- 1Corvinus University of Budapest, Budapest, Hungary

- 2Future Potentials Observatory, Budapest, Hungary

- 3University of Defense, Brno, Czechia

To characterize the bilateral partnership, this paper applies the neoclassical geopolitics approach. We first measure China’s potential, and the perception of Chinese geopolitical agents, and placed within the international distribution of capabilities. This is followed by our analytical results on Sino-Russian relations in the spheres of potential, strategic culture, and geopolitical design. The paper concludes that while there is a strategic necessity for China to strengthen the partnership, the Sino-Russian relations are unlikely transforming into a traditional military alliance, due to Beijing’s self-interest to maintain trade relations with Western countries, to avoid being tainted by Russia’s deteriorating reputation, to grasp its goal of multipolar world order, and to spread positive narratives of China as a new global leader. The Sino-Russo relations has been shifting its nature from “marriage of convenience” to “marriage who pretend to be a good couple.”

1 Introduction

This paper addresses the topic of the steadfast and broad deepening of Sino-Russian cooperation. How has this cooperation evolved, and what are its drivers on the Chinese side? The paper’s objective is to describe and explain the causes of China’s relations with Russia in line with the milieu of the international distribution of capabilities. We claim that the Sino-Russian relations will tend to strengthen.

Accordingly, in Section 1 we assess China’s relative potential by examining the country’s geographical location, economic strength, military capabilities, and population. In Section 2, we appraise systemic stimuli and China’s status by addressing the significant treaties and agreements China has signed with Russia, analyzing the permissiveness and clarity of the international system, and determining the opportunities and threats associated with Sino-Russian relations. In Section 3, we characterize the Chinese geopolitical agent, analyzing its perception of geographical space, exploring Chinese strategic culture, and assessing the personal pro-Russia stance of the Chinese geopolitical agent. In Section 4, we present our results about China’s responses to systemic stimuli and its relative material potential, the Chinese geopolitical agent’s strategic culture, perception of space, and geopolitical design, and also China’s geopolitical continuities.

We cover roughly the period from 2000 to May 2023, having examined political speeches (Taliaferro, 2006), texts of treaties between the two states, academic literature, and economic, military, and population statistical data.

Previous literature has also addressed many empirical elements covered in this paper. For example, literature has asserted that Russia and China, among other rising powers, are dissatisfied with the current balance of power and not only wish to change it, but have already begun to form a bloc to counter it (Hart and Jones, 2010; Binder and Lockwood Payton, 2022). Other pieces of literature claim that China and Russia share similar worldviews (shared norms, political identity, geopolitical culture, and styles of negotiation; Ambrosio et al., 2020; Bossuyt and Kaczmarski, 2021; Malik, 2021; Paikin, 2021; Petersson, 2021). Others have confirmed that China and Russia are the frontrunners in the international struggle against the United States (Bossuyt and Kaczmarski, 2021; Sutter, 2021; Vinogradov, 2021; Sempa, 2022). The relation between the two countries has been covered too, from the perspectives of an “axis of convenience” (Paolo and Carteny, 2022), a “quasi-alliance, or entente” (Lukin, 2021) to a “Sino-Russian alliance” (Sempa, 2022), which contradicts the alternative hypothesis that Sino-Russian relations are very fragile—such as Xin claims (Xin, 2021, 95).

We have identified a gap in the literature in relation to the dearth of studies that go beyond the classical realist conceptual framework, as Bossuyt and Kaczmarski (2021), among others, call for. We therefore apply the neoclassical geopolitics approach—a two-level approach that combines an examination of the international system with domestic-level variables.

2 Theoretical background

We follow and apply the theoretical-methodological framework of neoclassical geopolitics developed by one of the authors (Morgado, 2020, 2023).

