- Departamento Académico de Psicología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Lima, Peru

This paper analyzes the relationships between the perception of legitimacy, institutional trust, and political moral laxity (PML) using “Proyecto Especial Legado” (LEGADO) as a case study. LEGADO is a public governance organization, created by the Government of Peru to manage the infrastructure and provide services derived from the organization of the Pan American and Parapan American Games “Lima 2019.” The results indicate a direct relationship between the perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment (as an indicator of legitimacy) and the positive approval of this organization (as an indicator of institutional trust). Conversely, PML negatively affects approval for LEGADO. However, this relationship is mitigated when the perception of objectives fulfillment is introduced as a mediating variable. Thus, although the effects are limited, a positive perception of objectives fulfillment may help reduce the adverse effects of PML on trust in LEGADO. To conduct this research, a correlational study was performed using data collected from a questionnaire administered to 404 citizens in the Lima Metropolitan Area, which addressed issues of legitimacy, institutional trust, and PML in relation to the public governance of the games and their legacy (through LEGADO). Finally, the implications of a governance legitimized by the fulfillment of institutional objectives are discussed, particularly regarding its impact on breaking the vicious cycle that links PML with institutional distrust.

Public management of sport mega-events and their social impacts

Sport mega-events are international gatherings of broad scope and repercussion, as well as of limited duration, which attract a large number of visitors and audiences through media. They entail considerable organizational costs and have diverse long-term impacts on the cities hosting them (Maennig and Zimbalist, 2012; Müller, 2015).

These events involve complex logistical organization processes that provide opportunities for host cities to revitalize urban spaces and boost economic and commercial activities, alongside increasing tourism (Lee Ludvigsen et al., 2022). However, these events also face opposition and criticism due to the significant economic costs they entail as well as their potential negative material and social impacts (Lee Ludvigsen et al., 2022; Müller, 2015).

To mitigate the negative impacts, and enhance positive ones, some of these sport mega-events come together with complementary projects aimed at managing the social, economic, cultural, and urban impacts that would be left as a legacy to the host cities. Specifically, these projects aim to improve urban public spaces, strengthen community sense, and promote health and well-being (Curi et al., 2011; Melhuish et al., 2022).

The main reference for those projects was the 1992 Summer Olympics hosted in Barcelona (García and Such, 2010). The legacy project of Barcelona 1992 proposed plans and objectives for the urban improvement of the city (Cerezuela, 2019). Subsequently, other cities such as London (2012 Olympics), Rio de Janeiro (2007 Pan American Games and 2016 Olympics), and Medellin (2010 South American Games) have attempted to replicate this governance model with varying levels of success (Curi et al., 2011; Fisas Fernández, 2013; Giraldo-Giraldo, 2019).

The Lima 2019 games and their legacy

The Pan American and Parapan American Games represent the most important sport mega-events in the Americas, bringing together a large number of athletes from various sports disciplines every 4 years (Organización Deportiva Panamericana, 2020). In 2019, the city of Lima hosted the XVIII Pan American Games and VI Parapan American Games, representing an investment of approximately US $1,200 million for Peru, of which nearly 70% was allocated to the construction or improvement of permanent sports infrastructure (Plan de Legado, 2020). An attendance of over 750,000 people and more than 400 million viewers through other media platforms was reached, setting a record audience for these competitions (Plan de Legado, 2020).

Following the end of the games, the Peruvian Government activated the “Proyecto Especial Legado Juegos Panamericanos y Parapanamericanos Lima 2019” (LEGADO) to ensure the maintenance and proper use of sports infrastructure and provide services of quality to citizenship, generating social value and well-being for them (D. S. No 007-2020-MTC, 2020; Plan de Legado, 2020). The main objectives of LEGADO were as follows: (1) fostering a sense of pride and belonging to the city among people from Lima, (2) fostering a culture of sports promotion, (3) providing quality public spaces, (4) offering recreational services of good quality and safe spaces for citizens, (5) reducing discrimination of any kind in sports facilities, (6) managing the infrastructure left by the games, (7) promoting the well-being and healthy development of citizens and, (8) ensuring that the investment made for the games continues to generate income and attracts new investments to the city (Plan de Legado, 2020). Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, LEGADO received, by government mandate, the task of providing logistical support for the vaccination process in the Lima Metropolitan Area (D. U. No 043-2021, 2021; Juegos Panamericanos y Parapanamericanos de Lima 2019, 2021).

Regarding its objectives, a qualitative study on the games and their consequences shows that both people living near the sports facilities and users of the services offered in these facilities, reported that, once the games finished, there was continuous maintenance of urban improvements as well as public services offered by LEGADO (Cueto et al., 2024). On the other hand, a study on the institutional performance of LEGADO found that the organization exhibits positive results, reflected in a wide offer of sports, health, and recreational services, oriented to promote citizens’ well-being. This performance is attributable to the high levels of organizational commitment and innovative capacity of the public servants working there (Vera Ruiz et al., 2023). Similarly, a qualitative study with volunteers from the Lima 2019 Games and LEGADO shows a positive view of the personal and collective impacts derived from participating in volunteer activities, which provided a sense of personal value driven by the social significance that these projects entail for the Peruvian society (Cueto et al., 2024).

