- Department of History, Detroit Country Day School, Beverly Hills, CA, United States

Major wars or battles, political revolutions, scientific breakthroughs, or profound social changes often constitute substantial historical turning points. The nineteenth century was a period of intense struggle for America, wrestling with its identity and unity, the quest for emancipation, and conflicts with Mexico. Amid these turbulent times, an initially inconspicuous essay, “Civil Disobedience,” penned in 1849 by a then-unknown Henry David Thoreau, proved to be a turning point that eventually changed the world. The essay provided the framework for a conscience-driven protest, which, when applied on a mass scale, gave the world an effective and non-violent method of war. The power of the voice rooted in conscience and courage, an approach sans violence, inspired “successful” movements across cultures, countries, and time. The essay Civil Disobedience laid the foundation for a conscience-driven, non-violent struggle against injustices that changed the course of human history and remains the best hope for fighting injustices in the future. While less recognized in the annals of popular culture than the political machinations of Machiavelli or the strategic doctrines of Sun Tzu, Thoreau’s essay on civil disobedience has wielded a far more profound influence. In a world still riven by conflict and injustice, Thoreau’s 1849 essay offered the most impactful turning point in humanity’s struggle against injustice. It remains as compelling as ever, offering a blueprint for confronting tyranny not with arms but with the power of human conscience. It serves as a reminder that revolutionary changes sometimes begin with the quietest voice.

Introduction

On April 6, 1930, The New York Times reported a crisp Associated Press cable: “Mahatma Gandhi manufactured salt from seawater at Dandi this morning, thereby breaking the British law establishing a monopoly on salt manufacture” (see Figure 1; The New York Times, 1930; Mahatma Gandhi Walking to Shoreline during Salt Protest, 2024). This act of rebellion marked the commencement of a mass civil disobedience campaign in India, ultimately contributing to the British Empire’s downfall in 1947. This event not only signaled the end of centuries of British dominion but also inspired a wave of non-violent movements and revolutions worldwide over the next century and a half. History is often shaped by singular incidents or anecdotes that precipitate revolutions, wars, or inventions, transforming societies for generations. The foundation for Gandhi’s march and the backbone of many subsequent non-violent movements can be traced back to a century earlier and thousands of miles away in the United States (Sinha and Mitra, 2011). In 1849, in the town of Concord, Massachusetts, a then-obscure writer named Henry David Thoreau published a short essay titled “On the Duty of Civil Disobedience” (shortened to Civil Disobedience in later editions) (see Figure 2; On the Duty of Civil Disobedience, 1849; Gandhi, 1983; Resistance to Civil Government, 1849; Thoreau, 2009; Thoreau, 2019). This essay, advocating for a conscience-driven, non-violent resistance to government injustices, laid the groundwork for twentieth-century movements against colonialism, civil rights abuses, communism, and apartheid, significantly altering the course of history (The New York Times, 1930; Mahatma Gandhi Walking to Shoreline during Salt Protest, 2024). The central tenet of Thoreau’s essay provided a framework and inspiration that continues to influence contemporary movements, demonstrating the power of an idea - an essay - to turn the course of history.

Figure 1. Mahatma Gandhi and some followers marched to the shore at Dandi to break the unjust British salt laws.

Throughout human history, the struggle against oppression has been a recurring theme, often manifesting as violent or armed resistance. However, a different voice emerged in mid-nineteenth century America, advocating for an alternative approach. This voice was that of Henry David Thoreau, an American writer, activist, and environmentalist, whose seminal essay “Civil Disobedience” redefined resistance to government injustices as an act of conscience and courage (Walls, 2017). He presented a novel method of protest that relies on personal integrity and non-violence (Walls, 2017).

