- Department of Media and Communication Studies, National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad, Pakistan

Increasingly media provides ample opportunities for the audiences to make media choices and form different levels of exposure along political lines. Predominately, Pakistan’s media is recognized as an irreplaceable tool in sparking change in the political landscape, forgoing national-regional identities, and bridging social gaps. Due to recent technological advancements citizens’ media usage brought changes in the political behavior of citizens regarding party choices and voting behavior. Such changes in the political behavior of citizens affect decision making which is influenced by social cleavage of education, gender, and age. However, contrary to similar historical changes, these advances have widened rather than narrowed societal cleavages. The objective of the paper is to explore the influence of social cleavage and media usage on political behavior of students and faculty in Pakistan specifically NUML university, Islamabad. This research explores how social cleavage and recent advances in digital media access changed the political behavior of faculty and students of NUML university. The paper employed survey-based research with a sample of 250 faculty members and students of NUML, Islamabad. According to results, it is concluded that social cleavage of education, age, and gender plays a vital role in transforming the political behavior of both faculty members and students. Likewise, persistent use of social media portrays positive political participation along with accountable voting behavior, whereby males are more active in participating in political activities as compared to females. The paper has policy implications for a one-dimensional media approach for ignoring solutions to political problems and understanding citizenship rights. Focused and well-defined policies are required to bring youth back to broadcasting media.

Introduction

Media an imperative mode of communication exhibits a considerable influence on various aspects of individual’s life; one of the most fundamental influence of media is on individual’s behavior of casting vote, their political affiliations and political ideologies (Glasford, 2008). Since the evolution of mass media, various researches have been conducted on the use of technological innovations and different media sources. Media addressed as the fourth pillar of the state by British Parliament member, Lord Macaulay, realize the need for this recognition when researchers started acknowledging the influence of media and its importance with existing government. Additionally, media outlets also support or oppose diverse political parties of a country depending on their covert agendas. Media has revolutionized political arena due to its interactive relationship with users, also the emergence of internet has unlocked new venues for future researchers concerning the use of traditional and online media sources in determining the political behavior of individuals. However, major battle being fought through centuries is with the minds of people and communication is one of the prime sources for retaining this power and domination over social change (Castells, 2007).

Political communication is another source of directing social change; also, it is considered as significant form of communication in the field of mass media studies. According to Denton and Woodward (1990), political communication is solely concerned with the distribution of public resources (revenues), official sanctions (penalties and rewards), and official authority (control and power). Political communication creates awareness and knowledge among citizens, of public affairs and the basic working of politics, government and parties. Hence, political communication is one of the influential factors for inducing a change in the political behavior of any society (Berelson et al., 1954). Media, whether traditional or online, has been a critical player in the dissemination of political messages. Media serves as a tool of communication comprising of newspapers, television, radio, and internet. It is collective communication outlet or tool that is assumed as a channelized way of disseminating information whether electoral and political reforms to its ultimate consumers. In the contemporary era of 21st century, world has witnessed several revolutions, consisting of high use of social media and advanced patterns of political communication.

Despite access to multiple media channels around the globe, political parties strategically opt a particular media platform to communicate their political ideologies and interests in the arena of politics. Blumler and Kavanagh (1999) mentioned three phases of political communication: first phase includes two decades after World War I when people had trust on political system. Second phase is the inception of Television as a powerful medium in 1960s when television became the key source of political communication. Third phase is the current phase of evolving media where ubiquity, profusion and promptness of media have deeply influenced political communication. In the 21st century various significant revolutions in communication technologies have transformed the media landscape. Hence, the world is in the 3rd phase of political communication where numerous media platforms are available to create political awareness among citizens. Citizens political behavior has evolved in the light of Pakistan’s current political landscape due to the emergence of new technologies and changing political trends. History demonstrates that military takeovers and succession rules dominate Pakistani politics, thus Pakistan always struggled to reach democratic stability.

Since independence, Pakistan has witnessed several martial coups or otherwise dynastic rule of political parties. Over the years, Pakistani government has been subjugated by either Sharifs of Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) or Bhuttos and Zardaris of Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) with backing from secondary parties such as Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM), Awami National Party (ANP) and religious party Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI). The nation has experienced changes in the socioeconomic sphere, and mainstream political parties gained dynastic control over the political sphere.

Pakistan has never seen as a truly democratic system because of the “Ancestral Governments” and “Dynastic-civil coercions”. However, there was a noticeable rise in voter turnout in Pakistan’s 2013 general elections. Political parties have embraced new media as a platform for their political campaigns due to the increased societal use of social media and the internet. General elections in 2013 were the first social media elections in Pakistan, with the dynastic political party (PML-N) gaining power and authority for a third time. In addition to this democratic victory, elections brought to light a new political leader Imran Khan, emerged as a non-dynastic political party. PTI hardly gained a seat in Pakistan’s Parliament in the past seventeen years, but a shift was noticeable when the party rose to second-highest representation in the Parliament and became the country’s third-largest political party. This shift may be attributed to contemporary media patterns that are evident in Pakistan’s political history (Ahmed and Skoric, 2014). Before the advent of new media technologies, media industry was always operated in a pressurized environment under direct and indirect influences. One of the key reasons for exerted pressure on Pakistani media was its ownership. The launch of media outlets in Pakistan after independence was a jingoistic project which constituted of eminent figures from political movement for an independent state or they had a part in the ownership structure of those media outlets (Mezzera and Sial, 2010). However, after the privatization of media in 2002 (Musharraf’s regime), Pakistani media industry became a commercial entity with corporate business interests.

