94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 28 February 2025

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2025.1502731

This article is part of the Research TopicPeace and Democracy: Views from the Global SouthView all 4 articles

This study examines Indigenous peace ontologies and epistemologies among Nigerian and Bolivian communities, specifically the Yoruba, Ukwu-Nzu, Ubang, and Aymara cultures, to explore peace conceptual transformations through colonial and historical experiences. Conceptual representations and knowledge production are shaped by power dynamics that mainly marginalize Indigenous epistemic experiences, often erasing or replacing traditional ways of knowing with dominant, typically colonial ideologies. Using a qualitative cross-cultural exploratory approach—including semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and observations—the study reveals peace conceptualizations rooted in cosmological, historical, communal, and ecological frameworks. The Yoruba perceive peace as equilibrium mediated by Òrìṣà and personal agency, while the Aymara understand peace through suma qamaña— “living well” in harmony with Pachamama. Both perspectives emphasize collective well-being, relational ethics, and historical resilience. The study also examines the influence of Islam on Yoruba peace semiotics by reconstructing pre-Islamic peace terms in Lukumi, a Yoruboid language of the Ukwu-Nzu people, and explores gendered linguistic variations in peace conceptualization through the Ubang culture, where men and women speak mutually unintelligible languages. By critiquing universalist assumptions, the study advocates for decolonial methodologies that integrate Indigenous epistemes into broader scholarly discourses, fostering inclusive and pluralistic understandings of peace.

Conceptual representations and knowledge production, akin to historical narratives, are profoundly shaped by power dynamics within hierarchical structures that marginalize and often disregard the epistemic experiences and cultural perspectives of marginalized groups. In post-colonial Indigenous communities, these imbalances extend beyond politics, infiltrating local epistemologies, knowledge representation, cultural values, and identities. Traditional ways of knowing are either erased or supplanted by the dominant ideologies of former colonizers (Held, 2019). This displacement reshapes Indigenous perspectives, marginalizing their cultural interpretations of the world to conform to external norms (Datta, 2018). Concepts such as peace and conflict, while often assumed universal, embody unique meanings within these peripheral communities, reflecting deeper ontological roots tied to their cultural and existential realities, which may not be adequately captured by the dominant understandings of these concepts.

Critical peace studies and decoloniality literature recognize this problem, and there are arguments for deconstructing the embedded universalism or intrinsic generalization associated with peace meanings (Jackson, 2015; Oswald Spring, 2021). However, these deconstructions do not often adequately accommodate excluded ontologies and epistemes of Indigenous communities whose worldviews are sometimes reduced to folklore and myths (Smith, 2021; Simonds and Christopher, 2013). When given a thought—often very rarely—their views are used either to corroborate established narratives or relegated to the periphery of the discourse.

This exclusion transcends peace studies, for it is emblematic of the uneven relations between colonial hegemonic influence and the vanquished epistemologies of the colonized people (Smith, 2021, p. 58–72). While the liberal peace framework has evolved in recent years within a more fluid international order, it remains an influential paradigm in peacebuilding practices, mainly through the frameworks of democracy promotion, market liberalization, and multilateral interventions (Levorato and Sguazzini, 2024). The persistence of liberal peace elements is tied to their institutional embeddedness within international organizations and state policies (Richmond, 2021). This context provides a foundation to contrast Indigenous peace epistemologies and situate them as part of a broader critique of universalist assumptions in global peace studies.

While discussing the implication of privileging Eurocentric knowledge over Afrocentric knowledge, Molefi Kete Asante describes how even African social scientists “reframe and reshape the Eurocentric model and project it as universal” (Asante, 2006). The abnormality of this assumption manifests when this model's cultural particularity is imposed as universal “while denying and degrading other cultural, political, or economic views” (Asante, 2006, p. 145). Asante further notes that the severity of this predilection to dispossessing Indigenous excluded cultures (in this case, African) is in the precarity of even local intellectuals using the “vantage point of Europe to write Africans of centrality, even without our [their] own historical context” (Asante, 2006). These Western Hemisphere (Western Europe and the United States) epistemologies and phenomenology are rooted in colonial experiences wherein certain inherited methodologies and theorization are considered standards for knowledge-making.

Nigeria and Bolivia share similarities in being historically shaped by colonial domination that disrupted their local knowledge systems and replaced them with hegemonic frameworks. Both countries exhibit a diverse array of Indigenous communities that have preserved unique understandings of peace despite these disruptions. For example, the Yoruba of Nigeria and the Aymara of Bolivia both conceptualize peace as deeply embedded in their relational and cosmological frameworks, diverging from universalist or Western-centric models. Moreover, both cases reflect broader trends within the Global South, where postcolonial societies wrestle with reclaiming and validating Indigenous epistemologies within global discourses and national contexts that often continue to privilege Western frameworks. The study's focus on these two cases (Nigeria and Bolivia) is a means to explore how Indigenous peace ontologies as a way of understanding these oft-neglected worldviews with a view to accommodate their contributions to the broader peace conceptualizations and operationalizations.

