the special legal order, thus abolishing the former Council of Defence and removing the right of the President of the Republic to issue decrees (Horváth, 2021).7

The tenth amendment, adopted on 24 May 2022,8 was due to the state of emergency in response to the war in Ukraine; it redefined the rules of the state of emergency by adding a humanitarian catastrophe or war in a neighbouring country as a prerequisite for a state of emergency. Following this declaration, the Hungarian parliament again gave the government blanket approval to rule by emergency decree until 1 November 2022. The declaration of a state of emergency in response to a humanitarian crisis abroad is unique in modern constitutional democracies (Erdős and Tanács-Mandák, 2023, p. 557–559). In this context, it is noteworthy that after the declaration of a new state of emergency, the government issued several emergency decrees that had nothing to do with the humanitarian situation. Instead of addressing other issues, these decrees were implemented to deal with a growing economic and financial crisis, in total the government issued almost 200 emergency decrees. The aim of the emergency decrees was not to deal with a real crisis, but to circumvent parliamentary control by maintaining a model of rule by decree (Mészáros, 2024, p. 306).

Over the past 30 years, the Hungarian Parliament has maintained its place in the state structure as the main representative body of the people, although significant changes have occurred in parliamentary practice. In examining the relationship between parliament and government, the paper focuses on three dimensions, analysing the evolution of the rules of procedure and longitudinal parliamentary statistics.

The first dimension examines the democratic functioning of the Hungarian National Assembly: the frequency, regularity and length of debates; the efficiency of decision-making: the average time taken to pass legislation, the existence and characteristics of fast-track procedures, the number of laws amended per year and the activity of the opposition in practice.

Basic indicators of democratic functioning are the predetermined regularity of sittings, the predetermined distribution of time slots for political groups and the frequency of committee work.9 The Standing Orders of 1994 introduced cloture, guaranting equal speaking time for both government and opposition groups.10

Weekly sittings were used until 1998, when three-week plenary sittings were introduced for the third parliamentary term.11 However, the new left-wing coalition reintroduced weekly sessions in the next legislature.

The FL, and later the Parliament Act,12 stated that sittings should be convened in such a way as to ensure that, during ordinary sessions, sittings are held within a reasonable period of time.13 Therefore does not guarantee weekly sessions and, as we see in the next legislatures (both in the 2014–2018 and 2018–2022 legislatures), the Parliament had fortnightly sessions, reducing the possibility and space for democratic debates and strengthening the government vis-à-vis the Parliament.

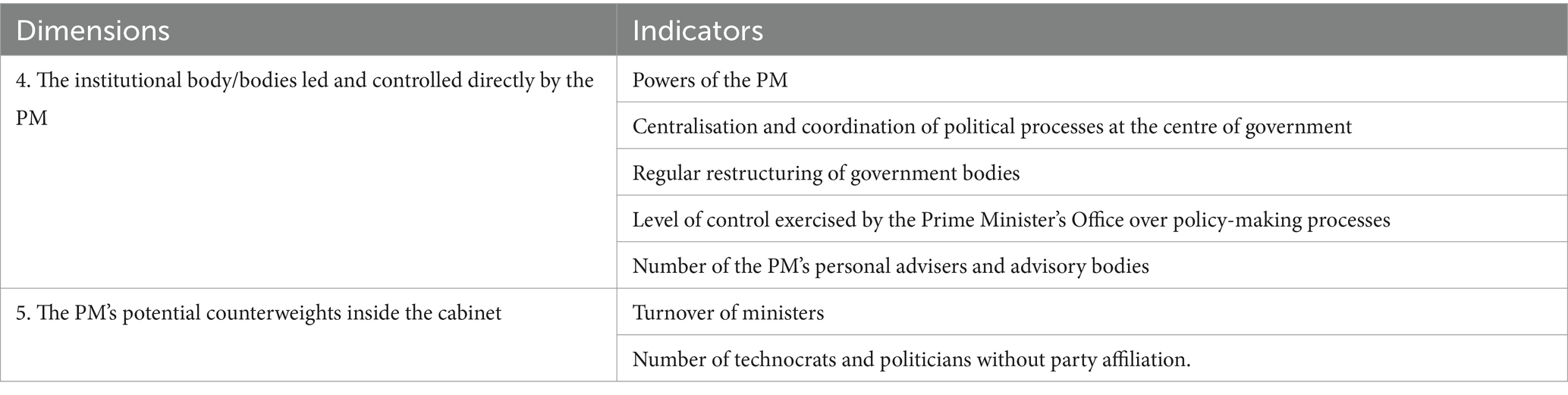

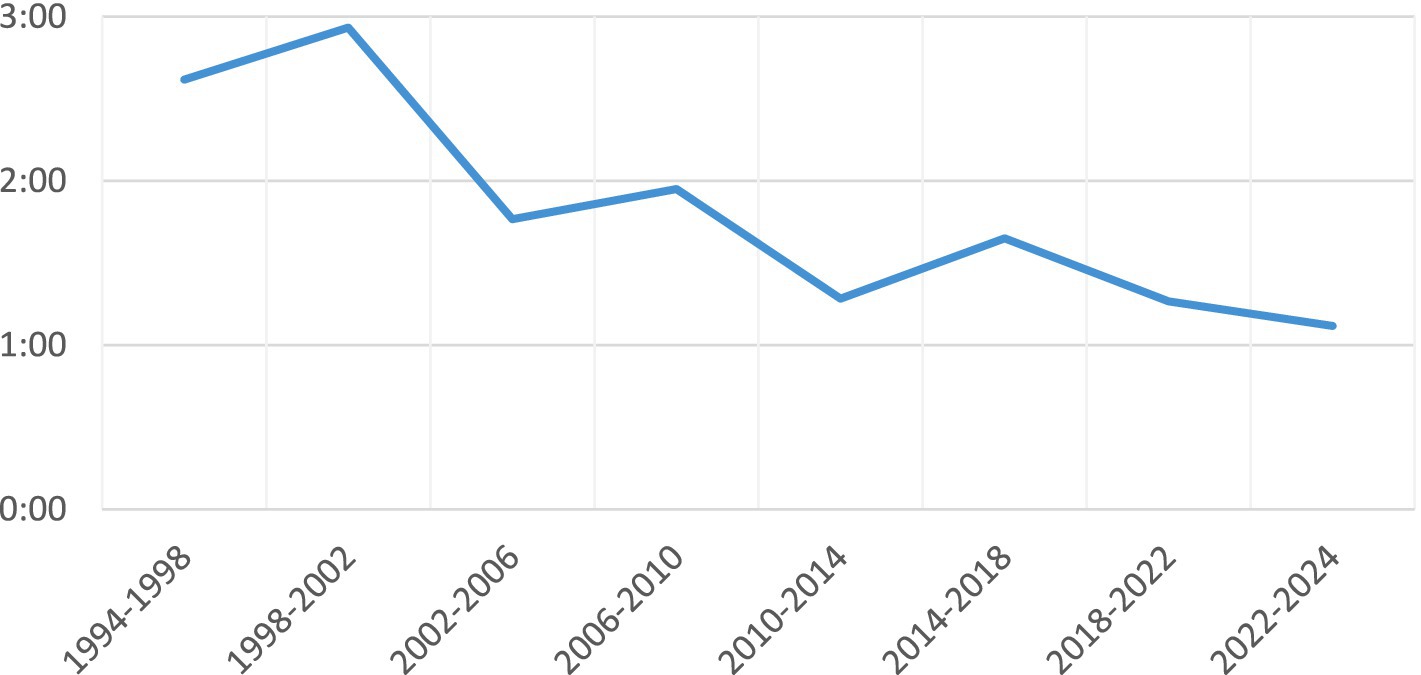

Parliamentary statistics show that both the number of sitting days and the average duration of debates per sitting day decreased between 1990 and 2023.14 During the emergency periods, all indicators—the number of parliamentary sessions (17%), the number of session days (16%) and the total duration of sessions (19%)—decreased only slightly compared to the periods before the crisis decade (Tanács-Mandák, 2024, p. 266–269). So, overall, we cannot say that the indicators related to the democratic functioning of the parliament have decreased significantly during the period of the special legal order (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average time for sittings (National Assembly Office and author’s calculations). For the year 2024 the data is available only till 15 October 2024.

