Abstract

This paper delves into the concept of digital leadership in contemporary democracies, considering the impact of the digital age on politics and, consequently, on political leadership. In our view, with the spread of radio stations first, then televisions, and finally the web, leadership has evolved through three great stages: broadcast, telegenic and digital. The web, and social media in special, have reshaped democracies and political interactions both at macro, meso, and micro levels. With Obama as forefather and across different political ideologies, a new generation of politicians as Beppe Grillo, Justin Trudeau, Giorgia Meloni or Sanna Marin, among others, shows how leaders are adapting to a highly digitalized political environment. As we understand it, leaders with good digital media abilities need to excel in three skills –presence, interaction and engagement– and would have two main attributes: reliability and relatability. We also consider that the digitalization of leadership deepens the personalization and presidentialization phenomena in politics and under certain circumstances may provide cases of so-called hyper-leadership more frequently.

1 Introduction

The concept of leadership is traditionally related to other notions like sovereignty, ruling, representation, or authority. First records of theory about political leadership are attributed to the idea of philosopher-guardian of Plato and the prudent statesman of Aristotle, during the Ancient Greece. Closer to our time, Max Weber configured the theory of the charismatic authority as a way of leadership which drives to the dominance of the mass, devoted to leaders with –perceived– singular and extraordinary abilities (Weber, 1978). There is, therefore, a long path of leadership theory up to nowadays, both from normative and empirical approaches (see Keohane, 2010), which allows us to appreciate the phenomenon’s relevance in history and its permanent role in the configuration of power dynamics. The research on leadership is an interdisciplinary endeavor with different schools of thought focusing on different aspects of leadership (Antonakis and Day, 2018 for an overview). Although we do not strictly relate to one single school of leadership research, our understanding mostly resonates with (a) the contextual school of leadership which describes leadership in connection with the specific environment, in our case the respective societal and media environment. Yet, there are also common grounds with (b) the relational school of leadership, focusing on leader-follower relationships and the (c) traits-oriented school where certain traits from leaders are correlated with emergence and performance.

The empirical study of political leadership in the field of social sciences is based on the consideration of multiple psycho-social and complex interactions between leaders, supporters, rivals, and their environment. Some of the seminal research has been oriented to find out the impact of political leadership on electoral behavior (Lasswell Harold, 1936; Lazarsfeld et al., 1948; Paige, 1977; Popkin, 1991) whereas other authors have developed different typologies and models of political leadership styles (Barber, 1977; Blondel, 1987; Burns, 1977; Hargrove, 1966; Kann, 1979). Overall, the subject of political leadership has kept a prominent relevance within the scholarly literature since the past century, being linked closely to other topics as the personalization of politics, populism, and polarization during recent years.

Leadership as a phenomenon of human interaction has experienced the need of adapting to many different circumstances and prevailing multiple social trends, within both authoritarian and democratic societies. It can be distinguished from other associated concepts like power and management and can be understood as “a formal or informal contextually rooted and goal-influencing process that occurs between a leader and a follower, groups of followers, or institutions” (Antonakis and Day, 2018: 5). Indeed, different political periods and contexts –like wars, conflicts, and crises but also prosperity and progress– have shaped distinct kinds of leadership styles. In this contribution, we will focus on democratic leadership, as our interest lies on the implications of the digitalization of leadership in parallel to the digitalization of politics across democratic systems, even when they are in some sort of crisis that may decreases temporarily their levels of democratic performance, but with enough civil rights and guarantees, and a free use of internet.1

During the last two decades, the emergence of the digital age has transformed many facets of our societies (Montgomery, 2007; Vaccari, 2013), including our concepts of leadership. Hence, this paper aims, firstly, to update the theory of political leadership, considering the impact of digital transformations towards what we could define as digital political leadership. Secondly, we compare the main features of leadership during the ages of radio, television, and the web, suggesting the accurate skills for successful leadership in politics nowadays. The last section of the paper provides a discussion of our frame for digital leadership as a new stage of political leadership.

2 The precedents: from the broadcast leadership to the telegenic leadership

From the advent of newspapers onward, media have re-shaped the way of doing and understanding politics (Chafee and Kanihan, 1997; Prior, 2005; Scannell, 1996; Washbourne, 2010). Already Tocqueville noted: “only a newspaper can succeed in putting the same thought in a thousand minds at the same instant” (Tocqueville, 2010: 906). We can recognize a historical path of political leadership in relation to the spreading of any new mass media since the early 20th century and the proliferation of radio stations, followed by television and, finally, the web. Despite some limitations, this umbrella approach –compatible with existing typologies– allows us considering important (desirable) common features of political leadership of each stage in recent history, leading us to the present of the digital political leadership, in which resides our interest. To illustrate features of leadership emerging over time, we will briefly summarize important developments in media systems in connection to political leadership.

Starting with the appearance of radio stations during the 1920s, they soon demanded for new skills from politicians who were only experienced in face-to-face events, the parliamentary activity and in the battle with the press journalists. From then on, politicians needed to become broadcast leaders in order to be successful. Probably, the main example of that is the American “radio president”, Frank D. Roosevelt, as remarked by Brown (2004: 9), “by the time of his death in April 1945, FDR had exploited the advantages of broadcasting so successfully that he was able to radically reshape the political, economic and social structure of the nation through the New Deal; to adequately prepare his nation for war, and to become the longest serving chief executive in American history.” This case reveals the great potential of radio broadcasting for political leaders in terms of range and impact since the early 20th century, especially while facing crises and challenges.

