- Department of Political Science and Public Administration, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

This article discusses the role of big tech in becoming an engine of capturing public power. We focus on tech capitalist classes and their determination to capture both the economic benefit and the political decision. First, the article does so by bringing to the fore input from Weber’s political capitalism to explain the linkages between state and tech capitalists as the illustration of a structural dependence where lobbying activities are intensified. Second, pushing further the generally admitted idea of states and markets being co-constitutive allows to broaden the concept of political capitalism to include not only rent seeking, property rights’ issues, and surplus extraction mechanisms but also models of governance. The study suggests that in the case of digital capitalism, property rights on productive resources, originally private while also publicly subsidized, can make big tech not just shapers of common values but also providers of public goods.

Introduction

The rise of a new high-tech capitalist class has emerged in contemporary scholarship as the phenomenon of groups of individuals and entities (tech companies) forming a global, mobile, and connected technological elite (Castells, 2011; Evgeny, 2013; Fuchs and Mosco, 2016). If we understand ‘class’ in terms of power and not only of wealth and income (Zweig, 2012), then the transnational tech capitalist class brings together digital industrialists, venture capitalists, top tech executives, and engineers. It is a definition that broadens the conventional approach according to which a capitalist is primarily defined through his income from the ownership of capital (rents, dividends, interest payments, and capital gain). In this definition, a certain number of employees holding rare human capital have particularly strong bargaining power to negotiate the sharing of value to their advantage.

High-tech capitalists’ political influence on public policy and state functions is arguably an increasingly important issue. The phenomenon of state capture is mostly associated with corruption in developing countries while seen as a kind of a dystopian founding in relation to market ‘normality’ (Hellman et al., 2000; Rose-Ackerman, 2024). Liberal democratic theory treats capture mainly as a dysfunctional feature of the state and not of capitalism. This study proposes to analyze tech political influence arguing that it can be definitively treated as an issue of capture where more than rewards are to be seeking. The analysis of state capture as a structural feature of capitalism allows to develop the concept of digital political capitalism. The study makes the case for reconstructing the capital–state relation by challenging political capitalism’s usual mandate according to which economic elites use political power to secure economic privileges and entrench their wealth (Olson, 1982; Veblen, 2017).

The capital–state relationship seems otherwise disrupting in the case of the high-tech industry compared to the traditional corporate sector. This is a “new kind” of elite that responds to new conditions; beyond the ‘where they come from’ question—family and class background, accumulated capital and wealth as well as institutional position—the ‘how they operate’ question seems equally important (Savage and Williams, 2008).

This idea of the inextricable relation between the capitalist class and the state has again become popular since the financial crisis of 2008–2009. In 2011, W. Streeck affirmed emphatically “More than ever, economic power seems today to have become political power…” (Streeck, 2011, p. 29). Later, in 2017, R. Brenner stipulates the fact that we barely distinguish between political and economic elites crediting an undoubtedly fusional relation of capitalist classes with their governments (Brenner, 2017). No doubt, the financial and economic crisis of 2008–2009 has been a great opportunity for creating a large comfort zone for capitalist classes and preparing popular masses to accept the rational legitimation of unethical capitalism.

The study examines to what extent digital technologies are becoming engines of capturing public power. Political analysis needs to focus on this trend that is related to a much more comprehensive and intrusive restructuring of the capital–state relationship, giving rise to unceasing tech capital accumulations. First, the article does so by bringing to the fore input from Weber’s political capitalism to explain the linkages between state and tech capital as the illustration of a structural dependence where lobbying activities are intensified. Second, pushing further the generally admitted idea of states and markets being co-constitutive allows to broaden the concept of political capitalism to include not only rent seeking, property rights’ issues, and surplus extraction mechanisms but also models of governance.

Accumulations and new materialities

It is often claimed that semiconductors and microchips have become the modern world’s equivalent of oil, serving as a vital and (un)limited resource. Tech aristocracy1 has shown daring endeavors having built a very strong value system according to which entrepreneurial spirit and talent goes hand in hand with success and reward. The risk culture served as the main narrative about the ethical nature of venture capitalism. Silicon Valley has the highest concentration of venture capitalism. In fact, it is been a while since it started. Venture capitalism emerged in 1957 when the first venture capital-backed company was founded. Silicon was the first experiment of integrated complex finance-venture capitalist class. Since then, high technology has been related by blood to venture capitalism.2 M. Mazzucato has clearly shown the decisive role of government funding and academia in the seed stage of firm growth, while venture capital support comes in at a later stage (Mazzucato, 2013, pp. 54–57).3 Still, venture capitalists have a monopoly on the risk as a virtue; they propelled themselves to the forefront as an avant-garde of the so-called creative capitalism.4

Beyond narratives, what distinguishes this form of capitalism from other ones? Forty years later, we know more about what this specific type of industrial high-tech capitalist class is made of. In his ‘New Imperialism’, Harvey puts forward this idea of a dialectical relation between the territorial and capitalist logic to explain capitalist imperialism, insisting that although distinct and antagonistic, there are equally intertwined (Harvey, 2003, pp. 29–31). In digital capitalism, the state is not as Harvey says, “the political entity orchestrating capital accumulation over [external] space that works to its own advantage.” In his terms, the state being a powerful economic agent plays an important role in the process of capital accumulation when the capital is confronted with overaccumulation. Digital capitalism is disturbing because it gave rise to mega-economic conglomerates with unquestionable and a priori conquered de-territoriality for unceasing accumulations. In the face of an overaccumulation crisis, it runs less risk than traditional capitalism where the state has historically been called upon to resolve its contradictions. In other terms, digital conglomerates disrupt this clear-cut and contrasting reasoning which is composed of two kinds of power logics: territorialized political power and economic power as flows (Harvey, 2003, pp. 27, 29, 32).

High-tech capitalism also brought out new materialities, i.e., ‘a state within the state’. The architectural design of big techs’ campuses with their own streets and borders proposing a specific urbanity has many translations in terms of social and political meanings. Far beyond Marx’s fundamentals about the disconnection of the subject from its own materializations, high-tech industry brought out new materialities proposing the illusion of continuous connection. Silicon Valley’s technological inlands have also produced a new physical organization and work culture while often claiming social horizontality and inclusiveness.5 Bylinsky explains that in the mid of the 1980s, a new kind of collective identity shows up in Silicon Valley: “An extraordinarily egalitarian style of work prevails in which the boss listens to his associates as equals and where almost everyone shares the financial fruits of new technologies” (Bylinsky, 1985, p. 26).6 There was a common belief that this new capitalism could be socially beneficial, contrasting declining industrial capitalism (Joseph, 1989, p. 355). This has been the new myth nurturing neoliberal societies under a deafening silence that rattles continuously. Since then, low-paid labor and dead-end jobs have been denounced publicly.7 The technology will always be the reality of human hierarchy, domination (Demont-Heinrich, 2008), and violence.

