- 1City University of New York, New York, NY, United States

- 2Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

- 3Department of Political Science, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

The proposed judicial reform of 2023 is often framed as a countermovement to the judicial revolution of the 1990s. In this narrative, Chief Justice Aharon Barak, along with other Supreme Court justices, led a top-down transformation that established the court as a dominant institution, driven by the ambition—and perhaps the ego—of those on the judicial bench. If this interpretation were accurate, the 2023 reform could be viewed as a legitimate and necessary step to restore popular sovereignty and counter what might be seen as an overreach of judicial power. We reject this account and argue that the key to understanding these developments lies in the enduring tension between the Jewish and democratic components of Israel’s identity, a conflict evident as early as the Proclamation of Independence. Instead, we argue and empirically demonstrate how the changes of the 1990s were less about judicial ambition and more about the local response to a global shift triggered by the end of the Cold War. During this period, Israelis—across political elites and the broader public—sought alignment with the Cold War victors: Western liberal democracies. This alignment motivated a broad push to enhance the democratic dimensions of the nation’s identity, often at the expense of its Jewish elements. Drawing on extensive empirical evidence, including legislative committee debates, political speeches, and patterns of ratifications of international treaties by the Knesset, we demonstrate that this shift was not the product of judicial machinations but rather a reflection of the era’s historical and global dynamics. Framing the changes of the 1990s in this light fundamentally alters our understanding of the 2023 judicial reform. It challenges the popular—and often populist—narrative justifying the reform and reveals it as a response to a much deeper historical process rather than a simple correction of judicial overreach.

Introduction

This article offers a reexamination of the framework for understanding Israeli democracy by advancing three interlinked arguments. First, we propose replacing the traditional left–right political axis with one based on the tension between the democratic and the Jewish elements in the identity of the State of Israel. This alternative framework captures the pendulum swing between these elements, providing a more nuanced explanatory tool for understanding Israeli politics, including the constitutional crisis of 2023. Second, we highlight the importance of constitutional ambiguity, arguing that the lack of a formal constitution has been an asset for Israel’s political leaders. This flexibility allowed them to navigate a complex political landscape and reconcile competing priorities within the state’s dual identity as a Jewish democracy. Third, we analyze the profound shifts of the 1990s, contending that these changes were driven by global geopolitical transformations, notably the end of the Cold War. These shifts reshaped domestic politics, sparking a surge in democratization as Israel sought to align itself with the Western liberal democracies that emerged as victors in the new global order in the aftermath of the end of the Cold War.

The Israeli zeitgeist during the 1990’s was set on becoming a part of the Western post-cold-war re-invigorated democratic world. The Court was one of the platforms to run these processes and apply them to government institutions, political norms and the very act of governance. In that, this paper tackles claims made by the literature concerning the key role played by CJ Aharon Barak who coined the term constitutional revolution relating to the way the Israeli Supreme Court, mostly as the High Court of Justice, did in its rulings at the early 1990s (Rubinstein, 2006). Barak might have been both adored and scorned by many for his activities as a Judge and Supreme Court president. However, Barak was a mere reflection of the state of affairs of his time, representing a liberal-democratic mindset that characterized other government institutions in Israel. We do not underestimate Barak’s contribution to Israeli democracy and his activities to strengthen it. Yet, we seek to set his activities within a macro-historical-cultural setting, which sees Israel in a global context of the 1990s’ battle for democratization across the post-cold-war globalizing and democratizing world. We demonstrate Israeli political leaders’ institutions concerning democracy using quantitative and qualitative text analyses examining Knesset and government documents from the 1990s to show that Israeli elected leaders at the time were keen on democratization, leaning to a state that was less Jewish and more democratic.

The traditional left–right axis in Israeli politics often frames political debates in overly dichotomous terms. While this perspective may align with party-line voting, coalition dynamics, and ideological camps in the Knesset, it fails to capture a deeper, more enduring tension: the interplay between Israel’s democratic and Jewish character (Doron, 2005). The Declaration of Independence embodies this duality, asserting the establishment of a Jewish state while simultaneously committing to democratic principles such as equality and freedom for all. Unlike the left–right axis, which emphasizes binary distinctions, the democratic-Jewish tension is continuous, with both elements coexisting and shaping contentious politics. Rather than one elements existing at the expense of the other, it is about the point of balance between the two, and its shifting location over time.

Historical events illustrate this dynamic. During the Oslo Accords, Yitzhak Rabin’s government pursued peace initiatives framed as essential to safeguarding Israel’s democratic nature. Opponents, however, focused on Jewish territorial and religious claims. Similarly, the 2005 Gaza disengagement, led by Ariel Sharon, demonstrated the primacy of democratic legitimacy in decision-making, while its fiercest resistance came from groups emphasizing Jewish religious principles. The 1977 political upheaval compellingly rendered a deep democratic shift in the Israeli political system compounded along a transformation in its division of religious conservatism (Cohen, 2018). These examples, which we go into great detail in this article, underscore the inadequacy of the left–right framework. Instead, they empirically demonstrate the explanatory value of the democratic-Jewish axis which we offer should replace the left–right dichotomy.

The end of the Cold War marked a pivotal moment in global politics, with Western liberal democracies emerging as clear victors. This geopolitical transformation profoundly influenced Israel, tilting the democratic-Jewish pendulum toward democracy. Like nations in Eastern Europe striving to align with Western standards, Israel sought to position itself among the global “winners” by reinforcing and further enhancing the democratic elements in its constitutive values (Levitsky and Way, 2005). The judicial reforms of the 1990s institutionalized these popular aspirations for democracy, embedding them into Israel’s legal and political framework. Far from an act of judicial overreach, the Supreme Court’s actions reflected public will and bolstered Israel’s status within the democratic community of nations.

From the outset and during the 1990s reforms, the absence of a formal constitution in Israel enabled leaders to pragmatically navigate the tension between Jewish and democratic priorities. While often criticized, this constitutional vagueness—the “gray areas”—has proven to be an asset, facilitating compromises essential for sustaining the Zionist project and managing crises (Mautner, 2008, 2018).

The constitutional revolution of the 1990s, shaped by global shifts and domestic aspirations, offers critical insights into the proposed judicial reforms of 2023–25 (Gold and Tal, 2023). The enduring struggle to balance Israel’s Jewish and democratic identities remains central to its political evolution (Sheleg, 2020; Woods, 2009). By situating contemporary challenges within the historical context of the Cold War’s end and Israel’s democratic trajectory, we aim to reconfigure the discourse surrounding Israeli democracy’s present and future (Newman, 2023). The political importance of the 1990s in Israeli society is well-documented, yet the specific influence of Barak remains insufficiently analyzed.

Literature review

Following a 30-year political hegemony, the Labor Party’s electoral loss in 1977 ushered in Israel’s current multiparty configuration, characterized by shifting political alliances. Although right–left dualities often frame Israeli politics, this binary has become increasingly inadequate for understanding its complexities (Peters and Pinfold, 2018). Contemporary political factions in the Knesset are divided into ideological “camps,” with the left—primarily represented by Labor—associated with social democracy, secularism, and anti-occupation positions. Conversely, the right, led by Netanyahu’s Likud and aligned with orthodox parties, emphasizes nationalism, security, settlement expansion, and opposition to a two-state solution (Lederman, 2021).

Although the Israeli–Palestinian conflict drives political dissention, debate over the Occupied territories alone is not the main cause of Israel’s political rift (Arian and Shamir, 2008; Orkibi, 2022; Shamir and Arian, 1999; Horowitz and Lissak, 1989; Shafir and Peled, 2002). Numerous other ideological debates separate these factions, complicating the use of the left–right axis (Rahat and Hazan, 2005). The cultural rift of Zionism—between religious and secular—may be at the heart of Israel’s current political crisis (Horowitz and Lissak, 1989; Shafir and Peled, 2002). Tensions characteristic of national politics do not follow this typical dichotomy—voters no longer cast their ballots along such party lines. We argue that although using camps of right versus left to understand Israeli politics is the common practice, such an axis is inadequate to truly analyze Israeli political reality, suggesting a need for a different conceptualization.

We propose using the dual elements of Judaism and democracy—both constitutive elements for the State of Israel—to replace the left–right dichotomy (Sommer and Braverman, 2024a; Talshir, 2022). This framework offers a more nuanced understanding of longstanding trends and recent political turmoil. Since its inception, Israel has been defined as both Jewish and democratic, but the proper balance between these elements remains contested. On the one hand, the democratic camp prioritizes institutional checks and balances, civil liberties, and minority rights. On the other, proponents of Jewish values emphasize preserving Israel’s Jewish majority, traditions, and identity, in some cases even at the expense of democratic norms (Liebman and Shokeid, 2018; Sommer, 2009, 2010a, 2010b).

The degree of incompatibility between these principles has fueled political divisions. Western democratic individualism often clashes with the collectivist ethos underlying Jewish communal traditions (Sheleg, 2020; Raval, 2012). Nevertheless, Israel’s relative flexibility in balancing these values has historically ensured its institutional endurance. Compromises across the political spectrum have allowed the state to navigate these tensions, though such “gray zones” are increasingly under stress from efforts to prioritize Jewish identity over democratic structures.

