- School of Management, IT and Governance, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

The local government in South Africa faces a dire scenario as it relentlessly fails to execute its legally mandated responsibilities of rendering essential goods and services. Despite various legal frameworks (The Municipal Systems Act 2000; The Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA) 2003) and government interventions (The Batho Pele Principles 1997) to address the bureaucratic limitations, local government continues to transgress, resulting in many local municipalities receiving adverse audit outcomes from the Auditor General every year. Prior research on local government in South Africa has not extensively investigated the effects of continuous learning on mitigating bureaucratic limitations and promoting efficiency and effectiveness in municipal service delivery. This paper examines the role of learning organizations, guided by Pete Senge’s Model of Learning Organizations, in mitigating bureaucratic limitations within South African local governments. Using a qualitative case study approach, the research explores how continuous learning platforms can contribute to overcoming these limitations and enhancing municipal service delivery. A purposive sampling technique was employed to select 50 participants from 10 municipalities across six South African provinces, ensuring representation from various managerial levels within local governments. The study’s key findings reveal that if properly implemented, continuous learning frameworks can address critical issues such as administrative inefficiency and resistance to innovation, which are deeply embedded in bureaucratic structures. The findings also highlight that change management strategies, grounded in collaborative learning and shared vision, are essential for fostering an environment conducive to organizational transformation. However, the study identified significant challenges, including political interference, staff turnover, and cultural resistance, which limit the effectiveness of learning organizations. Based on these findings, the study recommends targeted interventions that promote leadership development, skills enhancement, and policy reform to create a sustainable culture of continuous learning in local government.

1 Introduction

Local and central governments in many African countries are positioned to deliver basic goods and services.1 In most cases, their function is enshrined in legislation, making them relevant in advancing public service delivery. In South Africa, Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (1998) is one of the most strategic frameworks to guide local government service delivery. Additionally, Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996) and Republic of South Africa (2000) mandate local governments to provide essential services like water, electricity, and sanitation. Fundamental laws such as Republic of South Africa (1997) and Republic of South Africa (2006) further define municipalities’ obligations to ensure access to these services. However, just like any other piece of legislation, implementing the enabling legislation has become complex in local government owing to various bureaucratic limitations such as maladministration, which has resulted in some local municipalities failing to render public goods and services and ultimately being placed in the high-risk category or under provincial administration. The dire scenario experienced in local government has seen local municipalities failing to execute their legally mandated responsibilities as transgressions are on the rise, leading to them receiving adverse audit outcomes from the Auditor General every year (Shava, 2024).

Contemporary literature on public service delivery reveals that transforming local government can be done by promoting continuous learning organizations where creativity and innovation are embraced (Masiya et al., 2021). While the fear of change is real in transforming local government, this research envisaged a gap in previous studies where the causes and effects of poor municipal service delivery are viewed in line with political and administrative limitations. Little has been done to examine the efficacy of implementing continuous learning, although it can continually transform municipal governance through the skilling and reskilling of municipal officials. We argue in this study that although legislation and codes of conduct exist to guide the work of municipal officials, more needs to be done in the form of continuous learning to ensure that municipal structures and structures are reformed to become responsive to the dynamic trends in the public service delivery landscape. The paper answers the following questions: What are learning organizations and in what way can they assist in curbing bureaucratic Limitations in Local Government? What factors trigger bureaucratic limitations, and how can they be addressed to promote continuous learning in local government?

After the introduction, the Pete Senge Model of Learning Organization is discussed, followed by a review of relevant literature. The paper then discusses the methodological procedure followed to collect the data. The fifth section encompasses the presentation of findings. Thereafter, a discussion of findings and then a conclusion and recommendations.

2 Theoretical underpinnings: Pete Senge model

This paper integrates Pete Senge’s model of learning organizations with a particular focus on addressing bureaucratic limitations in the local government setting in South Africa. Senge’s framework, which accentuates the systematic cultivation of continuous learning within organizations, is relevant to the challenges confronting local governments that struggle with service delivery, inefficiency, and regulatory compliance (Reese, 2020). This current study provides a poignant context for applying Senge’s (1990) principles. It emphasizes the need for continuous learning to circumvent the entrenched bureaucratic obstacles and improve public service delivery (Reese, 2020).

