- VUB Centre for Democratic Futures, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussel, Belgium

Why do men and women vote for the populist radical right? This question, which speaks to the phenomenon of the “radical right gender gap”, has been the topic of much scholarly interest. While previous studies refer to the role played by differences in political resources, attitudes, and socialization, this paper examines whether negative emotions towards the political system, and system-directed anger in particular, drive support for populist radical right parties differently for men and women. Drawing on the premise that populist radical right parties tend to appeal to angry voters, and given that acting upon anger is seen as an “agentic” trait, we expect that system-directed anger is more strongly associated with support for populist radical right parties among men compared to women. We test the hypothesis using original data from the RepResent voter survey organized in Belgium during the 2019 federal elections. In line with previous studies, we find that voters of the populist radical right party Vlaams Belang report high levels of system-directed anger. Men and women voters are similar in their display of this emotion, and contrary to our expectations, they are similar in how system-directed anger relates to vote choice as well. More than explaining gender differences in populist radical right voting, our findings confirm the idea that system-directed anger can incite women as well as men to cast a populist radical right vote.

1 Introduction

The debate on the rise of the populist radical right and the determinants for its success in national, local, and European politics has drawn large interest both within and outside academic scholarship. A consistent finding in this scholarship is the so-called gender gap in populist radical right voting. Studies have repeatedly found that men are, in general, more likely than women to cast a populist radical right vote. This gender gap has existed for several decades (Betz, 1994), although the size of the gap is known to vary across countries and between elections (Immerzeel et al., 2015; Mayer, 2015). However, the question of why this populist radical right gender gap exists has no easy answer. A large number of studies have formulated demand-side explanations, highlighting that the gender gap among voters is linked to differences between men and women in structural resources and political attitudes (Givens, 2004; Gidengil et al., 2005; Spierings and Zaslove, 2017). Key factors explored in these studies include the gendered division of labor (Givens, 2004), anti-immigration attitudes (Immerzeel et al., 2015), and shifts in cultural values (Ignazi, 2003; Inglehart and Norris, 2003; Off, 2023). Other studies have focused on supply-side explanations, showing that political opportunity structures such as party types, electoral contexts, and communication styles can help explain why some people are drawn to populist radical right parties (Harteveld and Ivarsflaten, 2018; Harteveld et al., 2019). Yet, combined results remain inconclusive, and questions about the precise factors that render the populist radical right seemingly more attractive to men continue to exist.

In this paper, we aim to test an alternative hypothesis that gender differences are related to emotions. Following several crises which European states are facing (e.g., economic, demographic, pandemic, and democratic legitimacy crises), scholars of populist radical right voting have (re)focused on how concerns like public distrust, perceived threats towards the “other”, and feelings of resentment—all part of the populist radical right’s rhetoric—shape the electoral considerations of voters (Wodak, 2015; Bustikova, 2019; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). This new research track focuses on explaining whether, how, and why emotions such as anger and fear inform voters’ attitudes towards and decisions to vote for a populist radical right party (e.g., Marcus et al., 2000; Vasilopoulos et al., 2019 on France; Rico et al., 2017 on Spain; Erisen and Vasilopoulou, 2022 on Germany, Netherlands and the United Kingdom).

Existing studies on emotions, however, do not relate their findings directly to gender differences in populist radical right voting. In this paper, we therefore examine whether anger motivates support for populist radical right parties differently for men and women. There are good reasons to expect that affective explanations for populist radical right voting may have a gendered dimension. Relying on social role theory and social appraisal theory, we assume that women and men, although they may experience and express similar levels of anger, will regulate these emotions differently (Evers et al., 2011). Even though voting is done in private due to ballot secrecy, it does take place in the public sphere as an act of public participation. Additionally, vote choice is often the subject of political discussion within one’s social network (Gerber et al., 2013; Santoro and Beck, 2017) and may have social implications as vote choices are often shared with others (Gerber et al., 2012). Hence, the public expression of one’s anger through voting holds potentially more negative social implications for women than for men. As a result, women may be less likely than men to translate their anger into a populist radical right vote. The latter also speaks to recent public debates on the role of “angry white men” in populist radical right voting. Academics and journalists have commented regularly on whether and how “angry white men” acted as driving forces behind the recent successes of populist radical right parties (e.g., Ford and Goodwin, 2010; Pease, 2021). The underlying assumption is that (white, lower educated or working class) men may feel threatened by deep economic and cultural changes in society, and may feel politically alienated and disillusioned, which the populist radical right preys on. Hence, feelings of anger and resentment towards traditional political actors and institutions would primarily be expressed politically by men. These expectations, however, require more empirical scrutiny (see also Setzler and Yanus, 2018). In this paper, we therefore take the previous indications as a starting point to study (1) to what extent emotions, in particular feelings of system-directed anger (i.e., anger directed at the political system), explain populist radical right voting among men and women to the same extent, and, consequently, (2) whether the populist radical right vote is indeed driven by “angry men”.

We study these questions in the context of the Flemish region of Belgium, which presents a highly relevant setting for studying the role of emotions in populist radical right voting. Flanders is the largest region in the Belgian federal state and hosts one of the oldest and electorally most successful populist radical right parties in Europe—Vlaams Belang (before: Vlaams Blok). Due to a “cordon sanitaire”, which entails an agreement by all other democratic parties not to cooperate with Vlaams Belang on any political level, the party has never been part of a coalition government. Yet, Vlaams Belang currently ranks as the second largest Dutch-speaking party in Belgium, with 13.3% of the seats in the Belgian Federal Chamber of Representatives and 25% of the seats in the Flemish regional parliament after the 2024 elections. This underscores its relevance for the study of populist radical right party success. Moreover, Belgium has a system of compulsory voting and voter turnout tends to be consistently high (Caluwaerts et al., 2021). Even though previous studies on Dutch and Israeli elections have found that angry voters might decide not to participate electorally (van Zomeren et al., 2018), there are clear incentives for voters in Belgium to get out and vote. As such, Belgium is a most likely case for finding an effect of emotions on populist radical right voting. After all, there is no real “exit option” and angry voters, men and women, will have strong incentives to cast a vote. Additionally, Flanders is a multi-party system with, in addition to Vlaams Belang, several relevant mainstream left-and right-wing parties, and a populist radical left party PVDA. This allows us to test whether angry voters still opt for the populist radical right when presented with alternative choices. This aspect holds particular significance when viewed through a gendered lens, given previous research indicating a greater propensity among men to support socially and politically stigmatized parties such as Vlaams Belang (Harteveld et al., 2019).

We rely on data from the EOS RepResent voter panel survey organized in the context of the 2019 Belgian federal, regional, and European elections among a sample of eligible voters (18 years of age or older) (Walgrave et al., 2020). To measure voters’ emotions, respondents were asked to express their feelings towards Belgian politics based on discrete emotions, including anger. The EOS RepResent survey consisted of two waves: a pre-electoral wave which was organized before the elections and a post-electoral wave conducted right after the elections of 2019. In this paper, we use data from the second wave measuring voters’ actual voting behavior (N = 3,917 respondents in total, of which 1978 respondents in Flanders).

In line with previous studies, the results of our study show that populist radical right voters report strong levels of system-directed anger. Men and women voters are similar in their display of this emotion, and contrary to our expectations, they are similar in how system-directed anger relates to vote choice as well. More than explaining gender differences in populist radical right voting, our study confirms the idea that system-directed anger can incite women as well as men to cast a vote for the populist radical right.

In what follows, we first summarize the existing literature on the gender differences in support for populist radical right parties. Then, we develop our hypotheses regarding the role of emotions on the populist radical right vote, and how this may be gendered. Next, we discuss the case, methods, and data used in this study, followed by a presentation of the empirical results. To conclude, we summarize the main findings and discuss the implications for the study of gender, emotions, and populist radical right voting.

2 Theory

2.1 System-directed anger and populist radical right support

Because of the limitations of the explanations outlined above, and following the affective turn in political science (Thompson and Hogget, 2012), scholars have increasingly recognized the role of emotions in shaping voters’ preference for populist radical right parties (Redlawsk and Pierce, 2017; Vasilopoulos et al., 2019; Jacobs et al., 2024). Anger, in particular, has been found to affect electoral choices. Vasilopoulos et al. (2019) argue that anger, rather than fear or anxiety, drives support for far-right voting in France. Close and van Haute (2020) observe that anger, along with a lack of positive emotions like hope, increases support for populist radical right parties, and to some extent, populist radical left parties in Belgium. Similarly, Rico et al. (2017) argue that anger correlates positively with populist attitudes in Spanish elections, which, in turn, is linked to voting for populist parties.

