94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 29 January 2025

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2025.1533270

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Crises of the Israeli DemocracyView all 5 articles

Maoz Rosenthal1*

Maoz Rosenthal1* Assaf Meydani2

Assaf Meydani2This study examines the supposed “activism” of Israel’s High Court of Justice amid recent political crises and legislative efforts to curb its powers. While judicial behavior often balances political activism and constitutional problem-solving, this paper analyzes the Court’s agenda structure to assess its approach. The research hypothesizes that an activist court would maintain an agenda focused on a few core topics over time. In contrast, a court that takes a legal, constitutional approach would have an agenda with a broad array of topics and policy punctuations. Analyzing the Court’s rulings from 1995 to 2018, this study reveals an agenda structure mostly aligning with the latter expectation. By examining the dynamics of policy attention, this paper contributes to our understanding of judicial review strategies beyond traditional preference and incentive-based models. The findings suggest that Israel’s High Court of Justice usually operates more as a legal problem solver than an activist institution, offering new insights into its role in Israeli politics and policymaking.

A key pillar in the 2018–2023 political crisis in Israel was the issue of the judicial system and its perceived “activism” (Roznai and Cohen, 2023; Sommer and Braverman, 2024). Judicial activism comes into being in various forms and ways (Lindqquist and Cross, 2009). Is Israel’s High Court of Justice an activist court? To answer this question, we examined what Lindquist and Cross referred to as the hallmark of judicial activism--the judicial review of the executive branch’s decisions (Lindqquist and Cross, 2009: Ch.6). This aspect of judicial activism is crucial to the judicialization of politics and the creation of a juristocracy, of which Israel’s High Court of Justice is a well-known example (Hirschl, 2008).

Hence, this paper empirically examines the extent to which Israel’s High Court of Justice has engaged in judicial activism in its behavior by investigating the public policy aspects of its agenda. Indeed, a key characteristic of countries that have undergone the process of democratization has been the expansion of judicial review (Ginsburg, 2008; Shapiro and Sweet, 1999; Tate, 1995), which paved the way to institutionalizing far-reaching constitutional changes (Jacobsohn and Roznai, 2020). Furthermore, in places in which democratic backsliding and erosion occur, the courts’ constitutional and administrative review powers become a clear target for policymakers seeking to curb liberal democratic ideals (Huq and Ginsburg, 2017).

The literature concerning judicial independence and the consequent potential judicialization of politics has identified the social and institutional conditions needed to facilitate the judiciary’s involvement in politics (Couso et al., 2010; Hirschl, 2008; Sheehan et al., 2012; Sweet, 1999). This paper expands on these efforts and examines an additional aspect of judicialization, namely, the structure of the Court’s policy agenda, which indicates the dynamics of its policy attention. Specifically, we analyze Israel’s High Court of Justice (HCJ), a court whose approach entails judicial dominance over the executive (Hirschl, 1998) but a reserved and selective involvement in government decisions (Rosenthal et al., 2021).

For judicial politics literature examining judicial behavior, the judicialization of politics coincides with the attitudinal and strategic approaches of the courts. The first approach regards judges as decision-makers who manifest their preferences through their judicial rulings. The strategic approach assumes that judges are purposeful and strategic decision-makers who use their power to advance policy preferences through their control of the agenda and veto powers (Epstein and Knight, 1997). In this approach, judges decide which cases to review, thereby determining how other institutions should follow the Court’s orders (Epstein and Shvetsova, 2002; Stearns, 2002).

However, other analyses, which accord with the attitudinal model, point to the potential effect of environmental and cognitive factors affecting the judges’ ability to further their preferences (Epstein and Knight, 2013). Judges’ preferences affect their rulings. However, the complexity of the issues on which they rule and the constraints under which they function when making decisions result in a situation where their final decisions are derived from their policymaking environment rather than their policy preferences (Braman, 2006, 2009). Events, institutions, and cognitive bounds dictate how judges relate to the policymaking process, affecting their agendas and shaping the attention they pay to various policies (Rebessi and Zucchini, 2017). Hence, the Court’s agenda structure reflects the dynamics of the judges’ policy attention. The agenda structure encompasses two phenomena: the consistency of the agenda over time with regard to the topics it includes and the diversity of these topics.

The structure of the agenda and how it varies and diversifies reflects two types of politically based decision-making processes. The first is the party model, which focuses on the topics that politicians need to promote to survive politically. The agenda of the party model remains consistent over time and focuses on the limited number of issues of concern to the politicians. Indeed, in such a model it is purposeful political players who handle the agenda, making sure that the topics on the agenda are those that concern these players (True et al., 2019). If we assume that judges are purposeful and strategic, we would expect to see a judicial agenda that is not diverse and includes the same set of topics of concern to politicians. Not only is the agenda static, but it also focuses on topics that allow partisan and ideologically biased actors to dominate the agenda.

The second model is the external events model. In this model, decision-makers are affected by external pressures and exogenous events that disrupt the policy agenda. Therefore, the structure of the agenda is much more varied and contains a much broader set of topics (True et al., 2019). In the external events model, the judges do not control the policy agenda or use it for their own benefit. Instead, they rule on the various topics that arise. Thus, they function as legal problem solvers who tackle policy issues utilizing a variety of factors: legal, attitudinal, behavioral, and cognitive (Braman, 2006, 2009; Epstein and Knight, 2013).

This paper uses a novel approach to the study of the judicialization of politics by examining the patterns of the policy attention of the agenda of Israel’s High Court of Justice empirically over time. The results should reveal whether the Court is an activist court that focuses on a few issues with political goals in mind or one that engages in a broad range of judicial review. We begin by presenting different models of judicial behavior and offer some empirical expectations regarding their reflection in actual judicial decision-making. We then present the case study, the data, and the research design. Finally, we offer some analyses of the HCJ’s agendas to determine which of our hypothesized models fits best with our findings. In the discussion we connect our findings to the way Israel’s politicians have been engaging with the court, during the prolonged political crisis Israel has been facing.

The judicialization of politics is the tendency to lean on the courts to handle policy and political questions (Hirschl, 2009a). It stems from several factors: the institutional veto powers granted to the courts (Whittington, 2001), a set of civil-society policy entrepreneurs seeking to advocate for civil rights through court action (Couso et al., 2010), and the willingness of the courts to engage in core political issues that are very controversial in the political system (Hirschl, 2008, 2009a; Sheehan et al., 2012). The judicialization of politics hypothesis coincides with the attitudinal and strategic approaches to the study of judicial politics: judges are purposeful players seeking to implement their policy preferences within the political process. The attitudinal premise is a clear set of preferences regarding policy issues (Segal, 2010). The strategic premise for judicializing the court’s behavior is courts and judges seeking to exert their influence when they can (Epstein and Knight, 1997). In both approaches, when judges intervene in topics deemed core political issues, these topics are political in the partisan sense of the word, even if they are presented in the guise of judicial doctrines (Hirschl, 2008).