Radio broadcasting would be used quite frequently by other rulers like Manuel Azaña during the II Republic and the Civil War in Spain (Beevor, 2006) or by Winston Churchill in the United Kingdom during World War II (Toye, 2013). Even decades later the use of the radio would be crucial, as it is even recalled nowadays the last radio speech of Salvador Allende during the military putsch in Chile in 1973 which preceded his own death and the start of Pinochet’s dictatorship (Guardiola-Rivera, 2013). These leaders, among others, shown great rhetorical ability for oratory, argument, or persuasion, in accordance with the possibilities offered by radio broadcasting to make their messages effective (Lawton, 1930). And, as pointed out by Risso (2013), the radio still played an essential role during all the Cold War period, permeating both sides of the Iron Curtain.

Nevertheless, the unprecedented revolution in political communication was encountered through television, beginning in the 1960s. On this new terrain, J. F. Kennedy was the first politician mastering his presence on TV and gaining politically from his media appearances (Watson, 1994). In Europe, German chancellor Helmut Schmidt was another excellent communicator in front of cameras, despite his concern about the growing influence of TV in daily politics that led to his recommendation every family should switch off their televisions one day a week (Birkner, 2015). Indeed, television opened a new full scope for general entertainment based on leaders’ personal time, meaning a turning point in politics. As highlighted, “the politicians’ instrumental use of their private lives for campaign purposes has tempted the media to push further the boundaries of what is acceptable coverage” (Holtz-Bacha, 2004: 51). This trend concerns parliamentary and (semi-)presidential systems alike: scholars identify tendencies of personalization (Musella, 2018, for an overview). Poguntke and Webb (2005; 2013) even go as far as introducing the term “presidentialization”, which in itself seems a bewildering term for parliamentary, party-centered systems. However, this term aims at capturing the tendency of mostly focusing on political leaders in these systems instead of party executive boards or party manifestos and proposals.

Considering other cases, the great ability to speak to the nation through television in critical moments during the transition to democracy and the first years of democratic government with a very fragmented parliament was one of the main components of what Linz (1993) identified as “innovative leadership” in the person of the Spanish centrist prime minister Adolfo Suárez; although his telegenic skills would be exceeded by his charismatic successor in office, the socialist Felipe González, whose charisma helped the PSOE to stay in power even facing a dramatic economic crisis (Share, 1988). On the other ideological side, Margaret Thatcher managed virtuously the TV atmosphere along all her political career, while dominating techniques like turn-taking and interruption during interviews and debates (Beattie, 1982). Today, we can consider these as the telegenic leaders, able to make television their natural environment, no matter if the reason to be filmed was a news interview, a public address, or a costumbrist family report.

Retaining the skills of traditional broadcast leaders, these emerging telegenic figures needed to excel in terms of their image and debating abilities, not only using their words but their non-verbal communication too. They also required the capacity to captivate the television audience, akin to Nelson Mandela’s adept leadership in guiding the emerging rainbow nation (Evans, 2010). We will later continue this path of joint development of media and political leadership by sketching leadership in the digital environment. Before, we will go on with some general remarks on the digitalization of politics to better set the context.

3 Changes in political leadership during the digital age

3.1 The digitalization of politics

With the so-called digital revolution (Dai, 2000), a rather global change of circumstances has evolved and unfolds its impact on what can be considered a leader, and more specifically even what shaped the features of political leaders. That revolution has firstly impacted the economy, transforming the market and the division of labor, and has been accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic since 2020 (Soto-Acosta, 2020) and the Artificial Intelligence (Elliott, 2019). Undoubtedly, economic transformations have implied social changes as well, as the rise of the internet culture, the spread of the social media usage, and the appearance of a new generation of digital natives with new patterns of information consumption and a distinguishable political behavior, more oriented to the new online public space instead of face-to-face interactions (Miller, 2020; Montgomery, 2007; Ohme, 2019).

Along with these societal changes, journalism and the media underwent changes as well: the digitalization of traditional media and the proliferation of new digital media, experiencing increased levels of media polarization, waves of dis/misinformation, and ‘infotainment’ as a significant source of political insight (Kubin and Sikorski, 2021; Moy et al., 2005; Otto et al., 2017; Swire et al., 2017). In that sense, digitalized media systems have been headed to “re-discover” the audiences and making their experiences more interactive and inclusive, allowing citizens to participate in the process of generating information and to contribute to the elaboration of the contents finally published (Loosen and Schmidt, 2012).

Politics have been linked to every previously mentioned structural transformation and have digitalized in their own fashion, including the macro, meso, and micro level of politics. Starting with the macro level, political systems have incorporated technology in the shape of developing e-democracy and open government initiatives (Borucki and Hartleb, 2023; Kneuer, 2016; Wirtz and Birkmeyer, 2015). Consequently, open data and digital tools are reshaping democracies, enabling ways for larger channels of direct democracy, including participation and deliberation procedures, and for a better control of politicians’ activity (Jungherr et al., 2020). That also means a greater potential for civil society to influence the institutional actors during the policy cycle, increasing the legitimacy and the popularity of public policies. However, it must be considered that political institutions do not always offer the chance to take part in their processes and, when they do, the social response is sometimes less active than expected. This complexity of political participation and democratic legitimacy remains a puzzle in digitalized societies.