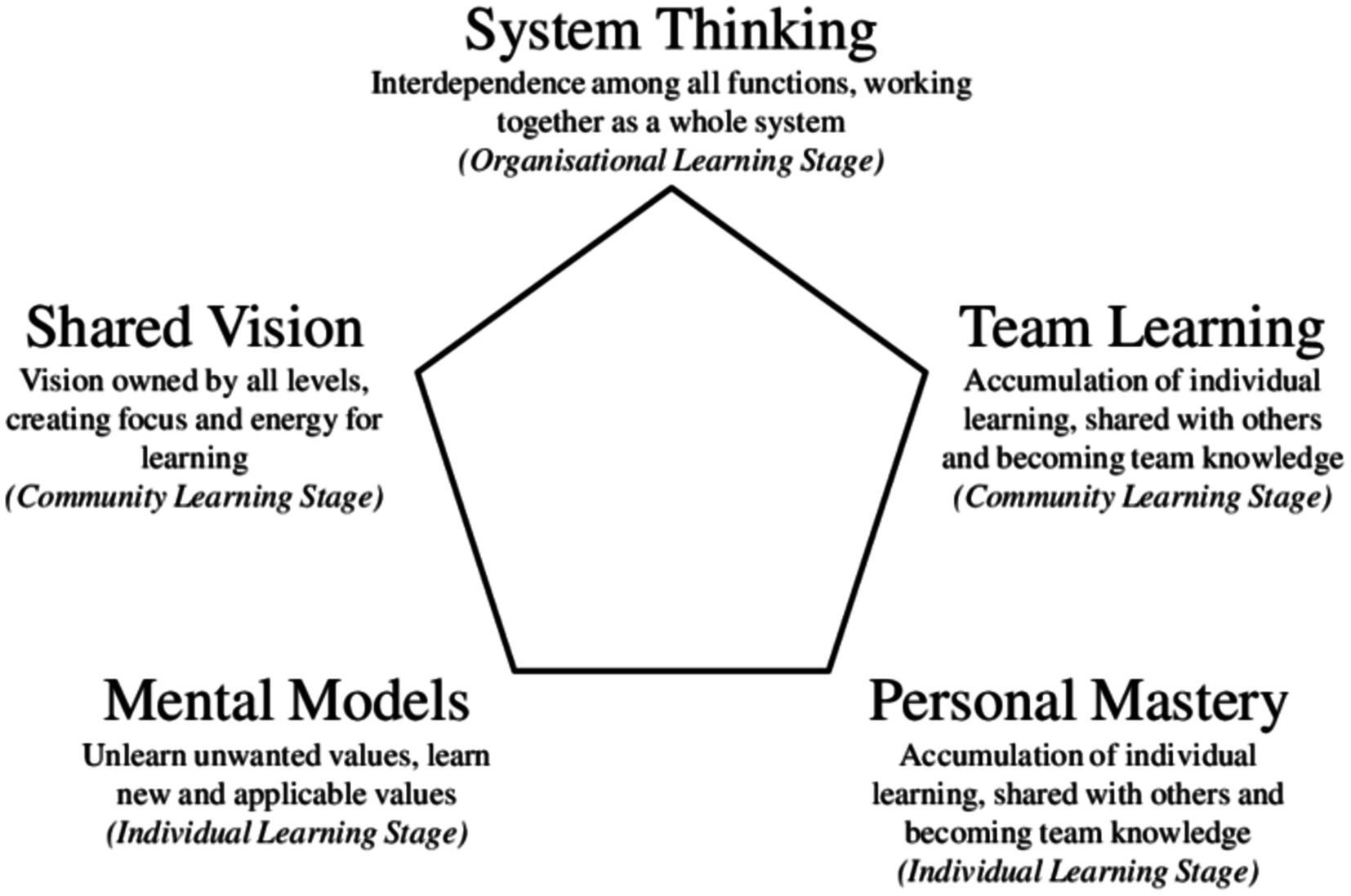

Senge’s framework has five fundamental cornerstones. Systems thinking is the first and stands as the foundational element. System thinking accentuates the ability to perceive and understand the interconnectedness of components within the whole system (Senge, 1990; Springmier et al., 2024). This notion is crucial for local government because it promotes a comprehensive understanding of bureaucratic inefficiencies and their systems roots, thereby allowing for more effective resolutions. After the principle of systems thinking comes the concept of personal mastery. This aspect extends the framework by indicating the importance of individual commitment to lifelong learning. This personal growth is vital for public officials. It enables them to adapt and innovate within their roles continually. Therefore, it enhances the responsiveness and effectiveness of local governance.

Moreover, the model also indicates the importance of mental models- deeply ingrained assumptions that shape how individuals perceive and react to their environment (Senge, 1990; Springmier et al., 2024). Shifting and developing these mental models are critical processes for local government officials. They encourage adaptability and openness to new, innovative solutions that can improve service delivery. Additionally, the concept of shared vision within organizations promotes a unified commitment to a common purpose. This allows individuals to align their motivations with broader organizational goals. This approach is essential for cohesive and effective service delivery.

Finally, the framework pays attention to team learning. This element encourages collaborative problem-solving and innovation. These are essential for organizations’ transformation. In local government, siloed functions hinder effective service delivery (Senge, 1990; Springmier et al., 2024). Put together, these concepts form a cohesive theoretical framework that underpins the transformative potential of integrating continuous learning into the fabric of local government operations. To systematically address and mitigate bureaucratic challenges. The tenets of the model are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Pete Senge model of learning organizations source: (Adapted from Senge, 1990).

Previous research has shown that these Senge (1990) principles can affect the functioning of public sector organizations. For instance, Olejarski et al. (2019) discussed integrating learning organization principles in public settings. They stressed the importance of cultural and political adaptations in fostering the transformation of local government. In a different study, Antonacopoulou et al. (2019) highlighted the transformative potential of learning at all organizational levels. Finally, Pallett (2018) and Al-Karaeen and Al-Ashaab (2021) further explore the application of organizational learning to enhance public participation and digital transformation.

Senge’s model is a comprehensive framework for understanding how continuous learning processes can be embedded within local government operations to overcome bureaucratic obstacles and enhance service delivery. This study adapts Senge’s model to address the unique challenges local governments face in South Africa. It focuses on developing competencies that align with dynamic public service demands. The primary assumption underpinning Senge’s model in this context is that bureaucratic inefficiencies in local government are not merely the result of flawed processes but also of a culture that does not prioritize learning and adaptation. The model posits that systemic change is achievable through continuous learning and aligning individual and organizational objectives. The theoretical framework aligns with the study’s aim to explore practical strategies for implementing learning practices within local governments to address bureaucratic limitations. This study provides actionable insights into fostering environments conducive to continuous improvement and innovation in public service.

3 Literature review

3.1 Conceptualizing learning organizations in the public sector

The development of the learning organization concept in the public sector has its pedigree in the works of scholars like Peter Senge in the 1990s. This scholar popularized the idea in business contexts. With time, learning organizations were adapted to public administration’s unique needs and challenges. In the public sector, they were applied to incorporate aspects of public accountability, transparency, and stakeholder engagement (Elliott, 2020).

The concept of learning organizations has gone through various transmutations. The terms are often interchangeable with organizational learning (Elliott, 2020; Thornhill and Van Dijk, 2003). However, it is safe to say that the two, while closely related, are not synonymous. To illustrate, learning organizations are specific organizations that embody learning principles at all levels. This means that the organizations that embody these principles are often characterized by a deliberate structure and culture designed to enhance and promote continuous learning and adaptability (Senge, 1990). On the other hand, organizational learning refers to the broader concept that describes how a specific organization acquires, develops, and transfers knowledge. This knowledge is intended to improve the organization’s performance and allow it to adapt to its environment (Argyris and Schön, 1997).