Israel’s capacity to maintain relative flexibility in the balance between its Jewish and its democratic elements accounts for the endurance and success of Zionism. Politicians of all ideological strands have been willing to balance and compromise on the meanings and implementations of democracy and Judaism. It is such inherent vagueness in the identity of the state as well as in its very operation, that allow sufficient wiggle room to tilt the balance back and forth between the two elements. It also allows the institutions of government to persist over decades, despite the lack of constitutional entrenchment. Attempts to bolster Israel’s identity as a Jewish state at the expense of its democratic character complicate the relationship between the state, its religion, and its citizens (Weinshall et al., 2018; Sommer and Braverman, 2024b). Given the intricacy of Israel’s balance between democracy and Judaism, constitutional vagueness is necessary to allow wiggle room for government negotiation and individual autonomy, while allowing a shifting balance between the Jewish and the democratic elements of the nation.

Opposing political currents in Israel strive to tilt the balance between Israel’s Jewish and democratic attributes. Those aspiring for a turn in a Jewish direction at the expense of democratic features see the judicial revolution of the 1990s as a watershed event. Under the leadership of Chief Justice, Aharon Barak, democratic elements swelled at the expense of Jewish elements. Appointed to the Supreme Court in 1978, Barak served as associate justice until 1995 and was then elevated to serve as Chief Justice until his retirement in 2006 (“Aharon Barak”; Aharon Barak, n.d.). During his tenure, Barak is credited with (or blamed for) expanding the sphere of influence of the judiciary, some argue while usurping the power of the legislature. Indeed, the encroachment on legislative and executive power by the judiciary is a rationale for the proposed judicial reform of 2023–25. The passage of the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty on March 17th, 1992, in the 12th Knesset was pivotal. In addition to being one of the first major legislative measures concerning human rights, this basic law formed the basis for the expanded power of the Israeli Supreme Court (ISC) (Mautner, 2018; Meydani, 2011; The Core International Human Rights Instruments (n.d.)). Three years after the passage of this legislative measure, the ISC’s ruling in United Mizrahi Bank Ltd v. Migdal, 49(4) P.D. 221 (1995) opened the door to substantive judicial review of Knesset decisions. To pass muster, legislation and executive decisions had to be in line with the principles of the Basic Laws as well as other foundational texts.

Various theories aim to explain this change and the surge of other democratic trends in the early 1990s. Nearly all of these theories position Aharon Barak as the key protagonist (Bendor and Segal, 2011; Michelman, 2018; Barak et al., 2021). Some go as far as to hold him solely responsible (Bell, 2023). Barak is perceived by some as a revolutionary with unprecedented influence on Israeli politics, government, and democracy, culminating in his articulation for the court the power of judicial review. This trend had impact well beyond the State of Israel (Weill, 2020; Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer, 2018, 2019).

For others, however, Barak’s legacy was mostly negative, and in particular its implications for the Jewish elements of the state. Rather than celebrating Barak, he is blamed for the degradation of legislative power and effective governance. Bell (2023) highlights Barak’s influence as a way to delegitimize the expansion of the judiciary in the 1990s and advocate contemporary reforms limiting its power. Perceived as a revolutionary who was able to shift the law of the land, Barak is considered the one who upended the system, convoluting substantive law, increasing the discretionary power of judges, and prioritizing the Court’s position on everything from judicial appointments to national policy and budgets (Bell, 2023). Richard Posner argues that the Chief Justice created a degree of judicial power of magnitude not dreamt of even by aggressive justices on the Supreme Court of the United States (Posner, 2007; Roznai, 2018). By emphasizing the novelty of the Constitutional Revolution, Posner positions Barak as a lone, aggressive, and power-hungry judge in pursuit of individual prestige, rather than the good of the nation.

The idea that the story of Israel’s Constitutional Revolution does not stretch beyond its protagonist, Chief Justice Barak, is fundamentally and inherently flawed. Some scholars have tried to fill this gap in literature and public opinion through analysis of other historical moments and political trends. Hirschl (2001) juristocracy argument cites the shift of the global economic order toward neo-liberal policies as a possible factor in Israel’s Cultural Revolution. The global trend toward constitutionalization and judicial empowerment is not primarily driven by a commitment to democracy or social justice, but rather by cooperation between a variety of prominent political actors (2007; 2009). Hirschl explains that “the Court responded to the increased tension between Israel’s dual commitment to universal (democratic) and particularist (Jewish) values by adopting a dual jurisprudential approach” (2009). The emphasis on strategy by political elites and the Court as a whole extends beyond the influence of Barak alone. Mautner (2018) invokes the 1977 upheaval and decline of the Labor as a cause for the renewed debates over democracy and Judaism in the 1990s. Other hypotheses discuss the erosion of public trust in politics and threats to the “dominance of the secular bourgeoisie” toward the end of the twentieth century (Gavison et al., 2000; Sapir, 2009; Hofnung, 1996). Yoav Dotan contributes to this conversation, upholding the idea that the so-called “Revolution” of the 1990s did not, in fact, fundamentally alter the power structure or balance of Israeli politics (2023). Such accounts offer novel, yet incomplete explanations for the Constitutional Revolution, Aharon Barak’s activism, and the social and geopolitical contexts leading up to these changes.

Instead, we would like to argue that the Constitutional Revolution of the 1990s was less a product of Barak’s personal ambitions and more a response to a confluence of pressures both at the global and at the local levels. The geopolitical shift following the Cold War incentivized both Israeli elites and the public to emphasize democratic norms, as aligning with Western liberal democracies became a national priority. This alignment, motivated by the collective will of the general public as well as by all branches of government (and not just the judiciary), tilted the state toward democratic principles—sometimes at the expense of its Jewish character. The shift of the 1990s, rooted in the end of the Cold War, was not driven by any singular domestic actor or power struggle, but rather by a broader historical and international context. It was the global sea change that reshaped Israeli politics, influencing both the elite and the public across the political spectrum. The popular will to align with the winners of the Cold War pushed Israel to embrace democratic principles, even if that meant diminishing the Jewish elements of the state. This shift was reflected in the actions of all three branches of government, including the judiciary. The actions of the latter were a product of the broader public reaction to the end of the Cold War rather than the ones instigating the change.

Situating Barak’s jurisprudence in a macro-political perspective of globalization and the democratization of the post-Cold War era notably builds off work positioning Barak’s long-term influence as a manifestation of existing ideas in Israeli public law. Rather than emerging in isolation, Barak’s judicial philosophy was essentially reflective of existing currents in Israeli legal discourse, particularly around the expansion of judicial review and a shift toward liberal constitutionalism (Jacobsohn and Roznai, 2020; Mak et al., 2013). A critical history of ideas perspective has also been constructed in existing literature to explain the jurisprudence emanating from the HCJ in the 1990s. Mautner (2008, 2018) frames the gamut of rulings handed down by the court within a broader socio-political framework, interpreting judicial activism and a characterized overreach as materializing a legalization of politics and public administration. This trend is evident at the global level as well, following the spread of human rights discourse, the enactment of new constitutions, and the expansion of judicial review internationally in the aftermath of World War 2. There is a connection between judicial behavior and broader systemic factors. The significant erosion of political consensus and a growing reliance on the judiciary to play a major institutional role in managing social and political disputes was central (Meydani, 2023). It is not the individuals that matter as much as many believe, but it is the socio-political arena they participate in which sets their stage. Mautner (2008) and Meydani (2023) presented a critical history of ideas perspective on the place of the HCJ’s 1990s’ adjudication. Barzilai (1998) and Shamir (1990) have set the Court’s behavior in a critical social perspective and post-structuralist analyses of its rulings. The view offered is of Barak’s adjudication in a long-term perspective and as a manifestation of existing ideas within Israeli public law (Jacobsohn and Roznai, 2020). That period’s influence on Israeli society and politics was substantial mainly in the context of globalization and liberalism s. ethnicity and not so much of democratization or post-cold-war issues (Ram, 2024; Grinberg, 2009; Berg, 2023; Bob, 2023). The argument that the Israeli high court is a dependent variable of a 1990s zeitgeist that wishes to keep pace with the democratizing world is novel. Ultimately, placing the HCJ in a larger socio-political and historical context is essential to refuting a limited explanatory mechanism focused on the role of one individual, powerful as they may purportedly be. Such contextual, historical and institutional accounts are essential for a true analysis of the HCJ’s role in the 1990s and a new and much-needed focus on the democratization and globalization of the post-Cold War period and their implications for Israel three decades forth.

