95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 09 December 2024

Sec. Political Participation

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1414795

Daniel Vieira1,2

Daniel Vieira1,2 Teresa Silva Dias1,2

Teresa Silva Dias1,2 Marta Sampaio1,2

Marta Sampaio1,2 Sofia Castanheira Pais1,2

Sofia Castanheira Pais1,2 Norberto Ribeiro1,2

Norberto Ribeiro1,2 Cosmin Nada1,2,3

Cosmin Nada1,2,3 Carla Malafaia1,2*

Carla Malafaia1,2*How can participatory research, combined with visual methods, enable young people to grow as engaged citizens in their communities? This article introduces an innovative methodological design that draws on a Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) approach with 33 young athletes aged 11 to 16 from two different educational settings. Based on both observation notes from the community profiling process and visual materials produced by the young people throughout that process, we analyze how they become activists, taking sports as the ground for mobilization and intervention in their communities. Specifically, we examine the visual activist strategies and the visual meaning-making representations that resulted from young people’s engagement in participatory research. Novel findings include the realization that young people with no previous experience in activism strongly prefer visual and performative formats of participation, often in connection with digital and online arenas. Additionally, data analyses reveal that participants particularly value collective moments of learning, negotiation, and preparation of activist actions. This article highlights the increasing prevalence of visual-oriented modes of civic engagement and the potential of participatory methodologies in fostering critical awareness, meaningful decision-making, and a sense of agency among young people.

In an era characterized by the influence of digital networks and platforms, particularly of visual social media, young people’s social engagement is undergoing a profound transformation (e.g., Kharroub and Bas, 2016; Luhtakallio and Meriluoto, 2022; Mattoni and Teune, 2014). At the same time, and in line with the development of participatory research approaches (Buttimer, 2019; Cammarota and Fine, 2008), it is crucial to allow room for young people to practice their citizenship in ways they deem relevant and about social problems that are meaningful to them and their communities (Lawy and Biesta, 2006; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012; Warren and Marciano, 2018). This article delves into the role that visual forms of expression and participatory methodologies can play in shaping contemporary modes of young people’s socio-political engagement.

This study is developed within the project Play4Life - Young Athletes as Sport Activists, aiming to investigate how participation in sporting contexts is connected to the development of young athletes as active citizens in their communities. The aim is to explore the potential of sport in promoting civic-political skills and democratic citizenship through the mobilization of participatory methodologies linked to the young athletes’ communities. Considering that sports contexts can be powerful educational arenas for developing personal and social competencies (Hellison and Martinek, 2009; Torralba, 2017), our study involves 33 young athletes aged between 11 and 16 recruited from two different contexts. The study is grounded in a participatory research design, through which the young people were engaged in a community profiling process (Arcidiacono et al., 2001; Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012), identifying problems affecting them and their life contexts. Supported by the researchers and equipped with activist tools, the young participants planned community-based interventions concerning problems that ranged from gender inequality to bullying. This article concentrates on the visuality that ended up shaping their citizenship practices and expressions. On the one hand, the visual forms of participation that the young athletes spontaneously adopted when carrying out activist interventions in their communities. On the other hand, the visual-based exploration of the meanings ascribed by the young participants to their involvement in the participatory research project. Concretely, we analyze and discuss the visual activist strategies and the visual meaning-making representations that resulted from the young people’s engagement in a participatory process through which they researched about and intervened in their communities.

This article is grounded on two research questions: (RQ1) in which ways do young people adopt visual and online forms of activism in the context of participatory research processes?; (RQ2) how do visual methods enable grasping the meanings that young people attribute to those participatory processes?

By focusing on both the modes of activism developed by the young athletes and their reflections regarding the involvement in a participatory research project, this article has two main objectives: (i) to reflect on the role of youth-led participatory methodologies in the promotion of active citizenship, and (ii) to explore the preferences of young individuals for visual forms of civic and political participation. Through these interconnected objectives, our study offers insights into the interplay between participatory methodologies and visual forms of action and expression in young people’s civic and political development.

In this article, we argue that the growing use of visual social media affordances as means of participation and politicization is not exclusive of organized social movements; rather, it is spontaneously adopted by diverse groups of young people with no experience in political participation and who are far from identifying themselves as activists. Regarding the first research question (RQ1), we observed that, as these young people engage in participatory research processes and start envisioning and driving change within their communities, they intuitively adopt visual and digital forms of activism (ranging from the crafting of protest banners and posters to the recording of videos to performatively embody social critique and the production of images to stir social media). Concerning the second research question (RQ2), our data show that incorporating visual methods into Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) significantly enriches the research process. Aligning participatory research approaches with the predominance of visuality in young people’s practices enables a deeper understanding of the meanings they assign to their engagement in YPAR processes. Indeed, the young participants in our project used diverse visual genres (e.g., paired images, cartoons, photo assemblages) to represent their feelings and perceptions on various aspects of the YPAR process, particularly regarding the challenges of collective decision-making and planning activist interventions. We contend that methodological approaches that recognize the visual nature of today’s public sphere and contemporary youth sociability foster more democratic action research processes, enhancing critical awareness while strengthening young people’s sense of agency.

The role of young people’s civic and political engagement in the construction of democracies has been widely problematized, both in scientific studies (e.g., Malafaia, 2022; Ribeiro et al., 2023; Ekman and Amnå, 2012; Marsh et al., 2006; Norris, 2002) and in public policies (e.g., Council of Europe, 2015; Eurydice, 2005; OECD, 2018; UNICEF, 2022). Literature in this field consistently points to two broad dimensions that need to be considered: (i) on the one hand, the importance of approaching young people’s relationship with politics, taking into account the changing and diverse formats of civic and political engagement (e.g., Ribeiro et al., 2017; Malafaia et al., 2021; Ekman and Amnå, 2012; Norris, 2002); (ii) on the other hand, the need for participatory research practices, catalyzed by the kinds of issues and actions that young people deem significant in their lives and communities (e.g., Pais et al., 2014; Buttimer, 2019; Lawy and Biesta, 2006). At stake, in both dimensions, is the value of approaching young people’s citizenship in their terms, from a bottom-up perspective, overcoming adultist frames regarding what young people’s participation should look like: how their claims should be articulated and which issues are worthy of their mobilization.

Research shows that young people’s disengagement mainly relates to conventional politics, which is both a consequence of their formal/legal exclusion from electoral politics and a symptom of their distrust of formal political institutions and their preference for more decentralized, fluid, and horizontal modes of engagement (e.g., Malafaia et al., 2021; Casas and Williams, 2019; Ekman and Amnå, 2012; Norris, 2002). In this context, digital tools and online spaces come as part and parcel of the contemporary forms of young people’s claim making, accommodating diverse types of expression and expanding the reach of mobilization (Malafaia and Meriluoto, 2022; Doerr et al., 2013; Kharroub and Bas, 2016; Sandin et al., 2023). A paradigmatic example is the key role of social media in today’s activism. These platforms provide opportunities for young people to build their narratives and representations beyond conventional media affordances (Kharroub and Bas, 2016; Luhtakallio and Meriluoto, 2022; Ugwuanyi et al., 2019), even though these often encompass negotiations with the corporative and capitalist logic underlying the algorithmic infrastructures (Malafaia and Meriluoto, 2022). Indeed, the prevalence of visual social media among youth citizenship practices highlights today’s visual character of the young people’s modes of engagement, argumentation, and politicization, calling for an examination of participation beyond its verbal components (Luhtakallio et al., 2024). The notion of ‘image events’ (Delicath and DeLuca, 2003) crystallizes the role of visual imagery in contemporary activist practices by conceptualizing protest visualities as post-modern forms of argumentation among social movements. Recent studies show the potential of picture-taking practices and online visual activism as powerful tools among underprivileged and marginalized people to draw public attention to social problems, articulate their claims, and contest cultural and societal norms (Meriluoto, 2023; Sandin et al., 2023).