Finally, a quantitative study shows that users of vaccination centers administered by LEGADO were highly satisfied with the management and care provided in its facilities (Espinosa et al., 2023). Thus, LEGADO would legitimize its existence by addressing problems observed in the city of Lima, an urban area characterized by high levels of inequality and a limited offer of quality public services for significant sectors of the population (Wiese et al., 2016). From the above, it can be understood that the citizens’ perception of LEGADO’s fulfillment of institutional objectives can be understood as an indicator of legitimacy, should be associated with the approval of its creation and existence. This approval serves as an indicator of institutional trust, defined as the expectation regarding the functioning of institutions, to the extent that they adhere to principles of justice, equity, transparency, and efficiency (Miller and Listhaug, 1990).

Psychosocial aspects associated with legitimacy and institutional trust in Lima

In Peru, the widespread perception of institutional inefficiency and a system that prioritizes economic growth over social welfare (Vergara, 2020) have resulted in only 13% of Peruvians expressing trust in public institutions (Latinobarómetro, 2018). This leads to a lack of interest in public affairs, weakening the exercise of citizenship (Chaparro, 2018). Consequently, there is a significant lack of legitimacy in public institutions and a broad tolerance toward normative transgression by both citizens and authorities (Janos et al., 2018).

It is crucial to clarify that this study focuses on a perspective of legitimacy, adopting Tyler’s (2006) proposition, in which legitimacy is defined as the property emanating from an authority and/or institution that leads individuals to voluntarily agree to abide by decisions and norms that arise from them, rather than doing so out of fear of reprisal. For institutions to achieve legitimacy, it is necessary that they act under principles of justice, transparency, efficiency, and efficacy (Tyler, 2006). Meanwhile, the lack of legitimacy would result in a scenario of political socialization characterized by a lack of interest in public affairs, selfish behaviors, and a greater willingness to transgress among citizens (Beramendi et al., 2020; Gächter and Schulz, 2016). The consequences of the lack of legitimacy observed in citizens would manifest in a phenomenon called political moral laxity (PML), defined as a set of attitudes and beliefs characterized by tolerance and acceptance, corrupt, and transgressive actions carried out by politicians or authorities, which benefit those who accept them but harm others as well as society (Espinosa et al., 2022). It has been found that PML is positively associated with the approval of public institutions that do not operate according to the principles on which legitimacy is based (see Espinosa et al., 2022). As an example, a high level of PML can lead people to give their support to institutions that promote and act against the welfare of society, such as the Peruvian Congress, which, in recent years, has enacted a series of laws in favor of illegal mining, organized crime, among others (Anaya, 2024).

Thus, as the evaluation of the performance of public organizations is associated with the level of trust and approval of them (Beramendi et al., 2016), the recognition of LEGADO’s good performance, supported by the fulfillment of its objectives and its approval, would be indicators of legitimacy and institutional trust, respectively. Considering the above, the objective of this study is to analyze the relationship between levels of PML and the approval level of LEGADO in the Lima Metropolitan Area, examining the mediating role of the perception of LEGADO objectives fulfillment as an indicator of legitimacy. As a hypothesis, it is expected that (1) as the perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment increases, its approval will increase; that (2) the higher the PML levels, the lower the approval level of LEGADO; and if so, that (3) the perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment will be able to mitigate the negative effect caused by PML on institutional approval.

Method

Participants and sampling

In total, 404 citizens from the Lima Metropolitan Area participated in this study. Their ages ranged from 18 to 61 years (M = 35.5, SD = 11.15). Out of all participants, 213 were women (52.7%) and 191 were men (47.3%).

The sample size estimation was based on the population of the Lima Metropolitan Area, according to the latest census conducted in Peru (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática, 2018). However, it is not a representative sample in terms of randomization, but it is sufficiently heterogeneous, considering the population distribution associated with the Lima Metropolitan Area. Thus, a panel sampling was used. The characteristics that were considered in order to gather the sample were age, gender, socioeconomic level, and district of residence. Additionally, the participants voluntarily engaged in the study without any monetary payment (the distribution of these characteristics can be found in Appendix A).

Procedure

The survey consisted of a 15-minute questionnaire virtually administered by a specialized company hired for this purpose. All the procedures during the research complied with the ethical standards and informed consent established by the Ethics Committee for Research in Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (071-2021-CEI-CCSSHHyAA/PUCP).

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corp, 2017) software was employed for descriptive, correlational, and mediation statistical analyses. For the latter, the “Hayes Process Macro - Model 4” was used (Hayes, 2022). Additionally, an exploratory factor analysis with fit indicators was performed using the statistical program known as “JASP” (JASP Team, 2024).

