- 1School of Marxism, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

- 2School of Politics and International Relations and Institute for Central Asian Studies, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China

The United States has emerged as a prominent actor in the international fight against transnational terrorism in the Sahel region of Africa since 2002, exerting significant political influence on regional affairs. Under the leadership of the United States, a coalition of Sahel countries has collaboratively established security programs, notably including the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Partnership (TSCTP). However, the U.S. counterterrorism strategy in the Sahel region has not only proven ineffective in containing the deterioration of regional security, but also has exacerbated the vulnerability to coups in recipient countries. The observed deterioration can be attributed to various driving factors, such as deviations in the willingness and ability to involve and the security traffic jam. We contend that the U.S.-Sahel counterterrorism partnership is fundamentally misaligned and plagued by a securitization problem. Firstly, a significant impediment to international cooperation lies in the United States’ pursuit of consolidating its dominant role in Sahel security affairs, which usually overlooks the pragmatic principle of ‘African solutions to African problems’. In the counterterrorism process, there is a misalignment between U.S. national interests and those of Sahel states. Furthermore, the United States’ extensive reliance on military strategies indicates a significant securitization of non-violent civil affairs in certain Sahel states, inadvertently creating an opportunity for genuine terrorist organizations to recruit members. In addition, U.S. interference in the internal affairs of Sahel states heightens the risk of coups, thereby undermining the legitimacy of U.S. leadership in the region. Currently, with both the withdrawal of the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) and France withdrawing their security forces from the Sahel region, there has a significant weakening effect on regional security capabilities. Therefore, it is imperative for the international community to collaborate with African nations and adopt more proactive measures to safeguard regional security and maintain order.

1 Introduction

Following the 9/11 terrorist atrocities, the Global War on Terror (GWOT) escalated the prioritization of counterterrorism within the United States’ National Security Strategy. The U.S. has rendered security assistance across the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia, thereby underpinning local counterterrorism efforts. In particular, due to its challenging regional dynamics and the presence of active terrorist entities, the Sahel region of Africa has served as emerged as a priority area for the United States (The White House, 2011). Based on it, the United States has established a suite of counterterrorism programs across the Sahel region, aimed at curtailing terrorist activities and bolstering security capacity within African nations, notable among these is the TSCTP. Yet, despite these efforts, U.S.-led counterterrorism operations have often fallen short in the local context, inadvertently precipitating a cascade of attendant issues: Firstly, the number of terrorist entities in the Sahel region has increased rather than decreased. The main active terrorist groups currently in the Sahel include Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Boko Haram, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), and Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) and some else (Wang and Li, 2022). These terrorist organizations are not only expansive in number but also maintain affiliations with international terrorist networks.

Secondly, terrorist attacks have occurred frequently, resulting in numerous casualties. Between 2007 and 2021, the number of terrorism-related deaths in the Sahel increased by over 1,000% (Louis, 2023). Additionally, the Sahel accounted for 43% of the global terrorism-related deaths in 2022 (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2023), making it considered a ‘new front in the global war against terrorism’ (Zoubir, 2009).

Thirdly, terrorism is intertwined with other traditional and non-traditional security issues. Which are complex and difficult for security forces to deal with effectively. Overall, the Sahel region faces a multidimensional and worsening crisis at the same time, with transnational organized crime, terrorism and traditional military security issues intertwined. On the one hand, terrorist organizations such as the Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) are deeply involved in organized criminal activities such as human trafficking, cigarette smuggling, kidnapping, and drug trafficking, in order to obtain operating funds to establish a solid foothold in the Sahel region (Kfir, 2018). On the other hand, due to the lack of government supervise, Africa’s prison system is gradually becoming a place for radical ideas and an important platform for terrorist groups to recruit. At the same time, the government’s border security control capacity is insufficient, and domestic coups and civil wars are frequent. These factors have led terrorist groups have the opportunities to set up training camps within Sahel countries to enhance their terrorist attack capabilities.

This article is divided into five parts. The first part examines the core question of why the U.S. counterterrorism operations has failed to achieve its stated goals by reviewing the current changes in the terrorist situation in the Sahel. The second part describes the main processes and basic arrangements for the United States to counter terrorism in the Sahel region, focusing on the composition of the TSCTP, a core regional counterterrorism project. The third part further elaborates on the reality of the failure of U.S. counterterrorism operations through examples of U.S. counterterrorism cooperation in Mali and Nigeria. The fourth part analyzes the reasons for the failure of the U.S. counterterrorism strategy from the perspectives of relationship dislocation and securitization. The final part of the article once again clarifies the core point of this article, that is, the United States and Africa’s neglect of the realistic principle of ‘African Solutions to African Problems (ASAP)’ in the context of divergent national interests and the excessive use of military strategies have led to the serious securitization of non-violent civilian affairs in some Sahel countries, inadvertently providing real terrorist organizations with an opportunity to recruit members.

2 U.S. counterterrorism programs and governance strategies in the Sahel region

Since 2002, the United States has conducted extensive counterterrorism operations in the Sahel region. In the process, the United States has built a project system with the TSCTP as the core to promote bilateral counterterrorism cooperation and consolidate its national interests.

2.1 The historical transformation of the United States in counterterrorism in the Sahel region

The United States launched its counterterrorism operations in the Sahel region relatively early. From the perspective of time, the United States’ counterterrorism operation in the Sahel region can be divided into three stages: the initial stage from 2002 to 2008, the development stage from 2008 to 2013, and the mature stage from 2013 to the present.

After the 9/11 incident, the United States began to promote preventive strikes against terrorist organizations around the world, viewing counterterrorism assistance as ‘the first line of defense for the protection of our homeland as well as U.S’ (Pope, 2005). Against this backdrop, the U.S. government established the Pan Sahel Initiative (PSI) in 2002 as the main counterterrorism project in the Sahel region. In the initiative, the military path is the core way in which the United States provides assistance. The top priority for U.S. counterterrorism assistance to four West African countries is to build six company-sized counterterrorism quick reaction force, half of which are destined for Mali (Shurkin et al., 2017).

In 2008, United State Africa Command (AFRICOM) was officially put into operation, unified management and coordination of security projects in Africa, and became the regional executor of U.S. security affairs in Africa. Previously, U.S. security operations in Africa were under the jurisdiction of three separate U.S. military commands. Of these, North and West Africa are commanded by the European Command (EUCOM), East Africa and Northeast are commanded by the Central Command (CENTCOM), and Madagascar is commanded by the Pacific Command (PACOM) (Harmon, 2015). The establishment of AFRICOM has enabled the United States to carry out unified management and centralized coordination of various security affairs, including counterterrorism, and to a certain extent, has promoted the systematic development of its own security governance in Africa.