Despite the prevailing focus on anger in the literature on emotions and voting behavior, it is important to differentiate between outgroup-directed anger and system-directed anger (van Zomeren et al., 2018; Petkanopoulou et al., 2022). Outgroup-directed anger targets specific individuals or groups perceived as belonging to a different identity group with distinct values, beliefs, and interests. System-directed anger is directed at the broader political system and institutions, without focusing on specific groups or politicians.

The distinction between outgroup-directed anger and system-directed anger holds particular relevance in understanding voting patterns. Even though the act of voting may be motivated by outgroup-directed anger, with the specific aim of promoting the interests of one’s identity group, previous studies have found that voting for populist radical right parties is strongly motivated by system-directed anger targeting politics in general (Jacobs et al., 2024).

There are several reasons why system-directed anger may shape voters’ preferences for populist radical right parties. A first argument is one of political information. People experiencing anger are less likely to thoroughly process political information and to more often seek out information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs leading to stronger opinion polarization (Wollebæk et al., 2019), and a more extreme vote. Secondly, anger might lead to votes for populist radical parties through these parties’ anti-establishment claims. Populist radical right parties often profile themselves as agents of change, i.e., as outsiders and challengers to the system which they consider to be irresponsive to the needs of the people. They assign blame to the abstract category of “elites” as being responsible for social or political problems (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2017), and this rhetoric resonates more strongly among individuals who feel angry with the political system. Anger can thus compel individuals to back parties that blame the establishment (Rico et al., 2017; Jacobs et al., 2024), a stance often leveraged by populist radical right parties. The final reason why anger could lead to populist radical right voting is that anger increases action preparedness (Valentino et al., 2011). System-directed anger is a moral emotion, driven by the perception of unfairness and illegitimacy produced by the political system, and as such motivates people to address these injustices (Rico et al., 2017). People experiencing feelings of anger or rage, especially those who are less politically sophisticated (Lamprianou and Ellinas, 2019), are thus more prepared to “take it to the streets”, and one way of doing so is by voting for a radical alternative to the status quo.

Even though the relationship between anger and the populist radical right vote is to be expected, we should point out that the effect of anger can also be context-specific, exhibiting variations across different political systems. For instance, the study by van Zomeren et al. (2018: 329) shows that system-directed anger dissuaded voter turnout in the Netherlands and Israel, and increased turnout in Italy. This suggests that the influence of anger is contingent upon the institutional and political characteristics of each country. Whereas most studies find that anger drives individuals towards the ideological extremes of the party spectrum, some studies indicate an alternative outcome—the possibility of anger prompting voters to opt for non-participation (Petkanopoulou et al., 2022). We consider this an unlikely option in Belgium. Because of its long-held system of compulsory voting, voters have few “exit” options. Although compulsory voting is hardly enforced in practice, abstention is not considered a viable option due to the existence of a strong social norm that encourages voting (Caluwaerts et al., 2021). Other “exit” options include null or blank voting, both of which are not common and have decreased over time (Pilet et al., 2019).

Based on the previous arguments, we hypothesize that:

H1: System-directed anger is associated with voting for populist radical right parties among men and women.

2.2 Gender, system-directed anger and populist radical right support

Even though we assume that system-directed anger is associated with support for populist radical right parties, there are reasons to believe that it might do so to a greater extent for men as opposed to women. Studies in political and social psychology show that men and women do not differ that much in how often and how intensely they experience anger. Contrary to prevailing stereotypes that sometimes juxtapose “angry men” versus “happy women”, men do not report more anger, and do not express anger more regularly, than women (e.g., Kring, 2000; Fischer and Evers, 2010).

However, differences do exist in relation to how women and men express anger (Evers et al., 2011). An important factor here is the role of social context. Individuals express emotions differently depending on the social implications that may follow. This social component is highly gendered, as the literature on social appraisal theory and social role theory indicates. Social appraisal theory assumes that emotional expressions and reactions are shaped by a person’s appraisal or evaluation of a particular situation and others’ reactions to it (Manstead and Fischer, 2001). If a person expects that expressing anger may result in negative social implications, they will either suppress or conceal these emotions, or express them in an indirect way (Evers et al., 2011). The finding that social appraisals shape emotional experiences and expressions speaks directly to social role theory. According to the latter, gender differences in behavior result from expectations about gender roles and gender stereotypes (Eagly, 1987; Eagly and Karau, 2002). Distinct societal expectations exist for women and men regarding “gender appropriate” behaviors and characteristics (Alexander and Wood, 2000; Eagly and Karau, 2002; Schrock and Knop, 2014). Women are expected to exhibit so-called “communal” traits and emotions, including empathy, affection, and compassion, while men are expected to display “agentic” traits and emotions, such as aggression, dominance, and confidence (Eagly and Karau, 2002; Schneider and Bos, 2019; Hargrave and Blumenau, 2022).

Societal expectations and reactions, prompted by gender stereotypes, thus shape how men and women express certain emotions (Eagly, 1987; Manstead and Fischer, 2001; Eagly and Karau, 2002). Concerning negative emotions, for instance, studies find that women express anger in more indirect ways, as expressing anger directly (e.g., through direct confrontation, verbal aggression, …) is considered a less socially acceptable emotion for women than men (Alexander and Wood, 2000; Evers et al., 2011; Salmela and Von Scheve, 2017). Research showing that women are less inclined towards aggressive and hostile styles of politics illustrates this further (Brescoll and Uhlmann, 2008; Salmela and Von Scheve, 2017). Additionally, because women are expected to exhibit “communal” traits and emotions, they are more prone to support policies that have a communal character, such as health care and redistributive policies. Men, on the contrary, are expected to display “agentic” traits and emotions, and therefore are more likely to endorse policies of an agentic nature, relating to military intervention and the punishment of crime (Huddy et al., 2008; Schneider and Bos, 2019; Hargrave and Blumenau, 2022).

Harteveld et al. (2019) argue that this gendered socialization has implications for voting behavior as well. They state that women are socialized to be more concerned about social harmony and social cues than men (Harteveld and Ivarsflaten, 2018; Harteveld et al., 2019). Consequently, women might consider possible (negative) social evaluations more strongly when making voting decisions. Despite the rise of populist radical parties in various countries, these parties often remain stigmatized and are considered unacceptable by a significant proportion of society (Mudde, 2007). Hence, despite potentially experiencing similar levels of system-directed anger as men, due to social gender norms and social stigma, women may be less inclined to vote for populist radical right parties. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2: System-directed anger is associated with voting for populist radical right parties, but more strongly so for men than women.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 The Belgian (Flemish) case and the 2019 federal elections

Our study of the relationship between system-directed anger, gender, and populist radical right voting focuses on Flanders, the largest region in Belgium. Belgium is a consensus democracy (Lijphart, 2012), combining key features such as a proportional representation electoral system, multi-party system, coalition governments, and a federal state structure. The party system in Belgium is regionalized and there are no state-wide parties. Dutch-speaking parties and French-speaking parties compete exclusively in their respective language areas of the country. Only in the bilingual region of Brussels, parties from both language groups compete directly against each other (Deschouwer, 2009). Belgium also applies a system of compulsory voting for all elections at the regional, federal, and European level.1 Although compulsory voting is hardly enforced in practice, voter turnout remains high (less than 12% of the voters abstained in 2019; Caluwaerts et al., 2021).

Similar to other countries, Belgian politics has witnessed the rise of several new populist radical right parties in the second half of the 20th century, albeit with varying degrees of electoral success in different parts of the country. The electorally most successful party by far is the populist radical right party Vlaams Belang (before: Vlaams Blok) in Flanders which is currently the second largest Dutch-speaking party, holding 12% of the seats in the Belgian Federal Chamber of Representatives and 18.5% of the seats in the regional Flemish parliament. The party was established in 2004 but its roots date back to its predecessor party Vlaams Blok which originated in 1978. Vlaams Blok won its first parliamentary seat in 1978 (van Haute and Pauwels, 2017). From this year on, the party was almost continuously represented in the federal and regional parliaments. It has never participated in any federal or regional government coalitions due to the “cordon sanitaire” which is an agreement by all other democratic parties not to cooperate with Vlaams Blok on any political level. Regarding its ideological and programmatic focus, Vlaams Belang qualifies as a “typical” populist radical right party (Mudde, 2007), combining populism, authoritarianism, and nativism as its core features. The party is not a “single issue party”. In addition to emphasizing cultural issues such as anti-immigration, Flemish nationalism, crime, and law and order in its program, the party also engages with traditional socio-economic issues. In the French-speaking part of the country, populist radical right parties have surfaced only occasionally, and no seats were obtained by a populist radical right party at the 2019 elections. For these reasons, we focus only on Flanders in this paper.