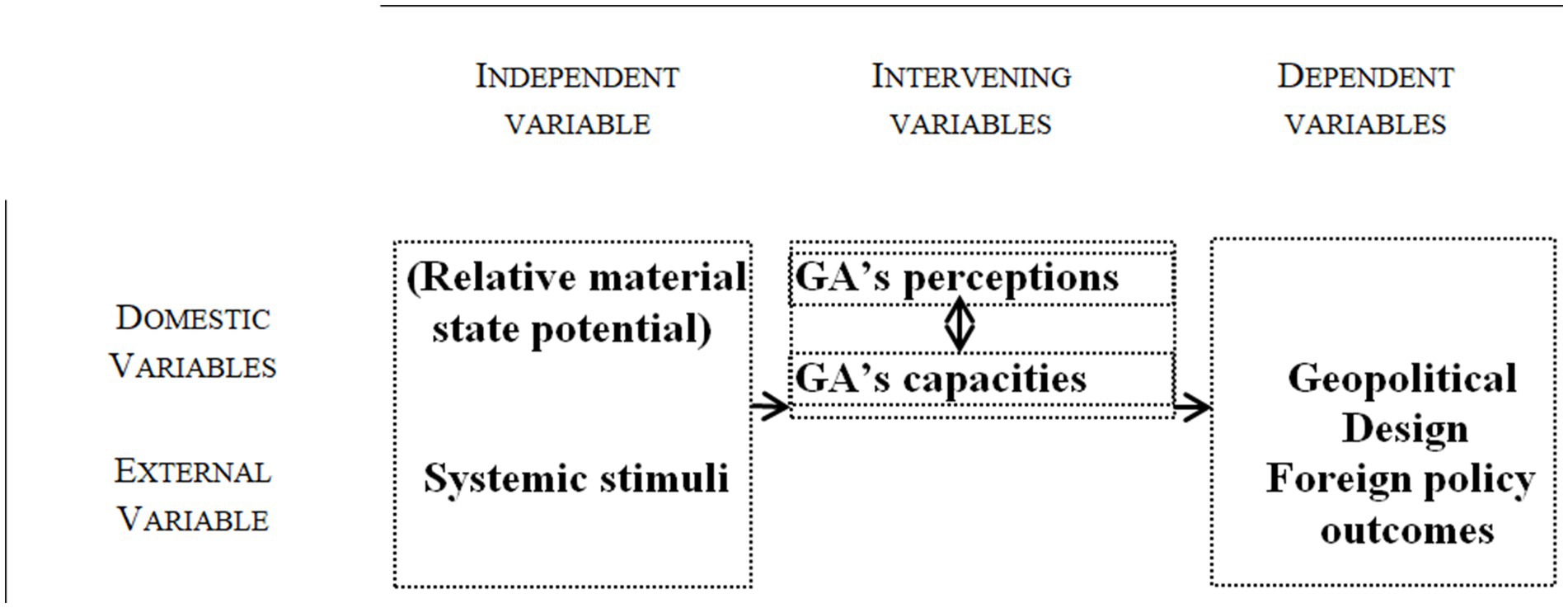

The international system is the independent variable for neoclassical geopolitics, as it is for neoclassical realism (Ripsman et al., 2016). Therefore, the paper starts with assessing China’s relative potential by examining China’s geographical location, economic strength, military capabilities, and population. This step contributes to the following one: an appraisal of systemic stimuli and China’s status that addresses the significant treaties China has signed with Russia, analyzes the permissiveness and clarity of the international system, and determines the opportunities and threats in Sino-Russian relations. Regarding the intervening variables, the paper revisits and develops the research agenda of one of the current authors (Morgado, 2023)—namely, identifying and characterizing the geopolitical agent. Identifying geopolitical agents involves pointing out who the crucial individual(s) are that constitute the foreign policy cabinet.1 As China is an autocracy, the research will focus on the formal agents of political power and leave aside the study of the clusters of foreign affairs-, defense-, and intelligence experts.2 After identification follows the characterization of the geopolitical agents. For the purposes of this paper, the characterization of the geopolitical agent includes an analysis of perceptions of geographical space, brief considerations of China’s strategic culture, an exploration of the personal pro-Russian stance of the Chinese geopolitical agent, and a general estimation of the geopolitical agent’s resource extraction capabilities. We provide details about these methodological tasks in the respective sections of the paper (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model of neoclassical geopolitics. Source: Morgado, 2023, 14.

The (1) assessment of China’s relative potential (by examining China’s geographical location, economic strength, military capabilities, and population) allows an initial understanding of the ‘raw’ capabilities that China has at its disposal.

The (2) measurement of systemic stimuli and China’s status (by considering the significant treaties China has signed with Russia, analyzing the permissiveness and clarity of the international system, and determining the opportunities and threats in Sino-Russian relations) helps refine the nature of the distribution of power at the regional and world level, allowing a better systematization of the threats and opportunities perceived by China.

The (3) analysis of China’s geopolitical agent (through perceptions of space, strategic culture, and personal positions) involves scrutinizing what kind of perceptions the geopolitical agents have about the implications of the incentives associated with the geographical setting in geostrategic formulation and foreign policy conduct. The hypothetical causal link is that if the geopolitical agents are not clearly aware of the sum of the findings of geopolitical studies,3 and if they consequently accumulate observable failures in foreign policy, then the latter can be considered misguided in terms of their sense of space (geomisguided). Strategic culture and personal positions are also crucial for explaining the intentions of the geopolitical agents (Chauprade and Thual, 1998, 496). The paper also addresses the geopolitical agent’s capacities within the domestic power structure. In other words, it acknowledges not only that geopolitical agents’ capacities are constrained by their perceptions (i.e., one cannot act accurately when one cannot perceive accurately) but also by the domestic power structure (i.e., one may well perceive and may be capable of acting well per se,yet may not have the necessary freedom from the domestic power structure to act). In these terms, the inquiry into the domestic power structure involves observing the convergence or divergence between the preferences of the geopolitical agents and those of the nation. The greatness of relative material state potential is ultimately connected to the variable ‘geopolitical agent’s capacities’ (i.e., a state cannot act beyond its capabilities).

The theoretical framework is concluded with a definition of the key concepts employed in the paper. Accordingly: (a) “the international system” refers to the interstate political system characterized by an anarchic ordering principle (Ripsman et al., 2016, 43); (b) “relative material state potential” designates “the capabilities or resources… with which states can influence each other” (Wohlforth, 1993, 4),4 meaning both material and non-material resources; (c) “strategic culture” corresponds to “…a set of inter-related beliefs, norms, and assumptions…” that establish “…what are acceptable and unacceptable strategic choices…” (Ripsman et al., 2016, 67); (d) “perception of space” signifies what meaning the geographical setting’s incentives have for the geopolitical agents (assuming that the geopolitical agents are aware of these incentives); (e) “geopolitical design” indicates both a list of state objectives (national objectives) and their hierarchy (Chauprade and Thual, 1998, 486–487). Finally, (f) a “geopolitical continuity” occurs as a “dynamic of continuity” that can be deduced from the durability of specific objectives—or, as Chauprade and Thual put it, “geopolitics considers the importance of the fact in relative terms, including that fact in durable dynamics” (Chauprade and Thual, 1998, 483).

3 China’s potential

To apply the model of neoclassical geopolitics, this section evaluates China’s geographical location, economic strength, military capabilities, and population as elements of its relative potential, i.e., mobilizable assets for achieving its strategy.

3.1 Geographical location

Located in the east of Eurasia, China has 14 land-based neighbors with different historical origins, political systems, levels of economic development, and socio-cultural conditions. It creates a complex diplomatic and security environment around China. In addition, China is separated by a sea from major maritime nations such as Japan, the United States, and Australia on the other. As a result, a V-shaped geopolitical ‘hotspot line’ around China traverses five regions (North Asia, Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Central Asia), having a significant impact on China’s geopolitical perceptions (Sun et al., 2016). China’s core interest in the complex geopolitical setting prevents its powerful neighbors on land and sea from cooperating to pinch China from behind or both sides (Wan and Wang, 2009) and a “Uniting with the North, advancing to the West, cooperating with the South, and exploring the East” approach is promoted (Mao, 2014).

Russia in particular, a major power adjacent to China, has had a profound influence on Chinese foreign policy, defense strategy, economy, and society since the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and even after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the two nuclear and conventional powers5 continue to share a 4,179 km long border that creates the geopolitical setting of adjacency. Hence, crucial goal for Beijing is how to maintain stable relations with Russia.

3.2 Economic strength, military capabilities, and population

China’s increasing global influence can be seen not only in numerical indicators—its population of over 1.4 billion people, the world’s second-largest economy, the world’s second-largest military expenditure, the world’s highest number of rocket launches (People’s Daily, Jan 21, 2022)—but also in its increasing scientific achievements, such as space exploration and the rise in the number of citations of papers written by Chinese scholars in scientific journals with international reach (China Daily, 2023). Beijing is also increasing its international influence thought promoting China’s positive narratives, and financing & sending staff to international organizations.

3.2.1 Economic strength

Although the Chinese economy is growing steadily and has potential, it is undeniable that the real economy is facing a variety of structural problems and challenges. Beijing expects some of the problems can be ameliored by strengthening economic ties with Russia.

