94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Polit. Sci., 03 April 2025

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 7 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2025.1404205

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Recent and Contemporary Coups d'Etat in Sub-Saharan Africa: Ideology, Political Strategy, and Popular MobilizationView all articles

The African Union and its regional integration bodies have experience a long tradition of coups d’état perpetrated in their member states. Aimed at democratizing the continent, these organizations have adopted democratic norms and values that prohibit coups d’état, to the extent that today it is possible to outline a mosaic of democratic norms and institutional mechanisms designed to achieve this purpose in Africa, but with mixed results. This paper sets out to analyze the various causes and obstacles that create a fertile ground for coups d’état to persist in some African states. It also identifies the institutional, decision-making and operational challenges that prevent the African Union and its regional organizations from successfully preventing or stemming out coups. Based on a historical, institutional and strategic analysis, the study reveals that the failure of democratic transition, and economic and security policies at national level has an impact at regional level. It also reveals that due to the lack of institutional autonomy and the predominance of sovereign choices made by some member states, the African Union and its regional organizations are powerless to address the situation of coups d’état. Although African Union and its regional integration organizations are trapped in a delicate situation regarding their institutional and functional autonomy, they would at least save their legitimacy vis-à-vis the citizens of their member states if they firmly condemned all forms of coups d’état including constitutional or electoral ones. Their effective actions against coups d’état remains dependent on the willingness of Member States to submit to Community norms and decisions without brandishing the attributes of sovereignty that would lead to exits from the regional organization. The Conferences of Heads of State, which are the decision-making and guiding bodies within the African Union and its regional integration organizations, will only be effective against coups d’état, and by extension the organizations themselves, if some of those chair them do not or have not remained in power through a coup d’état.

Many African states just a few years after independence, have been repeatedly hit by either military or constitutional coups d’etat (Jacquemot, 2023, pp. 4–17). Marc-André Boisvert provided a definition which, though limited regarding the nature of coups d’état in Africa, enables us to understand military coups or those perpetrated with the help of soldiers. He puts it that, “a military coup d’état is an unconstitutional change of power through violence or threat, perpetrated by a small group, unlike a revolution, which is carried out by a large group” (Boisvert, 2022, pp. 3–4; Bagayoko and Boisvert, 2022, pp. 1–5). Africa has also experienced several constitutional coups, which are generally the work of civilians in power. Unlike military coups, constitutional coups perpetrators do not use violence and threats, except when they go on to repress hostile demonstrations, but they do is manipulate the Constitution in a bid to run an undue third term or extend a second and last one (Mpiana, 2012, pp. 101–102).

Africa is equally hit by the challenges of transparent electoral processes. On the one hand, there are frequent electoral coups due to the lack of transparency of electoral processes drown out by all sorts of electoral frauds committed by ruling parties and their stranglehold on election institutions and on those in charge of validating the final results of elections after voting or following an electoral dispute. On the other hand, this opacity in electoral processes creates fertile ground for contested final results leading to post-electoral crises, human rights violations through the repression of opposition party’s demonstrations and sometimes to military putsches or armed conflicts (Ntwali, 2019, p.328–329; de Gaudusson, 2003, p. 1).

In this second and third category of coups d’état, weapons and the military are not the primary means used, even though they help to protect the institutions that validate fraudulent results, a third term or the extension of a second one. Parliamentary chambers, constitutional courts and election bodies are at the forefront of carrying out, if not facilitating, this other type of coups d’état in Africa (Ntwali, 2021, p. 16).

The three types of coup d’état started and are still being perpetrated in an African context marked by the failure of the first democratic experience of the 1960s, the coming to power of military regimes and their unprecedented longevity, and the failure of democratic consolidation after the democratization wave of the 1990s (Miscoiu, 2022, p.5; Miscoiu et al., 2015; Boshab, 2013, p. 280). The many factors that have contributed to the failure of democracy in Africa include, but not limited to the following:

• Institutional crises due to the failure of democracy and the imported State.

• The desire by some independence leaders to free themselves from the grip of the former colonial power.

• Economic and social crises.

• The desire by other international players to establish zones of influence on the African continent (the United States, Russia, China, etc.) (Ntwali, 2023a, pp. 1–9).

Whatever the case, these coups have been repeatedly perpetrated, some of them instigated by the former colonial power to overthrow an ally who is escaping their control, and many simply because some soldiers also long for power.

Military regimes are actually the ones which also took advantage of the Cold War to stay longer in power than in any African political history, and to embrace the policy of non-interference put forward by the Organization of African Unity in favor of newly independent member states (Mballa and Zogning, 2023, pp. 14–17; Balde, 2003, pp. 1–14; Borella, 1963, pp. 838–865). The African Union’s transition from non-interference to non-indifference in some specific situations, the adoption of the African Charter for Democracy and its dissemination within regional economic communities have not prevented the return of coups after the democratic wave of 1990 (Bako and Jobbins, 2022, pp. 16–18).

Due to the lack of the necessary financial autonomy which has a negative impact on their free decision-making capacity, African regional integration organizations are subject to external political influences which sometimes impose what they should do when any coup d’état occurs, giving no choice than to act in the interests of external players (Diallo, 2024). In this context dominated by a certain economic-political subservience of African regional integration organizations, ECOWAS has been largely accused by the military putschists of the Sahel for receiving injunctions to take economic and political sanctions against their respective states (Mali, Niger and Burkina Facon) (Diallo, 2024). The parent organization, the African Union, has not been spared such criticism, especially regarding the way France and certain African states (Nigeria, Cameroon, Congo, DRC and Rwanda) got involved and exerted their influence on the said organization which was supposed to strongly condemn Mahamat Déby Itno son’s constitutional coup d’état following the death of his father at the war front, in 2021 (Carayol and Backmann, 2021; Najah and Lyammouri, 2022, pp. 13–14; UA, Press release 996th Meeting of the Peace and Security Council, Report on fact-finding mission to Chad, May 14, 2021).

What can explain the inadequate response and the inability of both the African Union and its regional organizations to curb coups d’état on the continent? Could the African regional organizations’ failure to act or somehow their indifference when there are constitutional coups be one of the factors amplifying popular support for military coups in some African countries affected by the phenomenon?

This article is based mainly on documentary research using historical, strategic, rational choice and institutional analysis (Gazibo and Jenson, 2015) to understand the various positions of the African Union and its regional integration bodies regarding all forms of coups d’état in the continent. The approach consisted of examining several official communiqués from these African organizations in order to unravel the contradictions in their positions on the different types of coups and the discriminative treatment applied from economic, political and diplomatic sanctions imposed concerning military coups, and the complicit silence and absence of sanctions when it comes to constitutional and electoral ones. In order to grasp the extent of this phenomenon on the African continent, the study relied on secondary data highlighting the various statistics on the permanence of coups d’état in Africa in all their diversity: military, constitutional and electoral coups. By examining the literature on coups d’état in Africa and using current events, we have been able to understand the paradigm shift in the perception of contemporary coups d’état in Africa and the extent to which West African public opinion supports the idea of a reformist putschist who breaks with the post-colonial African state and neo-colonial practices.

It is worth acknowledging from the outset that, prior to 1990, military intervention was the principal means of regime change in Africa (Boisvert, 2022, pp. 3–4). There is no doubt that this phenomenon, has gained ground and legitimacy due to failure by the imported State and its democratic institutions to meet the challenges of governance and development in Africa There is also no doubt that coup plotters who came to power found nothing better than setting up one-party military regimes without minding democratic principles. Each time, the influence of the international events and international actors have always been felt, and have played and continues to play a decisive role in impeding democratic regimes and military regimes (putschists) to boost the development of Africa and improve the living conditions of its people.

