- Department of Marketing and Communication, University of Cadiz, Jerez de la Frontera, Cadiz, Spain

Spain is a proven tourist power, with a sector that contributes a high figure to the country’s economy. However, in recent years, tourist activity, especially in large cities, has encountered opposition from neighborhood groups that fight for a decrease in tourism, in order to preserve the identity of their neighborhoods and their living conditions. This research aims to describe the communication strategies employed by these citizen pressure groups on the social network X. For this purpose, an exploratory study was conducted using a quantitative methodology, whose main technique was content analysis, which was applied to a sample of 1,160 publications of 15 entities from different Spanish provinces. The results show that the main topics covered are related to the demonstrations and protest actions of these groups, as well as the tourism policies developed by authorities and the work meetings among different groups. Mobilization appears as a main objective, since 38.8% of the publications presented a tone of protest or denunciation. However, the findings also suggest that the social network X may be more suited to indirect lobbying actions.

1 Introduction

Tourism is one of the most important sectors for the Spanish economy. According to Exceltur data, in 2023 it contributed more than 186,000 million euros, representing 12.8% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (González, 2024). In the first months of 2024, tourist spending increased by 17.6% over the previous year (Torres and Carrera, 2024). However, in recent years, various groups have expressed their concern about the negative effects that this activity has on the most visited cities and their inhabitants, so that mobilizations have been carried out to achieve greater regulation, especially of the so-called tourist apartments. Thus, for example, in the city of Seville, located in Andalusia, in southern Spain, the number of tourist apartments has been limited to a maximum of 10% of the total number of apartments in each of the city’s neighborhoods (Daza, 2024).

Tourism growth, experienced especially by urban destinations, is a consequence of factors such as policies to stimulate tourism and foreign investors, new modes of transportation, vacation rental platforms and international diffusion (Zaar, 2019). But, taken to the extreme, it has given rise to phenomena such as touristification or overtourism and gentrification.

The phenomenon of touristification has a direct and diverse impact on cities receiving mass tourism and their inhabitants (Barrero-Rescalvo, 2019), as it entails a dynamic of transformation of the urban territory (Fioravanti, 2022). Calle-Vaquero (2019) characterizes this process as a situation in which there is a greater presence of visitors in the public space, so that a specific demand is generated by which establishments, which previously catered to the local population, end up focusing their activity, schedules and prices on tourists. This, together with other factors, results in the displacement of the population from their neighborhoods of origin. In fact, Petroman et al. (2022) define this phenomenon as “an antithesis of responsible tourism” (p. 179), which has an economic, environmental and sociocultural impact.

Some negative consequences of this process of touristification are the proliferation of tourist apartments, which influences the housing market, or the saturation of public space (Fioravanti, 2022; Mansilla-López, 2019a,b; Zaar, 2019). Precisely, that modification of the rental market derived from the preferences, on the part of the owners, for shorter and more beneficial rents focuses one of the current claims of different neighborhood groups.

As Genç et al. (2022) argue, the tourism sector “accelerates the gentrification process in urban places” (p. 127), giving rise to a dynamic whereby traditional neighbors, usually more vulnerable or with lower economic capacities, are displaced from their neighborhoods by a population with greater purchasing power to which their living conditions are adapted (Rodríguez-Barcón et al., 2021). Gentrification differs from touristification in that the former generates a new stable social fabric, while the latter is ephemeral (Hernández-Cordero, 2021), although, on many occasions, they are closely related phenomena, as a consequence of the implementation of growth models by public authorities (Romero-Padilla et al., 2019). This is what some authors define as tourist gentrification (Gotham, cited by Genç et al., 2022), whose main consequence is the displacement of the original population, as mentioned above, to increase tourist activity through greater investment, for example, in tourist rentals.

This situation has given rise to a critical attitude among numerous neighborhood groups that have mobilized to demand measures from the public authorities to regulate tourist activity and its consequences on its inhabitants (Fioravanti, 2022). In this way, groups that used to deal with other social struggles are now also against a tourist activity that they consider a source of inequalities (Milano, 2018). Some of these mobilizations, due to their characteristics or vehemence, have been categorized from some sectors as tourismphobia, a phenomenon that has even been interpreted as an ideological struggle between two well-defined positions, for and against tourism growth (Huete and Mantecón, 2018; Soliguer-Guix, 2023).

The mobilization of different local entities to demand control measures from the public authorities refers to the concepts of pressure groups and lobbying. Pressure groups aim to achieve changes in legislation favorable to their interests (Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024), thus transferring the demands of part of the population to the public authorities without the pretension of being part of those authorities (Castillo-Esparcia, 2020). There are two basic ways of developing lobbying activity: direct lobbying, understood as direct communication with public decision-makers (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2022), mainly through interviews and meetings with political officials and civil servants and the delivery of documentation or reports (Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024); and indirect lobbying or grassroots lobbying, through public opinion, media and, more recently, social media (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2022; Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024), among others. Strategic planning and public relations actions play, therefore, a fundamental role in this relationship work adapted to each type of public (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2017).

