94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci., 03 January 2025

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1451406

This article is part of the Research TopicPublic Policies in the Era of PermaCrisisView all 12 articles

Introduction: Sustainable development is based on three interrelated and equally important pillars; the environmental, the economic and the social. The social pillar involves building a framework that promotes the well-being of the whole population with the ultimate aim of preserving social cohesion, while reducing social discrimination. In our analysis, the concept of social sustainability refers to the need for the creation of a society that contains all the conditions for sustainable development in terms of equal opportunities for employment and social well-being. Currently, significant problems and dysfunctions exist as long as several European labor markets are fragmented with a strong insiders-outsiders divergence, job-polarization, high labor market slack, high in-work poverty rates especially in precarious forms of employment. In Europe as well as globally, addressing these issues is of major importance in order to ensure social sustainability, given that the permacrisis (multiple crises), along with the Mega-Trends have a clear impact on the structure of economy and labor market, industrial relations systems, and business models.

Methods: The present paper analyses the state of play of social sustainability in Europe and aims to identify specific policy responses that could offer viable solutions to old and emerging challenges in terms of social inclusion through the examination of secondary quantitative data.

Results: The permacrisis era, along with the Mega-Trends that are taking place and seem to gradually have a clear impact on the structure of economy and labor market, substantially affecting every aspect of society, since social inequalities have the tendency to interrelate and getting reproduced.

Discussion: There is a need for knowledge-based and evidence-informed policy making, both in terms of policy design and implementation, for a true and actual sustainable (as well as inclusive) development, within momentous times.

Undoubtedly, social sustainability constitutes one of the substantial pillars of the sustainable development concept, although it is open to variations in its content and meaning, as there is no commonly accepted definition so far. In any case, this concept refers to the need to create a society that contains all the conditions for sustainable development in terms of equality, opportunities and social well-being.

The inclusion of social sustainability in the sustainable development conceptualization is first identified in the Brundtland Report (WCED, 1987) and the Rio reports of the United Nations (UN, 1992), in which a synthesis of the ecological, economic and social dimensions of social development takes place. Hence, these three areas were called dimensions or pillars of the concept of sustainability. At the same time, these pillars are not independent of each other but are interrelated and the existence of all three is a necessary condition for forming a comprehensive content to the concept of sustainability. In any case, the concept of social sustainability is related both to environmental issues and to issues of social well-being and cohesion, while considering the contribution of the private and public sectors to the processes of achieving these objectives, i.e., improving living conditions on equal terms.

Given the abovementioned, the scope- aim of this paper is to examine the role of social vulnerability within the welfare state framework during the perma-crisis era. This is achieved by exploring the way that public policies in the Eurozone and especially in Greece, have influenced the main pillars of social sustainability; employment, living conditions, healthcare and education. It is worth noting that while the case of Greece is emphasized, crucial comparisons are made with other Eurozone member states and especially the Southern, in order to contextualize the findings.

Our key research method is political analysis, combined with historical insights and secondary data analysis from Eurostat and Social Progress Imperative. Historical events, contexts, and secondary data are examined systematically and along with the current state-of-play data, in order to analyze the developments, in terms of social sustainability, the impact of the permacrisis in the Greek and the south European societies and the challenges that social policy is facing. Mainly, primary and secondary sources were gathered, especially policy documents, reports and data. Greece was selected as it was one of the main cases of the countries that was hard hit by the financial and debt crisis and data are compared with the other South European EU member states as they also faced similar problems and challenges and with the Eurozone and EU-27 averages.

The historical aspect in our political analysis is selected as it offers the opportunity to understand how past events and decisions have led to the present and have changed (Pierson, 2004), provides a deeper understanding of contemporary political issues through their historical analysis (Skocpol, 1992), uncovers hidden influences (Mahoney and Thelen, 2010), while it provides a comprehensive perspective on political phenomena (Hall, 2016) and enhances theoretical development (Lieberman, 2011).

The academic debate on the key determinants of sustainable development has started in the 1960s (UNEP, 2002), but the emphasis was initially on improving management, while the social and environmental pillars were not distinguished. It should be noted at this point, that sustainable development is based on three interrelated and equally important pillars; the environmental, the economic and the social. The environmental refers to the preservation and respect of the natural ecosystem and its functions; the economic is related to the creation of stable economic systems that ensure social justice without hindering the functioning of the free market while respecting the environment; and the social involves building a framework that promotes the well-being of the whole population with the ultimate aim of preserving social cohesion (Ekins, 2000), while reducing social discrimination. The transfer of the concept of sustainable development from the theoretical to the practical-institutional level first took place in 1972 with the report “The Limits to Growth” by the Rome Group, which referred to the decline of natural resources due to industrial pollution, population growth and economic growth, and the Stockholm Declaration of the United Nations, which placed a substantial focus on the environmental orientation of development (UNEP, 2002; Baker et al., 1997).

Both in the 1970s and even more intensively in the 1980s, the link between sustainable development and the environmental pillar was strengthened, to the point where the concept became synonymous with environmental sustainability (Evans and Thomas, 2004). However, the process of more closely linking and in some cases identifying the concept of sustainable development with environmental issues is seen by some scholars, such as Castro (2004), as a response to the growing radical environmental movement of the time that was putting obstacles to development. Therefore, it was necessary to find solutions that combined ecosystem protection while promoting economic and social progress. This was precisely the subject of the UN’s definition of sustainable development in the Brundtland Report, according to which sustainable development refers to the satisfaction of the present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED, 1987). This general definition provided the opportunity for the gradual development of a public debate around the content of the concept through the creation of several approaches, critical or supportive (Baker et al., 1997). Some of these approaches did not accept the link between the conventional concept of development and sustainable development but considered that these two concepts could work in parallel in order to prevail in the modern political-economic, globalized system (Rennen and Martens, 2003). In contrast, several international organizations developed the view that environmental sustainability should be part of neoclassical economic principles. However, the result of this inclusion has been the very low impact of environmental sustainability principles and the limited development of alternative effects that the concept of sustainable development can include, such as the social pillar, under the influence of the economic pillar. On the other hand, the view of the utmost importance of the concept of sustainable development was cultivated, as the protection of the environment must be the basic precondition for economic growth, so as not to undermine the well-being of future generations (Baker et al., 1997; Castro, 2004).

