- Department of International Studies, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, Jiangsu, China

This paper examines the narratives of the European Council, European Commission, and European Parliament regarding the European refugee crisis. Although the relevant scholarly research suggests that the EU Institutions held different perspectives about the refugee crisis, this paper argues that there was no such a clash of perspectives. This paper builds on the Copenhagen School’s securitization framework as complemented with subsequent methodological tools to support the author’s arguments. The findings suggest that despite the similarity in the views held by the main EU Institutions considering the refugees’ influx, there was a variation in the intensity of their securitizing narratives. Theoretically, this study develops an understanding of the importance of the securitization narratives’ intensity. Methodologically, this study introduces the Securitization Narratives Continuum, a research tool that facilitates the assessment of securitization. Empirically, this is the first study to interview and take into account the opinions of the securitizing actors.

1 Introduction

Between 2015–16, the EU dealt with an unparalleled refugee crisis. To some of the main EU Institutions’ officials, the crisis resembled to an existential threat. Some of these officials attempted to securitize the crisis. The process by which non-security issues elevate, through discursive means, onto the security realm, is called securitization (Buzan et al., 1998). Although there is scholarly research that addresses how the EU member states securitized (Maricut, 2017; Moreno-Lax, 2018; Ceccorulli, 2019; Hintjens, 2019; Léonard and Kaunert, 2020; Kaunert et al., 2021; Panebianco, 2021), a-securitized (Sliwinski, 2016), or metasecuritized (Stivas, 2023) the refugee crisis, little has been written about the securitizing narratives of the key securitizing actors at the EU level and the intensity of these narratives.

Hence, this study aims attention at the securitization of the refugee crisis at the level of the EU Council, the European Commission (Commission), and the European Parliament (EP). To reveal the extent to which these main EU Institutions’ officials securitized the refugee crisis, this paper builds on the securitization theory of Copenhagen School of Security Studies (CSSS-Buzan et al., 1998) and a subsequent methodological contribution, the Securitization Narratives Continuum (SNC). The SNC is utilized to emphasize the variations of the securitizing narratives’ intensity. The SNC further assists researchers with categorizing the intensity of the securitizing rhetoric into four levels: normal, alarming, challenging, and existentially threatening.

This study concludes that although, in broad terms, the EU Institutions’ leaders shared similar perspectives about the extent to which the refugee crisis threatened the EU and about the most appropriate action to tackle the influx, their securitizing discourses varied in intensity. This paper further underlines the importance of combining qualitative (predominantly) with semi-quantitative methods of securitizing narratives assessment.

Theoretically, this study contributes to the current literature by developing assumptions about and emphasizing the importance of the intensity of the securitization speech acts during securitization processes. Methodologically, this study introduces the SNC, a research tool that facilitates the detailed assessment of securitizations. Empirically, this is the first study to include the opinions of the securitizing actors into its findings.

The next section presents the current literature considering securitization theory, the audience acceptance element of the securitization theory, and the securitization of the European refugee crisis. Section three articulates the methodological underpinnings of this study. It is followed by the detailed representation of the security speech acts and their intensity, the emergency measures, the targeted audience identification, and the assessment of the audiences’ response. The last section discusses the research findings and concludes this paper.

2 Securitization in the literature

2.1 The securitization components

Securitization is a process (Wæver, 1995) through which a securitizing actor (or the securitizer) represents a particular topic as an ‘existential threat’, which is then exhibited to a targeted audience for endorsement to activate extraordinary measures and practices to control it (Léonard and Kaunert, 2010). The founders of the securitization theory argued that only when the targeted audience accepts the speech act, the normal politics are suspended and emergency measures are adopted to tackle the alleged threat (Buzan et al., 1998).

However, despite the insistence of the CSSS scholars on importance of the audience acceptance component of securitization, the question of what or who constitutes the securitization audience has been partially addressed (Vaughn, 2009; Hintjens, 2019; Floyd, 2020; Murphy, 2020; Van Rythoven, 2020).

Balzacq (2011, p. 9) conceives the audience as an ‘empowering audience’ that has ‘a direct causal connection with the issue and […] the ability to enable the securitizing actor to adopt measures in order to tackle the threat.’ Roe (2008), Salter (2011), McDonald (2008), and Côté (2016) affirm Balzacq’s claims about the audience’s active role and suggest that apart from just accepting the security speech acts, the audience also approves the securitizing measures. Sometimes, the audience and the actor can be indistinguishable. Sperling and Webber (2017) call the interdependence and interchangeability between the actor and the audience of securitization, ‘recursive securitization.’ NATO, for example, as an organization is simultaneously the securitizing actor that acts in the name of its members and the ‘framework of audience participation’ where the NATO members agree, accept or reject the security speech acts (Sperling and Webber, 2017, p. 28). At the EU context, Lucarelli (2019) emphasized that there exist various audiences. Among them, one is the empowering audience that can legitimize the speech act. Other audiences at the EU level are described as attentive audiences. The latter lack legitimizing role but can influence the debates on security. Lucarelli (2019) claims that in the case of the EU, the member states, via their voting entitlements in the Council of Ministers constitute the legitimizing audience. Lucarelli (2019) further underlines that in cases of collective securitization at the EU level, the actor-audience relationship is unique. The actor and the audience engage in a process of recursive interaction where securitization of an issue is intersubjectively produced. Scholars who employed the CSSS’s framework only occasionally discussed the audience acceptance component of securitization (Baele and Thompson, 2017). Securitization researchers have not addressed the issue of the intensity of the securitizing speech acts and the effects that this can have to the entire securitizing process.

2.2 Securitization of the refugee crisis at the EU level

Various studies examined the securitization of the refugee crisis at the EU level but none of them dealt with the intensity of the securitization narratives or the relationship between securitization discourse intensity and securitizing measures’ stringency. To draw conclusions about the securitization of the refugees’ issue at the EU level, Léonard and Kaunert (2020) scrutinized the activities of FRONTEX and argued that non-discursive practices could be as important as discursive in the process of the social construction of a topic as a security threat. Ceccorulli (2019) examined the EU’s discourse as emanated from the 2015 Agenda on Migration to suggest that the EU’s narrative recognized two challenges to the security of the bloc: the massive influx of migrants and the unraveling of the Schengen regime. Moreno-Lax (2018) described a duality in the EU’s discourse which shifted from ‘a pure securitization logic of raw pre-emption of unauthorized movement’ toward an ‘increasingly human rights friendly narrative’ that represented the migrants as victims (Moreno-Lax, 2018, p. 119). Similarly, Panebianco (2021) argued that after the refugee crisis, the Commission reconceptualized migration from a security threat to an issue of human security, with the human security of the migrants being the referent object of security. Hintjens (2019) discussed the speech acts and audience response at the EU level to conclude that some of the securitization attempts failed. Kaunert et al. (2021) described the whole process of the securitization of the refugee crisis at the EU level as an example of collective securitization. Maricut (2017) studied the narratives of three EU Institutions to argue that their narratives, priorities, and approaches toward the refugee crisis varied. This ‘clash of perspectives’ between the EU Institutions, but also between the EU member states, was also underscored by Dagi (2017).

3 Research design and methodology

Theoretically, this study builds on the CSSS framework as supplemented with the SNC. It does so, because a framework focused on security seems to be the most appropriate to investigate the manner by which immigrants and refugees were socially constructed as security threats.