Capture as the big play

Power capture occurring within public policy space was often referred to as state capture, and state capture issues have been largely dominated by neoliberal ideas since the 1970s through the major works of public choice theorists in economics. At that time, those scholars used the problem of state capture to serve conservative economic programs. This gave rise to the “overload thesis” explaining the fiscal crisis and ungovernability of the welfare state capitalism (Offe, 1982). Fiscal insolvency, weakening of the free-market economy, and corruption of political democracy were just a fraction of the symptoms of the state, which was seen incapable to carry out its purpose of providing social and economic wellbeing, thus succumbing to crony capitalism and corporatism.

State capture issues regained attention since the 1990s associating the phenomenon with systemic political corruption and cronyism in state-directed and post-colonial economies. In fact, in the mainstream regime transitions’ literature, state capture has been assimilated with the shaping of the rules of the game through the provision of private benefits to officials and politicians. No doubt, this tendency to see corruption and bribery as something that only happens in poor and weak countries and in non-western political regimes that did not embrace market democracy is a kind of orientalism.

The current discussion about political capitalism also seems to be oriented to some extent toward a very narrow and ideologically connoted conception of it. In a liberal version, Milanovic distinguishes between liberal and political capitalism. Under this typology, political capitalism, in other words state capitalism, refers to Chinese capitalism; the latter is seen as a contesting ideology in comparison with liberal capitalism which corresponds to the contemporary Anglo-American version (Milanovic, 2019, pp. 91, 127).8

According to another right-libertarian perception, state capture is an endemic feature of contemporary states and is related to the political (over)regulation of market capitalism (Holcombe, 2018).9 In this study, underlying this approach is the idea of minimal state. This means that, within the political geometry of capture, the state, being not capable of preventing public officials from abusing their office for private gain, is a failed institution that should be further limited. High-tech capitalist class seems to adopt this radical right-libertarian perception; its resistance to unionization of the tech workforce is a good illustration of its way to perceive the role of trade unions and labor movements in the digital-platform economy.10 This trend is coupled with the fact that tech capitalist structures include commercial competition and markets but also linkages with state structures.

It seems necessary to pursue the reflection of the powerlessness of the state which is related to the evolution of the capitalist structures in the digital period. The dominance of tech giants with a private monopoly hold over algorithmic regulation and digital communications is not only just a rent-seeking issue but also a social issue on privacy. It relates to political and social power capture generating gains by using domination; in Weberian terms, this could be described as a ‘non-rational form of political capitalism’. According to M. Weber, non-rational forms of political capitalism include gains derived from force or domination, war, and colonialism before the emergence of the state. Weber refers to a “multiplicity of non-rational forms of capitalism” in Antiquity and in the Middle Ages in contrast to the modern times where capitalism is elevated into a system with the rise of competing national states. These forms of political capitalism do not develop within the technical legal order of the rational market-oriented capitalism (Weber, 1950 [1927], p. 240). From antiquity onwards, non-rational forms of capitalism include “capitalistic enterprises for the purpose of tax farming, financing war, trade speculation, money-lending capitalism, exploiting the necessities of outsiders” (Weber, 1950 [1927], pp. 125–126). In the case of tech giants capturing the state, their gains are not just about extracting economic profit but also about controlling the diffusion of ideas, values, and exporting new modes of governing. In this sense, state capture in the digital age does not amount to just rent-seeking problems, but it relates to political and social power capture.

Rational political capitalism in the digital age

In his conceptualization of rational political capitalism, Weber explains that the advent of the market is the signal of the emergence of the rational state, as the new technical legal order, and of rational capitalism, as the modern economic order.11 Rational capitalism appeared in the Middle Ages and elevated into a system in the modern western world where a rational system of labor organization was developed. M. Weber affirms that the alliance of the state with capital was dictated by necessity under which arises the bourgeoisie. By rational forms of political capitalism, Weber means the capitalist system that is entirely relative to state and governmental opportunities, such as leasing of the territory, tax farming, financing of political adventures, and wars. This kind of forms influences the public policy in a decisive way. Before the advent of Western modernity, a rational capitalistic class appeared for the first time in late Rome (Weber, 1950 [1927], pp. 125–126). Interestingly, unlike his sociological classifications where he separates the political from the economic through the famous three-component theory of stratification—class, status, and command—his rational political capitalism puts forward the idea that rational capitalist classes played a determining role in the state.

Contemporary critical analysis needs to stipulate that this trend does not just equate to institutional arrangements related to cronyism stricto sensu. In fact, it is related to a much more comprehensive and intrusive restructuring of the capital–state relationship. No doubt, the gains are, although not solely, economic returns on capital through direct allocation, deregulation and privatization, public procurement or usure, detaxation, leasing and appropriation, or by using crypto-colonial practices. In fact, political elites able to direct allocation to the private sector with low regulatory constraints act less evidently as state technocratic brokers of the public interest in the marketplace, partisan constituency, or organization builders and more as private agents (Innes, 2016).

Following Weberian methodology, the conditions for the development of the rational form of political capitalism in the high-tech sector are met, including non-bureaucratic organization, governing power being dependent from the capitalist power for provisions, and financial power’s access to the most lucrative sources of wealth. In digital capitalism, as Weber would say, the tech capitalistic class is, although not entirely, relative to state and governmental opportunities, and for that reason, it is very much concerned about the way of regulating the sector. The rational form of political capitalism can take different forms such as transactions with political bodies and authorities, predatory profit from political organizations or persons connected with politics, and profit opportunities in unusual deals (Weber, 1978 [1922], pp. 164–166).

Although the above features apply to digital capitalism, there is a slight difference in the balance of power since it is the tech capitalist class which is the broker of capital’s power in the state. This is an important point to try to get a better understanding of how digital political capitalism works. This means that there are also political gains on authority through the externalization of legislation making, the privatization of forms of public governance, and the increasing blurring of private–public space. In this sense, it seems appropriate to reframe the concept of political capitalism thus covering a large spectrum of issues, such as state mechanisms of surplus extraction (Riley and Brenner, 2022), as well as corporate social practices based on capture and new patterns of private–public governance.

Some commentators contend that contrary to other markets, tech platform markets are characterized by a unique confluence of structural characteristics, such as strong network effects, economies of scale, economies of scope derived from user data, and consumer tendencies to single home. As gatekeepers for extremely costly key digital ecosystems and setters of the rules, their dominant position is almost a natural monopoly (Ducci, 2020, p. 74). This is even more alarming as far as the extent of dependence is concerned given the fact that government(s) agencies are customers of data brokers.