Stewart (2001) argues that scholars must consider what “learning” implies. For Thornhill and van Dijk (2003), learning is not an objective, measurable concept that can be operationalized scientifically. More so, Thornhill and van Dijk (2003) identified two approaches to learning that are useful in understating the term “learning”: these are “behavioral learning” and “cognitive learning.” Behavioral learning refers to coping with the available organizational routine or rules. It also includes dealing with the change occurring in individuals and the changes in structures, goals, and aspirations. On the other hand, cognitive learning involves issues related to generative learning, focusing on the thinking process and emotional responses and based on qualitative research. Thornhill and Van Dijk (2003) argued that the learning organization has much to do with behavioral learning. It concerns a composite process that includes skills such as mental mapping, intuition, imagination, and problem-solving (Thornhill and Van Dijk, 2003). Therefore, if the public sector intends to create a learning organization. It must place its attention to the development of a learning culture. In that space, a learning organization can be developed (Thornhill and Van Dijk, 2003).

The concept of learning organizations in the public sector involves multiple definitions that reflect different aspects of how organizations approach learning and adaptation. The available definitions often emphasize the systemic, continuous, and transformative aspects of organizational learning. Still, they vary in focus and implications, depending on the theoretical orientation and the specific public sector context being addressed. Olejarski et al. (2019) define Learning Organizations as those that emphasize an integrative culture that fosters learning and adapts to changes in the external environment to improve performance and governance. This definition highlights the importance of cultural factors and the external adaptability of public sector organizations. Antonacopoulou et al. (2019) describe Learning Organizations as entities that continuously transform themselves through mastering the art and science of learning at all levels. Here, the focus is on the comprehensive integration of learning processes within the organization’s operations and the personal development of its members. Elliott (2020) offers a slightly different angle by focusing on the procedural aspects of learning in the public sector: Learning Organizations systematically integrate feedback from policy outcomes to recalibrate strategies and practices. This definition is particularly relevant to public administration, where policy feedback is crucial to learning.

These definitions show the significance of continuous learning and adaptation. They possess some slight contradictions. For example, some definitions emphasize the cultural aspects of learning organizations, suggesting that transformation is primarily driven by organizational cultural change (Olejarski et al., 2019). In contrast, others stress the systematic incorporation of learning processes into the organizational structure and routines (Elliott, 2020). Antonacopoulou et al. (2019) highlight the importance of individual learning in the organizational learning process. Elliott (2020) focuses more on organizational-level outcomes and feedback mechanisms without explicitly addressing individual learning dynamics.

3.2 The role of learning organizations in overcoming bureaucratic constraints in local government

Empirical studies provide valuable insights into how learning organizations can help alleviate bureaucratic constraints within local governments. For instance, Ahmad (2021) explored how the Makassar City Government implemented systemic thinking and continuous improvement strategies to make its bureaucracy more responsive and flexible. Similar to how social workers “play the system” to navigate bureaucratic limitations, Ahmad’s (2021) findings show that local officials creatively adapt learning principles to function effectively within existing bureaucratic structures. Even though these principles are integrated into governmental frameworks, they still allow for a degree of discretion, enabling quicker and more efficient responses to public needs.

Further research by Fushimi (2022) and Leeuw (2020) offers a broader perspective on the role of learning organizations in governance reform. While traditional organizational learning models provide creative solutions to administrative problems, Fushimi (2022) argues that these models often need to be expanded in scope for use in public agencies. In contrast, Leeuw (2020) suggests that governments can become more proactive and adaptive by moving beyond conventional bureaucratic practices and adopting learning organization techniques, which promote continuous adaptation and innovation.

These findings align with broader discussions on discretion in public service, such as those explored by Maynard-Moody et al. (2003). Their work introduces the concept of the ‘citizen agent,’ contrasting public workers who strictly adhere to procedural rules (state agents) with those who see themselves as serving the community’s best interests. The latter use their judgment and local expertise to meet citizens’ demands. Similarly, Durose (2011) describes local government officials as “civic entrepreneurs” who use their understanding of community dynamics and policy tools to address complex problems, such as social exclusion, demonstrating the creative application of learning principles in public service.

These studies highlight a shift in how learning organizations within local governments can bridge the gap between rigid bureaucratic systems and the evolving needs of citizens. By incorporating learning organization principles, local governments foster innovative practices and cultivate a culture where officials can navigate bureaucratic obstacles, improving overall public service delivery. This transformation ultimately empowers officials to act as intermediaries between the state and the public, ensuring that bureaucratic processes remain adaptable and responsive to societal changes.

3.3 Factors that trigger bureaucratic limitations and how can they be addressed to promote continuous learning in local government

Empirical research captures the factors influencing bureaucratic limitations and highlights how continuous learning can be promoted within local government frameworks (Masiya et al., 2021; Moji et al., 2022). Previous studies suggest that various factors trigger bureaucratic limitations in local government. These include inefficient and convoluted procedures, resource constraints, lack of incentives, political and social conflicts, corruption, and challenges in governance, such as role confusion, lack of transparency, and external pressures. An example is Ledger (2020) work on non-compliance in South African local government. By delving into the ‘logic of appropriateness,’ the author shows that non-compliance frequently results from a gap between mandated behaviors and what is considered suitable in particular local settings. This discrepancy highlights how long-standing cultural norms can impede the effectiveness of official processes, leading to bureaucratic inefficiency.

Similarly, Masiya et al. (2021) investigated the factors influencing the performance of South African municipal authorities. They found that problems stemming from a lack of expertise, inadequate funding, and political meddling are the main barriers. All these things show how complex bureaucratic problems are and how they hinder the efficiency and responsiveness of municipal governments. The need for robust accountability systems to improve governance is further highlighted by this study, which concurs with the conclusions of Moji et al. (2022), who examine the obstacles to efficient oversight procedures in South African municipalities.

Setyasih (2023) research on the potential of learning organizations in local governments calls for a decrease in bureaucratic pathology to promote more efficient and flexible bureaucratic structures. This method proposes that a more responsive and learning-oriented government may be achieved by eliminating long-standing bureaucratic inefficiencies. Looking at low-carbon projects globally, Doren et al. (2020) offer a convincing example from Copenhagen to show how local governments might learn and scale them up. As this case study shows, learning organizations are great at encouraging creative approaches to governance, and local governments have much room to grow and change when faced with new problems.