Since 1978, China has developed its export-oriented socialist-market economy, and China’s nominal GDP in 2010 reached $5.878 trillion, $404.4 billion more than Japan’s. Since then, China has had the second-largest economy in the world. China’s nominal GDP for 2022 was RMB121.020 trillion (US$17.7 trillion), RMB13 trillion more than the previous year, and catching up with the United States (US$20.9 trillion). According to Lin Yifu, a former World Bank vice president and adviser to Chinese Communist Party (CCP, officially CPC), the Chinese economy has strong untapped potential, even though the war with Ukraine is impacting the country, and it is expected to overtake the United States as the world’s largest economy in terms of total GDP around 2030 if Beijing maintains annual growth of 5% (South China Morning Post, 2022). According to statistics released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China in February 2022, China’s GDP per capita (nominal) in 2022 was 85,698 yuan (US$12,300), an increase of 3.0% year-on-year (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2023).6 As a result, the country is expected to become a “high-income country” (as defined by the World Bank at $12,695 GDP per capita or more) by 2025 at the latest. However, 2022 GDP growth reached only 3.0%, far below the official target, although the IMF estimates 5.2% GDP growth in 2023 (IMF, 2023).

One of structural economic challenges of PRC is strong dependence on public investment. It is associated with local government insolvency, and defined by its low level of economic efficiency and weak innovation capacity of state-owned enterprises, which often rely on advanced technology from the West including semiconductors. China has an export-led growth model that depends on Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC), especially the Strait of Malacca, although Beijing attempts to adopt so called “dual circulation” strategy with promotion of both export and domestic economy.

3.2.2 Military capabilities

Since July 2013, when Xi Jinping (then General Secretary of the Party) emphasized the steady promotion of the construction of a “strong maritime nation” (following the policy defined by Hu Jintao), preparations for establishing maritime supremacy have been underway. This approach including the strengthening capability of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) under the command of the People’s Armed Police, Maritime Militias (MM), and the preparation of maritime-related rules and practical guidelines.

In November 2015, Xi Jinping announced military reforms, which included reducing 300,000 active-duty personnel to 2,185,000 with 1,170,000 reserves and establishing a “Strategic Support Force (dismantled by April 2024)” tasked with collecting and applying information from cyber-information warfare and space platforms as an independent military branch. In addition, the decision of the 19th Central Committee was to explore “Multidomain Intelligentized warfare,” which pursues integrated operations among branches of the military. China is also pursuing “military-civilian fusion (MCF),” a synergistic combination of civilian and dual-use technologies in a wide variety of fields, including drones, AI, and disruptive technologies, to achieve technological breakthroughs for “the great rejuvenation of China.”

China’s official military budget—the definition of ‘military budget’ is not the same as used by Western countries, being less inclusive (Funaiole and Hart, 2021)—increased by 7.2% to 1.5537 trillion yuan (US$224.8 billion) in 2023. According SIPRI database, Beijing exceeded Russia’s military spending in 1995 (PRC: US$27.9 billion, Russia: US$24.8 billion) and attempts to catch up with the United States (US$842 billion as FY 2024 DoD request). It may be noted here that while the United States has maintained a global forward deployment strategy, China concentrates less land forces in the Eurasia except Kashmir, and the more of its military assets have been deployed in the Western Pacific.

3.3 Population

In terms of population, which is an important factor in determining the relative potential of a state (Bezverbny, 2015; Eberstadt, 2016), China has a large population of 1.455 billion as of May 2023, and it indicates a high potential. However, the number of births has been declining since 2017, and the natural rate of increase (number of births minus number of deaths) was minus 1.2% in 2022 for the first time (Global Times, 2023). This indicates that the population has already peaked, and it is surpassed by India at the end of April 2023.

Furthermore, a trend to decline total fertility rate: TFR (fell from 1.15 in 2021 to 1.09 in 2022) leads to a decrease in the working-population, the country faces the problem of an aging population that will increase in size before society becomes affluent, forcing the government to enhance public pensions and social security. The population of elderly Chinese persons (aged 65 and above) reached 209.8 million in 2022, accounting for 14.85% of the total population (South China Morning Post, 2022). Japan’s experience shows how a decline in the working-population leads to a downward trend in consumption, leading to economic stagnation, and decline in tax revenues (Fukuchi, 2023). Cai and Wang point out “demographic dividend (working-population surplus)” has fueled economic growth in PRC, but its effects are diminishing, and this will be a headwind for Chinese economy going forward (Cai and Wang, 2014).

4 Systemic stimuli and China’s status

This section characterizes the Sino-Russian bilateral relationship through an evaluation of the treaties and agreements that govern the bilateral relationship and examines the Chinese leadership’s perception of the relationship to date, as well as the permissiveness and clarity of the international system, and the Sino-Russian relations in the Cold War to deduce opportunities and threats for China.

4.1 Significant international treaties with Russia

In recent years, Russia has been positioned as the most important “strategic partner” in the field of diplomacy, economy, and security for Beijing because the Chinese politburo perceives danger in US global hegemony and its promotion of democracy, which threatens Chinese security interests in Asia (Chase et al., 2017). Russia was initially not enthusiastic about deepening this bilateral partnership; however, after the United States imposed sanctions on Russia due to the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Moscow was forced to consider developing its partnership with Beijing more seriously (Zhao, 2023).

The first step in improving bilateral relations was solving the border issues between the two countries. China and Russia signed an agreement on the demarcation of the eastern part of their shared border in 1991, followed by a complementary agreement on the Eastern Section of the China-Russia Boundary in October 2004. A pact about the Western section of the boundary was signed in September 1994. Finally, an additional protocol on the eastern part of the border was signed in July 2008, thereby settling the issue of the identification of the over 4,179 km-long China-Russia borders.

The term “constructive partnership” was first used in Sino-Russian relations in the 1994 Joint Declaration, and the term “strategic partnership” in the 1996 Joint Declaration, both are initiated by Russian side (Ishii, 2016). Both countries explain that the “partnership” is not a “Cold-War-minded alliance” that is generally designed to oppose a specific country, and that it has no military goals that involve opposing third countries. On July 16, 2001, the two countries signed the China-Russia Good Neighborhood Friendship and Cooperation Treaty based on intergenerational friendship relations supported by the principles of sovereignty protection, territorial integrity, respecting the core interests of both participants, and noninterference in internal affairs. This treaty is a basis for bilateral relations, and it was extended for 20 years in July 2021.