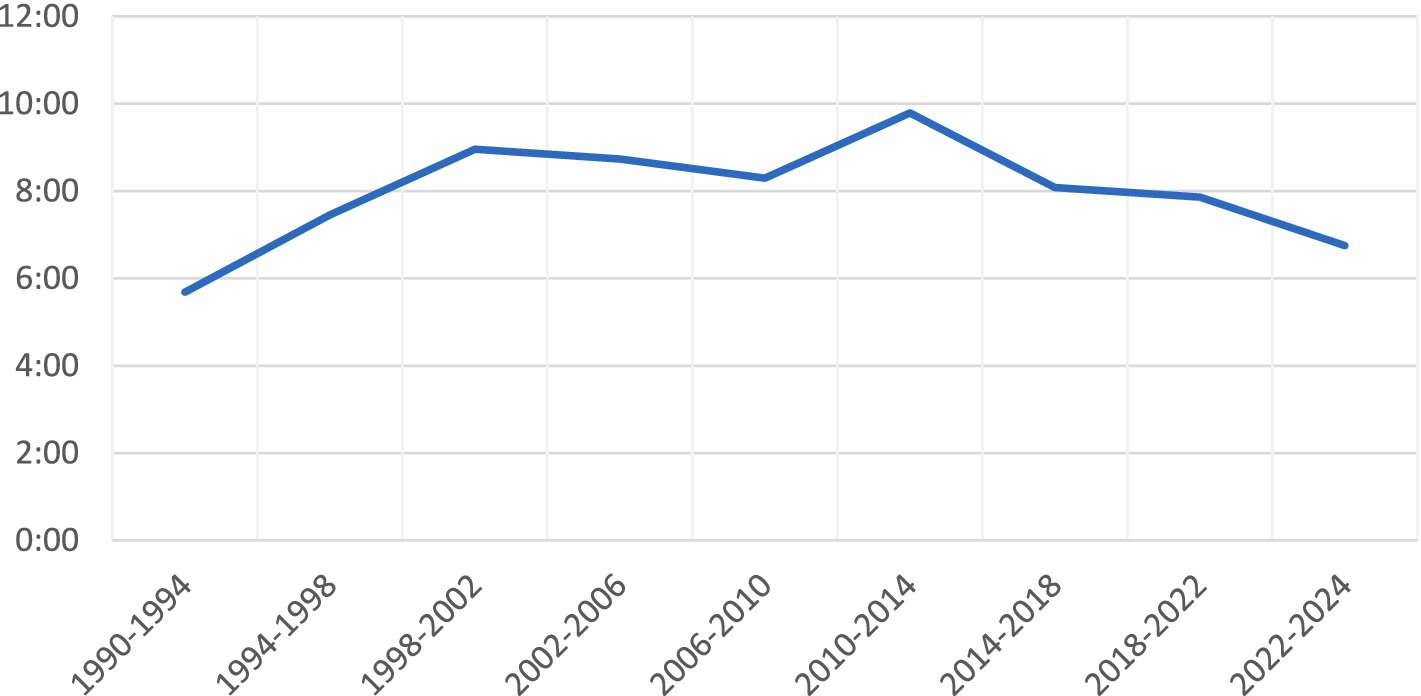

One of the key factors in measuring efficiency is the average time taken by parliamentary legislation. The Standing Orders reforms of the second legislature were intended to develop efficiency by curbing the obstructionist activities of the first legislature.

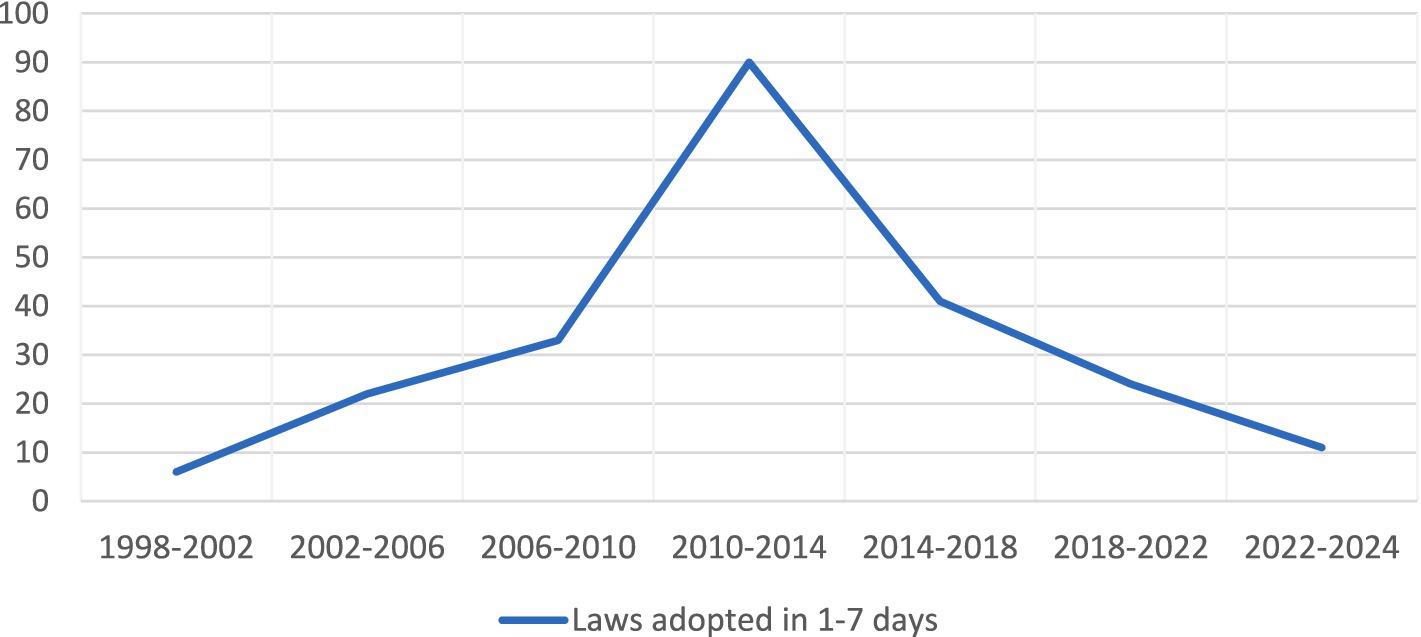

Later, the Standing Orders reforms of the 2010–2014 term had the explicit primary objective of ensuring reasonable timeframes and increasing efficiency in order to normalise the over-accelerated law-making. An analysis of the available parliamentary statistics15 suggests that there has been a general acceleration of lawmaking over time, but the real turning point came in the 2010–2014 term, when the average time fell by 20 days and the 37-day average achieved in that term has been maintained since (Tanács-Mandák, 2024).16 There is also a significant number of bills that were adopted in 7 days or less, and some that were adopted in 1 day (Figures 2, 3). In the 2022–2024 legislation term, there were 5 laws (Law No. LII of 2022, Law No. LXIX of 2023, Law No. XIV of 2023, Law No. XXV of 2023 and Law No. XXXII of 2024) that the President of the Republic either sent back to Parliament or sent to the Constitutional Court. Their adoption time was much longer than the average (161, 217, 84, 189, and 371 days), for this reason they were excluded from the calculation to prevent the distortion.

Figure 2. Average law adoption time (National Assembly Office and author’s calculations). For the year 2024 the data is available only till 15 October 2024.

Figure 3. Bills adopted in 1–7 days (National Assembly Office and author’s calculations). For the year 2024 the data is available only till 15 October 2024.