Due to this paradigm shift in Pakistani media landscape, political influence of media became a challenging subject for researchers. Previously, social scientists were able to find “minimal effects” of media; however, eventually, researchers started acknowledging more fleeting effects than minimal. Nevertheless, political parties have recently adopted a new trend of campaigning through SNS (Social Networking sites). With the high penetration of internet and social media in Pakistani society, political parties including PTI and other traditional political parties, such as PMLN, MQM, and PPP hooked towards this trending social media for political campaigns. Furthermore, a remarkable transformation could also be observed in the political understanding and behavior of youth as well as the senior citizens or elderly members of the family (Friedman et al., 2011). In recent years, the use of SNSs by youth and the popular trend of election campaigns through social networking channels could be determined as one of the factors that plays a considerable role in rectifying cleavage-based voting behavior. The cleavage of age, education, and source of political informational access is playing a vital role in the change of political behavior of the population.

However, in this contemporary era of media boom and the explosion of information, media plays an imperative role in changing people’s opinion and decision-making of different age groups towards any preferred political party (Dalton, 1996). Education is another criterion to spark curiosity, grant access to knowledge, and encourage a political behavior. For instance, to vote in an election, one should be aware about how to access information about candidates and the procedure of voting. Thus, it is evident that having education and access to information gives one power to either change or have a special behavior towards a certain idea. Education also enables individuals to choose the accurate media platform that provides authentic information regarding political activities; hence provision of unbiased and accurate information can help educated people to use their vote appropriately (Gallego, 2010).

Other than demographic characteristics of individuals, information, and exposure to political media content also have a great impact on attitudes and behaviors, as people who have more exposure and access to political information through diverse media platforms are more involved in the political processes. Political information and interest in politics correlate with the attitudes and behaviors of people towards voting. When information on a topic is deeper and more connected to other concepts, resilience diminishes, and changing behavior on the topic becomes challenging (Bartels, 1993). The current paper explores the influence of social cleavage of age, education, and gender, as well as usage of social media has changed the political behavior of faculty and students in NUML university, Islamabad, Pakistan. This research study is unique in terms of its sample as NUML university. NUMLs faculty and students belong to diverse backgrounds, all have different political orientation towards political parties, their leaders, hence all have different political ideologies. Furthermore, the study also provides a detailed knowledge of how these demographic characteristics interact with media consumption of students and faculty, affects their political participation and voting behavior by highlighting the significance of social cleavage (age, gender and education). All such insights in current research makes this study a useful resource for future research. However, due to the limitation of time, upcoming researchers can extend the literature by taking sample from other universities in Islamabad. Since the study is quantitative, therefore researchers incorporated a survey by conducting a closed-ended questionnaire. Data was collected randomly from faculty and students of National University of Modern Languages (NUML), Islamabad. The current study has following research questions:

RQ1: Whether and to what extent does social cleavage influence political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

a. Does gender influence the political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

b. Does age influence the political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

c. Does education influence the political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

RQ2: Whether and to what extent does social media usage influence political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

Literature review

In political science the basic question is that how people decide whom to cast vote (Ashworth, 2012). Conventional arguments emphasize on the role of retroactive voting in which people of society look to past performance of politicians as evidence of their competence, hence they vote those who performed well during their rule (Healy and Malhotra, 2013). Such behavior of voting by citizens is understood through incentives by politicians, who they know that reward by citizens is relying upon good performance (Ferejohn, 1986). Such incentives fade out when citizens preferences get influenced by social cleavages of age, gender, religion occupation, social class, education and ethnicity.

Fujiwara (2015) provide evidence that response of voters by politicians has shifted towards allocation of public goods, i.e., politicians empower more the poor class of society in contact with technological convergence, hence they gain maximum public attention during elections. Shah et al. (2020) conducted a study on the interplay of voting behavior and religious socialization of people in KP, Pakistan particularly the Pashtun population. Researchers argue that though religion was a significant factor, but education and social class also have a role to play in understanding the political narratives by religious parties. Results show that voters who are illiterate and belong to a lower income group they have more inclination towards the religious political parties. Research conducted across different cultural and geographical contexts shows that education constructs different political opinions alongside scale of highly educated people on average, are considerably liberal and economically more conservative as compare to less educated people. Through becoming more educated and particularly attending university, those individuals internalize liberal cultural attitudes via socialization processes (Surridge, 2016). This “liberalizing” function explain education’s linkage with voting, such as more and less educated vote for different parties because of their typical cultural attitude (Kriesi et al., 2008).

Simon (2022) examined 2016 referendum, 2017 and 2019 General Elections, findings show that 67–91% of education’s total effect on vote choices was conducted crucially and indirectly, also voting choice divided along educational lines significantly because educational groups exhibited conflicting economic orientations, cue-taking behaviors and cultural attitudes. According to Rashid and Amin (2020) causes of voting patterns in developing democracy are based on psycho-social, sociological, and rational choice perspectives. They found that cleavages of age, gender, religion and other social affiliations prevailing in the society still play a significant role in impacting voters’ choices. In their research they investigated voting patterns of voters in District Dir, Pakistan in three elections (2002–2013). Results show that the role of religion is dominating in the electoral politics, moreover religious parties are more influential against the rival parties in terms of getting votes. This study shows that in a country like Pakistan still sociological/traditional factors affect the voting decisions of people apart from rational choices based on education etc.