In June 2011, the two countries established a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination to strengthen measures associated with local currency settlements, financial cooperation, mutual investment for promoting economic ties and cooperating in space development, the development of nuclear energy, GPS, and BRICS cooperation. Beijing and Moscow upgraded this to the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination for a New Era in June 2019, aimed at strengthening strategic coordination in the UN. On top of this, the Joint Statement on International Relations for a New Era was released on February 4, 2022, during the Beijing Olympics. The statement, which is said to have strongly reflected intentions of Le Yucheng, then first vice minister of foreign affairs, called for “no-limits” bilateral cooperation. However, this attracted criticism from and controversy in the ‘diplomatic moderates’ group in China, who value balance between the United States and Russia and have some influence in China’s diplomatic sphere; for example, the Chinese ambassador to the United States Qin said that “China-Russia cooperation has no-limits, but it does have a bottom line with purposes and principles of the U.N. Charter” (Qin, 2022). Xi and Putin declared the further deepening of the partnership and expressed their critical stance about the West, which continues to provide Ukraine with arms, funds, intelligence, and impose economic sanctions on Russia, in the latest bilateral joint declaration in March 2023.

4.2 Permissiveness and clarity in the international system

The Chinese leadership recognizes that “the world is undergoing profound changes unseen in a century” (MOFA of PRC, 2019) and believes in the fall of the “West” and the rise of the “East,” especially given the attention being paid to such changes, Beijing recognizes this as an opportunity (Chen, 2022). Xi administration recognizes that the process of China’s rise will inevitably expand its sphere of influence and radius of interests, and induce corresponding geopolitical pressures. The more China moves closer to the center of the global stage, the more the risks and challenges to China, such as pressure from the United States, leading to significant struggles (Wang, 2021). Beijing is praising itself for playing a leading role in spreading “diversity” and “multilateralism” around the world, while the United States dominates using zero-sum game-like Cold War-type thinking and insists on forming “small circles” to attempt for dividing the world (MOFA of PRC, 2021; MOFA of PRC, 2022).

However, objective observation and analysis of China’s actions in the South China Sea, the East China Sea, and around Taiwan highlight China’s duplicity in attempting to ‘change the status quo by force’ backed by its own outstanding power rather than through respect for the claims and rights of neighboring countries that are inferior in power (Reuters, 2022). In addition, despite having gained maximum benefits from the postwar international order and the free trade regime, China is increasingly challenging the postwar international order, interpreting international laws and regulations in a way that suits itself, and criticizing international rules that are unfavorable to China. In April 2023, China, with other BRICS members, proposed non-western multilateralism and challenges the World Bank, SWIFT system with US dollar, and G7 model, although the perceived difficulties of coordinating national interests among the BRICS countries are visible (Trinkunas, 2020).

4.3 Sino-Russian relations in the cold war and after

As Deng Xiaoping mentioned, “a root of problem in Sino-Soviet relations is inequality and China felt humiliated,” Sino-Soviet relations have historically been unequal (Le, 2019). Therefore, the key to improve the bilateral relations was how to resolve military inequality for Beijing. In this context, border stability within Eurasia is the fundamental strategic condition on which China can concentrate its national power in the maritime domain.

After the founding of PRC in October 1949 and the signing of the Sino-Soviet Friendship and Alliance Mutual Assistance Treaty in February 1950, China and the Soviet Union were socialist countries with a degree of monolithic unity. However, from the second half of the 1950s onwards, fundamental differences emerged between China and USSR concerning the policies of socialist revolution, socialist construction, and foreign policy. Conflict between the two countries was reflected in territorial disputes as well. In January 1968, Soviet troops ran over and killed a Chinese fisherman on Qiliqin Island in the Ussuri River in the eastern Sino-Soviet border, causing tensions to flare. On March 2 and 15, 1969, military clashes between Chinese and Soviet border guards occurred on Zhenbao Island (Damansky Island), south of Qiliqin Island (Ishii, 1997). The fighting was a warning by the Chinese side (Ishii, 1998; Yang, 2000; Goldstein, 2001) in preparation for a potential Soviet military invasion of China in support of the Brezhnev Doctrine, which justified the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact military intervention in Czechoslovakia in August 1968 and stated that “the sovereignty of individual states should be limited in the interest of socialism as a whole.”

In response to rising Sino-Russian tensions, Moscow significantly strengthened its Far Eastern Military District from the late 1960s onwards, increasing the number of divisions from 17 in 1965 to 28 in 1969 (including two on Mongolian territory following January 1966), while the Chinese military also deployed 32 divisions in the Beijing Military District and four in the Shenyang Military District. In addition, the Soviet Union deployed R-12 MRBM and R-14 IRBMs equipped with nuclear warheads in the Far East. While the deployment of Russian forces in the vicinity of the Chinese border has been significantly reduced since the end of the Cold War, decline of Russia’s military power, especially its land forces, due to heavy loss in Ukraine has reduced military pressure on China.

5 China’s geopolitical agent

In this section, we identify Xi Jinping and the Chinese Central Politburo as China’s geopolitical agents and examine their perceptions of space and geopolitical conditions, as well as strategic culture and resource-extractive capacities.

5.1 Identification of China’s geopolitical agent

Since Xi Jinping was elected president in 2013, he has eliminated his rivals and political opponents and strengthened the domestic ruling system through an anti-corruption campaign (The Guardian, 2013). The Politburo under Xi Jinping’s regime is a top decision-making body in CCP increasingly dominated by Xi’s personal influence (Li, 2016), consisting of 25 members. It plays a critical role to formulate policies, guide the party’s overall direction, centralize authority, reduce factionalism, and enforce party discipline. As a result, the “inner-party democracy” (collective leadership system that emphasizes decision-making based on rules and norms) of Deng Xiaoping has been transformed into Xi Jinping’s personalistic system of rules (Li, 2016; Shirk, 2018). Since Xi Jinping was re-elected as CCP general secretary, and members of the politburo were elected in October 2022, the Xi regime, which consolidates the periphery using its own yes men, has taken the lead based on a preponderance of numbers, reflecting Xi Jinping’s ideas in its policies.

At the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, “Socialist Ideology with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era by Xi Jinping” (Xi Jinping Thought) was included in the Constitution of CCP, alongside Mao Zedong Thought and Deng Xiaoping Theory. In addition, constitutional amendment in March 2018 eliminated the provision (Article 79, Paragraphs 2 and 3) limiting the term of office of the President to “two terms of 10 years.” Furthermore, from September 2021 onwards, classes on Xi Jinping’s philosophy were made compulsory in school education, reinforcing the personal worship of Xi Jinping as the core element of CCP.