Measurement

Sociodemographic data

The participants were presented with a sociodemographic form in order to collect information on their age, gender, educational level, and socioeconomic status.

Self-reported level of knowledge of LEGADO

This item aimed to assess the participants’ level of knowledge regarding the work carried out by LEGADO. To measure this, the following sentence was posed: “What level of knowledge do you have about the tasks performed by LEGADO.” The participants answered on a Likert-type scale from 1 to 6, where 1 = “None,” 2 = “Very little,” 3 = “A little,” 4 = “Fair,” 5 = “Quite a bit,” and 6 = “A lot.” Furthermore, regardless of the participants’ level of knowledge, a semantic aid consisting of general information about Lima 2019 Games and LEGADO was presented to participants to ensure that they were able to continue answering the questionnaire. The complete semantic aid can be found in Appendix B.

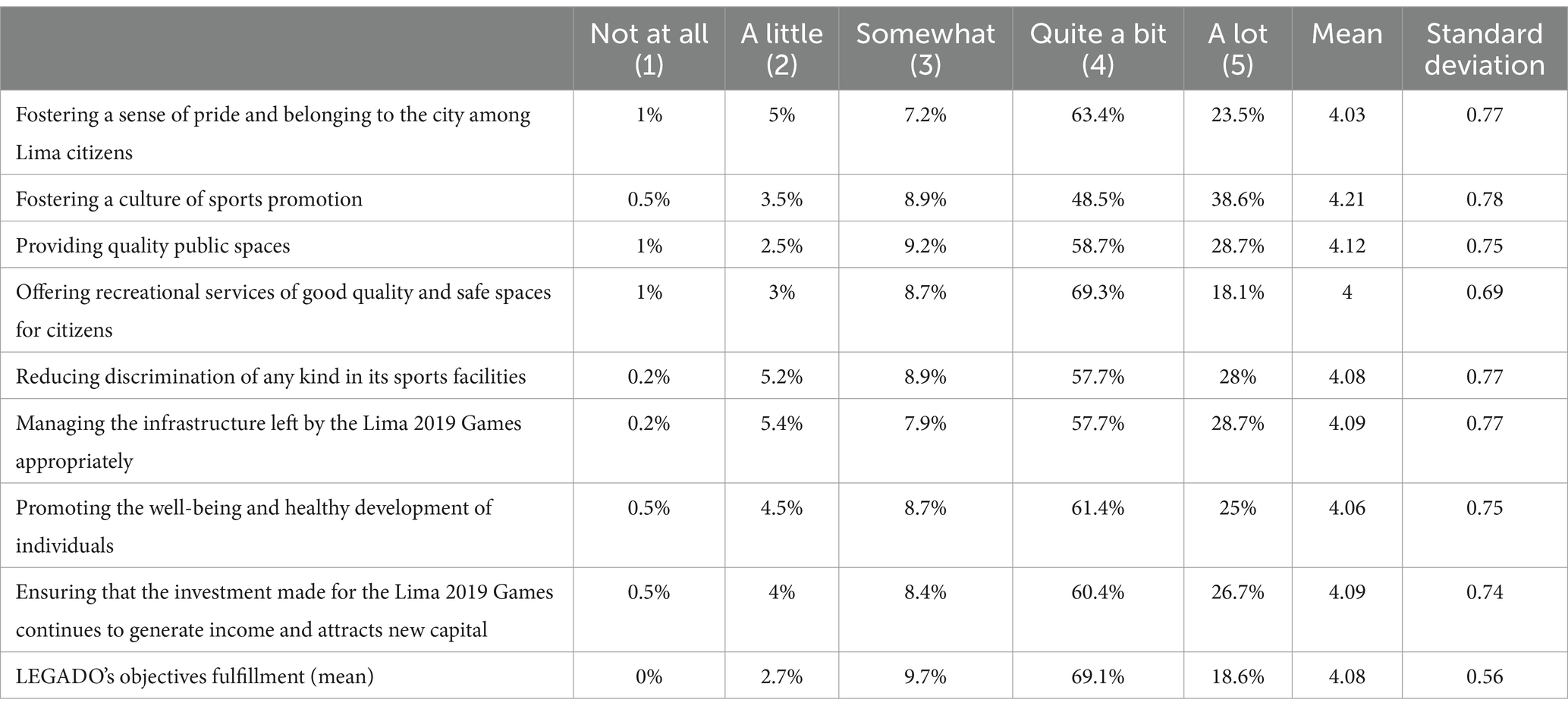

Perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment (legitimacy indicator)

Eight items to assess the fulfillment of LEGADO’s objectives were used, with the following statements: “Do you believe that LEGADO is”: (1) fostering a sense of pride and belonging to the city among people from Lima, (2) fostering a culture of sports promotion, (3) providing quality public spaces, (4) offering recreational services of good quality and safe spaces for citizens, (5) reducing discrimination of any kind in its sports facilities, (6) managing the infrastructure left by the Lima 2019 Games appropriately, (7) promoting the well-being and healthy development of individuals, and (8) ensuring that the investment made for the Lima 2019 Games continues to generate income and attracts new capital. The response scale ranged from 1 to 5, where 1 = “Not at all,” 2 = “A little,” 3 = “Somewhat,” 4 = “Quite a bit,” and 5 = “A lot.”