In 2013, the Obama administration formally introduced the Security Sector Assistance (SSA) policy, which integrates the security cooperation programs led by the Department of Defense and security assistance managed by the State Department, and the United States has further developed its presence in counterterrorism operations. Previously, the U.S. Congress authorized the Department of Defense to carry out security cooperation programs under Section 10 of the United States Code and the annual National Defense Authorization Act, as well as Section 22 of the United States Code, the Foreign Assistance of Act of 1961, and the Arms Export Control Act of 1976 authorizes the State Department to establish a security assistance system (Epstein and Rosen, 2018). To a certain extent, this state of independence of security assistance and security cooperation has also led to problems such as overlapping tasks and misuse of funds between them. Although the implementation of the new security sector assistance program has not improved the United States’ system of such assistance, it has undoubtedly improved the effectiveness of counterterrorism to a certain extent. At this point, the US counterterrorism operations in Africa have entered a mature stage. At present, with the withdrawal of troops from Niger, the United States has lost its counterterrorism hub in West Africa, and its counterterrorism deployment in the Sahel region is once again facing new adjustment pressure.

2.2 Major U.S. counterterrorism projects in the Sahel region

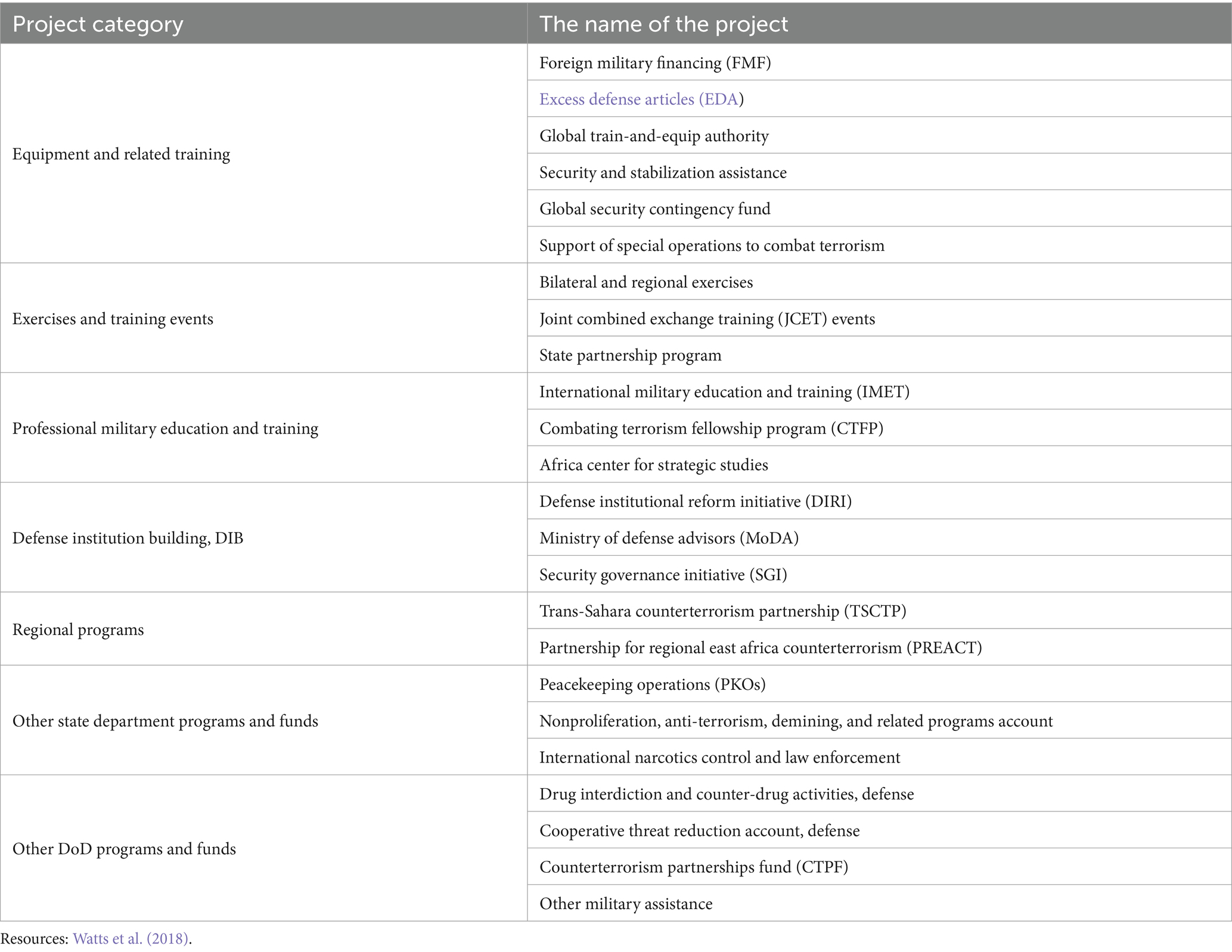

U.S. security sector assistance in Africa covers a wide range of areas, including counterterrorism, counternarcotics, and border capacity-building, as detailed in Table 1. These security sector assistance projects can be divided into general and regional projects in terms of type. These two types of projects have different objectives. Among them, the objectives of the regional projects are clear, and the target of assistance is also clearer. General projects such as equipment, exercises and training cover a wider range of targets and objectives, but all provide support to African countries in their counterterrorism capacity-building to varying degrees. U.S. regional projects in Africa include the Partnership for Regional East Africa Counterterrorism (PREACT) and the TSCTP. The former is based in the Horn of Africa and the later focus on the Maghreb-Sahel region. Both explicitly point to the issue of terrorism.

The core objectives of the general program are counterterrorism and the stability of partner countries. In fact, the two objectives are mutually reinforcing. In other words, the need for the United States to cooperate with African partners in areas such as intelligence in counterterrorism requires the United States to provide these countries with other forms of security sector assistance to achieve long-term stability within partner countries (Watts, 2015). At the same time, stability of partner countries can provide a more favorable external environment for counterterrorism.

In terms of importance, the TSCTP is a core project of the United States in the Sahel. The development of the project went through three phases. The first phase is the Pan-Sahel Initiative. In 2002, the United States established the Pan-Sahel Initiative to support the four Sahel countries in maintaining border security and combating extremist forces. To this end, the U.S. government has invested a total of $7.75 million to assist the four countries in equipping and training six company-sized quick reaction forces (Boudali, 2007). The second phase is the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Initiative (TSCTI). In 2005, the U.S. Department of State led the establishment of the TSCTI on Counterterrorism as a follow-up security project to the Pan-Sahel Initiative. At the same time, the U.S. government has expanded the project’s geographic activity to the Maghreb region in order to achieve interregional interlinkages in security matters. Specifically, on the basis of the Pan-Sahel Initiative, the TSCTI has included three countries in the Maghreb region, Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, and two countries in the Sahel region, Nigeria and Senegal, as African partner countries. Since then, the United States has also placed the project under the management of the newly formed Africa Command to promote the improvement of the project’s chain of command. The third phase is the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Partnership phase. In 2010, the U.S. government filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Accountability Office (GAO), adjusted the project and renamed it the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Partnership. Since then, the United States has also taken continuous steps to strengthen the project. For example, the U.S. government decided to increase project input at the Eight Annual Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership Conference (United States Department of State, 2013). At the same time, the U.S. Congress passed the Trans-Saharan Counterterrorism Partnership Act, which provides domestic legal guarantees for the operation of the project (United States Congress, 2021).

