94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Polit. Sci., 11 September 2024

Sec. Peace and Democracy

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1448241

This article is part of the Research TopicGeopolitical Transition and Competition Among Major Global Power Centers: Existential Security Challenges and Regional ConflictsView all 3 articles

The People’s Republic of China (PRC)‘s rapid development of military maritime capabilities, and their harnessing under strong personalist paramount leader Xi Jinping to address ambitious national goals, is one of the most important subjects concerning great power security in the international system today. Understanding the key dynamics is thus inherently important. This article surveys Chinese-language publications, U.S. government analyses, and related research, and applies it to a larger framework that addresses both conceptual and empirical issues, considers comparative cases, and offers suggestions for further examination. Its findings are relevant to scholars and practitioners alike: China’s military maritime power radiates outward, backstopped by a land-based “anti-Navy.” Its Navy focuses on proximate seas—supported by Coast Guard, Maritime Militia, and survey vessel fleets; and extends into the farthest oceans. China’s sea forces and the strategy informing them has become progressively less distinctive with time and distance—trends continuing today. Herein lies one of the greatest strengths, and limitations, of Beijing’s dramatic military maritime development.

China is going to sea powerfully, with tremendous implications for the nation, its neighbors, and the world. Understanding PRC military maritime advances requires understanding their ends, ways, and means. The ends are Beijing’s goals, the way is its maritime strategy, and the means are its sea forces.

For ends, China has since the end of the Cold War taken the grandest, most strategic approach of any great power. Ambitious paramount leader Xi wants to make China great again at home and abroad; achieve a “world-class military” with a similarly preeminent naval component; and incorporate claimed territories, above all, Taiwan.

For ways, China has a maritime strategy. Whether it constitutes part of a universal field of strategic thought, or should it be seen as a distinct intellectual tradition not easily mapped onto Western history and concepts, depends in part on how generally, or more specifically, one frames the question. I address this overarching comparison of Chinese and some foreign cases at a level of detail sufficient to understand PRC oceanic activities in practice—a level useful for scholars, strategists, and practitioners alike.

For means, China has three principal sea forces: the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)-controlled PLA Navy (PLAN), the People’s Armed Police (PAP)-controlled China Coast Guard (CCG), and the Militia-controlled People’s Armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM). Each is a component of China’s Armed Forces and exhibits distinctive “Chinese characteristics”—but all within a universal framework of examples that allows for a single, unified ecosystem of scholarly and analytical inquiry through comparing and contrasting. Broadly speaking, the PLAN is least distinctive, the PAFMM most distinctive. That, in turn, generates a key question I address subsequently: Within the PRC’s own historical context, do PAFMM and other PRC government activities at sea represent extant application of Maoist strategy, or have they evolved distinctively in their own context? Most pointedly, does China’s Maritime Militia practice “People’s War at Sea” today? This is strongly suggested in authoritative Chinese sources, and accepted as conventional wisdom by many Western observers—yet, as I will investigate and explain, the reality is far more complicated.

Were navalists to compile a high school-style yearbook, Beijing would receive “senior superlatives” across the board. While clearly still developing, in some ways awkwardly and contradictorily, China has already achieved manifold world-class maritime distinctions that no other nation—and, in some cases, combination of nations—can match. This in itself is significant and merits close examination. Increasingly numerous Chinese-language sources rightly describe China as a “hybrid” or “combination” “land-sea power” (Wu, 2014). Amid European decline and American fiscal and strategic challenges, this historic transformation has the potential to end six centuries of largely Western oceanic dominance.

From a world historical perspective, China has become only the third land power to achieve a genuine, enduring maritime transformation. It has turned seaward while shackled to geostrategic realities across sprawling hinterlands abutting diverse, difficult neighbors; hemmed in by “island chains” surrounding peripheral seas; and voluntarily pursuing the world’s most numerous, extensive disputed maritime and island/feature sovereignty claims—with the largest number of other parties—for decades. Indeed, China has marinized dramatically in both commercial and military dimensions, with scale, sophistication, and superlatives that no continental power ever before sustained in modernity.

China has achieved maritime milestones to the point that it rivals all other nations by many measures. Today China boasts the world’s largest: fishing fleet by boats and fishers, aquaculture and pisciculture industries, commercial fleet by shipping capacity, merchant marine, marine economic and industrial sector overall, and fleets of space support and oceanographic research vessels. A large nationally-flagged tanker fleet, global port infrastructure and logistics, and emerging overseas facilities likewise support PRC sea power.

China’s seaward surge is backed by firm leadership support and ambitious goals. The nation’s world-beating “blue economy” was decades in development. Now Xi is personally accelerating and heightening efforts across the waterfront to transform China into a “great maritime power.” China’s first full-fledged navalist leader, Xi rode into office in part on a rising tide of maritime emphasis. Following Deng’s economic renaissance and Jiang’s military reforms, Hu initiated significant seaward priorities and advancements.

In November 2012, at the 18th Party Congress that officially made Xi General Secretary, his outgoing predecessor passed him the torch by delivering its work report. Xi had participated in drafting this outline for the overall direction of policies for the next generation of leadership under him. “We should enhance our capacity for exploiting marine resources, develop the marine economy, protect the marine ecological environment, resolutely safeguard China’s maritime rights and interests, and build China into a maritime power,” Hu read from his valedictory report (Yamaguchi, 2016). The report also advocated “building a powerful maritime state” (Erickson, 2016, p. 80) and outlined a “‘maritime power’ strategy, calling for enhanced capacity for exploiting marine resources, protecting the marine environment and safeguarding China’s maritime rights and interests” (Xinhua, 2013).

By March 2013, Xi assumed all three offices of PRC paramount leader both determined to further China’s maritime interests and capabilities and unusually-well-placed to do so. PRC military experts credit Xi with emphasizing the “three at-seas.” Per this framework, “Threats to China’s national security are primarily at sea, the focus of military struggle is mainly at sea, and the center of gravity of China’s expanding national interests is at sea” (Martinson, 2022, p. 258). Accordingly, in April 2018 Xi declared, “the task of building a big and powerful People’s Navy has never been as urgent as it is today” (Liu L. and Chen W., 2018). Xi’s naval transformation is proceeding in parallel to continued expansion of PRC overseas interests: increasing citizen populations, investments, and assets abroad; as well as unprecedented levels of seaborne shipping of energy and resource inputs for PRC society and industry, and of the resulting products to overseas markets. All require increasing protection (Martinson, 2019a, 2020).