An exploratory factor analysis using a maximum likelihood verified that these eight items grouped into a single general dimension, as indicated by the scree plot (KMO = 0.88, χ2(28) = 1419.02, p < 0.001). The dimension, “objectives fulfillment,” had an eigenvalue of 4.44, explaining 55.5% of the variance. When evaluating the possibility of the presence of more components, the next eigenvalue reached only 0.81, which is insufficient to justify additional dimensions. The analysis also showed a good level of internal consistency (α = 0.88) and the following fit indices: (TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.10, 90% CI [0.09, 0.12]). Although the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value obtained from the model is high compared to usual standards, approaching the threshold for acceptability, it just remains within a range that supports the usability of the model (Browne and Cudeck, 1993).

To further elaborate on the aforementioned, while an RMSEA below 0.06 (or, more leniently, below 0.08) is often regarded as an indicator of “good” (or “acceptable”) model fit, it is imperative not to adhere strictly to these thresholds. Such criteria are frequently unattainable for complex, multi-factor rating instruments at the item level. Therefore, it is advisable to evaluate model fit as part of an ongoing process, rather than relying solely on the obtained values (Vignoles et al., 2016). This perspective is supported by the literature (Levine et al., 2003; Vignoles et al., 2016).

Level of approval of LEGADO (institutional trust indicator)

This was an item that asked: “Regarding LEGADO, would you say that you approve of its creation?” with a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4, where 1 = “Completely disapprove,” 2 = “Somewhat disapprove,” 3 = “Somewhat approve,” and 4 = “Completely approve.”

Political moral laxity

The subscale of the same name, developed by Janos et al. (2018), was used. It consists of three items, adapted to the city of Lima: (1) In Lima, it is legitimate to choose those candidates who best respond to my personal interests, even if they are corrupt; (2) all Lima politicians are bad, so it is better to choose those who “steal but do work”; and (3) In Lima, it is valid to elect those candidates who respond to my own interests, even if they affect the interests of other citizens. It was presented on a 5-point Likert scale response, where 1 = “Completely disagree” and 5 = “Completely agree.” The internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.88).

Results

On a descriptive level, 3.7% of the participants expressed having no knowledge about LEGADO; 7.3%, very little; 9%, little; 43%, a moderate level of knowledge; 36.8%, quite; and 0.3%, a lot of knowledge about this organization.

Regarding legitimacy, there is a predominantly positive perception about the level of objectives fulfillment; the most highly valued objective was “providing quality public spaces” (93.6%), while “managing the infrastructure left by the Lima 2019 Games appropriately” was perceived to have the lowest level of fulfillment; however, it still garnered a high level of perception (88.6%). The variance falls within the two highest categories of the scale (“Agree” and “Strongly Agree”). Table 1 shows the distribution of the perception of objectives fulfillment.