5.2 The geopolitical agent’s perceptions of geographical space

At a ceremony marking the 70th anniversary of the establishment of Sino-Russian relations on June 5, 2019, Xi described Russia as “a good neighbor that cannot be moved and a true partner that cannot be dismantled, whether in the past, present, or future (Government of PRC, June 6, 2019).” It suggests his perception of the potential and limits of the space between China and Russia. He also admired construction of a new type of great power relationship based on equality and mutual respect that involves “non-alignment, non-confrontation, and [which] does not target third countries,” as advocated since the 1994 Joint Declaration (Xi, 2019).

It is an example of arrogant space consciousness of Chinese geopolitical agent that Xi mentioned “the vast Pacific Ocean is large enough to accommodate the two superpowers of China and America,” when Secretary of State Kerry visited China in April 2013. This fundamental way of “G-2 (Group of Two)” concept is nothing new. During official visit by Admiral Timothy J. Keating, then commander of US Pacific Command, to China in May 2007, a Chinese naval official suggested dividing up the Pacific Ocean that the United States takes care the area east of Hawaii (Eastern Pacific) and that China does the area west of Hawaii (Western Pacific), and both will just communicate with each other. In China, the geopolitics tends to be understood as traditional grand strategy to focus on central role of state in geographic space (Fang, 2023).

5.3 Characteristics of China’s strategic culture

Based on Marxism, Xi Jinping established socialism with Chinese characteristics (Xi Jinping Thought) at the 19th Party Congress. In other words, in Xi’s Marxist understanding, the substructure (economy), which suggests actual development in the rise of the Chinese economy on a global scale, should be reflected in the superstructure (global politics). It is important to note that the shift of power from the West (United States and Europe) to the East (China) is understood as dialectically natural in Chinese politburo. Furthermore, Xi Jinping’s high regard for Mao Zedong’s ideology, which emphasizes the importance of “independence and self-reliance” and “self-rehabilitation,” has led him to emphasize Chinese self-respect and confidence without imitating foreign models, and the need to achieve the status of a military and maritime superpower through Han-Chinese-centric discourse about the “Great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

5.4 Pro-Russian stance of the Chinese geopolitical agent

Crucially, it is not only the perceived strategic necessity of countering the increase in pressure from the United States but also Xi Jinping’s personal admiration of Russia and Putin, which has been shaped by the social atmosphere in China, that deepen the Sino-Russian strategic partnership (Yun, 2022). Indeed, in a television interview aired in February 2014, Xi Jinping expressed his admiration of “strong” Russia and trust in Putin. Xi Jinping celebrated Putin’s birthday with him in Bali, Indonesia, on October 7, 2013, and in Dushanbe on June 15, 2019. Thus, Xi Jinping’s pro-Russian discourse of trust and closeness to Putin is highlighted as a significant factor in deepening the China-Russia comprehensive strategic partnership. However, it may be noted that Putin emphasizes strategic importance rather than trust (Yan, 2013), and differences of perceptions between Xi Jinping and Putin exist.

6 Analytical results

A comprehensive two-level analysis of domestic factors and the international system indicates that by devising a form of Sino-Russian relations that does not take the form of an ‘alliance’ in which a real hierarchy of power is formed but the shape of a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination’ that avoids hierarchization and emphasizes equal positions allows both countries to enjoy diversified and multi-layered relations that generate geopolitical, political, and economic benefits. The advantages of this ingenuity should not be underestimated.

6.1 Responses to systemic stimuli

It is undeniable that for Beijing, handling the increasingly tense China-US persistent great power competition, promoting economic growth, and resolving the Taiwan issue are important strategic goals. In response to the power competition, China has had strategic reasons to avoid not only being isolated by the US but also to avoid improvement of US-Russia relations in the context of the US-Russia-China triangle, whose sides are not equal (Rogov, 2022). In this regard, strategic cooperation between China and Russia is not the result of a voluntary choice by the two countries but rather a choice made under strategic pressure from the United States (Zhang, 2022). The cooperation includes strategic coordination at the UN Security Council and dealing with various regional issues as well. The Sino-Russian partnership also seeks to leverage the position of France, which is critical of some US policies, to create a neutral position in situations of an equal split (PRC and Russia vs. US and United Kingdom) among the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, as well as avoiding the one-to-four isolation of China (Yan, 2013). Beyond the US-China competition, Beijing’s efforts to strengthen the Sino-Russian partnership are also driven by Xi Jinping’s personal belief about “the fall of the West” already mentioned, which is the foundation of the long-term perception of the international power cycle trend according to the Chinese geopolitical agent.

6.2 Relative material state potential

It is valuable for China and Russia to keep and promote bilateral military cooperation, which is explained as “non-aligned, non-confrontational, and not targeted at third countries.” The latest Military Cooperation Roadmap for 2021–2025 calls for enhanced military cooperation in three main areas: joint military exercises, joint strategic patrols, and strategic coordination. Under the plan, China and Russia conduct joint maritime military exercises, joint strategic patrols by strategic bombers, and strategically coordinate joint action at the UN Security Council. These joint exercises and patrols should be recognized not only as politically symbolic activity that showcases the countries’ “unity,” but also as practical information-gathering purpose aimed at exploring Japan’s radar blind-spots. The partnership is for bilateral confidence building, promoting anti-Western narratives, and sharing military technologies rather than collective defense.

From economic and resources aspects, China has been a net importer of oil since 1993 due to declining domestic oil production and growing domestic demand. China imports oil from the Middle East and African countries via SLOC,7 and its strong dependence on SLOC for trade and resource imports seems to be its Achilles’ heel. Securing alternative land transportation routes through BRI and constructing nuclear power plants in China with Russian support are vital to strengthen resilience for Beijing. PRC increased imports of crude oil from the Middle East (from Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UAE, and Oman) through the Strait of Malacca, although China imports 86.24 million tons of Russian crude oil in 2022, up 8.2% from 79.64 million tons in 2021 (Tass, 2023) and Russia became China’s biggest crude oil supplier (Reuters, 2023) thanks to the low price of Russian oil. In addition to crude oil, China signed a contract to increase its natural gas imports from Russia before Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. After Russia’s invasion began, natural gas imports from Russia also increased. The two leaders discussed the 2,600 km long Power-of-Siberia 2 pipeline project during the Sino-Russian summit in March and October 2023, designed to deliver an annual 50 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian gas from the Yamal peninsula to China via Mongolia and at least 98 billion bcm by 2030, although the details of the pipeline still need to be resolved (Reuters, 2023). Interestingly, domestic demand for crude oil and natural gas in China might reduce due to the construction of nuclear power plants, shale gas development in China, and the promotion of “becoming an electric car superpower” policy.