While scholarship on the tensions between Judaism and democracy in Israel exists, these concepts are not used as an explanatory mechanism for the numerous political chasms in Israel. We use the constitutive elements of Judaism and democracy in Israel as an axis gauging political attitudes and explaining the key political shifts, currents and conflicts. The contemporary battle over the judicial reform proposed by PM Netanyahu’s government is the culmination of decades of escalating tensions over the proper balance between democracy and Judaism. The reform sheds light on these tensions. Although the reform has been through multiple iterations, the objectives of Netanyahu’s government are clear. The proposed reform aims to swing the political pendulum away from democracy and back toward Judaism. Democracy will not disappear, but the balance will tilt toward Judaism as the key constitutive element. To achieve this shift, the reform includes curtailing the ISC’s power to overrule governmental or ministerial decisions, allowing a simple majority in the Knesset to override Supreme Court constitutional rulings, and removing the legal relationship between MKs and the legal advisers of the Attorney General (Sommer and Braverman, 2024a; Sommer, 2011, 2014).

Ultraorthodox and nationalist parties in Netanyahu’s 2023 government aim to transfer power from the judiciary to the legislative and executive branches to advance their interest in a state with more pronounced religious elements. The ISC has struck down various laws aimed at increasing those Jewish elements on the basis of protecting human rights and civil liberties. For instance, with expanded executive power, the government aims to permit gender segregation in public spaces and discrimination against LGBTQ people by businesses. Those two issues won protection from the court in a series of rulings. The government also aims to provide religious leaders with greater control over Jewish conversions and holy sites. Similarly, the ultraorthodox leadership has secured an agreement with PM Netanyahu to pass a law that enshrines Torah study as a national value en par with military service. This would pave the way for a formal exemption from military service for the orthodox community. The coalition government in 2023–25 and the political movement behind it seek to further the state’s alignment with tenets of Judaism, at the expense of democratic institutions and values.

On the other end of the political spectrum are thousands of Israelis who have protested, demonstrated, and struck in the months since the reform was announced and until the terrorist attack of October 7 2023, when the Israel-Hamas war started. On this side of the political spectrum are people from both the leftwing and rightwing of Israeli politics, sharing a common aspiration to protect, if not increase, the democratic elements of the state, with a special emphasis on checks and balances and an independent judiciary. Those opposing Netanyahu’s proposed reform espouse democratic institutions and the limitation of the role of Judaism in government and everyday life. A simplistic view of right vs. left-wing politics falls far short of capturing the more fundamental currents driving Israeli politics.

We offer the axis ranging between the two constitutive elements of Judaism and democracy as the foundation for understanding Israeli politics. In a 2018 Congressional Research Service study of political rights and civil liberties ratings since 1972, the sharpest increase in political rights and civil liberties occurred in the 1990s (Weber, 2018). This was a global trend toward democratization following the end of the Cold War. As the Soviet Union collapsed, the United States emerged as a global hegemon and trendsetter of norms of government worldwide. With a victorious United States side by side with increasingly strong Western European democracies across the Atlantic, liberalism and democracy became core tenets of world order. Soon, a global desire to align with this ideology—to be on the right side of history—emerged (Suri, 2012; Mak et al., 2013). As a result, governments worldwide trended heavily toward democratization. Establishing, or reinforcing, democracy presupposed a shift in political attitudes and institutions.

The State of Israel was no exception to this post-Cold War project of democracy. Rather, we argue that the 1990s had a decisive influence on the political system and on Israeli society writ large. This influence, however, is often underappreciated or outright ignored, in some cases to serve political goals. We see such trends well beyond the expansion of the Israeli judiciary. Those trends are evident in the surge of liberal democratic values in Israeli society, public policies, basic laws, democratic institutions, foreign policy, international engagements and more. The impulse to associate with the winners of the Cold War, Western liberal democracies, quickly absorbed Israeli politics and informed legislative goals. Israel aspired to achieve international recognition as a Western liberal democracy, even more so than it had been during the Cold War. We demonstrate the correlation between the end of the Cold War, the global trend toward democracy, and the change in Israel through extensive analyses of minutes from legislative committee meetings and Knesset deliberations around the Basic Laws, national and international speeches, and commitments in the Israeli legislature, the Knesset, to global protocols on human rights. What is more, Israel’s close relationship with the United States in the 1990s is also inextricably linked with various post-Cold War global trends (Fact Sheet U.S.-Israel Economic Relationship, n.d.). With the United States as a global hegemon and victor of the Cold War, liberal democratic values emerged as a form of political currency, highly coveted around the world, Israel included. Naturally, increased geopolitical cooperation between Israel and the West, which also went beyond US-Israel relations and pertained to EU-Israel links as well, informed the political evolution of the state at the domestic level and at the level of its democratic institutions. The balance between Judaism and democracy in Israel was forever changed.

Westernization is not necessarily linked to a single nation. Israel’s cultural, political, and institutional changes joined a global trend toward Western democracies. Yet, given the United States’ standing after the Cold War and its strong alliance with Israel, the trend toward Western ideals of democracy in Israel is frequently framed Americanization. In the 1990s, Israel experienced “a zeitgeist of Americanization of its entire social consciousness demonstrated through personal ambitions, materialism, popular culture, and moral conduct” (Aronoff, 2000). Large scale American influence was an essential element of the transformative trends swaying Israel’s socio-political trajectories. That said, influence from other countries throughout the Western world was also apparent in Israel’s transformation. For instance, in October 1992, federal courts in Canada forced the armed forces to lift a ban excluding homosexuals from serving in the military. Likewise, in November 1992, Australia’s government voted to lift an almost identical ban. Roughly a year later in June 1993, Israel’s military lifted its ban on homosexuals serving following dramatic Knesset hearings on the subject (Belkin, 2003). This is a key example of the spread of liberalism around the globe and the political tendencies it encompassed inspiring Israeli governance in the aftermath of the Cold War. Democratization and liberalization generally occurred conjointly. Thus, trends like these toward liberalization disseminated side-by-side with trends comprising democratization.

As we establish the impact of post-Cold War global trends on Israeli politics and culture, we aim to refute the notion that the Supreme Court, and CJ Barak at the helm, should be attributed outsized responsibility for the trend that seized the country. Rather, we hold that the ideas that fueled the expansion of the judiciary in the 1990s were not novel at the time of their implementation, nor were they a product of the judiciary overstepping its boundaries and aiming to expand its sphere of influence. In political discourse of the decades prior, numerous Israeli judges expressed the need for an independent, authoritative judiciary. In the 1970s and 1980s, Israeli justices examined extra-statutory sources of law and expanded the function of the court (Woods, 2009). These largely democratic ideals were integral elements in Barak’s vision for Israel; they were also part of political discourse prior to the shift in the 1990s. In Bergman v. Minister of Finance, the practice of judicial review was established. Bergman marked the beginning of an attitudinal shift driven by a new generation of justices who in law review articles, interviews, and judicial rulings, signaled an heightened interest in rights cases. Thus, the context for Barak’s work and the Constitutional Revolution had already existed within Israeli society in decades prior. It was post–Cold War global politics that galvanized these latent attitudes and that instigated this change, which was made possible not because of judicial aspirations, that were nothing new, but by the popular will and the bottom-up movement toward democratization and Americanization it fueled.

We posit a tripartite argument. First, the relationship between Judaism and democracy provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding Israeli politics and should replace the rightwing-leftwing dichotomy. Second, Israel’s political history is characterized by constitutional vagueness, where the balance between the Jewish and democratic elements, and the boundaries that define each, were never fully formalized within an entrenched legal framework. This lack of formalization has contributed to the durability of Israel’s political system. Third, the end of the Cold War initiated a transformative period in the 1990s, driven by a desire to align with Western ideals of democracy, a trend that resonated globally, including in Israel. To test this thesis, we examine the actions of different branches of the Israeli government during the 1990s. We aim to demonstrate empirically that the judiciary was not the sole driver of the shift toward strengthening democratic elements in the nation, rather it was a platform used to advance a current fueled by popular will. Accordingly, we propose the following three hypotheses, which focus on the elected branches, to substantiate the contention that the trend toward Western liberal democracy was not a judicial project driven by appointed justices, but by elected officials held accountable to the general public with its strong desire for such a shift toward democracy:

H1: Joining the global shift toward democracy in the post-Cold War era, legislative deliberations by the Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee in the 1990s concentrated on Western democratic values.

H2: Speeches given by international leaders in Israel as well as by Israeli leaders to the international community promote the expansion of democratic values and global cooperation.

H3: Trends in Israel’s ratification of UN core international human rights treaties in the early 1990s indicate the nation’s desire for international recognition as democratic and progressive.

Data and methods

We analyze primary sources from the 1990s, including legislative deliberations, both domestic and international speeches delivered by political leaders, as well as trends in the ratification of UN pacts and declarations in the Israeli unicameral legislature, the Knesset. Qualitative examination of textual content as well as quantitative analyses of the frequencies of words and phrases allow us to examine the temporal gap between the passage of international treaties and Israel’s ratification of those treaties. The temporal trends are analyzed as well.

Within Knesset archives, empirical insights from legislative sessions leading up to the passage of the 1992 Basic Law offer valuable context. Through analysis of minutes, we reveal prevailing attitudes surrounding democratic principles, the judiciary, and the Basic Laws. This legal instrument, often seen as a harbinger of amplified democratic ideals and rights, was a focal point of discussion.