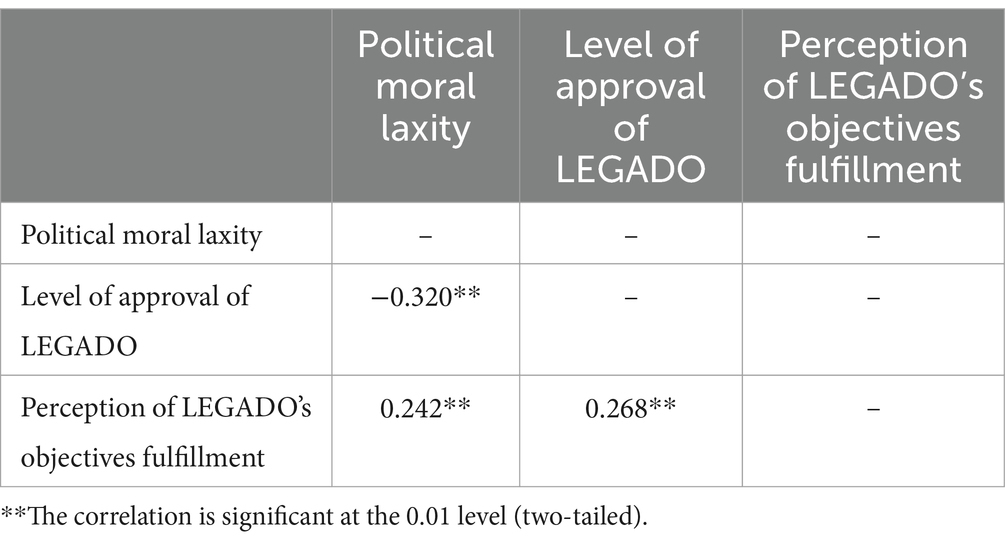

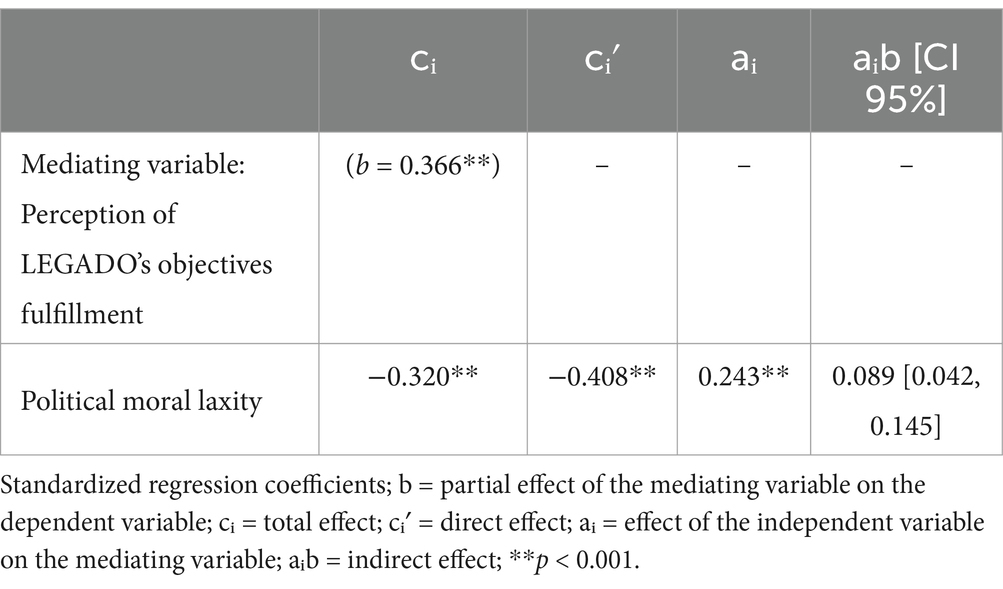

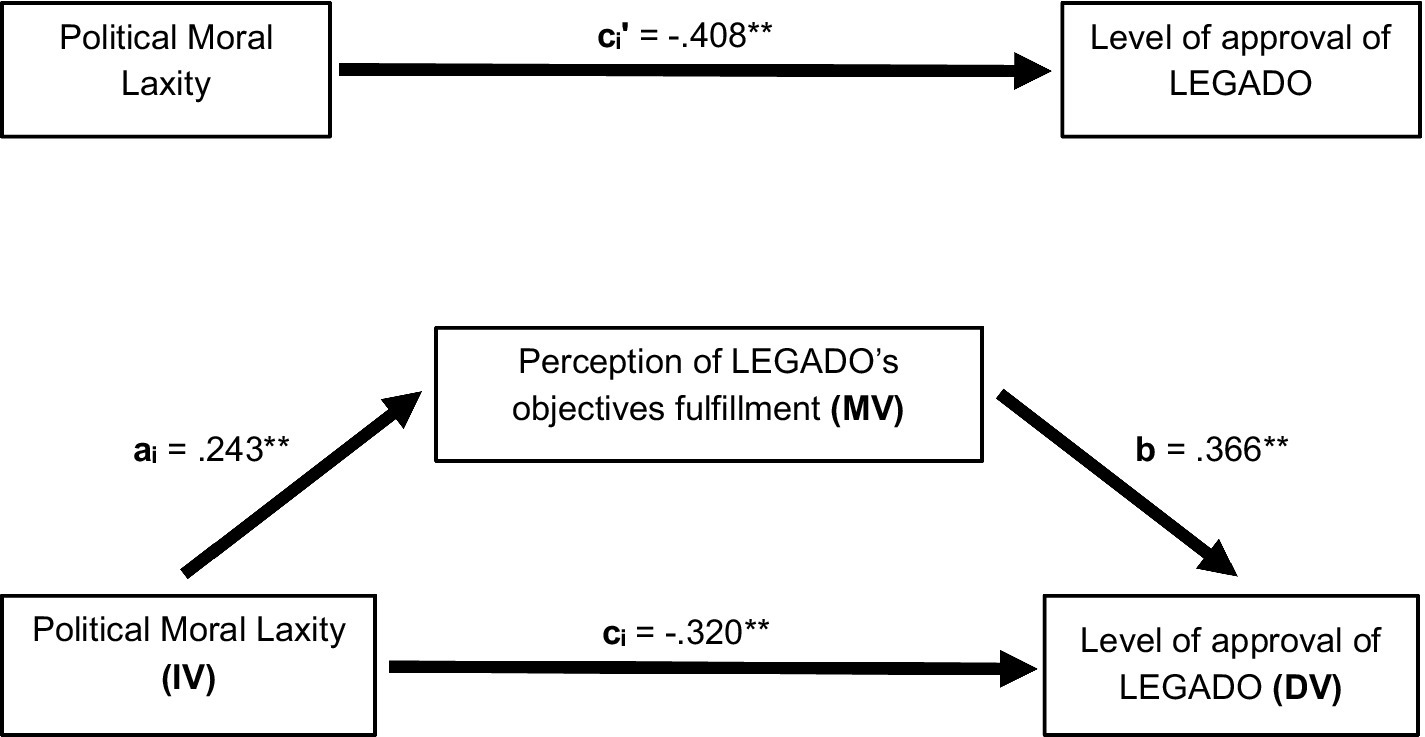

The correlational analysis (Table 2) shows a negative correlation between PML and the level of approval of LEGADO. When using the perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment as a mediating variable, the negative effect of PML on the approval of LEGADO is attenuated, indicating a suppression effect (cᵢ = −0.320) that reduces the original direct effect of PML on the level of approval of LEGADO (cᵢ′ = −0.408) (Table 3, Figure 1).

Table 2. Correlations between political moral laxity, level of approval of LEGADO, and perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment.

Table 3. Mediation role of the perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment in the relation between political moral laxity (IV) and level of approval of LEGADO (DV).

Figure 1. Mediation role of the Perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment in the relation between political moral laxity (IV) and level of approval of LEGADO (DV). Standardized regression coefficients; b = partial effect of the mediating variable on the dependent variable; cᵢ = total effect; cᵢ′ = direct effect; aᵢ = effect of the independent variable on the mediating variable; aᵢb = indirect effect; **p < 0.001.

Furthermore, a high level of approval for LEGADO was reported as an indicator of institutional trust (98.8%), whereas only 1.2% of the participants disapproved of the project. However, despite the overall high approval ratings, the responses on the scale revealed notable variation within the top two categories of approval (somewhat approve and completely approve).

Similarly, the negative correlation between PML and the level of approval of LEGADO is of particular significance, being the highest value among all found.

Discussion

Regarding the general objective of the study, the results show that there is a correlation between the perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment and its approval, which highlights the existence of a positive relationship between legitimacy and institutional trust. This relationship suggests that even with the limitations that such a small public organization like LEGADO faces, as long as there is good governance that is visible to the public in terms of justice, equity, transparency and efficiency, legitimacy toward the institution will be generated (see Tyler, 2006), reinforcing the approval of it (see Beramendi et al., 2016).

