Abstract

Introduction:

The objective of this research is to determine the relationship between the use citizens make of social networks to learn about politics and the emotions expressed towards political leaders, taking as a case study the current Prime Minister of Spain Pedro Sánchez.

Methods:

A quantitative methodological approach was used in this longitudinal study. This approach proposes both a descriptive and multivariate analysis of data from three databases.

Results:

The analysis of results shows important differences between consuming political information on social networks and not doing so in terms of the type of negative emotions (anger and fear) generated towards Pedro Sánchez. Connecting these findings with previous cognitive approaches led us to conclude that, while fear encourages citizens to seek alternative information, when they seek it through social networks the expression of anger increases.

Discussion:

In this sense, preliminary results suggest that fear towards Pedro Sánchez becomes anger when information is proactively sought in social networks.

1 Introduction

Being informed and participating politically in the digital society are two interrelated processes, as meaningful participation cannot be fully understood without being well-informed. In this context, political information obtained through social networks possesses two distinctive characteristics. First, it is uninterrupted and incidental (Williamson, 1998). Second, it is consumed through multiscreens (Giglietto and Selva, 2014). The first characteristic promotes a change in information acquisition patterns. This change is not carried out voluntarily. Firstly, because the algorithmic filtering mechanisms intervene. But also, because the digital community arranges its agenda according to its tastes and preferences. In fact, the consumption of political news on social networks impacts on political participation (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2014; Criado et al., 2013), while its use for entertainment tends to have a negative association. It is worth noting, however, that this consumption predicts online but not offline participation, thus highlighting the importance of differentiating political behaviours in both environments (Shahin et al., 2020). On the other hand, multiscreen consumption, modifies the user experience by also generating a social audience (Quintas-Froufe and González-Neira, 2014) capable of distributing political content.

In addition, each social network is used in remarkably different ways. Thus, while Twitter (now “X”) is mainly used for the dissemination of news and content (Kwak et al., 2010), Facebook is mostly used for mobilisation and the creation of communities (Heredia Ruiz, 2013; Stier et al., 2018). Instagram or YouTube, on their part, disseminate visual or photographic content (Casero-Ripollés, 2018).

Social networks have modified the way citizens consume information. They have also disrupted the emotional spaces related to information and the way political participation is exercised. Indeed, participation is now quite focused on aspects such as cyberactivism or distribution (Casero-Ripollés, 2018), which undoubtedly have important repercussions for the notion of citizenship within democratic political systems.

Given these considerations, the main objective of this paper is therefore to analyse the differences between consumers and non-consumers of political information online and the effect that this may have on their emotional perception of political leadership. Specifically, our empirical analysis focuses on the figure of the current Prime Minister of Spain, Pedro Sánchez. We believe that it is essential to try to understand the emotional influence that politically related consumption of social networks may have had on the perception citizens have of this leadership.

Two are the main reasons that have guided the choice of this case study. First, the current Prime Minister has become in the last few years a political figure with notable domestic and international leadership. We believe, therefore, that it is essential to try to better understand the influence of this leadership and the effects that this influence might have on the behaviour of voters. Second, and in part because of the above, preliminary research has shown that it was precisely this relevance that made him the main target of opposition leaders and parties; and consequently, the focus of citizens’ emotional expressiveness. In this sense, it became apparent that his political figure generated a notable variety of positive and negative emotions, with high percentages of presence and high intensities of emotional expression. Two emotions particularly stood out with negative valence: anger and fear. It was therefore considered appropriate, in view of the literature that will be discussed in the following section, to analyse both emotions in relation to his figure.

We expect that this work significantly will contribute to strengthening with empirical evidence the previous literature that has addressed the study of emotions linked to the study of political behaviour in general, and to the study of behaviour in social networks in particular. Social networks are outlined as highly emotional spaces. Consequently, they tend to produce higher levels of polarisation, which is why they are presented as an ideal space for the analysis and understanding of political behaviour. Likewise, the longitudinal perspective offered by this research, with due regard to the limitations associated with a case study approach, relevantly contributes to the registering of how the emotions citizens express with regard to the figure of a leader change as a function of the different events that mark the political competition.

2 Political information on social networks and emotions

2.1 Information and political participation on social networks

Democracy, in its deliberative dimension, has placed information at the heart of the process of discussion, thus accentuating the relationship between access to information and the quality of democracy. Originally, it could be argued that the quality of the decision depends on the amount of information citizens possess, and, consequently, on the access they have to it at the time of making the decision. But it could also depend on how this information is obtained, to the extent that the vehicle that carries the information to citizens adds cognitive or emotional components that affect the deliberation process. Our approach precisely seeks to address this, namely, to observe which elements of an emotional nature are generated in the access to information based on how it is accessed.

There are three reasons why the consumption of political information on social networks is different from that of traditional media (Bode, 2016): (a) Both the learning process and the degree of activity and passivity vary, especially in low-choice media environments; (b) The agenda-setting effect is lower on social networks or on the Internet as a result of greater exposure to news with fewer impressions; and (c) The proliferation of fake news affects the perception of the credibility of the media and the degree of trust in the political information consumed. This also affects the emotional response.

Moreover, social networks have increased the possibilities for political participation, thus configuring the digital space as a generator of frameworks for organising and conducting collective action with characteristics of their own. One such characteristic, which differentiates it from the offline space, is that the possible participatory actions are carried out jointly (sharing, commenting, discussing, and organising) and because of the consumption of political information. In the offline space however, these actions are carried out separately (intervention in the media, boycotting products, attending demonstrations, donating money, etc.).

The central element of the academic discussion refers to whether technologies have incorporated new clusters of citizens into political participation and the consequences that this has for the functioning of democratic systems, At the same time, a debate has arisen about the type of participation this incorporation would generate. In this regard, some research reinforces the idea that analogue patterns also extend into the digital space, reproducing offline political behaviour (Anduiza et al., 2010; Vissers and Stolle, 2014). In fact, both participations are relevantly and significantly related in several European countries: the more online participation (especially on Facebook), the more analogue participation and the greater the interest in political issues (Bossetta et al., 2018). This could lead us to reflect on the profile of the people who participate. Following the latter authors, the profile of the person who participates in social networks, often a ‘clickactivist’ (Grasso, 2018), is an educated young man (aged between 26 and 35 years), who uses the Internet daily. But it also applies to other older age groups.

The two elements mentioned above, the increase in participation in the networks and the differences between online and offline participation, not only affect to those who participate, but also to those citizens who resort to the social networks to get information, even when they do not intend to participate actively. The latter find in the networks a dialogically constructed space in which participatory information is consumed and debates are generated. For this reason, information and political participation on the web are tendentially linked to the idea of community. This is reinforced, both on Twitter [now ‘X’] and Facebook by the generation of the so-called ‘echo chamber’, which prevents people from consuming information that contradicts their pre-existing beliefs (Bail et al., 2018), while encouraging interaction with other users with similar approaches. This results in a reinforcement of previous ideas and positions. This pattern suggests some sort of polarisation of participation in the social networks, which in recent years has been linked to affection. This cannot be unambiguously conceptualised given that there are important differences between platforms. Thus, while on Twitter [now ‘X’] there is more aggravated polarisation and greater intergroup hostility than on Facebook or WhatsApp (Yarchi et al., 2020); in the case of the YouTube platform, algorithmically recommended content reinforces and polarises political opinions. Indeed, the findings of Cho et al. (2020) suggest that political self-reinforcement based on emotion-ideology alignment and affective polarisation intensifies with continued consumption of political videos on the platform.

2.2 Emotions and social media

From what has been discussed so far, and as some authors have suggested (Kramer et al., 2014; Zollo et al., 2015; Del Vicario et al., 2017), the spaces generated on social networks are emotional spaces. And it is therefore necessary to build bridges in research “suggesting the essential role of emotions in understanding online political behaviour and its consequences” (Wollebæk et al., 2019, p. 2).

The study of emotions and behaviour has initially been linked to the psychophysiological field, especially with the development, among others, of the theory of Affective Intelligence (Marcus et al., 2000) and its incursion into the processes of emotional evaluation. But there have also been approaches from areas linked to sociology and political science (Elster, 2002; Ahmed, 2004) that have shown how emotions are socially constructed through different activation mechanisms. And in this sense, the social definitions of emotions, their exchange, expression and their activation or deactivation have changed with the emergence of the Internet and the development of digital technology (Benski and Fisher, 2013). In fact, the Internet has become a public space for emotional contagion. A place to analyse feelings and an instrument that expresses individual affections or adhesions (Serrano-Puche, 2016).

One of the aspects that has been incorporated into the study of emotions in political science has to do with communication and the way in which information is consumed and processed (MacKuen et al., 2010; Neuman et al., 2018), especially information obtained online. Consuming political information, also on social media, elicits strong emotional responses from citizens. In fact, there is evidence that emotionally charged messages are more commonly shared than neutral messages (Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan, 2013; Bail, 2016; Brady et al., 2017).

With respect to political information on the Internet, emotions take on a mediating role in the process of becoming a politically informed citizen (Valentino et al., 2008). Anxiety generates information seeking attitudes and the need to learn. Anger, in contrast, inhibits it. As to participation, enthusiasm increases interest in electoral campaigns (Marcus et al., 2019; Vasilopoulos et al., 2018a,b). Thus, the relationship between information and emotions is bidirectional. Certain emotions affect the search for information, and at the same time, the consumption of information, in its semantic, cultural, cognitive and evaluative dimensions affects the social construction of emotions (McCarthy, 1994).

