- Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences, and Theology, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany

The relationship between religion and democracy is ambivalent, with religion either able to strengthen democracy or significantly threaten it. With the “digital turn” in religion and the growing prevalence of spiritual tech—such as digital religious platforms, apps specialized on spirituality, and religious chatbots powered by Artificial Intelligence—this relationship becomes even more intricate. In this Perspective, I will explore the fundamental relationship between religion and democracy and then outline the different ways in which spiritual tech can influence democratic processes. I will demonstrate that there are currently no legitimate national or international measures in place to limit the democracy-threatening potential of spiritual tech. To address this gap, I propose introducing a structured review process designed to actively promote spiritual tech that supports and strengthens democratic values.

1 Introduction

Spiritual tech is on the rise: From specialized apps and digital platforms to religious chatbots powered by Artificial Intelligence (AI) to robotic devices designed to participate in religious practices and address the spiritual needs of individuals, there is a growing number of digital tools that facilitate religious communication, support individuals in practicing their faith, and even contribute to religious education. Theologically, there have been repeated calls for some kind of “theological quality test” for spiritual tech, to ensure that such tools do not make statements that are theologically questionable or even problematic, and that they do not convey false notions of religion. A recent example is Father Justin, a GPT-based virtual avatar developed by the media ministry Catholic Answers. Designed to resemble a priest, Father Justin was created to answer users’ questions in the manner of a real Roman Catholic priest. However, when Father Justin responded to some user inquiries by suggesting, for instance, that baptism could be performed with Gatorade in an emergency – along with other questionable statements – it generated animated debate and controversy within the religious community (Tretter and Brand, 2024; Dela Cruz, 2024). This controversy, alongside others involving religious avatars – such as an AI-generated Jesus @ask_jesus livestreaming on Twitch and answering its viewers’ questions (Green, 2023) – led to calls for stricter theological oversight of spiritual tech, or, more radically, a complete ban on so-called “religious AI” or spiritual tech altogether (Rebecca, 2024).

In this contribution, I will build on the existing discussions surrounding spiritual tech, but take the conversation a step further. I will argue that it is not only essential to regulate spiritual tech from a theological perspective, but also from a democratic one.

To develop this argument, I will proceed as follows: First, I will examine the complex relationship between religion and democracy, emphasizing that while religion can bolster democracy, it can also threaten the very foundations on which democracy is built. Second, I will outline some legal and political measures currently in place to mitigate the democracy-threatening potentials of religion. Third, I will demonstrate how spiritual tech contributes to the dissemination of content that might threaten democracy and show that there are currently no effective mechanisms to prevent or mitigate these risks. Finally, I will suggest a possible way to regulate spiritual tech to ensure it has a positive impact on democracy.

The considerations presented here are not based on empirical research into the relationship between spiritual tech and democracy, but rather on philosophical, theological, and political-theoretical reasoning. Their goal, in the sharp and punchy style of a Perspective, is to identify an existing danger and to develop initial suggestions toward a process that could contain it before it becomes (an even more) widespread issue.

2 The ambivalent relationship between religion and democracy

Religion and democracy have an ambivalent relationship with one another. On the one hand, religion can safeguard democracy and encourage citizens to participate in democratic processes. This happens, for instance, when churches commit to democratic values and actively urge their members to engage in democratic participation. One notable example is the so-called “Memorandum on Democracy” published by the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) in 1985, in which the church explicitly endorses democracy, calls on its members to take responsible part in democratic processes, and condemns political systems that are authoritarian or that restrict people’s democratic rights and freedoms (EKD, 1990).

From the Roman Catholic perspective, Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Centesimus Annus can be considered. In it, the former pope explicitly advocates for democracy as a form of government, emphasizing that it aligns with Christian principles as it is based on respect for human dignity, human rights, and freedom (Paul, 1991). Another important example is the pastoral constitution Gaudium et Spes, adopted during the Second Vatican Council, which highlights the importance of political participation and emphasizes the responsibility of believers to engage in public life to promote the common good (Pastoral Constitution, 1965).

These church positions are reinforced by insights from political theology (Rodríguez, 2020), public theology (Kim and Day, 2017), and theological political ethics (Anselm, 2015), all of which similarly affirm the value of democracy and urge believers, as citizens, to take responsibility by participating in the democratic process and actively shaping the common good.

However, the contribution that religion can make to democracy is not only emphasized by churches or theologians; it is also recognized outside of religious and theological circles. For example, the prominent German constitutional and administrative law scholar Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde writes in his widely cited essay The Rise of the State as a Process of Secularization from 1967: “The liberal, secularized state is sustained by conditions it cannot itself guarantee. That is the great gamble it has made for the sake of liberty” (Böckenförde, 2021, p. 167). While there are still ongoing discussions about this statement, that became known as the “Böckenförde dictum”, and how to exactly understand it (Große Kracht and Große Kracht, 2014; Sauer, 2023; Palm, 2013), there is broad consensus that the „conditions it [the liberal, secularized state] cannot itself guarantee” include certain core attitudes among its citizens. These include, as also emphasized by other thinkers, a certain, though never uncritical, level of trust in democratic institutions and elected (Taylor, 2018; Warren, 1999), the awareness that one is not an isolated individual but part of a social entity and dependent on others (Putnam, 2000), the recognition that all people possess equal dignity, as well as a sense of responsibility and willingness to contribute to the shaping of society (Sennett, 2012), work in solidarity toward the common good (Reich, 2018), and care for the well-being of others (Nussbaum, 2011). Religious and theological interpretations further emphasize that religions play a significant role in fostering these attitudes, thereby strengthening several conditions without which democratic states could not exist – making religion important even in secular states (Große Kracht and Große Kracht, 2014).

