Abstract

Introduction:

This article presents a model of political competition in which political parties, through clientelism strategies, vie for control of legislative seats. Parties exercise political violence to prevent potential rivals from gaining power and threatening their position within the hybrid political regime. The theory suggests that the degree of political violence exerted by parties in hybrid regimes will increase (decrease) as they concentrate more (less) power in the legislature.

Methods:

Using the methodology of analytical narratives, we examine the narrative on political violence in the Colombian political regime to identify key actors, strategies, information sets, and institutional changes. From these identified elements, we construct a theoretical model of political competition within the mathematical theory of games to explain the institutional changes highlighted in the narrative. Finally, we develop an econometric model to find statistical evidence supporting the predictions of the theoretical model derived from the narrative.

Results:

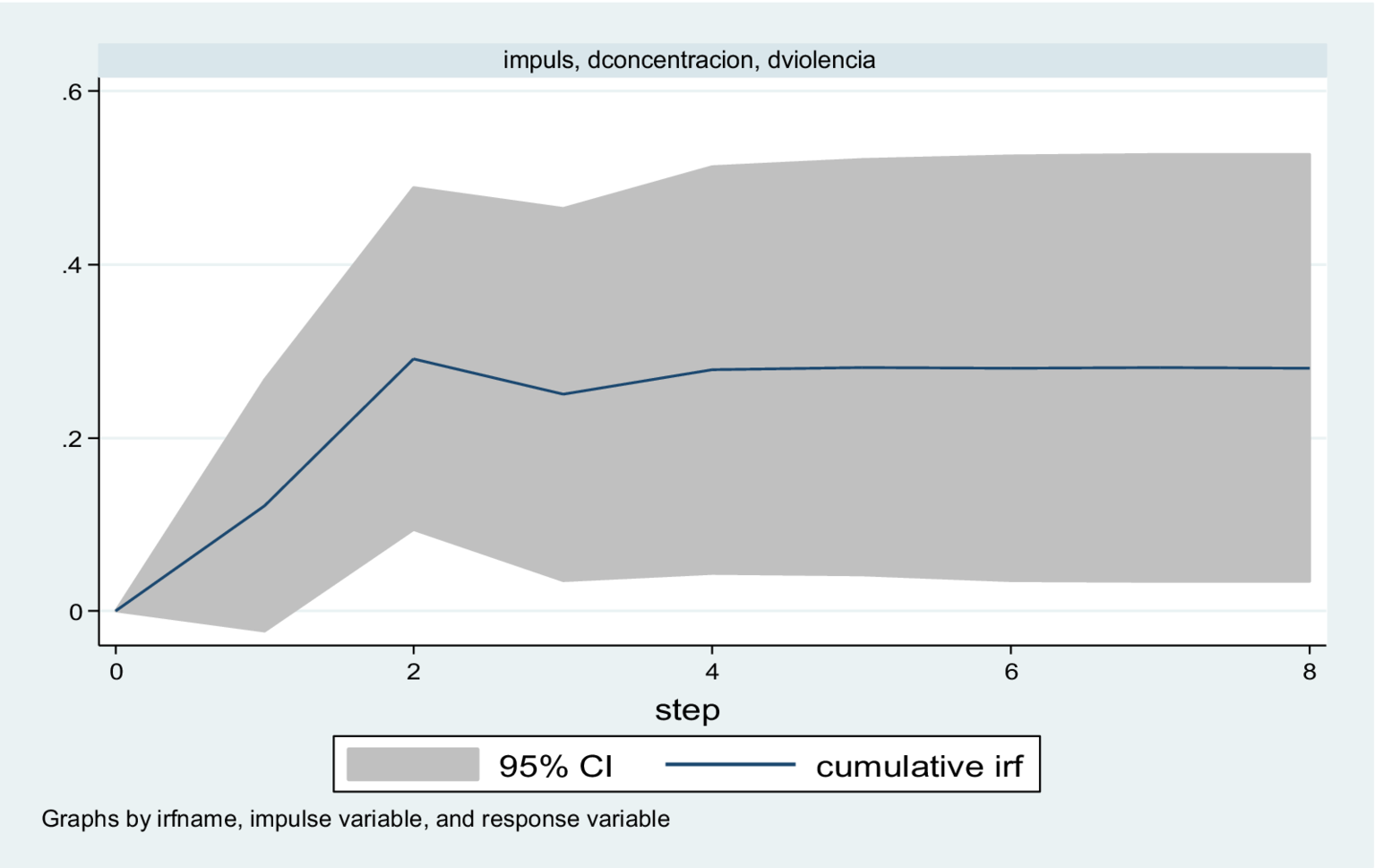

The narrative and the analytical narrative indicate that, in a hybrid regime, a higher degree of political power concentration causes a higher rate of political violence. The estimation of the Vector Auto-regression model allows us to analyze the response of the violence rate to a shock in the concentration index. Following an unexpected increase in the concentration of political power, the violence rate shows an initial increase of approximately 0.3 percentage points above its initial value. Subsequently, the effect attenuates slightly and stabilizes at around 0.2 percentage points above the baseline, maintaining this level throughout the period.

Discussion/Conclusion:

The theoretical model proposed in this paper suggests an explanation of political violence that diverges from the explanations offered by traditional theories. We suggest that the theoretical model proposed here captures the historical logic of the relationship between violence, political clientelism, and exclusion in Colombia, a country with a relatively long tradition as a formal democracy (since 1958), leading us to interesting conclusions that have not been proposed so far in the literature on violence in Latin America.

1 Introduction

The political violence literature suggests that autocratic regimes use political violence during their emergence and consolidation stages. However, once these regimes have consolidated their power, an institutional equilibrium of peace is established, and the threat of coercion deters opposition. At the other end of the spectrum, full democracies tend to have peaceful conditions because the regime allows for the pursuit of non-violent solutions to political conflicts. In between these two extremes lies a continuum of hybrid regimes with elements of both autocracy and democracy. These hybrid regimes tend to exhibit higher levels of political violence to discourage veto and control actions by the population, ensuring the preservation of the status quo (Fein, 1995; Hegre et al., 2001; Davenport, 2007; Kristine and Hultman, 2007; Gleditsch and Ruggeri, 2010; Hegre, 2014).

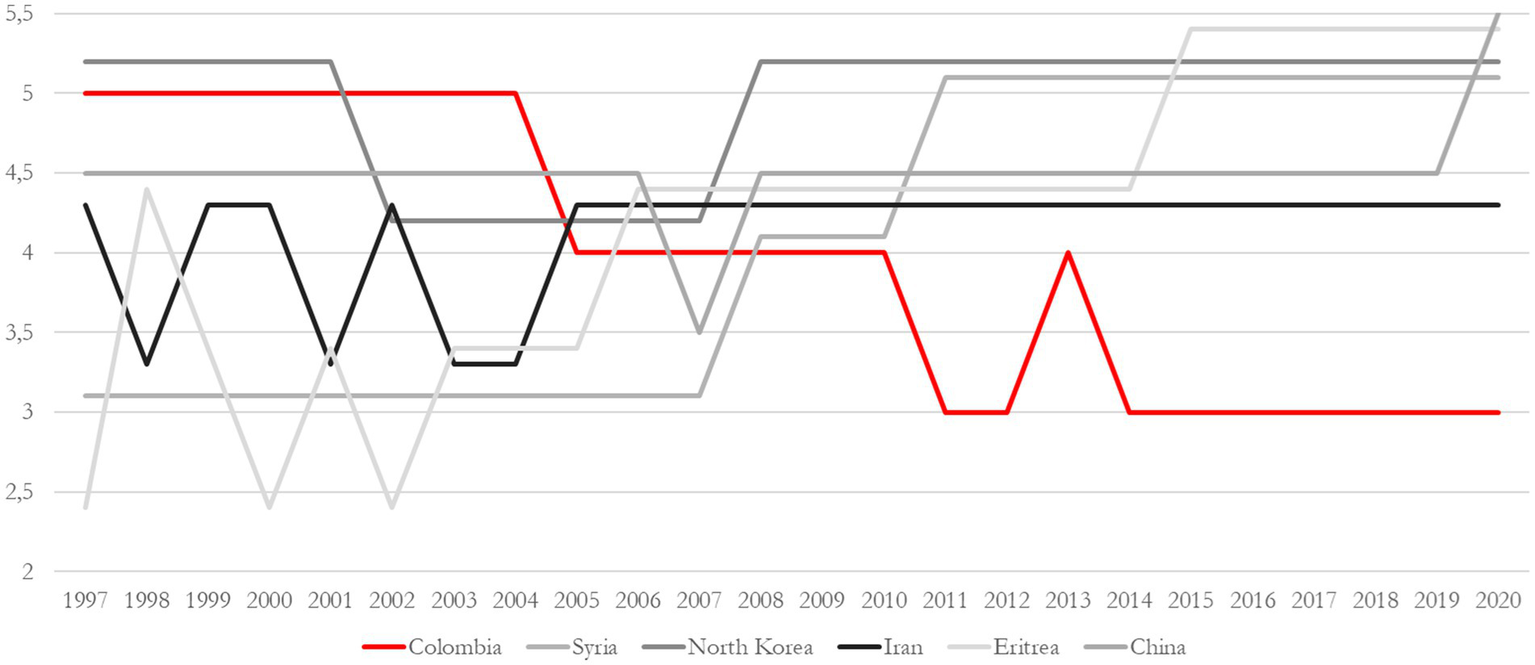

The relationship between political violence and the type of political regime has often been depicted as following an “inverted-U” pattern (Hegre et al., 2001). However, it is not always the case that political violence in hybrid regimes is higher than in extreme regimes (Sambanis, 2001; Vreeland, 2008; Peic and Reiter, 2011). Colombia can be characterized as a hybrid regime and has historically experienced endemic political violence. The country has had periods of extreme violence, such as during 1997–2004, as well as periods of relative calmness (2011–2020), during which its levels of violence have been lower than those observed in the autocratic regimes presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Political violence. Source: polity IV project.

