Abstract

Interest groups, one of the main expressions of the diversity of social interests in the contemporary world, are organizations that serve as channels for bringing social demands to the attention of the political establishment with the aim of influencing the design, discussion, approval, and implementation of public policies. This is achieved through actions directly aimed at public institutions, but also through influence campaigns aimed at public opinion building (i.e., grassroots lobbying). However, little is known about the communication strategies and techniques of interest groups on social media, a crucial field in the current political landscape. This paper focuses on communication as a point of contact between interest groups and institutions, thus filling a research gap. We perform a content analysis of a sample of tweets posted by interest groups from the southern Spanish region of Andalusia, from the perspective of social media interaction, digital political communication, and propaganda. Results indicate that interest groups tend to post one-way messages, that the political and institutional communication techniques employed by these groups reflect a restricted use of digital media, and that the propaganda techniques used aim to construct a favorable public image, but without any connection with explicit political objectives. All of which implies that the communication of these groups is deficient in terms of grassroots lobbying.

1 Introduction

Every society is characterized by the multiple and diverse interests of its members. According to Burdeau (1982), the more complex a society is, the more diverse the interests of its members will be, a situation that has given rise to an increasingly greater number of more specific and, in turn, more contradictory interests. Today's steadily more heterogeneous societies include numerous groups of individuals representing the concerns and aspirations of specific sections (Almond, 1958; Castles, 1973; Basso, 1983). Social demands make their way on to the political agenda not only thanks to the action of political parties, but also—albeit to a lesser degree—to that of other types of organization, viz. interest groups (Castillo-Esparcia and Almansa-Martínez, 2020).

Interest groups (hereinafter IG) are organizations that reflect social pluralism and serve as channels for bringing social demands to the attention of the political establishment and the state, with a view to participating in the design, discussion, approval, and implementation of public policies (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017). Medina Iborra and Bouza García (2020, p. 387) define interest groups as “formally created associations of voluntary membership that defend sectoral demands in the political process, namely, that represent a specific collective or show interest in a particular policy.” Thus, the plurality of social interests is expressed not only through formal channels, like parties, but also through the creation of associations defending specific interests. The difference between both types of organization is that IG, although they participate in the political process and communicate in relation to this, have no interest in achieving political power, in contrast to parties: IG focus on influencing government (Berry and Wilcox, 2018). According to Jordana (2019, p. 368), “Interest groups are understood as all those organizations that, even though part or all of their activities are focused on intervening in the political system, do not pursue political power but strive to obtain or create for their members public resources evidently produced for themselves but by public institutions.”

When studying the way in which such IG defend their interests, it is important to mention two other terms: pressure group and lobby. A pressure group is a smaller unit within an IG devoted to bringing pressure—hence its name—to bear on the political establishment. Broadly speaking, one could say that when an IG approaches government to call for a specific piece of legislation, or to voice its opposition to an existing one, it becomes a pressure group. When addressing the historical evolution of this relationship, Young (1980) claimed that modern lobbies and pressure groups emerged from the demands made by different IG. So, pressure groups appeared when preference was shown for a specific channel—the governmental—for defending group interests (Ferrando-Badía, 1984). For their part, lobbies are professional organizations whose intention is to convince members of the political class to look favorably upon the interests they are defending (Castillo-Esparcia, 2001; Xifra, 2011; Dür et al., 2015). Lobbies can be “agencies, press offices or law firms, professionally devoted to lobbying on behalf of interest or pressure groups that have hired them for that purpose” (Martínez Calvo, 1998, p. 732). Typologically speaking, the actions of lobbies on behalf of IG tend to be aimed directly at public authorities (i.e., direct lobbying; De Figueiredo and Richter, 2014), but also at grassroots mobilization. Communication plays a fundamental role in grassroots lobbying aimed at shaping public opinion. Thus, some lobbyists seek to attract media attention, while others work on matters far from the public eye (Berry and Wilcox, 2018).

Although IG and their lobbying are both typical of the English-speaking world—countries like the United States (Berry and Wilcox, 2018), in particular—these groups are also present in other countries, such as Spain. There has been a revival of civil society when democracy returned to Spain (since the mid-1970s), through the creation and expansion of numerous social organizations defending particular interests (Castillo-Esparcia and Almansa-Martínez, 2020). Citizens have united in all sorts of associations in which they have developed social and political actions for the purpose of defending their interests in both traditional and emerging sectors (Molins and Medina, 2019). An indication that IG are now firmly established in Spain is the fact that their activities are now governed by national and international norms through registers1 which are based on the idea that public decision-making should be as transparent and open as possible. Moreover, citizens have joined forces in different types of associations to take collective action enabling them to participate in the design of new public policies. These associations are social forces “whose actions are directly aimed at the public authorities (i.e., direct lobbying) and/or grassroots mobilisation” (Castillo-Esparcia and Almansa-Martínez, 2020, p. 758).

The study of Spanish interest groups has a certain tradition in the fields of political science and sociology (Giner and Pérez Yruela, 1979, 1988; Molins, 1989, 1994; Molins and Morata, 1993). In this connection, we aim to approach their activities from a different, and much less researched perspective. To this end, the focus is placed on the digital communication behavior of IG in the autonomous community of Andalusia (one of the most important regions of Spain), and specifically on its interactive, political, and propaganda dimensions. As to provide this object of research with a theoretical framework, it is first necessary to perform a literature review on IG communication.

2 Literature review and theoretical framework

2.1 Interest groups and communication

Interest groups essentially implement two types of strategies that are not mutually exclusive, namely, internal and external. Internal strategies aim to have a direct influence on decision-makers: maintaining direct contact with political actors, testifying in Parliament, or participating in political committees and hearings. In contrast, the aim of external strategies is to mobilize or modify public opinion, including tactics such as organizing demonstrations, distributing leaflets, and placing ads in newspapers (Dür and Mateo, 2019). Evidently, when implementing external strategies, communication, and the media are central to the modus operandi of IG.

Communication and public relations (hereinafter PR) have played an important role in the theoretical and methodological evolution of lobbying, placing the accent more on information and transparency than on “pressure” and the subsequent sanctioning of such groups when their demands are rejected (Pineda Cachero, 2002). For example, when defining lobbying, Pasquino (1982, p. 751) underscored the communication factor: “It is a process through which the representatives of interest groups, acting as intermediaries, bring the desires of their groups to the notice of legislators and decision-makers. Therefore, lobbying chiefly involves conveying the messages of pressure groups to decision-makers through specialist representatives.” Other authors have also understood lobbying as a communication activity on behalf of a pressure or interest group (Martínez Calvo, 1998), as a PR communication process (Xifra, 1998), or as part of the global communication of a company (Feo, 2001).

According to Sommerfeldt et al. (2019, p. 9), lobbying “is more of an interpersonal rather than mass or mediated communication activity.” However, this does not prevent the media from being used to influence public opinion. Indeed, one of the most important resources is the aforementioned grassroots lobbying. Communication directed to public opinion has received plenty of attention in North American political science, above all following the advent of the so-called “new lobbying”—which puts the emphasis on public opinion and political education, unlike the “old lobbying” based on actions directly aimed at members of parliament (Castillo-Esparcia, 2003)—as evidenced by the studies performed by Fowler and Shaiko (1987) and Whiteley and Winyard (1987). The underlying logic is that IG aim to create the perception that the public sympathizes with their aspirations and demands or the causes they are defending, thus making it hard for public authorities to adopt decisions that go against groups that are seen in a favorable light by most of the citizenry. Thus, lobbyists use the media to pressure policymakers by influencing public opinion (Vesa, 2022). Berry and Wilcox (2018) point out that many IG engage in outside lobbying, or grassroots lobbying, to influence policymakers, and, although the grassroots approach is a mainstay of citizen groups, corporations and trade associations have also begun to realize its power.

The relationship between lobbying and communication has been approached from different perspectives, ranging from the communication techniques, tactics, and strategies of lobbies and IG (Castillo-Esparcia and Almansa-Martínez, 2011; Vesa, 2022) to their media presence (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017), through elements giving shape to strategies aimed at public opinion building (Castillo-Esparcia, 2003) and the proposal for a descriptive classification of the communication strategies employed in lobbying (Lock and Davidson, 2024). Using agenda-setting theory, Huckins studies correlations between the agendas of the IG Christian Coalition and major U.S. newspapers, and concludes that an interest group “can make a purposeful impact on media coverage” (Huckins, 1999, p. 83). Research has also been conducted on the effectiveness of communication strategies adopted by IG, including the study performed by Vidal Salazar and Delgado Ceballos (2013) on the modification of the environmental behavior of decision-makers. For their part, Berry and Wilcox (2018) have highlighted the relevance of specific facts regarding lobbying's message effectiveness. Moreover, it has been noted that there are three kinds of groups which usually have greater access to the media: first, business groups—which enjoy a high level of access in all countries and systems studied; second, trade unions; and third, certain kinds of citizen groups, especially public IG (Vesa, 2022). From a sectoral point of view, lobbying communication has been studied in the environmental field (Herranz de la Casa et al., 2017), while analyses have also been performed on the communication strategies of pharma companies with the aim of influencing the revision of their drugs for their authorization (Barber and Diestre, 2019), as well as the tools used by interest groups in relation to a law on the consumption of sweet beverages in Colombia (Díaz-García et al., 2020).

