- 1Berlin Graduate School of Social Sciences, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Berliner Institut für Empirische Integrations-und Migrationsforschung (BIM), Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 3Graduate School of Economic and Social Sciences (GESS), Universität Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany

Introduction: Social media has become a central part of everyday life, providing spaces for communication, self-expression, and social mobilization. TikTok, specifically, has emerged as a prominent platform for marginalized groups, providing opportunities for activism and representation. However, research falls short in examining the specific role of TikTok for Muslim women in Germany who face intersecting forms of marginalization. This shortcoming reflects a broader lack of research on the experiences of marginalized groups within TikTok’s logics and affordances, and what functions the platform fulfills for these communities. Against this backdrop, this study examines TikTok’s role as a platform for Muslim female content creators in Germany and its broader implications for marginalized communities. Our research is guided by the following questions: (a) What are the main themes and topics that are being brought forward by Muslim women content creators on TikTok? (b) What technical affordances do they use to communicate their content? (c) What functions does TikTok fulfill for Muslim women as an intersectionally marginalized group?.

Methods: We analyze 320 videos from 32 public TikTok accounts identified through snowball sampling. Data collection includes automated web scraping, manual transcription, and qualitative coding. This allows us to identify main topics, video formats, and content types to answer our research questions.

Results: Our findings show that Muslim women produce diverse content on TikTok, ranging from beauty and lifestyle to religious education and social justice. They shape the platform’s functionalities through creative use, while TikTok’s algorithm and virality logic drive creators to blend entertainment with personal content. The hijab emerges as a unique issue, framed within both political and fashion discourses. Overall, TikTok functions as a “third space” where Muslim women challenge mainstream stereotypes and offer alternative interpretations of their identity. While TikTok provides empowerment and visibility, it also exposes Muslim women to hate speech and harassment. The platform provides tools to counter these issues, but the underlying social hierarchies often limit their visibility, making TikTok both a site of empowerment and vulnerability.

Discussion: This study highlights the need for further research into the role of social media for marginalized groups, particularly across platforms, gender, and religion.

1 Introduction

Social media has become an essential facet of everyday life, deeply embedded in various spheres. It not only provides platforms for communication, networking, and information exchange but also functions as a marketplace and a medium for self-expression and self-representation (van Dijck, 2013; Feher, 2021). Additionally, social media plays a pivotal role in facilitating social mobilization and fostering counter-discourses, thereby shaping the political fabric of society (Poell and Borra, 2012; González-Bailón et al., 2013; Theocharis et al., 2014; Brown et al., 2017).

One such social media platform, renowned for both its popularity and notoriety, is TikTok. In recent years, TikTok has expanded its user base globally, hosting one of the largest and youngest user demographics. TikTok stands out among social media platforms by providing a substantial amount of entertaining content and a sophisticated algorithm that adeptly matches the diverse interests of its users (Bhandari and Bimo, 2022). Another feature that has significantly contributed to TikTok’s popularity is its unique curation approach, which enables users to generate a substantial number of views for their content. Unlike other platforms that predominantly recommend content from followed accounts and factor in the prior performance of an account and its followers, TikTok’s algorithm does not solely show content from followed accounts, nor does it consider follower count or previous high-performing videos as direct factors in its recommendation system. This allows lesser-known, and lesser-followed accounts to generate viewership, even among users who are not their followers, serving as an incentive for more users to engage in content production with the potential for substantial reach (TikTok, 2020; Zhang and Liu, 2021).

A considerable body of literature has emerged around the use and user experiences on TikTok (Cervi, 2021; Cheng and Li, 2023; Ling et al., 2023; Pan et al., 2023), its specific affordances (Schellewald, 2023; Zhao and Wagner, 2023), gratifications (Vaterlaus and Winter, 2021), and how users understand and interact with TikTok’s algorithm (Bhandari and Bimo, 2020; Zhao, 2020; Hödl and Myrach, 2023; Issar, 2023). These studies are concerned with the interaction between TikTok’s technical workings and human behavior, exploring how users engage with the platform and its technical features. They also delve into the quest to decipher the exact workings of TikTok’s algorithm, which remains a central focus for users, companies, and scholars alike, as it determines content curation and influences virality and marketing dynamics. Another strand of literature that is more grounded in sociological inquiry explores social dynamics and implications on TikTok focusing on questions of (self-)representation, identity construction (Barta and Andalibi, 2021; Civila and Jaramillo-Dent, 2022) and community building as well as (political) mobilization and activism (Abbas et al., 2022; Cervi and Divon, 2023; Hotait and Ali, 2024).

Extending this research, recent studies have highlighted TikTok’s significant role in providing a platform for minority activism and representation (Vizcaíno-Verdú and Aguaded, 2022; Hiebert and Kortes-Miller, 2023; Lee and Lee, 2023). Drawing on frameworks from post-colonial and feminist studies, as well as other social justice perspectives, these studies illustrate how minorities—such as Black women, Asian/American women, LGBTIQ communities, and Muslim women—have utilized TikTok to resist and counteract stigmatization, discrimination, and exclusion. While these studies provide valuable insights into the potential use of social media platforms to challenge conventional social power structures and contribute to a more egalitarian and democratic culture, they tend to be either limited to the issues of discrimination and stigmatization or focus on specific political moments or events. This approach often ignores the potentially diverse ways in which minority groups engage in the digital sphere, concerning not just social grievances or political action. This is particularly true for Muslim women, where the body of literature is still limited regarding what they use TikTok for and how the platform’s technical affordances guide this usage. Given this research gap to date, we set out to explore the themes and topics that Muslim female content creators address on TikTok and how they make use of the features available on the platform.

Our study focuses on Germany, which is home to the second largest Muslim population in Europe, with 5.3–5.6 million Muslims (Pfündel et al., 2021). This choice provides a compelling backdrop, as it represents a significant layer of the intersectional experiences of Muslim women being both a religious and often ethnic minority. The various layers of their experiences, shaped by minority status, race, ethnicity, religion, and gender, make them a particularly illustrative sample for exploring the potential of TikTok for marginalized groups in general.

Our research is guided by the following research questions: (a) What are the main themes and topics that are being brought forward by Muslim women content creators on TikTok? (b) What technical affordances do they use to communicate their content? (c) What functions does TikTok fulfill for Muslim women as an intersectionally marginalized group?

Grounding our research in previous work that has examined the opportunities and threats that social media pose to women and racialized minorities, we present our basic assumptions and our key theoretical concepts. We then explain our methodology including a description of the sampling strategy, the sample, the data collection, and our coding and analytical strategy. In line with our research questions, we identify the most salient topics in our data to get a sense of the main issues Muslim women are concerned with in the digital sphere. We then provide an overview of the most common video formats to address the technical affordances utilized and content types, examining the various styles in which topics are presented. To gain a deeper understanding of Muslim women’s use of TikTok and the purposes it serves, we analyze the overlap between topics and the overlap between topics, content types, and video formats. Our discussion summarizes key findings and discusses limitations and prospects for future research on social media, particularly TikTok.

Our key findings suggest that Muslim female content creators present a wide range of different topics, from fashion and beauty, product promotion and commerce to religious and theological knowledge sharing, social justice and political advocacy, using the technical affordances of TikTok in creative ways. Many of their videos deal with ordinary issues that resonate with mainstream discourses. However, Muslim women’s content stands out for representing their intersectional lived experiences based on their religious, ethnic, racial, and gender identities. While TikTok serves as a Third Space for Muslim women, offering new forms of self-expression and the articulation of hybrid identities, we show that the modes of representation selected are very much shaped by the nature of the content, the logics of TikTok, and current trends.

With our study, we contribute to the literature on Muslim women in non-Muslim majority contexts and their representation in online spaces. We further show how social media platforms, such as TikTok, are used by minorities and point to the potentials and limits. Finally, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of TikTok’s technical affordances and how they influence and transform forms of digital representation. This includes not only comprehending how these technical features are utilized but also examining the types of representations they foster, allow, and facilitate.

1.1 Muslim women in non-Muslim majority contexts

A considerable body of literature has emerged in recent decades that explores Muslim women’s representation and activism, both offline (Bullock, 2005; Povey, 2009; Wadia, 2015; van Es and van den Brandt, 2020; El Sayed, 2023) and online (Piela, 2012; Eckert and Chadha, 2013; Islam, 2019; Hirji, 2021). Particularly in light of the hypervisibility of Muslim women through public controversies over religious clothing and conduct, and the simultaneous absence of their voices in these debates, these studies have contributed to a more complex and nuanced understanding of Muslim women and their lived experiences in Muslim minority countries.

Studies within the framework of sociology of religion have focused on Muslim women’s religious practices and religious interpretations, both in Muslim majority and Muslim-minority contexts (Bendixsen, 2013; Brünig and Fleischmann, 2015; Zempi, 2016; Topal, 2017; Biagini, 2020; Paz and Kook, 2021). Those focusing on Muslim women within Muslim minority countries examine how religious practices have been reconciled or transformed through diasporic experiences and/or transnational movements. Particular attention has been paid to the significance of the hijab, Muslim women’s interpretation of religious norms and Islamic sources, and to space-making for Muslim women within traditional Islamic institutions (Kuppinger, 2012; Spielhaus, 2012; Wang, 2017; Hammer, 2020). The last decades have witnessed a shift in researching Muslim women solely in terms of their Muslim identity, thus primarily as religious agents, to a conceptualization that allows Muslim women to be perceived through multiple identity markers. This has entailed a perception of Muslim women both as active citizens and as racialized minorities who are limited by structural constraints rather than an inherently oppressive religion. While theological questions and dynamics within Muslim communities continue to draw scholarly attention, sociological research on Muslim women has increased.

As several empirical studies indicate, Muslim women, especially those who are visible through the hijab, continue to experience frequent discrimination and exclusion that affect their mental health (Yeasmeen et al., 2023), social and political participation, and socioeconomic positions (Beigang et al., 2017; Weichselbaumer, 2020). Scholars have adopted the concept of gendered Islamophobia to analyze the multiple discriminations against Muslim women on the basis of their gender, race, ethnicity, and religion (Chakraborti and Zempi, 2012; Perry, 2014; Alimahomed-Wilson, 2020; Zempi, 2020). While the gender-sensitive lens has primarily served to describe the intersectional experiences of and impacts on Muslim women, it has also proved useful in understanding the gendered racialization of Muslim men (Selod, 2019; Wigger, 2019; Yurdakul and Korteweg, 2021).