Similar to other countries in Europe, previous studies have witnessed a gender gap in voting for Vlaams Belang in federal and regional elections, although the gap seems to have decreased in recent years (Swyngedouw and Heerwegh, 2009; Abts et al., 2011, 2014). In addition to gender, electoral support for Vlaams Belang is lower among those employed in white collar jobs and highly educated voters, and higher among manual laborers and non-religious voters (Swyngedouw and Heerwegh, 2009; Abts et al., 2011, 2014). Protest attitudes and ideological considerations, especially in relation to the cultural issues dimension, also drive support for Vlaams Belang (Lubbers et al., 2000; Goovaerts et al., 2020).

In this paper, we study vote choice in the context of the Belgian federal elections of 26 May 2019. Federal and regional elections are held every 5 years. Since 2014, they have been simultaneously organized on the same day as European elections. Multiple parties are represented in the Flemish party system. Alongside the populist radical right Vlaams Belang, there are the radical left labor party Partij van de Arbeid van België (PVDA), the green party Groen, the social democratic party SP. A (in 2019, now Vooruit), the Christian democratic party CD&V, the liberal party Open VLD, and the regionalist party N-VA. Among these parties, N-VA obtained the largest amount of the votes in the 2019 federal elections (16%) (see Supplementary Table S1 for all election results) but both Vlaams Belang and PVDA could significantly boost their electoral scores compared to the 2014 elections. The 2019 elections were marked by electoral gains for opposition and radical parties, and a decline of the traditional parties (Pilet, 2021).

A multiparty system offers different options for voters to “voice” their anger. At the same time, Belgian voters’ exit options are rather limited. Due to the compulsory voting system, and despite it being hardly enforced in practice, abstention is not considered a viable option due to the existence of a strong social norm that encourages voting (Caluwaerts et al., 2021). As a result, abstention rates have remained below 10% until 2010 and have increased slightly to 12% after 2010.2 In a similar vein, blank and null voting are not common. In the last three parliamentary elections, around 5% of the voters cast a blank or null vote (see text footnote 2). While for some voters, blank and null voting can be considered an equivalent to abstention, it is not for all (Pilet et al., 2019).

3.2 Data and variables

In order to study the effect of system-directed anger on vote choice, we use data from the EOS RepResent voter survey organized in the context of the 2019 elections in Belgium (Walgrave et al., 2020). The EOS RepResent voter survey is an online panel survey that was conducted among a gross sample of eligible voters (18 years of age or older).3 The survey included two waves. The pre-electoral wave took place prior to the elections, spanning the period between 5 April and 5 May 2019. During this phase, data were gathered on voters’ sociodemographic background, political engagement, ideological perspectives, attitudes towards representation, voting intentions, among other relevant factors. Subsequently, the post-electoral wave was conducted immediately following the elections, between 28 May and 18 June 2019. This phase specifically concentrated on capturing information related to respondents’ actual voting behavior (Walgrave et al., 2020). The first wave involved 7,351 online interviews with eligible voters (3,298 respondents in Flanders, 3,025 respondents in Wallonia, and 1,028 respondents in Brussels). Respondents successfully reached during the first wave were invited to participate in the second wave, which included a sample of 3,917 respondents (1,978 in Flanders, 1,429 in Wallonia, and 510 in Brussels).

The sample was intended to be representative of the voting-age population in terms of gender, education, and age. In the final sample, higher educated voters, and age groups between 45 and 65, were slightly overrepresented (van Erkel et al., 2020). In order to take into account these differences, the EOS RepResent team calculated weights (post stratification). In this paper, we use weights for age, gender, and education. Moreover, we only use data for the Flemish region.4

Because our study focuses on vote choice, we only include respondents who participated in both waves. In order to measure respondents’ self-reported vote choice—the dependent variable in our study—we use the survey question in the post-electoral wave which asked “For which party did you vote for the Chamber during the federal elections on the 26th of May 2019?.” Respondents could indicate their preferred party from a closed-ended list of political parties represented in the Federal Parliament and a general category of “other parties”, or they could indicate that they voted “blank or invalid”, “did not vote”, “was not (yet) eligible to vote”, or “I do not remember”. Because our research question and hypotheses focused on “populist radical right voting”, we excluded voters who were not eligible to vote or did not remember. We recoded the original question into a dichotomous variable with 1 = populist radical right vote (Vlaams Belang) and 0 = non-populist radical right vote. The “0” category includes the populist radical left party PVDA, the mainstream right parties CD&V, N-VA and Open VLD, the mainstream left parties sp.a and Groen, and the “exit” option (blank, invalid, abstain). Because of the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable, we rely on binomial logistic regression models in the multivariate analyses.

We opted to work with actual vote choice in the post-electoral wave, rather than voting intentions in the pre-electoral wave, because it allows us to take into account “late-deciding” voters. Among the voters in the pre-electoral wave, 14.2% of the respondents in Flanders indicated that they “did not know” which party they would vote for “if elections were held today.” Previous studies show that these late-deciders may have a specific profile (e.g., women and young voters, as well as strategic voters, are more likely to delay the vote decision, Willocq, 2019), and we therefore decided to work with the results of the post-electoral wave. Actual vote choice questions may also face some limitations, including recall problems (with voters having difficulties to remember for which party they voted in which election). The fact that the post-electoral wave was organized shortly after the elections helped to limit recall problems.

The two main independent variables in our study are gender and system-directed anger.

In order to measure respondents’ gender, the survey asked respondents to indicate their gender in three categories: men, women, and other. Although the initial variable was not binary, we had to recode it into a dummy (men = 0, women = 1) because the “other” category was too small for any statistical analysis (N = 7, recoded as missing).

In order to measure voters’ system-directed anger, respondents were asked to express their feelings towards Belgian politics: “When you think of Belgian politics in general, to what extent do you feel each of the following emotions.” The questionnaire then listed eight discrete emotions, including “anger”. Respondents were asked to indicate how much they feel each of these emotions, on a scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“a great deal”). The same question was asked in both waves, but in this paper, we use only data from the pre-electoral wave to be able to assess how emotions impact vote choice (as we expect that the question in the post-electoral wave might measure respondents’ feelings towards the outcome of the election, see Close and van Haute, 2020). In this paper, we only focus on “anger” for theoretical reasons (see above). We do not include the other emotions in the analysis, because studies in political psychology show that different emotions may operate quite differently and are also expressed differently (see Close and van Haute, 2020; Jacobs et al., 2024).

In addition, the multivariate models add a number of control variables. We control for structural determinants which in previous research have been linked to populist radical right support, namely age and education (Ivarsflaten and Stubager, 2012; Goovaerts et al., 2020). Age is measured in years. Respondents’ educational attainment is coded in three categories: (1) none or primary education, (2) secondary education, and (3) tertiary education.

As for attitudinal control variables, we control for possible confounders which may be related to both populist radical right support and anger. Political dissatisfaction is associated with populist radical right voting (Oesch, 2008), and anger is one of the emotions most strongly associated with dissatisfaction (Tunç et al., 2023). We therefore include two control variables measuring “dissatisfaction with democracy” and “evaluation of the federal government”. “Dissatisfaction with democracy” controls for people’s support for the functioning of democracy more broadly. It is measured on a 1–5 scale, by asking respondents: “Overall, how satisfied are you with the way democracy is working in Belgium?” (1 = Very satisfied, 2 = Somewhat satisfied, 3 = not satisfied, nor unsatisfied, 4 = somewhat unsatisfied, 5 = very unsatisfied). “Evaluation of the federal government” controls for people’s satisfaction with the federal government and its policies. It was measured by the question: “To what extent are you satisfied with the policies implemented by the following political decision-making entities in the past few years? The federal government” (0–10 scale: 0 = Very unsatisfied, 10 = Very satisfied). Adding both forms of dissatisfaction is relevant because they may act as controls for different forms of group-based anger (see Petkanopoulou et al., 2022).

In addition, we include respondents’ left–right self-placement and anti-immigrant attitudes as control variables. Previous studies show that left–right ideology acts as a strong diver for vote choice (van der Brug et al., 2000; Jou and Dalton, 2017), and anti-immigrant attitudes are important determinants for populist radical right voting (Arzheimer, 2018; Goovaerts et al., 2020). Left–right self-placement is measured on a continuous 0–10 scale by asking respondents: “In politics, people often talk of ‘left’ or ‘right’. Can you place your own convictions on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 meaning ‘left’, 5 ‘in the centre’ and 10 ‘right’?.” Anti-immigrant attitudes are measured on a continuous 0–10 scale by considering respondents’ position on the following: “Some people think that non-western immigrants must be able to live in Europe while preserving their own culture. Others think that those immigrants should adapt to the European culture” (0–10 scale, with 0 meaning completely preserve their own culture and 10 meaning completely adapt to the European culture).

