94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Polit. Sci., 22 January 2025

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2025.1511918

This article is part of the Research TopicRelations and Policymaking across EU Actors, National Governments, Parliaments and PartiesView all 3 articles

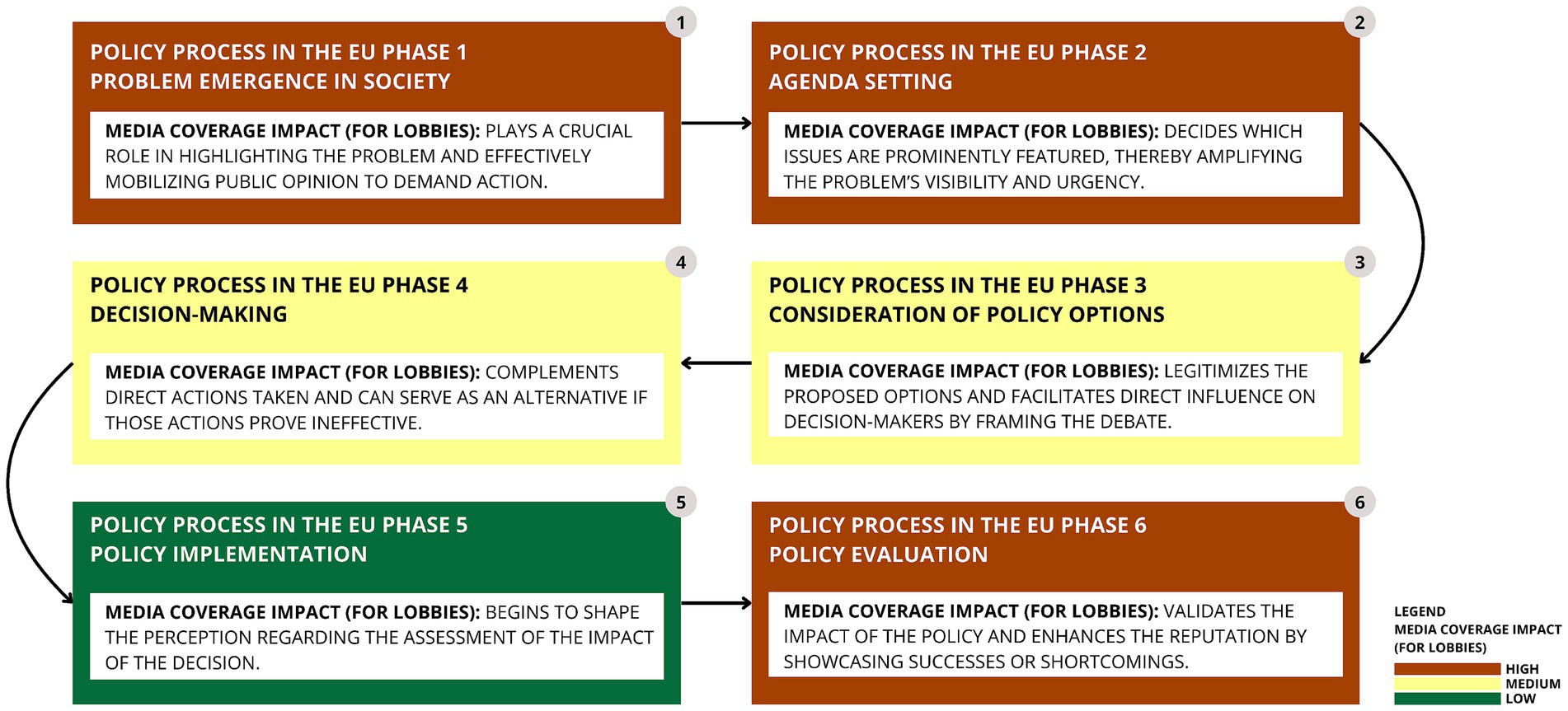

The influence of lobbies in the European Union is a complex phenomenon that must be analyzed through various direct and indirect conditioning dimensions. This theoretical research examines the impact of pressure groups at each of the six stages of the public policy formulation process in the supranational entity: problem emergence in society, agenda setting, consideration of policy options, decision-making, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. The study reveals how the influence of lobbies fluctuates depending on the point in the process and the type of interests they represent. Lobbies with social interests tend to have an advantage in phases involving public engagement, using grassroots lobbying strategies. On the other hand, economic lobbies dominate in phases that require contact with legislators, employing direct communication strategies. Among the direct conditioning dimensions, economic capacity–whether explicitly or implicitly−and access to decision-makers are crucial factors in determining the degree of influence. Additionally, in terms of indirect dimensions, media coverage is considered the most explanatory element regarding the influence capacity of lobbies, particularly at the initial and final stages of the governance cycle.

Since its creation, the European Union has gradually evolved into one of the most influential political-economic entities worldwide, with a significant role in global politics (Dinan, 2014; Lelieveldt and Princen, 2023). This evolution has increased the complexity of the decision-making process and underscored the need for informed and balanced public policy that takes into account the diversity of opinions, interests, and stakeholders involved (Buonanno and Nugent, 2020).

Pressure groups or lobbies occupy a prominent position in this common political space, representing a wide range of interests and exerting influence in numerous areas (Crombez, 2002; Dür and Mateo, 2012). The participation of lobbies in the European Union is a dynamic and evolving phenomenon, raising questions about the transparency, accountability, and ethical implications of their interactions with policymakers (Dinan, 2021). One explanatory factor for the priority position of lobbies operating in Europe stems from the decision-making system of the supranational entity, which is characterized by the involvement and convergence of multiple institutions and actors. This, together with other issues, enables pressure groups to capitalize on favorable circumstances to advance their agendas, i.e., to exert influence (Coen, 2007; Woll, 2006).

In this regard, it is important to consider that the influence of pressure groups depends on several factors. Nine conditioning dimensions stand out, which will be further developed in this article. The independent direct dimensions include financial strength (Chand, 2017; Stevens and De Bruycker, 2020), the ability to mobilize supporters (Klüver, 2013; Walker, 2012), the willingness to form coalitions (Grose et al., 2022; Hula, 1999), the alignment of the claims with dominant social norms (Ihlen and Raknes, 2020), and access to gatekeepers and authorities (Bouwen, 2002; Serna-Ortega et al., 2024). The dependent direct dimensions involve the stage of the policymaking process in which influence is sought and the communication strategies employed (De Bruycker and Beyers, 2019). Additionally, the indirect conditioning dimensions refer to media coverage (Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024) and public perception of the organization (Kollman, 1998).

This theoretical research is based on the general objective (GO) of analyzing the influence capacity of pressure groups at the different phases of the European Union’s public policy formulation process: emergence of the problem in society, agenda setting, consideration of policy options, decision-making, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. That is, it seeks to delve into one of the two dependent direct conditioning dimensions mentioned.

Derived from this general objective, three specific objectives are outlined. The first (SO1) aims to explore the differences in influence capacity across the phases based on the organizational nature of the lobby and the interests it defends. The second specific objective (SO2) seeks to study the interdependencies and interrelations that the analysis presents with the other independent direct and indirect conditioning dimensions. The last specific objective (SO3) aims to examine the communication strategies most commonly employed by lobbies throughout the various phases of the process.

In this way, the contribution of this article to the literature is threefold. First, it offers a clearer understanding of how the influence capacity of pressure groups changes across the various phases of the European Union’s policy process, a conditioning dimension that remains one of the least explored in the scientific literature. By analyzing it through the lens of organizational nature and the interests represented, the study offers new insights into the differentiated impact of various types of lobbies. Second, it analyzes the interplay between conditioning dimensions, highlighting how these factors interact with different stages of the policy process, and offering an integrative approach that transcends isolated analyses to provide a comprehensive perspective. Thirdly, the research explores the role of communication strategies across different phases, identifying which tactics are most effective in each stage. This analysis is useful for both scholars and practitioners, as it bridges the gap between theory and practice.