1.2 Muslim women in the digital space

With the advent of the Internet, new opportunities have emerged both to actively counter discrimination and stigmatization to create safer spaces in which the experiences of minorities can be shared and in which community members can offer each other help and support (Piela, 2012; Islam, 2019; Durrani, 2021; Hirji, 2021; Khamis, 2021; Civila and Jaramillo-Dent, 2022; Vizcaíno-Verdú and Aguaded, 2022; Gatwiri and Moran, 2023).

Our research on Muslim female content creators on TikTok builds on an emerging body of scholarship that examines Muslim women’s use of the Internet and their expressions and experiences in cyberspace. Similar to other demographics, Muslim women’s presence in digital spaces has increased significantly over the past two decades, attracting scholarly interest in both Muslim majority contexts such as Indonesia, Kuwait, and Turkey (Kavakci and Kraeplin, 2017; Baulch and Pramiyanti, 2018; Beta, 2019; Karakavak and Özbölük, 2022) and in Muslim minority contexts such as the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands (Kavakci and Kraeplin, 2017; Pennington, 2018a; Islam, 2019; Mahmudova and Evolvi, 2021; Arab, 2022). Given the dominance of private platforms and channels in the 1990s and 2000s, and the previously limited public representation of Muslim women in virtual spaces, early studies have focused primarily on Muslim women-only spaces such as newsgroups and blogs (Akou, 2010; Piela, 2012). While one strand of literature focuses on how Muslim women engage in and shape religious discourses online (Akou, 2010; Piela, 2010b, 2012; Pennington, 2018b), another strand explores Muslim women’s activism, particularly against anti-Muslim racism and sexism, both within mainstream society and within Muslim communities (Pennington, 2018a; Islam, 2019, 2023; Hirji, 2021; Khamis, 2022). A significant number of studies in the field of Muslim women online have adopted a progressive perspective, highlighting the potential of the Internet—and more recently—social media to foster religious discourses that promote gender equality in Muslim communities. One example is the pioneering work of Anna Piela (2012), who examines the religious discourses of a transnational newsgroup. Her findings suggest that the newsgroup allows Muslim women to connect across physical borders and discuss gender-related religious issues in a safe(r) space. Due to the private nature of this space and partial anonymity, Muslim women are able to share sensitive issues and test arguments that may be useful in other analogous contexts. While Piela highlights the potential for critical reflection and questioning of religious norms and the exchange of alternative interpretations, she also observes a reproduction of conservative positions by some women (Piela, 2012). This demonstrates the ambiguous nature of the Internet in enabling a variety of discourses that are not necessarily liberal or progressive. However, as Piela points out elsewhere (Piela, 2010b), “Whereas Muslim women professing different views on gender relations in Islam tend not to engage in dialog with each other in the off-line world, they participate in a common online debate which is more likely to result in shared understandings” (Piela, 2010a, p. 425).

With the growing popularity of new social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok, and the prevalence of visual and audio-visual forms of representation, Muslim women have gained increased visibility online by capitalizing on new technological affordances available to them (Nisa, 2021; Khamis, 2022; Hotait and Ali, 2024). For instance, they have used social media to enact and negotiate their hybrid identities by displaying different expressions of the hijab and promoting new modest fashion styles (Arab, 2022; Khamis, 2022; Poulis et al., 2024). As demonstrated by Kavakci and Kraeplin in their study of hijabi social media personalities (2017), Muslim women’s fashion style is significantly influenced by mainstream fashion, while modest fashion has made its way into the mainstream through the normalization of religious bodies in the digital sphere. As a consequence, “the line between modesty and immodesty, religion and culture is blurred through the process of mediatization“(Kavakci and Kraeplin, 2017, p. 864) and the meaning of the hijab is challenged and transformed (Kavakci and Kraeplin, 2017; Arab, 2022; Karakavak and Özbölük, 2022). Consistent with other research (Beta, 2019; Poulis et al., 2024), the study shows that Muslim influencer’s self-representation online is further driven by market-logics. Thus, social media should be conceptualized not only in terms of its ability to empower Muslim women and promote inclusivity, but also as a marketplace driven by economic incentives and commercial interests (Poulis et al., 2024). Beyond their aesthetic representation as hijabistas and fashionistas, Muslim women use social media for political activism (Islam, 2019; Hirji, 2021; Khamis, 2021). While Twitter in particular has been known to be used for political mobilization, Instagram and TikTok have been perceived more as entertainment-based platforms (Cervi and Marín-Lladó, 2022). However, in the last few years there has been a rapid growth in academic research on political activism on TikTok (Medina Serrano et al., 2020; Cervi and Marín-Lladó, 2022; Civila et al., 2023; Literat et al., 2023; Moir, 2023). In their explorative study on pro-Palestinian activism on TikTok, Cervi and Marín-Lladó (2022) illustrate how female influencers exploit TikTok’s technological affordances to express solidarity with and support of the Palestinian cause. Identifying a new form of digital activism, “playful activism,” the authors illustrate how female content creators “capitalize[…] on popular subculture, the make-up culture, transforming it into an act of resistance, completely breaking off from the traditional narrative” (Cervi and Marín-Lladó, 2022, p. 422).

In light of the rise of Islamophobia in Western societies researchers have researchers have paid increasing attention to how Islamophobia plays out in virtual spaces. Recent studies look at the impact and counter-strategies against hate speech, defamation and discrimination online (Islam, 2019, 2023; Hirji, 2021; Khamis, 2022). While these studies contribute to our understanding of Islamophobia and how Muslim women face it as an intersectionally marginalized group in virtual spaces, they obscure other life experiences and expressions of Muslim women. As a result, Muslim women only become visible in the context of discrimination and Islamophobia. While we acknowledge the importance of anti-Muslim racism for Muslim women as it affects their daily lives, we seek to highlight the diverse ways in which Muslim women engage online.

1.3 TikTok as a third space for Muslim women?

As shown by Sabina Civila, Mónica Bonilla-del-rio, and Ignacio Aguaded in their study of the hashtag #Islamterrorism on TikTok (2023), social media provides a space where counter-narratives can be articulated and publicly shared, challenging misconceptions about Islam that are present in mainstream media. They find that “TikTok allows [Muslim minorities] to seek recognition as well as to generate discourses that make their culture visible” (Civila et al., 2023, p. 10). To capture the specificity of social media as an in-between space and the dynamics and discourses it enables, particularly for marginalized communities, scholars have invoked the concept of the third space.

The concept of the third space has been popularized by the works of Bhabha (1994). According to Homi Bhabha, the third space is not primarily a physical space, but rather a social and cultural space characterized by hybridity. As such, the third space “enables other positions to emerge […] [and] displaces the histories that constitute it, and sets up structures of authority, new political initiatives, which are inadequately understood through received wisdom” (Rutherford, 1990, p. 211). In this sense, third spaces might be understood as “sites of resistance, where hegemonic and normative ways of seeing the world are challenged and, perhaps, transcended” (Pennington, 2018b, p. 622). Drawing on the notion of the third space which “exist[s] between private and public, between institution and individual, between authority and individual autonomy, between large media framings and individual ‘pro-sumption,’ between local and translocal” (Hoover and Echchaibi, 2023, p. 14) we explore what issues Muslim women raise and how they are expressed using the affordances of TikTok.

While empirical studies have demonstrated that digital third spaces are crucial for Muslim women to challenge stereotypes, subvert hegemonic discourses, and advance their struggles for social justice (Pennington, 2018b; Islam, 2019), scholars have also noted the limitations and risks of using social media. For example, Civila et al. (2023) have emphasized that visibility alone is not enough to overcome stigma and change the social status of minorities, but rather recognition. TikTok may facilitate greater visibility for Muslim women, who sometimes become celebrities with large numbers of followers and likes, but this does not automatically imply social recognition for Muslim women. This finding is also supported by Simões et al. (2023) whose “results suggest that the platform gives rise to ideas and discourses that reify unbalanced power relations” (2023, p. 244). In addition to these limitations, Muslims and Muslim women, in particular, are at risk of becoming victims of cyberbullying and/or misogynistic hate speech (Allen, 2015; Chadha et al., 2020). This confirms previous findings on women’s experiences in the digital sphere (Henry and Powell, 2015; Drakett et al., 2018; Eckert, 2018). In this sense, TikTok and social media more broadly represent an ambivalent phenomenon, that provides tools for empowerment and liberation, but also poses threats and risks, particularly to marginalized groups. In line with this observed double bind, we explore the extent to which this applies to Muslim female content creators on TikTok. Through insights into the multiple uses and functions that TikTok fulfill for Muslim women as an intersectionally marginalized group, we hope to illuminate recent developments and broader trends shaping Islam and Muslim life in Germany. We further show how Muslim women make use of the platform to represent and address their intersectional life experiences.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling strategy

The primary subjects of this study are Muslim female content creators based in Germany. Identification of individuals fitting these criteria was established through their self-identification as Muslim and female in their TikTok profiles or through their content explicitly. Our sample was assembled using a snowball sampling technique, initiated in August 2023 and completed in December 2023 concurrently with data collection. We began by searching for terms related to “Islam” and “Muslim” in conjunction with “Germany” and “Deutschland” on the TikTok webpage. The accounts identified served as a bridge to additional accounts suggested as similar by TikTok. All accounts were reviewed for clear self-identification as female, Muslim, and location in Germany as well; those not meeting these criteria were excluded. We acknowledge that this selection process is presumptive on our part, as it ascribes being Muslim based on explicit declaration. This approach may lead to selection bias by overlooking undeclared Muslim identities and potentially homogenizing this diverse group, as we only consider the subset of Muslim women who explicitly and publicly self-identify as such.

To ensure they display a certain impact on TikTok, we included only those accounts with a minimum of 13,000 followers. We posit that a substantial following indicates content relevance and resonance with its intended audience, thereby serving as a proxy for identifying the most socially pervasive and pertinent social patterns online. This specific threshold was determined after observing that accounts with smaller followings often lacked consistent content creation and engagement patterns.