Analytically, for such a process to happen, the Court should cherry-pick the cases it reviews, allowing petitions through which it can promote its agenda to be heard (Epstein and Shvetsova, 2002). Moreover, the cherry-picking should be evident when the judges engage with advocates of the policy agendas that the Court favors. Such advocates would seek to promote particular cases they can use to advance their agendas and work with judges who share their preferences and are likely to rule in their favor (Dotan and Hofnung, 2001; Stearns, 2002). Assuming that judges are policymakers within a political institution, how they decide on cases relates to the cases that make their way to their agenda, meaning, which cases do and do not receive certiorari and can make their claims before the judges. Furthermore, judges should be able to continuously review a fixed stream of cases, ensuring that they continuously review the topics they wish to influence. To understand these dynamics, we lean on concepts and theoretical statements stemming from agenda dynamics literature. This literature usually examines formal elected political institutions rather than appointed judges. However, the insights it offers concerning agency and structure within institutions allow us to explore their relevance to judicial politics.

According to agenda-setting literature, a key element in any attempt to affect policy processes is how an issue becomes part of the decision-makers’ agendas (Riker, 1986). The topics that policymakers should deal with stem from numerous social processes that create novel social problems (Baumgartner et al., 2009). When a topic becomes part of the policymakers’ agendas, it signals that it has received policy attention (Green-Pedersen and Walgrave, 2014). As a result, it might receive policy substance, meaning public policy decisions that reallocate resources to handle the policy problem (Dowding et al., 2016).

When a topic becomes part of the policymakers’ agenda, it can do so as the result of the purposeful act of decision-makers who use their access to the agenda to set the agenda and promote their policy preferences (Riker, 1990; Rosenthal, 2014, 2020). It can also result from an uncontrolled process stemming from institutional “friction” that blocks agenda shifts. Alternatively, after the policy problem becomes part of the policy agenda and receives policy attention, agenda cascades and positive feedback loops may begin resulting in disproportional responses to the policy issue (Baumgartner et al., 2009; Walgrave et al., 2006). Hence, the agenda-setting process influences and reflects the structure of power in politics and society (Dowding, 2008).

Policy agenda research that examines policy attention has identified three aspects of policy agendas: the actual content of the policy issues on the agenda, their diversity, and the distribution of the policy attention (Alexandrova et al., 2012). In terms of content, there is a distinction between core and peripheral policy issues (Jennings et al., 2011). Core issues include defense, international affairs, the economy, and government operations (Jennings et al., 2011). For players such as political parties seeking to affect the policy agenda to promote their political purposes, there should be a focus on these topics (Walgrave et al., 2006).

Hence, once judges decide to handle core political topics that affect policy processes (Hirschl, 2008), these topics should receive more policy attention. Furthermore, in terms of agenda diversity, in judicializing courts there should be little diversity in the topics on the agenda (Boydstun et al., 2014). Moreover, there should be a rather flat distribution of the attention paid to the topics on the agenda. Thus, judges might review the same set of topics and fend off pressure to include other topics in their agenda. That is, if agenda capacity is limited due to cognitive and physical limits (Rebessi and Zucchini, 2017), allocating space for a topic on the agenda is crucial for anyone seeking to control it (Rosenthal, 2018). In cases where judges have control over their docket and can include cases as they see fit (Skiple et al., 2021), if they want to affect the core topics in politics, they will keep their docket fixed on these core topics. The first hypothesis then is:

Hypothesis 1: If the Court is a judicializing politics court, it will include core political topics on its agenda regularly and deal with only a limited number of topics.

A different model for judicial behavior is the strategic behavior model, which assumes that judges, as purposeful political players, seek to implement their favored policies through their rulings (Epstein and Knight, 1997). Nevertheless, they are also aware of the possibility of maneuvering within an environment based on politicians who can change the institutional rules and affect judicial nominations (Rosenthal et al., 2021). If the strategic approach indeed works, then we expect the following policy agenda structure:

Hypothesis 2: If the Court is a judicializing politics court, it will include core political topics on its agenda regularly and deal with only a limited number of topics, unless facing political pressure.

However, if judges are not focused solely on judicializing politics but are in fact legal problem solvers, then the legal dimension is bound to influence their reasoning alongside the political and social policy dimensions (Braman, 2009). Thus, while judges are influenced by their political and policy preferences, they are guided by judicial doctrines (Lax, 2011). Hence, when presented with a new policy issue, the judges will either rule based on existing legal doctrines or forge new precedents that stand until a new institutional change takes place (Bressman, 2007).

Consequently, regardless of a topic being a core issue, once it finds its way onto the agenda, it will remain there if it were not legally resolved. When the judges devise a doctrine to handle this issue, it will not be introduced again to the agenda. Thus, in agenda-setting terms, we would expect to see all topics (not only core topics) receiving policy attention. We would also expect to see a diverse agenda of topics over time. Moreover, we might see a punctuated agenda. Topics would be handled until a new topic appears on the agenda. Once it is dealt with, the topics would go back to equilibrium until a new issue emerges (Robinson, 2013). A third hypothesis is then:

Hypothesis 3: If the Court functions as a legal problem solver, most policy issues will be on the agenda, making the agenda very diverse and having a punctuated distribution of topics on it.

Israel’s Supreme Court serves as a court of last resort in the Israeli court system. In petitions against the government’s decisions and activities on administrative or constitutional matters, the Supreme Court serves as primarily a first and final instance referred to as the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) (Dotan, 2000). Due to that unique position, while as a Supreme Court which serves as a last resort on legal issues the Court’s agenda would be affected by decisions made on lower courts, as an HCJ the same court faces a diversified stream of petitions usually unfiltered before reaching it. A person or a group who regards an executive activity or a decision as potentially harmful to the petitioner or some more significant collective need can petition the HCJ asking for an injunction, which could eventually become permanent. The initial review process begins with a duty judge who has discretionary power to either dismiss petitions or advance them for further consideration.2 While the duty judge’s rulings require confirmation from two additional judges, these judges are selected by the duty judge (Givati and Rosenberg, 2020). Consequently, the duty judge functions as a pivotal veto player in filtering petitions presented to the Court. This procedural framework was modified in November 2017 but characterizes the period covered by our analysis. If accepted, a panel of three judges reviews the case and can ask for more evidence than already presented. This panel decides on the petition to abolish the injunction or make it permanent. In rare cases of great public importance that the HCJ accepts for review, there would be an extended odd number panel of judges hearing the case (Cohn, 2019).

Is the HCJ a Court with agenda control? For illustrative purposes, let us compare the HCJ to a Court with a high agenda power, namely the US Supreme Court. The Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) differs from the U.S. Supreme Court in terms of its docket control. While the U.S. Supreme Court can selectively grant certiorari to cases appealed from lower courts, thereby maintaining strong agenda-setting powers, the HCJ receives direct petitions on administrative and constitutional matters from individuals and organizations. However, the HCJ still maintains significant agenda control through its initial screening process—cases must pass through a judge on duty and a three-judge panel that can filter out petitions deemed unsuitable for review.