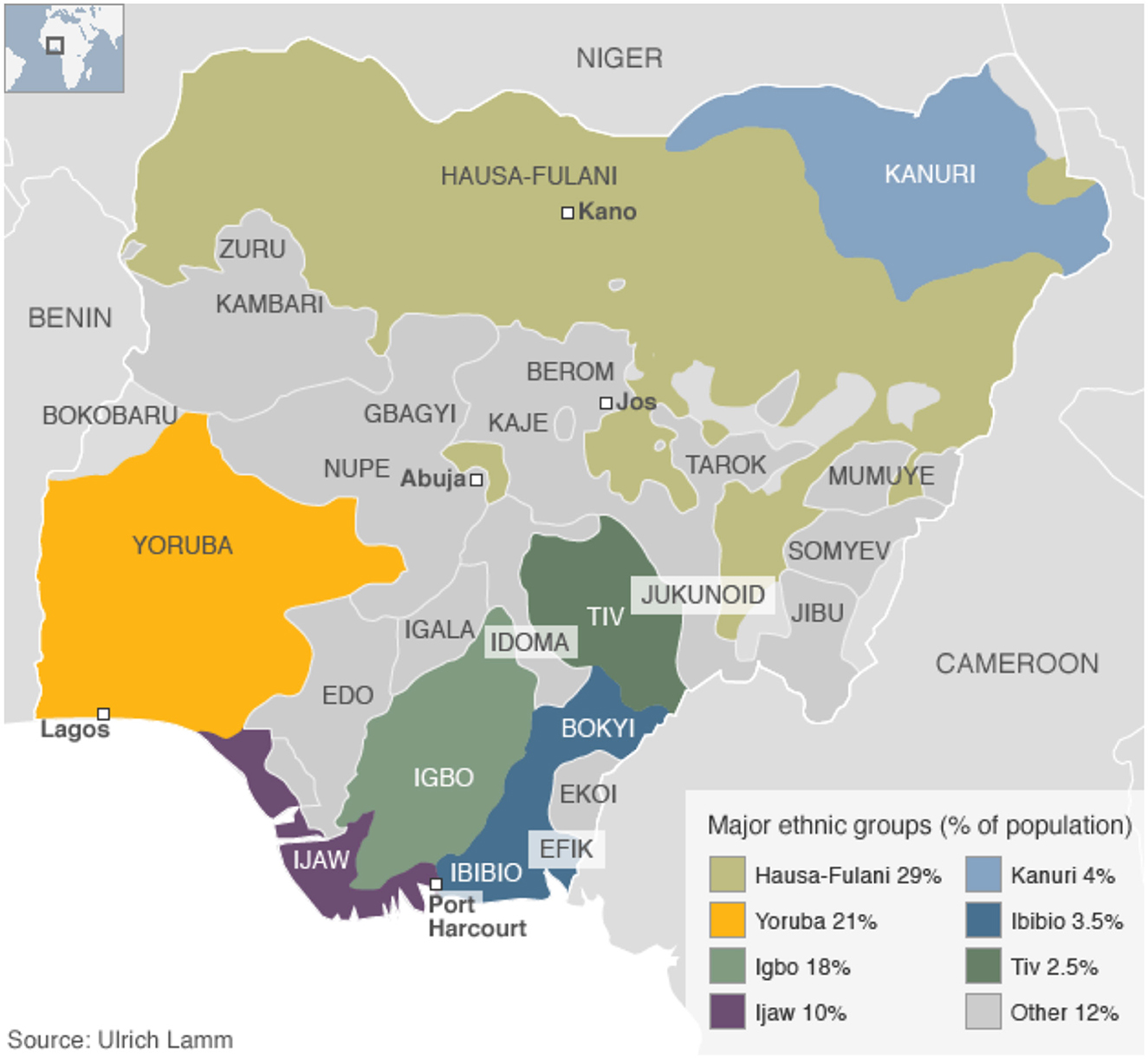

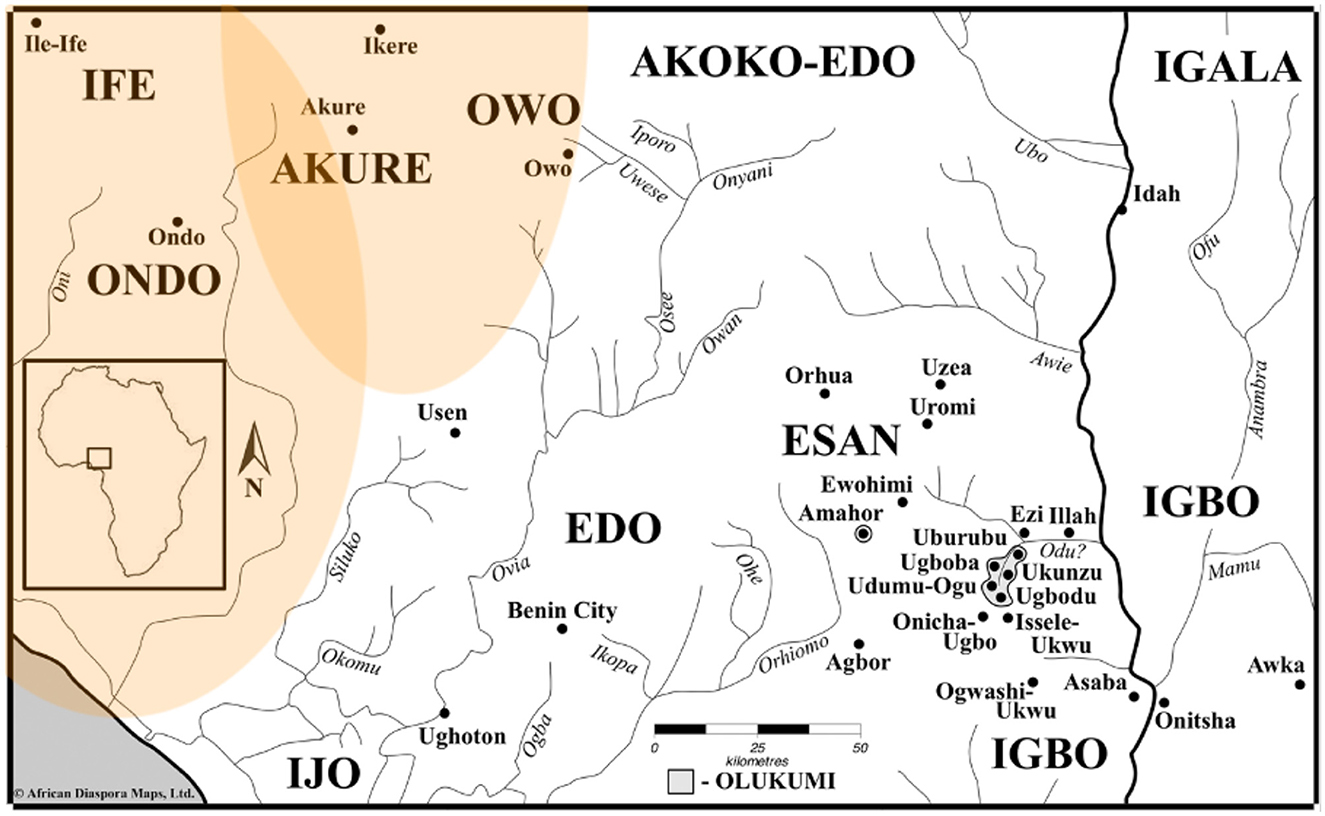

In this paper, we examine diverse conceptualizations, meanings, and semantic interpretations of peace within selected Indigenous cultures in Nigeria and Bolivia. In the subsequent sections, we analyze how dominant notions of peace, often shaped by external influences, have evolved and, in turn, impacted colonized Indigenous communities. For example, Western European peace concepts have been shaped by Roman culture and Judeo-Christian traditions, indirectly influencing the peace frameworks of colonized peoples. In the Yoruba case, we highlight the influence of Islam on peace semiotics and attempt to reconstruct pre-Islamic meanings by exploring Lukumi, a Yoruboid tradition maintained by the Ukwu-Nzu people, who diverged from the broader Yoruba group centuries ago and remained untouched by Islamic influence. The Lukumi or Olukumi (Yoruba word for “My confidant” or “my friend”) comprises eight communities including Ukwu-Nzu or Ukwunzu and Ugbodu (Nkemnacho, 2023) (See Figures 1, 2). In addition, we explore the Ubang, an Indigenous Nigerian culture with gender-specific, mutually unintelligible languages, to investigate whether gender language differences shape their conceptualizations of peace. In addition, we explore the ontologies and peace conceptualizations of the Aymara people in Bolivia, synthesizing these understandings with the broader themes identified across the Indigenous cultures under study.

Figure 1. Ethno-linguistic map of Nigeria showing principal linguistic groups (Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, 2025, Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin).

Figure 2. Olùkùmi Towns and their neighbors (grayed on the map) (Lovejoy and Ojo, 2015). The areas highlighted by the corresponding author in orange (oval-shaped) are parts of the Yoruba ethnic group of Southwestern Nigeria.

Through this comparative analysis, we aim to illuminate the sociocultural dynamics that shape peace narratives across diverse contexts, mostly among groups that have been largely excluded from dominant conceptualizations, implementations, and operationalization of the peace concept. We also advocate from the findings from this study that peace should be understood multidimensionally and multiculturally rather than peace as a mono-narrative.

We employed a qualitative cross-cultural exploratory study approach combined with qualitative multi-method analysis to help examine the cultural ontologies of peace across different purposively selected communities of Nigeria and Bolivia. This methodological approach allows researchers to study phenomena and cultures across various cultures. It has been used to study cross-cultural differences in the perception of luxury across six countries, to explore the perception of mental illness across different countries, and to the social representation of “hearing loss”(Godey et al., 2013; Manchaiah et al., 2015). It has also been used to study cross-cultural ontological studies of strong and weak ties rationalities (Yeh et al., 2023). We understand that whereas there are extant studies in peace research that have adopted this approach to investigate diverse issues such as social representation (Van der Linden et al., 2011), xenophilia (Stürmer and Benbow, 2017), mental typologies (Dreyfus, 2002), etc. Applying it to peace meanings and ontologies is new and relevant.

To this end, the selection of indigenous cultures of Nigeria and Bolivia for this study was based on their shared postcolonial histories and the presence of diverse yet underrepresented Indigenous peace ontologies. We purposively selected the Yoruba, Ukwu-Nzu, Ubang, in Nigeria and Aymara indigenous cultures of Bolivia because of the convenience of access to the authors due to cultural and language affiliation or study familiarity or proficiency; hence, the cross-cultural approach to the study. In addition, the cases also provide valuable comparative insights into the impact of colonial imposition on Indigenous epistemologies.

Hence, a key strength of this study lies in its ability to draw meaningful linkages between the Nigerian and Bolivian case studies while respecting their unique cultural contexts. Both case studies employed a qualitative cross-cultural exploratory approach, which enabled a comparative analysis of Indigenous peace ontologies shaped by shared postcolonial histories. The semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and direct observations in Nigeria mirrored the elite interviews and literature reviews in Bolivia by focusing on capturing socio-linguistic nuances, relational dynamics, and community-specific practices. This mirrored structure highlights the relational nature of peace in both contexts, as seen in the Yoruba's emphasis on cosmological balance and communal wellbeing and the Aymara's philosophy of suma qamaña (living well), which integrates harmony with nature and collective resilience. By juxtaposing these methodologies, the study explores how global colonial legacies intersect with localized epistemologies, providing a robust framework for examining the diverse yet interconnected ways peace is conceptualized and practiced. This deliberate methodological alignment not only enhances the comparability of findings but also underscores the importance of reflecting on the cultural and historical dimensions that shape these ontologies. Overall, this tailored methodological design ensured a nuanced understanding of peace conceptualizations in both contexts. Thus, it highlights the socio-linguistic and cultural specificities that underpin Indigenous epistemologies.

Data collection involved semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and direct observations of Indigenous peoples in Nigeria (Ukwu-Nzu and Ubang). In Nigeria (in February 2022, we conducted two interviews at the palace of the palace of the monarch of Ukwu-Nzu (HRM Obi Christopher Ogo, the Obi of Ukwu-Nzu) comprising the king and his chiefs (all men-−6 adults and 1 youth leader). We recognize that most cultures in Nigeria are predominantly hierarchical and male-dominated. Interestingly, our first contact with the town was a female journalist, who offered an initial overview of the town but mentioned that we could only get the data we sought from the king and his chiefs since they are the custodians of the cultures and traditions of the people. We interacted with 3 middle-aged women when leaving the town, but they also affirmed and reiterated what the initial contact person told us.