The sampling process continued until the addition of new accounts ceased to provide additional variety or depth to our dataset. This approach yielded an initial pool of 42 public accounts. After eliminating accounts that were inactive, had removed their content, or had shifted to private settings by the time we collected the data, we finalized our sample at 32 accounts, representing the most engaged and influential actors for our set demographic.

2.2 Sample description

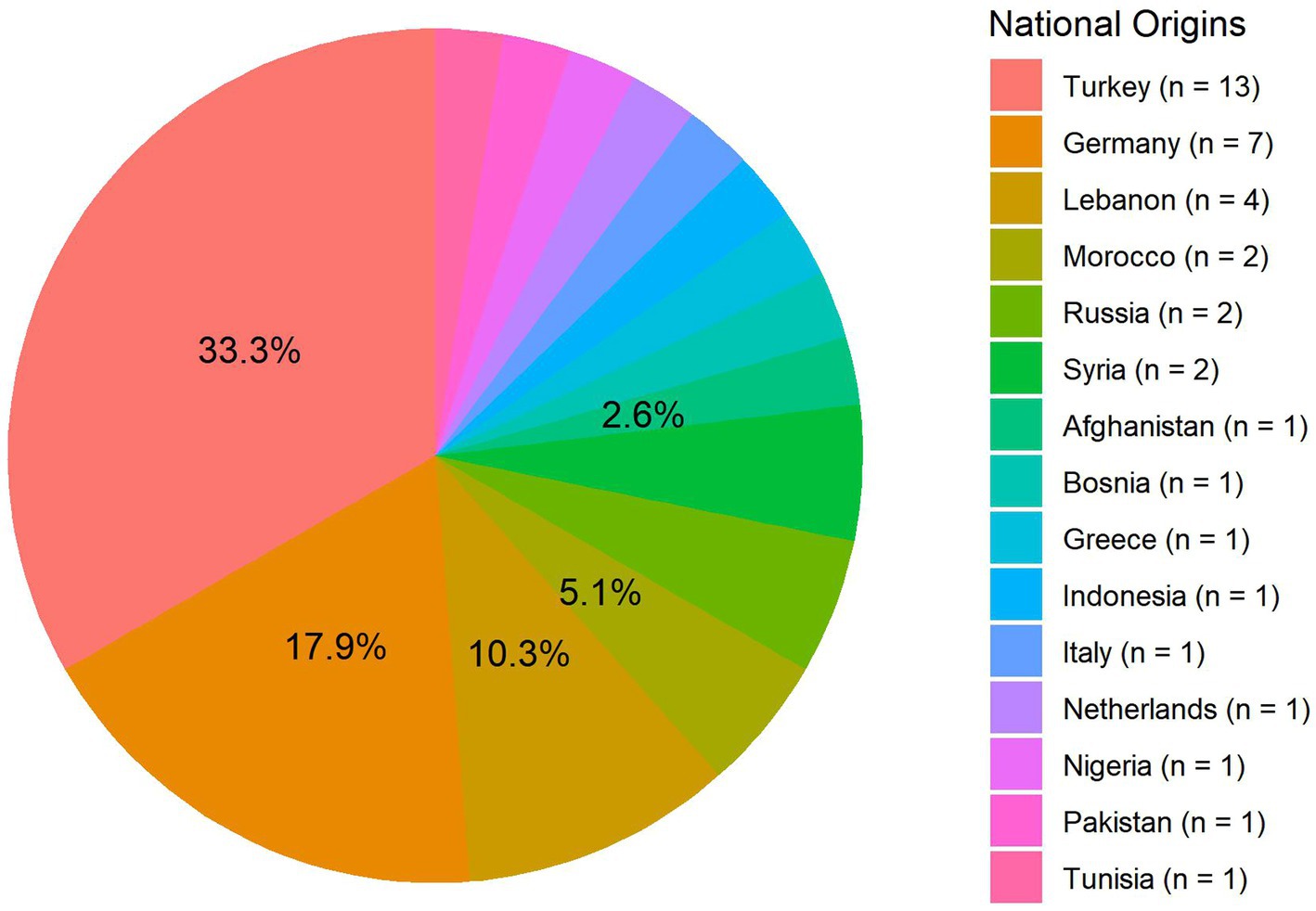

Out of 32 accounts, 29 are run by individual Muslim women, and three are run by cisgender couples (see Appendix Table 1). The decision to include couples corresponds to the simple fact that these couples consist of women who produce content related to their lives, whether individually, in relation to, or in collaboration with their partner. All of these accounts are relatively popular, supporting our earlier statement that our sample represents the most engaged and influential public actors for our set demographic on TikTok. The average views range from approximately 3,000 to around 785,000 views per video for one account (see Appendix Table 1). Our sample also represents a diverse array of national backgrounds, which were identified through various markers in the content. The majority (33%, 13 accounts) has a Turkish national origin (see Figure 1). The largest group by national origin among German Muslims is Turkish, with 45% (Pfündel et al., 2021, p. 42). Our sample further includes content creators of German (17.9%, seven accounts), Lebanese (10.3%, four accounts), Moroccan, Russian, and Syrian origin (5.1%, two accounts each). This not only demonstrates the national diversity of German Muslim content creators on TikTok, which is reflective of Germany’s Muslim demographic—largely consisting of individuals from Turkish and Arabic-speaking backgrounds, as well as those with German backgrounds, including converts and children of parents with mixed German and non-German heritage—but also showcases the diversity within our sample. This diversity is reflected in the mix of non-hijabi (4) and hijabi (28) women, some of whom wear the niqab, as well as the representation of followers of both Sunni and Shia denominations. At least one content creator, according to her testimony, wears the niqab for the sole purpose of protecting her privacy online.

TikTok is a dynamic platform where even popular accounts are sometimes deleted or set to private for an indefinite amount of time. As a result, observing a specific field or demographic on TikTok may only provide a snapshot of it at a given moment. Nonetheless, we tracked the availability of our sampled accounts as of July 2024 to ensure that the specific set of accounts we selected as representative of German Muslim female content creators, and therefore their content is still prevalent as we write. In fact, with the exception of two accounts, most are still available, either under their original or renamed handles (see Appendix Table 1).

2.3 Data collection

Data collection was split into two main methodologies: automated web scraping and manual transcription of video content. We employed web scraping to gather comprehensive data from each video across the 32 accounts, which included metrics such as the publication date, video description, duration, and engagement statistics (likes, views, shares, comments). This resulted in an initial dataset comprising approximately 9,000 videos. Collecting comprehensive video data allowed us to (a) select a random subset of the videos for qualitative analysis and (b) incorporate video metrics, like views, into our findings by matching them with our qualitative results.

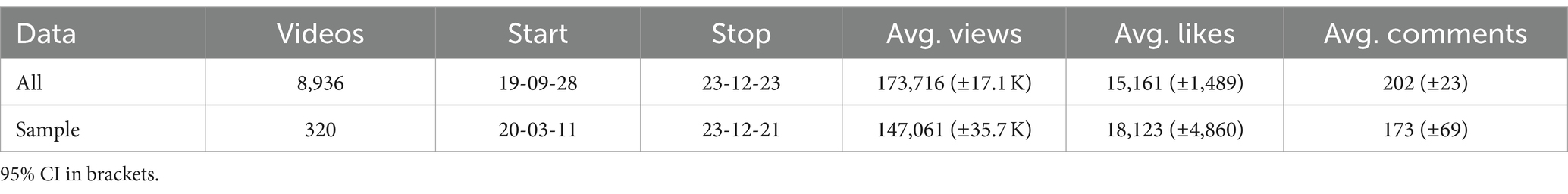

From this dataset, we randomly sampled 10 videos per account, totaling 320 videos, for deeper qualitative analysis. As illustrated in Table 1, the sample demonstrates similar distributions to the corpus of all videos in terms of the timeframe and the average metrics for the videos included. Through this assessment, we hope to ensure that our sample mirrors the spectrum of our content universe.

The selected videos were initially transcribed verbatim by the transcription service Amberscript, which handled all videos containing audible language. These initial transcriptions were subsequently edited and corrected by us to ensure accuracy. German quotes that were used to illustrate our findings were then translated by us into English. To safeguard the anonymity of our research subjects, we pseudonymized their usernames and paraphrased or aggregated any information that could identify their accounts. Driven by our goal to dissect the diverse topics, technical affordances and their functionalities, our transcriptions included not just the audio content but also relevant visual elements. Hence, wherever possible, we enriched our transcriptions with on-screen text, detailed descriptions of appearances, patterns of physical movements, depictions of scenery and objects, and the various video-audio techniques employed. This also ensured that content was elicited, even if audible elements were not available and hence, not transcribed by Amberscript.