One of the aspects that most underscores the relevance of this study is its international focus. It is evident that the policy process in the European Union shares similarities with those of its member states (van et al., 2024; Buonanno and Nugent, 2020; Chari and Heywood, 2009). Both systems operate through multilevel governance, stakeholder participation, and consensus-driven decision-making. They also follow analogous stages, prioritizing transparency, accountability, and public communication to maintain legitimacy and inclusiveness. However, the supranational framework is notably more complex due to the diversity of actors, overlapping jurisdictions, and competing interests it must balance (Ackrill et al., 2013). This added complexity makes the European Union a valuable case for studying lobbying, as it offers pressure groups a broader range of access points. Closely related to this, it must be considered that the European Union’s decision-making processes extend beyond its borders (Bradford, 2020), influencing global economic and political dynamics, making the examination of lobbying at the supranational level crucial for understanding its impact and strategic importance.

Subsequently, considering the significance of the European context in lobbying practices and the growing public scrutiny and political debates surrounding the role of lobbying in democratic systems (Barron and Skountridaki, 2022; Crepaz, 2021), studying how pressure groups operate has become more crucial than ever. In this regard, this research contributes to the ongoing dialogue on ensuring that lobbying practices align with democratic values and serve the public interest, while also enhancing the understanding of political advocacy by all the actors involved in the process.

To achieve the proposed objectives, a structure divided into three parts is established. The first part explores the nine conditioning dimensions that shape the influence capacity of lobbies, as understanding these dimensions is necessary for effectively analyzing their implications across the different phases of the policy process. In the second part, the bulk of the theoretical review on the influence capacity of lobbies during the various stages of the European policy formulation process is developed, using a phase-specific structure. The content in each phase is organized systematically according to the specific objectives −except for the last phase, whose particularities require a description starting from communication strategies and concluding with the differences between types of lobbies. The third part, corresponding to the discussion, presents a general comparative analysis of the phases, examines the overall connections with the other dimensions, suggests possible future lines of research on the topic, and develops the implications and applications of the findings in the political, media, and social spheres.

In practical terms, this research primarily relies on a bibliographic analysis of existing literature. The framework is grounded in political science, communication theory, and institutional analysis. It involves systematically reviewing and synthesizing academic studies to identify and establish conceptual relationships among the various elements under investigation. Comparative analyses of perspectives, theoretical mappings, and syntheses using figures and tables are employed. All these methods are aimed at providing an integrative proposal that examines the subject of study in the most representative way possible.

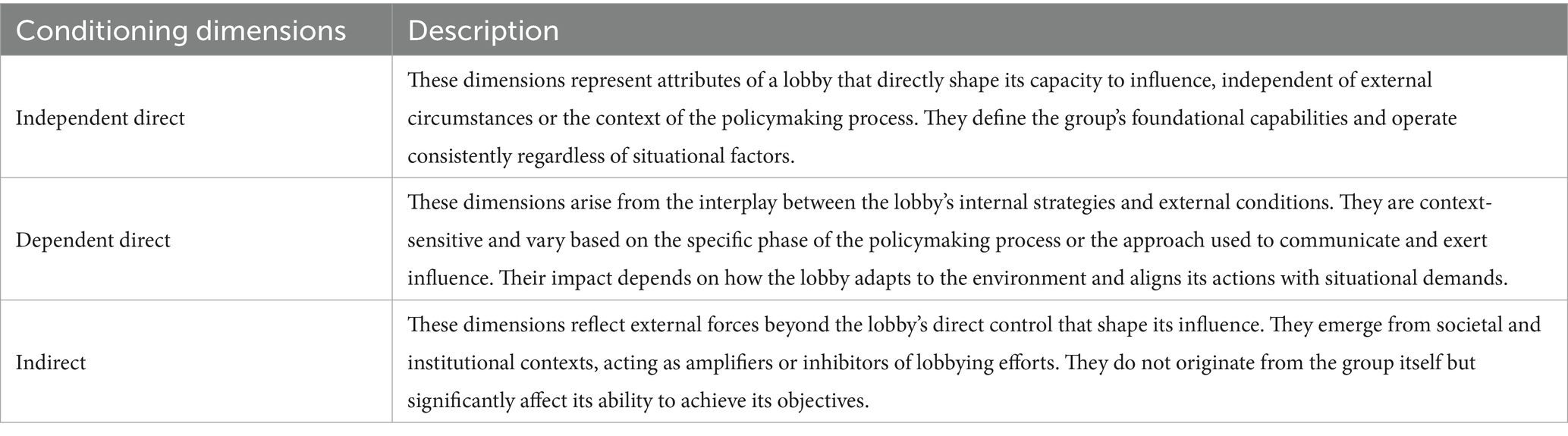

The research approach first requires identifying and understanding the conditioning dimensions that shape lobbies’ capacity to exert influence in the European context. As mentioned, these dimensions are grouped into three categories, depending on whether the conditioning they exert is direct or indirect and whether they are dependent or independent of particular scenarios or strategical proposals. Table 1 describes the type of conditioning exerted by the dimensions within the three categories of conditioning.

Table 1. Description of the conditioning exerted by the three categories of conditioning dimensions on the influence capacity of lobbies in the European Union policy process.

First, there are the independent direct conditioning dimensions, of which five main ones have been identified. The most evident is financial strength, which decisively determines the entity’s ability to act–either directly or through the corporate and business bias already embedded in the status quo, which ensures that wealth and influence are structurally advantaged−(Almansa-Martínez et al., 2022; Baumgartner et al., 2009; Hernández Vigueras, 2013; Stevens and De Bruycker, 2020; Woll, 2019). Another crucial factor is the ability to mobilize supporters, both in person and online, as well as the willingness to form coalitions to increase collective influence (Bernhagen and Trani, 2012; Grose et al., 2022; Klüver, 2013; Walker, 2012). Simultaneously, the alignment of the group’s initiatives with dominant social norms is relevant (Ihlen and Raknes, 2020; Scott, 2014), as those that meet this condition are more likely to succeed and reinforce the organization’s reputation. Lastly, the identification of gatekeepers and access to authorities are also essential for adjusting strategies and achieving effective influence (Bouwen, 2002; Serna-Ortega et al., 2024). In some cases, lobbies themselves may act as gatekeepers (Hirsch et al., 2023). From the perspective of scientific research in the European Union, economic capacity and access to authorities are aspects that can be objectively assessed due to the information available in the European Union Transparency Register. In contrast, the ability to mobilize supporters, the willingness to form coalitions, and the alignment of demands with predominant social values involve a greater degree of subjectivity.

As mentioned in Table 1, these five dimensions operate independently, meaning their influence is not tied to any specific stage of the policymaking process or the communication strategies employed by lobbies to achieve their objectives. In fact, these two issues constitute the two dependent direct conditioning dimensions, as, despite being internal to the organization, the course of action also depends on other external elements.

The stage of the public policy formulation process in which influence is sought is undoubtedly an aspect that determines the level of potential impact. Each phase requires the adaptation of action strategies. This is the dimension on which this research is focused. The phases used in the article are those proposed by Jordan and Adelle (2012), who study the phenomenon in the European Union and identify six sequential stages: emergence of the problem in society, agenda setting, consideration of policy options, decision-making, policy implementation, and policy evaluation.

With respect to the communication strategies used by pressure groups, their fundamental character in the effectiveness of operational approaches is highlighted (De Bruycker and Beyers, 2019; McGrath, 2007; Mykkänen and Ikonen, 2019). These strategies can be direct, targeting decision-makers through contacts and participation in legislative exercises (Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024; Palau and Forgas, 2010), or indirect, known as grassroots lobbying, which seeks to create a favorable public opinion climate through media and citizen mobilization (Bergan, 2009; Walker, 2009). They can also be classified by duration: long-term strategies, medium-term, or specific, depending on the objective and context (Correa Ríos, 2019; Martins Lampreia, 2006).