The first military coups d’état in Africa were based on the relevant argument that the institutions of African states and their managers were unable to meet post-independence development challenges. The marks of the imported State and the weaknesses of its democratic institutions were roundly accused by the putschists, who in their rhetoric largely highlighted institutional crises, bad governance and mostly the powerlessness of the state and its leaders to boost development in the early post-independence period. Consequently, several putschists claimed that they are seizing power to correct the situation and save the people. However, such claims were not enough to explain the motives and interests targeted by the putschists of the 1960s and beyond. To confirm this, we need only to look at the way they failed to turn the African states’ situation around (Ntwali, and N’zouluni, P., 2021). In fact, they took advantage of the inexperience of independence leaders in governing newly-independent states, the former colonial power’s strong desire to maintain control over its former colonies, as well as the significant influence of the Cold War and its consequences in terms of bloc positioning (Ntwali, 2023b, pp. 188–190).

It is surprising in this context that some African putschists played the game of the former colonial power in order to neutralize some pro-independence leaders with a burning desire for self-liberation or full autonomy from the former colonizer (Ntwali, 2023a). Although some putschists found support from international players formerly absent in the continent who were out for areas of influence and struggling to block the ideological and strategic progress of the other bloc, military regimes which came to power by putsch have to a large extent served their own interests and those of their masters more than the interests of their peoples and the African continent. It should be underscored that democratic principles were not priorities in the ideological proliferation strategy of the two blocs (Kuhne, 1991, pp. 287–306; Eboko, 2006, pp. 197–204; Ka, 2007, p. 34; Gazibo, 2010, pp. 138–161). The victory of one bloc over the other, with the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, is what prompted the decisive factor in the strategic redefinition of the major orientations of the winning bloc, the Western bloc, which subsequently put forward its values, including respect for democracy and human rights in return for all forms of cooperation (Gruénais and Schmitz, 1995, pp. 7–17; Bolle, 2021, pp. 1–23). Even in this context, the application of these values and criteria of democratic conditionality was affected by double standards when it came to certain states, depending on the interests pursued and the type of influence that the actors of the Western bloc wanted to exert on the African state concerned (Kuhne, 1991, p. 290; Dia, 2010, pp. 18–24). As a result, democratic culture and development in African states have failed, with constant stagnation giving way to insecurity, political and economic instability. In this context, while a few putschists initiated development in their states and a certain institutional, security and political stability to the point of returning to constitutional order and being elected, many faced repeated coups d’état (Ntwali, 2023b, pp. 188–190; Adiémé, 2023, pp. 149–163; Bamaze, 2024, pp. 1020–1021). Coups have been the most famous ways of getting to power in Africa, and this same means has long been used by la Françafrique supporters (Borrel et al., 2021, p. 25; Pigeaud and Sylla, 2018, pp. 53–54). The table below shows the number of coups d’état in Africa, which are one of the defining features of African political evolution (Table 1).

The first thing these figures reveal is that post-colonial Africa has a long tradition of coups d’état. The figures above show that almost all African countries have experienced either one or more aborted or successful coups d’état. As Pierre Jacquemot points out, “between 1960 and 1990, the overall number of attempted coups d’état in Africa has been more or less the same, with an average of about four per year. However, between 1990 and 2020, this figure fell to half” (Jacquemot, 2023, p. 5). This drop was due to the positive influence of the second democratic wave with the advent of multi-party systems in 1990 following a multitude of national conferences. As a result, “the myth of the army as a neutral arbiter and guarantor of national security and unity gradually eroded” (Jacquemot, 2023, p. 5).

In the history of political regimes in Africa, one-party and military states have experienced several military coups d’état. The reason is simple: the absence of political alternation at the top of the State and the impossibility for civilians — particularly the opposition — to participate in the democratic game of alternation of power due to the full control of the system by the single party (Ntwali, 2021, pp. 32–33). This situation fuelled other soldiers to try their luck. Another reason is the increased contribution of the Cold War and La Françafrique in perpetuating the rule of military regimes and dictators in Africa (Ntwali, 2023a, pp. 1–9). However, the failure of national conferences between 1990 and 2005 also led to further coups d’état (Buyoya in Burundi) or armed conflicts (Laurent-Désiré Kabila’s Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire [AFDL] and Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front [RPF], for instance) (Ntwali, 2021, pp. 32–33).

The other specificity of Africa’s political history is that almost all regimes (mixed, military, democratic and even monarchical), have faced one or more aborted or successful coups. Consequently, the cause is not to be found in the type political regime (mixed, democratic or military) but in their inability to provide solutions to the problems facing their states, or in the nature of the political or military actors who once in power want to remain there for one reason or another. Each putschist with the aim of attracting greater public support for his project, provides justification, generally depending on the political context and the problems facing the country (Ntwali, and N’zouluni, P., 2021, pp. 115–116; Wilén and Guichaoua, 2023). In most cases, putschists believe they are the ultimate solution to the problem, but once in power they fail to prove it to the extent that they are toppled by other putschists who give almost the same reasons that led to the previous putsch as it happened in Burkina Faso. Another standpoint is that, both civilian and military actors have been involved in these coups d’état. But what is specifically remarkable regarding African military regimes is that the coups against them have been instigated by fellow military colleagues.

One of the damaging problems of liberal democracy in Africa, which created a fertile ground for military putsches before the 1990s, was the failure to build a true democratic culture. There is no intention here to brush aside an existing democratic culture in Africa, as many have been doing (Bayart, 2009, pp. 27–44). But it is worth mentioning that this democratic culture is inspired by the imported (westernized) State, its institutions, or at least the liberal democracy and its components that African states inherited during their decolonization. Democratic culture which is liberal is defined as:

The desire and ability of individuals in a population to participate actively, individually and together, to the government of public affairs affecting them. The existence of a democratic culture within a population is characterized by the active contribution, effective and in duration, of members of civil society to development of: the common good, the terms of “living together” and the construction of collective decisions (FDC, 2021).

In the same vein, André Brouillette, echoing Alexis de Tocqueville, states that:

Democracy, more than a simple mode of government, instilled its spirit in all spheres of society and left its mark on all social relations (Tocqueville, 2010). In this sense, we can talk of a ‘democratic culture’ whose origins are historically from the British parliamentarianism and the French Revolution. The absence of such a culture is a devastating obstacle to the setting up of a democratic electoral process” (Brouillette, 2004).

It must also be said that a sudden institutionalization at the time of independence, after several years of successful colonial rule, was doomed to failure, not only because actors were not prepared to carry out the tasks assigned to the newly independent state, but also because they had not embraced the values of liberal or socialist democracy that they inherited or adopted afterwards, in relation to their alignment with the former USSR bloc. (Ntwali, 2023a). As several observers have noted, some French and even Western politicians are condescending when referring to the causes of the failure of democracy in Africa, often forgetting their own responsibility (Bayart, 2009). Former French president Jacques Chirac, for example, felt so free to assert that “Africa is not ready for democracy!” (Sakpane-Gbati, 2011). Barack Obama reminded us some years back that “Africa does not need strongmen, it needs strong institutions” (Le Monde, 2009).

Although the words of the two aforementioned politicians may reflect a certain reality if we take a close look at democracy and its institutions in the West, they fail to mention the negative impact of their foreign policies and struggles for influence in Africa on the development of the democratic culture specific to liberal democracy in Africa. Both La Françafrique and the Cold War were at the forefront of the failure to develop a Western-style, socialist democratic culture in Africa. Many putschists and dictators have largely drawn their protection and support from the above two situations, as well as from the failure of African political actors to embrace the values and principles of liberal democracy, or indeed the socialist-style democracy they subsequently adopted. Although democratic culture was standardized according liberal democracy after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the traditional societies of pre-colonial Africa had their own values which could be described as democratic in the context of pre-colonial Africa, and which would not be at all different from certain values of liberal democracy. For instance, Eboko (2006: 198) puts it that:

The idea of popular legitimacy is not foreign to certain ancient political systems, and certain African practices are part of a democratic approach. Electoral colleges of elders (kingmakers), for example, could nominate a chief or king, as was the case among the Akan in Ghana. Participation could exist in highly authoritarian monarchical systems and be highly standardized in acephalous societies without a chief or state (Nuer, Lobi, for example). Political competition between factions existed among the Luo of Kenya, making it possible to organize alternation of power. And in many societies, deposing leaders followed various procedures, including killing the king (regicide) which was one of the most radical approach.