As can be seen in the figure, the autocracies of North Korea, Eritrea, and Syria implemented terror policies for twelve, five, and nine years, respectively, during 2008–2020. The inverted-U theory cannot account for the recent decline in violence in Colombia or its increase in the other countries depicted in Figure 1 in terms of their political regime types. A different approach to understanding the determinants of political violence is the opportunity cost analysis. According to this line of thought, when formal employment is widely available, the likelihood of individuals engaging in violent activities, including political violence, is lower (Grossman, 1991; Iyengar et al., 2011; Beath et al., 2012). However, Berman et al. (2011) find a negative relationship between unemployment and political violence, and the contributions of Bahney et al. (2010, 2013) also challenge this approach. Another variation of the opportunity cost approach posits that insurgents are motivated by “greed” and their actions reflect an attempt to capture the government for personal gain (Collier and Hoeffler, 1999, 2004; Suhrke, 2007, p. 1301). This hypothesis, however, has been disputed. Ultimately, opportunity cost approaches to political violence do not offer significant explanatory power.

We present a theory of political violence in hybrid regimes that is based on rational behavior assumptions, but does not require the inclusion of variables such as unemployment, wages, or profits. Our theory explains political violence by using political parties as the units of analysis for two main reasons: 1) political parties are key actors within a political regime, and it is through them that the democratic or authoritarian character of the regime can determine political violence. Our approach differs from the counterinsurgency and terrorism approach in that in our theory, controlling political power is the ultimate objective of political parties. Our explanation is based on the rational behavior of political parties seeking to obtain and maintain political power in an electoral democracy with problems. Our methodology follows the Analytical Narratives of Bates et al. (1998), and we present a historical reconstruction of political violence in a hybrid regime with a wide range of institutional variations: Colombia, our case study.

Colombia provides an interesting case study as it not only challenges the “Inverted-U” hypothesis, but also presents an exceptional range of institutional features. On one hand, its party system has been characterized by intensive clientelism throughout its history, while on the other hand, its political violence and types of political parties have been variable. During the first stage of our analysis (1946–1991), political parties represented elite groups in society, but after 1992, there has been a political opening with the participation of non-elite political parties (Munshi, 2022). However, both types of parties have adopted clientelistic practices. The Colombian party system has a unique stable and self-sustaining clientelistic structure, which is a key feature of its democratic regime. In Colombia, political parties have used clientelism to manage the relative closure of the political regime and social exclusion, two equally endemic problems (Gutiérrez-Sanín, 2012; 2014; Moncada, 2016). The clientelistic control of the Colombian political regime by political parties is a chronic means of personal material wealth accumulation, which self-perpetuates by financing winning candidates in national elections. Thus, clientelism should not be viewed as just another element in the Colombian political game; it is, in fact, the structural element of articulation between society and the political class (Leal and Dávila, 2010).

Given the institutional weaknesses of Colombian democracy, the existence of structural political violence associated with the characteristics of the clientelistic political regime raises an intriguing question: what is the mechanism that underlies the relationship between the degree of concentration of political power in the clientelistic hybrid regime and the political violence exerted by the parties? In this paper, we introduce a theoretical model in which we separate the rules of the political regime game from its outcomes, following Przeworski (2000). The structure of the democratic regime defines the institutional framework, and the instrumental rationality of each party is defined by its clientelistic behavior. We represent both the institutional framework and the instrumental rationality of each party in our model of the political economy of violence with clientelism. Each of these elements is identified using the methodology of analytical narratives (Bates et al., 1998). In the reconstruction of the historical process of political violence, we identify not only the key actors but also the strategies and sets of information used in the context of a hybrid regime. The narrative allows us to precisely identify the way the actors use their information sets to choose their strategy. In the second stage, the political actors and their strategies, identified in the historical reconstruction of political violence, are modeled using game theory. The Nash equilibrium of the game will allow us to explain political violence in the long run in Colombia.

The present study investigates the intricate relationship between long-term political violence and the concentration of political power that political parties hold. Specifically, we explore the extent to which political violence is a rational choice in a hybrid regime where access to political channels of participation is limited. By examining the interplay between political power concentration and political violence, this paper sheds light on the underlying mechanisms driving violence in such contexts (Ripsman, 2007; Hughes, 2010; Saiya, 2021). Next, we will provide some methodological clarifications on the variables of legislative power concentration and political violence used in the reconstruction of the complex historical process of political violence in Colombia, as well as in the econometric analysis.

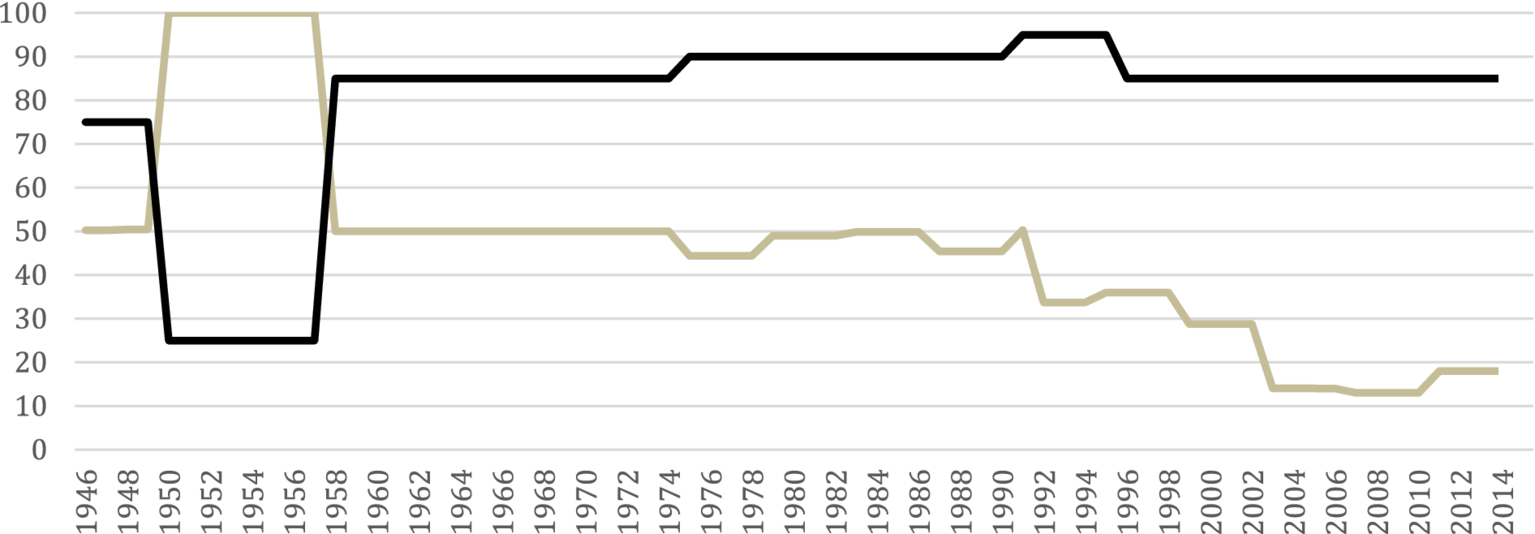

1.1 Political power concentration

Following the Democratization index (D) provided by the Polity IV Project, several categories are identified: Full Democracy (10), Flawed democracy (6 to 9), Open Anocracy (1 to 5), Closed Anocracy (−5 to 0), and Autocracy (−10 to −6). A lower index indicates more limited channels of access to power in a political regime, which suggests a less perfect democracy. To facilitate interpretation and analysis, we transform the index D using a linear transformation, namely , where ranges from 0 to 100 (Figure 2; Tables 1, 2). The interpretation of each political regime category characterized by the Democratization index is described in Table 1.

Figure 2

Time series of the indexes of democratization and concentration of political power in Colombia. Source: prepared by the authors. The dark line corresponds to the D democratization index time series and the clear line to the PPC index time series.

Table 1

| D | Type of political regime |

|---|---|

| 100 | Full democracy: these are political regimes where civil liberties and fundamental political freedoms are not only respected but also bolstered by a political culture conducive to the flourishing of democratic principles. These nations have a robust system of governmental checks and balances, an independent judiciary whose decisions are enforced, well-functioning governments, and diverse and independent media. Such nations experience only occasional issues in their democratic functioning. Most countries in Western Europe are considered full democracies, with Norway achieving the highest global score |

| 80–99 | Flawed democracy: these are political regimes where elections are held and basic liberties are respected. However, there are significant shortcomings such as an underdeveloped political culture, low levels of political participation, and governance issues |

| 55–79 | Open anocracy: anocracy or semi-democracy is generally defined as a form of government that combines democratic and autocratic elements, or as a ‘regime that blends democratic and autocratic features’. It is considered an open anocracy when there are competitors who do not come from the elites |

| 25–54 | Closed anocracy: it is considered a closed anocracy when competitors exclusively come from the elites |

| 0–24 | Autocracy: an autocracy is a political regime in which a ruler has absolute control and decision-making power over all state matters and all people within the country |

Democratization index and types of political regime.

Source: polity IV project.