Even positions that can be categorized as more skeptical of religion’s role within democracies cannot deny its potential to promote democracy. One example is Jürgen Habermas, who, in his writings on democracy and the public sphere, clearly argues that public discussions in democracies should be based on reason–meaning that the best argument should prevail, and positions that cannot be understood universally or are based on assumptions not shared by all should not be valid in democratic debates (Habermas, 2011; Habermas, 1984). Due to these demands, and because he recognizes public discussions as one of the cornerstones of democracy, the early Habermas is highly skeptical when it comes to religion’s role within democracies. However, in his later works – as he notes in his own biographical reflections (Habermas, 2024b)–Habermas increasingly highlights how religions can foster attitudes essential to democracy’s flourishing (Habermas, 2023, 2024a; Müller-Doohm et al., 2024). As an example, he refers to “egalitarian universalism” (Habermas, 2015, 2002, 2023, 2024a), the belief that all people possess equal, inviolable dignity, which was largely shaped by Christianity. A similar, position toward religion is taken by John Rawls. He argues that religion is a private matter and, as such, should initially have no role in public deliberations about societal structures, which ought to rely exclusively on principles acceptable to all (Rawls, 1999; Rawls, 2001). Nevertheless, he also highlights that religious convictions might contribute to reinforcing certain attitudes important for social cohesion. From their particular perspectives, religious beliefs can, for instance, help individuals develop a foundational conviction in the equal worth of all people–a belief that is not only religiously highly significant but also democratically indispensable (Rawls, 2005).

On the other hand, religion can also pose a threat to democracy; there are plenty of examples. In its most extreme and direct form, this happens when religious beliefs are pitted against existing democratic laws or prevailing ideas of coexistence, such as when liberal achievements like gender equality and the non-discrimination of queer people are branded as violations of divine commandments, and efforts are mobilized to abolish them (Machmer and Gogoll, 2024; Lo Mascolo, 2023). While it is unnecessary to delve too deeply into specific examples – and risk granting them more attention than necessary – a notable case might be the Aktion für Ehe and Familie – DemoFürAlle (commonly referred to as Demo für alle, “demo for all”). Since 2014, this movement has organized protests in Germany advocating for what they term the “protection of the traditional family” and opposing initiatives such as gender diversity education, marriage equality, and LGBTQ+ rights in schools. Although not a religious organization per se, the movement regularly frames its opposition with religious references to divine commandments, its protests are frequently associated with the Christian Right (Strube, 2023), and, according to its own statements (Demo für alle, 2024), involve collaboration with conservative religious organizations such as the Forum Deutscher Katholiken (“Forum of German Catholics”) – an association that serves as a more conservative counterpart to the officially Roman Catholic-affiliated Zentralkomitee der deutschen Katholiken (“Central Committee of German Catholics”), and that is often characterized as right-wing (Wirsching, 2019).

In a less extreme and more indirect form, religions threaten democracy when, instead of strengthening the conditions that Böckenförde referred to, they preach, for example, an exaggerated individualism, where everyone is focused solely on their personal salvation, and, at best, the well-being of those who share the same faith but ignores every other person as well as the common good as a whole. Religious communities that encourage this kind of “social egoism” (Kobyliński, 2021) or foster individualistic or tribalistic attitudes can pose significant challenges to democracy. As Bowler (2013) has shown in the American context, this is particularly likely to occur in settings where a so-called “prosperity gospel” (Coleman, 2016) is preached; as well as where religion reinforces a mindset of “I am my own neighbor” or “us against the rest.” These tendencies undermine the democratic values of social cohesion and mutual responsibility, weakening individuals’ sense of responsibility in shaping society (Calhoun et al., 2022).1