The actions that the different social movements carry out toward the media and toward the citizenry through the street itself or social networks, in addition to the associative component, lead them to become pressure groups that try to influence political decisions regarding tourism (Romero-Padilla et al., 2019), as a way of questioning the city model generated by mass tourism (Gil and Sequera, 2018).

Although in cities such as Barcelona there have been anti-tourism movements since the beginning of the 21st century (González-Reverté and Soliguer-Guix, 2024), Hughes (2018) points out that, in Spain, this phenomenon of struggle against mass tourism has intensified especially since 2017, although, at times, a simplified vision has been offered through the media, based on statements about the value of tourism, the description of the protests and the positions for and against, as well as possible solutions for mass tourism (Araya-López, 2021). Grassroots mobilizations, such as those that have occurred recently, are not, therefore, a new phenomenon (Milano et al., 2024), but they do adapt to the times, so that communication through social networks has become another resource for pressure groups, with great potential to reach many people and form favorable currents of opinion among citizens (Casero-Ripollés, 2015).

Considering the above, the aim of this paper is to describe the online communication of citizen pressure groups against touristification and gentrification in Spain.

To achieve this objective, several research questions were established:

RQ1. What type of pressure groups are there against touristification and gentrification?

RQ2. What issues do these entities focus on and which ones generate the most interest among the public?

RQ3. What lobbying actions do they mention and what type of lobbying do they correspond to?

RQ4. Who is the target audience for the online messages of anti-tourism groups and movements?

RQ5. Which actors do they explicitly mention in their messages?

2 Methods

In order to answer the research questions posed, an exploratory study was designed based on a quantitative methodology, whose main technique used was content analysis.

Since this was an exploratory study, a non-probabilistic purposive sample was chosen in order to select the cases that would provide the most representative information. To this end, we first consulted the data from the Spanish Survey on Occupancy in Non-Hotel Tourist Accommodations (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, 2024), especially those centered on tourist apartments, which have been identified as one of the main causes of harm to residents. Below, the top 25 provinces were selected according to the number of this type of housing.

Secondly, the data on travelers in tourist apartments by province were consulted and the top 25 provinces were selected according to this variable. Finally, the territories with the highest number of tourist apartments and travelers were selected. In total, 23 provinces were selected: Las Palmas, Baleares, Alicante, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Málaga, Girona, Castellón, Madrid, Valencia, Tarragona, Almería, Cádiz, Barcelona, Sevilla, Murcia, Asturias, Cantabria, Granada, Pontevedra, Navarra, Huelva, Cáceres and A Coruña.

The next step was to search in the Google search engine using the terms “anti-tourism platforms + name of the province.” From the news items that appeared, a selection of 86 entities named in the information was made. Those that did not have a website were eliminated, as this is the basic online presence, as well as those that did not have profiles on X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram, and those that are no longer active. Likewise, political parties were eliminated, as they were not considered pressure groups. This first sifting resulted in 67 entities, 51 with Instagram and 56 with X social network. Therefore, it was decided to analyze the activity of these entities on X, as it is the social network in which they are most present, in addition to its own characteristics as an ideal medium for the dissemination of information without intermediaries. Finally, once the above requirements had been met, for each province, the entities with the greatest relationship with the tourism and housing sector and with the largest number of followers were chosen.

In this way, a final sample of 15 groups or movements was obtained: Asociación de vecinos Carolinas Bajas-Les Palmeretes (Alicante), Asturies Insumisa (Asturias), Menys Turisme, Més Vida (Baleares), Assemblea de Barris pel Decreixement Turístic (Barcelona), Sindicato de Vivienda - AZET (Bilbao), Cádiz Resiste (Cádiz), Salvar La Tejita (Canarias), Cantabria No Se Vende (Cantabria), BiziLagunEkin (Donostia), Albayzín Habitable (Granada), Sindicato de Inquilinas e Inquilinos de Madrid (Madrid), Sindicato de Inquilinas e Inquilinos de Málaga (Málaga), Sevilla Se Muere (Sevilla), Stop Creuers Tarragona (Tarragona) and Entrebarris (Valencia).

On social network X, we analyzed each entity’s own messages, excluding replies and retweets, since this way the study focuses on the information actually planned by these groups. On the other hand, the period of analysis corresponded to the main summer months of 2024 (June, July and August), when there is the greatest influx of tourists in these territories.