Beyond the seven direct conditioning dimensions−internal to the lobby−there are two indirect dimensions that help explain the differences in the influence capacity of pressure groups through aspects ultimately beyond the control of the organizations−external to the lobby.

On one hand, there is media coverage, which plays a key role in the influence process by giving political weight to claims and acting as an amplifier between pressure groups, citizens, and governments (De Bruycker and Beyers, 2015; Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024; Sobbrio, 2011). In theory, the media operates under a principle of independence, which means they may reflect the interests of pressure groups as a result of indirect lobbying strategies or through spontaneous coverage. Regardless of the reason for publication, for lobbies, it is necessary that this visibility is both positive and consistent, as the goal is not merely to achieve visibility but to use it to contribute to the group’s objectives (Mykkänen and Ikonen, 2019; Castillo, 2011).

On the other hand, there is public perception (Kollman, 1998). A positive image strengthens the legitimacy of the lobby’s demands and fosters additional support through citizen mobilization and media coverage. In contrast, a negative perception can hinder the persuasion of policymakers, who prefer to avoid controversies and align themselves with dominant public opinion (Lax and Phillips, 2012).

The summary of the direct and indirect conditioning dimensions that affect the influence capacity of lobbies in the European Union’s policy formulation process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conditioning dimensions on the influence capacity of lobbies in the European Union policy process.

The identified dimensions will serve as analytical lenses to assess the influence capacity of lobbies throughout the policymaking process. Analyzing the operation and interplay of each dimension enables a detailed mapping of their role in shaping lobbying strategies and outcomes. This approach facilitates the establishment of connections between the bibliographic analysis and the research objectives.

Also, aside from these nine elements, explaining the influence capacity of pressure groups requires considering two defining characteristics of these entities: the nature of the organization and the interests it represents. Although these issues, being intrinsic to the group, are not conditioning factors in themselves, they must be mentioned as they serve as primary references when making comparisons and differentiations based on potential influence.

After presenting the conditioning dimensions of lobbies’ influence capacity, the research proceeds to develop the phase-specific analysis across the six stages of the policy process. In each phase, the differences in the influence potential of various lobbies are explored, the interdependencies with the independent direct and indirect conditioning dimensions are studied, and the most common communication strategies used are examined.

The interdependencies between dimensions represent the most complex element. To facilitate their understanding, Table 2 presents a summary of the interdependencies of each dimension across the phases of the public policy formulation process.

Table 2. Summary of the conditioning of independent direct and indirect dimensions across the six phases of the European Union policy process established by Jordan and Adelle (2012).

According to the stages of the public policy formulation process in the European Union established by Jordan and Adelle (2012), the first phase involves the emergence of the problem in society, referring to societal issues that require public attention and political action. During it, the intervention of pressure groups must focus on issues of social relevance, as the ultimate goal of their efforts is to create public awareness that a particular phenomenon requires attention and intervention from policymakers. This implies that, beyond the type of lobby, what truly distinguishes the groups operating at this point is the alignment of their interests with issues that affect the public (Grose et al., 2022; Ihlen and Raknes, 2020; Lax and Phillips, 2012). In this sense, it is evident that organizations with a predominantly social orientation, such as NGOs, tend to be more active during this stage. However, lobbies with a more private benefit-oriented operational focus should not be excluded. In some cases, these groups may have objectives that align with social concerns (Kaplan et al., 2022), as is the case with environmental issues, where protecting the environment can benefit both public and private interests, with globalization being a trigger in this matter (Genc, 2023).

Regarding the interdependencies and interrelations with other dimensions, the key factor for influencing the emergence of the problem in society is the ability to mobilize supporters. In today’s digital age, the mobilization is not limited to the traditional concept but extends online through social media campaigns, digital petitions, and the creation of viral content (Gorostiza-Cerviño et al., 2023; Grose et al., 2022; Holyoke, 2020). This ability is important because, when a demand manages to generate public awareness, it amplifies the voice of the lobby and exerts pressure on policymakers and the media, causing them to recognize the issue as an emerging concern (Böhler et al., 2022; Rasmussen et al., 2018; Yates, 2023). On certain occasions, if the group believes its demand has sufficient social support but lacks the necessary mobilization capacity, it may seek coalitions. Generally, these coalitions tend to be issue-specific (Klüver, 2013).

Clearly, the capacity for mobilization is influenced by the extent to which the entity’s supporters feel affected by the specific demand (Baumgartner and Leech, 2001), and by the degree to which the demand aligns with prevailing social values (Ihlen and Raknes, 2020). In this context, the media serves as an amplifier, increasing the visibility and significance of the issue both in society and within public discourse (Sobbrio, 2011). A positive public perception of the group helps mobilize supporters and generate media coverage; therefore, the history of interactions between the lobby and the public is also connected.

As a result, given that the primary targets of action are the public and the media, the communication strategies and actions employed by lobbies in this initial phase are primarily indirect (Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024). The approaches tend to be long-term, with the goal of maintaining the visibility and relevance of the issue over time (Castillo, 2011; Martins Lampreia, 2006). This tactic, centered on grassroots lobbying and the sustained presence of the demands over time, allows society itself to act as a driving force (Klüver, 2013), pushing the various actors involved in the influence cycle to recognize and prioritize the issue during the agenda-setting stage.

Precisely, the establishment of the agenda setting constitutes the second phase in the public policy formulation process in the European Union, according to Jordan and Adelle (2012). This stage is closely linked to the previous one, to the extent that Kraft and Furlong (2015) propose merging them. It refers to the part of the process where the issue is already present in society, and in order for it to progress into the political sphere, it must gain visibility in the media, which adds a new dimension to the demands.

Thus, at this point, the focus shifts to the inclusion of the issue in the media, where it is decided which topics are highlighted and considered a priority in the public debate (Bonafont, 2024). The most complex aspect here is understanding the difference between media coverage aimed at raising awareness about the existence of a problem and the coverage that occurs once the problem has already been socially recognized. In this second stage, media presence shifts from merely highlighting the existence of the problem to ensuring that the issue is included in the agenda for discussion and analysis (Anastasiadis et al., 2018; Lorenz, 2020). Furthermore, in the previous phase, the aspiration for media visibility was a means to an end; in this case, media presence itself becomes the ultimate goal of the actions.

This conceptual difference leads to a distinctive pattern in the distribution and capabilities of pressure groups at influencing the agenda setting, compared to the previous stage. The main difference is that lobbies with private interests aim to have a larger proportion of their issues included in the media agenda, regardless of their relevance to social matters. This is because media presence also helps legitimize demands before decision-makers (Moreno-Cabanillas and Castillo-Esparcia, 2023; Tresch and Fischer, 2015). As a result, the willingness to act tends to be more equal from the perspective of aspirations, as all pressure groups, for various reasons, want their interests included in the media, leading to increased competition for media space. This accentuates differences based on available financial resources and consequently, lobbies with access to economic resources −typically those representing private interests−, gain a distinct competitive advantage. In contrast to this idea, Stevens and De Bruycker (2020) argue that organizations with high economic resources achieve higher effectiveness rates in outcomes by keeping their claims away from the media.

When examining structural differences based on the interests of the organizations, various models and theories have been developed to explain this phase of policy formulation (Dryzek and Dunleavy, 2009; Hill and Varone, 2021; Kraft and Furlong, 2015). One school of thought is pluralistic in its assumptions, believing that political power is broadly distributed in society, although unevenly. They assume that agenda setting is open and competitive, with the government acting as an honest mediator. In this view, lobbies are integrated into the system, and there are no remarkable inequalities within it. On the other hand, neo-pluralists are structuralists who argue that entities associated with private interests hold a privileged position compared to other groups. They believe the state is under powerful structural pressure to promote economic growth without considering the implications, taking an apocalyptic stance on the situation (Benson and Jordan, 2015).