2.4 Coding and analytical strategy

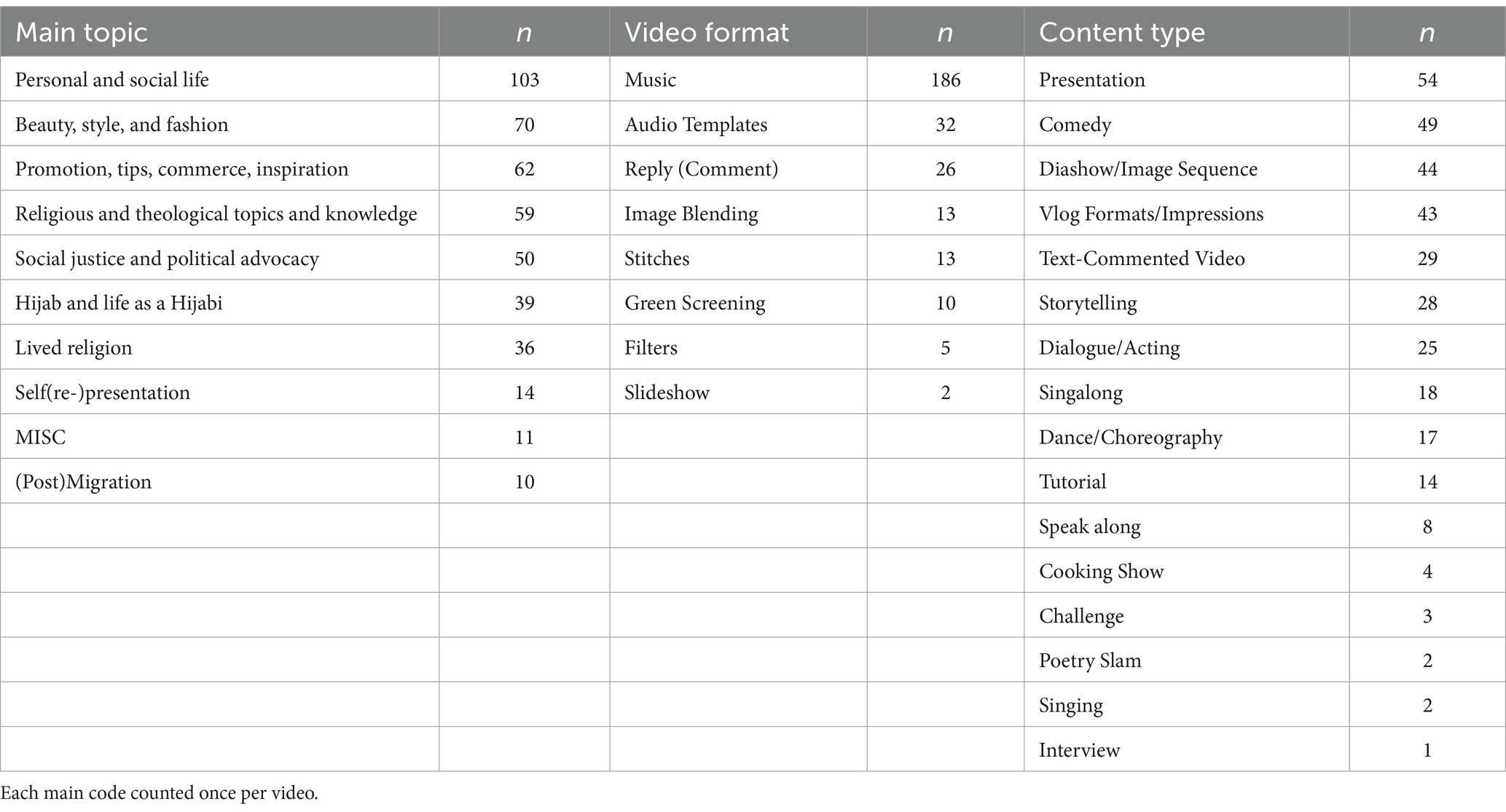

Our primary methodological approach was qualitative, utilizing coding of our transcriptions as the central hermeneutic tool. This approach allowed us to deeply engage with the data, guided by our specific research questions and epistemic interests. We implemented a hybrid coding strategy using the QDA software MAXQDA that blended deductive and inductive elements. Three deductive (a-priori) codes were established based on our predefined research interests, serving as our coding framework (see Table 2): main topics, video formats (TikTok-specific techniques, e.g., music, templates, green screen, stitches), and content types (e.g., vlog, comedy, tutorial). Working within these categories aligns with previous research that has recognized the relevance of content production forms, techniques, and affordances used by TikTok creators, as well as the functionalities these elements fulfill for users, such as advancing political activism (see Abbas et al., 2022; Cervi and Divon, 2023) or enhancing visibility more broadly (see Abidin, 2020). However, while these codes were initially outlined, they were populated with content extracted from the text without predetermined categories, maintaining openness in the coding process. For instance, while we aimed to code prevalent topics, we did not predetermine them, but rather identified them through the coding process inductively.

Our inductive coding strategy, while not a conventional application of grounded theory, significantly borrowed its coding methodology (Corbin and Strauss, 1990; Charmaz, 2006). We engaged in an iterative coding process that began with coding at lower levels of abstraction and gradually incorporated novel elements into our coding system. This process evolved until reaching higher abstraction levels, continuing until no new categories or patterns emerged, and data could be assigned to established codes. In this mode, topics were identified based on their salience within the video and their role in defining the overall content (subtopics, Appendix Table 2). These topics were then aggregated into broader main topics as the coding process progressed, based on their thematic connections (see Tables 2; Appendix Table 2). This iterative refinement was supported by constant memoing to track developments and insights throughout the coding process.

Each video served as an individual analytical unit, with the potential for multiple categories to be coded per video. To complement our qualitative findings and provide a broader view of the content landscape, we also conducted descriptive quantitative analysis of our coding categories. This analysis helped to outline the prevalence and distribution of our codes, providing a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play within our sampled TikTok content.

3 Results

3.1 Main topics

3.1.1 “Personal and social life”

The most dominant topic identified was “Personal and Social Life,” which appeared in 103 of the 320 videos sampled. It encompassed a variety of sub-topics including partnership and relationship dynamics, travel and living abroad, friendship, family life, school and university experiences, embarrassing moments, leisure activities, and general lifestyle discussions. The pervasiveness of the category “Personal and Social Life” is symptomatic of an ongoing trend toward a blurring of traditional boundaries between the public and private realm. Topics that were traditionally understood as private are increasingly shared on public platforms like TikTok. One classical example is found in one of PT29 videos, vlogging her day:

“Today is day 20, and I'm taking you along again. We always have a classic Turkish breakfast. But today, for a change, we had something Albanian, Speca me maze […]. We're heading to a henna celebration soon. I'll show you my dress. It's currently from H&M. I'm pairing it with these shoes from Deichmann”.

[The video shows her taking the bus and attending the celebration, including a full-body shot of her outfit. Afterwards, we see her back home, opening a box of pastries]

“[…] And I'll eat this now, and then that's it for today”

In that sense, the content creators resemble (online-)celebrities using private matters to gain social media popularity and increase parasocial interactions. “[W] hen celebrities share their life and directly communicate about theses [sic!] experiences, fans tend to feel as if those celebrities were socially present in their life” (Kim and Song, 2016, p. 574). Further, Marwick shows that the presentation of private life fulfills not one but several functions: “While micro-celebrities are supposed to reveal personal information to seem authentic, self-branders are encouraged to edit private moments in the name of brand consistency” (Marwick, 2013, p. 98).

Through their engagement in personal and often quite “wordly” topics Muslim female content creators display their multifaceted experiences challenging the societal perceptions that often define them exclusively through their religious identity. They claim space for self-representation that tends to be denied to them within mainstream media. Sharing insights into their daily lives that are relatable to non-Muslim audiences can break down stereotypical societal views that portray them as different or other (Chakraborti and Zempi, 2012).

Nonetheless, there are several actors who adhere to practices of privacy. PT4 never reveals her face in her videos, except when wearing a niqab, with a censor bar covering her eyes. In fact, throughout her TikTok profile, she frequently mentions that, from an Islamic perspective, she objects to showing herself publicly. Similarly, PT13, although she has content showing herself, either wears a niqab, avoids filming above her neck, or covers her face by holding her phone in front of it. PT27 explicitly states in her TikTok profile that she wears the niqab on social media for privacy reasons. So even though many creators reveal aspects of their day-to-day lives, many of them still adhere to a sense of privacy and engage in privacy practices, which, in some cases, are also explicitly justified from an Islamic perspective.

3.1.2 “Beauty, style, and fashion”

“Beauty, Style, and Fashion” was coded 70 times and includes videos such as clothing and outfits, makeup, and hair style. The category typically relates to how these creators showcase, navigate, and participate in broader beauty and fashion trends, reflecting their engagement with contemporary aesthetics. At the same time, it contains elements that emphasize their commitment to their faith as Muslims, featuring beauty and fashion items and styles that are compatible with Islamic norms. Thus, this topic not only reflects an overall trend among young women on social media capitalizing on their appearance (Zulli, 2018; Kennedy, 2020), but also indicates the rise of the modest fashion industry. Responding to the Western fashion industry’s failure to provide fashion that is both compatible with Islamic norms and stylish, these content creators are promoting brands, items and new styles that appeal to young, urban Muslim women. The fact that these creators not only display Islamic or modest fashion styles but also market Islamic brands demonstrates how marketable this fashion domain has become (Kavakci and Kraeplin, 2017; Arab, 2022).

One example showcasing the latest fashion trends and offering beauty advice, is a video by creator PT18, showing how she removes the dark circles under her eyes with a specific skin product. Another example is PT9, who provides a hijab tutorial. Furthermore, it highlights their authority in guiding discussions and setting trends in these areas toward their target audience, signifying the emergence of Muslim women as a new consumer group and target market (Pemberton and Takhar, 2021; Wheeler, 2022; Barta et al., 2023; Nugraha et al., 2023). This is illustrated by several examples in which content creators advertise beauty products or fashion items from specific brands, including Islamic ones, at times providing an affiliate link that offers discounts (e.g., PT5, P14, PT20). The inherent marketing and commercialization logic prevalent throughout TikTok is underscored once more by this dynamic (Barta et al., 2023). However, as a function of their self-branding on social media, by utilizing their looks and details about their private life for example, they constitute their bodies and life as “salable commodity” (Marwick, 2013, p. 166). Similarly to adherence to privacy, we see actors who engage in aspects of beauty or beautification to varying degrees. Some, like PT2, PT15, PT5, and PT8, participate in beauty topics with a focus on openly enhancing and presenting their physical or facial appearance through makeup and fashion. The former two include hairstyles, while the latter two emphasize hijab styles and a stronger adherence to modest fashion. In contrast, PT13 and PT17 avoid showing their faces, so their beautification focuses solely on the aesthetics of modest or Islamic clothing. Some creators do not seem to prioritize beauty topics or extraordinary beautification practices, regardless of whether they wear a hijab or not. This includes PT27 and PT30 who wear a niqab, PT3 who wears a hijab, and PT16 who does not wear a hijab. These are accounts where other topics take precedence over beauty content. Within the same actor, such as PT5, one can observe varying practices of beauty and modesty in fashion, ranging from blends of Western fashion styles with her hijab to more orthodox Islamic clothing, including abayas and traditional hijab styles. The varying and diverse adherence to Islamic concepts like privacy and modesty reflects the diversity and blend of conservative, orthodox, and liberal practices among Muslim women on TikTok.