According to recent Global Gender report, if the current trajectory of gender gap remains the same then it will take another 54.4 years for western Europe and 71.5 years for south Asian countries to end this gap (World Economic Forum, 2020). At global level, woman participation is particularly under represented as political candidates, voters and leaders (UNDP, 2020). Gender refers to certain roles and characteristics, when such characteristics are applied to elections, men are viewed as more capable of improving national economy, and have more denser networks in business and politics (Blackman and Jackson, 2021). In comparison, female can be seen as more wise, sensitive, honest and have the capacity in “compassion” issues for example woman rights and social policy (Bush and Prather, 2021).

Factually electoral quotas were accepted by over 130 countries (Hughes et al., 2019), becoming the key element of female legislative representation across the globe. Gender quotas can be observed in the context of increasing woman descriptive representation, also fundamental construction of policies in favor of the rights of woman (Bjarnegård and Zetterberg, 2022). Such quotas had positive impact on woman’s symbolic representation, inspiring woman to win for and run public offices (Clayton and Zetterberg, 2021), and most importantly to improve public’s perception of woman representation in politics. Shockley (2018) explore the case of Qatar and find that respondents have higher expectation level based on their female stereotyped activities of obtaining timely services and problem-solving habit. A recent study in US showed that individuals hold different attitudes towards females no matter they are voters, candidates or leaders. Researchers find individual holding benevolent sexist attitudes are less likely to view white female candidates as electable, and those holding hostile sexist attitudes are less likely to view black female candidates as electable (Britzman and Mehić-Parker, 2023).

In Pakistan, elections took place after every 5 years. The general elections of 2008,2013, and 2018 showed a significant change in woman’s voting behavior as well as their political participation in the pollical campaigns. This change was perhaps due to lowering the minimum voting age to 18 years along with the registered number of female voters was almost double from 2008 to 2012, i.e., 50 to 86% (Riaz and Akbar, 2022). In the year 2014, PTI party leader Imran Khan organized a protest against the mainstream political party in Pakistan, named Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz Group (PML-N), due to the charges of corruption against them. In the history of Pakistan, large number of women participated in the protest which transformed the protest in a big power show by PTI. Ultimately other political parties take strategic steps to mobilize woman in their parties too (Wu and Ali, 2020). Recent 2024 elections in Pakistan delivered a shocking surprise, as Imran Khan Leader won the elections which signals a coming crisis leading towards three structural changes 1) intensifying climate and national economic crises, 2) erosion of traditional authority patterns and 3) the rise of aspirational middle class (Malik and Tudor, 2024).

Theoretical framework

According to research, most people use decision strategies while taking a decision that include only a subset of all possible factors: Some people vote based on issues, some on parties, and still others on the basis of candidate’s personality traits. Identifying specific decision strategies used by individual voters would benefit the field because such evidence would identify not only who is likely to win an election, but also how different people participate cognitively in the democratic process (Redlawsk and Lau, 2013). As citizens of society, voters are expected to have concerns about their society. It then refers to necessary qualities for voting which includes membership and identity, awareness, rational decision-making, and knowledge that benefit the citizens (Brennan, 2016). Age is generally accepted as an indicator for the capability to vote, as there exist no agreed upon ways to evaluate the specific potential of the voter for such abilities (Nelkin, 2020). Rosenqvist (2020) conducted a study on Swedish register data and information on high school grades of young citizens and finds that those who turned 18 and ready to vote in national election or referendum did not pass with better grades in social studies comparing with those who had to wait a few more years to vote for elections. Though, researcher argued that age is not only a substitute for having political knowledge, even not for political engagement, but politically wise decision to cast vote depends much on age. Holbein et al. (2021) conducted a study on young people of Brazil and found no effect on the first-time eligibility of voters in context of their political interest and political knowledge, moreover another study conducted by Holbein and Rangel (2020) also showed that young people in US did not respond in terms of their political outcomes beyond election turnout. Age as an important factor draws attention of some scholars towards lowering voting age from 21 to 18 years which led to increase more political inequality and decline in turnout rates. Researchers used 2017 state election in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein as a case study, importantly age was lowered to 16 years before elections. They find that effect of lowering voting age to 16 years enfranchise a group of voters with unusual low inclination to turnout. Due to network homogeneity of young citizens’ vs. the old it might magnify the existing inequalities (Roßteutscher et al., 2022).

Said (2021) conducted a study in District Buner, KP Pakistan to explore voting choices, he found religion as a significant factor in framing the voting decisions of people. He particularly mentioned the political involvement of Ulma affecting the choices of people in Buner. Though religion was a significant factor, but during polling people do not vote for Ulma, instead they vote for other secular political parties. This shows that religion has importance in the social lives of people, but it hardly influences their voting choices. Similarly, Goldberg (2020) examined decline in religious and social class cleavage voting across four western countries (the United States, Great Britain, Switzerland, and Netherlands). Through examining a longitudinal post-election data, he claimed that over the last 40–60 years there is a decline in these cleavages. Results show a greater amount of political dealignment and larger turnout gap related to religious and class cleavage. It is perhaps due to the shift from traditional media to social media, as people construct their political opinions through social networking sites (Lee et al., 2018).

Social media era is accompanied with a high hope for internet and social networking websites to strengthen the democratic processes and equalizing socio technological innovations (Van Dijk and Hacker, 2018, p. 3–5). In Pakistan, technological and political development goes side by side, user experience an unprecedent level of interaction with people using Facebook. Pakistan has 40 million Facebook users and it is ranked 11 on the list of countries having the most Facebook users (Tankovska, 2021). It is perhaps mainstream political parties in Pakistan have shifted their focus from traditional to online media (Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter) which is deemed as an influencing medium for political campaigns. A revolutionary change in the political behavior of individuals has been observed during General Elections 2013, traditional media including TV and newspapers facilitated an evident extent of coverage of political parties and political situation of Pakistan. Additionally, social media utilization also became evident in political campaigns and electoral mobilization. With easy access to political information, people are now well-informed and aware of the political manifestos of different political parties and keep themselves updated with the political scenario intentionally or unintentionally (Rahmawati, 2014).

