95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 21 June 2024

Sec. Elections and Representation

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1401758

This article is part of the Research Topic The Affective Turn in Radical Right Research: Crossing Disciplinary and Geographic Boundaries View all 7 articles

Who supports the populist radical right (PRR)? And under what circumstances? We theorize that social status-related envy (SSRE) is the construct that integrates personality- and grievance-based theories of PRR support. To assess our theory, we estimate psychological network models on German survey data to map the complex relationships between PRR support, Big Five personality traits, facets of narcissism, political attitudes, and multiple constructs measuring objective and subjective social status. Our findings confirm previous studies detecting two routes to PRR support: a disagreeable and an authoritarian one. The Bifurcated Model of Status-Deprived Narcissistic Right-Wing Populism claims that SSRE is the distant predictor of PRR support and the two constructs are connected by two pathways. The middle-class route is characterized by disagreeable narcissism (Rivalry) and nativism, while the lower-class route by Neuroticism (potentially Vulnerable Narcissism) and authoritarian right-wing populism. Moreover, we find preliminary support for our expectation that PRR voting is explained by the activation of narcissistic traits by SSRE.

Who supports the populist radical right (PRR)? There are several strands of literature that all emphasize different elements. The “left behind thesis” (Mutz, 2018, p. 4331)—from the field of political sociology—claims that PRR supporters are losers of globalization who are “relegated to vulnerable economic and social position” (Gidron and Hall 2020, p. 1044, see also Roubini 2016; Guiso et al. 2017; Rodrik 2018; Kurer 2017; Burgoon et al. 2019). Studies in political psychology describe two routes to PRR voting: one via trait Agreeableness (negatively) and the other via Authoritarianism (positively) (Bakker et al., 2016, 2021). Right-wing ideology and PRR support are also negatively associated with Openness to Experience and positively with Conscientiousness and Neuroticism (Gerber et al., 2011; Zandonella and Zeglovits, 2013; Aichholzer and Zandonella, 2016; Obschonka et al., 2018). A more recent thread of literature has linked the status-focused personality trait Narcissistic Rivalry—a disagreeable form of Narcissism—to PRR voting (Mayer et al., 2020; Mayer and Nguyen, 2021).

Yet neither sociological nor psychological models alone can provide a full answer to the question why people vote for PRR parties. On the one hand, assuming that there exists a personality type that is typical for PRR supporters poses a curious paradox. After all, personality traits are relatively stable over time, while PRR support fluctuates. On the other hand, not everyone with low socio-economic status (SES) cast their votes for PRR candidates, only those who are genuinely concerned about dominance and social status (Bartusevicius et al., 2020; Petersen et al., 2021a). Therefore, objective and subjective social status may have distinctive roles in explaining PRR support. We argue that social status-related envy (SSRE) is an affective mechanism that unites psychological and sociological models of PRR voting. Our central expectation is that SSRE is the principal distant predictor of PRR support. Furthermore, we delineate the Radical Activation (RADACT) framework, arguing that SSRE activates Vulnerability and Rivalry, two status-focused personality traits, making them consequential for PRR support.

To integrate sociological and psychological approaches, we employ an innovative method. Recent methodological advances have made it possible to explore separate mental processes by means of attitudinal network analysis (see e.g., Brandt et al., 2019). We employ psychological network modeling (Golino and Epskamp, 2017): a methodological framework that is capable of mapping conditional independencies between multiple variables and can thus plot complex mediation pathways. This method enables us to explore how variables like personality traits and attitudes, but also voting behavior and socio-demographic variables, relate. The main strength of psychological network modeling is that in contrast to structural equation modeling (SEM) and least square regressions, model estimation does not require researchers to predetermine the causal ordering of the variables. This renders it an exceptionally suitable approach for an exploration of the intricate dynamics between psychological and sociological constructs that illuminate the underpinnings of voting behavior.

Specifically, we employ German survey data to estimate mixed graphical models (MGM; e.g., Yang et al., 2014). We map the complex relationship between voting for the Alternative for Germany (AfD), the Big Five personality traits, two components of Narcissism, measurements of SES and SSRE, as well as attitudinal and ideological variables. We build on two recent studies that have also linked Narcissism and PRR voting in the German context (Mayer et al., 2020; Mayer and Nguyen, 2021). Yet we advance the field in three main ways. First, these existing studies employ SEM and presume that Narcissism is an antecedent of ideological variables which, in turn, shape attitudes that finally lead to PRR voting. With psychological networks, one can relax such requirements and test whether Narcissism constitutes a path separate from Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) in predicting PRR support. Second, just as network models do not require researchers to determine whether a construct is an independent, dependent, or mediator variable, it does not differentiate between explanatory and control variables. Hence, these models are capable of treating SES-related variables as constitutive of the different paths. Third, we emphasize the importance of SSRE—an emotion that not only amplifies the association between status-related personality traits and PRR support, but also links psychological and sociological approaches to understanding PRR voting.

Our findings corroborate and refine the understanding of the two routes to PRR voting as outlined by Bakker et al. (2021). Our research highlights two pathways linking SSRE to PRR voting: one is characterized by Neuroticism, Authoritarianism, and anti-elitism, the other by Narcissistic Rivalry (and, to some extent, disagreeableness) and nativism. The models also suggest that the latter, Narcissism path, is activated by high SSRE, but not by low SES. The paper paves the way for future research stressing the importance of integrating psychological and sociological approaches as well as distinguishing different profiles of PRR supporters.

Global outsourcing, high unemployment, and rising inequality have been linked to PRR success (Autor et al., 2016; Algan et al., 2017; Kurer, 2017; Rovny and Rovny, 2017; Colantone and Stanig, 2018; Burgoon et al., 2019; Ballard-Rosa et al., 2021). Sociological theories claim that these economic developments have most threatened the economic status and labor market position of so-called losers of globalization (citizens with low education and employment status, e.g., Kriesi et al., 2008). Consequently, they feel marginalized and left behind, which is why they vote for the PRR. Accordingly, employment status (e.g., Kurer, 2020; Sandel, 2020) and education level (e.g., Cordero et al., 2022; van Noord et al., 2023) have been linked to PRR support because economically vulnerable voters are easier to be convinced of elite malfeasance during economic changes or crises (Betz, 1994; Kitschelt and McGann, 1997; Esping-Andersen, 1999). However, it has also been shown that beyond objective deprivation (e.g., low income), subjective economic grievances and cultural threats (e.g., perceived threat posed by non-white citizens, immigrants, so-called “gender ideology” and the growing importance of China) appear to better explain PRR voting patterns (Kriesi et al., 2008; Lucassen and Lubbers, 2012; Mutz, 2018; Abou-Chadi and Kurer, 2021).

It has been suggested that the economic and ideological landscape prevailing in the 1980s and 1990s may explain why objective deprivation and subjective status threats (SST) bear similar importance in explaining PRR voting patterns. First, one perspective is that the ethos of meritocratic individualism justifies inequalities as a result of fair competition. As a consequence it reduced solidarity and integration between individuals and social groups and intensified the dismantling of traditional class identities in the post-industrial era. Furthermore, it also spurred competition for status recognition throughout the entire society (Wacquant, 2010; Bröckling, 2016; Mäkinen, 2016; Wilterdink, 2017; Sandel, 2020). Second, following another perspective, both left- and right-wing parties embraced neoliberal agendas, and as a result, the two sides only differentiated themselves along cultural issues (Gidron and Hall, 2017). Whilst the economic developments impoverished the working class (e.g., global outsourcing, rising within-country inequality; Feenstra and Hanson, 1996; Dancygier and Walter, 2015), left-wing parties aimed at institutionalizing new cultural policies (e.g., gender equality, multiculturalism; Bromley, 2009; Dobbin, 2009; Banting and Kymlicka, 2013). Therefore, while the left did not represent the working class economically, their cultural policies posed potential threats to citizens who based their social status on ethnicity or gender (Pateman, 1988). From the dawn of this century, the PRR's welfare chauvinist policies (e.g., social safety and job protection for the ethnic majority; Betz and Meret, 2013; Lefkofridi and Michel, 2017) could therefore address the electorate in two distinct ways: they both offered an attractive alternative to former leftist programs for citizens who competed for economic position and appealed to conservative voters who rivaled for cultural status. As a consequence, the PRR could build a constituency spanning across socioeconomic divides (Wealth Paradox; Mols and Jetten, 2017; Jetten, 2019) by successfully applying cultural frames to narrate economic problems.

By applying cultural frames (see Golder, 2016), PRR parties successfully mobilize around the issue of immigration (Rydgren, 2007; Ivarsflaten, 2008). Anti-immigrant sentiment (AIS) emerges as the strongest proximal predictor of PRR support (Van der Brug et al., 2000) and mediates the effect of economic grievances (Golder, 2016; Mols and Jetten, 2020). Cultural grievances, however, extend beyond the single issue of immigration and encompass general aversion to progressive values fostered by the elites, and the resulting sense of marginalization (Gest et al., 2018; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Perceived social marginalization consistently predicts PRR support (Gidron and Hall, 2020), and the effect of economic marginalization on anti-elitist attitudes is mediated by relative deprivation and declinism (a negative view on the governance of society by the elite; Elchardus and Spruyt, 2016). Specifically, PRR voters attribute social decline to the elites who discriminate against “the people” and provide certain minority groups with resources that majority citizens are entitled to. In sum, cultural frames are often applied to narrate status conflicts between majority and minority groups resulting from elite malfeasance.