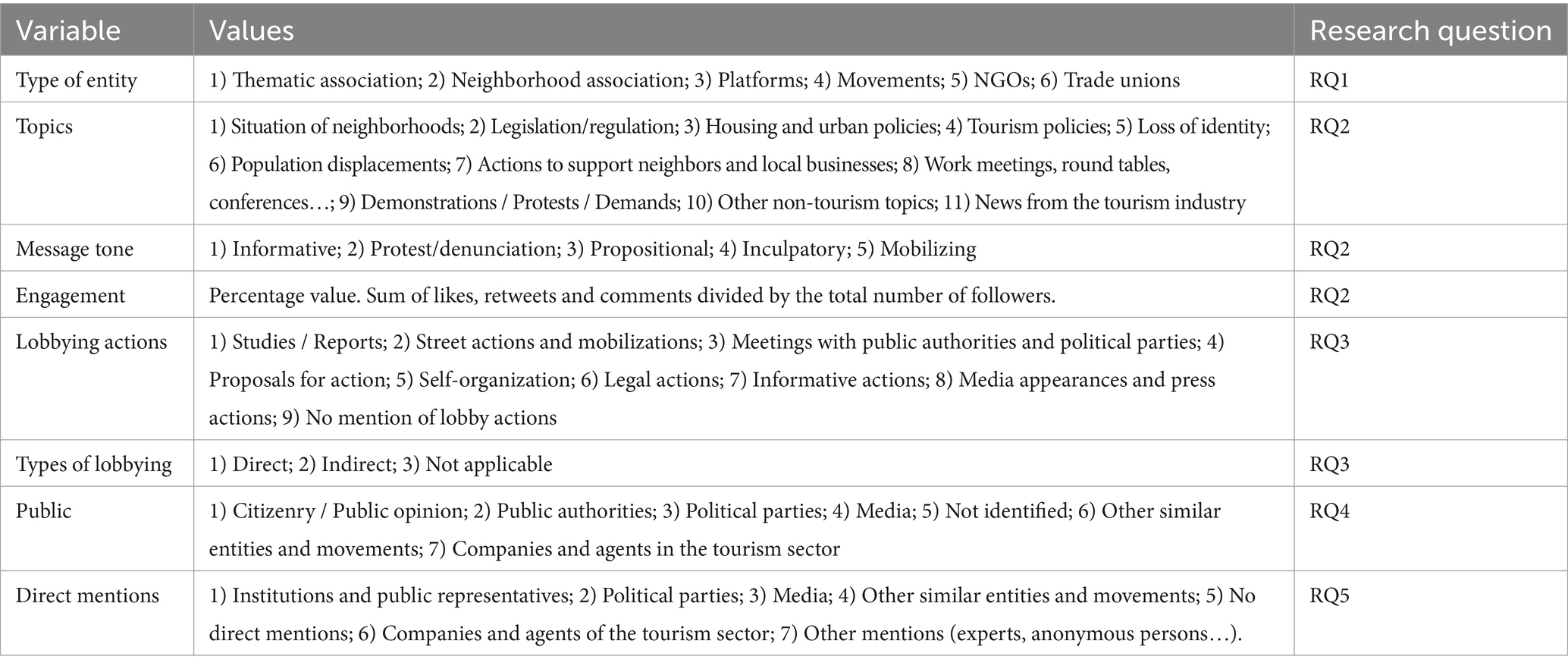

The variables used in the content analysis were related to the type of entity (thematic association, neighborhood association, platforms, movements, NGOs and unions), the topics covered in the publications (neighborhood situation; legislation and regulation; housing and urban policies; tourism policies; loss of identity; population displacement; actions to support neighbors and local businesses; work meetings, round tables and conferences; demonstrations, protests and demands in the street; news from the tourism sector; and other non-tourism-related topics), the tone of the message (informative, protest or denunciation, propositional, inculpatory and mobilizing), engagement of the publications, the lobbying actions shown or mentioned in the messages (studies and reports, street actions and mobilizations, meetings with public authorities or political parties, proposals for action, self-organization actions, legal actions, informative actions, and statements in the media and media-focused actions), the type of lobbying carried out with these actions (direct or indirect), the public to which the message is preferably addressed (citizens or public opinion, public authorities, political parties, media, other similar entities and movements, companies and agents of the tourism sector), and the direct mentions of the public through the users of X (public institutions and representatives, political parties, media, other similar entities and movements, companies and agents of the tourism sector, other mentions such as experts or anonymous people). The analysis of all variables was only applied to tourism-related publications, while the rest were classified as other non-tourism-related topics. The summary of these variables in relation to the research questions can be seen in Table 1.

In order to ensure the reliability of the content analysis performed, 20% of the posts from the total sample (232 out of 1,160) were also coded by an external collaborator. These 232 publications were randomly selected using ChatGPT. Subsequently, Krippendorff’s Alpha was applied to the variables mentioned above, excluding non-categorical variables and those categorial variables that serve as identification, such as the name of the entity or its location, among others.

According to Goyanes and Piñeiro-Naval (2024), Krippendorff’s Alpha is considered, from a statistical point of view, the most suitable parameter to measure inter-coder reliability in a content analysis, since it can be used regardless of the number of coders, the type of variables (qualitative or quantitative), the sample size or the existence of missing values. The values obtained for this parameter were above 0.667 for all variables (Table 2), a figure that Krippendorff himself considers to be “the lower acceptable limit” (Goyanes and Piñeiro-Naval, 2024, p. 135), so the study is deemed consistent from the perspective of inter-coder agreement. The analysis of the variables was conducted using the SPSS software and Excel.