The debate on sustainable development and its content led to the creation of several different definitions, but the common element was the effort to deepen both the environmental issues and the socio-economic. Thus, the Rio Conference in 1992 brought together all these contributions to the public debate and several states signed Agenda 21 and the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, committing themselves to implementing a sustainable development policy that respects the principles mentioned (UN, 1992). Sustainable development is also included in the 1996 UN Istanbul Conference, during which it was stated that sustainable development for settlements (the subject of the conference was human settlements) is necessary to combine economic development with social development and environmental protection (UN, 1998). The protection and respect of human rights and individual freedoms was set as a necessary condition for achieving this objective. There is a greater effort to link the three pillars mentioned above (environmental, economic and social) as a prerequisite for achieving sustainability.

Within a year (1997) the Third UN Conference was held, in which an international legal instrument was established for the first time to promote sustainable development, which would control its main pillars but would focus mainly on environmental protection, and was called the “Kyoto Protocol” (UN, 1998). Finally, the UN conference in Johannesburg in 2002 and, more importantly, the 2012 conference on sustainable development in Brazil, were characterized by the attempt to link the three pillars and consequently to consolidate the coexistence of economic development, environmental protection and the safeguarding of social cohesion (UN, 2002). In Johannesburg issues were raised relating to: (a) the importance of civil society and the private sector in promoting inclusiveness and cooperation between different actors (with the ultimate aim of strengthening social entrepreneurship in order to promote sustainable development), (b) the link between green growth and the battle against unemployment and poverty, and (c) institutional reorganization at international, national and regional level in order to achieve sustainable development.

The United Nation’s (UN) most recent “Agenda 2030” for Sustainable Development (“Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”), signed in August 2015, sets 17 global strategic goals that will balance social, economic and environmental needs and commit to the effective implementation of Sustainable Development. At the same time, in the European Union, the establishment of the European Pillar of Social Rights in 2017, sets certain objective in the course of satisfying social rights, thus making a crucial step toward social sustainability (ETUI, 2021). Although European integration in social issues has not taken a comprehensive dimension, the European Pillar of Social Rights is particularly important because it includes the principles and necessary values in order to achieve social prosperity and social cohesion, thus social sustainability.

Before delving into the analysis of the social sustainability dimensions, it should be mentioned that due to the lack of agreement on the content of the term, different approaches (Shirazi and Keivani, 2019) often appear, not driven by the theoretical thinking that leads to the research on specific domains but by practical issues in different circumstances and under different research methods. Hence, reformist approaches argue for a balance in the three pillars of sustainability (Peterson, 2016), revisionist focus on the addition of a cultural pillar (Soini and Birkeland, 2014) and others stress issues related to governance (Leal Filho et al., 2016), to the political bottom line (Bendell and Kearins, 2005) as well as to ethical values (Burford et al., 2013). In addition, the connection between the three pillars of sustainability, in some cases, continues to be unclear while different priorities are given to each of these directions and they are not integrated as a whole, giving the concept of sustainability an unclear and often “open” content, thus, highlighting the need for further study that leads to a clearer and more comprehensive definition. In this light, we will try to include in the term social sustainability all those dimensions that are necessary and should be included in relevant considerations of sustainability, thus contributing to the clarification of the role of individual actors in achieving social sustainability.

It is noteworthy, that generally, social sustainability is connected to the capacity of a given society to support social well-being, to provide equal access to basic resources as well as to enhance social inclusion. These basic objectives emphasize on the creation of a just society, in which all individuals could thrive and develop (Boström, 2012). In order to achieve these basic goals, societies should incorporate the basic policies in order to reduce inequality and promote fairness in the distribution of resources and opportunities. Thus, public policies which focus on equitable and inclusive education, equal healthcare provision for all citizens, adequate housing and equal employment opportunities (Dempsey et al., 2011), along with the preservation of basic labor rights, are in line with the main social sustainability objective to create an equitable and socially just society as a prerequisite in order to remain sustainable. While constructing citizens’ human capital is crucial (Hemerijck, 2017), it is equally important to build the context in which individuals and groups could feel connected, included and supported; therefore develop their social capital. Thus, by participating in community life and having strong social networks, citizens could experience the sense of belonging (Colantonio and Dixon, 2011) while social cohesion could broadly expanded. However, social sustainability could not be realized without top-down policies that improve the quality of life by addressing social problems such as poverty, unemployment and social exclusion. Therefore, welfare systems should enable individuals to access basic needs and services which ensure an acceptable standard of living for all citizens (Nussbaum and Sen, 2002). Finally, social sustainability also requires democratic participation and engaging decision-making processes for citizens in which all social groups influence the policy shaping processes (Lehtonen, 2004).

For several scholars, social sustainability is interconnected with environmental and economic sustainability. For instance, Shirazi and Keivani (2019) underline the attention that should be given to the social pillar of sustainability as they recognize that it is under-theorized, while Boström (2012) argues that social sustainability encompasses a wide range of concepts and lacks a universally agreed framework. Boström (2012) also underlines that the concept of social sustainability could include – as already mentioned above – welfare policies that aim to address social problems, such as poverty, as well as civic processes, like community engagement.