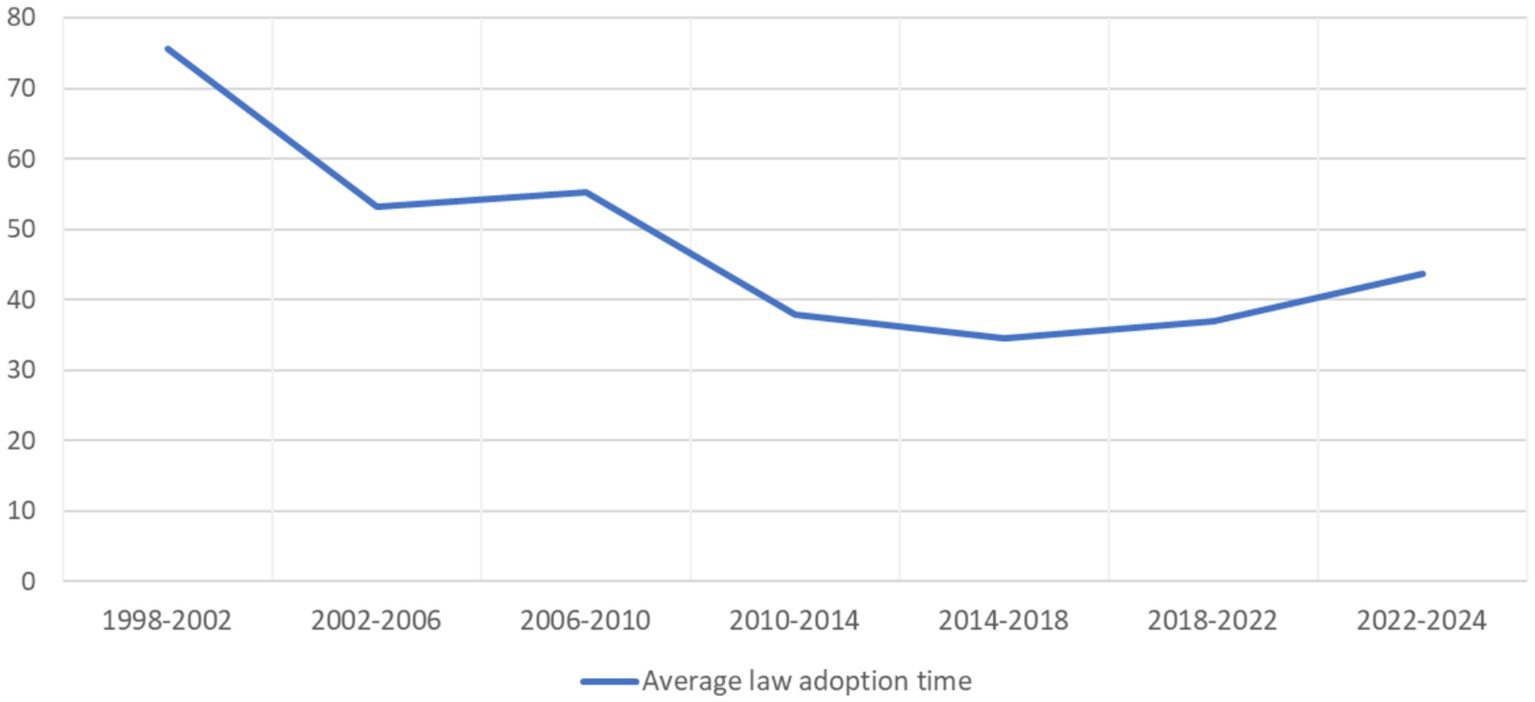

When analysing parliamentary efficiency, we must also include the number of committee meetings and their average duration, highlighting another parallel trend: the duration of committee meetings has been steadily decreasing, and since 2014 the average number of committee meetings has also been decreasing.17 This explicitly indicates that the more detailed policy debates are decreasing and/or no longer taking place in Parliament (Figure 4).18

Figure 4. Average duration of committee meetings (National Assembly Office and author’s calculations). For the year 2024 the data is available only till 15 October 2024.

A parliament can only be effective with the active participation of the opposition, while respecting the majority principle. The research examines the tools provided by parliamentary law for the opposition and the extent to which the opposition (is able to) use them, in particular in the case of officers and committee memberships and in the legislative process, especially by tabling bills.

The position of Deputy Speaker is particularly noteworthy from the opposition point of view, as Deputy Speakers play an important role in the work of Parliament through their role as presiding officers. Until 2010, there were always an equal number of government and opposition deputy speakers alongside the government speaker. From 2010, the balance tipped in favour of pro-government deputy speakers. In 2014, a new type of deputy speaker, the deputy speaker for legislation, was introduced, but in all cases he was pro-government, and in the last two terms 4 out of 6 deputy speakers were pro-government.

Since 1990, Parliament’s committee system has been based on political agreements made by the party groups at the beginning of each parliamentary term.19 The 1994 Standing Orders stated that each standing committee must include at least one member from each party group and that the number of members of standing committees must be proportional to the number of members of each party group.20 But the new rules of 2014, no longer require each party group to be represented in all committees, but still give party groups the right to participate in all committees. If they do not have a member, they can only participate in the debate of the committee, but they do not have the right to vote (Tanács-Mandák, 2024).21

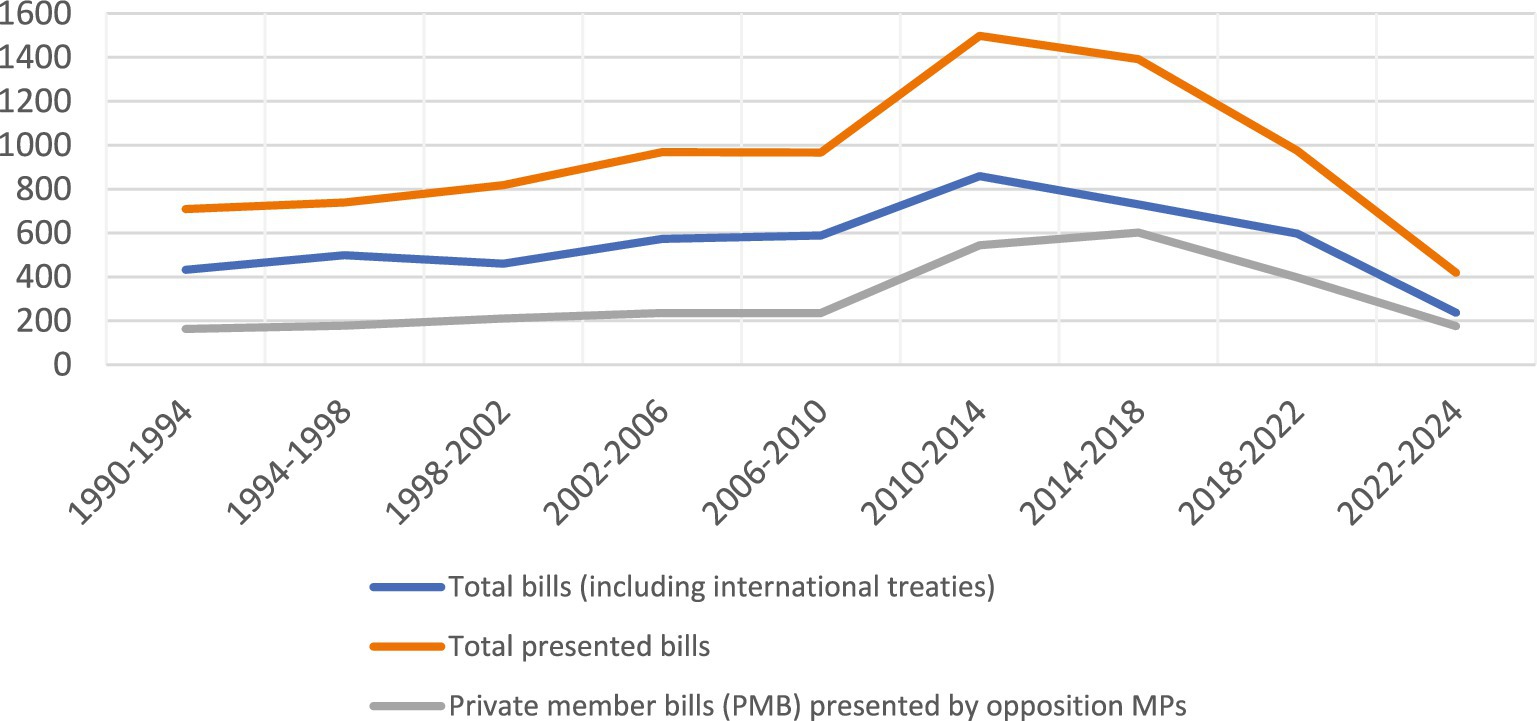

In addition to scrutinising the executive, the opposition’s other important function is providing alternatives. The first significant reform of the Rules of Procedure concerning the participation of the opposition in the legislative process, both in tabling its own motions and in participating in the legislative process in the case of laws requiring special majorities, appeared in the 2010–2014 legislature. On the one hand, the FL increased the number of qualified majority votes requested by the subjects and the number of decisions on persons that also require a two-thirds majority, thus strengthening the opposition’s ability to participate in decision-making.