Supplementary Table S2 gives an overview of the descriptive statistics for each control variable. Supplementary Table S3 includes a correlation matrix for the attitudinal variables, which shows that multicollinearity is not a problem.

4 Results

4.1 Gender differences in system-directed anger

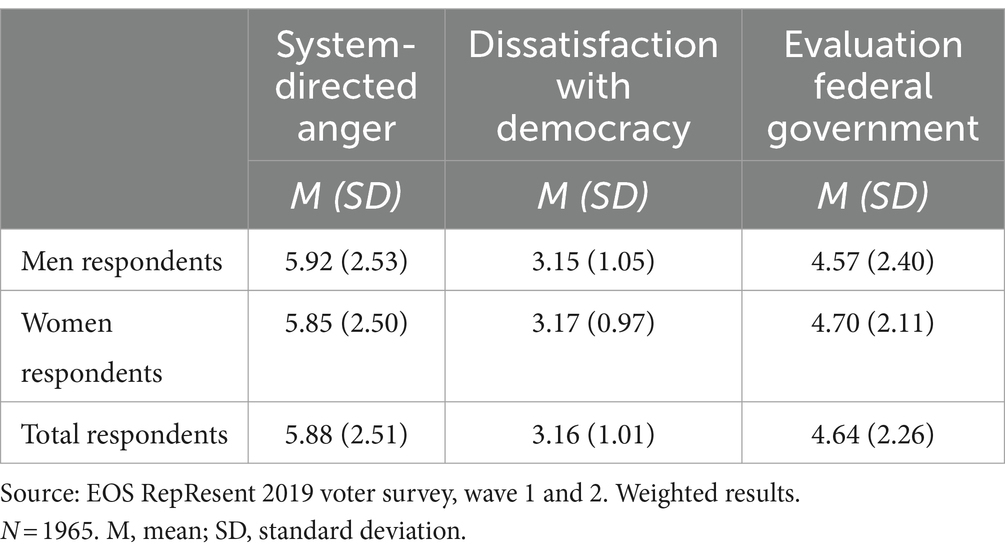

To explore the association between anger and vote choice, as well as any gender differences therein, we first need to examine whether differences exist in how men and women voters experience system-directed anger. Table 1 therefore presents the average scores of system-directed anger reported by men and women respondents, benchmarking them against other system-or government-directed attitudes, specifically voters’ dissatisfaction with democracy and their evaluation of the federal government. The results show that gender differences are small and not significant after t-test for the three variables. In line with previous studies (e.g., Evers et al., 2011), we find that men do not report higher levels of system-directed anger than women [t(1963) = 0.570, p = 0.569]. Men and women also present similar levels of dissatisfaction with democracy [t(1941.9) = −0.562, p = 0.574] and evaluation of the federal government [t(1921.8) = −1.251, p = 0.211].

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of system-directed anger, dissatisfaction with democracy and evaluation of the federal government, by respondents’ gender.