3 Results

The 15 selected entities were categorized as platforms (46.7%), neighborhood associations (20%), unions (20%), thematic association (6.7%) and movements (6.7%). A total of 1,160 publications from 15 entities were analyzed, from June 1, 2024 to August 31, 2024.

Most of the publications analyzed (71%) were related to tourism. In contrast, 28.9% referred to other topics not related to tourism (local festivities, evictions or housing problems not directly caused by touristification).

Within tourism-related publications (825), demonstrations, protests and claims were the main topic of the messages published, with 42.9% of the total, followed by tourism policies (22.4%); work meetings, round tables and conferences (9.3%); housing and urban policies (6.4%); news from the tourism sector (6.3%); legislation and regulation (5.9%); the situation of neighborhoods (5.0%); population displacement (1%); actions to support neighbors and local businesses (0.6%); and the loss of neighborhood identity (0.1%). The publications that obtained the highest average engagement were those related to the situation of neighborhoods (6.4%), actions in support of neighbors and local businesses (5.2%); demonstrations, protests and claims (4.8%); legislation and regulation of the tourism sector (3.3%) and population displacement (3.2%). In any case, engagement figures were generally low.

Among the messages focused specifically on tourism-related issues, 38.8% had a tone of protest or denunciation, while 28.8% were informative and 26.4% were mobilizing. The least used tones were those dedicated to making proposals (5.1%) and those blaming the situation on other agents (0.8%).