As Xi Jinping praised “two-way trade between China and Russia has grown by 116% over the last 10 years (MOFA of PRC, 2023)” at Xi-Putin Moscow summit in March 2023, bilateral trade reached $88.2 billion in 2012 and $190.3B in 2022 (China Daily, 2023). However, trade relations with ASEAN (US$975.3 billion), European Union (US$847.3 billion), and the United States (US$759.4 billion) in 2022 (General Administration of Customs of China) are more important for Beijing to ensure domestic economic growth.

In addition, many of essential materials and components for manufacturing industries needed by China’s manufacturing industry are imported from American, European, or Japanese companies, and cannot be obtained from Russian ones. Even China, which tries to reduce its dependence on Europe, the United States, and Japan by promoting indigenous semiconductor production, depends on imports of many materials, components, and manufacturing equipment.

6.3 Strategic culture

Since its founding in 1949, PRC has not experienced any military victories over other countries (although it controls over Tibet and some islands). At the beginning of PRCs’ history, it did not have enough economic strength to become a military power, even though People’s Liberation Army had a large number of soldiers for the human wave tactics, its military strength was limited for defensive posture. Instead, Beijing has prioritized economic development since the end of 1978 under Deng Xiaoping’s rule, and avoided the use or display of military power, and has promoted the building of international relations through diplomacy backed by economic influence. In recent years, however, with the increase of hard power thanks to economic development and military beefing up, there is a growing capability to proceed “changing the status quo by force” for its own strategic goals. The final solution to the Taiwan issue, in which Xi administration declares to employ all means including military to solve it, will require a concentration of forces in the Western Pacific region. Therefore, strategic cooperation with Russia to allow Beijing to concentrate to the Pacific is essential.

Furthermore, China is attempting to create a substantial buffer zone by penetrating its economic influence. Beijing is also growing more confident in its ability to exert influence over other countries by “holding hostage,” the expectation of future profits of other countries that want access to China’s domestic market. This expansion of influence through the economy includes penetration into Eurasian countries including Russia through BRI. It reflects Xi’s belief that the substructure (economy) should be reflected to the superstructure (politics).

6.4 Perception of space, geopolitical design, and geopolitical continuity

Based on historical lessons that involve a Sino-Soviet split, an experience of border clashes, and the current shift of power superiority except for with nuclear forces (Russia: 5,580 estimated warheads of 2024, PRC: 500, FAS 2023) from Russia to China, the Sino-Russian relationship need not be a hierarchical traditional alliance for Beijing, but the strategic partnership governed by the principle of equal, mutually respectful non-interference to achieve the “China dream.”

Defusing border tension and the reconciliation of historical confrontation with neighboring Russia are crucial for Beijing. Historically, Sino-Soviet relations were unequal, and the Sino-Soviet conflict over the past 20 years has caused immeasurable losses to both sides and lost valuable time for development (Le, 2019). To avoid repeating that mistake, he praised the establishment of a new type of great power relationship.

From the perspective of military strategy, deploying land and air forces along the border and mutually targeting nuclear weapons, as experienced during the Sino-Soviet tension in the 1960s, would be indeed a waste of resources. It would be more efficient for China and Russia to create an environment and structure for the countries operating back-to-back to concentrate their resources on their main strategic focus (Russia on the European front and China in the Western Pacific). Without a reliable backstop with Russia, China will not only lose focus, but it also faces the dilemma of being pinched from both sides from East and West (Yan, 2013).

7 Conclusion

The paper concludes that the China-Russia Strategic Partnership will continue to be used as an anti-Western platform; to secure resource access and trade; to concentrate China’s national power and potential in the Western Pacific; and to promote the “new type of international relationship” that is characterized as “non-aligned, non-confrontational, and does not target third countries” based on Xi Jinping Thought, results possible to achieve due to the sharp methodology of neoclassical geopolitics. The bilateral relation is likely to expand and deepen in terms of content in the future, primarily at the request of the Russian side due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has been affecting bilateral balance and growing Russia’s dependence on China. However, as long as the Chinese leadership recognizes the importance of maintaining stable and practical trade relations with Western countries and acts on its desire to show China as next global leader, China will be incentivized to prevent the partnership with Russia from transforming into a traditional military alliance. Therefore, the Sino-Russo partnership has been shifting its nature from “marriage of convenience” to “marriage who pretend to be a good couple.”

Author contributions

NM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study is an outcome of the Geopolitical Frontiers research project, Future Potentials Observatory, MOME Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The geopolitical agents or the “foreign policy executive” are “…the top officials and central institutions of government charged with external defense and the conduct of diplomacy” (Taliaferro, 2006, p. 470).

2. ^Ripsman et al. (2016, p.124) called them the FDIB—foreign, defense, intelligence bureaucracy.

3. ^These geopolitical studies’ findings come from dialectic inquiry and comparison between the geohistorical approach that examines former policies on one hand, and the study of geopolitical design, which reflects upon present policies and future scenarios on the other, using the method of controlled comparison to refine conclusions.

4. ^Wohlforth gave this definition of state power, but we consider it more appropriate for state potential.

5. ^Russia’s conventional ground forces have been degraded by some failures in Ukraine. It has become clear that serious problems exist with its tactics, force structure, inflexible command, and control systems, weapons systems, and logistics.

6. ^Statistical communique of PRC on 2022 national economic and social development, Feb. 28, 2023, http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202302/t20230227_1918979.html#:~:text=The%20per%20capita%20GDP%20in,percent%20over%20the%20previous%20 year.

7. ^PRC’s dependence on crude oil imports has dropped from 73.6% in 2020 to 72% in 2021 (State Council of PRC, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/202202/24/content_WS6216e221c6d09c94e48a569e.html, Feb 24. 2022). However, the dependence is expected to increase in 2023 (Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/china-set-record-crude-oil-imports-2023-analysts-2023-02-17/, Feb. 20, 2023).

References

Ambrosio, T., Schram, C., and Heopfner, P. (2020). The American securitization of China and Russia: U.S. geopolitical culture and declining Unipolarity. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 61, 162–194. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2019.1702566

Bezverbny, V. (2015). Geopolitics and population: how the demographic processes are shaping national power Institute of Social and Political Research, Russian Academy of Science. Available at: https://paa2015.populationassociation.org/papers/152660 (accessed on 8 February 2021).

Binder, M., and Lockwood Payton, A. (2022). With frenemies like these: rising power voting behavior in the UN general assembly. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 381–398. doi: 10.1017/S0007123420000538

Bossuyt, F., and Kaczmarski, M. (2021). Russia and China between cooperation and competition at the regional and global level. Introduction. Eurasian Geography Econ. 62, 539–556. doi: 10.1080/15387216.2021.2023363

Cai, L., and Wang, D. (2014). “Demographic transition: implications for growth” in The China boom and its discontents. eds. R. Garnaut and L. Song (Canberra: ANU Press), 34–52.