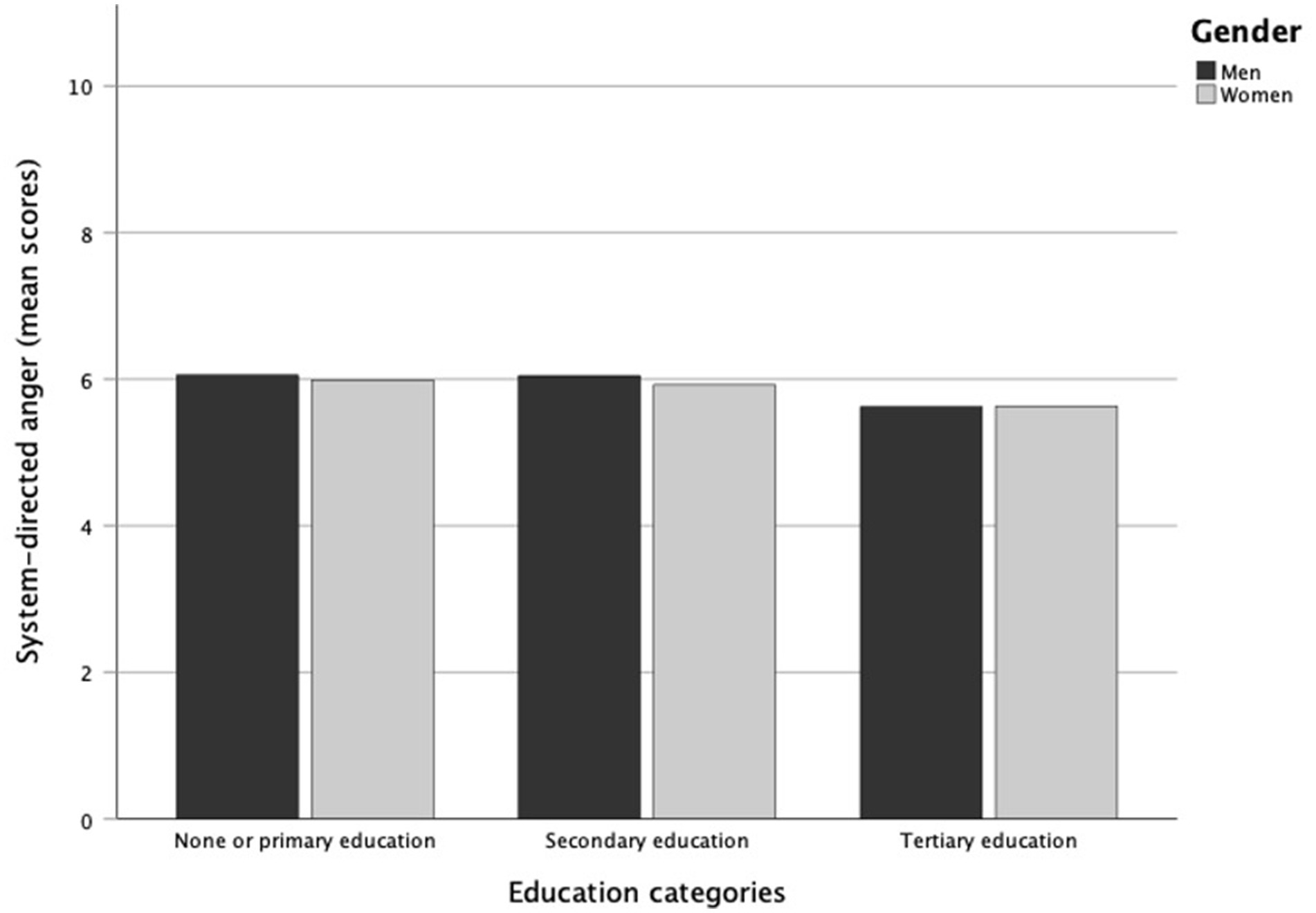

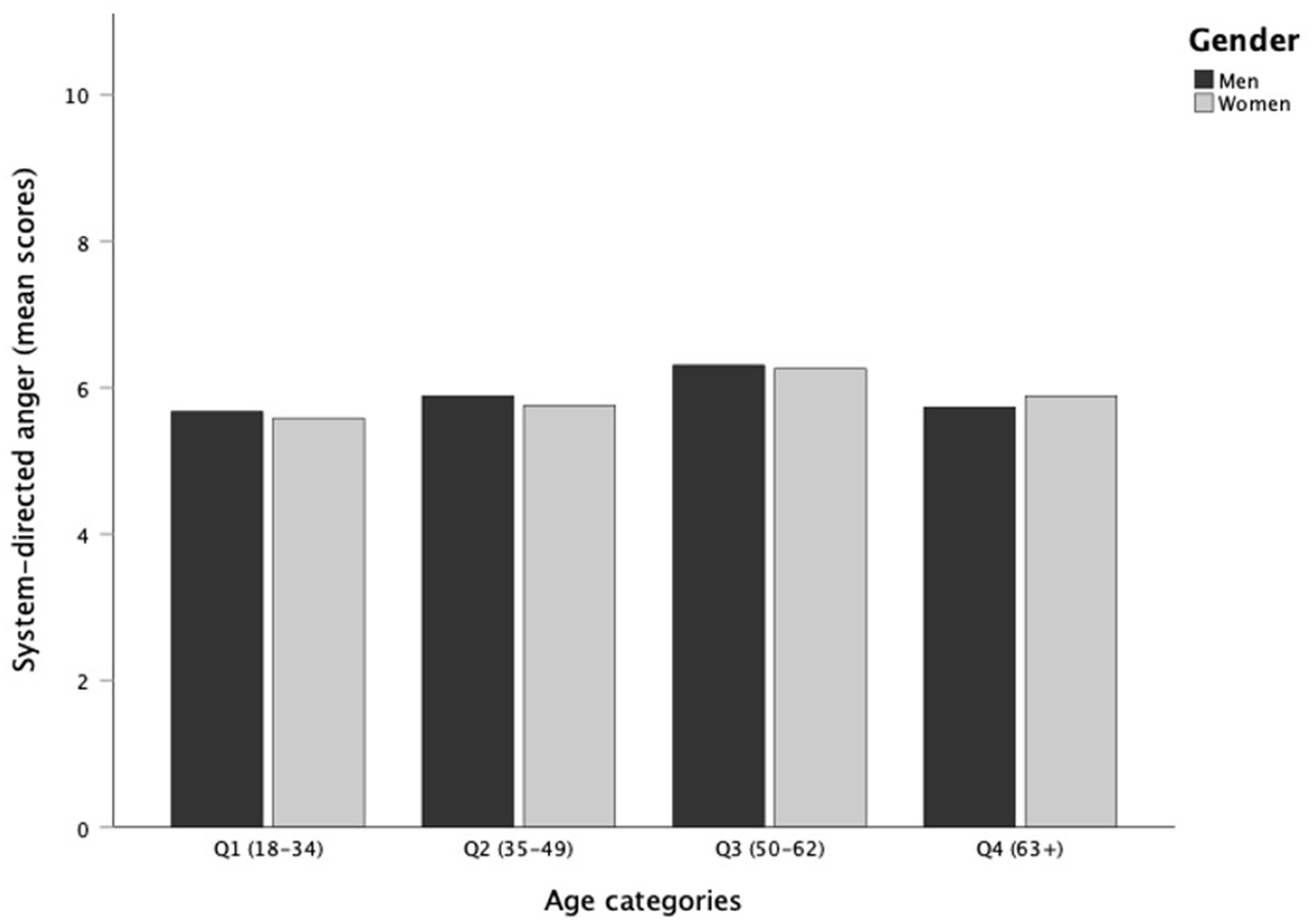

Moreover, gender differences in system-directed anger remain absent after controlling for respondents’ education and age in Figures 1, 2. In each educational group and in each age group, men and women express similar levels of system-directed anger (results after t-test are not significant). This challenges the notion that expressions of system-directed anger are exclusive to socio-demographic voter groups situated at the intersections of gender and education or gender and age. Instead, it suggests that system-directed anger permeates and manifests across diverse segments of the electorate in Flanders.

Figure 2. Mean scores system-directed anger, by gender and age quartiles (Flemish voters; N = 1,965).

Even if men and women do not differ in their anger towards Belgian politics, women and men may still cast their votes differently, and system-directed anger may still inform men’s and women’s vote choice in distinct ways. This will be examined in the next sections.

4.2 Gender, system-directed anger, and vote choice: bivariate analysis

Before turning to the multivariate analyses, we first present some bivariate analyses of the associations between gender and vote choice, and anger and vote choice.

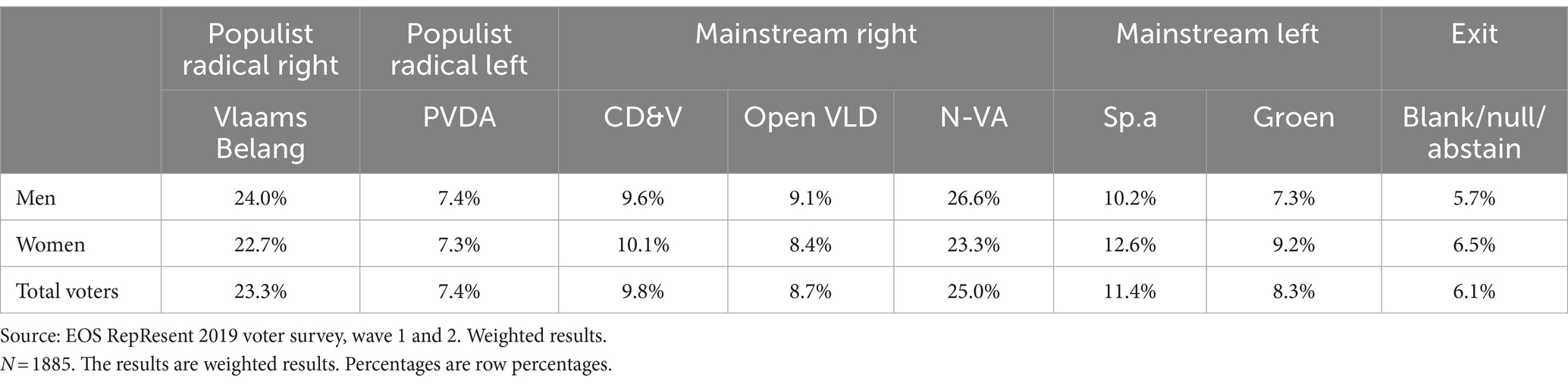

Table 2 compares the shares of men and women voters by vote choice. The results show that gender differences in vote choice are relatively small in Belgian elections. Right-wing parties, in general, draw relatively more votes from men, and fewer votes from women, compared to left-wing parties. Yet, similar to the results of the 2014 elections in Belgium (Abts et al., 2014), the gender gap in populist radical right voting has become small and not significant. Combined, the results confirm those of previous studies which suggest that gender gaps in multi-party systems may be minor and context-dependent (Campbell and Erzeel, 2018).

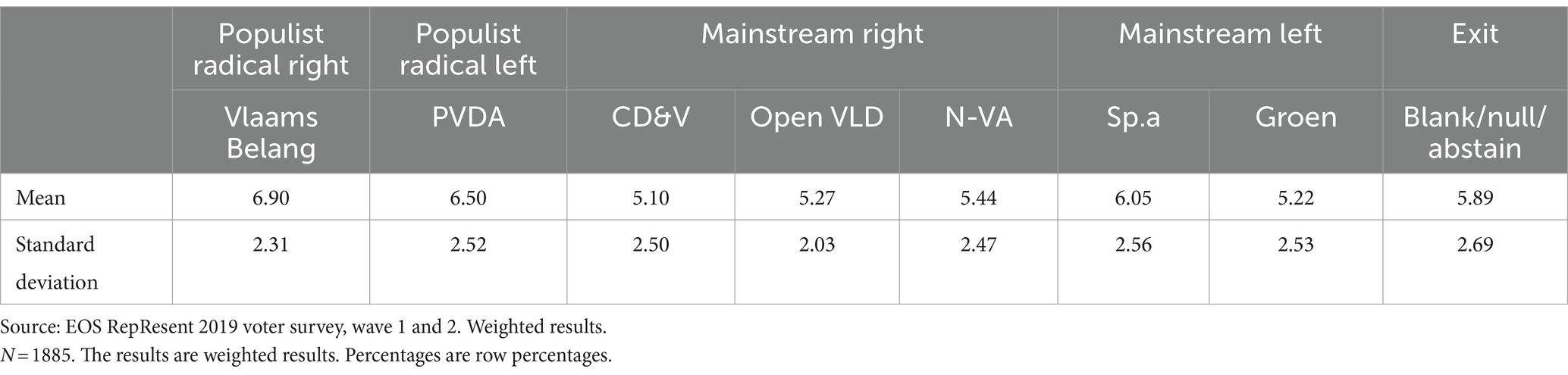

Table 3 then compares the mean scores for voters’ feelings of system-directed anger by vote choice. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed important differences among Flemish voters [F(7, 1877) = 20.495, p < 0.001]. Post Hoc tests were conducted using the Tukey honest significant difference (HSD). The comparisons revealed significant differences between the scores for populist radical right voters on the one hand and mainstream right, mainstream left and exit voters on the other hand. Vlaams Belang-voters clearly distinguish themselves from other right-wing party voters such as N-VA and Open VLD, with a mean difference of 1.5 and 1.6, respectively, on the 0–10 scale. The Post Hoc comparisons did not reveal any significant differences between populist radical right and populist radical left voters. Hence, the “anger gap” seems to be one that separates radical voters from mainstream voters, regardless of their ideological stance on the left–right spectrum.

4.3 Gender, system-directed anger, and vote choice: multivariate analysis

The bivariate analyses above do not control for other variables that might affect vote choice. To test this relationship further, we now turn to a multivariate analysis in Table 4.