Our research methodology for both the Knesset minutes and the international speeches includes a comprehensive multi-step process. We gathered a sample of Knesset session minutes by searching official Knesset archives of committee meetings. We selected documents from the Constitution, Law, and Justice committee of the 12th Knesset. Since it handled governmental procedures, the Constitution, Law, and Justice committee is most relevant to our study. The 12th Knesset lasted from 1988 to 1992, during the passage of the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty. Using their titles and descriptions, we isolated 23 of the 371 initial documents. We selected these minutes based on their relevance to Constitutional Reform, collaboration with the judiciary, and the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty. A document was deemed relevant if it included any or all of the phrases “courts law,” “rights of man,” “rights of the individual,” or “Hague Convention” in its title or listed agenda. We excluded one document with “rights of the individual” in the title since it exclusively discussed traffic laws.

We then translated the selected Knesset documents, all initially in Hebrew, into English using Google Translate. Once translated, we used a WordCloud processing system to find the most frequently used words in each of the documents. We applied this same WordCloud processing step to the international speeches we selected. WordCloud technology facilitated the comparative analysis that allowed us to identify commonalities among minutes and speeches. The results from this process—the outsized discussion of democratic principles by the 12th Knesset—prompted our further investigation of key political speeches.

During the early 1990s, Israel received encouragement—if not pressure—to commit to democratic principles from within as well as without. Speeches by Israeli and international political leaders between 1991 and 1994 are highly indicative. We analyze these speeches in comparison to the United Nations definition of democracy in order to identify alignment with the international understanding of democratic principles. In late October 1991, PM Shamir spoke at the opening of the Madrid Conference. Hosted by Spain and co-sponsored by the United States and Russia, the conference aimed to revive peace efforts in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict (The Madrid Peace Conference, 1992).

During his speech, PM Shamir condemns Arab violence and pleads for peace in the Middle East. Similarly, Minister Meridor encourages international and regional peace in his speech at an Anti-Defamation League conference in Washington, D.C. At a last-minute appearance at the conference, Meridor speaks on the Persian Gulf War and the lessons Israel, and the global community can take from the conflict. Both speeches contain references—subtle and explicit—to the project of expanding democratic principles in Israeli politics. By analyzing the language in these speeches, we aim to test whether the desire to pursue more democracy was reflected not only in the actions of Israeli legislators and justices, but also in the words of leaders in the executive, all squarely within the rightwing coalition government in power at the time.

To test the role of the executive branch in growing Israel’s international standing as becoming increasingly democratic, we also delve into speeches by international leaders intended for an Israeli audience. In the early 1990s, as Israel redefined its government and understanding of human rights through the Basic Law, different nations encouraged the project of democracy. President Zhelyu Zhelev of Bulgaria joined this trend when addressing the 13th Knesset on December 6, 1993 (Address of the President of Bulgaria, Zhelyu Zhelev to the Knesset Plenum Jerusalem, n.d.). Speaking directly on the impact of the Communist system on the international community, President Zhelev’s commentary represents a region uniquely impacted by the Cold War and the project of democracy, namely Eastern Europe. Analyzing this speech further highlights the global desire for and promotion of democracy and how Israel became closely associated with this trend. Complementing the demise of communism in Zhelev’s speech, is the praise for democracy in President Bill Clinton’s address to the 13th Knesset as well in 1994 (Zhelev, 1993). In this speech, President Clinton compliments Israel for its movement toward democracy and commitment to its relationship with the United States. Israel is increasingly aligning itself with Western liberal democracies and for this reason, wins praise from the president of the new hegemon on the world stage, the United States of America.

We selected these speeches from many based on their content, timing, and deliverer. While each speech revolves around Israeli foreign relations, they all refer to different political events or narratives and are given by Israeli and foreign leaders. In addition to contextualizing the speeches and some of their content, we provide tables and data to quantify the occurrence of terms related to democratic values in those texts.

The analyses of both key speeches and Knesset meetings highlight democratic buzz words. The purpose is to investigate the infusion of democracy into the discourse in these primary documents, representing the actions of all branches of government, controlled by different political parties. Words in this category are defined using extensive scholarship on terminology associated with pivotal components and virtues of democracy. This includes the use of checks and balances and the importance of a strong and independent judiciary (Montesquieu, 1748). In contemporary global politics, independent judiciaries play a significant role in preventing anti-democratic regime changes toward authoritarianism (Gibler and Randazzo, 2011). Also included are words containing “court” and “judge.” Similarly, we also identify “justice” and “rights” as these concepts are instrumental to democracy.

To complement those methods, and provide some cross validation stemming from the heart of legislative work, our final method of analysis pertains to international treaties and their ratification. Throughout the 20th century, the United Nations (UN) passed a series of declarations and resolutions related to concepts and ideals of human rights. The declarations began in 1966 and continue to the present day. Once the UN passes the resolution, it is sent to member nations to sign and ratify. Signatures create an obligation in that nations are expected to refrain from behaviors that would violate the purpose of the treaty; once ratified, however, a state is legally bound to implement the convention or protocol (United Nations, n.d.). Many nations, notably Spain and France, have histories of both signing and ratifying treaties within a year. Israel, however, did not follow this trend.

Of the numerous international protocols and declarations, the UN designates nine as core international human rights treaties. Given their global and value-based significance, we focus on signature and ratification data from these nine treaties. Of these treaties, seven were passed before or in 1990; the other two were passed in the 2000s and are not used in our data. Yet, we show passing, signing, and ratifying dates for all of the core treaties. We analyze temporal gaps between signature and ratification. Quantifying the spike in Israel’s participation in global treaties in the 1990s provides another perspective on the nation’s shift toward democracy, originating from the elected branches in response to the popular will, rather than from the judiciary, where decisionmakers (justices) are appointed rather than elected.

Results

Knesset records, members, and minutes

Analyses of Knesset meetings demonstrate legislative attention to law, judges, the court system and individual rights throughout the tenure of the 12th Knesset. Many of the deliberations in the legislature, for instance, centered on the interpretation of terms such as “human dignity” and “human rights,” alongside conversations about the obligations and responsibilities of the state toward the citizens. Notably, members of the Knesset (MKs) representing diverse perspectives consistently invoked and advocated values traditionally associated with democracy and Western political philosophy. It was not about leftwing politics vs. rightwing. Rather, it was about a strong popular will to boost the democratic elements of the nation. Minutes taken from Knesset meetings demonstrate a pattern of deliberation around the values and structures of Western political institutions, as well as the democratic principles inspired by the end of the Cold War. Our analyses of multiple Knesset sessions reveal this to be a consistent trend.

Another salient theme in Knesset records is how Israel is aligned with American political values, revitalizing the relationship between the two. In one of the most noteworthy deliberations of the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee of the Knesset, on April 15, 1992, Minister of Justice Dan Meridor referred to the heightened strategic and military cooperation between the United States and Israel as “unprecedented” and stated that “there were no such close relations in past years at the military-strategic level.” Ultimately, the strengthened partnership was both an incentive for and a product of Israel’s embrace of democratic principles and institutions.

The Inside the Knesset symposium on Israeli politics in Washington D.C. provides further evidence. This was sponsored by Jewish philanthropic organization, United Jewish Appeal and took place on March 15, 1992—just 2 days before the 12th Knesset passed the Tenth Basic Law of Israel. It featured four leading Knesset members: Chaim Ramon and Avrum Burg of the Labor Party, Yoash Tsidon of the Tsomet Party, and Reuven Rivlin of the Likud (C-SPAN, 1992). Throughout the roughly 100-min-long forum, numerous moments highlighted the Knesset’s consensus regarding the virtues of boosting Western liberal democratic elements in Israel. In his opening remarks, Avrum Burg stresses Israel’s democratic character and the demand to strengthen its democratic institutions, proclaiming, “…we are the only democracy in the Middle East, we are the youngest democracy in the Middle East, and we are in a way the most fragile democracy in the Middle East.”

Subsequently, and despite being affiliated with the opposing political faction, Reuven Rivlin of the Likud emphatically expands on Burg’s praise. Using biblical references, he states,

I must tell you, I must tell you, I must tell you we are a great democracy. Israel is a great democracy and it should be appreciated for that… when Moses took us, the children of Israel, from Egypt…he took us to Canaan. And there is no water there, no oil, no other sources but democracy.

Rivlin not only hailed the overall idea of democracy, but expressed support for efforts to strengthen Israel’s democratic institutions. In response to Tsidon’s comments highlighting anticipated large-scale reforms to Israel’s political system, Rivlin set forth his prognosis for the upcoming years in Israel and recognized the severe threat and extreme nature of opposition to democratization. Rivlin stressed:

I must say that the extremist parties realize that if they do not let such laws pass, something is going to happen in the cultural war in Israel, and they are going to lose…We have to wait a few years and then to, not to separate state and religion, but to manage to pass those laws in order to bring about a basic law that will eventually lead us to having a constitution.