In the Ubang case, we conducted 4 interviews, 2 with the king (HRH Ochui Ubang the 5th) and his chiefs (all male−5 adults). We had to get their permission to conduct further interviews in the community. When we visited the town, we were directed to the palace, the sole custodian of the culture and authority of the Ubang people. After securing that permission, we were given unfettered access to the people. Thereafter, we conducted separate focus group discussion sessions—one session had all female participants (7 female); the other session consisted of a mixture of male and female youth members of the community (5 male, 4 female). All the interviews were semi-structured. The interviews and focus groups were conducted in English (pidgin)—Nigeria's formal language. The local words and phrases were translated by multilingual members of the community. In Ukwu-Nzu, a youth chieftain working on a Project by the Bible Society of Nigeria to translate the Bible to Olùkùmi was present in the interview sessions to help with the translations.

The Yoruba ontologies and epistemologies of peace were derived from an analysis of existing literature, supplemented by consultations with three Yoruba scholars specializing in the philosophy of religion and epistemology within Yoruba traditions. These included Dr Olatayo Olaleye George, a lecturer and researcher in comparative studies of world religions at Redeemer's University, Ede, Osun State, Nigeria, and two other scholars who will remain unnamed due to a lack of permission for disclosure. In Bolivia (Aymara), data were collected from 31 elite interviews between 2017 and 2019. The interviewees comprised 10 Indigenous activists, 5 community leaders, 7 students, 6 lawyers, and 3 NGO workers. The sample was evenly split between men and women (16 men and 15 women). Additionally, five Aymara elders, three men and two women, were included due to their leadership within the ayllu (community) and their deep knowledge of traditional governance and Indigenous rights. The age range of participants varied from 21 to 85 years, ensuring representation across different generations. The younger participants (students and early-career professionals) provided perspectives on contemporary challenges.

In comparison, older participants, particularly the elders and long-standing community leaders, contributed insights on historical struggles, Indigenous governance, and legal battles for rights recognition. Generational differences were also evident in how participants articulated peace, with younger individuals focusing on institutional reforms and protests. At the same time, elders emphasized community cohesion and ancestral knowledge as fundamental to sustaining peace. Reviews of the literature on Aymara peace conceptualizations and ontologies were also included. The semi-structured interviews involved collecting guided yet flexible conversations. This approach seeks to uncover participants' worldviews and perspectives (Adeoye-Olatunde and Olenik, 2021). In contrast, focus groups utilize group interaction to gather insights that might be less accessible without the dynamic found in a group setting. Unlike individual interviews, focus group members engage in discussions with each other in addition to the interviewer, resulting in a deeper exploration of the topic. Lastly, direct observation requires the researcher to become actively engaged within the community, observing interactions to gain a nuanced understanding of the cultural environment (Lofland et al., 2022) and a glimpse into these worlds.

To analyze the multiple data types, we transcribed audio recordings and used field summary notes to identify key themes. These themes were synthesized holistically rather than presented in topical formats, considering the cultural diversity and unique nature of each case. For example, in the Yoruba case, existing literature on the concept of peace provided a foundation. We explored the meaning and representation of peace among a related linguistic family that separated from the original Yoruba groups centuries ago. This included investigating whether the term for peace and its conceptualization remained consistent. Among the Olukwumi people of Ukwu-Nzu, peace—associated with tranquility in the larger Yoruba context—was embedded in their language and understanding of peace.

In contrast, the Ubang case focused on the gendered nature of peace, examining potential variations in how peace is conceptualized. A summarized thematic analysis was applied to these findings. The same analytical approach was also utilized for the Aymara case, ensuring consistency in methodology across all cases.

Overall, it was a profound learning experience. Our positionality as researchers—familiarity with these communities' cultural and linguistic contexts—allowed for a collaborative approach wherein the voices and lived experiences shaped the findings. Overall, this enabled the exploration of peace conceptualizations, cultural practices and ontologies, and the historical and political dimensions that inform these communities' worldviews.

The gap in the literature addressed in the document revolves around the underrepresentation of Indigenous peace ontologies and epistemes. It highlights how dominant frameworks in peace studies often universalize Western-centric or liberal peace concepts. For this reason, the study seeks to de-peripheralize Indigenous perspectives, such as those of the Yoruba in Nigeria and the Aymara in Bolivia, ensuring they are recognized not as marginal alternatives but as integral components of global peace discourses. Focusing on the socio-linguistic and cultural foundations of peace, the research highlights the need to recognize the plurality of peace concepts that emerge from different cultural and historical contexts. In this regard, the study explores how colonial legacies have shaped and often suppressed Indigenous conceptualizations of peace, proposing a decolonial approach to integrate these marginalized ontologies into broader peace frameworks.

Thus, the paper begins with an introduction to the critical role of Indigenous peace ontologies and their marginalization within dominant peace studies frameworks. Following the methodology section, which details the qualitative cross-cultural approach and multi-method analysis used to explore the Yoruba (Nigeria) and Aymara (Bolivia) communities, the paper transitions into its core sections. The first substantive section examines the conceptual underpinnings of peace within these Indigenous groups, exploring the Yoruba concept of relational harmony and the Aymara philosophy of suma qamaña (living well). This is followed by a comparative analysis highlighting the influence of colonial legacies and ongoing efforts to decolonize peace narratives. The discussion section synthesizes these findings, emphasizing the plurality of peace concepts and their implications for global peace frameworks. Finally, the paper advocates for including Indigenous epistemologies in peace studies.

Concepts possess socio-political ramifications that stem from how various perceivers or receptors translate and comprehend them. Certain terms are frequently assumed or construed to be universally comprehensible; for example, terms such as peace, violence, conflict, and truth are often communicated without accounting for the hermeneutical nuances of the receptors. Does the English word “peace” elicit the same meaning in the mind of a native English speaker as “salam” سلام does for an Arabic speaker? Furthermore, is it conceptually equivalent to “emem” in Efik or “aminci” in Hausa, even when both words are usually translated as peace? It is crucial to interrogate these ontological complexities, as conflicting parties cannot resolve their issues without mutual understanding of basic concepts related to their disagreement. There are instances where a word or phrase may be monosemic in one language but polysemic in another.

Beyond these linguistic challenges, translating conceptual terms from one culture to another often fails to adequately or sufficiently represent the same conceptual meaning in the receiving culture. Frequently, dominant conceptual meanings overshadow local Indigenous understandings of what the concept claims to represent. Conceptual relativism often translates to words having divergent hermeneutical implications across different cultures. It goes beyond mere linguistic relativism; it extends to how people express, understand, interpret, and associate with the concept. This also extends to their lived socio-economic realities. For example, the meaning of the English word peace has evolved and transmuted over time with the development of the language. Exploring the peace words rooted in Anglo-French via classical Latin and a comparative meaning in Anglo-Saxon helps show how these words have influenced cultural interactions with the peace terms.

Ethnographic studies have found peace systems across the different continents of the world, including the non-warring neighbors of the Nilgiri Hills in India Rivers, the Orang Asli societies, and quite notably, the Cheq Wong people in the Malay Peninsula, whose language “lacks words for aggression, war, crime, quarreling, fighting, or punishment” (Fry and Souillac, 2021). Several factors contribute to these peaceful behaviors, including overarching identities, prosocial interconnectedness, interdependence, non-warring values, reinforcing narratives and rituals, and visionary peace leadership (Fry et al., 2021). However, these groups' sociolinguistic and ontological aspects of peace conceptualizations have remained largely underexplored.

Numerous studies have explored the influence of language on cognition, perception, and behavior. Among them, Chen's investigation into the effect of language on economic behavior, particularly his linguistic-savings hypothesis (LSH), stands out. Chen posits that a decision maker's inclination to discount future rewards is linked to their linguistically induced biases in time perception and the precision of their beliefs about time. His study reveals that the grammar of the Chinese language, which lacks distinctive future tenses, contrasts with the English language's future-time reference de-volitive future “will.” This distinction contributes to speakers of “futureless” languages saving more, retiring with more wealth, smoking less, practicing safer sex, and being less obese (Chen, 2013). Chen reinforces this argument with a quote from Longinus: “If you introduce things which are past as present and now taking place, you will make your story no longer a narration, but an actuality,” (Anderson, 1987) further emphasizing how language influences perception, cognition, and behavior. Chen et al. (2019) have tested this hypothesis cross-culturally and come to more nuanced conclusions.

Cultural dynamics and multiculturalism engendered by globalization have disrupted a linear and static worldview, even those of Indigenous people. This can affect how individuals process concepts from varied perspectives. When people encounter the English word “peace,” they may interpret it through the lens of their mother tongue, the colonial language, or both. The interplay of these perspectives highlights the need to include Indigenous peace ontologies and epistemologies in broader peace discourses, not as mere appendages but as integral components of the conversation.

Knowing the leanings of persuasion of peace in any discourse and the language and expression by which the narratives are framed will help decipher the direction and meaning of such a concept. According to Michael Silverstein, “Events of language use mediate human sociality. Such semiotic occasions develop, sustain, or transform at least part—some have argued the greater part—of people's conceptualizations of their universe.” (Silverstein, 2004). According to Ngugi wa Thiong'o, “language, any language, has a dual character: it is both a means of communication and a carrier of culture” (Ngũgĩ, 1986, p. 13). It is a repository of culture and worldview. As part of language, terminology is thus deeply connected to ontology, serving as a reflection of how communities understand and relate to the world. This perspective highlights the importance of examining the terminological frameworks through which peace is conceptualized in both dominant and Indigenous contexts.