The TSCTP is a relatively complex organization. The project is led by the Department of State’s Bureau of African Affairs and coordinated by other departments, including the Department of Defense, the U.S. Agency for International Development and the State Department. At the executive level, the U.S. Ambassador to partner nation directs and coordinates the partnership through a ‘Country Teams’ of relevant agencies (Warner, 2014); AFRICOM has served as the main manager and executor. In addition, the United States has deployed two joint task forces in the region to carry out military missions. Among them, the Joint Special Operations Task Force - Juniper Shield (JSOTF-JS) was established by European Command in 2006 and transferred to the Special Operations Command Africa (SOCAFRICA) under Africa Command in 2008. It serves as the focal point for Special Operations Command Africa’s trans-Saharan operations, with military training, equipment distribution, and exercise coordination (Global Security, 2018). The Joint Task Force - Aztec Silence (JTFAS) was established in 2003 as a special task force established by the European Command to coordinate counterterrorism operations with countries in North and West Africa. The mission of the unit is to use the equipment of the Sixth Fleet for surveillance operations, to gather intelligence for US intelligence agencies, and to strengthen intelligence cooperation with relevant African countries.

The TSCTP consists mainly of two main areas: military and civilian. In the area of military operations, the project mainly provides military training, financial assistance and arms sales to indigenous African countries (Boudali, 2007; Bray, 2011). Among them, Operation Enduring Freedom - Trans Sahel (OEF-TS) is the main military support project, responsible for countering terrorism, arms proliferation, drug trafficking, and other related activities (Berschinki, 2007; Boudali, 2007). The project was led by the Special Operations Command Europe (SOCEUR) in April 2005, transferred to Africa Command in 2008, and renamed Operation Juniper Shield (OJS) in 2011. In the area of civilian operations, the U.S. government and military primarily implement development assistance and public diplomacy. In development assistance, the United States mainly provides education, medical resources, and vocational training. In public diplomacy, in addition to strengthening radio broadcasting, the U.S. government has established professional Military Information Support Teams and Civil Military Support Elements. It is hoped that this will increase the recognition of the African public with the effectiveness of the United States’ support for Africa, thereby improving the perception of the American national image of the African public (Boudali, 2007).

While the U.S. government has set ‘defense, diplomacy and development’ targets for Security Sector Assistance, including the TSCTP, it has focused on military programs and neglected civilian and diplomatic programs. In the field of military operations, there is a relative lack of direct military intervention, and emphasis is placed on military training and the provision of equipment. According to the Security Assistance Monitor, the United States has spent more than $3.3 billion on security assistance in the Sahel over two decades (CIP Security Assistance Monitor, 2023; Noyes, 2023).

3 U.S. counterterrorism failure in the Sahel

Although the United States has been conducting counterterrorism operations in the Sahel relatively early and has set up many programs to support counterterrorism operations, the effectiveness of American counterterrorism operations has been relatively limited. The United States has not only failed to effectively curb the activities of terrorist organizations in Africa, but has exacerbated the deterioration of the regional security situation.

3.1 Intervention in Mali_ the weakness of capacity-building in responding to terrorism

In 2002, when the United States established the Pan-Sahel Initiative, it regarded Mali as an important partner. In the initiative, the military path is the core way in which the United States provides assistance. The first priority of the United States is to assist the four West African countries in building six company-sized counterterrorism quick reaction forces, three of which are trained in Mali (Shurkin et al., 2017). The United States considers Mali to be a top priority of the Pan-Sahel Initiative because it sees Mali as an important pillar in preventing the spread of al-Qaeda to Africa (Heinrich, 2017). On the one hand, al-Qaeda, the organization responsible for 9/11, tried to contact the Salafist Group for Call and Combat (GSPC) in Africa and attempted to plot an attack on the U.S. Embassy in Bamako, Mali (Smith, 2004); On the other hand, Mali is also at risk of being controlled by terrorist groups as a potential refuge for GSPC. As a result, the U.S. government established the Pan-Sahel Initiative to provide counterterrorism training and equipment to African countries to prevent terrorist groups from establishing bases in the Sakh region (Harmon, 2015).

U.S. counterterrorism assistance played an important role in its early days. Between 2002 and 2006, the U.S. government provided less than US$6 million in security assistance to Mali (Tankel, 2020), but significantly suppressed terrorist attacks in Mali (Global Terrorism Database, 2022). Malian President Amadou Toure and the military’s General Gabriel Poudiougou have also expressed their gratitude to the United States for helping the country address the challenges posed by AQIM (Huddleston, 2009).

However, with the gradual deepening of counterterrorism cooperation between the United States and Mali, more problems have also emerged. Especially during the crisis in Mali, the lack of counterterrorism assistance has a direct impact on the actual performance of the Malian army. In 2012, the Tuareg insurgency analysis, which is part of the Mouvement National pour la Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA), joined forces with terrorists such as Ansar Dine and the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) to carry out insurgency activities (Harmon, 2015). Against this backdrop, the performance of the Malian government’s troops, which are trained by the United States, has been less than satisfactory. Not only have these Malian forces failed to respond effectively to the threat of terrorism and insurgency, but they also clearly lacked the will to fight during the fighting, showing a weak level of professionalism (Shurkin et al., 2017). So that by 2013, allied rebels had even captured two-thirds of northern Mali at one point. The Malian military’s fragile denial capability is a testament to the malignant effects of the over-militarization of U.S. counterterrorism strategies. It was in this context that in 2013 the Malian government turned to France for assistance, directly pushing for direct French intervention in Mali under the framework of Operation Serval. The United States has also declined as Mali’s counterterrorism partner.

At the same time, while Mali maintains a military partnership with the United States, but it has not been effective in reversing Mali’s fragile security situation. The Sahel region has become a ‘a new frontier in the fight against terrorist groups’, and Mali is one of the five countries in the world most affected by terrorist deaths (Donati and Mcbride, 2019; Green, 2023). As a result, Mali has lost confidence in the counterterrorism assistance of Western powers. At present, while withdrawing from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Sahel G5, and forming the Alliance of Sahel States, Mali is also demanding that France and the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) withdraw their troops and announce the end of the military agreement with the United States. The twin facts of the United States’ inability to weaken terrorist forces in Mali and its own forced withdrawal are important evidence of the failure of the United States to combat terrorism in the Sahel region.