This leads us to discuss the second hypothesis of the study, which is that PML, seen as an endemic problem of political socialization in Peru, related to the negative perception of institutional functioning (Chaparro, 2018; Latinobarómetro, 2018), is negatively associated with the approval of LEGADO, which has shown good governance performance (Espinosa et al., 2023; Vera Ruiz et al., 2023; Cueto et al., 2024). However, according to the third and most significant hypothesis, which was corroborated by the findings, the perception of LEGADO’s objectives fulfillment, as an indicator of legitimacy, can help mitigate the negative effect caused by PML on institutional approval. In other words, just as the system “teaches” us to distrust institutions and to foster a more selfish outlook, less inclined to defend the public good (Espinosa et al., 2022), it is also possible to mitigate the negative effect of the PML—as a selfish way of engaging with the public—through an effective institutional functioning that legitimizes it (Gächter and Schulz, 2016). In this sense, although it is a great challenge to build a virtuous circle that promotes the construction of legitimacy, reinforces institutional trust institutional trust, and mitigates PML among citizens, public governance projects executed with transparency, honesty, and efficiency can contribute to this goal.

As an additional note, it is important to highlight that a higher level of PML leads to a higher perception of objectives fulfillment. It seems that, even when institutions function effectively, an individual with PML will oppose them, as they do not offer direct personal benefit. In other words, anything that promotes the development of democracy will be undermined, as it does not serve their immediate personal interests. This is evident in the governance of the Peruvian state, where rights and moral integrity are threatened by laws that undermine access to quality education and justice, enacted by the very representatives elected by the people, who act against citizens’ well-being (Ley N° 31520, 2022; Ley N° 32107, 2024).

All of this reinforces the need to protect institutions against the siege of selfish and private interests, promoting principles oriented toward the defense of the public good (see Vergara, 2020). Finally, the present study accounts for a limited but significant effect of the perception of legitimacy, based on indicators of institutional objectives fulfillment, on the approval of a public organization like LEGADO and on the mitigation of the effect of the PML on such approval. The above serves as an optimistic indication that consistent work aimed at institutional strengthening through positive governance, characterized by legitimacy principles should mitigate the negative aspects of PML in society.