The English word “peace” originates from the Anglo-French pes (mid-12th century) and Old French pais, like all Romance languages (Portuguese and Spanish: paz; Italian and Romanian: pace), rooted in Vulgar Latin pacem (nominative pax), translating to compact, agreement, or treaty of peace (akin to the word pact) (Merriam-Webster, 2025). This borrowed term shaped the meaning in these subsidiary languages to signify freedom from civil disorder and the internal peace of a nation. The meaning traces back to the Proto-Indo-European root *pag-, meaning “to fasten,” implying a pact or binding agreement: Latin Pax (Harper, 2025; Shipley, 2001). The Peace of Rome (Pax Romana) refers to negotiated peace derived from pacts, describing the period between 27 BCE and 180 CE, from the reign of Augustus (27 BCE−14 CE) to the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180 CE), covering the geographical territory of imperial Rome (Britannica, 2024). It is associated with the relative stability of Roman rule, military power, taxation, and governmental protectorates. Peace, in this sense, was an accord permitting people to retain their cultural identity, religion, and ways if they maintained fealty to Rome: a hegemonic peace. Inter-tribal wars were repressed, consistent codified laws existed, and Latin, Rome's language, helped navigate cross-national barriers.

Pax is not only a political ideology but also stems from the religious culture of that period. Pax, the Roman goddess of peace, borrowed from the Athenian Greek Eìρǹνη (Ëirene), the goddess of peace, was often depicted holding Plutus (the god of plenty) in her left arm, representing the guaranteed protection of peace (Ëirene) and plenty (prosperity) under the maternal care of the public (state) (Theoi, n.d.). In the Roman adaptation, Pax, daughter of Jupiter and Justitia, the goddess of justice, symbolized how peace is ensured through obedience to the state's judicial power—a pacification ensured by conquest, a transactional peace.

Subsequent empires and global powers (e.g., Pax Britannica) adopted similar conditional peace styles in their relationships with the people and cultures they colonized. Local political and administrative structures and cultures were replaced with codified colonial laws in exchange for protection and ease of tax collection. Consequently, peace became associated with regime stability—a heritage of the Graeco-Roman Pax Peace ontology. Post-Second World War, dominant peace discourse, processes, and models have followed the American-led liberal democratic tradition or the liberal peace systems: a “rule-based international order”(Ikenberry, 2005) where peace is generally associated with law and order and organized around “open markets, security alliances, multilateral cooperation, and democratic community,” (Ikenberry, 2005, p. 133) all backed by American hegemonic power projections—economic, military, cultural, and political superiority. Subsequent dominant peace initiatives, discourses, and conceptual framings have taken this Pax-inspired trajectory.

This newer pax-inspired word replaced the much older Anglo-Saxon frið*u or friþ, which comes from the Old Norse frið*r, Old Saxon frithu, and German friede from which the English word friend is derived means “peace,” “happiness,” or “calmness”(Cleasby and Vigfusson Dictionary, 2025; Harper, 2025). It is contiguous with the Old English word Sibb, from where the modern English word sibling originates. Both frith and sibb depict kinship or relations regardless of sex or gender (Hodge, n.d.; Chrestomathy of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon Written Records, 2025). They portray peace as a harmonious state of happiness or tranquility, unlike the peace maintained by state-sanctioned violence for state or regime stability. Modern Nordic languages have retained this peace meaning. In Nordic languages, fred and frid are coterminous with peace. In Swedish, Lev i fred, var i frid; in Norwegian and Danish, lev i fred, vær i frid; and in Icelandic, lifð*u í freð*i, vertu í frið*i, all translated as “live in peace, be at peace.” Fred can be interpreted as the absence of war, while frid indicates the absence of disturbances (calmness, tranquility). This peace emphasizes relationship and kinship rather than state-guaranteed peace, the latter being a form of civil peace. These different peace ontologies possibly influence why the Nordic states are among the most peaceful countries in Europe. They are consistently considered among the peace societies of the world. It enhances the observation that concepts influence how people perceive and relate to the world.

Augustine of Hippo's work—“On the City of God Against the Pagans” (Latin: De civitate Dei contra pagans) is a Christian polemic treatise on peace. His work aimed to answer critics who blamed the fall of Rome on the neglect of the Old Roman Religion for Christianity (Augustine, 1998). Augustine pushed a philosophical idealism rooted in Plato's Socratic dialogue ideas in The Republic to respond to the chaos of the day. According to Augustine's dualistic ontology, there is a City of God (Civitas Dei: Heavenly), which contradicts the City of Man (Civitas Terrena: Earthly). The former is the ideal that most Christians aspire to in expectation of eternal peace in a transcendent heaven—a reminiscence of Plato's ideal world. At the same time, the latter is the ephemeral wall of human passions, aspirations, and interactions (Hollerich, 1999). Peace in the City of Man is transitory and not guaranteed, while Peace in the City of God is eternal and eschatological. However, he recognized the inner peace believers would experience during their sojourn on earth (Page, 2024). This is temporal, unlike the perpetual peace in the hereafter. This underlying philosophy has influenced the later works of theologians like Thomas Aquinas and John Milbank. It has also influenced several Christian peace ontologies and theologies down the ages.

The Enlightenment period in Europe evinces an age of reason; its defining characteristics include the promotion of scientific methods over supernaturalism, rationalism, empiricism, constitutional government, the ideals of humanism, and a secular foundation for morality, the habeas corpus ad subjiciendum that prevents illegal imprisonment. Before this period, several European states were in turmoil; civil wars, territorial wars, and religious wars were the order of the day. The cultural renaissance of the Enlightenment saw a recourse to reason in all areas of human endeavors, including the quest for peace. Immanuel Kant's 1795 essay On Perpetual Peace suggests the imperativeness of peace as an “immediate duty” to be pursued by nation-states (Page, 2024). For peace to be achieved, he suggests mutual transparency between states, republicanism, freedom of movement, and a league of nations to adjudicate interstate disputes (Pinker, 2018). Kant also proposed international commerce; this underscores the political philosophy that emerged during this period, i.e., classical liberalism, which advocates civil liberties, the autonomy of the individual, free market economics, freedom of speech and conscience (Page, 2024).

The Enlightenment and Renaissance periods substantially contributed to the evolution of Western civilizations, influencing the continent's culture, philosophy, politics, and arts. The Renaissance, notably, facilitated the rediscovery of classical (Graeco-Roman) philosophy, arts, and literature. Western European conceptions of peace were shaped by their historical experiences, necessities, and the philosophies of these periods. The age of colonialism further propagated these conceptualizations across the cultures of the people they colonized. Consequently, liberal peace—characterized by a state-centric focus, political stability, liberal economics, democracy, and individualism—dominates contemporary peace discourses in these dominant cultures and those of the people they colonized (Richmond, 2006).

The Judaic tradition portrays peace as the outcome of obedience enshrined in the Torah– a reward for being loyal to the covenant between Yahweh and his chosen people of Israel (Isaacs, 2020). Shalom, Salam, Salem, and Shalam are Hebrew words for Peace. In this tradition, peace connotes wholeness, completeness, health, and prosperity (Precept Austin, 2019). It is an in-group manifestation not extended to people outside of the covenant. “Great peace to those who love Your Torah” - רָב שָלוֹ, לְאֹהֲבֵי תוֹרָתֶךָ (Psalms 119:165). There is a parallel to this in Islam, which means complete submission to the will of Allah. In Christianity, on the other hand, at least those of the Pauline Christian persuasion, non-Jewish people who accept Jesus as savior have these benefits offered to them. Only in this instance, peace is not merely a reward for obeying some ancient laws and customs in exchange for wellbeing, absence of war, cessation of pestilence, and tranquility in the here and now—as obtainable to the Jews—but the Christians, according to this new covenant are assured of ultimate and absolute peace in the hereafter. Earthly peace—a weak copy of heavenly peace, can be achieved if non-believers confess their past deeds and recognize Jesus as their savior. There are some exemptions, though blasphemy against the holy spirit. Overall, there is no true peace without Jesus.

The amalgam of Shintoism and nationalism heavily influences the Japanese conception of peace. During the Second World War, the basis for Japan's entry into the war was to ensure “peace in the East.” Shintoism is a pacifist religion—some see it as better described as a philosophy. Kokka Shinto or State Shintoism is an infusion of Japanese ultranationalism where the emperor is considered a god: a descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu, and Japan and the Japanese are superior to all other human races and lands (Adegoke, 2018). Compliance with this nationalistic doctrine was driven by a sense of maintaining the in-group stability perceived to be threatened by foreign aggressors. The idea of peace in this tradition is, therefore, rooted in nationalism and the maintenance of order and stability of the state. Japan is an insular culture; this is an insular nation; this is ingrained in their Shimagunikonjo (島国根性) “Island nation” philosophy (Steiner, 1945).