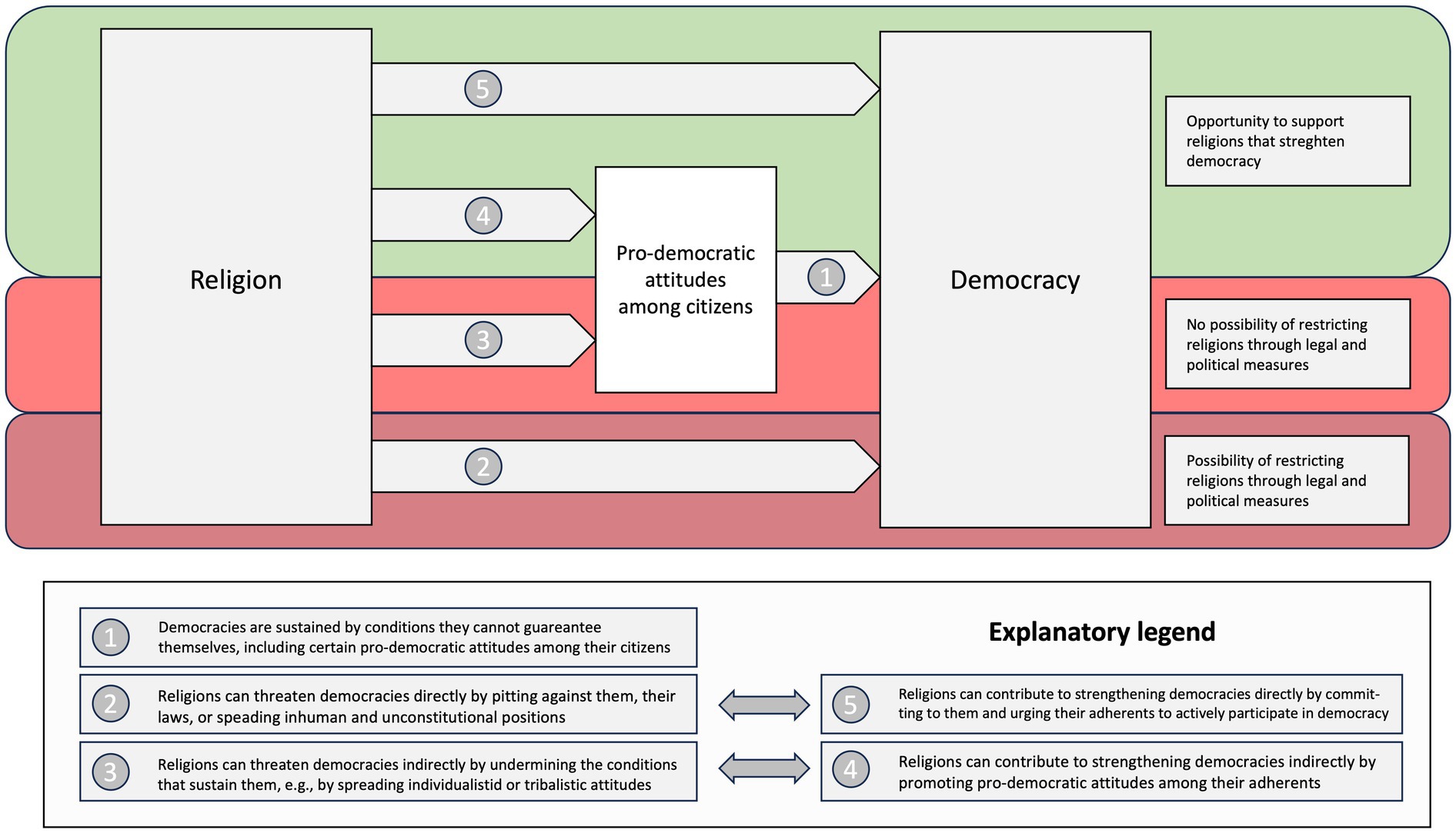

To summarize the argument of this section: religion is highly ambivalent: it has the potential to both support and threaten democracy. It is crucial to stress that any religion can adopt forms that either support or endanger democracy. That is why sweeping prejudices such as “Islam is anti-democratic” or “Christianity is pro-democracy” must be urgently avoided. Rather than depending on the religion itself, the question of whether it supports democracy hinges on which attitudes are conveyed in the name of that religion. An illustration of the ambivalent relationship between religion and democracy, as well as the possibilities for legal and political intervention in this relationship can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Illustration of the ambivalent relationship between religion and democracy depicting the ways in which religion can either strengthen or threaten democracy, including the opportunities for legal and political intervention (created by the author).

3 Measures to contain the democracy-threatening potential of religion

In light of the insights into the relationship between democracy and religion, it proves to be extremely important from a democratic perspective to “guide” religions in ways that are not anti-democratic, but ideally convey attitudes that promote democracy. For the sake of democracy, therefore, some level of control over religion seems necessary. This control can theoretically be exercised on a micro level by individuals who work to promote democratic-friendly expressions of religion and speak out against anti-democratic ones. In practice, however, the actual influence of individuals—unless they are influential pastors or people with a large following—is quite limited. That is why this control can more effectively be exercised on a macro level through political and legal measures, which can take one of two forms: restrictive or supportive.

Many countries have constitutional provisions that guarantee their citizens the right to religious freedom—meaning the fundamental right to practice their faith freely, gather with fellow believers, celebrate religious services and festivities, and engage in religious education, without interference from the state or others (Ahdar and Leigh, 2013; Eisgruber and Sager, 2007). This “right to freedom of religion” is even recognized in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 2024). Still, many democratic nations reserve the right to limit religious freedom and restrict certain religious practices when they infringe on individuals’ fundamental rights, or to ban entire religious groups if they exhibit traits that are clearly inhumane, unconstitutional, or linked to terrorism (Ahdar and Leigh, 2013).