These platforms also facilitate the exchange of emotionally charged content either supporting or opposing mobilisation and protest with raging, angry or enthusiastic messages (Jost et al., 2018). In fact, the presence of emotionally charged language in messages increases their potential for dissemination among different digital communities (Brady et al., 2017; Knoll et al., 2020). So much so that the digital sphere is a space in which the process of Emotional Social Sharing takes place (Bazarova et al., 2015; Burke and Develin, 2016). This social and collective construction of emotions has the distinctive characteristics of social networks: they are immediate, personalised and participatory (Jaráiz et al., 2021).

Also, a good number of studies highlight the importance of some specific emotions in the online process, with special attention to fear and anger. These two emotions have different impacts on the way in which users behave politically in this space, either by reinforcing or inhibiting its dynamics. Anger seems to drive people to search for information or to participate in debates with people who have similar points of view. Fear, on the other hand, seems to provoke the opposite reaction (Wollebæk et al., 2019). These two tendencies are indebted to the different mechanisms that activate one emotion or the other. While anger can be attributed to a particular source over which the individual feels he or she is exercising control (Valentino et al., 2011), fear, on the other hand, is the result of feeling a loss of control. This means that while the former (anger) drives risk-taking behaviour, the latter (fear) leads to risk aversion and increased information seeking (Lerner and Keltner, 2001; Valentino et al., 2008; Vasilopoulos et al., 2018a,b).

These findings, in turn, generate important consequences for political systems. Fear and anger have an impact on the understanding citizens have of democracy, and this changed understanding has political implications (Marcus, 2019). With respect to information, those who are afraid are driven to seek new narratives to help them to cope with new threats. Anger generates, however, a resistance to contrary information. Similarly, in certain highly emotional contexts following tragic events, anger strengthens authoritarian preferences, albeit only among right-wing voters. Ideology becomes therefore a determining factor (Vasilopoulos et al., 2018a,b).

The research strategy underpinning this work is based on acknowledging the importance that the literature attaches to two basic political emotions: fear and anger. On the one hand, the literature notes the important role that fear plays in conditioning the search for information (Marcus, 2019) and even the impact that it may have on political participation online (Chen et al., 2017), especially in electoral campaigns. But, on the other hand, it shows the importance of anger in both activating the intention to participate and increasing the factors related to mobilisation (Weber, 2013; Valentino et al., 2011). At the same time, it leads the individual not to seek alternative information but only to reinforce their own position and to reduce the vision of risk in the face of the possibility of action (Marcus, 2019).

However, since Durkheim underscored emotions as a social construction (Fisher and Chon, 1989), many works have reinforced this constructivist reading (Averill, 1980, 1982, 1986; Gordon, 1981, 1989; Gergen, 1985; Harré, 1986; Elster, 2002; Ahmed, 2004), arguing that emotions are indissoluble from the cultural and social space in which they are produced and that it is necessary to understand the historical context and the societies in which they are expressed to understand them to their full social extent (Elster, 2002). And although these readings have sometimes been criticised for being excessively linked to language as a vehicle for the construction of emotions (Aranguren, 2017), all constructivist readings, especially those attached to symbolic interactionism, have emphasised this approach.

Our research investigates to what extent the consumption of political information on social networks, precisely because of the peculiarities of the information produced on them and the way in which the interaction between participants is generated, affects the social construction of two basic political emotions such as fear and anger. Consequently, we approach each of these dimensions individually as variables to be explained in a polarised and changing digital context. This paper is therefore in line with previous studies which, either on the basis of demoscopic studies (Wollebæk et al., 2019; Hasell and Weeks, 2016; Kramer et al., 2014), like in the case of this study, or through sentiment analysis (Del Vicario et al., 2017; Zollo et al., 2015; Tumasjan et al., 2010), have delved into the essential role that emotions play in the construction of online political behaviour as an extension of what has already been analysed in the field of political behaviour as a whole.

3 Objectives, materials and methods

Our main objective in this research is to determine the relationship between the use citizens make of social networks to obtain political information and the emotions expressed towards political leaders. More specifically and for the reasons stated above, we will focus on the figure of the current Spanish Prime Minister and candidate for the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE), Pedro Sánchez.

This objective, in turn, led us to propose two initial research hypotheses:

-

H1: The consumption of information on social networks encourages anger.

-

H2: Fear encourages the search for alternative information: consumers of information in traditional media still retain fear, while those who consume it on social networks will experience anger.

This study was designed following a quantitative methodological approach that proposes both a descriptive and a multivariate analysis of the data. As noted above, the analysis was a case study centred on the figure of the current Prime Minister of Spain, Pedro Sánchez. He was also the PSOE candidate in the general elections held in April and November 2019,1 two of the temporal milestones on which the analysis focused. This longitudinal analysis is completed with an overview of what happened in the year 2021, when the management of the pandemic was still very much present. We consider that the convulsive political-electoral situation that Spain has witnessed in the last 9 years, with the emergence of three new political parties at the national level—in 2015 Ciudadanos and UP, and subsequently, in April 2019, VOX, a far-right party—is the ideal context to address the impact that the emotional component has had on politics and the relations that citizens establish with it. These three moments provide us with an opportunity to observe political behaviour on social networks in two very different situations: in electoral and non-electoral periods. This is enriching in terms of observing differences in the dynamics generated in the interaction on social networks.

To conduct the analysis, we have used data from two post-electoral public opinion surveys carried out by the Equipo de Investigaciones Políticas of the University of Santiago de Compostela (EIP-USC) after the two electoral processes. We have also included a political situation study carried out in 2021. Table 1 shows the technical information relating to these studies. In addition to the usual elements present in a post-electoral study (voter itineraries, analysis of the electoral campaign, …), in the case of the first two studies, other questions of interest for this study here were collected: offline and online media consumption and emotions linked to political actors. The questionnaires were standardised to guarantee the comparability of the data extracted.2

Table 1

| Name of poll | Technical characteristics |

|---|---|

| Post-electoral Survey General Elections in Spain, April 2019 (PESGES Apr. 19) | Dates: from June 12 to July 12th, 2019. Universe: persons aged 18 and over living in Spain. Sample size: 1,000. Assumptions: p = q. Associated error: ±3.1%. Allocation: proportional (strata: sex and age). Mode of survey: telephone survey using the CATI system. |

| Post-electoral Survey General Elections in Spain, November 2019 (PESGES Nov. 2019) | Dates: from January 14 to February 22nd, 2020. Universe: persons aged 18 and over living in Spain. Sample size: 1,000. Assumptions: p = q. Associated error: ±3.1%. Allocation: proportional (strata: sex and age). Mode of survey: telephone survey using the CATI system. |

| Politics and Emotions Survey in Spain. February 2021 (PESS Febr. 2021) | Dates: from January 18 to February 18th, 2021. Universe: persons aged 18 and over living in Spain. Sample size: 1,000. Assumptions: p = q. Associated error: ±3.1%. Allocation: proportional (strata: sex and age). Mode of survey: telephone survey using the CATI system. |

Technical characteristics of opinion polls.

Source: Own preparation.

The central variables selected for the analysis conducted were the following: the use of social networks to stay informed about politics (nominal variable)3 and the presence of emotions expressed towards the political figure of Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez (nominal variable).4 Regarding the first variable and given its centrality in the analysis, we would like to point out that it is part of a series of questions that seek to capture the importance that social networks have in the lives of citizens, and more specifically the use they make of them in political terms. It is, therefore, a set of linked and filtered questions that draw a picture of the use of social networks ranging from greater to lesser intensity and specificity: (a) being or not a regular user of social networks in general; (b) specific social networks used (multiple choice); (c) frequency of use; (d) use of social networks to receive political information and recognised intensity of use; and (e) use of social networks to participate in politics and recognised intensity of use.

Regarding the way in which the measurement of the emotional component was included in these studies, a clarification is in order. The analytical model chosen responds to a long history of research by the EIP-USC in this domain, as well as to the methodological design of different previous measurement instruments. The empirical materialisation of this component is based on a battery of 13 emotions on which three fundamental questions are measured: the presence, intensity and duration of emotional expression towards leaders and political parties.5 Twelve of the 13 emotions analysed correspond to the full set orthogonal solution proposed in the ANES Pilot Study 1995 (Marcus et al., 2000): pride, hope, enthusiasm, anxiety, fear, worry, anger, resentment, disgust, hatred, contempt and bitterness; to which an additional one has been added: calmness.6

In this study, based on the results discussed below and the preceding literature, our focus was on studying the presence of two specific emotions: anger and fear. The reason for this choice is twofold. First, because they are two of the emotions that have had the longest trajectory in the literature, as indicated in the second section. Secondly, because they are two of the emotions of negative valence that tend to have a greater presence in tense political contexts such as the ones we are discussing. Regarding this second issue, it should be pointed out that in addition to the emergence of new political parties, especially a far-right party, which characterised the two electoral processes analysed (one of which was a repetition due to the difficulty of reaching agreements), there is also the management of an unprecedented global health pandemic. We believe that these issues are fundamental to understanding and forming a picture of a tense political and social climate.

To conduct the analysis, in addition to a first descriptive overview based on one- and two-dimensional analysis, several binary logistic regression models were proposed and adjusted to explain the behaviour on social networks of those who feel anger or fear towards the figure of the leader. The choice of this multivariate technique was based on the nature of the dependent variables chosen and whether each emotion was felt or not (emotional presence). These variables, originally proposed as nominal dichotomous variables (Yes/Not), were reconfigured as dummy variables (presence/absence of the specific emotion in each case).