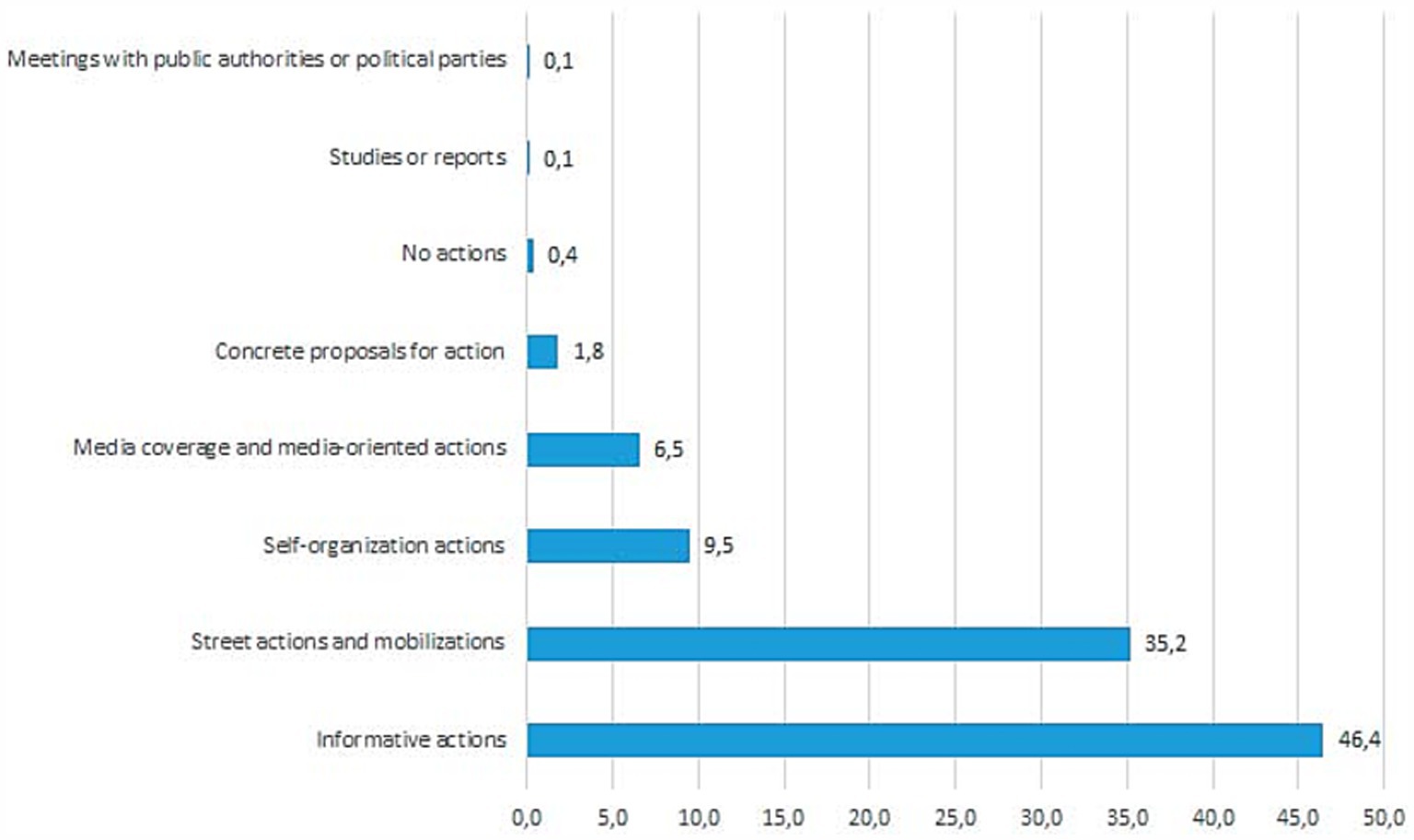

On the other hand, when analyzing the lobbying and communication actions indicated in the publications (Figure 1), it is observed that the most mentioned were informative actions (46.4%); followed by street actions and mobilizations (35.2%); self-organization actions, such as round tables or various meetings (9.5%); media coverage and media-oriented actions (6.5%); concrete proposals for action (1.8%); studies or reports (0.1%) and meetings with public authorities or political parties (0.1%). No topic was identified in 0.4% of the publications. It is also noteworthy that the actions shown through the different publications in the social network X mainly correspond to indirect lobbying (96.6%).

Figure 1. Lobbying actions in X publications of anti-touristification organizations (%). Source: the author.

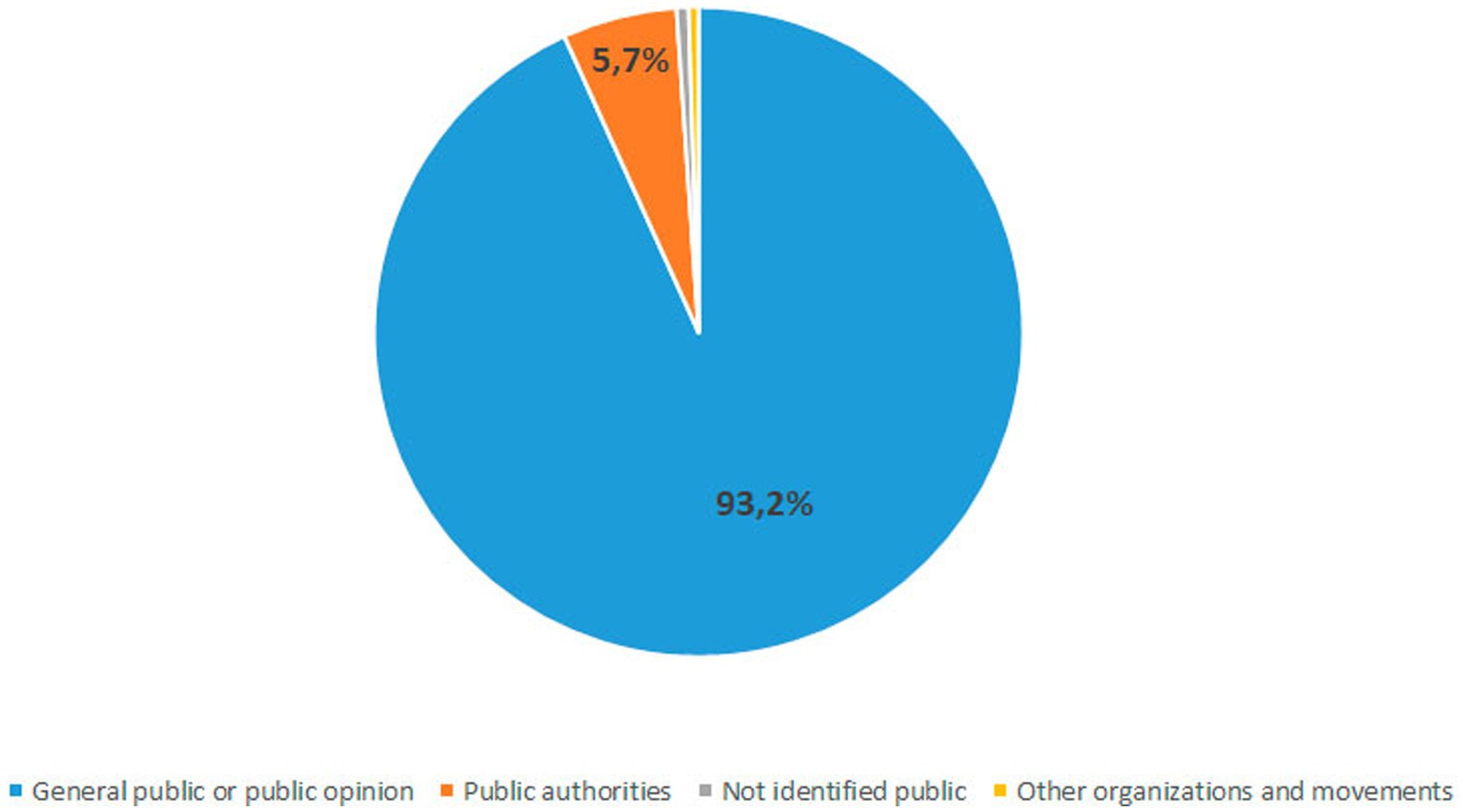

In fact, this type of indirect lobbying corresponds to the public to which the publications of organizations opposed to mass tourism were mainly directed, i.e., the general public or public opinion, representing 93.2% of the total (Figure 2), followed by the public authorities, whether institutions or individuals (5.7%) and, at a greater distance, other similar organizations and movements (0.5%). There were 0.6% of messages in which it was not possible to clearly identify the priority audience.