3.1.3 “Promotion, tips, commerce, inspiration”

The third most prominent coded main topic is “Promotion, Tips, Commerce, Inspiration” (62) which includes content such as Hauls, Unboxing, Self-Care routines, Food Vlogs, and DIY projects. This topic generally has an instructional character, mostly aimed at improving various aspects of life, with a significant portion reflecting a commercialized or consumerist content, while another part focuses on wellbeing. Analogous to the “Beauty, Style, and Fashion” topic, this category also highlights a supply-and-demand dynamic among Muslim women, where content creators provide valuable information and knowledge to an audience that actively consumes it. The commercialized aspect further illuminates the market logic present, similar to the dynamics observed in beauty-related content. Given that many of these content creators attract over 100,000 views per video on average, it is clear that they are influential figures within their online community (see Appendix Table 1). Several videos within this topic garnered hundreds of thousands of views. This viewership not only underscores the relevance of this content but also shows that these creators are shaping commerce, self-care, and wellbeing. While the topics mentioned thus far are similar to the mainstream content produced by other creators, they are also influenced by factors like gender and religion. This can be seen in examples such as PT3 introducing the audience to two children’s books from an Islamic bookshop to learn the Arabic alphabet and language, which either contain Islamic examples or are specifically oriented toward understanding and reading the Quran. Similarly, PT26 promotes self-care books that have helped improve her life, two of which are Islamic. Other examples include showcasing restaurants that adhere to Islamic dietary norms, as seen with PT7 and PT19, or discussing beauty products—either reviewing them, like PT12, or warning against them for issues like inauthenticity or health hazards, as PT27 does.

3.1.4 “Religious and theological topics and knowledge”

The topic “Religious and Theological Topics and Knowledge” with 59 videos, is particularly distinctive. Unlike other topics that align our sample closely with mainstream content creators, the topics in this category stand out as unique to Muslims and bring their religious identity to the forefront. Videos in this category show Muslim practices, such as prayer, du’a, umrah, hajj, and deeds that are desirable according to Islamic ethics or related theological discussions. This topic suggests that female Muslim content creators on TikTok are establishing themselves as educators and advisors on religious topics, covering areas such as the permissibility of certain actions, jurisprudence, religious advice, spirituality, and Islamic history. One example is a video by couple PT24, where the husband asks several questions about the permissibility of actions allowed for women in Islam but not for men, while the wife responds:

[…] Husband: “Am I, as a man, allowed to wear gold [touches his wrist] or a nice gold necklace like this”? [runs his hand along his neck, turns to his wife]

Wife: “No, that's something we as women are allowed to do [points to herself], but not you”. [points to her husband and smiles.] […]

Husband: “Okay. And are we, as men, allowed to wear a nice silk shirt? Something really nice”? [mimics a shirt with his hands]

Wife: “No, unfortunately not. Only we [points to herself] women are allowed to. You men are not allowed to do that either”. [makes a dismissive hand gesture]

Husband: “Alright. Are we as men allowed to just skip prayer or fasting, except when we're sick, of course, aside from that?”

Wife: “No, you are not allowed. Only we women are allowed to do that, [points to herself] when we have our period”.

Husband: “Okay. What about Mahr [Arabic for dowry]? Are we also entitled to receive Mahr? Can I demand a Mahr from you? Like a car”? [gestures]

Wife: “No [shakes her head], no, Mahr is something the woman demands from the man during the Islamic marriage, and the man has to fulfill it throughout his life”. [raises finger]

Another example is PT26, who discusses relevant female historical figures and their impact on Islam in several of her videos. Notably, as shown in the examples, women occupy different positions in these videos. On the one side, they are the educators, providing knowledge—for instance, the wife providing answers to her husband’s questions. On the other side, they reference women or womanhood directly, by showcasing significant female figures in Islamic history or highlighting the unique privileges women have in Islam that men do not have. Hereby, they challenge the misconception that men hold all the privileges in Islam. As a function of challenging these misconceptions, they are also addressing gender inequalities from an Islamic point of view. This commitment resonates with existing literature that identifies digital platforms as a “third space” that amplifies voices, especially in relationship to traditionally male-dominated fields such as theology (Pennington, 2018b; Nisa, 2021). Third spaces manifest as environments where Muslim women can explore and discuss Islam and their experiences from a variety of ideological standpoints—whether alternative, subversive, or orthodox (Pennington, 2018b).

Unlike one or two decades ago, when exchanging online was confined to more exclusive digital spaces like newsgroups, blogs, forums or email lists, Muslim women are using TikTok to address a broader digital audience. This is a consequence of the fact that TikTok, like other contemporary social media platforms, has an imminent public. As a result, alternative and lesser-known readings of Islam, even those challenging cultural status-quos and expectations, are amplified in the digital public realm as well and might even diffuse into the offline sphere. PT30 exemplifies this in one of her videos. On screen, she places phrases that “they” tell us “us” (women), relating to the expectation that women should not participate or present themselves in public. She then contrasts these statements with on-screen texts arguing that during the time of the Prophet Muhammad, women worked, participated in politics, and prayed in mosques behind men. While challenging cultural expectations that persist in parts of the diaspora Muslim communities, she draws on Islamic sources to enhance the legitimacy and acceptance of her claim among a religious audience. The specific cultural expectation she challenges concerns the public presence of Muslim women and highlights an attitude among Muslim women that they do not accept the notion that they should be excluded from public life. The video itself, being public, reinforces her message and supports our argument about Muslim women joining public spaces to present and amplify their Islamic perspectives. As such, they are not merely exchanging ideas in secluded circles but are actively participating in shaping Islamic discourses. In doing so, they reinforce their roles as influential public speakers, contributing to Islamic knowledge production, while perhaps more pertinent to women, are crucial to the wider Muslim corpus. This resonates with earlier findings that highlight Muslim women’s contribution to religious discourses online, and thus to an increasing fragmentation and pluralization of religious authority (Bunt, 2018; Nisa, 2021).

An interesting contrasting example is found in the videos by PT31. Some of the content provides religious knowledge, but it is mostly blended with videos featuring male preachers. This approach illustrates how male predominance in religious education can be reproduced as well. Thus, TikTok provides a social platform for a wide range of Muslim thoughts and Muslim positionalities and challenges the notion of Islam as a monolithic and static entity, both for the German mainstream and for Muslims themselves.

3.1.5 “Justice and political advocacy”

“Justice and Political Advocacy” identified in 50 videos, addresses issues such as (gendered) anti-Muslim racism, gender inequality, and experiences related to racism and misogyny. As an intersectionally marginalized group, Muslim women expose and counter experiences of discrimination and defamation unique to them or problematize other forms of social injustice and exclusion against other minorities. This engagement is particularly poignant in Germany, a non-Muslim majority country, where the lives of Muslim women are distinctly racialized and ethnicized (Erel, 2003; Yurdakul and Korteweg, 2021). Many of these women are first-to third-generation migrants, who continually navigate the pervasive challenges of Islamophobia, racism, and gendered discrimination in their everyday lives. In one video, PT27 addresses a common trope directed at veiled Muslim women by first responding to the claim that headscarves do not belong in Germany, countering it by pointing out that Mary, the mother of Jesus, and nuns also wear headscarves. This example highlights the dual context in which justice and political advocacy topics emerge: the politicization of religion, with the headscarf serving as a gendered aspect of this issue, and majority-minority dynamics. PT27’s reference to Mary and nuns illustrates this by using examples that resonate primarily within Christian-majority contexts. PT27 is arguing from the perspective of a minority within a predominantly secular yet historically Christian society, aiming to make the hijab more relatable and acceptable in that context. Sharing anti-Muslim incidents and addressing (gendered) anti-Muslim racism serves two main functions: (a) coping with experiences of discrimination and exclusion on an individual level, as exemplified by PT14, who reenacts in one of her videos how she was treated as a foreigner without German language skills on a bus because she wore a hijab, despite being a German convert; and (b) raising awareness, building support, and fostering solidarity, as seen in PT27’s response to claims that anti-Muslim racism does not kill, where she references the murder of Marwa El-Sherbini in Germany and writes “Say Her Name” at the end of the video as a symbol of political solidarity. Through referencing the “Say Her Name” movement, she ties the Islamophobic murder of Marwa El-Sherbini to the tradition of minority activism, which has utilized this phrasing to highlight and address violence against marginalized individuals, particularly Black women. Political solidarity is a prominent theme in the “Justice and Political Advocacy” videos, and is not only tied to national contexts, with 11 videos focusing on Palestine in response to the atrocities following October 7th, 2024 (see Appendix Table 2).

The lived experiences presented in videos of these content creators highlight the multifaceted and often compounding realities faced by Muslim women, marked not by a singular form of marginalization, but by multiple, overlapping layers of it. This could include religion, gender, race, and migration, as exemplified in the 10 videos classified under “Postmigration.” By advocating for and articulating ideals of justice across racial, ethnic, religious, and gender lines, Muslim women assert significant political roles online (Peterson, 2022). Through displaying their lived experiences, they actively challenge the societal assumptions that depict their lives as apolitical and passive.

3.2 “Hijab and life as a Hijabi”

Recognizing that the hijab and the experience of being a veiled woman play a prominent role in the content produced by Muslim women content creators (39 videos), and that it continues to be one of the central issues shaping the lives of Muslim women, particularly in Western European contexts, we decided to create a separate category for it. This category includes videos that explicitly deal with the hijab as a main theme as well as videos that deal with the lived realities of hijabis. A frequently recurring theme is addressing and defending oneself against stereotyping, defamation, and the suppression of hijabs and hijab-wearing. This may include comedic responses to restrictions on abayas in France or niqabs in general, as seen with PT30, which shows how long skirts or face masks are allowed as long as they do not have a religious tie. PT27 and PT18 react to common stereotypes directed at hijabis in their daily lives. For example, PT27 highlights a common phrase hijabis often hear, that they would look nicer without a hijab, responding with the video’s soundbite, “I’m sorry, I did not order a glass of your opinion.” PT18 addresses several of these stereotypes in a skit, reenacting typical conversations she faces, like questions about how hot it must be under the hijab, or assumptions that she was forced to wear it by her husband or father, all of which she responds to with annoyance. An interesting example is provided by PT9, who reacts to supposedly feminist yet anti-Muslim statements that deny her legitimacy in fighting for women’s rights while wearing a hijab. Statements include: “How can you fight for women’s rights while wearing a headscarf?” “You support the oppression of women by wearing the headscarf.” “You veiled women are destroying everything we have fought for in a 100 years of feminism.” She responds with an educational monolog, which is part of a broader set of videos offering educational content about the hijab. In another video, she explains that she wears the hijab for religious reasons, not to avoid the male gaze, similar to PT30’s educational content on niqabs and burqas. A significant number of videos are also directed toward the creators’ own community, addressing topics such as how to style the hijab, ridiculing the so-called “haram police” who criticize P10 for not wearing the hijab properly, or proudly sharing their decision to start wearing the hijab, as seen with PT19 and PT6. Being relatable to the experiences of fellow hijabis is prevalent in most of the videos mentioned and can be completely free of political context. For example, PT10 humorously enacts the various types of ad-hoc head scarfs that hijabis put on when they suddenly need to open the door for the mail. Interestingly, the content within this category speaks to multiple audiences, highlighting the social pervasiveness of the topic, both for those veiled and those who are not. While the hijab continues to be associated with negative qualities, Muslim women present themselves with the hijab in a self-confident and sometimes even proud way, presenting it as an everyday item. In this sense, they both increase the visibility of the hijab, redefine it, and contribute to its normalization.