Images are particularly mobilizing due to their ability to trigger stronger emotional responses than words (Casas and Williams, 2019; Catanzaro and Collin, 2023; Powell et al., 2015). Images also facilitate the long-term retention of information, as demonstrated in a study conducted by Ugwuanyi and colleagues in 2019. This research revealed that social media users favor visual content over extensive text and opt to express their political opinions and convey their views through images. From an educational point of view, using images seems to bring important benefits, even if it challenges more traditional practices and pedagogies (e.g., Vera Romero et al., 2018). Vera Romero and colleagues point out that photography can render classes more participatory, develop visual literacy, and improve reading and writing skills when used as a pedagogical tool. Additionally, it is emphasized that images can stimulate critical thinking (Emme, 2001), promote the willingness to fight against global injustices and improve communitarian modes of living (Lam and Trott, 2022).

Considering the aforementioned emergence of new forms of participation embraced by young people, scholars have been recommending the adoption of participatory methodologies to enhance young people’s learning experiences (Pais et al., 2014; Catanzaro and Collin, 2023) and also to overcome what has been identified as recurrent research pitfalls in the field of young people’s participation – e.g., “the extractivist research,” the “individual-collective dichotomy,” the “ever-search for the spectacular” (Malafaia and Fernandes-Jesus, 2024). In other words, it is valuable to consider not only attention-grabbing activist events but also the everyday ways young people engage with their communities (Lawy and Biesta, 2006). In this context, the amplification of young people’s voices and their civic activation have been fostered by methodological designs that take them as co-researchers of their own reality (Pais et al., 2014; Cruz et al., 2019; Cutter-Mackenzie and Rousell, 2019).

Among methodological approaches that place young people at the center, Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) stands out because it is based on power-sharing between facilitators and participants, forefronting young people’s experiences and perspectives (Dias, and Menezes, 2013; Warren and Marciano, 2018). Existing research emphasizes the potential of YPAR to provide empowering learning experiences, enabling young people to conduct critical and action-oriented research (Buttimer, 2019; Warren and Marciano, 2018). This is generally reflected in increased critical awareness, particularly regarding socio-political dimensions, including the sense of agency and perceived efficacy in affecting change within communities (Buttimer, 2019; Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Marques et al., 2020). The community profiling approach assumes relevance in participatory and community-based methods, as it involves exploring a given community’s needs and resources. This experiential learning translates knowledge into practical application by selecting, planning, and conducting activities in, with, and for the community (Pais et al., 2014; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012). This experience enables young people to develop communication, research, and teamwork skills. Still, it also fosters participants’ political ownership as citizens, both inside and outside of school, about the past, present, and future of their communities (Menezes and Ferreira, 2012; Rios et al., 2022).

As previously discussed, young people’s political action has increasingly acquired a visual character and have relied on digital media. These transformations call not only for new research methods (Luhtakallio and Meriluoto, 2022) but also for a combination of participatory approaches with visual methods aiming at centering young voices and unpacking processes of political agency and imagination that may escape conventional methodological radars (Malafaia and Fernandes-Jesus, 2024). Photovoice is perhaps the most widely known example of a visual participatory method that has repeatedly proved relevant in young people’s learning, engagement, and active participation (Lam and Trott, 2022; Roman et al., 2023). Researchers also argue that photovoice has the capability of making visible thoughts, values, and assumptions (Greene et al., 2018), as it offers a medium to convey deeper and personal insights that would be harder to express verbally and through text (Greene et al., 2018; Wilson and Milne, 2016). Although studies mobilising participatory and visual methods have been on the rise (e.g., Buttimer, 2019; Lam and Trott, 2022; Roman et al., 2023; Wilson and Milne, 2016), important literature gaps remain: (i) the insipient articulation of visual social media with participatory research processes; (ii) the scarce research on how visuality shapes citizenship practices and young people’s relationship with politics, particularly regarding non-activist groups; (iii) the lack of attention to participatory research practices that are driven by the issues and actions that young people consider most relevant in their lives and communities. A partial exception to the first gap can be found in Marques et al.’ (2020) project, in which a school-and-community-based intervention was developed with young adolescents to address environmental problems. Instagram proved promising for involving young people in participatory research processes, facilitating picture-taking, and sharing community problems. In the case of our own project, visual social media was neither introduced nor suggested by the researchers at the beginning of the YPAR process. Instead, those platforms were spontaneously brought in by the young participants throughout their engagement in the project and, thus, emerged as part of the process of becoming activists. Consequently, we came to mobilize visual methods at a later stage of the project, when exploring the meanings young participants attributed to their engagement in the project.

This article focuses on visual forms of expression emerging from a participatory research project with young people, including: (i) visual activist actions spontaneously developed by them to tackle community problems; and (ii) visual representations of the meanings they associated with their engagement in the project. In this section, we describe our methodological design, data collection, and analytical procedures. As will be made clear, visuality took different roles in the project: having spontaneously emerged from the young people’s practices, it came to be intentionally considered to access their perceptions.

Our broad conception of youth citizenship, which extends beyond functionalist, statutory, and legalistic approaches, recognised “young people as citizens here and now” (Ribeiro et al., 2017. p.20). This aligns with a wider perspective on civic and political engagement, which is not limited to electoral participation, but also encompasses non-conventional, individual and collective, forms of involvement, ranging from signing petitions to political consumption, lifestyle politics, volunteering, squatting, sharing online content (see, for example, the typology of participation proposed by Ekman and Amnå, 2012). Considering these diverse and emerging forms of civic and political participation is crucial not only for understanding the construction (or potential endangerment) of democracy, but also for predicting future participation patterns and their relationship with politics in adulthood (Bessant, 2020; Grover, 2011).

This article draws from the project ‘Play4Life - Young Athletes as Sport Activists’ project which was inspired by the principles of YPAR (Cammarota and Fine, 2008) and operationalized through the community profiling procedures (Pais et al., 2014; Arcidiacono et al., 2001; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012). This project aimed at developing young athletes as citizens committed to building more inclusive societies. We presented the project in two distinct educational and sports contexts and recruited young participants interested in engaging in a process that would render them researchers and activists in their own communities. The first setting was a secondary school class where most students had prior experience in different sports modalities. The second context was a rugby club. All participants were students who had physical education (PE) as part of their school curriculum, with the rugby club members supplementing their PE lessons with weekly training sessions. While this existing involvement in sports may have introduced a potential bias, as participation in teams and collective activities could influence the findings, this bias mainly relates to the collective bonds formed through sports, which facilitated a smooth development of participatory research processes. The fact that the young people had already established ties with one another and functioned as a cohesive group upon our arrival plays a vital role in participatory research. This pre-existing connection is not a coincidental factor, it serves as a foundational element and a requisite for the entire framework of participatory research. While these bonds are a necessary condition, they also shape and influence the development of the research process. For example, in sports teams, there are always leading players, and it is important to ensure that such leading roles in the sports field do not automatically translate into leading roles in the participatory research process. Regarding civic and political participation, as well as activist practices and subjectivities, the young participants had no previous experiences whatsoever. In fact, as will be made clear in some of the empirical examples presented later in the article, most of the young participants expressed disbelief about their collective efficacy in making any change in their communities. We precisely explore how sports contexts and practices can potentially serve as breeding grounds for civic action and community engagement, if such societal goals are intentionally promoted and become guiding features of the groups’ ethos. Participatory methodological approaches, as this article shows, can instigate those interfaces between sports and communities and, thus, be crucial in politicizing issues that were not object of reflection nor taken as social and political before.