A recent example is the Islamic Center Hamburg (“Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg”), which was banned in July 2024 by Germany’s Federal Ministry of the Interior, citing that it had “acted against the constitutional order and the principles of international understanding” (Bundesministerium der Justiz, 2024, translated by the author). However, due to the high legal threshold for such actions, in liberal democratic nations, such measures are only to be used as a last resort in extreme cases; which is why such bans are relatively rare. In less severe instances, where religions “only” erode the conditions sustaining democracy by, for instance, promoting individualistic or tribalistic attitudes, such bans cannot be imposed.

A less invasive approach to proactively discouraging religions that pose a threat to democracy from gaining influence is to support expressions of religion that foster democracy-friendly attitudes and contribute to the common good. This support can take different forms. Beyond tax benefits for religious communities, which is a highly complex and contested issue itself (Zelinsky, 2017), religious events can receive state subsidies. For example, the 102nd German Catholic Convention in Stuttgart in 2022 and the 38th German Protestant Church Assembly in Nuremberg in 2023 both featured religious and cultural activities alongside political forums and discussions that promoted democratic attitudes and civic engagement. Thanks to this democratic and public-interest focus, both events received millions of euros in funding from federal, state, and municipal governments (Bundestag, 2023; dpa, 2023). Additionally, religious communities that promote democracy and foster pro-democratic attitudes may be permitted to offer religious education in public schools (Eisgruber and Sager, 2007). To ensure the democratic orientation of this education, the curriculum is usually subject to state oversight, and teachers are often trained in theological faculties at state universities. If training occurs at private or church institutions, states ultimately decide whether graduates can teach in public schools or not.

Providing such financial support for events can help amplify the social influence of religions with democracy-friendly perspectives. Additionally, by offering religious education in schools, it can be made sure that the religion taught at an early age fosters democratic attitudes. In this way, supportive measures can be used to cultivate the conditions that democracies rely on.

4 Spiritual tech, threats to democracy, and the failure of established control mechanisms

As the previous section demonstrates, there are established ways in the analog world to exert control over religions at a macro level, helping to ensure that they promote attitudes beneficial to democracy. However, with the “digital turn” in religion—where religious exchange, education, and practice increasingly shift from the physical to the digital sphere (Campbell and Bellar, 2023)—a wide array of spiritual tech has emerged, enabling individuals to engage with their faith in new ways. This includes apps featuring sacred texts like the Quran, the Bible, or Buddhist Sutras in multiple translations, as well as apps that assist users in formulating prayers, planning pilgrimages, meditating, or even confessing sins (Campbell et al., 2014). It also extends to online forums and digital platforms for discussing religious topics (Hutchings, 2015) and virtual environments within video games (Campbell and Grieve, 2014; Bosman, 2019) or custom-designed VR worlds, where people can gather to practice religious rituals or attend services (Jun, 2020). Additionally, there are AI-driven chatbots designed to assist individuals with religious questions or accompany them on their spiritual journey (Trothen, 2022), often explicitly trained on religious datasets, capable of answering users’ questions based on the Quran2, the Bible3, or the Torah and Midrash4. Finally, there are even robotic applications intended to support religious practices and address spiritual needs (Simmerlein and Tretter, 2024a, 2024b).

One key challenge with spiritual tech lies in its potential to disseminate content that is either highly problematic and directly threatens democracy or that subtly undermines pro-democratic attitudes, posing an indirect threat to democracy. As the remainder of this section will demonstrate, no effective mechanisms currently exist to prevent or mitigate these risks.

While there are legal regulations at both national and international levels that try to counter the dissemination of inhumane, inflammatory, or discriminatory content online (Gorwa, 2024), the sheer number of (religious) hate posts on major social media platforms highlights how inconsistently these rules are enforced at the moment (Di Fátima, 2023). Among the more extreme examples of religious posts of this kind are, as highlighted by Duile (2018), the social media activities of the Front Pembela Islam in Indonesia, where, in the name of religion, mobilization, intimidation, and threats are directed against specific targets, such as leftist political organizations, nightclubs, and events or venues associated with LGBT+ communities. While inflammatory and discriminatory content like this, threatening basic democratic principles, is, thankfully, often swiftly removed, other content that subtly undermines democratic attitudes and values, and poses an indirect threat to democracy often goes unchecked. Examples include content, sometimes in the form of memes (Campbell and Sheldon, 2021), oftentimes rooted in right-wing evangelical or white Christian ideologies, that mocks political leaders, thus gradually undermining trust in democratically elected representatives (Jones, 2020), or posts that use the Bible or Christian symbols (McSwiney et al., 2021), to spread discord or conspiracy narratives (Diaz Ruiz and Nilsson 2022), or to propagate toxic masculinity and anti-feminist views, particularly within “incel culture” (Ging, 2017).