3.2 Intervention in Nigeria: symbolic intervention and the growth of Boko Haram

Nigeria is one of the key partners of the United States in the TSCTP, and it is also one of the countries in the Sahel region that faces a serious threat of terrorism. The main terrorist organization active in Nigeria is Boko Haram. Boko Haram emerged in the 1990s and its name means ‘Western education is forbidden’. The establishment and development of Boko Haram is due to the long-standing religious and ethnic contradictions in Nigeria, as well as the imbalance between the economic development of the North and the South. The most prominent of these are the religious contradictions between the Islamic groups in the north and the Christian communities in the south, as well as the ethnic contradictions between the Hausa, Yoruba and other minority groups. In 2009, Boko Haram, which had been frustrated and dormant in previous clashes with government forces, re-energized and provoked riots in Maiduguri (Ning, 2018). The sudden outbreak of the Maiduguri riots and the subsequent execution of Yusuf by the Nigerian police prompted the group, under the leadership of its successor, Abubakar Shekau, to quickly turn to violent terror to achieve its political goals. Since then, Boko Haram has entered a stage of rapid development and has gradually become one of the important sources of security instability in Nigeria and the entire Sahel region.

In the face of the growing threat of terrorism, the Nigerian government has tried to weaken Boko Haram’s viable forces through forceful military intervention. However, Boko Haram has made a comeback due to its strong tactical adaptability and has gradually grown (Brechenmacher, 2019). Nigeria, with its weak counterterrorism capabilities, has turned to more security resources to respond, and the United States-led counterterrorism partnership has had a limited response.

In the following decade, despite the active crackdown on Boko Haram in Nigeria and its neighboring countries, due to the actual conditions conducive to terrorist activities in Africa, the organization continued to develop, and successively attacked the United Nations building in Abuja, causing the Baga Massacre Incident and the Chibok Kidnapping Case, which seriously endangered regional security and became the main terrorist organization in the Sahel region.

In the face of the rise of Boko Haram, the Nigerian government lacks the capacity to respond effectively. While Nigerian government forces have conducted numerous military operations and attempted peace negotiations, they have been lackluster in terms of governance effectiveness. As a result, the Nigerian government turned to the international community for help in mitigating the threat of terrorism in the country and safeguarding its national interests. In this context, the United States, under the framework of the TSCTP, is cooperating with Nigeria on counterterrorism to combat Boko Haram.

However, in fact, the United States has only provided verbal support or symbolic assistance in the face of Nigeria’s Boko Haram problem, and actual crackdown measures are rare. Specifically, this is mainly reflected in the aspects of target setting, intelligence support, and civil practice. In terms of targeting, the U.S. government considers Boko Haram to pose less of a threat to its own interests, so it takes it relatively lightly. The cooperation between the United States and Nigeria on the fight against Boko Haram has been mainly since the Obama administration. During the Obama administration, after experiencing the peak period of high-profile counterterrorism, the United States officially clarified the goals and tasks of counterterrorism, and gradually achieved a comprehensive contraction of the counterterrorism front. In terms of geographical focus, the United States emphasizes the primacy of local counterterrorism (The White House, 2011). In terms of targets, choose to focus on al-Qaeda. In terms of the way to combat it, ‘Countering Violent Extremism’ (CVE) will replace the ‘global war on terror’. At this time, although the United States still regards the Sahel region as one of the important areas for counterterrorism, the perception of the threat of local terrorism is in an inevitable downward trend. At the same time, Boko Haram has shown a willingness to attack Western countries, but its current attacks are mainly aimed at soft targets in the region (Senate Committee on Armed Services, 2016). Although there is also an argument that Boko Haram could have an impact on U.S. national interests (Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence Committee on Homeland Security House of Representatives, 2011). However, the United States has been slow to designate Boko Haram as a foreign terrorist organization, and there has been a lack of response to Nigeria’s security demands. Although since then, the United States, driven by political goals, has included Boko Haram in the list of foreign terrorist organizations in exchange for the development of relations with Nigeria. However, the United States’ attention to Boko Haram has always been at a limited level.

On the intelligence support side, the United States has been lukewarm to Nigeria’s call for intelligence cooperation. While the U.S. has provided military intelligence to the Multinational Joint Task Force to support its strikes against Boko Haram and ISIS West Africa Province (Nyiayaana and Nwankpa, 2022). At the same time, the United States has established a series of staging, cooperative security locations (CSLs) and forward operating lacations (FOL) in countries such as Burkina Faso and Niger. Most of the bases are deeply involved in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operations, as well as special operations missions. However, the United States has been lukewarm in the face of Nigeria’s request for intelligence support. Both France and the United States, while at one point emphasizing their support for the fight against Boko Haram, do not plan to take any direct military action (France 24, 2014).

In civil practice, the United States has also placed greater emphasis on the achievement of its own political goals and neglected to weaken the social and economic basis of terrorist activities. In the TSCTP, the United States has actively promoted advocacy activities through the production of radio dramas and support for the operation of the Arewa 24 Hausa-language media platform (United States Government Accountability Office, 2018). The public diplomacy of the United States, represented by the establishment of radio stations, is more about improving the image of the United States and promoting Western values among the people of the target countries while promoting de-radicalization propaganda. The United States has also attached political conditions such as democratization and good governance” to its security cooperation and security assistance programs, and expanded the goals of the counterterrorism program to enhance ‘youth empowerment, education, media, and good governance’ (Aldrich, 2014). These measures facilitate the influence of the political culture of the follower country, and thus the manipulation of the target’s domestic and foreign policies. As a result, the goal of the de-radicalization propaganda of civil measures in the United States has been severely weakened.

It is precisely because of these factors that Boko Haram has not been severely weakened, but has also forced parts of Nigeria into a state of emergency (Okaoli and Lenshie, 2022) and infiltrated neighboring countries such as Chad, Cameroon, and Niger (Harmon, 2015). The U.S. inability to counter terrorism in countries such as Mali and Niger has made West Africa ‘a weak point in the U.S. initiative to combat terrorism’ (Jones, 2013). Nigeria’s ambassador to the United States has publicly criticized the U.S. government for its inaction on Boko Haram (Schmitt, 2014). In response, Nigeria has chosen to seek assistance from more extraterritorial actors while placing greater emphasis on the role of Africa’s indigenous security mechanisms. Specifically, Nigeria is pushing subregional organizations such as the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to play a more effective role in the fight against Boko Haram (Henneberg and Plank, 2020). On the other hand, Nigeria seeks security cooperation with other extraterritorial intervention actors other than the United States. It has signed military cooperation agreements with France and the United Kingdom, and has established security and defense partnerships (Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence Committee on Homeland Security House of Representatives, 2011).