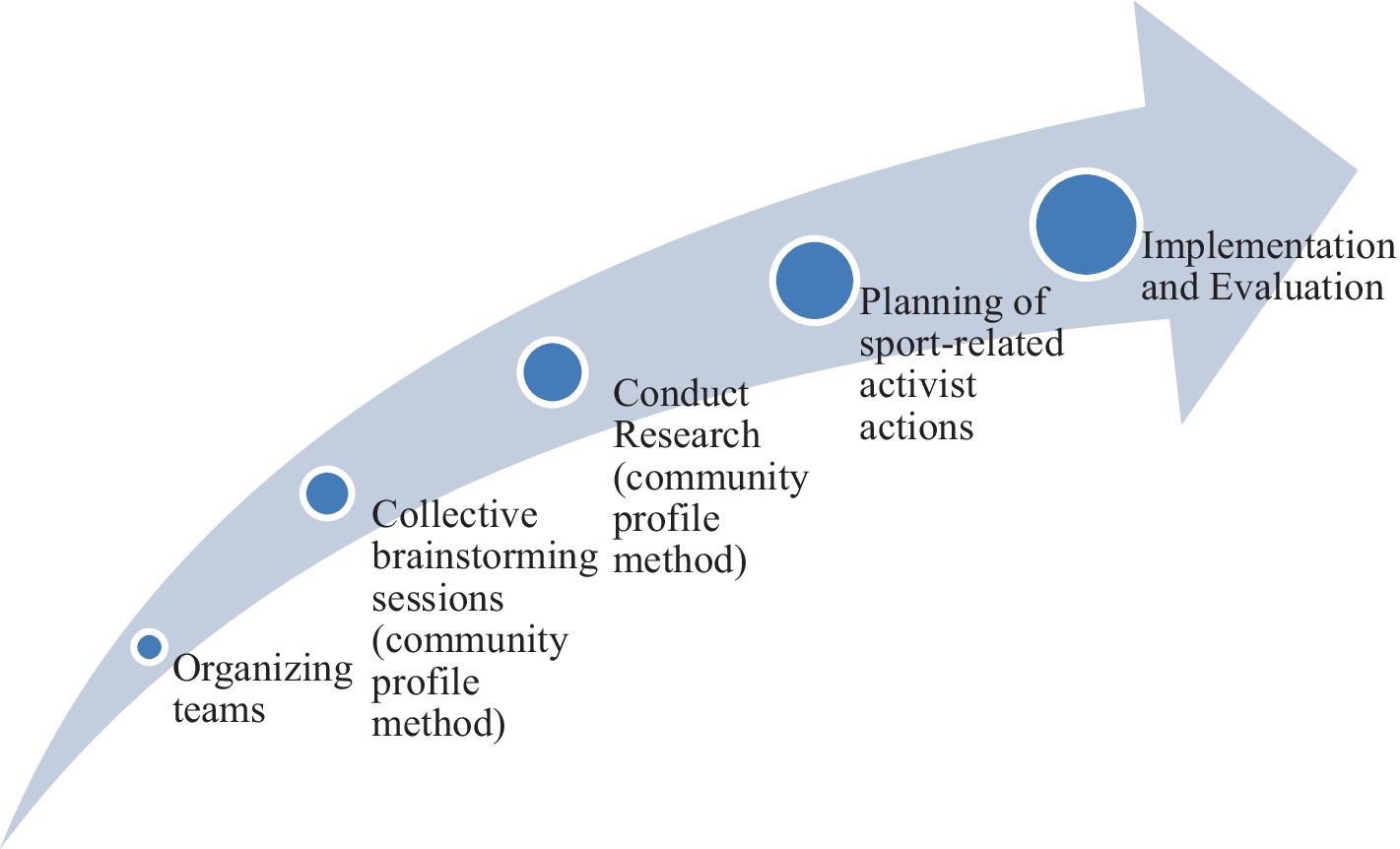

During the youth participatory action research process, the premises of the community profile method were followed (Pais et al., 2014; Arcidiacono et al., 2001; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012) throughout different steps:

i) Organizing teams: students and athletes were organized into teams, each tasked with creating a unique team identity. The school class comprised 24 students/athletes (15 girls and 9 boys), aged between 11 and 13, who subsequently divided into 4 sub-groups (which we called ‘teams’) of 6 participants each. The young athletes formed the teams according to their interests and affinities. The rugby club had 9 participants aged between 11 and 16 (8 girls and 1 boy). The number of members per group was managed according to the context so that a greater number of students could be actively involved without losing the sense of teamwork. Moreover, as recommended in the community profiling method (Arcidiacono et al., 2001; Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012), in order to ensure the active engagement of everyone and cover different community aspects felt as meaningful by the participants, big groups need to be broken down into smaller groups (teams – see Table 1).

ii) Collective brainstorming sessions: participants identified community and daily life issues that affect young people. The discussion covered a range of challenges within both contexts. The discussions also involve identifying opportunities and resources that are available in that specific community. Each team chose one issue they felt was most important to address through their sport-based intervention. The two recruiting contexts gave rise to 5 teams, with the names chosen by the young participants mirroring the issues they identified as more significant to them and urgent to be tackled: “Stoppers,”; “Contra-bullying,”; “Nutrivida [NutriLife],”; “Os Investigadores [The Researchers],”; “Equality Squad” (see Tables 1, 2).

iii) Conducting Research to find out more about the problem. Once an issue was selected, participants on each team organized themselves to deepen their understanding of the problem. This involved online searching, mapping knowledge gaps, and using interviews and questionnaires to talk and involve different agents in the community – see Table 2, which presents the data collection methods mobilized by each team according to the issues/problems chosen.

iv) Planning of sport-related activist actions that could contribute to tackle the problems and bring about change in communities. Based on the research carried out in the previous phase, each team developed intervention plans to address the identified problems through sport-related actions. They identified resources, prepared materials, and established contacts to facilitate the development of their sport-based projects. As a group, they had to share ideas, define strategies and reach consensus. Intermediate workshops were organized and conducted by the project researchers (authors of this article) and they aimed at providing the young participants with orientation and support. On the one hand, the existing types of research methods that can be used to identify community issues. On the other hand, the diverse activist practices and strategies that social movements and activists use and that can be mobilized to intervene in the community issues previously identified.

v) Implementation and evaluation: the youth teams implemented their interventions and evaluated their effectiveness through personal reflection and group assessment. In the end, the results of each group were not compared. Instead, they were brought together, composing a bigger picture of different problems and issues present in their community. Each group/team provided relevant and valuable information in its own way. Participants of all teams provided feedback on their involvement in the project, contributing to both the evaluation of the youth participatory action research process and its dissemination.

The different steps of the participatory action research process with young people can be better understood in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Participatory action research process based on the methodological premises of the community profile method.