3.2.1 “Lived religion”

In line with studies that trace the evolution and transformation of religion in contemporary societies, we distinguish between theology and lived religion—a term coined by scholars such as (Campbell, 2012). In contrast to theological discourses that refer to scriptural evidence, exegesis, religious scholars and authorities, lived religion reflects the individual practice of religion in a particular context. In our case, “Lived Religion” (36 videos) covers aspects of daily Muslim life like religious practices including Hajj, Umrah, and Ramadan. Videos on that topic offer an immersion into the creators’ private and social experiences, resulting in a religiously connoted version of the topic “Personal and Social Life.” Within that category, we find videos like P21 documenting her Umrah pilgrimage, PT4 filming her visit to the mosque, PT7 and PT25 discussing their conversion in relation to their upbringing, their family’s acceptance, or their partner, and PT26 listing and showcasing the “Muslim things” found in her office while giving a musically accompanied tour, including prayer mats, hijabs, the Quran, halal sweets, halal skincare, and Islamic literature.

3.2.2 “Self(re-)presentation”

“Self(re-)presentation” (14 videos) provides an intriguing insight into TikTok’s culture of self-presentation, where creators showcase aspects of their personhood, whether through physical presence or elements of their lives that are uniquely identifiable with them. Typically, these videos feature displays of the self, ranging from simple, uncommented and unlabeled selfie videos to introductions of one’s personhood (name, interests, etc.). A significant number of these videos show the creator with no content other than themselves, styled up, making their physical appearance the only subject of the video. This includes videos from PT2, PT3, PT5, PT6, PT8, and PT15. While Abidin argues that during COVID-19, online fame in the “influencer industry” became less contingent on body image and more on discursive content and performance talent (2020, pp. 83–84), physical visibility remains a tradition in content production that we still observe with some creators. Consequently, the essence of the creator, whether through physical visibility or personal information, often becomes the focal point of their videos, reflecting the inherent (self-)marketing dynamics of the platform, even when the presentation appears trivial. In this logic, the “Self(re-)presentation” topic manifests as the distillation of both the “Personal and Social Life” and “Beauty, Style, and Fashion” topics.

3.2.3 Postmigration

Postmigration refers to a reality fundamentally shaped by migration, where it has become the normal state of being. However, this status quo is contested, as seen in the denial of full and equal social participation to migrants and their descendants. The concept encompasses both the “normality of multiple belongings, mobility, and indefinite positionings” (Yildiz, 2019, p. 386) and the resistance and antagonism directed against this status quo (Foroutan, 2019). These dynamics are showcased in the respective topic (10 videos) in various ways, such as mentioning multiple origins, like PT8 or PT14. Often, done humorously, they display their own struggles with speaking their parents’ language, as seen with PT3, PT9, and PT10, or, conversely, their parents’ struggle with speaking and learning German, like PT3. In a skit, acting as both an interviewer and an interviewee, she struggles to understand the interviewer in her parents’ language, Turkish, and needs her mom’s assistance. She refers to her as a “gurbetçi,” a term used by Turks to describe other Turks living abroad, often implying a loss of language skills or an adaptation to life in a foreign country. Other examples include (migrant) parents’ expectations toward their children, such as PT31, who does not want to marry a person of the same national background, or the challenges of explaining non-German cultural customs to Germans, like PT32. Additionally, there is the issue of dealing with non-German names being constantly mispronounced, to the point where people with these names, like PT29, adapt and introduce themselves using the common mispronunciation—though she also appreciates when people take the time to ask how to pronounce it correctly.

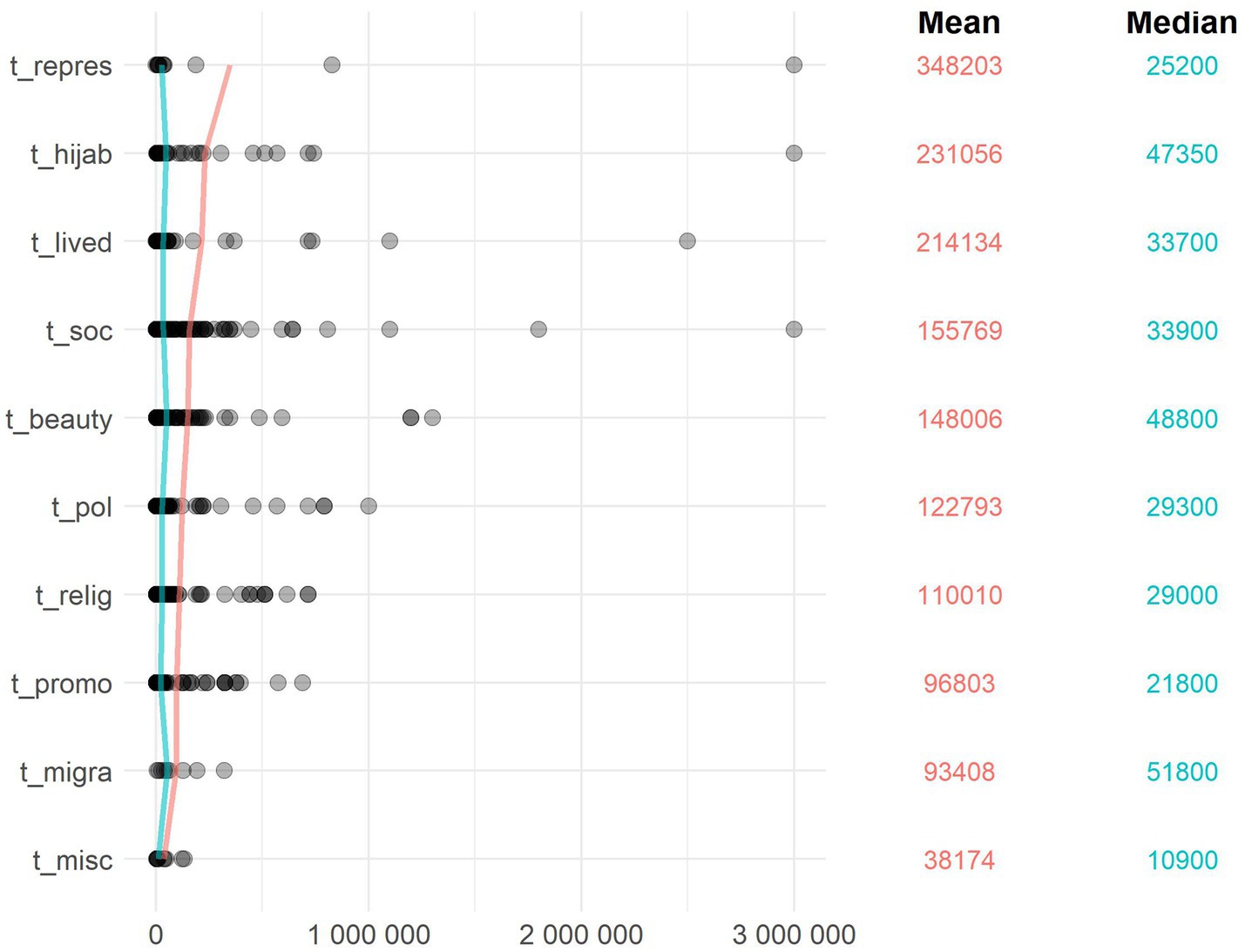

3.2.4 Topics with the most views

Videos on “Beauty, Style, and Fashion” and “Personal and Social Life” generate more views on average than videos on “Religious and Theological Topics and Knowledge” and “Justice and Political Advocacy” (see Figure 2). The high average views for the former two are likely skewed by outliers reaching over one and 3 million views, respectively, indicating how viral these topics can become. However, even the median number of views is lower for the latter two, leading us to speculate whether the inherently entertaining nature of beauty and social or personal content on TikTok may resonate more with the platform’s affordances and audiences than serious topics like theology and political advocacy. However, particularly popular are videos that blend religion with social and private life, which is shown by the topics “Lived Religion” and “Hijab and Life as a Hijabi,” which leans more toward entertainment. Such a blend of religiously connoted content presented from a more entertaining perspective is visible in PT18’s video, a humorous take on how close prayer times are to each other in winter. In fast-forward, she rolls out her prayer mat, performs her prayer, and just after packing up her things, the call to prayer sounds again. This content not only provides a unique element that distinguishes Muslim women from other content creators but also illustrates how TikTok serves as a platform for processing and sharing these experiences, often framed in terms of relatability to the shared experiences of Muslims.

Topics such as political advocacy, religious teachings, lived religion, and hijab demonstrate that TikTok is more than just an entertainment platform; it is a space where personal, cultural, and political narratives blend, interact, and become public.

This use of TikTok transcends information sharing; it fosters community building among like-minded individuals. Given TikTok’s public nature, this is noteworthy. Muslim women on TikTok engage a specific audience by creating content that speaks to the intersectional experiences of Muslim women, or Muslims in general. TikTok’s algorithm structures this engagement, as seen on its ForYouPage. There, the algorithm curates content based on viewers’ interests, ensuring that each piece reaches an audience likely to find it relevant (Boeker and Urman, 2022). Through this feature, TikTok creates specific audiences by matching content with consumers. It is mediated by the relatability of content and shaped by TikTok’s algorithms. This also allows content to spread and go viral, reaching a wider audience if it resonates with other people or the algorithm promotes it as relevant or trending. Communication on this platform is neither entirely public nor strictly private. While Muslim women engage a typical audience, their reach is public, which differs from their previous online presence as exclusive to specific communities described in previous literature (Piela, 2010b, 2012; Pennington, 2018b; Nisa, 2021). This marks a new mode of sociality for marginalized groups using TikTok and the like.