Political perception (Steppat et al., 2022) of people in Pakistan, particularly youth is largely determined by Facebook, since Facebook offers its user a range of unfiltered information by the State institutions (Yuan, 2018). A study conducted on role of Facebook in constructing political perception of youth during 2018 elections in Pakistan showed that Facebook users consider this site as biased in terms of expressing their opinions. Researchers argue that maybe users are not expose to fake news or they blindly accept the information. They have found that there is no statistical evidence which shows a difference in the voting behavior of the respondents based on gender and/or age (Sajid et al., 2024). The current paper explores the influence of social cleavage and social media usage in transforming political behavior of the people. Survey-based research was conducted through an open-ended questionnaire and a sample of 250 university students and faculty members was selected to analyze their voting decisions. Statistical tests were used to answer the research questions based on social cleavage of age, gender, and education. The individuality of this study relies on the role of social media as a catalyst which is not only used to empower youth and professionals, but activates their decision making and affects their political participation. This study will prompt the field of psephology in Pakistan, which is principally unnoticed, and help scholars to move out of the domain of distinct politics. Future research should consider political engagement of youth and professionals as an important mediator of social media use and political polarization.

Research methodology

The purpose of this study is to determine the influence of social cleavage such as gender, age, and education and media usage on the political behavior of faculty and students in NUML, Islamabad, Pakistan. The empirical findings of a phenomena using statistical or mathematical methods is known as quantitative research. To collect the data, a survey method and quantitative methodology was selected. Research objectives were taken into consideration when developing the questions. Data was gathered via a closed-ended questionnaire.

Research design

The study aimed to find the influence of age, education, gender and media usage for gathering political information on political behavior, i.e., voting behavior and political participation. The research was quantitative and conducted through a closed-ended questionnaire. Data was collected randomly from faculty and students of NUML University to explore changes in age, education, gender, and media usage on the political behavior. Data was collected from NUML university, since it offers a distinctive microcosm of Pakistan’s varied academic, political and cultural milieu. The diverse population at NUML includes faculty and students from different political, social, cultural backgrounds and provinces, having diverse political affiliations, beliefs and ideologies, that provides an ideal environment for examining the ways in which social cleavages like age, gender, and education influences political behavior. Furthermore, NUML is an educational institution, it is a vital place to learn how social media consumption affects the political behavior of future influencers and leaders.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires distributed both online and in-person. Participants were informed about the study’s purpose, assured of their anonymity, and provided informed consent before participation.

Sampling technique and sample size

The target population for the study were male and female residing in Islamabad. A sample size of 250 was drawn from the desired population and this sample size is adequate for reliable statistical analysis since multiple regression analysis requires a sample size of at least 200 for providing statistical and result robustness (Saunders and Townsend, 2018). Furthermore, a non-probability purposive sampling technique was used for individuals above the age of 18. 250 questionnaires were distributed among male and female faculty and students of NUML University, out of which 230 valid responses were achieved. The exclusion of erroneous or incomplete survey responses led to a decrease in sample size from 250 to 230, guaranteeing the validity and reliability of the data utilized for analysis.

Sample characteristics

The 230 participants of current study included both faculty and students from various departments of NUML University including social sciences (Departments of Psychology, Media and Communication Studies, Islamic studies, International Relations), languages (Korean and German Departments), and Management Sciences (Departments of Public policy and Business Administration). Faculty’s teaching experience ranged from 1 to 30 years, while the students were inexperienced rather enrolled in graduate or undergraduate programs across different departments/disciplines. Considering social cleavages of participants, there were 100 males and 83 females, their age ranged from 18 to 60 years. Education of selected participants also ranged from undergraduate to doctoral levels.

Considering their social media usage patterns among 250 participants, faculty members were more frequently inclined towards using Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and Twitter while students were found highly active on Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter. Almost all the participants including faculty and students were politically active both offline and online. Most of the respondents typically utilize social media to engage in political discussions, interact with those having analogous political ideologies and beliefs, share and debate political information, sign petitions, like, share and comment on political postings as well as to express their political opinions. Contrarily, there were few participants who reported to be less involved in politics on social media and in real life.

Data collection instrument

A survey questionnaire was employed as a data collection instrument. It constituted 38 items with close-ended questions. A questionnaire was divided into 3 sections; first section was related to general questions about social media usage. Second section explored the political behavior of individuals. For this purpose, 14 statements were developed to identify the political participation of individuals; and 13 statements were developed to recognize the voting patterns or behaviors of individuals. Both, political participation and voting behavior were used as indicators of political behavior. The third and last section consisted of questions regarding social cleavage and demographics such as age, education and gender. Demographic information in the questionnaire was designed to handle the independent variable of social cleavage. In order to ensure content validity and reliability, questionnaire contained items adapted from previously established scales and researches.