While the historical roots of nonviolent resistance can be traced back to the peaceful philosophies of ancient India, including Jain and Buddhist traditions, the secession of the Plebs, and the stoic defiance of early Christians against the Roman Empire, it was Thoreau’s articulation in “Civil Disobedience” that provided a clear blueprint for nonviolent resistance, influencing the course of modern history (Walls, 2017). According to Hegel, history is a dialectic process where the synthesis of opposing ideas fosters new understandings and advancements for humanity (Hegel and Sibree, 2004). Thoreau’s work exemplifies this process, transforming the notion of resistance on its head from a violent struggle to a method of non-violence rooted in conscience (Thoreau and Meltzer, 1963). The context and legacy of “Civil Disobedience” serve as a reminder of the importance of learning from pivotal historical events. By understanding the shifts that have shaped our past, we can better comprehend our present and forge a path toward a more just and peaceful future.

Thoreau and civil disobedience

Thoreau was sui generis, a gadfly of his times. Critics, both during Thoreau’s life and in the years following, often focused more on his personality than his ideas (Walls, 2017; Thoreau and Meltzer, 1963). He lived during the ascent of the Transcendentalist movement, challenging conventional views on religion and society (Schreiner, 2006; Buell, 2006). Known for advocating simple living in his book, “Walden, “Thoreau was far from an isolated figure; he was actively involved in the era’s pressing concerns (Walls, 2017; Richardson and Moser, 1988).

In the tumultuous 1840s and 1850s, the United States grappled with the Mexican-American War, the moral and political implications of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and teetered on the brink of Civil War. Thoreau was a staunch supporter of the anti-slavery movement; he supported radical abolitionist John Brown and the Underground Railroad (Walls, 2017; Richardson and Moser, 1988). He viewed the American war with Mexico as unjust and believed that it would extend slavery’s reach (Walls, 2017). He protested these government policies by not paying taxes for 6 years. He instead courted arrest as an act of defiance and public statement (Walls, 2017; Thoreau and Meltzer, 1963; Richardson and Moser, 1988). When Ralph Waldo Emerson visited him in jail, he questioned, “David, what are you doing there?” Thoreau famously replied, “Ralph, what are you doing out there?”—a moment that epitomized his civil disobedience approach as a conscience-driven resistance against the state (Buell, 2006; Lysaker and Rossi, 2010).

He was released early by his aunt’s intervention, and his incarceration was largely symbolic. He later transformed his reflections on the experience into an essay in 1849, initially titled “Resistance to Civil Government” and later posthumously reprinted as “Civil Disobedience” (On the Duty of Civil Disobedience, 1849; Resistance to Civil Government, 1849; Walls, 2017). The essay represented his joie de guerre against tyranny. It was a call for resistance unlike any before, urging resistance through conscience and non-violent disobedience. The words, “How does it become a man to behave toward this American government today?” remain relevant today (The New York Times, 1930; Walls, 2017; Thoreau and Meltzer, 1963; Richardson and Moser, 1988). Filled with candid dissent, the essay was intellectual yet accessible, though it did not gain immediate impact. It remained a minor ripple in New England’s history until 1907 when Mahatma Gandhi discovered it and integrated its principles into his struggle against colonialism (Gandhi, 1983). From then on, it cemented its place as a significant turning point in history that laid the foundation of global movements against injustice.

Civil disobedience and Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement

Thoreau’s singular essay on Civil Disobedience provided the intellectual backbone for the iconic nonviolent resistance movements that shaped the world in the last century and a half. Gandhi discovered Thoreau’s essay in 1907 as he was building his nascent methods of protest against the British colonial government in South Africa (Gandhi, 1983; Plato et al., 2012). He first experimented and corresponded with Leo Tolstoy during his struggle in South Africa. While in India, he molded and perfected Thoreau’s principles of civil disobedience into a mass movement called “Satyagraha” to fight against British colonial rule (Sinha and Mitra, 2011; Gandhi, 1983). The world outside India saw and heard firsthand about the power of Thoreau’s essay when it was applied on a mass scale during the Dandi Salt in April 1930 (see Figure 1; Mahatma Gandhi Walking to Shoreline during Salt Protest, 2024; Plato et al., 2012). The multiple arrests and jail times that Gandhi courted through his decades-long struggle against British colonial rule in India mirrored Thoreau’s protest in Concord in 1848. Gandhi used a variation of the direct quote from Thoreau’s essay as he was imprisoned following the Dandi March: “For a government which imprisons any unjustly the true place for a just man is also a prison” (Gandhi, 1983).