The same challenges arise in virtual spaces. While most online forums, video games, and VR environments have implemented content policies or codes of conduct, these suffer from two significant flaws: enforcement is often inconsistent, and efforts primarily focus on the most extreme and directly harmful content, leaving content that “only” undermines democratic attitudes largely unaddressed. A notable example of the limitations of such regulations – even in curbing overtly problematic content—is the so-called “Vatican Minecraft Server,” hosted by a Catholic priest with the aim of fostering an open online community based on Christian values (Walters, 2019). To ensure this vision, the server established rules and employed moderators to enforce them, prohibiting insults, toxicity, discrimination, and similar behavior. However, soon after its launch, the server faced massive DDoS attacks (Meisenzahl, 2019), and became a target for “trolls” (Galitski, 2019), i.e., players who intentionally violated the rules by posting slurs, toxic or hate-inciting messages in the server’s chat, and even constructing swastikas in the game environment. Videos of these acts were often shared on platforms like YouTube.

Religious apps, like all other apps, are—at least theoretically—subject to strict content reviews before being made available in app stores. These reviews aim to ensure compliance with guidelines and can, where necessary, result in age restrictions or outright rejection. However, as numerous negative cases demonstrate, these checks are often not thorough enough, sometimes even allowing religious apps in app stores that contain severe security flaws and malware (Hodge, 2019) or highly problematic content (Pellot, 2014). A notable example of an app disseminating content incompatible with democratic attitudes and values is the app Living Hope Ministries, as it depicted being gay as an “addiction,” “sickness,” and “sin” and disseminated much more discriminatory content against queer and trans individuals, even to the point of suggesting conversion therapies to some people (Griffith, 2018). Despite these clear guideline violations, the app remained available in app stores for a significant period before being removed—first by Apple and later by Google—after multiple complaints (Wood, 2019). The fact that (religious) apps with such overtly problematic content, directly contradicting fundamental democratic principles, can pass these quality checks and remain available for extended periods suggests that apps which “only” disseminate content undermining pro-democratic attitudes and posing an indirect threat to democracy are even less likely to be identified or removed during these checks.

Last but not least, regulating AI-driven religious chatbots and applications presents unique challenges. Their reliance on statistical models and learning capabilities makes oversight even more difficult than regulating the content spread via apps, social media, or virtual spaces, and heightens the risk of statements being generated that are not only deeply problematic but may also exhibit democracy-threatening tendencies. A notable example is a group of Indian religious chatbots, including Gita-AI, GitaGPT, Gita Chat, and Ask Gita. Based on an earlier version of ChatGPT and the Bhagavad Gita—a text depicting Krishna’ s teachings to Arjuna—there have been cases when these systems presented unfiltered interpretations of controversial passages. For example, Krishna’s urging of Arjuna to wage war against his family is presented without critique or contextualization. Unlike human preachers who historically-critically interpret and critique such violent messages thoughtfully, these chatbots reproduced the content straightforward, sometimes endorsing violence by advising users that “it’s OK to kill someone if it’s your dharma, or duty” (Shivji, 2023). It’s just this kind of uncritical and overly literal reproduction of historical religious texts that, as Iblher (2023) notes, can quickly become problematic. Although modern (religious) AI chatbots and applications are typically equipped with content filters to prevent such violence-promoting or explicitly anti-democratic statements, these safeguards can often be bypassed—sometimes easily, sometimes with more effort—through methods like GPT-hacking or jailbreaking (French, 2024; Milpetz, 2025). Furthermore, these content filters—for good reason, as such restrictions could quickly violate the right to free speech—do not address subtler forms of problematic content that, for instance, promotes attitudes such as exaggerated individualism and materialism, that might eventually undermine social cohesion and indirectly endanger democracy. An example of exactly this type of overly individualistic and materialistic religious content is promoted by @beliverdaily on TikTok5, an AI-generated influencer modeled after a stereotypical white Jesus, that promises “divine blessings and many worldly comforts” (Dean, 2023), and whose clips have garnered over 50 million views and more than 9 million likes (as of January 3, 2025). Similar content tendencies can be observed in other AI-generated religious influencers such as @ask_jesus6, which streams live on Twitch 24/7, responding to user inquiries (Green, 2023). Unlike religious AI influencers such as @believerdaily, whose contents are pre-produced and shared on social media platforms, @ask_jesus’ content is generated in real-time using chatbots, visualized with AI-powered video generation, and streamed live without consistent human oversight. This lack of review significantly heightens the risk of problematic content or anti-democratic material being disseminated.

5 Discussion

The previous section demonstrated how spiritual tech can contribute to the dissemination of content that poses a threat to democracy—either by being explicitly inhumane or unconstitutional, or by promoting attitudes such as extreme individualism and materialism that erode the values and attitude crucial to sustaining democracy. While there are national and international regulations, as well as content policies and codes of conduct, that prohibit the dissemination of explicitly inhumane or unconstitutional content, which, to be honest, could and should be more effectively enforced to counter its spread, including through spiritual tech, there are no mechanisms in place to address content that undermines pro-democratic attitudes or poses indirect threats to democracy. However, this situation is not much different from the “analog” world. As previously outlined, only religious groups posing a direct threat to democracy through unconstitutional or inhumane positions can be banned; religious communities that indirectly undermine democracy by eroding the conditional attitudes necessary for its “survival” cannot—rightfully—be banned.