In a certain way, the creation of digital space depended on the arbitrary granting of a privilege by the US administration. A lesson of the history of capitalism is that private capital is considered a more reliable form of wealth management than state action.12 The state patronage of digital capitalism has a long history. In 1984, the Reagan administration came up with the Chips Protection Act to protect potential profitability of the tech sector. Until then, the lack of intellectual property protection for tech architects was resulting in an innovative design falling between a copyright right and a conventional patent.13 By enacting the Chips Protection Act, the US Government enhanced a process of accumulation by dispossession through the objectivation of human mental and physical activity; it created a ‘closed market’ based on the appropriation of resources and the exclusive ownership of digital production and knowledge, thus revealing the hierarchical logic of the sector. The Chips Act serves both tech capitalist interests and US national interests in the inter-state competition, especially in relation to China. U. Pagano notes that intellectual monopoly capitalism has become a dominant form of organization of big business since the mid-1990s (Pagano, 2014, p. 1410). In 1997, the Semiconductor Industry Association was created with the aim of protecting industrial interests and eliminating predatory action like market dumping with potential competitors such as Japan—as it was the case at the time of the Reagan administration. In 1998, the Clinton administration signed the FAIR Act for the privatization and commercialization of the Internet. This law was the result of a common agreement with public and private interest groups. On the one side, national commercial interests were a matter of priority (Grosse, 2020); on the other side, it was important to comply with business groups’ requests who had been trying for a year to push even more for a full-bodied legislation.

In Graeber’s terms, the US administration behaves as primarily as ‘protector of corporate property’ (Graeber, 2001, p. 89). This could explain why the debate on digital monopolization, which is mainly structured around two possible approaches, either aggressive enforcement of the Federal Sherman Antitrust Act or new legislation at state-level, grew so heated only in the last couple of years. Αntitrust has resurfaced as a topic of both popular and political concern and now “stands at its most fluid and negotiable moment in a generation”.14 Since the intensification of the global race on artificial intelligence (AI), the debate on how to regulate the technology industry became vivid. According to the dominant discourse, antitrust laws could harm US global competitiveness, especially in relation to China where there is no limit to obtain data. The pressure is on the federal government—especially the Pentagon—to increase its investments in artificial intelligence. AI serves as the new alibi for not changing capitalist property structures in the sector.

The tech capital–state complex

A critical feature of digital capitalism is that tech capital is less dependent on the world economy than the other segments of the capitalist class, while intra-capitalist global rivalries in the tech sector are not for the time being so aggressive. There is no need to “move” industrial capacity since they can benefit from lower wages and non-regulations in third countries without delocalizing (unlimited labor force). Polanyi insisted on the “independence” of high finance from single government and central banks—but in touch with all. His idea was merely related to a functional approach about the position, organization, and techniques of high finance (Polanyi, 1957, p. 10).15 By transposing Polanyi, tech capitalists are hyperglobalists as the Rothschilds were internationalists. In this sense, big tech companies benefit from a highly uneven distribution of extraterritorial privileges, while they have unlimited raw material of data, knowledge, and human intelligence at their disposal. High-tech architects create digital environments that reflect, explicitly or implicitly, their cultural bias and emerge with values and communicative preferences embedded in them (Ess, 2009, p. 116). However, although digital spaces rely on public infrastructures, they cannot be a terrain to be contested. This form of digital organization—reminding sometimes more of a counterrevolution—is distorted by a kind of mobilization of bias which is so diffuse that it cannot be captured in action, rule, or speech (Debnam, 1975, p. 894; Schattschneider, 1960).16 In this sense, what digital capitalism shares with imperialist and colonial practices is the fact that high-tech forces conduct their policy toward a colossal mass of users who throw themselves in digital consumption often driven by irrational motives17 (unlimited mass of users).

As the history of capital–state relations showed, tech intelligence is a crucial US diplomacy and foreign (military and cyber) policy tool, and for that reason, vertical and horizontal concentration of the big tech industry has been a condition sine qua non for the deployment of American digital policy.18 The development of the tech state-capital complex is of major political importance not only for internal/external reasons linked to state-surveillance and propaganda policies but also for dominance reasons. Big techs are measured as indices of the US hegemony in the rivalry between the Chinese State and American corporate digital capitalism (Arrighi, 2007).19

The agglomeration of knowledge hubs is made possible by publicly funding the concentration of digital power from the very beginning and for decades. Among high-tech industries, Silicon Valley became the place of a tech labor aristocracy, which was built as the epicenter of the West Coast high-tech industrial-academia-Pentagon-financial-bipartisan law-makers complex. This interdependent public–private structure has evolved into one of the dominant contemporary forms of the capitalist state. Eisenhower’s preoccupation with too much influence from industrialists linked to the Department of Defense in the 1960s—a period marked by the arms race linked to the Cold War—looks completely outdated. The ties between campuses and industry were decisive from the very beginning to compose these new tech-intellectual labor forces.20

States have power precisely because of their ability to define property rights and thus draw the boundary between public and private activity. The way they draw that boundary determines the nature of capitalism in any specific market (Schwartz, 2012, p. 520). The main problem of our time is the unprecedented concentration of property rights over the means of production in the history of capitalism (Lapavitsas and the EReNSEP Writing Collective, 2023, p. 36). In terms of property and ownership regime, big tech companies are one of the most powerful segments of the capitalist class on a world scale. Of course, venture capitalists have indirect property rights over these companies and so over productive resources, and this builds complex property relations. Tech capitalists as a transnational capitalist class control not only the collection, management, processing, and analyzing of data but they also largely command what is called ‘knowledge concentration process’, i.e., the means of production, distribution and exchange, and concentration of productive knowledge.21

Forging alliances with the US binary political system

In the 2020 Congressional report about high-tech companies, the House panel concluded, “To put it simply, companies that once were scrappy, underdog startups that challenged the status quo have become the kinds of monopolies we last saw in the era of oil barons and railroad tycoons”.22 In keeping with the precepts of republicanism, economic and financial elites have always supported the idea that checks and balances on power accumulation endanger public interest.