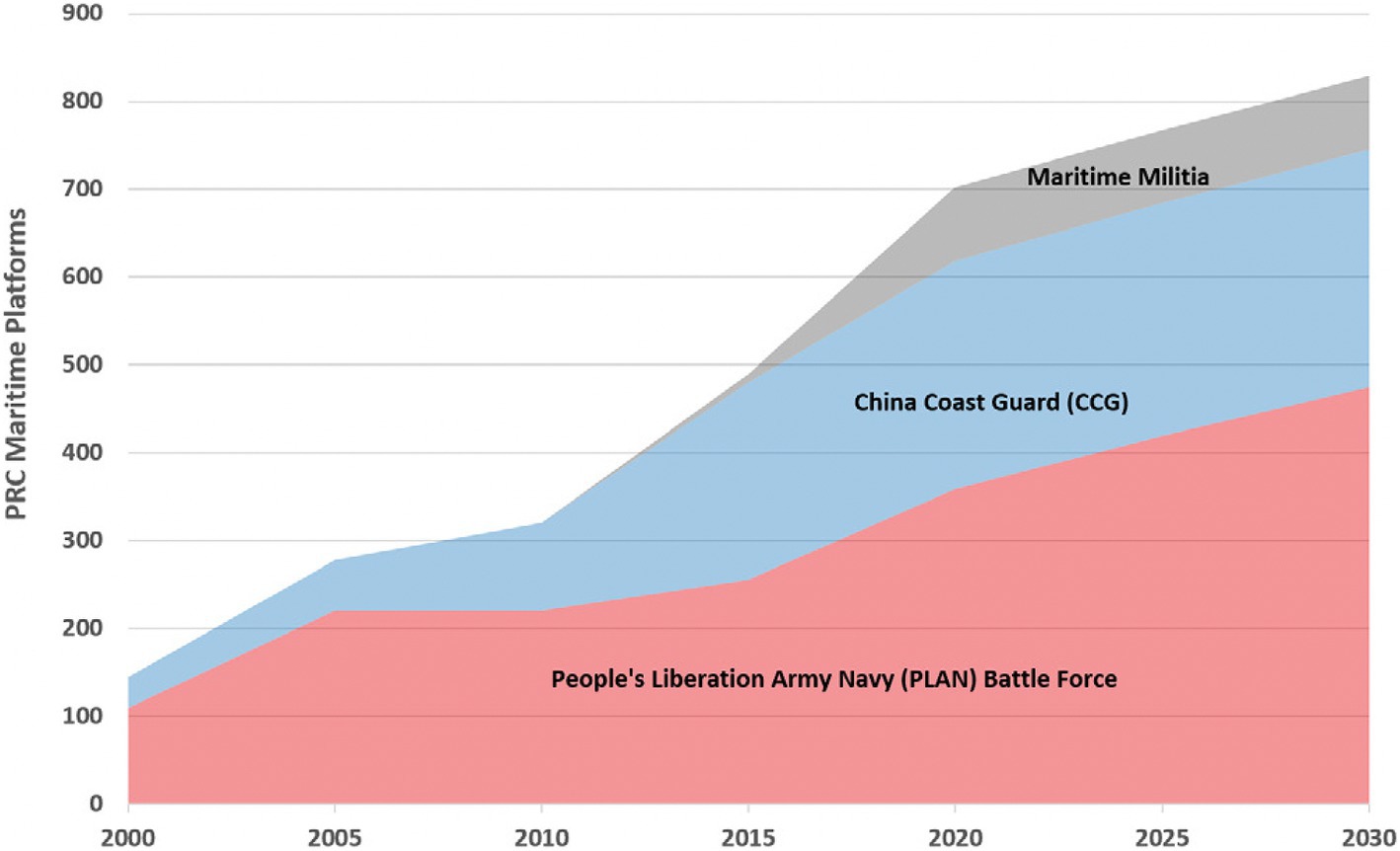

For two-plus decades, China has had the world’s second largest defense budget, funded by what is at least the world’s second largest economy. Among many other defense distinctions, this has generated the world’s largest sea forces by number of ships—Figure 1: the world’s largest navy, coast guard, and maritime militia—one of only two charged explicitly with furthering disputed sovereignty claims.

Figure 1. Growth of China’s maritime forces since 2000 (U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, 2020).

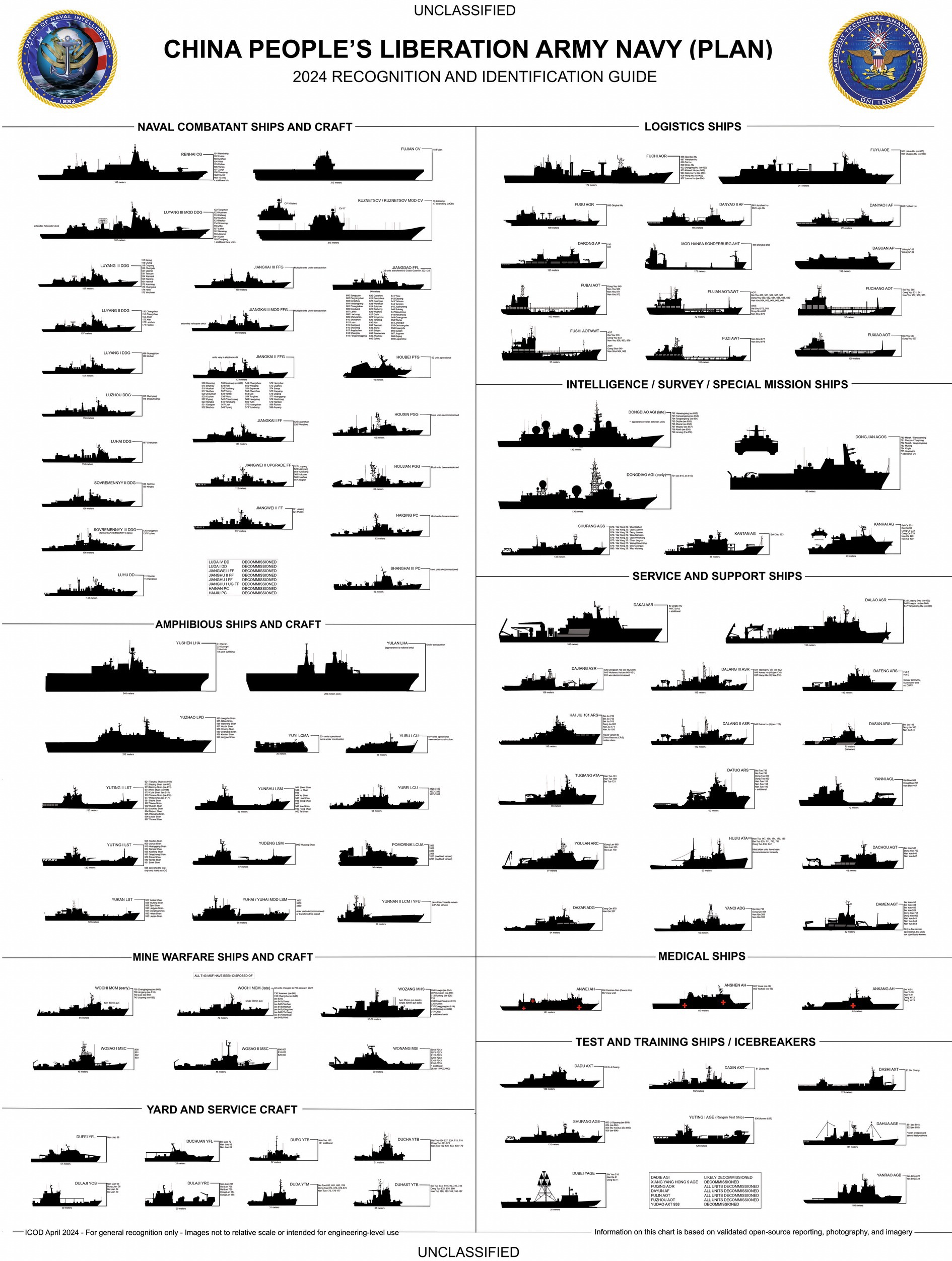

The PLAN already operates considerably more battle force ships than the U.S. Navy, making it the world’s largest naval fleet numerically at over 370 and counting (O’Rourke, 2024). The PLAN also includes the world’s most numerous conventional submarine force. The margin is likely to increase through this decisive decade as the world’s largest shipyard infrastructure continues to pursue the biggest, fastest production-capacity expansion since World War II and a buildout of naval power unparalleled in the modern era. The Pentagon anticipates 395 PLAN warships by 2025 and 435 by 2030 (Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2023, pp. 55–56). Figure 2 shows China’s navy force structure.

Figure 2. China’s naval vessels (Office of Naval Intelligence, 2024a).