Cultural issues are mostly associated with either place-based (cf. Walsh, 2012; Cramer, 2016; Fitzgerald, 2018; Munis, 2022) or education-based (e.g., Stubager, 2009; Spruyt and Kuppens, 2015; Noordzij et al., 2019; van Noord et al., 2023) social identities and conflicts. On the one hand, the status of rural citizens is threatened by their lack of representation by urban elites and their subordination to the center (Bollwerk et al., 2021; de Lange et al., 2023). Accordingly, the strength of place-based identity predicts support for PRR parties (Ziblatt et al., 2020). On the other hand, educational level is a primary indicator of one's social status concerning both economic and cultural capital (van Noord et al., 2023), and it negatively predicts PRR support, independent of one's occupational class (Ivarsflaten and Stubager, 2012). The educational system both equips individuals with skills for well-paid jobs and disseminates the cultural patterns of the ruling class (van Noord et al., 2023). In this latter way, it shapes the habitus (ways of being) of citizens (Bourdieu, 1977). Habitus—similarly to personality—indicates enduring characteristics shaped by the environment that molds emotions and behavior and carries implications for social status (Bourdieu, 1977; Elias, 1978; Roberts and Jackson, 2008; Bucciol et al., 2015; Colman, 2015; Wolfram, 2023). In other words, the relationship between (low) social status and PRR voting may be connected by a certain personality type and related emotions (Scheer, 2012). Apparently, both objective deprivation and SST drive PRR support. On the one hand, rural and uneducated citizens may feel that their lifestyle is unrepresented by the cosmopolitan elites. On the other hand, rather than simply fearing a decline in their SES, some PRR voters may fear losing their dominant group status (Mutz, 2018), which they feel entitled to, as the establishment allegedly favors (ethnic and sexual) minorities over the majority. Similar to Arceneaux et al. (2021), we, therefore, expect that status-related personality traits are connected to social status-related emotions in explaining PRR support.

Caprara and Zimbardo (2004) contend that voters' self-reported traits are consequential to voting behavior as their congruence with perceptions of leaders' personalities may signal similarities in values and ideology. Cross-sectional country studies show that Agreeableness and populist support are negatively correlated (Bakker et al., 2016, 2021). In addition, an experimental manipulation showed that the anti-establishment message activates disagreeableness and leads to populist support (Bakker et al., 2021). Additionally, Aichholzer and Zandonella (2016) demonstrated that the negative association between Agreeableness and support for the Austrian FPÖ was mediated by perceived immigrant threat (PIT). Nevertheless, their findings suggest another route to PRR voting. The effect of Neuroticism, Openness to Experience, and Conscientiousness is mediated by RWA (and PIT), independently of Agreeableness. The present study focuses on different mediational and moderational roles to explore the sociological and psychological mechanisms behind the two routes.

Although most studies in this field have considered the Big Five personality traits (often in relation with attitudes like RWA and SDO), recent studies have examined to what extent PRR support is also rooted in Narcissism (Mayer et al., 2020; Mayer and Nguyen, 2021).1 Narcissism is the personality type that is most closely associated with status motives (Jonason and Ferrell, 2016; Jonason and Zeigler-Hill, 2018; Moshagen et al., 2018). It is defined as entitled self-importance (Krizan and Herlache, 2018) that may engender positive sentiments about the self as well as groups one belongs to (Hatemi and Fazekas, 2018). Narcissistic behavior aims at protecting the self against ego threats by maintaining superior status through the devaluation of others and through striving for supremacy (Horton and Sedikides, 2009).

Narcissism manifests in two variants: Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism. While Vulnerable Narcissism is negatively related to Extraversion, positively to Neuroticism, and linked to low well-being and negative emotionality (e.g., shame-proneness and envy), Grandiose Narcissism exhibits the exact opposite patterns.2 Both types are characterized by hubristic pride,3 strong emotional variability due to contingent self-esteem, disagreeableness (especially impoliteness), and entitlement. Disagreeableness is manifested in anger outbursts, however, while it is expressed in uncontrollable rage and dysfunctional aggression among vulnerable narcissists, grandiose narcissists use it instrumentally to assert dominance in the face of status threats. Finally, whereas grandiose narcissist explain their entitlement through perceived superiority, vulnerable narcissist justify it with perceived injustice (Besser and Priel, 2010; Zhang et al., 2015; Czarna et al., 2018; Freis and Hansen-Brown, 2021; Zajenkowski and Szymaniak, 2021). Building on Weiss et al. (2019), we distinguish three facets of Narcissism: Admiration, Rivalry, and Vulnerability. While the combination of Admiration and Rivalry constitutes Grandiose Narcissism, that of Rivalry and Vulnerability embodies the vulnerable type.

We argue that Narcissism is a personality characteristic that is shared by many PRR voters. Mayer et al. (2020) have shown that Narcissistic Rivalry is connected to PRR support and it is mostly because narcissistic status maintenance through devaluation and supremacy is congruent with the nativist component of PRR ideology. We theorize that the vulnerable type of Narcissism is also related to PRR support; those who feel vulnerable are sensitive to perceived injustice, hence are likely to support parties that express anti-elitist/anti-establishment messages (Freis and Hansen-Brown, 2021). In other words, we hypothesize that the aforementioned two routes to PRR support, the disagreeable and the neurotic-authoritarian, are captured by the two facets of Narcissism: Rivalry and Vulnerability.

We argue that envy links sociological and psychological models of PRR support. Envy is an emotional response arising from perceptions of inferior status, which motivates individuals to reduce status differences. While benign envy entails hope for success and motivation to improve performance, malicious envy is related to fear of failure, and hostility (Van de Ven et al., 2009; Lange and Crusius, 2015a,b). As a competitive emotion, envy is not (necessarily) the result of an individual lacking something; rather, it can be generated by the comparative nature of self-worth, meritocratic norms, and the belief that inequality or poverty may be deserved (Nozick, 1974).

Narcissistic individuals are described as “often envious of others or believing that others are envious of [them]” (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994, p. 661). However, various forms of envy relate differently to specific facets of Narcissism. First, while Admiration predicts benign envy, Rivalry is associated with malicious envy (Lange et al., 2016). Second, whereas it is rather Vulnerable Narcissism that is (negatively) related to the expression of this emotion toward high-status peers (Krizan and Johar, 2012), when encountering relative deprivation, the grandiose type is also prone to envy (Neufeld and Johnson, 2016). In sum, when an individual's lower status is salient, both types of Narcissism are characterized by envy.

Therefore, we expect that envy-driven status-seeking plays an important role in the Narcissism-PRR connection, and, more generally, in connecting the sociological and psychological approaches to PRR voting. We propose the following mechanism. In response to perceived status gaps between the self and a superior other, people experience envy. Bolló et al. (2020) demonstrate that both objective and subjective status differences evoke envy. Yet subjective status differences have a stronger effect. Hence, people who are concerned with social status—those who score high on Narcissism—will experience what we label “social status-related envy” (SSRE) when facing a status threat. As previously discussed, SSRE is the primary emotion elicited by perceived status differences. It manifests itself in rivalrous behavior against individuals who are perceived to be responsible for one's undeserved inferiority and loss of status (Da Silva and Vieira, 2019). Hence, we argue that SSRE constitutes one of the main affective mechanisms that drives PRR support.

The role of SSRE in the relationship between Narcisissm and PRR support is still a relatively uncharted area. For this reason, the primary contribution of this paper lies in its extensive exploration of the role of SSRE in shaping PRR support.

Our first research question therefore is:

Research Question 1 (RQ1). Is SSRE directly and positively associated with PRR support?

As discussed, previous studies have shown that anti-establishment messages resonate with disagreeable people (Bakker et al., 2021). This suggests that the antagonism inherent in this personality trait resonates with the negativity present in anti-establishment messages (e.g., anti-liberal, anti-pluralist, anti-internationalist; Urbinati, 2019, p. 22.). Although it is likely that anger and negativity are related to experiencing status threats, status threat has a more specific link with PRR than negativity in general. Consequently, Agreeableness may be less conducive to portraying the PRR personality than Narcissistic Rivalry. In other words, Narcissistic Rivalry may mediate the effect of Agreeableness on PRR support.

Research Question 2 (RQ2). Does Narcissistic Rivalry explain the association between Agreeableness and PRR support?