On the other hand, the reform of the Rules of Procedure introduced the extraordinary urgency procedure and reduced the number of MPs required to initiate the extraordinary procedure from four-fifths to two-thirds; both changes explicitly reduced the opposition’s ability to participate actively in the legislative process.

Assessing the ambition and will of the opposition at all times, we can assume that while in the first term only 23% of bills were submitted by opposition MPs, in the 2018–2022 term there was a significant increase, with the opposition submitting 40.82% of all presented bills. However, while the number of bills submitted by opposition MPs was increasing, their success rate was incredibly low, ranging from 0.14 to 4.16 percent, and it did not reached 1 percent in any legislative term since 2010 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Bills submitted by the opposition (National Assembly Office and author’s calculations). For the year 2024 the data is available only till 15 October 2024.

According to the preamble of Act XI of 1987, laws in the Hungarian legal system should play a decisive role in regulating fundamental social relations.

The ordinary legislative procedure was first significantly reformed by the second Orbán government, which replaced the two-stage reading (plenary and committee stage) with a new system in which the general debate takes place in plenary and the committees, including the new Legislation Committee. A single set of amendments concluding the detailed debate and a committee report is prepared and sent to the Committee on Legislation (TAB), which incorporates the amendments it supports. In the final stage, the plenary discuss only the TAB proposal and decides by a single block vote (Tanács-Mandák, 2024).22

If we look at the proportion of laws passed by the proposers, we can see that the government has played an increasingly dominant role in the legislation over the past decades. When analysing the initiators of bills, we see that 39–64% of bills were initiated by the government in each legislative period, but the government’s share of approved bills is much higher 66–88%. The reason for the decrease in the share of bills submitted by the government compared to the total proposals between 2014 and 2018 is that this was the most active period for the opposition in terms of presenting alternative proposals (43.24%). However, there is a discrepancy when looking at the rate of bills passed, as only one of the 602 bills submitted was passed during this period.

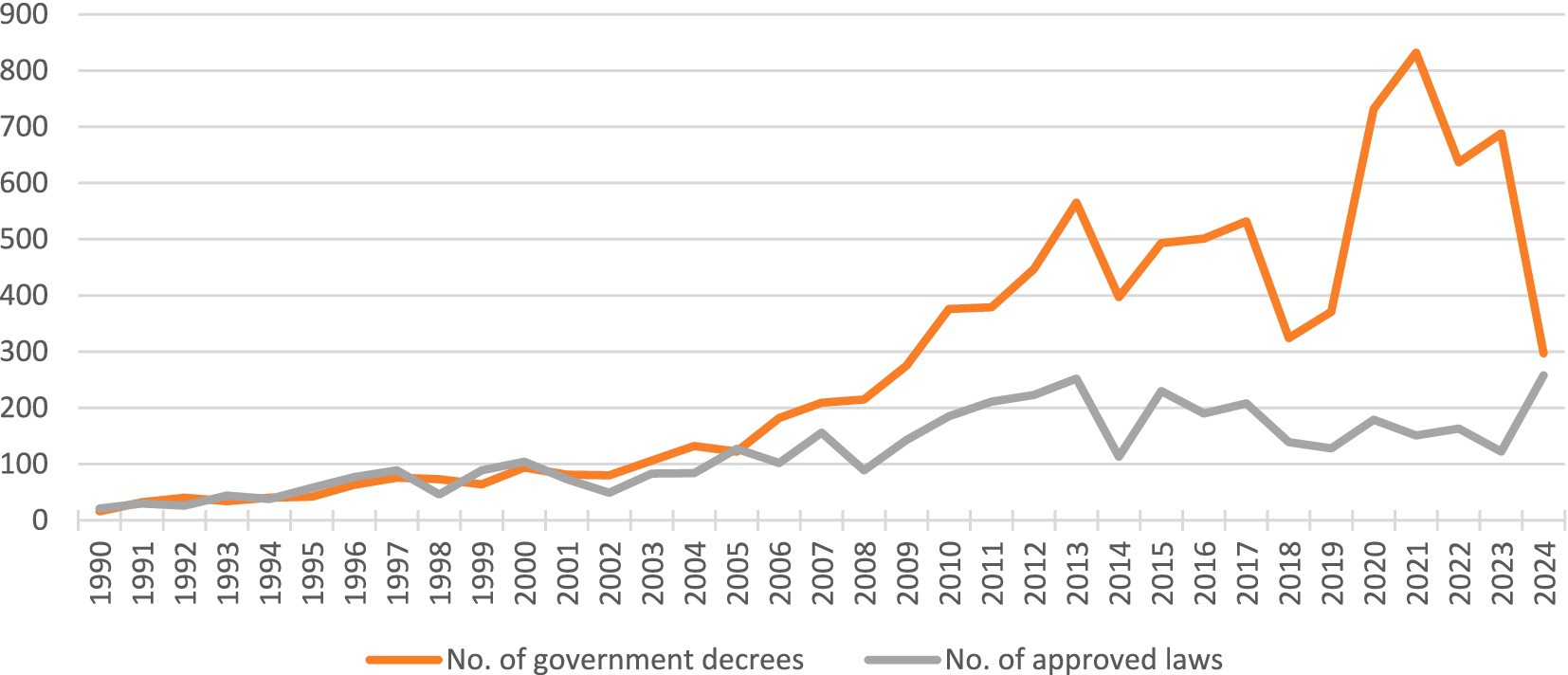

If we also look at the emergency period, we see a large number of government decrees. In terms of subsequent legislation, in parallel with the increase in the number of laws, we can see the reorganisation of legislation, resulting in more and more government decrees each year. The number of government decrees per year shows a steady upward trend, but an explicit significant growth can be observed from 2003 (106), while the peak was of course reached in the years of COVID-19 (832 government decrees in 2021), and in the last 2 years we might detect a decreasing tendency, which is significant especially in 2024. But it is important to note that before COVID-19 there were also several years with government decrees approaching or exceeding 500 per year (2013, 2015, 2016, 2017) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Comparing government decrees and approved laws (National Assembly Office and author’s calculations). For the year 2024 the data is available only till 15 October 2024.

Thus, the executive has assumed a dominant role in lawmaking and the Hungarian National Assembly has been marginalised.

In order to speed up the general legislative procedure, the Rules of Procedure provide a number of special instruments, such as derogations from the Rules of Procedure, the urgent procedure and the exceptional procedure.23

The Rules of Procedure of 1994 introduced the exceptional procedure24 and the derogation from the rules of the Rules of Procedure, which, although amended, is still in force today. Parliamentary statistics show that this instrument was used extensively between 2002 and 2014, with 140–190 motions adopted per legislature, but has almost disappeared since 2014.

In order to slow down the already accelerated legislative process, the parliamentary reforms of the 2010–2014 legislature introduced quantitative (maximum 6 motions per term, minimum 6 days between submission and final vote) and qualitative limits (the urgent procedure requires the support of 2/3 of the MPs present).

Parallel to the continuous strengthening of the government at the expense of the parliament, the role and importance of the parliamentary opposition has become more decisive. Although Morgenstern et al. (2008) have noted that a strong government does not necessarily imply a weak opposition, this point explains why this is not the case in Hungary.

Looking at the parliamentary control instruments of all terms, it can be assumed that opposition parties have regularly exercised some form of control. The FL and the Standing Orders have clarified the rules in many respects compared to the previous regulations. The main instruments of control are the interpellation, the question, the immediate question, while the secondary instruments are the committees of inquiry and the political debates (Magyar, 2018; Tanács-Mandák, 2024).