In the analog world, subsidies can be employed to ensure that pro-democratic expressions of religion gain more influence than those that indirectly undermine democracy. A similar approach might be applied to the digital realm with respect to spiritual tech. For instance, spiritual tech that actively contributes to promoting democratic values and fostering pro-democratic attitudes could receive targeted support. While a detailed plan for implementing this cannot be provided here, a general framework could follow a three-step process:

1. Developers of spiritual tech could voluntarily submit their plans or completed projects through a dedicated online application system. This system would request key details and allow for the submission of an early version of the spiritual tech to a specifically designated governmental institution. While this institution would need to be established, it could be housed within existing organizations.

2. These submissions would then undergo a rigorous review by official, potentially state-appointed evaluators from fields such as theology or religious studies, law, social sciences, and other relevant disciplines. The review would evaluate the contents promoted by the tech, its anticipated impact on democracy, and the robustness of its safeguards against manipulation, based on established criteria and specifications.

3. If the evaluation is positive, developers would receive financial support, be reimbursed retroactively, or have their applications endorsed and potentially promoted by government bodies.

Admittedly, while comparable funding processes already exist in some countries, such as Germany, in the realm of political education (bpb, 2024), introducing a similar review process for spiritual tech still seems, at least for now, somewhat utopian. Such an initiative would require both institutional resources to establish the necessary structures and significant effort to design a review process that is consistent and transparent. These efforts would involve considerable costs–even if existing funding programs were expanded to include spiritual tech. Moreover, it is uncertain whether the initiative would yield the desired outcomes or, conversely, produce unintended consequences. For example, persons might deliberately avoid officially-reviewed and state-sponsored spiritual tech, much like some groups of people shun state-supported media. However, what remains clear is that, from both a theological and democratic theory perspective, it’s crucial to keep a close eye on spiritual tech and discuss how to ensure it does not just avoid theologically problematic statements but also steers clear of undermining the conditions that are essential for a healthy democracy.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

MT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Fiona Bendig and Lena Völkel for heir valuable feedback and helpful comments on the manuscript. OpenAI’s ChatGPT, version 4o, was used to refine the text linguistically.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^At first glance, the indirect form of democracy being threatened by religion may seem much less harmful, as it does not directly incite opposition against groups of people or democracy itself. However, it is precisely in this subtlety that a danger lies, because its democracy-threatening nature is not always immediately recognized, which may allow this form to spread more easily.

References

Ahdar, R., and Leigh, I. (2013). Religious freedom in the Liberal state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anselm, R. (2015). “Politische Ethik” in Handbuch der Evangelischen Ethik. eds. W. Huber, T. Meireis, and H.-R. Reuter (München: C.H.Beck), 195–263.

Böckenförde, E.-W. (2021). Religion, law, and democracy. selected writings. Edited by Martin Loughlin, John P. McCormick, and Neil Walker. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bosman, F. G. (2019). Gaming and the divine. A new systematic theology of video games. London, New York: Routledge.

Bowler, K. (2013). Blessed. A history of the American prosperity gospel. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

bpb. (2024). Modellförderung. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Available at: https://www.bpb.de/die-bpb/foerderung/foerdermoeglichkeiten/140010/modellfoerderung/#node-content-title-0 (Accessed September 10, 2024)

Bundestag, Deutscher. (2023). Sachstand: Finanzierung von Kirchentagen. Deutscher Bundestag. Wissenschaftliche Dienste. https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/983278/9e3fc1c625d9ec79c2f77bd18daa07d0/WD-10-041-23-pdf.pdf (Accessed September 6, 2024)

Bundesministerium der Justiz, B. (2024). Bekanntmachung eines Vereinsverbots gegen die Vereinigung Islamisches Zentrum Hamburg e.V. (IZH). Bundesanzeiger, https://www.bundesanzeiger.de/pub/publication/lrXTsh2FSD2lgjw7RYW/content/lrXTsh2FSD2lgjw7RYW/BAnz%20AT%2024.07.2024%20B1.pdf?inline (Accessed September 6, 2024)

Calhoun, C., Gaonkar, D. P., and Taylor, C. (2022). Degenerations of democracy. Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press.

Campbell, H. A., Altenhofen, B., Bellar, W., and Cho, K. J. (2014). There’s a religious app for that! A framework for studying religious mobile applications. Mobile Media Commun 2, 154–172. doi: 10.1177/2050157914520846

Campbell, H. A., and Grieve, G. P. (2014). Playing with religion in digital games. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Campbell, H. A., and Sheldon, Z. (2021). Religious responses to social distancing revealed through memes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Religions 12. doi: 10.3390/rel12090787

Coleman, S. (2016). “The prosperity gospel. Debating Charisma, controversy and capitalism” in Handbook of global contemporary Christianity. Movements, institutions, and allegiance. ed. S. Hunt (Leiden, Boston: Brill), 276–296.