Until the advent of new communication technologies, the definition, assignation, and placement of social demands were limited by the level of access to the public authorities and by the control of the media. However, technology has modified that landscape by creating new communication spaces with interaction via networks (Castells' network society) (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017). As noted by Casacuberta and Gutiérrez-Rubí (2010, p. 4), “The introduction of information and communication technologies (or ICTs) in participation processes (e-participation) does not imply creating a new type of participation but simply more participation.” As a result, new channels undermining the existing barriers to social, political, and economic power have been opened (Canel, 1999), signifying that the historical evolution of communication technology has influenced IG activity. For instance, digitally linked collective participation can be beneficial for IG. Haro and Sampedro (2011) found that some (new) associative profiles possessed certain characteristic features, such as viral communication action and digital interactions, among others. In particular, grassroots lobbying has profited from new technology, which has helped lowering the cost of grassroots mobilization (Berry and Wilcox, 2018). On the other hand, online communication is used in parallel to more traditional kinds. As observed by Fuchs (2014), activists' communication is complex, combining offline and online formats, and using digital and non-digital media. In a similar vein, a study based on survey data relating to senior PR practitioners in five countries concluded that lobbying was associated with a greater use of the repertoire of traditional media, as well as digital media like podcasts and blogs (Sommerfeldt et al., 2019). In any case, social networking sites (hereinafter SNS) have already been used to mobilize public opinion in different European countries (Dür and Mateo, 2019). What is more, since the consolidation of SNS the number of actions aimed at exerting pressure and influence on political and social actors in the public space has increased, thus shaping the dynamics of the digital environment (Van Dijck et al., 2018). SNS have also been addressed in research on IG and communication, such as the study performed by Cristancho (2021) on the agenda of these groups on Twitter (now X), revealing that the COVID-19 pandemic had not really modified their modus operandi.

2.2 Interest groups, political communication, and propaganda

The digital realm is also relevant to the political dimension of IG communication. As already seen, the activity of these groups focuses on intervening in the political system (Jordana, 2019). The IG phenomenon is ultimately related to the interests of social and political actors (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017), whereas phenomena like that of the “revolving doors” point to the connection between the corporate world and politics (Ostio et al., 2023). Consequently, it is only natural that IG communication should be considered as a manifestation of the political sort. Even more so when the IG institutional system in Spain has little autonomy regarding government and political parties (Molins and Medina, 2019). If, as observed by Cotarelo (2010), the political arena is now on the Web, the importance of digital communication means that it is essential to enquire more deeply into the way in which organizations are managed and develop in the political public space. Moreover, social media such as Twitter and Facebook have given political actors a new channel by which to influence public opinion directly, permitting them to bypass professional news media (Vesa, 2022). In this respect, the amount of research conducted hitherto in Spain on activism, digital communication, and mobilization should come as no surprise (Anduiza et al., 2009; Castillo-Esparcia and Smolak-Lozano, 2013; Micó and Casero-Ripollés, 2014; Toret, 2013; Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017; Castillo-Esparcia and Almansa-Martínez, 2020). These studies, focusing on the political potential of digital tools, have placed the spotlight on social protest movements.

Thereby we arrive at the first key concept of our theoretical framework: interaction, which stems from the political potential of digital media, and which can be regarded as one key aspect of SNS. This potential should be linked to theories of the political opportunities offered by the Internet, which have traditionally revolved around concepts such as proximity, dialogue, and horizontal relationships—for instance, the idea of the Internet as a development that facilitates participation and engagement (Bekafigo and McBride, 2013; Vergeer et al., 2011) relates to the notion of an egalitarian debate. As stated by Castillo-Esparcia and Almansa-Martínez (2020, p. 759), “Politicians need to listen to their audiences and, therefore, can (and it is advisable that they do) leverage the interactive potential of the Internet, continually inviting the citizenry to participate and replying to their proposals and approaches.” The chance to establish interactive political communication with these audiences is therefore a characteristic of IG online communication.

To this theoretical framework grounded in the connection of IG political communication and digital interaction, should be added a type of communication traditionally linked to politics and ideology, viz. propaganda. The propaganda phenomenon has been the object of countless approaches and definitions over time, as well as of debates on its nature (Pineda Cachero, 2006; Nilsson, 2012). Considering the objectives of this work, the definition offered by Jowett and O'Donnell (1986, p. 16) seems to be appropriate: “Propaganda is the deliberate and systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist.” However, as this definition makes no reference to the content of propaganda, this can be rectified by stating that “the desired intent of the propagandist” always has to do with achieving, maintaining, and reinforcing a position of social power, often underpinned by ideological content (Pineda Cachero, 2008). Power and ideology are thus two concepts that are central to defining propaganda, which, as occurs with interest groups, produces communication based on the interest of the sender. Pertaining to the connection between propaganda and IG, it is no coincidence that Lasswell's (1995) concept of propaganda includes the activities of lobbies and pressure groups, nor that lobbying communication occasionally overlaps with political communication and/or propaganda (Doob, 1966). For instance, the religious-moral Anti-Saloon League, created in 1893 at the peak of the movement in favor of banning the consumption of alcohol in the US, employed organization and propaganda techniques (Young, 1980). In the US, according to Key (1962), and despite the existence of organized lobbies since the nineteenth century, their spectacular growth occurred above all in the wake of the First World War, whose discovery of scientific propaganda had a direct influence on the methods used by pressure groups. IG have historically used propaganda techniques whose fundamental purpose is grassroots lobbying, aimed at public opinion building, and there is no reason to believe that the current situation in the digital world should be different. This assumption relates directly to the research aims of this paper.

3 Research aims and questions

Spanish IG approach institutions through advisory committees with the intention of formally channeling dialogue between the government and organizations representing social interests. The major national trade unions and business confederations are the IG with the greatest presence in these committees. Another way of approaching institutions is through parliamentary hearings to which experts and representatives of groups are invited to share their views on matters debated in parliamentary committees. The third way of gaining access to institutions are IG registers, which in Spain have been seen as a way of disclosing who is interested in influencing the political process (Molins and Medina, 2019). Nevertheless, none of these traditional forms of lobbying take into account the communication factor. Organizations can influence legislative procedures and public policy implementation by gaining a comprehensive knowledge of how institutions work with an eye to gaining access to decision-makers, but can also bring pressure to bear indirectly through the media (De Figueiredo and Richter, 2014). There is a vast amount of literature on the first approach (e.g., Baumgartner et al., 2009; Beyers et al., 2015; Binderkrantz et al., 2015; Muñoz, 2016; Medina and Chaqués-Bonafont, 2024), albeit a lot less on the communication of interest groups (Fowler and Shaiko, 1987; Whiteley and Winyard, 1987; Farnel, 1994; Xifra, 2011; Castillo-Esparcia, 2001).

Accordingly, we intend to fill a research gap in that the communication strategies of interest groups have seldom been studied (Almiron and Xifra, 2016; Castillo Esparcia, 2011), and even less so on SNS. Moreover, the dearth of literature on communication strategies aimed at implementing IG actions is even more evident in the case of those with a regional scope. One study enquires into how the media can act as a pressure group, as illustrated in Andalusia by the Carlist newspaper La Unión and its opposition to the Spanish Second Republic (Langa Nuño and Álvarez Rey, 2010). The region of Andalusia (our object of study) has been approached from the perspective of associations (Del Pino Espejo, 2013), but there is little research on current Andalusian IG communication. Therefore, the intention of this study—performed in the framework of the research project “Lobby y Comunicación en la Unión Europea. Análisis de sus estrategias de comunicación” (Lobbying and communication in the European Union: An analysis of its communication strategies) (ref. PID2020-118584RB-I00)—is to provide empirical evidence that fills the knowledge gap regarding the digital communication of Spanish interest groups and, in particular, Andalusia-based IG.

The primary research objective is to gain deeper insights into the communication of Andalusian interest groups on SNSs. The reason behind selecting an autonomous community like Andalusia is down to the fact that Spain has a more or less decentralized political culture, since the establishment of regional and local governments has territorialised social interests and broadened the opportunities for gaining access to public institutions. This has given rise to a web of interests revolving around Spanish regional politics—regional IG that have even collaborated in the founding of new political parties (Molins and Medina, 2019). As an object of study, Andalusia is also relevant given that it is one of the most important regions of Spain: in 2020, it had 8,464,411 inhabitants, thus accounting for nearly a fifth of the national population of 47,450,795 (INE, 2020). Besides, the use of SNS is fairly widespread, with 64.6% of the Andalusian population being Internet users, slightly above the national average of 63.2% (INE, 2022).

Directly related to IG communication, the second general research objective is to determine which groups have the highest average communication activity and whether they consequently carry out actions of public opinion building (grassroots mobilization) (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017). Grassroots lobbying, as an influence technique, is a long-debated topic in North American political science (Whiteley and Winyard, 1987; Fowler and Shaiko, 1987), although it has not aroused as much academic interest in other regions of the world. Therefore, we aim to fill yet another research gap by gauging the use of grassroots lobbying in Andalusia.

Secondary research objectives include identifying the main Andalusian interest groups appearing in official registers, checking the SNSs they use, and measuring the level of interaction of IG communication with their audiences. From the viewpoint of the content of communication, the objective is to analyse the messages of Andalusian IG, determining their level of interaction (given the dialogic potential of SNS) and their use of political communication and propaganda techniques. As already observed, when running grassroots lobbying campaigns with ideological content, and at the service of power structures, IG are involved in activities indistinguishable from propaganda from a historical angle. It is therefore worthwhile analyzing whether Andalusian IG have intentions of this kind.

These primary and secondary objectives are grounded in the following research questions (hereinafter RQ):

-

RQ1. Which Andalusian interest groups are recorded in official registers?

-

RQ2. To what extent do Andalusian interest groups use SNS?

-

RQ3. Do Andalusian IG establish interactive communication with their audiences on X (formerly Twitter)?

-

RQ4. Do Andalusian IG employ political communication techniques on X?

-

RQ5. Do Andalusian IG employ propaganda strategies and techniques on X with an eye to reaching political objectives?