4 The practical logic of the failure of the US governance strategy in the Sahel

The examples of Mali and Nigeria above illustrate the serious problems with US counterterrorism operations in the Sahel and the failure of governance. It is worth noting that the failure of this governance strategy is not an accidental event, but has a profound practical logic. Specifically, the main reasons for the failure of the US counterterrorism operation mainly include two more prominent problems: relationship dislocation and security.

4.1 Relational dislocation: the internal contradiction of the negative leader

The United States has played a rather dislocated role in its relations with the countries of the Sahel region, so much so that the two sides have presented the real problem of misalignment. This dislocation of the relationship exacerbates the contradictions between them, thus restricting the realization of the governance effect.

Relational dislocation refers to the fact that the state plays the wrong role according to the wrong role positioning in the process of interaction and practice. In the interaction between the United States and countries in the Sahel region, the most realistic need is that African countries play a leading role in the process of regional counterterrorism and lead the formulation of counterterrorism strategies and programs. The United States, for its part, provides necessary technical and equipment support to African countries and assists in perfecting strategies and tactics. This ideal state of relational interaction is reflected in the adherence to the ‘African solution to the African problem’. ASAP emphasizes both ‘who’ to solve African problems and ‘how’ to solve African problems. The former emphasizes the leading role of African countries in regional affairs, African countries have the lead in the prevention, management and resolution of conflicts on the continent (Dersso, 2012), and the ownership and political leadership of external civil and military interventions must lie with African institutions (Kingebiel, 2005). The latter emphasizes the role of traditional practices and rules, such as indigenous programmes. This idea can be traced back to ‘Pan-Africanism’ (Esmenjaud and Franke, 2008). In 1967, Ali Mazrui first raised the need for Africans to assume responsibility for maintaining peace and security on the continent. At the 2012 AU summit, the Chairperson of the AU Commission, Jean Ping, further stated that ‘Indeed the solutions to African problems are found on the continent and nowhere else’ (Joselow, 2022). In fact, only African countries have more willingness to implement non-military and local solutions, and Africans have a greater confidence in the role of local solutions.

Specifically in the area of counterterrorism operations, this means that foreign powers play the role of auxiliaries under the principle of ‘African solutions to African problems’. As mentioned earlier, the countries of the Sahel region are ill-equipped to cope with the gradual deterioration of the regional security situation. Therefore, countries are eager to obtain security assistance from foreign powers in order to improve their security governance capabilities and thus eliminate terrorism. In doing so, the countries of the Sahel region are looking to foreign powers to provide financial, technical and equipping support, as well as to help advance the implementation of politically specific political solutions. This also means that foreign powers will become ‘auxiliators’ or even ‘active auxiliaries’ in regional counterterrorism operations.

However, the opposite is true. In its actual actions, the United States deliberately ignores the ‘African solution to African problems’ and instead seeks to seize the hegemony in regional security affairs. Specifically, the United States has used its aid relationship with Africa to create a de facto unequal position. Unlike France, the United States has not conducted any direct military operations in the Sahel, but has engaged in a series of security cooperation with status actors. However, as the world’s largest power, the United States has abundant security resources. Africa, on the other hand, faces a lack of security resources to counterterrorism. Therefore, the United States has taken advantage of the fact that the countries of the Sahel region are in dire need of security resources to provide security assistance to the latter. In the process of aid, the United States has actually built an unequal aid relationship that benefits its own country by setting a series of conditions for the use of aid. The countries of the Sahel region lack an effective response to such intentions by the United States. At the same time, these countries are worried that the United States will suspend military assistance if it does not meet its expectations, and will eventually be forced to cede control of security affairs.

There are three main reasons why the United States has been able to successfully seize the dominance of counterterrorism affairs: First, the United States has actively used its superior strength to seize the dominant position in order to achieve its strategic goals; Second, the failure of countries in the Sahel region to make effective use of U.S. security assistance has provided an opportunity and an excuse for foreign powers to compete for dominance. Third, the Sahel countries lack effective ways to deal with the competition for dominance among foreign powers.

First, driven by political and security objectives, the United States has actively used its military and resource superiority to compete for dominance in regional counterterrorism affairs. In fact, the United States has long believed that terrorism in the Sahel is less likely to threaten U.S. security interests at home, and it is primarily concerned with its own overseas interests there. On the political front, the United States sees Africa as a major region in strategic competition with China and Russia to consolidate the so-called democracies circle. In 2012, the U.S. government refocused its strategy on Sub-Saharan Africa to:

(1) strengthen democratic institutions; (2) spur economic growth, trade, and investment; (3) advance peace and security; and (4) promote opportunity and development’ (The White House, 2012).

On the economic front, the United States has gradually increased its focus on African oil since 2001 and has a strong tendency to defend its own energy interests. It is precisely under the influence of such factors that the United States has gradually regarded counterterrorism as an important basis for achieving its political goals. However, African countries hope that the United States can truly play an important role in regional counterterrorism affairs. The differences between the United States and the countries of the Sahel region in terms of counterterrorism goals have made the United States hope to maintain its own strategic goals by seizing the lead in counterterrorism affairs. As a result, the United States has pursued hegemonic governance on the ground while viewing the TSCTP and other security assistance programs, no longer as a means to a specific goal, but as an end in itself (Rand and Tankel, 2015).

Second, the security assistance provided by foreign powers to the countries of the Sahel region has not had the desired effect, providing an excuse for foreign powers to seize the dominant position. In Mali, for example, the United States trained several quick reaction forces for Mali before 2013 under the framework of the Pan-Sahel Initiative and provided substantial military assistance. However, in the Mali crisis, the elite forces built up by the United States collapsed in the face of the combined threat of Tuareg rebel groups and jihadist groups, and did not work as expected (Shurkin et al., 2017). In addition, the establishment of the Sahel G5 with the support of foreign powers was once seen as an important solution to African problems (Campbell, 2017), but it did not have an effective impact on the regional security situation (Sandnes, 2023). These facts show that security organizations and States in the Sahel region have not been able to make favorable progress in the area of counterterrorism, despite external assistance. This move undoubtedly provides an excuse and basis for major powers outside the region to compete for dominance in security affairs.