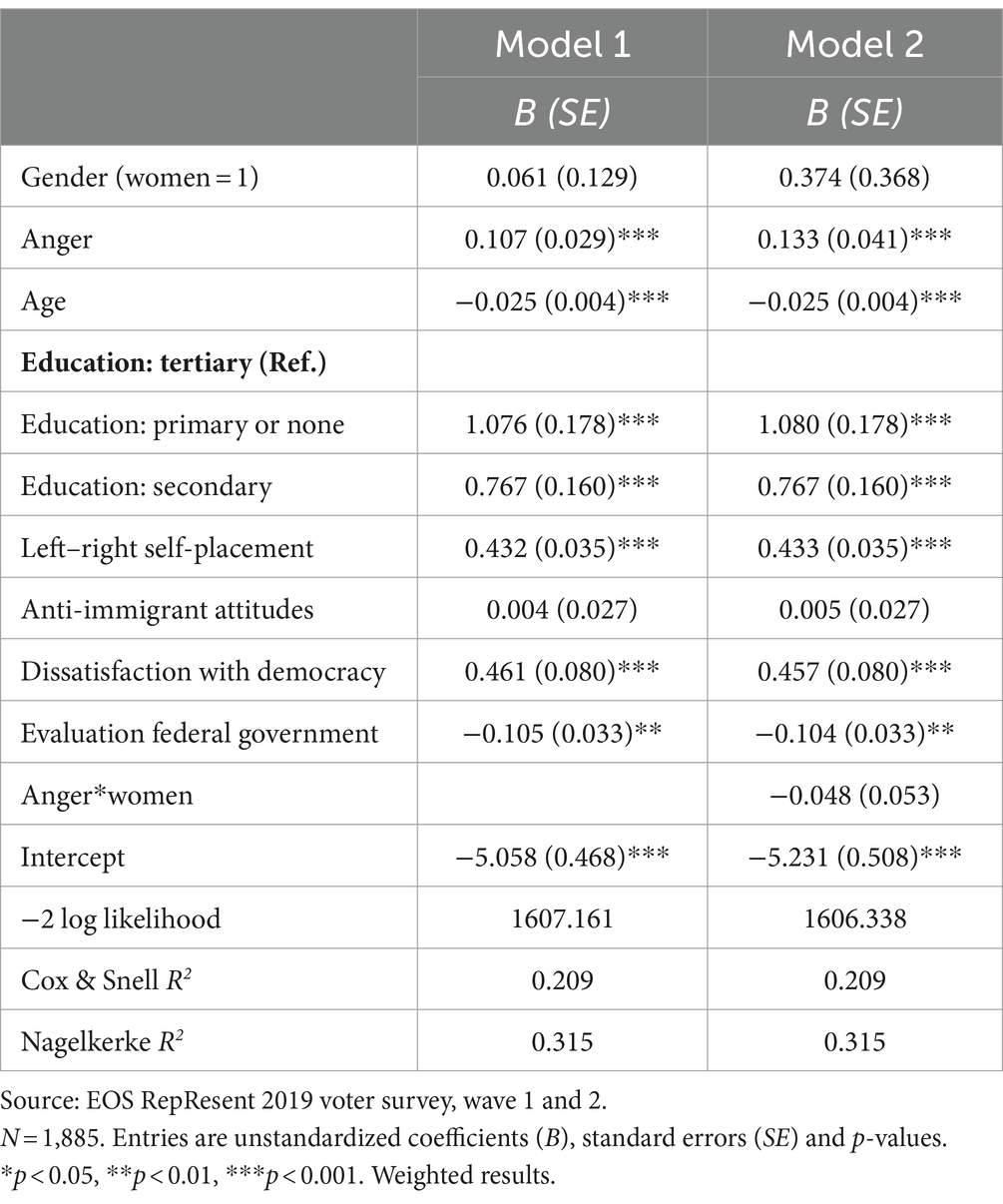

Table 4 shows the results of a binomial logistic regression analysis predicting populist radical right voting. Model 1 presents the main effects of the independent variables (gender and system-directed anger) with control variables. Model 2 displays the results for the interaction effect between gender*anger. Presenting Models 1 and 2 as stepwise models allows us to assess changes in the pseudo-R2 when introducing the interaction effect. The explanatory power of both models in Table 4 is quite high. A model including only gender and anger as independent variables without control variables (not shown here) has a Cox & Snell R2 of 0.051 and a Nagelkerke R2 of 0.077 for populist radical right voting. Adding our list of control variables in Model 1 increases the pseudo-R2 substantially. Adding the interaction term in Model 2, however, does little for the model.

Turning now to the parameter estimates, we first consider the main effects in Model 1. In line with the bivariate results, gender differences are not statistically significant. Women are not less likely to vote for Vlaams Belang than men. Contrary to assumptions regarding the radical right gender gap, gender is not associated with populist radical right voting.

When examining the parameter estimates for “system-directed anger”, we find that higher levels of system-directed anger are generally linked to a higher likelihood of voting Vlaams Belang, also after controlling for gender. Anger is positively associated with a higher likelihood of voting for the populist radical right for both men and women, which confirms H1.

When we consider the effects of the control variables, we can mostly confirm the findings of previous studies on populist radical right voting (e.g., Lubbers et al., 2000; Goovaerts et al., 2020). Left–right attitudes are strongly related to vote choice, confirming patterns of ideological voting. Dissatisfaction with democracy and being dissatisfied with the federal government steers voters towards a populist radical right vote. Education also shapes vote choice: lower educated voters are more likely to vote for the populist radical right. Perhaps surprisingly, voters’ position on the assimilation of migrants is not related to populist radical right voting.

Given that we are interested in the question whether anger interacts with gender in explaining vote choice, we include an interaction term in Model 2 in Table 4. Including this interaction term, however, does not alter the model, and the interaction effect is not statistically significant. As a result, we need to reject H2: system-directed anger is not more strongly associated with populist radical right voting for men than women.

4.4 Robustness

To validate whether the results are robust, we ran several variations on the models presented above, adjusting both the anger variable and the vote choice variable. Supplementary material offers an overview of these findings.

Changing the anger variable to a dummy (angry vs. not angry, median split) does not change the results (Supplementary Table S4).

Next, we estimated federal vote choice in a multinomial logistic regression using the dependent variable “having voted for the populist radical right” (versus having voted for the populist radical left, mainstream right, mainstream left and opting to exit) (Supplementary Table S5). These models show a significant association between system-directed anger and vote choice for most party categories, except for the populist radical left, which indicates that anger is indeed related to anti-system voting (see also Jacobs et al., 2024). Anger makes voters turn less to the “exit option” (compared to the populist radical right). This is as expected: due to the system of compulsory voting and the presence of two radical anti-system parties in the Flemish party system, the “exit” option is less attractive for angry voters. Angry voters are less likely to vote for a mainstream right and mainstream left party (compared to the populist radical right), and the effect is strongest for mainstream right parties.

Given that mainstream right parties were in government (N-VA, Open VLD, CD&V) before the elections, we ran additional analyses at the party level to test whether anger was negatively associated with voting for all government parties to take into account potential government-directed anger. The results show that anger is indeed negatively linked with voting for N-VA, but not for Open VLD and CD&V (Supplementary Table S6). While this indicates that system-directed anger may pick up on expressions of government-directed anger among voters, they are also empirically distinct.

5 Discussion

This paper focused on the question whether and how negative emotions, and system-directed anger in particular, inform populist radical right voting in Flanders, and whether and how this is different for men and women voters. Drawing on the established literature on the populist radical right gender gap as well as on the new and emerging scholarship on affective models of populist radical right voting, we examined whether men and women express emotions differently in the electoral arena. Previous studies in the field have shown that anger increases voter support for the populist radical right (Erisen and Vasilopoulou, 2022). We combined these insights with insights from social role theory and social appraisal theory which suggest that women may expect more negative social implications from expressing anger in the public sphere, and will therefore refrain from translating these emotions into a populist radical right vote.

However, contrary to our expectations, we can only confirm one of our two hypotheses in the Flemish case. Although voters experiencing system-directed anger do support the populist radical right party Vlaams Belang more than they support mainstream right and left parties, this was equally the case for men and women. Moreover, gender had no significant effect on populist radical right voting, neither as a main effect nor in interaction with anger. If anything, men and women are surprisingly similar in their display of system-directed anger, as well as in how anger relates to vote choice. More than explaining gender differences in populist radical right voting, our findings confirm the idea that system-directed anger can incite women as well as men to cast a populist radical right vote.