4 Results

4.1 Consumption of social networks for political purposes and emotional presence

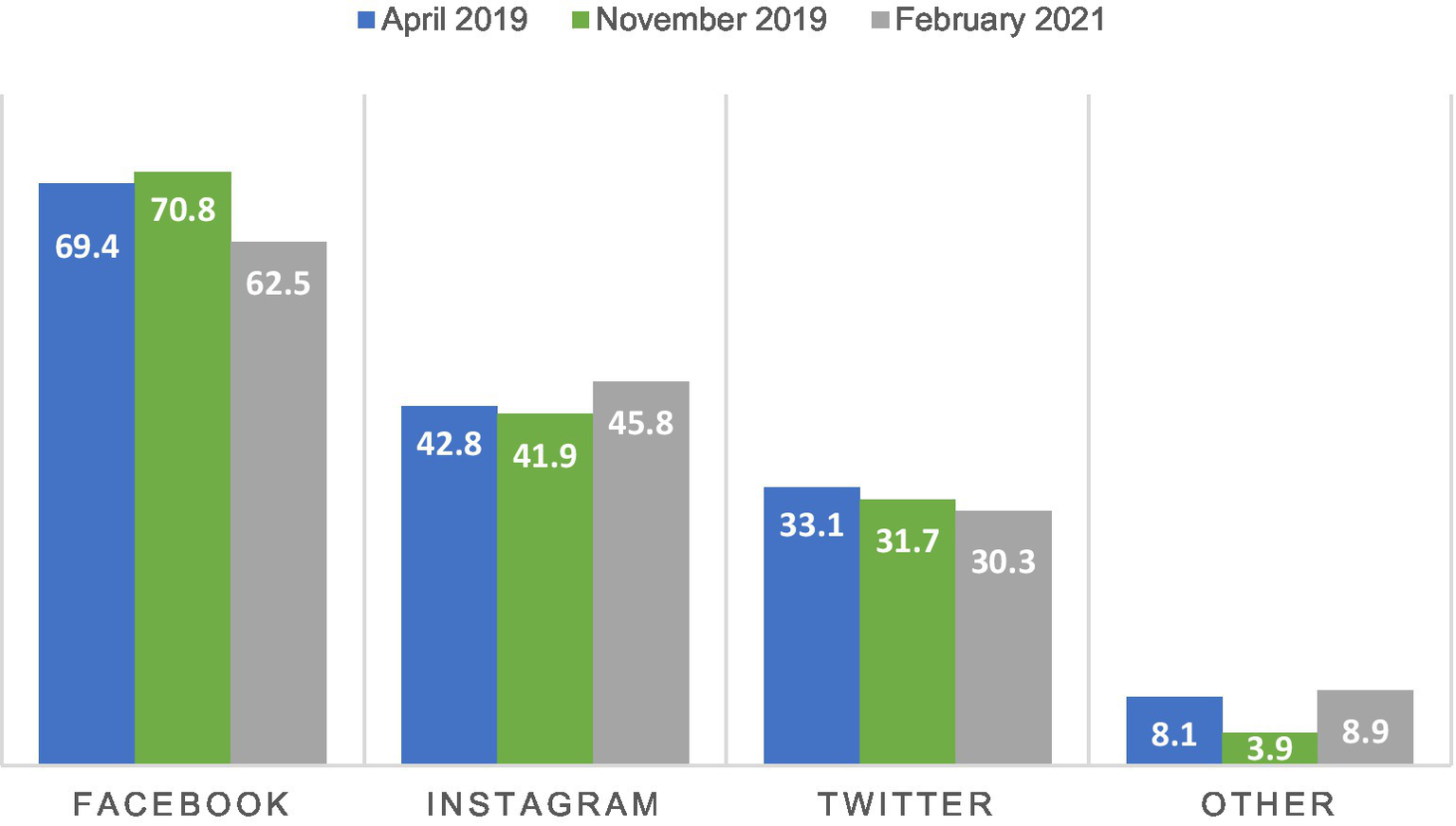

We begin this section by presenting a descriptive analysis (Table 2) that gives us a first snapshot of the basic data on which this research is based. The percentage of respondents who claimed to be regular users of social networks is very similar in the three political moments, ranging from 51.2 to 51.7%. The most used networks were Facebook and Instagram, as shown in Figure 1. Of these percentages, 50% in April 2019, 46.7% in November 2019 and 31.8% in 2021 claimed to use social networks to receive political information with an intensity of use7 of 6.37, 6.8 and 5.8 out of 10, respectively. It is interesting to note that both usage and intensity differ depending on whether the measurement takes place during election time, reinforcing the thesis that election campaigns encourage some citizens to seek more political information.

Table 2

| Variables | April 2019 | November 2019 | February 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular social network user | 51.2% | 52% | 51.7% |

| Use of social networks to inform yourself about politics (variable filtered for those who previously claim to be regular users) | 50% | 46.7% | 31.8% |

| Average intensity of use of social networks to find out about politics (variable filtered for those who previously claim to use social networks to find out about politics) | 6.37 | 6.8 | 5.8 |

General data of social network use.

Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESGES Apr. 2019, PESGES Nov. 2019, and PESS Febr. 2021.

Figure 1

Social network that uses most frequently. *Multiple response question. Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESGES Apr. 2019, PESGES Nov. 2019, and PESS Febr. 2021.

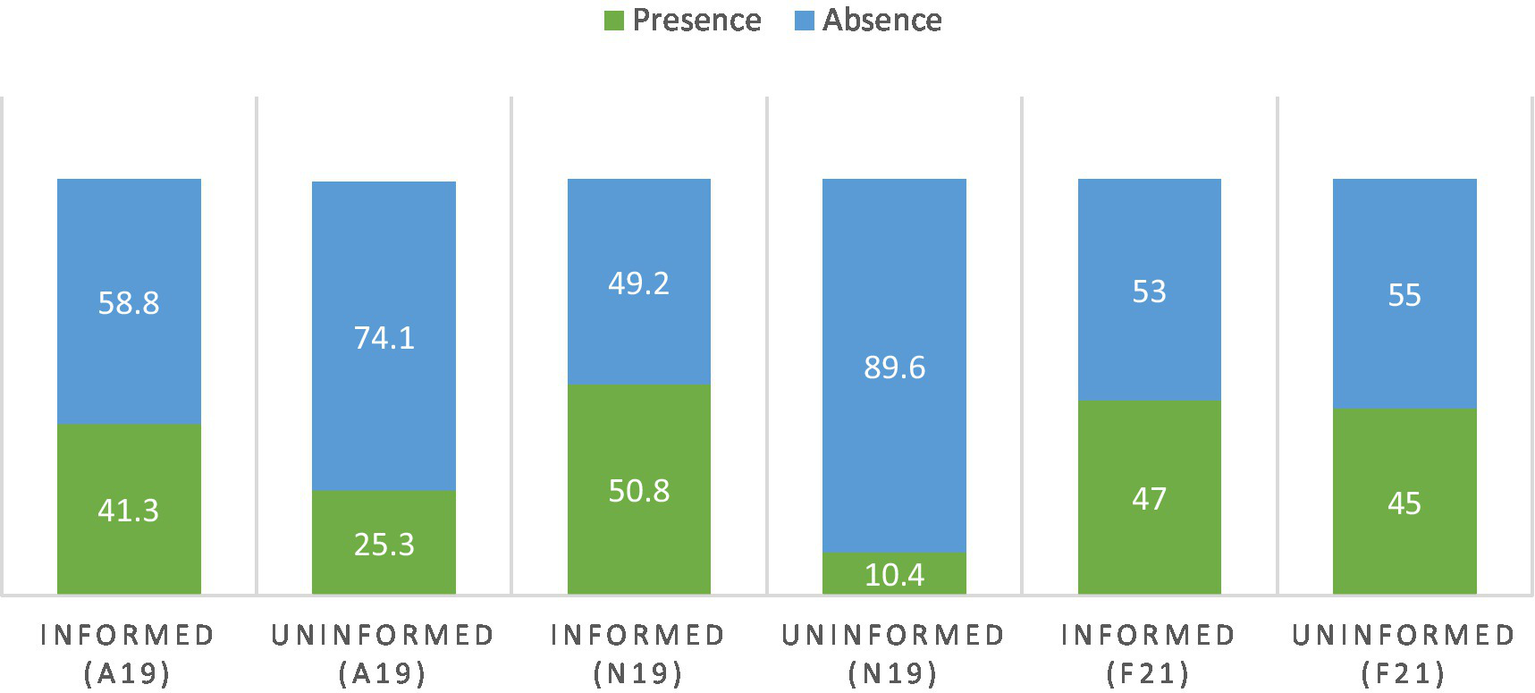

In view of the main objective of this research, we show below (Figure 2), the relationship between the fact of using or not using social networks to stay informed about politics and the presence of anger towards the Prime Minister of Spain, Pedro Sánchez. As can be seen, the presence of this emotion is greater in the three moments analysed among those who claim to consume political information compared to those who do not. The highest percentage corresponds to November 2019 (50.8% for those who inform themselves). This is probably due to the repetition of the elections and the political situation of pacts resulting from the impossibility of forming a government. On the other hand, those who do not get political information via social networks feel substantially less anger towards Pedro Sánchez, with percentages decreasing from April (25.3%) to November (10.4%). In other words, between one election and the next, anger increases among consumers of information on social networks while it significantly decreases among those who do not consume information on social networks. In non-election periods, however, there is hardly any difference between consumers and non-consumers of political information with regards to this emotion.

Figure 2

Presence of anger towards Pedro Sánchez depending on whether/not political information is reported through social networks. Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESGES Apr. 2019, PESGES Nov. 2019, and PESS Febr. 2021.