Dean, B. (2023). A TikTok Jesus promises divine blessings and many worldly comforts. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/a-tiktok-jesus-promises-divine-blessings-and-many-worldly-comforts-213130 (Accessed January 3, 2025)

Dela Cruz, J. (2024). AI priest gets demoted after saying babies can be baptized with Gatorade, making other wild claims. Tech Times. Available at: https://www.techtimes.com/articles/304222/20240502/ai-priest-demoted-saying-babies-baptized-gatorade.htm (Accessed September 9, 2024)

Demo für alle. (2024). Über uns. https://demofueralle.de/ueber-uns/ (Accessed January 21, 2025).

Diaz Ruiz, C., and Nilsson, T. (2022). Disinformation and Echo chambers: how disinformation circulates on social media through identity-driven controversies. J. Public Policy Mark. 42, 18–35. doi: 10.1177/07439156221103852

dpa. (2023). “Jetzt ist die Zeit”. Evangelischer Kirchentag hat begonnen. Süddeutsche Zeitung. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/glauben-jetzt-ist-die-zeit-evangelischer-kirchentag-hat-begonnen-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-230607-99-967631 (Accessed September 6, 2024)

Duile, T. (2018). Islam, politics, and cyber tribalism in Indonesia: a case study on the front Pembela Islam. Int. Q. Asian Stud. 48, 249–272. doi: 10.11588/iqas.2017.3-4.7443

Eisgruber, C. L., and Sager, L. G. (2007). Religious freedom and the Constitution. Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press.

EKD (1990). Evangelische Kirche und freiheitliche Demokratie. Der Staat des Grundgesetzes als Angebot und Aufgabe. Eine Denkschrift der Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland. 4th Edn. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus Gerd Mohn.

French, L. (2024). ChatGPT jailbreak prompts proliferate on hacker forums. SCMedia. https://www.scmagazine.com/news/chatgpt-jailbreak-prompts-proliferate-on-hacker-forums (Accessed September 9, 2024)

Galitski, K. (2019). Vatican’s Minecraft server is being targeted by trolls and DDoS attacks. The Gamer. https://www.thegamer.com/vatican-minecraft-server-targeted-trolls-ddos-attacks/ (Accessed January 3, 2025)

Ging, D. (2017). Alphas, betas, and Incels: theorizing the masculinities of the Manosphere. Men Masculinities 22, 638–657. doi: 10.1177/1097184X17706401

Gorwa, R. (2024). The politics of platform regulation. How governments shape online content moderation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Green, A. (2023). AI Jesus is Here and He’s streaming 24/7. Eternity News. Available at: https://www.eternitynews.com.au/christian-living/ai-jesus-is-here-and-streaming/ (Accessed January 3, 2025)

Griffith, J. (2018). Apple pulls religious app accused of portraying homosexuality as ‘sickness’ and a ‘sin’. NBC News. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/apple-pulls-religious-app-accused-portraying-homosexuality-sickness-sin-n951361 (Accessed January 2, 2025)

Große Kracht, H.-J., and Große Kracht, K. (2014). Religion – Recht – Republik. Studien zu Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde. Paderborn: Schöningh.

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action, vol. 1 & 2. Translated by Thomas McCarthy. Boston: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (2002). Religion and Rationality. Essays on Reason, God, and Modernity. Edited by Eduardo Mendieta. Cambridge, Oxford: Polity.

Habermas, J. (2011). The structural transformation of the public sphere. An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Translated by Thomas Burger. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Habermas, J. (2015). Between naturalism and religion. Philosophical essays. Translated by Ciaran Cronin. Cambridge: Polity.

Habermas, J. (2023). Also a History of Philosophy, vol. 1. The Project of a Genealogy of Postmetaphysical Thinking. Translated by Ciaran Cronin. Cambridge: Polity.

Habermas, J. (2024a). Also a History of Philosophy, vol. 2. The Occidental Constellation of Faith and Knowledge. Translated by Ciaran Cronin. Cambridge: Polity.

Habermas, J. (2024b). Es musste etwas besser werden…. Gespräche mit Stefan Müller-Doohm und Roman Yos. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Hodge, R. (2019). Religious apps with sinful permissions requests are more common than you think. cnet. Available at: https://www.cnet.com/tech/services-and-software/why-so-many-android-christian-apps-have-unholy-privacy-policies/ (Accessed January 2, 2024).

Hutchings, T. (2015). “Christianity and digital media” in The changing world religion map: Sacred places, identities, practices and politics. ed. S. D. Brunn (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands), 3811–3830.

Iblher, P. (2023). Gott aus der Maschine – Wie bizarr oder gefährlich ist religiöse KI? Digital Human Rights. https://digitalhumanrights.blog/gott-aus-der-maschine-wie-gefaehrlich-ist-religioese-ki/ (Accessed January 2, 2025)

Paul, J. (1991). Centesimus Annus. The Holy See. https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_01051991_centesimus-annus.html (Accessed September 9, 2024)

Jones, R. P. (2020). White too long. The legacy of white supremacy in American Christianity. New York, London: Simon & Schuster.