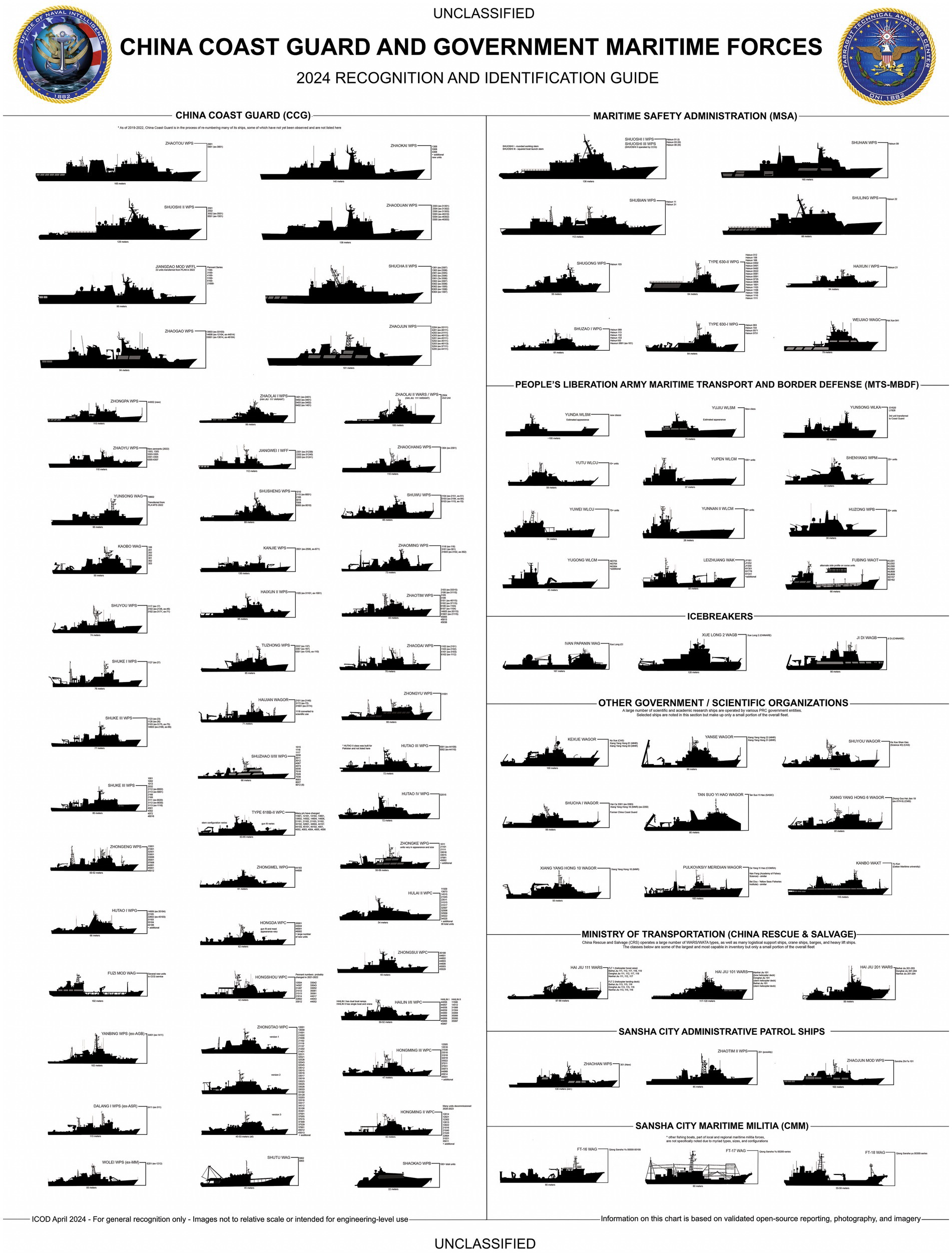

China has by far the world’s largest coast guard by number of ships; modernization and expansion continues expeditiously. The Pentagon tallies over 150 oceangoing and regional patrol vessels (WPS/~1,000+ tons), over 50 regional patrol combatants capable of limited offshore operations (WPG/~500–999 tons), and ~ 300 coastal patrol craft (WAG/~100–499 tons) (Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2023, pp. 79–80). While capabilities may overlap displacement categories (e.g., due to hull design or mission) and dramatic new commissionings are easier to track than unheralded decommissionings (particularly for smaller vessels), this is a formidable fleet by any measure. China boasts the world’s largest Maritime Law Enforcement (MLE) ships by size—two Zhaotou-class patrol ships with 10,000+ tons full load. China’s Coast Guard accepted 22 Jiangdao-class corvettes from China’s Navy in 2021 (Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2023, p. 56), and is receiving lightly-armed versions of PRC warships through a new large-ship construction program. The Zhaokai-class WPS is based on the Jiangkai II frigate (Ma, 2023; Sohu.com, 2023; 163.com, 2023), and a new WPS class is based on the Luyang III destroyer (Wang, 2024).

As its third sea force, China has the world’s largest maritime militia. It is virtually the only one charged with involvement in sovereignty disputes: only Vietnam, one of the very last countries politically and bureaucratically analogous to China, is known to have a similar force with a similar mission. The critical importance of the two nations’ 2014 HYSY-981 Oil Rig Incident to Vietnam’s interests, coupled with Vietnam’s inability to match China at sea despite its every incentive to do so and closer proximity to ports and supply lines, demonstrates PRC qualitative and quantitative superiority over Vietnam’s maritime militia (as well as its coast guard). Figure 3 shows China’s current Coast Guard force together with its most advanced Maritime Militia ships.

Figure 3. China’s coast guard and leading maritime militia vessels (Office of Naval Intelligence, 2024b).

PRC ship numbers matter. First, China increasingly enjoys both quantity and quality at sea. In recent years China has transcended Cold War shipbuilding that produced crude Soviet-style, post-World War II ship designs. The PLAN, naturally China’s most advanced sea force technologically, has most dramatically replaced dilapidated hulks with increasing numbers of sophisticated platforms. But the CCG and PAFMM are also modernizing significantly. Of China’s three sea forces, its coast guard has grown the most rapidly in numbers and enjoys the greatest global numerical superiority.

Numbers matter for maintaining presence and influence in vital seas. Even the most advanced ship cannot be ubiquitous. This is particularly true regarding the growing Sino-American strategic competition where Washington faces competing priorities and “tyranny of distance.” U.S. Coast Guard cutters are primarily focused near American waters, far from significant international disputes, while the U.S. Navy is dispersed globally. Meanwhile, all three major PRC sea forces remain focused above all on the contested Near Seas (Yellow, East, and South China Seas) and their immediate approaches, close to China’s homeland bases, and supported by short, interior supply lines and “anti-Navy” land-based air and missile coverage (Chaffin, 2012). There China regularly deploys sea forces far greater numerically than the size of the entire U.S. Navy.

Even as China’s maritime forces are making strides quantitatively, their most rapid progress has been qualitative. All told, in recent years, China’s maritime assets have transformed from an obsolescent mishmash to an increasingly integrated modern fleet with striking advantages in anti-ship missiles. Other aspects, such as organization and training, have improved apace. Certainly complexities and limitations remain, and PRC maritime development retains important differences from that of major long-established sea powers such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan.

China’s dramatic advances and world-leading seaward statistics demand explanation—what does all this mean, and what might it be for? PRC grand strategy and maritime strategy offer insights.

On October 28, 2017, at the 19th National Congress, Xi called for “realiz[ing] the Chinese Dream of national rejuvenation” with three major milestones: By the Party Centenary (2021), China should “finish building a moderately prosperous society in all respects.” By 2035, China should be much stronger economically and technologically, have become a “global leader in innovation,” and have completed its military modernization. By the PRC Centenary (2049), China should have “[r]esolv[ed] the Taiwan question” and be a “strong country” with “world-class forces” (Xi, 2017). To redouble development efforts, Xi subsequently added a midpoint to his 2035 midpoint: the Taiwan-centric Centennial Military Building Goal of 2027.

Operationalizing Xi’s grand strategy at sea is the role of Beijing’s maritime strategy. Focused almost exclusively on “coastal defense” from the founding of the People’s Republic through most of the Cold War, the PLAN did not even receive its first service-specific strategy (“Near Seas Defense”) until around 1985 (Liu, 2012). The 1995–96 Taiwan Strait Crisis and 1999 Belgrade Embassy Bombing catalyzed a concerted PLA(N) buildup that has yielded dramatic results. In the early 2000s, the PLAN’s mission set and scope began expanding to safeguard Beijing’s growing overseas interests as part of the PLA’s 2004 “new historic missions” under Hu. In 2015, the PLAN’s naval strategy officially expanded to “Near Seas Defense, Far Seas Protection” (Martinson, 2022).

Circa 2018, in a third layer of national and naval strategy, the PLAN’s strategic and operational writ was extended to all the world’s oceans. As part of these efforts, the PLAN has been transitioning to a still-more-extensive strategy: “near seas defense, far seas protection, (global) oceanic presence, and expansion into the two poles” (Yu, 2018; Martinson, 2019b). This latest, largest layer of PRC naval strategy and its operationalization remains ongoing. A China Central Television reporter’s interview of Yin Zhongqing, Deputy Chairman of the Finance and Economy Committee at the Thirteenth National People’s Congress, reveals similar language: “China must…do a better job protecting our territorial sea and controlling the Near Seas, enter the deep ocean, move toward distant oceans until we reach Antarctica and the Arctic….” (Xinhua, 2019).

Authoritative confirmation of specific aspects of Beijing’s maritime strategy and its operationalization may prove elusive. As Peking University professor Hu Bo explains, “China’s national government has never set forth a comprehensive list of its maritime interests, especially its core maritime interests. One reason for this is that China is developing too rapidly, so it is quite difficult to be certain of its interests, which are changing. Being intentionally vague will allow policy leeway in dealing with future uncertainties. Furthermore, vagueness also has some benefits of its own. Maintaining a vague position on the major issues of the East China Sea and the South China Sea is not only advantageous for flexibly handling maritime disputes with other countries, but also helps to ease potential pressure from domestic public opinion and reduce unnecessary policy risk” (Hu, 2015). This reality, combined with PRC propaganda obfuscation, generates confusion and unfounded “exoticization” of PRC maritime strategy and practice—by Chinese and foreigners alike. Nevertheless, scrutinizing Chinese-language sources rigorously elucidates the broader outlines of China’s maritime trajectory, which is hardly mysterious or entirely unique.

Scholarship and official PRC statements that depict PRC conceptions of “seapower” or “maritime power” as unique and exceptional are generally unconvincing (Zhang, 2015). Instead, rich veins of PRC neo-Mahanian scholarship demonstrate not only learning from earlier foreign thinking on sea power, but also that universal elements bespeak China’s own challenges—at least some of which overlap with those of other major powers that aspire to major sea power (China Ocean News, 2015).

To be sure, a distinctive “sabotage warfare” concept, with roots in People’s War tradition, regularly appears in official PLA doctrinal publications (e.g., Science of Military Strategy). However, this concept is typically explicated in laundry- or wish-list form; leaving unclear how precisely it might be operationalized; and how realistic it would be for the PLA(N), together with China’s armed forces overall, to do so in practice in key contingencies.

Taken together, what is particularly pronounced about PRC sea power today in both concept and practice is its multi-force, layered nature. As a team of PLAN and PLA researchers articulates, “China should comprehensively use various types of forces, combining the military, maritime law enforcement, and militia into a trinity” (Wu et al., 2015). PRC sources often refer to their combined operations as “joint military, law enforcement, and militia defense systems” or “three lines of defense”—respectively, Militia, Coast Guard, and Navy (Erickson and Kennedy, 2020).