The first major reform to improve the opposition’s tools of control was the 1994 Standing Orders, which introduced the Prompt Question Hour, political debate and increased the time allowed for interpellations from 60 to 90 min per week, a timeframe that remains in force today. The opposition actively used almost all these powers, spending on average about 12–15% of the debate time on interpellations, questions and prompt questions (Mandák, 2014, p. 70–80).25

It is worth mentioning a peculiar Hungarian phenomenon, the practice of “self-interpellation” and “self-questioning” by the governing party, which was introduced in 1998 and continues to this day, and which has had a negative impact on the institutions that essentially provided the means for the parliamentary opposition to exercise its control functions.

Overall, the number of interpellations submitted to Parliament shows a steady increase since the first democratic legislature and a significant downward trend since the introduction of the two-week session in 2014.

The Committee of Inquiry has been one of the most common means of oversight of the executive, but here too there has been unusual government activity. However, changes to the Committee of Inquiry in 2014 have reduced and weakened the opposition’s options. The 2014 reform no longer requires committees to be initiated by 1/5 of MPs, and states that each standing committee will set up subcommittees to conduct inquiries. The previous parity of committees of inquiry has thus been abolished. The inquiry sub-committees will now operate with a government majority, as the government has a majority on the standing committees. Furthermore the Standing Orders have extensively regulated the subjects on which a committee of inquiry can be set up, stating that a committee of inquiry cannot be set up on matters that can be investigated by interpellation. The consequences of these changes are clearly visible in the parliamentary statistics: no committees of inquiry were set up in the last two terms.

The number of oral questions tabled in the 2018–2022 term was lower than in the previous terms. For most of this term, the use of immediate questions as the sole means of scrutiny has been adopted jointly by the majority and opposition groups as the practice for plenary sessions. Neither interpellations nor oral questions were requested by political groups in plenary. Overall, the use of scrutiny instruments has steadily decreased compared to previous legislatures for the reasons described above, but has shifted towards opposition MPs in terms of the proportion of submitters due to the increase in the number of political groups, in particular opposition groups, and the number of independent MPs.

Overall, the reforms of the Rules of Procedure in recent years have institutionalised some tendencies of presidentialisation, but at the same time, government practices that are not institutionalised at the Rules of Procedure, but applied in practice aiming to strengthen the government vis-à-vis the parliament, were equally important in the everyday work of the parliament.

The reforms of parliamentary rules and practice during the period under study have changed the relationship between government and parliament: decision-making processes have become faster, the PM and the government have become stronger in parliamentary work (expansion and simplification of the circle of special procedures, high number of “mixed laws”), while the opposition’s room for manoeuvre has been reduced. The latter was not only the result of the limitations of the equipment, but also the result of the government’s practice of “self-questioning” and “self-interpellation.” It can be said that some of the presidential tendencies and intentions have been institutionalised in the reforms of the Rules of Procedure, but in everyday parliamentary work the tricks used by the government still strengthen the executive.

The system of government established by Law XXXI of 1989 and Law XL of 1990 was consolidated during the first 20 years of democracy, despite the lack of political consensus, and its basic principles remained the same until the FL of 2011.

Since 1996, the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) has played a more important role in preparing decisions and in harmonising the government’s parliamentary work.26

From 1998, the PMO developed into a central institution headed by a minister. The charter of the PMO stated that it would lead and harmonise the strategic activities of the government.27 Furthermore, the reforms introduced the reference units, which were different policy units and departments of the PMO. Their role was to monitor and coordinate the work of the ministries and to develop independent technical proposals, limiting the freedom of the ministries. Thus began the transformation of the PMO into a chancellor office, the entire decision-making process was in the hands of the chancellor (Müller, 2011, p. 123). From then on, the PMO not only had administrative functions but also became a political body, dealing with the strategic leadership of the government.28

The Medgyessy government (2002–2004) continued these efforts, strengthening the structure of the PMO and giving it new powers. In the autumn of 2004, Ferenc Gyurcsány became the new PM, and by 2005 he had succeeded in developing an autocracy for himself. The party was transformed into a one-man party (Körösényi, 2006, p. 144–146), the number of PMO staff was increased and the legal equipment of the PM’s power29 was developed.30

The reform had a formal impact in three areas: the role of the PM, the decision-making process and the authority of the minister in charge of the office. It is important to mention the introduction of professional-political agreements, which limited the authority of individual ministers and strengthened the PM much more than the system of reference units, as this new system controlled and influenced the work of the portfolios. These meetings examined the political, professional, legal and financial sufficiency of the changes (Müller, 2011, p. 134).

In addition to the formal changes, there were also visible informal changes in the PMO’s working mode, such as the increasing number of cabinet meetings chaired by the PM and the decreasing of the length of government meetings (Rákosi and Sándor, 2006, p. 346). At this legislation term the PMO was transformed into a governmental centre directly headed by the PM.

One of the main aims of the first measures taken by the second Gyurcsány government was to present only legally and professionally agreed proposals to the meetings of state secretaries and the cabinet. To this end, a three-stage consultation system was introduced, starting with the political consultation in the PMO. At the first stage of this so-called pre-screening, it was checked whether the proposal was in line with the government programme; the second stage was to consult the relevant ministries and social partners; and the third stage was the political debate at the meeting of state secretaries.

The second Orbán government left the 1990 model of government essentially unchanged, although it introduced a number of changes to the structure, functioning and character of the government. The constitutional amendments adopted in 2011 changed the previous provisions on the tasks and the scope of the government’s authority,31 stating that the government is the general of the executive and the main body of the administration. It declared that the scope of the Government’s powers is everything that, according to the Constitution or any law, does not belong to any other body.32

The constitution differentiated the government from the other branches and strengthened its opposition to them. The possibility of review by the Constitutional Court was reduced in the case of economic and financial laws. It also limited the cases in which the Constitutional Court could be invoked.33

As a compulsory element of the structural changes, the PMO was abolished and the Prime Ministry was established. The tasks of the former Prime Minister’s Cabinet, such as the political coordination of the government, were taken over by the Prime Ministry, while professional and administrative tasks were assigned to the Ministry of Public Administration and Justice and its minister. The Prime Ministry was headed by the PM and operated by a Secretary of State.34 The tasks of the former government coordination centre were divided between two bodies, creating a kind of parallelism and a “competition” between the two institutions (Franczel, 2014).35

As a result of the 2010 reforms, the government agreements on the amendments are no longer decided by the professional political agreements of the second Gyurcsány government, but by the state secretary of the Ministry of Public Administration and Justice,36 so the government’s administrative centre decided whether the ministries’ initiatives could start the process.

The second Orbán government strengthened the PM’s role within the government at the constitutional level by several innovations such as declaring that the PM determines the general policy of the government,37 removing from the Constitution the reference on government meetings38 and ensuring the right to the PM to assign tasks to ministers.39

The ministers became increasingly dependent on the decisions of the PM because, according to the FL, the ministers run their ministries within the framework of the general government policy set by the PM.40 The PM selects the ministers and permanent secretaries and chooses his or her deputy(s), so his or her authority fully encompasses the work of all members of the government. While it used to be a constitutional duty to present the government’s programme to parliament and have it approved,41 the FL does not refer to this issue, thus increasing the PM’s freedom. The regulations of the second Orbán government also allowed the PM to issue a government decree or resolution on his own between government meetings and to present it later to the government as a whole.42

In 2014, political and administrative coordination were integrated again, and the Prime Ministery became a “superministry,” encompassing several key portfolios such as agricultural and rural development, EU funds, national financial services and postal services, territorial administration (Tóth, 2017, p. 57–61). In 2015, the independent Cabinet Office of the PM was created, and in summer 2016, two cabinets (strategic and economic) were organised43 to speed up and make government decision-making more efficient (Stumpf, 2021).

The 2018 elections44 also marked a turning point as the fourth Orbán government aimed more at a one-person, quasi-presidential government.

In the government decree on the duties and powers of the members of the government,45 the centre of government followed immediately after the PM. The Government Centre consisted of three institutions: the Prime Minister’s Government Office (Miniszterelnöki Kormányiroda) (PMGO), which reported to the PM; the Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office (Miniszterelnöki Kabinetiroda), which was responsible for policy coordination and communication; and the Prime Minister’s Office (Miniszterelnökség), which is responsible for administrative coordination and strategy formulation (as well as for certain specialised areas assigned to it).