This first aspect of the historical-political context of coups d’état in Africa highlights the African continent’s inability to make a real choice about its model of political governance. As demonstrated above, the colonial regime waved aside pre-colonial Africa’s mode of governance and passed on its model of liberal democracy to an unprepared post-colonial Africa. In addition to this historical past, which still leaves its mark on the functioning of the post-colonial African state, the latter, or at least its actors, have not embraced the values of liberal democracy, let alone returned to the pre-colonial African mode of governance or, more difficult still, imagined a mode of political governance adapted to the African context and its socio-anthropological realities. It is worth reminding the unprecedented role of foreign powers in the failure of political stability in Africa, but the role of the African political actor remains decisive if the objective is really to develop African states and improve the living conditions of its population. The ping-pong game between democracy and military putschist regimes continues, without African political actors being able to learn the slightest lesson from it to build a genuine model of governance capable of developing and stabilizing the post-colonial African state.

It can be stated with certainty that the post-colonial African state has been a testing ground for democratic regimes and military and regimes born from coups or armed insurrection. It is equally true that, despite multiple experiences (an embryonic democratic process from independence in 1958 to 1965, some 30+ years of military regimes from 1965 to 1990, and some 33 years of democratic transition, 1990–2024), African states are still struggling to reinvent themselves and to create a governing system with stable and effective institutions capable of boosting their development. Neither the golden mean nor the third way has yet been found. It must be utterly said without fear of contradiction that the failure of the embryonic democratic process in the post-independence era, and the newly independent African state’s failure to establish responsible governance capable of ensuring stability and fostering development, caused the first military coups which crystallized into military and/or one-party regimes from 1965 to 1990 (Ayissi and Maia, 2012, p. 174).

These military regimes which initially claimed to correct the errors of post-independence democratic regimes, very quickly sank into authoritarianism, cronyism, financial mismanagement, embezzlement, corruption, etc. The end of the Cold War saw the waning of military regimes and their failure to develop African states and improve the living conditions of the masses. The fall of the Berlin Wall (1989), the La Baule Speech (1990) and the national conferences that followed were remarkable signs of a return to liberal democracy, and the African people had regained hope of being entrusted with power through the electoral mechanism and, by the same token, freeing themselves from rogue dictators (Laloupo, 2022, p. 62–69; Koundé, 2021).

Similarly, it should be noted that after the democratic wave of the 1990s in Africa, democratic elections have been plagued by issues of transparency of the ballots, leading to electoral putsches followed by post-electoral crises (de Gaudusson, 2003, p.1). In this way, the people are stripped of their sovereignty with leaders whose election and victory are widely contested by the opposition and civil society imposed on them. A crisis of democratic legitimacy then arises between the leaders and the institutions they run and the people, whose expressed choice has not been respected through the fraudulent maneuvres of the ruling parties and their almost absolute control of election institutions as well as the ones responsible for validating the final results (Souaré, 2017, p. 196; Ntwali, 2019, pp. 328–329). When there are Electoral disputes in Africa, at least in some states and for some electoral experiences of national presidential and legislative elections, constitutional jurisdictions instead of playing the role of referee, side with the ruling parties and do not give a damn about post-electoral crises, armed conflicts or even military putsches that may occur afterwards. This was the case in ‘Côte d’Ivoire in 1999 and 2011, Madagascar in 2001–2002, Gabon in 2016, DR Congo in 2011 and 2018 etc. (Ntwali, 2019, p.328–329).

As Pierre Jacquemot points out, in Africa, the current coups d’état are signs of the premature waning of imported democracy (Jacquemot, 2023). There are several clues to support this assertion. Firstly, Akindès and Zina (2016: 84) state that:

Democracy negotiated from the top, from the institutional point of view alone, is nothing but a mirage. This explains why some observers think that elections in the African context are a mere acting behind which the permanent features of an unchanging political culture are reproduced.

It the same light, Dodzi Kokoroko (2009: 118) explains that:

The constitutional judge has often acted as an accomplice in an emasculated political game designed for a power clearly longing for the one-party era. According to the so-called argument of democratization through repeated elections, “only free and fair ballots can define a democracy”. However, democracy is always the culmination of a long process, backed by an institutional system that is strong enough to deliver an independent judiciary, guarantee fundamental freedoms, provide public services, track down corruption and keep the military in their barracks or on the frontline in the fight against armed groups. Elections do not ipso facto create these conditions. They are often a fool's bargain, that create conditions for dynastic rule (Gabon, Djibouti, Togo) and several terms in power (Algeria, Burundi, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Egypt, Guinea, Rwanda, Uganda etc. (Jacquemot, 2023, p. 9).

In Africa and within African states, these elements reveal the relevance of formal democracy to substantive democracy (Ntwali, 2021, pp. 69–70; Ferrin et al., 2014, p.5). It should be said that the multiparty system that emerged in the 1990s was only interested in promoting formal electoral democracy. A minimalist democracy which, more than thirty years later, has not evolved toward the establishment of a substantial or maximalist democracy, able to put in place the development of economic and social rights that can contribute to improving people’s living conditions. Even regarding this formal democracy, the African experience shows that three decades later, the consolidation phase has not been reached (Miscoiu et al., 2015). As a result, constitutional manipulation to stay in power, cronyism to establish a stabilocracy and the irremovability of political actors in power, electoral fraud regularly affects electoral processes and often leads to armed conflicts or post-electoral crises (Pommerolle and Jose-Durand, 2017, pp. 169–181). Constitutional courts unhesitatingly validate election results mired in electoral fraud, and independent electoral commissions play the ruling party’s game in its retention of power. In this context, African peoples vote but hardly find their choices in the final results proclaimed (Gatsi, 2019, p. 937; Ntwali, 2019, pp. 327–358; Adouki, 2013, pp. 611–638).

The persistence of these aforementioned challenges, the rise in power of terrorist groups, geopolitical upheavals on the international scene and the inability of African political actors in power and their traditional partners to meet these security and socio-economic challenges are giving way to the return of the putschist savior and a new cycle of military regimes based more on populist rhetoric based on a Pan-Africanism advocated and supported by a youth hard hit by unemployment and disappointed by the inability of their states to create conducive conditions for peace and development (Antil, 2023). Whatever may be said, current military putsches are justified largely by the fact that formal democracy has almost completely failed in Africa. But a surprising thing is that putschists and their military regimes are not new to Africa, just as their experience over 30 years of rule has not been glorious from the point of view of political and institutional stability, the development of the African state and the improvement of living conditions of the African people.

In light of the foregoing, swinging between formal democracy and military putsches is a sad reminder that Africa is in turmoil, unable to choose a system of governance which suits its socio-anthropological realities, or simply unable to embrace the values of liberal democracy. If the political regimes in power in Africa have to a large extent undermined the principles and values of formal democracy, what assessment can be made of the contribution of African regional and sub-regional organizations to the democratization process on the African continent? Put differently, how are these organizations responding to the resurgence of multifaceted coups d’état in their member states?