The reason for China’s layered approach to maritime operations lies in an arguably pronounced version of a common pattern. Nations with significant forces and capabilities typically deploy them overlappingly in accordance with their roles and performance parameters, both to maximize capacity and options and to enhance reliability through redundancy. All coastal states use a layered approach to maritime security. Nearly all coastal states have both a coast guard layer and a navy layer. What makes China rare in the world (and unique as a great power) is that it has a third layer (the maritime militia). China’s survey vessel fleet under the Ministry of Natural Resources arguably constitutes a fourth layer. Such survey vessels are operating more frequently alongside the CCG and PAFMM in an attempt to advance PRC claims in the South China Sea.

China’s first white paper on military strategy (2015) explains how it emphasizes and employs its sea forces on a continuum from peace to war: “To implement the military strategic guideline of active defense in the new situation, China’s armed forces will adjust the basic point for PMS [preparation for military struggle]. In line with the evolving form of war and national security situation, the basic point for PMS will be placed on winning informationized local wars, highlighting maritime military struggle and maritime PMS” (PRC State Council Information Office, 2015).

To operationalize these efforts, “China should…expand, to the maximum extent possible, to the front lines of ocean defense and offshore islands/reefs…. China should build forward bases and support bases on islands/reefs in important geographic locations, and it should build a comprehensive supply system for large vessels and aircraft carrying out ocean defense tasks” (Wu et al., 2015). All this proceeds apace today.

China exhibits its greatest distinctiveness at sea along its immediate coastlines, in the Near Seas, and through using Maritime Militia to advance its sovereignty claims in these contested waters. China’s PAFMM is the “vanguard” frontline force in maritime gray zone operations, distinct from the “hybrid warfare” practiced by Russia.

Yale Law School scholar Peter Dutton offers the most comprehensive conceptual study of China’s maritime gray zone operations. China redefines contested waterspace’s legal status from foreign or international to “domestic, sovereign” space; and therein employs “non-militarized” coercion—typically involving CCG and PAFMM forces—to enforce as historically aggrieved defenders of PRC sovereignty and laws. China thereby eschews higher degrees of force in favor of longer periods of time (trading force for time) to erode opponents’ resistance while paradoxically imposing the burden of escalation on them and thereby complicating countermeasures (Dutton, 2022). Notably, rapid sea force expansion and increasing assertiveness in employment may suggest Xi’s impatience to recalibrate the force vs. time equation.

Today Vietnam is the only country besides China to have a significant-sized, similarly-tasked Maritime Militia—a parallel stemming from Beijing and Hanoi’s shared Leninist political system. Tellingly, China and Vietnam have waged their own gray zone contest—the 2014 HYSY-981 Oil Rig Incident, subsequently addressed in greater detail. Despite being highly motivated, particularly given the encroachment on its claimed Exclusive Economic Zone, Vietnam was outclassed and overcome, refuting repeated PRC public claims that Vietnam’s Maritime Militia is stronger than China’s (Thorne and Spevack, 2019).

Does China’s Maritime Militia currently practice People’s War at Sea—a maritime extension of Maoist guerilla warfare mobilizing locally-supported “armed civilians” for coastal defense in depth? Bottom line: Not really, particularly in peacetime. Drawing on storied achievements of seven decades ago, some PRC sources today describe PAFMM gray zone (“rights protection”) missions as “People’s War at Sea.” As Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments scholar Toshi Yoshihara documents, the nascent PLAN waged its 1949–50 island seizure campaigns against Kuomintang (KMT) forces not in miniature emulation of the Soviet “Young School,” but rather innovated to address its own coastal warfare challenges in ways that shape its institutional identity to this day. While technological and ideational independence from Soviet assistance may be exaggerated in subsequent PLAN panegyrics, insistence by PRC naval progenitors—foremost among them inaugural PLAN Commander Xiao Jinguang—that “material factors had to conform to China’s unique strategic circumstances” indeed yielded “a distinctive Chinese way of warfare” that included a doctrine of “sabotage warfare at sea” (Yoshihara, 2023, p. 5).

These formative fundaments are “still visible in the Chinese naval force structure today,” particularly in “conventional submarines, shore-based aircraft, and coastal combatants” (Yoshihara, 2023, p. 5), as well as emphasis on small paramilitary and “civilian” ships. Today the CCG and PAFMM, as well as civilian ferries and other auxiliary vessels (Dahm and Kennedy, 2021), potentially crewed by militiamen, clearly echo this “hodgepodge force” with a “small-ship ethos” on a scope and scale not found in any other nation’s maritime forces (Yoshihara, 2023, p. 6). As Yoshihara rightly emphasizes, “the conscription of the merchant and fishing fleets suggests that the civil-military integration of maritime power dates back to the earliest days of the PLAN. In light of this history, perhaps it is not surprising that China has been so adept at seamlessly employing a combined fleet of naval combatants and civilian maritime law enforcement vessels in recent years” (Yoshihara, 2023, p. 119).

The PLA’s 1949–50 offshore campaigns clearly operationalized core elements of People’s War. Securing local support in mobilizing junks and boatmen, together with fishing communities’ deep knowledge of terrain, currents, and weather, proved pivotal to the CCP’s pursuit of KMT-held islands (Yoshihara, 2023, pp. 121–22). When the PLA coordinated such local support well, it typically won; when it fell short, it typically lost. Creatively motorizing junks and retrofitting them with army artillery arguably reverberates in recent retrofitting of PLA-mobilizable ferries with ramps (Kennedy, 2021). Echoes of these pioneering examples of People’s War at Sea may be found in the 1955 Yijiangshan Campaign, the 1965 “86 Sea Battle,” and the 1974 Paracels Sea Battle (Yoshihara, 2023, pp. 143–44; Yoshihara, 2016).

During this period, Mao succeeded in promoting People’s War over the objections of Peng Dehuai and other Party leaders who favored a more professional, Soviet-style military approach. Mao was similarly successful in overcoming opposition to extending his doctrine seaward. Despite the lack of masking terrain and landed inhabitants there, Mao insisted: “The navy has its own characteristics, but we cannot emphasize the navy’s specialness. We must carry forward the army’s good traditions. We cannot toss them aside. The navy must also rely on the people; it must rely on fishermen. It must plant roots among the fishermen” (Zhan, 2009; Rielage and Strange, 2019, p. 41). The initial decades of PAFMM development in the People’s Republic were a clear beneficiary of Mao’s People’s War doctrine.

Throughout this Cold War era, Taiwan proved completely beyond the reach of People’s War at Sea. This was because of severe PLA(N) limitations that left even the victories Yoshihara chronicles a close-run thing; the far wider geographic scope of the Taiwan Strait than the often literally-just-offshore battles of 1949–50 and in subsequent years; and the lack of Fifth Column forces on Taiwan even remotely equivalent to the Qiongya Column, in development since the 1920s, that greatly facilitated PLA conquest of Hainan in 1950 (Yoshihara, 2023, pp. 90–105).

What, then, post-1974 and post-Cold War? Attempting to trace these undeniable antecedents to present practice yields severely diminishing returns. Drawing in part on the proud history that Yoshihara documents, PLA(N) leadership sometimes invokes People’s War at Sea symbolically to encourage PLA-CCP political connectivity and stimulate PAFMM development and operations—but the concept appears far more marginal, peripheral, tangential, and uneven in practice. At most, it is a convenient, politically-correct catch-all filling a terminological vacuum left by the lack of a single enduring overarching concept to describe PAFMM support of PRC maritime “rights and interests” (Rielage and Strange, 2019, p. 47). Vessel-invoking virtue signaling, as it were.

Despite searching carefully in such key locations as PRC Defense White Papers, the official PLAN newspaper People’s Navy, and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) electronic database, a dedicated study found few mentions of People’s War at Sea in PRC strategic discourse (Rielage and Strange, 2019, p. 43). The present author’s subsequent survey of recent Chinese writings on PLAN strategy and the PAFMM, and the continued paucity of such findings in CNKI, further suggests that there is not much discussion of People’s War at Sea these days—let alone substantive doctrinal operationalization. A previously-cited article by a team of PLAN and PLA researchers discussing “Chinese Ocean Defense” contains brief mention of “People’s War” in the context of maritime administrative control, but without much explanation (Wu et al., 2015). In a PLA Academy of Military Science-published article, PLAN authors discuss China’s naval strategy’s evolution and development, likewise without mentioning People’s War (Liu L. and Chen W., 2018). Two authors, at least one with direct knowledge of PAFMM force development, consider the force’s role in warfighting, with no mention of People’s War (Liu Z. and Chen Q., 2018). PLAN professors at the Naval Command College survey the Navy’s strategic roles, with no mention of People’s War (Shi and Chen, 2018). Two PLA Naval Research Institute authors address PLAN strategic requirements and future roles, with no mention of People’s War (Yang and Yang, 2019).