The newly created PMGO co-ordinated the work of the ministries from an administrative point of view. It was chaired by the PM himself and headed by a Secretary of State. It also included the Minister without Portfolio for State Property—an indication that state property and other sectors in the asset management portfolio (e.g., gambling, postal services) play such a strategic role that they will be led directly by the PM. This also indicates a further strengthening of the role of the PM. In addition, the Prime Minister’s Office has been given a strategic, policy-making role by integrating the National Information Office into it (Tóth, 2018, p. 13). The main task of the Prime Minister’s Office has been to prepare the government strategy from a whole-of-government perspective.

The role of the cabinet system established in the summer of 2016 has been maintained and even strengthened, the four cabinets essentially cover the whole spectrum of government in order to facilitate the preparation and implementation of decisions at the government level, thus potentially relieving the PM and the bodies responsible for government coordination.

An overview of government coordination shows that the centralisation of responsibilities in several centres, the division of tasks and the creation of a political46 middle level within the government (between the PM and the ministers, the deputy prime ministers and the two coordinating ministers) indicate a centralised and hierarchical government.

Changes in the organisational structure and competences of the institutions responsible for government coordination are a typical feature of the Orbán cabinets, always after parliamentary elections, but often also during the legislative period. It can also be assumed, especially from the experience of the post-2010 period, that the institutions of government coordination play a key role in setting the policy direction of the government.

All three institutions introduced in 2018 were retained when the government was formed after the 2022 general elections, but both their relationship to each other and the scope of their portfolios changed significantly. Both the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister (COPM)47 and the PMGO were developed by transferring several other portfolios to them.48 The PMGO, which had previously operated as a separate body, was essentially integrated into the COPM. From then on, the PMGO is specifically responsible for administrative coordination.49

In a sense, the Prime Minister’s Policy Director is an existing actor, but new in his current position and powers. His main role is to advise the PM on a range of general and policy issues, and he may deputise the PM when answering immediate questions in Parliament.

In addition to the cabinets, the role of bodies set up to deal with specific issues has grown, especially since the fourth Orbán government. This is linked to the challenges facing the country, which are usually of global origin (migration crisis, coronavirus pandemic, economic consequences of the pandemic, Russian-Ukrainian war, war inflation, energy crisis, drought). The increasing number and role of the established bodies focusing on specialised areas (e.g., Defence Council, Operational Group, etc.) contributes to the complexity of the government structure and also reinforces the presidentialisation due to the overlapping of responsibilities as a result of the potentially formed competition among the actors (Tóth, 2022, p. 4–9).

Since 2010, it has been common practice to have large, integrated ministries, the so-called superministries. The year 2022 also brought a reform in this respect.50 The governments installed after 2010 have a large number of state secretaries, but in the current fifth Orbán government their number even reached a record high with a total of 57 state secretaries.

Assessing the institutional (internal) structure of the last four governments, it is clear that they were designed to promote centralisation and presidentialisation. The resources at the disposal of the government are undoubtedly in the hands of the PM through the strengthening of his own office. The PM has clear control over the decision-making process, as evidenced by the institutional strengthening of the so-called Government Centre. The creation of the independent post of Political Director also demonstrates the PM’s increased political control.

The second Orbán government significantly reduced the number of ministries with the development of the aforementioned “superministry” system. The structural reorganisation of the government—the general number of ministries was reduced from 13, in the previous period 11, to eight—not only simplified the structure of the government and enabled a more solid government policy, but also centralised the decision-making process. A significant concentration of tasks and scope of authority was achieved by merging different departments (Vadál, 2011, p. 43). Another change in the government structure was that the PM could appoint a commissioner to deal with the tasks that fell within his remit.51

In the original Poguntke-Webb model of presidentialisation, the small number of government members implies a weaker PM and stronger ministers. In the Hungarian case, however, superministries since the second Orbán government have actually strengthened the role of government centralisation. The obvious purpose of creating superministries was the need for more coherent government policy-making. The number of ministerial posts only increase from 2017 onwards.

Looking at the turnover rate and the possible parallel parliamentary mandate of government members as an indicator of presidentialisation, it can be seen that while there is little turnover at ministerial level, state secretaries are subject to frequent changes. Looking at the statistics of post-2010 governments, in general about two-thirds of government members also hold a parliamentary mandate. In the post-2010 Orbán governments, it has been an unwritten rule that members of the government, with the exception of the PM and his first deputy, cannot become members of the party leadership, thus avoiding the possibility of any politician gaining too much power and potentially jeopardising the PM’s position and power.

Since 2010, frequent ministerial changes have not been common, but the frequent changes of state secretaries and the continuous reorganisation of the institutional system of government coordination (and communication) have had a similar impact on the functioning of the government.

In the fourth Orbán government—similar to the first, coalition Orbán government—the proportion of ministers without a party (and/or parliamentary) background has increased. This in itself shows the role of the head of government as the sole determinant of the strategic direction of policy.

While between 2014 and 2018 in particular the majority of state secretaries held parallel parliamentary mandates, in the fifth Orbán government the proportion of outsiders has increased: only three of the 23 new cabinet members are MPs. The replacement of half of the cabinet members is in itself an expression of the personal will of the head of government.

It is clear from the above that the fifth Orbán government is a presidential government in a parliamentary system.

Since the democratic transition, Hungary’s chancellor-type parliamentary system has presupposed a strong head of government. In the political system established at the time of the democratic transition, a tendency towards centralisation of power began in the late 1990s, which became even more pronounced from 2006 onwards, and since 2010 there have also been tendencies towards explicit concentration of power in government reforms.

It is therefore clear that both the dominance of the government over Parliament and the prominence of the PM within the government are, by law, fundamental features of the Hungarian political institutional system. Since 2010, the position of PM has been held by a person whose authority within the ruling party is unquestioned, and the government structure has been designed to further strengthen the PM’s dominance.

Since the periods of extraordinary legal order were introduced in a significantly modified system of separation of powers, they further reduced the powers of the already weakened parliament, and it is reasonable to assume that the executive has not only governed against the parliament, but has even ignored it. For example, the introduction and expansion of extraordinary procedures strengthened the government, as the very short negotiation period and the very tight deadlines for amendments hindered and reduced the possibility of active parliamentary participation in the legislative process. In addition to the institutionalised strengthening of the government vis-à-vis Parliament and the emphasis on the PM, the non-institutionalised governmental practices used by all political forces are of equal importance, as they strengthened the executive power in everyday parliamentary work.

In the last term, the institutions known collectively as the Government Centre were also strengthened compared to previous terms, with the aim of centralising the functioning of the government and ensuring the most effective enforcement of the interests of the government as a whole, on the one hand, and ensuring political control—i.e. control by the PM—on the other. This tendency is reinforced by the creation of competing ministerial portfolios, the large and seriously restructured system of permanent secretaries, and the restructuring of the weight of the ministries.

Since 2015, the Orbán cabinets have been in a constant state of crisis—at least from the point of view of political communication—(the pandemic and war situation and the economic crisis partly resulting from both are real and serious challenges), which generally requires a strengthening and centralisation of the government. The structure and functioning of the Hungarian cabinet, which already has the foundations of centralisation, clearly shows a move in this direction.

In the case of Hungary, the trends show that presidentialisation was established and consolidated long before the decade of crises, and therefore it is not the rules and practices adopted during the crisis that contribute to its survival, although they are clearly part of this trend, but the tools and established practices introduced before 2015, and that is why it is expected to continue after the crisis.

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. This data can be found at: https://www.parlament.hu/en/web/house-of-the-national-assembly.

FT-M: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. TKP2021-NKTA-51 has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-NKTA funding scheme.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^The mutual independence of the two institutions was established by limiting the right of the government to dissolve parliament, the introduction of the constructive motion of non confidence and the missing motions of no confidence for ministers.

2. ^Law No. XX of 1949, Art. 33. and 37.

3. ^Between February 2015 and April 2018.

4. ^In political science terms, we do not consider Fidesz-KDNP governments as coalition governments (Ványi and Ilonszki, 2024).