Table 2

| Year | V | PPC | ΔGDP | D | Year | V | PPC | ΔGDP | D | PT | Year | V | PPC | ΔGDP | D | PT | Year | V | PPC | ΔGDP | D | PT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | 12 | 50 | −2 | 75 | 1964 | 34 | 50 | 6.17 | 85 | 1982 | 32 | 49 | 0.95 | 90 | 60 | 1999 | 59 | 29 | −4.20 | 85 | 100 | |

| 1947 | 12 | 50 | −1 | 75 | 1965 | 32 | 50 | 3.60 | 85 | 1983 | 32 | 50 | 1.57 | 90 | 60 | 2000 | 63 | 29 | 2.92 | 85 | 100 | |

| 1948 | 16 | 50 | 0.58 | 75 | 1966 | 30 | 50 | 5.35 | 85 | 1984 | 32 | 50 | 3.35 | 90 | 60 | 2001 | 47 | 29 | 1.47 | 85 | 100 | |

| 1949 | 30 | 50 | 1.70 | 75 | 1967 | 29 | 50 | 4.20 | 85 | 1985 | 40 | 50 | 3.11 | 90 | 60 | 2002 | 66 | 29 | 1.93 | 85 | 100 | |

| 1950 | 30 | 100 | 2.81 | 25 | 1968 | 30 | 50 | 6.12 | 85 | 1986 | 48 | 50 | 5.82 | 90 | 80 | 2003 | 53 | 14 | 3.86 | 85 | 100 | |

| 1951 | 33 | 100 | 3.12 | 25 | 1969 | 21 | 50 | 6.37 | 85 | 1987 | 52 | 45 | 5.37 | 90 | 80 | 2004 | 45 | 14 | 4.87 | 85 | 100 | |

| 1952 | 43 | 100 | 6.31 | 25 | 1970 | 21 | 50 | 6.74 | 85 | 1988 | 63 | 45 | 4.06 | 90 | 80 | 2005 | 39 | 14 | 4.72 | 85 | 80 | |

| 1953 | 32 | 100 | 6.08 | 25 | 1971 | 23 | 50 | 5.96 | 85 | 1989 | 65 | 45 | 3.41 | 90 | 80 | 2006 | 40 | 14 | 6.84 | 85 | 80 | |

| 1954 | 24 | 100 | 6.92 | 25 | 1972 | 23 | 50 | 7.67 | 85 | 1990 | 69 | 45 | 4.28 | 90 | 100 | 2007 | 39 | 13 | 7.52 | 85 | 80 | |

| 1955 | 31 | 100 | 3.91 | 25 | 1973 | 23 | 50 | 6.72 | 85 | 1991 | 78 | 50 | 2.00 | 95 | 100 | 2008 | 34 | 13 | 3.55 | 85 | 80 | |

| 1956 | 37 | 100 | 4.06 | 25 | 1974 | 24 | 50 | 5.75 | 85 | 1992 | 77 | 34 | 4.04 | 95 | 80 | 2009 | 29 | 13 | 1.65 | 85 | 80 | |

| 1957 | 37 | 100 | 2.23 | 25 | 1975 | 24 | 44 | 2.32 | 90 | 1993 | 75 | 34 | 5.39 | 95 | 100 | 2010 | 27 | 13 | 3.97 | 85 | 80 | |

| 1958 | 46 | 50 | 2.46 | 85 | 1976 | 26 | 44 | 4.73 | 90 | 40 | 1994 | 70 | 34 | 5.81 | 95 | 100 | 2011 | 26 | 18 | 6.59 | 85 | 60 |

| 1959 | 37 | 50 | 7.23 | 85 | 1977 | 28 | 44 | 4.16 | 90 | 40 | 1995 | 65 | 36 | 5.83 | 95 | 100 | 2012 | 31 | 18 | 4.04 | 85 | 60 |

| 1960 | 33 | 50 | 4.27 | 85 | 1978 | 27 | 44 | 8.47 | 90 | 40 | 1996 | 67 | 36 | 2.05 | 85 | 100 | 2013 | 25 | 18 | 4.87 | 85 | 80 |

| 1961 | 32 | 50 | 5.09 | 85 | 1979 | 30 | 49 | 5.38 | 90 | 60 | 1997 | 60 | 36 | 3.43 | 85 | 100 | 2014 | 24 | 18 | 4.39 | 85 | 60 |

| 1962 | 31 | 50 | 5.41 | 85 | 1980 | 31 | 49 | 4.09 | 90 | 60 | 1998 | 56 | 36 | 0.57 | 85 | 100 | 2015 | 23 | 17 | 3.05 | 85 | 60 |

| 1963 | 32 | 50 | 3.29 | 85 | 1981 | 36 | 49 | 2.28 | 90 | 60 |

Violence Series (V), PPC, Real GDP Growth Rate (ΔGDP), Political Terror (PT), and Democratization (D).

Source: compiled by the authors. National Registry of Colombia, National Police, Bank of the Republic of Colombia, Polity IV Project, and Political Terror Scale. Violence (V), CPP, Real GDP Growth Rate (ΔGDP), Political Terror (PT), and Democratization (D).

One of the fundamental constituents of a political regime is its legislative power. This power encompasses a significant portion of the weights and measures that are applied to other components of the political regime, as it grants public authority to create and pass laws, and to exercise political control. The level of accessibility to power in a political regime is directly related to the inclusivity of its legislative component, in which players possess veto power, are independent of the governing party, and have broad representativeness. This aspect is evident in full democracies, such as Canada, Norway, Sweden, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Hybrid regimes are characterized by political parties that possess a medium to low degree of institutionalization, exhibit limited representativeness, and are segregated along spatial, ideological, and sociodemographic lines. These attributes are common among many Latin American hybrid regimes, including Colombia, as noted by Freidenberg and Levitsky (2007).

In hybrid regimes, an increase in political concentration within the legislative power has been linked to a greater likelihood of political violence. Two scenarios can be distinguished in this regard: 1) when legislative power concentration increases within an opposition party, the ruling party may use systematic political violence to neutralize such opposition, often by shutting down parliament and replacing it with a pro-regime alternative1; and 2) when the political regime is classified as a flawed democracy (scoring between 80 and 99) or an anocracy (scoring between 25 and 79), and political parties in the legislative body have limited representativeness, higher levels of political exclusion can be expected, leading to a corresponding increase in political violence.

In our study, we aim to define and measure the political power of a party in a hybrid regime. Specifically, we define political power as the percentage of seats held by a political party in the legislative body. To measure the concentration of political power, we employ the Political Power Concentration Index (PPCI) proposed by Amador (2017), which is based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, which is defined as the sum of the squares of the percentage of seats held by each political party in the parliament, such that PPC = where represents the percentage of seats held by the political party in the parliament. Building on Amador's (2017) work, we use the PPC Index to measure the degree of concentration of political power per year in hybrid regimes. The index is calculated for the period 1946–2014, and its values provide insight into the level of political power concentration in the selected regimes during this period. By analyzing the trends and changes in the PPC Index over time, we can gain a better understanding of the dynamics of political power and its distribution within these hybrid regimes.

When there is a significant concentration of political power, implying that only a few political parties control access to power and bureaucracy, the degree of democratization in the political regime tends to be low. This situation is primarily attributed to politicians who rely on narrow, highly exclusionary, and clientelistic bases of representation, heavily dependent on clientelism. As shown in Figure 2, a higher Political Power Concentration (PPC) index corresponds to a lower level of democratization in the political regime (see Appendix). In other words, there is a long-term equilibrium relationship between the series considered, suggesting that in Colombia’s hybrid regime, an increase in the concentration of political power within the legislative branch has corresponded to a reduction in the level of democratization within the political system.

1.2 Polítical violence

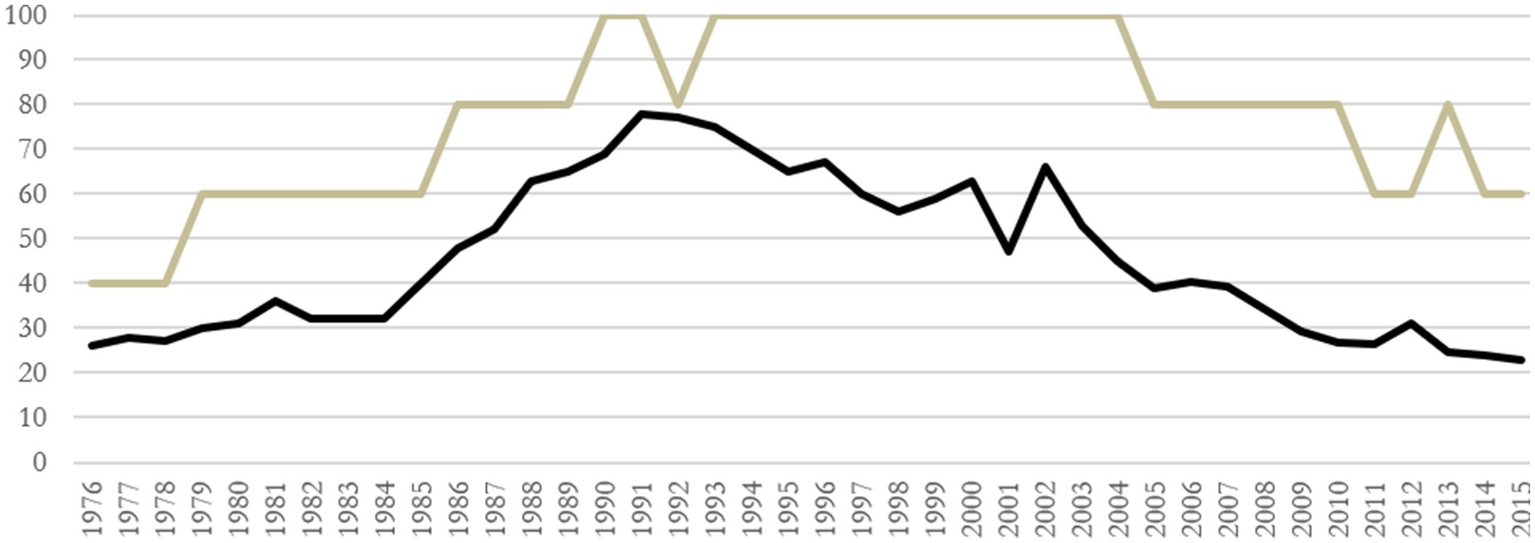

The level of political violence in each country is annually assessed using the political terror scale (TP). This scale is developed by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the US Department of State. To facilitate analysis, we apply a linear transformation to the TP scale (see Figure 3; Table 4). The interpretation of the transformed PT scale is described in Table 4.