To these five RQ can be added another general one, the answer to which is based on the data collected from RQ1–RQ5:

-

RQ6. Do Andalusian IG use X for grassroots lobbying?

4 Materials and method

The data collection technique employed to answer the RQ is content analysis (Krippendorff, 2004), a classic methodology for performing communication studies, and particularly useful for identifying patterns in sets of messages. In order to operationalise the first RQ and retrieve data relating to the sampled interest groups, the R programming language (R Core Team, 2021) and the RStudio integrated development environment (RStudio Team, 2021) were used. During the process, web scraping techniques using the Rvest (Wickham et al., 2021) and Rselenium (Pettai, 2021) packages were employed. The combination of these resources allowed to develop a code for downloading the relevant information from two registers: the CNMC (Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia, 2023) and the RTCE (European Commission, n.d.), the latter created by the European Commission and European Parliament in 2011 to unite their IG registers (Dür and Mateo, 2019). Following this, the names of all Andalusian municipalities (Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía, 2023) were crossed with the headquarters of all IG included in the two databases—in both, it is the interest group that establishes its domiciliation, which does not have to coincide with their fiscal address. Two random samples were selected to verify the coincidence between the IG detected and the list of Andalusian IG. Afterwards, the data were cleaned in order to prepare them for analysis. The number of IG based in Andalusia was then filtered by a human researcher, removing from the list of the CNMC especially those individuals and companies that could be regarded as external lobbies or lawyers, and to a lesser extent those groups working in specific socioeconomic areas.

Regarding RQ2, the digital presence of Andalusian IG was assessed by identifying the SNS they used. Social media were chosen as communication outlets because they are a very relevant tool when shaping public opinion in Spain, which is the ultimate aim of grassroots lobbying—according to official sociological data, they are the second most popular channel for keeping abreast of political affairs and election news (CIS, 2019). A search was run on the presence of interest groups on X, Meta, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube. In light of the results, it was decided to focus the content analysis relating to RQ3, RQ4, and RQ5 on X. The main reason behind this was quantitative, since there was a higher number of profiles of Andalusian IG on this SNS. Nevertheless, there were also qualitative reasons for selecting this social site. Firstly, it is the one that has aroused the greatest scholarly interest regarding politics (Ramos-Serrano et al., 2018; Evans et al., 2019), and political communication is one of our research aims. Secondly, X use is fairly widespread in Spain (García Ortega and Zugasti Azagra, 2014), thus making it an appealing SNS for IG aiming to reach public opinion. Additionally—and despite the modifications that X has undergone under the new management of Elon Musk—this platform still has a high presence of information and political content which is ideal for analyzing currents of public opinion (Dubois et al., 2018), in line with grassroots lobbying. Moreover, X has already been approached from the perspective adopted here, the literature containing some or other analysis of IG Twitter communication (Díaz-García et al., 2020; Cristancho, 2021).

RQ3, relating to the interactivity of communication, was operationalized following a study performed by Graham et al. (2013) on political communication, in which they distinguished three types of tweets: normal post, @-reply and retweet—a typology similar to that used by Larsson and Moe (2011). From this typology, the @reply was operationalized as a basic indicator of interaction—in fact, it has already been used as evidence of dialogue and interaction (Criado et al., 2013; Ahmed and Skoric, 2014; Zugasti Azagra and Pérez González, 2015). So, when an IG tweet contained a comment made by some or other user to which the former replied, it was classified as an interactive post. The coding sheet also included a variable specifying that, in the case of interaction, it should indicate the type of user with which this took place: public/citizen, journalist/media, lobbyist, expert, industrialist/industry, authority, celebrity, politician, and activist/non-governmental organization (hereinafter NGO). As a second indicator of interaction, references to users (Capriotti and Zeler, 2020)—aimed at generating some sort of dialogue or contact in the digital sphere—were also operationalized.

RQ4, relating to political communication techniques, was operationalized following Canel's work (Canel, 2006) on the political communication techniques of institutions, establishing the following categories: information aimed at the media, toning down language, neutralizing negative information, leaks, press conferences, press reviews, event organization, speeches, statements, advertising placement, messages of IG spokespeople, messages of press officers/heads of communication/directors of communication, and use of other web formats (other than X). The content analysis identifies the presence of these techniques in the tweets posted by IG on X.

The coding sheet included two variables relating to RQ5, namely, the use of propaganda devices and the identification of political objectives. As to propaganda resources, the following classic categories, proposed by the Institute for Propaganda Analysis (1995), were considered: the name-calling device (when some or other adversary is cast in a negative light, without evidence or implications); the glittering-generalities device (propagandists identify their programmes as something virtuous, ideal); the transfer device (the prestige or authority of an institution is transferred to the object of propaganda); the testimonial device (a well-known person speaks out in favor of the propagandist); the plain-folks device (powerful individuals profess to be down-to-earth people); the card-stacking device (use of deceit); and the band-wagon device (appeals to group unity). Regarding the political goal, it was determined whether IG attacked, defended or took a neutral stance toward Spanish political parties and the country's regional and national governments, or whether they lacked political objectives.

In relation to sample design, and after determining that 47 Andalusian IG had active profiles on X, it was decided that the content analysis should be based on a universe comprising all the tweets posted on X by these groups during 2023. The web scraping Popster tool was used to obtain the tweets of each interest group, before filtering the results to eliminate the comments they had made on X about the tweets of other profiles which did not form part of the posts of their own X walls. The compilation of all the posts resulted in a universe (N) of 14,271 tweets. On the basis of this population, systematic random sampling was used, with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%, indicating an appropriate sample size of 374 units. Following the systematic random procedure (Krippendorff, 2004), a sample interval (k) was calculated by dividing the size of the population (N) by that of the appropriate sample size (n = 374) and by selecting a random start between 1 and k to determine the first unit to be sampled, before continuing with the interval until obtaining all sample units. The systematic sample interval was k = 38, and no. 5 was selected by lot as start interval.

Pertaining to intercoder reliability, following an initial two-coder reliability test based on Krippendorff's alpha (α) and percentage agreement (PA) coefficients, the interaction and political objective variables of the posts reached maximum levels of agreement (α = 1). However, those relating to political communication (α = −0.036) and propaganda techniques (α = −0.063) failed to reach the minimum acceptable threshold in content analysis in terms of Krippendorff's α (α = 0.8), although the political communication technique variable obtained a PA = 86.87%. After a discussion with coders in which the interpretation of problematic variables was fine-tuned, in a second two-coder test the political communication and propaganda variables reached perfect reliability (α = 1). Coding was performed by three authors of this paper using Excel, a software program that has also been utilized in the processing and exploitation of data.

5 Results

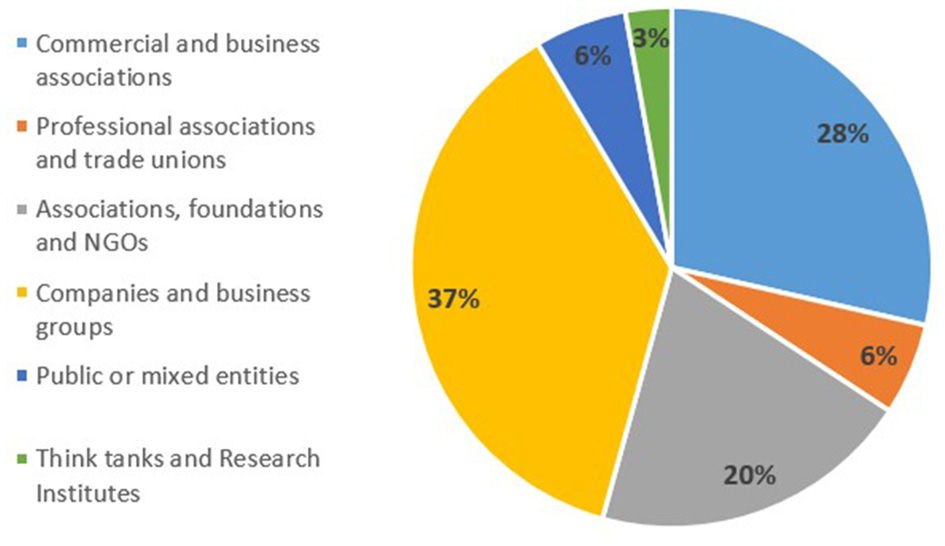

The first results presented below have to do with the type of interest group recorded in the official registers. The list contains a total of 57 registered Andalusian groups (Annex 1), specifically, 35 in the RTCE and 24 in the CNMC—the real total is not 57 because two of them (Fundación Savia por el Compromiso y los Valores, and ENTRA Agregación y Flexibilidad) are registered in both. First and foremost, this indicates that the IG with fiscal domiciles in Andalusia tend to register themselves in the RTCE, rather than in the CNMC. As to the sectors to which these IG belong, Figure 1 shows the types of IG registered in the RTCE.

Figure 1

Categories of IG registered in the RTCE (%).