The literature shows how local governments face a tricky balancing act between rigid bureaucracy and the adaptability of learning organizations. The studies suggest that bureaucratic structures are resistant to change. However, by implementing learning principles like systemic thinking and continuous improvement, these institutions can gradually transform and eventually become more responsive to the needs of the communities they serve. Public service delivery that is both efficient and equitable may be achieved through the reforms proposed in this body of work, which also details the obstacles to good local government and provides a road map for improvement.

4 Methods and materials

Thus, the study examined the efficacy of implementing continuous learning initiatives in local government to overcome bureaucratic limitations. The generation of qualitative data was perceived to help obtain a coherent presentation of the effectiveness of constant learning in curbing bureaucratic limitations in local government in South Africa. The study used a case study design to explore selected South African municipalities, providing an in-depth examination of governance challenges. Focus group discussions were employed to gather detailed insights from municipal managers and staff about their experiences with continuous learning. While the case study provided a broader contextual framework for understanding governance challenges, the focus groups offered more specific insights into the attitudes and practices of individuals working within these systems.

4.1 Participants

The study drew from 50 participants across six provinces for the online focus group in-depth interviews. The participants were distributed as follows: twenty-four from KwaZulu-Natal, Four from Limpopo, one from Free State, 18 from Gauteng, eight from the Eastern Cape and 77 from Mpumalanga. A purposive sampling technique was used for the interview to draw participants from the various municipalities. The participants for this study included municipal managers, senior managers, general managers, community development managers and services managers. Four participants were interviewed from KwaZulu-Natal province. This included four from uMzimkulu local municipalities, uMhlathuzi local municipalities, and six participants from Msunduzi local municipality. The participants from Eastern Cape Province included one participant from Dr. Kenneth Kaunda’s local municipality, one from the Nelson Mandela metro, and one from the Ntabankulu local municipality. The Mpumalanga sample included four participants from Ehlanzeni, one from Bushbuckridge, and one from Matlosane. Regarding Limpopo province, one participant from Mopane municipality participated in the study.

4.2 Data collection procedure

After receiving permission from the University of KwaZulu-Natal Research Ethics Committee to conduct the study, the researchers invited the participants to participate. Using a purposive sampling technique, various participants were sent an email soliciting their participation in the study. The participants were drawn from the six South African provinces and 10 municipalities. The participants were senior managers and middle-level management in selected municipalities who had the relevant knowledge and were keen to know or were interested in bureaucratic challenges in municipalities and how organizational learning is used to circumvent such challenges. Focus group sessions were held on the Microsoft Team. All the sessions were recorded and transcribed simultaneously on Teams. The entire data collection process took a month to complete. All the participating municipalities granted the gatekeeper’s permission to interview the participants. Secondary data was used to supplement the discussion of qualitative findings.

4.3 Data analysis

A traditional Braun and Clarke (2006) qualitative analysis was employed to analyze topics discussed in focus groups. A rigorous coding technique was used to identify bureaucratic challenges and the efficacy of learning organizations in curbing bureaucratic impediments. Participants’ perspectives were conveyed by sorting, examining, and modifying themes following coding. The patterns and linkages among the themes were analyzed to understand better the qualitative leadership challenges and their impact on staff turnover and service delivery in South African local government.

5 Results

This section presents the data from the focus group interviews. The results are presented thematically, following the objective of this study.

5.1 Efficacy of learning organizations in municipal service delivery

The theme of learning organization in municipal service delivery explores how adopting learning organization principles within local government can address bureaucratic inefficiencies and enhance the effectiveness of service delivery. The participants shared various perspectives that reflect the potential and challenges associated with implementing continuous learning frameworks in local governments. The participant’s responses show the transformative potential of learning organizations in municipalities.

A participant stressed the positive role of continuous learning in the municipal planning strategy. They stressed its role in making the planning process more adaptive and aligned with community needs. They said,

Adopting learning organization principles like team vision in our municipality has significantly improved our strategic planning processes. We’ve moved from a static approach to a more dynamic and responsive planning cycle, which aligns with the actual needs of our community. (CoJ 8).

Another participant from KZN highlighted the cultural barriers in municipal environments. They suggested that the efficacy of learning organizations is often hindered by deep-seated resistance to change within bureaucratic systems.

While the concept is promising, the real challenge lies in overcoming the existing bureaucratic culture that resists change. Without a fundamental shift in mindset, the full benefits of learning organizations cannot be realized. (MSDZ 2).

Additionally, the direct benefits of collaborative learning approaches in municipalities were prominently highlighted among all participants. Participants indicated that collaborative learning practices enhance team project handling and improve service delivery. A participant from Mpumalanga stressed that,

We’ve seen a noticeable improvement in how our teams handle complex projects. Learning organization practices have encouraged more collaborative problem-solving, which has directly impacted our service delivery outcomes positively. (Mpumalanga 9).

Moreover, the role of learning organizations in breaking down operational silos within municipalities dominated the responses. Almost all participants from the 10 provinces stressed that learning organizational principles such as shared vision, team building, and collaboration among employees has helped break the barriers to cooperation. As a result, breaking siloed operations that are rampant in most municipalities. One participant from the Eastern Cape province stressed that,

The introduction of continuous learning platforms has facilitated better knowledge sharing across departments, which was a major issue previously due to siloed operations (Eastern Cape 2).

The participant responses above reveal a massive shift toward more responsive and dynamic governance structures enabled by adopting learning organization principles. This shift aligns municipal strategies with community needs and enhances a culture of collaborative problem-solving that is essential for dismantling the entrenched operational silos in local government. However, the positive changes ushered by these positive changes are contrasted sharply against the backdrop of cultural resistance to bureaucratic systems. Cultural resistance is a potential barrier to fully realizing the benefits of learning organizations.

5.2 Administrative and political factors

The theme of administrative and political factors pays attention to the administrative and political factors that influence the functioning of municipal governments. It captures participants’ responses on how these elements either facilitate or hinder the implementation of learning organizations’ principles in various municipalities across South Africa. In response to the questions of what factors hinder the implementation of learning organization principles in local government, participants from various municipalities paint a picture of the complex interplay between administrative protocols, political influence, and the practical challenges of implementing learning organizations in municipalities. The participants also indicated the need for reforms that reduce bureaucratic challenges and enhance administrative consistency. Below are some perspectives from the participants.