Empirically, this study builds on primary (semi-structured interviews with securitizers) and secondary sources (EU official documents). Discourse analysis, the most suitable analytical tool of securitization (Léonard and Kaunert, 2019), is applied on hundreds of the main EU Institutions’ press releases, speeches, and statements. We also combine the conclusions drawn from the qualitative examination of the speech acts (manual identification of themes in the readings of various documents) with the results of a quasi-quantitative assessment. Purely quantitative assessments of securitizing narratives have been conducted in the past (Karyotis and Patrikios, 2010; Baele and Sterck, 2015; Baele and Thompson, 2017). However, a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis may shed more light to the security speech acts and their intensity than a purely quantitative or purely qualitatively assessment.

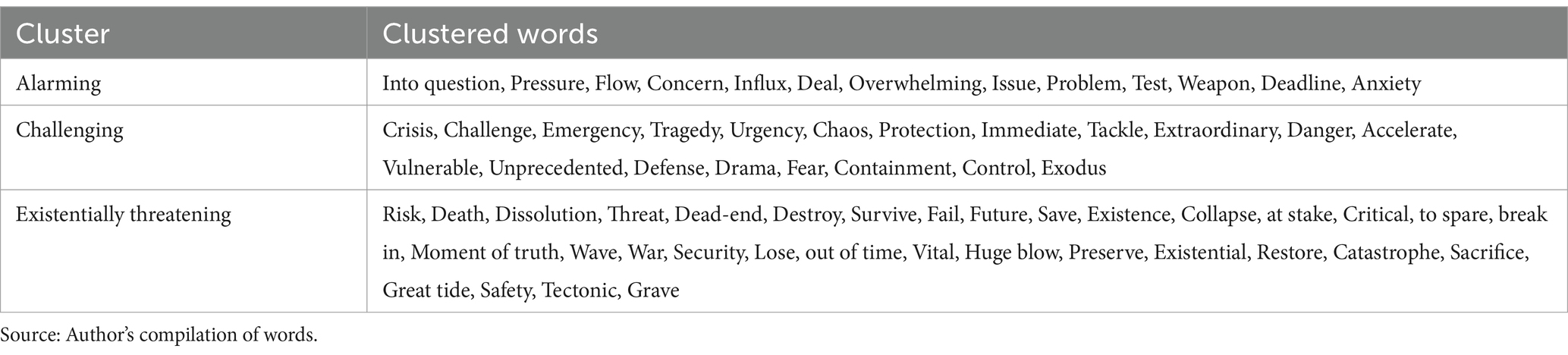

The close examination of the statements, speeches, and interviews of the three main EU Institutions’ leaders suggests that the EU officials utilized potentially securitizing discourse in just 83 out of the hundreds documents relevant to the refugee crisis (29 from the European Council, 38 from the Commission, and 16 from the European Parliament). We categorize the intensity of the securitization rhetoric into alarming, challenging, and existentially threatening. Word-clusters manually generated are used to facilitate the exercise of distinguishing the speech acts to three levels of intensity. As it is illustrated in Table 1, some words (or combinations of words) have stronger securitization connotations than others.

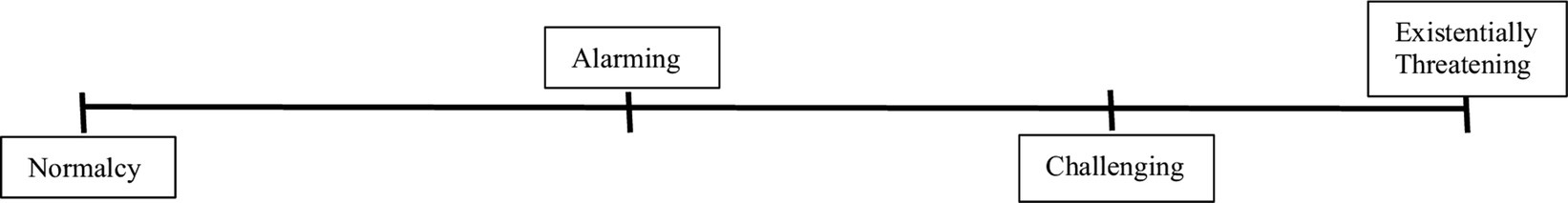

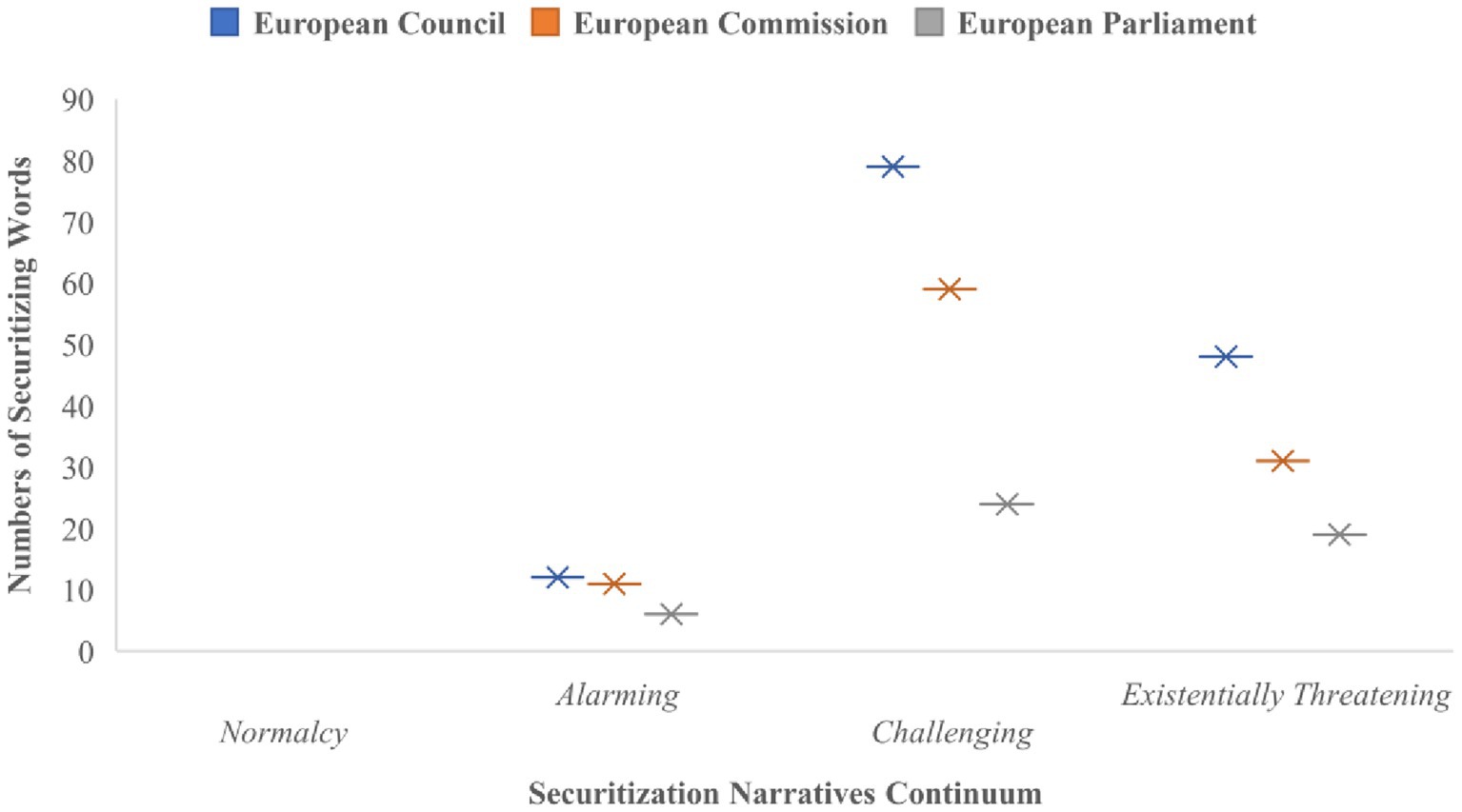

Illustrated in a continuum [inspired by Léonard and Kaunert (2019)], ‘alarming’ and ‘challenging’ are situated between ‘normalcy’ and ‘existentially threatening’ narratives (see Figure 1), with alarming being placed close to the former and challenging near by the latter. The number of the words corresponding to alarming, challenging, and existentially threatening is manually calculated. The ‘challenging’ cluster could also be described as the cluster of ‘riskification.’ Riskification according to Cory (2012) involves a speech act, but a speech act that does not refer to direct causes of harm but to conditions which result in the possibility of harm.