At the meso level, new digital parties like the Pirates, Podemos or M5S together with a more digitalized version of traditional ones have fostered the spread of disruptive models of party organizations (Barberà et al., 2021; Villaplana et al., 2023). For that, most political parties have invested good resources in increasing the user-friendliness and the security of their digital tools and solutions (Fitzpatrick and Thuermer, 2023). Firstly, political parties are using intensively social media platforms to strengthen their digital presence and to reach all kind of audiences, but they are also putting into practice other strategies like online crowdsourcing and even aspects of gamification in their decision-making processes in the case of the M5S (Biancalana and Vittori, 2023). Furthermore, parties are trying to improve their data-driven campaigning techniques in order to be more efficient in their mobilization of resources and the target of voters (Dommett et al., 2023). Also, party members conduct their own grassroots activism on social media platforms in the sense that parties and politicians carry on professionalized campaigning techniques (Ziegler, 2023). To some extent, other organizations like trade unions, associations and NGOs have experienced these changes to a similar degree (Fitzpatrick, 2018). Indeed, new international movements such as Me Too, Black Lives Matter or Fridays for Future could not be explained without declaring the essential role of digital networks as part of them. Nevertheless, even highly digitalized organizations remain vulnerable to setbacks in their digitalization processes, leading them to reconsider or discontinue certain tools or initiatives (Meloni and García-Lupato, 2022).

Finally, at the micro level, digital platforms have transformed the manner of political interactions like discussions, protests, fundraising, or creating engagement. To a certain extent, individualized and one-time digital networked actions are replacing traditional collective ones by joining homogenous and exclusive groups of people (Bennett and Segerberg, 2013). Likewise, political discussion through WhatsApp or other messaging services is not only frequent but also seems to be connected to a greater level of political activism (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2021). As corroborated by Boulianne (2020), the relationship between digital media use and political participation worldwide has increased gradually during the last decades. In that sense, it seems digital activism tends to concentrate in networked activities that have become available mainly through social media platforms (Theocharis et al., 2021: 45). A straight example is the rise of online petitions and micro-donations, as response to new digital oriented political campaigns (Vromen et al., 2022).

In summary, the digital revolution has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of politics, affecting both the characteristics of political actors and how citizens engage with them. As a result, political leaders are adapting to this new reality, using digital tools for both engagement and governance in an increasingly digitalized environment. Overall, we can distinguish scholarly work focusing on the digitalization of the bottom-up approach of politics and the top-down approach. Since the concern of this paper is political leadership and how it is performed, this paper can be considered as part of the later one.

3.2 The new digital leadership in politics

Before delving into political leadership and subsequently digital political leadership, we would like to emphasize that the notion of a leading role, as we conceptualize it, should not be inherently evaluated as either positive or negative in nature. Our interest is exploring the circumstances driving to leadership –detached from any normative notion of good leadership. When it comes to political leadership, a more digitalized environment requires leaders to be able to properly navigate the new dynamics of institutions, parties, and voters in the digital age.

Early attempts of accompanying changes in the demands of leaders suggested the term e-leadership (Avolio et al., 2000). Other studies with a stronger focus on candidacy identified Barack Obama in 2008 as the first “internet candidate” on a large scale (Bimber, 2014), changing the fashion of political campaigning globally ever since (Roemmele and Gibson, 2020), and finally becoming the first “social media president” in the White House (Katz et al., 2013). According with Matthews et al. (2022), the use of social media by leaders of every sector (politics, business, civil society, etc.) has exponentially grown in recent years, favoring new lines of research on leadership. During this time, Twitter –now X– has enjoyed the prominence as the most influential social media platform among Western political leaders (Parmelee and Bichard, 2013). While Roemmele and Gibson (2020) sketch the development of campaigning in connection to different mass media and announce the fourth era of campaigning, we argue that along with this development we also experience a development in leadership resulting in what we describe as digital leader. In consideration of the literature on digital inequalities (Scheerder et al., 2017), digital leaders are to be placed on the side of the ‘haves’ not on the side of the ‘have-nots’ on all three levels of the digital divide; therefore, they should demonstrate access, skill and the ability to profit from their online activity (outcome). We define a digital leader as a person that navigates the digital sphere with great expertise and sophistication, being able to generate beneficial outcome in terms of their function and goals. In line with Ignatow and Robinson (2017), a digital leader is rich in “digital capital”. While digital leaders may occur in many societal sub-fields, this paper is concerned with political digital leaders, whose primary objectives are typically oriented toward achieving electoral success, attaining ruling power, and exerting influence on policy-making.

The digital leader shall be able to navigate different platforms, as the variety of social media use in politics is growing (Taras and Davis, 2020). Along with X and Facebook, the use of Instagram and TikTok has been widespread. Since 2015, Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau has used Instagram to frame his governing style visually, to illustrate the Liberal Party of Canada’s values and ideas with his personal life, and to boost public discussions on issues such as the environment, youth, and technology, using celebrity culture codes (Lalancette and Raynauld, 2019). Concerning TikTok, populist far-right leaders like Marine Le Pen, Matteo Salvini, or Eric Zemmour have been pioneer, using it to spread not only negative or fear messages but also more personal, kind, and humorous content, adapting to the style of the platform (Albertazzi and Bonansinga, 2023). This is illustrated perfectly by the case of Giorgia Meloni as candidate, first, and then as prime minister. But not only top national leaders shine on social media, also local politicians as the former major of Barcelona, Ada Colau, have been pointed out as “influencers-politicians” for using social media extensively, Tik-Tok in particular, and having a very youthful communication style during her last term (Cervi, 2023). Apart from this, parliamentary representatives like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) have mobilized armies of active followers on social media (Goretti and Rodriguez, 2022).

While previous examples point to the successful use of social media from the perspective of the respective political leader, former Finish prime minister Sanna Marin, who can be described as a millennial with a natural use of social media, experienced very harsh misogynist attacks (Sakki and Martikainen, 2022). This case displays the ugly face social media may show to political leaders. In particular, most of societies have a limited understanding of female leadership, often restricted to the perception of Iron Ladies or mothers of the nation (Campus, 2013). Yet, Marin also experienced immense support from all over the world including other (mostly female) political leaders. Her fashion of coping with unjustified personal attacks, therefore, reflects a component of digital leadership as well.