Finally, it should be noted that direct mentions using the @ symbol was not a resource widely used by the selected entities, as it only appeared in 51% of the publications; two mentions in 16.7%; and three mentions in 12.5%. Entities and movements similar to those studied were mentioned in at least 17.7% of the tweets, followed by the media (16.1%), other mentions of experts or anonymous people (9.5%), institutions or public representatives (6.5%), companies and entities in the tourism sector (0.7%) and political parties (0.5%).

4 Discussion

The aim of this research was to provide, in an exploratory way, a description of the online communication of citizen pressure groups against touristification and gentrification in Spain. For this purpose, a quantitative methodology was designed, based on the technique of content analysis, in order to make an approximation to the topics, forms and main target audiences of these groups’ messages in the social network X. The results show that, despite the multiple criticisms that it may receive, this platform is a suitable space for the communication of actions related to the mobilization against mass tourism and its negative consequences, such as its influence on housing prices or the saturation of public spaces, already pointed out by authors like Fioravanti (2022), Mansilla-López (2019a,b), and Zaar (2019).

In response to Research Question 1 (RQ1 – What type of pressure groups are there against touristification and gentrification?), the results of this research reveal that the entities that communicate against the phenomenon of touristification in the social network X are diverse in nature and call themselves by different names, such as platforms, neighborhood associations, unions, associations focused on specific issues and movements. This diversity partly explains why, despite being entities linked to the tourism sector and concerned about its effects on local populations, almost a third of the publications analyzed (28.9%) deal with issues not directly related to this sector. This implies that, from the perspective of a recipient specifically concerned about this phenomenon, there may be a certain dispersion of attention, since, along with their primary topic of interest, they will find other social causes that are also defended by these organizations. Consequently, certain support actions for residents, such as eviction prevention, could not be classified as messages related to the study’s focus, as they are not always explicitly linked to tourism. Precisely, the analysis has revealed that there are organizations whose main purpose is to expose the negative consequences of tourism saturation, but there are also others, with a much wider range of action, that have set themselves on tourism as one more battlefield of their social struggle, as they consider it a source of inequalities (Milano, 2018).

Although the topics addressed by the selected entities in their X publications are very diverse (RQ2 – What issues do these entities focus on and which ones generate the most interest among the public?), there is a significant predominance of those that show street actions, such as demonstrations and protests (42.9% of the total). This aligns with the tone employed in publications related to the phenomenon studied (protest or denunciation = 38.8% and mobilizing = 26.4%). However, it also carries the risk that the image of these organizations is associated with tourismphobia and their action is simplified to a mere positioning for or against tourism growth (Huete and Mantecón, 2018; Soliguer-Guix, 2023), making it impossible to gain a deeper understanding of the interests and arguments they advocate.

Tourism policies constitute the second most frequently addressed topic, appearing in 22.4% of the analyzed tweets and largely associated with an informational tone, which was present in 28.8% of the posts. Indeed, the studied entities sometimes share information about the tourism sector and the growth policies implemented in their territories by public administrations (Romero-Padilla et al., 2019), with the aim of criticizing government action and informing the public about consequences such as population displacement (Genç et al., 2022; Rodríguez-Barcón et al., 2021), who are forced to leave their neighborhoods due to the impossibility of coping with changes, mainly economic, aimed at meeting the demands of visitors (Calle-Vaquero, 2019).

It is noteworthy, however, that these topics are not the ones that generate the most engagement among the audience. On the contrary, greater interaction (likes, retweets, replies or comments) is observed in topics such as neighborhood conditions (6.4%) or actions supporting residents and local businesses (5.2%). This highlights the need of these organizations to, in addition to their mobilization and protest activity, deepen their communication strategy to raise awareness of the real consequences of touristification. Such strategies should not only focus on street mobilization and confrontation but also adopt a more informative and closer treatment to the people affected in their daily lives. In any case, engagement figures were generally low.