Analysis of the Weinshall-Epstein-Worms database of Israel’s Supreme Court decisions (Weinshall and Epstein, 2020) reveals the extent of this filtering process. Examining HCJ petitions from 2010–2018 shows that of 7,404 total petitions, only 3,609 (48.74%) received consideration on their merits. The filtering process is particularly evident when examining the 2,770 petitions decided within one month of submission: 1,313 (47.4%) received no disposition, 606 (21.87%) were dismissed, and 804 (29%) were rejected. This indicates that judges actively utilize their agenda control powers to screen out a majority of petitions, allowing them to focus judicial review on selected cases they deem warrant consideration. While this represents less extensive docket control compared to the U.S. Supreme Court’s certiorari process, it still provides the HCJ with substantial ability to shape its agenda through case selection and quick rejections.

Due to the constitutional arrangements set by Israel’s Basic Laws, the HCJ has the authority to annul Knesset (parliament) legislation and government decisions. Israel’s Supreme Court decided to take a broad legal interpretation of these laws, thereby expanding the Court’s function concerning constitutional and administrative review (Rosenthal et al., 2021). In the context of administrative judicial review, the HCJ took three steps that increased the scope of its review and its ability to intervene in government decisions if it chooses to do so. One such step was the expansion of the concept of justiciability allowing judges to review issues they previously regarded as non-justiciable (Weill, 2020). The scope of justiciable decisions was further extended by offering standing rights not only to petitioners directly harmed by government decisions but also to public petitioners who could identify some collective level of infringement of rights by the government’s activities (Cohn, 2019).

The HCJ also increased its use of the reasonableness doctrine that scrutinizes government decisions while examining both the process of decision-making and the considerations it offers (Cohn, 2019). This move allowed judges to veto government decisions and set paths to a given line of decisions based on the judges’ considerations of a reasonable decision-making process (Dotan, 2000). Lastly, due to the Basic Laws passed in the 1990s, the Court decided to examine the proportion of constitutional rights that an administrative agent has infringed upon (Cohn, 2019). Many studies have examined the expansion of the HCJ’s role as a policymaker and a policy entrepreneur due to these steps (Barzilai, 1998; Dotan, 1999, 2014; Dotan and Hofnung, 2001; Hofnung, 1996; Hofnung and Weinshall-Margel, 2010; Meydani, 2014; Sommer, 2009; Weinshall-Margel, 2011). Beyond the social and institutional factors that increased the Court’s ability to become involved with core policy issues, the judges’ decisions in the HCJ coincided in varying degrees with ideological positions that are contested in the Israeli political system and did not merely resonate with legal opinions (Rosenthal and Talmor, 2022, 2023; Weinshall et al., 2018). These institutional changes substantially increased the volume of petitions filed before the HCJ (Dotan, 2014: 25). However, as demonstrated above, the Court’s agenda-setting powers enable judges to effectively filter the large number of petitions to identify those that warrant substantive review. Through this screening process, HCJ judges can manage their expanding docket despite the liberalization of standing and justiciability rules.

The Israeli political system has not been indifferent to the Court’s expansion of its powers. In 2004 and then 2008, the judges’ nomination system was reformed in a manner that increased the politicians’ influence on judicial nominations. Using these new powers, politicians actively tried to diversify the Court socially and politically. In addition to the reform in nominations, leading politicians acting as ministers of justice engaged in public conflicts with the Court regarding its decisions (Rosenthal et al., 2021). Following these steps, from 2008 onwards, the HCJ seemed more reluctant to engage with government decisions and the policy activities of various ministries (Rosenthal et al., 2021).

Hence, the HCJ offers us a case of a court willing to engage head-on with the task of judicializing politics, while also demonstrating strategic prudence and variation in the judges’ preferences that potentially avoid a move toward judicialization. In terms of case study research, this variation allows us to examine phenomena taking place in one setting but under diverse conditions (Gerring and McDermott, 2007). These circumstances allow us to test hypotheses as the basis for better understanding the case. We can also use it as a heuristic case study that can serve as a starting point for the analysis of other cases (Eckstein, 2000).

We examined our hypotheses using Rosenthal-Barzilai-Meydani’s (RBM) original dataset of Israel’s High Court of Justice decisions (Rosenthal et al., 2021). We then recoded them using the Comparative Agendas Project coding system (Bevan, 2019) as applied to the Israeli context (Cavari et al., 2022). The RBM dataset contains a set of petitions that received certiorari and on-merits decisions by the Israeli High Court of Justice between 1995 and 2018. This period begins after the Court determined that it could directly overturn the government’s legislation and ends (for now) at a point where the Court is under direct political pressure to restrain its involvement in state affairs (Roznai and Cohen, 2023).

The dataset does not include petitions that received certiorari but were withdrawn by the petitioners or became irrelevant due to out-of-court settlements. Moreover, this dataset includes only petitions that were aimed at the Prime Minister, ministers, and deputy ministers. In comparison to thousands of petitions the Court reviewed during that period (Dotan, 2014; Weinshall and Epstein, 2020), the RBM dataset contains 2,674 case decisions. Nevertheless, this dataset provides a glimpse at the decisions that received the highest level of attention and consideration from the Court and had clear policy purposes (Rosenthal et al., 2021). In other words, this is a set of policy issues that the judges selected to be on their docket after the filtering processes. The first was the consideration of other cases by the Court and its judges. The second was the decision of other parties in the petitions to settle out of court or voluntarily withdraw their cases.

The Comparative Agendas Project (CAP) coding scheme developed its methodological tools in order to examine policy attention to public policy topics.3 The topics this scheme locates and codes in texts include major public policy topics (21) and many sub-topics (220) that are issues for various political institutions such as political parties, parliaments, government cabinets, state leaders, mass media political coverage and the courts.4 CAP examines trends in policy attention within these institutions in more than a dozen countries. During the coding process, each coder needs to examine whether a topic receives attention in an examined institution. Each unit of analysis (a document, a meeting, committee hearing, a quasi-sentence in a political speech or a newspaper headline) is examined for its main topic. Coders are asked to ascertain that only one topic is coded from the unit of analysis. The goal is to identify the main policy topic that the decision-maker(s) turned their attention to in the text that the coder studies.

The cases included in the RBM dataset were coded by a team of law and government students at Reichman University as part of an Israel Science Foundation funded project. For each case, the students needed to ascertain whether it was indeed fully reviewed by the Court. They also categorized the case into Dotan’s (2014) legal sub-fields. Finally, they determined the institutional identity of the petitioner (government sector, private sector or a non-governmental organization), and whether the petitioner was an Arab or a Jew. Other contextual variables included whether the case related to the issue of state and religion or the territories Israel occupied in 1967 and still governs. The coders achieved an above 90% level of inter-coder reliability. Their coding process was based on reading the text summary in the RBM data or the abstract at the beginning of the Court’s final decision. Hence, the key variable regarding the proportion of public policy topics was a case coded in accordance with the CAP topics and subtopics. We also measured changes in the distribution of the policy topics considered and the degree of diversity in the policy topics on which the Court ruled.