Peter Tasker highlighted the strength of this cohesion and their fear of the dilution of their national culture thus: “Foreign observers often see mass immigration as a cure-all for Japan's demographic problem. It hasn't happened and isn't likely to: In the Japanese hierarchy of needs, social cohesion ranks higher than top-line growth” (Tasker, 2011). Their culture is entrenched in the state, headed and represented by the divine emperor. Stability or harmony is associated with peace; hence, the common word for Peace in Japanese is Heiwa (平和), which means peace, harmony, mild temper, being educated, and calmness (Nihongo, 2021). Other peace words from the same morphological root ideogram hei (平) include byoudou (平等)—equality, impartiality, uniformity; taira (平ら)—calm, quiet, placid, compound, stable, and chilled out. They have elements of stability, uniformity and harmony, which highlights the strong cohesiveness of the Japanese (Nihongo, 2021). Anzen (安全) refers to security, safety, and Peace of mind. Peace is also used for security and safety (Nihongo, 2021). Rebelling against the state or challenging the status quo is not habitual (Kubota, 1975). Ishida (1969) observed in the Japanese semantics of peace, the correlation between “heiwa” (peace) and “chowa” (harmony) is rooted in the preservation of the traditional system and customs. The in-group consciousness of the culture entails that peace is tightly related to harmony within the group, and any external aggression against such harmony must be resisted, even by violence, where deemed necessary.

The principle of dependent origination—the idea that existence is interconnected and independent—underpins Buddhist peace philosophy. Sentient and non-sentient beings are interrelated; therefore, peace is not limited to the individual self but the collective. Inner peace helps the individual to attain self-transcendence devoid of pain and negative thoughts. The Buddhist principle of ahimsa—“non-injury” has been associated with pacifism, although its practicality is subjective to individual interpretations. In Sanskrit, the sacred language of Buddhism, the term for peace (शान्ति shanti) denotes calmness, tranquility, and quiescence; Peace is the abstention from mental and physical violence toward living and non-living things (Tiwari, 2015). This peace is secured through a balance of complex interrelationships of all beings. This interconnectivity of existence connotes that an injury to one is an injury to all. Hence, the extension of collective peace to non-sentient beings contrasts with the other Abrahamic religions that conceptualize peace regarding man. The framing of peace without consciousness of the environment negates adherents of Buddhism and other South Asian religions' understanding of the concept. Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jnr., and Johan Galtung have shared or acknowledged some of Buddhism's core principles in their advocacies and endeavors (Chapple, 2000; Weber, 1999; Yeh, 2006).

As discussed earlier in this paper, each culture and language offer unique representations of their worldview and conceptualizations of lived realities. Many non-central cultures, particularly those in post-colonial societies, remain underrepresented in global peace narratives. There is a pressing need to integrate these peripheral peace ontologies into broader peace conceptualizations. These should not be regarded merely as alternatives but as essential contributions to the comprehensive understanding of peace, conflict resolution, and peace-making.

The histories, stories, traditions, and experiences of the people can help us know how the people express and understand peace. Indigenous communities in Africa and Latin America do not have the privilege of textually preserving these experiences to help codify their knowledge-belief systems that best encapsulate their thoughts and worldviews. Peace, among the Indigenous Yorùbá people of southwest Nigeria, is Àlàáfíà—a loan word from their largely Islamized Hausa neighbors. Lafia in Hausa means peace or harmony. A closer concept to that in Yorùbá is ìrọ́rùn (wellbeing, comfort). The Lucumi or Nago—a diasporan Yorùbá people mainly in Cuba, also use àlàáfíà as a word for peace. Lucumi or Ólùkùmi is an ethnonym for people Indigenous to southwest Nigeria who are now known as the Yorùbá people.

The people maintained their original ethnonyms even during slavery in America; some of the inhabitants in Freetown—a settlement for freed slaves (in present-day Sierra Leone) identified themselves as Akú or Ólùkùmi people rather than the modern Yorùbá ethnonym (Law, 1997). Akú is a descriptor derived from the greeting patterns of the people; the Yorùbá people have greetings for almost all seasons, activities, and events. Olùkùmi is loosely translated as “my kin.” The Yorùbá people see themselves not as individuals but as a whole community. The “A” in “A- kú” means “we”—a projection of their collective cosmogony and metaphysics. Modern Yorùbá people have been influenced by their neighbors, and their vocabularies have evolved to reflect these interactions. Hence, Àlàáfíà is not a proto word for peace among these people. The traditional or Indigenous conception of the word might be regained by examining their linguistic cousins who have not been impacted by these (in this case, Arab-Islamic) external influences. This helps to come close to what existed prior to these influences. In this case, the Olùkùmi language has some familiar terms for peace without any word indicating Arab or Judeao-Christian influences. However, these terms are still conceptually intelligible to the broader Yoruba group.

Àlàáfíà in Lucumi (Cuban Yorùbá variant of Olùkùmi) usage reflects the time and place in history when these people were moved to South America and the retention of the word at that point. The endemic nature of this usage could be traced to the influence o on the other southwestern Nigeria groups (1650–1750). The Ọ̀yọ́ people (Ọ̀yọ́-Ilé) are closer to the Nupe, Borgo, and Hausa cultures and people than their cultural relatives down south. These northernly Ọ̀yọ́ people influence the modern Yorùbá language through conquest and suzerainty. To understand the pre-colonial indigenous term used for peace, one must go as far back as possible before this imperial rule. This can be done by studying the group that left the mother language long before this influence became endemic.

Ukwu-Nzu is part of a proto-Yoruboid group that migrated from the broader group centuries ago (see Figures 1, 2). They recognize themselves by the Olukwumi ethnonym—a term used before Yorùbá became a generic name for the people Indigenous to southwest Nigeria. According to Robin Law: “the actual term ‘Yorùbá' occurs very seldom in the original documentary records (as opposed to the secondary historiography) of the slave trade. This is because, as is generally agreed, the people who now refer to themselves ‘Yorùbá' were not so-called before the 9th century” (Law, 1997, p. 205–206). The Olukwumi or Olùkùmi people are in 8 communities (Odiani Clan in Aniomaland) in Delta State, Nigeria. They speak a variant of the Yoruboid language influenced by Igbo, a dominant language their neighbors speak. But they still maintained elements of their mother language. There is no àlàáfíà in their dictionary.

Peace in Olukwumi is títùn1 which loosely translates to tranquility, stillness, calmness, or quietude. Tutù is a common name and word in the larger Yorùbá linguistic group, which can be similarly translated as the Olukwumi word for peace. Títùn or Tútù evokes femininity. Only omi tútù (cold water) is allowed in prayer rituals to Osun—the Yorùbá goddess of fertility. The implication of this is seen in the name Adétutù (a name for girls), which can be translated as peaceful reign (of a monarch). Unlike the borrowed term Àlàáfíà borrowed from the Hausa word lafia, which translates to “peace or good health or even harmony,” (Tahir, 2020) títùn or tútù appears more representative of the peace ontology of the Yorùbá people. Yorùbá has words like ìdẹrà, ìlera, ìròrùn, and ìf òkànbalẹ̀ meaning wellbeing, good health and good living, which all come close to the Hausa lafia.

In the Yorùbá example above, àlàáfíà as a borrowed term external to the Indigenous community, carries with it some theological implications from the original culture. Àlàáfíà in Christian and Islamic traditions is that state of tranquility, sometimes, in the absolute assured a believer who submits to the will of a supreme being. In this wise, only adherents of the faiths are guaranteed this privilege; unbelievers are excluded from this beneficence. This is contrary to Yorùbá worldview. Although the Yorùbá, believe that there is a supreme being known as Ọlọ́rùn (loosely translated as the owner of the sky), also called Olódùmarè, this divinity exercises their power with the assistance of 400 plus 1 òrìṣà (divine lieutenants) or irúnmolè. The plus 1 represents the limitlessness of these deities—you can keep adding one more. Hence, the Yorùbá have no one absolute religion to which everyone must adhere. Therefore, the concept of a negotiated peace dependent on absolute devotion to a being is antithetical to this worldview. Hence, àlàáfíà, a borrowed term, does not adequately represent this worldview.

Each of the 400 plus 1 Òrìṣàs oversees different human affairs (Ọ̀sun–fertility, Ajé–wealth, Ògún–farming and Iron, etc.); for good fortune in these affairs, humans must offer sacrifices to them. When they are pleased, there are positive outcomes; when upset, the consequences are adverse. These activities are often limited to events external to humans, e.g., seasons, droughts, fertility, health, epidemics, etc. The orishas control these elements and must be adequately appeased. If appeased, the transgressor(s) might incur their grievances. Relatedly, the Yoruba people believe that not all affairs are subjected to the dictates of these deities; these are personal to the human agent—their lots in life. This is known as àyànmọ̀ or ìpiín.