As a closing remark, it is important to highlight that a significant limitation of this study is that using a theoretical framework like the one proposed by Tyler (2006) regarding legitimacy may be considered somewhat naive. As an example, while a person may perceive that the system functions in terms of procedural, distributive, and transitional justice, it is possible that the system does not, in reality, exhibit these qualities. In such a case, what would be experienced is the legitimization of the system, but not a truly legitimate system as such (Anaya, 2024).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Comité de Ética de la Investigación de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the questionnaire was applied virtually. The participants gave their consent after being presented with a informed consent form by pressing the correspondent option.

Author contributions

JM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AE: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Vicerrectorado de Investigación - Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, CAP PI7033.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1412477/full#supplementary-material

References

Anaya, R. (2024). Entre la Legitimidad y la Legitimación del Sistema Político Peruano: Estudios psicopolíticos sobre las creencias y actitudes constitutivas de la Legitimidad Política en un contexto de debilitamiento democrático : Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Beramendi, M., Delfino, G., and Zubieta, E. (2016). Confianza institucional y social: una relación insoslayable. Acta de Investigación Psicológica 6, 2286–2301. doi: 10.1016/S2007-4719(16)30050-3

Beramendi, M. R., Espinosa, A., and Acosta, Y. (2020). Percepción del Sistema Normativo y sus correlatos psicosociales en Argentina, Perú y Venezuela. Revista Colombiana de Psicología 29, 13–27. doi: 10.15446/.v29n1.75797

Browne, M., and Cudeck, R. (1993). “Alternative ways of assessing model fit” in Testing structural equation models. eds. K. Bollen and J. Long (Newbury Park, California, United States of America: Sage Publications), 136–162.

Cerezuela, B. (2019). “Barcelona 1992: la herencia de unos Juegos planteados como estrategia postolímpica” in El olimpismo en España: Una mirada histórica de los orígenes a la actualidad. eds. A. Pérez and J. López (Barcelona, Spain: Fundación Barcelona Olímpica), 163–192.

Chaparro, H. (2018). Afectos y desafectos: Las diversas subculturas políticas en Lima. Lima, Peru: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

Cueto, R. M., Ayma, L., Llanco, C., and Espinosa, A. (2024). Significados y efectos del voluntariado en los Juegos Panamericanos y Parapanamericanos Lima 2019 y el Proyecto Especial Legado. Revista de Psicología 42, 1061–1096. doi: 10.18800/psico.202402.014

Cueto, R., Llanco, C., Ayma, L., and Espinosa, A. (2024). Sentido de comunidad, ciudadanía y apropiación del espacio en tres distritos de Lima: el caso del Proyecto Especial Legado.

Curi, M., Knijnik, J., and Mascarenhas, G. (2011). The Pan American games in Rio de Janeiro 2007: consequences of a sport mega-event on a BRIC country. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 46, 140–156. doi: 10.1177/1012690210388461

D. S. No 007-2020-MTC. Que modifica el Decreto Supremo N° 002-2015-MINEDU, crean Proyecto Especial para la Preparación y Desarrollo de los XVIII Juegos Panamericanos del 2019, en el ámbito del Ministerio de Educación; en el marco de lo dispuesto por el Decreto de Urgencia N° 004–2020 (2020). Available at: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/533743/DS_007-2020-MTC.pdf?v=1582557482

D. U. No 043-2021. Que dicta medidas extraordinarias, en materia económica y financiera, que permitan incrementar la capacidad logística, monitoreo del proceso logístico y de soporte de la vacunación y la implementación de la plataforma digital para el padrón nacional de vacunación contra la COVID-19. (2021). Available at: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/dispositivo/NL/1948340-3

Espinosa, A., Çakal, H., Beramendi, M., and Molina, N. (2022). Political moral laxity as a symptom of system justification in Argentina, Colombia, and Peru. TPM: testing, psychometrics, methodology. Appl. Psychol. 29:53. doi: 10.4473/TPM29.1.4

Espinosa, A., Martí, J., Calderón-Prada, A., Ticliahuanca, M., Lobrano, J., and Carreon, N. (2023). Satisfaction with vaccination services and its relationship to emotional responses of service users in Lima. LEGADO's quality management model as a public solution to promote citizen emotional well-being during pandemic. Front. Public Health 11:1136312. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1136312

Fisas Fernández, J. (2013). Londres 2012: Un proyecto para la (re)GENERACIÓN de una ciudad global. [Master Thesis, Universidad de Barcelona] : Dipòsit Digital de la Universitat de Barcelona.

Gächter, S., and Schulz, J. F. (2016). Intrinsic honesty and the prevalence of rule violations across societies. Nature 531, 496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature17160

García, J., and Such, M. J. (2010). Influencia de los mega-eventos en la oferta alojativa de un destino: Los juegos olímpicos. Revista de Análisis Turístico. AECIT. 10, 45–55.