The main challenge for every scholar who tries to study social sustainability is its operationalization. In order to achieve such a goal specific indicators should be used in measuring quality of live, social progress and social problems. Thus, due to the fact that the Social Progress Index captures some aspects of social sustainability, such as education, healthcare and personal safety and the Eurostat data focus on several similar but specialized aspects of social vulnerability, such as employment-unemployment and job quality, healthcare needs as well as poverty and social exclusion, they are both selected in order to depict crucial parameters of social sustainability in Greece and Southern Europe, in comparison with Eurozone and EU-27 averages.

One of the key terms set out by the Brundtland report on sustainable development was that the concept of sustainability necessarily includes that of needs, highlighting a kind of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising those of future generations, thus indicating the interconnection between nature and society, giving a human-centered dimension to sustainability and highlighting intergenerational solidarity. Certainly, the concept of need must be seen in its broadest form, since on the one hand it includes, in the context of the environment, the satisfaction of nutritional energy and other needs in a way that does not compromise the ecological dimensions and the durability of resources, while, on the other hand, there are social needs, which include a wide range of sub-categories such as health, retirement and education (Papadakis and Tzagkarakis, 2024; Papadakis et al., 2022). Consequently, if the concept extends to meeting needs such as education, personal development and social relations, then a much greater activation in terms of interventions is required, leading to the achievement of social well-being.

It should be noted that well-being should not be regarded as identical with welfare, even though they might be connected. Well-being encompasses broader parameters of life quality, including happiness and personal fulfillment while welfare is mainly connected with income and the provision of social goods in order to achieve social risk mitigation and ensure minimum living standards (Frijters, 1999). Therefore, while the two concepts share crucial connections they represent different dynamics, as well-being includes parameters which are not merely connected with income or material goods. However, while welfare preservation may increase the possibility for improving individuals’ well-being (Greve, 2018), some studies have shown that there is a limited connection between the two concepts (Veenhoven, 2000). In our analysis the two concepts are not interpreted as identical but as interconnected.

Employment is one of the key development factors and at the same time, constitutes the basic precondition for achieving social sustainability, as on the one hand, it plays a key role in meeting needs and on the other, it improves living conditions by combining the satisfaction of social and environmental factors. Hence, a key component in achieving social sustainability is the creation of conditions and opportunities for the satisfaction of individual needs. Consequently, employment, which is one of the dominant factors for achieving individual autonomy, through the existence of appropriate norms, institutions and normative-protective frameworks, could achieve individual well-being if promoted in a socially just context. At this point we should bear in mind, the rising of the precarious work in Europe, as well as globally, that affects social inclusion. Further the rising mega- trends affect employability. It should be noted that during the previous decade, namely the years 2010–2019, part-time workers in the EU were twice the risk of poverty than those employed full-time (Eurostat, 2020c), while the risk of poverty in temporary employment increased considerably in the majority of EU28 countries (Eurostat, 2020a,b), while the risk was almost three times higher for employees with temporary jobs, than for those with permanent jobs (Eurostat, 2020c).

Thus, there is a strong correlation between precarious employment, social vulnerability and risk of poverty (Papadakis et al., 2021; Papadakis et al., 2022). Further, Mega-Trends that are taking place and seem to gradually prevail [e.g., globalization, digital economy, digitalization, demographic and social changes, climate change, etc.- Eurofound (2020: 3–4)] have a clear impact on the structure of economy and labor market, industrial relations systems, and business models, having, in turn, direct impact on work relations, forms of employment and contracts types and, consequently, on social welfare systems in Europe (Eurofound, 2020: 3–4). Given all the abovementioned, we are not simply referring to the use of resources to meet needs but to the construction of a society that will organize individual life trajectories in an efficient and socially just manner (Senghaas-Knobloch, 1998).

In this context, the form of welfare provided by the state constitutes one of the primary characteristics of modern societies and shapes the conditions for their development within the ever-globalizing system (Pfau-Effinger, 2000). Socially sustainable development should include the reorganization and promotion of the social welfare concept (HBS, 2001; Brandl and Hildebrandt, 2002). Therefore, rights such as employment must be safeguarded not only in terms of ensuring adequate income but also with regard to psychosocial dimensions such as working time, social integration and the importance of wage employment for social cohesion (Senghaas-Knobloch, 1998). At the same time, rights to education and health as well as equal access to goods and services, gender equality and tolerance, are aspects of primary importance for achieving social sustainability.

Different factors could be distinguished that contribute to the achievement of the social dimension of sustainability. A first category could include all those factors related to the satisfaction of basic needs and the improvement of life quality (Papadakis and Tzagkarakis, 2024). Therefore, they are related to the level of individual income, poverty, income distribution, unemployment, education, training and lifelong learning, housing, health, insurance and employment that satisfies both material and psychosocial needs. The achievement of these goals-factors can only be realized if there is a level of social justice that implies fairness in terms of opportunities for quality of life and participation in civil society (Nussbaum and Sen, 2002; Löffler, 2004). The next level for achieving social sustainability is social consistency, i.e., social integration through participation in social networks and voluntary actions where the concept of solidarity is realized outside formal institutional and normative frameworks as part of citizenship. These theoretical dimensions could be transferred to the level of political practice through the welfare state and the framework of social policies-social rights it promotes.

Social policy (in all different fields such as health, labor, cash-benefits, pension etc.) is a deliberate intervention by the state to redistribute resources among citizens as a way to achieve social welfare and sustainability. Hence, in order to achieve social sustainability, it is necessary to implement social policy through the institutional framework of the welfare state. The concept of well-being is interconnected but not synonymous with that of welfare, thus creating a framework for reducing social inequalities and promoting equal access to social goods and services, in order to increase the quality of life.