Firstly, voting behavior scale, created by Campbell (1960) was utilized to assess the voting behavior of respondents. It consisted of items that evaluate how frequently a person votes, what factors influences their choice to vote, and their responsibility towards voting. This scale consisted of 13 items on a five-point Likert scale. Secondly, Hoffman’s political participation scale was employed to assess the political participation level and political involvement of respondents (Hoffman, 2012). This scale typically consists of 20 items, however only 14 items were adapted for the study which measured a variety of political activities, including, taking part in online and offline political campaigns, attending political demonstrations, corresponding with political authorities, and engaging in online and offline political conversations. Both scales offer accurate assessments of people’s voting behavior and political participation and have been verified in several research. In earlier research, their validity and reliability were confirmed using statistical validation. The items utilized to evaluate the social media usage of participants were developed by the researchers themselves, however reliability and validity of this construct was also tested statistically by the researchers. The frequency of social media usage, which platforms of social media was frequently used and the motive behind using social networking sites were some of the items developed to measure social media usage.

Reliability and validity

The reliability and consistency of constructed instrument (questionnaire) was assessed via reliability test via SPSS software. With a Cronbach Alpha of 0.711, the research instrument was considered as unswerving, consistent, dependable, trustworthy, and devoid of inconsistencies. Furthermore, the use of already existing, established, verified and validated scales and instruments guaranteed content validity. Also, to ensure that the scales measure the required variables, factor analysis was used to evaluate construct validity.

Dependent and independent variables

Out of three variables employed in the current study, political behavior was the dependent while social cleavage and media usage were the independent variables of the study.

Operationalization of variables

Variables were acknowledged and operationalized in order to determine the results.

Political behavior

The researcher’s double goal was to find out political behavior. An individual’s voting pattern or other behaviors can be used to determine part one, and their level of political participation can be used to determine part two.

a. Political participation: It refers to the engagement of an individual in certain voluntary political activities such as money contributions for a political candidate, wearing a campaign sticker, attending public demonstrations, etc., which directly or indirectly influences political agendas and public policy.

b. Voting behavior: Voting behavior for the current study focuses on why people tend to vote, for whom they vote, and what influences their decision to vote for a particular candidate or political party.

Media usage

The current study defines media usage as the utilization of social media sites by the individuals to access political information. The term media usage also describes that how frequently people use the social media platform.

Social cleavage

Social cleavage is referred to as the criteria for the division of a society into discrete groups. For the current study, age, education, and gender are the social cleavages or distinct groups. The study will examine the influence of these social cleavages on the political behavior of individuals.

Data analysis

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the influence of social media usage and social cleavages of education, age and gender on political behavior. To achieve this goal, regression analysis test was performed on SPSS. Hierarchal multiple regression test was performed to investigate the impact of social cleavages, i.e., education, gender, and age on political behavior. Moreover, linear regression analysis was incorporated to evaluate the influence of social media usage on political behavior.

Findings

Multicollinearity detection test

Hierarchal Multiple regression analysis was performed to examine the relationship between social cleavage variables (gender, age and education) and political behavior. VIF (Variation Inflation Factor) test was conducted for regression model’s multicollinearity detection (measurement of the percentage of a predictor’s variation). The results of multicollinearity test indicated no significant multicollinearity based on the VIF values for gender, education, and age which were 1.27, 2.38 and 2.19, respectively. Since every VIF value is below 5, this suggests that multicollinearity is not a significant concern for any of the regression model’s predictors, thus the predictors can be employed in the regression analysis reliably.

Hierarchal multiple regression

Hierarchal multiple regression was performed to identify the most important predictors of social cleavage variables (gender, age and education) and their combined influence on the political behavior. The empirical model of regression analysis included the following predictors:

Age: The age of participants was represented by a continuous variable.

Gender: A categorical variable with a code of 1 for male and 2 for female.

Education: A continuous variable representing years of education successfully completed.

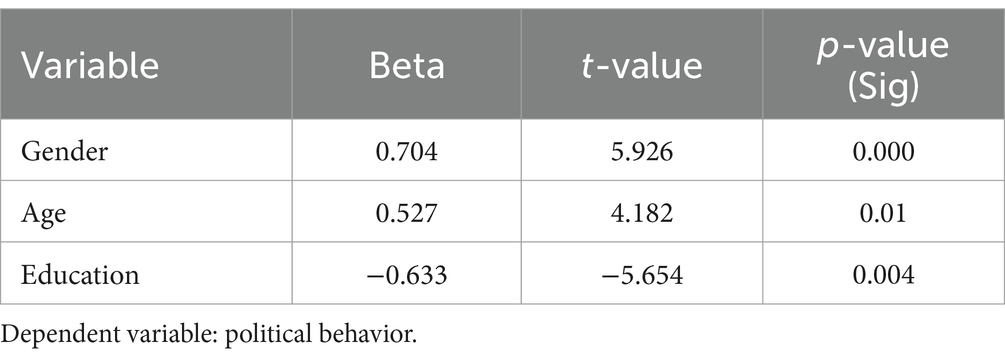

Table 1 exhibited a significant relationship between gender and political behavior (p = 0.000), age and political behavior (p = 0.01) and education and political behavior (p = 0.004). Thus, the empirical model of regression analysis exhibited that political behavior is significantly predicted by factors like gender, age, and education among NUML faculty and students. The influence of gender, age and education was further shown by the R2 value of 0.47, which exhibited that regression model can explain nearly 47% of variability in political behavior, highlighting social cleavage variables’ significant impact.

RQ1: How does social cleavage influence political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

A. Does gender influence the political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

The findings indicated that the multiple regression model’s overall fit was statistically significant (Beta = 0.704, p = 0.003), implying a sizable amount of variance in political behavior due to gender.

According to Table 1, gender-specific coefficient (Beta = 0.704) shows that males have higher political behavior scores than females by 0.704 units. This effect shows that men exhibit more positive political behavior than women, and it is statistically significant.