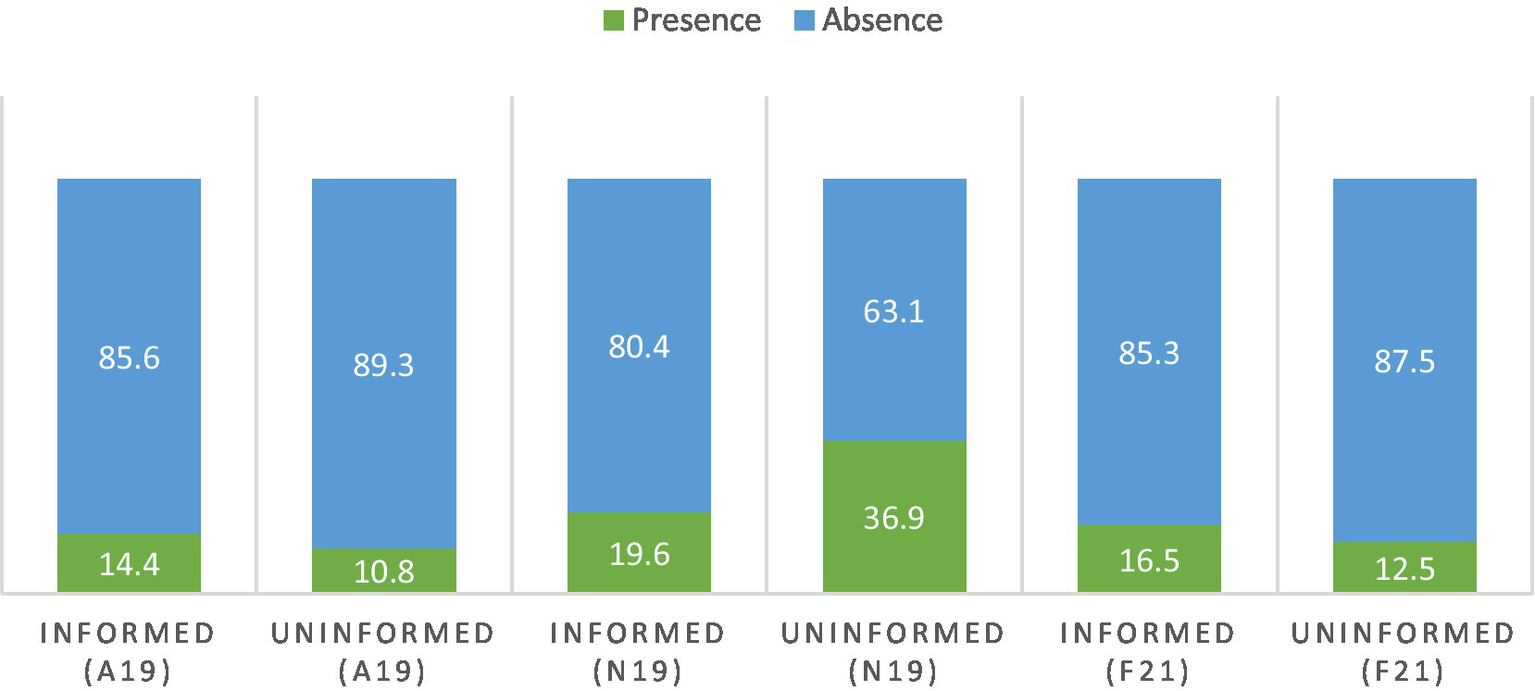

As already mentioned, another central emotion in politics is fear. In Figure 3 we see that the presence of fear towards Pedro Sánchez is much lower, in percentage terms, than that of anger. As to citizens who use social networks for political information, in April, 14.4% of those who use them for this purpose claimed to feel fear, compared to 19.6% in November of the same year and 16.5% in 2021. What is noteworthy is the result of the presence of this emotion for the group that does not use social networks for information. In this case the leap is very notable: from 10.8% in April to 36.9% in November of the same year to fall again to 12.5% in 2021. This fact seems to corroborate that those citizens who are politically informed through social networks and feel fear have controlled or channelled this emotion despite the above variations. In other words, the consumption of information on social networks does not result in an increase in fear or, if it does, it is negligible compared to the percentage increase we can observe among those who do not consume information on social networks (more than twice as much), and who obviously do so through other offline media. And when there is some kind of significant increase, it is usually in response to exceptional political contexts.

Figure 3

Presence of fear towards Pedro Sánchez depending on whether/not political information is reported through social networks. Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESGES Apr. 2019, PESGES Nov. 2019, and PESS Febr. 2021.