Why do gender differences remain absent? We see three reasons. One reason is that voting may not involve a high-conflict, high-risk type of public behavior in which gender differences in anger would typically manifest themselves. Angry individuals, especially men, might engage in protest activities rather than voting to express their anger in a more direct and overt way (Celis et al., 2021). To the extent that women see few negative social implications from expressing anger through the (populist radical right) vote, it may be an attractive option to express anger in an indirect manner. More research is needed to test this point. A second reason is that social norms regarding “appropriate behavior” may have changed. Although Vlaams Belang is, due to the “cordon sanitaire”, still a politically stigmatized party which may discourage some voters from casting a populist radical right vote, it is possible that the social stigma has changed in recent elections. The party has existed for several decades and is currently the second largest party in Flanders, which may have affected the social cues regarding the “appropriateness” of voting for Vlaams Belang. The fact that the gender gap in populist radical right voting has also narrowed in recent elections seems to support this point. A third and final reason links to the specific context in Flanders which does not offer any viable exit options. It would be interesting to examine whether system-directed anger steers women more than men towards exit options in countries without compulsory voting or in countries where the social norm of voting as a civic duty is less strong.

Despite the lack of gender differences, an important finding is that system-directed anger does inform populist radical right voting in Flanders, as is the case in other Western European countries. As such, our case study adds to new theories which suggest that there is an affective model of populist radical right voting in Europe (e.g., for France: Vasilopoulos et al., 2017, 2019; for Germany, Netherlands and the UK: Erisen and Vasilopoulou, 2022). Given that in our findings system-directed anger was also related to higher levels of support for the (smaller) populist radical left party, the link between anger and anti-establishment voting more broadly deserves more attention in future research (see also Jacobs et al., 2024), including the gendered aspects thereof. In relation to this issue, our study could not fully disentangle the effects of system-directed anger, government-directed and politicians-directed anger on (anti-system) voting (Petkanopoulou et al., 2022) due to data limitations. Given that different forms of group-based anger affect voting differently (van Zomeren et al., 2018; Petkanopoulou et al., 2022), future research might find it interesting to compare different measurements of group-based anger and study their gendered effects.

A final important implication is that our study needs to reject the popular idea that “angry men” are the driving forces behind populist radical right voting in Flanders. In the Flemish case, men and women voters displayed similar levels of system-directed anger, and anger motivated both women and men to cast a populist radical right vote. This seems to suggest that populist radical right voting is driven by angry men and angry women. However, an important caveat is that we were unable to test the (three-way) interaction with the socio-economic background of voters. Due to the lack of appropriate measures in the survey, we were also unable to test for the role of race or ethnic minority/minoritized status. These are important questions for future research.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found at: https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xe8-7t78.

Author contributions

SE: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MF: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BB: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The data used in this publication were collected by the EOS RepResent Consortium. The RepResent Voter Panel Survey was funded by Excellence of Science (FWO/FNRS) (FNRS-FWO n°G0F0218N). Neither the contributors to the data collection nor the sponsors of the project bear any responsibility for the analyses conducted or the interpretation of the results published here. The study was furthermore supported by the Research Foundation-Flanders (FWO) under grants 1113324 N, G040823N, G0G7620N, and 11P2224N, and Vrije Universiteit Brussel under Grant SRP79-Enhancing Democratic Governance in Europe.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the EOS RepResent Consortium and all persons who have contributed to the data collection. They also wish to thank Koen Damhuis, Anouk Smeekes, and Ekaterina R. Rashkova as guest editors of this research topic, and Franziska Wagner, Vít Hloušek, and all the participants in the Expert Workshop on the Role of Affect in the Electoral Appeal of Radical Right Parties Across Europe, organized at Utrecht University in September 2023, for their valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1401601/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Compulsory voting was recently abolished for local elections in Flanders and will operate as such from the elections of 2024 onwards.

2. ^Federale Overheidsdienst Binnenlandse Zaken, Directie Verkiezingen, https://verkiezingen.fgov.be/ (Accessed February 22, 2024).

3. ^The survey was conducted by Kantar TNS, a data and market research company, and was commissioned by EOS RepResent. EOS RepResent is a research consortium funded by the FWO/FNRS Excellence of Science program, involving the Universiteit Antwerpen, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Université libre de Bruxelles, KULeuven and Université catholique de Louvain. The EOS RepResent interuniversity team was responsible for the development, organization, and supervision of the survey.

4. ^We exclude Wallonia because there is no populist radical right party. Brussels is the smallest of the three regions in Belgium and is characterized by a complex and fragmented party system. The relatively low N of Brussels voters in the sample, especially Vlaams Belang voters, make it impossible to draw conclusions for this case.

References

Abts, K., Swyngedouw, M., and Billiet, J. (2011). De structurele en culturele kenmerken van het stemgedrag in Vlaanderen. Analyse op basis van het postelectorale verkiezingsonderzoek 2010. Leuven: CeSO/ISPO.

Abts, K., Swyngedouw, M., and Meuleman, B. (2014). Het profiel van de Vlaamse kiezers in 2014. Wie stemde op welke partij? Analyse op basis van de postelectorale verkiezingsonderzoeken 1991–2014. Leuven: CeSO/ISPO.

Alexander, M., and Wood, W. (2000). “Women, men, and positive emotions: A social role interpretation” in Gender and emotion: social psychological perspectives. ed. A. H. Fischer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 189–210.

Arzheimer, K. (2018). “Explaining electoral support for the radical right” in The Oxford handbook of the radical right. ed. J. Rydgren (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 143–165.

Brescoll, V. L., and Uhlmann, E. L. (2008). Can an angry woman get ahead? Status conferral, gender, and expression of emotion in the workplace. Psychol. Sci. 19, 268–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02079.x

Bustikova, L. (2019). Extreme reactions. Radical right mobilization in Eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Caluwaerts, D., Devillers, S., Junius, N., Matthieu, J., and Pauwels, S. (2021). “Compulsory voting. Anachronism or avant-Garde?” in Belgian exceptionalism. Belgian politics between realism and surrealism. eds. D. Caluwaerts and M. Reuchamps (London: Routledge), 13–26.

Campbell, R., and Erzeel, S. (2018). Exploring gender differences in support for rightist parties: the role of party and gender ideology. Polit. Gend. 14, 80–105. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X17000599

Celis, K., Knops, L., Van Ingelgom, V., and Verhaegen, S. (2021). Resentment and coping with the democratic dilemma. Polit. Governance 9, 237–247. doi: 10.17645/pag.v9i3.4026

Close, C., and van Haute, E. (2020). Emotions and vote choice: an analysis of the 2019 Belgian elections. Polit. Low Countries 2, 353–379. doi: 10.5553/PLC/258999292020002003006

Deschouwer, K. (2009). The politics of Belgium: Governing a divided society. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Reporting sex differences. Am. Psychol. 42, 756–757. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.42.7.755

Eagly, A. H., and Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 109, 573–598. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Erisen, C., and Vasilopoulou, S. (2022). The affective model of far-right vote in Europe: anger, political trust and immigration. Soc. Sci. Q. 103, 635–648. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13153

Evers, C., Fischer, A. H., and Manstead, A. (2011). “Gender and emotion regulation: a social appraisal perspective on anger” in Emotion regulation and well-being. eds. I. Nyklicek, A. D. Vingerhoets, and M. Zeelenberg (New York: Springer), 211–222.

Fischer, A. H., and Evers, C. (2010). “Anger in the context of gender” in The international handbook of anger: Constituent and concomitant biological, psychological, and social processes. eds. M. Potegal, G. Stemmler, and C. Spielberger (New York: Springer), 349–360.

Ford, R., and Goodwin, M. J. (2010). Angry white men: individual and contextual predictors of support for the British National Party. Polit. Stud. 58, 1–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00829.x

Gerber, L. R., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., and Dowling, C. M. (2012). Is there a secret ballot? Ballot secrecy perceptions and their implications for voting behaviour. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 43, 77–102. doi: 10.1017/S000712341200021X

Gerber, L. R., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., and Hill, S. J. (2013). Who wants to discuss vote choices with others? Polarization in preferences for deliberation. Public Opin. Q. 77, 474–496. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs057

Gidengil, E., Hennigar, M., Blais, A., and Nevitte, N. (2005). Explaining the gender gap in support for the new right. The case of Canada. Comp. Pol. Stud. 38, 1171–1195. doi: 10.1177/0010414005279320

Givens, T. E. (2004). The radical right gender gap. Comp. Pol. Stud. 37, 30–54. doi: 10.1177/0010414003260124

Goovaerts, I., Kern, A., van Haute, E., and Marien, S. (2020). Drivers of support for the populist radical left and populist radical right in Belgium. Polit. Low Countries 2, 228–264. doi: 10.5553/plc/258999292020002003002

Hargrave, L., and Blumenau, J. (2022). No longer conforming to stereotypes? Gender, political style and parliamentary debate in the UK. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 52, 1584–1601. doi: 10.1017/S0007123421000648

Harteveld, E., Dahlberg, S., Kokkonen, A., and van der Brug, W. (2019). Gender differences in vote choice: social cues and social harmony as heuristics. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 1141–1161. doi: 10.1017/S0007123417000138

Harteveld, E., and Ivarsflaten, E. (2018). Why women avoid the radical right: internalized norms and party reputations. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 48, 369–384. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000745

Huddy, L., Cassese, E., and Lizotte, M.-K. (2008). “Gender, public opinion, and political reasoning” in Political women and American democracy. eds. C. Wolbrecht, K. Beckwith, and L. Baldez (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 31–49.