The groups/teams gathered weekly for one hour over a period of five months (from January to May). Throughout these sessions, the young participants were supported by a local facilitator, such as a coach or a teacher, along with a researcher from the core project team, conducting participant observation. Ethical issues were considered, and the project researchers always made themselves available to address any queries or concerns that might arise throughout the project. Moreover, all participants and their parents or legal guardians willingly signed informed consent forms about their participation in the project. This consent included authorization for collecting and using images and audio files for scientific purposes. Participants’ anonymity was ensured by replacing their real names with fictitious ones, with the data protection following all legal standards (e.g., data storage on platforms exclusively accessible by the research team). Participation was free and voluntary, and the right to withdraw at any time without facing negative consequences was duly explained and regularly reiterated to all participants. The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences (Ref. 2023/02–03). As this research involved minors, consent was obtained through a vigilant exercise with the participants, checking that their willingness and interest in taking part in the research were maintained throughout the project. The research team adopted a reflexive and attentive attitude in order to deal with any discomfort experienced by the minors and maintained a caring attitude towards them, accommodating their preferences and specificities.

Throughout the weekly sessions where the young participants developed the community profile, participant observations were conducted, totaling 37 observation notes (19 sessions with the rugby group and 18 sessions with the school group). These observations served two purposes: they enabled data collection about the process and allowed for a real-time assessment regarding any adjustments needed (e.g., helping young people when the local interlocutor could not). The observation notes were coded using content analysis and refined by an inter-coder collective process (Potter and Levine-Donnerstein, 1999). Participant observation was carried out on a weekly basis by one of the project’s researchers, first author of this article, aiming to capture the nuances, decisions, challenges, and dilemmas the young participants faced throughout the process. The participant observation implied that the researcher intervened in the process only when necessary (e.g., to refocus attention to the project’s objectives or to facilitate stalled discussions and decisions).

The following findings’ sub-sections provide illustrative examples of the young participants’ process of becoming activists. The rationale and the motivations underlying their choices and actions are also explored. In total, five activist actions were developed by the young participants of the five teams.

At the final stage of the project, given the prominence of visual means of participation employed by the young people in their activist interventions, the research team considered that the final workshop session (focused on the participants’ assessment of their experience in the project) would need to integrate possibilities of visual expressions. Therefore, inspired by the photovoice method (Greene et al., 2018; Lam and Trott, 2022; Roman et al., 2023), participants were asked to exhibit in the workshop room a photograph and its corresponding caption that would represent their involvement in the project. Subsequently, they were encouraged to elaborate on that. In total, the young participants presented 20 images, which were the object of a systematic organization process, encompassing the transcription of young people’s discourses about the images and a cross-analysis with the observation notes on the activist interventions undertaken by the young people.

Drawing from the community profile method (Arcidiacono et al., 2001; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012), the five teams had the autonomy to select their topics and data collection methods. Table 2 depicts these choices.

Once the topics were chosen and the teams initiated the data collection process, they were surprised by their lack of knowledge regarding issues they nevertheless felt were relevant, as well as by the lack of awareness within the school community. For example, the teams that chose the topic of bullying were unaware of the different types of bullying, and several people at their school were unable to recognize bullying situations. These observations shaped the young people’s primary objective in their activist interventions: know more about the problems and raise community awareness about the seriousness of them. Most of the activist initiatives undertaken by the young people predominantly used visual tools and formats of claim-making. These processes will be detailed next.

The five teams developed different activist initiatives – Table 3 presents a brief description of all of them. In this section, we will discuss three activist actions as illustrative examples of the emphasis on visual, performative, and digital forms of participation.

After a negotiation process, the “Equality Squad” team identified the problem of gender inequality as the focus of their activist intervention. After researching and interviewing colleagues in their school community (7th and 9th-grade students), they realized it was crucial to raise awareness of the problem of gender inequality in sports. They decided to produce a short video for social media where they recreated a football match: in this performance, a girl was constantly left out of the game. Then, a protest began and the protestors invaded the match (Figure 2). The following observation excerpt accounts for the moment when the group was brainstorming about how to make an impact in their school community:

João1 asked, “Why do not we invade a football stadium? I’d really like to do it, and it’s possible.” They also considered making videos of people being interviewed about gender inequality in sports and then posting those videos on social media. They also talked about organizing a protest outside the school to get lots of people to take part and also making a video about it. When I reminded the students about the project’s link to sports contexts, they immediately connected it with several of their ideas. “Why do not we record a simulation of a football match here at school and, in the middle of that football match, we invade the pitch holding a protest? Then, we post the video on social media. We create a social media account or a page and publicize it.” (Observation note, March 22nd, 2023)

Figure 2. Video record of the protest in the middle of the football match warning about gender inequality in sport. The protest posters exhibit the following message: “equality”.

A sense of rebellion comes through this illustration, in which the young people engaged in a performative act of invading a football pitch, experimenting radical and disobedient forms of protest. This example suggests the young participants’ perception of this type of activism as potentially more impactful. For this group, the only way to feel heard and make the impact they desired would be through a non-legal form of activism (Malafaia et al., 2024; Ekman and Amnå, 2012), leveraging the media coverage of football to reach a wider audience. To bring this idea to life and make an impact on their school community, they simulated a game and performed concrete examples of gender discrimination during a match that would justify a non-normative mode of dissent. They then shared the video with the community through social media.

The excerpt above reveals how the ideas and thoughts of young people ended up, one way or another, revolving around visual and digital forms of protesting. This emphasis on visuality aligns with contemporary activist practices and the notion of “image events” discussed by Delicath and DeLuca (2003). It is also evident the role of social media in civic and political action (Malafaia et al., 2024; Kharroub and Bas, 2016) and how new devices, such as smartphones, have transformed the use and production of images for activist purposes (Doerr et al., 2013; Luhtakallio and Meriluoto, 2022). Our data show that these trends are not exclusive to established and organized social movements. Rather, they emerged throughout the processes of becoming activists, including among very young actors.

The “Stoppers” team unanimously decided to tackle the issue of bullying because it is a problem that has directly affected everyone on the team. When they interviewed friends and colleagues, they realized that there is a great deal of misinformation on the subject and that there is little concern on the part of schools, teachers, coaches, and local authorities. Based on their personal experiences and the information they gathered, these young athletes identified the locker rooms as places where “there is a lot of bullying.” Consequently, the team decided to produce around 60 anti-bullying armbands and make them available at an international tournament where any athlete could join their cause. At the entrance to the pitch, there was a big banner with the message “Sport without bullying. If you are against bullying, take your armband” (Figure 3) and a box with the armbands underneath. The armbands were white and contained a word written in red. The colours were chosen to highlight the words “Help,” “Stop,” and “Fight”.

Figure 3. The banner displayed at the pitch entrance and the anti-bullying armbands worn at an international rugby tournament.

The following observation note shows a moment when the researcher attending the rugby match interacted with the opposing team players. This was an insightful moment on the initiative’s impact on other young people and how visuals can effectively communicate the message.

I was taking some photos and asked an athlete from a Spanish team if I could take a photo of her armband. She said yes, and a teammate asked her, in Spanish, why so many people were wearing that armband. She told her colleague that it was an anti-bullying armband and explained that it was produced by one of the teams to raise awareness for the problem. I was happy because I realized that the message had gotten through, and those who were wearing the armband knew why they were wearing it. That was exactly what the initiative intended: to make people notice something different was happening and question themselves, thus bringing the problem to the table and talking about it to others. (Observation note, April 29th, 2023).