In Yoruba metaphysics, Orí (literally translated as “head”) or Orí Inú (inner head as distinct from the physical head) refers to the self or essence with equal status as that of the Òrìsà deserving of devotion and worship. While coming into the world, the Yoruba believe that the person to be born approaches, then existing as an Orí, approaches Òrìsà Ajala Mopin, the divine sculptor in his ilé orí (workshops or house of the head) and chooses a human head (Brandon, 2018). This head contains all the person's lots in life—good and evil. These lots are known as (allotment, portion, or choice) or ìpiín Orí. This exercise describes the ingenious Yoruba idea of freewill known as akúnlẹ̀yàn, àyànmó, akúnlẹ̀gbà. One's àyànmọ́ is associated with one's orí when the ìpiín is made (Balogun, 2007). However, free will does not sufficiently cover the Yoruba idea of destiny as it signifies the human capability to make confident choices that they may choose not to exercise.

To the Yoruba, that ìpín (choice) is imperative before a human can be born. Thus, àyànmọ́ is not freewill sensu stricto. Àyànmọ́ is also not strictly predetermination as that suggests a fixed choice pre-made or pre-written by an external being without the agency of the human person. Àyànmọ́ and its associated terms are not wholly predestination and not absolute free will. It is a spectrum of libertarian incompatibilism—a free choice. Free choice recognizes the independence of the decider to choose out of plenty of alternatives. The person is responsible for the choice made. Did the person have the power not to make any choice? The answer is no! This imperative does not mean absolute free will and is not a predetermination since no one, but the pre-human, made the choice.

This worldview implies that the Yoruba people do not have a term or concept for absolute trouble-free, tranquil living that peace (Greek: irene) or àlàáfíà means. That being so, the best understanding of the peace concept is through its manifestations, e.g., ìrọ̀rún (wellbeing), ìfọ̀kànbalè (tranquility). The absence of these manifestations is either attributable to some infractions against the orisha or ascribed to the person's àyànmọ́ or orí. According to Ifà, a collection of Yoruba knowledge and divination corpus, “tibi tire la dá Ilé ayé,” meaning “reality is a union of opposites” (Opasola, 2025). Consequently, peace is not an exclusive outcome of obedience to a precept but is also not transactional. Èṣù—the deity (Òrìṣà) of justice, enforcer of natural and divine laws and orders, when offended, wreak unpalatable occurrences on the transgressor (Falola, 2013). Thus, it can be inferred that the Yoruba worldview does not support seeking peace without justice or restitution. Even when the offended person has passed, the offender must appease the Orí of that deceased for peace to manifest.

Christian and Islamic theologies have significantly influenced the peace ontologies of the Yoruba. A notable example of this influence is the frequent translation of the Yoruba word for peace as àlàáfíà—an Arab-Islamic derivative. This translation is commonly propagated by platforms like Google Translate and other machine translation applications, presenting it as the Yoruba term for peace. This phenomenon mirrors how pax from the Graeco-Roman traditions gradually supplanted the Old Anglo-Saxon conception of peace. In contrast, the proto-Yoruba groups of Olùkùmi or Olukwumi in Delta State, Nigeria, with minimal exposure to Islam, have preserved their original peace ontologies. They view peace as wellbeing, equilibrium, and tranquility, unlike àlàáfíà, which was initially popularized by Muslims and later embedded in Yoruba translations of the Bible. The concept of àlàáfíà is theocentric, contingent upon submission to, or adherence to, the divine will of a supreme being, and guaranteed by following divine dictates and laws. This notion is akin to Augustine's City of God rather than the fundamental Yoruba conception of peace.

The Yoruba ontology of peace acknowledges humans as the architects of their destiny. However, unlike other forms of predestination, the Yoruba believe that certain aspects of a person's life can be influenced by divinities, wicked individuals (ọmọ aráyé), personal actions (àfọwọ̀fà), ill-fate (orí burùkù), and one's character (íwá). Yet, one's ultimate destiny (àkúnlẹ̀yán), witnessed by Olódùmarè (the supreme deity) and Ọ̀rúnmìlà (deity of wisdom, knowledge, Ifa divination, and Olódùmarè's “prophet”), remains immutable. In Yoruba thought, peace is not vested in the state or a sovereign; it is embodied in personal experience. It is a term that denotes happiness, tranquility, and balance, free from legalistic constraints or pacts. Unlike other cultures, the Yoruba do not have a specific deity of peace.

In our quest for reconstructing peace among Indigenous communities, we also went to Ubang, a community in southern Nigeria where males and females speak different languages (gender diglossia). These are two mutually unintelligible languages. For instance, the word tree means kitchi to men and okweng to women (Adegoke, 2018). Although there are apparent lexicon differences, we sought to understand if they have a similar word for peace; if not, are there ontological differences in their understanding of the peace word? This brings to light the issue of gendered cognitive styles, precisely the epistemic question of whether men and women possess different cognitive characteristics, such as modes of perception, thinking, problem-solving, memorizing, and remembering (Anderson, 2024). In the context of the Ubang Indigenous people, does the gendered nature of their language influence differing conceptualizations of peace between men and women? In addition, is the concept of peace consistent despite these gendered linguistic variations? This community offers a unique opportunity to explore these hypotheses further. While the Ubang language is distinctly gendered, there are mutually intelligible words, and the concept of peace is universally understood.

Peace is Ekuen or Ikwen in both the female and male languages.2 Ekuen connotes togetherness or orderliness.3 But the difference is in how it is understood or interpreted. For the male, “order” is more conservative and implies maintaining the status quo, while the female understanding is about stability and familial. Although the pronunciation sounded the same to us, we understood through their narratives that the interpretation or performance of peace differs according to gender. For example, during Focus Group Discussion II, a female participant stated thus: “When there is a conflict, that cannot be resolved by the men, there are instances where an elderly female member of the community is consulted, and her opinion on the issue is respected; thereby helping to restore order.” Another participant (male) observed that: “For the men, the order is important; our women seek stability… they don't want trouble. Peace for us, men, is for things to remain normal.”

It was acknowledged that there are terms they used differently for Peace but that Ekuen is the common term used in most cases. The opposite of Peace is riran—conflict and instability.4

This section put forward a synthesis of the conceptualizations of peace and the ontologies of the Aymara people of Bolivia drawn from the literature and the relevant interviews discussed in the methodology section. It is structured into two primary topical subsections: first, peace as intercultural harmony, and second, peace through protest.

Indigenous peoples in Latin America have different understandings of peace. Notably, peace is often equated with harmonious living and the need to acknowledge historical injustices. In that sense, there is an element of inclusiveness and protest. For this reason, peace based on intercultural harmony is an ethical and social milestone. These ideals result from the struggles, injustices, and ideals interwoven within the broader Bolivian social tapestry, including the socio-cultural fabric of the Aymara people. Many Indigenous peoples have preserved their belief systems, languages, and other millenary traditions despite colonialism. Notably, more than forty per cent of Bolivians self-identify as Indigenous (Estadística, 2013), even though the colonial project undermined their collective identities and historical memory through a policy of genocide and assimilation.

To begin with, the understanding of peace is not merely the absence of war and violence. It entails protecting all sentient beings. According to Aymara Indigenous epistemes, individuals do not exist in isolation from the rest of the community or nature. In this regard, it is a rejection of individualism and anthropocentric notions (Kárpava and Moya, 2016) which have shaped hegemonic peace studies. In studies carried out in Bolivia from 2017–2019, Indigenous activists, leaders, students, and lawyers were asked about Aymara episteme. Accordingly, the suma qamaña is a core value for the Aymara people. It is often defined as living well. It entails living in harmony not just alongside other humans but also among other living beings. Additionally, this is complemented by different values like ñandereko (live harmoniously), teko kavi (the good life), ivi marae (land without evil), and qhapaj ñan (noble path or energy).

In many ways, it reveals the fundamental conceptual differences between dominant (mostly colonial) and Indigenous cultures' understandings of peace. From a philosophical perspective, interculturality is the plurality of values, episteme, cultures, peoples and nations within Bolivia. Furthermore, peace is rooted in the conception of “Pachamama.” This term is a compound of the word “Pacha,” which in Quechua means “universe, world, time and place.” The second word, “mama,” corresponds to the term mother. Pachamama is an Andean deity related to the earth, motherhood, and femininity (Lira, 1944). The Pachamama symbolically represents Mother Earth in all its dimensions. In other words, it refers to Mother Earth physically or naturally, referring to the earth as an ecosystem. It also represents Mother Earth in a metaphysical sense, a presence with which the rest of the sentient and living beings can be in a permanent dialogue (Merlino and Rabey, 1983).

According to an Aymara leader, the concept of “suma qamaña” is profound; it refers to the relationship between humanity and nature and between the Indigenous cultures and those of Western traditions. That is why he affirms the importance of establishing “an intercultural dialogue between the West and Indigeneity, having us as interlocutors in that long conversation. It is not a soliloquy” (Interview 12, an Aymara leader, 2019). In this sense, peace is an innovative contribution, which makes Bolivia a noteworthy case study. It implies raising the status of other living beings (non-human animals) and other cultural and epistemic traditions that had been excluded from the social theater. By including different worldviews, it is acknowledging multiple national identities. In this regard, it is the effort to establish an inclusive and intercultural peace negotiated between various social actors.