Figure 3

Indexes of political violence (political terror scale) and homicidal violence in Colombia. Source: prepared by the authors. The dark line corresponds to the violence index series and the clear line to the political terror scale series.

It can be observed that it is only possible to use the political terror scale in our research from 1976 onwards. Instead, we use the homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants as a proxy variable for political violence, which is available from 1946, allowing us to cover an additional 30-year period. To ensure that the homicide rate is an appropriate proxy for political violence, we compare their behaviors during the years 1976–2015, as shown in Figure 3. A strong temporal association can be observed between the two variables, indicating that an increase in homicidal violence corresponds to a higher level of political violence (see Figure 3; Table 2). This finding is consistent with previous literature, which suggests that political violence has played a significant role in shaping the long-term trend of other forms of homicidal violence in Colombia. The Appendix provides statistically robust evidence for this observation (see: Gutiérrez-Sanín, 2012, p. 62).

The paper is organized as follows.

In section 2, we employ the Political Power Concentration (PPC) and Violence (V) indices to explore their relationship during the period of 1946–2014. Based on documentary evidence, we contend that increases in the PPC Index lead to increases in political violence, which in turn contributes to higher levels of homicidal violence. In section 3, we introduce a political competition model for legislative control, in which political parties use clientelism and political violence. Parties employ clientelism to secure seats in the legislature and political violence to block access to power by those who might threaten their relative position in the hybrid political system. This political economy model allows us to theoretically explain the impact of political power concentration on political violence. In section 4, we present the empirical evidence by estimating a Vector Auto-regressive (VAR) model using PPC, V, and real GDP growth rate series. Finally, in section 5, we draw conclusions and offer suggestions for future research.

2 Narrative on political regime, violence and exclusion

Our analysis period spans from 1946 to 2015, which we have divided into four distinct periods based on political power concentration and violence. Prior to 1946, Colombia was subject to intermittent armed conflicts between its two official political parties. During the 19th century, land and population control, rather than ideological differences, were the primary drivers of these confrontations. The largest of these conflicts was the 1,000 Days War (1899–1902), which resulted in conservative victory and the imposition of a restricted political regime until 1934, characterized by autocracy from 1902 to 1910 and closed anocracy from 1911 to 1934. The liberal governments (1934–1946) made some efforts to modernize the country, but continued to rely heavily on traditional land-based privilege. By the end of this period, conservative agents began to engage in increasingly bold acts of violence in an attempt to regain control of political power.

2.1 Period of La Violencia (1946–1958)

During 1946–1950, the conservative party was in power under Mariano Ospina Perez. It was widely known that the liberal party was poised to win the majority in the 1947 legislative elections. To counterbalance the liberal party’s influence, the conservatives offered government positions to some of their leaders as part of a diplomatic effort. Meanwhile, the conservatives resorted to illegal methods of coercion against liberal voters in rural areas and small towns. The persecution of liberals was carried out not only by para-institutional criminal forces, affiliated with the police through local branches of the conservative party, but also through the media, which promoted violence as a legitimate means of self-defense against liberals (Bailey, 1967). As a result of the increasing violence against liberal voters and local leaders, the liberal party leadership in Bogota withdrew from the government in 1947 (Medina, 1989; Pécaut, 2012).

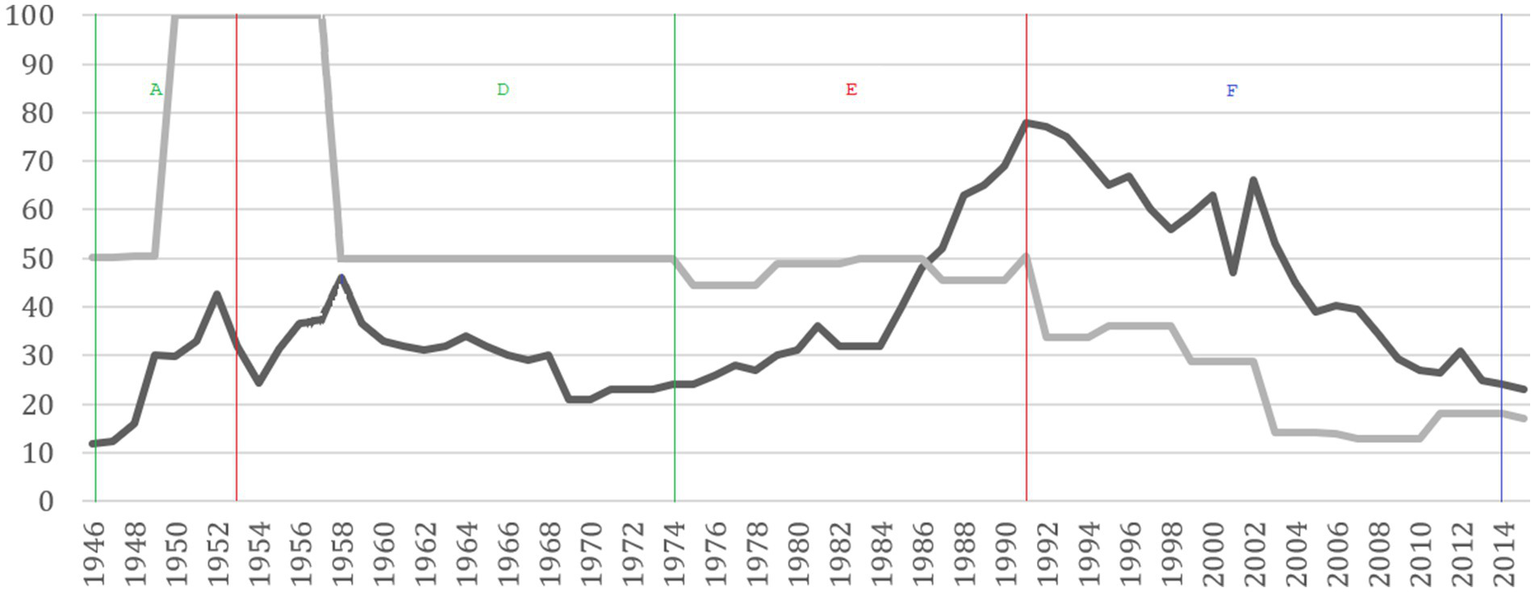

The conservatives, under the leadership of Ospina Perez, maintained that the state of the country necessitated the enactment of a State of Emergency, which they did with Decree 3518 on November 9, 1949. This State of Emergency allowed for a broader use of state forces in coercive political violence, the suspension of congress, the prohibition of the right to public assembly, the dissolution of regional and local legislatures (asambleas departamentales and concejos municipales), and the closure of the press. Due to the extreme political violence perpetrated by the conservative party, the liberals, under the leadership of Dario Echandia, did not participate in the 1949 elections, and conservative candidate Laureano Gomez won the presidency unopposed. Additionally, Congress remained closed until 1951, when new elections were held, but the liberals once again abstained from participating. Consequently, conservative representation increased to 100% in both the Senate and the House of Representatives (Jaramillo and Franco, 2005). During the analyzed period (Table 3; Figure 3), the PPC Index reached its maximum value of 100 (Palacio, 2006). This period was characterized by an unprecedented concentration of power, and the conservative party wielded increasingly greater levels of political violence (Column A — Figure 4).

CLAIM 1: During the period of La Violencia (1946–1958), the political regime was characterized as a closed anocracy. The Liberal party held a high concentration of legislative power, as an opposition majority, which led the Conservative party, as the ruling party, to resort to increasing political violence against the Liberal party. The Conservative party utilized political violence as a means of preserving its position of dominance within the political regime (Column A — Figure 4 ). The above demonstrates that in this stage, high concentration of political power causes or explains a high degree of political violence.

Table 3

| Series | Trace statistic | 5% critical value | Cointegration | Corr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D and PPC | 5.68a | 15.41 | Yes | −0.81 |

| TP and V | 1.02a | 3.76 | Yes | 0.78 |

Johansen cointegration test results.

Source: prepared by the authors.

There is at least one cointegration vector.

Figure 4

Index of political power concentration and violence in Colombia. Source: Compiled by the authors. The dark line corresponds to the violence series, while the light line represents the series of the political power concentration index.

Table 4

| Nivel | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0–20 | In countries where the rule of law is well-established, individuals are generally not imprisoned due to their political beliefs, and cases of torture are rare and exceptional. Additionally, politically motivated homicides are extremely uncommon |

| 21–40 | There is a low incidence of imprisonment related to non-violent political activities. While the number of affected individuals is limited, cases of torture and physical assault are rare. Additionally, politically motivated killings are infrequent |

| 40–60 | In countries characterized by this level of political terror, there is widespread and systematic political imprisonment, or a history thereof. Political killings and other forms of brutality, including torture, are frequent. The practice of indefinite detention, with or without trial, as a means of punishing individuals for their political views, is commonly accepted |

| 60–80 | At this level of political terror, violations of civil and political rights have become widespread and affect a large portion of the population. Acts such as murder, disappearance, and torture are common. Although pervasive, this level of terror is particularly directed towards those engaged in political or intellectual activities |

| 80–100 | The terror has permeated throughout the entire population. Leaders in these societies have no limits or restrictions on the methods or extent to which they pursue their personal or ideological goals |

Levels and interpretations of the political terror scale.

Source: Mark et al. (2017).

Table 5

| 1978 | 1988 | 1995 | 1999 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | Poverty rate | 80% | 65% | 60% | 64% |

| Misery rate | 45% | 29% | 21% | 23% | |

| Urban | Poverty rate | 70% | 55% | 48% | 55% |

| Misery rate | 27% | 17% | 10% | 14% | |

| Rural | Poverty rate | 94% | 80% | 79% | 79% |

| Misery rate | 68% | 48% | 37% | 37% |

National, urban and rural poverty indicators in Colombia, 1978–1990.