This means that that gender has a considerable influence on political behavior in a way that male faculty and students of NUML tend to participate in political activities more significantly than female faculty and students of NUML, also males tend to vote more responsibly and wisely without any family pressure.

B. Does age influence the political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

According to Table 1, multiple regression model’s overall fit was statistically significant (Beta = 0.527, p = 0.01), implying a sizable amount of variance in political behavior due to age. Thus, it is obvious that younger age group of students and faculty of NUML are more likely to participate in political activities as well as they are more likely to vote wisely without any influence of family or peer pressure as compared to older age groups. Therefore, it is concluded that age plays a major role in predicting political behavior.

C. Does education influence the political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

The findings of Table 1 showed that regression model’s overall fit was statistically significant (Beta = −0.633, p = 0.004), suggesting that education brings about variance in political behavior.

Additionally, negative value of education-specific coefficient (Beta = −0.633) indicated that participants with higher education qualifications have higher political behavior scores than those with less educated by 0.63 units. This means that education has a considerable influence on political behavior. Faculty and students of NUML with higher educational qualifications, i.e., graduate, and post-graduate tend to demonstrate positive political behavior, as they are wiser in their voting decisions and political participation as compared to less educated faculty and students of NUML.

RQ2: Whether and to what extent does social media usage influence political behavior of faculty and students at NUML university?

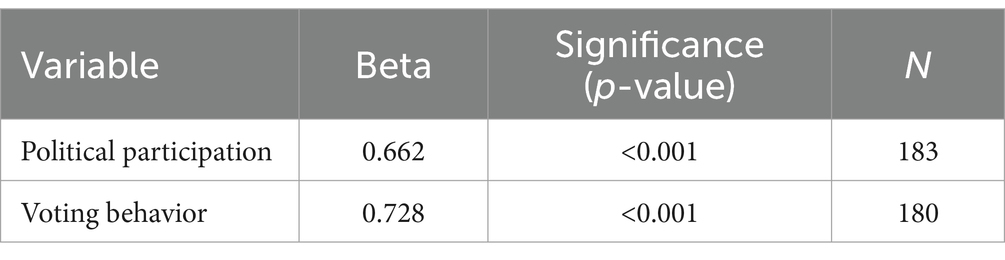

According to regression analysis, Table 2 shows a positive association between social media usage and political participation. Likewise, results also reveal that voting behavior is also positively correlated with social media usage. Hence, utilizing social media more frequently allows people to be wiser in their voting decisions and active in political participation. The more people rely on social media for political information, the more they are active in political activities and they tend to vote sensibly for the right candidate.

Conclusion

In the current study, researchers tried to pinpoint the patterns and shifts in people’s political behavior brought about by their use of social media and social cleavage. To make this study credible, it determines whether and to what degree social media usage and social cleavages influence an individual’s political behavior, a sample of NUML university faculty and students were selected.

Results of the study showed that social cleavage significantly affects people’s political behavior. Gender being the primary category for social cleavage showed a greater impact on voting patterns and political engagement. Findings demonstrate that males engage more in political activities than females. Males also participate in a wider range of political demonstrations, contribute to political causes, share political content including images, videos, and information and indulge in discussion about politics with their peers than females. Similarly, males are more sensible and responsible than females, as male typically support deserving candidates who work for the welfare of the people. Moreover, voting choices of males were independent, without any external influence and bias. Another interesting factor was that most of the female respondents besides being educated cast their vote because of family pressures. It was shown in the results that most females had no affiliations with a political party and remaining supported a party because of their family affiliations with that political party. It is therefore concluded that males demonstrate positive political behavior as compared to females.

According to research findings, people from younger age group were more likely to participate in political activities, they cast vote without any influence of family or peer pressure as compared to other age groups, also they support democracy. In contrast, respondents from older age group supported dynastic politics, as they had political affiliations like their family. They get into political discussions and participate in political activities because of their family; thus, their political behavior is influenced by their family. As a result, age is a significant predictor when it comes to influencing political behavior. It also indicates that educated people tend to support democracy.

Apart from gender and age, education is also a crucial social cleavage factor in terms of influencing political behavior. According to findings, individuals with higher level of education tend to behave more politically responsible because they make more informed voting choices and are more involved in politics than those with lower levels of education. Furthermore, majority of educated individuals mentioned a feeling of civic duty as their motivation for casting vote. Rather than taking pressure from their families, they vote as a symbol of their civic duty. Thus, education plays a crucial role in influencing and changing people’s political behavior.

In addition to examining social cleavage, the study also examined the impact of social media use on people’s political behavior. Findings show that individuals who use social media more frequently engage in political activism and vote responsibly, thereby displaying positive political behavior among themselves. People quickly become aware of political developments through social media, which makes them aware of their political choices. Consequently, people who rely more on social media for political information tend to be more involved in politics and cast vote rationally for right candidate.

Limitations and future research

• One notable limitation is that the sample is taken from a single institution, i.e., NUML, Islamabad and also the sample size of 250 is too small to represent entire Pakistan’s population, thus restricting the results’ generalizability. Furthermore, sample is restricted to well-educated people in academic settings, it could not fairly represent the political attitudes of the broader public, which includes people from a range of educational levels. Therefore, it is recommended that future researchers should increase the sample size to encompass other Pakistani universities and areas in order to improve the findings’ generalizability.