Irrespective of the varying viewpoints, organizations’ ability to have their demands included in the media is affected by various explanatory dimensions concerning their potential to influence. Among these dimensions, alignment with prevailing social values and the public perception of the lobby can be considered the most important, after evaluating their overall influence throughout the cycle (Ihlen and Raknes, 2020; Kollman, 1998; Lax and Phillips, 2012). The way the public perceives a group can also alter the media’s willingness to cover its claims, creating a scenario of triangular interdependence. Lobbies that are viewed positively and considered legitimate are more likely to receive favorable and extensive coverage, while those with a negative perception may struggle to gain media attention (Kollman, 1998). The ability to mobilize supporters is clearly linked to the two conditioning dimensions mentioned. For example, by developing actions that involve a large number of supporters and have a high newsworthiness component.

The predominant communication strategies are indirect, as the ultimate influence is exerted on the media (Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024). In this regard, it is important to note that the communication strategy does not necessarily need to be directed at the media itself. In certain cases, creating actions with viral potential can yield better results in terms of media presence.

Once the issue has been socially recognized and becomes part of the media agenda, the third phase begins, which involves the consideration of the different policy options by decision-makers (Jordan and Adelle, 2012). In this phase, decision-makers come into play, and the process enters the political sphere. It marks an initial contact with the responsible authorities, where different possible courses of action regarding the issue are considered.

Studies on the variations in lobbying influence based on the nature of the organizations reveal that during this stage, business and professional groups typically enjoy privileged access to public officials compared to other types of groups, such as citizen groups (Binderkrantz et al., 2015; Dür and Mateo, 2013; Serna-Ortega et al., 2024). Such privileged access can largely be explained by the strategic position these entities occupy in the socioeconomic structure, as they often represent sectors crucial for economic growth and financial stability−clearly linked to the considerations of Baumgartner et al. (2009) regarding the tangential influence of economic resources. Therefore, entities with economic interests tend to have greater success in influencing the consideration of policy options (Klüver, 2012). Groups advocating for social interests do not have as much operational capacity, mainly because social support is not as relevant at this stage of the policy process.

As is evident, access to public authorities is the primary explanatory factor in determining lobbying influence at this point of the cycle (Serna-Ortega et al., 2024). Media coverage and public perception can also influence tangentially, in a complementary manner. Related to this is the fact that past interactions between lobbies and decision-makers contribute to establishing long-term, sustained relationships, which increase the likelihood of influence and enhance the receptiveness to lobbying claims (Hanegraaff et al., 2019). These considerations must be understood in light of the fact that access does not necessarily translate into effective influence (Fraussen and Halpin, 2018; Beyers and Braun, 2014).

In that line, although financial capacity is not considered a direct significant factor at this stage, differences in access to authorities can give it considerable collateral influence. This is due to the systemic pressure states face to favor economic development, as noted by several authors (Acemoglu et al., 2015; Benson and Jordan, 2015; Lin and Wang, 2017).

The communication strategies used are primarily direct or informational, as this is the fastest way to convey information to decision-makers (Awad, 2024; Chamberlain et al., 2023; De Bruycker and Beyers, 2019). Given the nature of the actions and the operational limitations of lobbies, they often focus their strategies on this phase. They benefit from the interconnectedness of political issues, as decision-makers seek solutions and certainties within a context of uncertainty and numerous internal and external constraints. This creates an information asymmetry between the state and pressure groups (Potters and Van Winden, 1992).

Opinions on this asymmetry in the scientific literature are diverse. For example, De Figueiredo and Richter (2014) argue that lobbies hold an advantageous position over legislators as a result of this asymmetry. However, Dahm and Porteiro (2008) suggest that it can be mitigated when policymakers have access to multiple information sources, which reduces the influence of any single pressure group. Taking it a step further, Schnakenberg (2017) finds that information asymmetry can sometimes benefit policymakers by allowing them to extract more information from competing pressure groups. There is no doubt, however, that this “informational currency” grants lobbies access and influence in the decision-making process (Bouwen, 2004).

After the consideration of policy options, the next step in the public policy formulation process in the European Union is the decision-making by the responsible authorities (Jordan and Adelle, 2012). In other words, after evaluating the different possible alternatives, the time has come to choose one of them. At this stage, the influence of pressure groups diminishes because once the options have been analyzed, opinions about them have already been established, and changing these opinions is a difficult task.

Regarding the differences between types of lobbies based on their nature or interests, the observed pattern largely depends on the dynamics established in the previous phase. In general, it can be stated that during the decision-making stage, the structural pressure on authorities to favor the economy (Benson and Jordan, 2015) gives a competitive advantage to organizations with private interests, with the need for the public presence of the claim (Binderkrantz et al., 2015; Dür and Mateo, 2013; Klüver, 2012; Stevens and De Bruycker, 2020).

Since this phase inevitably involves interaction with policymakers, access to them once again marks the primary explanatory dimension (Serna-Ortega et al., 2024). In this sense, it is also emphasized that entities typically do not concentrate their communication strategies solely at this stage. The most intense interactions with decision-makers should occur in the early moments of the legislative process, when policies are still being developed and alternatives have not yet been fully evaluated (Baumgartner et al., 2009).

The limited communication strategies employed by pressure groups still tend to be direct (Dellmuth and Tallberg, 2017), although to a lesser extent than during the consideration of policy options. The intensity of these actions depends on whether the anticipated decision supports the group’s interests or not. If the initial response from the decision-makers has been positive and the expected policy proposal aligns with the organization’s goals, the tendency is to maintain a low profile, trying to keep the situation as stable as possible. Supplemental specialized documentation may be provided to reinforce the already established position (Bouwen, 2004).

Conversely, if the initial response has been unfavorable, pressure groups often diversify their tactics. Since the first contact with policymakers is usually established during the examination of alternatives, lobbies can assess the effectiveness of their direct actions and propose adjustments or alternatives. In an adverse scenario, the use of indirect strategies, such as mobilizing public opinion or seeking media coverage (Binderkrantz et al., 2015; Klüver, 2013), is commonly increased as a last resort before the decision becomes irreversible. Another recurrent tactic is forming issue-specific coalitions with other organizations that share similar interests (Hula, 1999; Klüver, 2013; Mahoney, 2007).

The fifth stage of the public policy formulation process in the European Union corresponds to the implementation of the political decision (Jordan and Adelle, 2012). By this point, the legislative choice has already been made, and the focus is now on putting the policy into practice. This stage involves translating the policy into concrete steps, such as drafting regulations, allocating resources, or setting up programs that will have tangible effects on the public or target groups.

This is the least active phase for pressure groups in terms of exercising influence, as it is too late to alter the governmental decision and too early to shape public perception of its effects or consequences. This inactivity results in virtually no differences in influence capacity between groups with varying interests or natures, simply because no significant influence efforts are being made.

Communication strategies employed, one more time, depend on whether the final decision supports or opposes the group’s interests. If the decision is favorable, pressure groups may focus on collaborating directly with the authorities responsible for implementation to ensure that the interpretation and application of the regulations benefit their interests (Bennedsen and Feldmann, 2006). Then, it could be considered that there is a certain degree of interdependence with the dimension of identification and access to decision-makers, insofar as they are the same individuals responsible for implementing the policy. Contrarily, if the decision is unfavorable, this phase can be used to conduct an internal evaluation of the strategies employed throughout the cycle. Assessing the effectiveness of actions allows groups to optimize their resources and influence tactics based on the political conditions (Crepaz et al., 2023). Furthermore, a rigorous evidence-based evaluation enhances the group’s credibility and its impact on future actions (Baumgartner et al., 2009; Castillo, 2011).