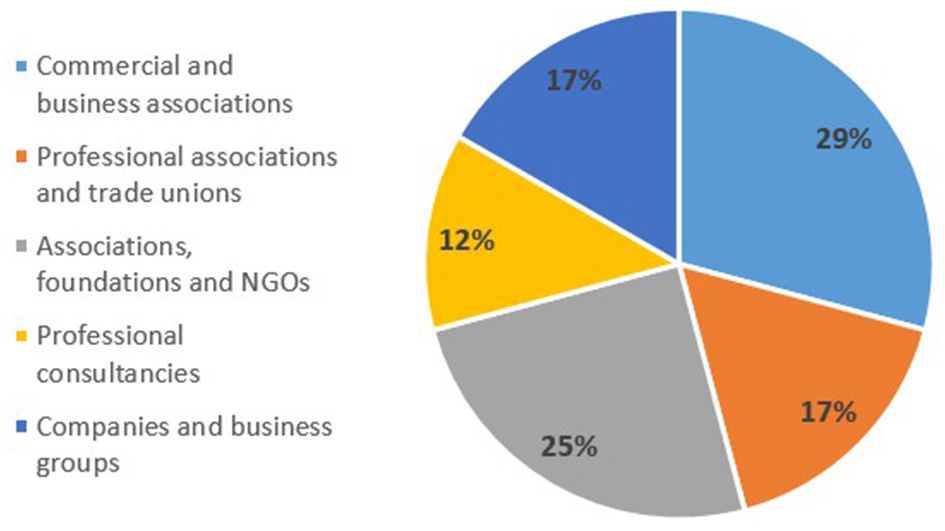

The predominance of companies and business groups, as well as commercial and business associations, among Andalusian IG in the RTCE is plain to see, for both account for 65% of the total. In the CNMC (Figure 2), however, individual companies give way to commercial and business associations, comprising nearly 30% of the total. The presence of companies and business groups is remarkable as well. This Spanish register, moreover, has a greater number of social IG, given the prevalence of the association, foundation, and NGO category (25%).

Figure 2

Categories of IG registered in the CNMC (%).

Concerning the use of SNS, Twitter/X and Meta were the most popular among Andalusian IG, which also put LinkedIn to a fair amount of use (Table 1). Comparatively speaking, the percentages did not vary much between the RTCE and the CNMC, although the interest groups oriented toward Europe attached greater importance to Facebook/Meta and the video-sharing site YouTube than those with a national focus. At any rate, it is important to stress that IG did not put social media to an exhaustive use, for some of them had no presence whatsoever on the two main SNS and, moreover, others simply did not have any SNS profiles at all.

Table 1

| Twitter/X | Facebook/Meta | YouTube | Other SNS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IG registered in the RTCE | 25 (71.4%) | 26 (74.2%) | 12 (34.2%) | 22 (62.8%) | 17 (48.5%) | 4 (11.4%) |

| IG registered in the CNMC | 16 (66%) | 15 (62.5%) | 7 (29%) | 16 (66%) | 9 (37.5%) | – |

SNSs used by Andalusian IG (frequencies and percentages).

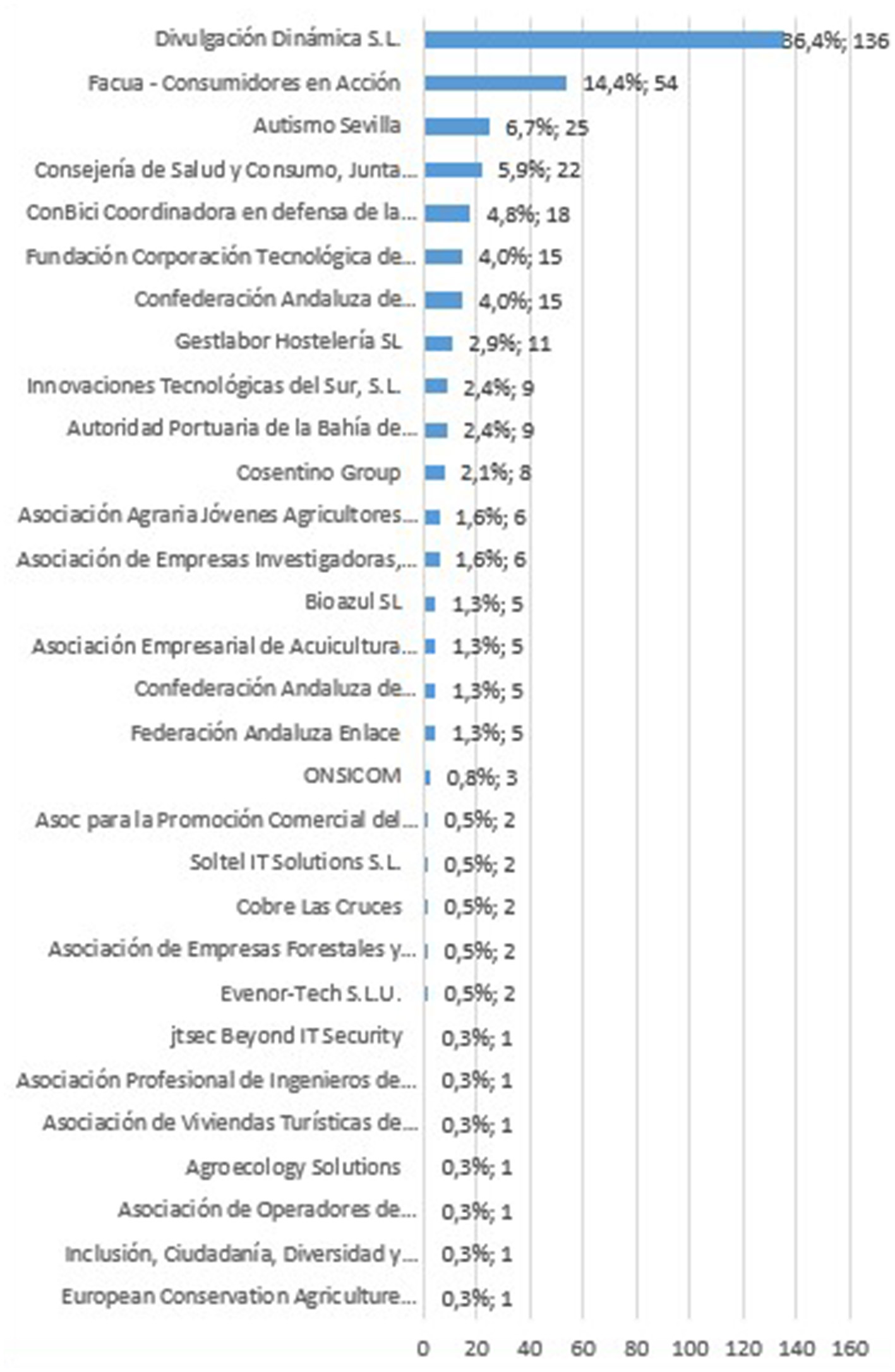

Focusing on Twitter/X, Figure 3 shows that the vast majority of the Andalusian interest groups with profiles on the SNS did not often post tweets, with four of them (Divulgación Dinámica—Dynamic Popularization; FACUA-Consumidores en Acción—FACUA-Consumers in Action; Autismo Sevilla—Autism Seville; and the Consejería de Salud y Consumo de la Junta de Andalucía—Health and Consumer Department of the Andalusian regional government) accounting for more than 60% of the sample. In particular, Divulgación Dinámica, the most active IG on Twitter/X (posting 36.4% of all the tweets), is a social sciences training portal, whereas FACUA (14.4%), in second place, is an NGO devoted to defending consumer rights.

Figure 3

Tweets posted by Andalusian IG on Twitter/X in 2023 (percentages and frequencies).

Moving on to the type of communication Andalusian IG establish with their audiences, the level of interaction detected in the posts (a dichotomous variable) indicates that only 1.6% of posts (namely, six posts) on Twitter/X can be regarded as having established some sort of interactive communication with their audiences, insofar as that nearly 100% of them corresponded to the normal, one-way tweet category—specifically, the number of normal posts amounts to 368, that is, 98.4%. The only user profile with which there was interaction (on the very few occasions on which this occurred) was the general public and the citizenry, without taking into consideration other audiences that have traditionally been very important for IG actions, such as the political class and experts. As to references to users as an indicator of interaction, the results are generally, but not exclusively, more favorable: 21.4% of the posts on Twitter/X contained such references, whereas 78.6% had none whatsoever. That almost 80% of the posts of IG did not mention users yet again highlights their scant interest in interactive communication.