Several pedigreed twenty-first-century Chinese-language sources discuss People’s War at Sea in the context of naval strategy. Zhejiang Provincial Military District’s Commander examines People’s War at Sea (Yuan, 2002). Two PLA Army Command College military scholars probe People’s War under informatized conditions (Wang and Yang, 2009). Two PLAN Command College authors address the use of Maoist Thought to inform People’s War under Informatized Conditions, with some explication of Far Seas deployments and using “civilian” forces to support them (You and Chen, 2010). The strongest single-author source the present author and his colleagues have located is a 2014 article—a Nanjing Military Region Mobilization Department head offers several inputs regarding a People’s War at Sea in both peacetime and wartime (Ge, 2014). The best recent source known to the author and his colleagues that addresses the topic directly is from officers at the Eastern Theater Command Political Work Department’s Mass Work Liaison Department in 2017. They deliberate dealing with the “strong enemy”—a stock reference to the United States (Liang and Huai, 2017).

While not exhaustive, this representative mix of curated Chinese-language sources strongly suggests that it is not mainstream to discuss People’s War in the context of naval strategy. It is still discussed in other contexts—specifically by military officers involved in mobilization work—since it is their job to frame things this way. While some might argue that in certain ways PAFMM gray zone activities resemble People’s War at Sea, this term does not in fact usefully describe the PAFMM’s role in PRC dispute strategy. Rather, leaders and strategists are repackaging this concept for political reasons.

To the continually-lessening extent that the concept of People’s War at Sea is used in demonstrably authoritative sources, it describes not peacetime rights protection operations but rather wartime doctrine. And even to the extent that People’s War at Sea can be said to remain a substantive doctrinal concept in some specific applications therein—such as certain wartime operations for which PAFMM forces are authoritatively documented to train—it remains uncertain how reliable or effective such measures would prove in practice.

Wartime roles advocated by PAFMM sources—such as generating false targets—may sound potent on paper (Liu Z. and Chen Q., 2018), but could prove extremely difficult to achieve—and that is even assuming that PAFMM personnel would be willing and able to perform their roles in situations imposing tremendous casualty rates and confusion in the fog of actual war.

Comparing China’s Coast Guard to other nation’s equivalents reveals aspects of both distinctiveness and symmetry. Both China’s and Vietnam’s Coast Guard-type forces participated in the HYSY-981 Oil Rig Incident. The CCG differs from counterparts in many other developing countries (e.g., Indonesia) in its ultimately successful multi-stage consolidation of the vast majority of its MLE forces into a single Coast Guard. It differs from all other Coast Guard/MLE forces in sheer ship numbers. The CCG differs from that of the United States in its extensive missioning and activities to advance disputed sovereignty claims in Beijing’s favor, but appears—unique among formerly “continental” and “developing” nations—on the verge of overlapping with its American counterpart in assuming extra-regional roles.

As New Zealand sinologist Anne-Marie Brady documents, in 2024 Beijing unprecedentedly “registered 26 China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels to operate in the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission Convention Area. The Convention manages 20 percent of the globe, from the Aleutians in the North Pacific, all the way down to the Southern Ocean. It is also the area of the First, Second, and Third Island Chains. The CCG…will soon legally be allowed to board any foreign fishing vessels on the high seas in the First, Second, and Third Island Chains” (Brady, 2024).

This is a dramatic development: “Since 2020, China has also had four Coast Guard vessels registered to monitor foreign fishing vessels in the North Pacific Fishing Commission Area. Starting from June this year, China will have the third largest maritime security presence patrolling throughout the whole of the Pacific, after the United States and Australia” (Brady, 2024).

Rather than operating on exterior lines like such geographically advantaged sea powers as the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Australia, China must radiate sea power from interior lines in a way that prioritizes increasing control over its disputed Near Seas sovereignty claims while seeking growing influence across the Indo-Pacific region and nascent global presence. To pursue these radiating ripples of maritime interests and activities, PLAN forces and operations have exhibited both potent emphasis on anti-surface missile firepower and lingering limitations as part of their Soviet/Russian legacy.

Moving forward and expanding globally, however, the PLAN is striving increasingly toward American-benchmarked force structure and capabilities. As two PLAN researchers explain, “On April 12, 2018, Xi Jinping attended the naval parade in the South China Sea, during which he called for [the service to] ‘strive to comprehensively build the People’s Navy into a world-class navy.’” They elaborate: “the only way to consider oneself a world-class navy is to have the power to match, contend with, square off against any opponent; deter and win possible maritime conflicts; and forcefully support the country’s status as a world-class great power” (Liu L. and Chen W., 2018). As both Chinese sources and actions indicate, the preeminent navy Xi seeks is increasingly converging on the world-leading U.S. Navy in terms of hardware and fleet composition, albeit pursuing a somewhat different mission set for the foreseeable future.

PLAN operations remain limited by China’s historical lack of robust overseas bases, but an array of overseas port investments and access arrangements that have helped to support the PLAN’s forty-six-and-counting task force deployments to the Gulf of Aden and beyond since December 26, 2008 are partially compensating (China Military Online, 2024). Moreover, China is now developing a more robust network: having established its first PLA Support Base, or “overseas strategic strongpoint,” in Djibouti in 2017, China now enjoys a similar arrangement in Ream, Cambodia (Dutton et al., 2020). Consideration of roughly 19 other potential locations is reportedly underway (Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2023, pp. 154–55).

Here Far Seas requirements (e.g., large surface combatants vulnerable to “anti-Navy” forces) may conflict with Taiwan-centric Near Seas mission requirements (e.g., more amphibious lift and better submarines to challenge American intervention). PRC naval circles have long debated potential tradeoffs. Renmin University professor Wu Zhengyu argues that China lacks the resources to pursue both options simultaneously, and faces critical choices:

“…China, as a continental power with extensive land and sea frontiers, cannot afford to prioritize building and maintaining a [U.S. Navy]-style blue water navy and global network of overseas bases in the long term. First, China today, albeit experiencing better border security than any previous time, still faces a range of tricky challenges. China has 14 land neighbors, and four of them with nuclear weapons. Furthermore, many Chinese border regions are occupied by disaffected minorities that have constantly sought independence. Accordingly, China’s vast hinterland requires large land forces to maintain the domestic stability. Such demands would surely divert resources away from naval development. Second, to construct and defend a Mahanian blue water navy and a global network of military bases, China must not only expend great effort in naval buildup, but also press ahead with space, air, cyber capabilities. This tremendous development requires time, resources, strong will, good luck, and prodigious budgets. Such comprehensive efforts would put insufferable burden on China’s national economy which has been slowing down over last few years. Given China’s endowments, the only chance for the PLAN to compete with the USN lies with the asymmetric approach, that is, with developing A2/AD capabilities and improving its geostrategic position” (Wu, 2019).

China’s maritime ends, ways, and means are not teleological. Given such challenges, the PLAN’s Far Seas trajectory remains uncertain.

The foregoing examination of PRC maritime strategic culture in comparative context suggests several areas for follow-on research. Two cases offer distinctive examples inherently important to international maritime security issues today in two confined, contested bodies of water: the South China Sea and the Arabian Gulf.

First, might China’s multi-sea force success inspire attempts at emulation; particularly of its most affordable, low-profile, and distinctive element: the Maritime Militia? Potential emergent cases remain a subject of speculation given insufficient reliable data; by contrast, Vietnam is an understudied, yet empirically rich extant case.

Only Vietnam, one of the very last countries politically and bureaucratically similar to China, is known to have a similar force to China’s PAFMM, with a similar mission of involvement in sovereignty disputes. This stems from their political system: other countries do not formally employ maritime militias because only authoritarian countries could deploy such a force while attempting to shroud it in “plausible deniability” (Erickson, 2018). The maritime militias of China and Vietnam were originally organized and tasked similarly as elements of their respective nations’ armed forces.

Hanoi’s detailed 1999 “Law on Militia and Self-Defense Forces” states: “Militia and self-defense forces are mass armed forces not detached from production and work and constitute a part of the people’s armed forces of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. …Marine militia and self-defense force means a force within the core militia and self-defense force organized in coastal communes, island communes and in agencies and organizations with vessels operating at sea to perform tasks on Vietnam’s sea areas.” Article 8 stipulates: “Tasks of militia and self-defense forces” include “To stand ready for combat, to combat and render combat services to defend their localities and workplaces; to collaborate with border guard, navy and marine police units and other forces in defending the national sovereignty and border security and the sovereignty and sovereign rights on Vietnam’s sea areas.” As for their structure, “In coastal and island communes, marine militia squads or platoons shall be organized…. Agencies and organizations shall organize self-defense squads, platoons, companies or battalions. Those with vessels operating at sea shall organize marine self-defense squads, platoons, flotillas or fleets” (Erickson, 2018).

This content is similar to that of China’s Regulations on Militia Work, promulgated by the State Council and Central Military Commission on December 24, 1990 to replace the previous regulations of August 1978 and implemented on January 1, 1991. Article 33 states that “Militia organizations in land-sea frontier defense areas and other key combat readiness areas should, in accordance with the requirements of higher-level military organs, carry out joint defense with the PLA and the People’s Armed Police forces stationed in the area” (Erickson, 2018). China’s PAFMM is a set of mariners and their vessels that are trained, equipped, and organized directly by the PLA’s local military commands. While at sea, these units typically answer ultimately to the PLA chain of command, and are certain to do so when activated for missions. “The Eastern Theater Command also likely commands all CCG and maritime militia ships while they are conducting operations related to the ongoing dispute with Japan over the Senkaku Islands,” the Pentagon specifies (Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2023, p. 119). Through these practices, China is taking its third sea force to a level unmatched by any other country—even Vietnam.