Finally, after the decision has been implemented, the sixth and final stage of the process is the evaluation of impact and consequences of the policy (Jordan and Adelle, 2012). This evaluation involves the society, the pressure groups, and the decision-makers. During this phase, the emphasis is on determining whether the policy has met its intended objectives and evaluating the broader effects it has had on stakeholders. From the perspective of the lobby groups, efforts should focus on ensuring that both citizens and decision-makers perceive the impact of the decision as aligned with the interests they advocate. The cyclical nature of the public policy formulation process makes it important to conclude interactions with other involved parties in the best possible way, as this significantly impacts future relations and lobbying strategies due to the precedents set by these interactions (Grose et al., 2022; Hanegraaff et al., 2019).

Up to this point, communication strategies have been directed at citizens and the media–grassroots or indirect lobbying−or on direct contact with decision-makers–direct or informational lobbying. The main feature of this phase is the need to simultaneously develop both lines of action. For that purpose, media coverage represents one of the most interdependent dimensions. Through the media, it is possible to convey the organization’s perspective on the issue to the public while also exerting influence on the public officials (Castillo, 2011; De Bruycker and Beyers, 2015; Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024; Mykkänen and Ikonen, 2019).

It could be said that this need to develop multiple strategies gives an advantage to groups with greater financial resources (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2023), such as companies and industrial lobbies advocating for private and economic interests. However, it is also true that socially oriented groups with strong supporter mobilization capacity have a better position in terms of public opinion or social support (Kollman, 1998; Rasmussen et al., 2018), which can strengthen their influence at this stage. Both viewpoints are valid. In fact, during policy evaluation, it is not the group’s nature or its interests that matter, as almost all positions have valid arguments. The key distinguishing factor lies in those lobbies that have formulated their strategies based on objective information, rather than information biased by their own interests (Almansa-Martínez et al., 2022). These groups are better positioned to defend their stance with greater credibility and knowledge to both the public and legislators (Barron and Skountridaki, 2022; McGrath, 2006). The degree of specialization of the entity in relation to the cause can also facilitate the presentation of detailed information that aligns with their objectives (Hanegraaff et al., 2019). It should be noted that the courses of action vary significantly depending on specific contexts.

On the other hand, if it was not done earlier, an analysis of the communication actions executed should be carried out, taking the opportunity to evaluate their effectiveness (De Bruycker and Beyers, 2015). The exploration should include an analysis of how the interactions were perceived, the effectiveness of the messages conveyed, and the impact of the proposal in the general context. The importance lies in the ability to adjust future strategies based on observed results and obtained conclusions (Burstein and Linton, 2002; Lowery, 2013).

In essence, this phase should be conceived differently from the rest, as the goal is not to exert direct or indirect influence. Instead, the priority is to ensure that all parties with whom the organization has interacted perceive the interactions as honest (McGrath, 2006) and that the group’s proposal is ultimately considered a legitimate, coherent, and valid option, regardless of whether it was the adopted alternative or not. This approach involves aiming to create a solid and trustworthy public perception and reputation, fostering the willingness of other actors to maintain constructive relationships and consider the group as a valid actor in the future (Hanegraaff et al., 2019; Schepers, 2010). Although, in theory, these relationships should be built with decision-makers and the public; in practice, more efforts are directed toward public officials, creating a “market of relationships” (Groll and McKinley, 2015).

The public policy formulation process in the European Union, following the six stages defined by Jordan and Adelle (2012), demonstrates a progressive inclusion of actors: it begins with civil society, moves through the media, and ultimately involves the decision-makers. Analyzing the influence capacity of lobbies depending on their organizational nature or the interests they represent was outlined in SO1. In this regard, following the analysis, it is emphasized that this variation is strongly conditioned by this order of inclusion of actors. In phases involving public engagement, groups with social interests, occupy a prominent position (Grose et al., 2022). When the media comes into play, a dual scenario emerges: if media influence targets the public, social lobbies gain the upper hand, whereas influence directed at decision-makers tends to favor economic groups (Baumgartner and Leech, 2001; Lowery and Gray, 2004; Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024). Finally, phases requiring direct interaction with legislators consistently benefit organizations with economic interests (Binderkrantz et al., 2015; Dür and Mateo, 2013; Klüver, 2012; Serna-Ortega et al., 2024).

However, these differences are beginning to blur, as economic and social groups increasingly converge on issues like the environment, driven by globalization’s push toward a more collectivist approach to problem-solving (Genc, 2023). This convergence phenomenon is being studied as it could mark a turning point in the dynamics of interactions between citizens, lobbies, and the state. Researchers indicate that, in recent years, these interactions have changed due to the sophistication and increasing complexity of lobbying actions, which sometimes surpass the regulatory procedures they attempt to influence (Coen et al., 2024). This field of analysis undoubtedly opens a promising avenue for future research, exploring the causes and effects of this potential merging of interests.

Complementary to the organization’s interests, variations in influence potential all over the policy cycle are largely marked by the relationships with independent direct and indirect conditioning dimensions. SO2 of this study aimed to explore this issue.

Regarding independent direct conditioning dimensions, the first notable element is the economic capacity of the pressure group (Stevens and De Bruycker, 2020). Economic resources have a general connection, especially when multiple lines of action need to be developed or when strategies require a serious investment for implementation (Castillo-Esparcia et al., 2023). Moreover, this economic capacity acts as a collateral conditioning factor in stages involving legislators, who face structural pressure to favor economic development through the private market (Benson and Jordan, 2015; Halkos and Trigoni, 2010; Lelieveldt and Princen, 2023). As a result, the influence of economic advantage should be evaluated through its diverse nature, considering the systemic advantage it represents and the ongoing debate in the scholarly literature regarding its connection to success, either directly or tangentially (Baumgartner et al., 2009; Chand, 2017; Stevens and De Bruycker, 2020; Woll, 2019).

In the phases involving interactions with decision-makers, a close relationship is also observed with the dimension of the ability to identify and access these authorities. Therefore, the scenario is very similar in the two objective direct conditioning dimensions.

In relation to this second dimension, while access does not always guarantee effective influence, as it depends on various contextual factors (Fraussen and Halpin, 2018; Beyers and Braun, 2014), it undoubtedly offers a strategic advantage (Castillo, 2011; Serna-Ortega et al., 2024), especially when informational asymmetry occurs (Bouwen, 2004; Potters and Van Winden, 1992). The ability to engage directly with decision-makers allows pressure groups to present their arguments more persuasively and to shape policy discussions in their favor, thereby enhancing their potential to influence the outcome (Hanegraaff et al., 2019; Hirsch et al., 2023). In this context, it is worth noting that in the European Union, the Transparency Register has been in operation for over a decade as a tool to monitor interactions between pressure groups and institutional officials, thus promoting transparency in these processes (Greenwood and Dreger, 2013; Năstase and Muurmans, 2020). Future research could further explore the need to promote ethical and transparent lobbying practices and the development of strategies to foster a regulatory environment that encourages responsibility and accountability.

With respect to the subjective direct explanatory dimensions, such as the capacity to mobilize supporters or alignment with prevailing social norms, there is a strong interdependence with phases involving the society and the media. From the societal perspective, the power of visibility in bringing an issue to the forefront is evident, making social support extremely relevant (Grose et al., 2022; Rasmussen et al., 2018; Walker, 2009). Additionally, for example, in the agenda setting stage, these subjective factors have a high impact (Klüver, 2013; Ihlen and Raknes, 2020). The visibility and social support that these groups can gain partially determine the process of issue prioritization, reinforcing the importance of the relationship between mobilization, public perception, and agenda setting.