While these leaders were political leaders ‘by career’, there were also some career changers becoming influential political leaders after. While this phenomenon of is not new (e.g., former US President and actor Ronald Reagan during the TV era), the particular fashion of technology and media use seems to set these new leaders apart: Beppe Grillo, who influenced the path of Italian politics drastically, is a prominent example (Milburn, 2019). Volodymyr Zelensky, who was a comedian, excelled in his performance as president so successfully that it started his political career. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, president Zelensky’s intense and sophisticated use of communication in social networks appears unmatched. His participation in numerous meetings with top international leaders through video call since the beginning of the Russian invasion was echoed in social media as well (Serafin, 2022; Zachara-Szymańska, 2023). This phenomenon of ‘celebrity politics’ goes further than a few fringe cases or a temporary fashion and seems to be “tied to the late-modern constitution of the public” (Marsh et al., 2010: 337).

However, probably the most influential incursion (or even intrusion) of a celebrity in politics in present time would be the one stared by Donald Trump, coining the beginning of the Trumpism as a global populist leadership style (Mollan and Geesin, 2020). Findings by Swire et al. (2017) suggest that people use figures like Trump as a heuristic source of information to decide what is true or false, not necessarily insisting on veracity as a prerequisite for supporting political leaders. This mechanism may be explained through the well-known two-step-flow model (Lazarsfeld et al., 1948). As a consequence, in January 2020, the world was compelled to observe the detrimental repercussions a digital leader can incite when the “Twitter-president” took advantage of the polarized public and used his influence to infuriate his supporters resulting in the forceful intrusion of the Capitol building in Washington DC (Pion-Berlin et al., 2022). The continuous tweeting and his refusal to call his supporters to calm marked a low point in American democratic history.

Besides social media and political communication, we should not forget the organizational side of digital leadership (Banks et al., 2022; Petry, 2018). Political leaders, such as party leaders and/or top candidates must understand and handle digital tools more oriented towards their capability for organizational means. That includes intra-party democracy processes, as for example the online consultation Pablo Iglesias personally promoted in 2018 on his continuity as Podemos’ leader after being morally questioned for buying with his partner, spokesperson of the party, a house in one of the best quarters of Madrid. And, of course, institutional leaders are able to actively promote and to be involved in transformative digital initiatives as Obama did with Open Government in 2009 (Villaplana et al., 2023). Furthermore, political leaders will need to master data-driven and AI-powered governance if they wish to be successful in the digital age, not only as electoral candidates or as opinion leaders.

4 Features of digital leaders

Once we have identified different elements of what implies political leadership in the digital age, we can turn to the features that (ideally) characterize digital leaders, in accordance with the literature on leadership types and styles (Blondel, 1987; Keohane, 2010). Hence, rather than presenting new traits and attributes, we refer to existing concepts and inventories, and describe their continued relevance when dealing with digital leadership. In this context, we point to literature analysing attributes of leaders of different politicians. Zaccaro et al. (2013) provide an overview of different requirements that come with the job of a leader (cognitive, social and self-motivational) and connect them to different attributes. Attributes comprehend a variety of aspects including different skills and traits (e.g., resilience, creativity, openness etc.). Their list is based on a rich literature review yet, we believe adding the dimension on media environment that a political leader specifically needs to navigate provides a gain and does not necessarily question this classification but complements it. The dimension of social requirements includes an array of communication skills and external representation of an organization. We would argue that depending on the era and its respective media environment different communication and representation skills are necessary for leaders to succeed. For example, “persuading others to accept decisions and/or endorse set directions” and “constructing and activating large social networks” are two skills integrated in the list of social requirements by Zaccaro et al. (2013: 15). Depending on the (digital) environment and available (digital) tools, the tasks associated with this skill differ. As advanced before, we formulate a typology with three stages of leadership, according to the mainstream media of their period: broadcast, telegenic and digital leaderships. We specify the communicative skills in context of the respective environment and suggest certain features that correspond with these skills.