Gandhi famously remarked, “The only tyrant I accept in this world is the still voice within,” which clearly echoes Thoreau’s emphasis on individual conscience (Gandhi, 1983). Perhaps nowhere is it more explicitly stated than in his own words when Gandhi acknowledged, “I am indebted to Thoreau’s essay on civil disobedience for the formation of my own thoughts on the subject” (Gandhi, 1983).

Gandhi’s legacy of civil disobedience on King and Mandela

Years later, in the 1960s, across the globe, at home in the U.S., Martin Luther King Jr. adopted a Thoreau-inspired, Gandhian strategy of civil disobedience to combat racial segregation (Walls, 2017). King’s nonviolent civil disobedience protests, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Birmingham Campaign in 1963, reflect the principles espoused in Thoreau’s essay, “A State ….would prepare the way for a still more perfect and glorious State, which also I have imagined, but not yet anywhere seen” (The New York Times, 1930). It is vividly demonstrated in King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” that it is a moral imperative to resist unjust laws. King’s own words, “Noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good,” in fighting racial segregation is congruent with Thoreau’s emphasis on conscience to fight against unjust laws of slavery in 1849 (Walls, 2017; King, 2024).

Nelson Mandela is an iconic leader and a global inspiration for his battle against apartheid. Initially, Mandela embraced non-violent methods before shifting to violent resistance (Mandela et al., 2010). However, it was his return to non-violent tactics that ultimately changed the apartheid-torn South African society. Like Gandhi, Mandela’s struggle against a racist regime was girded by personal conscience and moral integrity. Both were lawyers and spent time in the same Johannesburg’s Old Fort prison—Gandhi in 1906 and Mandela in 1962. However, unlike Gandhi, Mandela abandoned his initial non-violent approach to resistance against the apartheid regime and joined the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC) in 1961. “Nonviolent passive resistance is effective as long as your opposition adheres to the same rules as you do,” Mandela stated as a reason for the pivot in resisting apartheid (Mandela et al., 2010). This move toward armed struggle led to his involvement in the Rivonia Trial and subsequent imprisonment in 1964. Mandela’s 27-year incarceration, initially at Robben Island prison, captured the world’s imagination. During his Robben Island incarceration, he read the works of Gandhi, Thoreau, and other classics and recommitted to the power of non-violent disobedience (Mandela et al., 2010). This philosophical shift not only marked his post-incarceration approach and presidency but also influenced the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Committee. Mandela’s embrace of the principles of morality, conscience, and non-violence in combating apartheid and its aftermath is a critical aspect of his legacy. He acknowledged the profound impact of these ideals in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, highlighting the philosophical foundations that guided his leadership.