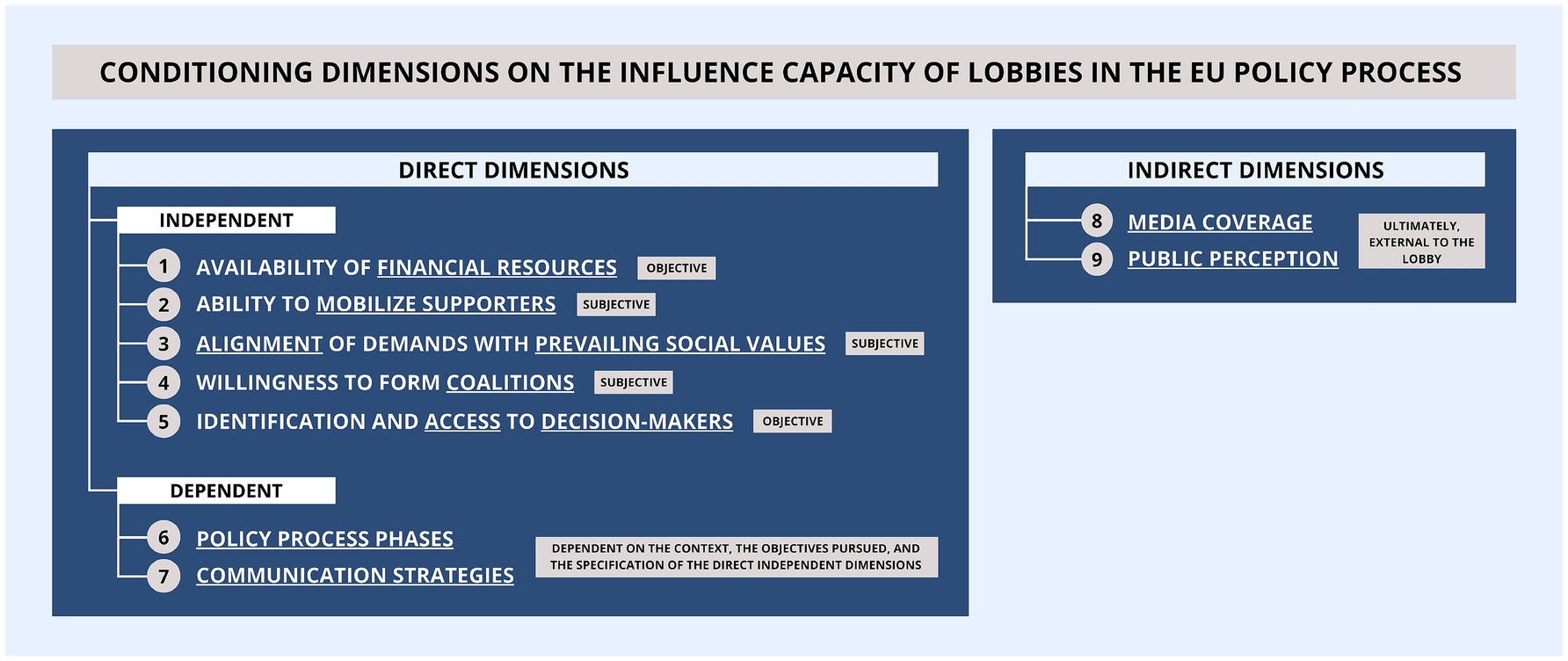

Closely related, when examining indirect or tangential conditioning dimensions, media coverage stands out as a crucial factor (Castillo, 2011; Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024). Its relevance is particularly noticeable in the first two phases, where media acts as amplifiers of demands, granting them social presence and political dimension (De Bruycker and Beyers, 2015; Sobbrio, 2011). In fact, in the agenda setting period, media coverage is the primary objective of lobbying communication strategies. Besides these two stages, in the final phase of policy evaluation, media presence plays an important role in helping to diversify lines of action, as at this point, its potential for application and influence involves all the actors engaged in the process (Castillo, 2011; De Bruycker and Beyers, 2015; Mykkänen and Ikonen, 2019). A future research avenue could focus on analyzing which specific indirect lobbying strategies are most effective in ensuring that the demands of pressure groups receive media coverage.

Figure 2 illustrates the degree of media coverage conditioning in each of the six phases of the public policy formulation process in the European Union.

Figure 2. Impact of media coverage on lobbying influence across the six phases of the European Union policy process established by Jordan and Adelle (2012).

In the same line of analysis, the conditioning effect of public perception of the organization exerts a general influence throughout the entire policy cycle (Kollman, 1998), although not as much as public support (Rasmussen et al., 2018). It is a complex dimension of understanding, as it generally needs to be evaluated based on the organization’s previous interactions with the public and decision-makers (Hanegraaff et al., 2019). It significantly influences the impact a demand can have on society and the media coverage it receives. Similarly, the final phase of the policy process is highly interdependent with public perception, as it facilitates the closure and reorientation of interactions with the involved actors. This interdependence arises not from direct influence but from the importance of managing the group’s perception at that point. In this sense, evaluating actions is decisive. Burstein and Linton (2002) point out the difficulties it presents in the operational context of lobbies, but it is necessary for adjusting strategies and improving the public perception in the future (Lowery, 2013).

Regarding the predominant communication strategies across different phases, the analysis of which was proposed in SO3, a clear differentiation is observed between lobbies with economic interests, which tend to use direct strategies, and those with social interests, which prefer indirect strategies (Awad, 2024; Chamberlain et al., 2023; Moreno-Cabanillas et al., 2024; Mykkänen and Ikonen, 2019). The effectiveness of these strategies is highly variable (De Bruycker and Beyers, 2019). In stages involving interaction with the public and media, lobbies usually opt for grassroots lobbying strategies. In contrast, in stages requiring contact with decision-makers, direct strategies are more common, with indirect strategies relegated to a complementary role or as an alternative course of action in case the anticipated scenario proves unfavorable for the lobby’s interests. The only exception is the point of evaluating the political decision, where, as mentioned, all actors and communication strategies intersect.

Taking the above into account, this research has successfully achieved its GO of analyzing the influence capacity of pressure groups in the different phases of the European Union’s public policy formulation process. The findings have important implications and potential practical applications. As mentioned in the introduction, the structural complexity of the supranational entity creates a conducive environment for the operational development of pressure groups. The analysis of their influence across different phases improves the understanding on the matter and deepens insights into the transformations in lobbying dynamics. Policymakers can use these findings to design regulations and frameworks that promote transparency and accountability in lobbying, ensuring that advocacy efforts do not disproportionately benefit specific interests. On the other hand, lobbyists can benefit from understanding how their strategies may need to adapt depending on the phase of the policy process they are targeting and the nature of the actors involved.

In terms of media implications, the study provides an educational and synthesizing perspective on how pressure groups interact with the media at different stages. In this way, the insights have the potential to assist journalists in developing more informed and balanced coverage of the interests at play. Similarly, the findings also contribute to the social understanding of the instrumentalization of social mobilization by lobbies; therefore, they serve as a tool for developing citizens’ critical analysis and fostering a more informed public debate.