Rivlin was an influential figure in the Likud Party and went on to serve as the tenth President of Israel from 2014 to 2021. His praise for democracy as foundational to the Zionist project speaks volumes. Most of his commentary in the forum served to represent his unabashed conservative perspective on Israel’s internal and external disputes. Yet, the importance of strengthening Israeli democracy did not contradict this perspective. Indeed, it only complemented it. Lastly, this enthusiastic pro-democracy rhetoric at an event in the United States delivered to a mostly American crowd also sheds light on Israel’s underlying aspiration to be viewed as closely affiliated with the United States and with Western liberal democracies, mostly in Western Europe. The choice of rhetoric of all four Knesset members and the motivations behind Israel’s democratization at the time are all inspired by this aspiration.

Speeches by political leaders

Analyses of speeches by Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, Minister Dan Meridor, President of Bulgaria Zhelyu Zhelev, and United States’ President Bill Clinton rely on the UN definition of democracy. We track those principles in the speeches’ texts. According to official documents, democratic governance is “a set of values and principles that should be followed for greater participation, equality, security, and human development. Democracy provides an environment that respects human rights and fundamental freedoms, and in which the freely expressed will of people is exercised. People have a say in decisions and can hold decisionmakers to account. Women and men have equal rights and all people are free from discrimination” (“United Nations”). Accordingly, our method tracks explicit and implied promotion of global cooperation, diplomacy, and free market.

Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir’s speech at the opening of the Madrid Conference in 1991 demonstrates the desire for alignment with the United States and Western democratic principles. His remarks advocate peace and negotiations between Israel and its Arab neighbors, yet they invoke the broader global context. Shamir explains that “In their war against Israel’s existence, the Arab governments took advantage of the Cold War. They enlisted the military, economic, and political support of the Communist world against Israel, and they turned a local, regional conflict into an international powder-keg” (1991). PM Shamir affirms Israel’s alliance with the West by situating Arab leadership in connection with (and Israel in opposition to) the Soviet Union. This alliance leads to support from the conference’s sponsors and hosts, the United States and Spain. It also implicitly condemns Communism. In the post-Cold War era, such rhetoric—linking Israel with the West and rebuking Communist ideology—speaks volumes.

Framing Israel as a nation in alignment with the West contextualizes Shamir’s goals for the region. The PM expresses his envy of European nations, praising them for “discussing the good of the community, cooperating in all matters, acting almost as one unit” despite the pain of the World Wars. Such admiration of community and regional collaboration is aimed, inter alia, to please European nations. Global politics influences Shamir’s praise of the nations that exemplify Western liberal democracy in the years following the Cold War. In addition to building a global community, Shamir endeavors to turn the Middle East into “a center of cultural, scientific, medical and technological creativity” through periods of “great economic progress” (Shamir, 1991). These goals of regional progress reflect the paths charted by Western democracies as they emerged from the World Wars. They also mirror the democratic value of human development as expressed by the UN.

Minister Dan Meridor’s speech on the Persian Gulf War at the 1991 Anti-Defamation League conference in Washington, D.C. similarly emphasizes Western liberal democratic values. Throughout his speech, Meridor highlights the strength and status of the United States. In relation to the events of the Gulf War, he praises the United States as “the only superpower in the world that was ready not only to talk the talk but also to walk the walk” (3). He attributes American action during the war to American global status at the time. Meridor’s assessment of America’s involvement in the Gulf War demonstrates reverence for the United States. Speaking in the United States sends a message to Israelis and the global community about the positive relationship between the two nations. Coupled with the sentiment of reverence, he also demonstrates affinity with America’s values.

Minister Meridor does not stop at praising the strength of the United States. Like PM Shamir, he highlights American cooperation and international institutions. Going beyond the United States, he affirms that “the Western world has wonderful organizations of intelligence in America and Israel and the West” (3). To his American audience, this reads as praise and amity. To an Israeli constituency, this indicates Meridor’s political intentions. Urging talks in the Middle East to uphold the legitimacy of a Jewish state requires widespread commitment to the required diplomatic effort, including from the United States. Therefore, this praise indicates alignment with American tactics and values. Emphasizing the value of American political tactics, Meridor’s speech calls on the United States to use their power and recognition as a global hegemon to promote Israeli policy and enhance diplomatic efforts.

While for PM Shamir and Minister Meridor the key was the international community’s perception of Israeli democracy, President Zhelyu Zhelev and President Bill Clinton focused on encouraging the democratic trajectory within Israel. Addressing the Knesset on December 6, 1993, on his first official visit to Israel, Bulgarian President Zhelev celebrated relationship between the two nations. A Communist nation since 1947 and throughout the Cold War, Bulgaria was a close ally of the Soviet Union (Nehring, 2022). However, following the end of the war, the nation shifted toward democratic governance, supported by U.S. Support. The East European Democracies Act (SEED) of 1989 was pivotal (U.S. Department of State Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, 2008). Zhelev, thus, epitomizes the demise of Communism and the rise of Western liberal democracies.

In his speech, President Zhelev highlights the importance of pursuing democratic governance in the wake of the Cold War. Discussing the shifting global order, he explains that since the collapse of the Communist system put an end to the division of the world into ideological camps and blocs, the world is more open to a new kind of communication and is willing to examine new methods of free development.1 In this interpretation, President Zhelev associates increased communication and development with Western ideals. He also indicates that the fall of Communism incited a newfound openness to human development and democracy and a strong preference for an alignment with and favor from Western democracies.

With this optimistic view on the impact of the end of the Cold War, President Zhelev urges Israel to continue to pursue democracy. He expresses his hope that “Israel is willing to participate, with all its force, in the process of transitioning to democracy and a market economy, which is currently underway in a number of Eastern European countries, including Bulgaria.” In this statement, he groups Israel with Bulgaria, a nation undergoing a transformation to democracy under the aegis of the United States.

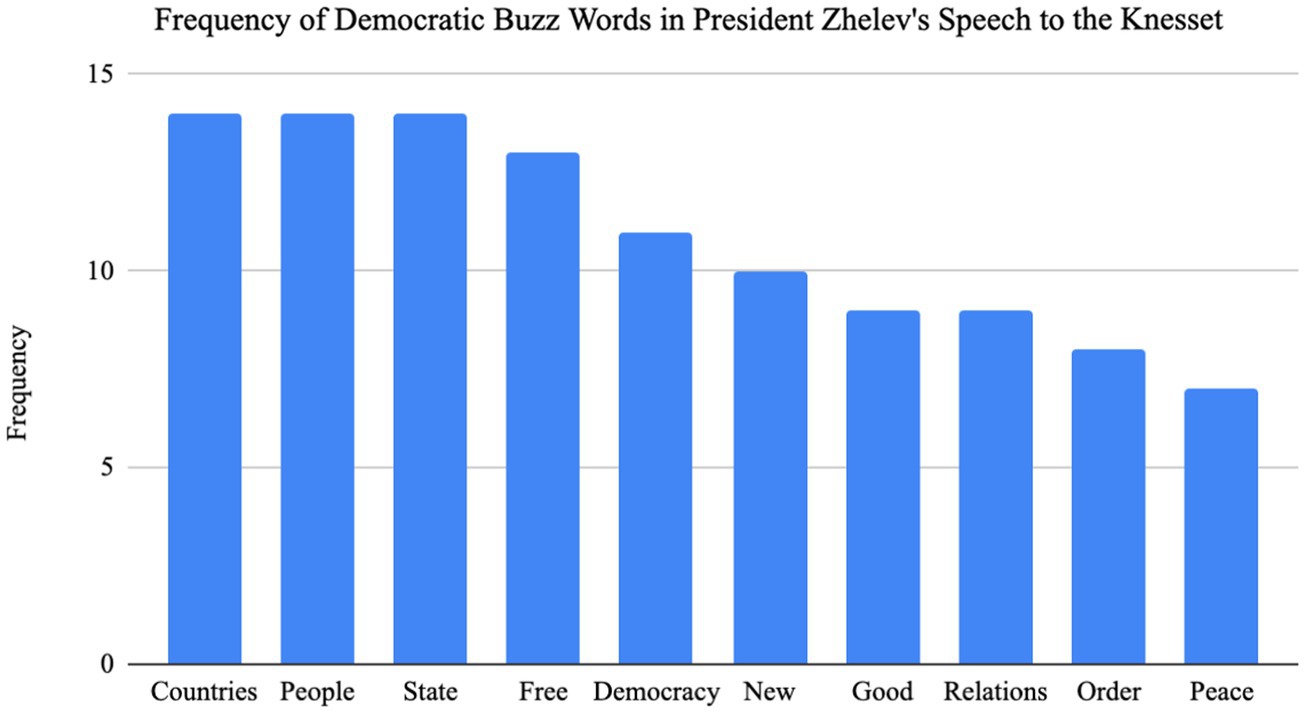

Analysis of the frequency of democratic buzz words in President Zhelev’s speech furthers underlines the centrality of freedom, democracy, and the new world order following the Cold War. Excluding terms like “Israel” and “Bulgaria,” Figure 1 shows the frequencies of specific, democracy-related words in the speech.