Even though welfare conceptually is narrower than well-being (Greve, 2008), in their interconnection the concept of well-being involves two opposing perspectives that have had a major influence on ideological orientations of social policies and the scope of the welfare state [see Papadakis and Tzagkarakis (2024)]: (a) welfare is identified as well-being for all and therefore it includes the promotion of social protection as a right which implies the notion of universality and (b) care is also offered to those most in need, by implementing selective welfare policies in areas, such as cash-benefits and care services, as a lever for reducing inequalities.

The economic crisis, the pandemic and the current energy crisis highlight the necessity of the welfare state in protecting citizens from the multidimensional social risks that are being reproduced, multiplied or readjusted. At the international level, the socio-economic context is becoming more complex, with more interdependence and a speed of events that is constantly increasing (Schwab and Malleret, 2021), creating new challenges for achieving social sustainability. The permacrisis era (multiple crises which form a context of permanent crisis) highlights that the respective public policies need to be more prepared for phenomena that one might mistakenly consider rare (see Oyelere et al., 2023). The Covid-19 pandemic, as well as all other crises occurred the last decades (economic, energy, migration etc.), are not “black swan” but “white swan” phenomena (Schwab and Malleret, 2021: 34), as humanity has experienced similar situations many times in the past, if one takes into account the historical data of pandemics (Huremović, 2019) as well as economic (Sewell, 2012) and migratory crises (Hoerder, 2019). At the level of social policy, permacrisis legacy indicates the importance of an organized, effective and inclusive welfare state.