The analysis of the lobbying and communication techniques or actions employed by the anti-touristification organizations (RQ3 – What lobbying actions do they mention and what type of lobbying do they correspond to?) also reflects a notable difference from the topics addressed. While mobilization dominates the topics, the actions actually reflected have a high informative component (46.4%). This means they primarily aim to inform citizens and other publics with shared interests. Mobilizing actions appear in 35.2% of the publications and, although at a greater distance, self-organizing actions are also important (9.5%), such as meetings between different entities or preparatory tasks for upcoming demonstrations. Social networks become, therefore, a tool mainly oriented to indirect lobbying (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2022; Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024). In fact, this type of action is present in almost all the posts (96.6%). Virtually no examples of direct actions targeting public authorities (reports, meetings) were found in this study.

The indirect nature of these lobbying actions is also evident in the priority targets of the publications (RQ4 – Who is the target audience for the online messages of anti-tourism groups and movements; RQ5 – Which actors do they explicitly mention in their messages?), since the citizenry is the main target audience of most publications (93.2%).

This data suggests that the analyzed organizations, therefore, aim to achieve grassroots mobilization in its strictest sense, as they mainly use the X’s tagging feature (the @ symbol with a username) to mention other similar entities and movements (17.7% of the publications with a mention). In addition, media-oriented actions do not have a particularly significant presence (6.5%) and, when they are mentioned (16.1% of publications with a mention), it is done to share information published by them, as a way of giving credit of authorship rather than to establish a direct dialog with them.

This dialog does not take place with public authorities either, despite the fact that institutions and their representatives are the second public which messages are addressed (5.7% of the total) and are mentioned in 6.5% of them. Given the characteristics of X, which allows for almost entirely horizontal communication between users, one might expect a new form of direct lobbying adapted to the digital space: relations with the public authorities through social networks, but this does not occur, at least not publicly, since there is no evidence of the slightest debate or exchange of information. The mentions, on many occasions, are made as a form of criticism more oriented to let citizens know who are responsible for a particular situation than to a direct dialog with them.

Due to its exploratory nature, the main limitation of this research is the size of its sample, which prevents the results from being extrapolated universally. However, these findings do provide some initial insights for the application of communication and lobbying strategies by the organizations studied, as well as showing that, as with other types of organizations (Casero-Ripollés, 2015), social networks are a valid communicative resource for the lobbying work of pressure groups opposing mass tourism in the main cities of Spain, at least in its indirect form. Future research should consider working with larger samples and incorporating qualitative methodologies (interviews, focus groups) to deepen the understanding of the strategies and tools employed by these organizations. Additionally, the self-perception of these entities as pressure groups will be considered as a future line of research.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human data in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not required, for either participation in the study or for the publication of potentially/indirectly identifying information, in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The social media data was accessed and analyzed in accordance with the platform's terms of use and all relevant institutional/national regulations.

Author contributions

FJG-M: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The project 'Lobby y Comunicación en la Unión Europea. Análisis de sus estrategias de comunicación', funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain. National R+D+I Program. 2020. Project code: PID2020-118584RB-I00.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT 4o was used for random selection of the sample reviewed by the second coder.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Araya-López, A. (2021). A summer of phobias: media discourses on ‘radical’ acts of dissent against ‘mass tourism’ in Barcelona. Open Res. Europe 1:66. doi: 10.12688/openreseurope.13253.1

Barrero-Rescalvo, M. (2019). Algo se muere de las Setas a la Alameda. Efectos del turismo sobre la población y el patrimonio en el casco norte de Sevilla. Revista PH 98, 46–49. doi: 10.33349/2019.98.4432

Calle-Vaquero, M. (2019). Turistificación de centros urbanos: clarificando el debate. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles- BAGE 83, 1–40. doi: 10.21138/bage.2829

Casero-Ripollés, A. (2015). Estrategias y prácticas comunicativas del activismo político en las redes sociales en España. Historia y Comunicación Social - HICS 20, 533–548. doi: 10.5209/rev_HICS.2015.v20.n2.51399

Castillo-Esparcia, A., Almansa-Martínez, A., and Gonçalves, G. (2022). “Lobbies: the hidden side of digital politics” in Digital political communication strategies. Multidisciplinary reflections. ed. B. García-Orosa (Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan), 75–93.

Castillo-Esparcia, A., Smolak-Lozano, E., and Fernández-Souto, A. B. (2017). Lobby y comunicación en España. Análisis de su presencia en los diarios de referencia. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social - RLCS 72, 783–802. doi: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1192

Daza, M. (2024). Sevilla limita al fin los pisos turísticos y no dará más licencias en Triana y el Casco Antiguo. Available at: https://www.abc.es/sevilla/ciudad/sevilla-limita-fin-pisos-turisticos-dara-licencias-20241017105330-nts.html (Accessed October 17, 2024).