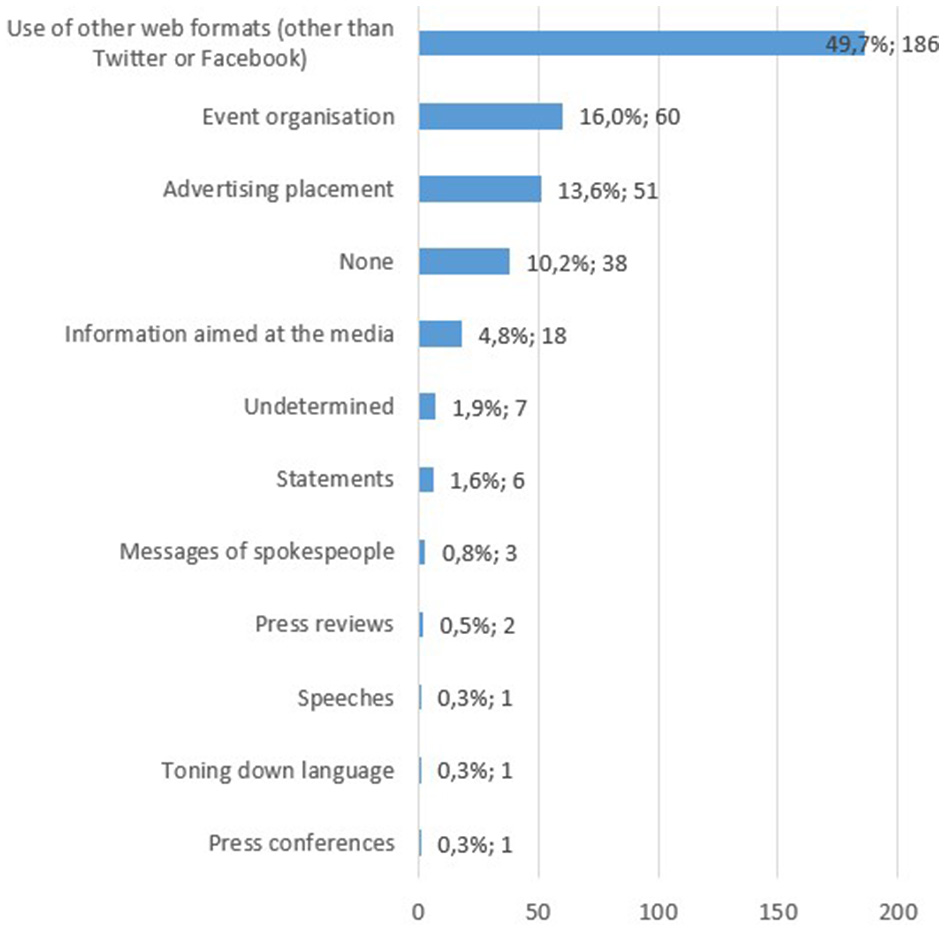

Regarding communication content, the political communication technique most prevalent (in 186 of the 374 posts analyzed, i.e., nearly 50%) was the use of other web formats (Figure 4). This can be exemplified by a tweet posted on 3 January 2023—informing that FACUA had noted that the prices of foodstuffs affected by the lower VAT rate could not be increased in the next 4 months, except in the case of higher production costs—which included a link to the IG's website (facua.org). This technique was followed at considerable distance by event organization (16%) and advertising placement (13.6%). Consequently, the most habitual communication trend was for interest groups to use their profiles to redirect their audiences to content posted on other sites. This underscores yet again the one-way nature of the communication, while relating to the other two techniques detected to a greater extent (event organization and advertising placement), in which that communication was characterized by an asymmetry in favor of IG. In any case, the dearth of techniques relating to message content is striking, as well as the fact that Andalusian organizations did not use any political or institutional communication technique in 10% of the messages. Statistically, and according to Pearson's chi-squared tests (χ2), there is no significant relation between the political communication techniques variable and the interactivity variable (χ2 = 3.60; p = 0.98).

Figure 4

Political communication techniques used by Andalusian IG (percentages and frequencies).

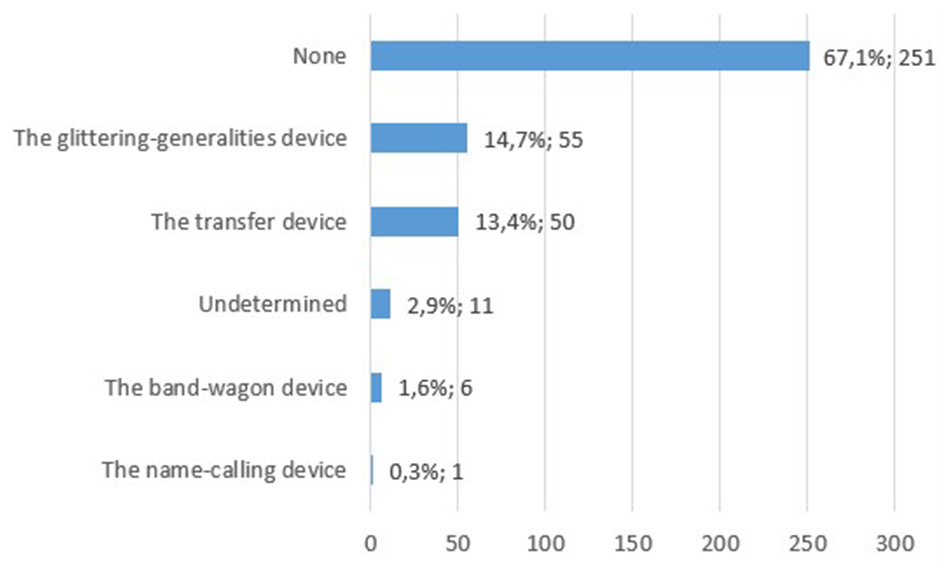

The propaganda techniques adopted by IG (Figure 5) were more related to political content. However, their use did not seem to be decisive, for no propaganda resources were detected in 67.1% of the sample (251 tweets). The only noteworthy techniques were the glittering-generalities (present in 14.7%) and the transfer devices (13.4%). The glittering-generalities device, which identifies the programme of the sender with some or other virtue, is illustrated by a tweet posted by ConBici (Coordinadora Española en Defensa de la Bicicleta), an IG advocating for the use of bicycles, on 17 May, in which it was contended that in Spain “the bicycle industry employs 25,000 people, a number that could increase if this mode of transport is promoted and adequate political measures are taken.” Besides these two techniques, Andalusian IG were not that interested in conveying their messages or communicatively approaching institutions and, consequently, the powers that be. Pearson's chi-squared tests (χ2) indicate significant relations between political communication techniques and propaganda techniques (χ2 = 112.84; p < 0.001). However, and regarding the interactivity variable, no significant relation between this and the propaganda techniques variable was found (χ2 = 3.01; p = 0.7).

Figure 5

Propaganda techniques in IG tweets (percentages and frequencies).

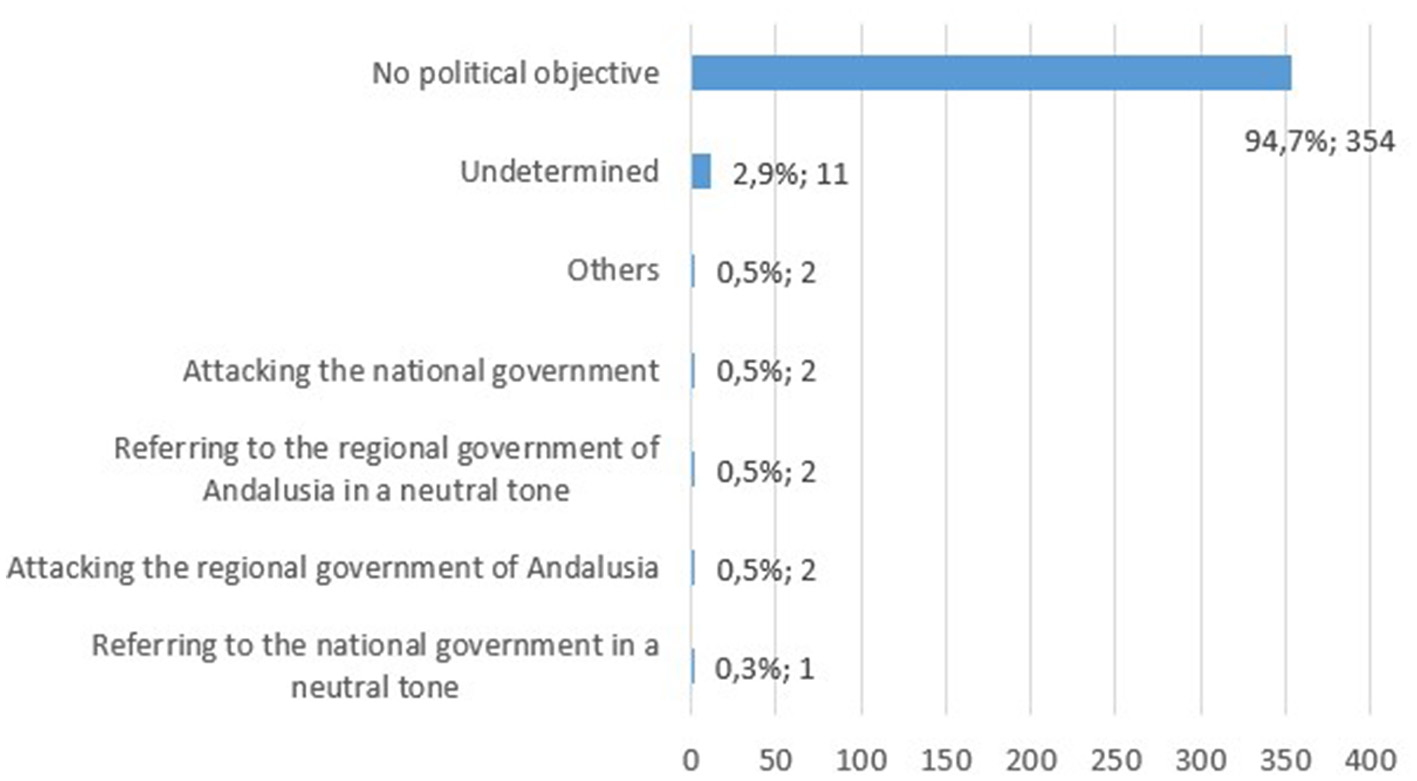

Nor did Andalusian IG appear to be interested in ideological or political stance taking on Twitter/X (Figure 6), for no political objective whatsoever was detected in the content of 94.7% of the posts. Chi-squared tests indicate significant relations between this variable and political communication techniques (χ2 = 167.26; p < 0.001), as well as between the political objective and propaganda techniques variables (χ2 = 121.54; p < 0.001). Although they use some political communication and propaganda techniques, Andalusian IG have no interest in engaging political parties or governments—attacking, defending or taking a neutral stance toward them—in their digital communication. Only 2.9% of the messages analyzed (just 11 tweets) had some type of political goal, but were classified as undetermined owing to the fact that they were very ambiguous. The “attacking the national government,” “referring to the Andalusian regional government in a neutral tone,” and “attacking the Andalusian regional government” categories had an irrelevant presence of 0.5% in each case. An example of this is a tweet posted on 28 August 2023 in which the Federación Andaluza ENLACE (which works with people with addictions and those at risk of social exclusion) seconded another organization condemning the delays in offering people with addictions support.

Figure 6

Political objectives of IG tweets (percentages and frequencies).