Giraldo-Giraldo, D. C. (2019). Los Juegos Suramericanos, Medellín 2010: efectos y transformaciones territoriales. Bitácora Urbano Territorial 29, 127–134. doi: 10.15446/bitacora.v29n3.70243

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York City, New York, United States of America: Guilford Publications.

IBM Corp (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 25.0). Armonk, New York, United States of America: IBM Corp.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. (2018). Resultados definitivos de los censos nacionales 2017 región lima xii de población, vii de vivienda y iii de comunidades indígenas. Available at: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1550/

Janos, E., Espinosa, A., and Pacheco, M. (2018). Bases Ideológicas de la Percepción del Sistema Normativo y el Cinismo Político en Adultos de Sectores Urbanos del Perú. Psykhe 27. doi: 10.7764/psykhe.27.1.1176

JASP Team (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.0) [Computer software]. Available at: https://jasp-stats.org/

Juegos Panamericanos y Parapanamericanos de Lima 2019. (2021). Legado Pilar institucional. Lima 2019 Juegos Panamericanos y Parapanamericanos. Available at: https://lima2019.pe/legado/institucional

Latinobarómetro. (2018). Informe 2018. Santiago, Chile: Corporación Latinobarómetro. Available at: https://www.latinobarometro.org/latdocs/INFORME_2018_LATINOBAROMETRO.pdf

Lee Ludvigsen, J. A., Rookwood, J., and Parnell, D. (2022). The sport mega-events of the 2020s: governance, impacts and controversies. Sport Soc. 25, 705–711. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2022.2026086

Levine, T. R., Bresnahan, M. J., Park, H. S., Lapinski, M. K., Wittenbaum, G. M., Shearman, S. M., et al. (2003). Self-construal scales lack validity. Hum. Commun. Res. 29, 210–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2003.tb00837.x

Ley N° 31520. Ley que restablece la autonomía y la institucionalidad de las universidades peruanas. (2022). Available at: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/dispositivo/NL/2088561-1

Ley N° 32107. Ley que precisa la aplicación y los alcances del delito de lesa humanidad y crímenes de guerra en la legislación peruana. (2024). Available at:https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/dispositivo/NL/2313835-1

Maennig, W., and Zimbalist, A. (2012). What is a mega sporting event? En W. Maennig and A. Zimbalist (Eds.), International handbook on the economics of mega sporting events. (pp. 9–13). Northampton, Massachusetts, United States of America: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Melhuish, E., Bernstock, P., Brownill, S., Davis, J., Minton, A., and Woodcraft, S. (2022). State of the legacy: Reviewing a decade of writing on the 'regeneration' promises of London. London, United Kingdom: UCL Urban Laboratory 2012.

Miller, A. H., and Listhaug, O. (1990). Political parties and confidence in government: a comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 20, 357–386. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400005883

Müller, M. (2015). The mega-event syndrome: why so much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about it. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 81, 6–17. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2015.1038292

Organización Deportiva Panamericana. (2020). Constitution of the Pan American sports organization. Available at: https://www.panamsports.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/PANAM-SPORTS-CONSTITUTION-2020.pdf

Plan de Legado. (2020). Proyecto Especial Legado Juegos Panamericanos y Parapanamericanos Lima 2019. Available at: https://procurement-notices.undp.org/view_file.cfm?doc_id=127303

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 57, 375–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190038

Vera Ruiz, A., Prialé, M. Á., Espinosa, A., and Guevara, L. (2023). “Comportamiento organizacional prosocial-productivo: el Proyecto Especial Legado y su respuesta ante la pandemia” in Experiencias y lecciones aprendidas en la lucha contra la COVID-19. eds. O. Manky, M. Á. Prialé, and P. Lavado (Lima, Peru: Fondo editorial Universidad del Pacífico), 201–226.

Vignoles, V. L., Owe, E., Becker, M., Smith, P. B., Easterbrook, M. J., Brown, R., et al. (2016). Beyond the ‘east–west’ dichotomy: global variation in cultural models of selfhood. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 145, 966–1000. doi: 10.1037/xge0000175

Keywords: institutional trust, public governance, political moral laxity, LEGADO Lima-2019, legitimacy, sport mega-events

Citation: Martí J, Cueto RM and Espinosa A (2025) Legitimacy, institutional trust, and political moral laxity: psychopolitical impact of the governance of the legacy of ‘Lima 2019’ games. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1412477. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1412477

Edited by:

Adrián Albala, University of Brasilia, BrazilReviewed by:

Andres Mendiburo-Seguel, Andres Bello University, ChileAlejandro Olivares, Major University, Chile

Copyright © 2025 Martí, Cueto and Espinosa. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Agustín Espinosa, YWd1c3Rpbi5lc3Bpbm9zYUBwdWNwLnBl

Jordi Martí

Jordi Martí Rosa María Cueto

Rosa María Cueto Agustín Espinosa

Agustín Espinosa