3.3 TikTok’s affordances: video formats

To further our understanding of TikTok’s technical affordances, it is essential to investigate the video formats employed by creators. TikTok videos, like those on other social media platforms, are not only defined by their thematic content but also by how they are presented. Given the technical capabilities of TikTok, videos on this platform are shaped by the techniques available to content creators. As shown in Table 2, we can identify eight prominent video formats, which represent the technical features of TikTok the content creators in our sample use. Music is by far the most dominant video format (186 videos), referring to the ability to add music through the “sounds” feature, which allows creators to incorporate a specific audio file or use audio from another video. This video format co-occurs the most across all topics (see Figure 3), thus it is worth inspecting its role more intensely. The dominance of music may indicate two main functions: first, the artistic role of TikTok videos in enhancing or conveying the content and theme of a video. For example, one video uses a remix of Sam Smith and Kim Petras’ song “Unholy,” while PT2 poses for the camera in slow motion, attempting to convey seductiveness. Another video shows PT11 in a natural scenery with a friend, discussing the importance of not rushing in life and emphasizing simple activities like reading a book or taking strolls in nature. To complement the tranquil setting and message of this video, the creator uses an instrumental song called “Snowfall” by øneheart x reidenshi. Music may also interact with other elements of the video, such as content type. In one video, PT8 introduces her interests, hobbies, and preferences by creating a slideshow of different pictures that showcase these interests. With each beat of the drum in the song “Run Boy Run” by Woodkid, the frame changes, creating a synergy between the song and the visuals. While this function seems general for TikTok users, it also occurs in a hybridized form for the Muslim case. In several instances, content creators use nasheed—Islamic songs and hymns—to emphasize religious content and enhance the overall religious atmosphere of the video. Upon examining the three songs mentioned, the nasheeds as well, it becomes clear that these songs are frequently and popularly used on TikTok to convey similar messages, emotional settings, or content types. Hence, as a second function, the use of music serves as both an inspiration to lend ideas from existing trends and a way to loop one’s content back into existing trends, increasing its visibility by associating it with trends that people frequently use or consume. This again highlights the marketability practices embedded in TikTok’s inherent logic.

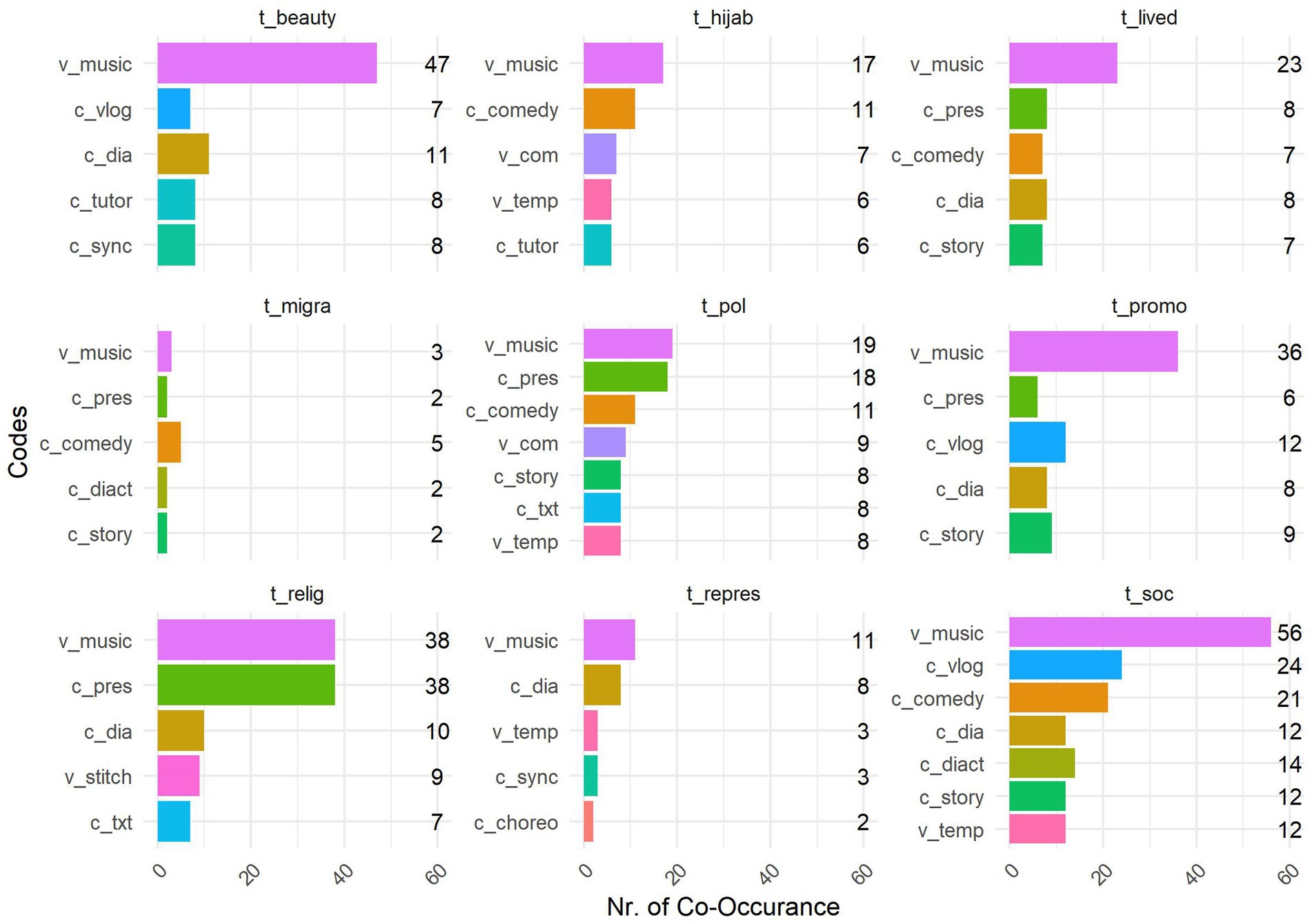

Figure 3. Co-occurrences of main topics with video formats and content types see Appendix Table 3 for label descriptions.

The video format “Audio Templates” (32) showcases somewhat similar functionalities. Audio templates are sounds that, through their inherent dialogs or content, determine what the actor will do, given how they are commonly used or (re-)interpreted. PT4 demonstrates a typical application: she uses an extract from the movie “The Basketball Diaries” in which Leonardo DiCaprio describes how he gradually developed a drug addiction. This sound serves as an instruction to create your own rendition of how one developed a passion, addiction, or something similar. In this case, the creator describes, step by step, transitioning away from listening to music. The audio plays while the text runs simultaneously, allowing her to reinterpret the content. Similarly, audio templates enable artistic interpretations and references to existing trends, much like music does. TikTok’s affordances can be utilized for more interactive video formats, particularly through “Reply (Comment)” (26) and “Stitches” (13). Both features allow interaction with other users’ content: “Reply (Comment)” enables the use of viewer comments as a visual element in videos, fostering interaction with the viewership, while “Stitches” allows for combining and sequencing another user’s content with your own videos, thereby creating interactions with other creators and possibly their audiences. Interactions can take different forms, as can comments from a creator’s viewers. While the “Reply (Comment)” functionality primarily fosters interactions with the audience, its specific use is shaped by the content of the comment itself. Comments can be positive and supportive, such as a viewer complimenting PT14, prompting her to thank the viewer for the kind words. They can be inquisitive, like a viewer asking PT9 why she wears the hijab, giving her an opportunity to explain her reason. These inquiries can come from within the Muslim community, such as a viewer asking PT23 a question related to Ramadan and fasting, to which she provides an answer based on Islamic jurisprudence. Replying to these comments can also create continuity and follow-ups with followers, such as PT3 being asked how she stays serious in her funny skits with her mother, leading to another video showing behind-the-scenes footage where they actually cannot stay serious. Similarly, PT12 follows up on a story that happened in a fast-food chain, elaborating on what viewers did not understand in the previous video. Comments can also be inherently negative. For example, PT9 responds to a comment delegitimizing activism for women’s rights because she wears the hijab: “[…] Unfortunately, I still do not see how wearing a headscarf is compatible with feminism.” Another example is a comment claiming that PT7’s conversion was disingenuous, suggesting it was solely for her Muslim partner, and accusing her of having no prior knowledge of her previous religion, Christianity. In response, PT7 dissects this by sharing her upbringing in the Christian faith and clearly stating that her conversion was well-informed. While positive examples, such as inquisitive comments with educational replies or follow-ups, strengthen community building both within and outside the Islamic faith, the response to negative comments in our sample also highlights that the public visibility of Muslim women online can attract hate. However, many creators do not shy away from this hate or from the public space altogether; instead, they confront it directly and publicly. They confidently claim their space online and defend their presence, rather than resorting to seclusion.

“Image Blending” (13) and “Green Screening” (10) are techniques for including, using, or interacting with visual elements in one’s video. The former enables the integration of visual elements, such as inserting pictures or small video clips, while the latter allows the user to map themselves into a picture or video, directly referencing what they wish to react or respond to. “Filters” (5) can be applied as face filters that modify one’s appearance, for instance, to create caricatures, or as filters that enable other functionalities, such as games that can be controlled with facial motions.