ÁS-O: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AA-M: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AC-E: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by “Lobby y Comunicación en la Unión Europea” of the Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain), the State R + D + I Programme for Proofs of Concept of the State Programme for Societal Challenges, the State Programme for Scientific, Technical, and Innovation Research, 2020–2023 (PID2020-118584RB-100).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acemoglu, D., García-Jimeno, C., and Robinson, J. A. (2015). State capacity and economic development: a network approach. Am. Econ. Rev. 105, 2364–2409. doi: 10.1257/aer.20140044

Ackrill, R., Kay, A., and Zahariadis, N. (2013). Ambiguity, multiple streams, and EU policy. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 20, 871–887. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2013.781824

Anastasiadis, S., Moon, J., and Humphreys, M. (2018). Lobbying and the responsible firm: agenda-setting for a freshly conceptualized field. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 27, 207–221. doi: 10.1111/beer.12180

Awad, E. (2024). Understanding influence in informational lobbying. Interes. Groups Advocacy 13, 1–19. doi: 10.1057/s41309-023-00197-0

Barron, A., and Skountridaki, L. (2022). Toward a professions-based understanding of ethical and responsible lobbying. Bus. Soc. 61, 340–371. doi: 10.1177/0007650320975023

Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D. C., and Leech, B. L. (2009). Lobbying and policy change: Who wins, who loses, and why. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Baumgartner, F. R., and Leech, B. L. (2001). Interest niches and policy bandwagons: patterns of interest group involvement in national politics. J. Polit. 63, 1191–1213. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00106

Bennedsen, M., and Feldmann, S. E. (2006). Lobbying bureaucrats. Scand. J. Econ. 108, 643–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9442.2006.00473.x

Benson, D., and Jordan, A. (2015). “Environmental policy: protection and regulation” in International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences. ed. J. D. Wright (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier), 778–783.

Bergan, D. E. (2009). Does grassroots lobbying work? A field experiment measuring the effects of an e-mail lobbying campaign on legislative behavior. Am. Politics Res. 37, 327–352. doi: 10.1177/1532673x08326967

Bernhagen, P., and Trani, B. (2012). Interest group mobilization and lobbying patterns in Britain: a newspaper analysis. Interes. Groups Advocacy 1, 48–66. doi: 10.1057/iga.2012.2

Beyers, J., and Braun, C. (2014). Ties that count: explaining interest group access to policymakers. J. Publ. Policy 34, 93–121. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X13000263

Binderkrantz, A. S., Christiansen, P. M., and Pedersen, H. H. (2015). Interest group access to the bureaucracy, parliament, and the media. Governance 28, 95–112. doi: 10.1111/gove.12089

Böhler, H., Hanegraaff, M., and Schulze, K. (2022). Does climate advocacy matter? The importance of competing interest groups for national climate policies. Clim. Pol. 22, 961–975. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2022.2036089

Bonafont, L. C. (2024). “Agenda setting and interest groups” in Handbook on lobbying and public policy. eds. D. Coen and A. Katsaitis (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing), 92–104.

Bouwen, P. (2002). Corporate lobbying in the European Union: the logic of access. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 9, 365–390. doi: 10.1080/13501760210138796

Bouwen, P. (2004). Exchanging access goods for access: a comparative study of business lobbying in the European Union institutions. Eur J Polit Res 43, 337–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00157.x

Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Buonanno, L., and Nugent, N. (2020). Policies and policy processes of the European Union. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Burstein, P., and Linton, A. (2002). The impact of political parties, interest groups, and social movement organizations on public policy: some recent evidence and theoretical concerns. Soc. Forces 81, 380–408. doi: 10.1353/sof.2003.0004

Castillo, A. (2011). Lobby y comunicación: El lobbying como estrategia comunicativa. Zamora: Comunicación Social.

Castillo-Esparcia, A., Moreno-Cabanillas, A., and Almansa-Martinez, A. (2023). Lobbyists in Spain: professional and academic profiles. Soc. Sci. 12:250. doi: 10.3390/socsci12040250

Chamberlain, A., Strickland, J., and Yanus, A. B. (2023). The rise of lobbying and interest groups in the states during the progressive era. Front. Polit. Sci. 5:1123332. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1123332

Chand, D. E. (2017). Lobbying and nonprofits: money and membership matter − but not for all. Soc. Sci. Q. 98, 1296–1312. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12386

Chari, R., and Heywood, P. M. (2009). Analysing the policy process in democratic Spain. West Eur. Polit. 32, 26–54. doi: 10.1080/01402380802509800

Coen, D. (2007). Empirical and theoretical studies in EU lobbying. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 14, 333–345. doi: 10.1080/13501760701243731

Coen, D., Katsaitis, A., and Vannoni, M. (2024). Regulating government affairs: integrating lobbying research and policy concerns. Reg. Gov. 18, 73–80. doi: 10.1111/rego.12515

Correa Ríos, E. (2019). Comunicación: lobby y asuntos públicos. Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Diseño y Comun. 33, 101–110. doi: 10.18682/cdc.vi33.1713

Crepaz, M. (2021). How parties and interest groups protect their ties: the case of lobbying laws. Reg. Gov. 15, 1370–1387. doi: 10.1111/rego.12308

Crepaz, M., Hanegraaff, M., and Junk, W. M. (2023). Is there a first mover advantage in lobbying? A comparative analysis of how the timing of mobilization affects the influence of interest groups in 10 polities. Comp. Pol. Stud. 56, 530–560. doi: 10.1177/00104140221109441

Crombez, C. (2002). Information, lobbying and the legislative process in the European Union. Eur. Union Politics 3, 7–32. doi: 10.1177/1465116502003001002

Dahm, M., and Porteiro, N. (2008). Informational lobbying under the shadow of political pressure. Soc. Choice Welf. 30, 531–559. doi: 10.1007/s00355-007-0264-x

De Bruycker, I., and Beyers, J. (2015). Balanced or biased? Interest groups and legislative lobbying in the European news media. Polit. Commun. 32, 453–474. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2014.958259

De Bruycker, I., and Beyers, J. (2019). Lobbying strategies and success: inside and outside lobbying in European Union legislative politics. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 11, 57–74. doi: 10.1017/s1755773918000218

De Figueiredo, J. M., and Richter, B. K. (2014). Advancing the empirical research on lobbying. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 17, 163–185. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-100711-135308

Dellmuth, L. M., and Tallberg, J. (2017). Advocacy strategies in global governance: inside versus outside lobbying. Polit. Stu. 65, 705–723. doi: 10.1177/0032321716684356

Dinan, W. (2021). Lobbying transparency: the limits of EU monitory democracy. Polit. Gov. 9, 237–247. doi: 10.17645/pag.v9i1.3936

Dryzek, J. S., and Dunleavy, P. (2009). Theories of the democratic state. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dür, A., and Mateo, G. (2012). Who lobbies the European Union? National interest groups in a multilevel polity. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 19, 969–987. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2012.672103

Dür, A., and Mateo, G. (2013). Gaining access or going public? Interest group strategies in five European countries. Eur J Polit Res 52, 660–686. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12012

Fraussen, B., and Halpin, D. (2018). How do interest groups legitimate their policy advocacy? Reconsidering linkage and internal democracy in times of digital disruption. Public Adm. 96, 23–35. doi: 10.1111/padm.12364

Genc, H. N. (2023). “Global issues within the scope of sustainable development in science education; global warming, air pollution and recycling” in Proceedings of international conference on academic studies in technology and education 2023. eds. S. M. Curle and M. T. Hebebci (Antalya: ARSTE Organization), 97–111.

Gorostiza-Cerviño, A., Serna-Ortega, Á., Moreno-Cabanillas, A., and Castillo-Esparcia, A. (2023). Navigating the digital sphere: exploring websites, social media, and representation costs—a European Union case study. Soc. Sci. 12:616. doi: 10.3390/socsci12110616

Greenwood, J., and Dreger, J. (2013). The transparency register: a European vanguard of strong lobby regulation? Interes. Groups Advocacy 2, 139–162. doi: 10.1057/iga.2013.3

Groll, T., and McKinley, M. (2015). Modern lobbying: a relationship market. CESifo DICE Report 13, 15–22.