That top-level officials from both countries have visited their respective leading sovereignty-supporting fishing groups demonstrates the importance that they accord these forces. The context in which they have done so, however, suggests PRC qualitative and quantitative superiority. In April 2013, Xi visited the Tanmen Maritime Militia Company on the first anniversary of its frontline participation in the Scarborough Shoal Incident (Kennedy and Erickson, 2016a), in which PAFMM forces supported CCG vessels in seizing the resource-rich feature from the Philippines. The following year, the Tanmen Maritime Militia contributed to the defense of China’s HYSY-981 oil rig against Vietnamese efforts to pressure its removal from disputed waters from May 2–July 15, 2014. That July, in Danang, Vietnamese President Trương Tấn Sang visited “25 fishing vessel owners who are participating in… protecting sovereignty over the Paracels” (Erickson, 2018) and “resolutely fought for the withdrawal of [China’s 981 oil rig].” He conferred gifts on the owner of fishing vessel ĐNa 09152 (Buu, 2014), which had been rammed and sunk on May 26, 2014 (Soha.vn, 2015) by its Chinese counterparts, as one of up to two dozen Vietnamese vessels reportedly damaged.

The HYSY-981 Oil Rig Standoff was arguably strategically problematic for China, because Vietnam was able to make drilling in the rig’s location economically unviable, causing China to relocate it and ultimately remove it. As China’s largest, most sophisticated tri-sea-force operation to date, it was also potentially an opportunity for further operational learning on China’s part. Nevertheless, despite emulating China’s gray zone approach, Vietnam was outclassed by China’s sheer fleet size and capabilities. The event’s critical importance to Vietnam’s interests, coupled with Vietnam’s shortfall despite closer ports and supply lines, demonstrates PRC qualitative and quantitative superiority over Vietnam’s coast guard and maritime militia.

Available Chinese and Vietnamese sources agree the latter was overmatched 2:1. China maintained 110–15 vessels (Kennedy and Erickson, 2016b) around the rig in a cordon of ~10 nautical miles. It mustered and maintained roughly two times the maritime presence of Vietnam, leaving the latter no way to penetrate the defensive layers enveloping the rig (without the use of deadly force, at least). Four PLAN vessels reportedly participated, as did 35–40 Coast Guard vessels. The more than 40 PAFMM vessels included 29 from Sanya, 10 from Tanmen, and others from such locations as Dongfang City (Erickson, 2017).

Currently, in an important and apparently growing Sino-Vietnamese disparity, maritime militia development and employment appears to be less important to Vietnamese than Chinese maritime doctrine. Unlike China’s flourishing multirole PAFMM, there is little evidence that Vietnam’s maritime militia units retain major functional use today beyond apparent intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance roles. Like China, Vietnam is rapidly expanding its official Fisheries Resource Administration and Coast Guard fleets. Both have roughly doubled in size over the past decade, in a clear attempt to address China’s maritime expansion. During this time, Vietnam’s Coast Guard has received U.S. Hamilton-class cutters, several dozen new large patrol ships, and many new-build patrol craft. Vietnam’s navy is perhaps even further behind China’s, both qualitatively and quantitatively. That Vietnam can grow and employ its fleets so earnestly yet still be so far behind China is further testimony to Beijing’s growing overmatch against its neighbors at sea.