Furthermore, peace is not synonymous with passiveness. Quite the contrary, the search for peace has inspired countless protests and marches. There is another layer to peace, the acknowledgment of historical injustices. This understanding of peace was articulated by Rigoberta Menchú—a K'iche' Guatemalan human rights activist, feminist, and a 1992 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who declared, “peace is not only the absence of war; as long as there is poverty, racism, discrimination, and exclusion, it will be difficult for us to achieve a world of peace” (Bedriñana and Giovanna, 2019). Within this conception, protests are crucial to peace. In Bolivia, the quincentenary of the beginning of colonization was a further impetus for many Indigenous activists and organizations (van Cott, 2000). In addition to the long-term historical injustices, the protestors were against the neoliberal policies implemented in the eighties. The fiscal austerity and the exploitation of natural resources provoked a backlash (Haarstad and Andersson, 2009). Hence, the social protests and movements were the by-product of an alliance between two struggles, “one against 5 centuries of domination by Europeans and their descendants, and the other against two decades of neoliberalism.” (Hammond, 2011).

One of the aims of the Aymara people was to break with historical injustices (de Sousa, 2007). In this regard, peace efforts became linked to the attempt to decolonize Bolivia's social, legal, and political order. The term “decolonize” has been defined by Fanon as the social process “which sets out to change the order of the world […] there is, therefore, the need of a complete calling in question of the colonial situation.” (Fanon, 1991). Colonization was a process that entailed extermination and exclusion (Rivera Cusicanqui, 2010). The method of domination, marginalization and even persecution was initiated with the Spanish invasion. It was then upheld through colonial and postcolonial economic, political, and legal frameworks.

Fanon considered that democracy had been unable to take root in Latin America as a “dialectic result of states which were semi-colonial during the period of independence” (Rivera Cusicanqui, 2010, p. 171). It should be noted that even after Bolivia ceased under Spanish colonial rule, it continued to be shaped by the colonial model and mindset. In this sense, decolonization implies dismantling the lingering vestiges of the colonial order and ideology. In this regard, Aymaras consider that intercultural and decolonial peace promotes harmony and democracy by remedying historical injustices. However, an Indigenous law professor stated, “there is a process of stagnation regarding interculturality […]. It is part of a growing democratization process. The development of Bolivian society happens in a spiral” (Interview 17, 2017). Rather than viewing progress as a linear process, he considers progress a spiral. There are advances, and there are setbacks. Little by little, it is never a simple path. Instead, it is a journey through a labyrinth.

It is critical to reiterate that the vindication of the episteme of the Indigenous peoples has involved a long process. Thus, is a process that is neither simple nor linear; it gushes out like the sea: deep and tangled. It is a process that aims to redefine what it means to be “Bolivian.” Moreover, is a process that tries to determine a country's future by critically re-examining past interpretations. In this regard, it is a decolonial peace aiming to transform the collective imaginary, historical memory, and institutional underpinnings.

Decolonizing peace to create spaces for cultural and epistemic diversity has been a long and complex process. From an ethical standpoint, an Indigenous understanding of peace is not only a rupture with historical injustices but a blueprint to guide the diverse Bolivian peoples and nations toward a more peaceful and inclusive future. In addition to trying to end historical injustices, it reveals the effort to break with the exclusion of non-western episteme. Always with the desire to create an inclusive world, thus providing enough room for all voices, traditions, and dreams. It has required centuries of tireless resistance and is not yet finished. The Aymaran conceptions regarding peace suggest that peace is not the absence of violence or a passive process. It is a process that requires the participation of all the social actors, bearing in mind the existence of the rest of nature. Above all, it is an ever-changing conversation defined by a myriad of voices seeking harmony.

Multiple studies on meanings-construction have recognized the untenable position of traditional conceptions of words and meanings as “lexical entries” (Pustejovsky, 1995; Evans, 2006). Departing from this, this paper calls for recognizing the conceptual relativism inherent in peace semiotics and ontologies. It further proposes a social constructivist framework that moves beyond conventional definitions, morphemes, and syntactic structures, accommodating diverse interpretations of peace from marginalized communities. It is usually taken for granted that Peace qua Peace exists in some form in all cultures. Even critical peace theorists and those who advocate decolonization of peace epistemologies work on this assumption; there are plenty of stories on cultural peace studies and tribal narratives of peace, amongst others, jostling for the voices of these silenced opinions to be heard. However, the big question remains: Is peace universal or particular? Are the interlocutors on the same epistemic plain when the word is uttered? There are existing studies focusing on peace narratives and the practical use of peace ontologies of Indigenous communities to understand peacebuilding and conflict resolution processes (Campbell et al., 2017; Randazzo, 2019; Synott, 1996).

Although several peace studies and scholarships advocate decolonizing peace, epistemes, and methodologies (Breen, 2011; Harvey et al., 2021; Forero, 2012), more studies must be done to center and platform Indigenous peace ontologies and concepts from the dominant liberal peace frameworks. To address this gap, this study advocates for the incorporation of diverse peace ontologies, employing the term “ontology” in the plural to highlight its philosophical (metaphysical) and linguistic (cultural semantic) dimensions rather than its formal application in computer science.

This study advances a de-peripheralization of minority cultural ontologies as part of broader epistemic decoloniality attempts. These oft-neglected meanings are to be included as part of the many alternatives for peace understandings on the same standing as the more dominant ontologies rather than being relegated or nativized. This observation is not unique to decolonial studies; there are calls for relational reorientations—beyond ontology, epistemology, and methods in international relations (IR) against classical substantialism that imperiled non-Western ontologies and epistemologies (Kavalski, 2018; Kurki, 2022).

Narratives are collections of experiential stories of a community of people and how they interpret their world. Nevertheless, these “how” problems are addressed, usually through the aid of Western metatheories. There are equations and adequations of these local experiences regardless of their unrelatedness in some cases, thereby making them exotic facsimiles of some grand theories of the West. The essentialism of the peace concepts by the dominant voices drowns the actual epistemic value ascribed to it by the local Indigenous people. There is, therefore, a need to ask the “what” question: What is Peace according to the Yoruba, to the Aymara, and so forth?

In many ways, there is no simple answer to that question. The research seeks to highlight the diversity of Indigenous peace ontologies whilst revealing commonalities in how postcolonial contexts shape these approaches. Despite the many differences, there are overlapping themes. For instance, there are the cosmological foundations to peace present in both contexts. The Yoruba envision peace as equilibrium mediated by Òrìṣà and personal agency (àyànmó or destiny). Similarly, the Aymara envision peace as harmony with Pachamama, emphasizing relational ethics between humans and the environment. There is a collective dimension to how peace is articulated. For the Yoruba, it is community-centered peace, often tied to kinship and collective wellbeing. Amongst the Aymara, the collectiveness refers it a peace that incorporates both human and non-human actors, with a strong focus on ecological sustainability. Lastly, there is the role of history in how peace is articulated. The Yoruba have integrated Islamic and Christian concepts (e.g., àlàáfíà) into traditional ontologies. Thus, peace is a recognition of the historical diversity. For the Aymara, peace also implies resistance to colonial frameworks through decolonial peace efforts and acknowledgment of historical grievances.

The Aymara peace suma qamaña (“living well”) is not individualistic and goes beyond harmonious human coexistence to include the environment and all forms of life encapsulated in the concept of Pachamama—Mother Earth – ecological peace. Peace to the Aymara is not wholly “passive”; it is also performative as seen in protests against historical injustices (See Figure 3). Relatedly, the Yoruba peace ontologies (ìròrùn: wellbeing, ìfọ́kànbalè: tranquility) represent a harmonious balance between man as an agentic being (proto-human: orí) and his immediate environment—both economic and ecological. Peace is a manifestation or the outcome of the choices (Ìpín: allotment or choice; and àyànmó: freewill) made by pre-existent human. Peace is not a fixed state but an outcome that is dependent on human choices, actions, and behaviors, some of which predate their existence, with some dependent on their interactions with their social environment. As discussed in this paper, these worldviews depict indigenous epistemologies and ontologies associated with their relationship with one another and their environments.

Nevertheless, it is challenging to acquire the pristine meaning of peace to these Indigenous people because of the influence of colonialism, which resulted in the gradual extermination of their languages. Language being essential to the preservation and transference of concepts and a people's ontology is crucial. However, in many of these communities, the imposition of colonial languages through the education system meant the loss of their already endangered languages. Vestiges of these meanings and knowledge systems can still be garnered through their various performance rites, rituals, and storytelling. These must be preserved to forestall further depreciation of these assets. Implementing peacebuilding programs without understanding the cultural-linguistic semiotics of a people and their ontology of the concept might be counterproductive. Although the people may speak English, Spanish, and French, their cultural inheritances heavily influence their ways of perceiving and interpreting the world.