Impact of civil disobedience in the late twentieth century

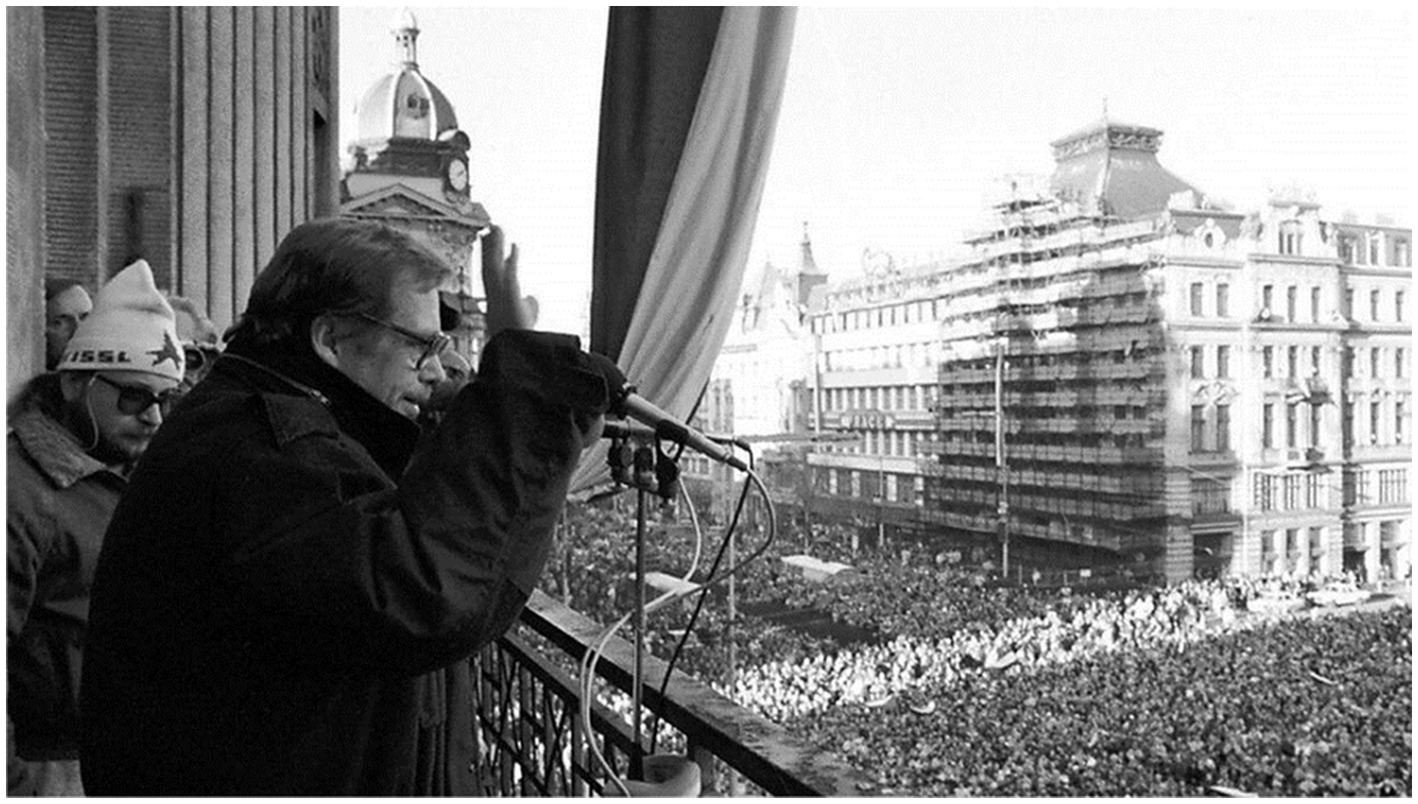

In 1989, Václav Havel successfully led the non-violent Sametová revoluce (Velvet Revolution) against a despotic regime of Communist rulers in Czechoslovakia (see Figure 3; Mitchell, 2012; Prague, 1989). It was based on nonviolence and individual conscience and was inspired by Gandhi’s movement and, ultimately, Thoreau. The Communist rulers repeatedly imprisoned him for decades until he engineered the fall of the regime. The influence of Thoreau’s essay and the principle of individual conscience in civil resistance was articulated in one of Havel’s famous essays, “Politics and Conscience,” from 1984 (Havel and Wilson, 2018). Havel’s quote, “…. While the state is a human creation, human rights are the creation of God,” is a direct variation of Thoreau’s essay when he says, “State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power” (Havel and Wilson, 2018). He made a compelling case for conscience-driven change that comes from the dignified human “I” (Mitchell, 2012; Havel and Wilson, 2018). Havel’s Velvet Revolution was the first of the “Color revolutions,” a series of non-violent government changes that took place in post-Soviet states like Georgia, Ukraine, and Yugoslavia during the early 21st century (Blaisdell, 2016; May, 2015). Thus, the principles for these Color revolutions echo Thoreau’s civil disobedience.

Figure 3. The balcony from which the persecuted civil rights activist and later president Václav Havel spoke to hundreds of thousands on Wenceslas Square in Prague in the autumn of 1989.