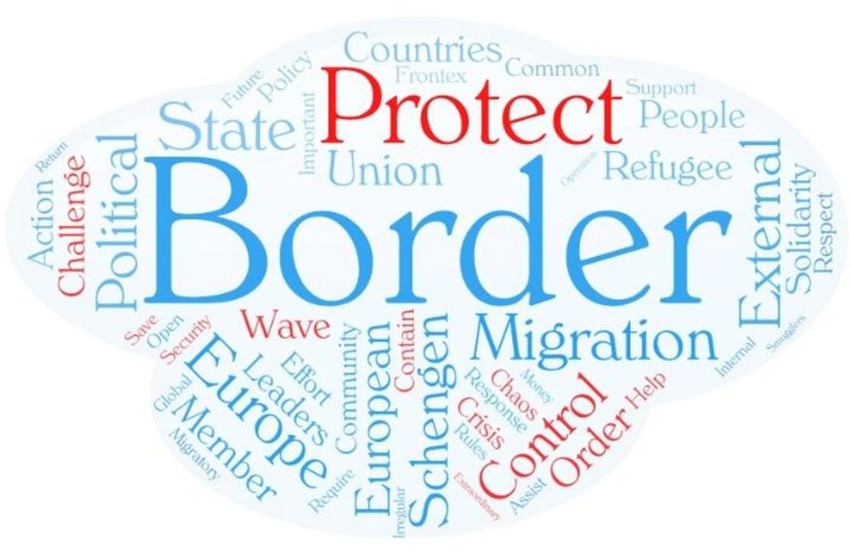

To further support the discussion about the discursive representation of the migrant crisis by the EU institutions, word-clouds that depict each EU Institution’s securitizing rhetoric are taken into account.

4 The securitization of the refugee crisis at the EU level

Securitizing narratives and measures emanate not only from the EU Member States’ but also from the EU Institutions (Kaunert, 2009; Guirandon, 2010; Ceccorulli, 2019; Lucarelli, 2019; Sperling and Webber, 2019). Three of the EU Institutions, the European Council, Commission, and European Parliament, possess the political and legislative capacity to securitize any issue of their concern. Their securitizing narratives are examined for the purposes of this study.

4.1 The security speech acts

4.1.1 European Council

The official of the European Council with the highest media exposure is its President. Between 2014 and 2019, the European Council’s President was Donald Tusk. Although in the first months of 2015 Tusk represented the lives of the refugees to be at stake, this changed when the numbers of the EU border-crossers surged exponentially. After June 2015, Tusk portrayed the ‘migratory waves’ as a ‘weapon against neighbors’ in a kind of a ‘new hybrid war’ (Tusk, 2015c). Subsequently, Tusk presented the refugee crisis as a threat and used words with strong symbolic meaning to depict the situation—‘chaos’, ‘migration waves’, ‘drama’, ‘unprecedented’, ‘exodus’, ‘new hybrid war’, ‘catastrophe’, ‘tectonic changes’, ‘great tide’, ‘ticking clock’, ‘existential challenge’, ‘collapse’, ‘dangerous times’, ‘insecurity’, and ‘fear’ (Tusk, 2015a,b,c,d,e).

The loss of control of the EU’s external borders was discursively linked to the reintroduction of intra-EU border controls and the endangerment of Schengen Agreement (Tusk, 2015e). ‘Without changing the [chaos at the EU’s external borders] the Schengen area will only exist in theory’ Tusk (2015f) warned in September 2015. ‘Europe without its external borders equals Europe without Schengen […] and this will lead us, sooner or later, to a political catastrophe’ he added (Tusk, 2015c). Strengthening the external borders was one of Tusk’s proposed solutions to ‘save Schengen’ and to ‘save Europe’ (Tusk, 2015a). ‘Preserving Schengen’ would be ‘the key for the future of the EU’, he alerted (Tusk, 2016). Hence, the qualitative assessment of Tusk’s statements indicate that he used intense securitization rhetoric. However, the quasi-quantitative analysis suggests otherwise. The word-cloud (Figure 2) of Tusk’s selected statements reveals that he focused his narratives mainly on the situation at the EU borders. Words like ‘protect’ and ‘control’ dominated his narratives. The word ‘challenge’, which is moderately charged with security meaning, was uttered more frequently than the more intense ‘crisis.’ Words with strong security connotations like ‘chaos’, ‘save’, ‘security’, ‘wave’, and ‘contain’ are slightly visible in the cloud. The cluster analysis confirms the above findings (Graph 1). Terms associated with threats to the existence of the EU have been used less often than concepts falling under the ‘challenging’ cluster.

Figure 2. Word cloud-European Council narratives. Generated with WordArt. The cloud depicts the 50 most frequently repeated words in the assessed statements. Source: Author’s compilation of words.

GRAPH 1. Securitization narratives continuum-EU institutions combined. Source: Author’s compilation of words.

4.1.2 European Commission

At the Commission’s level, three officials were the most entitled to ‘speak’ about the migration crisis: (1) the President, Jean-Claude Juncker; (2) the First Vice-President, Frans Timmermans, and (3) the Commissioner for Migration, Dimitris Avramopoulos. In general, the three Commission’s officials framed the situation more like a ‘migration challenge’, ‘migration crisis’, ‘refugee crisis’, and ‘migratory pressure’ rather than an existential threat.

In January 2015, Avramopoulos included immigration in the ‘myriad challenges’ faced by the EU and associated it with the rise of racism and xenophobia in Europe (Avramopoulos, 2015). Timmermans (2015), on the other hand, portrayed legal immigration positively as a ‘necessity for the future of the [EU countries] societies and economies’ and pleaded to the EU citizens to support it.

However, soon the ‘migration challenge’ was reframed into a ‘refugee crisis.’ In November 2015, the re-introduction of intra-EU border controls was perceived as a survival issue for the EU integration project. Juncker warned that the border-controls endangered Schengen (Juncker, 2015d). Following the ‘EU-Turkey Statement’ and the drastic reduction at the refugee numbers, the Commission gradually reframed again the issue as a ‘challenge.’

Hence, the qualitative assessment of the speech acts suggests that the Commission’s officials framed the issue mostly as ‘challenging’ and ‘alarming’ rather than as existential threatening. However, the word-cloud (Figure 3) shows that the Commission’s officials used the word ‘crisis’ more times than ‘challenge.’ Words with strong and symbolic meaning like ‘threat’ and ‘war’ also appear on the cloud. Nevertheless, as the size of these words indicates, they were mentioned less frequently than mild-securitizing words.