Narcissism positively predicts out-group prejudice, PIT, SDO, and RWA (Hodson et al., 2009; Schnieders and Gore, 2011; Cichocka et al., 2017; Marchlewska et al., 2019). Pellegrini (2023)'s psychological network models demonstrated that (1) RWA (and SDO to a certain extent) almost entirely mediate the effect of populist attitudes (people homogeneity, anti-elitism, people sovereignity, and Manichaeism) on support for the Italian PRR party Lega, and that (2) anti-immigrant attitudes constitute a separate path from populist attitudes (it is, however, not directly related to PRR support, only via RWA and SDO). We argue that Rivalry is a more suitable candidate to represent the second route than anti-immigrant sentiment. Whereas the latter captures a policy position (e.g., allowing irregular immigrants to stay in Italy), not only does Rivalry incorporate its Supremacy subfacet that resonates with the nativism component of PRR, but Narcissism is also closely related to envy (American Psychiatric Association, 1994)—the sentiment that mainly drives PRR voting. In Mayer et al. (2020), Narcissistic Rivalry positively predicted AfD support directly as well as via RWA and AIS, while Narcissistic Admiration was negatively related to PRR voting both directly and indirectly through AIS. Mayer et al. (2020) have shown that Rivalry positively predicted AfD support via AIS, and also through traditionalism among angry citizens. These studies apply a SEM framework based on assumptions about the causal ordering of the variables and assume that Rivalry is the antecedent of RWA, traditionalism, SDO, and AIS. Nevertheless, in previous studies that focus on the personality, ideology, and attitudinal predictors of PRR voting (e.g., Zandonella and Zeglovits, 2013; Aichholzer and Zandonella, 2016; Bakker et al., 2016), Agreeableness, a personality trait correlated with (disagreeable) Narcissistic Rivalry, remains a significant predictor after controlling for the effect of RWA. This suggests that anti-establishment sentiments (disagreeableness) and the host ideology (RWA and SDO) embody two distinct routes to the PRR. Therefore,

Research Question 3 (RQ3). Does Rivalry constitute a separate path from ideological variables (SDO, RWA, and traditionalism) in explaining PRR support?

Just as populist antagonism may activate disagreeableness and/or Rivalry, there may also be a congruence between Neuroticism and threat messages in PRR communication. Accordingly, low emotional stability and anxiety have already been linked to PRR support (Schoen and Schumann, 2007; Zandonella and Zeglovits, 2013; Obschonka et al., 2018). Moreover, the aforementioned studies foreshadow that the non-disagreeable route to PRR support may be characterized by a neurotic personality profile. As mentioned above, while disagreeableness was consistently associated with populist voting in Bakker et al. (2016, 2021) across samples, Neuroticism, right-wing ideology, and/or authoritarianism remained significant predictors in their regression analyses. Aichholzer and Zandonella (2016) corroborates the existence of this second pathway by demonstrating that Neuroticism predicts populist support mediated by RWA. Although Neuroticism is linked to envy through low self-esteem (Olson and Evans, 1999; Milić et al., 2023), unlike Narcissism, conceptually it is not a status-related personality trait. Its association with envy may be due to the strong correlation between Neuroticism and Vulnerability. Furthermore, while the negative correlation between Admiration and PRR vote (Mayer et al., 2020) suggests that Grandiosity may characterize rather non-populists than populists, it is reasonable to assume that economic Vulnerability may translate into vulnerable Narcissism at the personality level. Consequently, because both types of Narcissism are strongly related to status-concerns, SSTs might activate SSRE in both rivalrous and vulnerable narcissistic individuals. Since we had no data directly measuring Vulnerability, we used Neuroticism as a proxy variable.

Research Question 4 (RQ4). Is Neuroticism directly and positively related to PRR support over and beyond the effect of ideological variables (SDO, RWA, and traditionalism)?

In sum, previous studies in personality psychology suggest that there may be two distinct routes leading to PRR voting. Whereas disagreeableness is activated by anti-establishment messages, RWA may be linked to the host ideology of the PRR (Bakker et al., 2021). This latter component is also correlated with Neuroticism, which implies that this attitude may be activated by threat messages. As (1) the political sociology literature suggests that PRR support is predicted by status threat, (2) status-seeking is the most defining feature of the narcissistic personality, and (3) Narcissistic Rivalry is closely linked to disagreeableness, while Narcissistic Vulnerability to Neuroticism, the present study proposes that the two types of narcissistic traits constitute two distinct pathways linking status threat and PRR voting. Furthermore, we claim that the main affective mechanism behind this process is driven by SSRE. The conceptual model is presented in Figure 1.

As previously mentioned, disagreeableness may be consequential for PRR support because anti-establishment messages may activate anger and antagonism typical to the disagreeable personality. Similarly, the RADACT framework hypothesizes that PRR voting is explained by the activation of status-focused narcissistic traits by status concerns. Narcissistic individuals are characterized by a competitive worldview and vigilance for status threats (Abraham and Pane, 2016; Jonason and Ferrell, 2016; Jonason and Zeigler-Hill, 2018; Moshagen et al., 2018; Zeigler-Hill et al., 2020). They do not care as much about morality as they do about status (Cichocka et al., 2017), and status-seeking is considered their most defining motive (Grapsas et al., 2020). Competitive (and not dangerous) worldview mediated the effect of Rivalry on RWA and SDO, furthermore, it predicted dominance-, and prestige-based status-seeking strategies (Petersen et al., 2021b). As previously mentioned, Rivalry serves as a protection from realistic or imagined status threats through devaluing others (e.g., Back et al., 2013). Consequently, the RADACT framework suggests that as narcissistic individuals score high on trait envy and they are particularly concerned with social status, social status threats arise episodic SSRE in them. In other words, SSRE-inducing situations activate Rivalry leading to PRR voting.

Research Question 5 (RQ5). Is the association between Rivalry and PRR support is moderated by SSRE in such a way that the effect of Rivalry is larger for citizens experiencing higher SSRE?

Overall, our framework suggests that there are two distinct routes from SSRE to PRR voting: the authoritarian/vulnerable that may be related to the right-wing component, and the disagreeable/rivalrous to the anti-establishment element. Furthermore, according to the RADACT hypothesis, PRR support is most probably also predicted by the interaction between Rivalry and SSRE. Social status threat may potentially be the contextual factor that evokes SSRE and thereby activates the Rivalry-PRR link. Furthermore, although it is an unexplored area, Vulnerability may also be activated by the threat posed by potential status loss.

To the best of our knowledge, the German GESIS Panel is the only available database containing measures of both Narcissism and voting behavior. It is a probability sample of 4,400 German citizens who complete surveys every two months via a web-based or an offline-mode format (Bosnjak et al., 2018). We capture PRR support by the AfD vote in the 2017 German parliamentary elections. To reduce chances of endogeneity, variables measuring personality, ideology, and social status come from previous waves. As not all variables were assessed in each wave, the final sample contained 1,594 individuals. Nevertheless, we estimated three additional models as robustness checks (see Supplementary Figures S2–S4).4

Germany offers a valuable insight into the formation and consolidation of a PRR party. Unlike most of its Western European counterparts, Germany witnessed a delayed emergence of the populist radical right. While initially the AfD attracted conservative intellectuals with its economically liberal and Eurosceptic policies (Arzheimer and Berning, 2019), in 2015 an internal discord prompted the departure of moderate members, paving the way for a radical shift within the AfD (Dilling, 2018). During the so-called “refugee crisis” in 2015, the AfD had already adopted fiercely nativist and anti-elitist stances, aligning itself as a full-fledged PRR party (see Rooduijn et al., 2023). The 2017 federal elections brought about a significant breakthrough for the AfD (Arzheimer and Berning, 2019), which surged from less than 5% of the vote in 2013 to over 12% in 2017. On the whole, there is a broad consensus that by 2016, the AfD could already be classified as a PRR party (Van Hauwaert and Van Kessel, 2018; Arzheimer and Berning, 2019; Weisskircher, 2020). As such, it bears clear similarities with other Western European PRR parties (Donovan, 2020). Consequently, our findings might potentially be generalized to parties such as the Partij voor de Vrijheid in the Netherlands, the Vlaams Belang in Belgium, the Rassemblement National in France, or the Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs in Austria. It is important to emphasize, however, that although the members of the populist radical right party family have a lot in common (i.e., their nativism, authoritarianism, populism and Euroscepticism), there also exist important differences between them. Moreover, the voter bases of these parties can also differ across countries (Rooduijn, 2018). Hence, even though we have good reasons to expect that we can generalize our findings to PRR supporters more broadly, this remains an open empirical question. We therefore recommend future investigations to replicate this study in other contexts.