Discussion

The reverberations of Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience” extend beyond these iconic figures and into the twentieth-century and the current-century struggles against the iron grip of communism and dictatorships. The movements led by leaders like Lech Walesa in Poland, Aung San Suu Kyi in Myanmar, and the Dalai Lama in Tibet all bear the hallmarks of Thoreau’s civil disobedience (Havel and Wilson, 2018; May, 2015; Chenoweth, 2021). They showed that cooperative action initiated by conscience-driven individuals is a formidable force of change that turns history.

Nonetheless, significant questions remain and are oft debated whether the principle of Thoreau-inspired civil disobedience will work against regimes that are willing to be violent, genocidal, and do not respect fundamental human rights, in other words, like the Nazi regime or brutal dictatorships. Will it be effective in today’s complex, interconnected world with abundant, unverifiable information and short attention spans? Over the past two decades, scholar and social scientist Erica Chenoweth has meticulously researched and analyzed these questions (Chenoweth and Stephan, 2012). She reaches a compelling conclusion: non-violent civil resistance outperforms violent uprisings in the long term, preserving human lives and achieving success. Chenoweth emphasizes that, although Thoreau champions civil disobedience as an individual stance against unjust government, its maximum potential to drive change requires collective, cooperative, coordinated, and sustained effort (Chenoweth and Stephan, 2012).

Furthermore, while Nazi Germany was an extreme situation, Thoreau’s principles succeeded against colonialism, communism, apartheid, and dictatorships. It should be noted that these, too, were brutal regimes and were not some enlightened but misguided governments. In the case of Nazi Germany, the internal resistance attempts against Hitler were small, ill-coordinated, fractured, and primarily involved armed approaches (Hoffmann, 1996). Germany had no large-scale, coherent, and sustained non-violent resistance movements (Chenoweth, 2021; Hoffmann, 1996). However, such non-violent resistance was applied against Nazism successfully, outside of Germany, in Denmark, and Norway, which resulted in the prevention of what might have been mass slaughters (Levine, 2000). Civil disobedience also appears to have failed against the Communist government of China. This was most iconically symbolized by the 1989 June Fourth incident, also known as the Tiananmen Square protests (see Figure 4; Tiananmen Square Agitation, 2024). A similar lack of effectiveness was also seen in the protest against the regime that the Hong Kong Federation of Students led in 2014–2015. The reasons for the failure, Chenoweth contends, are the lack of cohesion, organization, sustenance, and the eventual petering out of the protests in the wake of violent suppression tactics by the regime. She suggests that for a non-violent disobedience movement to succeed, it will require organized and charismatic leadership that is sustained over the years and does not cower in the wake of brutal suppression. Thus, short-term non-violent disobedience may fail even if it is intense and iconic. Her work provides historical evidence that over the long arc of struggles against tyranny, the sustained, coordinated, and large-scale implementation of Thoreau’s principles is more likely to succeed than violent uprisings.

Figure 4. The iconic image of a solitary student protestor standing up against the military might of the Communist dictatorship in China from the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests.

Similarly, can Thoreau’s non-violent civil resistance solve one of the most intractable political issues: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and a war that is raging currently? Historical evidence suggests that Thoreau’s principles may offer the best chance even in the confines and the context of the specific conflict. Historical evidence points to significant progress and optimism following non-violent Palestinian protests (the first intifada) in response to the killing of 17-year-old Mohammed Abu Sisi in 1987, which directly contributed to the Oslo Accord between Rabin and Arafat (Kober, 2014). While the future cannot be known with certainty, the Thoreau-inspired turning point in history might yet offer the best solution if applied sustainably and cooperatively.

Thoreau’s influence extends beyond governmental protest to environmental movements, labor rights, resistance against gun culture, education, and LGBTQ rights, demonstrated by figures such as Greta Thunberg, Cesar Chavez, Sandy Hook parents, Malala Yousafzai, and Harvey Milk, respectively (Chenoweth, 2021). The space constraints limit a detailed discussion of Thoreau’s influence on these movements, but his legacy is undeniably profound.