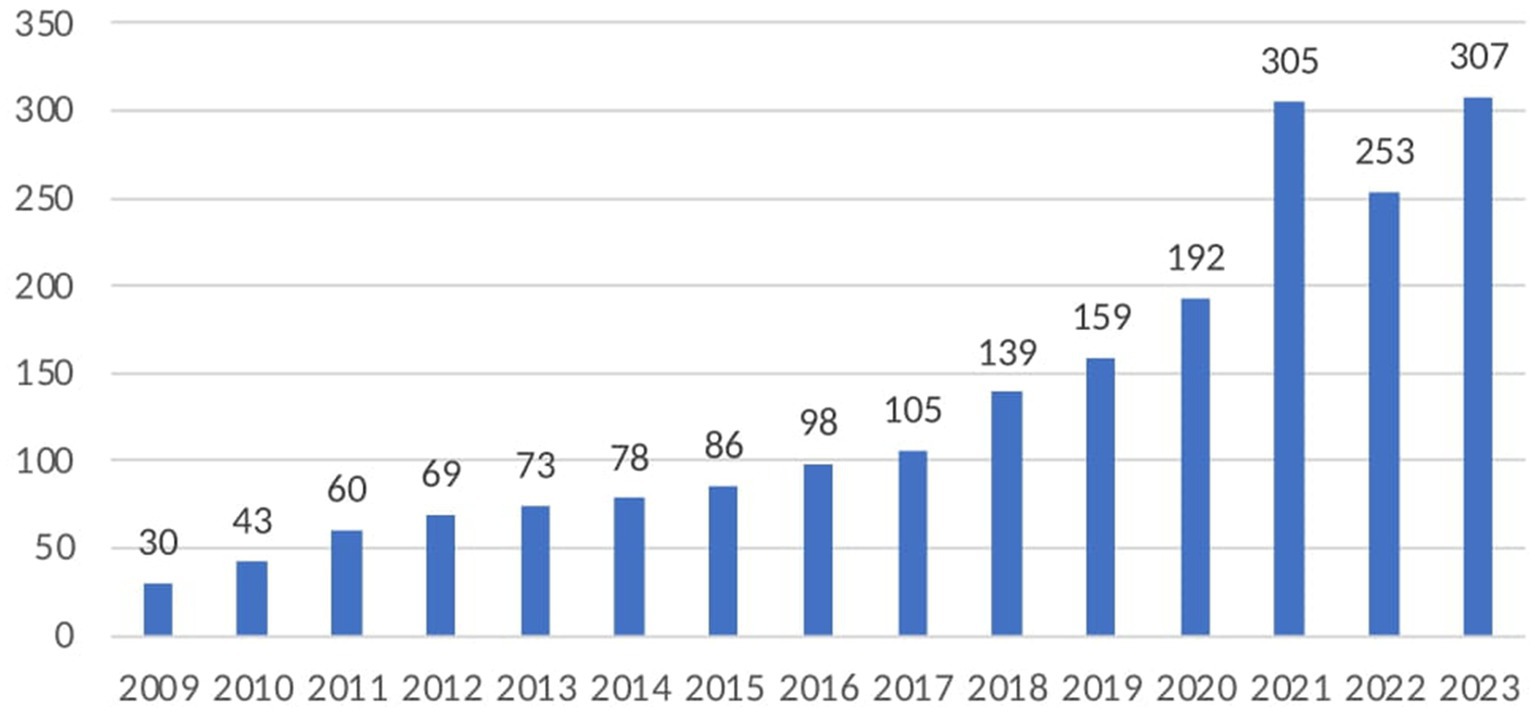

Big tech companies have created an opening to influence legislative debates through their expertise, favor political inaction, or obtain favorable political decisions; while behaving like “external legislators,” the politics of capture allowed accumulation of political power. Big tech companies face politics as “organized combat” (Hacker and Pierson, 2011). By occupying a dominant position for more than a decade, technological elites managed to evolve their anti-competitive monopoly tactics. This unusual deal in favor of a self-regulated—or more accurately non-regulated—sector created huge profit opportunities (see Figure 1); securing their gains gives them important leverage to deal with US political authorities.

Figure 1. Net income (earnings) of GAFAM, billions of dollars. Source: Annual Reports 2009–2023, GAFAM, author’s calculation.

Recent US administrations have so far been unable to rattle the current regime consisting of public funding, protectionist measures, and self-regulation, which reflects the tradition of commercial republicanism originally rooted in the history of American capitalism. A common political agenda has been built on a collaborative base between the Big-tech and US governments at least since Obama, promoting a variety of issues such as “freedom of speech on the Internet, uncensored and free flow of information on an unrestricted Internet.” During the Trump administration, Democrats in Congress introduced unsuccessfully a series of bills, such as the Accountable Capitalism Act and the Anti-Corruption and Public Integrity Act, which addressed, among others, lobbying and campaign finance regulation. In 2019, E. Warner proposed a plan to rollback acquisition by technology giants influenced by the German corporate governance model and lobbying. The Biden administration issued an executive order to tackle corporate monopolistic practices in major industries, except of the tech industry where the increased scrutiny of abusive business tactics was only addressed. Despite congressional hearings in 2020 with tech top executives, congressional historic investigation and research, and bipartisan-backed proposals, no comprehensive tech laws have passed. The antitrust trial US v. Google LLC, which owns a 90% market share, has been of capital importance mainly because it could endorse or not endorse a regime of digital exclusivity in new markets such as AI. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia found that Google violates section 2 of the Sherman Act.23 Google’s fate will be determined in the next phase of proceedings; it remains quite uncertain whether or how this could result, as some say, in anything from a mandate to stop certain business practices to a breakup of Google’s search business.