Third, countries in the Sahel region lack effective ways to deal with foreign powers vying for dominance in security affairs. As a matter of fact, under the influence of their own interests and relying on their national strength, major powers outside the region have seized the lead in regional security affairs through their aid relations. African countries, on the other hand, are in a dilemma of having the will but not the ability. Due to the disadvantage of their own strength and status, the countries of the Sahel region can only use the measures of interest exchange to seek the leading position on some specific issues, and cannot use coercive measures to force the major powers outside the region to truly accept the principle of ‘African solutions to African problems’. In the process of swapping interests, the Sahel region not only lacks the resources to induce the United States to give up its struggle for dominance, but also forms a heavy dependence on the United States and the United States due to the needs of its own national governance. The inadequacy of actors in the Sahel provides favorable conditions for the United States to compete for dominance.

It is precisely because the United States has seized the lead in security affairs in the Sahel region that the United States and the countries of the Sahel region have a serious dislocation in their counterterrorism interactions. As a result of this dislocation of relations, the United States, which emphasizes its own strategic interests, instead dominates the main process and implementation plan of counterterrorism affairs. Boulton and Carter (2014) argue that the United States provide security assistance primarily considerate its own interests rather than those of its allies. In fact, in the process of counterterrorism, the United States has also built different levels of assistance relations with different countries mainly on the basis of political interests rather than actual threats. As a result, the United States often selectively conducts counterterrorism operations and ignores the opinions of regional countries in the implementation of its policies. In contrast, Sahel countries, which are closely related to regional security, find it difficult to effectively respond to regional terrorist threats based on local knowledge and experience. An important manifestation of this contradiction is that in 2013, when the Nigerian government and Boko Haram were engaged in peace talks, the United States, which had been slow to act, put Abubakar Shekau and others on the wanted list (Ning, 2018).

4.2 Securitization: over-reliance on military tactics

In addition to the misalignment, another important reason for the failure of the United States to counter terrorism in the Sahel is its over-reliance on military strategy. Specifically, in the TSCTP, the U.S. government has provided some development and diplomatic assistance, but the war mentality has maintained the dominance of military means (Olsen, 2011). However, military means have been inadequate in dealing with the fundamental economic and social problems that breed terrorism (Savell, 2021). While the U.S. government has aware of this problem, the unequal interests of military structures and departments not only hinder the use of inclusive strategies, but also lead to a militarization of diplomacy and development assistance (Ploch, 2011; Ucko, 2019).

Specifically, the United States has overemphasized military means in counterterrorism in the Sahel region, and relatively neglected the use of civilian means. African countries have pointed out that while counterterrorism resources should be invested in 80 percent development and 20 percent defense (Wong, 2007). However, the reality is quite the opposite. And the U.S. program in Mali as a whole focuses on security inputs such as counterterrorism training (Thurston, 2017). For example, in the process of promoting security cooperation, the United States has shown a tendency to over-militarize military deployment, fund allocation, and mission implementation. In terms of military deployment, the U.S. government has deployed a large number of military facilities in Africa through the Lily-Pad Strategy and the Light Footprint strategy. In terms of funding allocation, U.S. funding in the Sahel is mainly focused on military operations. Between 2005 and 2008, for example, Mali received about $37 million in counterterrorism funding from the United States, but more than half of that was spent on military programs (Pincus, 2013).

In terms of mission areas, the United States has promoted the militarization of civilian assistance while attaching importance to military missions. In the TSCTP, the U.S. government has provided some development and diplomatic assistance, but a war mindset has maintained the dominance of military means (Olsen, 2011). While the U.S. government is aware of this problem, the inequality of military structures and inter-agency interests not only hinders the use of inclusive strategies, but also leads to a militarized tendency in diplomacy and development assistance (Ploch, 2011; Wade, 2016; Ucko, 2019). For example, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has provided assistance and training to African police forces, essentially transforming them into a quasi-security agency (Hills, 2006). As for the excessive assumption of civilian liability by the US military, it has also aroused the dissatisfaction of senior US military officials. U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates has made it clear that:

‘It is important that the military is and is clearly seen to be in a supporting role (regarding foreign policy) to civilian agencies…The Foreign Service is not the Foreign Legion, and the United States military should never be mistaken for the Peace Corps with guns’ (Turasz, 2014).

It is precisely as a result of this strategy that the US counterterrorism policy in Africa has achieved many tactical rather than strategic successes (Warner et al., 2022).

The United States overemphasis on the use of military tactics in counterterrorism operations has not only failed to effectively combat terrorism, but has instead provided favorable conditions for the spread of terrorism. Although the militarization of U.S. counterterrorism assistance can deter terrorist activities in the short term, it has a strong adverse impact in the long run. This adverse effect is mainly reflected in the following two aspects:

On the one hand, military means cannot eradicate the economic and social soil that breeds terrorism, nor can it eradicate terrorism once and for all. In the process of governance, the United States attaches too much importance to the use of military means and relatively neglects civilian means. This has made it difficult to end the conflict and has affected the stability of the Malian regime. At the same time, overly militarized governance undermines the very foundations of peace, national sovereignty and national status in Mali. In fact, across Africa, the countries most in need of security assistance often fail to benefit from U.S. assistance.

On the other hand, the state’s overemphasis on military means in the governance of terrorism will further exacerbate the discontent of terrorist organizations and trigger retaliatory attacks (Noyes, 2023). At present, most terrorist organizations are professionalized and networked. As a result of this change, terrorist organizations rely more on operational leaders than on core command in their operations. Therefore, the government’s crackdown on the leadership of terrorist organizations will not only fail to effectively weaken terrorist organizations, but will provoke adversaries. Terrorist groups will retaliate in response to the government’s armed strikes. At the same time, the US military strategy would provide a basis for ‘legitimizing’ terrorist attacks. Terrorist organizations regard foreign powers represented by France and the United States as ‘heretics’ and their own governments that seek the intervention of foreign powers as ‘apostates’. In the face of U.S. militarization tactics, terrorist groups will portray themselves as ‘defenders of the faith’ against ‘heretics’ and ‘apostates’. This can not only give ‘legitimacy’ to the terrorism groups’ attacks, but also win the support and trust of ordinary people and promote the growth of the organization.

5 Conclusion

As an significant region for global terrorism, the Sahel region has long attracted the attention of international actors. Among them, the United States began to be involved in counterterrorism affairs as early as 2002 and has gone through multiple stages of development. In the process, the United States has established a series of security programs to provide counterterrorism support and assistance to countries in the Sahel region. And the TSCTP is the most representative counterterrorism project of America. It is worth noting that although the United States has invested a lot of counterterrorism resources on the ground, it has not been able to effectively curb the breeding of terrorism. On the contrary, such assistance has exacerbated the deterioration of the regional security situation and even increased the risk of coups in recipient countries. United States’ counterterrorism failures in Mali and Nigeria are proof of this. The article believes that there are two main endogenous logics that caused the failure of United States’ counterterrorism operation in the Sahel region, namely relationship dislocation and security. Among them, the dislocation of counterterrorism actions leads to counterterrorism actions that deviate from the realistic expectations of regional actors and ignore the role of local knowledge in them. At the same time, this dislocation has led to a serious erosion of mutual trust between the United States and the Sahel countries, exacerbating tensions between the two sides, and leading to governance failures. Securitization has led the United States to ignore the use of inclusive strategies in the process of counterterrorism, which not only eliminates the actual possibility of political settlement, but also fails to eliminate the breeding ground for terrorism, but instead provides new propaganda possibilities for terrorist organizations to recruit members.