During his 1994 address to the 13th Knesset in Jerusalem, like President Zhelev, United States President Bill Clinton treasures the importance of promoting democratic ideals in Israel. From the outset, he emphasizes Israel’s system of government, thanking the PM and Knesset for giving him “the opportunity to address this great democratic body where people of different views can freely express their convictions.” Drawing a connection between the Knesset and the US legislature, the US president added “I feel right at home.” This praise serves as a symbol of progress in Israel’s path toward international recognition as a liberal democracy.

Clinton draws further parallels between the United States and Israel, explaining that “Like your country, ours welcomes exiles, a nation of hope, a refuge…all committed to living free and building a common home.” These values of cooperation and freedom symbolize a common commitment to democratic values. In this case, Clinton emphasizes their roles as a haven for diverse voices and perspectives.

In addition to linking Israel and the United States, Clinton praises Israel’s progress in upholding democracy amid regional challenges. He declares outright that “Even without secure borders, you have secured the blessings of democracy. Despite turmoil and debate, it remains the best system.” He explicitly promotes democracy to the Israeli legislature—implying these values as a prerequisite for Israel’s relationship with the United States. With this understanding, Clinton declares that “Israel’s survival matters not only to our interests but to every value we hold dear.” On the heels of the Cold War, these values include “security, stability, and prosperity” fostered by democratic governance.

Clinton concludes his speech by assuring Israeli legislators of American support in the region. However, his commitment clearly hinges on Israel’s continued promotion of democratic ideals. Speaking to the Knesset, Clinton transparently promotes liberal democracy as the best system—and the one guaranteeing international support for Israel.

International treaties

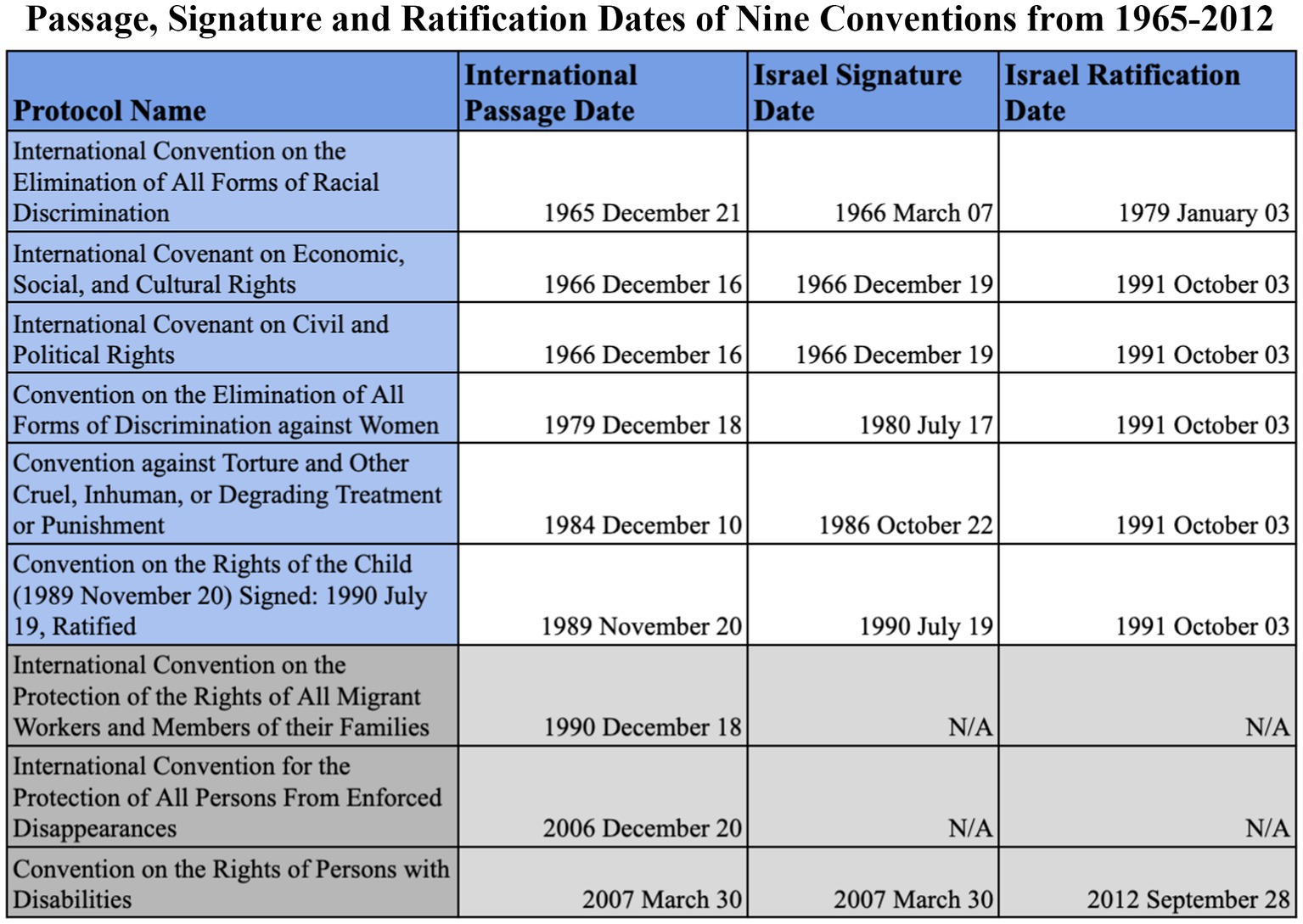

Figure 2 lists the names of the treaties, the date they passed in the UN, and the dates each was signed and passed in Israel. The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances and The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities passed in the 2000s, so they are excluded from the analyses here. We also do not use the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, since Israel has neither signed nor ratified this treaty.

The signature and ratification of these treaties alone demonstrates a holistic acceptance of international rights standards; both the executive and legislative branches are required for this process. However, the chart indicates a clear pattern of ratification. The International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) were all signed on different dates, within 2 years of international passage. Enforcing equal rights, civic participation, and respect for the individual, these treaties epitomize the values of Western liberal democracy. However, the Israeli legislature did not ratify any of these four seminal human rights treaties, nor the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) until October 03, 1991—even before the passage of the Basic Law.

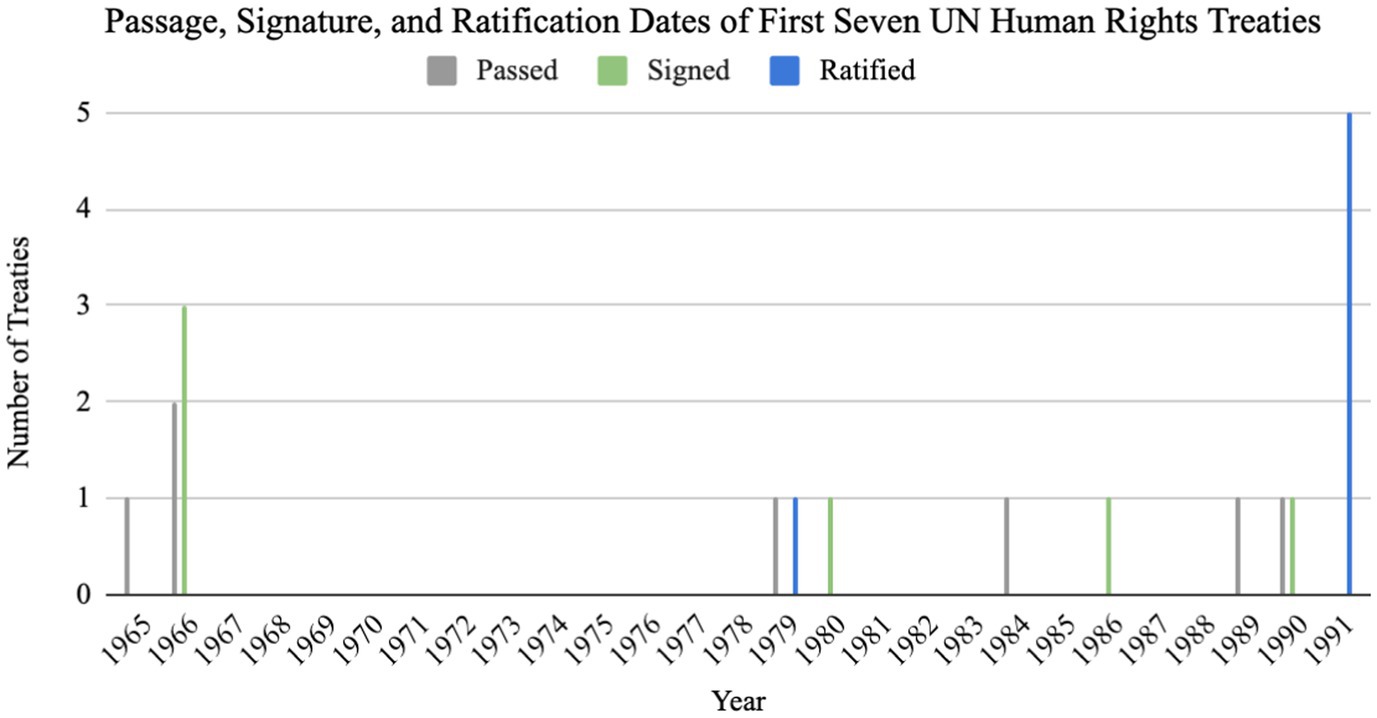

As Figure 3 indicates, it took the Knesset 25 years to ratify the ICESCR and ICCPR. CEDAW and CAT took 12 and 7 years, respectively. The temporal gap between the international passage (and executive approval) of these treaties and their ratification in the Knesset indicates the lack of legislative commitment to fully comply with international standards of human rights. This reluctance, however, disappeared in 1991—after the end of the Cold War—when all branches of government, on the strong tailwinds of popular will, scrambled to clearly align Israel with Western liberal democracies.