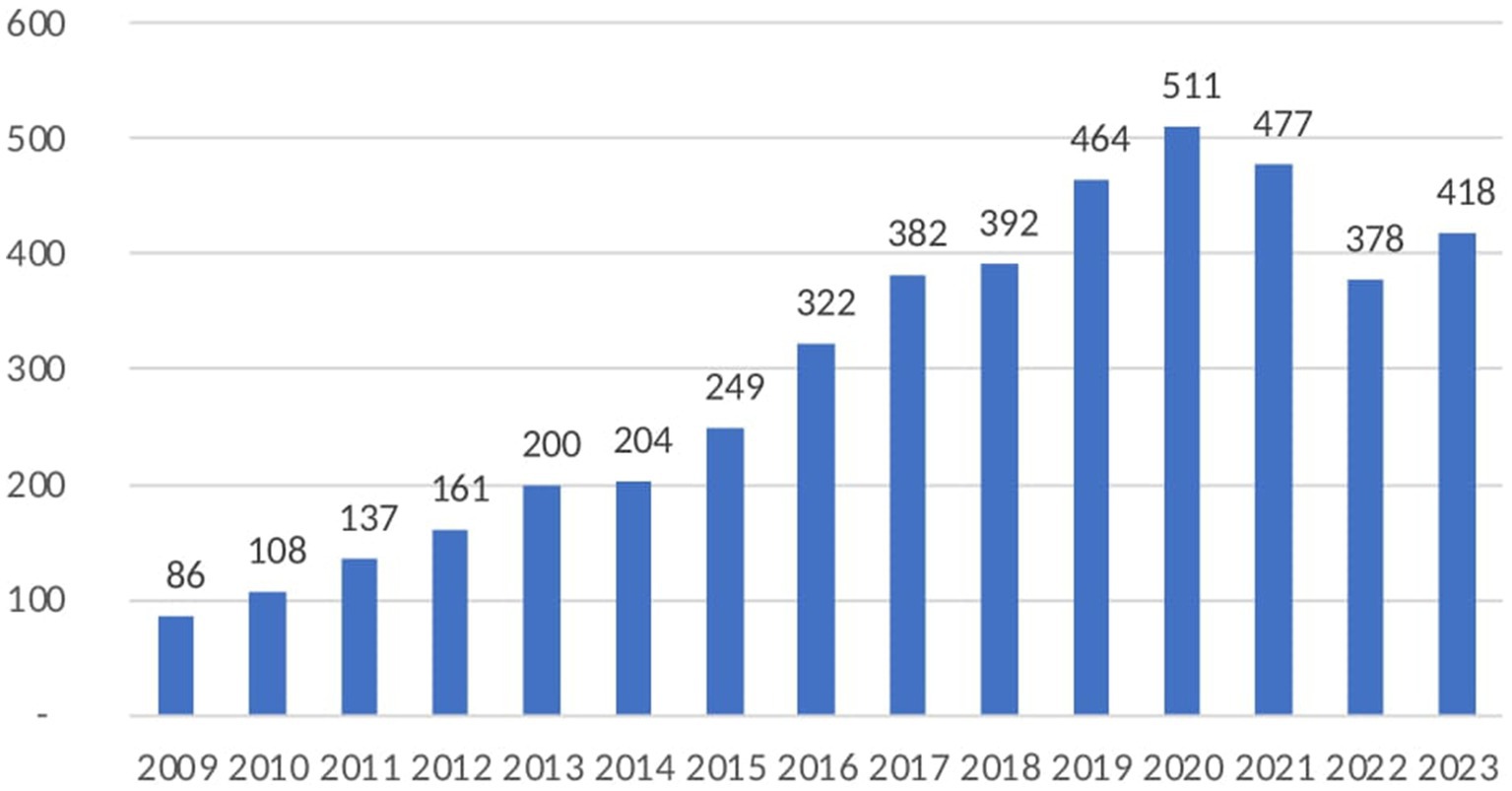

As previously said, in digital capitalism, capital accumulation is much less dependent on political processes. However, this does not mean that there is not a development of predatory profit from political organizations or persons connected with politics.24 GAFAM sound money is fundamental to gaining politico-economic power (see Figure 2) since they can operate without relying on banks while pouring capital into political lobbying itself to obtain returns. Notably, software and IT hardware are still the dominant sectors in 2023 for venture capital investment accounting for roughly 42.8% of all deals in the US.25

Figure 2. Cash on hands, billions of dollars. Source: Annual Reports 2009-2023, GAFAM, author’s calculation.

The intensification of lobbying in the last 15 years focused on controlling the transactions with US political authorities as well as government agencies and on hijacking the policy agenda on digital technology law, policy, and regulation in relation to digital trade interests and tax breaks. Since 2017, it seems that the number of lobbyists and gatekeepers employed by big tech companies that worked previously for the US State or political officials (revolving doors phenomenon) has been steadily increasing.26

Google has become an aggressive lobbyist increasingly vocal on several policy issues, including net neutrality, spectrum allocation, freedom of speech, and political transparency (Yong Jin, 2016). Since 2010, there is an increase in big tech lobbying activities through corporate PAC contributions, while Apple appears as the lowest spender among them. It is worth noting that Apple’s last political contribution (PAC) goes back to 2012. Google and Meta (Facebook) see their contributions, respectively, increase since 2012, while Microsoft has been a long-standing contributor since the 2000s. These big tech companies, except for Apple, tried to establish ties with key legislators or members of the political executive, government officials, or other political gatekeepers or veto wielders, by joining the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).27 Despite companies’ executives professed liberal stance, when push comes to shove on key policies that threaten the high-tech sector’s core interests, these firms have joined ALEC’s conservative coalition (Hertel-Fernandez, 2019, p. 130) to protect their bottom lines in 2013 for a short period of time; they interrupted their membership at the end of 2014. The official reason given for Google and Meta was that they disagreed with the very conservative views of the organism on climate change and so on. In fact, as previously noted, they have witnessed an exponential growth of their structural power (in terms of profitability as well as market value, market capitalization, etc.). Along with this development, lobbying spending in US Federal departments and institutions shows an important increase after 2014.28 Apple’s particular strategy could be interpreted as nothing but the power coming from the specificity of its business model by virtue of which it is exempted from some traditional practices of political capitalism. If we examine more carefully lobbying spending paths, we see repetitive feedback loops where big tech lobbying spending is directed to targeted Federal departments that provide subsidies and conclude procurement contracts.

As previously said, high-tech industries have the reputation to be more liberal-leaning (Silicon Valley’s liberal brand), even more, to be identified with the left especially on social issues; in this sense, tech sector leaders have been shown to be more supportive of efforts to address issues increasingly identified with the Democratic Party (climate change and immigration). However, except for Apple—in which there are no solid data available, Google, Facebook, and Microsoft donations through PACs are slightly higher when it comes to the Republican Party, while GAFAM donations go to think tanks both conservative and liberal. Until and during the Obama presidency, the GAFAM could flourish without hindrance. When observing the fluctuation of PAC contributions’ rate, we notice that near the end of the Obama presidency in 2016, the donated amount is the highest in the long run. In the light of the 2017 Presidential election, boosting the direct financing of US political parties deemed necessary given the rising pressures to mitigate the socio-economic effects of digital corporatocracy (Suarez-Villa, 2009, pp. 37, 178–197). Shifting returns to capital over labor have economic consequences (inequality and freezing wages) as well as political consequences (growing concentration of economic and political power, increased corporate lobbying power), thus jeopardizing the prospects for inclusive growth (Warner and Xu, 2021, p. 52).

Discussion: toward a tech ‘public capitalism’?

This provides an opportunity to discuss capture not only as an economic component but as a political, cultural, and theoretical component of the theory of governance and of the state. This (re)conceptualization of political capitalism goes a step beyond the Polanyian thesis about markets as complex public–private institutional landscapes embedded in society.

Etzioni noted the growing reliance on computer and Internet technology further undermines the status of the public sector as the provider of security. He shows how the outsourcing of state activities through private contracts can lead to ‘annex’ portions of the private sector to accomplish the public sector’s objectives (Etzioni, 2017, pp. 55–56). Although Etzioni was a moderate scholar and he focused on security issues, the merit of his analysis is that he describes in functional terms this evolving relationship between state-capital. In this context, explaining the linkages between state and capital as the illustration of a structural dependence is no longer sufficient. Jessop explains that state capacities are seen as extra-economic supports of the capitalist mode of production. Although he reiterates the fact that the market and the state are complementary components of the capital relation, he observes that there is a ‘variable institutional’ separation between the legal and political system and the accumulation process for profit in the global market (Jessop, 2015, p. 4).

What is different in digital capitalism is that property rights on productive resources, originally private while also publicly subsidized, can make big tech not just shapers of common values but also providers of public goods. Tech capitalists’ determination to capture both the economic benefit and the political decision reminds us of Mahon’s ‘public capitalism’, which is described as a mode of legitimation of corporate power; in this vein, corporate power is converted into a social authority exercised in concert with governments (McMahon, 2012).