At present, with the setback of France and United States in the Sahel region, the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) has also announced its withdrawal, and the security forces in the Sahel region have been severely weakened. While Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso are resistant to France and American’ intervention, this does not mean that Sahel countries are opposed to external involvement. On the contrary, the countries of the Sahel region cannot fight against terrorism without the support of the international community. Under such circumstances, major powers outside the region and international organizations should still take an active part in regional security affairs. However, it should be noted that in the process of participation, major countries outside the region should earnestly abide by the realistic principle of ‘African solutions to African problems’, play the role of ‘active auxiliaries’, and give up competing for dominance in security affairs. At the same time, foreign powers and international organizations need to fully adopt inclusive strategies, and pay more attention to the use of civilian strategies in addition to providing military equipment and technical assistance, so as to eliminate the breeding ground for terrorism.

Author contributions

YZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study is supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (22lzujbkyjh004).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yaohui Wang from Nankai University and Xiaoding Chen from Lanzhou University for their help and support in the writing of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aldrich, D. P. (2014). First steps towards hearts and minds? USAID’s countering violent extremism policies in Africa. Terror. Pol. Viol. 26, 523–546. doi: 10.1080/09546553.2012.738263

Berschinki, R. G. (2007). “AFRICOM’s dilemma: the global war on terrorism capacity building” in Humanitarianism, and the future of U.S. security policy in Africa (Carlisle: U.S. Army War College).

Boudali, L. K. (2007). The North Africa project: The trans-Sahara counterterrorism partnership. New York: Combating Terrorism Center at West Point.

Boulton, A., and Carter, D. B. (2014). Fair-weather allies? Terrorism and the allocation of US foreign aid. J. Confl. Resolut. 58, 1144–1173. doi: 10.1177/0022002713492649

Bray, J. (2011). The trans-Sahara counterterrorism partnership: Strategy and institutional friction. Carlisle: U.S. Army War College.

Brechenmacher, Saskia. (2019). Stabilizing Northeast Nigeria after Boko haram. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/05/03/stabilizing-northeast-nigeria-after-boko-haram-pub-79042 (Accessed July 1, 2024).

Campbell, John. (2017). G5 Sahel: an African (and French) solution to an African problem. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/blog/g5-sahel-african-and-french-solution-african-problem (Accessed April 20, 2024).

CIP Security Assistance Monitor. (2023). Security assistance database. Available at: https://securityassistance.org/security-sector-assistance/ (Accessed June 1, 2024).

Dersso, Solomon A. (2012). The quest for Pax Africana: the case of the African Union’s peace and security regime. Available at: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajcr/article/view/83269/0 (Accessed December 20, 2023).

Donati, Jessica, and Mcbride, Courtney. (2019). Terrorist attacks increase in Africa’s Sahel, U.S. warns. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/terrorist-attacks-increase-in-africas-sahel-u-s-warns-11572636479 (Accessed April 12, 2024).

Epstein, S. B., and Rosen, L. W. (2018). U.S. security assistance and security cooperation programs: Overview of funding trends. Washington, DC: Congress Research Service.

Esmenjaud, R., and Franke, B. (2008). Who owns African ownership? The Africanisation of Security and Its Limits. 15, 137–158. doi: 10.1080/10220460802614486

France 24. (2014). F24 exclusive: Hollande says France will not intervene in Nigeria. Available at: https://www.france24.com/en/20140517-hollande-france-24-exclusive-interview-nigeria-boko-haram (Accessed December 23, 2023)

Global Security. (2018). Joint special operations task force – Juniper shield (JSOTF-JS). Available at: https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/dod/jsotf-ts.htm (Accessed March 11, 2024).

Global Terrorism Database. (2022). Mali_ incidents over time. Available at: https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/search/Results.aspx?chart=overtime&search=mali (Accessed March 8, 2024).

Green, Mark A. (2023). The Sahel now accounts for 43% of global terrorism deaths. Available at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/sahel-now-accounts-43-global-terrorism-deaths (Accessed March 3, 2024).

Harmon, S. (2015). Securitization initiatives in the Sahara-Sahel region in the twenty-first century. Afr. Secur. 8, 227–248. doi: 10.1080/19392206.2015.1100503

Heinrich, T. (2017). Does counterterrorism militarize foreign aid? Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. J. Peace Res. 54, 527–541. doi: 10.1177/0022343317702708

Henneberg, I., and Plank, F. (2020). Overlapping regionalism and security cooperation: power-based explanations of Nigeria’s forum-shopping in the fight against Boko haram. Int. Stud. Rev. 22, 576–599. doi: 10.1093/isr/viz027

Hills, A. (2006). Trojan horses? USAID, counterterrorism and Africa’s police. Third World Q. 27, 629–643. doi: 10.1080/01436590600720843

Huddleston, Vicki. (2009). Statement of hon. Vicki Huddleston, deputy assistant security for Africa, department of defense. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111shrg56320/html/CHRG-111shrg56320.htm (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Institute for Economics and Peace. (2023). Global terrorism index 2023. Available at: https://www.economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/GTI-2023-web.pdf (Accessed March 11, 2024).

Jones, Seth G. (2013). The benefits of U.S. drones in West Africa. Available at: https://www.rand.org/blog/2013/04/the-benefits-of-us-drones-in-west-africa.html (Accessed April 2, 2024).

Joselow, Gabe. (2022). AU seeks regional response to conflict. Available at: https://www.voanews.com/a/au_seeks_regional_response_to_conflicts/1405037.html (Accessed March 20, 2024).

Kfir, I. (2018). Organized criminal-terrorist groups in the Sahel: how counterterrorism and counterinsurgency approaches ignore the roots of the problem. Int. Stud. Perspect. 19, 344–359. doi: 10.1093/isp/eky003

Kingebiel, Stephen. (2005). Africa’s new peace and security architecture. Available at: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/F3_14_2.PDF (Accessed February 21, 2024).

Louis, Natasha. (2023). Increasing terrorism in Africa and American counterinsurgency policy. Available at: https://eeradicalization.com/increasing-terrorism-in-africa-and-american-counterinsurgency-policy/ (Accessed March 11, 2024)

Ning, Y. (2018). A study on Boko haram in Nigeria. Doctoral Dissertation. Kunming: Yunan University.