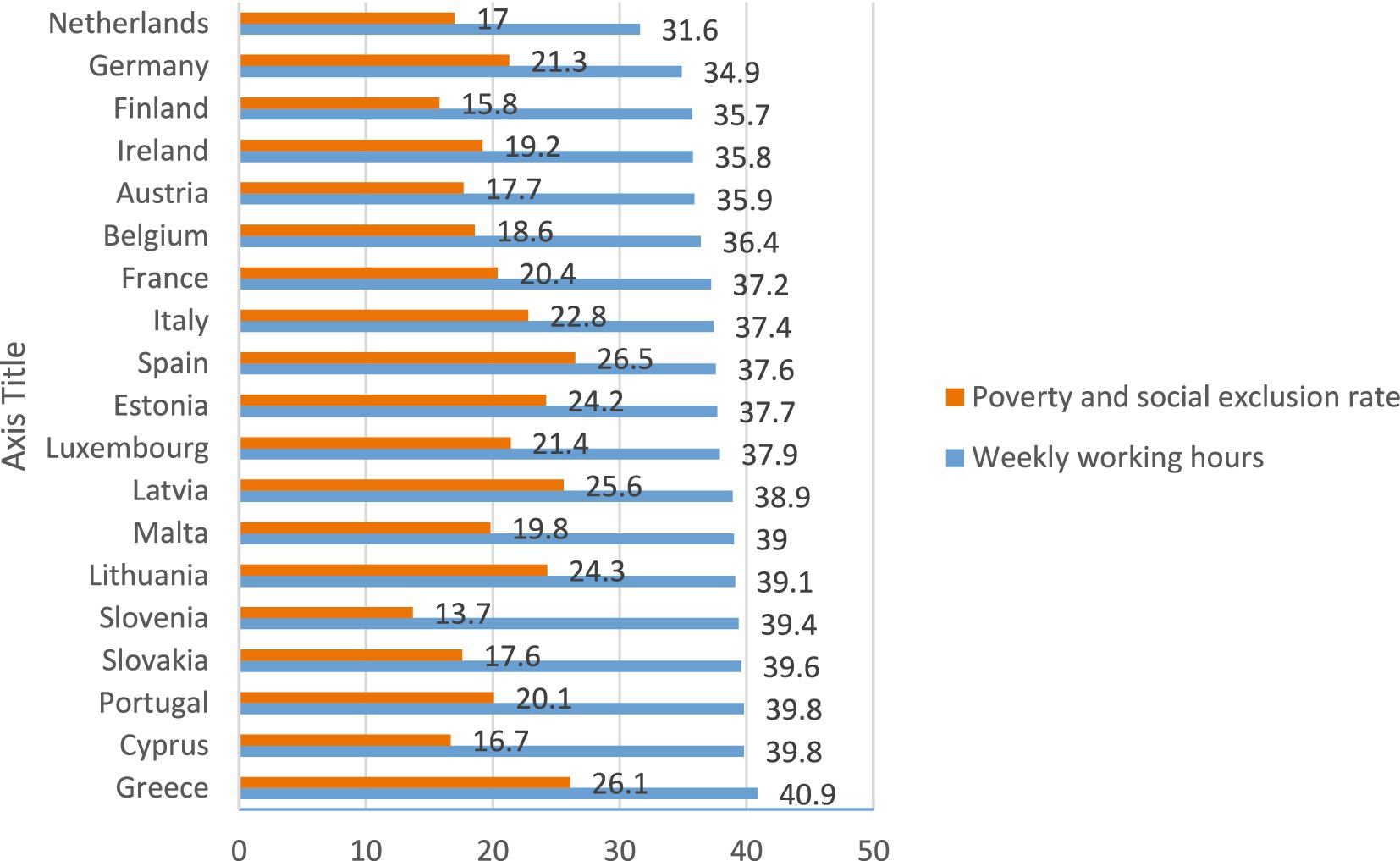

The labor market in the Southern European countries, is often considered to be fragmented and divided into the following sectors: central, regional and informal/underground. This fragmentation creates more strongly the problem of insiders- outsiders (Ferrera, 1996, 2010; Moreno, 2000; Papadakis et al., 2021) as well as it increases precarity, in-work poverty and social vulnerability in general (Jessoula et al., 2010; Mulé, 2016). Hence, over time, Southern European countries have had higher in- work poverty rates than the EU average (see Figure 1), despite a downward trend in recent years, which follows the trend at EU level, but does not reduce the existing gap between South Europe and the EU average. The qualitative characteristics of this indicator show that older employees are more likely to be at risk of in-work poverty. Moreover, employees with low educational attainment, the self-employed (which underlies the case of freelancers), contract workers and part-time employees have over time been the groups most at risk of in-work poverty (Ziomas et al., 2019; Papadakis et al., 2022). At the same time, poverty and social exclusion indicators are higher than the EU average in southern European member states (Greece, Spain, Italy, Portugal) as well as in some eastern (Romania, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Estonia) while working hours are still higher in countries, such as Greece, with high in-work poverty rates as well as poverty and social exclusion rates (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Weekly working hours and poverty and social exclusion rates in Eurozone member states in 2023. Source: Eurostat.

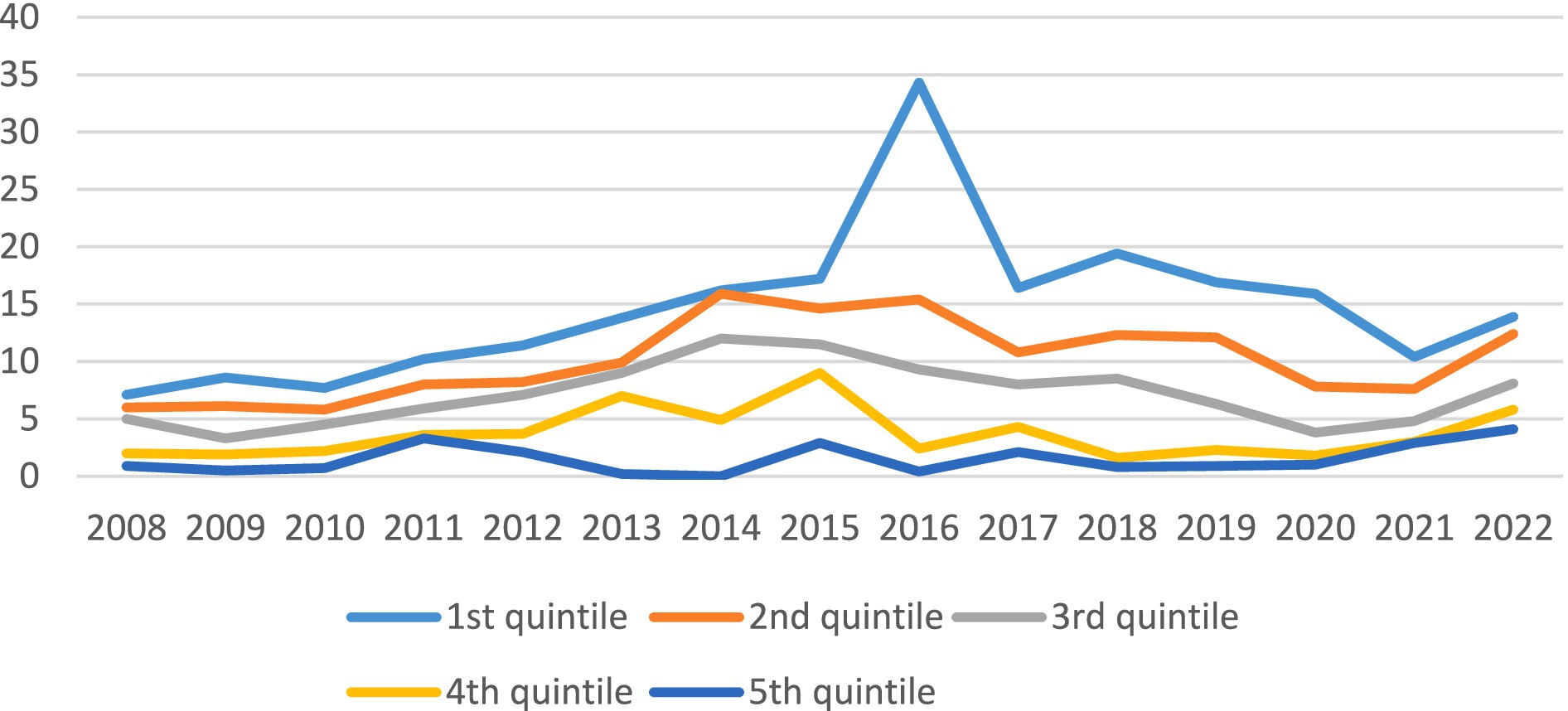

One of the most important challenges for the welfare state services is to offer equal coverage of health needs in order to facilitate a healthier life for all citizens. However, recent data show that in countries such as Greece, the access of economically vulnerable individuals has been reduced in the years of permacrisis (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Non satisfaction of health needs due to economic reasons per income quantile in Greece (1st = lower income, 5th higher income). Source: Eurostat.

Social Progress Index show that Greece is a laggard in terms of providing the circumstances for achieving social well-being (Social Progress Imperative, 2024). While the rest South European countries seem to be close to the EU-27 average Greece is lagging behind especially because it fails to provide the high quality context mainly on the foundations of wellbeing and opportunities (see Table 1). These are not only connected with the welfare services per se but also with the overall context of constructing a sustainable society.