The observation note depicts the success of the armbands’ initiative from an external point of view. This consubstantiates what literature has been pointing out concerning how visual strategies can effectively enhance the quality of the message conveyed, but also in mobilizing young people and drawing attention to social problems (Catanzaro and Collin, 2023; Powell et al., 2015).

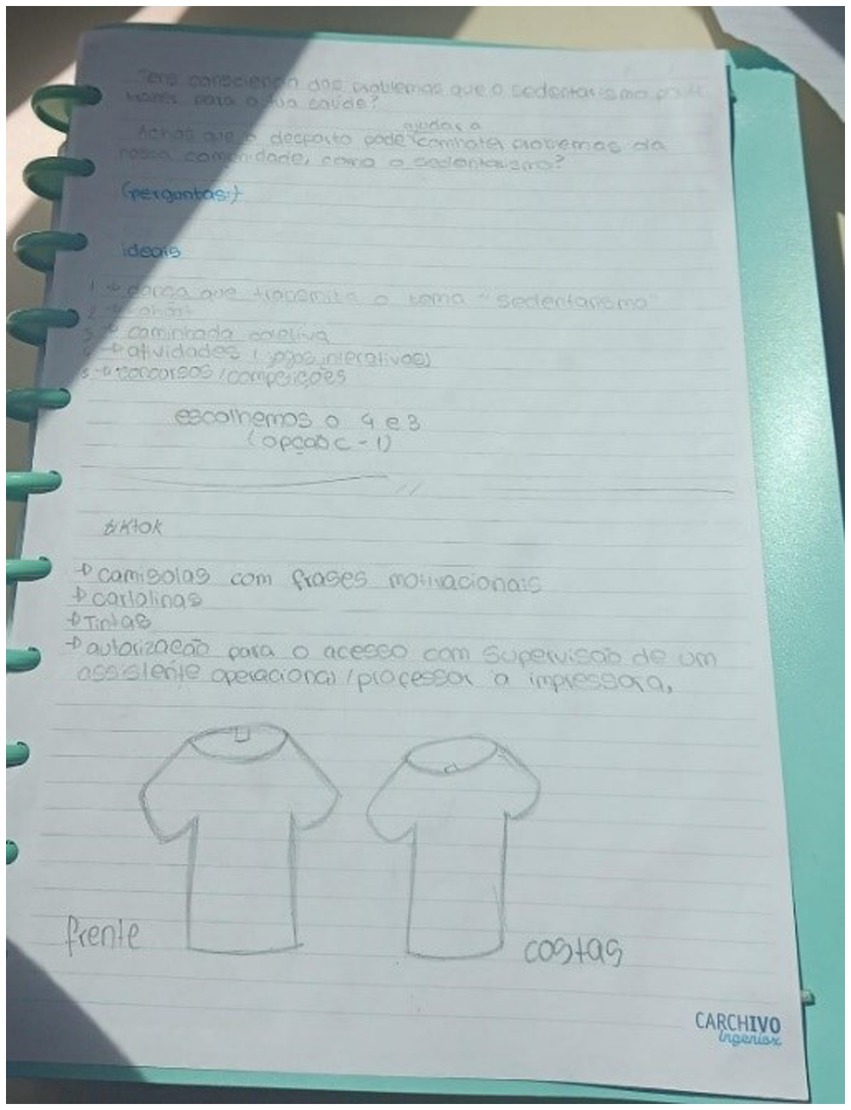

The “Nutrivida” team decided to work on the problem of sedentary lifestyles. In their questionnaires to the 7th and 9th classes at their school, they realized that a large part of the community is sedentary and that many students did not even know what a sedentary lifestyle means. It, therefore, became clear to the team that they wanted to focus their intervention on this target group. Although the team thought it would be a contradiction to use social media to communicate their message, since the message encouraged a reduction in screen time and more sports practice, the team decided to go ahead because the aim was to reach as many young people as possible. Based on this premise, the young participants produced a dance video for TikTok, considering that this social media algorithm tends to favour dance videos. The choreography began with some members in a nested, inactive-like bodily position, then becoming lively and active after being touched (woken up) by the other dancers. The team also decided to wear white T-shirts while dancing, with messages on the T-shirts’ backs, chosen by the members – e.g., “Practise sport, your body and mind will thank you” see Figure 4. The following excerpt describes how the young people came up with the idea.

The team initially thought of making a rap. When I asked them why, they said it was a good way to communicate a message. While talking about rap and justifying the idea, some members were dancing (a famous TikTok choreography, I believe). At that point, I asked about the connection to sport. As soon as I asked the question, the students thought of performing a TikTok dance as a way to warn people about sedentary lifestyles. Once they’d said it out loud, they started thinking about possible choreographic moves and styles. (Observation note, March 22nd, 2023).

In this initiative, it is possible to see how visual elements played a central role, once again, in the strategies developed by young people and how social media seem to be their first choice when it comes to influencing others and communicating messages (Kharroub and Bas, 2016; Luhtakallio and Meriluoto, 2022). These decisions, anchored in the young people’s everyday experiences, resonate with studies that indicate: (i) the young people’s preference for using digital-visual tools to interact with their peers and the general public (Casas and Williams, 2019; Catanzaro and Collin, 2023); (ii) and the importance that the use and production of images assume among young people when they try to instigate the interest on societal topics (Marques et al., 2020; Ugwuanyi et al., 2019).

At the end of the project, and after realizing the predominance of visual modes of action and expression among young participants, we asked them to bring an image (a picture taken either by themselves or by others) that would represent their engagement in the project. Following the connection to sports of the participating groups, the images were presented alongside a slogan. At the last working session, the images were displayed and presented. At school, considering the size of the group and the time available for the session, the young pupils/athletes did this task in pairs. At the rugby club, it was an individual task. Table 4 synthesizes the visual representations of the young participants, considering the types of visuality and the dimensions of their engagement in the project that they have chosen to highlight.

As shown, and perhaps counterintuitively, most images do not directly relate to the activist interventions or the phases of identifying and collecting data on the community problems. The images the young participants chose to represent their engagement in the project were mainly related to the team-working process that preceded the activist events – e.g., moments of collective planning, negotiating with adult actors, or designing feasible and concrete actions. Based on this, we will next present and discuss four illustrative examples.

In the image Maria and Teresa chose (Figure 5), the girls have taken a photo of a notebook’s page. On that page, we see some loose ideas written down and a prototype of the T-shirts that the Nutrivida team wore while performing their choreography. This is the image that, for these young athletes, best represents their participation in this project.

Figure 5. Maria and Teresa’s picture was presented alongside the slogan “deciding together to achieve a goal”.

As explained by Maria and Teresa, the image crystallizes the process of “deciding together to achieve a goal” because they considered that “without being able to come up with these ideas and these threads of ideas, we could not get to where we are. We first had to reach a consensus.”

Reflecting on the reason for choosing the image and its slogan, the young girls recognized the importance of developing ideas, collectively negotiating them, and systematically organizing them. These are aspects reflected in the notebook’s photograph. While becoming activists, the group learned how demanding it is to plan a successful activist action, which depends on collective decision-making – “deciding together” – and requires a processual and patient unfolding – “ideas and threads of ideas.” This also demonstrates the potential of YPAR methodological approaches to involve participants in empowering and action-orientated learning experiences (Buttimer, 2019; Warren and Marciano, 2018).