6 Discussion and conclusions

This study has analyzed the use of political communication and propaganda by Andalusian interest groups, and cast light on the extent to which they employ communication on social media for grassroots lobbying purposes. The Andalusian interest groups officially registered in the CNMC and the RTCE are mainly companies and commercial and business associations (thus answering RQ1). This implies that the lobbying of these groups is fundamentally commercial and economic, at the expense of ideological demands—and also of political communication, as will be seen below. This business-oriented approach, moreover, is consistent with the evidence suggesting that business interests are represented slightly more than non-business interests in lobbying (De Figueiredo and Richter, 2014), as well as with the information available on the types of IG active in the European Union, including companies, trade unions, business associations, NGOs, and professional associations (Dür and Mateo, 2019). Our study is also in line with the findings of Almansa-Martínez and Castillero-Ostio (2020) indicating that the most representative category in the RTCE includes “the in-house pressure groups of companies and commercial, business, and professional associations.” Furthermore, the fact that there are more interest groups registered in the RTCE than in the CNMC is in keeping with the increase in the number of regional groups present in the European Union (Dür and Mateo, 2019).

Our findings also show that these Andalusian interest groups use SNS in their mediated communication for strategic purposes. Indeed, they use different SNS: Twitter/X, Meta, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube, among others. However, this does not mean that they did so systematically. In relation to RQ2, the use of Twitter/X by IG, in particular, was arguably inconsistent and sloppy. Barring some exceptions, the vast majority or organizations did not post frequent tweets, evincing that digital public opinion building is not among the main objectives of groups which are mainly of a business or commercial nature. As a matter of fact, it is no coincidence that the most active IG on X included consumer association FACUA, association Autismo Sevilla and public institution Health and Consumer Department of the Andalusian regional government, that is, non-profit organizations.

The communication of Andalusian IG was characterized by its lack of interaction: an irrelevant 1.6% of the tweets that these groups posted on Twitter/X can be classified as interactive, leading to dialogue with their audiences. This is reinforced by the fact that references to other Twitter users in their posts were infrequent. Accordingly, the answer to RQ3 is that Andalusian interest groups are not making the most of the opportunities offered by SNS. This ties in with the findings of other studies of the interaction of companies (Zeler, 2021) and Spanish NGOs (Quintana-Pujalte, 2020) on Facebook/Meta, where digital communication tended to be one-way. The same goes for interaction in political communication, which has been widely studied. Research in this respect has shown a very poor use of the interaction potential of sites like Twitter/X by politicians in general (Golbeck et al., 2010; Larsson and Moe, 2011; Mirer and Bode, 2015; Vergeer, 2020) and in Spain in particular (Ramos-Serrano et al., 2018; Pineda et al., 2022). The main theoretical implication here is that a Web 2.0 app like X can be used in a Web 1.0 context, whereby “sites are predominantly hierarchical and disseminating, from the politician and party directly to the citizens” (Vergeer and Hermans, 2013, p. 400)—the same one-way pattern can be detected in IG communication.

This lack of interaction could hinder the positioning of interest groups in the digital sphere and, consequently, in the public sphere. Additionally, “Public opinion can also become a way of gaining more direct access to decision-makers [and] can serve to place an issue on the political agenda, obtaining an elusive meeting, bolstering the legitimacy of proposals or changing the terms of negotiation” (Rubio-Núñez, 2017, p. 409). Bearing this in mind, one could say that with their digital communication, Andalusian IG did not fully exploit the territory in which they disseminated content, thus working against their capacity of influence. Furthermore, their lack of interaction with key institutions implies that they were developing a rather passive strategic digital communication model, far removed from a proactive strategy aimed at placing their interests on the media and political agendas.

The intention of RQ4 was to enquire into whether, given that lobbying is regarded as a form of political communication, Andalusian IG employed political and institutional communication techniques on Twitter/X. Among the techniques identified by Canel (1999), that of other web formats was the most frequently used, which is consistent with interest groups' one-way communication, for on many occasions these took the shape of links to their own websites. This implies that IG adopt the digital media aspects of political and institutional communication, but not the content typical of such communication.

Regarding the strategic use of propaganda techniques (RQ5), Andalusian IG essentially employed them in an attempt to build a positive image of themselves, the most frequently used being the glittering-generalities and transfer devices. Nevertheless, their use of propaganda had no purely political objective whatsoever. In light of the fact that 95% of their tweets lacked political objectives, these organizations apparently had no interest in engaging political parties or governments with their digital communication, whether it be to attack, defend or take a neutral stance toward them. This is especially paradoxical in that two of the most active organizations on Twitter/X included a department of the Andalusian regional government and the consumer association FACUA, whose discourse is not without ideological connotations. At any rate, it can be concluded that Andalusian interest groups did not use Twitter/X as a platform for debate or for putting forward political proposals.

The answers to our five RQs, plus their discussion, lead to RQ6, which asked whether Andalusian IG used Twitter/X for grassroots lobbying. Some results of the content analysis indicate that, in a first reading, it could be suggested that IG had a certain interest in shaping public opinion. This is evidenced by the fact that the sole user profile with which IG interacted was the general public and the citizenry, as well as by the use of propaganda techniques for the purpose of casting the organizations in a positive light. In this connection, Andalusian IG lobbying can be related to Finer's (1966) idea of grassroots campaigning, particularly with the aim of constructing a positive image for the group. Be that as it may, the low frequency of posts on an SNS as oriented toward public debate as Twitter/X, plus the all but complete lack of a strategy for engaging public decision-makers and governments, implies that it is hard to claim that Andalusian IG communication follows the pattern of grassroots lobbying.

It has been observed that an open debate on social media can be considered as a first step toward garnering support, as well as that groups can voice their agreement or disagreement in official political debates (Cristancho, 2021). Practically none of this was detected in the communication of Andalusian IG. It is therefore necessary to reconsider theoretically whether access to media (and social media) content management allows these groups to disclose their demands, in a context where politics has become increasingly a symbolic struggle which all associations want to monopolize in order to impose their worldview (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017). At least in the case of Andalusian interest groups, there does not seem to have been any intention to become embroiled in a symbolic struggle in the political arena to gain influence.

Andalusian IG communication is aimed at constructing a favorable public image. Nonetheless, as it is not clear that such a positive image could help them reach their objectives or satisfy their interests, one could argue that these groups used Twitter/X to achieve objectives differing from those of lobbying per se. Although in theory the tactics and strategies deployed by interest groups, pressure groups and lobbies are not only aimed at gaining direct and particular influence over political representatives—the importance of bringing pressure to bear on public opinion is often recognized in the literature—in the case of Andalusia it seems that this type of indirect influence was conspicuous by its absence. This may help explaining why the connection between political objectives and the public image constructed by lobbying is not explicit. We consider that Andalusian IG present some sort of apolitical façade, with possible political aims remaining in the shade. This hypothesis is in line with the consideration that IG resort more often to internal strategies (i.e., those whose purpose is not to sway public opinion) to influence decisions of the European Union (Dür and Mateo, 2019); as well as with the notions that corporations and trade associations use outside lobbying on occasion (Berry and Wilcox, 2018), and that business groups prefer to use inside lobbying (Vesa, 2022). From a broader theoretical perspective, this also indicates that SNS communication does not have to be obligatory in lobbying, which bears out the fact that a great deal of indirect lobbying does not guarantee greater influence (Álvarez and Arceo, 2023). Nonetheless, a price is paid: since media access may help IG to be recognized by policymakers, and strengthen groups' reputation (Vesa, 2022), this kind of strategising could imply less impact regarding public image and visibility—thus affecting IG public legitimacy.

This paper aimed at shedding light on the digital communication of Andalusian interest groups, an object of study that has received little attention to date. Nevertheless, our study has limitations, one of which is the SNS analyzed: Twitter/X. It would be advisable to determine whether IG communication functions differently from other SNS of a visual or audiovisual nature, such as Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok. Moreover, given that IG strive to place messages and developments of interest to them on the media agenda (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017), another potential line of research would involve contrasting the communication behavior of IG on social media with the news coverage of their messages. Additionally, it is necessary to continue to gain further insights into the communication of interest groups from a regional perspective, and to compare their communication activities at national and transnational levels.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform's terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

AP: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LQ-P: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MR-L: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS-M: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the research project “Lobby y Comunicación en la Unión Europea. Análisis de sus estrategias de comunicación” (Lobbying and communication in the European Union: An analysis of its communication strategies) (ref. PID2020-118584RB-I00).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2025.1534093/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^ Mention should go to the EU Transparency Register (hereinafter RTCE) launched by the European Parliament and the European Commission on 23 June 2011; the Interest Group Register of the Spanish National Markets and Competition Commission (hereinafter CNMC) of the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (MINECO); Executive Order 1/2017, of the 14 February, by virtue of which the Interest Group Register of Catalonia was created and regulated; the agreement of 28 June 2017 of the plenary meeting of Madrid City Council, according to which the basic guidelines for the IG register were established in the Transparency Ordinance of the City of Madrid; Decree 8/2018, of 20 February, providing for the Interest Group Register of Castile-La Mancha; the Transparency and Participation By-Law 10/2019 regulating the interest group register; and the Citizen Participation Law 7/2017 of Andalusia, of 27 December.

References

1

Ahmed S. Skoric M. M. (2014). “My name is Khan: the use of Twitter in the campaign for 2013 Pakistan general election,” in Proceedings of the Forty-Seventh Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, ed. R. H. Sprague, Jr. (Los Alamitos, CA: The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), 2242–2251. 10.1109/HICSS.2014.282

2

Almansa-Martínez A. Castillero-Ostio E. (2020). Lóbis espanhóis no registo europeu de transparência. Comunicação Sociedade2020, 109–126. 10.17231/comsoc.0(2020).2743

3

Almiron N. Xifra J. (2016). Influence and advocacy: revisiting hot topics under pressure. Am. Behav. Scientist60, 253–255. 10.1177/0002764215615161

4

Almond G. A. (1958). A comparative study of interest groups and the political process. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 52, 270–282. 10.2307/1953045

5

Álvarez S. Arceo A. (2023). El lobbying de las Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil en España: capacidad de influencia sobre las instituciones públicas. Estudios sobre mensaje periodístico29, 521–532. 10.5209/esmp.88987

6

Anduiza E. Cantijoch M. Gallego A. (2009). Political participation and the internet. Inf. Commun. Soc. 12, 860–878. 10.1080/13691180802282720

7

Barber I. V. B. Diestre L. (2019). Pushing for speed or scope? Pharmaceutical lobbying and Food and Drug Administration drug review. Strategic Manage. J. 40, 1194–1218. 10.1002/smj.3021

8

Basso L. (1983). Socialismo y revolución.México: Siglo XXI.