Chase, M., Medeiros, E. S., Stapleton Roy, J., Rumer, E. B., Sutter, R., and Weitz, R. (2017). Russia-China relations: Assessing common ground and strategic fault lines. Washington: The National Bureau of Asian Research, Available at: https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/SR66_Russia-ChinaRelations_July2017.pdf (accessed on June 15, 2023).

Chauprade, A., and Thual, F. (1998). Dictionaire de Géopolitique–États, Concepts, Auteurs. Paris: Ellipses.

Chen, Y. (2022). Strategic direction of Russia interpreted from its new National Security Strategy. Circulation 32, 46–64.

China Daily (2023). Vitalized partnership, march 30. Available at: http://epaper.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202303/30/WS6424e368a310777689887bef.html (accessed on 3 May 2023).

Eberstadt, N. (2016). Demography and human resources: unforgiving constraints for a Russia in decline. The Jamestown Foundation. Available at: https://jamestown.org/program/demography-human-resources-unforgiving-constraints-russia-decline/ (Accessed on 13 September 2016)

Fang, X. (2023) 政治’地理学诸概念辨析 [distinguishing and analyzing concepts in ‘political’ geography]. Chinese social sciences today. Available at: https://epaper.csstoday.net/epaper/read.do?m=i&iid=6475&eid=45809&sid=212011&idate=12_2023-01-10 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

FAS-Federation of American Scientists. (2023). 2022 status of world nuclear forces. Available at: https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20Biden%20administration,stockpile%20of%20approximately%203%2C70020warheads (accessed on 4 April 2023).

Fukuchi, A. (2023) Jinkou Doutai to Keizai Seichou [demographics and economic growth], Institute for International Monetary Affairs. Available at: https://www.iima.or.jp/docs/newsletter/2023/nl2023.03.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2023).

Funaiole, M.P., and Hart, B.. (2021) Understanding China’s 2021 Defense Budget. Critical Questions. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/understanding-chinas-2021-defense-budget (accessed on 5 May 2023).

Global Times. (2023) China-Russia bilateral trade surges 38.7 in first three months of 2023 to reach $53.85 billion: Customs data. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202304/1289071.shtml (accessed on 16 May 2023).

Goldstein, L. J. (2001). Return to Zhenbao Island: who started shooting and why it matters. China Q. 168, 985–997. doi: 10.1017/S0009443901000572

Hart, A. F., and Jones, B. D. (2010). How do rising powers rise? Survival: Global Politics Strategy 52, 63–88.

IMF. (2023). Opening remarks for the press briefing of the 2022 China article IV staff report. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/02/01/sp-china-aiv-press-briefing-opening-remarks (accessed on 15 May 2023).

Ishii, A. (1997). 中露・中ソ関係に見る領土紛争の事例研究 [a case study of territorial disputes in Sino-Russian and Sino-soviet relations]. JIIA. Available at: https://www2.jiia.or.jp/pdf/ryodo/h9_jisyukenkyuuhoukoku_ishii.pdf (accessed on October 10, 2022).

Ishii, A. (1998). “珍宝島事件-現地調査に基づく再考察- [the Damansky Island incident - a reconsideration based on field research]” in Historical counterpoints. eds. A. Yoshie, M. Yamauchi, and R. Kimura (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press), 121–135.

Ishii, A. (2016). 中ロ関係 —“同盟”の崩壊から新型国際関係モデルを求めて—[Sino-Russian relations-from the collapse of “alliances” to a new model of international relations]. Social Syst. Stud. 32:175. doi: 10.34382/00003959

Le, Y. (2019). 继往开来, 携手共创中俄关系新时代——写在中俄建交70周年之际 [building on the past, joining hands to create a new era of China-Russia relations --on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Russia]. Qstheory.Cn. Available at: http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2019-09/16/c_1124994803.htm (accessed on July 15, 2023).

Li, C. (2016). Chinese politics in the xi Jinping era: Reassessing collective leadership. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Lukin, A. (2021). The Russia–China entente and its future. Int. Politics 58, 363–380. doi: 10.1057/s41311-020-00251-7

Malik, T. H. (2021). Sino-Russian negotiation styles: a cross-cultural analysis of situated patterns. Asian J. Comparative Politics 6, 3–24. doi: 10.1177/2057891119887812

Mao, H. Y. (2014). 中国周边地缘政治与地缘经济格局和对策 [geopolitical and geoeconomic situation around the surrounding areas and China's strategies]. Prog. Geogr. 33, 289–302. doi: 10.11820/dlkxjz.2014.03.001

MOFA of PRC. (2014). Xi Jinping holds talks with President Vladimir Putin of Russia, stressing to expand and deepen practical cooperation, promoting China-Russia comprehensive strategic Partnership of Coordination to higher level. Available at: http://nz.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/ztbd/yxhfh/201405/t20140522_945372.htm (accessed on 10 May 2023).

MOFA of PRC. (2019). Wang Yi attends the formal meeting of the BRICS ministers of foreign affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC. Available at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/gjhdq_665435/2675_665437/2711_663426/2713_663430/201907/t20190730_513327.html (accessed on 5 March 2022).

MOFA of PRC. (2021) Speech by H.E. Xi Jinping president of the People's Republic of China at the conference marking the 50th anniversary of the restoration of the lawful seat of the People's Republic of China in the United Nations. Available at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202110/t20211025_9982254.html (accessed on 25 May 2023).

MOFA of PRC. (2022). Xi Jinping, BRICS Business Forum. Available at: http://brics2022.mfa.gov.cn/eng/tpxw/202206/t20220627_10710501.html (accessed on 18 April 2023).

MOFA of PRC. (2023). President xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin jointly meet the press. Available at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202303/t20230322_11046124.html (accessed on 18 May 2023).

Morgado, N. (2020). Neoclassical geopolitics: preliminary theoretical principles and methodological guidelines. International Problems 72, 129–157. doi: 10.2298/MEDJP2001129M

Morgado, N. (2023). Modelling Neoclassical Geopolitics: An Alternative Theoretical Tradition for Geopolitical Culture and Literacy. Eur. J. Geogr. 14, 13–21. doi: 10.48088/ejg.n.mor.14.4.013.021

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2023). National Economy Withstood Pressure and reached a new level in 2022, 17 January 17. Available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202301/t20230117_1892094.html (accessed on 17 June 2023).