Figure 3. Word cloud-European Commission narratives. Generated with WordArt. The cloud depicts the 50 most frequently repeated words in the assessed statements. Source: Author’s compilation of words.

The clustering of the Commission’s securitizing words (Graph 1) confirms that the Commission’s officials represented the situation more as ‘challenging’ than as ‘existential threatening’ and ‘alarming.’ The placement of the words on the continuum indicates that the securitizers of the Commission used in most of the cases mild rather than intense securitizing rhetoric. This, to a certain extent, also confirms the findings of the discourse analysis.

4.1.3 European Parliament

To analyze the securitizing discourse of the European Parliament, the statements of certain influential persons, the President of the European Parliament, and the MEPs of the European People’s Party (EPP) and the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) are considered.

It is noteworthy that in 2015, the MEPs from the S&D denounced the existence of a migration crisis. ‘A European Union of half a billion people should not call crisis the arrival of 250,000 migrants’ argued S&D’s Kyenge (2015). The EP’s President, Martin Schulz, followed a similar line. He argued that the ‘migration and refugee question’ was an EU issue and a ‘common challenge’ of which the resolve required solidarity (Schulz, 2015b,c). However, soon Schulz reframed the refugee ‘question’ as an emergency that could ‘put into question the imperfect EU framework [the EU had] in place’ (Schulz, 2015d). Pittella (2015) of the S&D warned that ‘national selfishness’ could ‘condemn Europe to its dissolution’. Along the same line, Schulz (2015e) alerted that ‘the centrifugal forces of national egotism threaten to tear our union apart’ and warned that ‘beggar thy neighbor policies [would] destroy our European project’. Schulz (2015a) represented the situation as an ‘epochal challenge’.

From a quasi-quantitative perspective, the word-cloud (Figure 4) of the EP securitizing actors’ narratives shows that the situation was depicted more as a ‘crisis’ than as a ‘risk.’ Words with strong security connotations like ‘save’, ‘destroy’, and ‘survive’ appear in the cloud. However, these words appear in smaller textual representation than the words ‘crisis’ and ‘challenge.’ This illustrates the non-insistence of the EP’s securitizers to frequently use intense securitizing wording.

Figure 4. Word cloud-European Parliament narratives. Generated with WordArt. The cloud depicts the 50 most frequently repeated words in the assessed statements. Source: Author’s compilation of words.

The assessment of the clustered words (Graph 1) suggests that strong and mild securitizing words were uttered almost in identical instances by the EP’s officials. In fact, words with existentially threatening connotations emerged 20 times while ‘challenging’ words popped up 24 times. A discrepancy therefore appears between the qualitative and quasi-quantitative assessment findings. While the discourse analysis and the word-clustering attest the intensity of the EP officials’ securitizing narratives, the word-cloud falls slightly short of detecting the ferocity of the EP’s officials securitizing discourse.

4.2 The emergency action

For a securitization to occur, the actions do no need to be necessarily of an emergency nature (Sperling and Webber, 2019). A collective securitization, as in the case of the securitization of migration at the EU level, can take place when there has been a significant shift toward a securitizing discourse and transformation of the security governance (Sperling and Webber, 2019). To strengthen the collective action in line with prior norms and rules, counts as securitization (Lucarelli, 2019). The emergency action embedded in the securitization process can also be understood as being path dependent as it draws upon existing policies and rules (Lucarelli, 2019). Sometimes, pre-existing security practices may, through security discourse, become legitimized and institutionalized (Sperling and Webber, 2019). And this exactly is what happened with the securitization of the refugee crisis at the EU level. Building upon existing policies and frameworks, the EU managed to transform its security governance.

4.2.1 Reallocation of financial resources

Between 2015 and 2016, the EU substantially increased the budget allocated to migration-related policies. The EU allots an explicit funding for migration, asylum, and integration policies (European Parliament, 2018). According to a study commissioned by the EP, the commitments for nine EU funds/agencies/systems for the period from 2014 to 2020 increased from EUR8.4 billion, of the initially agreed allocation, to EUR14.2 billion (European Parliament, 2018). More particularly, the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund increased from EUR3.31 billion initial allocations to EUR6.6 billion, the Internal Security Fund increased from the initial allocation of EUR3.7 billion to EUR3.8 billion, the contributions to FRONTEX from EUR628 million to EUR1,638 million, the funding for EASO from EUR109 million to EUR456 million, and for EUROPOL, from EUR654 million to EUR753 million (European Parliament, 2018).

The large increment of the EU budget allocation toward dealing with the migration issue was also recorded in the European Commission’s documents. The EU allocated EUR17.7 billion to deal with the migration crisis in the period 2015–2017 (Deighton and Roberts, 2016). Moreover, between 2015 and 2018, the EU doubled the budget. The initial allocation amounted to EUR9.6 billion, but the final allocation reached EUR22 billion. The ‘increase to react to bigger needs’ was equal to EUR6.6 billion, the ‘Trust Fund for Syria’ amounted to EUR600 million, the pledges from the London and Brussels Conference were at EUR1.6 billion, the ‘EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa’ amounted EUR2.6 billion and the ‘Facility for the Refugees in Turkey’ was allocated EUR1 billion. The reports of the EP and the Commission testify the EU Institutions’ success to achieve larger financial resources contributions by the member states.

4.2.2 European border coast guard agency (EBCG)

It was at the peak of the refugee crisis when the Commission shifted its focus on ‘managing migration more effectively, improving the internal security of the EU, and safeguarding the principle of free movement of persons’ (Juncker, 2015c). To achieve that, the Commission proposed to expand FRONTEX into a full-fledged EBCG. The new organization became fully operational in October 2016. EBCG had an expanded mandate, double staff than that of FRONTEX, and money to procure equipment and facilitate its expanded mission (Floyd, 2019).

Questions about the compliance of the EBCG Regulation with the EU’s procedural requirements are raised because of the short period (just 10 months) between the Commission’s proposals for the establishment of the EBCG Agency and the announcement of its official launch. This is rarely observed at the EU’s policymaking. Procedurally, the EBCG Regulation was adopted under the ordinary legislative procedure. However, no procedural rules were overlooked. The EBCG Regulation was a result of consultations between the European Parliament and the Council. The urgency by which the Regulation was adopted seems to be the result of inducement by the European Council and the Commission toward the EP and the Council of Ministers to deal with the refugee crisis in an immediate and effective manner. The EBCG Regulation is therefore an emergency measure at the EU level built upon pre-existing policies and frameworks. The extraordinariness of the EBCG lies mainly on the velocity of its adoption.

4.2.3 EU-Turkey statement

The EU-Turkey ‘Statement’, as it was branded, laid down conditions for the return of individuals who irregularly crossed by boat from Turkey to Greece, back to Turkey, in exchange for increased EU resettlement of Syrians from Turkey, large sums of aid to Turkey, and the abolishment of EU visa restrictions for Turkish nationals (European Council, 2016). Questions regarding the legality of the ‘Statement’ were raised with most of them focusing on the naming of the agreement as ‘Statement.’ In fact, the ‘Statement’ was an agreement between the EU member states and Turkey, but it was branded as EU-Turkey Statement.