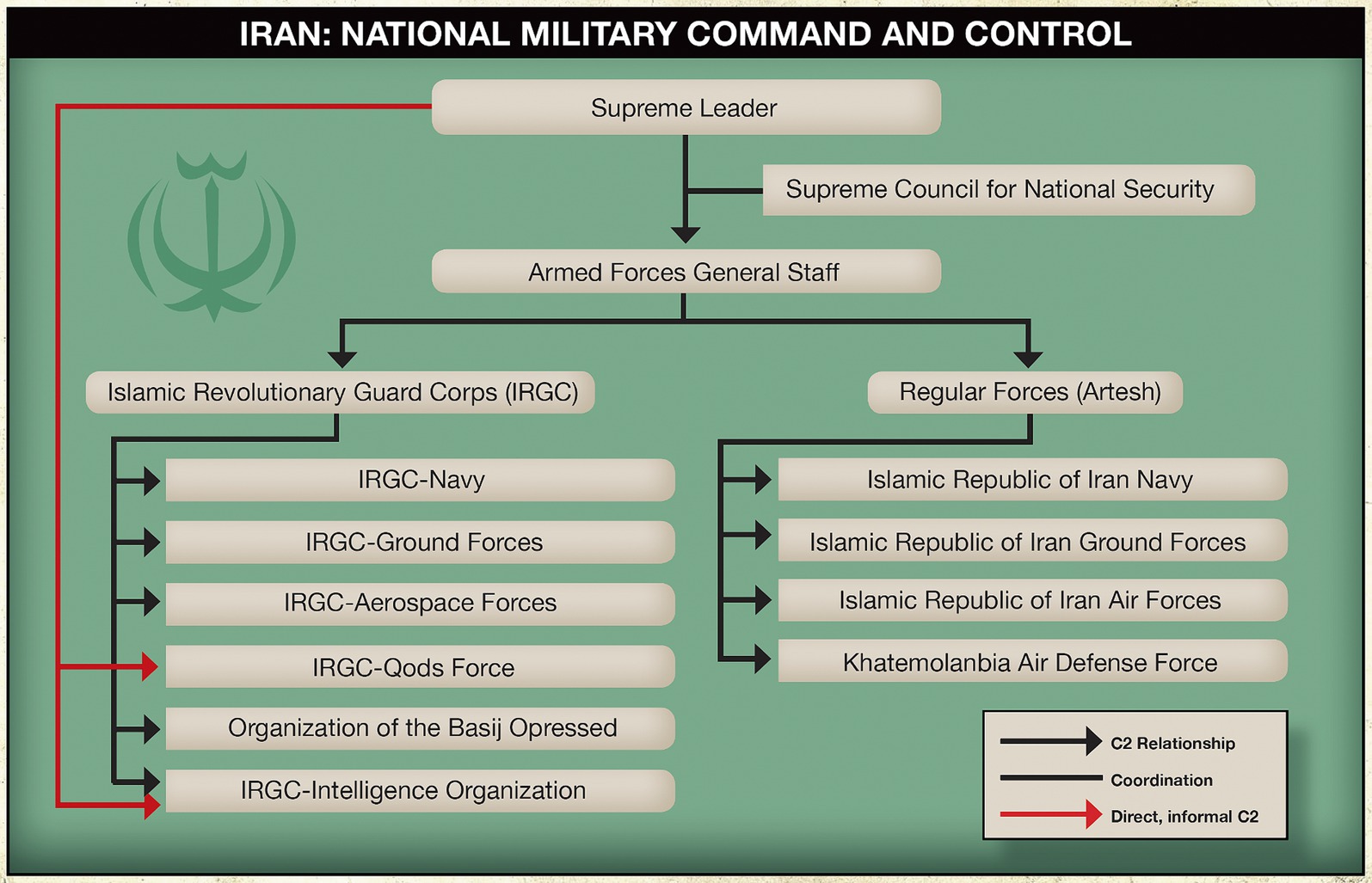

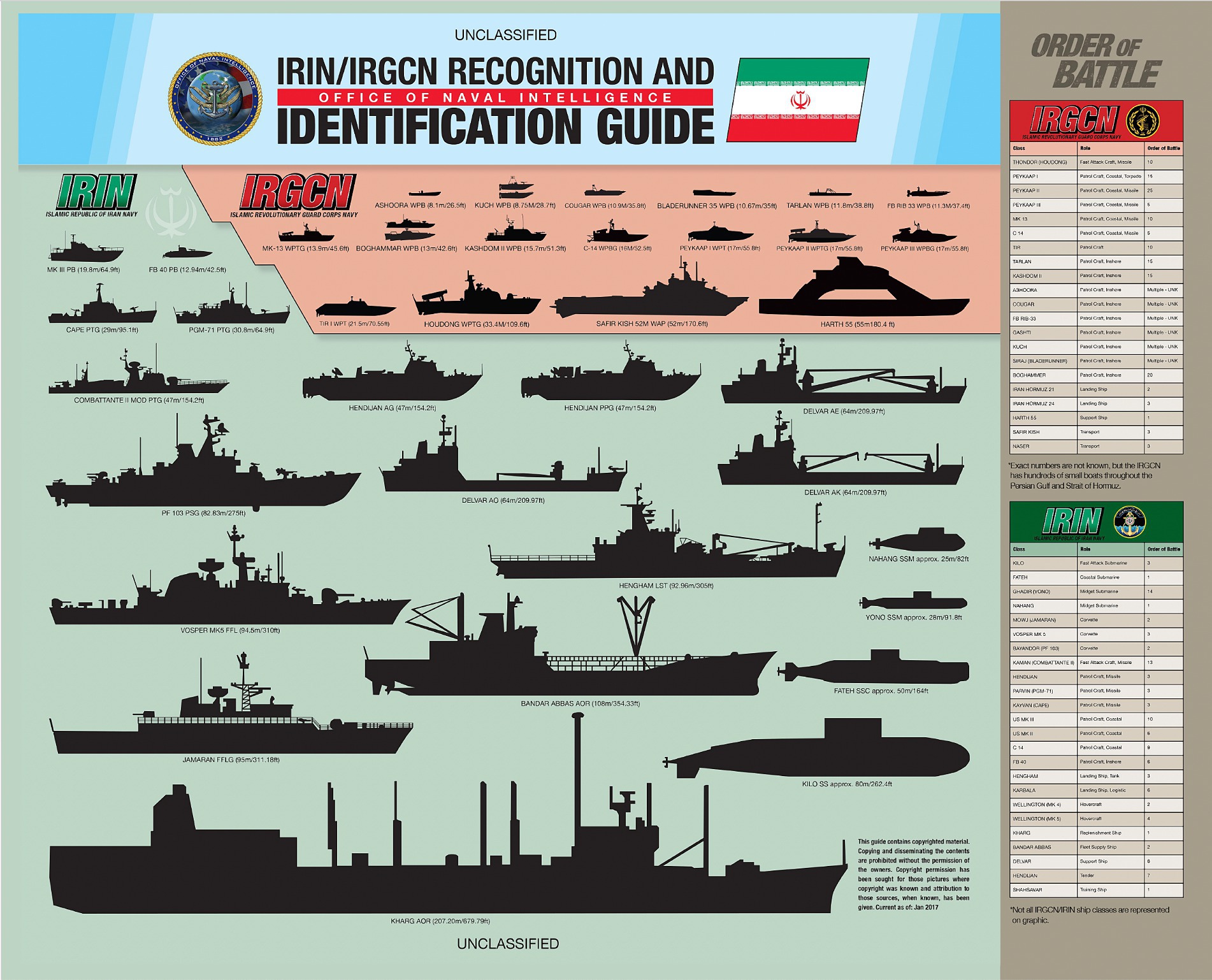

A second understudied, but empirically important and potentially revealing area of follow-on research concerns the sea services of Tehran and its clerical regime: the Islamic Republic of Iran Navy and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Navy. These are even more distinctive than PRC sea forces, at least in their command and control; akin to if China had separate Party and State navies. Figure 4 shows the dual organizational structure for Iran’s dual navies.

Figure 4. Command and control of Iran’s two navies (Office of Naval Intelligence, 2017, p. 14).

While many dictatorships and other authoritarian states have multiple overlapping, or even competing, land forces—including loyalist praetorian guard forces tasked with ensuring leadership continuity above all else—Iran is the only country to have such politically competing, operationally overlapping forces at sea. Figure 5 shows the ships of Iran’s two navies.

Figure 5. Iran’s two navies (Office of Naval Intelligence, 2017, p. 35).

Understanding China’s military maritime juggernaut requires asking: to what ends, in what ways, by what means? Asserting control over Taiwan and other disputed Near Seas sovereignty claims is clearly prioritized, but beyond that China’s course at sea becomes less distinct and more complex. All told, the “uniqueness” of China’s approach at sea is stratifying further: Maritime Militia distinctiveness, partial Coast Guard overlap, and growing Navy convergence.

So much depends on framing. PRC maritime strategy and its operationalization, of which naval strategy and practice is a subset, fits within the overall Western/global ecosystem of maritime strategic concepts; yet within this universal context also exhibits distinctive patterns of “Chinese characteristics” that differentiate it from Western counterparts in both emphasis and operationalization. Within China’s own context, the patterns vary significantly by sea force and area of operations. Put simply, Chinese maritime distinctiveness diminishes with time and distance. PAFMM missions and operations exhibit pronounced PRC particularities—even as these distinctions have evolved over time. CCG missions and operations exhibit both idiosyncrasies and more universal attributes.

In the naval domain, China’s formative foundation might be termed “continentalist” in nature—although China has long had major maritime fundaments, too. However, the most relevant set of comparative cases may be among land powers that have attempted seaward reorientation. Arguably, China is now a hybrid “land-sea” power—having completed the first such sustainable maritime transformation since the Persian and Roman Empires two millennia ago. China is surging seaward for the first time in six centuries; having dominated the seas for the same period, the traditional Western powers have largely retreated, or are ebbing away, from ambitious maritime postures. Only the United States holds firm to its status as a global sea power, but it faces age-old, unrelenting challenges.

No former “continental” power can fully transcend landward interests and liabilities, or abandon strengths interior lines afford. Hence, China unsurprisingly manifests today as a maritime power with “Chinese characteristics.” This includes having the world’s largest armed forces’ ship numbers, but layered geographically among three major sea forces—with China’s navy now ranging the globe. China’s sea forces radiate out increasingly within their respective realms, but are strongly supported by a land-based “anti-Navy,” centered on the world’s largest conventional ballistic and cruise missile forces—and backstopped by nuclear forces that are already the world’s third-largest after Russia and the United States at over 500 warheads, with 1,500 warheads projected by 2035 (Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2023, p. 111).

Neither China’s maritime strategy nor its sea forces are entirely unique or unprecedented, at least above a certain level of generalization. They may usefully be compared and contrasted within a universal set of literatures, concepts, metrics, indicators, and historical analogies. But all told, China’s maritime strategy and practices are certainly exceptional and powerful in aggregate today, where it all comes together at sea. The impact on other nations’ strategies and policies is great already. Rather than simply being captured by time and tides beyond its control, Beijing is clearly making its own major waves, which will surely shape the shores of history.

AE: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of his affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The views expressed here are the author’s alone. All Chinese- and Vietnamese-language sources are presented in translation. In addition to original Chinese-language sources, he has consulted more than 140 translations performed by Professors Ryan Martinson and Conor Kennedy, as well as other colleagues at the China Maritime Studies Institute; some are cited here. Erickson is further indebted to Martinson, Kennedy, and the reviewers for helpful inputs.

163.com . (2023). How much impact will it have if 10 type 054A coast Guard ships joined the China coast Guard? Available at: https://www.163.com/dy/article/IMLDRLEH0523RGK4.html (Accessed December 23, 2023).

Brady, A-M . (2024). Facing up to China’s hybrid warfare in the pacific. The Diplomat. Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2024/06/facing-up-to-chinas-hybrid-warfare-in-the-pacific/ (Accessed June 3, 2014).

Buu, L. (2014). President: “Fishermen should rest assured to stick to the sea and maintain sovereignty.” VTC News. Available at: https://vtc.vn/chu-tich-nuoc-ngu-dan-hay-yen-tam-bam-bien-giu-chu-quyen-d162663.html

Chaffin, G. (2012). Building an active, layered defense: Chinese naval and air force advancement—an interview with Andrew S. Erickson. National Bureau of Asian research. Available at: https://www.nbr.org/publication/building-an-active-layered-defense-chinese-naval-and-air-force-advancement/ (Accessed September 10, 2012).

China Military Online . (2024). 46th Chinese naval escort taskforce completes first escort task. Available at: http://eng.mod.gov.cn/xb/News_213114/OverseasOperations/16293045.html (Accessed March 11, 2024).

Dahm, M, and Kennedy, C. (2021). Civilian shipping: ferrying the People’s liberation Army ashore. Center for International Maritime Security. Available at: https://cimsec.org/civilian-shipping-ferrying-the-peoples-liberation-army-ashore/ (Accessed September 9, 2021).

Dutton, P. (2022). “Conceptualizing China’s maritime gray zone operations” in Maritime gray zone operations: Challenges and countermeasures in the Indo-Pacific. ed. A. Erickson (New York, NY: Routledge), 19–34.

Dutton, P., Kardon, I., and Kennedy, C. (2020). Djibouti: China’s first overseas strategic strongpoint, China maritime report 6 (Newport, RI: naval war college China maritime studies institute, April 2020). Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/6/ (Accessed April 3, 2020).

Erickson, A. (2016). “China’s naval modernisation, strategies, and capabilities” in International order at sea: How it is challenged. How it is maintained. eds. J. I. Bekkevold and G. Till (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 63–92.

Erickson, A. (2017). China open source example: proposal to Hainan government reveals maritime militia activities. China Analysis from Original Sources. Available at: http://www.andrewerickson.com/2017/02/china-open-source-example-proposal-to-hainan-government-reveals-maritime-militia-activities/ (Accessed February 7, 2017).

Erickson, A. (2018). Numbers matter: China’s three “navies” each have the world’s most ships. The National Interest. Available at: https://nationalinterest.org/feature/numbers-matter-chinas-three-navies-each-have-the-worlds-most-24653 (Accessed February 26, 2018).