It should be noted that there are an estimated 476 million Indigenous people around the world, representing around 5,000 different cultures facing the extinction of their languages by 2,100 (Buchholz, 2022; The World Bank, 2022). The phenomenon of disappearing Indigenous cultures, languages, and episteme is far from new. Indeed, the colonial process entailed the subjugation of entire peoples and nations and, in some cases, the destruction of their cultural and epistemic worldview. For this reason, in the 1940s, legal scholars like Lemkin coined the term cultural genocide, placing the annihilation of culture at the front and center of genocide. Lemkin rejected limiting the legal definition of genocide to mass murder. Instead, Lemkin argued that because culture is intrinsic to a social group's identity, the “essence of genocide was cultural” (Bilsky and Klagsbrun, 2018; Dirk Moses, 2010).

Above all, a peace that is exclusionary is, by definition, toothless. For peace to be effective, it must acknowledge the diversity of episteme and perspectives. To this end, it is crucial to promote a “nuanced understanding of the plurality of peace” (Bevington et al., 2018). By silencing and ignoring Indigenous and non-Western voices, peace is not an instrument of reconciliation but rather another form of violence. Hence, peace research based on intercultural dialogues is necessary.

It is imperative to emphasize the significance of preserving Indigenous ontologies and epistemologies of peace. The communities must initiate and sustain this process to ensure its longevity and authenticity. This study underscores the necessity for peacebuilding initiatives to acknowledge the cultural relativity of abstract peace concepts. These varying cultural paradigms illustrate that individuals' cultural backgrounds profoundly influence their expectations, commitments, and obligations regarding peace initiatives and processes. Understanding these cultural nuances is essential for effective and inclusive peacebuilding.

Concepts are building blocks of narratives. For meaning to be inferred, there must be some appreciable level of mutual comprehensibility between interlocutors and users of the concepts. Peace narratives are not exempted from this reality. Rather than imposing a universal understanding of peace or projecting a dominant peace concept, its relativity should be highlighted. Excluded peace epistemologies should be brought to mainstream conversations. Narratives are neither static nor monolithic; the basic concepts at their core are very often stable. This stability is tied to the identities—the defining characteristics of the people who own the culture. They are transmuted and preserved across generations. To understand this peace narrative undercurrent, a researcher must recognize the contextual relativism surrounding the concepts, even among these minority ontologies.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

DA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research was supported by a 2022 Carnegie Small Grant provided by the African Leadership Centre and a Clusters of Research Excellence (CoRE) in Interdisciplinary Peace Research grant.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^HRM Obi Christopher Ogo, Obi of Ukwu-Nzu and Mr. Joel (Olùkùmi Bible Translator), personal communication, February 21, 2022.

2. ^HRH Ochui Ubang the 5th, personal communication, February 19, 2022.

3. ^Ibid.

4. ^Youth, personal communication, February 19, 2022.

Adegoke, Y. (2018). Ubang: The Nigerian village where men and women speak different languages. BBC News.

Adeoye-Olatunde, O. A., and Olenik, N. L. (2021). Research and scholarly methods: Semi-structured interviews. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Pharm. 4, 1358–1367.

Anderson, C. (1987). Style as Argument: Contemporary American Nonfiction. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Anderson, E. (2024). “Feminist epistemology and philosophy of science,” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, eds. E.N. Zalta and U. Nodelman (Stanford University). Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-epistemology/ (accessed February 19, 2025).

Asante, M. K. (2006). “Social discourse without abandoning African agency: an eshuan response to intellectual dilemma,” in Handbook of Black studies, eds. M. K. Asante, and M. Karenga (London: Sage Publications), 369–378. doi: 10.4135/9781412982696.n26

Augustine. (1998). Augustine: The City of God against the Pagans. (R. W. Dyson, Ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511802300

Balogun, O. A. (2007). The concepts of ori and human destiny in traditional Yoruba thought: a soft-deterministic interpretation. Nordic J. African Stud. 16:55.

Bedriñana, A., and Giovanna, K. (2019). Declaración Americana sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas. Otra lectura, desde el Buen Vivir. Rev. Paz y Conf. 12, 251–264. doi: 10.30827/revpaz.v12i1.9507

Bevington, T., Kurian, N., and Cremin, H. (2018). “Peace education and citizenship education: shared critiques,” in The Palgrave handbook of citizenship and education, eds. A. Peterson, G. Stahl, and H. Soong (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 2. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-67905-1_51-1

Bilsky, L., and Klagsbrun, R. (2018). The return of cultural genocide? Eur. J. Int. Law 29, 373–396.

Brandon, G. (2018). Orisha. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/orisha

Breen, C. (2011). Reimagining the responsibility of the security council to maintain international peace and security: the contributions of “jus post bellum,” positive peace, and human security. Peace Res. 43, 5–50. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44779893

Britannica, T. (2024). Pax Romana. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Pax-Romana (accessed January 14, 2025).

Buchholz, K. (2022). Where the World's Indigenous People Live. Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/chart/18981/countries-with-the-largest-share-of-Indigenous-people/ (accessed January 14, 2025).

Campbell, S. P., Findley, M. G., and Kikuta, K. (2017). An ontology of peace: landscapes of conflict and cooperation with application to Colombia. Int. Stud. Rev. 19, 92–113. doi: 10.1093/isr/vix005

Chapple, C. K. (2000). Reviewed work: community, violence, and peace: aldo leopold, mohandas K. Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Gautama the Buddha in the Twenty-First Century by A. L. Herman. Buddhist-Christ. Stud. 20, 265–267. doi: 10.1353/bcs.2000.0005

Chen, J. I., He, T. S., and Riyanto, Y. E. (2019). The effect of language on economic behavior: examining the causal link between future tense and time preference in the lab. Eur. Econ. Rev. 120:103307. doi: 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2019.103307

Chen, M. K. (2013). The effect of language on economic behavior: evidence from savings rates, health behaviors, and retirement assets. Am. Econ. Rev. 103, 690–731. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.2.690

Chrestomathy of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon Written Records (2025). Sib. The Online Chrestomathy of Gothic and Anglo-Saxon Written Records. Available at: https://germanic.ge/en/ang/word/sib/ (accessed February 20, 2025).

Cleasby and Vigfusson Dictionary (2025). Friðr. Available at: https://cleasby-vigfusson-dictionary.vercel.app/word/fridr (accessed February 20, 2025).

Datta, R. (2018). Decolonizing both researcher and research and its effectiveness in Indigenous research. Res. Ethics 14, 1–24. doi: 10.1177/1747016117733296

Dirk Moses, A. (2010). “Raphael Lemkin, culture, and the concept of genocide,” in The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. doi: 10.1093/OXFORDHB/9780199232116.013.0002

Dreyfus, G. (2002). “Is compassion an emotion? A cross-cultural exploration of mental typologies,” in Visions of compassion: Western scientists and Tibetan Buddhists examine human nature, eds. R. J. Davidson, and A. Harrington (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 31–45. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195130430.003.0003

Estadística, I. N. d. (2013). Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2012. CEJIS. Available at: http://www.cejis.org/bolivia-censo-2012-algunas-claves-para-entender-la-variable-indigena/ (accessed January 18, 2025).

Evans, V. (2006). Lexical concepts, cognitive models and meaning-construction. Available at: https://philarchive.org/archive/MOLNLS#:~:text=Natural%20language%20ontology%20is%20aaccepts%20when%20using%20a%20language (accessed January 18, 2025).

Falola, T. (2013). Èṣù: Yoruba God Power and the Imaginative Frontiers. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Forero, E. A. S. (2012). Estudios para la paz, la interculturalidad y la democracia. Ra Ximhai 8, 17–37. doi: 10.35197/rx.08.01.e.2012.01.es

Fry, D. P., and Souillac, G. (2021). Peaceful societies are not utopian fantasy. They exist. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/2021/03/peaceful-societies-are-not-utopian-fantasy-they-exist/ (accessed January 14, 2025).

Fry, D. P., Souillac, G., Liebovitch, L., Coleman, P. T., Agan, K., Nicholson-Cox, E., et al. (2021). Societies within peace systems avoid war and build positive intergroup relationships. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8:17. doi: 10.1057/s41599-020-00692-8

Godey, B., Pederzoli, D., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., Wiedmann, K. P., and Hennigs, N. (2013). A cross-cultural exploratory content analysis of the perception of luxury from six countries. J. Product Brand Manag. 22, 229–237. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-02-2013-0254

Haarstad, H., and Andersson, V. (2009). Backlash reconsidered: neoliberalism and popular mobilization in Bolivia. Lat. Am. Polit. Soc. 51, 1–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-2456.2009.00062.x

Hammond, J. L. (2011). Indigenous community justice in the Bolivian constitution of 2009. Hum. Rights Q. 649–681. doi: 10.1353/hrq.2011.0030

Harper, D. (2025). Etymology of *pag-. Online Etymology Dictionary. Available at: https://www.etymonline.com/word/*pag- (accessed September 20, 2024).