We used L-kurtosis to monitor the change in the distribution of the policy topics considered. L-kurtosis assesses such changes using three measures: a normal distribution, a completely flat distribution, or a punctuated distribution. In a normal distribution there is little difference between the values of the various policies, a fact that could indicate a proportional attention rate to a given set of topics. A completely flat distribution could reflect equal attention being paid to a given set of topics. Finally, a punctuated distribution could include higher than normal variations between distribution values, indicating a disproportional policy response to some topics on the agenda. An L-kurtosis value of 0.123 reflects a normal distribution. A value that approaches zero reflects a flatter distribution. A value that exceeds 0.123 reflects a more punctuated distribution. This result suggests a punctuated distribution with higher bursts of policy attention for specific periods of time (Baumgartner et al., 2009).

There are various methods for comparing the range of policy attention within a given space or time. We used an index called Shannon H, which is considered the most effective for this purpose (Boydstun et al., 2014). This index monitors changes in the amount of attention paid to an issue. It does so by measuring changes in the variety of information items to which institutions or individuals direct their attention compared to the number of items to which this attention could be directed (Boydstun et al., 2014). When all attention is focused on one item, this index would receive the value of 0. The more distributed the attention among items, the higher the Shannon H index will be. The index is calculated as the natural log value of the number of items vying for attention (Alexandrova et al., 2012).

To test the hypotheses, we must look at the distribution of the topics the Court considered (normal, flat, or punctuated) and their diversity, measured as their Shannon H score. For hypothesis one (the attitudinal model), we expect a flat distribution and a limited number of topics. For hypothesis two (the strategic model), we expect a normal distribution with a medium level of diversity with regard to the topics. For hypothesis three (the legal problem solvers model), we expect to see a punctuated distribution and a diverse policy agenda in Israel’s High Court of Justice.

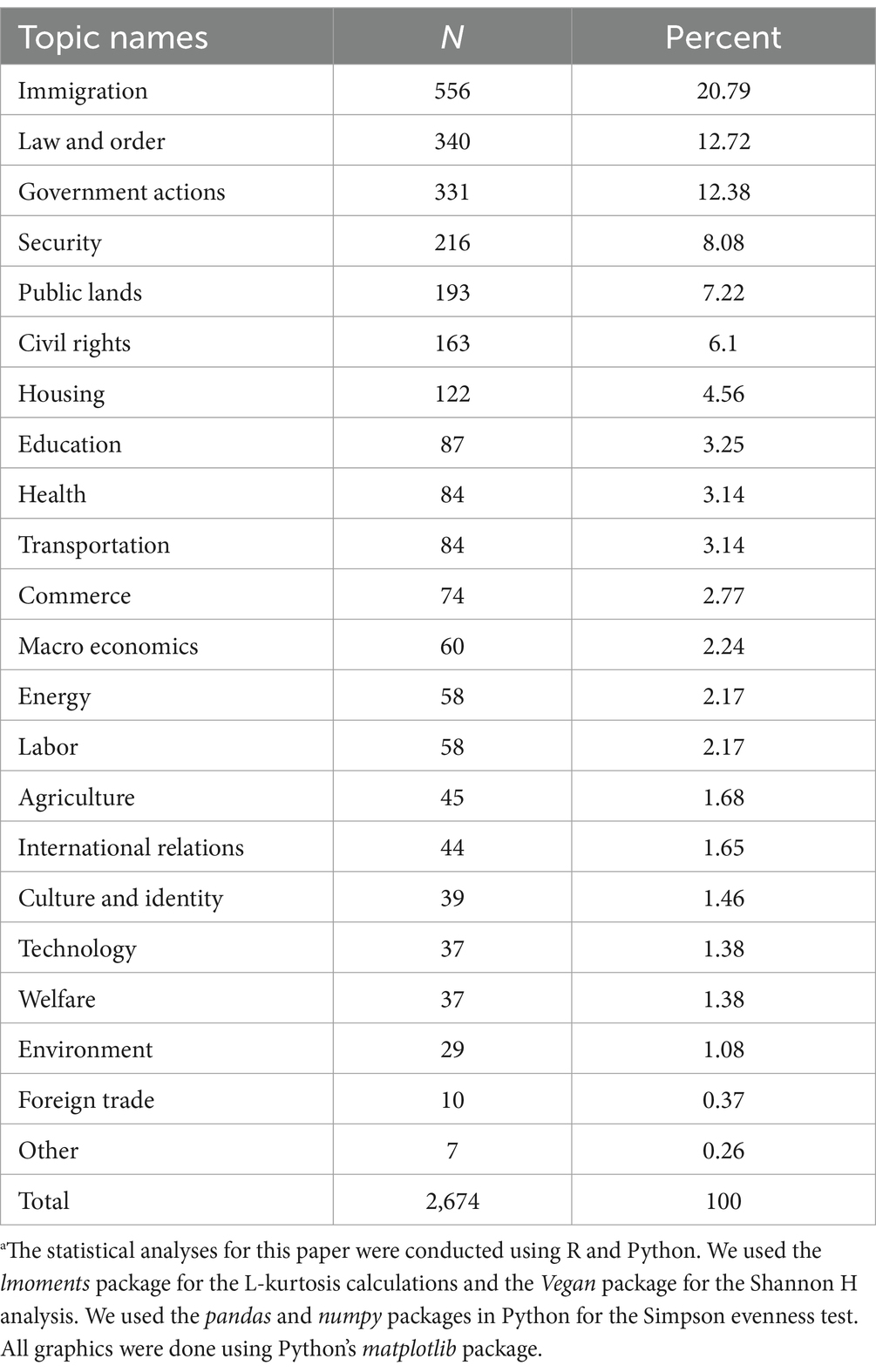

Table 1 lists the various policies on which the HCJ ruled between 1995 and 2018, including their number and percentage of the total number of decisions the Court handed down during that period.

Table 1. HCJ decisions on policies, 1995–2018a.

As the table indicates, the five topics dealt with most often were petitions regarding immigration, law and order, government actions, security, and public lands. In order to explore the dynamics of the Court’s agenda and the judicialization of politics, we examined how the Court’s decisions coincided with Israel’s core issues. These issues include Israel’s control over the territories it occupied in the 1967 war and issues related to the relationship between the state and religion (Arian and Shamir, 2008). Figure 1 uses a heat map design to illustrate the relationship between the five leading topics on which the Court ruled and the two core policy issues related to the occupied territories and the state and religion.