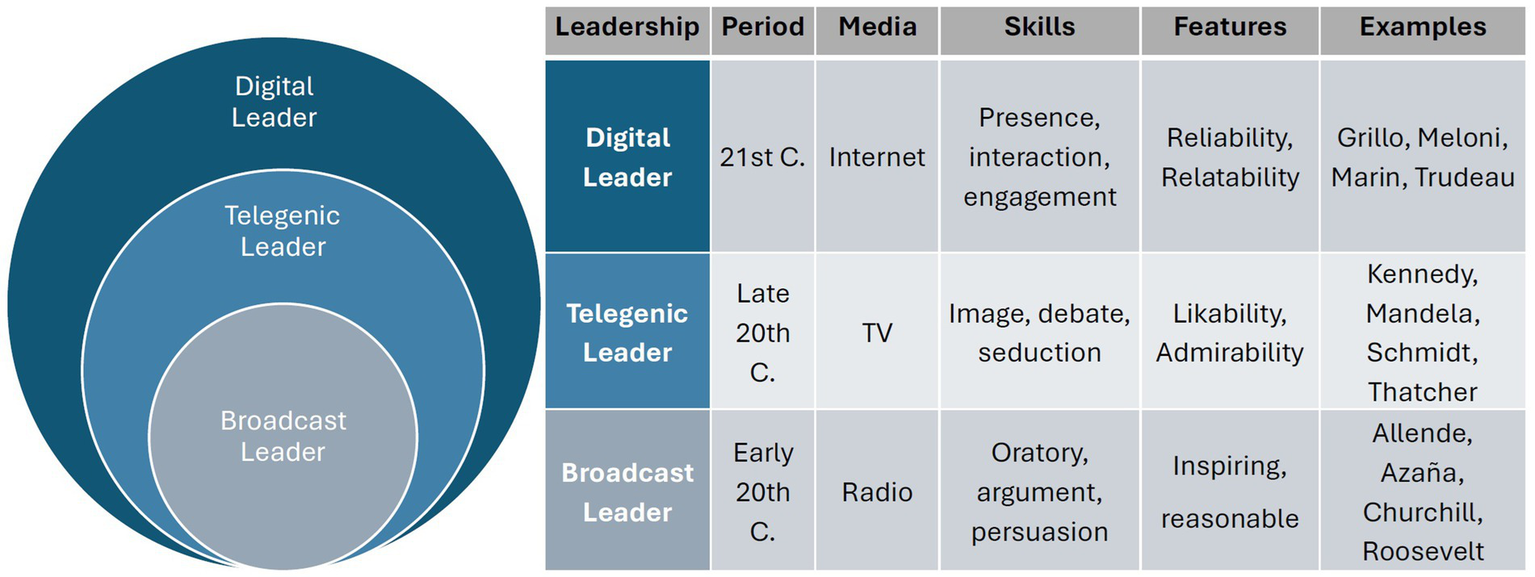

When talking about features, we believe it is necessary to briefly explain what we mean by referring to established personality models such as the five-factor model (Big5) of personality traits (Costa and McCrae, 1992). The Big5 distinguishes between neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness that are personality traits and exist in every human in varying degrees. These have been used to describe political leaders in the past (e.g., Wright and Tomlinson, 2018). While we talk about features, we believe these are linked to certain traits. Features in this sense may be seen as components of traits, i.e., conscientiousness as a dimension of the Big5 portrays itself for example in reliability. So, differently from broadcast leaders and telegenic leaders, the digital leader should have particular skills and features, as shown in Figure 1, which includes some examples of leaders. The different types are not exclusive. On the contrary, as far as, for instance, radio broadcasting and internet podcasting are similar activities, the newer leadership type must include the expertise of the previous ones, improving and adapting their skills and attributes to the new media environment. And, of course, digital leaders want to be as much seductive and charming as telegenic leaders were (see Hart, 1999); but not only on TV, for sure on digital platforms even more, enjoying a greater control of the image they project, by posting, editing, using filters, etc., by themselves or their closest advisors (also requiring social media experts in their teams, disrupting the assignments and balances within the party organization). While during the time of radio leaders aimed to be good at broadcasting and then, telegenic performers on TV, nowadays, they do their best for being successful social media personalities and, eventually, even showing themselves as tech enthusiasts.

Figure 1

Onion-model of leadership stages.

In our view, leaders with good digital media abilities would excel in three skills: presence, interaction and engagement. By presence we understand they have a profile in different social media and post contents frequently on each of them. This social media strategy makes sense in a multiplatform environment where there are different generations of voters using mainly one or two platforms and probably ignoring the rest of them. Leaders want to reach as much voters as possible. Second, by interaction we mean that digital leaders benefit from hybrid media systems (Chadwick, 2017) where they can spread their messages not only unidirectionally like on traditional media but also exchange with supporters, journalists, and other politicians. A digital leader is the opposite to an isolated leader, but an interactive leader (Sørensen, 2020) with huge digitally traceable political and personal networks. We can assess their level of interaction by examining metrics such as likes, shares, retweets, or other platform-specific actions they make, as well as by analyzing how they get involved in debates with other politicians, discussions with journalists, and feedback exchanges with citizens through digital platforms. Thirdly, we see engagement as the ability of digital leaders for keeping supporters’ attention and endorsement. Leaders constantly post what they do, thanks to the very effective way of online communication, being quick, direct, and brief, using few words but much symbolism in their messages and actions throughout digital platforms. Consequently, we can understand engagement as the combination of interactions they receive (such as likes, shares, or comments) along with other positive emotional responses, such as identification, solidarity, or admiration from their audience.

In accordance with their skills, digital leaders would have two main features, as we conceive it: reliability (trust) and relatability (as one of us). As the Trump example showed (Mollan and Geesin, 2020; Swire et al., 2017), digital leaders provide a trusted source of political information, according with the beliefs of their supporters, no matter if it is actually the truth or not. This can make their supporters feel safe from the annoying infoxication and, in the end, this can make their lives easier as they might perceive it. Concerning relatability, the increasing use by politicians of platforms like Instagram and TikTok –more visual and focused on personal lifestyle and entertainment than X or Facebook (Albertazzi and Bonansinga, 2023; Taras and Davis, 2020)– may increase the feeling of proximity to the regular people. So, while broadcast leaders had to be inspiring and reasonable using their oratory, argument, and persuasion skills, digital leaders can be inspiring and reasonable as well, but in their own way: focusing on providing trust and closeness to their audience.

Furthermore, as highlighted before, digital leadership skills and attributes go beyond political communication, and they would be noticed in the rest of their digital activities, such as managing the party organization or exercising their role at a set of more digitalized parliaments and public institutions. Nevertheless, aforementioned skills and attributes apply to management the same, although other more specific ones like transparency or virtual team building could be also considered as desirable ones.

5 Discussion and conclusion

By introducing the concept of digital political leadership, at this point, we have displayed what we consider a new stage of political leadership, explained by the changes that politics are experiencing at the macro, meso, and micro levels during the digital age. For a great number of reasons, it can be safely said that political leadership in the 21st century has new particular features, affecting leaders’ communicational style, their decision-making and the performance of their many roles. This is happening quickly, in fact, some of the first generation of digital leaders after Obama like Marin have already left government or have even abandoned politics like Grillo and Iglesias. Indeed, the former two together with the leaders of the different Pirate Parties can be considered the first cases of native digital leaders, as they emerged as the faces of those new digital parties (Barberà et al., 2021). In contrast, most leaders operate only partially digitalized, allowing us to understand the concept of digital leaders as an umbrella category characteristic of our time. This concept can still be complemented with other features of political leadership, considering both their degree of digitalization and additional factors such as personality traits and management styles.