Article 218 TFEU (European Union, 2012) outlines that when the Council negotiates and concludes agreements with third countries it should obtain the consent of the EP. However, because the agreement between the EU and Turkey was branded as a ‘statement’ instead of ‘agreement’ (although it was essentially an agreement with a third country), the EP was not requested for, and did not give its consent, as required by the Treaties. It appears, therefore, that the Council deliberately branded the agreement, as a ‘statement’, to evade the potential procedural delays and negation of the EP. By not obtaining the consent of the EP before concluding the agreement with Turkey, the EU appears to have violated procedural rules as outlined in Article 218 TFEU. The potential procedural violation and the accelerated pace of the negotiations qualify the ‘Statement’ as an emergency measure in the securitization context.

4.3 The identity of the audience

4.3.1 European Council

Through his statements, Tusk warned that the lack of respect to ‘our rules’ and the lack of solidarity with the frontline member states could risk the existence of Schengen (Tusk, 2015g). It looks like Tusk, by emphasizing ‘solidarity’ and respect to ‘our rules’ targeted directly at the leaders of the EU member states who could express their solidarity through budgetary or staff allocations. In another case, before meeting with Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian Prime Minister, Tusk (2015b) explicitly revealed his targeted audience. ‘If leaders’, he said, ‘do not demonstrate good will, solidarity […] will be replaced by political blackmail, divisions […]’. Tusk further demanded an ‘enormous effort of all institutions’ and a ‘major increase in spending’ (Tusk, 2015b). This message was directed toward the member states’ governments and EU Institutions which should expand their efforts and spending.

At the peak of the crisis, Tusk (2015d), when directly addressing the European Parliament, requested its help to enhance the mandate of Frontex. The expansion of Frontex’s mandate would be subject to the ordinary legislative procedure in which the EP is a co-legislator (together with the Council). The EP’s speedy and positive response was needed. In that case, the MEPs were Tusk’s targeted audiences. This confirms the thoughts of Sperling and Webber (2019) who emphasized the importance of the legitimizing audiences in the processes of collective securitizations. Here, the MEPs constitute a part of the legitimizing audience as their votes were necessary for the rapid operationalization of the EBCG.

Although the textual and contextual investigation point to the EU member states’ governments and EU Institutions as the main targets of Tusk’s speech acts, Interviewee 3 added that the EU public was also targeted by Tusk. At the peak of the refugee crisis, ‘the solidarity of the European public opinion was necessary for the plans of the EU to deal with the migratory pressures to succeed’ (Interview 3). Thus, the EU member states’ leaders, the EU Institutions, but also the EU public emerge as the targeted audiences of the European Council’s President.

4.3.2 European Commission

The Commission has been described as the main securitizing actor at the EU level (Kaunert, 2009; Lucarelli, 2019). In January 2015, Avramopoulos (2015) made an explicit reference to the general public and to the need for changing its negative perception about migration. In May, Timmermans (2015) explicitly requested the citizens’ support, indicating that the general public was his main audience.

In other instances, the text of the Commission officials’ statements suggested that they pleaded for a ‘European response’ and a solution at the European level. The direct targets of such rhetoric were the EU member states’ leaders and Ministers of Home Affairs, Migration or Security who could support (or reject) the Commission’s initiatives in the Council of Ministers. When the President of the Commission demanded the deployment of more staff and the release of additional funds for combating the crisis (Juncker, 2015a,b) he obviously targeted the governments of the EU member states which are empowered to allocate such resources. But budgetary powers are also vested with the EU Institutions which, hence, were also targeted by Juncker’s rhetoric. From a textual and contextual perspective therefore, multiple audiences were destined to receive by the Commission officials’ narrative. The officials of the Commission confirm these findings.

An official who dealt with the Commission’s communications during the crisis argued that the Commission’s main audience was ‘the EU organs’ that hold legislative powers: the EP and the Council of Ministers (Interview 1). This is because ‘only when the MEPs and the Ministers of various Council configurations accept the proposed by the Commission legislation, the latter becomes binding EU law’ (Interview 1). Interviewee 1 further recognized the public opinion, the governments of the member states of the EU, and the press as additionally targeted audiences (Interview 1). Another interlocutor, Interviewee 5, stated that the EP, ‘to whom [the College of Commissioners] are accountable,’ and the EU member states were the Commission’s targets. Interviewee 2 added the national parliaments to the targeted audiences of the Commission’s communications because they can legitimize certain decisions related to migration and asylum policy. The interlocutor further considered the European public as an ancillary audience (Interview 2). The role of the European public was further stressed by Interviewee 5. Various audiences seemed therefore to be targeted by the Commission’s speech acts. Prominent among them were the EU member states’ governments, the EU Institutions, and the EU’s general public.

4.3.3 European Parliament

In the case of the EP, Schulz (2015d) targeted his securitization narrative directly toward the Council of Ministers and demanded it to ‘proceed quickly’. In another instance, Pittella (2017) called explicitly at the ‘European Institutions along with all member states’ to ‘face this [migration challenge] together’. According to Interviewee 4, the EP’s targeted audience was the European public and the EU Institutions. The EP’s presidency desired to inform the public about ‘the calibre of the immigration issue’ and to emphasize that ‘the only possible solution was to work together, to cooperate, and to have a fair distribution of refugees’ (Interview 4). Hence, analogously to the targeted audience(s) of the European Council and the Commission, the EP securitizers’ targeted the EU Institutions and EU public. This position confirms the considerations of Lucarelli (2019) who distinguished between the empowering or legitimizing audiences (the other EU institutions in our case), and the attentive audiences who influence the security discourse (the EU public and EU member states in our case).

4.4 The response of the EU institutions and the member states

To draw conclusions on the ‘audience acceptance’ component in the context of the refugee crisis, this study examines how the three main targeted audiences responded to the speech acts. The response of the EU Institutions and member states can be detected in the voting procedures that aimed to legitimize the proposed emergency actions. The EU Institutions, therefore, especially those with voting mandates (the EP and the Council) constitute the empowering or legitimizing audience. The sentiments of the EU public, the attentive audience that can influence the security debates, toward the referent object of security are revealed by surveys and opinion polls disseminated before and during the refugee crisis.

4.4.1 EU institutions and EU member states

Considering the EBCG, both the Council of Ministers and the EP were involved in its legitimation process. The MEPs voted in favor of the EBCG by 483 votes to 181 (European Parliament, 2016) after agreeing with the Council of the EU on the text of the proposed Regulation (Council of the European Union, 2016). Thus, a significant proportion of one of the securitizing actors’ targeted audiences resonated with the securitizing discourse. Moreover, since the Council of Ministers represents the interests of the member states’ governments at the EU decision-making procedures, its positive voting demonstrates that a significant number of the EU member states’ governments also accepted the securitizing move.

As for the EU-Turkey Statement, this was proposed and sponsored by the European Council. The support of the Council of Ministers was guaranteed since the Ministers act as agents of the Heads of their States in the Council configurations. Considering the EP, despite being ignored, it neither resisted to the EU entering in that type of agreement with Turkey nor challenged the procedural legality of the ‘Statement’ before the Court of Justice of the EU. Thus, the EP and the MEPs accepted the security speech acts and empowered the Council to proceed with the deal with Turkey. Similarly, considering that the generous reallocation of human and financial resources to tackle the refugees’ outbreak was implemented without meeting any substantial resistance neither at the EP nor at the Council’s configurations, one could argue that the securitization narrative of the EU Institutions’ leaders was accepted by the empowering audiences.