As the figure illustrates, the Court is willing to consider core topics on its agenda. However, the figure also indicates that these issues are not the only ones on which the Court focuses its attention. Some have maintained that the HCJ is the only Israeli political institution willing to be explicitly involved with the Israeli occupation (Cavari et al., 2022). Indeed, the HCJ made this commitment itself in the very early days of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip (Kretzmer, 2012). Hence, the Court is involved in a core political topic, but the extent to which it is trying to be a political, policy, or legal entrepreneur in this area is unclear.

Let us focus on the most salient policy topics on which the Court has ruled: immigration, law and order, government activities, security, public lands, and civil rights.

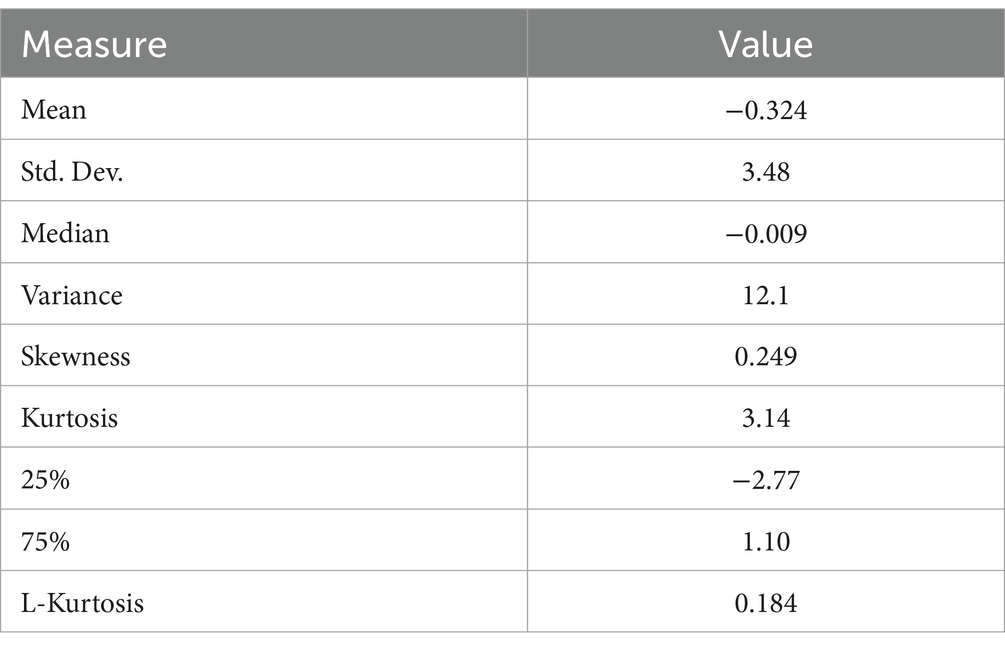

As Figure 2 shows, over time, the attention that the HCJ has paid to these topics has varied. Hence, while these topics relate to the major issues on the Israeli political agenda, they do so in varying degrees in any given year. To obtain a broader picture of this variation, we calculated the median of the annual percentage in the change in attention paid to the five most salient topics as a variable of its own. An increase in these topics’ presence on the Court’s agenda would increase this variable’s values and vice versa. We then calculated this variable’s main summary statistics. Table 2 presents the results.

Figure 2. Most salient topics and proportion of attention the HCJ has paid to them annually, 1995–2018.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the change in the HCJ’s attention to the five most salient topics.