Most participants discussed the impact of political interference and administrative bureaucracy. They suggested that political agendas complicate or stifle the effective adoption of learning principles in municipal governance. For instance, one participant from Gauteng discussed the effects of political interference saying,

The administrative red tape and political interference are the biggest hurdles to adopting new learning frameworks in our municipality. Political agendas often overshadow objective decision-making which directly affects our operational efficiency. (Gauteng 1).

Another group of participants discussed how they struggle with the lack of consistency in administrative leadership. They said its absence disrupts the continuity necessary for effective learning and adaption in local government. To illustrate, a participant from the Western Cape stated that,

We struggle with frequent policy changes and a lack of consistency in administrative leadership which makes it difficult to maintain a steady direction for implementing continuous learning practices. (Western Cape 1).

Most of the participants discussed the issue of resistance to change and the implementation of learning practices in local government. The participants stressed that the resistance from political leaders toward organizational changes that may alter existing power structures is a massive barrier to innovative practitioners in local government. Ano participant from the Eastern Cape stressed that,

Our attempts to implement learning organizations are often met with skepticism by elected officials who are cautious of initiatives that may disrupt the existing power dynamics. (Eastern Cape 1).

Additionally, some participants also emphasized how bureaucratic processes can impede innovation by slowing the implementation of new ideas and diminishing the impact of initiatives to improve service delivery. To illustrate, a participant from Limpopo said that,

Administrative bureaucracy stifles innovation. We have the ideas and the momentum, but the layers of approval and rigid protocols consume time and dilute the urgency of our initiatives. (Limpopo 1).

Finally, some of the participants shed light on the issue of political patronage. These participants revealed how political patronage leads to resource misallocation and appointments that may not align with the principles of meritocracy and efficiency required by learning organizations. For example, a participant from Mpumalanga stated that,

Political patronage affects how resources are allocated and who gets to lead projects, often not based on merit but on loyalty, which undermines the principles of a learning organization. (Mpumalanga 1).

The responses from the various municipal participants vividly illustrate the challenges that administrative and political factors pose to implementing learning organization principles in local government. The recurrent themes of political interference, administrative inconsistency, resistance to change, bureaucratic inertia, and political patronage collectively create a complex barrier to learning organizations’ adoption and effective operation. These factors not only impede the introduction of innovative and adaptive practices. Instead, they fundamentally undermine the capacity for continuous improvement and responsive governance central to the learning organization model.

5.3 Unreformed mindsets and fear of learning

This section discusses the challenges of unreformed mindsets and fear of learning within local government. The theme addresses how entrenched attitudes and resistance to new methods of operation stifle innovation and the successful municipal adoption of learning organization principles. Participants from different municipalities expressed the impact of unreformed mindset and fear of learning. The participants revealed the multifaceted nature of resistance to change—from generational divides and cultural inertia to fears of failure and leadership dynamics—and underlined the need for comprehensive strategies that address these psychological and cultural barriers to foster true organizational learning.

Most of the participants expressed concern over the generational divide within the local government structures. The participants expressed that the older employees normally feel threatened by the new approaches to operating local government. They said, learning new organizational approaches challenge their traditional ways of operations. They are resistant to new principles. A participant from Northen Cape captures the essence of this situation. The participant said,

There’s significant resistance to change among the older generation of employees who prefer traditional methods over new, untested approaches. This resistance is deeply rooted in a fear of the unknown, which often hampers our progress toward becoming a learning organization. (Northern Cape 6).

Additionally, the participants also discussed the challenge of cultural transformation in organizations where historical practices are deeply ingrained and viewed as standards. A participant from Gauteng provides a context stating that,

The main barrier we face is the mindset that ‘this is how we have always done it.’ Overcoming this mindset requires not just training but a fundamental shift in our organizational culture.” (Free State 3).

Moreover, some participants describe how a fear of failure and a punitive approach to mistakes create an environment that discourages experimentation and learning. A participant from Gauteng stated that,

Fear of failure and the repercussions that follow are a major concern. Our staff are hesitant to try new things because they are worried about the consequences of failure, which stifles creativity and learning.” (Gauteng 5).

The challenge of skepticism toward new initiatives in local government featured prominently among the participants from the Eastern Cape and Gauteng. This group of participants stressed that there is a serious skepticism toward new initiatives. The municipal leadership perceive them as fleeting and not meriting significant investment in learning and adaptation. One participant from the Eastern Cape stated that,

In our efforts to introduce continuous learning, we often encounter skepticism. There’s a prevailing belief that these new initiatives are just temporary fixes and not worth the effort of learning. (Eastern Cape 2).

Finally, another participant from Limpopo recalled how leadership dynamics can contribute to fear of learning. The participant stressed that leaders potentially view challenges that encourage learning and empowerment as threats to their authority. The participant said,

Our leadership is often more concerned with maintaining their authority than fostering an environment of learning and growth, which creates resistance to any form of change that might diminish their control.” (Gauteng 2).

The responses above reveal the pervasive impact of an unreformed mindset and fear of learning within local government structures across municipalities in South Africa. These tendencies hinder the adoption of and implementation of learning organizations’ principles. Additionally, the participant’s insights reveal a broad spectrum of resistance rooted in generational divides, entrenched cultural norms, fear of failure and leadership dynamics. The resistance impedes the introduction of innovative practices and affects municipal governance’s overall agility and effectiveness. Moreover, the skepticism toward new initiatives and the leadership’s focus on maintaining control rather than promoting growth and learning create substantial barriers to fostering environments that are conducive to improvement.

5.4 Limited skills in establishing continuous learning platforms

The theme of limited skills in establishing continuous learning platforms focuses on the various challenges that local governments face due to the lack of skills necessary for developing and maintaining continuous learning platforms. These platforms are important for fostering an environment of ongoing development and innovation within municipal structures. However, to establish these platforms, a set of skills is required but lacking from local government personnel. Participants from various municipalities discuss the skills gap that they perceive to impede the creation and effective use of the learning platforms.

Participants indicated a huge technological skills gap that prevents the establishment of sophisticated learning platforms within local government. For instance, a participant from KZN discusses the challenges related to the technological skills gap saying,

We struggle with the technical expertise required to set up and manage effective learning platforms. Our IT staff lacks the training in newer technologies that would allow us to integrate these systems seamlessly into our daily operations.” (KwaZulu-Natal 1).