The zeal for democratic transition in Africa has not only consumed African states, but also regional integration organizations, starting with the continental organization known as the African Union (Mpiana, 2012, p. 103). Legal responses have been devised within the African Union and its regional organizations to give a chance to democratic transition and consolidation within member states (Mpiana, 2012). A formal ban on unconstitutional changes of government has been put in place by the African Union and its components (African Union, 2007). At the political level, sanctions have also been designed and applied several times to cases of military putsches on the continent. These sanctions range from the non-recognition of governments and authorities resulting from unconstitutional changes of government, to political and economic sanctions, through obligation, to a large extent, for actors who come to power by coup d’état to return to constitutional order by handing over power to civilians in the event of a military putsch. The practice of the African Union and African regional organizations remains equivocal when it comes to constitutional and electoral coups d’état within member states. A discriminated approach to responding to coups d’état can be observed, with two trends: firm and swift condemnation of military putsches, and certain indifference with constitutional and electoral coups. Despite the firm condemnation and collusion, is the African Union and its regional organizations equipped to deal with coup perpetrators, whether military or civilian? The impotence of these organizations is not without significance for the current process of legitimating military putsches.

The African Union and its regional organizations have on several occasions been confronted with various forms of coups d’état: military putsches and constitutional coups d’état (Youmbi and Cissé, 2023, pp. 25–52). What is interesting in this context is that, as earlier mentioned, a legal mechanism already exists in Africa to formally prohibit unconstitutional changes of government. This prohibition applies to both military and constitutional coups. More concretely, in 2000, following the adoption of the Constitutive Act of the African Union, the latter made “condemning unconstitutional changes of government its major weapon” (Mpiana, 2012, pp. 101–102; Ntwali, 2021, pp. 83–84). To achieve this objective and stop with the gruesome history of coups d’état, the African Union adopted the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance in 2007. The Charter is “original in its objectives, as it aims to establish a continental political organization and a model of political system previously accepted by the States on a regional scale. This Charter proposes a way of establishing and preserving democracy in Africa” (Tchikaya, 2008, p. 522). It also marks a certain “collective will on the part of States to work relentlessly to deepen and consolidate democracy” (Tchikaya, 2008). At institutional level, the African Union’s Peace and Security Council is the body recognized as having the right to react whenever an unconstitutional change of government occurs on the African continent (Mpiana, 2012, p. 101).

This positive development by the African Union, marked by the establishment of a legal and institutional framework against unconstitutional changes of government, is a response to one of the major causes of conflict in Africa. The Charter in question does clearly states in its preamble that unconstitutional changes of governments are one of the essential causes of violent conflict in Africa. Although these unconstitutional changes of government in all their diversity are not the only causes of conflict in Africa, they significantly contribute to it (Mpiana, 2012, pp. 107–118). But the persistence of conflict and terrorism, and the inability of some of the African states affected to find lasting solutions, are today among the causes of the very decisive return of military coups in Africa, especially in the Sahel. This observation shows that, unconstitutional change of government is the cause of the persistence or advent of some conflicts in Africa, just as some persisting irresolvable conflicts lead to some extent to the return and resurgence of military putsches in Africa and particularly in the Sahel (Mpiana, 2012). This is why the African Union and its regional organizations should be able to make their collective security mechanisms operational and effective by providing the continent with military capabilities able to impose peace on all its states (Alimata, 2019; Esmenjaud, 2012).

These legal-institutional mechanisms of the African Union and its regional organizations also provide for sanctions against any government resulting from an unconstitutional change of government. Although the Constitutive Act of the African Union does not expressly limit the sanctions to be imposed against unconstitutional changes of government, the reading of articles 4(p), 23(2) and 30 of the said Constitutive Act reveals a diversity of measures such as: a ban on participation in the organization’s activities, economic and political sanctions which may take the form of embargoes, and any other sanction deemed necessary by the conference. Under article 23 of the Constitutive Act, the African Union and its member states shall be responsible for implementing the sanctions announced by the authorized body. Article 4(h) even gives the African Union the possibility to use military force if the unconstitutional change of government results in serious crimes: war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide (African Union, 2000). In so doing, the Constitutive Act of the African Union broke with its long-standing doctrine of non-interference in its member states, which was once enshrined in the Charter of the Organization of African Unity (Nassima, 2017, pp. 47–65). It is therefore the principle of non-indifference enshrined in the aforementioned article 4 (h), and which in a way empowers African Union to intervene directly without waiting to obtain authorization from the UN Security Council for any use of armed coercive measures in favor of regional organizations (Kolb, 2005, pp. 1415–1437). More specifically, some African regional economic bodies have also expressed their opposition to unconstitutional changes of government.

ECOWAS, for instance, took part in this objective by revising its founding treaty in 1993. With this revision, ECOWAS, like the African Union, brushed aside its doctrine of non-interference in the internal affairs of member states, granting itself the possibility of to intervene through its own mechanisms, those of the African Union, and the universal ones enshrined in the UN Charter. In addition to the aforementioned constitutive treaty, two legal instruments are of particular interest with regard to unconstitutional changes of government within ECOWAS. They include: Lomé Protocol (December 1999) on the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peacekeeping and Security, and the Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance (December 21, 2001). These legal instruments formally prohibit unconstitutional changes of government, and provide for sanctions against any such change. In this light:

In the event that democracy is abruptly brought to an end by any means or where there is massive violation of Human Rights in a Member State, ECOWAS may impose the following sanctions on the State concerned: Refusal to support the candidates presented by the Member State concerned for elective posts in international organizations; Refusal to organize ECOWAS meetings in the Member State concerned; Suspension of the Member State concerned from all ECOWAS decisionmaking bodies. (CEDEAO, 2001; Fall and Sall, 2009, pp. 1-7).

In practical terms, these legal mechanisms enable ECOWAS to adopt political, economic or legal sanctions against the guilty State, depending on its assessment of the situation. It is worth noting that the proliferation of these democracy-protecting and anti-constitutional change-of-government norms and mechanisms is so real today within several African regional integration organizations, that it would be difficult to tackle all them of in this paper. The practical implementation of these mechanisms and norms concerning some of the military putsches that have taken place, and the various reactions and actions of the African Union and some of its regional organizations enables us to make an assessment.

Although the results of the actions and reactions of the African Union and its regional integration organizations may have a lesser contribution in preventing military putsches, their permanence and regularity are nonetheless to be commended. In short, these actions and reactions have somehow help restore constitutional order, after a number of issues between the putschists, the African Union and the regional integration organizations concerned (see, for instance, the AU’s position in 2005 regarding the Mauritanian putschists in the Commission’s report on the situation in Mauritania, page 2). However, they have been unable to prevent future military coups and to consolidate the democratic transitions that had begun after the military putsches. The reality is that these different organizations have attacked the military putsches more than the causes. These causes are tackled below.

The consistency of the actions and reactions of the African Union and its regional organizations is remarkable, and can be seen in every decision taken to condemn military putsches. If we look back 14 years to the putsch in Niger on February 18, 2010 against President Mamadou Tandja, and almost 12 years to the putsch in Mali on March 22, 2012, we realize that the position of the Peace and Security Council has remained the same in its rigor and strength in the face of the two aforementioned putsches. Thus, during its 216th meeting on February 19, 2010, the Peace and Security Council announced the following measures against the putsch in Niger:

Demand for a rapid return to constitutional order based on democratic institutions […], readiness of the African Union […] to facilitate this process in close collaboration with ECOWAS […], suspension of Niger's participation in all African Union activities until the effective restoration of constitutional order to what existed prior to the referendum of 04 August 2009 (Chauzal and Baudais, 2011, pp. 295-304).

It should be noted that, this putsch took place following a constitutional coup orchestrated by the incumbent President of Niger, Mr. Mamadou Tandja, who had initiated a referendum to extend his term beyond the constitutional deadline, despite the contrary opinion of Niger’s Constitutional Court on May 25, 2009 (Mpiana, 2012, p.132). Neither the African Union’s Peace and Security Council nor ECOWAS reacted against this constitutional manipulation. In Mali, Toumani Touré, “democratically elected president in 2002 and re-elected in 2007, was overthrown by a military putsch on March 22, 2012, a few weeks before the end of his second term” (Mpiana, 2012, p. 132). In response to this military coup, the Peace and Security Council of the African Union through a communiqué during its 315th meeting decided to:

Firmly condemn the military putsch, request constitutional order to be restored, suspend Mali from all the activities of the AU until effective restoration of constitutional order with the organization of presidential elections. During this process, on April 16, 2012 ECOWAS took initiatives through the signing of a Framework Agreement for the implementation of the solemn undertaking of April 1, 2012 between the ECOWAS mediator and the (National Committee for the Recovery of Democracy and the Restoration of the Rule of Law [CNRDRE]) set up by the ruling junta (Mpiana, 2012).