In this sense, political capitalism acquires a much broader significance structured around three axes: (a) corporate social practices based on capture through lobbying, (b) state mechanisms of surplus extraction where the role of the state as the facilitator of capitalist profitability and accumulation, and (c) (old and new) patterns of private–public governance where corporate power gains in mass policy and political influence that could boost its profitability by an indirect means. Venture philanthrocapitalism is not something new, but its further expansion in the form of a kind of tech paternalism is not only a useful tool for corporate propaganda but also opens a new field for tech ‘public capitalism’.

Colonial periods with imperialistic goals were a context giving a public role to private companies.29 However, this kind of new political capitalism could go a step further than existent public–private governance patterns that we also experienced in the corporate milieu through their co-optation with state structures. It could also make a difference with other private oligopolies that are almost exclusively using their political connections to make money at the expense of taxpayers through the most classical cronyist practices. This trend could be related with the rise of AI as a regulatory science30 controlled to a very large extent by high-tech companies. The impact of the new AI industrial model on public policy content may become increasingly decisive; it can generate profits by guiding political decision.

In the realm of a new ‘political capitalism for the people’, voices are raised promoting the idea that corporations should promote democracy internally and externally and act to provide public goods in instances of governmental incapacity (Windsor, 2019, p. 15; Zingales, 2012).31 Is this about a new kind of capitalism where politicization is seen as an opportunity to create a competitive advantage, or is this about business ethics or rather about business having a political and social role?

In relation to the latter, we find a hotchpotch of current ideas about considering business not only as an economic but also as a political institution. Zammit-Lucia calls this “a new political capitalism” as a trend of great importance in the future.32 He insists that the nature of capital–state relationship enters a new face where capitalist class’s (social) awareness will act as a catalyst for considering the stakes facing society nowadays (Zammit-Lucia, 2022).

In this spectrum, the idea of the 1990s according to which private elites and profit-driven companies run the system exclusively to their own advantage is outdated. Old practices such as using their structural coercive power by deciding when and where to allocate their funds depending on the implementation of specific policies by the public authorities or using the ‘threat of exit’ or the ‘promise of entry’ to motivate political actors to implement specific policies that are in line with their interests still matter, but businesses cannot ignore politics; they can potentially have an intrinsic role in initiating politics and consequently serve public functions.

Here, we are one step beyond familiar forms of public–private–philanthropic partnerships. Corporate philanthropy is nothing new, but its further expansion in a kind of technological paternalism is not only a useful tool for corporate propaganda but also opens a new field for corporate political governance. Traditionally, the development of corporate propaganda is used as a mean of protecting corporate power from democracy (avoiding government policies and countering opinion campaigns) while having a strong influence on public choices of society.

Beyond lobbying, donating to both conservative and liberal think tanks33 and promoting voice strategies to shape public debate and public opinion, high tech capitalists could undertake more direct governing action thus breaking democratic rule. This was the case when Silicon Valley billionaires and philanthrocapitalists funded projects in schools in the US promoting the start-up culture in contrast to the bureaucratic model of public life.34 The fabric of ‘public’ entrepreneurship through the development of High-Growth Tech Nonprofits marks a trend in tech corporate political governance.35 ‘Public’ entrepreneurship activities may concern healthcare planning, infrastructure improvement, local welfare, human rights, education funding, etc. Digital corporate political activism could potentially increase if governments’ role seems insufficiently democratic and often incompetent. It might be easier for these interest groups since the high-tech sector endures less dependence of capitalist profit on government measures, in contrast with other corporate sectors which, because of feeble accumulation, show greater dependence.

Author contributions

FC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research leading to these results stems from the research project ‘Political capitalism and repertoires of business actions: drawing lessons from the U.S. experience’ at the University of California, Berkeley, which has received funding from the Fulbright Greek Scholars Program 2023–2024.

Acknowledgments

For discussions on the topic and comments on the paper, special thanks to Dylan Riley, John Lie, Steven Vogel, and Neil Fligstein, University of California, Berkeley as well as to Wai Kit Choi and Louis Esparza, California State University, Los Angeles. I am also thankful to two reviewers at Frontiers in Political Science for their comments and suggestions on the earlier version of the paper.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The term ‘tech aristocracy’ is meant to design a social class that combines capitalistic characteristics with some hyper-elitist features who appeal to a new kind of nobility. If we follow Weberian methodology, tech aristocracy is defined by a kind of class permanence succession which creates the conditions of a hereditary appropriation where there are different strata of compulsory labor culture with joint liability, the workforce but also the users are in a different way engaged in forms of compulsory contributions which create a form of servility.

2. ^Fairchild Semiconductor (FCS), one of the earliest and most successful semiconductor companies founded in 1957, was the first venture capital-backed startup, setting a pattern for venture capital’s close relationship with emerging technologies in the San Francisco Bay Area. In 1946, the first venture capital firm called American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) was publicly funded.

3. ^However, in the case of Silicon Valley, entangled in a relationship of interdependence, the Federal government and the defense industry were in need of what FCS would be built, while the military market has been of great importance for the company. See Interview with Interview with Regis McKenna, Silicon Genesis: oral history interviews of Silicon Valley scientists, 1995–2022, min. 55′, August 1995. See https://exhibits.stanford.edu/silicongenesis/catalog/gh775dk3836.

4. ^J. Schumpeter drew a distinction between financial capitalists and industrial entrepreneurs; what he termed ‘export monopolism’ was related to the capitalist social group with real material interest that monopoly capitalism created through the fusion of entrepreneurial cartels and high finance. See Schumpeter (1919). Reprinted as Schumpeter (1989 [1951]). The same kind of process has taken place in digital capitalism with the fusion of high-tech entrepreneurs and venture capitalists, thus becoming a social group with great political weight. Since the 1970s, venture capitalist rushed to get in, thus gradually replacing the US military and NASA as the financial backbone of the industry.

5. ^Regis McKenna, founder of Regis McKenna, explains that the innovation spirit of this time gave rise to integrated groups of work; the work method of “team” requires very hard work and progress reports. Interview with Regis McKenna, Silicon Genesis: oral history interviews of Silicon Valley scientists, 1995–2022, min. 50′, August 1995. See https://exhibits.stanford.edu/silicongenesis/catalog/gh775dk3836.

6. ^R. Noyce, the co-founder of Fairchild Semiconductor, hated management and the bureaucracy of East coast companies. While he made no distinction between management and workforce, he placed a high priority on teamwork being in favor without hesitation of unlimited work. See the documentary, Silicon Valley: American Experience, season 25, episode 3.

7. ^Dead End in Silicon Valley. The high-tech future does not work, Quality Electronic Service, Q. E. S. Article addresses occupational health hazards in the electronics industry, 1985.10.01, Digital Public Library of America. See https://history.santacruzpl.org/omeka/items/show/76133#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0.