At the same time, the shift to teleworking, especially during and after the pandemic, is a crucial transformative factor of the labor market, as the economy is currently increasingly based on working through online platforms. In this form of employment, employees are often neither permanent nor part-time but offer work in pieces (gigs), which intensifies the deregulation of work and the risks for them (Bieber and Moggia, 2021). While promoting teleworking creates new opportunities for trade and innovation, inequalities could be further increased, especially for those in the peripheral and informal sector - rotational employment, freelance and non-formal employment (Nieuwenhuis and Yerkes, 2021). Furthermore, the phenomenon of family-work life balance disruption occurs because the employee tends to be in a stand-by situation. The “right to disconnect” and the non-violation of working hours, if respected, can create positive effects. Therefore, there is a necessity to safeguard labor rights, enhance digital skills, strengthen small and medium entrepreneurship and provide incentives for new jobs in order to achieve social sustainability (Papadakis and Tzagkarakis, 2024; Papadakis et al., 2021).

Given the abovementioned mega-trends’ impact on society and economy, it seems that in the coming years, global employment supply is expected to increase jobs related to new technologies, artificial intelligence, digitization and automation, while it is expected to decrease traditional forms of employment such as secretarial support, accounting, administration and unskilled labor (World Economic Forum, 2020). Skills such as analytical thinking and innovation, critical thinking, leadership, creativity and flexibility (inherent in social sciences and humanities content), as well as knowledge of using new technologies, planning, design and digital marketing, will become necessities in the coming years (World Economic Forum, 2020).

Due to the expansion of digital platforms and teleworking the phenomenon of lego flexibility occurs. Lego flexibility refers to the fact where the production of each product is divided into its component parts. These components are produced in areas where costs are low, quality is high, sufficiency is excellent and the rate of innovation is above average and high (Garud et al., 2003; Sennett, 2006). Each of these four elements brings in different components from different parts of the world, but they eventually come together to make up the product, which may be a mobile phone, a car, a computer, etc. Lego flexibility depends on having an organizational form in which multifunctional teams are the smaller units and global competence teams are the global unit (Azmat et al., 2012). Furthermore, it is vital to assign a central role to knowledge development, knowledge transfer, feedback processes, co- creation, and social sentiment analysis (Susskind and Susskind, 2015; Meister and Mulcahy, 2017).

It turns out that there will be huge social consequences if this kind of lego flexibility is enacted globally (Standing, 2011, 2014), and will represent the development of a new form of global distribution of labor and occupational specialization (Gaskarth, 2015). The above-mentioned impact should be further explores and analyzed, via relevant research. In this new landscape, skill development, careers, individual risk and wealth creation processes will all undergo inherent changes. One outcome of this kind of lego flexibility will be that sovereign states could easily lose control of wealth creation processes (Stearns, 2013; Kessler, 2018). In the 1980s and 1990s a large part of the labor force moved from industrial production to jobs in the service sectors (Enderwick, 1989; Foster, 2014). This movement took place both through cuts in the number of traditional manufacturing jobs and an increase in service sector jobs (Thurow, 1999). On the threshold of the fourth industrial revolution, knowledge economy workers - the backbone of the middle class - are now under threat (Coates and Morrison, 2016), as well as service sector workers (Frey and Osborne, 2013). And this transformation constitute another future research field.

The key focus of the welfare states in order to achieve social sustainability during this transformative era should be given to public policies which prepare individuals and societies for fundamental adjustments such as those in labor market, in the environment and in the population (ageing). An important strategy in order to achieve higher levels of social sustainability is social investment, which addresses the fundamental sources of the problems based on the concept of humanism but also on the protection of the environment and the achievement of economic sustainability. One of the main challenges is to broaden the tax base (special tax on higher incomes to reduce inequalities) and jointly increase productivity and the quality of employment, invest in human capital, which allows more and better jobs to be created and offer the opportunity for the development of social capital through enhancing participation, democratic dialog and citizenship.

As social sustainability means inclusive society and welfare for all there should be given a focus on the knowledge society as well as on investments in education, training, reskilling innovation and new technologies. In times of permacrisis, the welfare state is more necessary than ever. It is therefore essential for the state to undertake systematic interventions to boost demand and thus create new jobs. Integration into the labor market and investment in innovation should guide the educational process from infancy through the phases of vocational training and university education. Thus, closer cooperation between employment services and employers, as well as social economy players, is essential.

Defining the concept of social sustainability is a major challenge. However, an attempt to emphasize also on the role of an inclusive and active welfare state is made in the present study. Hence, social sustainability is directly connected with equality of access to important services such as health and education, the concept of intergenerational solidarity combined with solidarity between members of the same generation, the acceptance of cultural diversity, the promotion of citizenship, the promotion of the idea of belonging to a society in order to enhance social participation and action, as well as the creation of incentives to strengthen the social economy and subsequently social inclusion [see Papadakis and Tzagkarakis (2024)].

To conclude: the permacrisis era, along with the Mega-Trends that are taking place and seem to gradually have a clear impact on the structure of economy and labor market, substantially affecting every aspect of society, since social inequalities have the tendency to interrelate and getting reproduced [see Wilkinson and Pickett (2009)]. All the abovementioned highlight the need for knowledge-based and evidence-informed policy making, both in terms of policy design and implementation, for a true and actual sustainable (as well as inclusive) development, within momentous times.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_iw07&lang=en.

NP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Azmat, G., Manning, A., and Van Reenen, J. (2012). Privatization and the decline of the labour’s share, international evidence from network industries. Economica 79, 470–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2011.00906.x

Baker, S., Kousis, M., Richardson, D., and Young, S. (1997). “Introduction: the theory and practice of sustainable development in EU perspective” in The politics of sustainable development. Theory, policy and practice within the European Union. eds. S. Baker, M. Kousis, D. Richardson and S. Young (London: Routledge), 1–38.