Noyes, Alexander. (2023). The case for a governance-first U.S. security policy in the Sahel. Available at: https://www.rand.org/blog/2023/06/the-case-for-a-governance-first-us-security-policy.html (Accessed April 12, 2024).

Nyiayaana, K., and Nwankpa, C. I. (2022). AFRICOM and the burdens of securitisation in Africa. Eur. Sci. J. 18, 190–206. doi: 10.19044/esj.2022.v18n20p190

Okaoli, A. C., and Lenshie, N. E. (2022). Beyond military might’: Boko haram and the asymmetries of counter-insurgency in Nigeria. Secur. J. 35, 676–693. doi: 10.1177/0095327X2211216

Olsen, G. R. (2011). Civil-military cooperation in crisis Management in Africa: American and European Union policies compared. J. Int. Relat. Dev. 14, 333–353. doi: 10.1057/jird.2011.6

Pincus, Walter. (2013). Mali insurgency followed 10 years of U.S. counterterrorism programs. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/mali-insurgency-followed-10-years-of-us-counterterrorism-programs/2013/01/16/a43f2d32-601e-11e2-a389-ee565c81c565_story.html (Accessed April 13, 2024).

Ploch, Lauren. (2011). Africa command: U.S. strategic interests and the role of the U.S. military in Africa. Available at: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/RL34003.pdf (Accessed April 8, 2024).

Pope, Wiliam P. (2005). Eliminating terrorist sanctuaries: the role of security assistance. U.S. Department of Defense, march 10, 2005, Available at: https://2001-2009.state.gov/s/ct/rls/rm/43702.htm (Accessed February 21, 2024)

Prime Minister’s Office. (2018). UK and Nigeria step up cooperation to end Boko haram threat. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-and-nigeria-step-up-cooperation-to-end-boko-haram-threat (Accessed December 21, 2023)

Rand, D. H., and Tankel, S. (2015). Security cooperation and assistance: Rethinking the return on investment. Washington, DC: Center for a New American Security.

Sandnes, M. (2023). The relations between the G5 Sahel joint task force and external actor: a discursive interpretation. Canadian Journal of African Studies. 57, 71–90. doi: 10.1080/00083968.2022.2058572

Savell, S. (2021). The costs of United States’ Post-9/11 “security assistance”: How counterterrorism intensified conflict in Burkina Faso and around the world : Watson Institute for International and Public Affair.

Schmitt, Eric. (2014). With schoolgirls taken by Boko haram still missing, U.S.-Nigeria ties falter. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/01/world/with-schoolgirls-still-missing-fragile-us-nigeria-ties-falter.html (Accessed March 3, 2024).

Senate Committee on Armed Services. (2016). Advance policy for Lieutenant General Thomas D. Waldhauser, United States Marine Corps Nominee for Commander. Available at: https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Waldhauser_%20APQs_06-21-16.pdf (Accessed December 11, 2024).

Shurkin, M., Gordon IV, J., Frederick, B., and Pernin, C. B. (2017). Building arBuilding Armies, Building Nations: Toward a New Approach to Security Force Assistance. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation.

Smith, Craig S. (2004). U.S. training African forces to uproot terrorists. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/11/world/us-training-african-forces-to-uproot-terrorists.html (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Subcommittee on Counterterrorism and Intelligence Committee on Homeland Security House of Representatives. (2011). Boko haram: emerging threat to the U.S. homeland. Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CPRT-112HPRT71725/html/CPRT-112HPRT71725.htm (Accessed April 18, 2024).

Tankel, S. (2020). US counterterrorism in the Sahel: from indirect to direct intervention. Int. Aff. 96, 875–893. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiaa089

Thurston, A. (2017). Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM): An Al-Qaeda affiliate case study. Arlington: Center for Naval Analyses.

Turasz, M. E. A. (2014). Forced shortage: Security force assistance missions. Master's Degree Dissertation. Alabama: Air University.

Ucko, D. H. (2019). Systems failure: the US way of irregular warfare. Small Wars Insurg. 30, 223–254. doi: 10.1080/09592318.2018.1552426

United States Congress. (2021). S.615 - trans-Sahara counterterrorism partnership program act of 2021. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/615/text (Accessed March 10, 2024).

United States Department of State. (2013). Eight annual trans-Sahara counterterrorism partnership conference. Available at: https://2009-2017.state.gov/p/af/rls/rm/2013/216028.htm (Accessed June 15, 2024).

United States Government Accountability Office. (2018). U.S. agencies have coordinated stabilization efforts but need to document their agreement. Available at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-18-654.pdf (Accessed June 15, 2024).

Wade, Isebel. (2016). Burning bridges: American security assistance and human rights in Mauritania. Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2365&context=cmc_theses (Accessed March 9, 2024).

Wang, T., and Li, J. (2022). Differentiation and recombination of extremist groups in Sahel from sociocultural perspective. Arab World Studies 4, 98–120. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5161.2022.04.006

Warner, L. A. (2014). The trans Sahara counter terrorism partnership: Building partner capacity to counter terrorism and violent extremism. Arlington: National Security Analysis.

Warner, Jason, Lizzo, Stephanie, and Broomer, Julia. (2022). Assessing U.S. counterterrorism in Africa, 2001-2021: summary document of CTC’s Africa regional workshop. Available at: https://ctc.westpoint.edu/assessing-u-s-counterterrorism-in-africa-2001-2021-summary-document-of-ctcs-africa-regional-workshop/ (Accessed March 9, 2024).

Watts, S. (2015). Identifying and mitigating risks in security sector assistance for Africa’s fragile states. Available at: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR808/RAND_RR808.pdf (Accessed April 20, 2024).

Watts, S., Johnston, T., Lane, M., Mann, S., McNerney, M. J., and Brooks, A. (2018). Building Security in Africa: Technical Appendixes. California: Rand Corporation.

Wong, M. (2007). Counterterrorism issues and approaches. Quote from Center for Strategy and International Studies. (2008). Intergrat5ing 21st century development and security assistance, center for strategy and international studies. Available at: https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/media/csis/pubs/080118-andrews-integrating21stcentury.pdf (Accessed June 21, 2024).

Keywords: security engagement, securitization, Sahel region, counterterrorism, TSCTP

Citation: Zhu Y and Gao W (2024) The Sahel on the edge of the abyss? Why U.S. counterterrorism engagement has failed to achieve its goal? Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1466715. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1466715

Edited by:

Jiajia Zhang, Ocean University of China, ChinaReviewed by:

Xiaoxin Yang, Ocean University of China, ChinaJiwen Qu, Yunnan Nationalities University, China

Copyright © 2024 Zhu and Gao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wanni Gao, Z2Fvd25AbHp1LmVkdS5jbg==

Yuan Zhu

Yuan Zhu Wanni Gao

Wanni Gao