• The study relied too much on self-reported data from surveys that might lead to social desirability bias, whereby respondents give responses they believe to be socially acceptable instead of reflecting their actual beliefs or actions. Future researches should employ qualitative methodologies like focus groups and interviews in order to avoid such biases and acquire a deeper understanding of political behavior.

• As the current study is based on cross-sectional survey, it only records a single point in time, making it challenging to determine causality or track changes over time. Thus, future researchers should go for longitudinal studies to investigate the temporal evolution of political behavior and to demonstrate the causal relationship between political behavior and demographic factors.

• The study overlooked the impact of conventional media on political behavior because it specifically examined the use of social media.

• The current research focused on few facets of political behavior, such as political participation and voting behavior, however other significant dimensions of political behavior including political efficacy, political ideology, and political affiliations were not considered. In order to understand the complexity of political behavior in a more nuanced manner, it is suggested to include a greater variety of political behavior metrics, such as political efficacy, civic engagement, political affiliations and political knowledge in future studies.

Policy recommendations

• To exhibit constructive political behavior for females, governments should work to reduce the gender gap in political engagement. Women should be granted equal opportunities to engage in political activities and electoral campaigns.

• Media institutions should work responsibly to positively influence the political behavior by ensuring equal access to information for all citizens, regardless of age groups. This is because older people are resistant to changing their political behavior, and an age gap causes differences in political participation and voting behavior.

• Findings indicate that education is another requirement to spark curiosity, provide access to information, and elicit a specific political behavior; as such, education must to be encouraged to help people vote in the right ways.

• Political parties should switch their focus from traditional to social media campaigns in order to influence people’s political behavior, as the data indicate that using social media increases political participation and improves voting behavior.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

IA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AZ: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmed, S., and Skoric, M. M. (2014). My name is Khan: The use of Twitter in the campaign for 2013 Pakistan general election. In R. H. SpragueJr (Ed.), HICSS 2014: Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Science (pp. 2242–2251). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society. doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2014.282

Ashworth, S. (2012). Electoral accountability: recent theoretical and empirical work. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 15, 183–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-031710-103823

Bartels, L. M. (1993). Messages received: the political impact of media exposure. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 87, 267–285. doi: 10.2307/2939040

Berelson, B. R., Lazarsfeld, P. F., and MacPhee, W. N. (1954). Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign (VOL 10), University of Chicago Press.

Bjarnegård, E., and Zetterberg, P. (2022). How autocrats Weaponize Women's rights. J. Democr. 33, 60–75. doi: 10.1353/jod.2022.0018

Blackman, A. D., and Jackson, M. (2021). Gender stereotypes, political leadership, and voting behavior in Tunisia. Polit. Behav. 43, 1037–1066. doi: 10.1007/s11109-019-09582-5

Blumler, J. G., and Kavanagh, D. (1999). The third age of political communication: influences and features. Polit. Commun. 16, 209–230. doi: 10.1080/105846099198596

Britzman, K., and Mehić-Parker, J. (2023). Understanding electability: the effects of implicit and explicit sexism on candidate perceptions. J. Women Politics Policy 44, 75–89. doi: 10.1080/1554477X.2023.2155773

Bush, S. S., and Prather, L. (2021). Islam, gender segregation, and political engagement: evidence from an experiment in Tunisia. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 9, 728–744. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2020.37

Campbell, A. (1960). Surge and decline: A study of electoral change. Public opinion quarterly, 24, 397–418.

Castells, M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International journal of communication, 1, 29. Available at http://ijoc.org.

Clayton, A., and Zetterberg, P. (2021). Gender and party discipline: evidence from Africa’s emerging party systems. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 115, 869–884. doi: 10.1017/S0003055421000368

Dalton, R. J. (1996). Political cleavages, issues, and electoral change. Comparing Democracies: Elections and voting in global perspective, 2, 320–321. Available at: https://public.websites.umich.edu/~franzese/Dalton.LNN.CompareDems.Ch13.FreezeThaw.pdf

Denton, R. E., and Woodward, G. C. (1990). Political communication in America, the University of Michigan, Praeger.

Ferejohn, J. (1986). Incumbent performance and electoral control. Public Choice 50, 5–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00124924

Friedman, W., Kremer, M., Miguel, E., and Thornton, R. (2011). Education as liberation? (No. w16939). National Bureau of Economic Research. Available at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w16939/w16939.pdf

Fujiwara, T. (2015). Voting technology, political responsiveness, and infant health: evidence from Brazil. Econometrica 83, 423–464. doi: 10.3982/ECTA11520

Gallego, A. (2010). Understanding unequal turnout: Education and voting in comparative. Elect. Stud. 29, 239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2009.11.002

Goldberg, A. C. (2020). The evolution of cleavage voting in four Western countries: structural, behavioural or political dealignment? Eur J Polit Res 59, 68–90. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12336

Glasford, D. E. (2008). Predicting voting behavior of young adults: The importance of information, motivation, and behavioral skills. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38, 2648–2672. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00408.x

Healy, A., and Malhotra, N. (2013). Retrospective voting reconsidered. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 16, 285–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-032211-212920

Hoffman, L. H. (2012). Participation or communication? An explication of political activity in the internet age. J. Inf. Technol. Polit. 9, 217–233. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2011.650929

Holbein, J. B., and Rangel, M. A. (2020). Does voting have upstream and downstream consequences? Regression discontinuity tests of the transformative voting hypothesis. J. Polit. 82, 1196–1216. doi: 10.1086/707859

Holbein, J. B., Rangel, M. A., Moore, R., and Croft, M. (2021). Is voting transformative? Expanding and meta-analyzing the evidence. Polit. Behav. 45, 1015–1044. doi: 10.1007/s11109-021-09746-2