In our view, the digitalization of leadership deepens the personalization and presidentialization phenomena in politics. As identified by Poguntke and Webb (2005: 343) there is a “clear cut trend towards the growth of leaders’ power within, and autonomy from, their parties”. The more freedom they enjoy expressing and acting by themselves with respect their party organizations – thanks to social media and digital platforms – the more prominence they have in the public eye. Also, polemics in social media tend to make public issues even more personal (Bennett and Segerberg, 2013), and this appears to be more often the case in highly polarized systems. Most probably, many democracies are going to experience increasing phenomena of hyper-leadership in the digital age (Blasio and Viviani, 2020) due to the increasement of more personalistic and emotional political dynamics and less materialistic ways of rationality. This trend includes newly elected members of the European Parliament, such as Fidias Panayiotou (Fidias) in Cyprus and Alvise Pérez (SALF) in Spain, both social media influencers who have successfully transitioned to populist politics, achieving notable success in the 2024 European elections.

The goal of this paper was to draw the path of political leadership development in context of changes in the media landscape. As a result, we identified (optimal) digital leaders as individuals with exceptional ability to navigate the digital sphere, demonstrating outstanding skills in presence, interaction, and engagement on digital platforms, making them both reliable and relatable. Future research on digital leadership may explores the identification of sub-types or styles by analyzing a range of indicators. Additionally, more in-depth analyses of the connection between digital leadership, populism, and polarization are required to explore the phenomenon that social media may offer a window of opportunity for populist outsiders, who, in turn, contribute to the intensification of polarization dynamics. The influential cases mentioned in this paper show the necessity and relevance of a better understanding of digital and political leadership, going beyond the limits of this concept analysis. In a next step, to the measurement of these types and therefore the systematic, empirical test is necessary.

Statements

Author contributions

FV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. FRV acknowledges the Spanish Government and the University of Murcia for a Margarita Salas grant (UM6488), funded by NextGenerationEU.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ For the relationship between digitalisation and authoritarian leaderships see the recent work of Kendall-Taylor et al. (2020) and Schlumberger et al. (2023).

References

1

Albertazzi D. Bonansinga D. (2023). Beyond anger: the populist radical right on TikTok. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud.32, 673–689. doi: 10.1080/14782804.2022.2163380

2

Antonakis J. Day D. V. (2018). “Leadership: past, present, and future” in The nature of leadership. eds. AntonakisJ.DayD. V.. 3rd ed (Cham: Sage Publications, Inc.), 3–26.

3

Avolio B. J. Kahai S. Dodge G. E. (2000). E-leadership. Leadersh. Q.11, 615–668. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00062-X

4

Banks G. C. Dionne S. D. Mast M. S. Sayama H. (2022). Leadership in the digital era: a review of who, what, when, where, and why. Leadersh. Q.33:101634. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2022.101634

5

Barberà O. Sandri G. Correa P. Rodríguez-Teruel J. (2021). Digital Parties. Berlin: Springer International Publishing.

6

Barber J. D. (1977). The Presidential Character: Predicting Performance in the White House. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

7

Beattie G. W. (1982). Turn-taking and interruption in political interviews: Margaret Thatcher and Jim Callaghan compared and contrasted. Semiotica39:93. doi: 10.1515/semi.1982.39.1-2.93

8

Beevor A. (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish civil war 1936–1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

9

Bennett W. L. Segerberg A. (2013). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Cambridge studies in contentious politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

10

Biancalana C. Vittori D. (2023). Business as usual? How gamification transforms internal party democracy. Inf. Soc.39, 282–295. doi: 10.1080/01972243.2023.2241470

11

Bimber B. (2014). Digital Media in the Obama Campaigns of 2008 and 2012: adaptation to the personalized political communication environment. J. Inform. Tech. Polit.11, 130–150. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2014.895691

12

Birkner T. (2015). Mediatization of politics: the case of the former German chancellor Helmut Schmidt. Eur. J. Commun.30, 454–469. doi: 10.1177/0267323115582150

13

Blasio E. D. Viviani L. (2020). Platform party between digital activism and hyper-leadership: the reshaping of the public sphere. Media Commun.8, 16–27. doi: 10.17645/mac.v8i4.3230

14

Blondel J. (1987). Political leadership: Towards a general analysis. Cham: Sage.

15

Borucki I. Hartleb F. (2023). Debating E-voting throughout Europe: constitutional structures, parties’ concepts and Europeans’ perceptions. Front. Polit. Sci5:982558. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.982558

16

Boulianne S. (2020). Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation. Commun. Res.47, 947–966. doi: 10.1177/0093650218808186

17

Brown R. J. (2004). Manipulating the ether: The power of broadcast radio in thirties America. Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland.

18

Burns J. M. (1977). Wellsprings of political leadership. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev.71, 266–275. doi: 10.2307/1956968

19

Campus D. (2013). Women political leaders and the media. Berlin: Springer.

20

Cervi L. (2023). TikTok use in municipal elections: from candidate-majors to influencer-politicians. Más Poder Local53, 8–29. doi: 10.56151/maspoderlocal.175

21

Chadwick A. (2017). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

22

Chafee S. H. Kanihan S. F. (1997). Learning about politics from the mass media. Polit. Commun.14, 421–430. doi: 10.1080/105846097199218

23

Costa P. T. McCrae R. R. (1992). Four ways five factors are basic. Personal. Individ. Differ.13, 653–665. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(92)90236-I

24

Dai X. (2000). The digital revolution and governance. London: Routledge.