Grose, C. R., Lopez, P., Sadhwani, S., and Yoshinaka, A. (2022). Social lobbying. J. Polit. 84, 367–382. doi: 10.1086/714923

Halkos, G. E., and Trigoni, M. K. (2010). Financial development and economic growth: evidence from the European Union. Manag. Financ. 36, 949–957. doi: 10.1108/03074351011081268

Hanegraaff, M., van der Ploeg, J., and Berkhout, J. (2019). Standing in a crowded room: exploring the relation between interest group system density and access to policymakers. Polit. Res. Q. 73, 51–64. doi: 10.1177/1065912919865938

Hernández Vigueras, J. (2013). Los lobbies financieros. Tentáculos del poder. Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual.

Hirsch, A. V., Kang, K., Montagnes, B. P., and You, H. Y. (2023). Lobbyists as gatekeepers: theory and evidence. J. Polit. 85, 731–748. doi: 10.1086/723026

Holyoke, T. T. (2020). Interest groups and lobbying: Pursuing political interests in America. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hula, K. W. (1999). Lobbying together: Interest group coalitions in legislative politics. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Ihlen, Ø., and Raknes, K. (2020). Appeals to 'the public interest': how public relations and lobbying create a social license to operate. Public Relat. Rev. 46:101976. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2020.101976

Jordan, A., and Adelle, C. (2012). Environmental policy in the EU: Actors, institutions and processes. London: Routledge.

Kaplan, R., Levy, D. L., Rehbein, K., and Richter, B. (2022). Does corporate lobbying benefit society? Rutgers Bus. Rev. 7, 166–192.

Klüver, H. (2012). Biasing politics? Interest group participation in EU policy-making. West Eur. Polit. 35, 1114–1133. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.706413

Klüver, H. (2013). Lobbying in the European Union: Interest groups, lobbying coalitions, and policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kollman, K. (1998). Outside lobbying: Public opinion and interest group strategies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kraft, M. E., and Furlong, S. R. (2015). Public policy. Politics, analysis and alternatives. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Lax, J. R., and Phillips, J. H. (2012). The democratic deficit in the states. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 148–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00537.x

Lelieveldt, H., and Princen, S. (2023). The politics of the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lin, J. Y., and Wang, X. (2017). The facilitating state and economic development: the role of the state in new structural economics. Man Econ. 4:20170013. doi: 10.1515/me-2017-0013

Lorenz, G. M. (2020). Prioritized interests: diverse lobbying coalitions and congressional committee agenda setting. J. Polit. 82, 225–240. doi: 10.1086/705744

Lowery, D. (2013). Lobbying influence: meaning, measurement and missing. Interes. Groups Advocacy 2, 1–26. doi: 10.1057/iga.2012.20

Lowery, D., and Gray, V. (2004). Bias in the heavenly chorus: interests in society and before government. J. Theor. Polit. 16, 5–29. doi: 10.1177/0951629804038900

Mahoney, C. (2007). Lobbying success in the United States and the European Union. J. Publ. Policy 27, 35–56. doi: 10.1017/s0143814x07000608

McGrath, C. (2006). The ideal lobbyist: personal characteristics of effective lobbyists. J. Commun. Manag. 10, 67–79. doi: 10.1108/13632540610646382

McGrath, C. (2007). Framing lobbying messages: defining and communicating political issues persuasively. J. Public Aff. 7, 269–280. doi: 10.1002/pa.267

Moreno-Cabanillas, A., and Castillo-Esparcia, A. (2023). The role of lobbies in the process of European construction. Rev. Int. Relaciones Púb. 13, 93–110. doi: 10.5783/revrrpp.v13i25.809

Moreno-Cabanillas, A., Castillo-Esparcia, A., and Castillero-Ostio, E. (2024). Lobbying y medios de comunicación. Análisis de la cobertura periodística de los lobbies en España. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 82, 1–17. doi: 10.4185/rlcs-2024-2059

Mykkänen, M., and Ikonen, P. (2019). Media strategies in lobbying process. A literature review on publications in 2000-2018. Acad. Int. Sci. J. 20, 34–50. doi: 10.7336/academicus.2019.20.03

Năstase, A., and Muurmans, C. (2020). Regulating lobbying activities in the European Union: a voluntary club perspective. Reg. Gov. 14, 238–255. doi: 10.1111/rego.12200

Palau, R., and Forgas, S. F. (2010). Lobbying directo: un análisis de las prácticas del sector hotelero con las instituciones políticas. Teoría y Praxis 6, 25–41. doi: 10.22403/uqroomx/typ08/02

Potters, J., and Van Winden, F. (1992). Lobbying and asymmetric information. Public Choice 74, 269–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00149180

Rasmussen, A., Mäder, L. K., and Reher, S. (2018). With a little help from the people? The role of public opinion in advocacy success. Comp. Pol. Stud. 51, 139–164. doi: 10.1177/0010414017695334

Almansa-Martínez, A., Moreno-Cabanillas, A., and Castillo-Esparcia, A. (2022). “Political communication in Europe. The role of the lobby and its communication strategies” in International Conference on Communication and Applied Technologies. eds. Á. Rocha, D. Barredo, P. López-López, and I. Puentes-Rivera (Singapore: Springer), 238–248.

Schepers, S. (2010). Business-government relations: beyond lobbying. Corporate Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 10, 475–483. doi: 10.1108/14720701011069696

Schnakenberg, K. E. (2017). Informational lobbying and legislative voting. Am. J. Poli. Sci. 61, 129–145. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12249

Scott, J. C. (2014). The social process of lobbying: Cooperation or collusion? New York, NY: Routledge.

Serna-Ortega, Á., Gorostiza-Cerviño, A., and Moreno-Cabanillas, A. (2024). Acceso de los grupos de interés al proceso de formulación de políticas en la UE basado en portfolios. Rev. Int. Relaciones Púb. 14, 133–148. doi: 10.5783/revrrpp.v14i28.879

Sobbrio, F. (2011). Indirect lobbying and media bias. Q. J. Polit. Sci. 6, 235–274. doi: 10.1561/100.00010087

Stevens, F., and De Bruycker, I. (2020). Influence, affluence and media salience: economic resources and lobbying influence in the European Union. Eur. Union Polit. 21, 728–750. doi: 10.1177/1465116520944572

Tresch, A., and Fischer, M. (2015). In search of political influence: outside lobbying behaviour and media coverage of social movements, interest groups and political parties in six Western European countries. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 36, 355–372. doi: 10.1177/0192512113505627

van, M., Rothmayr, C., and Schubert, K. (2024). “Germany, Public Policy in” in Encyclopedia of public policy. eds. M. Gerven, C. R. Allison, and K. Schubert (Cham: Springer), 1–9.

Walker, E. T. (2009). Privatizing participation: civic change and the organizational dynamics of grassroots lobbying firms. Am. Sociol. Rev. 74, 83–105. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400105

Walker, E. T. (2012). Putting a face on the issue: corporate stakeholder mobilization in professional grassroots lobbying campaigns. Bus. Soc. 51, 561–601. doi: 10.1177/0007650309350210

Woll, C. (2006). Lobbying in the European Union: from sui generis to a comparative perspective. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 13, 456–469. doi: 10.1080/13501760600560623

Keywords: lobbying, EU, policy process, pressure groups, influence, decision-making

Citation: Serna-Ortega &, Almansa-Martínez A and Castillo-Esparcia A (2025) Influence of lobbying in EU policy process phases. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1511918. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1511918

Received: 15 October 2024; Accepted: 07 January 2025;

Published: 22 January 2025.

Edited by:

Marco Improta, University of Siena, ItalyReviewed by:

Paolo Marzi, University of Siena, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Serna-Ortega, Almansa-Martínez and Castillo-Esparcia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Álvaro Serna-Ortega, YW1zb0B1bWEuZXM=; Ana Almansa-Martínez, YW5hYWxtYW5zYUB1bWEuZXM=; Antonio Castillo-Esparcia, YWNhc3RpbGxvZUB1bWEuZXM=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.