Figure 3. Knesset passage, signature and ratification dates of first seven UN human rights treaties.

In the 1990s, alignment with the United States, other Western democracies, and the UN meant recognition as being on the winning side of the Cold War. Ratifying these treaties—which serve to monitor and uphold civil rights—allowed Israel to demonstrate on the global stage its commitment to those values. It also illustrates the democratic ideals of the 12th Knesset. This legislative position was distinctly separate from influence of other branches, and certainly from any judicial influence. The Knesset alone has the power to ratify international treaties and when to do so. The reification and its timing could not be more indicative.

Discussion and conclusions

The judicial reform proposed in 2023 is often cast as a counter movement to the judicial revolution of the 1990s, spearheaded by Chief Justice Aharon Barak. In this view, the reform is seen as a means to correct a judicial overreach. A judicialization of politics perspective can be similarly constructed to frame the court’s perceived overreach through a documented course in which the legal system replaces other authorities in a state in regards tied to personal interests (Meydani, 2023). Aiming to maintain Jewish values in government, the reform would curb the courts’ perceived excess of power and restore balance between the judiciary and the legislature. We propose an alternative view.

As we show, the transformation of the 1990s was not a judicial endeavor. Rather it was deeply rooted in global geopolitical shifts and stemmed from popular will in Israel. The tensions between the Jewish and democratic elements in Israel, which have existed since the country’s establishment, stand at the basis of most past and modern-day political points of contention. The duality between Judaism and democracy underlies the societal choices and struggles that informed both the Constitutional Revolution and the 2023 reform. It also explains many of the key political junctures in between.

CJ Barak played a pivotal role in reshaping the Israeli legal landscape during the 1990s, underscoring the role of the judiciary as a check on legislative and executive power (Meydani, 2023). However, attributing the constitutional revolution to Justice Barak oversimplifies a more convoluted political story. To suggest that Barak alone led the constitutional revolution overlooks the comprehensive work of numerous political actors. These actors laid the groundwork for a transformation in Israel that was influenced by global trends.

The Constitutional Revolution was inextricably linked with the end of the Cold War and the international changes that followed. What is more, it happened side by side with a host of changes put into motion by different branches of the Israeli government. All were fueled by a strong popular will to increase the democratic elements of the Jewish nation and place it squarely among the winners of the Cold War, namely Western liberal democracies.

The end of the Cold War was a watershed event marking a turning point in international relations. The triumph of Western liberal democracy prompted a reevaluation and recalibration of political will and wants across the globe. The Israeli geopolitical landscape shifted with the rest of the world—changing the ideological currents that had guided the governments’ policies and aspirations. Within this larger global context, Israel, like many other nations, found itself at a political crossroads. As the Soviet Union dissolved, the allure of Western liberal democracy—as an emblem of American hegemony—became undeniable (Aronoff). In the case of Israel, however, the fact that democracy had always competed against an alternative of Jewish identity for the nation entailed a more complicated process between those two constitutive elements. In this process the choice of democracy, while in line with the global trajectory, was at the expense of Jewish elements of the nation.

Characterizing Israel’s response to this historic moment as judicial maneuver is historically false. It was a choice to align with the victorious powers in the grand global ideological contest of the 20th Century. The desire to be on the right side of history drove Israelis, the public and elites alike, to demonstrate allegiance to Western democracy. This impulse impacted Knesset members and political leaders, informing their political focus and language around the turn of the decade. Minutes from Knesset meetings, international speeches, and patterns of Israel’s ratification of international treaties demonstrate the desire to align with Western democracy, even if it meant shifting the balance away from certain Jewish elements.

This perspective challenges the widespread claim that the proposed reform of 2023–25 is merely a response to the perceived judicial overreach of the 1990s. While the reform may adjust the balance of power between the judiciary and other branches of government, framing it solely as a reaction to the Constitutional Revolution is limiting. Such a view overlooks the intricate historical trends—nationally and internationally—that have shaped Israeli political identity for decades. With a holistic view of international and national politics, and the links between the two, the current reform is another step in setting the delicate balance between the two constitutive elements of the nation—its Jewish and democratic elements.

Our perspective does not invalidate the significance of Chief Justice Aharon Barak’s contributions to Israeli jurisprudence. His role in promoting a rights-based approach and expanding the scope of judicial review was critical (Bell, 2023). However, our analyses underscore that the actions of the Chief Justice were not isolated, unilateral endeavors. Rather, the Constitutional Revolution was closely intertwined with the post-Cold War era—a time profoundly influenced by the United States’ victory and the global shift toward Western democratic ideals. The transformation of the 1990s was not merely a judicial revolution; it was a societal recalibration that echoed the global realignment after the Cold War (Levitsky and Way, 2005).

Israel’s pursuit of a stronger democratic identity, aligning itself with the Western liberal democratic ethos, was a response to shifts in the international political order. The desire to be on the winning side of history drove Israeli society to prioritize the democratic elements of its national identity, including in the judiciary. As we navigate the current landscape of the proposed 2023–25 reform, we argue that it is critical to consider the historical context that shaped Israel’s identity and political choices. The reform’s intentions may be ostensibly directed toward restoring the balance of power. Yet, viewing it through this myopic lens fails to capture key nuances in Israeli politics. Acknowledging the broader historical dynamics of the 1990s reveals the intricacies of Israel’s governmental practices and interplay between the nation’s Jewish and democratic elements.

The transformations of the 1990s in Israel were far more than a judicial initiative; they represented a profound societal response to global shifts and political dynamics triggered by the end of the Cold War. The Constitutional Revolution emerged as a pivotal aspect of a multifaceted domestic effort to navigate these changes, steering the nation along the axis of its Jewish and democratic identity. Israeli elites and the public sought alignment with the Cold War victors—Western liberal democracies—whose ideological and political dominance reshaped global norms and aspirations. This alignment was evident in the actions of all branches of government, the deliberative processes shaping policy, Israel’s international engagements, and the perception of Israel by global leaders as a thriving Jewish democracy. Driven by the sweeping transformations of the post-Cold War era, the Israeli public, together with leaders in the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary, deliberately strengthened the nation’s democratic foundations, affirming their commitment to a shared global vision of liberal democracy.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Author contributions

US: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Aharon Barak. (n.d.). Israeli missions around the world. Available at: https://embassies.gov.il/MFA/AboutIsrael/state/Personalities/Pages/Aharon%20Barak%20-%20President%20of%20the%20Supreme%20Court.aspx

Arian, A., and Shamir, M. (2008). A decade later, the world had changed, the cleavage structure remained: Israel 1996-2006. Party Polit. 14, 685–705. doi: 10.1177/1354068808093406

Aronoff, M. J. (2000). The ‘Americanization’ of Israeli politics: political and cultural change. Israel Stud. 5, 92–127. doi: 10.2979/ISR.2000.5.1.92

Barak, N., Sommer, U., and Mualam, N. (2021). Urban attributes and the spread of COVID-19: the effects of density, compliance, and socio-political factors in Israel. Sci. Total Environ. 793:148626. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148626

Barzilai, G. (1998). Courts as hegemonic institutions: the Israeli supreme court in a comparative perspective. Israel Affairs 5, 15–33. doi: 10.1080/13537129908719509

Belkin, A. (2003). Don’t ask, don’t tell: is the gay ban based on military necessity? Available at: https://escholarship.org/content/qt0bb4j7ss/qt0bb4j7ss_noSplash_32e36ce037d3674c847732b05078dc83.pdf?t=krndrq

Bell, A. (2023). Israel is in need of judicial reform: a deep dive into the dynamics of the case for judicial reform. Sapir J. 9, 1–6.

Bendor, A. L., and Segal, Z. (2011). The judicial discretion of justice Aharon Barak. Tulsa Law Rev. 47, 465–484.