4.4.2 European public opinion

One way to anticipate the response of the public to the securitizing discourse is to reveal the sentiments of the EU citizens about immigrants from outside of the EU. Between 2015 and 2016, 57 and 58 per cent of the EU populace confessed having developed negative feelings toward third-country immigrants (European Commission, 2015, 2016). During the same time, five out of 10 Europeans viewed immigrants as a burden for their countries (47 per cent in 2015, 50 per cent in 2016 – European Commission, 2015, 2016).

The negativity of the Europeans was not lower when the pollsters asked the opinion of the public explicitly about the refugees. A PRC survey revealed that 35 per cent of the public associated refugees with crime (Pew Research Center, 2015) and with taking the jobs and social benefits from the locals (Pew Research Center, 2016). Even the refugees from Syria were considered as major threats by more than half (50.6 per cent) of the respondents (Pew Research Center, 2016). 59 per cent believed that the refugees increased domestic terrorism (Pew Research Center, 2016) while 50 per cent described the refugees as economic threats (Pew Research Center, 2017).

Although the results of the opinion polls do not demonstrate a direct acceptance of the securitizing moves by the European public, they indicate that large majorities considered immigrants in general and refugees in particular as threats to their national, economic, societal and individual security.

The detailed analysis of the three main components of securitization indicates that even at the EU level, the refugee crisis was successfully securitized. The leaders of the main EU Institutions repeatedly uttered security speech acts throughout the refugee crisis. The securitizing moves were followed by emergency measures. The identified main targeted audiences did not reject the securitizing rhetoric nor the emergency measures. Thus, at the EU level, despite the variation in the intensity of their securitizing narratives, the leaders of the EU Institutions performed a successful securitization of the refugee crisis.

5 Discussion

In the process of collective securitization and recursive interaction among the main EU Institutions, it is inevitable for the institutions’ narratives and preferred course of action to tackle the alleged threat to vary. Dagi (2017) and Maricut (2017) argued that there was a clear clash of perspectives among the EU Institutions. However, the findings of this study suggest that there was a common view among the EU Institutions about the refugee the crisis. They all considered the refugee crisis or some of its aspects, as a security issue. However, the intensity of the securitizing narratives used by the Institutions” main securitizing actors varied.

This is clearly visualized in the word-clouds of the EU institutions’ speech acts (Figures 2–4) and further affirmed in the SNC (Graph 1).

Donald Tusk used words that denoted an existential threat meaning to the refugee crisis many more times than the officials of the EP and the Commission. Tusk also represented the situation as ‘challenging’ more times than the officials of the Commission and the EP. The three main EU Institutions framed the outbreak as ‘challenging’ and ‘threatening’ more than ‘alarming.’ Similar findings emerge from the qualitative analysis too. The officials of the European Council and EP regularly represented the situation as an existential threat. Those of the Commission though, represented it more as challenging than as existentially threatening. Despite the variation in the intensity of the securitizing narratives, the EU officials agreed on the emergency measures: the operationalization of the EBCG, ‘Europeanization’ of the crisis, and reallocation of resources.

Considering the rationale behind the variation in the securitization intensity of the EU Institutions, this lies mainly at their backgrounds, competencies, and expectations from the crisis. The European Council, lacking any formal legislative powers, utilized the most intense securitization rhetoric among the EU Institutions to alert the EU organs with legislative prerogatives—the EP and the Council, to adopt the desired measures rapidly and effectively, and to raise no procedural obstacles to the conclusion of the agreement with Turkey.

The intensity of the Commission’s securitizing rhetoric was milder than that of the European Council. However, the Commission’s officials did not completely refrain from using acute securitizing wording. Like the European Council’s officials, the Commission’s actors utilized securitizing rhetoric to ensure that proposed measures would be set onto the agenda and be adopted. This is reasonable considering that the Commission does not possess legislative powers like the Council and the EP. The Commission’s main role is to initiate new legislation. But in the process of collective securitization, as this happens at the EU level, the Commission can turn into the main securitizing actor and the EU Institution benefiting most from securitizing an issue (Lucarelli, 2019).

Regarding the Commission’s utilization of securitizing rhetoric to recommend a generous increase of the budgetary spending, this was triggered by the Commission’s relatively limited budgetary competencies. With the ultimate budgetary powers lying with the EP and the Council, the Commission, with its securitizing narrative attempted to counterbalance its comparative weakness in the budgetary process and persuade the other two, more powerful on that matter EU Institutions, to endorse the draft budget rapidly.

As for the EP, the intensity of its speech acts was milder than that of the Commission or the European Council. In most of the cases, the EP’s officials urged the member states to show solidarity and share the burden of the refugees. They never directly represented the refugees as threatening the EU. This is because the EP has traditionally been the most sensitive and responsive EU Institution in matters of human rights. The lack of solidarity and unwillingness of the refugees’ burden sharing by the side of the member states could lead to the infringement of some of the refugees’ most basic rights. Having prioritized the human rights and the conditions of abode of the refugees, it is not surprising that the EP’s officials did not represent the migrants as security threats and did not use intense securitizing wording.

The differences in the securitization narratives’ intensity of the main EU Institutions indicate that each one of them perceived differently the refugee crisis. In this process of recursive interaction and collective securitization, the EU Institutions fulfilled simultaneously the role of the securitizing actors and securitization audience. Concurrently, they designed, uttered, and legitimized the securitizing discourse. But to proceed with the legitimation of the discourse and the transformation of the already existing restrictive migration policies, all the main EU Institutions needed to be persuaded. The Commission needed to persuade the Council, EU Council (in effect the governments of the member states) and the MEPs in order to materialize the proposed by it measures. The European Council needed to convince the EU Institutions holding policymaking powers in order to project and materialize the endorsed solutions. The EP had to sway the member states, Council, and Commission that its human security rhetoric had to be accepted in order to keep representing itself as the guarantor of the refugees’ human rights.

In this context of competing perspectives about the referred object of security and caliber of the security threat it was inevitable that the negotiations for a common interinstitutional approach toward the refugee crisis to be burdensome and complicated as the EU Institutions competed for power in the issue of immigration. Against all odds, the EU managed to coordinate and rapidly produce policy instruments to deal with the refugee crisis. Although there was a clash of perspectives about what constituted a threat to the EU, the main EU institutions agreed that the refugee crisis was a threat to the survival of the EU. For some, the threat to the EU was posed by the inability of the EU to stand firm in its position as the guarantor of human rights and protector of persecuted individuals or groups of individuals. An EU unable to guarantee the rights of refugees would no longer be considered as a normative power. For some others, the way the refugees outbreak posed a threat to the process of European integration, was by triggering the reintroduction of internal border-controls between EU member states. The introduction of the border-checks directly violated the internal market rules of the EU and the Schengen agreement. If border-checks would be reintroduced and remained in force, then voices in favor of the EU’s dissolution would be multiplied. For some last, the lack of solidarity among the member states in dealing with the refugee crisis was existential. There would be no reason for creating a European Union if the member states would not be able to assist and support each other in times of major crises like the refugees’ outbreak. Despite the different EU Institutions’ perspectives about the nature and caliber of the risk, they all agreed that the refugee crisis could develop into a risk to the EU’s survival. This made it possible for the EU Institutions and member states to act rapidly and – arguably-effectively to deal with the refugee crisis and the asylum seekers.