A group of participants from Gauteng and Eastern Cape stressed the lack of capability within the HR departments to create training programs promoting continuous learning and adaptability among the various municipal employees. For instance, a participant from Gauteng stated that,

There is a real deficit in training and development skills among our HR team, which makes it difficult to design and implement effective continuous learning programs for our staff. (Eastern Cape 7).

Additionally, a participant from Limpopo described the mismatch between existing training content and the present-day requirements of municipal operations. They stress the need for updated educational materials and skilled trainers. They said,

Most of our training modules are outdated, and there’s a scarcity of trainers who can develop modern content that resonates with our current needs for digital transformation and continuous improvement.” (Limpopo 1).

Moreover, participants from Eastern Cape and Western Cape identified a gap in the leadership development in their municipalities. They stressed gaps in the skills related to managing change and encouraging a culture of learning within municipal environments.

Our leadership training does not effectively prepare our managers for the challenges of fostering a learning environment. They need skills not just in management but in leading change and innovation. (Eastern Cape 3).

Finally, participants from Mpumalanga discussed the operational challenges following the introduction of learning platforms. They indicated that there is a need for adequate training to ensure these tools are used effectively and integrated into daily work processes. To illustrate, a participant from Mpumalanga stressed that,

Even when we introduce learning platforms, there’s a significant drop-off in usage because the staff aren’t trained on how to integrate these tools into their work routines effectively. (Mpumalanga 13).

The participants collectively illustrate the skills shortage in local government. This shortage impedes the developing and using continuous learning platforms in the sector. The lack of technical expertise, outdated training programs, insufficient leadership skills, and general resistance to new technologies are significant barriers that must be addressed to enhance the capacity for continuous learning and innovation in municipal governance.

5.5 High staff turnover

The theme on high staff turnover pays attention to the issue of high staff turnover in local government and its impact on the continuity and effectiveness of service delivery and institutional knowledge. Previous research shows that high turnover rates can severely disrupt the implementation of continuous learning platforms. It also affects the overall development of learning organizations within municipalities. Participants from various South African municipalities shared their experiences regarding how high turnover complicates efforts to sustain improvements and integrate new practices effectively.

One of the recurring issues that emerged across all provinces was the challenge of retaining skilled employees in the public sector. Most participants stressed that the public sector suffered greatly from the brain drain of talent. Most skilled personnel are moving to the private sector opportunities. To illustrate, a participant from the Free State explained the situation by saying,

We constantly lose talented staff to the private sector, which affects our ability to maintain consistency in our projects and initiatives. Just as someone becomes proficient, they leave. (Free State 3).

Additionally, another group of participants paid special attention to the financial and cultural costs associated with high turnover. They described how these hinder the development of a stable and mature organizational learning environment.

The cycle of hiring and training is never-ending. High turnover not only increases operational costs but also prevents us from developing a mature learning culture.” (Gauteng 7).

Furthermore, another participant from the Eastern Cape illustrated the operational setbacks caused by high turnover. New hires need extensive training, thus diverting resources from other strategic areas. The participant said,

Each time we have a wave of resignations, it sets back our progress. New staff need to start from scratch, and it drains resources meant for advancing our strategic objectives. (Eastern Cape 2).

Several participants from the KZN province emphasized how turnover affects those involved in innovative and training roles. As a result, stalling overall organizational transformation efforts. For instance, a participant from Msunduzi.

Frequent personnel changes disrupt our momentum. When employees who are crucial to innovation and training programs leave, it pauses our entire transformation effort.” (KwaZulu-Natal 8).

Finally, some participants from Limpopo focused on the impact of turnover at the management level. They discussed how it complicates the implementation of sustained changes and long-term planning. They also express concerns about the loss of young talent, which impacts immediate service delivery and future leadership development within the municipality.

The high turnover at the management level creates a lack of leadership continuity, making it difficult to sustain any long-term change initiatives.” (Western Cape 3).

We’re seeing a trend where our most capable young professionals are quickly moving on for better prospects. This not only affects our service delivery but also our future leadership pipeline.” (Limpopo 2).

These responses depict the effects of high staff turnover on the stability, cultural development, and progression of learning organizations within local government. The loss of talent, particularly those trained to usher in new methodologies, directly impacts the continuity of service delivery and the growth of institutional knowledge.

6 Discussion

The research examined the efficacy of implementing continuous learning initiatives in local governments to mitigate bureaucratic limitations. It revealed insights into the transformation potential and the obstacles faced by municipalities. The findings from the study demonstrated an interplay between learning organization principles and municipal service delivery effectiveness. It also emphasized the challenges posed by administrative and political factors, unreformed mindsets, limited skills, and high staff turnover.

6.1 The role of continuous learning in addressing bureaucratic inefficiencies

The findings confirm that continuous learning has the potential to significantly enhance municipal service delivery by fostering more adaptive and responsive governance structures. This aligns with previous studies, such as those by Ahmad (2021) and Masiya et al. (2021), highlighting the importance of learning organizations in transforming bureaucratic institutions into more dynamic and efficient entities. In particular, the shift from static to dynamic planning processes, as reported by several participants, echoes Ahmad (2021) argument that learning organizations can facilitate greater organizational agility in the public sector. However, the efficacy of continuous learning in South African municipalities appears constrained by deeply ingrained institutional rigidities. As previous research by Thornhill and van Dijk (2003) suggested, there must be a concerted effort to address behavioral and cultural learning to be effective in public sector organizations. Our findings support this, revealing that continuous learning initiatives may struggle to take root without a fundamental cultural shift. This adds a layer of complexity to Senge’s (1990) learning organization framework, which presupposes an openness to change that is not always present in public institutions.