We captured PRR support by examining the AfD vote in the 2017 parliamentary elections. The dichotomous variable was coded one if someone voted for the AfD as a party or for the party's direct district candidate, and zero if none of the votes was cast for the AfD. Narcissism was assessed with the 18-item Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire (NARQ; Leckelt et al., 2018) in 2016. It contains two facets: Admiration (e.g., “I enjoy my successes very much.”), and Rivalry (e.g., “I want my rivals to fail”). Social Status-Related Envy was measured by envy felt in 2015 toward other people's creativity (job-related), things other people can buy (income-related), and residential area. One example is “It is hard to bear when other people are more intelligent than I am.” Socio-Economic Status was captured by four variables. Education was measured on a 4-point scale (1 - secondary school certificate or below, 2 - intermediary school, 3 - university of applied sciences, 4 - university degree), personal income level with 15 categories (1 - under 300 euro/month, 15 - over 5,000 euro/month), while distance of residential area from big city with a 6-point scale (1 - in the city enter, 6 - more than 60 km from a city center). All variables were registered in 2017. The 10-item Big Five questionnaire (BFI-10; Rammstedt and John, 2007) was registered in 2016 with 5-point scales (1 - totally disagree, 5 - totally agree). It contains two items for each Big Five factor, consequently, it has been criticized for its low validity (Bakker and Lelkes, 2018). However, the 30-item measure in the GESIS panel was registered after the 2017 elections, hence its use would compromise the exogeneity of the findings. We have nevertheless conducted several robustness checks based on the 30-item measure. Political ideology was assessed in 2016 with the SDO scale (4 items, e.g., “It is useful for society if some groups in the population are superior to others.”, 1 - fully disagree, 4 - totally agree), RWA scale (3 items, e.g., “Well-established behavior should not be questioned.”), 1 - fully disagree, 4 - totally agree), and traditionalism (“It is important for him/her to preserve traditional values and convictions.”, 1 - Is not at all similar to me, 6 - Is very similar to me). Antagonism and Anti-minority sentiments were captured by three variables. Sentiments toward ethnic minorities were measured by two items. First, each respondent was asked about different emotions felt in relation to one of four minorities (foreigners or refugees or Sintis/Romas or Muslims). Anti-Immigrant Sentiment (AIS) was a measure of horizontal antagonism, calculated as the average of detest and contempt felt toward minorities (e.g., “I feel contempt for Sinti and Roma,” 1 - Fully disagree, 4 - Totally agree). Similarly, Perceived Immigrant Threat (PIT) was captured by the perceived threat posed by minorities (e.g., “Muslims who are living here threaten our freedoms and rights.”, 1 - Fully disagree, 4 - Totally agree). Vertical antagonism was assessed my Anti-elitism. It was captured by two items (e.g., “In general, politicians try to represent the people's interests.”, 1 - Totally agree, 4 - Fully disagree).

To (1) map the complex relationship between the variables and to (2) compare the association between Narcissism and PRR support at different levels of social status, we estimated psychological networks. These models have been applied in personality (e.g., Costantini et al., 2015) and social (e.g., Dalege et al., 2016) psychology. They are less often used, however, in political science (for an example, see Brandt et al., 2019). Psychological networks are abstract models comprising of nodes representing variables and edge weights corresponding to statistical relationship between them (Epskamp et al., 2017). If the variables under interest follow a multivariate Gaussian distribution, partial correlation networks are estimated (e.g., Borsboom and Cramer, 2013). In this study we use mixed graphical models (MGM) that are capable of estimating the joint distribution of different types of variables (e.g., Gaussian, categorical, count). Accordingly, weights represent the respective measures of association depending on the variable type (e.g., logistic regression coefficients for binary variables) over and beyond the effect of all other nodes. To build the network model, nodewise regressions are run with each node as a dependent variable. Consequently, each edge is estimated twice and edge weights represent the average of these two estimates. Although coefficients are estimated for the unidirectional effects, confidence intervals are constructed only around the average values.

Edge weights (e.g., in the case of normally distributed variables, partial correlations) are closely related to coefficients in multiple regression models. However, unlike in regression modeling, in network analysis, the role or order of variables in a chain (e.g., independent, mediator, dependent) is not predetermined. As edges speak for conditional independence relationships, the lack of an edge between two nodes means that there is no association between two variables if one controls for all the other variables. By contrast, a network where variables X and Y are not directly related, but are indirectly connected by Z (X-Z-Y), suggests that X and Y are correlated, but any predictive effect between them is mediated by Z. In this sense, psychological networks detect the (direct and indirect) predictors of all variables instead of pre-specifying their roles. In other words, they are better tools to estimate predictive mediation than multiple regression analysis (Epskamp et al., 2017, 2018).

Due to sampling variation, network edges are rarely zero. While multiple testing/correction is a widely used technique to mitigate the occurrence of these false positives, it runs the risk of compromising statistical power. An alternative to remove spurious correlations is the “least absolute shrinkage and selection operator” (LASSO; Tibshirani, 1996) that maximizes the sum of absolute correlations. As a result, compared to a non-regularized network, all parameter estimates decrease; small ones become exactly zero and so the network becomes sparser. To maximize the number of true positive edges while minimizing the number of false positive ones, multiple networks are estimated, and model selection is carried out based on a certain criterion. In this study, the Expected Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC; Chen and Chen, 2008) was used, which has been shown to perform especially well in retrieving the true network structure (Foygel and Drton, 2010; Van Borkulo et al., 2014; Barber and Drton, 2015).

For model estimation, the bootnet package was used (Epskamp et al., 2017), edge weights were estimated by 1,000 bootstrap samples. By using regularization as model selection, the usual interpretation of confidence intervals (CIs) would run the risk of double thresholding (Epskamp and Fried, 2018). Hence, after the visual inspection of the width of the CIs, the proportion of bootstrap cases where the given estimate was zero (prop0) were reported. For the moderation analysis, CIs were estimated.

In the first part of the analysis, four models were estimated hierarchically. The first contained the binary PRR variable, the Big Five traits, and the main ideological variables (SDO, RWA, and traditionalism). In the second, the two Narcissism facets (Admiration and Rivalry) were added. The third one also contained all objective and subjective status measures, and in the fourth, full network, measures capturing anti-minority attitudes and anti-elitism attitudes were also included. In the second part of the analysis, the second network was re-estimated at low and high levels of the status variables; subjective status (SSRE) was calculated by the mean of the four envy variables, while objective status was by the mean of the four SES variables. The SSRE moderator was coded zero if an individual experienced no envy and one otherwise. For the objective status variables, we used median split.

To summarize, the networks represent conditional dependencies between variables: if two nodes are connected by a third node, that means that their shared variance is explained by this third variable. For instance, if Agreeableness and PRR voting are connected only through Rivalry, it means that the effect of Agreeableness on PRR is mediated by Rivalry (hence, the mechanism between Agreeableness and PRR is explained by Rivalry). Similarly, if SSRE and PRR voting are connected through Rivalry, that means that those envious citizens vote for the PRR who score high on Rivalry. Nodes are often called interactions between variables as well (Haslbeck and Waldorp, 2015), because they represent the co-occurrence of the two variables; in the latter case, the co-occurrence of SSRE and Rivalry as well as that of Rivalry and PRR voting. If there is another path between SSRE and PRR, for instance through RWA, then the relationship between SSRE and PRR voting is explained by two independent mechanisms: either by Narcissism or by RWA. It is important to mention that directionality cannot be inferred from the graphs, so in this example, it is possible that Rivalry leads to SSRE for some people and to PRR voting for others. Or, alternatively, that SSRE makes people rival each other, and this increases their willingness to vote for the PRR (it is also possible that voting for the PRR makes people rival each other and this increases their SSRE). Hence, the main point of this study is not to establish causal relationships, but to explore if two variables are directly or indirectly connected, and in the second case, to explore which variables play a role in the indirect relationship. The average of the association between variables X and Y will be reported as βx−y, along with the proportion of bootstrapped edge weights that are non-zero (prop0). In the second part of the analysis, point and interval estimates will be reported between Rivalry and PRR voting at the different levels of SSRE. The thickness of an edge represents the relative strength of the association between two variables. Blue edges show positive associations and red edges demonstrate negative ones.