Jun, G. (2020). Virtual reality church as a new mission frontier in the Metaverse: exploring theological controversies and missional potential of virtual reality church. Transformation 37, 297–305. doi: 10.1177/0265378820963155

Kobyliński, A. (2021). Ethical aspects of the prosperity gospel in the light of the arguments presented by Antonio Spadaro and Marcelo Figueroa. Religions 12. doi: 10.3390/rel12110996

Lo Mascolo, G. (2023). The Christian right in Europe. Movements, networks, and denominations, political Science. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Machmer, K, and Gogoll, M. (2024). Rechte Politik im religiösen Gewand. Zeit Online. https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/zeitgeschehen/2024-06/rechtsextremismus-religion-christentum-citizengo-abtreibung (Accessed December 13, 2024)

McSwiney, J., Vaughan, M., Heft, A., and Hoffmann, M. (2021). Sharing the hate? Memes and transnationality in the far right’s digital visual culture. Inf. Commun. Soc. 24, 2502–2521. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2021.1961006

Meisenzahl, M. (2019). The Vatican started a ‘Minecraft’ server and it was immediately attacked, according to the priest that set it up. Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/minecraft-server-for-vatican-hit-possible-ddos-attack-priest-says-2019-12 (Accessed January 3, 2024)

Milpetz, S. (2025). Jailbreak: Einfacher Hack kann selbst fortgeschrittene Chatbots knacken. https://t3n.de/news/jailbreak-einfacher-hack-kann-selbst-fortgeschrittene-chatbots-knacken-1666011/ (Accessed January 4, 2025)

Müller-Doohm, S., Rapic, S., and Wesche, T. (2024). Vernünftige Freiheit. Beiträge zum Spätwerk von Jürgen Habermas. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Nussbaum, M. (2011). Creating capabilities. The human development approach. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Palm, J. (2013). Berechtigung und Aktualität des Böckenförde-Diktums. Eine Überprüfung vor dem Hintergrund der religiös-weltanschaulichen Neutralität des Staates. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

Pastoral Constitution. (1965). Gaudium et spes. The Holy See. Available at: https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html (Accessed September 9, 2024)

Pellot, B. (2014). 5 religious iPhone apps banned from the app store. Available at: https://religionnews.com/2014/01/09/5-religious-smartphone-apps-banned-app-store/ (Accessed January 2, 2025)

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone. The collapse and revival of American community. New York, London: Simon & Schuster.

Rebecca, B. W. (2024). The rise and fall of ‘Father Justin’ highlights Catholic sexism. National Catholic Reporter. https://www.ncronline.org/opinion/guest-voices/rise-and-fall-father-justin-highlights-catholic-sexism (Accessed September 9, 2024)

Sauer, E. (2023). Freiheit als Wagnis. Eine sozialethische Studie zum Recht auf Religionsfreiheit unter der Berücksichtigung ausgewählter Werke von Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde. Available at: https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/31457/ (Accessed January 21, 2025).

Sennett, R. (2012). Together. The rituals, pleasures and politics of co-operation. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

Shivji, S. (2023). India’s religious chatbots condone violence using the voice of god. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/india-religious-chatbots-1.6896628 (Accessed January 2, 2025)

Simmerlein, J., and Tretter, M. (2024a). Robots in religious practices: a review. Theol. Sci. 22, 255–273. doi: 10.1080/14746700.2024.2351639

Simmerlein, J., and Tretter, M. (2024b). What about spiritual needs? Care robotics and spiritual care. Front. Robot. AI 11. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2024.1455133

Strube, S. A. (2023). “The Christian right in Germany,” in The Christian right in Europe. Movements, networks, and denominations. ed. I. P. Science (Bielefeld: Transcript), 213–230.

Tretter, M, and Brand, L. (2024). Father Justin und die Regeln des Internet. Available at: https://y-nachten.de/2024/05/die-regeln-des-internet/ (Accessed May 17, 2024)

Trothen, T. J. (2022). Replika: spiritual enhancement technology? Religions 13. doi: 10.3390/rel13040275

United Nations. (2024). Universal declaration of human rights. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (Accessed September 9, 2024)

Walters, M. (2019). The Vatican has its very own Minecraft server. Available at: https://www.thegamer.com/vatican-city-minecraft-server/ (Accessed January 3, 2025)

Wirsching, D. (2019). So hetzen rechte Katholiken – auch bei uns in der Region. Augsburger Allgemeine. Available at: https://www.augsburger-allgemeine.de/politik/Rechte-Katholiken-So-hetzen-rechte-Katholiken-auch-bei-uns-in-der-Region-id54693526.html (Accessed December 13, 2024).

Wood, C. (2019). Google deletes ‘conversion therapy’ app savaged by the LGBTQ community. Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/google-deletes-living-hope-ministries-conversion-therapy-app-2019-3 (Accessed January 2, 2025)

Keywords: religion, religious tech, theology, ethics, artificial intelligence, politics, chatbots

Citation: Tretter M (2025) Spiritual tech and democracy: initial ethical reflections. Front. Polit. Sci. 7:1494894. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2025.1494894

Edited by:

Oliver Fernando Hidalgo, University of Passau, GermanyReviewed by:

Pauline Cheong, Arizona State University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Tretter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Max Tretter, bWF4LnRyZXR0ZXJAZmF1LmRl

Max Tretter

Max Tretter