Source: World Bank.

Table 6

| Unit root test results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serie | Nivel | First differencing | Conclusion at the 5% significance level | ||

| ADF | Violence | −1.819 | −8.923 | I (1) | |

| Concentration | −1.378 | −8.262 | I (1) | ||

| ΔGDP | −5.038 | −11.016 | I (0) | ||

| Critical values | 1% | −3.555 | |||

| 5% | −2.916 | ||||

| Phillips-Perron | Violence | −1.872 | −8.923 | I (1) | |

| Concentration | −1.441 | −8.262 | I (1) | ||

| ΔGDP | −4.999 | −11.333 | I (0) | ||

| Critical values | 1% | −3.555 | |||

| 5% | −2.916 | ||||

| Johansen cointegration test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Trace statistic | 5% critical value | Cointegration |

| Violence, concentration and ΔGDP | 35.22 | 15.41 | No |

| Granger causality test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Regressor | Dependent variable | Correlation | Causality |

| Concentration | Violence | 0.032* | Causality |

| Violence | Concentration | 0.752 | Non-Causality |

| ΔGDP | Violence | 0.237 | Non-Causality |

| Violence | ΔGDP | 0.279 | Non-Causality |

| Concentration | ΔGDP | 0.052 | Non-Causality |

| ΔGDP | Concentration | 0.205 | Non-Causality |

| All | Violence | 0.020* | Causality |

| All | Concentration | 0.467 | Non-Causality |

| All | ΔGDP | 0.053 | Non-Causality |

VAR model.

* Level of significance at 5%.

Source: prepared by the authors.

During the period of La Violencia, institutional change was a political act. The political regime at the time was exclusionary, not only because it was based on an extreme conservative ideology, but also due to the clientelist relationship between the state, the political parties, and the population. The conservative party resorted to legal repression in order to maintain their dominance in the political regime, which eventually led to progressively more violent and illegal actions by both parties. This short-term approach to political control proved to be too costly, and the party leaders agreed to a long-term solution by sharing political positions on a 50/50 basis, less than their maximum of 100. This contributed to the de-escalation of violence and eliminated the threat posed by General Rojas Pinilla (Palacio, 2006; Gutiérrez-Sanín, 2012; Guisao-Álvarez, 2022). With the general’s departure, the traditional parties reached an agreement called the National Front (Palacio, 2006).

2.2 Period of the National Front (1958–1974)

The National Front emerged as a response to the perceived threat posed by General Rojas, as documented by Hartlyn (1993). This pact, entered into by the traditional parties, aimed to mitigate this threat. However, it is important to note that the National Front primarily catered to the interests of the existing elite class affiliated with the traditional parties, resulting in a consolidation of power akin to a political cartel (Period 1958–1969: Figure 1). Under the National Front regime, both the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party had dual representation, with two governments each. The Liberal Party governments were led by Alberto Lleras (1958–1962) and Carlos Lleras (1966–1970), while the Conservative Party governments were headed by Guillermo Leon Valencia (1962–1966) and Misael Pastrana (1970–1974).

Consequently, the establishment of the National Front resulted in a partial opening of the political regime as the traditional parties acknowledged each other as legitimate political actors entitled to participate in the channels of power access. This period was characterized by a political cartel with explicit collusion. The concentration of political power (PPC) decreased to 50% during this period, while violence also decreased (Figure 4 — Column D). Even though the National Front allowed some degree of political competition between personality factions within each elite party, it ultimately served as an agreement for power sharing among the elites. The competition within each party contributed to the dilution of partisan political violence and the deconcentration of political power among different regional and local leaders affiliated with both parties. In other words, the National Front played a decisive role as a determinant of power deconcentration through partisan factionalism, and as stated by Hartlyn (1993) and González (2003a,b) it contributed significantly to reducing political violence during the 1958–1974 period (Figure 4 – Column D).

CLAIM 2: During the National Front period (1958–1974), the political regime can be characterized as a flawed democracy. The National Front constituted an explicit agreement between the two elite parties aimed at achieving an equitable distribution of power. This agreement effectively reduced the concentration of political power and effectively curtailed partisan violence (Column D — Figure 4 ). The above shows that a lower concentration of political power in a hybrid political regime (in this case, a flawed democracy) causes or explains a lower level of political violence.

The National Front, as an institution formalized through the Benidorm Pact and the March Pact, had a significant impact during its existence. It fostered mutual recognition among the militants of political parties, treating them as political actors with equal opportunities in electoral and democratic struggles. As a result, the space for engaging in violent actions against political opponents diminished. The confrontations that had previously taken place through physical and armed means during elections were replaced by peaceful electoral competition, adhering to the principles of liberal democracy. Consequently, the need to dismantle the National Front emerged, as it had served its purpose of pacifying and democratizing the country. While it was the political actors who ultimately decided to deactivate the National Front, initiating the period of dismantling (1974–1991), the decision-making process transitioned from a formalized structure to an informal one. Each political party, benefiting from the National Front, had established electoral and political foundations through their sustained control over the resources of the bureaucracy and public sector at both national and subnational levels.

2.3 Period of dismantling of the National Front (1974–1991)

During the period from 1974 to 1991, the concentration of political power (PPC) index remained at approximately 50%, with minor fluctuations attributed to the involvement of small movements such as the National Popular Alliance, as well as dissident factions from the traditional political parties, namely the Liberal Revolutionary Movement and the Patriotic Union (Figure 4). The prevailing political concentration, along with other factors, contributed to alarming levels of poverty during the 1960s and 1970s, leading to a fragmented democracy characterized by heightened levels of political and social exclusion (see Table 2). The issue of rural poverty was directly linked to extreme land concentration, a phenomenon that was widely discussed by non-elite socio-political associations such as the National Association of Peasant Users (ANUC), yet largely disregarded by the two dominant traditional parties. Social mobilization during this period provided fertile ground for the emergence of contemporary guerrilla groups, including the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Popular Liberation Army (EPL), and the April 19 Movement (M-19).

The response of elite parties to popular uprisings entailed the implementation of the “internal enemy” doctrine, characterized by heightened levels of repression and political persecution against left-wing political movements (LeGrand, 2003), particularly during the liberal governments of Alfonso López Michelsen (1974–1978) and Julio César Turbay Ayala (1978–1982) (Gómez-Suárez, 2020). The implementation of the Estatuto de Seguridad (Decree 1923 of 1978) effectively resulted in a partial military occupation of the civil sphere, with union leaders, intellectuals, and students becoming targets of police repression (LeGrand, 2003). The military forces were granted extrajudicial powers to exercise political repression both in urban and rural areas, which included illegal detentions, military trials of civilians, torture, and extrajudicial executions (Palacio, 2006).

During the administration of the conservative president Belisario Betancur (1982–1986), attempts were made to engage in negotiations with rebel groups. However, by that time, the policy of exterminating the left as an internal enemy had already been firmly established, both institutionally and through non-official channels. Despite the Betancur government’s introduction of a Pardon Law for guerrilla fighters and political leaders imprisoned by the previous administrations, political violence continued to escalate (Gómez-Suárez, 2020).

Since the end of the 1970s and throughout the 1980s, the country witnessed the rise of narco-terrorism, where drug trafficking organizations engaged in violent conflicts to control their illicit businesses and also targeted the state that sought to prosecute them. These trafficking organizations often provided support to paramilitary forces, despite the latter being associated with the state in its fight against guerrilla groups. Distinguishing between trafficking-related criminal violence and political violence is a challenging task as they are deeply intertwined (Duran-Martínez, 2018; Gaffney, 2018). The political violence perpetrated by paramilitary groups would not have been possible without the influx of drug money (Moncada, 2021; Gutiérrez-Sanín, 2022). Acts of political violence against political leaders and civil society organizations were primarily carried out by illegal groups distinct from the guerrillas, often through alliances among traffickers, paramilitary forces, and the armed forces (Clawson and Lee, 1996; Albarracín et al., 2020).

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia - People’s Army (FARC-EP) established their political party, the Patriotic Union (UP), in 1985. The UP aimed to represent non-elite social groups within the political sphere. In the legislative elections of 1986, the UP achieved significant participation, particularly at the local and regional levels (Leech, 2011). The aforementioned right-wing alliance interpreted this outcome as evidence of communist influence engulfing the country, leading to a violent extermination campaign that resulted in a minimum of 3,000 assassinations (Gómez-Suárez, 2007; Palacio, 2012). Despite the efforts of the liberal government under Virgilio Barco (1986–1990), the consolidation of these alliances, which engaged in assassinations, forced displacements, land seizures, torture, and kidnappings against UP leaders and sympathizers, could not be prevented. The political violence witnessed during this period, orchestrated and executed by elite parties through active participation or acquiescence, was unprecedented in Colombian history (Bejarano and Pizarro, 2005; Bejarano, 2011) (Table 5).

CLAIM 3: During the dismantling period of the National Front (1974–1991), the political regime was a flawed democracy. This concentration of power by elite parties resulted in high levels of political and social exclusion, leading to elevated levels of poverty and inequality. The elite parties effectively monopolized the channels of access to political power, denying participation to any other political actors. The political violence carried out by state or para-state agents during this period was unprecedented ( Figure 4 — Column E, Table 2 ). This period demonstrates that, in addition to the concentration of political power (which remained constant during this period), an increase in political and social exclusion levels (against emerging political actors) causes/provokes greater political violence.

2.4 Period of political decentralization (1991—present)

Following the enactment of the 1991 Constitution, new avenues for accessing political power became available for emerging parties (Palacio, 2006: 334–338).