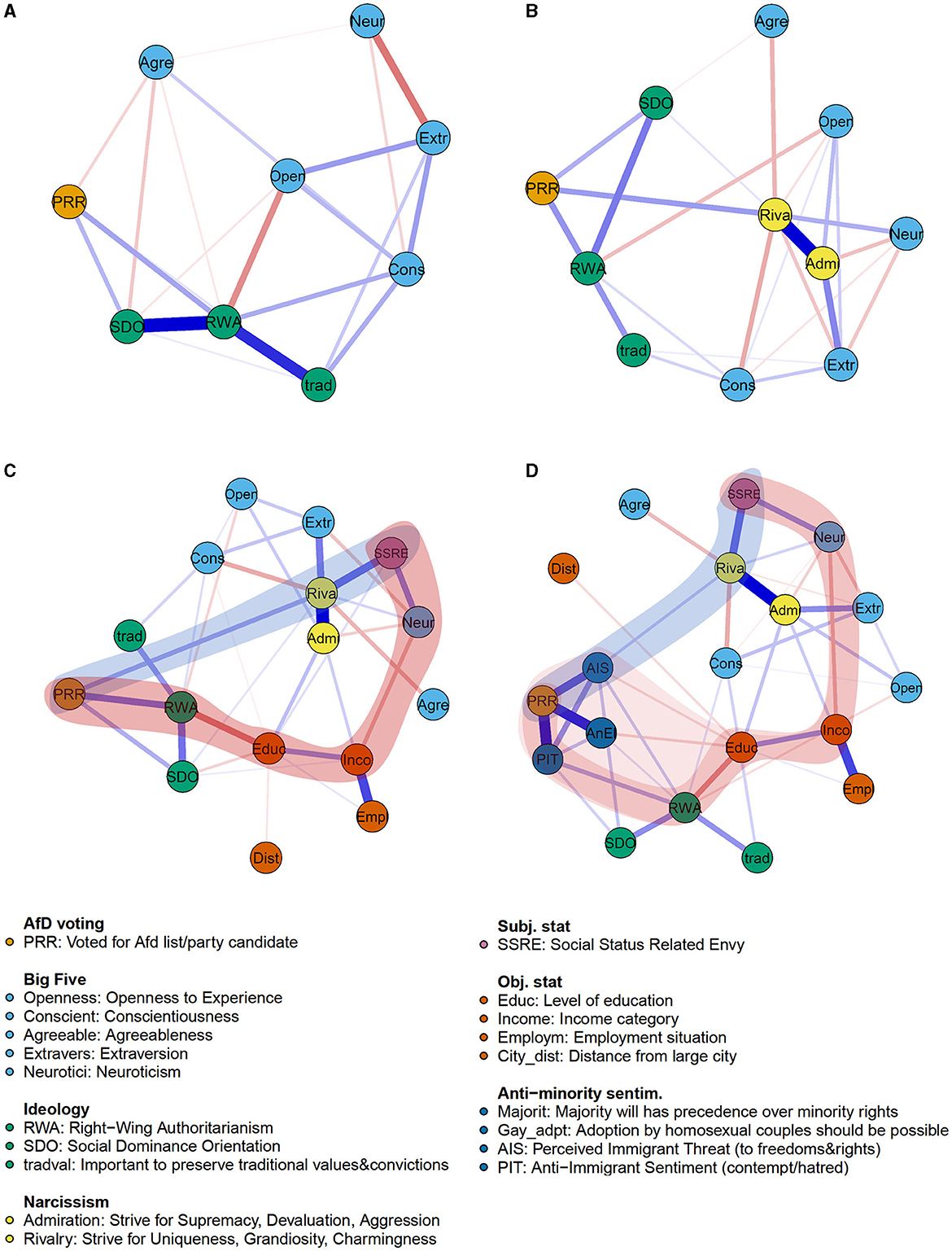

Figure 2 shows the four steps of the network construction. Figure 2A confirms previous findings linking Agreeableness to PRR support (βAgr−PRR = −0.06, prop0 < 0.01), representing a second path to the PRR next to the ideological variables (βRWA−PRR = 0.10, prop0 = 0;βSDO−PRR = 0.09, prop0 = 0). Figure 2B shows that Rivalry fully mediates the relationship between Agreeableness and PRR voting, although there is some minor indirect association through SDO as well (βAgr−Riv = −0.16, prop0 = 0, βRiv−PRR = 0.21, prop0 = 0.04, βAgr−SDO = −0.03, prop0 = 0.28). This network implies that PRR voting is founded on three pillars: RWA (βRWA−PRR = 0.23, prop0 = 0), SDO (βSDO−PRR = 0.17, prop0 = 0.3), and Rivalry (even though RWA and SDO are strongly correlated; βRWA−SDO = 0.27, prop0 = 0). Therefore, we can answer RQ2 and RQ3 in the affirmative: Rivalry mediates the effect of disagreeableness and it constitutes a path separately from the ideological variables. However, RQ4 is answered in the negative: there is no direct relationship between PRR support and Neuroticism (a proxy for Vulnerability).

Figure 2. Four steps of the network estimation (two paths highlighted). (A) Big Five personality, Ideology, and PRR support. (B) Narcissism, Big Five personality, Ideology, and PRR support. (C) SES, SSRE, Narcissism, Big Five personality, Ideology, and PRR support. (D) Antagonism, SES, SSRE, Narcissism, Big Five personality, Ideology, and PRR support.

To better understand the role of these three pillars among citizens from different voter segments, we estimated the second model not only for the PRR (proportion of AfD voting: 10.7 %), but also for the Populist Radical Left (PRL proxied by die Linke voting, 12.5%), the Mainstream/Moderate Right (MMR proxied by CDU vote, proportion: 41.4 %), and the Mainstream/Moderate Left (MML proxied by SPD vote, proportion: 28.8 %). Supplementary Figure S1 demonstrates that Narcissistic Rivalry is specific to the PRR. MMR is positively, while MML is negatively associated with RWA (and SDO), suggesting that mainstream voters differ along traditional ideological variables. The anti-establishment component on the right is Rivalry (Thriving for Supremacy, Devaluation, and Aggression), while on the left it is Openness to Experience (interest in art, having an active imagination).

When adding variables measuring objective and subjective status (Figure 2C), one can identify two paths between SSRE and PRR: one through Rivalry (βSSRE−Riv = 0.27, prop0 = 0;βRiv−PRR = 0.15, prop0 = 0.17, highlighted in blue), and the other through Neuroticism and objective SES variables (βSSRE−Neu = 0.20, prop0 = 0;βNeu−Inc = −0.12, prop0 = 0.001;βInc−Edu = 0.18, prop0 = 0;βEdu−RWA = −0.22, prop0 = 0;βRWA−PRR = 0.23, prop0 = 0.004, highlighted in red). Figure 2D includes, in addition, measures of antagonism (PIT, AIS, and anti-elitism). RQ1 is answered in the negative as there is no direct relationship between SSRE and PRR support. However, the figure demonstrates that SSRE is directly related to both Rivalry (βSSRE−Riv = 0.27, prop0 = 0) and Neuroticism (βSSRE−Neu = 0.18, prop0 = 0). More specifically, SSRE is connected to PRR voting in two distinct pathways (blue and red routes in the graph). First, through the Neuroticism-income-education-RWA-PIT path (βNeu−Inc = −0.12, prop0 = 0;βInc−Edu = 0.17, prop0 = 0;βEdu−RWA = −0.18, prop0 = 0;βRWA−PIT = 0.13, prop0 = 0;βPIT−PRR = 0.37, prop0 = 0). It should be noted that while RWA is the strongest predictor of PIT, both the effect of RWA and that of education on PRR support are mediated by anti-elitism and AIS, albeit these effects are of a modest magnitude. (βRWA−AnEl = 0.07, prop0 = 0.11;βRWA−AIS = 0.09, prop0 = 0.01;βEdu−AnEl = −0.07, prop0 = 0.08;βEdu−AIS = −0.06, prop0 = 0.3). Second, the Rivalry-AIS path (βRiv−AIS = 0.08, prop0 = 0.06;βAIS−PRR = 0.28, prop0 = 0.01). Interestingly, the latter path is linked to low Conscientiousness (βRiv−Con = −0.13, prop0 = 0), while the former one to somewhat low Openness (βRWA−Ope = −0.07, prop0 = 0.15) and high Conscientiousness (βRWA−Con = 0.07, prop0 = 0.24) – although these latter two associations do not seem robust.

Robustness checks were run for an alternative measure of Big Five personality and for the 2021 elections as well. Their results are largely consistent with the outcomes of the primary analysis, although in two of the four networks (1) Rivalry does not fully mediate the effect of Agreeableness on AIS and on PRR voting (although the leftover effect is weak), and (2) traditionality has direct effect on PRR support.

Overall, when considering only personality- and ideology-related variables, there is a direct relationship between Rivalry and PRR voting. However, once adding status- and antagonism-related constructs, it becomes clear that this association is mediated by detest and contempt felt toward ethnic minorities. Furthermore, the relatively wide confidence intervals (please see Supplementary Figure S5) suggest that the Rivalry-PRR effect is heterogeneous. It implies that the Rivalry-PRR support edge may be strong for some individuals while weak for others.