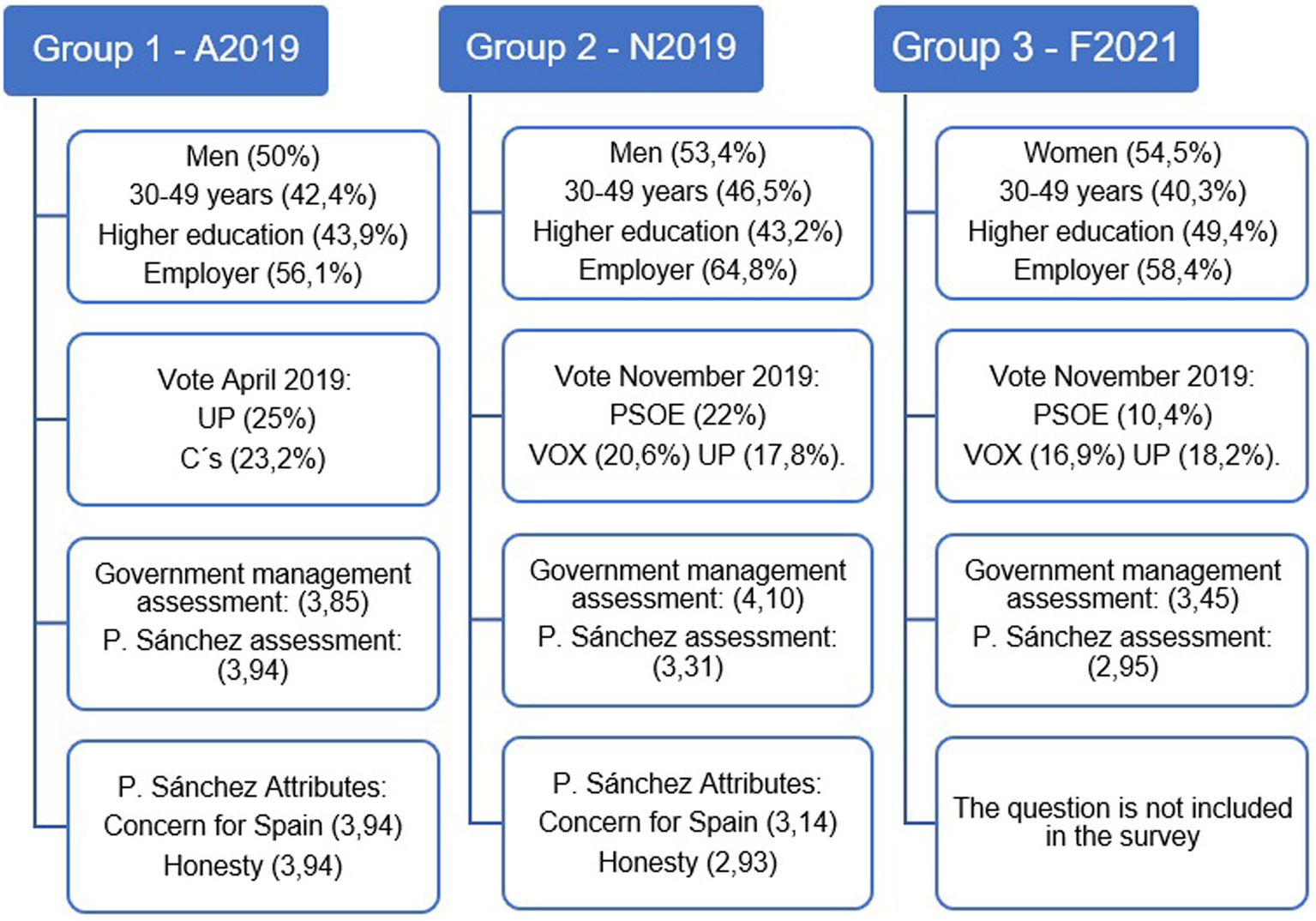

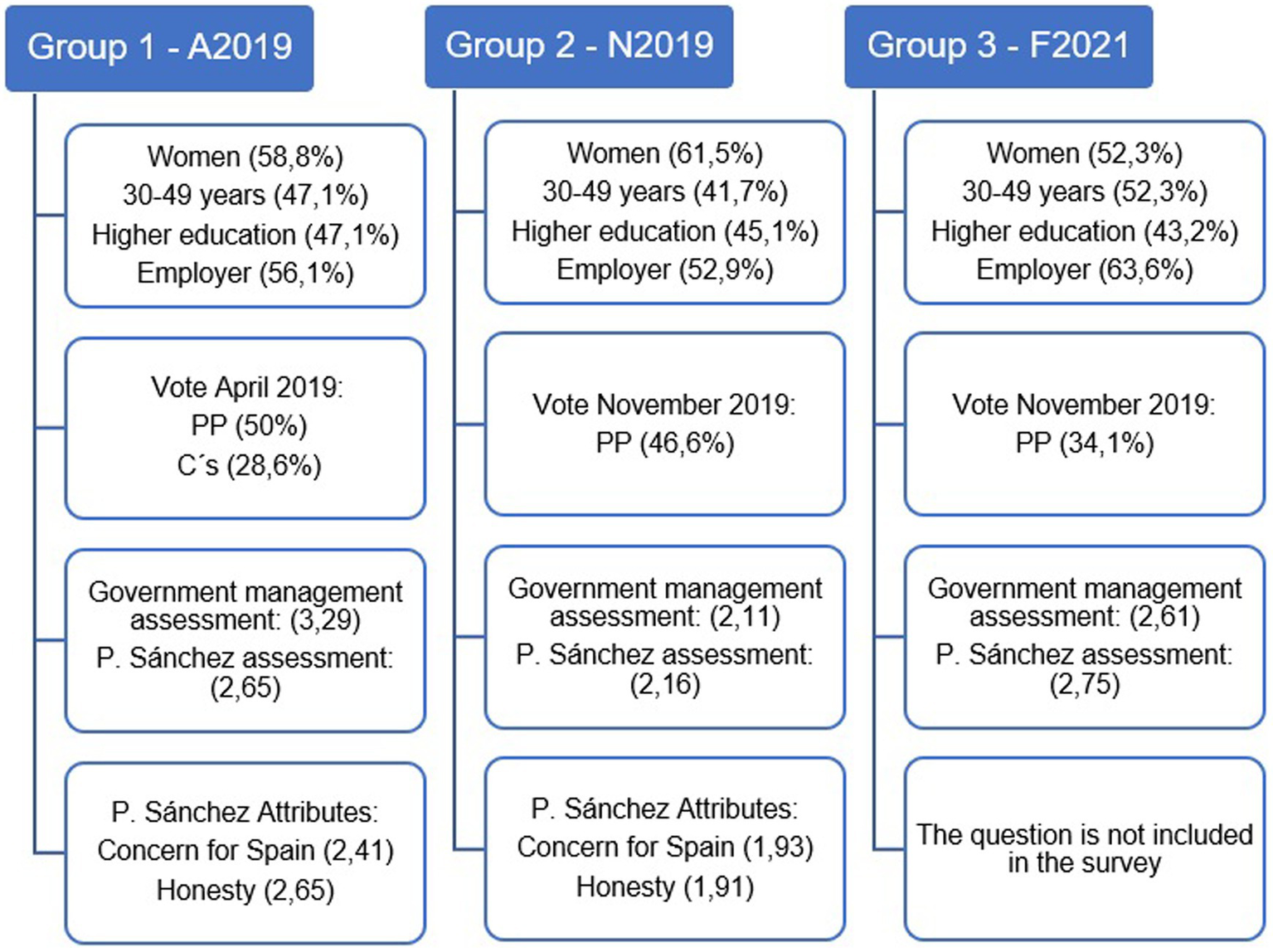

Next, in our analysis is to describe the profiles of those who use social networks for the consumption of political information vs. those who do not use them based on whether they feel anger or fear towards Pedro Sánchez (Figures 4, 5). We carried out a first intra-group approach, working with the same group in all temporal milestones, and subsequently, an inter-group approach comparing the two groups with each other.

Figure 4

Profiles of those who learn about politics through social networks and feel Anger towards Pedro Sánchez in the three moments analysed. Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESGES Apr. 2019, PESGES Nov. 2019, and PESS Febr. 2021.

Figure 5

Profiles of those who do not learn about politics through social networks and feel Fear towards Pedro Sánchez in the three moments analysed. Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESGES Apr. 2019, PESGES Nov. 2019, and PESS Febr. 2021.

The first figure shows the comparison of those who claim to be informed about politics through social networks and feel anger towards Pedro Sánchez at all three time points analysed. As far as socio-demographic variables are concerned, there are hardly any significant differences. We do observe certain differences in relation to the political assessment of the socialist leader and the assessment of his performance as head of the Spanish government,8 with both being slightly lower in 2021. About the assessment of the attributes of the Prime Minister,9 we noted that although the two worst-rated attributes in April and November 2019 were ‘concern for Spain rather than for his party’ and ‘honesty’, both had lower average values in November, especially in the case of the latter.10 The main differences are linked to the composition of the profile based on voting memory. Thus, while in April citizens mainly supported UP and Ciudadanos (in that order), in November and in 2021, their recollection was that their support for PSOE, UP and VOX had been greater. However, the percentage of support for PSOE in 2021 was significantly lower.

Figure 5 shows the profile of those citizens who do not inform themselves about politics through social networks and are afraid of Pedro Sánchez. Like in the previous case, certain similarities can be seen. Again, in socio-demographic terms, there are hardly any significant differences. The evaluation of the leader, his management and the evaluation of his qualities are again notably lower in November. As for the composition according to voting memory, similarities between the three periods can be seen, with the majority giving their support to the Partido Popular (PP).

If, instead, we establish an inter-group comparison, we need first to discuss some issues of interest. In terms of socio-demographic variables, besides the fact that the 30–49 age range predominates in all the groups analysed, it is important to note that the male profile of information consumers expresses the emotion of anger,11 as opposed to the female profile of non-consumers of information on the networks that expresses the emotion of fear. As to the assessment of the Prime Minister’s management, the assessment of his political performance and of his qualities as a leader, we observe a similar pattern among all four groups. So much so that the average values drop significantly between the months of April and November, only to recover again in 2021. A particularly relevant issue is observed in the ratings of the Prime Minister, insofar as those who feel fear always rate him worse than those who feel anger. And this is because fear is always an emotion expressed only by those who vote for others. Anger towards a leader, however, can be felt by both supporters and non-supporters.

4.2 Explanatory analysis of the expression of anger and fear towards Pedro Sánchez by social networks users

Finally, to close the analysis, six binary logistic regression models were carried out, two for each of the three moments analysed. One with the dependent variable “feeling anger” towards Pedro Sánchez and another with the dependent variable “feeling fear” towards him. In the six models, the sample was segmented. Only those who claimed to be users of social network—the central variable from which the itinerary on social networks included in the studies is drawn—were included in the sample. Some of the variables used in the profiles described in section 4.1 were introduced as independent variables: sociodemographic variables (sex, age, level of education, income level); as control variables, ideological self-placement (left–right scale) of the respondent, assessment of the central government’s management, assessment of the Prime Minister’s management, assessment of Pedro Sánchez’s political performance and assessment of his qualities as a leader. Other variables used include intensity of use of offline media (press, radio and television) to obtain political information and level of trust in the political class or level of trust in democratic institutions.