5. ^A state of emergency was introduced at local level from 15 September 2015 and then at national level from 9 March 2016, with extensions until 7 September 2022.

6. ^Law No. XII of 2020.

7. ^FL, Art. 48. and 51.

8. ^FL, Art. 3.

9. ^A properly proportional electoral system is also necessary for the democratic functioning of parliament. The detailed analysis of the Hungarian electoral system is beyond the scope of this research, but it is important to note that the electoral reform adopted in 2011 shifted the electoral system towards majority rule (53.26% of mandates were allocated by majority rule compared to the previous 45.59%), reduced the number of MPs and modified the previous proportional channel, all of which have led to a more disproportionate representation in parliament.

10. ^The only exceptions were the budget, the final accounts and the motion of censure. See: Parliamentary Resolution No. 46 of 1994, Art. 53.

11. ^The first Orbán government justified the reform by the need to increase the efficiency of parliamentary work, but parliamentary statistics have not proved that the reform has made legislative work more efficient.

12. ^Law No. XXXVI of 2012.

13. ^Law No. XXXVI of 2012, Art. 34.

14. ^Although the last two legislatures had fortnightly sessions, the number of sessions and session days were almost the same or slightly less than in the 1998–2002 legislatures, when there were three weekly sessions.

15. ^Data only available from 1998 onwards.

16. ^The time taken to legislate is calculated by taking the time between the date of submission of the bills and the date of the final vote. The calculation does not take into account rejected bills that did not pass the final vote.

17. ^The average number of meetings per standing committee was between 120 and 140 in all legislative terms until 2014, the only exception being the first Orbán government, when the introduced three-weekly meeting system significantly reduced this indicator to 86. Since the 2014 parliamentary elections, a clear downward trend can be observed: in the 2014–2018 term, an average of 83 and in the 2018–2022 term, an average of 66 meetings of standing committees were held in the four-year legislative period.

18. ^The fact that detailed public policy debates have moved to a new arena could also be confirmed by analysing the number and length of cabinet meetings and the change in the number of proposals discussed at the meeting. Data on this, however, are only available for the period 1994–2013. The author has received a negative reply to a request for public data for the subsequent period [Reply to data demand for public interest Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office MK_JF_közadat/66/2 (2024)].

19. ^So far, the only time Parliament has deviated from this practice was in 2010, when opposition groups failed to agree on the distribution of committee seats.

20. ^Parity of representation is compulsory for the Immunity Committee. It is also stated that the chairperson of the Committee on National Security must always be an opposition MP, and since 1990 the Budget Committee has also been chaired by an opposition MP.

21. ^Law No. of XXXVI of 2012, Art. 40 (1) and (2).

22. ^A party group and the submitter of the motion may request a detailed vote.

23. ^In the 2010–2014 legislature, there was a fourth instrument, the exceptional urgency procedure [Articles 128/A-128/D of Parliamentary Resolution 98/2011 (31.12)]: it allowed the final vote to take place the day after the decree was issued. This clearly strengthened the hand of the government in the legislature. The emergency procedure was abolished in 2014.

24. ^The exceptional procedure is allowed for debates on bills that do not require a two-thirds majority, mainly of a technical nature, and is conducted in committee, with only a summary of the debate and a final vote in plenary.

25. ^There have only been two terms when this rate fell below 12%, between 1998 and 2002 (due to the three-week sessions) and 2010–2014.

26. ^The PMO prepared an expert report on the proposals and bills under discussion, which was not only a constitutional and legal assessment, but also an economic and political one. Law No. LXXIX of 1997, Art. 39.

27. ^Government Decree No. 137 of 1998.

28. ^It is important to note that this term has also seen an expansion of informal institutions and decision-making mechanisms. The most significant change compared to previous terms was the establishment of the so-called “carriage of six,” which strengthened the PM’s power both vis-à-vis parliament and within the government. This group coordinated the work of the government, Fidesz and the parliamentary group as a special steering body. Its members were the most prominent members of the party (Wiener, 2010).

29. ^The basis for the changes was Law No. LVII of 2006. In addition to the content of the reform, its preparation, drafting and approval were also important, as this so-called government law was developed without the apparatus of external experts (Müller, 2011, p. 27).

30. ^In order to increase the number of Gyurcsány supporters, he significantly increased the staff of the PMO, making it the most important institution of political patronage. He set up parallel apparatuses, formed informal advisory syndicates, increased the number of government commissioners and created the informal post of Prime Minister’s Commissioner.

31. ^Law No. XX of 1949 Art. 35, [a]-[m].

32. ^Law No. XX of 1949 Art. 15.

33. ^While the Law No. XX of 1949 said that anyone can start a procedure at the Constitutional Court (Constitution of 1949, Art. 32/A para 3), according to the Constitution now, this can only be done by the government, one fourth of the representatives and the Commissioner for Fundamental Rights [Fundamental Law of Hungary, Art. 24 para 2, (e)].

34. ^Law No. XLIII of 2010. Art. 36.

35. ^In my opinion, minor disagreements between the PM and the Minister of Public Administration and Justice made it a little difficult to implement the PM’s ideas, but in the long run the Minister could not weaken the PM because he was also dependent on him.

36. ^Government Decision No. 1144 of 2010, Art. 24.

37. ^FL, Art. 18 (1). For more details see Stumpf and Kis, 2023, p. 107–110.

38. ^The collegial nature of the government takes the form of a cabinet meeting. The position of PM, strengthened by the second Orbán government, did not in itself reduce or eliminate the collegial nature of government. As a result of the reforms affecting the government, the collegial nature of the government has been reduced, both in terms of its public law basis and its practical functioning. While the Constitution in force previously had provided for the decision-making forum of the government [Act XX of 1949, § 37 (1)], the FL no longer included the concept of a government meeting, nor did it make any indirect reference to the form of government as a body. In addition, the Act on the Functioning of the Government [Government Decision 1144/2010 (7.7.2010)] stated that the functions and powers of the Government as a body, and that it meets regularly [Government Decision 1144/2010 (7.7.2010), points 1–2]. However, it is important to emphasise that the term “body” has ‘slipped’ from the constitutional level to the level of a government decision.

39. ^FL, Art. 18 (2).

40. ^FL, Art. 18. (2).

41. ^Law No. XX of 1949, Art. 33 para 3.

42. ^Government Decision No. 1144 of 2010, Art. 77.

43. ^Government Decree No. 215 of 2016, Government Decree No. 1399 of 2016.

44. ^It is important to underline that there was a high turnout, which gave more support to the winning political force.

45. ^Government Decree No. 94 of 2018.

46. ^This level does not appear as an administrative level within the government, but its political relevance is obvious. The structure of the statute—the PM is followed by the three entities known as the Government Centre (PMGO, COPM and the Prime Minister’s Office), then the Deputy Prime Minister General, then the ministries of the Deputy Prime Minister, who also heads the two ministries, and only then the other ministries and ministers without portfolio—indicates the prominent, central position of these actors or institutions.

47. ^The official English translation of the institution changed from the Prime Minister’s Cabinet Office to the Cabinet Office of the Prime Minister, but the institution remained the same.

48. ^The most important change was to take control of the secret services.

49. ^Law No. IV of 2022, Art. 188.

50. ^On the one hand, the new cabinet is dominated by ministries and economic ministers; on the other hand, the boundaries of responsibilities between ministries, ministers and state secretaries are not clear and there may be some overlap between portfolios.

51. ^Law No. XLIII. of 2010, Art. 32.

Bolleyer, N., and Salát, O. (2021). Parliaments in times of crisis: COVID-19, populism and executive dominance. West Eur. Polit. 44, 1103–1128. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2021.1930733

Bromo, F., Gambacciani, P., and Improta, M. (2024). Governments and parliaments in a state of emergency: what can we learn from the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Leg. Stu. 22, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2024.2313310

Edgar, A. (2024). Regulation-making in the United Kingdom and Australia: Democratic legitimacy, safeguards and executive Aggrandisement. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

Enyedi, Z. S. (2001). Prezidencializálódás Magyarországon és Nagy-Britanniában. Századvég 2002, 127–135.