While political writings often become dated, confined to their specific time and context, Thoreau’s essay transcends these limitations, fostering a timeless dialogue that continues to inspire and adapt to the challenges of new injustices. Thoreau’s essay, which began as a small ripple in 1849, has created lasting reverberations. It represents a significant historical turning point, introducing a revolutionary method to combat the injustice that challenges our evolutionary primal instinct for violence to settle differences. The world emerged as a much better place for that.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Gandhi, M. (1983). Mohandas K. Gandhi autobiography: the story of my experiments with truth. New York, MY: Dover Publications.

Hoffmann, P. (1996). The history of the German resistance 1933–1945: 1933–1945. Montreal: MacGill-Queen's Univ. Press.

King, M. L. . Early draft of the letter from Birmingham jail. Photograph. (2024). Available at: https://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/teagle/files/2022/02/MLK-Letter.jpg (Accessed February 22, 2024).

Kober, A. (2014). Israel's wars of attrition: attrition challenges to democratic states. London: Routledge.

Levine, E. (2000). Darkness over Denmark: the Danish resistance and the Rescue of the Jews. New York: Holiday House.

Lysaker, J. T., and Rossi, W. J. (2010). Emerson and Thoreau: figures of friendship. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Mahatma Gandhi Walking to Shoreline during Salt Protest . Photograph. (2024). Available at: https://static.abplive.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/12123038/gettyimages-514981262-594x594.jpg?impolicy=abp_cdn&imwidth=720.

Mandela, N., Cachalia, C., and Suttner, M. (2010). Long walk to freedom: the autobiography of Nelson Mandela. London: Little, Brown and Company.

On the Duty of Civil Disobedience . (1849). The Project Gutenberg. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/71/71-h/71-h.htm (Accessed February 10, 2024).

Plato, H. D., Thoreau, J. R., Tolstoy, L., Jowett, B., and Garnett, C. E. (2012). Ideas that influenced Gandhi. N.p: Compiled by Dave Chetcuti. Illustrated by Danny Connery.

Prague (1989). Playwrite Václav Havel waves the crowds at Wenceslas Square. Photograph. Available at: https://img.kleinezeitung.at/public/incoming/qsahcp-3809C507-5868-42E5-8A5B-0B84EBC2A19A_v0_h.jpg/alternates/WIDE_1000/3809C507-5868-42E5-8A5B-0B84EBC2A19A_v0_h.jpg.

Resistance to Civil Government . (1849). Internet Archive A print of the original essay civil disobedience, published by Elizabeth Peabody, an acquaintance of Thoreau, has been retrieved and reprinted.

Richardson, R. D., and Moser, B. (1988). Henry Thoreau: a life of the mind. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schreiner, S. A. (2006). The Concord quartet: Alcott, Emerson, Hawthorne, Thoreau, and the friendship that freed the American mind. Hoboken: Wiley.

The New York Times . Gandhi makes salt, defying India's law. (1930). Available at: https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/partners/aol/special/india/300406salt-march.html (Accessed February 18, 2024).

Thoreau, H. D. Civil disobedience. Poets.org. (2019). Available at: https://poets.org/text/civil-disobedience.

Tiananmen Square Agitation . (2024) Photograph. Available at: https://static01.nyt.com/images/2020/06/04/opinion/04baggotc1/04baggotc1-facebookJumbo.jpg?year=2020&h=550&w=1050&s=84f4bc0260baad656d5f8cf097ce24cd8c9875c726192dbf142e40a5912475fe&k=ZQJBKqZ0VN (Accessed March 30, 2024).

Keywords: non-violence, Satyagraha, conflict, Israeli-Palestine conflict, revolution, Nazi

Citation: Reddy S (2024) Thoreau’s civil disobedience from Concord, Massachusetts: global impact. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1458098. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1458098

Edited by:

Bhawna Pokharna, Government Meera Girls College Udaipur, IndiaReviewed by:

Delamar Dutra, Federal University of Santa Catarina, BrazilCopyright © 2024 Reddy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saahith Reddy, UkVEMTUwMUBkY2RzLmVkdQ==

Saahith Reddy

Saahith Reddy