Erickson, A., and Kennedy, C. (2020). “Appendix II—China’s maritime militia: an important force multiplier” in China as a twenty-first-century naval power: Theory, practice, and implications. ed. M. McDevitt (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press), 220.

Ge, Y. (2014). A few thoughts on winning the maritime people’s war in the new era. National Defense 12, 65–67.

Hu, B. (2015). On China’s important maritime interests. Asia-Pacific Security and Maritime Affairs 3, 125–126.

Kennedy, C. (2021). Ramping the strait: quick and dirty solutions to boost amphibious lift. Jamestown China Brief 21.14. Available at: https://jamestown.org/program/ramping-the-strait-quick-and-dirty-solutions-to-boost-amphibious-lift/ (Accessed July 16, 2021).

Kennedy, C, and Erickson, A. (2016a). Model maritime militia: Tanmen’s leading role in the April 2012 Scarborough shoal incident—part 1. Center for International Maritime Security. April 21. Available at: http://cimsec.org/model-maritime-militia-tanmens-leading-role-april-2012-scarborough-shoal-incident/24573 (Accessed April 21, 2016).

Kennedy, C, and Erickson, A. (2016b). From frontier to frontline: Tanmen Maritime Militia’s leading role—part 2,” Center for International Maritime Security. May 17. Available at: https://cimsec.org/frontier-frontline-tanmen-maritime-militias-leading-role-pt-2/ (Accessed May 17, 2016).

Liang, Q., and Huai, Q. (2017). Deeply preparing for people’s war mobilization in response to local wars in the maritime direction. National Defense 9, 21–24.

Liu, Z. (2012). A study of maritime strategic thoughts of Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, and Jiang Zemin. China Military Sci., 2, 52–59.

Liu, L., and Chen, W. (2018). Theoretical development of naval strategy since reform and opening up and implications for today. China Military Sci. 6, 59–65.

Liu, Z., and Chen, Q. (2018). Tasks and operations of the maritime militia when participating in maritime combat. National Defense 11, 50–51.

Ma, H. (2023). A coast Guard ship put into use, patrolling and enforcing the law to safeguard sovereignty. https://www.takungpao.com/news/232108/2023/1218/924246.html (Accessed December 18, 2023).

Martinson, R. (2019a). China as an Atlantic naval power. RUSI Journal 164.7. https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/rusi-journal/china-atlantic-naval-power (Accessed December 18, 2019).

Martinson, R. (2019b). The role of the Arctic in Chinese naval strategy. Jamestown China Brief 19.22. https://jamestown.org/program/the-role-of-the-arctic-in-chinese-naval-strategy/ (Accessed December 20, 2019).

Martinson, R. (2020). Deciphering China’s “world class” naval ambitions. U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2020/august/deciphering-chinas-world-class-naval-ambitions (Accessed August 1, 2020).

Martinson, R. (2022). China’s oceanic aspirations: new insights from the experts. Orbis 66.2. 249–269. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0030438722000126 (Accessed February 1, 2022).

O’Rourke, R. (2024). China naval modernization: Implications for U.S. navy capabilities—Background and issues for congress, RL33153. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153 (Accessed August 16, 2024).

Office of Naval Intelligence . (2017). Iranian naval forces: A tale of two navies. 14. Available at: https://www.oni.navy.mil/Portals/12/Intel%20agencies/iran/Iran%20022217SP.pdf (Accessed February 22, 2017).

Office of Naval Intelligence . (2024a). China coast Guard and government maritime forces recognition and identification guide. Available at: https://www.oni.navy.mil/Portals/12/Intel%20agencies/China_Media/2024_Recce_Poster_Coast_Guard_Govt__U__new.jpg?ver=K7SsX6_f50ohUsN4qZuQqg%3d%3d (Accessed April 29, 2024).

Office of Naval Intelligence . (2024b). China People’s liberation Army navy (PLAN) recognition and identification guide. Available at: https://www.oni.navy.mil/Portals/12/Intel%20agencies/China_Media/2024_Recce_Poster_PLAN_Navy__U__new.jpg?ver=iAEux6xjCb6wOKmIzTIiAw%3d%3d (Accessed April 29, 2024).

Office of the Secretary of Defense . (2023). Military and security Developments involving the People’s Republic of China 2023. Available at: https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF (Accessed October 19, 2023).

PRC State Council Information Office . (2015). China’s military strategy. Available at: https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2015/05/27/content_281475115610833.htm (Accessed May 27, 2015).

Rielage, D., and Strange, A. (2019). “Is the maritime militia prosecuting a people’s war at sea” in China’s maritime gray zone operations. eds. A. Erickson and R. Martinson (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press), 38–51.

Shi, C., and Chen, Y. (2018). On the Navy’s strategic positioning in the new era. National Defense 5, 34–36.

Soha.vn, (2015). Abandoned “historic” ship sunk by China. Available at: http://soha.vn/xa-hoi/bo-hoang-con-tau-lich-su-bi-trung-quoc-dam-chim-20151112141432744.htm (Accessed November 12, 2015).

Sohu.com . (2023). “The first coast Guard version of 054A is painted with the Hull number! Is the Total tonnage of China’s coast Guard higher than that of Western naval powers?” Available at: https://www.sohu.com/a/743753978_121452400 (Accessed December 13, 2023).

Thorne, D., and Spevack, B. (2019). Ships of state: Chinese civil-military fusion and the HYSY 981 standoff. Center for International Maritime Security. Available at: https://cimsec.org/ships-of-state-chinese-civil-military-fusion-and-the-hysy-981-standoff/ (Accessed January 23, 2019).

U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard . (2020). Advantage at sea: prevailing with integrated all-domain naval power. Available at: https://media.defense.gov/2020/Dec/17/2002553481/-1/-1/0/TRISERVICESTRATEGY.PDF/TRISERVICESTRATEGY.PDF (Accessed December 17, 2020).

Wang, A. (2024). Chinese coastguard set to get new ship modelled on advanced type 052D destroyer. South China morning post. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3274494/chinese-coastguard-set-get-new-ship-modelled-advanced-type-052d-destroyer (Accessed August 14, 2024).

Wang, W., and Yang, Z. (2009). New progress in the study of people’s war ideology under informatized conditions. J. Xian Polit. Institute 22, 94–97.

Wu, S. (2014). Learn profound historical lessons from the Sino-Japanese war of 1894–1895 and unswervingly take the path of planning and managing maritime affairs, safeguarding maritime rights and interests, and building a powerful Navy. China Milit. Sci. 4, 1–4.

Wu, Z. (2019). Towards naval normalcy: “open seas protection” and Sino-U.S. maritime relations. Pac. Rev. 32, 666–693.

Wu, J., Huang, C., and Liu, C. (2015). Thoughts on advancing ocean defense construction work in the new situation. National Defense 12, 70–73.

Xi, J. (2017). “Secure a decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous Society in all Respects and Strive for the great success of socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era.” Delivered at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. Available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/download/Xi_Jinping’s_report_at_19th_CPC_National_Congress.pdf (Accessed October 18, 2017).

Xinhua . (2013). Xi advocates efforts to boost maritime power. Available at: http://www.china.org.cn/china/2013-07/31/content_29589836.htm (Accessed July 31, 2013).

Xinhua . (2019). Yin Zhongqing: development of the marine economy currently faces four major problems. Available at: www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2019lh/2019-03/10/c_137883595.htm (Accessed March 10, 2019).

Yamaguchi, S. (2016). Strategies of China’s maritime actors in the South China Sea: a coordinated plan under the leadership of Xi Jinping? China Perspect. 3, 23–31. doi: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.7022

Yang, X., and Yang, Z. (2019). On the historical position and strategic requirements of the People’s navy. J. Nav. Univ. Eng. 16, 47–50.

Yoshihara, T. (2016). The 1974 Paracels Sea Battle: a campaign appraisal. Naval War College Rev. 69.2, 41–65.

Yoshihara, T. (2023). Mao’s Army Goes to sea: The island campaigns and the founding of China’s navy. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

You, G., and Chen, L. (2010). Application of Mao Zedong’s people’s war thought under information technology. Theoretic Observ. 61, 38–39.

Yu, W. (2018). Take advantage of the situation to build a world-class military command college. People’s Navy 13:3.

Yuan, X. (2002). Prepare fully for maritime militia warfare—deputy to the National People’s congress, commander of Zhejiang military region. Natl. Defense 3, 23–24.

Zhan, L. (2009). Contemporary lessons from Mao Zedong’s thought on building the People’s navy. Mil. Hist. 3:20.

Keywords: China, naval, navy, maritime, military, defense, strategy, coast guard

Citation: Erickson AS (2024) Essence of distinction: the ends, ways, and means of China’s military maritime quest. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1448241. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1448241

Received: 13 June 2024; Accepted: 14 August 2024;

Published: 11 September 2024.

Edited by:

Sharyl Cross, St. Edward’s University, United StatesReviewed by:

Rodger Baker, Stratfor Center for Applied Geopolitics at RANE, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Erickson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrew S. Erickson, YW5kcmV3LmVyaWNrc29uQHVzbndjLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.