Berg, R. (2023). Israel judicial reform explained: what is the crisis about? BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-65086871

Bob, Y. J. (2023). “Tens of thousands” will stop showing up for duty, IDF reservist warns. The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Available at: https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/article-735245

Cohen, A. (2018). Likud’s rise to power and the ‘democracy in danger’ fearmongering campaign: rhetoric vs. facts. Israel Affairs 24, 1073–1092. doi: 10.1080/13537121.2018.1530429

C-SPAN. (1992). Election in Israel: United Jewish Appeal sponsored a symposium on Israeli politics. The forum is entitled, ‘Inside the Knesset’. Available at: https://www.c-span.org/video/?25030-1/election-israel

Doron, G. (2005). Right as Opposed to Wrong as Opposed to Left: The Spatial Location of “Right Parties” on the Israeli Political Map. Israel Studies 10, 29–53.

Fact Sheet U.S.-Israel Economic Relationship. (n.d.). U.S. Embassy in Israel. Available at: https://il.usembassy.gov/our-relationship/policy-history/fact-sheet-u-s-israel-economic-relationship/

Forman-Rabinovici, A., and Sommer, U. (2018). An impediment to gender equality? Religion’s influence on development and reproductive policy. World Dev. 105, 48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.024

Forman-Rabinovici, A., and Sommer, U. (2019). Can the descriptive-substantive link survive beyond democracy? The policy impact of women representatives. Democratization 26, 1513–1533. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1661993

Gavison, R., Kremnitzer, M., and Dotan, Y. (2000). Judicial activism: for and against: the role of the high court of justice in Israeli society. Jerusalem: Magnes, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Gibler, D. M., and Randazzo, K. A. (2011). Testing the effects of independent judiciaries on the likelihood of democratic backsliding. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 55, 696–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00504.x

Weber, M. A. (2018). Global Trends in Democracy: Background, US Policy, and Issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service.

Gold, H., and Tal, A. (2023). Half a million Israelis join latest protest against Netanyahu's judicial overhaul, organizers say. CNN. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/03/12/middleeast/israel-protests-benjamin-netanyahu-intl/index.html

Grinberg, L. (2009). Politics and violence in Israel/Palestine: democracy versus military rule. Routledge studies in Middle East politics. New York: Routledge.

Hirschl, R. (2001). The political origins of judicial empowerment through constitutionalization: lessons from Israel's constitutional revolution. Comp. Polit. 33, 315–335. doi: 10.2307/422406

Hofnung, M. (1996). The unintended consequences of unplanned constitutional reform: constitutional politics in Israel. Am. J. Compar. Law 44, 585–604. doi: 10.2307/840622

Horowitz, D., and Lissak, M. (1989). Trouble in utopia: the overburdened polity of Israel : State University of New York Press.

Lederman, A. (2021). Knesset elections 2021: a guide to Israel's political parties. Israel Policy Forum. Available at: https://israelpolicyforum.org/2021/03/10/knesset-elections-2021-a-guide-to-israels-political-parties/

Levitsky, S., and Way, L. A. (2005). International linkage and democratization. J. Democr. 16, 20–34. doi: 10.1353/jod.2005.0048

Liebman, C. S., and Shokeid, M. (2018). Israeli Judaism: the sociology of religion in Israel. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Mak, M. A., Sidman, A. H., and Sommer, U. (2013). Is certiorari contingent on litigant behavior? Petitioners' role in strategic auditing. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 11, 39–73. doi: 10.1111/jels.12034

Mautner, M. (2008). Law and culture in Israel at the threshold of the twenty-first century. Israel: Am Oved Publishers.

Mautner, M. (2018). Israel’s 1977 upheaval and the supreme court. Israel Affairs 24, 1033–1049. doi: 10.1080/13537121.2018.1530432

Meydani, A. (2011). The Israeli supreme court and the human rights revolution: courts as agenda setters : Cambridge University Press.

Meydani, A. (2023). Human rights between non-governability and political culture: a new approach in human rights analysis. Israel: Mishpat Ve’Asakim.

Michelman, F. (2018). Israel’s “constitutional revolution”: a thought from political liberalism. Theor. Inq. Law 19, 745–765. doi: 10.1515/til-2018-0034

Montesquieu, B.d.. (1748). Complete works, vol. 1: the spirit of laws. Available at: https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/montesquieu-complete-works-vol-1-the-spirit-of-laws

Nehring, C. (2022). Bulgaria as the sixteenth soviet republic? Todor Zhivkov’s proposals to join the USSR. J. Cold War Stud. 24, 29–45.

Newman, M. (2023). Software firm Riskified to pull $500m from Israel over judicial reforms. Bloomberg. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-09/riskified-to-pull-500-million-from-israel-over-judicial-reforms

Orkibi, E. (2022). ‘It’s a war on Israel’s liberal democracy’: the Israeli left as a moral panic community, 2015-19. Israel Affairs 28, 878–895. doi: 10.1080/13537121.2022.2134360

Peters, G., and Pinfold, R. G. (2018). Understanding Israel: political, societal and security challenges, vol. 1. 1st Edn. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Rahat, G., and Hazan, R. Y. (2005). “Israel: the politics of an extreme electoral system” in The politics of electoral systems. eds. M. Gallagher and P. Mitchell (Oxford University Press), 333–351.

Ram, U. (2024). “Hegemony struggles in Israel: 1920s–2020s” in Routledge handbook on Zionism. ed. C. Shindler (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev: Taylor & Francis), 505–519.

Raval, V. V. (2012). Fight or flight? Competing discourses of individualism and collectivism in runaway boys' interpersonal relationships in India. J. Soc. Pers. Relationsh. 30, 410–429. doi: 10.1177/0265407512458655

Roznai, Y. (2018). “Israel – a crisis of liberal democracy?” in Constitutional democracy in crisis? (forthcoming). eds. M. A. Graber, S. Levinson, and M. Tushnet (Herzliya - Radzyner School of Law: Oxford University Press).

Sapir, G. (2009). Constitutional revolutions: Israel as a case-study. Int. J. Law Context 5, 355–378. doi: 10.1017/S1744552309990218

Shafir, G., and Peled, Y. (2002). Being Israeli: the dynamics of multiple citizenship : Cambridge University Press.

Shamir, R. (1990). Landmark cases and the reproduction of legitimacy: the case of Israel’s high court of justice. Law Soc. Rev. 24, 781–805. doi: 10.2307/3053859

Shamir, Y. (1991). Address by Mr. Yitzhak Shamir. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Available at: https://www.gov.il/en/Departments/General/address-by-mr-yitzhak-shamir-31-october-91

Shamir, M., and Arian, A. (1999). Collective identity and electoral competition in Israel. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 93, 265–277. doi: 10.2307/2585395

Sheleg, Y. (2020). “Jewish” versus “democratic.” The Israel Democracy Institute. Available at: https://en.idi.org.il/articles/31250

Sommer, U. (2009). Crusades against corruption and institutionally-induced strategies in the Israeli supreme court. Israel Affairs 15, 279–295. doi: 10.1080/13537120902983031

Sommer, U. (2010a). Beyond defensive denials: evidence from the Blackmun files of a broader scope of strategic certiorari. Just. Syst. J. 31, 316–341. doi: 10.1080/0098261x.2010.10767973

Sommer, U. (2010b). A strategic court and national security: comparative lessons from the Israeli case. Israeli Stud. Rev. 25, 203–226. doi: 10.3167/isf.2010.250203

Sommer, U. (2011). How rational are justices on the supreme court of the United States? Doctrinal considerations during agenda setting. Ration. Soc. 23, 452–477. doi: 10.1177/1043463111425014

Sommer, U. (2014). A supreme agenda: Strategic case selection on the supreme court of the United States : Palgrave Macmillan.

Sommer, U., and Braverman, R. (2024a). “A proposed constitutional overhaul and the question of judicial independence” in Open judicial politics, vol. 2. 3rd ed.

Sommer, U., and Braverman, R. (2024b). “Comparative methods for measuring judicial ideology and behavior” in Research handbook on judicial politics. eds. M. P. Fix and M. D. Montgomery (Edward and Elgar Publishing).

Suri, J. (2012). Chapter 5: the United States and the cold war: Four ideas that shaped the twentieth-century world. Oxford Academic. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/book/35345/chapter-abstract/300226246?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=true

Talshir, G. (2022). Which ‘Israel before all’? From the Palestinian-Israeli conflict to the Jewish/democratic left-right axis. Israel Affairs 28, 896–916. doi: 10.1080/13537121.2022.2134378

The Core International Human Rights Instruments. (n.d.). Georgetown law library. Available at: https://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=273364&p=6066284#:~:text=They%20include%20a%20treaty%20on,workers%2C%20and%20persons%20with%20disabilities

U.S. Department of State Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs. (2008). Background: Bulgaria. U.S. Department of State. Available at: https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/3236.htm#:~:text=In%201989%2C%20the%20U.S.%20Congress,%24600%20million20in20SEED%20assistance

United Mizrahi Bank Ltd v. Migdal, 49(4) P.D. 221 (1995). CA 6821/93. Knesset. Available at: https://fs.knesset.gov.il//12/Committees/12_ptv_465515.PDF