Fioravanti, H. (2022). La lucha contra la turistificación del centro histórico de Valencia: prácticas y narrativas de resistencia. Aust. Q. 38, 389–405. doi: 10.56247/qua.313

Genç, K., Türkay, O., and Ulema, Ş. (2022). Tourism gentrification: Barcelona and Venice. Turismo y Sociedad 31, 125–140. doi: 10.18601/01207555.n31.06

Gil, J., and Sequera, J. (2018). Expansión de la ciudad turística y nuevas resistencias. El caso de Airbnb en Madrid. Empiria. Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales 41, 15–32. doi: 10.5944/empiria.41.2018.22602

González, M. (2024). El turismo representa ya el 12,8% del PIB con casi 187.000 M de actividad. Hosteltur.. Available at: https://www.hosteltur.com/161263_el-turismo-representa-ya-el-128-del-pib-con-casi-187000-m-de-actividad.html (Accessed October 18, 2024).

González-Reverté, F., and Soliguer-Guix, A. (2024). The social construction of anti-tourism protest in tourist cities: a case study of Barcelona. Int. J. Tourism Cities - IJTC 10, 842–859. doi: 10.1108/IJTC-09-2022-0211

Goyanes, M., and Piñeiro-Naval, V. (2024). Análisis de contenido en SPSS y KALPHA: Procedimiento para un Análisis Cuantitativo Fiable con la Kappa de Cohen y el Alpha de Krippendorff. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico - ESMP 30, 125–142. doi: 10.5209/esmp.92732

Hernández-Cordero, A. (2021). Gentrificación y turistificación: origen común, efectos diferentes. Dimensiones Turísticas 5, 128–137. doi: 10.47557/KRUW8909

Huete, R., and Mantecón, A. (2018). El auge de la turismofobia, ¿hipótesis de investigación o ruido ideológico? Pasos. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 16, 9–19. doi: 10.25145/j.pasos.2018.16.001

Hughes, N. (2018). ‘Tourists go home’: anti-tourism industry protest in Barcelona. Soc. Mov. Stud. 17, 471–477. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2018.1468244

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2024). Encuesta de ocupación en alojamientos turísticos extrahoteleros. Julio 2024. Available at: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/es/EOAT0724.htm (Accessed September 3, 2024).

Mansilla-López, J. A. (2019a). The neighbourhood as a class front. Social movements and urban tourism in Poblenou, Barcelona. Revista Internacional de Sociología - RIS 77:e128. doi: 10.3989/ris.2019.77.2.17.144

Mansilla-López, J. A. (2019b). No es turismofobia, es lucha de clases. Políticas urbanas, malestar social y turismo en un barrio de Barcelona. Revista Nodo 13, 42–60. doi: 10.54104/nodo.v13n26.160

Milano, C. (2018). Overtourism, malestar social y turismofobia. Un debate controvertido. Pasos. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 18, 551–564. doi: 10.25145/j.pasos.2018.16.041

Milano, C., Novelli, M., and Russo, A. P. (2024). Anti-tourism activism and the inconvenient truths about mass tourism, touristification and overtourism. Tour. Geogr. 26, 1313–1337. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2024.2391388

Moreno-Cabanillas, A., Castillo-Esparcia, A., and Castillero-Ostio, E. (2024). Lobbying y medios de comunicación. Análisis de la cobertura periodística de los lobbies en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social - RLCS 82, 1–17. doi: 10.4185/RLCS-2024-2059

Petroman, I., Văduva, L., Marin, D., Sava, C., and Petroman, C. (2022). Overtourism: positive and negative impacts. Quaestus. Multidisciplinary Res. J. 20, 171–182.

Rodríguez-Barcón, A., Calo-García, E., and Otero-Enríquez, R. (2021). Una revisión crítica sobre el análisis de la gentrificación turística en España. Rotur, Revista de Ocio y Turismo 15, 1–21. doi: 10.17979/rotur.2021.15.1.7090

Romero-Padilla, Y., Cerezo-Medina, A., Navarro-Jurado, E., Romero-Martínez, J. M., and Guevera-Plaza, A. (2019). Conflicts in the tourist city from the perspective of local social movements. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles - BAGE 83, 1–35. doi: 10.21138/bage.2837

Soliguer-Guix, A. (2023). Turismofobia en Barcelona (2008-2019): exploración del asedio mediático y la protesta turística. Estudios Turísticos - ET 226, 53–76. doi: 10.61520/et.2262023.1217

Torres and Carrera (2024). Análisis de clima social. Informe Turismo II. Available at: https://torresycarrera.com/informe-clima-social-turismo-ii/ (Accessed October 18, 2024).

Keywords: gentrification, lobbying, online communication, pressure groups, social movements, touristification

Citation: Godoy-Martín FJ (2025) Online communication of citizen pressure groups in the face of the phenomenon of touristification in Spain. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1520933. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1520933

Edited by:

Álvaro Serna-Ortega, University of Malaga, SpainReviewed by:

Elizabet Castillero-Ostio, University of Malaga, SpainVanessa Roger-Monzó, University of Valencia, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Godoy-Martín. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Francisco Javier Godoy-Martín, ZnJhbmNpc2NvamF2aWVyLmdvZG95QHVjYS5lcw==

Francisco Javier Godoy-Martín

Francisco Javier Godoy-Martín