These newly formed parties engage in collusion with illegal armed groups, including traffickers, paramilitary forces, and guerrillas, in the regions where they establish a presence. The objective of such collusion is to acquire sufficient resources to secure victory in subnational elections (Romero, 2003; Acemoglu et al., 2013). The illegal armed groups benefit from territorial security provided by these new local governments. Political violence adapts to the dynamics between the new parties, illegal groups, and the old oligarchies in each region (Eaton, 2006: 544). Specifically, collusion with guerrilla groups such as the ELN contributes to the emergence of new subnational oligarchies that replace the previous oligarchies responsible for the regional structures of the traditional parties (Eaton, 2006: 555; Peñate, 1999: 88).

The accommodation to these new dynamics resulted in extreme political violence during the 1990s (Hybel, 2020, p. 162; Figure 5—Column F). However, political violence tended to decrease during this period, not only due to the establishment of regional powers but also because all political actors (legal and illegal) recognized that in the new institutional context, alliances were more effective for gaining control over subnational governments (Steele and Schubiger, 2018, p. 59).

CLAIM 4: During the process of political decentralization (1991-present), the political regime in Colombia can be characterized as a flawed democracy. The expansion of channels for accessing political power allowed the participation of new non-elite parties. As a result, the concentration of political power decreased, diminishing the incentives to engage in political violence against rival parties or political actors. Consequently, political violence witnessed a decline during this period ( Figure 4 — Column F). The above demonstrates that a stable reduction in the concentration of political power causes/explains a reduction in political violence.

Figure 5

Index of political power concentration & violence in Colombia. Source: prepared by the authors.

Based on Claims 1–4, it can be inferred that within the framework of a hybrid political regime characterized by clientelistic parties, an increase (or decrease) in power concentration leads to a corresponding increase (or decrease) in political violence. Furthermore, if the concentration of political power results in heightened levels of poverty and inequality, it will further contribute to an escalation of political violence. Building upon the methodology of analytical narratives, the following section presents a model that encompasses the identified mechanism derived from the historical reconstruction of political violence in Colombia.

3 A theoretical model of hybrid regimes, clientelism and political violence

Our theoretical model operates on the assumption of a hybrid regime, wherein political parties function as political machines, as defined by Stokes et al. (2013). Recent studies by Stokes (2021) further elucidate how divided democracies, which fall under the category of hybrid regimes, tend to cultivate robust practices of political clientelism.

3.1 Political competition game for clientelistic control of the legislature

Each clientelist party strategically determines the number of seats it aims to control through clientelistic strategies. During the period of Violence (1946–1958), these strategies were characterized by traditional clientelism, which relied on relationships of servitude and loyalty primarily in rural settings. Subsequently, during the National Front era (1958–1974) and the period of National Front dismantling (1974–1991), clientelistic strategies were predominantly shaped by modern clientelism, which was based on bureaucratic labor relations. In the period of political opening (1991-Present), marked by political, administrative, and fiscal decentralization, these strategies are primarily influenced by a market-oriented form of clientelism (Leal and Dávila Leal and Dávila, 2002). In this new type of clientelism, territorial public procurement is awarded to private actors who offer the most advantageous deals for financing the victorious clientelist parties. We emphasize the distinct types of clientelism present in each period within our narrative, as monetary gains have been a driving force behind the concentration of political power, often accompanied by violence.

Therefore, it is important to observe that at different stages, clientelism materialized through classical clientelistic tools such as favoritism strategies utilizing public or private resources (Robinson and Verdier, 2013; Kramon, 2016) and vote-buying (Nichter, 2008). However, it is crucial to note that in other stages, such as the period of La Violencia, forms of coercion were employed, indicating a type of clientelism based on coercion within the framework of anocratic regimes. This interaction during this stage explains the use of clientelistic tools of a different nature from the traditional ones in contexts that Mişcoiu and Kakdeu (2021) describe as quasi-authoritarian. It should be noted, however, that clientelism during the period of La Violencia did not reduce violence; rather, it exacerbated it. Through the subordination relationships framed in traditional clientelism during La Violencia, political leaders of the Conservative party instructed their clients to use police forces to persecute opposing Liberals.

3.1.1 Income

Let denote the monetary value of the public goods required to fulfill all citizen demands in areas such as health, education, security, infrastructure, among others. Adapting Amador's (2017) model of political competition, let represent the monetary value of the public goods that the State is able to provide. The state is weaker as long as

gets closer to 1. The weakness of the state refers to its ability to adequately supply the necessary public goods in a democratic society. We define as a proxy for the level of poverty within a democracy. Conversely, hybrid regimes are characterized by the existence of a predatory state:

“By a predatory state, we mean a state that promotes the private interests of dominant groups within the state (such as politicians, the army and bureaucrats) or infuential private groups with strong lobbying powers” (Vahhabi, 2020, p. 233).

In a hybrid regime, when the intensity of state predation on public resources rises, it leads to an escalation in income inequality within the society. Let be the gini index. Each clientelist party acquires a clientelistic income

given its seats quota such that is the legislative body under the control of the clientelist parties. The term represents the monetary value of resources that clientelist parties capture to promote their own interests as well as those of the elite. The amount of resources that the parties plunder will increase as political and economic exclusion in the democracy intensifies, that is, as the parameters and increase. In order to obtain clientelistic income , the clientelist party must first gain control of the allocated seats quota in democratic elections, which involves implementing clientelistic strategies that incur certain costs.

3.1.2 Costs

The clientelist party incurs a cost to achieve control of a seats quota . This cost arises from financing its electoral organization during the election period and supporting its clientelistic networks. The average cost incurred by the clientelist party is equal to its marginal cost, implying that each clientelist party operates at the minimum possible average cost2. When subtracting the costs from the clientelistic income , the clientelist party can determine its benefits.

3.1.3 Benefits

Let be the legislative benefit function of the clientelist party such that is a distribution of legislative seats of clientelistic parties. Each clientelistic party simultaneously decides the amount of seats it seeks to have under its control through the exercise of clientelism. Each party executes a set of clientelistic strategies that involve all its typologies, at a cost captured by the cost function.

Therefore, we say that

is a game of legislative competition with complete information in which each clientelistic party chooses its strategy simultaneously. We assume that , that is, we assume that there are at least two political parties. Solving the game through the best response method, we have that:

Given that all parties have the same set of strategies and the same payoff function, is a symmetrical game. In consequence, the equilibrium is symmetric if such that . Hence,

if, and only if,

In consequence,

We have the following lemma.

LEMMA 1: Symmetrical equilibrium in the game — It holds that in the symmetric Nash equilibriumof the simultaneous game of bureaucratic competitionwith complete information, is the equilibrium seats quota of the clientelistic party. Hence,is the benefitof clientelist party i in the NE.

3.1.4 Index of political power concentration

Following the Hirschman–Herfindahl index, it can be stated that

is the index of political power concentration in the NE of the game . But

for each in the NE of the game . Consequently,

is the index of political power concentration in the NE of the game .

3.2 Political violence game

Following Amador (2017), each clientelist party must engage in another game to determine the level of violence it will employ in order to safeguard its control over the allocated seats quota and prevent persecution or political obstruction by rival parties. Let

be the expected benfit for clientelist party , where

represents the relative level of violence exerted by party i and determines the probability of successfully maintaining control over its benefits. It is assumed that all political machines employ the same technology for exerting violence, where represents the marginal cost associated with exercising such violence. For the aforementioned scenario, we define the game as a

political violence game with complete information, where each clientelist party simultaneously selects its strategy . We employ the best response method to solve the game. In , all parties share identical strategy sets and payoff functions, making it a symmetric game. In consequence, the equilibrium is symmetric if such that . Hence,

Hence, we have the following lemma.

LEMMA 2: Symmetrical equilibrium in political violence game – It holds that in the Nash equilibriumof the political violence gamewith complete information. Let is the equilibrium political violence of the clientelist party .

Based on Lemma 2, the equilibrium level of aggregate political violence, which is contingent upon the concentration of legislative political power, can be described as follows:

Therefore, we have the fundamental theorem of the proposed theory.

THEOREM 1: In a hybrid political regime, the level of political violence tends to be higher when there is a greater concentration of political power in the legislative branch. The primary objective of partisan political violence is to establish and validate social and political control over the channels through which access to political power is obtained, particularly in response to threats or political and military obstacles. Formally, this relationship can be expressed as follows: Therefore, if a hybrid political regime leads to increases in poverty or income inequality, ceteris paribus, partisan political violence is expected to rise as a means to suppress and undermine social mobilizations that challenge the existing status quo. The purpose of such violence is to weaken and dilute movements that seek to bring about significant social and political change.

Unlike Amador (2017), our fundamental theorem is articulated in terms of political power concentration, the monetary value of the public goods that the state is able to provide, the level of poverty, and the Gini index. Continuing with the application of the analytical narratives methodology, the following section introduces a regression model that examines the relationship between political violence and the concentration of political power, as identified in Theorem 1 and Claims 1–4.

4 Econometric evidence

To test our theoretical model, we employ a time-series method known as the Vector Auto-regression model (VAR). The VAR model is widely utilized for examining causal relationships and predictability by analyzing a system of equations that can identify endogenous variables based on their exogenous determinants. In order to determine the appropriate number of temporal lags in VAR systems, it is necessary to conduct error correction processes. These processes tend to yield more accurate results when applied to datasets with approximately 60 or more yearly observations (Enders, 2014). Fortunately, our case study meets this requirement with a total of 68 years of data, allowing us to effectively address regression errors and determine the optimal lag structure of the VAR model, as we will demonstrate in the subsequent analysis (see Table 6).

In a VAR (Vector Auto-regression) model, each variable is explained by its own lagged values as well as the lags of the other variables included in the estimation (Harris, 1995). The VAR approach eliminates the need for constructing a structural model, as all variables are treated as endogenous and each variable is considered a function of the lagged values of all the included variables, forming a simultaneous system that captures the interactions among the series. An important output derived from VAR models is the impulse response function, which indicates the causal impact or how one variable responds to shocks from the other variables included in the model. Thus, this type of model allows for the examination of the interdependence among the analyzed variables without specifying causality in a single direction or requiring the specification of a specific relationship among the variables (Arroyo et al., 2011).