Erdős, C., and Tanács-Mandák, F. (2023). The Hungarian constitutional Court’s practice on restrictions of fundamental rights during the special legal order (2020–2023). Eur. Politics Soc. 25, 556–573. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2023.2244391

Farrell, D. M., Field, L., and Shane, M. (2024). Parliamentarians and the Covid-19 pandemic: insights from an executive-dominated, constituency-oriented legislature. J. Leg. Stu. 22, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/13572334.2024.2400844

Franczel, R. (2014). A miniszterelnökség szervezete 2010-2014 között. Kodifikáció és közigazgatás 2014, 5–38.

Gárdos-Orosz, F. (2024). Constitutional justice under populism: the transformation of constitutional jurisprudence in Hungary since 2010. Zuidpoolsingel Ze: Kluwer Law International.

Gellén, M. (2024). Crisis management experience in Hungary. Glob. Public Policy Gov. 3, 334–353. doi: 10.1007/s43508-023-00077-y

Ginsburg, T., and Versteeg, M. (2021). The bound executive: emergency powers during the pandemic. Int. J. Const. Law 19, 1498–1535. doi: 10.1093/icon/moab059

Guasti, P., and Bustikova, L. (2022). Pandemic power grab. East Eur. Politics 38, 529–550. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2022.2122049

Horváth, A. (2021). “A 2020-as Covid-veszélyhelyzet alkotmányjogi szemmel” in A különleges jogrend és nemzeti szabályozási modelljei. eds. Z. Nagy and A. Horváth (Budapest: Mádl Ferenc Összehasonlító Jogi Intézet), 149–173.

Khaitan, T. (2019). Killing a constitution with a thousand cuts: executive aggrandizement and party-state fusion in India. Int. J. Constit. Law 17, 342–356. doi: 10.1093/icon/moz018

Khaitan, T. (2020). Killing a constitution with a thousand cuts: Executive aggrandizement and party-state fusion in India. Law & Ethics of Human Rights, 14, 49–95.

Körösényi, A. (2001). Parlamentáris vagy elnöki kormányzás? Az Orbán-kormány összehasonlító perspektíváiból. Századvég 2001, 3–38.

Körösényi, A. (2003). Politikai képviselet a vezérdemokráciában. Politikatudományi Szemle 2003, 5–22.

Körösényi, A. (2006). “Gyurcsány-vezér” in Magyarország politikai évkönyve 2006. eds. P. Sándor, Á. Tolnai, and L. Vass (Budapest: Demokrácia Kutatások Magyar Központja Alapítvány), 141–149.

Kosztrihán, D. (2024). Titkárságból kormányzati központ—A miniszterelnöki háttérapparátus intézményi evolúciója. Jog Állam Politika 16, 63–78. doi: 10.58528/JAP.2024.16-2.63

Küpper, H., and Térey, V. (2009). “A Kormány” in Az Alkotmány kommentárja. ed. A. Jakab (Budapest: Századvég).

Lijphart, A. (1999). Patterns of democracy: Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. New Haven, CT: Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Magyar, Z. (2018). A parlamenti ellenőrzés eszközei az Országgyűlés gyakorlatában. Parlamenti Szemle 2018, 125–150.

Mandák, F. (2014). A politika prezidencializációja—Magyarország, Olaszország, PhD disszertáció. Budapest: Nemzeti Közszolgálati Egyetem.

Mandák, F. (2015). “Signs of Presidentialization in Hungarian government reforms—changes after the fundamental law” in Challenges and pitfalls in the recent Hungarioan constitutional development. eds. Z. Szente, F. Mandák, and Z. Fejes (Paris: L’Harmattan), 148–168.

Mészáros, G. (2024). How misuse of emergency powers dismantled the rule of law in Hungary. Israel Law Rev. 57, 288–307. doi: 10.1017/S0021223724000025

Morgenstern, S., Javier Negri, J., and Pérez-Liñán, A. (2008). Parliamentary Opposition in Non-Parliamentary Regimes: Latin America. J. Legis. Stud., 14, 160–189. doi: 10.1080/13572330801921166

Musella, F. (2019). Constitutional change in Presidentialised regimes. Different paths of reform in Hungary and Italy. DPCE Online 2, 1451–1464. doi: 10.57660/dpceonline.2019.740

Paczolay, P. (2007). “Magyar alkotmányjog 1989-2005” in A magyar jogrendszer átalakulása 1985/1990–2005. eds. A. Jakab and P. Takács (Budapest: Gondolat-ELTE ÁJK).

Paczolay, P. (2015). “The first experiences of the new jurisdiction of the Hungarian constitutional court—a view from inside” in Challenges and pitfalls in the recent Hungarioan constitutional development. eds. Z. Szente, F. Mandák, and Z. Fejes (Paris: L’Harmattan), 169–184.

Poguntke, T. (2000). The presidentialization of parliamentary democracies: A contradiction in terms. In presentation at the ECPR workshop.

Poguntke, T., and Webb, P. (2005). eds. The presidentialization of politics: A comparative study of modern democracies. Oxford: OUP.

Rákosi, F., and Sándor, P. (2006). Egy politikai kormány szerkezeti terve in A 2006-os választások: elemzések és adatok. ed. G. Karácsony (Budapest: DKMKA), 335–379.

Steuer, M. (2024). Judicial self-perceptions and the separation of powers in varied political regime contexts: the constitutional courts in Hungary and Slovakia. Eur. Politics Soc. 25, 537–555. doi: 10.1080/23745118.2023.2244390

Stumpf, I. (2021). Kormányzás, hatalommegosztás, prezidencializálódás. Máltai Tanulmányok 3, 225–244.

Stumpf, I., and Kis, N. (2023). Változások és közjogi kontinuitás a magyar kormányzásban. Pro Publico Bono 11, 103–125. doi: 10.32575/ppb.2023.4.6

Szente, Z. (2015). “The decline of constitutional review in Hungary—towards a partisan constitutional court” in Challenges and pitfalls in the recent Hungarioan constitutional development. eds. Z. Szente, F. Mandák, and Z. Fejes (Paris: L’Harmattan), 185–210.

Szente, Z., and Gárdos-Orosz, F. (2022). “Using emergency powers in Hungary: against the pandemic and/or democracy?” in Pandemocracy in Europe: Power, parliaments and people in times of Covid-19. eds. M. C. Kettemann and K. Lachmayer (Oxford: Hart Publishing), 155–178.

Tanács-Mandák, F. (2024). “The Hungarian parliament in the shadow of crisis (2015-2023),” in Proceedings of the Central and Eastern European eDem and eGov Days 2024, 266–273.

Tölgyessy, P. (2006). “Túlterhelt demokrácia” in Túlterhelt demokrácia. ed. C. Gombár (Budapest: Századvég).

Tóth, L. (2017). A végrehajtó hatalom prezidencializálódásának egyes aspektusai a II. és a III. Orbány-kormányok esetében. Parlamenti Szemle 2017, 47–68.

Tóth, L. (2018). A IV. Orbán-kormány struktúrája a végrehajtó hatalom prezidencializációja és a kormányzati stabilitás tükrében. Új Magyar Közigazgatás 11, 1–10.

Tóth, L. (2022). Az V. Orbán-kormány struktúrája és összetétele a végrehajtó hatalom prezidencializációja szempontjából. Új Magyar Közigazgatás 15, 2–11.

Ványi, É., and Ilonszki, G. (2024). “Party alliances and personal coalitions” in Coalition politics in Central Eastern Europe. eds. T. Bergman, G. Ilonszki, and J. Hellström (London: Routledge), 118–141.

Keywords: presidentialisation, Hungary, state of danger, special legal order, government, parliament

Citation: Tanács-Mandák F (2025) The Hungarian governments in the decade of crises (2015–2024). Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1541887. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1541887

Received: 08 December 2024; Accepted: 20 January 2025;

Published: 17 February 2025.

Edited by:

Ádám Varga, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, HungaryReviewed by:

Paulina Bieś-srokosz, Jan Długosz University, PolandCopyright © 2025 Tanács-Mandák. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fanni Tanács-Mandák, bWFuZGFrLmZhbm5pQHVuaS1ua2UuaHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.