3.4 Overlaps

The aforementioned examples show that the videos analyzed do not merely represent singular topics or formats but are defined by the interplay of different elements. Hence, to elicit patterns of content typically found amongs Muslim female content creators in Germany and what they tell us about the functionalities of TikTok for Muslim women in Germany as an intersectionally marginalized group, we need to aggregate the findings at the intersection of main topics, video formats, and content types. Overall, we recognize three overlaps:

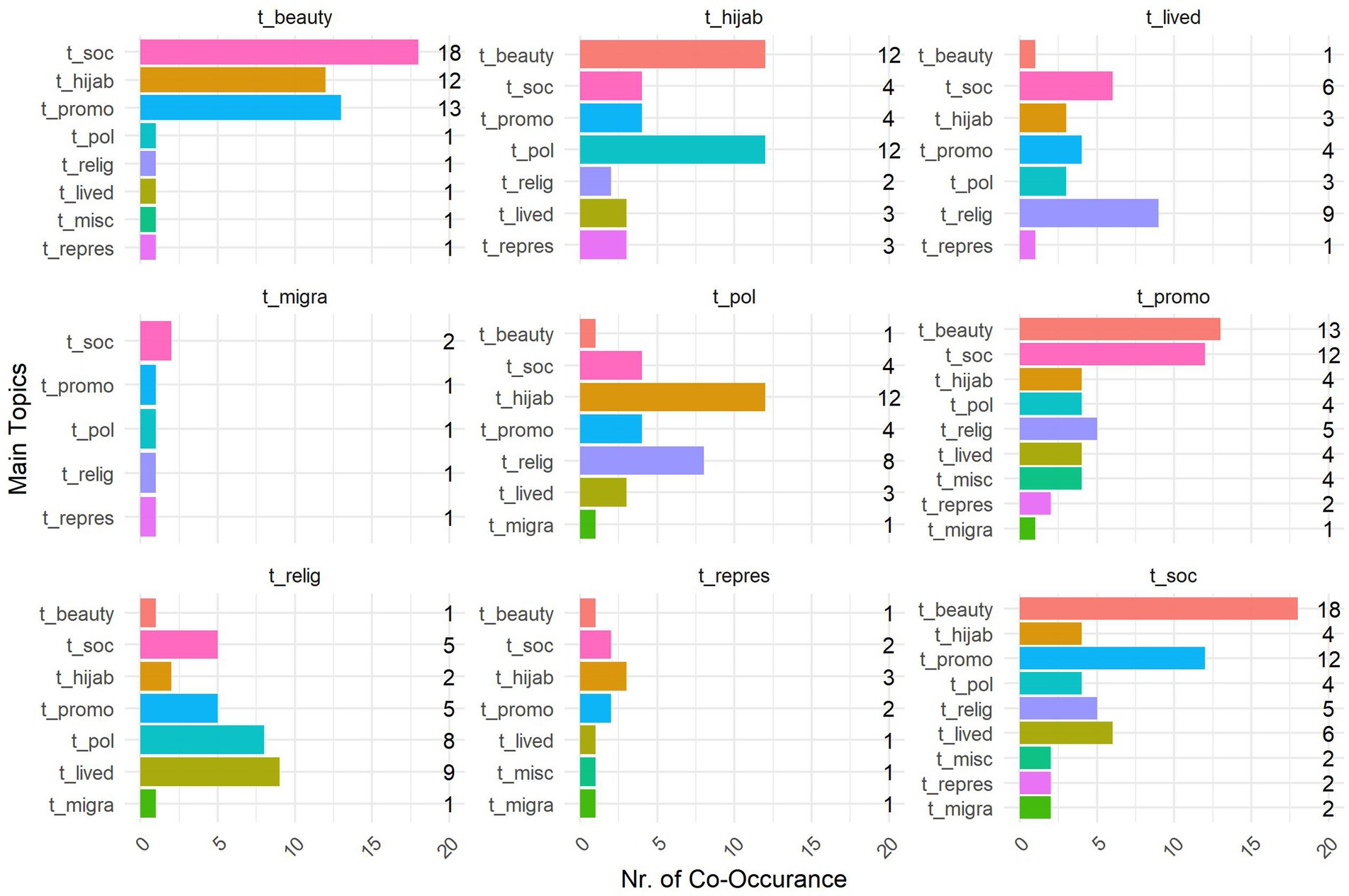

4 Vlogging for aesthetic and influence

As shown in Figure 4, three frequently co-occurring topics—"Beauty, Style, and Fashion,” “Personal and Social Life,” and “Promotion, Tips, Commerce, Inspiration”—form a meta-topic related to the consumer culture prevalent on TikTok, often driven by trends and personal branding. Notably, the first two topics correlate with higher average views in our sample, suggesting their alignment with what is popular on TikTok generally. Content types such as Vlogs (c_vlog), which immerse the viewer in the experiences of the creator, slideshows (c_dia) of pictures, comedic videos (c_comedy), lip-syncing songs (c_sync), or reenacting dialogs (c_diact), strongly correspond with these topics (see Figure 3). Particularly, vlogs and slideshows effectively showcase visual elements, which aligns well with the intent of these topics to display something. Both content types facilitate this purpose. All the mentioned content types have a visually engaging or entertaining aspect, matching well with the overall nature of the topics.

Figure 4. Co-occurrences between main topics; see Appendix Table 3 for label descriptions.

5 Political and religious advocacy

Two frequently co-occurring topics—"Religious and Theological Topics and Knowledge” and “Social Justice and Political Advocacy”—form what could be described as an advocacy meta-topic. As previously argued, political and religious subjects tend to be of a more serious nature. Therefore, presentations (c_pres) are frequently used as a content type and are the most commonly coded for these two topics. This content type is particularly suited for addressing complex issues and providing arguments, making it a key tool for educating and engaging audiences on serious topics. Some content creators strive to be more innovative and engaging in their approach, such as the previously mentioned video by PT24, where one partner asks the other questions about Islamic rulings. The response is delivered in a more upbeat and engaging manner, aiming to make Islamic education and information less dry and appear less stern. Overall, these overlaps indicate a content pattern that is more information-based and serious in nature, likely facilitated by content forms, such as presentations, that are well-suited for transmitting detailed information and arguments.

6 Playful activism and fashionable religion

The co-occurrence of topics, video formats, and content types reveals overlaps that transcend the previously mentioned dichotomy of serious advocacy versus entertaining lifestyle content. We observe topics that frequently intersect with both lifestyle and advocacy themes, such as “Hijab and Life as a Hijabi” and “Lived Religion.” The presence of both aspects in these topics is particularly intriguing. “Lived Religion,” for example, is inherently a hybrid, blending religious themes with a more everyday, life-world perspective. This topic melds social and private content with religious elements, which, as noted earlier, has proven to be successful in terms of viewership.

“Hijab and Life as a Hijabi” is especially striking in its topical co-occurrence, resonating strongly with both “Beauty, Style, and Fashion” and “Social Justice and Political Advocacy.” The pairing of these three topics highlights the politicization of the hijab and the experiences of hijabi women. It showcases their encounters with discrimination and marginalization, while also presenting the hijab as an object of beauty, beautification, and modest fashion, tying it to the fashion market and industry (Karakavak and Özbölük, 2022; Islam, 2023).

Contrasts are visible not only in how topics are paired but also in the varying content types associated with these topics. Both “Lived Religion” and “Hijab and Life as a Hijabi” are connected with comedic content types (c_comedy). However, “Lived Religion” also frequently uses presentation formats, while “Hijab and Life as a Hijabi” also engages with the audience of Muslim women through tutorials (c_tutor). This contrast between entertaining, informative, and instructional content highlights how these topics are approached both seriously and in an amusing manner by Muslim women.

Similarly, “Social Justice and Political Advocacy” also co-occurs frequently with comedic content types. This is notable, as it demonstrates that serious subjects, such as racism, anti-Muslim racism and misogyny, are not only explored intellectually but also humorously. This approach provides a coping and defense mechanism, allowing for engagement with these weighty societal issues through humor, satire, and comedy, effectively breaking the seriousness of these topics (Wills and Fecteau, 2016). A very fitting example is a video by the couple PT25, in which they reply to a comment, “Reply (Comment),” that derogatorily called the wife’s hijab a carpet. Satirically, the woman wears a carpet on her head, laughs and dances while telling her husband that this is the new style invented by this user. Eventually, the husband then creates an insulting pun based on the username of that comment.

7 Discussion

Our findings show that Muslim female content creators produce a variety of content ranging from topics related to their social and personal lives, beauty, style and fashion, product promotion, commerce, tips and inspiration, religious and theological content and knowledge, to social justice and political advocacy, lived religion and self(re-)presentation. While TikTok’s technical features have a specific and intended purpose, they are imbued with meaning by Muslim women who creatively use them to fit their needs and experiences. By combining certain video formats with topics relevant to them, they create actual functions (or functionalities) for these video formats, which might be political advocacy, marketing or (religious) education. While TikTok offers content creators new ways of (self-)representation and expression, our analysis suggests that the particular choice of video format and content type depends very much on the nature of the content itself, the logics and technical affordances of the media platform, and current trends. In the pursuit of virality, content creators are increasingly required to produce novel, unique, and engaging content that is affective and relatable to a broad audience. This could change the way Muslim women represent and express themselves on TikTok and even determine their choice of content.

While a significant portion of the videos relate to religion in one way or another, most of the data analyzed covers social and personal life issues and beauty. As such, Muslim women’s online behavior follows general TikTok usage patterns, revealing a primacy of the secular and mundane.

One issue that stands out and might be considered exclusive to Muslim women is the hijab, highlighting the intersectional life experiences of Muslim women. While problematizing the stereotyping of the hijab and consequently of hijabi women in mainstream discourses, Muslim women self-consciously invoke the multiple meanings and experiences of the hijab. They often refer to the hijab in a humorous or self-ironic way, share reflections on the issue of the hijab, or present the hijab as a (marketable) fashion item. In some cases, internal Muslim discourses on the hijab and the regulation of women’s bodies and behaviors are challenged or rejected. In this sense, Muslim women use TikTok as a third space that allows for non-hegemonic interpretations of the hijab and contributes to the normalization of the hijab within non-Muslim majority contexts. While the issue itself may not resonate with mainstream discourses on TikTok, it can be disseminated through creative and innovative forms of representation that align with the entertaining nature of the platform. Using music and humor, politically charged and socially ostracized issues can be subverted and made more relatable to a broader audience. However, in line with previous research, our study suggests that Muslim female content creators experience hate and harassment as a result of their increased visibility (Allen, 2015; Chadha et al., 2020). This often manifests itself in derogatory speech that reproduces stereotypical narratives of (veiled) Muslim women and contests their presence online. As indicated in our findings section, Muslim women have developed coping strategies in response to hateful comments and discourses using TikTok’s technical affordances. In this sense, TikTok could both increase the vulnerability of Muslim women and provide them with tools to counter their marginalization and discrimination.