The following image, chosen by Lucas and Manuel (Figure 6), is an edited photograph that the students took of the school playing field and artificially transformed into a paired image to provide a clear contrast. On the left side of the image, the young participants try to represent a day with adverse weather conditions, which are dark and stormy. On the right, the same playing field is portrayed with light colours, representing a sunny day (see Figures 7, 8).

Figure 6. Example provided by members of the “Contra-bullying” team. Lucas and Manuel’s picture was presented alongside the slogan “the easy and difficult side of work”.

Figure 7. Example provided by Joana, a member of the “Stoppers” team. Joana’s picture was presented alongside the slogan “never get discouraged until you reach the end and see the result of your work”.

Figure 8. Example provided by Sofia, a member of the “Stoppers” team. Sofia’s picture was presented alongside the slogan “Together we are stronger, join us and make a difference”.

According to Lucas and Manuel, they chose the football pitch because.

(…) we are working on sports here. And we chose these two atmospheric conditions because the thunderstorm side is when we felt the difficult part of the work, when we had no more ideas and when we thought everything was lost… and then the sunny part is when we start to finish the work and see the light at the end of the tunnel.

This is a good example of how young people use images to convey emotions (Casas and Williams, 2019; Catanzaro and Collin, 2023; Powell et al., 2015). By looking at the image of Lucas and Manuel, we can perfectly understand how emotionally challenging the engagement in the project was for them. Through the image, they communicate the difficulties they experienced, the “thunderstorm days,” and simultaneously, the personal fulfilment that comes from overcoming those difficulties, “the sunny days.” Interestingly, they see both dimensions as part and parcel of the process, as two sides of the same coin. The “light at the end of the tunnel” when they finally pull together their activist intervention suggests the positive impact that YPAR projects can have on the sense of agency and effectiveness perceived in affecting community change (Buttimer, 2019; Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Marques et al., 2020).

The next image, chosen by Joana, represents the culmination of a challenging endeavour, which had moments of discouragement and uncertainty but paid off in the end. Several people adhered to the activist initiative, represented by the image.

This photograph, one of the few that portrays the activist action, shows athletes wearing the anti-bullying armbands produced by the young participants of the “Stoppers” team. The highlight is on the potential of visual productions, such as the armbands, in mobilizing others (Casas and Williams, 2019; Catanzaro and Collin, 2023; Powell et al., 2015) and in acting as disruptive and out-of-ordinary elements that enhance the spectators’ engagement in questioning the social phenomenon that is at stake (Malafaia et al., 2024).

As Joana explained, the beginning of the development of the activist action was quite discouraging “because the school principals did not reply to the emails” – initially, the young participants wanted to carry out their initiative in the school. The intention was to ask the school principals for authorization to collect some data with students through interviews and questionnaires and then develop their activist initiative. Still, after demotivating moments, due to the lack of responses, they “realized that [there were] other ways of interacting with the community, so the armbands were created and (…) in the end a lot of people joined, and we had a huge success.” This experience of developing alternative pathways to perform an activist action reveals two important aspects. On the one hand, the role that the school ethos should play – but often falls short – in supporting students’ citizenship practices (Dias, and Menezes, 2013). On the other hand, the importance of participatory projects as platforms that provide room for the young participants creative autonomy as political actors when engaged with topics that carry personal relevance for them (Dias, and Menezes, 2013; Arcidiacono et al., 2001; Marques et al., 2020; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012). Furthermore, it is interesting to note how the experience of co-creation seemed to transform the engagement of young people who, for some reason, were initially at the periphery of the process. This is Sofia’s case (pictured below). The growing attribution of meaning to what the group was developing led Sofia to consider that: “this team, by opening the eyes of other teams, will make a big difference. So, all this was just us opening other people’s eyes, and that’s a marvelous thing”.

In the beginning, Sofia was passive, showing herself as somewhat of a disbeliever about the possibility of intervening in the community. Throughout the project, she became progressively involved in the activities, and, in the end, she grew as an enthusiast, permanently seeking to mobilize other young people. Indeed, methodological approaches, such as community profiling and participatory action research, can hold great value to foment young people’s empowerment and a sense of belonging, as well as individual and collective political efficacy (Buttimer, 2019; Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Marques et al., 2020). This article suggests that these processes can be enhanced and researched more heuristically if visual methods are incorporated into participatory approaches.

This article is anchored on two major dimensions pointed out by the literature in this field of young people’s participation: the citizenship expressions and practices beyond conventional and institutional politics (Ribeiro et al., 2017; Malafaia et al., 2021; Ekman and Amnå, 2012) and the conditions that foster citizenship in connection to young people’s real experiences and interests (Buttimer, 2019; Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Menezes and Ferreira, 2012). Hence, we argue and demonstrate that young people’s citizenship can be examined from a dual perspective: first, by exploring how they adopt visual and online forms of activism within participatory research efforts, and second, by examining how visual practices aid in understanding the meanings that young people attribute to these participatory processes.

Throughout the development of the participatory research project with young people with no previous experiences in activism, one of the notable aspects that emerged was the preference for visuality-based forms and tools of activism by all participants. Young people spontaneously adopted visual modes of participation, which was not anticipated in the project nor did it result in any visual-oriented task (unlike what happens with methods like photovoice). While this is in line with the research on the role of visual and digital forms of action on contemporary political engagement (Luhtakallio et al., 2024; Doerr et al., 2013; Luhtakallio and Meriluoto, 2022), our article shows that such a role may well be a defining feature of young people’s current modes of political participation, not exclusive to established social movements and borne-out activists.

As portrayed in the observation notes, when collectively planning the activists’ actions, the choices and negotiations revolved around which type of visual-digital action to develop. This preference for visuals is backed up by other research studies that show young people’s use of online visuals to create political impact, express their views, and enhance the public visibility of their causes (Casas and Williams, 2019; Ugwuanyi et al., 2019; Malafaia and Meriluoto, 2022). Our article reinforces the fundamental role that images, visual resources, and online sharing play in acting, protesting, and articulating concerns (Malafaia et al., 2024; Delicath and DeLuca, 2003; Kharroub and Bas, 2016), as well as in mobilizing and engaging different audiences (Catanzaro and Collin, 2023; Powell et al., 2015).

Although the scholarly work on the role of online visuality in activism has been growing (Luhtakallio et al., 2024; Kharroub and Bas, 2016; Meriluoto, 2023), and pleas for participatory research projects with young people have been intensifying (Pais et al., 2014; Cutter-Mackenzie and Rousell, 2019; Rios et al., 2022), these arenas seldom converge. Photovoice, a research method that is both visual and participatory, entails great benefits in processes that seek to grasp the real-life experiences of young people from their point of view (Greene et al., 2018; Lam and Trott, 2022). As detailed in our article, in the project’s final stage, we incorporated a photovoice-guided activity to explore the meanings that the young people ascribe to their experience of participation in the project. We discussed examples of online (videos, pictures) and offline (items, clothes, banners) visualities that emerged from young people’s process of growing as activists in their communities. Doing this enabled us to consider the transformations in how young people express their citizenship while remaining not only attentive to their choices but also open to accommodating their voices in the very project design; these features should be integral to participatory research processes. Thus, we emphasize that researchers should reconsider traditional methodologies when studying youth citizenship, exploring more adaptive, engaging and inclusive practices that reflect the transformations on how young people express themselves and relate to political and societal issues. Participatory research approaches need not only to recognize young people’s choices, but also adjust to the new forms of engagement that emerge throughout the participatory process. Our study provides insights for future researchers seeking to integrate young people’s voices and actions more organically, offering practical suggestions on how to incorporate active participation from the initial stages of the project design.