8. ^For Milanovic “the key distinction is that under liberal capitalism the state is ‘an “enabling” and passive actor’, while under political capitalism the state intervenes in the economy actively and directly.” Milanovic refers to the active role of the State in shaping the economy while leaving prices, wages, and many investment decisions to the private sector. In Milanovic’s political capitalism, bureaucracy plays an important role in realizing high economic growth and implementing appropriate policies. He stipulates the risk of transforming liberal capitalism into political capitalism in case the capitalist elite uses its economic and political influence, while he makes a clear distinction between ‘private sector meritocrats and government officials’.

9. ^R. Holcombe discusses his idea of political capitalism as a dysfunctional system per se; he reiterates the strong belief of rational choice theorists according to which capitalism is a self-sufficient system thus implicitly supporting the illusory idea of absolute market autonomy.

10. ^Public choice theorist J. Buchanan strongly insisted on the paternalistic influence of pressure groups with sectoral—and not specific as public choice scholars usually suggested—interests (trade unions, labor movements) referring to their so-called ‘privileged position’. Buchanan was a member of the Mont Pelerin Society sharing some common beliefs with F. Hayek and T. Friedman although he was not considering himself belonging to the Austrian or Chicago Schools (Buchanan, 1984).

11. ^While early Western liberalism is based on the artificial separation between the economic and the political, Adam Smith also recognized the cycle of wealth and political power that linked him to the “old corruption” and warned that their gains would hurt England.

12. ^In his article on the French Crédit Mobilier in the New York Daily Tribune in 1856, Marx describes in detail the activities of this anonymous company whose creation, as he notes, depended on the arbitrary granting of a privilege by the Government (Louis Napoleon Bonaparte). For Marx, “making industry of public works in general dependent on the favour of the Crédit Mobilier” was patronage (Marx, 1856).

13. ^Interview with George Scalise who had positions at Motorola, Fairchild, AMD, Apple, and the Mac Store; President of the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), Former Chairman, Federal Reserve Bank San Fran, Silicon Genesis: oral history interviews of Silicon Valley scientists, 1995–2022, min. 42′, April 2003. See https://exhibits.stanford.edu/silicongenesis/catalog/vb434zb8007.

14. ^Crane (2018, p. 118) in Congressional Research Service Antitrust Reform and Big Tech Firms, Updated November 21, 2023, p. 1.

15. ^Polanyi explains that when the era of protectionism and colonial expansion begins, high finance is at its peak. The Rothschilds, the aristocracy of Bourse expanded firstly internationally and then to a national setting.

16. ^The concept of mobilization of bias was developed by Schattschneider referring to how power structures can shape political action while creating the (false) impression that the result is due to community’s involvement.

17. ^This observation echoes Schumpeter’s analysis on the importance of irrational, ideological precapitalistic elements in the rise of imperialism in the late 19th century, having striking similarities with Kautsky who insisted on the role of precapitalist reactionary strata on imperialism.

18. ^H. Feis showed in an astonishing and unique way how world finance and national diplomacy were intertwined on the side of national governments in the pre-war period. Feis explained that to a marked extent in all of the lending countries, direct or indirect governmental control of the directions and amounts of foreign investment was exercised and was used as a major tool of governmental diplomacy and political control abroad. The manipulation of financial power to further national political ambitions abroad was the almost inevitable consequences of this injection of political considerations into the process of foreign investment. The pre-war international debts, though in some directions they did much to promote the peace of the world, clearly did much in other directions to disturb it (Feis, 1964, p. 193).

19. ^G. Arrighi showed that the Chinese state disposes of a high degree of relative autonomy from the capitalist class, which enables it to act in the national rather than in a class interest.

20. ^In certain aspects, as if there was a pattern of reproduction, these skilled intellectual workers bring to mind the Chinese farmers in the 19th century who were induced to manage White Anglos’ land for an increased rate of profit. See Harris (2023, p. 37). Jim Koford, CEO of Monterey Design and a pioneer in the semiconductor industry, says that a world class university in engineering emerged in Stanford University after the WWII by the end of 50s, noting that “people were building the foundations of the digital era without knowing it,” min 3.50′, Silicon Genesis Oral Histories of Semiconductor Technology, min 59′, August 1998. See https://exhibits.stanford.edu/silicongenesis/catalog/rw617hp4903. The longstanding strategy of students’ recruitment in UC, Berkeley is explained by P. Gray. He notes that Asian American students are a good recruitment pool at undergraduate level and non-US-Asians coming from Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, at postgraduate level because they are very qualified and talented and work very hard. He admits that “we could not build this industry without them.” Interview with Paul Gray, Dean of the College of Engineering, UC, Berkeley, Silicon Genesis: oral history interviews of Silicon Valley scientists, 1995–2022, min 59′, August, 1998. See https://exhibits.stanford.edu/silicongenesis/catalog/yx277kf9163.

21. ^It is worth noting that algorithmic innovations happen outside the University.

22. ^Investigation of competition in digital markets, Majority staff report and recommendations, Subcommittee on anti-trust, commercial and administrative law of the committee on the judiciary, US 2020, p. 6.

23. ^United States, et al. v. Google LLC, Memorandum Opinion, Case No. 20-cv-3010 (APM) (D.D.C., Aug. 5, 2024), see https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/attorneygeneral/documents/pr/2024/pr24-59-Google.pdf (“Google Search decision”).

24. ^In the Weberian perspective, this includes the financing of wars, political adventures or revolutions, but also the financing of party leaders by loans and supplies.

25. ^Note from NVCA, NVCA 2024 Yearbook, March 2024, p.22, see https://nvca.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/2024-NVCA-Yearbook.pdf.

26. ^Otherwise, the GAFAM run their own “in house” political advocacy agencies while they are very much involved in the main industrial associations of the country (Internet Association, Computer and Communications Industry Association, Information Technology Industry Council).

27. ^ALEC is a coalition of big businesses, conservative right-wing activists, and wealthy donors that organize corporate political activities focusing on crafting state policy around the principles of free-market enterprise, limited government, and federalism. Being recognized as the conservative branch of the Republican party, it focuses on voter ID law, preventing LGBTQ legal rights expansion, fighting against labor activism, aggressive national regulation, green policies, and immigration. Facebook and Google were interested in sponsoring and participating in specific working groups such as the telecommunications policy task force while they were showing readiness to promote initiatives to address climate change outside of the ALEC framework.

28. ^On PACs (Political Action Committees) and contributions received from the GAFAM see opensecrets.org, https://lda.senate.gov/system/public/.

29. ^The first imperial experiment that was based on private capital’s endeavour was to British East India Company, EIC, 1600–1858. The Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, VOC, literally United East India Company) was founded in 1602, when the Dutch parliament granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia.