The same sanctions were taken by the AU and The Southern African Development Community (SADC) against the putschists in Madagascar in March 17, 2009, when Marc Ravalomana “under pressure from the civilian opposition and the army, resigned and handed over power to a military board. Despite the sanctions that were imposed and the various agreements implemented for the return to constitutional order under the mentoring of SADC, the putschists stubbornly remained in power” (Mpiana, 2012). This situation shifted the various deadlines set out in the Maputo Agreements of August 8 and 9, 2009 and the Addis Ababa Additional Act of November 6, 2009. Following this behavior, the African Union, through the Peace and Security Council, increased its sanctions to include travel ban on all the persons involved in the coup, asset freezes and diplomatic isolation of the authorities resulting from the unconstitutional change of government in Madagascar (Mpiana, 2012).

While the Au’s position through its Peace and Security Council has been mostly the same regarding sanctions against military putsches in recent years in the Sahel and West Africa in general (Mali, Guinea-Conakry, Burkina Faso, Niger), ECOWAS sanctions have first been limited to the aforementioned sanctions, before subsequently increasing to include economic and diplomatic sanctions, border closures in the case of Mali up to the freezing of the Malian state’s financial assets, while threats of a possible military intervention by the organization were mostly mentioned in the case of Niger, in addition to economic sanctions (ECOWAS and WAEMU), political sanctions and border closures (CEDEAO, Final communiqué on the situation in Niger, 10 December 2023, CEDEAO, Final communiqué on the situation in Mali, 9 January 2022, CEDEAO, Final communiqué on the situation in: Mali, Burkina Faso, Guinea, 3 February 2022) (CEDEAO, 2023, CEDEAO, 2022a,b). The case of Niger has been clearly the talk of the press because ECOWAS threatened to use military force on several occasions and through several communiqués, before some of its member states hesitated to support such an action in view of the possible serious consequences of instability it would cause in the sub-region (Sulaiman, 2023).

ECOWAS’s threat to use force in the Niger case was due to the putschists’ refusal to release President Mohamed Bazoum and hand over power to him as democratically elected president (Sulaiman, 2023). Failure to respect the deadline for the organization of elections that could lead to the restoration of constitutional order has contributed to the increase in sanctions and radicalization between the regional organization, ECOWAS and some ruling juntas. In Mali, for example, the first deadline for the organization of elections with the aim of restoring constitutional order was set at 18 months by mutual agreement between the ECOWAS mediation team and the authorities of the first transition. Against all expectations, the second coup d’état took place on May 24, 2021, and was approved by the Malian Constitutional Court (Zevounou, 2022, pp. 19–38). And through national meetings, the transition period within which elections were to be held was extended to 5 years. This fuelled the anger of the regional organization toward the ruling junta and triggered a strong radicalism and crisis of confidence between the players involved (Zevounou, 2022). From these few cases of military putsch, we note the severity and formalism of regional organizations in condemning military putsch and demanding a return to constitutional order. Nowhere, in the aforementioned cases, does ECOWAS make the slightest effort to understand the causes of these military putsches and provide more lasting solutions, despite the categorical imperative of a return to constitutional order. But in a functionalist logic, how does constitutional order help in a context of political and security instability if not to provide sporadic and ephemeral solutions that can quickly lead to further military coups? This is the conclusion that can be drawn from the action of the AU and its regional organizations regarding military putsches in Africa. The African Union and its regional integration organizations have responded in opposing ways regarding some cases in the infernal history of constitutional coups within member states.

The practice of constitutional coups d’état in Africa which boil down to manipulating the Constitution to stay in power, reveals a certain implicit approval on the part of the African Union and its regional integration organizations. These manipulations of the Constitution are also real evidence of the failure the emergence of a democratic culture in Africa, and state actors’ refusal to abide by the established rules they committed to by ratifying them. It should also be noted that the law is not only what has been enacted, but also what actors do with it (Miaille, 1992, pp. 73–87). Consequently, as Diop (2023: 267) points out, the very nature of the rule of law is to be a rule sanctioned by authority and sanction is a measure accompanying any rule of law and based on the violation of an obligation arising from this rule of law. It is therefore unproductive to provide legal mechanisms for promoting democracy in Africa without applying sanctions in the event of violation. Community and national norms for promoting democracy in Africa fail to be effective. Inappropriate amendment of constitutions occurs with no possibility for them to stand the test of time and contribute to the construction of the democratic ideal sought in Africa. These constitutional manipulations, known as constitutional coups are varied:

Constitutional amendment to increase the number and lengh of terms, thereby creating a third term of office, constitutional amendment to increase the age limit, the adoption of a new constitution (by referendum) at the end of a mandate to reset the clock, biased interpretations of constitutional provisions by the constitutional court or the adoption of constitutional laws (by parliament) to extend the term of office beyond the constitutional deadline, the modification of the number of rounds to ensure victory in the first round during elections, etc. In addition to these various forms of constitutional manipulation (the list is not exhaustive), there is electoral fraud in all its diversity, generally orchestrated by the ruling party, with the help of the institution tasks with organizing elections. These various ways of acting crystallizing the constitutional coup d'état are accompanied by the bloody repression of any protest and post-electoral violence leading to political instability and ongoing conflict in several African states (Séne, 2014, p. 233; Kokoroko, 2009; Fall, 2010, p. 556; Ntwali, 2019; Ntwali, 2022, pp. 41-88; Souaré, 2017, pp. 81-105).