Additionally, since young people increasingly prefer visual elements, our data highlights the importance of including visuality in the moments of project evaluation. Even though not envisioned in the initial project design, we realized that constructing meaning about experiences in the project would come more naturally to the young participants if done through visual means. In this exercise, it was interesting to observe that only a few participants focused on the outcomes of their activist interventions. Instead, the majority favoured the process that led to those outcomes: the young people recognized the range of skills and knowledge they acquired at each phase, starting from pinpointing the community problem to participating in group discussions, combining efforts and making decisions. The value of teamwork and the ability to overcome difficulties were the most representative dimensions of the images shared by the young participants. The visual meaning-making data highlights the emphasis young people placed on the process itself and on what they learned throughout it. Their participation in sports was mentioned less frequently. In fact, as shown in some empirical excerpts, they sometimes had to be reminded that their activist interventions were expected to be connected to sports in some way. As we discuss elsewhere (Dias et al., forthcoming), while young athletes may be predisposed to collective mobilization, this does not seem to result in the acquisition of skills or greater participation in their communities. Indeed, the young athletes attribute their acquisition of civic and political skills to the participatory process. This points to the transformative power of YPAR for promoting active citizenship practices, critical awareness, and a sense of agency among young people (Buttimer, 2019; Cammarota and Fine, 2008; Lam and Trott, 2022) when they have the opportunity to meet their concerns and needs (Menezes and Ferreira, 2012).

The data also leads us to reflect on the role of facilitators in implementing participatory methodologies: guidance and support need to be balanced with room to deal autonomously with obstacles and challenges. While facilitators’ interventions should not dictate the choices and actions of young people, it is important for them to step in when necessary and effectively manage the group, addressing the various challenges that inevitably and repeatedly arise. One of the key principles in facilitating these processes is to always keep the participants’ original ideas in mind, as these ideas often just need a different framing or presentation to come to life with slight adjustments. That said, several skills, such as flexibility and mediation, are essential for the effective implementation of participatory research projects and do not come naturally. Therefore, we emphasize the importance of including specific training programs for facilitators to enhance the development and implementation of participatory research. These programs may take the form of mentorship, supervision, or lectures on the core principles of YPAR by senior and more experienced researchers, as was the case in our project.

This study hopefully paves the way for future research and initiatives to empower young people to become active and informed citizens in an increasingly visual and interconnected world. Participatory methodologies instigate them to unite around a shared objective, encouraging them to devise solutions in the face of challenges that emerge from both internal group dynamics and external community obstacles. YPAR adds another layer by emphasizing the importance of adopting others’ perspectives, highlighting the value of young people relying not only on their own ideas but also understanding the perspectives of their peers and other members of their communities. These conclusions suggest a paradigm shift in young people’s engagement towards more visual and participatory forms of expression, underlining the need for research and community projects to adapt to these evolving preferences and practices.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

DV: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Investigation. TD: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Project administration. MS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. SP: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. NR: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. CN: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. CM: Formal analysis, Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was co-funded by the European Union through the European Social Fund and national funds through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, IP (FCT) under the multiannual funding awarded to CIIE [grants no. UIDB/00167/2020 and UIDP/00167/2020]. T. Silva Dias acknowledges FCT funding for her contract, established under the Scientific Employment Stimulus Individual Programme (DOI: 10.54499/2020.02610.CEECIND/CP1618/CT0002). M. Sampaio acknowledges FCT funding for her contract, established under the Scientific Employment Stimulus Individual Programme (DOI: 10.54499/2020.04271.CEECIND/CP1618/CT0003). N. Ribeiro acknowledges FCT funding for his contract, established under the Scientific Employment Stimulus Individual Programme (DOI: 10.54499/CEECIND/02115/2018/CP1544/CT0003). C. Nada acknowledges FCT funding for his contract, established under the Scientific Employment Stimulus Individual Programme (DOI: 10.54499/CEECIND/02115/2018/CP1544/CT0003). C. Malafaia acknowledges FCT funding for her contract, established under the Scientific Employment Stimulus Institutional Programme (DOI: 10.54499/CEECINST/00134/2021/CP2786/CT0002).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^All the names are fictional to preserve the young people’s anonymity and confidentiality.

Arcidiacono, C., Sommantico, M., and Procentese, F. (2001). Neapolitan Youth’s sense of community and the problem of unemployment. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 11, 465–473. doi: 10.1002/casp.646

Buttimer, C. J. (2019). The challenges and possibilities of youth participatory action research for teachers and students in public school classrooms. Berkeley Rev. Educ. 8, 39–81. doi: 10.5070/B88133830

Bessant, J. (2020). From denizen to citizen: contesting representations of young people and the voting age. JAYS 3, 223–240. doi: 10.1007/s43151-020-00014-4

Cammarota, J., and Fine, M. (2008). “Youth participatory action research: a pedagogy for transformational resistance” in Revolutionizing education: Youth participatory action research in motion. eds. J. Cammarota and M. Fine (New York: Routledge), 1–11.

Casas, A., and Williams, N. W. (2019). Images that matter: online protests and the mobilizing role of pictures. Polit. Res. Q. 72, 360–375. doi: 10.1177/1065912918786805

Catanzaro, M., and Collin, P. (2023). Kids communicating climate change: learning from the visual language of the SchoolStrike4Climate protests. Educ. Rev. 75, 9–32. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2021.1925875

Council of Europe (2015). Revised European charter on the participation of young people in local and regional life. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Available at: https://rm.coe.int/168071b4d6.

Cruz, J., Malafaia, C., Piedade, F., Silva, E., and Menezes, I. (2019). Promuovere la cittadinanza europea attiva dei giovani: Un intervento partecipativo sulla politicizzazione delle preoccupazioni sociali dei giovani [Promoting European active citizenship: A participatory intervention towards the politicisation of youth social concerns]. Psicologia Di Comunitá, 1, 69–89. doi: 10.3280/psc2019-001006

Cutter-Mackenzie, A., and Rousell, D. (2019). Education for what? Shaping the field of climate change education with children and young people as co-researchers. Child. Geograph. 17, 90–104. doi: 10.1080/14733285.2018.1467556

Delicath, J. W., and DeLuca, K. M. (2003). Image events, the public sphere, and argumentative practice: the case of radical environmental groups. Argumentation 17, 315–333. doi: 10.1023/A:1025179019397

Dias, T., and Menezes, I. (2013). The role of classroom experiences and school ethos in the development of children as political actors: Confronting the vision of pupils and teachers. Educ. Child Psychol. 30. 26–37. doi: 10.53841/bpsecp.2013.30.1.26

Dias, T. S., Vieira, D., Nada, C., Sampaio, M., Ribeiro, N., and Pais, S. C. (forthcoming). Young Athletes as sports activists: empowerment as a fundamental element of the process.

Doerr, N., Mattoni, A., and Teune, S. (2013). “Toward a visual analysis of social movements, conflict, and political mobilization” in Advances in the visual analysis of social movements. eds. N. Doerr, A. Mattoni, and S. Teune, vol. 35 (Leeds: Emerald), xi–xxvi.