Paikin, Z. (2021). Through thick and thin: Russia, China and the future of Eurasian international society. Int. Politics 58, 400–420. doi: 10.1057/s41311-020-00260-6

Paolo, P., and Carteny, A. (2022). The “new great game” in Central Asia: from a Sino-Russian Axis of convenience to Chinese primacy? Int. Spect. 57, 85–102.

Petersson, B. (2021) in Review of citizens and the state in authoritarian regimes: Comparing China and Russia. eds. K. J. Koesel, V. J. Bunce, and J. C. Weiss Eurasian Geography and Economics, Eurasian geography and economics, 64, 661–663.

Qin, G. (2022). Transcript of ambassador Qin Gang’s interview with ‘talk with world leaders’, embassy of PRC in the USA. Available at: http://us.china-embassy.gov.cn/eng/dshd/202203/t20220327_10656186.htm (accessed on 17 April 2023).

Reuters. (2022). China will never renounce right to use force over Taiwan, xi says. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/xi-china-will-never-renounce-right-use-force-over-taiwan-2022-10-16/ (accessed on 3 June 2023).

Reuters (2023). Explainer: Does China need more Russian gas via the power-of-Siberia 2 pipeline? Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/does-china-need-more-russian-gas-via-power-of-siberia-2-pipeline-2023-03-22/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

Ripsman, N. M., Taliaferro, J. W., and Lobell, S. E. (2016). Neoclassical realist theory of international politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rogov, S. M. (2022). An Inequilateral triangle: Russia−United States−China in a new geopolitical environment. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 92, 564–573.

Sempa, F. (2022). “The growing danger of the Sino-Russian Alliance”. The American Spectator. Available at: https://spectator.org/china-russia-diplomatic-revolution-of-2022/ (accessed on June 15, 2022).

Shirk, S. L. (2018). China in Xi’s “new era”: the return to Personalistic rule. J. Democr. 29, 22–36. doi: 10.1353/jod.2018.0022

South China Morning Post. (2022). Ukraine invasion won’t dent China’s push to surpass US, become top economy by 2030: Beijing adviser Justin Lin Yifu. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/article/3169687/ukraine-invasion-wont-dent-chinas-push-surpass-us-become-top (accessed on 19 June 2023).

Sun, F. H., Lu, D. D., and Dai, H. Z. (2016). 渤海海峡跨海通道建设 与中国的地缘政治战略 [the construction of trans-Bohai Strait passageway and its geopolitical strategies of China]. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 37, 1–10.

Sutter, R. (2021). Domestic drivers influencing Russia China alignment: implications for challenging the west. Asia Policy 16, 222–226. doi: 10.1353/asp.2021.0053

Taliaferro, J. W. (2006). State Building for Future Wars: Neoclassical Realism and the Resource-Extractive State. Secur. Stud. 15, 464–495.

Tass. (2023) China’s oil imports from Russia up 8.2% in 2022 to 86.24 mln tons – Customs. Available at: https://tass.com/economy/1564811 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

The Guardian. (2013). Xi Jinping vows to fight 'tigers' and 'flies' in anti-corruption drive. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jan/22/xi-jinping-tigers-flies-corruption (accessed on 5 May 2023).

Trinkunas, H. (2020). Testing the limits of China and Brazil’s partnership. Brookings Institution, Brookings Commentary, online publication. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/testing-the-limits-of-china-and-brazils-partnership/ (accessed on May 25, 2022).

United States Census Bureau. (2023). Trade in goods with China. Available at: https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html (accessed on May 13, 2023).

Vinogradov, A. (2021). China's project for greater Eurasia. Mezhdunarodnye Protsessy 19, 6–20. doi: 10.17994/IT.2021.19.2.65.2

Wan, N. Q., and Wang, Y. M. (2009). 中国陆海复合地缘环境的形成及其 战略选择 [the formation of China land-sea geoenvironment and her strategic choice]. J. Henan University: Natural Sci. 39, 377–381. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-4978.2009.04.012

Wang, Y. (2021). 深入学习贯彻习近平外交思想 奋进新时代中国外交壮阔征程 [in-depth study and implementation of xi Jinping's diplomatic thought to advance the magnificent journey of Chinese diplomacy in the new era,]” qstheory.Cn. Available at: http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2021-11/16/c_1128064546.htm (accessed on June 13, 2022).

Wohlforth, W. C. (1993). The elusive balance: Power and perceptions during the cold war. New York: Cornell University Press.

World Nuclear News (2023). China and Russia sign fast-neutron reactors cooperation agreement,” Available at: https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/China-and-Russia-to-cooperate-on-fast-neutron-reac (accessed on 5 May 2023).

Xi, J. (2019). 习近平在中俄建交70周年纪念大会上的讲话 [xi Jinping’s speech at the conference marking the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Russia]”. Available at: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-06/06/content_5397911.htm (accessed on 13 March 2023).

Xin, Z. (2021). Opportunities for further China-Russia rapprochement. Russia in Global Affairs 19, 94–100. doi: 10.31278/1810-6374-2021-19-3-94-100

Xinhua. (2021). Full text: Special address by Chinese president xi Jinping at the world economic forum virtual event of the Davos agenda. Available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-01/25/c_139696610.htm (accessed on 18 January 2023).

Yan, X. (2013). 中俄战略关系最具实质意义 [Sino-Russian strategic relationship has Most substantial meanings],” Carnegie endowment for international peace, online publication. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2013/03/26/zh-pub-51361 (accessed on June 28, 2022).

Yun, S. (2022). China’s strategic assessment of Russia: More complicated than you think. War on the rocks. Available at: https://warontherocks.com/2022/03/chinas-strategic-assessment-of-russia-more-complicated-than-you-think/ (accessed on May 25, 2022).

Zhang, J. (2022). 冷戦後30年は国際政治の「例外」か [is the post-cold war 30 years an “exception” in international politics?],” Japanese. China.Org.cn. Available at: http://japanese.china.org.cn/politics/txt/2022-04/18/content_78171378.htm. (accessed on May 15, 2022).

Keywords: Sino-Russian Axis, military cooperation, geopolitics, power, geography

Citation: Morgado N and Hosoda T (2024) A pact of iron? China’s deepening of the Sino-Russian partnership. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1446054. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1446054

Edited by:

Bhawna Pokharna, Government Meera Girls College Udaipur, IndiaReviewed by:

Syeda Naushin, University of Malaya, MalaysiaSeung-Youn Oh, Bryn Mawr College, United States

Copyright © 2024 Morgado and Hosoda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nuno Morgado, bnVuby5tb3JnYWRvQHVuaS1jb3J2aW51cy5odQ==

Nuno Morgado

Nuno Morgado Takashi Hosoda2,3

Takashi Hosoda2,3