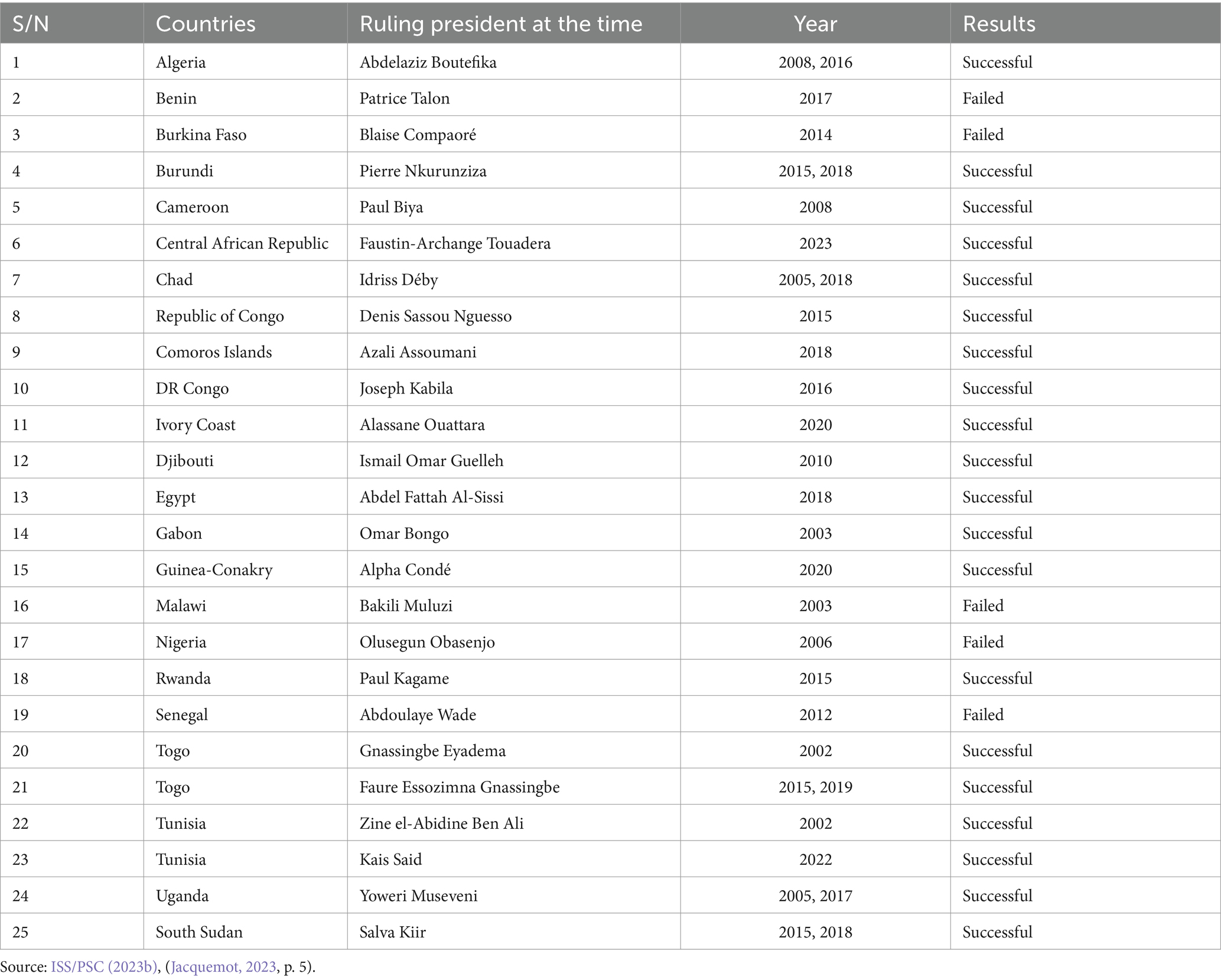

The number of attempts to change the constitutional provision limiting the number and length of mandates in Africa are incredible, and reveal the enduring practice of constitutional coups in African states after the democratic renewal of 1990. The table below provides a detailed overview.

The above figures show the dramatic success of “attempts to amend constitutions to extend political power in Africa between 2002 and 2023” (ISS/PSC, 2023b). Out of 25 attempts, 20 succeeded and only 5 aborted. These figures represent “one attempt per year over the last two decades of the African Union’s existence, with a success rate of around 78%” (ISS/PSC, 2023a). While the democratic renewal of 1990 contributed to significantly reduce military putsches in Africa (1990–2020), it is obvious that constitutional coups gained considerable ground between 2002 and 2023, and failure by African community organizations to condemn them contributes to legitimate current military putsches in part of the African public opinion (Berghezan, 2023, p. 3). However, it is important to point out that based on the figures of Table 2 above, not all the provisions relating to the length of some presidential terms that have undergone these various changes did not have the status of intangible or absolutely intangible constitutional provisions. Consequently, they provided for an appropriate procedure for amending them (as in Rwanda, for example: based on the procedure provided for in Article 193(3) of the 2003 constitution, Article 101 relating to the mandate was amended in 2015) (Ntwali, 2021, pp. 113–114).

Table 2. Attempts to amend or abolish constitutional provisions relating to the number of presidential mandates from 2002 to 2023.

Consequently, amending the Constitution does not actually constitute a constitutional coup d’état if it complied with the relevant procedure and if the circumstances surrounding the amendment were not accompanied by constraint, pressure on the institutions, on the population and on the actors involved, but also in the event of a referendum not affected by fraud or terror (Ntwali, 2021). On the other hand, their amendment has negative effects on the alternation of power, leading in most cases, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, to a monarchization of power (Ntwali, 2021). Although the presidential term-limit clause did not allow any amendment for a third mandate, some regimes in sub-Saharan Africa have designed institutional and political strategies to circumvent it. Constitutional courts’ jurisdictional mechanisms have on several occasions been used by some ruling party parliamentarians to extend mandates or outrightly validate a third one (Maruhukiro, 2021, pp. 88–90; Koko and Kalulu, 2017, p. 100; Ntwali, 2021, pp. 99–120). It is indeed the circumvention of these intangible constitutional provisions relating to the length and number of presidential mandates, their amendment to run for a third term or the adoption of a new constitution to start everything from scratch at the end of the term that constitute constitutional coups d’état. This explanation seems interesting because the table above seems to ignore this nuance specific to the legal jargon of presidential term-limiting clauses.

The reason for referring to Table 2 in this study is not to highlight the specific arguments for each side and each case that prompted actors to resort to the various manipulations of the Constitution. Instead, our interest is the position of the African Union and its regional integration organizations. To go straight to the point, the African Union and its regional integration organizations are demonstrating a kind of connivance, implicit approval or otherwise, a deliberate refusal to condemn constitutional and electoral coups orchestrated by ruling governments. Indeed, it is partly based on this attitude that a certain segment of public opinion in the ECOWAS region does not believe in the importance of this organization, its efficiency and the very validity of their states’ membership. This loss of confidence in the legitimacy of the ECOWAS by its citizens is based to a large extent on the absence of the aforementioned organization in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel (Traoré, 2023, pp. 137–149), its collusion with constitutional coups and its harsh and radical attitude against military coups. Another view is that the organization is being influenced by foreign powers determined to maintain their hegemony in the Sahel at a time when the rhetoric of the military putschist is being hailed among desperate young people who have been abandoned for years by the ruling regimes and the ineffectiveness of their partners in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel (Traoré, 2023). In fact, there is a legitimate question that should be asked: is there is such a thing as a good or bad coup d’état, in the light of the legal and institutional mechanisms of the African Union and its regional integration organizations, which prohibit unconstitutional changes of government?

It is true that in the architecture of the legal-institutional mechanisms of the African Union and its regional economic organizations, manipulation of the Constitution to stay in power is unambiguously qualified as unconstitutional change of government and would deserve the application of the same sanctions as for military putsches (Article 23§5 African Charter of Democracy, 2007). But in practice, things do not work out as planned. Hence the following fundamental question: why does the African Union and its regional integration organizations not sanction constitutional coups d’état or what prevents them from doing so? What should be said about the ineffectiveness of their sanctions against military putsches in the Sahel?

Taking into account the many recent criticisms against the African Union and its regional integration organizations, in particular the African Union itself, ECOWAS and ECCAS etc., regarding the resurgence of coups d’état in Africa, the failure of democratic transition, the intractability of security challenges on the continent and the stagnation of the regional integration process in Africa, it goes without saying that the appellation “fall guy” better suits these organizations (Agbezoukin, 2022; Les Echos, 2023; Zevounou, 2023; TV5 Monde, 2021). Clearly, these organizations are being accused due to the myth of the autonomy of regional organizations vis-à-vis their member states (2.2.1). The general tendency is to consider the failure of these organizations leaving aside the limits of their means and operational mechanisms in the African context. The absolute sovereignist posture of some member states and state actors involved in coups, weakens these organizations and make their actions useless (2.2.2). Faced with security challenges, while some ECOWAS member states have embarked on military alliances to combat terrorism outside the regional organization, others have shown greater flexibility concerning the Niger junta case (Kouwonou, 2023). Military juntas refuse to subscribe to the regional organization’s agenda for a return to constitutional order, preferring instead to leave the organization and set up an alliance between military juntas.