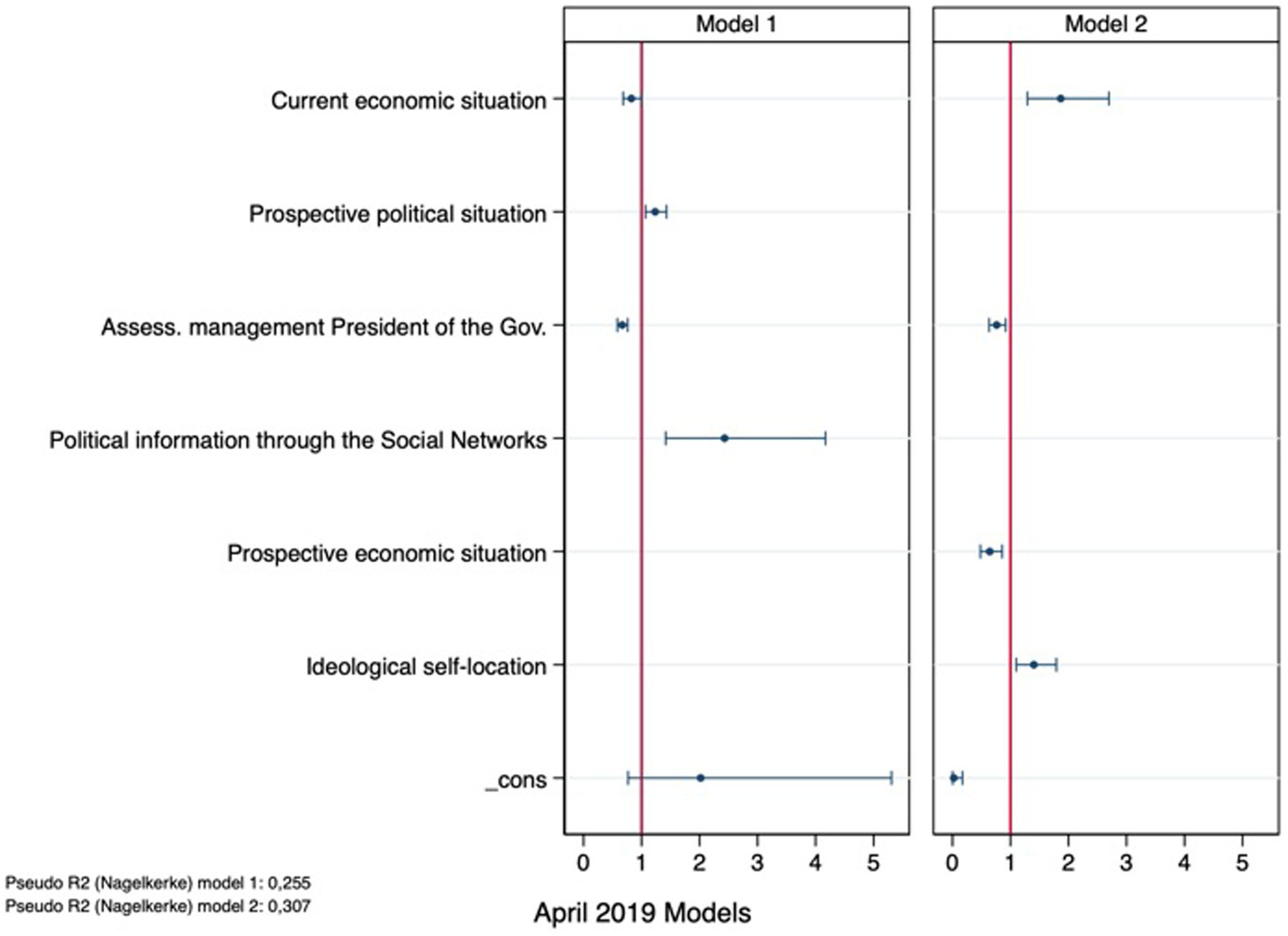

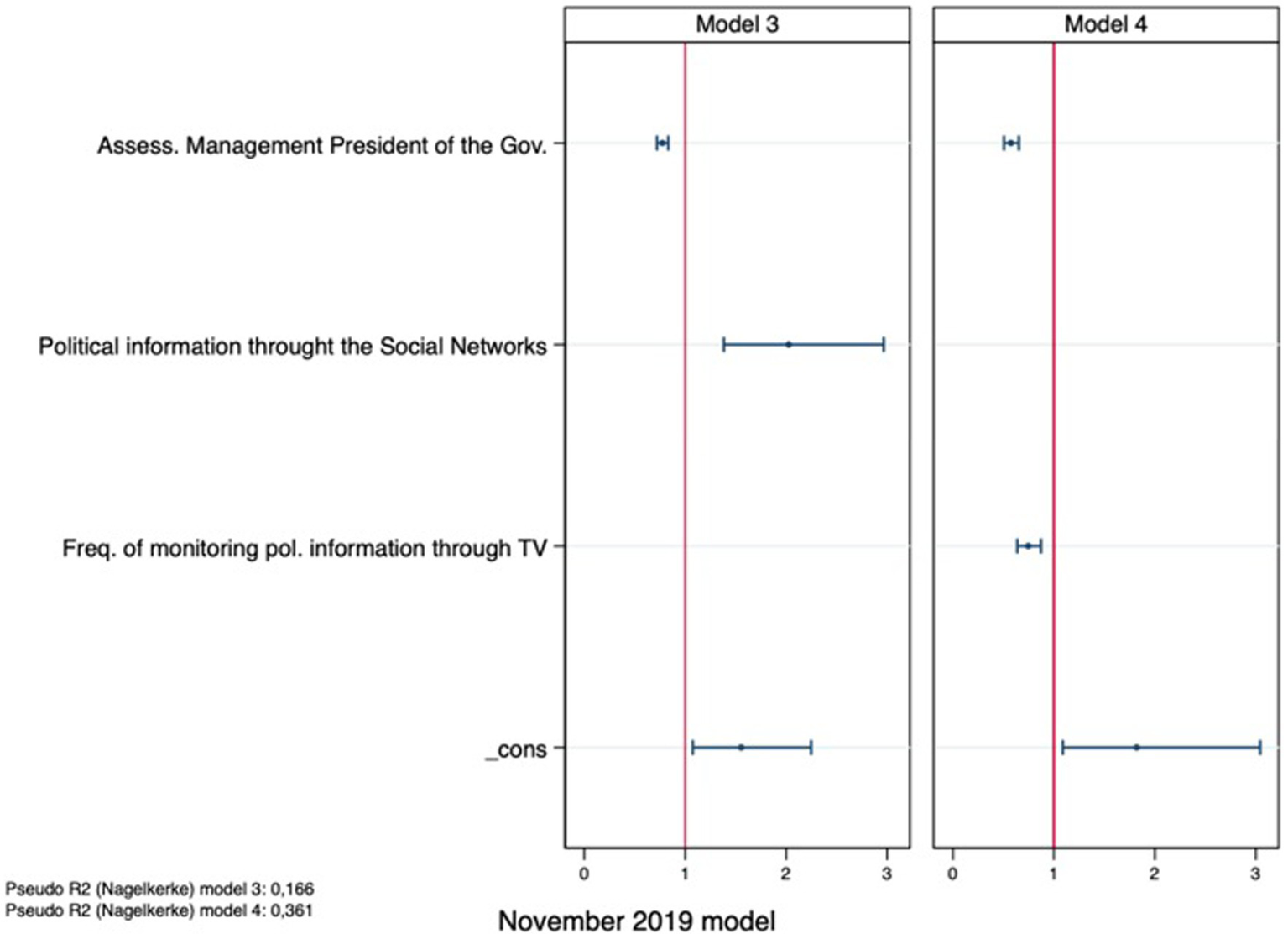

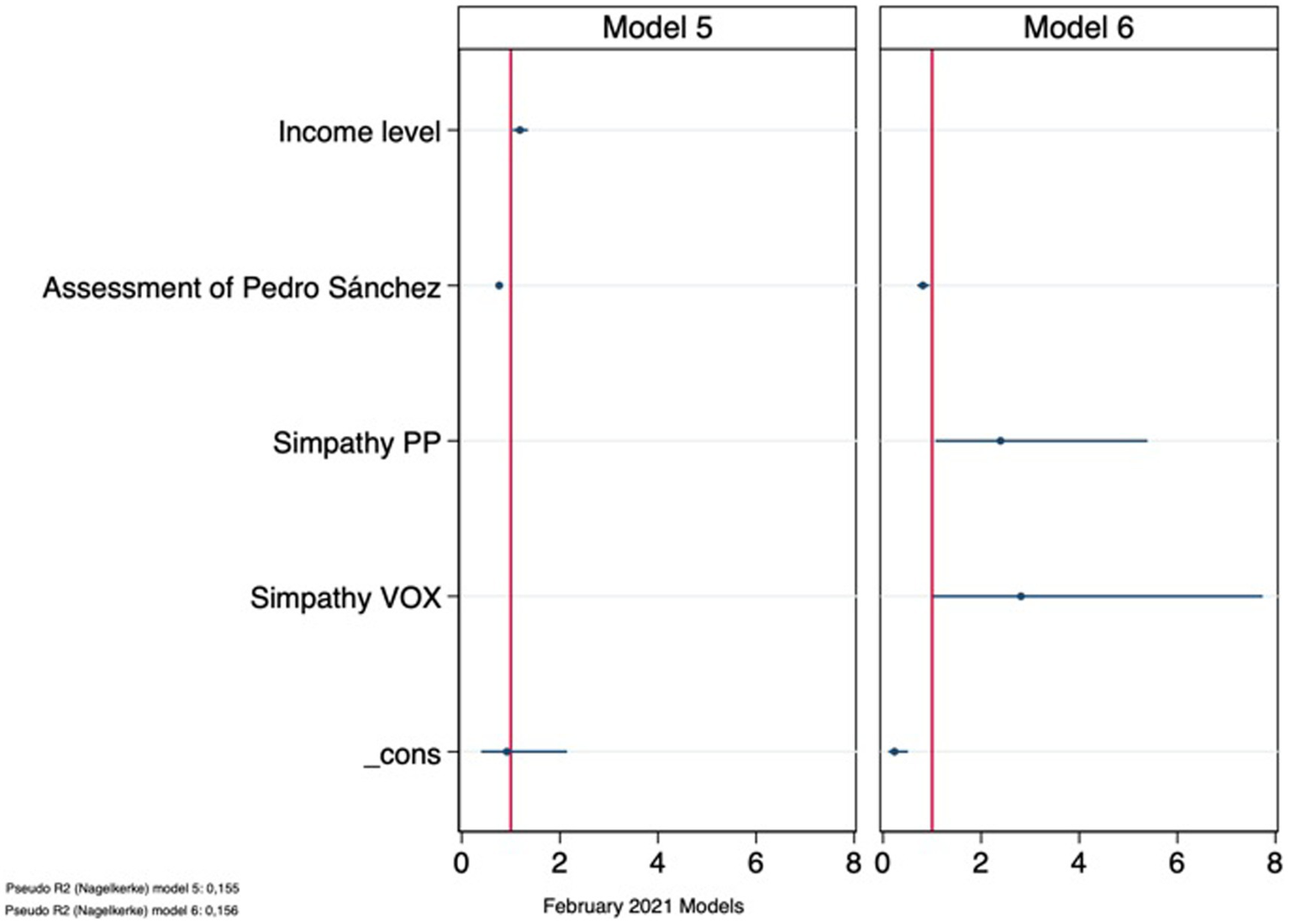

Figures 6–8 show the results of the six models fitted with the explanatory variables that were finally found to be significant after adjustment and statistical specification of the modelling, based on the marginal effects calculated from the exponential values of the beta coefficients of the models. The beta values, their standard errors and the significance levels of the variables included in all the models presented can be consulted in Appendix Table 1.

Figure 6

Coefficient graph [Exp (B)] of the binary logistic regression models of the use of social networks to obtain information about politics in April 2019 (Model 1, DV: Anger; Model 2, DV: Fear), Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESGES Apr. 2019.

Figure 7

Coefficient graph [Exp (B)] of the binary logistic regression models of the use of social networks to obtain information about politics in November 2019 (Model 1, DV: Anger; Model 2, DV: Fear). Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESGES Nov. 2019.

Figure 8

Coefficient graph [Exp (B)] of the binary logistic regression models of the use of social networks to obtain information about politics in February 2021 (Model 1, DV: Anger; Model 2, DV: Fear). Source: Own preparation from data of surveys PESS Febr. 2021.

It is important to note the sparseness of the adjusted models and, therefore, the centralisation of the explanatory potential in a smaller number of variables, which undoubtedly speaks of a greater degree of intra-group compactness. One of the fundamental explanatory variables in the modelling is the assessment of Pedro Sánchez’s performance as head of the Spanish government, which in 2021 is replaced by the assessment of his political performance. These two variables have an inverse relationship in the six scenarios (with greater or lesser impact, see Figure 6) with the two dependent variables (anger or fear, depending on the case); causing, consequently, an increase in the probability of expressing both emotions towards the above leader as the assessment of his performance as head of the Spanish government worsens. In conclusion, it is clear, both in April and November, that the consumption of information on social networks is the variable that shows the greatest explanatory capacity for the feeling of anger towards Pedro Sánchez, confirming a sort of catalytic effect of this emotion. In contrast, in model 4, adjusted for fear, the intensity of the use of television as an element of political information consumption is significant, with the probability of feeling fear increasing as the consumption of this offline medium increases.12 In the models adjusted for 2021, none of these variables proved relevant. This may be due in part to the reduction in media consumption in non-electoral periods.