9

Baumgartner F. R. Berry J. Hojnacki M. Leech B. Kimball D. (2009). Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why.Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 10.7208/chicago/9780226039466.001.0001

10

Bekafigo M. A. McBride A. (2013). Who tweets about politics? Political participation of Twitter users during the 2011 gubernatorial elections. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 31, 625–643. 10.1177/0894439313490405

11

Berry J. M. Wilcox C. (2018). The Interest Group Society. New York, NY: Routledge. 10.4324/9781315534091

12

Beyers J. Bruycker I. Baller I. (2015). The alignment of parties and interest groups in EU legislative politics. A tale of two different worlds?J. Euro. Public Policy22, 534–551. 10.1080/13501763.2015.1008551

13

Binderkrantz A. Christiansen P. Pedersen H. (2015). Interest group access. Governance28, 95–112. 10.1111/gove.12089

14

Burdeau G. (1982). Traité de Science Politique, Tom III (La Dynamique Politique), Vol. I: Les Forces Politiques. Paris: Librairie Génerale de Droit et Jurisprudence.

15

Canel M. J. (1999). Comunicación política: técnicas y estrategias para la sociedad de la información. Madrid: Tecnos.

16

Canel M. J. (2006). Comunicación política. Una guía para su estudio y práctica. Madrid: Tecnos.

17

Capriotti P. Zeler I. (2020). Comparing Facebook as an interactive communication tool for companies in LatAm and worldwide. Commun. Soc.33, 119–136. 10.15581/003.33.3.119-136

18

Casacuberta D. Gutiérrez-Rubí A. (2010). E-PARTICIPACIÓN: De cómo las nuevas tecnologías están transformando la participación ciudadana, 73. Razón & Palabra. Available online at: http://www.razonypalabra.org.mx/N/N73/MonotematicoN73/12-M73Casacuberta-Gutierrez.pdf

19

Castillo Esparcia A. (2011). Lobby y comunicación. Manganeses de la Lampreana: Comunicación Social Ediciones y Publicaciones.

20

Castillo-Esparcia A. (2001). Los grupos de presión ante la sociedad de la comunicación.Málaga: Ed. Universidad de Málaga.

21

Castillo-Esparcia A. (2003). Las relaciones públicas en el ámbito político. El lobbying como estrategia de comunicación. Laurea Hispalis Revista Internacional Investigación Relaciones Públicas Ceremonial Protocolo2, 63–103.

22

Castillo-Esparcia A. Almansa-Martínez A. (2011). Interacciones comunicativas entre lobbies, sistema político y medios de comunicación. Temas Comunicación23, 67–87. 10.62876/tc.v0i23.675

23

Castillo-Esparcia A. Almansa-Martínez A. (2020). “Redes sociales y organizaciones no gubernamentales. Análisis de las principales ONG de España y sus acciones de lobby,” in X Encuentro internacional de investigadores y estudiosos de la información y la comunicación (ICOM 2019): memorias (La Habana: La Habana Editorial Universitaria), 756–779.

24

Castillo-Esparcia A. Smolak-Lozano E. (2013). “Evaluación y herramientas de análisis de las redes sociales,” in Comunicación 2.0 y 3.0, ed. J. Durán Medina (Madrid: Visión libros), 375–394.

25

Castillo-Esparcia A. Smolak-Lozano E. Fernández-Souto A. (2017). Lobby y comunicación en España. Análisis de su presencia en los diarios de referencia. Revista Latina Comunicación Soc.72, 789–802. 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1192

26

Castles F. G. (1973). The political functions of organized groups. Polit. Stud.21, 26–34. 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1973.tb01415.x

27

CIS (2019). Estudio n° 3242. Macrobarómetro de Marzo 2019. Preelectoral Elecciones Generales 2019. Available online at: http://datos.cis.es/pdf/Es3242mar_A.pdf (accessed December 2, 2019).

28

Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia (2023). Buscador de Listado de grupos de interés. Available online at: https://rgi.cnmc.es/buscador?text=&page=578 (accessed October 8, 2024).

29

Cotarelo R. (2010). La política en la era de internet. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch.

30

Criado J. I. Martínez-Fuentes G. Silván A. (2013). Twitter en campaña: las elecciones municipales españolas de 2011. RIPS12, 93–113.

31

Cristancho C. (2021). La agenda de los grupos de interés frente a la COVID-19: el rastro digital en Twitter. Revista Española Ciencia Política57, 45–75. 10.21308/recp.57.02

32

De Figueiredo J. M. Richter B. K. (2014). Advancing the empirical research on lobbying. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 17, 163–185. 10.1146/annurev-polisci-100711-135308

33

Del Pino Espejo M. J. (2013). “Participación ciudadana y género en Andalucía,” in Instrumentos y procesos de participación ciudadana en España y Marruecos, dirs. Ali El Hanaoudi and J. M. Porro Gutiérrez (Madrid: Dykinson), 79–88.

34

Díaz-García J. Valencia-Agudelo G. Carmona-Garcés I. C. González-Zapata L. I. (2020). Grupos de interés e impuesto al consumo de bebidas azucaradas en Colombia. Lecturas Economía93, 155–187. 10.17533/udea.le.n93a338783

35

Doob L. W. (1966). Public Opinion and Propaganda. Hamden, CT: Archon Books.

36

Dubois E. Gruzd A. Jacobson J. (2018). Journalists' use of social media to infer public opinion: the citizens' perspective. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 36, 456–468. 10.1177/0894439318791527

37

Dür A. Bernhagen P. Marshall D. (2015). Interest group success in the European Union: when (and why) does business lose?Compar. Polit. Stud. 48, 951–983. 10.1177/0010414014565890

38

Dür A. Mateo G. (2019). “Los grupos de interés en la UE,” in Política de la Unión Europea. Crisis y continuidad, eds. C. Ares and L. Bouza (Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas), 131–146. 10.2307/j.ctvr33cq8.8

39

European Commission (n.d.) . Transparency Register. Available online at: https://commission.europa.eu/about-european-commission/service-standards-and-principles/transparency/transparency-register_en (accessed October 8, 2024).

40

Evans H. K. Habib J. Litzen D. San Jose B. Ziegenbein A. (2019). Awkward independents: what are third-party candidates doing on Twitter?Polit. Sci. Polit. 52, 1–6. 10.1017/S1049096518001087

41

Farnel F. J. (1994). Le lobbying. Strategies et techniques d'intervention.Paris: Les Éditions d'Organisation.

42

Feo J. (2001). “La legitimidad del lobby,” in Relaciones Públicas y Protocolo, ed. M. T. Otero Alvarado (Sevilla: EIRP CP), 79–89.

43

Ferrando-Badía J. (1984). “Grupos de interés,” in Diccionario del sistema político español, ed. dir. J. J. González Encinar (Madrid: Akal), 401–405.

44

Finer S. E. (1966). El imperio anónimo. Madrid: Tecnos.

45

Fowler L. L. Shaiko R. G. (1987). The grass roots connection: environmental activists and senate roll calls. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 31, 484–510. 10.2307/2111280

46

Fuchs C. (2014). Social Media: A Critical Introduction. London: Sage.

47

García Ortega C. Zugasti Azagra R. (2014). La campaña virtual en Twitter: análisis de las cuentas de Rajoy y de Rubalcaba en las elecciones generales de 2011. Historia Comunicación Soc.19, 299–311. 10.5209/rev_HICS.2014.v19.45029

48

Giner S. Pérez Yruela M. (1979). La sociedad corporativa. Madrid: CIS.

49

Giner S. Pérez Yruela M. (1988). El corporativismo en España. Ariel: Barcelona.

50

Golbeck J. Grimes J. M. Rogers A. (2010). Twitter use by the U.S. Congress. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 61, 1612–1621. 10.1002/asi.21344

51

Graham T. Broersma M. Hazelhoff K. Van't Haar G. (2013). Between broadcasting political messages and interacting with voters. The use of Twitter during the 2010 UK general election campaign. Inf. Commun. Soc. 16, 692–716. 10.1080/1369118X.2013.785581

52

Haro C. Sampedro V. (2011). Activismo político en Red: del Movimiento por la Vivienda Digna al 15M. Revista Teknokultura8, 157–175.

53

Herranz de la Casa J. M. Sidorenko Buatista P. Canteri de Julián J. (2017). “Rutinas comunicativas y lobbies en el sector medioambiental,” in El debate energético en los medios, ed. M. T. Mercado-Sáez (Barcelona: UOC), 127–138.

54

Huckins K. (1999). Interest-group influence on the media agenda: a case study. J. Mass Commun. Q. 76, 76–86. 10.1177/107769909907600106

55

INE (2020). Cifras oficiales de población resultante de la revisión del Padrón municipal. Available Online at: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177011&menu=resultados&idp=1254734710990 (accessed October 8, 2024).

56

INE (2022). Encuesta sobre equipamiento y uso de tecnologías de información y comunicación en los hogares 2022. Available Online at: https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/index.htm?padre=8921&capsel=8923 (accessed October 8, 2024).