Hughes, M. M., Paxton, P., Clayton, A. B., and Zetterberg, P. (2019). Global gender quota adoption, implementation, and reform. Comp. Polit. 51, 219–238. doi: 10.5129/001041519X15647434969795

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Griep, Y., and Edmonds, M. (2018). Personality, religion, and politics: An investigation in 33 countries. European Journal of Personality, 32, 100–115. doi: 10.1002/per.2142

Malik, A., and Tudor, M. (2024). Pakistan's coming crisis. J. Democr. 35, 69–83. doi: 10.1353/jod.2024.a930428

Mezzera, M., and Sial, S. (2010). Media and Governance in Pakistan: A controversial yet essential relationship. Initiative for Peace Building. Available at: https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/20101109_CRU_publicatie_mmezzera.pdf

Nelkin, D. K. (2020). What should the voting age be? J. Pract. Ethics. 8. Available at: http://www.jpe.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Online-Dana-Kay-Nelkin-V4-Oct-2020.pdf (Accessed August 15, 2024).

Rahmawati, I. (2014). Social media, politics, and young adults: The impact of social media use on young adults political efficacy, political knowledge, and political participation towards 2014 Indonesia general election (Masters thesis, University of Twente). Available at: https://essay.utwente.nl/65694/1/Rahmawati%20Indriani%20-s%201498436%20scriptie%20FINAL%20THESIS.pdf

Rashid, M., and Amin, H. (2020). Voting pattern in district of Dir: a case study of three general elections (from 2002 to 2013). SJESR 3, 154–161. doi: 10.36902/sjesr-vol3-iss3-2020

Redlawsk, D. P., and Lau, R. R. (2013). “Behavioral decision making” in Oxford handbook of political psychology. eds. L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, and J. S. Levy. 2nd ed (New York: Oxford University Press), 130–164.

Riaz, S., and Akbar, M. (2022). Political participation of women: a study of Pakistan (2001–2013). Glob. Sociol. Rev. VII–II, 280–290. doi: 10.31703/gsr.2022

Roßteutscher, S., Faas, T., Leininger, A., and Schäfer, A. (2022). Lowering the quality of democracy by lowering the voting age? comparing the impact of school, classmates, and parents on 15-to 18-year-olds political interest and turnout. German Politics, 31, 483–510. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2022.2117800

Rosenqvist, O. (2020). Rising to the occasion? Youth political knowledge and the voting age. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 781–792. doi: 10.1017/S0007123417000515

Said, M. G. (2021). The impact of religion on voting behavior. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 9, 14–24. doi: 10.18510/hssr.2021.922

Sajid, M., Javed, J., and Warraich, N. F. (2024). The role of Facebook in shaping voting behavior of youth: perspective of a developing country. SAGE Open 14:21582440241252213. doi: 10.1177/21582440241252213

Saunders, M. N., and Townsend, K. (2018). Choosing participants. Sage handbook of qualitative business and management research methods, 480–494.

Shah, H., Mehmood, W., Ali, S., and Khan, I. (2020). Religious socialization and voting behaviour in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Glob. Media Soc. Sci. Res. J. 5, 57–71.

Shockley, B. (2018). Competence and electability: exploring the limitations on female candidates in Qatar. J. Women Politics Policy 39, 467–489. doi: 10.1080/1554477X.2018.1511125

Simon, E. (2022). Explaining the educational divide in electoral behaviour: testing direct and indirect effects from British elections and referendums 2016–2019. J. Elect. Public Opin. Parties 32, 980–1000. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2021.2013247

Steppat, D., Castro Herrero, L., and Esser, F. (2022). Selective exposure in different political information environments–How media fragmentation and polarization shape congruent news use. Eur. J. Commun. 37, 82–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2017.11.005

Surridge, P. (2016). Education and liberalism: pursuing the link. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 42, 146–164. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2016.1151408

Tankovska, H. (2021). Countries with the most Facebook users. Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/268136/top-15-countries-based-on-number-of-Facebook-users/ (accessed February 9, 2021).

UNDP. (2020). Human development perspectives tackling social norms, a game changer for gender inequalities. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hd_perspectives_gsni.pdf (accessed July 29, 2024).

Van Dijk, J. A., and Hacker, K. L. (2018). Internet and democracy in the network society. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781351110716

World Economic Forum. (2020). Global Gender Gap Report. Available at: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf (accessed July 31, 2024).

Wu, X., and Ali, S. (2020). The novel changes in Pakistan’s party politics: analysis of causes and impacts. Chin. Political Sci. Rev. 5, 513–533. doi: 10.1007/s41111-020-00156-z

Yuan, L. (2018). A generation grows up in China without Google, Facebook or twitter : The New York Times, 6 Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/06/technology/china-generation-blocked-internet.html (Accessed July 30, 2024).

Keywords: political behavior, social cleavage, media usage, NUML, education, gender, age

Citation: Anum I and Zulfiqar A (2024) Influence of social cleavage and media usage on political behavior: a case of Pakistan. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1405634. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1405634

Edited by:

Yuan Wang, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Fani Kountouri, Panteion University, GreeceFrancisco Antonio Coelho Junior, University of Brasilia, Brazil

Copyright © 2024 Anum and Zulfiqar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Isma Anum, aXNtYS5hbnVtQG51bWwuZWR1LnBr; Amna Zulfiqar, YW16dWxmaXFhckBudW1sLmVkdS5waw==

Isma Anum

Isma Anum Amna Zulfiqar

Amna Zulfiqar