A flashback to the debate between realist-neorealist and liberal approaches concerning the place of international organizations in the international system reveals the challenges they face in relation to the behavior of their member states. In reality, despite the idealization of functional, legal and financial autonomy, these organizations are merely a reflection of their states in terms of operationality and efficiency (Yabi, 2010, p. 49). Thus, to speak of the ineffectiveness or even failure of the African Union and its regional organizations, in this case ECOWAS, in the face of coups d’état, no matter the type, requires an understanding of this variable, which is inherent to the very essence and functioning of international organizations. A closer look at the functioning of regional organizations in the ECOWAS region and Africa as a whole reveals the predominance of realist and neorealist components, despite the fact that they operate within an institutional architecture inspired by liberalism, whose rules exert little or no influence on member states’ respect for the democratic principles emerging at Community level. Going back to basics, realist and neorealist approaches emphasize that international organizations are manipulated by dominant states, or are unable to be more than a reflection of particular interests and power games, while, on the other hand, the more idealistic vision of the liberal institutionalist trend explains that, despite their egocentric nature, states cooperate and create international organizations to manage interdependencies (Rioux, 2013). Questioning international law and even African community law, this myth stance of African regional organizations is visible through their available legal-institutional mechanism (Bourdet, 2005, p. 5). An international organization is defined as “an association of States constituted by treaty, endowed with a constitution and common organs, and possessing a legal personality distinct from that of its member States” (Forteau et al., 2022, pp. 807–808). This definition, which is consistent with the positivist approach to international law (Tourme-Jouannet, 2022; Corten, 2009, pp. 45–46; Ouédraogo, 2010, pp. 507) clashes with the reality of the situation when we critically analyze the action of African regional integration organizations regarding coups d’état. The truth is that, at operational level, these organizations find it hard to assert their autonomy from member states and their divergent interests.

The reality is that “structural and organizational factors create both opportunities and constraints for decision-makers in regional organizations facing various challenges: insecurity, coups d’état, integration issues, development issues, etc.” (Brown, 2015, pp. 5–20). The criticism of the powerlessness of African regional integration organizations regarding coups d’état should consider the fact that, within these organizations, the supreme decision-making body remains the summit or Conference of Heads of State and Government (Byiers et al., 2020, p. 15). These state actors, i.e., the heads of State, are the ones behind the choices, orientations and decisions within these regional organizations. In light of the foregoing, we agree with Mathias Forteau, Alina Miron and Alain Pellet that “the functioning of an international organization is inevitably marked by the tension and complementarity between the principles of law of treaties, on the one hand, and the requirements of autonomy and efficiency of any human organization, on the other” (Forteau et al., 2022, pp. 807–808). Put simply — referring to the reality specific to African regional integration organizations — there is a wide gap between the principles contained in the various constitutive treaties and complementary acts promoting democracy, the behavior of member states in applying and respecting said principles, and the rather fragile stance of the regional organization concerned in applying sanctions in relation to its decision-making and institutional bodies dominated by member states (Bourdet, 2005, p. 12; Dieye, 2016, pp. 1–9).

The example of ECOWAS regarding the recent coups d’état clearly illustrates the fragility of decision-making and institutional capacity of the African regional integration organization in promoting democracy and securing its regional space. Concerning constitutional coups d’état, the decision-making body (the Conference of Heads of State and Government) show a kind of incredible indifference. This indifference is because the constitutional coup d’état in question is the work of an incumbent Head of State who wants to serve a third term or extend his mandate. He is actually a mate of those who are called upon to decide within the regional organization to sanction him. The principle of mutual solidarity then comes into play, and we find ourselves served simple courtesy communications (CEDEAO, 2024). The regional organization will then behave in the face of the constitutional coup d’état as desired by the various Heads of State who are called upon to sit down and decide on the organization’s position when there is a constitutional putsch (African Union, 2021). As a result, any hope that the organization can sanction the author of a constitutional coup logically disappears to protect the solidarity pact between its decision-makers.

On the other hand, punitive activism is observed when it is a military putsch. No recent military putsch escaped ECOWAS sanctions, which have sometimes gone beyond the custom of economic and political sanctions only, to consider the possibility of military intervention (as in the case of Niger). The organization’s activism in suppressing military coups can only be explained by peer-to-peer solidarity. These Heads are called upon to quickly and firmly act to save the power of their ousted mate, with the idea that next time it could be another mate. The military must therefore be strongly discouraged from taking power, or to a large extent, from nurturing the desire to do so. It becomes clear that the organization mobilizes against military putsches to defend incumbent Heads of State. In such an environment, the sanctions against the military putschists utterly lack legitimacy because they are taken by a circle of friends who want to protect their seats, and some of them who are active members have kept themselves in power through constitutional coups (ISS/PSC, 2023a; Adamou, 2023). In a show of solidarity, the military putschists also ally and set up institutional and operational mechanisms to defend themselves, either by threatening to react the same way if the organization intervenes against one of them or quitting the said organization and creating a another one between putschists. In such a context, where would be the place of ECOWAS or the African Union, with their self-proclaimed autonomy? Do they have the means to do without their member states at the decision-making level and, if need be, impose a certain conduct on them in the prevention of coups d’état within the regional area concerned?

The effectiveness of an international organization depends to a large extent on the behavior of its member states. Members must comply with the organization’s founding treaty and secondary law that develops within the organization. This implies that it is difficult if not impossible for the organization to function properly if all member states do not abide by the pre-established rules (Forteau et al., 2022, pp. 817–819; David, 2016). Unlike the legal personality of States, “which are original and plenary, that of international organizations is derived and limited by the scope of their roles granted by member states to achieve well-defined objectives and functions” (Forteau et al., 2022; David, 2016; Diez de Velasco, 1999). Member states and their citizens are the primary beneficiaries of the rules and principles that emerge within the regional organization. This gives these rules the characteristic of Community Law, and gives them the privilege to be directly implemented in the regional area. The essence of the rule of law is that its violation can be sanctioned by a competent authority. However, in the case of ECOWAS and other African regional integration organizations, perpetrators of constitutional coups are not sanctioned. Unsurprisingly, the institutional set up of these organizations does not enable them to be independent from their member states and to sanction them for violation of the norms and principles that promote democracy.

Indeed, some are quick to condemn institutional mimicry within African regional bodies, which have copied the institutional model of other organizations whose socio-historical and anthropological contexts are different from that of African (Byiers et al., 2020). While regional integration organizations — mostly Western — benefit from a certain functional autonomy vis-à-vis their member states as a result of the successful development of democratic culture within these states, the failure of democratic transition within African states is transposed to the regional level and prevents the regional organization from achieving its missions (Byiers et al., 2020). The organization is condemned in the court of public opinion, forgetting that it has no means to impose itself on its member states. The Conference of Heads of State which is the supreme body, is made up of supporters and some beneficiaries of a third mandate, who operate on a peer-to-peer basis. This domination of the regional organization and its actions by these heads diminishes its legitimacy and significance in the eyes of the Community’s citizen (Afrobarometer, 2024, pp. 1–5). Moreover, it would be clumsy to claim that Heads of State who are unable to respect their own constitutions — and, by the same token, their people, who are normally the source of power in a democratic regime — can respect or ensure respect for the same democratic principles, that they violate on a daily basis, in their own States at regional levels.

If the same failure in democratic governance can be transposed to the regional level, the financial and economic fragility of African states can also be seen at the level of regional bodies. Several African states have budgets with a significant percentage from outside (Adamou, 2015, pp. 5–27). The insolvency of state to African regional organizations regarding contributions exposes them to external dependence (Ambrosetti and Esmenjaud, 2014, p. 135). They receive aid and funds to operate from other international organizations or third-party states. In this case, it is only logical that those who fund these African organizations should be able to exert an influence on their actions, even imposing on them what to do when there is a problem at the regional level (Adamou, 2015, pp. 5–27). In terms of security, African states, and especially those in the Sahel, have distinguished themselves by forging military alliances with third-party states in the fight against terrorism, putting the regional organization ECOWAS in the background (Traoré, 2023). Public opinion supports military putsches, for example, it criticizes ECOWAS for its inertia in the face of terrorism, but forgets that it has no own funds apart from those contributed by its member states (Daniel, 2024). If these member states prefer alliances such as the G5 Sahel because they know they will be relieved of the primary obligation to finance the force, what can ECOWAS, which can only act through them, do?