Regarding the models proposed for the first temporal milestone, April 2019, it is important to note the notable effect of some contextual variables, more specifically, the assessment of the current economic situation in Models 1 and 2, albeit with a different effect in both cases. Thus, while in Model 1, as the assessment of the current economic situation improves, the probability of feeling anger decreases. In the case of Model 2, the effect is the inverse. Also significant in the case of Model 1 is the assessment of the future political situation, increasing the probability of expressing anger, and in the case of Model 2, the prospective assessment of the economic situation, reducing the probability of feeling fear.

Finally, the presence and influence of some classical political variables in the analysis of political behaviour should be mentioned as they complete the explanation, especially in the case of Models 2 and 6. In the first case (Model 2), as the respondent’s ideological self-placement moves to the right of the ideological spectrum, the probability of feeling fear towards Pedro Sánchez increases. In the second case (Model 6), the expression of sympathy (partisan identification) towards right-wing (Partido Popular) and extreme right-wing (VOX) parties seemed to increase the probability of feeling fear towards the socialist leader in 2021.

5 Discussion

Whether social networks are used or not to consume political information is related to the existence of different emotional states. This statement confirms a clear division, already reported in previous studies, with regard to the forms of offline and online consumption in the hybrid information ecosystem (Chadwick, 2017), but not as regards the emotional consequences of such consumption. This demonstrates the validity of our first hypothesis, which we consider to be a significant contribution of this paper.

Among those who get their information through social networks, fear increases and anger decreases. A statement that connects the approaches by Marcus (2000, 2002) and Marcus et al. (2017) with those presented here to conclude that, while fear prompts people to seek alternative information, when this search involves the consumption of information on the social networks, the expression of anger increases. This would partially corroborate our second hypothesis, at least in terms of aggregate analysis. Demonstration through a panel study is needed, though, to show how a single individual turns fear into anger.

The role given to social networks is that of a catalyst, an enhancer or stimulant of emotions, particularly anger. Thus, the consumption of political information in these networked spaces leads to an exacerbation in this emotion. This could provoke an ‘anger spiral’ effect, which, as Wollebæk et al. (2019) pointed out, would result in greater anger among those participants who, already angry, seek information or participate in social networks. These effects are, for democracy, immediate. While political information is considered a necessary condition for both quality deliberation and participation (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2014), anger and the very configuration (polarised and targeted) of digital communities in social networks promote the ratification of previous opinions, generating a non-negotiated vision of political reality. This means that voters may even express anger towards the political party they are voting for. Or that dialogue, far from promoting a more deliberate, more negotiated democracy, may end up leading to the formation of increasingly closed and confrontational communities.

Thirdly, in addition to other aspects of a contextual nature that might influence the negative emotions expressed, fear exists among those who do not inform themselves about politics through social networks. This fear prompts, at the same time, the necessary search for such information, or in other words, the search for new or alternative narratives that help them to face new threats (Marcus, 2019). A fact that consolidates an interesting reflection on the role of offline and online media as generators of different emotions, reinforcing the specific model of attribution in social networks (Guo et al., 2012) and the spotlighting function of television during election periods (Roessler, 2008).

6 Conclusion

Based on the empirical evidence presented in this study, a series of interesting conclusions can be drawn. Firstly, the results of this study show that the fact of using or not using social networks to consume political information is related to a completely different emotional state for each of the groups (each group, in turn, also showing heterogeneity) with a general pre-eminence of anger for the former (those who access information through social networks) and a greater presence of fear in the latter (those who do not access information through the networks), especially in November 2019.

Secondly, from a longitudinal perspective, the data presented indicate that among those who do not access information through social networks, fear increases and anger decreases. This is not the case among those who access information through social networks, where fear remains constant, although anger increases. According to the empirical evidence provided, this occurred between April and November 2019, stabilising again in 2021.

Thirdly, citizens who are not informed about politics through social networks and feel fear towards Pedro Sánchez are shaping their opinion, as the modelling shows (with a moderate explanatory value), through another media, a traditional one: television. As exposure to television messages increases, the likelihood of feeling fear towards the socialist candidate also rises.

Finally, our results suggest that fear towards Pedro Sánchez is transformed into anger when individuals proactively search for information on social networks. However, future research should verify this finding specifically for Pedro Sánchez and replicate it with other political leaders.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Author contributions

JR: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. NL: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. EJ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. MP: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The execution of some of the demographic studies used in this research has been financed by the project “Consolidation 2022 GRC. GI-1161 - Political Research Team - Political Analysis (2022-PG036) Ref.ED431C 2022/36” awarded to the Political Research Team of the USC by the autonomous government of Galicia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1456412/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^ We should not lose sight of the fact that the November elections were themselves a repeat of the previous electoral process, which was motivated by the inability to form a government. They were the second elections called for that reason, and the fourth election process in less than 4 years.

2.^ For 15 years now, this research group has been carrying out a broad line of research focused on the study of the impact that the emotions expressed towards the political system, leaders, parties and even major political events have on citizens’ political decision-making processes. The questionnaires they use for their studies have been tested and standardised, allowing for comparability not only in the national context in question, but also in other contexts in which they have also been applied.

3.^ Specifically, this variable was included in both questionnaires with the following wording: Q.22.d. Do you use social networks to receive political information? (Response options: Yes, No, N/A).

4.^ Specifically, this variable was included in both questionnaires with the following wording: Q. 53. Now think about your emotions, about the emotions that politicians make us feel, even though sometimes we are not very aware of them. I am going to name a series of politicians and ask you to tell me if they have ever made you feel any of the emotions I am going to talk about (Response options: Yes, No, N/A).

5.^ For more information on these subjects, see Jaráiz et al. (2020).

6.^ As the authors explain, since 1980, the ANES study included only four emotions (two positive and two negative), in 1985 the battery was extended to a total of 12, adding one new positive and seven negative items.

7.^ Specifically, this variable was worded in both questionnaires as follows: P.22.d.1 In a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is never and 10 is very often how much do you use social networks for political information? (Answer 0–10).

8.^ The variables relating to the assessment of Pedro Sánchez and the assessment of his government’s performance were measured on a scale of 0–10, where 0 represented the worst assessment and 10 the best assessment. We would like to point out that in the 2021 study, the variable relating to the assessment of the government’s management focused on the management of the COVID-19 pandemic. In our understanding, however, it remains an evaluation of the government’s work, hence that we have decided to include it in the 2021 study.

9.^ The EIP-USC has always introduced in its opinion polls a specific measurement section dedicated to the concept of leadership. Particularly significant is the battery of questions aimed at measuring the degree of appreciation that citizens express towards a set of qualities represented in the figures of the different political leaders. This battery is the result of a process of testing in previous opinion polls. It initially emerged as a battery of 12 qualities of an ideal leader, which was later contrasted with specific political leaders and reduced to a total of six attributes: effectiveness, honesty, ability to obtain resources, concern for Spain over the party, proximity to citizens, good projects and charisma. In the diagrams, due to space constraints, only the two qualities with the highest average scores were included.

10.^ In 2021, the measurement of the evaluation of the qualities of national political leaders was not carried out. The information for this year, therefore, was not collected.

11.^ Apart from 2021 in the case of those who get their political information through social media and feel anger towards Pedro Sánchez.

12.^ Please note that this variable is an ordered scale from highest to lowest intensity.

References

1

Ahmed S. (2004). The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

2

Anduiza E. Cantijoch M. Gallego A. Salcedo J. L. (2010). Internet y participación política en España. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

3

Aranguren M. (2017). Reconstructing the social constructionist view of emotions: from language to culture, including nonhuman culture. J. Theory Soc. Behav.47, 244–260. doi: 10.1111/jtsb.12132

4

Averill J. (1980). “A constructivist view of emotion” in Theories of emotion. eds. PlutchikP.KellermanH. (New York: Academic Press), 305–339.

5

Averill J. (1982). Anger and aggression. New York: Springer-Verlag.

6

Averill J. (1986). “The acquisition of emotions during adulthood” in The social construction of emotion. ed. HarreR. (Oxford: Basil Blackwell), 98–119.

7

Bail C. (2016). Emotional feedback and the viral spread of social media messages about autism spectrum disorders. Am. J. Public Health106, 1173–1180. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303181

8

Bail C. Argyle L. Brown T. Bumpus J. Chen H. Hunzaker M. B. F. et al . (2018). Exposure to opposing views on social media can increase political polarization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.115, 9216–9221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804840115

9

Bazarova N. Yoon H. Sosik V. Cosley D. Whitlock J. (2015). Social sharing of emotions on Facebook: channel differences, satisfaction, and replies. Proceedings of the 18th ACM conference on computer supported cooperative work and social computing, 154–164.

10

Benski T. Fisher E. (2013). Internet and emotions. New York: Routledge.

11

Bode L. (2016). Political news in the news feed: learning politics from social media. Mass Commun. Soc.19, 24–48. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2015.1045149

12

Bossetta M. Segesten A. Trenz H. G. (2018). Political participation on Facebook during Brexit: does user engagement on media pages stimulate engagement with campaigns?J. Lang. Polit.17, 173–194. doi: 10.1075/jlp.17009.dut

13

Brady W. Wills J. Jost J. Tucker J. Van Bavel J. (2017). Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.114, 7313–7318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618923114

14

Burke M. Develin M. (2016). Once more with feeling: supportive responses to social sharing on Facebook. Proceedings of the 19th ACM conference on computer-supported cooperative work and social computing, 1462–1474.