Bendell, J., and Kearins, K. (2005). The political bottom line: the emerging dimension to corporate responsibility for sustainable development. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 14, 372–383. doi: 10.1002/bse.439

Bieber, F., and Moggia, J. (2021). Risk shifts in the gig economy: the normative case for an insurance scheme against the effects of precarious work. J Polit Philos 29, 281–304. doi: 10.1111/jopp.12233

Boström, M. (2012). A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: introduction to the special issue. Sustainability 8, 3–14.

Brandl, S., and Hildebrandt, E. (2002). Zukunft der Arbeit und soziale Nachhaltigkeit. Zur Transformation der Arbeitsgesellschaft vor dem Hintergrund der Nachhaltigkeitsdebatte. Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Burford, G., Hoover, E., Velasco, I., Janoušková, S., Jimenez, A., Piggot, G., et al. (2013). Bringing the “missing pillar” into sustainable development goals: towards intersubjective values-based indicators. Sustain. For. 5, 3035–3059. doi: 10.3390/su5073035

Castro, C. J. (2004). Sustainable development: mainstream and critical perspectives. Organ. Environ. 17, 195–225. doi: 10.1177/1086026604264910

Colantonio, A., and Dixon, T. (2011). “Social Sustainability and Sustainable Communities: Towards a Conceptual Framework” in Urban regeneration and social sustainability. eds. A. Colantonio and T. Dixon (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), 20–36.

Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S., and Brown, C. (2011). The social dimension of sustainable development: defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 19, 289–300. doi: 10.1002/sd.417

ETUI (2021). The 20 principles of the European Pillar of Social Rights. Available at: https://www.etui.org/facts_figures/20-principles-european-pillar-social-rights (Accessed: 19/04/2023).

Eurofound (2020). Labour market change: Trends and policy approaches towards flexibilisation. Challenges and prospects in the EU series. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurostat (2020a). In-work at-risk-of-poverty rate by full−/part-time work - EU-SILC survey [ilc_iw07]. Available at: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_iw07&lang=en (Accessed February 15, 2022).

Eurostat (2020b). In-work at-risk-of-poverty rate by type of contract - EU-SILC survey [ilc_iw05]. Available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_iw05&lang=en (Accessed February 15, 2022).

Eurostat (2020c). 1 in 10 employed persons at risk of poverty in 2018. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20200131-2 (Accessed February 15, 2022).

Evans, T., and Thomas, C. (2004). “Poverty, hunger and development” in The globalization of world politics. An introduction to international relations. eds. J. Baylis and S. Smith (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 419–434.

Ekins, P. (2000). Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability: the Prospects for Green Growth. London: Routledge.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The southern model of welfare in social Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 6, 17–37. doi: 10.1177/095892879600600102

Ferrera, M. (2010). “The south European countries” in The Oxford handbook of the welfare state. eds. F. G. Castles, S. Leibfried, J. Lewis, H. Obinger, and C. Pierson (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 616–629.

Foster, P. A. (2014). The Open Organization: A New Era of Leadership and Organizational Development. Burlington, VT: Gower Publishing Company.

Frey, C. B., and Osborne, M. A. (2013). The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization. Oxford: Oxford Martin School Press. https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdf (Accessed: July 18, 2021).

Garud, R., Kumaraswamy, A., and Langlois, R. (2003). “Managing in the modular age: New perspectives on architectures, networks and organisations” in Introduction: Managing in the Modular Age: Architectures, Networks, and Organizations. eds. R. Garud, A. Kumaraswamy, and R. Langlois (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.) 1–11.

Gaskarth, J. (2015). China, India and the future of international society. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Greve, B. (2018). “What is welfare and public welfare?” in Routledge handbook of the welfare state. ed. B. Greve (London: Routledge), 5–12.

Hall, P. A. (2016). “Politics as a process structured in space and time” in The Oxford handbook of historical institutionalism. eds. O. Fioretos, T. G. Falleti, and A. Sheingate (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 31–50.

HBS (2001). Pathways to a sustainable future. Düsseldorf: Results from the Work and Environment Interdisciplinary Project.

Hemerijck, A. (2017). “Social investment and its critics” in The uses of social investment ed. A. Hemerijck (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 3–39.

Hoerder, D. (2019). “Migrations and macro-regions in times of crises. Long-term historiographic perspectives” in The Oxford handbook of migration crises. eds. C. Menjívar, M. Ruiz, and I. Ness (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 21–36.

Huremović, D. (2019). “Brief history of pandemics (pandemics throughout history)” in Psychiatry of pandemics: A mental health response to infection outbreak. ed. D. Huremović (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 7–35.

Jessoula, M., Graziano, P., and Madama, I. (2010). ‘Selective’ Flexicurity in segmented labour markets. The emergence of mid-siders in the Italian case. J. Soc. Policy 39, 561–583. doi: 10.1017/S0047279410000498

Kessler, S. (2018). Gigged: The end of jobs and the future of work. New York: Random House Business.

Leal Filho, W., Platje, J., Gerstlberger, W., Ciegis, R., Kääriä, J., Klavins, M., et al. (2016). The role of governance in realizing the transition towards sustainable societies. J. Clean. Prod. 113, 755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.11.060

Lehtonen, M. (2004). The environmental-social interface of sustainable development: capabilities, social capital, institutions. Ecol. Econ. 49, 199–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.03.019

Lieberman, R. C. (2011). Shaping race policy: The United States in comparative perspective. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Löffler, W. (2004). “Was hat Nachhaltigkeit mit sozialer Gerechtigkeit zu tun? Philosophische Sondierungen im Umkreis zweier Leitbilder” in Religion und Nachhaltigkeit. Multidisziplinäre Zugänge und Sichtweisen LIT. ed. B. Littig (Münster), 41–70.