Another standpoint is that, states do not relinquish their sovereignty by becoming members of an organization, even a supranational one (Forteau et al., 2022, p. 822). These states remain free to exit voluntarily from the organization as in the case of ECOWAS today, from which three member states (Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger) under its sanctions for military putsches exited and subsequently created another organization called the “Alliance of Sahel States” (AES) (Agbezoukin, 2023). The said states are accusing ECOWAS and its other member states of “acting under the influence of foreign powers, with France in the forefront,” while some ECOWAS states and their partners, including France, are also accusing them of acting under Russian influence (Siegle, 2022). This state of affairs once again demonstrates how weak the regional organization and its sanctions are before its member states. They can exit at any time if political actors in power do not feel comfortable with the Community’s standards. The context has been such that currently only the putschists under sanctions decide to quit the organization, but it is not impossible that some potential constitutional putschists will in turn leave the organization when it will sanction them in the future or through a certain leadership within it. Seck (2018: 15) points out that, while State sovereignty in Europe has been greatly diminished by integration into the European Union, in Africa, sovereignty seems to have retained its strength in the even with regional integration. For the aforementioned author, historical and contextual realities would explain this state of affairs. The sovereignist shield is one of the obstacles preventing the African integration process from succeeding in good governance, democratic transition and development in African. Ideas have been expressed several times within African regional organizations, without any real willingness to act at member state level. Africa remains economically and democratically disintegrated, with a very weak security fabric, despite the presence of a multitude of regional integration organizations.

African states, in all their diversity, have been hit by coups d’état on several occasions. While the failure of the first democratic transition after independence led to military putsches as a means of taking over power from military and totalitarian regimes, the second democratic wave was soon hit by constitutional and electoral coups, which played a major role in its failure and are now highlighted as one of the causes of the current resurgence of military putsches. Driven by the need to democratize Africa, and under the impetus of the values of liberal democracy put forward by the victory of the Western bloc over the former USSR, the African Union and its regional organizations have integrated into their legal and institutional frameworks, norms and principles against all types of unconstitutional change of government, including military and constitutional putsches.

This study set out to show that these democratic norms and principles have still not had a significant influence on African states and their leaders. That said, the failure of democratic transitions at national level has been transposed to the regional decision-making level, making it difficult for African regional integration organizations to enjoy functional autonomy. These organization are therefore active in condemning military putsches but connive with constitutional and electoral coups, with decision-making bodies dominated by peer-to-peer solidarity of rulers, including their perpetrators and beneficiaries. This lack of functional autonomy within African regional integration organizations is accompanied by financial insecurity as members do not pay their contributions or do it irregularly. It is worth noting that the financial insecurity of these States, some of whose budgets are largely dependent on external aid, also has repercussions at regional level. On top of that, the organizations in question are dependent on external aid and funding, which exposes them to geopolitical influence that negatively affects their agendas and attitude when faced with various regional problems. Affected by these two variables, these organizations lack legitimacy in the eyes of its citizens, to whom their existence provides no solution concerning insecurity and the development problems they face.

The military putschist thus appears as the savior in a context of regional insecurity and instability (Sahel) in which several regional and international initiatives have failed. However, it is also true that most the current putsch makers belong to the Republican Guard or Special Forces that have played and continue to play a major role in the success of constitutional and electoral coups in Africa. Through bloody repression of anti-third-term demonstrators and social movements, these Special Forces have repeatedly thwarted the possibility of a civilian democratic transition and each time, they took advantage of the situation to stage a military coup.

Therefore, it is not easy, in a context of democratic, financial, security and institutional fragility, to come up with magic solutions that would make the action of the African Union and its regional integration organizations effective in combating coups d’état in all their diversity: military or constitutional. Nevertheless, a firm response to any form of coup d’état would at least enable these organizations to maintain their legitimacy vis-à-vis the citizens of their member states. This also means that the operational effectiveness of these organizations in implementing their policies and objectives in terms of the democratization of their regional areas depends to a large extent on the behavior of their member states and the leaders of these states to submit to the norms relating to democratic alternation and good governance at national level first, so that this can be reflected at regional level. Conferences of Heads of State, which are the decision-making and guiding bodies of African regional integration organizations, will only effectively combat coups d’état if those who chair them do not remain or have not remained in power through a coup d’état.

As it stands, the three questions below are still unanswered regarding the Sahel:

• How will the Alliance of Sahel States behave when one of its members faces a possible military putsch?

• Will the position of this organization in favor of any of the protagonists result in a possible voluntary exit of the member concerned?

• What are the chances that members of the Alliance of Sahel States will return to constitutional order after their voluntary exit from ECOWAS?

“Article translated and published” with the support of EUR FRAPP (ANR-18-EURE-0015 FRAPP).

VI: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adamou, M. (2015). Intégration régionale, dépendance et espace Sahélo-Saharien (Regional integration, dependence and the Sahelo-Saharan space). Pensée 381, 5–27. doi: 10.3917/lp.381.0005

Adamou, M. (2023). Les sanctions juridictionnelles aux violations de l’ordre constitutionnel dans l’espace CEDEAO (Jurisdictional sanctions for violations of the constitutional order in the ECOWAS region). Fren. J. Constit. Law 134, 265–301.

Adiémé, F. (2023). “Jerry Rawlings: a patriot's legacy (1979-2001)” in Maquisards, rebelles, insurgés politiques … Le devenir des chefs de guerre africains (Maquisards, rebels, political insurgents. The future of African warlords). eds. S. Sergiu Miscoiu, et al. (Cluj-Napoca: Casa Cartii de Stiinta).

Adouki, D.-E. (2013). Contribution à l’étude de l’autorité des décisions du juge constitutionnel en Afrique (Contribution to the study of the authority of the constitutional judge’s decisions in Africa). Rev. Fr. Dr. Const. 95, 611–638. doi: 10.3917/rfdc.095.0611

African Union (2007). Charte africaine de la démocratie, des élections et de la bonne gouvernance. Durban: African Union.

African Union (2021). Communiqué de la 96ème reunion du Conseil de Paix et Sécurité de l’UA sur l’examen du rapport de la mission d’enquête en République du Tchad. Durban: African Union.

Afrobarometer. (2024). Le retrait de la CEDEAO, le dernier chapitre de la relation autrefois considérée comme positive (Exit from ECOWAS, the final chapter in what was once a positive relationship. Available at: (https://www.afrobarometer.org/articles/le-retrait-de-la-cedeao-le-dernier-chapitre-de-la-relation-autrefois-consideree-comme-positive/).

Agbezoukin, D.. (2022). La CEDEAO et les coups d’état en Afrique de l’Ouest: quel cadre juridique pour quelles actions préventives (ECOWAS and coups d'état in West Africa: what legal framework for preventive action)? Institute of Applied Geopolitical Studies. Available at: (https://www.institut-ega.org/l/la-cedeao-et-les-coups-d-etat-en-afrique-de-l-ouest-quel-cadre-juridique-pour-quelles-actions-preventives/).

Agbezoukin, D.. (2023). La CEDEAO et les putschistes nigériens: la confrontation de la désintégration (ECOWAS and the Niger putsch perpetrators: the confrontation of disintegration)? Institute of Applied Geopolitical Studies. Available at: (https://www.institut-ega.org/l/la-cedeao-et-les-putschistes-nigeriens-la-confrontation-de-la-desintegration/).

Akindès, F., and Zina, O. (2016). L’État face au mouvement social en Afrique (The State and social movements in Africa). Rev. Proj. 355:83. doi: 10.3917/pro.355.0083

Alimata, D. (2019). Le recours à la force armée par l’Union africaine: contribution à l’interprétation de l’article 4(h) de l’Acte constitutif de l’Union africaine (The use of armed forces by the African Union: a contribution to the interpretation of Article 4(h) of the Constitutive Act of the African Union). Geneva: University of Geneva.