57

Institute for Propaganda Analysis (1995). “How to detect propaganda,” in Propaganda, ed. R. Jackall (Basingstoke: Palgrave), 217–224. 10.1007/978-1-349-23769-2_11

58

Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía (2023). Base de datos de Municipios de Andalucía. Available online at: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia/badea/informe/anual?CodOper=b3_151&idNode=23204 (accessed November 13, 2024).

59

Jordana J. (2019). “Grupos de interés y acción colectiva,” in Manual de ciencia política, eds. M. Caminal Badia and J. Torrens (Madrid: Tecnos), 355–384.

60

Jowett G. S. O'Donnell V. (1986). Propaganda and Persuasion. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

61

Key V. O . (1962): Política, partidos y grupos de presión. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios Políticos.

62

Krippendorff K. (2004). Content Analysis. Los Ángeles, CA: Sage.

63

Langa Nuño C. Álvarez Rey L. (2010). “La prensa carlista en Andalucía. Un grupo de presión contra la Segunda República,” in Política y comunicación en la historia contemporánea, coords. E. Bordería Ortiz, F. Martínez Gallego, and I. Rius Sanchis (Madrid: Editorial Fragua), 274–293.

64

Larsson A. O. Moe H. (2011). Studying political microblogging: Twitter users in the 2010 Swedish election campaign. New Media Soc. 14, 729–747. 10.1177/1461444811422894

65

Lasswell H. D. (1995). “Propaganda,” in Propaganda, ed. R. Jackall (Basingstoke: Palgrave), 13–25. 10.1007/978-1-349-23769-2_2

66

Lock I. Davidson S. (2024). Argumentation strategies in lobbying: toward a typology. J. Commun. Manage. 28, 345–364. 10.1108/JCOM-09-2022-0111

67

Martínez Calvo J. (1998). “Lobbying. Relaciones públicas políticas,” in Manual de Relaciones Públicas Empresariales e Institucionales, coord. J. D. Barquero (Barcelona: Gestión 2000), 731–747.

68

Medina Iborra I. Bouza García L. (2020). “Grupos de interés y administraciones públicas: estrategias, mitos y debates actuales,” in Democracia, gobierno y administración pública contemporánea, dirs. B. Aldeguer Cerdá and G. Pastor Albadalejo (Madrid: Tecnos), 387–401.

69

Medina I. Chaqués-Bonafont L. (2024). Acceso de los grupos de interés a la arena gubernamental: un estudio comparativo de los gobiernos de Mariano Rajoy y Pedro Sánchez (2012-2021). Revista Española Investigaciones Sociológicas186, 123–142. 10.5477/cis/reis.186.123-142

70

Micó J.-L. Casero-Ripollés A. (2014). Political activism online: organization and media relations in the case of 15M in Spain. Commun. Soc. 17, 858–871. 10.1080/1369118X.2013.830634

71

Mirer M. L. Bode L. (2015). Tweeting in defeat: how candidates concede and claim victory in 140 characters. New Media Soc. 17, 453–469. 10.1177/1461444813505364

72

Molins J. (1989). Chambers of Commerce as Interest Groups. Barcelona: Institut de Ciències Polítiques i Socials.

73

Molins J. (1994). Los grupos de interés en España. Madrid: Fundación para el Análisis y los Estudios Sociales.

74

Molins J. Morata F. (1993). “Spain: rapid arrival of a latecomer,” in National public and Private EC Lobbying, ed. M. P. C. M. Van Schendelen (Aldershot: Dartmouth Publishing Company), 111–127.

75

Molins J. M. Medina I. (2019). “Los grupos de interés,” in Gobierno y política en España, eds. J. Montabes and A. Martínez (Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch), 615–645.

76

Muñoz L. (2016). “Las ONG en la política de cooperación al desarrollo,” in Los grupos de interés en España: la influencia de los lobbies en la política española, eds. J. M. Molins, L. Muñoz, and I. Medina (Madrid: Tecnos), 450–473.

77

Nilsson M. (2012). American propaganda, Swedish labor, and the Swedish Press in the Cold War: The United States Information Agency (USIA) and co-production of U.S. Hegemony in Sweden during the 1950s and 1960s. Int. Hist. Rev. 34, 315–345. 10.1080/07075332.2011.626579

78

Ostio E. C. Cabanillas A. M. Esparcia A. C. (2023). Transparencia y Gobierno: puertas giratorias en España. Revista española transparencia18, 201–229. 10.51915/ret.295

79

Pasquino G. (1982). “Grupos de presión,” in Diccionario de política, dirs. N. Bobbio and N. Matteucci (Madrid: Siglo XXI), 749–761.

80

Pettai T. (2021). Rselenium: R Bindings for ‘Selenium WebDriver' [R package]. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RSelenium (accessed October 8, 2024).

81

Pineda Cachero A. (2002). Lobbies y grupos de presión: de la política a la comunicación. Una fundamentación teórica. Laurea Hispalis Revista Internacional Investigación Relaciones Públicas Protocolo1, 87–122.

82

Pineda Cachero A. (2006). Elementos para una teoría comunicacional de la propaganda. Sevilla: Alfar.

83

Pineda Cachero A. (2008). Un modelo de análisis semiótico del mensaje propagandístico. Comunicación Revista Internacional Comunicación Audiovisual Publicidad Estudios Culturales1, 32–45.

84

Pineda A. Fernández Gómez J. D. Rebollo-Bueno S. (2022). Mobilizing third options in Spain: the political communication of minor parties on Twitter. Revista Internacional Relaciones Públicas12, 177–200. 10.5783/revrrpp.v12i24.779

85

Quintana-Pujalte L. (2020). Comunicación digital y ONG: disputa entre la cultura organizacional, el discurso transformador y el fundraising. Prisma Soc.29, 58–79.

86

R Core Team (2021). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Software]. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed October 8, 2024).

87

Ramos-Serrano M. Fernández Gómez J. D. Pineda A. (2018). ‘Follow the closing of the campaign on streaming': the use of Twitter by Spanish political parties during the 2014 European elections. New Media Soc. 20, 122–140. 10.1177/1461444816660730

88

RStudio Team (2021). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R [Software]. Available online at: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed February 26, 2025).

89

Rubio-Núñez R. (2017). La actividad de los grupos de presión ante el poder ejecutivo: una respuesta jurídica más allá del registro. Teoría Realidad Constitucional40, 399–430. 10.5944/trc.40.2017.20920

90

Sommerfeldt E. Yang A. Taylor M. (2019). Public relations channel “repertoires”: exploring patterns of channel use in practice. Public Relat. Rev. 45, 1–13. 10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.101796

91

Toret J. (2013). Tecnopolítica. Barcelona: UOC.

92

Van Dijck J. Poell T. De Waal M. (2018). Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oso/9780190889760.001.0001

93

Vergeer M. (2020). “Political candidates' discussions on Twitter during election season: a network approach,” in Twitter, the Public Sphere, and the Chaos of Online Deliberation, eds. G. Bouvier and J. Rosenbaum (Londres: Palgrave Macmillan), 53–78. 10.1007/978-3-030-41421-4_3

94

Vergeer M. Hermans L. (2013). Campaigning on Twitter: microblogging and online social networking as campaign tools in the 2010 general elections in the Netherlands. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 18, 399–419. 10.1111/jcc4.12023

95

Vergeer M. Hermans L. Sams S. (2011). Online social networks and micro-blogging in political campaigning: the exploration of a new campaign tool and a new campaign style. Party Polit. 19, 477–501. 10.1177/1354068811407580

96

Vesa J. (2022). “Interest groups and the news media,” in The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Interest Groups, Lobbying and Public Affairs, eds. P. Harris, A. Bitonti, C. S. Fleisher, and A. S. Binderkrantz (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 716–723. 10.1007/978-3-030-44556-0_46

97

Vidal Salazar M. D. Delgado Ceballos J. (2013). La influencia de los stakeholders en el comportamiento medioambiental de los directivos: el uso de estrategias indirectas. Cuadernos Económicos ICE86, 153–169. 10.32796/cice.2013.86.6067

98

Whiteley P. F. Winyard S. (1987). Pressure for the Poor. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

99

Wickham H. François R. Henry L. Müller K. (2021). Rvest: Easily Harvest (Scrape) Web Pages [R package]. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rvest (accessed October 8, 2024).

100

Xifra J. (1998). Lobbying. Barcelona: Gestión 2000.

101

Xifra J. (2011). Lobbismo y grupos de influencia.Barcelona: UOC.

102

Young K. (1980). La opinión pública y la propaganda. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

103

Zeler I. (2021). Comunicación interactiva de las empresas chilenas en Facebook: un estudio comparativo con las empresas latinoamericanas. OBRA Digital20, 15–28. 10.25029/od.2021.281.20

104

Zugasti Azagra R. Pérez González J. (2015). La interacción política en Twitter: el caso de @ppopular y @ahorapodemos durante la campaña para las Elecciones Europeas de 2014. Ámbitos28, 1–14. 10.12795/Ambitos.2015.i28.07

Summary

Keywords

Andalusian interest groups, political communication, propaganda, grassroots lobbying, social media and political communication

Citation

Pineda A, Quintana-Pujalte L, Rodríguez-López M and Sánchez-Martín M (2025) The social media communication of Andalusian interest groups: interaction, politics, and propaganda. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1534093. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1534093

Received

25 November 2024

Accepted

17 February 2025

Published

12 March 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Rubén Rivas-de-Roca, University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Reviewed by

Sergiu Miscoiu, Babeş-Bolyai University, Romania

Sara Rebollo-Bueno, Loyola Andalusia University, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Pineda, Quintana-Pujalte, Rodríguez-López and Sánchez-Martín.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Antonio Pineda apc@us.es

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.