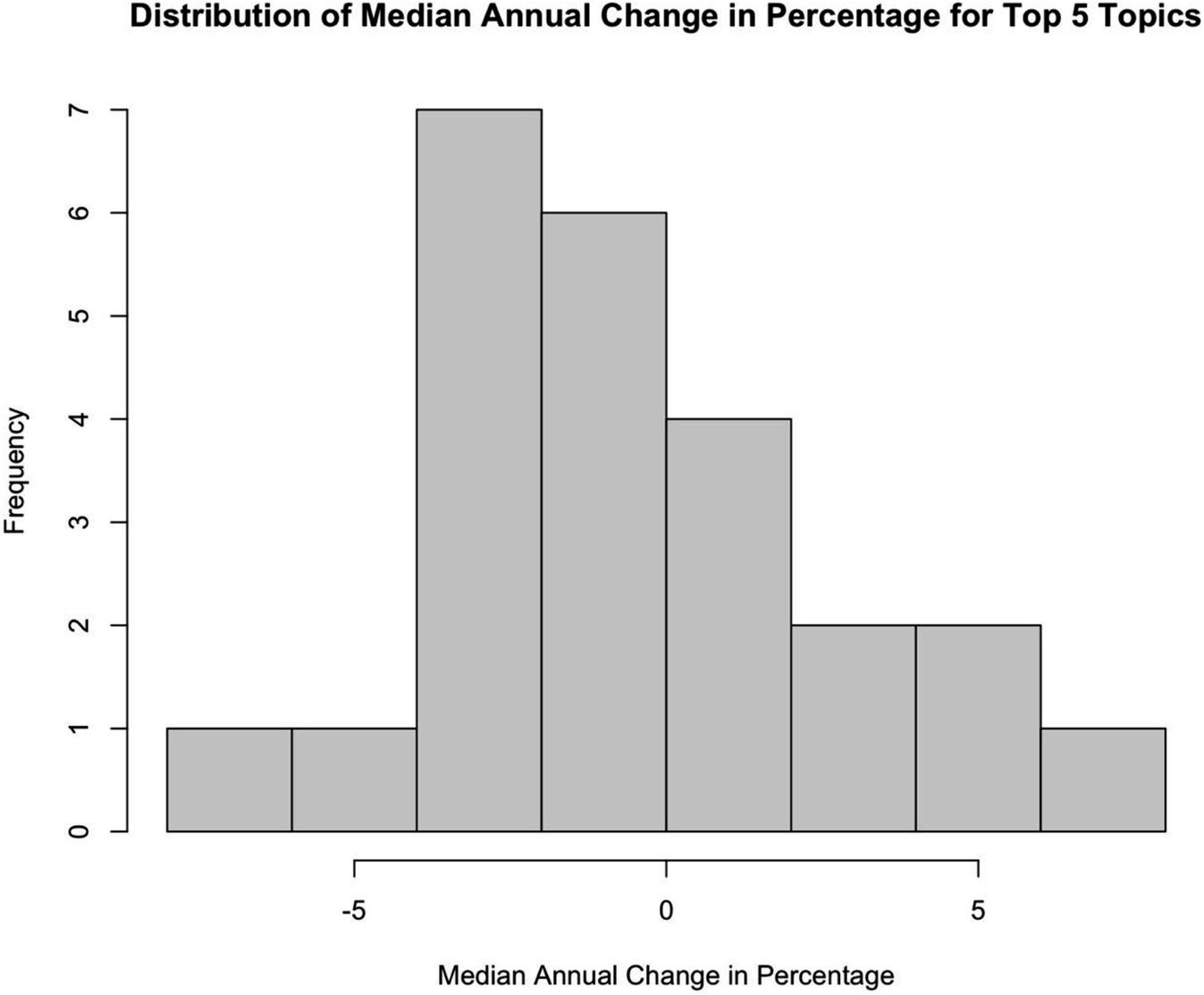

The mean value indicates a negative distribution of the median change in the attention paid to these five topics. The Kurtosis value shows that this is not a normal distribution. As noted earlier, in the CAP literature, a value of 0.123 for the L-kurtosis measure indicates a normal distribution. However, our calculation of an L-kurtosis value of 0.184 points to a punctuated distribution. This measure is similar to the change in the rate of attention evident in legislatures, party policy inter-agreements, and the European council resolutions (Alexandrova et al., 2012). As such, it is similar to policy output agendas where the ability to move between topics is relatively easy with few veto players creating institutional friction. Institutions handling the output side of the policy process include government, bureaucracies, and legislatures. The deviation from the normal distribution, even though it is minor, reflects the Court’s handling of policy agendas as part of the policy output side with the institutional ability to design this side. Hence, in terms of the hypotheses we proposed, hypothesis three about the judges as legal problem-solvers best depicts the overall picture of the HCJ’s agenda. Figure 3 presents a histogram that illustrates the distribution of the annual changes in the Court’s median attention to the five leading topics.

Figure 3. The distribution of the annual changes in the court’s median attention to the five leading topics.

After examining the distribution of the attention the Court paid to the five topics, the next question is the topics’ diversity. Does the Court focus on only a few topics, or does it does it deal with a variety of topics? As noted earlier, we used Shannon’s Diversity Index H (Alexandrova et al., 2012) to investigate this question (see Figure 4).

In this case of 23 years, the maximum value of the Shannon H diversity measure was 3.044 (the natural log of 21 items). A value of 0 indicates a focus on only one topic. The higher the value, the more diversified the topics on which the Court ruled during those 23 years. The HCJ data show that the only two years in which the level of diversity was the lowest were 1995 and 2018. In both cases, we lacked information about all of the months of those years. The level of diversity was the highest in 2002, 2012, and 2014 with increases and decreases ranging between a Shannon H value as high as 2.7 and as low as 2.13. The mean Shannon H value was 2.41.5 Thus, in terms of the Court’s policy agenda, the Court behaves like other output institutions with a non-normal distribution of topics on its agenda and a relatively high level of diversity among these topics.

However, there are specific periods (1995–1997 and then again in 2005) where the Court’s agenda focuses on fewer topics, therefore projecting a more activist-partisan behavior. It is also interesting to note that from the moment the Ministers of Justice diversified the Court’s composition, so did the Court’s agenda. Therefore, once again, hypothesis three in which the judges act as legal problem solvers seems to be the best fit with the data about the diversity of the topics on which the Court ruled. Given our findings, we would conclude that the Court functions as a legal problem solver rather than a partisan seeking to impose its preferred ideology as its sole output. However, that trend may shift between periods and stem from particular Court compositions.

In this paper, we presented three hypotheses about the role of Israel’s High Court of Justice based on empirical expectations derived from the agenda-setting aspects of the judicialization of politics hypothesis. This approach serves two purposes: examining a widely used hypothesis in judicial politics and assessing the Israeli High Court of Justice’s (HCJ) supposed judicial activism. Theoretically, we proposed that a judiciary seeking to judicialize politics would maintain a non-diverse agenda focused on core topics with minimal shifts. Conversely, a court acting as a legal problem solver would address a diverse range of topics driven by external policy issues. Using the Comparative Agendas Project’s conceptual and empirical framework (Jones and Baumgartner, 2005), we hypothesized that such a court’s agenda would be punctuated, alternating between stability and periodic spikes in the attention it paid to various issues.

Analysis of the HCJ, a court that balances judicialization and politicization, reveals that the Court’s agenda is mostly diverse, with a punctuated distribution of its attention across topics. These findings align more closely with the approach of a court that has adopted a legal problem-solving approach than one interested in the judicialization of politics. While evidence confirms the HCJ’s engagement with core political issues (Hirschl, 2008, 2009b; Meydani, 2014; Rosenthal and Talmor, 2022; Sommer, 2009; Weinshall et al., 2018; Weinshall-Margel, 2011), the Court’s role in policymaking appears more sophisticated than conventional notions of judicial activism would suggest (Weinshall, 2024). Drawing on Weinshall’s concept of “involved activism,” where judicial influence operates through subtle mechanisms such as rhetoric and deliberation rather than through explicit vetoes in final decisions (Weinshall, 2024), we can better understand how the Court shapes policy. By incorporating certain policy questions into its agenda, the Court can exercise involved activism by structuring deliberative processes between government actors and petitioners, even when its final rulings do not directly intervene in policy outcomes. Analysis of agenda diversity metrics reveals that the Court occasionally exhibits more partisan behavior, lending support to critiques of judicial overreach and claims of juristocracy (Hirschl, 2008, 2009b). However, examination of agenda-setting patterns suggests that such juristocratic tendencies emerge primarily during specific periods and manifest through sophisticated legal reasoning rather than through direct confrontation with other branches of government.

These findings have implications for both judicial behavior theory and Israel’s ongoing political crisis. Since 2018, Israel has faced political instability, partly attributed to corruption allegations that have led to criminal proceedings against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and a trial (Rosenthal, 2024). Within that context right-wing politicians have framed the HCJ’s “activism” as a source of this political turmoil, proposing reforms to curtail its powers (Sommer and Braverman, 2024). However, this study indicates that the Court’s involvement in political matters is limited and primarily reflects constitutional rather than political ambitions. Hence, the judicial reforms proposed by Netanyahu and his coalition partners since 2022 can be understood not only through the lens of the Court’s actions (Gerber and Givati, 2023), but also by examining the politicians’ conduct and their motivations for political self-preservation (Atmor and Hofnung, 2024).

In conclusion, this research demonstrates the value of policy agenda analysis in studying judicial behavior. It provides new insights into the complex role that courts play in policymaking, transcending traditional activism-restraint dichotomies. The findings suggest that proposed judicial reforms in Israel should consider broader political dynamics rather than focusing solely on the Court’s behavior.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

MR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This paper was funded by ISF grant 1271/18, which is part of the Israeli Political Agendas Project (CAP-IL).

We thank Lihi Ben-Yaakov, Shay Klot, Tom Nadil, Natali Assaf, and Noy Berger for their exceptional research assistance. We benefited from the comments made by participants at the Comparative Agendas Project's annual conference at Reichman University in 2022. Special thanks to Amnon Cavari, Asif Efrat, Yaniv Roznai, and Raanan Sulitzeanu-Kenan for their thoughtful comments and ideas on earlier versions of this paper. Responsibility for faults and errors is ours.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^This review loosely follows Rosenthal and Talmor (2022).