We adopt a four-stage approach for our analysis. The first stage involves examining the unit root of the time series using the Dickey-Fuller Augmented Test (ADF). If the test indicates that the series are non-stationary, we employ the first differences method to address this violation. In the second stage, we employ the Johansen cointegration test to investigate whether the series are cointegrated, indicating the presence of a long-run equilibrium relationship between them. Moving on to the third stage, we estimate the VAR model and conduct an analysis of the Standard Granger Causality to explore the causal relationships among the variables. Lastly, in the fourth stage, we present an analysis of the cumulative Impulse Response Function (IRF) to examine the dynamic impact of shocks on the variables of interest over time.

The series utilized in the analysis include the homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants for the period 1946–2015, which serves as a proxy variable for political violence as discussed in Section 1. Additionally, the index of political power concentration and the real GDP growth rate were obtained from the Central Bank of Colombia (Banco de la República de Colombia).

4.1 Results test for integration order

The results of the unit root tests are presented in Table 6. The null hypothesis states that the time series is non-stationary, indicating a stochastic trend or the presence of a unit root. It can be observed that both the violence series and the concentration index series do not reject this null hypothesis based on the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips-Perron (PPE) tests, or both. However, in the case of the real GDP growth series (ΔGDP), the null hypothesis is rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis, suggesting that the real GDP series is stationary. To address the non-stationarity of the violence and concentration series, we apply first differences. Thus, we conclude that both series are integrated of order one, I (1).

4.2 Johansen cointegration test results

The Johansen cointegration test is conducted and the results are presented in Table 6. The null hypothesis of non-cointegration between the violence, growth, and concentration series is not rejected. This implies that there is no long-run equilibrium relationship or cointegration among these series. This finding is a necessary condition for estimating a Vector Autoregressive (VAR) model.

4.3 Granger causality test

Expanding the analysis, the Granger Causality test is conducted to examine the causal relationship among the variables: the index of political power concentration, the violence rate, and the real GDP growth rate. The results, presented in Table 6, indicate the presence of a causal relationship between the index of political power concentration and the violence rate. The correlation coefficient between these variables is found to be statistically significant, with a positive value of 0.032. Therefore, we can conclude that the level of political power concentration has a significant impact on the rate of violence in the country, while the reverse causality is not supported by the findings from the VAR model.

4.4 Impulse response function

One useful approach to analyze the dynamic relationships between variables is through the examination of their responses to exogenous shocks. Figure 5 displays the response of the violence rate to a shock in the concentration index. Following an unexpected increase in the concentration of political power, the violence rate exhibits an initial increase of approximately 0.3 percentage points above its initial value.

Subsequently, the effect attenuates slightly and stabilizes at around 0.2 percentage points above the baseline, maintaining this level throughout the period. This indicates that a higher degree of political power concentration corresponds to a higher violence rate during that time period. The VAR regressions provide additional empirical evidence regarding the structural impact of political power concentration in the Colombian parliament on long-term political violence within a hybrid regime. The results consistently indicate that an increase in political power concentration leads to a corresponding increase in political violence. This finding highlights the significant role played by the concentration of political power in shaping the level of violence experienced within the political system.

5 Final notes

We have conducted an in-depth analysis of Colombia’s long-term political violence, specifically focusing on partisan violence during the period 1946–1958 and the subsequent revolutionary internal armed conflict. Through an analytical narrative approach, we have constructed a comprehensive historical account of this case study, drawing attention to the fact that episodes of heightened violence (1946–1958 and 1982–2004) coincide with increased concentration of political power in the parliament, encompassing both the congress and the house of representatives.

This observed pattern has served as the foundation for our theoretical modeling, which employs game theory to elucidate the dynamics of partisan politics with a clientelistic framework within a hybrid political regime. The clientelistic parties within this model aspire to achieve the highest possible degree of political power concentration, as it enables them to advance policy agendas that cater to their support bases, primarily consisting of the societal elite and partisan affiliations.

The recourse to violence, as manifested in this hybrid regime context, is an expression of the parties’ imperative need to safeguard and assert their interests. It is important to note that this context falls somewhere between a full-fledged democracy and an autocracy, further underscoring the significance of the concentration of political power as a determining factor in shaping the dynamics of violence within the political landscape.

The theoretical model posits that, all other factors held constant, an increased level of political power concentration in the legislative branch will correspond to a higher level of political violence. To empirically test this prediction, we employ a VAR (Vector Auto-regression) time-series analysis using Colombian data. The VAR regression model successfully fulfills all necessary error correction and lag selection procedures, enabling us to accurately conduct Granger causality tests.

Through these predictive exercises, we validate the existence of a long-term relationship in Colombia, wherein political power concentration is causally linked to levels of violence. This finding aligns with the predictions put forth by our theoretical framework.

Our analysis distinguishes itself from other purely empirical studies by advancing the research agenda of analytical narratives. In this approach, meticulously constructed historical narratives of political processes serve as a guide for theory development. Despite its robust methodology and significant explanatory capabilities, this approach is not commonly adopted in the literature. However, it offers a valuable means of capturing the complexities and nuances inherent in reducing political violence within a hybrid political regime characterized by clientelistic partisan politics. By embracing this approach, we aim to provide a more accurate depiction of the challenges and opportunities associated with mitigating political violence in such contexts.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HG-S: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LO: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ Between 2005 and 2022, the political regime in Venezuela can be characterized as anocratic. In April 2017, the ruling government party, under the leadership of President Nicolas Maduro, dissolved the parliament following the opposition’s victory in the 2015 elections. In lieu of parliamentary proceedings, Maduro announced the election of a constitutionary assembly (ANC) to be held in June 2017. The ensuing period of political turmoil from April to June 2017 was marked by significant levels of political violence. The ANC assumed the role of the official party legislative until 2019. Similarly, Colombia was an anocracy from 1946 to 1955. In 1949, the conservative President Mariano Ospina dissolved the parliament, which had previously been dominated by the opposition since the 1947 elections. The use of a State of Emergency by the conservative party resulted in alarming levels of political violence, discouraging the liberals from participating in the 1951 parliamentary elections and effectively granting 100% of the seats to the conservatives. Likewise, Peru was an anocracy between 1991 and 2001. The government party, “Cambio 90,” led by President Alberto Fujimori, employed the military to dissolve the opposition-dominated parliament in April 1992 (Burt, 2006). Additionally, the government co-opted various branches of the state, including the judiciary, the Law Assembly, the Tribunal of Constitutional Guarantees, the Public Minister, and the General Comptroller Agency. This period was characterized by the political imprisonment of numerous individuals who had not committed any crimes, as well as the systematic persecution, intimidation, and detention of opposition leaders. In conclusion, these three cases illustrate the use of anocracy to consolidate political power through the suppression of oppositional voices and actions. The violence and coercion employed by these regimes serve as cautionary examples of the dangers of undemocratic governance.

2.^ Examples of clientelistic actions would be the purchase of votes, patronage, purchase of polling stations, bribes to local judges, etc.

References

1

Acemoglu D. Robinson J. Santos R. (2013). The monopoly of violence: Evidence from Colombia. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc.11, 5–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01099.x

2

Albarracín J. Milanese J. Valencia I. Wolff J. (2020). The political logic of violence: The assassination of social leaders in the context of authoritarian local orders in Colombia. Frankfurt: Peace Research Institute Frankfurt.

3

Amador C. (2017). Un modelo de elección pública sobre el régimen político, violencia y exclusión. Barranquilla: Universidad del Norte.

4

Arroyo J. Espínola R. Maté C. (2011). Different approaches to forecast interval time series: a comparison in finance. Comput. Econ.27, 169–191. doi: 10.1007/s10614-010-9230-2

5

Bahney B. Iyengar R. Johnston P. Jung D. Shapiro J. Shatz H. (2013). Insurgent compensation: evidence from Iraq. Am. Econ. Rev.103, 518–522. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.3.518

6

Bahney B. Shatz H. Garnier C. McPherson R. Sude B. (2010). An economic analysis of the financial records of al-Qa’ida in Iraq. SantaMonica, CA: RAND.

7

Bailey N. (1967). La Violencia in Colombia. J. Interam. Stud.9, 561–575. doi: 10.2307/164860

8

Bates R. Greif A. Levi M. Rosenthal J. Weingast B. (1998). Analytic narratives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

9

Beath A. Christia F. Enikolopov R. (2012). Winning hearts and minds through development? Evidence from a field experiment in Afghanistan. policy research working paper (6129). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

10

Bejarano A. (2011). Precarious democracies: understanding regime stability and change in Colombia and Venezuela. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

11

Bejarano A. Pizarro E. (2005). “From “Restricted” to “Besieged”: The changing nature of the limits to Democracy in Colombia” in The Third wave of democratization in Latin America: advances and setbacks. eds. HagopianF.MainwaringS. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

12

Berman E. Callen M. Felter J. Shapiro J. (2011). Do working Men Rebel? Insurgency and unemployment in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Philippines. J. Confl. Resolut.55, 496–528. doi: 10.1177/0022002710393920

13

Burt J. (2006). “Quien habla es terrorista”: The political use of fear in Fujimori’s Peru. Lat. Am. Res. Rev.41, 32–62. doi: 10.1353/lar.2006.0036

14

Clawson P. Lee R. (1996). “The Medellín and Cali Cartels” in The Andean Cocaine Industry. eds. ClawsonP.LeeR. (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

15

Collier P. Hoeffler A. (1999). Justice-seeking and loot-seeking in Civil War. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

16

Collier P. Hoeffler A. (2004). Greed and grievance in civil war. Oxf. Econ. Pap.56, 563–595. doi: 10.1093/oep/gpf064

17

Davenport C. (2007). state repression and the domestic democratic peace. Nueva York: Cambridge UniversityPress.