30. ^Regulatory science refers to corporate-led scientific activities that contribute to regulating industrial activity.

31. ^This approach is often labeled political corporate social responsibility that can substitute for government; in reality, it is more than that since it links brand activism with corporate political activity.

32. ^J. Zammit-Lucia is the business executive and founder of the think tank for the radical centre Radix. Among other interviews, he also presented his book to Apple’s podcasts.

33. ^Total donations from GAFA to the four think tanks—Center for Strategic and International Studies (centrist), the Center for a New American Security (close to the right-wing of Democrats), Brookings (centrist) and the Hudson Institute (conservative)—increased from at least $625,000 in 2017–18 to at least $1.2 million in 2019–20, Financial Times, February 1, 2022. See https://www.ft.com/content/4e4ca1d2-2d80-4662-86d0-067a10aad50b.

34. ^See https://cepr.harvard.edu/news/silicon-valley-billionaires.

35. ^Such examples are WattTime, A High-Growth Climate Tech Nonprofit (Gavin McCormick), Rocket Learning, A High-Growth Education Tech Nonprofit (alumni of Indian Institute of Techs, Indian Institute of Management, Harvard and reputed companies and NGOs) or Rediviz, a High-Growth Criminal Justice Tech Nonprofit (Leader Google). See https://www.recidiviz.org/about.

References

Buchanan, J. M. (1984). Can democracy be tamed? Paper presented at General Meeting of Mont Pelerin Society, Cambridge, September.

Bylinsky, G. (1985). Silicon Valley high tech: Window to the future. Hong Kong: International Publishing Corporation.

Debnam, G. (1975). Nondecisions and power: the two faces of Bachrach and Baratz. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 69, 889–899. doi: 10.2307/1958397

Demont-Heinrich, C. (2008). The death of cultural imperialism-and power too? Int. Commun. Gaz. 70, 378–394. doi: 10.1177/1748048508094289

Ducci, F. (2020). Natural monopolies in digital platform markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Etzioni, A. (2017). The fusion of the private and public sectors. Contemp. Polit. 23, 53–62. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2016.1213074

Graeber, D. (2001). Toward an anthropological theory of value. The false coin of our own dreams. London: Palgrave Publishers Ltd.

Grosse, M. (2020). Laying the foundation for a commercialized internet: international internet governance in the 1990s. Internet Hist. 4, 271–286. doi: 10.1080/24701475.2020.1769890

Hacker, J. S., and Pierson, P. (2011). Winner-take-all politics how Washington made the rich richer--and turned its Back on the middle class. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Harris, M. (2023). A history of California, Capitalism and the World. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company.

Hellman, J. S., Jones, G., Kaufmann, D., and Schankerman, M. (2000). Seize the state, seize the day: an empirical analysis of state capture and corruption in transition economies. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 2444, 1–41.

Hertel-Fernandez, A. (2019). State capture how conservative activists, big businesses, and wealthy donors reshaped the American states -- and the nation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Holcombe, R. G. (2018). Political capitalism: How economic and political power is made and maintained. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Innes, A. (2016). Corporate state capture in open societies: the emergence of corporate brokerage party systems. East Eur. Politics Soc. 30, 594–620. doi: 10.1177/0888325416628957

Jessop, B. (2015). Political capitalism, economic and political crises, and authoritarian Statism. Spectr. J. Global Stud. 7, 1–18.

Joseph, R. A. (1989). Silicon Valley myth and the origins of technology parks in Australia. Sci. Public Policy 16, 353–365. doi: 10.1093/spp/16.6.353

Lapavitsas, C.the EReNSEP Writing Collective (2023). The state of capitalism, part II the state and domestic accumulation at the Core. London: Verso.

Marx, K. (1856). “The French Crédit Mobilier”, the People's paper, no. 214, June 7, signed K. M. And also in the new-York daily tribune, no. 4735, June 21, unsigned.

Mazzucato, M. (2013). The entrepreneurial state: Debunking private vs. Public Sector Myths. London: Anthem Press.

McMahon, C. (2012). Public capitalism: The political authority of corporate executives. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Milanovic, B. (2019). Capitalism, alone: The future of the system that rules the world. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Offe, C. (1982). Some contradictions of the modern welfare state. Crit. Soc. Policy 2, 7–16. doi: 10.1177/026101838200200505

Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations: Economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press.

Pagano, U. (2014). The crisis of intellectual monopoly capitalism. Camb. J. Econ. 38, 1409–1429. doi: 10.1093/cje/beu025

Polanyi, K. (1957). The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origin of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (Ed.) (2024). Public sector performance, corruption and state capture in a globalized world. London: Routledge.

Savage, M., and Williams, K. (2008). Elites: remembered in capitalism and forgotten by social sciences. Sociol. Rev. 56, 1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2008.00759.x

Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The Semisovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt, Brace.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1919). The sociology of imperialisms. Germany: Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1989 [1951]) in Imperialism and social classes. ed. P. M. Sweezy (Fairfield, New Jersey: Augustus M. Kelley).

Schwartz, H. (2012). Political capitalism and the rise of sovereign wealth funds. Globalizations 9, 517–530. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2012.699924

Suarez-Villa, L. (2009). Technocapitalism: A critical perspective on technological innovation and corporatism. Temple University Press.

Warner, M. E., and Xu, Y. (2021). Productivity divergence: state policy, corporate capture and labour power in the USA. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 14:1.

Weber, M. (1978 [1922]). Economy and Society. An outline of interpretive sociology. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Windsor, D. (2019, July). Accountable capitalism, responsible capitalism, and political capitalism: The Warren proposal for an Accountable Capitalism Act. In Proceedings of the International Association for Business and Society 30, 12–25. doi: 10.5840/iabsproc20193)03

Yong Jin, D. (2016). “The construction of platform imperialism in the globalization era” in Marx in the age of digital capitalism. eds. C. Fuchs and V. Mosco (Leiden: Brill), 322–349.

Zammit-Lucia, J. (2022). The new political capitalism: how businesses and societies can thrive in a deeply politicized world. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Zingales, L. (2012). A capitalism for the people: Recapturing the lost genius of American prosperity. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Keywords: state capture, elites, political capitalism, lobbying, high-tech, Silicon Valley, GAFAM, governance

Citation: Chatzistavrou F (2024) Political capitalism in the digital era: reconstructing the capital–state relation. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1509376. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1509376

Edited by:

Antonio Castillo-Esparcia, University of Malaga, SpainReviewed by:

Federico Tomasello, University of Messina, ItalyAndrea Moreno Cabanillas, University of Malaga, Spain

Copyright © 2024 Chatzistavrou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Filippa Chatzistavrou, ZmNoYXR6aXN0YXZAcHNwYS51b2EuZ3I=

Filippa Chatzistavrou

Filippa Chatzistavrou