2. ^See Section 5 of the High Court of Justice Proceedings Rules [in Hebrew], available at: https://www.nevo.co.il/law_html/law00/98565.htm

3. ^See: https://www.comparativeagendas.net.

4. ^While alternative methodologies such as topic modeling can reveal patterns through inductive reasoning that might elude deductive approaches, this initial application of agenda-setting frameworks to comparative judicial politics employs an established coding scheme validated across multiple policy domains. Future research will incorporate topic modeling and deep learning techniques to address potential conceptual ambiguities.

5. ^To improve our results’ validity, we also used Simpson’s evenness measure to examine topics’ diversity. Since these measures use different formulas and calculate various aspects of diversity, their comparison might raise methodological difficulties (Morris et al., 2014). However, in this case, both measures point to similar trends: a decline in diversity during 1995–1997, an increase in diversity until 2004, a sharp decline in 2005, with an ongoing rise until 2014.

Alexandrova, P., Carammia, M., and Timmermans, A. (2012). Policy punctuations and issue diversity on the European council agenda. Policy Stud. J. 40, 69–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00434.x

Arian, A., and Shamir, M. (2008). A decade later, the world had changed, the cleavage structure remained: Israel 1996–2006. Party Polit. 14, 685–705. doi: 10.1177/1354068808093406

Atmor, N., and Hofnung, M. (2024). “Public opinion and public Trust in the Israeli Judiciary” in Judicial Independence: Cornerstone of democracy eds. Shimon Shetreet and Hiram Chrdosh. (Brill Nijhoff), 183–203.

Barzilai, G. (1998). Courts as hegemonic institutions: the Israeli supreme court in a comparative perspective. Israel Affairs 5, 15–33. doi: 10.1080/13537129908719509

Baumgartner, F. R., Breunig, C., Green-Pedersen, C., Jones, B. D., Mortensen, P. B., Nuytemans, M., et al. (2009). Punctuated equilibrium in comparative perspective. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 53, 603–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00389.x

Bevan, S. (2019). “Gone fishing: the creation of the comparative agendas project master codebook” in Comparative policy agendas: Theory, tools, data. eds. F. R. Baumgartner, C. Breunig, and E. Grossman (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 17–34.

Boydstun, A. E., Bevan, S., and Thomas III, H. F. (2014). The importance of attention diversity and how to measure it. Policy Stud. J. 42, 173–196. doi: 10.1111/psj.12055

Braman, E. (2006). Reasoning on the threshold: testing the Separability of preferences in legal decision making. J. Polit. 68, 308–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00408.x

Braman, E. (2009). Law, politics, and perception: How policy preferences influence legal reasoning. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Bressman, L. S. (2007). Procedures as politics in administrative law. Columbia Law Rev. 107, 1749–1821.

Cavari, A., Rosenthal, M., and Shpaizman, I. (2022). Introducing a new dataset: the Israeli policy agendas project. Israel Stud. Rev. 37, 1–30. doi: 10.3167/isr.2022.370102

Cohn, M. (2019). “Judicial deference to the Administration in Israel” in Deference to the Administration in Judicial Review. ed. G. Zhu (New-York: Cham Springer), 231–269.

Couso, J. A., Huneeus, A., and Sieder, R. (Eds.) (2010). Cultures of legality: Judicialization and political activism in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dotan, Y. (1999). Judicial rhetoric, government lawyers, and human rights: the case of the Israeli high court of justice during the intifada. Law Soc. Rev. 33, 319–363. doi: 10.2307/3115167

Dotan, Y. (2014). Lawyering for the rule of law: Government lawyers and the rise of judicial power in Israel. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dotan, Y., and Hofnung, M. (2001). Interest groups in the Israeli high court of justice: measuring success in litigation and in out-of-court settlements. Law Policy 23, 1–27. doi: 10.1111/1467-9930.t01-1-00100

Dotan, Y. (2000). “Judicial activism in the Israeli high court of justice” in Judicial activism: For and against, the role of the high court of justice in Israeli society. eds. R. Gavison and M. Kremnitzer (Jerusalem: Magnes Press), 5–65.

Dowding, K. (2008). Power, capability and Ableness: the fallacy of the vehicle fallacy. Contemp. Polit. Theory 7, 238–258. doi: 10.1057/cpt.2008.23

Dowding, K., Hindmoor, A., and Martin, A. (2016). The comparative policy agendas project: theory, measurement and findings. J. Publ. Policy 36, 3–25. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X15000124

Eckstein, H. (2000). “Case Study and Theory in Political Science.” In Case Study Method : Key Issues, Key Texts, eds. Roger Gomm, Martyn Hammersley, and Peter Foster. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Epstein, L., and Knight, J. (2013). Reconsidering judicial preferences. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 16, 11–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-032211-214229

Epstein, L., and Shvetsova, O. (2002). Heresthetical maneuvering on the US supreme court. J. Theor. Polit. 14, 93–122. doi: 10.1177/095169280201400106

Gerber, A., and Givati, Y. (2023). How did the 'Constitutional Revolution' affect the Public's Trust in the Court? Mishpatim 53, 1–50. (Hebrew)

Gerring, J., and McDermott, R. (2007). An experimental template for case study research. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 688–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00275.x

Ginsburg, T. (2008). "The global spread of constitutional review." In: Oxford handbook of law and politics, eds. E. Whittington Keith and Kelemen, R. Daniel. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Givati, Y., and Rosenberg, I. (2020). How would judges compose judicial panels? Theory and evidence from the supreme court of Israel. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 17, 317–341. doi: 10.1111/jels.12247

Green-Pedersen, C., and Walgrave, S. (2014). “Political agenda setting: an approach to studying political systems” in Agenda setting, policies, and political systems: A comparative approach. eds. C. Green-Pedersen and S. Walgrave (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 1–16.

Hirschl, R. (1998). Israel's 'Constitutional Revolution': the legal interpretation of entrenched civil liberties in an emerging neo-Liberal economic order. Am. J. Compar. Law 46, 427–452. doi: 10.2307/840840

Hirschl, R. (2008). The Judicialization of mega-politics and the rise of political courts. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 11, 93–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053006.183906

Hirschl, R. (2009a). The socio-political origins of Israel's Juristocracy. Constellations 16, 476–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8675.2009.00554.x

Hirschl, R. (2009b). Towards Juristocracy: the origins and consequences of the new constitutionalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hofnung, M. (1996). The unintended consequences of unplanned constitutional reform: constitutional politics in Israel. Am. J. Compar. Law 44, 585–604. doi: 10.2307/840622

Hofnung, M., and Weinshall-Margel, K. (2010). Judicial setbacks, material gains: terror litigation at the Israeli high court of justice. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 7, 664–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-1461.2010.01192.x

Huq, A. Z., and Ginsburg, T. (2017). How to lose a constitutional democracy. UCLA Law Rev. 65, 78–169. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2901776

Jacobsohn, G. J., and Roznai, Y. (2020). Constitutional Revolution. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Jennings, W., Bevan, S., Timmermans, A., Breeman, G., Brouard, S., Chaqués-Bonafont, L., et al. (2011). Effects of the Core functions of government on the diversity of executive agendas. Comp. Pol. Stud. 44, 1001–1030. doi: 10.1177/0010414011405165

Jones, B. D., and Baumgartner, F. R. (2005). The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems. University of Chicago Press.