Lastly, it appears that the variation of the securitization intensity did not have a dramatic impact on the capacity of the securitizing actors to persuade their audiences. As mentioned above, both empowering/legitimizing and attentive audiences did not resist or developed a counter-securitizing narrative to that of the securitizing actors. This shows that despite the variation of the securitizing narratives intensity among the three main EU Institutions, the rhetoric of all three was accepted by their targeted audiences, the European public and the other EU Institutions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Avramopoulos, D. (2015). Keynote speech of commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos at the first European migration forum. European Commission press release SPEECH/15/3781, 27 January. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-15-3781_en.htm (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Baele, S. J., and Sterck, O. C. (2015). Diagnosing the securitization of immigration at EU level: a new method for stronger empirical claims. Polit. Stud. 6, 1120–1139. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12147

Baele, S. J., and Thompson, C. P. (2017). An experimental agenda for securitization theory. Int. Stud. Rev. 19, 646–666. doi: 10.1093/isr/vix014

Balzacq, T. (2011). “A theory of securitization: origins, Core assumptions, and variants” in Securitization theory: how security problems emerge and dissolve. ed. T. Balzacq (Abingdon and New York: Routledge), 1–30.

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., and de Wilde, J. (Eds.) (1998). Security: a new framework for analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Ceccorulli, M. (2019). Back to Schengen: the collective securitization of the EU free-border area. West Eur. Polit. 42, 302–322. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1510196

Cory, O. (2012). Securitization and “Riskification”: second-order security and the politics of climate change. Millennium 40, 253–258. doi: 10.1177/0305829811419444

Côté, A. (2016). Agents without agency: assessing the role of the audience in securitization theory. Secur. Dialogue 47, 541–558. doi: 10.1177/0967010616672150

Council of the European Union. (2016). European border and coast guard: council confirms agreement with parliament. Press release, 22 June. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/06/22/border-and-coast-guard/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Dagi, D. (2017). Refugee crisis in Europe (2015-2016): the clash of intergovernmental and supranational perspectives. Int. J. Soc. Sci. VI, 1–8. doi: 10.20472/SS2017.6.1.001

Deighton, B., and Roberts, J. (2016). EU targets migration with 2017 research budget. Horizon, 27 July. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/eu-targets-migration-2017-research-budget (Accessed May 20, 2024).

European Commission. (2015). Standard Eurobarometer 83. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/STANDARD/surveyKy/2099 (Accessed May 20, 2024).

European Commission. (2016). Standard Eurobarometer 86. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/STANDARD/surveyKy/2137 (Accessed May 20, 2024).

European Council. (2016). EU-Turkey statement, 18 March 2016, press release. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

European Parliament. (2016). MEPs back plans to pool policing of EU external borders. Press release, 6 July. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20160701IPR34480/meps-back-plans-to-pool-policing-of-eu-external-borders (Accessed May 20, 2024).

European Parliament. (2018). Budgetary affairs: EU funds for migration, asylum and integration policies. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2016/572682/IPOL_IDA%282016%29572682_EN.pdf (Accessed May 20, 2024).

European Union. (2012). Consolidated version of the treaty on the functioning of the European Union [TFEU]. OJ C326/47. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT:en:PDF (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Floyd, R. (2019). Collective securitization in the EU: normative dimensions. West Eur. Polit. 42, 391–412. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1510200

Floyd, R. (2020). Securitization and the function of functional actors. Crit. Stud. Secur. 9, 81–97. doi: 10.1080/21624887.2020.1827590

Guirandon, V. (2010). “The constitution of a European migration policy domain: a political sociology approach” in Studies in international migration and immigrant incorporation. eds. M. Matiniello and J. Rath (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press).

Hintjens, H. (2019). Failed securitisation moves during the 2015 ‘migration crisis’. Int. Migr. 57, 181–196. doi: 10.1111/imig.12588

Juncker, J.-C. (2015a). Managing the refugee crisis: remarks by president Juncker. European Commission press release SPEECH/15/5702, 23 September. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-15-5702_en.htm (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Juncker, J.-C. (2015b). President Juncker: “use budget to solve refugee crisis”. European Commission press release AC/16/1879, 22 September. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_AC-16-1879_en.htm (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Juncker, J.-C. (2015c). Speech by president Juncker at the EP plenary–preparation of the European council meeting of 17–18 December 2015. European Commission press release SPEECH/15/6346, 16 December. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-15-6346_en.htm (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Juncker, J.-C. (2015d). Speech by president Juncker at the plenary session of the European Parliament on the attacks in Paris. European Commission press release SPEECH/15/6168, 25 November. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-15-6168_fr.htm (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Karyotis, G., and Patrikios, S. (2010). Religion, securitization and anti-immigration attitudes: the case of Greece. J. Peace Res. 47, 43–57. doi: 10.1177/0022343309350021

Kaunert, C. (2009). Liberty versus security? EU asylum policy and the European Commission. J. Contemp. Eur. Res. 5, 148–170. doi: 10.30950/jcer.v5i2.172

Kaunert, C., Callander, B., and Léonard, S. (2021). The collective securitization of Aviation in the European Union through association with terrorism. Global Affairs 7, 669–686. doi: 10.1080/23340460.2021.2002099

Kyenge, C. (2015). “Migrant emergency caused by the lack of a common EU policy”, says EP rapporteur and S & D MEP Cécile Kyenge. Social and Democrats press release, 14 April. Available at: https://www.socialistsanddemocrats.eu/newsroom/migrant-emergency-caused-lack-common-eu-policy-says-ep-rapporteur-and-sd-mep-cecile-0 (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Léonard, S., and Kaunert, C. (2010). “Reconceptualizing the audience in securitization theory” in Securitization theory: how security problems emerge and dissolve. ed. T. Balzacq (London: Routledge), 57–76.

Léonard, S., and Kaunert, C. (2019). Refugees, security and the European Union. New York: Routledge.

Léonard, S., and Kaunert, C. (2020). The securitization of migration in the European Union: Frontex and its evolving security practices. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 48, 1417–1429.

Lucarelli, S. (2019). The EU as a securitizing agent? Testing the model, advancing the literature. West Eur. Polit. 42, 413–436. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1510201

Maricut, A. (2017). Different narratives, one area without internal Frontiers: why EU institutions cannot agree on the refugee crisis. Natl. Ident. 19, 161–177. doi: 10.1080/14608944.2016.1256982

McDonald, M. (2008). Securitization and the construction of security. Eur. J. Int. Rel. 14, 563–587. doi: 10.1177/1354066108097553

Moreno-Lax, V. (2018). The EU humanitarian border and the securitization of human rights: the “rescue-through-interdiction/rescue-without-protection” paradigm. J. Common Mark. Stud. 56, 119–140. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12651

Murphy, M. P. A. (2020). The securitization audience in theological-political perspective: Giorgio Agamben, doxological acclamations, and paraconsistent logic. Int. Relat. 34, 67–83. doi: 10.1177/0047117819842330

Panebianco, S. (2021). Towards a human and humane approach? The EU discourse on migration amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Int. Spect. 56, 19–37. doi: 10.1080/03932729.2021.1902650