Ekman, J., and Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: towards a new typology. Hum. Aff. 22, 283–300. doi: 10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1

Emme, M. J. (2001). Visuality in teaching and research: activist art education. Stud. Art Educ. 43, 57–74. doi: 10.2307/1320992

Eurydice (2005). Citizenship education at School in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Greene, S., Burke, K. J., and McKenna, M. K. (2018). A review of research connecting digital storytelling, Photovoice, and civic engagement. Rev. Educ. Res. 88, 844–878. doi: 10.3102/0034654318794134

Grover, S. (2011). Young People’s human rights and the politics of voting age. Switzerland: Springer.

Hellison, D., and Martinek, T. (2009). Youth leadership in sport and physical education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kharroub, T., and Bas, O. (2016). Social media and protests: an examination of twitter images of the 2011 Egyptian revolution. New Media Soc. 18, 1973–1992. doi: 10.1177/1461444815571914

Lam, S., and Trott, C. D. (2022). Children’s climate change meaning-making through photovoice. Educação, Sociedade & Culturas 62, 1–25. doi: 10.24840/esc.vi62.478

Lawy, R., and Biesta, G. (2006). Citizenship-as-practice: the educational implications of an inclusive and relational understanding of citizenship. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 54, 34–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00335.x

Luhtakallio, E., and Meriluoto, T. (2022). Snap-along ethnography: studying visual politicization in the social media age. Ethnography. doi: 10.1177/14661381221115800

Luhtakallio, E., Meriluoto, T., and Malafaia, C. (2024). Visual politicization and youth challenges to an unequal public sphere: Conceptual and methodological perspectives. In The Handbook on Youth Activism. ed. J. Conner (Edward: Elgar), pp. 140–153.

Malafaia, C., and Meriluoto, T. (2022). Making a deal with the devil? Portuguese and finnish activists’ everyday negotiations on the value of social media. Soc. Mov. Stud. 23, 190–206. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2022.2070737

Malafaia, C., and Fernandes-Jesus, M. (2024). Communication in Youth Climate Activism: Addressing Research Pitfalls and Centring Young People’s Voices. In Environmental Communication. eds. A. Carvalho and T. R. Peterson (De Gruyter Mouton), pp. 303–321.

Malafaia, C., Kettunen, J., and Luhtakallio, E. (2024). Visual bodies, ritualised performances: an offline-online analysis of Extinction Rebellion’s protests in Finland and Portugal. Visual Studies, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/1472586X.2023.2292620

Malafaia, C., Neves, T., and Menezes, I. (2021). The Gap Between Youth and Politics: Youngsters Outside the Regular School System Assessing the Conditions for Be(com)ing Political Subjects. Young, 29, 437–455. doi: 10.1177/1103308820987996

Marques, R. R., Malafaia, C., Faria, J. L., and Menezes, I. (2020). Using online tools in participatory research with adolescents to promote civic engagement and environmental mobilization: the WaterCircle (WC) project. Environ. Educ. Res. 26, 1043–1059. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2020.1776845

Marsh, D., O’Toole, T., and Jones, S. (2006). Young people and politics in the UK: Apathy or alienation? London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Mattoni, A., and Teune, S. (2014). Visions of protest. A media-historic perspective on images in social movements. Sociol. Compass 8, 876–887. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12173

Menezes, I., and Ferreira, P. (2012). Educação para a Cidadania Participatória em Sociedades em Transição: Uma Visão Europeia, Ibérica e Nacional das Políticas e Práticas da Educação para a Cidadania em Contexto Escolar (Participatory citizenship education in societies in transition: A European, Iberian and national view of citizenship education policies and practices in the school context). Porto: CIIE/FPCEUP.

Meriluoto, T. (2023). The self in selfies: conceptualizing the selfie-coordination of marginalized youth with sociology of engagements. Br. J. Sociol. 74, 638–656. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.13015

Norris, P. (2002). Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing political activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

OECD (2018). Engaging young people in open government: a communication guide : OECD Publishing Available at: https://www.oecd.org/mena/governance/Young-people-in-OG.pdf.

Pais, S. C., Rodrigues, M., and Menezes, I. (2014). Community as locus for health formal and non-formal education: the significance of ecological and collaborative research for promoting health literacy. Front. Public Health. 2:283. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00283

Potter, W. J., and Levine-Donnerstein, D. (1999). Rethinking validity and reliability in content analysis. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 27, 258–284. doi: 10.1080/00909889909365539

Powell, T. E., Boomgaarden, H. G., De Swert, K., and De Vreese, C. H. (2015). A clearer picture: the contribution of visuals and text to framing effects. J. Commun. 65, 997–1017. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12184

Ribeiro, N., Neves, T., and Menezes, I. (2017). An Organization of the Theoretical Perspectives in the Field of Civic and Political Participation: Contributions to Citizenship Education. J. Polit. Sci. Educ. 13, 426–446. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2017.1354765

Ribeiro, N., Malafaia, C., and Ferreira, T. (2023). Lowering the voting age to 16: Young people making a case for political education in fostering voting competencies. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice. 18, 327–243. doi: 10.1177/17461979221097072

Rios, C., Neilson, A. L., and Menezes, I. (2022). Vamos fazer-nos ouvir. Educação, Sociedade & Culturas 62, 1–26. doi: 10.24840/esc.vi62.195

Roman, M., Roșca, V., Cimpoeru, S., Prada, E. M., and Manafi, I. (2023). ‘A picture is worth a thousand words’: youth migration narratives in a photovoice. Societies 13:198. doi: 10.3390/soc13090198

Sandin, B., Josefsson, J., Hanson, K., and Balagopalan, S. (2023). The politics of Children’s rights and representation. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Torralba, F. (2017). El Deporte, Agente Configurador del Ethos. Educación Social: Revista d’Intervenció Socioeducativa 65, 13–29. doi: 10.34810/EducacioSocialn65id320428

Ugwuanyi, C. J., Olijo, I. I., and Celestine, G. V. (2019). Social media as tools for political views expressed in the visuals shared among social media users. Libr. Philos. Pract. 2595. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2595

UNICEF (2022). “Building pathways to empowerment: recommendations for promoting inclusive youth civic engagement” in East Asia and the Pacific regional office (EAPRO) (Bangkok: UNICEF). Available at: https://www.unicef.org/eap/media/11921/file

Vera Romero, L. A., Allende Hernández, J. J., and Villamizar de Camperos, Y. (2018). Photographs as a pedagogical tool to strengthen the Reading and writing competences. Kuntovoimistelun opas 10, 20–26. doi: 10.22335/rlct.v10i4.609

Warren, C. A., and Marciano, J. E. (2018). Activating student voice through youth participatory action research (YPAR): policy-making that strengthens urban education reform. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 31, 684–707. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2018.1478154

Keywords: youth participatory action research, visual activism, civic engagement, community profiling, political participation

Citation: Vieira D, Dias TS, Sampaio M, Pais SC, Ribeiro N, Nada C and Malafaia C (2024) Becoming activists: how young athletes use visual tools for civic action and meaning-making within participatory research. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1414795. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1414795

Received: 09 April 2024; Accepted: 07 November 2024;

Published: 09 December 2024.

Edited by:

Sharon Coen, University of Salford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Samantha A. Majic, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Vieira, Dias, Sampaio, Pais, Ribeiro, Nada and Malafaia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carla Malafaia, Y2FybGEubWFsYWZhaWFAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=; Y2FybGFtYWxhZmFpYUBmcGNlLnVwLnB0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.