6.2 Political and administrative barriers to learning organizations

A key finding of this study is the pervasive role that political interference plays in undermining the implementation of continuous learning initiatives. This is consistent with the work of Fushimi (2022) and Reddy (2018), who argued that political agendas frequently complicate or stifle public sector reforms. Our results show that political actors often influence administrative decisions, leading to a conflict of interests that hinders the objective application of learning frameworks. This adds to the growing body of literature suggesting that in politically charged environments, the success of learning organizations is heavily contingent on reducing political patronage and strengthening administrative autonomy (Olejarski et al., 2019). Moreover, as highlighted by participants, the lack of consistency in administrative leadership further complicates the sustainability of continuous learning platforms. Leadership turnover disrupts the continuity required for effective learning and adaptation, echoing findings by Reddy and Govender (2018), who emphasized the need for stable administrative leadership in driving public sector reform.

6.3 Cultural resistance and the fear of change

Cultural resistance within municipal structures poses another substantial barrier to implementing learning organizations. As participants noted, there is a deep-seated skepticism toward new initiatives, particularly among senior officials. This stems from a fear of losing control or facing negative consequences if innovative approaches fail. This mirrors the findings by Pasieczny and Rosiak (2023), who identified similar resistance to change in European public administration contexts. The fear of change can be traced to what Senge (1990) called “mental models”—deeply ingrained assumptions that shape how individuals and organizations perceive their environment. In the case of South African municipalities, these mental models are often rigid, favoring traditional, hierarchical governance structures over adaptive, collaborative ones.

6.4 Limited skills and resources for learning platforms

A critical barrier to the successful adoption of continuous learning platforms in local government is the skills gap that persists across municipal departments. Participants from several provinces pointed to the lack of technical expertise, particularly in areas related to digital transformation and the establishment of continuous learning platforms. This aligns with the findings of Moloi et al. (2023), who emphasized that inadequate technological infrastructure and skills deficits hinder public sector innovation in developing countries. The challenge is not merely technological; leadership gaps were also highlighted, with participants noting that many municipal managers lack the skills to foster a learning environment. This issue is compounded by outdated training modules that fail to meet the current demands of municipal operations. To overcome these challenges, municipalities must invest in up-to-date, context-specific training programs that enhance technical skills and equip leaders with the competencies needed to drive a learning culture.

6.5 Impact of high staff turnover on learning organizations

High staff turnover emerged as a significant obstacle to sustaining continuous learning in municipalities. The frequent loss of skilled employees to the private sector disrupts the continuity required for effective learning and institutional development. This finding is consistent with research by Setyasih (2023), who argued that high turnover in public institutions leads to a loss of institutional memory and hampers long-term planning. In South African municipalities, this challenge is particularly acute at the management level, where leadership continuity is critical for the success of long-term learning initiatives. The constant hiring and retraining cycle drains resources and stalls innovation, as new hires often lack the institutional knowledge and training necessary to contribute to continuous learning programs immediately.

6.6 Theoretical and practical contributions

This study contributes to the literature on organizational learning by extending Senge’s (1990) model to the public sector, specifically in the context of local government in a developing country. The findings underscore the adaptability of Senge’s framework but also highlight its limitations when applied to highly bureaucratic and politically charged environments. While systems thinking, personal mastery, and team learning are theoretically sound, their practical implementation requires additional structural and cultural reforms addressing public institutions’ unique challenges.

The findings from this study reveal that organizational learning principles not only enhance municipal service delivery but also hold significant interdisciplinary value. By drawing on public administration, sociology, and organizational studies insights, organizational learning contributes to a holistic approach to governance challenges. Its emphasis on systems thinking, team learning, and shared vision can be applied across disciplines to address complex, multifaceted problems. For instance, in urban governance, integrating social dynamics (from sociology) and administrative efficiency (from public administration) facilitated a comprehensive analysis of bureaucratic inefficiencies. This interdisciplinary approach demonstrates the broad applicability of organizational learning, making it a valuable framework for addressing challenges that require collaboration between diverse academic and practical fields.

In practical terms, the study provides actionable insights for policymakers and municipal leaders. It suggests that while learning organizations can be crucial in enhancing municipal governance, they cannot function effectively in isolation. A parallel effort must be made to reform political and administrative structures, invest in skills development, and create an organizational culture that embraces change.

7 Conclusion and recommendations

To explore the efficacy of continuous learning programs in South African municipal government toward curbing and removing bureaucratic red tape in public service delivery, the study utilized Pete Senge’s Model of Learning Organizations, which provides for learning structures and systems that are responsive to the needs of public officials. The study data analysis revealed several harmful elements that either help or hinder the shift toward learning organizations in government agencies. These challenges include political and administrative opposition, cultural stagnation, attitudes resistant to change, a lack of necessary skills, and significant employee turnover.

While there is much promise for local government transformation by adopting learning organization principles, these findings show that many obstacles still stand. Staff members’ reluctance to change, especially among the more senior members of the workforce, inadequate training in creating and maintaining online learning environments, and excessive employee turnover all pose problems for the continuity of operations and the preservation of institutional knowledge. In addition, new learning frameworks are frequently hindered by political and administrative intervention. This shows the importance of a stable policy climate that supports learning principles and effectively applies them.

The study adds to the body of knowledge on improving the responsiveness and efficiency of local government operations by integrating continuous learning. To foster an atmosphere favorable to continual education and improvement, thorough training programs, programs to develop leadership, and activities to alter culture must be implemented. These measures should be customized to suit the local context.

The study’s limitations stem from its confinement to a narrow set of South African municipalities. Furthermore, the quantitative effect of learning organization principles on bureaucratic efficiency could go unnoticed due to methodological decisions prioritizing qualitative findings. Notwithstanding these caveats, the findings illuminate the mechanics of ongoing learning in intricate bureaucratic contexts.

Further research is required to understand further the link between specific learning organization methods and enhancements in the delivery of municipal services. Leadership styles and their effect on public sector learning initiative performance should also be the subject of future research. If these gaps were filled, our knowledge of establishing and maintaining learning organizations in different municipal settings would be enhanced. Finally, this study illuminates the structural and operational shifts necessary to transform local government into learning organizations. It requires all stakeholders to work together to build in-house systems for continuous learning that are in sync with educational and technology trends and firmly ingrained in the ethos of city administrations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of KwaZulu-Natal Research Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ES: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Software. TM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was financially supported by the Local Government Sector Education and Training Authority (LGSETA). The funding organization played no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of the findings, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Municipal services include essential services like water, sanitation, electricity, and waste management, while municipal goods refer to tangible infrastructure such as roads, public parks, and housing.