Pew Research Center. (2015). Many in EU want less immigration. 23 April. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/04/24/refugees-stream-into-europe-where-they-are-not-welcomed-with-open-arms/ft_15-04-22_eu-immigration/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Pew Research Center. (2016). Majorities in several EU countries support taking in refugees. 18 September. Available at: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/19/a-majority-of-europeans-favor-taking-in-refugees-but-most-disapprove-of-eus-handling-of-the-issue/ft_18-09-19_attitudesrefugees_majoritiesinseveral_4/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Pew Research Center. (2017). Across much of Europe, ISIS is top concern. 27 July. Available at: http://www.pewglobal.org/2017/08/01/globally-people-point-to-isis-and-climate-change-as-leading-security-threats/pg_2017-08-01_global-threats_03/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Pittella, G. (2015). Pittella: common migration and asylum policy is the only way to save Europe from disintegration. Social and democrats press release, 14 September. Available at: https://www.socialistsanddemocrats.eu/newsroom/pittella-common-migration-and-asylum-policy-only-way-save-europe-disintegration (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Pittella, G. (2017). Pittella: S & D Group urges Tusk to call before summer break an extraordinary EU Council summit on migration. Waiting until October it would be outrageous. Social and democrats press release, 12 July. Available at: https://www.socialistsanddemocrats.eu/newsroom/pittella-sd-group-urges-tusk-call-summer-break-extraordinary-eu-council-summit-migration (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Roe, P. (2008). Actor, audience(s) and emergency measures: securitization and the UK’s decision to invade Iraq. Secur. Dialogue 39, 615–635. doi: 10.1177/0967010608098212

Salter, M. B. (2011). “When securitization fails: the hard case of counter-terrorism Programmes” in Securitization theory: how security problems emerge and dissolve. ed. T. Balzacq (Abingdon and New York: Routledge), 116–132.

Schulz, M. (2015a). European council meeting-speech by Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament. European Parliament Speech, 15 October. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/former_ep_presidents/president-schulz-2014-2016/en/press-room/european_council_meeting_-_speech_by_martin_schulz__president_of_the_european_parliament.html (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Schulz, M. (2015b). Schulz for renewal of refugee and migration policies. European Parliament press release, 19 April. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/former_ep_presidents/president-schulz-2014-2016/en/press-room/schulz_for_renewal_of_refugee_and_migration_policies.html (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Schulz, M. (2015c). Schulz on the latest tragedy in the Mediterranean. European Parliament press release, 15 April. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/former_ep_presidents/president-schulz-2014-2016/en/press-room/schulz_on_the_latest_tragedy_in_the_mediterranean.html (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Schulz, M. (2015d). Speech at the European council meeting in Brussels. European Parliament Speech, 25 June. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/former_ep_presidents/president-schulz-2014-2016/en/press-room/speech_at_the_european_council_meeting_in_brussels.html (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Schulz, M. (2015e). Speech at the informal meeting of heads of state and government. European Parliament Speech, 23 September. Available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/former_ep_presidents/president-schulz-2014-2016/en/press-room/speech_at_the_informal_meeting_of_heads_of_state_and_government.html (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Sliwinski, K. (2016). A-securitization’ of immigration policy-the case of European Union. Asia-Pacific J. Stud. 14, 25–56.

Sperling, J., and Webber, M. (2017). NATO and the Ukraine crisis: collective securitization. Eur. J. Int. Secur. 2, 19–46. doi: 10.1017/eis.2016.17

Sperling, J., and Webber, M. (2019). The European Union: security governance and collective securitization. West Eur. Polit. 42, 228–260. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2018.1510193

Stivas, D. (2023). Greece’s response to the European refugee crisis: a tale of two securitizations. Mediterr. Polit. 28, 49–72. doi: 10.1080/13629395.2021.1902198

Timmermans, F. (2015). First vice-president Frans Timmermans' introductory remarks at the commission press conference. European Commission press release SPEECH/15/4985, 13 May. Available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-15-4985_en.htm (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Tusk, D. (2015a). Address by President Donald Tusk at die Europa-Rede, Berlin. European Council press release, 10 November. Available at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/11/10/tusk-speech-europa-rede/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Tusk, D. (2015b). Address by President Donald Tusk at the annual EU Ambassadors' conference. European Council press release, 3 September. Available at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/09/03/tusk-conference-eu-ambassadors/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Tusk, D. (2015c). Address by President Donald Tusk to the European Parliament on the informal meeting of heads of state or government of 23 September 2015. European Council press release, 6 October. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/10/06/tusk-address-european-parliament-informal-euco-september/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Tusk, D. (2015d). Address by President Donald Tusk to the European Parliament on the latest European council of 15 October 2015. European Council press release, 27 October. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/10/27/pec-speech-ep/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Tusk, D. (2015e). Doorstep remarks by President Donald Tusk before the informal meeting of heads of state or government. European Council press release, 23 September. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/09/23/pec-tusk-doorstep/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Tusk, D. (2015f). Remarks by President Donald Tusk after the informal meeting of heads of state or government, 23/09/2015. European Council press release, 24 September. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/09/24/pec-remarks/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Tusk, D. (2015g). Remarks by President Donald Tusk following the first session of the European council meeting. European Council press release, 26 June. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/06/26/tusk-remarks-first-press-conference/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Tusk, D. (2016). Address by President Donald Tusk to the Committee of the Regions. European Council press release, 10 February. Available at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/02/10/tusk-address-cor/ (Accessed May 20, 2024).

Van Rythoven, E. (2020). The securitization dilemma. J. Global Secur. Stud. 5, 478–493. doi: 10.1093/jogss/ogz028

Vaughn, J. (2009). The unlikely Securitizer: humanitarian organizations and the securitization of indistinctiveness. Secur. Dialogue 40, 263–285. doi: 10.1177/0967010609336194

Wæver, O. (1995). “Securitization and desecuritization” in On security. ed. R. D. Lipschutz (New York: Columbia University Press), 46–86.

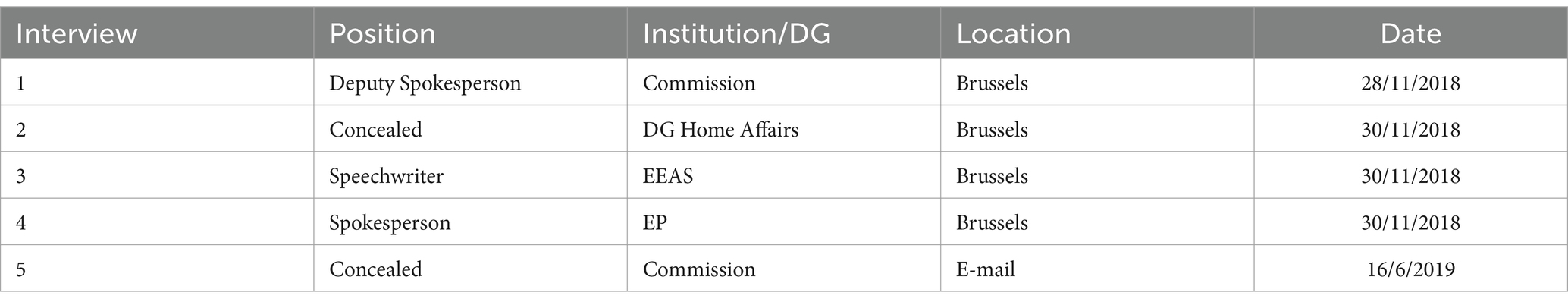

Appendix: Interviews cited

Keywords: securitization, refugee crisis, migration, European Union, narratives

Citation: Stivas D (2024) Variations in the intensity of the securitization narratives at the EU level: securitizing the European refugee crisis. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1460531. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1460531

Edited by:

Georgia Dimari, University of Crete, GreeceReviewed by:

Nikos Papadakis, University of Crete, GreeceStylianos Ioannis Tzagkarakis, University of Crete, Greece

Copyright © 2024 Stivas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dionysios Stivas, ZGlvbnlzaW9zLnN0aXZhc0B4anRsdS5lZHUuY24=

Dionysios Stivas

Dionysios Stivas