18

Duran-Martínez A. (2018). The politics of drug violence criminals, cops and politicians in Colombia and Mexico. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

19

Eaton K. (2006). The downside of decentralization: Armed clientelism in Colombia. Secur. Stud.15, 533–562. doi: 10.1080/09636410601188463

20

Enders W. (2014). Applied Econometric Time Series. 4th Edn. New York: Wiley. John Wiley.

21

Fein H. (1995). More murder in the middle: life-integrity violations and democracy in the world, 1987. Hum. Rights Q.17, 170–191. doi: 10.1353/hrq.1995.0001

22

Freidenberg F. Levitsky S. (2007). Organización informal de los partidos políticos en América Latina. Desarrollo Económico.46, 539–568.

23

Gaffney F. (2018). “Narcoterrorism in Colombia” in Historical perspectives on organized crime and terrorism. eds. WindleJ.MorrisonJ.WinterA.SilkeA. (London: Routledge), 157–168.

24

Gleditsch S. K. Ruggeri A. (2010). Political opportunity structures, democracy, and civil war. J. Peace Res.47, 299–310. doi: 10.1177/0022343310362293

25

Gómez-Suárez A. (2007). Perpetrator blocs, genocidal mentalities and geographies: the destruction of the Union Patriotica in Colombia and its lessons for genocide studies. J. Genocide Res.9, 637–660. doi: 10.1080/14623520701644440

26

Gómez-Suárez A. (2020). “A short history of anti-communist violence in Colombia (1930–2018): rupture with the past or rebranding?” in The palgrave handbook of anti-communist persecutions. eds. GerlachC.SixC. (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

27

González F. (2003a). “Alcances y limitaciones del Frente Nacional como pacto de paz. Un acuerdo basado en la desconfianza mutua” in Tiempos de paz. Acuerdos en Colombia, 1902–1994. ed. CabraE. (Bogotá: Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá).

28

González F. (2003b). ¿Colapso parcial o presencia diferenciada del estado en Colombia? Una mirada desde la historia. Bogotá: Colombia Internacional.

29

Grossman H. (1991). A general equilibrium model of insurrection. Am. Econ. Rev.81, 912–921.

30

Guisao-Álvarez J. (2022). La modernización estatal como necesidad para el futuro: el Frente Nacional, 1958-1974. Hist. Rev. Hist. Reg. Local.14, 232–256. doi: 10.7440/res64.2018.03

31

Gutiérrez-Sanín F. (2012). El déficit civilizatorio de nuestro régimen político. La anomalía colombiana en una perspectiva comparada. Análisis Político.25, 59–82.

32

Gutiérrez-Sanín F. (2014). El orangután con sacoleva: cien años de democracia y represión en Colombia (1910–2010). Bogotá: Debate.

33

Gutiérrez-Sanín F. (2022). Illicit economies and political opportunity. the case of the Colombian paramilitaries (1982−2007). J. Political Power15, 80–100. doi: 10.1080/2158379X.2022.2031110

34

Harris R. I. D. (1995). Using cointegration analysis in econometric modelling. New York: Prentice Hall.

35

Hartlyn J. (1993). La política del régimen de coalición: la experiencia del Frente Nacional en Colombia. Bogotá: Ediciones Uniandes y Tercer Mundo Editores.

36

Hegre H. (2014). Democracy and armed conflict. J. Peace Res.51, 159–172. doi: 10.1177/0022343313512852

37

Hegre H. Ellingsen T. Gates S. Gleditsch N. (2001). Toward a democratic civil peace? democracy, political change, and civil war, 1816-1992. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.95, 33–48. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401000119

38

Hughes B. (2010). Revisiting the liberal logic of intrastate security: the mitigation of political violence for all?Democr. Secur.6, 52–80. doi: 10.1080/17419160903539220

39

Hybel A. R. (2020). “The Challenges of State Creation and Democratization in Colombia and Venezuela” in The challenges of creating democracies in the Americas: The United States, Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Costa Rica, and Guatemala. ed. HybelA. R. (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

40

Iyengar R. Monten J. Hanson M. (2011). Building peace: the impact of aid on the labor market for insurgents, NBER working papers 17297. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

41

Jaramillo J. Franco B. (2005). “Colombia” in Elections in the Americas. ed. NohlenD. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

42

Kramon E. (2016). Where is vote buying effective? Evidence from a list experiment in Kenya. Elect. Stud.44, 397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2016.09.006

43

Kristine E. Hultman L. (2007). One-sided violence against civilians in war: insights from new fatality data. J. Peace Res.44, 233–246. doi: 10.1177/0022343307075124

44

Leal F. Dávila A (2002). La metamorfosis del sistema político colombiano ¿clientelismo de mercado o nueva forma de intermediación? en Degradación o cambio. Bogotá: Editorial Norma.

45

Leal F. Dávila A . (2010). El sistema político del clientelismo. MundoT. In Clientelismo: El sistema político y su expresión regional. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, Colombia.

46

Leech G. (2011). The FARC: the longest insurgency. Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.

47

LeGrand C. (2003). The Colombian crisis in historical perspective. Can. J. Latin American Caribbean Stud.28, 165–209. doi: 10.1080/08263663.2003.10816840

48

Mark G. Cornett L. Wood R. Haschke P. Arnon D. Pisanò A. (2017). The political terror scale 1976–2016.

49

Medina M. (1989). Bases urbanas de la violencia en Colombia. 1945-1950, 1984-1988. Historia Crítica.1, 20–32. doi: 10.7440/histcrit1.1989.02

50

Mişcoiu S. Kakdeu L.-M. (2021). Authoritarian clientelism: the case of the president’s “creatures” in Cameroon. Acta Politica56, 639–657. doi: 10.1057/s41269-020-00188-y

51

Moncada E. (2016). “Parties, Clientelism, and Violence: Exclusionary Political Order in Colombia” in Cities, business, and the politics of urban violence in Latin America. ed. MoncadaE. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 34–54.

52

Moncada E. (2021). Resisting extortion: victims, criminals, and states in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge Universtiy Press.

53

Munshi S. (2022). Clientelism or public goods: dilemma in a ‘divided democracy’. Constit. Polit. Econ.33, 483–506. doi: 10.1007/s10602-022-09361-1

54

Nichter S. (2008). Vote Buying or Turnout Buying? Machine Politics and the Secret Ballot. The. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.102, 19–31. doi: 10.1017/S0003055408080106

55

Palacio M. (2006). Between legitimacy and violence: a history of Colombia, 1875–2002. Durham: Duke University Press.

56

Palacio M. (2012). Violencia pública en Colombia 1958–2010. San Diego: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

57

Pécaut D. (2012). Orden y violencia: Colombia 1930–1953. Bogotá: Ediciones Eafit.

58

Peic G. Reiter D. (2011). Foreign-imposed regime change, state power and civil war onset, 1920-2004. Br. J. Polit. Sci.41, 453–475. doi: 10.1017/S0007123410000426

59

Peñate A. (1999). “El sendero estratégico del ELN: del idealismo guevarista al clientelismo armado” in Reconocer la guerra para construir la paz. eds. LlorenteV.DeasM. (Barcelona: Editorial Norma).

60

Przeworski A. (2000). Democracy and development: political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950–1990 (Cambridge studies in the theory of democracy). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

61

Ripsman N. (2007). Peacemaking and democratic peace theory: public opinion as an obstacle to peace in post-conflict situations. Democr. Secur.3, 89–113. doi: 10.1080/17419160701199300

62

Robinson J. A. Verdier T. (2013). The political economy of clientelism. Scand. J. Econ.115, 260–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9442.2013.12010.x

63

Romero M. (2003). Paramilitares y Autodefensas 1982–2003. Gulshan: IEPRI.

64

Saiya N. (2021). Who attacks America? Islamist attacks on the American Homeland. Perspectiv. Terr.15, 14–28.

65

Sambanis N. (2001). Do ethnic and nonethnic civil wars have the same causes? a theoretical and empirical inquiry (part 1). J. Confl. Resolut.45, 259–282. doi: 10.1177/0022002701045003001

66

Steele A. Schubiger L. (2018). Democracy and civil war: The case of Colombia. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci.35, 587–600. doi: 10.1177/0738894218787780

67

Stokes S. (2021). Clientelism and development: is there a poverty trap?Shibuya: United Nations University.

68

Stokes S. Dunning T. Nazareno M. Brusco V. (2013). brokers, voters and clientelism. The puzzle of distributive politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

69

Suhrke A. (2007). Reconstruction as modernisation: The ‘Post-Conflict’ project in Afghanistan. Third World Q.28, 1291–1308. doi: 10.1080/01436590701547053

70

Vahhabi M. (2020). Political Economy of Conflict and Institutions. Foreword. Revue d’économie Politique.130, 847–854.

71

Vreeland J. (2008). The effect of political regime on civil war: unpacking anocracy. J. Confl. Resolut.52, 401–425. doi: 10.1177/0022002708315594

Appendix

When there is a significant concentration of political power, implying that only a few political parties hold the control over the access to power and bureaucracy, the degree of democratization in the political regime tends to be low. This situation is mainly attributed to the politicians who rely on narrow, highly exclusionary, and clientelistic bases of representation, heavily dependent on clientelism. As shown in Figure 2, a higher Political Power Concentration (PPC) index corresponds to a lower level of democratization in the political regime. Our study, using the Johansen cointegration test, indicates a long-term equilibrium relationship between the series considered (Table 3).

The presence of cointegration (a shared stochastic trend) between the Democratization index and the concentration of political power suggests that there is a notable negative long-term correlation between the two variables. Thus, in Colombia’s hybrid regime, an elevation in the concentration of political power within the legislative branch has corresponded to a reduction in the level of democratization within the political system.