15

Casero-Ripollés A. (2018). Investigación sobre información política y redes sociales: puntos clave y retos de futuro. El Profesional de la Información27, 964–974. doi: 10.3145/epi.2018.sep.01

16

Chadwick A. (2017). The hybrid media system: politics and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

17

Chen H. T. Gan C. Sun P. (2017). How does political satire influence political participation? Examining the role of counter-and pro-attitudinal exposure, anger, and personal issue importance. Int. J. Commun.11, 3011–3029.

18

Cho J. Ahmed S. Hilbert M. Liu B. Luu J. (2020). Do search algorithms endanger democracy? An experimental investigation of algorithm effects on political polarization. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media64, 150–172. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2020.1757365

19

Criado J. I. Martínez-Fuentes G. Silván A. (2013). Twitter en campaña: las elecciones municipales españolas de 2011. Revista De Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas12, 93–113.

20

Del Vicario M. Bessi A. Zollo F. Petroni F. Scala A. Caldarelli G. et al . (2017). Mapping social dynamics on Facebook: the Brexit debate. Soc. Networks50, 6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2017.02.002

21

Elster J. (2002). Alquimias de la mente. La racionalidad y las emociones. Barcelona: Paidós.

22

Fisher G. A. Chon K. K. (1989). Durkheim and the social construction of emotions. Soc. Psychol. Q.52, 1–9. doi: 10.2307/2786899

23

Gergen K. J. (1985). The social constructionist movement in modern psychology. Am. Psychol.40, 266–275. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.40.3.266

24

Giglietto F. Selva D. (2014). Second screen and participation: a content analysis on a full season dataset of tweets. J. Commun.64, 260–277. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12085

25

Gil de Zúñiga H. Molyneux L. Zheng P. (2014). Social media, political expression, and political participation: panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. J. Commun.64, 612–634. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12103

26

Gordon S. (1981). “The sociology of sentiments and emotions” in Social psychology: sociological perspectives. eds. RosenbergM.TurnerR. H. (New York: Routledge), 551–575.

27

Gordon S. (1989). “Institutional and impulsive orientations in the selective appropriation of emotions to self” in The sociology of emotions. eds. FranksD.McCarthyD. (London: Elsevier Limited), 115–145.

28

Grasso M. (2018). “Young people’s political participation in Europe in times of crisis” in Young people re-generating politics in times of crises. eds. PickardS.BessantJ. (UK: Palgrave Macmillan), 179–196.

29

Guo L. Vu H. T. McCombs M. (2012). An expanded perspective on agenda-setting effects: exploring the third level of agenda setting. Revista de Comunicación11, 51–68.

30

Harré R. (1986). The social construction of emotions. New York: Basil Blackwell.

31

Hasell A. Weeks B. (2016). Partisan provocation: the role of partisan news use and emotional responses in political information sharing in social media. Hum. Commun. Res.42, 641–661. doi: 10.1111/hcre.12092

32

Heredia Ruiz V. (2013). Participación política en redes sociales: el caso de los grupos en Facebook. Signo y Pensamiento32, 192–194. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.syp32-63.pprs

33

Jaráiz E. Lagares N. Pereira M. (2020). Emociones y decisión de voto. Los componentes de voto en las elecciones generales de 2016 en España. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas170, 115–136. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.170.115

34

Jaráiz E. Rivera J. M. Lagares N. López P. C. (2021). Emociones y engagement en los mensajes digitales de los candidatos a las elecciones generales de 2019. Cultura, Lenguaje Y Representación26, 229–245. doi: 10.6035/clr.5844

35

Jost J. T. Barberá P. Bonneau R. Langer M. Metzger M. Nagler J. et al . (2018). How social media facilitates political protest: information, motivation, and social networks. Polit. Psychol.39, 85–118. doi: 10.1111/pops.12478

36

Knoll J. Matthes J. Heiss R. (2020). The social media political participation model: a goal systems theory perspective. Convergence26, 135–156. doi: 10.1177/1354856517750366

37

Kramer A. D. I. Guillory J. E. Hancock J. T. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA111, 8788–8790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320040111

38

Kwak H. Lee C. Park H. Moon Sue (2010). What is twitter, a social network or a news media?Proceedings of the 19th international conference on world wide web, 591–600.

39

Lerner J. S. Keltner D. (2001). Fear, anger, and risk. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.81, 146–159. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.146

40

MacKuen M. Wolak J. Keele L. Marcus G. (2010). Civic engagements: resolute partisanship or reflective deliberation. Am. J. Polit. Sci.54, 440–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00440.x

41

Marcus G. (2000). Emotions in politics. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci.3, 221–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.221

42

Marcus G. (2002). Sentimental citizen: emotion in democratic politics. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press.

43

Marcus G. (2019). How fear and anger impact democracy. Brooklyn, United States: Democracy Papers Essay.

44

Marcus G. Neuman R. Mackuen M. (2000). Affective intelligence and political judgement. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

45

Marcus G. Neuman R. MacKuen M. (2017). Measuring emotional response: comparing alternative approaches to measurement. J. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods5, 733–754. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2015.65

46

Marcus G. Valentino N. Vasilopoulos P. Foucault M. (2019). Applying the theory of affective intelligence to support for authoritarian policies and parties. Adv. Polit. Psychol.40, 109–139. doi: 10.1111/pops.12571

47

McCarthy E. D. (1994). The social construction of emotions: new directions from culture theory. Social perspectives on emotion. Sociol. Faculty Publ.4, 267–279.

48

Neuman W. R. Marcus G. Mackuen M. (2018). Hardwired for news: affective intelligence and political attention. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media62, 614–635. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2018.1523169

49

Quintas-Froufe N. González-Neira A. (2014). Audiencias activas: participación de la audiencia social en la televisión. Comunicar: Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación22, 83–90. doi: 10.3916/C43-2014-08

50

Roessler P. (2008). “Agenda-setting, framing and priming” in The SAGE handbook of public opinion research. eds. DonsbachW.TraugottM. W. (New York: SAGE Publications), 205–218.

51

Serrano-Puche J. (2016). Internet y emociones: nuevas tendencias en un campo de investigación emergente. Comunicar: Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación24, 19–26. doi: 10.3916/C46-2016-02

52

Shahin S. Saldaña M. Gil de Zúñiga H. (2020). Peripheral elaboration model: the impact of incidental news exposure on political participation. J. Inform. Tech. Polit.18, 148–163. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2020.1832012

53

Stieglitz S. Dang-Xuan L. (2013). Emotions and information diffusion in social media—sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst.29, 217–248. doi: 10.2753/MIS0742-1222290408

54

Stier S. Bleier A. Lietz H. Strohmaier M. (2018). Election campaigning on social media: politicians, audiences, and the mediation of political communication on Facebook and twitter. Polit. Commun.35, 50–74. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2017.1334728

55

Tumasjan A. Sprenger T. O. Sandner P. G. Welpe I. M. (2010). Predicting elections with twitter: what 140 characters reveal about political sentiment. Icwsm4, 178–185. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v4i1.14009

56

Valentino N. A. Brader T. Groenendyk E. W. Gregorowicz K. Hutchings V. L. (2011). Election night’s alright for fighting: the role of emotions in political participation. J. Polit.73, 156–170. doi: 10.1017/s0022381610000939

57

Valentino N. A. Hutchings V. L. Banks A. J. Davis A. K. (2008). Is a worried citizen a good citizen? Emotions, political information seeking, and learning via the internet. Polit. Psychol.29, 247–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00625.x

58

Vasilopoulos P. Marcus G. Foucault M. (2018a). Emotional responses to the Charlie Hebdo attack: addressing the authoritarianism puzzle. Polit. Psychol.39, 557–575. doi: 10.1111/pops.12439

59

Vasilopoulos P. Marcus G. Valentino N. Foucault M. (2018b). Fear, anger, and voting for the far right: evidence from the November 13, 2015, Paris terror attacks. Polit. Psychol.40, 679–704. doi: 10.1111/pops.12513

60

Vissers S. Stolle D. (2014). The internet and new modes of political participation: online versus offline participation. Inf. Commun. Soc.17, 937–955. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.867356

61

Weber C. (2013). Emotions, campaigns, and political participation. Polit. Res. Q.66, 414–428. doi: 10.1177/1065912912449697

62

Williamson K. (1998). Discovered by chance: the role of incidental information acquisition in an ecological model of information use. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res.20, 23–40. doi: 10.1016/S0740-8188(98)90004-4

63

Wollebæk D. Karlsen R. Steen-Johnsen K. Enjolras B. (2019). Anger, fear, and Echo chambers: the emotional basis for online behavior. Soc. Media Soc.5, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/2056305119829859

64

Yarchi M. Baden C. Kligler-Vilenchik N. (2020). Political polarization on the digital sphere: a cross-platform, over-time analysis of interactional, positional, and affective polarization on social media. Polit. Commun.38, 98–139. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2020.1785067

65

Zollo F. Novak P. K. Del Vicario M. Bessi A. Mozetic I. Scala A. et al . (2015). Emotional dynamics in the age of misinformation. PLoS One10:e0138740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138740

Summary

Keywords

social media, political information, fear, anger, Spain

Citation

Rivera JM, Lagares N, Jaráiz E and Pereira M (2025) Information, social networks and emotions: fear and anger towards Pedro Sánchez 2019–2021. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1456412. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1456412

Received

28 June 2024

Accepted

18 October 2024

Published

08 January 2025

Volume

6 - 2024

Edited by

F. Ramón Villaplana, University of Murcia, Spain

Reviewed by

Adrián Megías, University of Almeria, Spain

Giselle García Hipola, University of Granada, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Rivera, Lagares, Jaráiz and Pereira.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María Pereira, maria.pereira.lopez@usc.es

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.