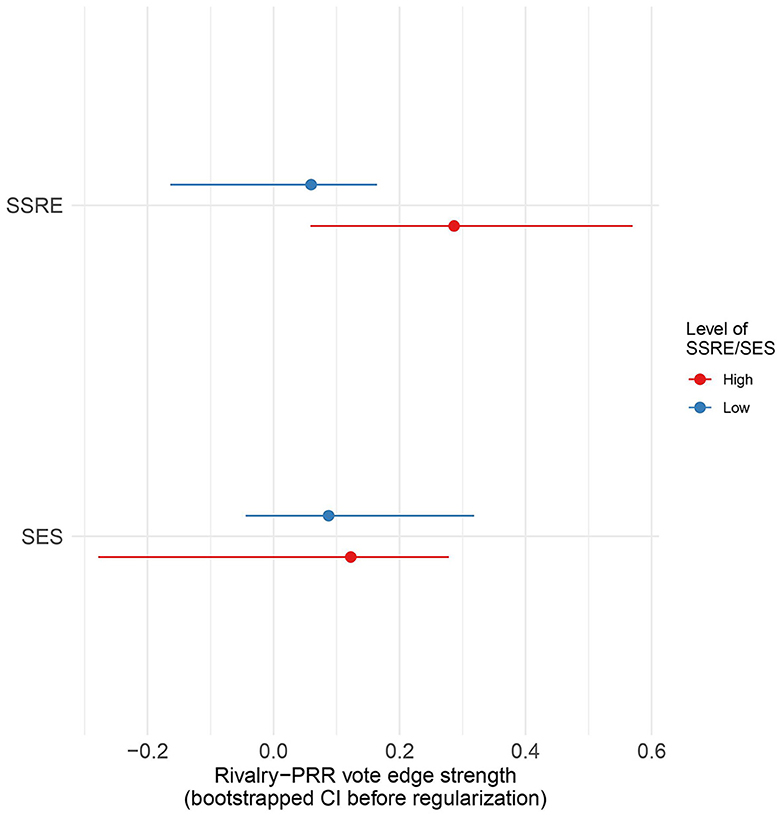

The RADACT hypothesis suggests that SSTs activate status-focused (narcissistic) traits in explaining PRR voting. Therefore, we tested whether the edge is stronger for people scoring high on SSRE compared to those who score low. Figure 3 represents the point- and interval estimates for the Rivalry-PRR edge weight at high and low levels of SSRE. The plot suggests that while lower objective status does not amplify the effect of Rivalry on PRR voting, higher SSRE does. This indicates that the connection between Rivalry and PRR support only exists among those who score high on SSRE (please see Supplementary Figure S6 for the high and low SSRE networks). A contrast estimate to test whether the difference in edge weight between high and low SSRE is greater than the difference in edge weight between low and high objective status confirmed this finding (β = −1.42, SE = 0.18, z = −7.85, p < 0.0001).5

Figure 3. Point and interval estimates for the Rivalry-PRR voting edge for low vs. high level of SES (objective status) and SSRE (subjective status).

The analysis provides positive answers to most of the research questions. First, the previously established relationship between disagreeableness and PRR voting is fully mediated by Rivalry (RQ2). Second, the association between Rivalry and PRR voting remained significant after controlling for ideology and other personality traits (RQ3). Adding objective status and SSRE as well as antagonism-related variables demonstrated that the association between Rivalry and PRR support is mediated by AIS, while the one between RWA and PRR is principally by PIT. Nevertheless, both AIS and anti-elitism play a role in this second route. Third, neither SSRE (RQ1) nor SES are directly related to PRR voting: while the former is connected through Rivalry and AIS, the latter is through RWA and PIT. The findings imply that objective status threats may lead to PRR voting only for citizens who are authoritarian and fearful of minorities, while SSRE does for individuals scoring high on Rivalry and AIS. Moreover, SSRE amplifies the relationship between Rivalry and PRR voting, presenting preliminary evidence for the RADACT hypothesis (RQ4). SES, however, does not moderate this relationship. In sum, our findings suggest that there are two profiles of PRR voters: (1) a profile of neurotic (vulnerable), authoritarian citizens with low levels of SES, who perceive ethnic minorities as a threat and who do not trust the elites, and (2) a profile of disagreeable/rivalrous voters who score average on SES and who feel contempt and detest toward ethnic minorities.

The present study set out to integrate models from political sociology and political psychology to explore different pathways to PRR voting. While studies from sociology propose that objective and subjective status threats fuel PRR support (cf. economic and cultural grievance theories), the personality psychology literature foreshadows two voter profiles: one characterized by disagreeableness and Narcissistic Rivalry, and the other by Neuroticism and Authoritarianism (Zandonella and Zeglovits, 2013; Aichholzer and Zandonella, 2016; Bakker et al., 2016, 2021). We argued that envy—more specifically, social status-related envy (SSRE)—is the construct that bridges these two approaches. Because Narcissism and Neuroticism are characterized by high dispositional envy (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Olson and Evans, 1999; Krizan and Johar, 2012; Lange et al., 2016; Milić et al., 2023), they get triggered by status threats (Aristotle, 2007; Crusius and Lange, 2017; Bolló et al., 2020), and are, consequently, related to PRR support (Da Silva and Vieira, 2019; Koenis, 2021). Hence, we theorized that social status threats activate episodic SSRE in individuals high in disagreeable/rivalrous and neurotic/vulnerable narcissism (and hence also in dispositional SSRE), which, in turn, leads to PRR voting.

We made use of psychological network modeling. By visualizing conditional dependency relationships, our models revealed that: (1) SSRE is directly associated with two constructs: Narcissistic Rivalry and Neuroticism; (2) Narcissistic Rivalry predicts AfD voting over and beyond RWA, SDO, and the Big Five traits, and fully mediates the (previously established) relationship between Agreeableness and PRR voting (Bakker et al., 2016); (3) middle-class PRR supporters tend to score high on Rivalry and Nativism, while PRR voters with lower SES tend to be neurotic, potentially vulnerable, and they constitute the authoritarian-populist-nativist path; (4) it is envy about others' social status (SSRE) rather than objective SES that activates Narcissistic Rivalry in explaining PRR support; and finally (5) in line with previous findings about the marginal relevance of SDO in explaining PRR voting (Aichholzer and Zandonella, 2016), Rivalry is the second most important personality-related predictor of AfD support after RWA. These findings suggest that Narcissistic Rivalry may be constitutive rather for the “populist radical” than for the right-wing component of the PRR. Furthermore, Rivalry seems to be specific to PRR voters as unlike RWA and SDO, it was not linked to the support for any other party family (PRL, MMR, MML). All in all, there seem to be two profiles of PRR voters, both of them rooted in dispositional SSRE.

Based on our findings, we propose a Bifurcated Model of Status-Deprived Narcissistic Right-Wing Populism (BiSNaRP; see Figure 4), representing two paths spanning between SSRE and PRR support. The Wealth Paradox (Mols and Jetten, 2017) claims that negative attitudes toward minorities can be explained either by status anxiety (rooted in unstable status relations) or by entitlement (grounded in status relations that are perceived to be legitimate). The two routes resonate with these findings: whereas for lower-class citizens, ethnic threat is the strongest proximal affective predictor of PRR voting (status anxiety), for middle-class PRR voters SSRE predicts Rivalry (entitlement) and ethnic hatred, and neither anti-elitism nor PIT plays a key role in their voting behavior. Middle-class PRR voters may feel entitled to their dominant group status without experiencing realistic threats.

The BiSNaRP suggest that SSRE gets transformed into ethnic threat (PIT) and hatred (AIS) in distinct ways. The first path implies that economic vulnerability (low SES) might translate to Neuroticism (and possibly to Vulnerable Narcissism). This route has a typical conservative profile (rather high level of Conscientiousness and low level of Openness to Experience). Accordingly, for them, RWA is the primary mediator between low SES and PRR voting. More specifically, low educational attainment appears to be the underlying cause behind both economic vulnerability and RWA. RWA, in turn, is linked to PRR support through PIT. It corroborates previous findings detecting RWA, SDO, and PIT as mediators between low educational attainment and PRR support (Aichholzer and Zandonella, 2016), and studies linking education and income to authoritarian obedience and cultural right-wing attitudes (Jost and Napier, 2011). However, the effect of education on PRR is also mediated by anti-elitism and AIS. Consequently, the first path is characterized by authoritarian right-wing populism: anti-elitism (vertical antagonism or populism), AIS (horizontal antagonism or Nativism), and RWA. First, right-wing views may serve as a psychological coping with economic threats (e.g., uncertainty-threat model of political conservativism; system justification theory; Jost et al., 2003a,b, 2007, 2018) when citizens aim to reduce the cognitive dissonance between their economically vulnerable situation and their resistance to change (resulting from their already unstable situation). Second, in our networks, education mediates the effect of objective residential status on anti-elitism. Furthermore, the 2021 data demonstrate that whereas the effect of RWA on PRR support is mediated by PIT (coping with threat), that of traditionalism is mediated by anti-elitism. It may suggest that uneducated rural citizens do not feel their traditional values represented by the (urban) elite. Accordingly, citizens with lower educational attainments tend to resist cultural diversity (dereification theory; e.g., Van der Waal and De Koster, 2015) and low cultural capital predicts authoritarianism (Houtman, 2017), gender conservatism (Houtman, 2017), and ethnocentrism (Van der Waal and De Koster, 2015). In other words, one might speculate that by framing economic deprivation (a realistic threat) in cultural terms, the PRR messages activate ethnic threat and populist attitudes among lower-class citizens (similar in Harteveld et al., 2022, for lower-class/rural citizens).

The second path incorporates middle-class citizens for whom the SSRE-PRR support is mediated by Rivalry and AIS. These voters score low on Conscientiousness and Agreeableness, which also resonates with the Need for Chaos (NfC) literature. People high on NfC feel marginalized by society and tend to view inversion of the establishment as opportunity to gain social status. NfC is most prevalent among middle-class citizens, and it is highly correlated with both right-wing populist attitudes and dark personality traits, but still distinct from both (Petersen et al., 2018; Arceneaux et al., 2021). People high on NfC score low on trait Agreeableness, Emotional Stability, and Conscientiousness. Accordingly, in our networks, Neuroticism is negatively, while Agreeableness and Conscientiousness are positively and directly related to Rivalry.