25

Tocqueville Alexis de (2010). Democracy in America. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

26

Dommett K. Barclay A. Gibson R. (2023). Just what is data-driven campaigning? A systematic review. Inform. Commun. Soc.27, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2023.2166794

27

Elliott A. (2019). The age of artificial intelligence: How digital technologies are transforming our lives. London: Routledge.

28

Evans M. (2010). Mandela and the televised birth of the rainbow nation. Natl. Ident.12, 309–326. doi: 10.1080/14608944.2010.500327

29

Fitzpatrick J. (2018). Digital Civil Society: Wie zivilgesellschaftliche Organisationen im Web 2.0 politische Ziele verfolgen. Berlin: Springer VS.

30

Fitzpatrick J. Thuermer G. (2023). Political parties and their online platforms–differences in philosophies. Front. Polit. Sci.5:1199449. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1199449

31

Gil de Zúñiga H. Ardèvol-Abreu A. Casero-Ripollés A. (2021). WhatsApp political discussion, conventional participation and activism: exploring direct, indirect and generational effects. Inf. Commun. Soc.24, 201–218. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1642933

32

Goretti N. Rodriguez N. (2022). From hoops to Hope: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and political fandom on twitter. Int. J. Commun.16, 65–84.

33

Guardiola-Rivera Ó. (2013). Story of a death foretold: The coup against Salvador Allende, September 11, 1973. First Edn. London: Bloomsbury Press.

34

Hargrove E. C. (1966). Presidential leadership personality and political style. New York: Macmillan.

35

Hart R. P. (1999). Seducing America: How television charms the modern voter. Cham: Sage.

36

Holtz-Bacha C. (2004). Germany: how the private life of politicians got into the media. Parliam. Aff.57, 41–52. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsh004

37

Ignatow G. Robinson L. (2017). Pierre Bourdieu: theorizing the digital. Inf. Commun. Soc.20, 950–966. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1301519

38

Jungherr A. Rivero G. Gayo-Avello D. (2020). Retooling politics: How digital media are shaping democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

39

Kann M. E. (1979). A standard for democratic leadership. Polity12, 202–224. doi: 10.2307/3234277

40

Katz J. E. Barris M. Jain A. (2013). The social media president. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

41

Kendall-Taylor A. Frantz E. Wright J. (2020). The digital dictators. Foreign Aff.99, 103–115.

42

Keohane N. O. (2010). Thinking about leadership. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

43

Kneuer M. (2016). E-democracy: a new challenge for measuring democracy. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev.37, 666–678. doi: 10.1177/0192512116657677

44

Kubin E. Sikorski C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: a systematic review. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc.45, 188–206. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2021.1976070

45

Lalancette M. Raynauld V. (2019). The power of political image: Justin Trudeau, Instagram, and celebrity politics. Am. Behav. Sci.63, 888–924. doi: 10.1177/0002764217744838

46

Lasswell Harold D. (1936). Politics: Who gets what, when, how. New York: Whittlesey House.

47

Lawton S. P. (1930). The principles of effective radio speaking. Q. J. Speech16, 255–277. doi: 10.1080/00335633009360886

48

Lazarsfeld P. F. Berelson B. Gaudet H. (1948). The People's choice: How the voter makes up his mind in a presidential campaign. New York: Columbia University Press.

49

Linz J. J. (1993). “The innovative leadership in the transition to democracy and in a new democracy” in SUNY series in leadership studies. Innovative leaders in politics. ed. ShefferG. (New York: State University of New York Press), 141–186.

50

Loosen W. Schmidt J. (2012). (Re-)discovering the audience. The relationship between journalism and audience in networked digital media. Inf. Commun. Soc.15, 867–887. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2012.665467

51

Marsh D. Hart P. Tindall K. (2010). Celebrity politics: the politics of the late modernity?Polit. Stud. Rev.8, 322–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-9302.2010.00215.x

52

Matthews M. J. Matthews S. H. Wang D. Kelemen T. K. (2022). Tweet, like, subscribe! Understanding leadership through social media use. Leadersh. Q.33:101580. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101580

53

Meloni M. García-Lupato F. (2022). Two steps forward, one step Back: the evolution of democratic digital innovations in Podemos. South Eur. Soc. Polit.27, 253–278. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2022.2161973

54

Milburn K. (2019). The comedian as populist leader: Postironic narratives in an age of cynical irony. Leadership15, 226–244. doi: 10.1177/1742715018809750

55

Miller V. (2020). Understanding digital culture (second edition). Cham: Sage.

56

Mollan S. Geesin B. (2020). Donald Trump and Trumpism: leadership, ideology and narrative of the business executive turned politician. Organization27, 405–418. doi: 10.1177/1350508419870901

57

Montgomery K. C. (2007). Generation Digital. London: The MIT Press.

58

Moy P. Xenos M. A. Hess V. K. (2005). Communication and citizenship: mapping the political effects of infotainment. Mass Commun. Soc.8, 111–131. doi: 10.1207/s15327825mcs0802_3

59

Musella F. (2018). Political leaders beyond party politics. Berlin: Springer International Publishing.

60

Ohme J. (2019). When digital natives enter the electorate: political social media use among first-time voters and its effects on campaign participation. J. Inform. Tech. Polit.16, 119–136. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2019.1613279

61

Otto L. Glogger I. Boukes M. (2017). The softening of journalistic political communication: a comprehensive framework model of sensationalism, soft news, infotainment, and tabloidization. Commun. Theory27, 136–155. doi: 10.1111/comt.12102

62

Paige G. D. (1977). The scientific study of political leadership. New York: Free Press.