Mahoney, J., and Thelen, K. (2010). Theory of Gradual Institutional Change” in Explaining institutional change: Ambiguity, agency, and Power. eds. J. Mahoney, and K. Thelen. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 1–37.

Moreno, L. (2000). “The Spanish development of southern welfare” in Survival of the welfare state. ed. S. Kuhnle (London: Routledge), 146–165.

Mulé, R. (2016). Coping with the global economic crisis: the regional political economy of emergency social shock absorbers in Italy. Reg. Fed. Stud. 26, 359–379. doi: 10.1080/13597566.2016.1215308

Nieuwenhuis, R., and Yerkes, M. A. (2021). Workers’ well-being in the context of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Community Work Fam. 24, 226–235. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2021.1880049

Nussbaum, M., and Sen, A. (2002). The quality of life. Oxford, New York and Aukland: Clarendon Press.

Oyelere, M., Olowookere, K., Oyelere, T., Opute, J., and Ajibade Adisa, T. (2023). “The conceptualisation of employee voice in Permacrisis: a UK perspective” in Employee voice in the global north: Insights from Europe, North America and Australia eds. T. Ajibade Adisa, C. Mordi, E. Oruh (Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham), 9–34.

Papadakis, N., Drakaki, M., Saridaki, S., Amanaki, E., and Dimari, G. (2022). Educational capital/ level and its association with precarious work and social vulnerability among youth, in EU and Greece. Int. J. Educ. Res., Special Issue: "Cultural reproduction, cultural resource and reading" 112, 101921–101914. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101921

Papadakis, N., Drakaki, M., Saridaki, S., and Dafermos, V. (2021). “The degree of despair”. The disjointed labour market, the impact of the pandemic, the expansion of precarious work among youth and its effects on young people's life trajectories, life chances and political mentalities- public trust. The case of Greece. Eur. Quart. Political Attitudes Mentalities 10, 26–53.

Papadakis, N., and Tzagkarakis, S. (2024). “Evidence-based policy making towards social sustainability” in The ERAZ selected papers of the proceedings of the 9th international scientific conference entitled: Knowledge based sustainable development – ERAZ 2023 (organized by the Association of Economists and Managers of the Balkans) (Belgrade: UdEcom Balkan), 103–114.

Peterson, N. (2016). Introducing to the special issues on social sustainability: integration, context, and governance. Sustainability 12, 3–7. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2016.11908148

Pfau-Effinger, B. (2000). “Wohlfahrtsstaatliche Politik und Frauenerwerbstätigkeit im europäischen Vergleich – Plädoyer für eine Kontextualisierung des theoretischen Erklärungsrahmens” in Geschlecht- Arbeit – Zukunft. eds. I. Lenz, H. Nickel, and B. Riegraf (Münster: Westfälische Dampfboot), 75–94.

Pierson, P. (2004). Politics in time: History, institutions, and social analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rennen, W., and Martens, P. (2003). The Globalisation Timeline. Integrated Assessment, 4, 137–144. doi: 10.1076/iaij.4.3.137.23768

Senghaas-Knobloch, E. (1998). Von der Arbeits - zur Tätigkeitsgesellschaft? Politikoptionen und Kriterien zur ihrer Abschätzung. Feministische Studien 16, 9–30. doi: 10.1515/fs-1998-0203

Sewell, W. H. Jr. (2012). Economic crises and the shape of modern history. Publ. Cult. 24, 303–327. doi: 10.1215/08992363-1535516

Shirazi, M. R., and Keivani, R. (2019). “Social sustainability discourse. A critical revisit” in Urban social sustainability. Theory, policy and practice. eds. M. R. Shirazi and R. Keivani (London and New York: Routledge), 1–26. doi: 10.4324/9781315115740-1

Skocpol, T. (1992). Protecting soldiers and mothers: The political origins of social policy in the United States. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Social Progress Imperative (2024). Global Social Progress Index. Available at: https://www.socialprogress.org/social-progress-index (Accessed April 18, 2024).

Soini, K., and Birkeland, I. (2014). Exploring the scientific discourse on cultural sustainability. Geoforum 51, 213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.12.001

Standing, G. (2011). “The precariat: the new dangerous class” in London, UK (New York, NY: Bloomsbury).

Susskind, R., and Susskind, D. (2015). The future of professions: How technology will transform the work of human experts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

UN (1992). Agenda 21, United Nations conference on environment and development. Brazil: Rio de Janeiro.

UN (1998). Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available at: http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/kpeng.pdf (Accessed February 15, 2022).

UN (2002). Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, South Africa. Available at: http://www.un.org/jsummit/html/documents/summit_docs/131302_wssd_report_reissued.pdf (Accessed February 15, 2022).

Veenhoven, R. (2000). Well-being in the welfare state: level not higher, distribution not more equitable. J. Comp. Policy Anal. 2, 91–125.

WCED, (1987). World Commission on Environment and Development. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. United Nations.

Keywords: sustainable development, social sustainability, social policy, mega-trends, permacrisis, welfare state

Citation: Papadakis N and Tzagkarakis SI (2025) Welfare state, social policy and social sustainability, within the context of the permacrisis. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1451406. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1451406

Received: 19 June 2024; Accepted: 12 December 2024;

Published: 03 January 2025.

Edited by:

Andrzej Klimczuk, Warsaw School of Economics, PolandReviewed by:

Mary Koutselini, University of Cyprus, CyprusCopyright © 2025 Papadakis and Tzagkarakis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nikos Papadakis, cGFwYWRha25AdW9jLmdy

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.