Narcissistic Rivalry consists of three components: Devaluation (e.g., “Other people are worth nothing.”), Aggressiveness (e.g., “I often get annoyed when I am criticized”), and Strive for Supremacy (e.g., “I enjoy it when another person is inferior to me.”). It stands to reason to assume that this pathway captures the sense of entitlement (due to supremacy) over the (devalued) minorities—in other words, the nativist, supremacist (e.g., xenophobic, homophobic, sexist) stance. As these citizens have average SES, encounter no PIT, and are not dissatisfied with the elites, they may be the winners of globalization who simply feel entitled to their dominant group status. For them, cultural frames may activate Nativism (for more about entitlement and anti-minority sentiments see Bell, 1978, 1980; Grubbs et al., 2014). Consequently, middle-class PRR voters experience SSRE without actually being under realistic threat and their dispositional envy transforms into ethnic hatred. Hate is a composite emotion encompassing anger, contempt, and disgust (Sternberg and Sternberg, 2008; Martínez et al., 2022). Both horizontal and vertical antagonism may stimulate hate since the moral nature of PRR in- and outgroup distinction serves to exclude the undesirable members of society (Abts and Rummens, 2007). In other words, middle-class hate is a consequence of how the PRR worldview frames societal threats.

Rivalry/entitlement is considered to be a maladaptive self-enhancement strategy where narcissistic individuals cope with ego threats through exploiting and devaluing others (Miller and Campbell, 2008; Cater et al., 2011). In our models, these ego threats are captured by envy felt toward others' linguistic expression, creativity, residential area, and buying behavior (despite being rather highly educated, urban, middle-class citizens). The RADACT model hypothesizes that SST causes (episodic) envy in narcissistic people that activates Rivalry which, in turn, leads to PRR voting. Our study confirms this hypothesis by showing that Rivalry is associated with PRR support only in the presence of envy. Furthermore, this association is contingent only on subjective feelings about someone's status and is independent of objective status (SES). Similarly, Vulnerability may be activated by objective status threats. However, before presenting paths for future research, we discuss the implications of our findings.

Our findings substantially contribute to our understanding of the psychological roots of the PRR by highlighting the distinction between proximal and distal predictors. While SSRE seems to be the ultimate drive of PRR support and (horizontal and vertical) antagonism, as well as by PIT are identified as direct predictors, the role of constructs measuring personality and ideology is more complex than formerly assumed. Unlike past research that, often due to methodological limitations, have not questioned that ideology mediates the effect of personality on political choice, we have shown that personality traits can act independently of ideological variables. Furthermore, whereas Bakker et al. (2016) assumed that the disagreeableness-PRR support association is explained by anti-establishment sentiments (vertical antagonism), in our sample it captures the nativist component (horizontal antagonism). While the authors also claim that the disagreeableness-PRR support relationship is rooted in negativity and distrust, our results offer a more nuanced explanation of this mechanism. It is not simply the congruence between an antagonistic worldview and an antagonistic personality, but it is status threat, status-related personality traits, and the associated envy that underlies this opposition. The superior explanatory power of dark personality traits over disagreeableness resonates with Bergh and Akrami (2016) who found that once controlling for Honesty-Humility, Agreeableness stopped predicting racism and sexism.

The BiSNaRP may offer a potential psycho-social explanation for how PRR forces can unite lower and middle-class citizens. The “culture war” (Bob, 2012) rhetoric adopted by the PRR movement generates ethnic threat as well as a sense of neglect among lower-class (rural) individuals who experience unstable status relations and who do not feel represented by the elites. Our results suggest that, the same message does not induce anti-elitist sentiments, rather a sense of nativist entitlement among middle-class citizens who might not want to put effort into safeguarding their “well-deserved” position. Thus, PRR messages might activate episodic envy in vulnerable people facing realistic status loss as well as in rivalrous individuals experiencing SST. However, the generalizability of these findings should be tested on samples from other countries.

Finally, the role of competitive and rivalrous emotions seems to be crucial in explaining PRR voting. While the economic grievances of the “losers of globalization” can be seen as a general moral concern about undeserved inferiority, the middle class expresses a personal concern about subjective inferiority while belonging to the “winners of globalization” (Da Silva and Vieira, 2019). Whereas the former group may develop anti-elitist sentiments (which may be present among PRL voters, too) and authoritarian tendencies due to their unjust position, the latter group develops hatred out of pure rivalry toward (ethnic) minority groups who cannot be blamed for societal injustices. This nativist component seems to be unique to PRR constituencies and might be originated in competitive norms and the propagation of (meritocratic) individualistic norms.

Our findings must be interpreted in the light of potential limitations. First, the BiSNaRP theorizes that both Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism are characterized by heightened concern for social status and SSRE. Nevertheless, due to lacking data, we could not directly measure Vulnerable Narcissism and we had to proxy it with Neuroticism. However, the fact that Rivalry is directly related to Admiration and Neuroticism (which are negatively related to each other) suggests that Neuroticism captures a vulnerable cluster. Nevertheless, future studies should corroborate our findings with direct measures of Vulnerability. Second, this exploratory study is limited to German data, and as such, it is context-dependent. We call for future replications in other cultural and societal contexts that confirm, disprove, or elaborate on the role and interrelation of the different variables in the BiSNaRP.

Third, although psychological network models are of estimating conditional dependencies between multiple variables, they do not test causal relationships. Drawing from the findings of the correlational study, it is not possible to disentangle whether envy-inducing status threats genuinely activate narcissistic tendencies, or if individuals with such personality traits are inherently predisposed to heightened experiences of envy. Consequently, the RADACT hypothesis should be confirmed by future experiments that manipulate subjective status perceptions and test if SST amplifies the effect of narcissistic traits on the propensity to vote for PRR parties.

Finally, further studies may explore whether status-seeking and envy can be modulated by contextual factors. Envy is a competitive emotion (Aristotle, 2007; Da Silva and Vieira, 2019), Narcissism is related to competitive worldview (Jonason and Zeigler-Hill, 2018), and RWA is positively related to competitive/vertical and negatively to communal/horizontal societies (Kemmelmeier et al., 2003). Furthermore, the concept of social status in (vertical) individualist cultures is related to power (control over resources), while in (horizontal) collectivist cultures to prosocial behavior. Consequently, it is possible that manipulating norms about competition may attenuate the activating potential of SSTs on SSRE.

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.gesis.org/en/services/finding-and-accessing-data.

DK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MR: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. GS: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We would like to thank the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (VI.Vidi.201.103) for the funding we received.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1401758/full#supplementary-material

1. ^While previous studies have examined the association between PRR support and collective Narcissism (e.g. Marchlewska et al., 2018; Golec de Zavala and Keenan, 2021), we focus on individual Narcissism. To our knowledge, only the two papers cited here investigate the association between PRR support and this type of Narcissism.

2. ^Furthermore, grandiosity is negatively linked to the industriousness sub-facet of Conscientiousness and both types of Narcissism are positively associated with the intellect sub-facet of Openness to Experience (Zajenkowski and Szymaniak, 2021).

3. ^While authentic pride is elicited by one's achievement, hubristic pride is related to an inflated sense of self-esteem rather than to an eliciting event (Carver et al., 2010).

4. ^We did not want to violate endogeneity, hence, we used the aforementioned model as baseline. However, our motivation to run robustness checks was twofold. First, we wanted to run the analysis on more recent data, hence we estimated two networks with the 2021 votes as dependent variables. However, SSRE was assessed in 2015, and 6 years difference seemed too much even for a trait variable. Second, we wanted to test our models with the most valid personality measures possible. Nevertheless, the 30-item Big Five inventory (BFI-30) was registered in 2017, after the elections. Ultimately, we estimated a network with (1) 2017 votes and BFI-30 assessed after the elections, (2) 2021 votes, BFI-30 assessed in 2017, Narcissism assessed in 2019, and SSRE assessed in 2015, and (3) 2021 votes, BFI-10 assessed and Narcissism assessed in 2019, and SSRE assessed in 2015.

5. ^Note that the same contrast estimate for the RWA-PRR support edge was not significant (β = −0.00, SE = 0.002, z = −0.272, p = 0.79). Hence, the relationship between RWA and PRR is probably not contingent on SSRE.

Abou-Chadi, T., and Kurer, T. (2021). Economic risk within the household and voting for the radical right. World Polit. 73, 482–511. doi: 10.1017/S0043887121000046

Abraham, J., and Pane, M. M. (2016). The role of narcissism and competitive worldview in predicting environmental apathy. Asian J. Qual. Life 1, 35–42. doi: 10.21834/ajqol.v1i1.33

Abts, K., and Rummens, S. (2007). Populism versus democracy. Polit. Stud. 55, 405–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00657.x

Aichholzer, J., and Zandonella, M. (2016). Psychological bases of support for radical right parties. Person. Indiv. Differ. 96, 185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.072

Algan, Y., Guriev, S., Papaioannou, E., and Passari, E. (2017). The European trust crisis and the rise of populism. Brook. Paper Econ. Activ. 2017, 309–400. doi: 10.1353/eca.2017.0015

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV, volume 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Arceneaux, K., Gravelle, T. B., Osmundsen, M., Petersen, M. B., Reifler, J., and Scotto, T. J. (2021). Some people just want to watch the world burn: the prevalence, psychology and politics of the “need for chaos”. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 376:20200147. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0147

Arzheimer, K., and Berning, C. C. (2019). How the alternative for Germany (AFD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013–2017. Elect. Stud. 60:102040. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.004

Autor, D., Dorn, D., Hanson, G., and Majlesi, K. (2016). Importing political polarization. Technical report. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Manuscript.

Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., and Denissen, J. J. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 105:1013. doi: 10.1037/a0034431

Bakker, B. N., and Lelkes, Y. (2018). Selling ourselves short? How abbreviated measures of personality change the way we think about personality and politics. J. Polit. 80, 1311–1325. doi: 10.1086/698928

Bakker, B. N., Rooduijn, M., and Schumacher, G. (2016). The psychological roots of populist voting: evidence from the united states, the netherlands and Germany. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 55, 302–320. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12121

Bakker, B. N., Schumacher, G., and Rooduijn, M. (2021). The populist appeal: personality and antiestablishment communication. J. Polit. 83, 589–601. doi: 10.1086/710014

Ballard-Rosa, C., Malik, M. A., Rickard, S. J., and Scheve, K. (2021). The economic origins of authoritarian values: evidence from local trade shocks in the united kingdom. Compar. Polit. Stud. 54, 2321–2353. doi: 10.1177/00104140211024296

Banting, K., and Kymlicka, W. (2013). Is there really a retreat from multiculturalism policies? New evidence from the multiculturalism policy index. Compar. Eur. Polit. 11, 577–598. doi: 10.1057/cep.2013.12

Barber, R. F., and Drton, M. (2015). High-dimensional ising model selection with bayesian information criteria. Electron. J. Statist. 9, 567–607. doi: 10.1214/15-EJS1012

Bartusevicius, H., van Leeuwen, F., and Petersen, M. B. (2020). Dominance-driven autocratic political orientations predict political violence in western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) and non-WEIRD samples. Psychol. Sci. 31, 1511–1530. doi: 10.1177/0956797620922476

Bell, C. C. (1980). Racism: a symptom of the narcissistic personality. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 72, 661.

Bergh, R., and Akrami, N. (2016). Are non-agreeable individuals prejudiced? Comparing different conceptualizations of agreeableness. Person. Indiv. Differ. 101, 153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.052

Besser, A., and Priel, B. (2010). Grandiose narcissism versus vulnerable narcissism in threatening situations: emotional reactions to achievement failure and interpersonal rejection. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 29, 874–902. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.8.874

Betz, H.-G., and Meret, S. (2013). “Revisiting lepanto: the political mobilization against islam in contemporary western Europe,” in Anti-Muslim Prejudice (London: Routledge), 104–125.

Betz, H. G. (1994). Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. New York, NY, US: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-23547-6

Bob, C. (2012). The Global Right Wing and the Clash of World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139031042

Bolló, H., Háger, D. R., Galvan, M., and Orosz, G. (2020). The role of subjective and objective social status in the generation of envy. Front. Psychol. 11:513495. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.513495

Bollwerk, M., Schlipphak, B., and Back, M. D. (2021). Development and validation of the perceived societal marginalization scale. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/3u8hn

Borsboom, D., and Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 91–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

Bosnjak, M., Dannwolf, T., Enderle, T., Schaurer, I., Struminskaya, B., Tanner, A., et al. (2018). Establishing an open probability-based mixed-mode panel of the general population in Germany: the gesis panel. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 36, 103–115. doi: 10.1177/0894439317697949

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Number 16. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511812507

Brandt, M. J., Sibley, C. G., and Osborne, D. (2019). What is central to political belief system networks? Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 45, 1352–1364. doi: 10.1177/0146167218824354

Bromley, P. (2009). Cosmopolitanism in civic education: exploring cross-national trends, 1970–2008. Curr. Issues Compar. Educ. 12:11438. doi: 10.52214/cice.v12i1.11438

Bucciol, A., Cavasso, B., and Zarri, L. (2015). Social status and personality traits. J. Econ. Psychol. 51, 245–260. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2015.10.002

Burgoon, B., Van Noort, S., Rooduijn, M., and Underhill, G. (2019). Positional deprivation and support for radical right and radical left parties. Econ. Policy 34, 49–93. doi: 10.1093/epolic/eiy017

Caprara, G. V., and Zimbardo, P. G. (2004). Personalizing politics: a congruency model of political preference. Am. Psychol. 59:581. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.581

Carver, C. S., Sinclair, S., and Johnson, S. L. (2010). Authentic and hubristic pride: differential relations to aspects of goal regulation, affect, and self-control. J. Res. Person. 44, 698–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.09.004

Cater, T. E., Zeigler-Hill, V., and Vonk, J. (2011). Narcissism and recollections of early life experiences. Person. Indiv. Differ. 51, 935–939. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.07.023

Chen, J., and Chen, Z. (2008). Extended bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika 95, 759–771. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asn034

Cichocka, A., Dhont, K., and Makwana, A. P. (2017). On self-love and outgroup hate: opposite effects of narcissism on prejudice via social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Eur. J. Person. 31, 366–384. doi: 10.1002/per.2114

Colantone, I., and Stanig, P. (2018). The trade origins of economic nationalism: import competition and voting behavior in western Europe. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 62, 936–953. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12358

Cordero, G., Zagórski, P., and Rama, J. (2022). Give me your least educated: immigration, education and support for populist radical right parties in Europe. Polit. Stud. Rev. 20, 517–524. doi: 10.1177/14789299211029110

Costantini, G., Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., Perugini, M., M ottus, R., Waldorp, L. J., et al. (2015). State of the art personality research: a tutorial on network analysis of personality data in R. J. Res. Person. 54, 13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.07.003

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226349251.001.0001

Crusius, J., and Lange, J. (2017). “How do people respond to threatened social status? Moderators of benign versus malicious envy,” in Envy at Work and in Organizations: Research, Theory, and Applications, 85–110. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190228057.003.0004

Czarna, A. Z., Zajenkowski, M., and Dufner, M. (2018). “How does it feel to be a narcissist? Narcissism and emotions,” in Handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies, 255–263. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_27

Da Silva, F. C., and Vieira, M. B. (2019). Populism as a logic of political action. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 22, 497–512. doi: 10.1177/1368431018762540

Dalege, J., Borsboom, D., Van Harreveld, F., Van den Berg, H., Conner, M., and Van der Maas, H. L. (2016). Toward a formalized account of attitudes: the causal attitude network (can) model. Psychol. Rev. 123:2. doi: 10.1037/a0039802

Dancygier, R. M., and Walter, S. (2015). Globalization, labor market risks, and class cleavages. Technical paper. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316163245.006

de Lange, S., van der Brug, W., and Harteveld, E. (2023). Regional resentment in the netherlands: a rural or peripheral phenomenon? Reg. Stud. 57, 403–415. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2022.2084527

Dilling, M. (2018). Two of the same kind? The rise of the AFD and its implications for the CDU/CSU. German Polit. Soc. 36, 84–104. doi: 10.3167/gps.2018.360105

Dobbin, F. (2009). Inventing Equal Opportunity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi: 10.1515/9781400830893

Donovan, B. (2020). Populist rhetoric and nativist alarmism: the AFD in comparative perspective. German Polit. Soc. 38, 55–76. doi: 10.3167/gps.2020.380104

Elchardus, M., and Spruyt, B. (2016). Populism, persistent republicanism and declinism: an empirical analysis of populism as a thin ideology. Govern. Oppos. 51, 111–133. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.27

Epskamp, S., and Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol. Methods 23:617. doi: 10.1037/met0000167

Epskamp, S., Rhemtulla, M., and Borsboom, D. (2017). Generalized network psychometrics: Combining network and latent variable models. Psychometrika 82, 904–927. doi: 10.1007/s11336-017-9557-x

Epskamp, S., Waldorp, L. J., M ottus, R., and Borsboom, D. (2018). The gaussian graphical model in cross-sectional and time-series data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 53, 453–480. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2018.1454823

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). “Politics without class: postindustrial cleavages in Europe and America,” in Continuity and Change in Contemporary Capitalism, 293–316. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139175050.012

Feenstra, R. C., and Hanson, G. H. (1996). Globalization, outsourcing, and wage inequality. Technical report. doi: 10.3386/w5424

Fitzgerald, J. (2018). Close to Home: Local Ties and Voting Radical Right in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/9781108377218

Foygel, R., and Drton, M. (2010). “Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 23.

Freis, S. D., and Hansen-Brown, A. A. (2021). Justifications of entitlement in grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: the roles of injustice and superiority. Person. Indiv. Differ. 168:110345. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110345

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., Raso, C., and Ha, S. E. (2011). Personality traits and participation in political processes. J. Politics. 73, 692–706. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611000399