63

Parmelee J. H. Bichard S. L. (2013). “Politics and the twitter revolution: how tweets influence the relationship between political leaders and the public” in Lexington studies in political communication. 1st ed (Plymouth: Lexington Books).

64

Petry T. (2018). “Digital leadership” in Knowledge management in digital change: New findings and practical cases. eds. NorthK.MaierR.HaasO. (Berlin: Springer), 209–218.

65

Pion-Berlin D. Bruneau T. Goetze R. B. (2022). The trump self-coup attempt: comparisons and civil–military relations. Gov. Oppos.18:13. doi: 10.1017/gov.2022.13

66

Poguntke T. Webb P. (Eds.) (2005). The presidentialization of politics: A comparative study of modern democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

67

Popkin S. L. (1991). The reasoning voter: Communication and persuasion in presidential campaigns. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

68

Prior M. (2005). News vs. entertainment: how increasing media choice widens gaps in political knowledge and turnout. Am. J. Polit. Sci.49, 577–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00143.x

69

Risso L. (2013). Radio wars: broadcasting in the cold war. Cold War History13, 145–152. doi: 10.1080/14682745.2012.757134

70

Roemmele A. Gibson R. (2020). Scientific and subversive: the two faces of the fourth era of political campaigning. New Media Soc.22, 595–610. doi: 10.1177/1461444819893979

71

Sakki I. Martikainen J. (2022). ‘Sanna, Aren't you ashamed?’ Affective-discursive practices in online misogynist discourse of Finnish prime minister Sanna Marin. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol.52, 435–447. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2827

72

Scannell P. (1996). Radio, television, and modern life: A phenomenological approach. Oxford: Blackwell.

73

Scheerder A. van Deursen A. van Dijk J. (2017). Determinants of internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second- and third-level digital divide. Telematics Inform.34, 1607–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.07.007

74

Schlumberger O. Edel M. Maati A. Saglam K. (2023). How authoritarianism transforms: a framework for the study of digital dictatorship. Gov. Oppos.59, 761–783. doi: 10.1017/gov.2023.20

75

Serafin T. (2022). Ukraine’s president Zelensky takes the Russia/Ukraine war viral. Orbis66, 460–476. doi: 10.1016/j.orbis.2022.08.002

76

Share D. (1988). Dilemmas of social democracy in the 1980s. Comp. Pol. Stud.21, 408–435. doi: 10.1177/0010414088021003005

77

Sørensen E. (2020). Interactive political leadership: The role of politicians in the age of governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

78

Soto-Acosta P. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: shifting digital transformation to a high-speed gear. Inf. Syst. Manag.37, 260–266. doi: 10.1080/10580530.2020.1814461

79

Swire B. Berinsky A. J. Lewandowsky S. Ecker U. K. H. (2017). Processing political misinformation: comprehending the trump phenomenon. R. Soc. Open Sci.4:160802. doi: 10.1098/rsos.160802

80

Taras D. Davis R. (2020). Power shift? Political leadership and social media: Case studies in political communication (1st). London: Routledge.

81

Theocharis Y. Moor J. Deth J. W. (2021). Digitally networked participation and lifestyle politics as new modes of political participation. Policy Internet13, 30–53. doi: 10.1002/poi3.231

82

Toye R. (2013). The roar of the lion: The untold story of Churchill's world war II speeches (first edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

83

Vaccari C. (2013). Digital politics in Western democracies: A comparative study. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

84

Villaplana F. R. Megías A. Sandri G. (2023). From open government to open parties in Europe. A framework for analysis. Frontiers. Pol. Sci.5:1095241. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2023.1095241

85

Vromen A. Halpin D. Vaughan M. (2022). “Crowdsourced politics,” in The rise of online petitions & micro-donations. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

86

Washbourne N. (2010). Mediating politics: Newspapers, radio, television and the internet. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

87

Watson M. A. (1994). The expanding vista: American television in the Kennedy years. Oxford: Duke University Press.

88

Weber M. (1978). Economy and society. An outline of interpretive sociology. Berkeley: University of California Press.

89

Wirtz B. W. Birkmeyer S. (2015). Open government: origin, development, and conceptual perspectives. Int. J. Public Adm.38, 381–396. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2014.942735

90

Wright J. D. Tomlinson M. F. (2018). Personality profiles of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump: fooled by your own politics. Personal. Individ. Differ.128, 21–24. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.02.019

91

Zaccaro S. J. LaPort K. José I. (2013). “The attributes of successful leaders: a performance requirements approach” in The Oxford handbook of leadership. ed. RumseyM. G. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 11–36.

92

Zachara-Szymańska M. (2023). The return of the hero-leader? Volodymyr Zelensky’s international image and the global response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Leadership19, 196–209. doi: 10.1177/17427150231159824

93

Ziegler S. (2023). Watching the digital grassroots grow: assessing party members’ social media campaigning during the 2021 German bundestag election. Policy Stud.45, 818–838. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2023.2229248

Summary

Keywords

political leadership, digital politics, political parties, social media, digital natives

Citation

Villaplana FR and Fitzpatrick J (2024) Digital leaders: political leadership in the digital age. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1425966. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1425966

Received

30 April 2024

Accepted

06 December 2024

Published

18 December 2024

Volume

6 - 2024

Edited by

Micah Altman, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States

Reviewed by

Rubén Rivas-de-Roca, University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Fabio Lupato, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Villaplana and Fitzpatrick.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: F. Ramón Villaplana, rvillaplana@um.esJasmin Fitzpatrick, fitzpatrick@politik.uni-mainz.de

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.