Kretzmer, D. (2012). The law of belligerent occupation in the supreme court of Israel. Int. Rev. Red Cross 94, 207–236. doi: 10.1017/S1816383112000446

Lax, J. R. (2011). The new judicial politics of legal doctrine. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 14, 131–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.042108.134842

Meydani, A. (2014). The anatomy of human rights in Israel: Constitutional rhetoric and state practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morris, E. K., Caruso, T., Buscot, F., Fischer, M., Hancock, C., Maier, T. S., et al. (2014). Choosing and using diversity indices: insights for ecological applications from the German biodiversity Exploratories. Ecol. Evol. 4, 3514–3524. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1155

Rebessi, E., and Zucchini, F. (2017). The role of the Italian constitutional court in the policy agenda: persistence and change between the first and Second Republic. Italian Polit. Sci. Rev. 48, 289–305. doi: 10.1017/ipo.2018.12

Riker, W. H. (1990). “Heresthetic and rhetoric in the spatial model” in Advances in the spatial theory of voting. ed. M. James (Enelow and Melvin J. Hinich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 46–65.

Robinson, R. (2013). Punctuated equilibrium and the supreme court. Policy Stud. J. 41, 654–681. doi: 10.1111/psj.12036

Rosenthal, M. (2014). Policy instability in a comparative perspective: the context of Heresthetic. Political Studies 62, 172–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12026

Rosenthal, M. (2018). Agenda control by committee chairs in fragmented multi-party parliaments: a Knesset case study. Israel Stud. Rev. 33, 61–80. doi: 10.3167/isr.2018.330105

Rosenthal, M. (2020). Strategic agenda setting and prime Ministers' approval ratings: the Heresthetic and rhetoric of political survival. Br. Polit. 15, 63–86. doi: 10.1057/s41293-020-00137-5

Rosenthal, M., Barzilai, G., and Meydani, A. (2021). Judicial review in a defective democracy: judicial nominations and judicial review in constitutional courts. Journal of Law and Courts 9, 137–157. doi: 10.1086/712655

Rosenthal, M., and Talmor, S. (2022). Estimating the 'Legislators in Robes': measuring Judges' political preferences. Just. Syst. J. 43, 373–390. doi: 10.1080/0098261X.2022.2102455

Rosenthal, M., and Talmor, S. (2023). “A court of law or a court of judges?” in Research handbook on law and political systems eds. R. M. Howard, K. A. Randazzo, and R. A. Reid. (Edward Elgar Publishing), 85–98.

Roznai, Y., and Cohen, A. (2023). Populist constitutionalism and the judicial overhaul in Israel. Israel Law Rev. 56, 502–520. doi: 10.1017/S0021223723000201

Segal, J. A. (2010). “Judicial behavior” in The Oxford handbook of political science. ed. R. E. Goodin (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Shapiro, M., and Sweet, A. S. (1994). The new constitutional politics of Europe. Comp. Pol. Stud. 26, 397–420. doi: 10.1177/0010414094026004001

Sheehan, R. S., Gill, R. D., and Randazzo, K. A. (2012). Judicialization of politics: The interplay of institutional structure, legal doctrine, and politics on the high court of Australia. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Skiple, J. K., Bentsen, H. L., and McKenzie, M. J. (2021). How docket control shapes judicial behavior: a comparative analysis of the Norwegian and Danish supreme courts. J. Law Courts 9, 111–136. doi: 10.1086/712654

Sommer, U. (2009). Crusades against corruption and institutionally-induced strategies in the Israeli supreme court. Israel Affairs 15, 279–295. doi: 10.1080/13537120902983031

Sommer, U., and Braverman, R. (2024). “A proposed constitutional overhaul and the question of judicial Independence ” in Open Judicial Politics. 3E Vol. 2, eds. R. S. Solberg and E. N. Waltenburg. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University.

Stearns, M. L. (2002). Constitutional process: A social choice analysis of supreme court decision making. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Sweet, A. S. (1999). “Judicialization and the Construction of Governance.” Comparative Political Studies. 32, 147–84.

Tate, C. Neal. (1995). "Why the expansion of judicial power?" In The global expansion of judicial power, eds. C. Neal Tate and Vallinder, Torbjörn. New York: New York University Press, 27–37.

True, J. L., Jones, B. D., and Baumgartner, F. R. (2019). “Punctuated-Equilibrium Theory: Explaining Stability and Change in Public Policymaking.” In Theories of the Policy Process, Second Edition, ed. A Paul Sabatier. New-York: Routledge, 155–87.

Walgrave, S., Varone, F., and Dumont, P. (2006). Policy with or without parties? A comparative analysis of policy priorities and policy change in Belgium, 1991 to 2000. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 13, 1021–1038. doi: 10.1080/13501760600924035

Weill, R. (2020). The strategic common law court of Aharon Barak and its aftermath: on judicially-led constitutional revolutions and democratic backsliding. Law Ethics Hum. Rights 14, 227–272. doi: 10.1515/lehr-2020-2017

Weinshall, K. (2024). Reconceptualizing judicial activism: intervention versus involvement in the Israeli supreme court. J. Law Emp. Anal. 1:2755323X241272140. doi: 10.1177/2755323X241272140

Weinshall, K., and Epstein, L. (2020). Developing high-quality data infrastructure for legal analytics: introducing the Israeli supreme court database. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 17, 416–434. doi: 10.1111/jels.12250

Weinshall, K., Sommer, U., and Ritov, Y. (2018). Ideological influences on governance and regulation: the comparative case of supreme courts. Regul. Govern. 12, 334–352. doi: 10.1111/rego.12145

Weinshall-Margel, K. (2011). Attitudinal and neo-institutional models of supreme court decision making: an empirical and comparative perspective from Israel. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 8, 556–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-1461.2011.01220.x

Keywords: judicialization of politics, judicial activism, policy attention, policy punctuations, Israel’s high court of justice

Citation: Rosenthal M and Meydani A (2025) The agenda premises of the judicialization of politics: policy attention in Israel’s high court of justice. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1533270. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1533270

Received: 23 November 2024; Accepted: 14 January 2025;

Published: 29 January 2025.

Edited by:

Roi Zur, University of Essex, United KingdomReviewed by:

Udi Sommer, Tel Aviv University, IsraelCopyright © 2025 Rosenthal and Meydani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence:Maoz Rosenthal, bWFvenJvQGVkdS5oYWMuYWMuaWw=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.