References

Ahmad, B. (2021). Study on learning organizations in Makassar City government. J. Asian Multicult. Res. Soc. Sci. Study 2, 30–37. doi: 10.47616/jamrsss.v2i4.217

Al-Karaeen, M., and Al-Ashaab, A. (2021). Toward the digitalisation of the organisational learning capability to enhance organisational performance. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 18, 444–454. doi: 10.37394/23207.2021.18.45

Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A., (1997). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reis, 77, pp.345–348.

Antonacopoulou, E. P., Moldjord, C., Steiro, T. J., and Stokkeland, C. (2019). The new learning organisation. Learn. Organ. 26, 304–318. doi: 10.1108/tlo-10-2018-0159

Braun, V., and Clarke, V., (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3, 77–101.

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. (1996). Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act, 1996 (Act No. 108 of 1996). Pretoria: Government Printer.

Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. (1998). White paper on local government. Pretoria: Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. Available at: https://www.cogta.gov.za/cgta_2016/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/whitepaper_on_Local-Gov_1998.pdf (Accessed October 29, 2024).

Doren, D., Driessen, P., Runhaar, H., and Giezen, M. (2020). Learning within local government to promote the scaling-up of low-carbon initiatives: A case study in the City of Copenhagen. Energy Policy. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111030

Durose, C. (2011). Front-line Workers in Local Government are no Longer ‘street level bureaucrats’ but instead act as ‘civic entrepreneurs’ to make order out of chaos for their communities. Br. Polit. Policy LSE 2011:11.

Elliott, I. C. (2020). Organisational learning and change in a public sector context. Teach. Public Adm. 38, 270–283. doi: 10.1177/0144739420903783

Fushimi, K. (2022). Limits of the concepts of organisational learning and learning organisation for government-owned international development agencies. International Journal of Public Sector Performance Management doi: 10.1504/ijpspm.2022.1

Ledger, T. (2020). 'The logic of Appropriateness': understanding non-compliance in south African local government. Transformation 103, 36–58. doi: 10.1353/trn.2020.0012

Masiya, T., Davids, Y. D., and Mangai, M. S. (2021). Factors affecting the performance of south African municipal officials: Stakeholders' perspectives. Commonw. J. Local Gov. 25, 97–115. doi: 10.5130/cjlg.vi25.7701

Maynard-Moody, S., Williams, S., and Musheno, M. (2003). Cops, teachers, Counselors: Stories from the front lines of public service. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Moloi, P., Etbaigha, D., Isabirye, D., Bayat, P., and Lebelo, P. (2023). Investigating Learning Organisation Metaphor Application in Enabling the Local Municipality to Improve Service Delivery to its Communities. A Theoretical Perspective. Interciencia. doi: 10.59671/d7uqc

Moji, L., Nhede, N. T., and Masiya, T. (2022). Factors impeding the implementation of oversight mechanisms in South African municipalities. UPSpace Institutional Repository.

Olejarski, A. M., Potter, M., and Morrison, R. L. (2019). Organizational learning in the public sector: culture, politics, and performance. Public Integr. 21, 69–85. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2018.1445411

Pasieczny, J., and Rosiak, T. (2023). Barriers to implementing the concept of learning Organization in Public Administration – the example of PIORiN. Ann. Univ. Mar. Curie 56, 171–184. doi: 10.17951/h.2022.56.5.171-184

Pallett, H. (2018). Situating organisational learning and public participation: stories, spaces and connections. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 43, 215–229. doi: 10.1111/TRAN.12214

Reddy, P. (2018). Evolving local government in post-conflict South Africa: Where to?. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 33, 710–725. doi: 10.1177/0269094218809079

Reddy, P. S., and Govender, J. (2018). Democratic decentralisation, citizen engagement and service delivery in South Africa: a critique of legislative and policy considerations. Africanus 43, 78–95. doi: 10.25159/0304-615X/5080

Reese, S. (2020). Taking the learning organization mainstream and beyond the organizational level: an interview with Peter Senge. Learn. Organ. 27, 6–16. doi: 10.1108/TLO-09-2019-0136

Republic of South Africa. (1997). Water Services Act 108 of 1997. Government Gazette No. 18522. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at: https://www.gov.za/documents/water-services-act (Accessed October 29, 2024).

Republic of South Africa. (2000). Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000. Government Gazette No. 21776. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at: https://www.gov.za/documents/local-government-municipal-systems-act (Accessed October 29, 2024).

Republic of South Africa. (2006). Electricity Regulation Act 4 of 2006. Government Gazette No. 28992. Pretoria: Government Printer. Available at: https://www.gov.za/documents/electricity-regulation-act (Accessed October 29, 2024).

Senge, P. M. (1990), The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York, NY: Doubleday/Currency.

Setyasih, E. T. (2023). Creating an effective bureaucracy by reducing bureaucratic pathology in local governments. Influence 5, 137–143. doi: 10.54783/influencejournal.v5i1.112

Shava, E. (2024). Inclusive local economic development for effective service delivery in high-risk municipalities. USV Ann. Econ. Public Adm. 2, 196–207.

Springmier, K., Fonseca, C., Krier, L., Premo, R., Smith, H., and Wegmann, M. (2024). A learning Organization in Action: applying Senge's five disciplines to a collections diversity audit. Portal 24, 251–263. doi: 10.1353/pla.2024.a923706

Stewart, D. (2001). Reinterpreting the learning organisation. Learn. Organ. 8, 141–152. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000005607

Keywords: bureaucratic limitations, continuous learning, local government, service delivery normal, municipal service delivery

Citation: Shava E and Muringa TP (2024) Curbing bureaucratic limitations through continuous learning in local government in South Africa. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1435414. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1435414

Edited by:

Minela Kerla, Consultant, Sarajevo, Bosnia and HerzegovinaReviewed by:

Ahmad Sururi, Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa University, IndonesiaJohn Mamokhere, University of Limpopo, South Africa

Copyright © 2024 Shava and Muringa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa, TXVyaW5nYVRAdWt6bi5hYy56YQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Elvin Shava

Elvin Shava Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa

Tigere Paidamoyo Muringa