Immerzeel, T., Coffé, H., and van der Lippe, T. (2015). Explaining the gender gap in radical right voting: a cross-National Investigation in 12 Western European countries. Comp. Eur. Polit. 13, 263–286. doi: 10.1057/cep.2013.20

Ivarsflaten, E., and Stubager, R. (2012). “Voting for the populist radical right in Western Europe. The role of education” in Class politics and the radical right. ed. J. Rydgren (London: Routledge), 122–138.

Jacobs, L., Close, C., and Pilet, J.-B. (2024). The angry voter? The role of emotions in voting for the radical left and right at the 2019 Belgian elections. Int. Political Sci. Rev. First published online February 5, 2024. doi: 10.1177/01925121231224524

Jou, W., and Dalton, R. J. (2017) Left-right orientations and voting behavior. Oxford research encyclopedias, politics. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.581

Kring, A. (2000). “Gender and anger” in Gender and emotion: social psychological perspectives. ed. A. H. Fischer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 211–231.

Lamprianou, I., and Ellinas, A. A. (2019). Emotion, sophistication and political behavior: evidence from a laboratory experiment. Polit. Psychol. 40, 859–876. doi: 10.1111/pops.12536

Lijphart, A. (2012). Patterns of democracy. Government forms and performance in thirty-six countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lubbers, M., Scheepers, P., and Billiet, J. (2000). Multilevel modelling of Vlaams Blok voting: individual and contextual characteristics of the Vlaams Blok vote. Acta Politica 35, 363–398.

Manstead, A., and Fischer, A. H. (2001). “Social appraisal: the social world as object of and influence on appraisal processes” in Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. eds. K. Scherer, A. Schorr, and T. Johnstone (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 221–232.

Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., and Mac Kuen, M. (2000). Affective intelligence and political judgment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mayer, N. (2015). The closing of the radical right gender gap in France? Fr. Politics 13, 391–414. doi: 10.1057/fp.2015.18

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash. Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oesch, D. (2008). Explaining workers’ support for right-wing populist parties in Western Europe: evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 29, 349–373. doi: 10.1177/0192512107088390

Off, G. (2023). Gender equality salience, backlash and radical right voting in the gender-equal context of Sweden. West Eur. Polit. 46, 451–476. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2022.2084986

Pease, B. (2021). “The rise of angry white men: resisting populist masculinity and the backlash against gender equality” in The challenge of right-wing nationalist populism for social work. eds. C. Noble and G. Ottmann (London: Routledge), 55–68.

Petkanopoulou, K., Chryssochoou, X., Zacharia, M., and Pavlopoulos, V. (2022). Collective disadvantage in the context of socioeconomic crisis in Greece: the role of system-directed anger, politicians-directed anger and Hope in normative and non-normative collective action participation. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 589–607. doi: 10.1002/casp.2580

Pilet, J.-B. (2021). Hard times for governing parties: the 2019 Federal Elections in Belgium. West Eur. Polit. 44, 439–449. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2020.1750834

Pilet, J.-B., Jimena Sanhuza, M., Talukder, D., Dodeigne, J., and Brennan, A. E. (2019). Opening the opaque blank box. An exploration into blank and null votes in the 2018 Walloon local elections. Polit. Low Countries 1, 182–204. doi: 10.5553/PLC/258999292019001003003

Redlawsk, D. P., and Pierce, D. R. (2017). “Emotions and voting” in The sage handbook of electoral behaviour. eds. K. Arzheimber, J. Evans, and M. S. Lewis-Beck (London: Sage), 406–432.

Rico, G., Guinjoan, M., and Anduiza, E. (2017). The emotional underpinnings of populism: how anger and fear affect populist attitudes. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 444–461. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12261

Salmela, M., and Von Scheve, C. (2017). Emotional roots of right-wing political populism. Soc. Sci. Inf. 56, 567–595. doi: 10.1177/0539018417734419

Santoro, L. R., and Beck, P. A. (2017). “Social networks and vote choice” in The Oxford handbook of political networks. eds. J. N. Victor, A. H. Montgomery, and M. Lubell (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 383–406.

Schneider, M. C., and Bos, A. L. (2019). The application of social role theory to the study of gender in politics. Polit. Psychol. 40, 173–213. doi: 10.1111/pops.12573

Schrock, D., and Knop, B. (2014). “Gender and emotions” in The handbook of the sociology of emotions. eds. J. E. Stets and J. H. Turner, vol. II (Netherlands: Springer), 411–428.

Setzler, M., and Yanus, A. B. (2018). Why did women vote for Donald Trump? PS. Polit. Sci. Polit. 51, 523–527. doi: 10.1017/S1049096518000355

Spierings, N., and Zaslove, A. (2017). Gender, populist attitudes, and voting: explaining the gender gap in voting for populist radical right and populist radical left parties. West Eur. Polit. 40, 821–847. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2017.1287448

Swyngedouw, M., and Heerwegh, D. (2009). Wie stemt op welke partij? De structurele en culturele kenmerken van het stemgedrag in Vlaanderen. Een analyse op basis van het postelectorale verkiezingsonderzoek 2007. Leuven: CeSO/ISPO.

Thompson, S., and Hogget, P. (2012). Politics and the emotions. The affective turn in contemporary political studies. New York: Continuum.

Tunç, M. N., Brandt, M. J., and Zeelenberg, M. (2023). Not every dissatisfaction is the same: the impact of electoral regret, disappointment, and anger on subsequent electoral behavior. Emotion 23, 554–568. doi: 10.1037/emo0001064

Valentino, N. A., Brader, T., Groenendyk, E. W., Gregorowicz, K., and Hutchings, V. L. (2011). Election night’s alright for fighting: The role of emotions in political participation. J. Politics. 73, 156–170. doi: 10.1017/S0022381610000939

van der Brug, W., Fennema, M., and Tillie, J. (2000). Anti-immigrant parties in Europe: ideological or protest vote? Eur J Polit Res 37, 77–102. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00505

van Erkel, P., Kern, A., and Petit, G. (2020). Explaining vote choice in the 2019 Belgian elections. Democratic, populist and emotional drivers. Polit. Low Countries 2, 223–227. doi: 10.5553/PLC/258999292020002003001

van Haute, E., and Pauwels, T. (2017). “The Vlaams Belang: party organization and party dynamics” in Understanding populist party organization. The radical right in Western Europe. eds. R. Heinisch and O. Mazzoleni (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 49–77.

van Zomeren, M., Saguy, T., Mazzoni, D., and Cicognani, E. (2018). The curious, context-dependent case of anger: explaining voting intentions in three different National Elections. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 48, 329–338. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12514

Vasilopoulos, P., Marcus, G. E., and Foucault, M. (2017). Emotional responses to the Charlie Hebdo attacks: addressing the authoritarianism puzzle. Polit. Psychol. 39, 557–575. doi: 10.1111/pops.12439

Vasilopoulos, P., Marcus, G. E., Valentino, N. A., and Foucault, M. (2019). Fear, anger, and voting for the far right: evidence from the November 13, 2015 Paris terror attacks. Polit. Psychol. 40, 679–704. doi: 10.1111/pops.12513

Walgrave, S., van Erkel, P., Jennart, I., Celis, K., Deschouwer, K., Marien, S., et al. (2020). RepResent longitudinal and cross-sectional electoral survey 2019. DANS. doi: 10.17026/dans-xe8-7t78

Willocq, S. (2019). Explaining time of vote decision: the socio-structural, attitudinal and contextual determinants of late deciding. Polit. Stud. Rev. 17, 53–64. doi: 10.1177/1478929917748484

Keywords: gender gap, populist radical right voting, system-directed anger, electoral behavior, Belgium

Citation: Erzeel S, Fieremans M, Van Bavel A, Blanckaert B and Caluwaerts D (2024) Angry men and angry women: gender, system-directed anger and populist radical right voting in Belgium. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1401601. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1401601

Edited by:

Anouk Smeekes, Utrecht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Susan Banducci, University of Exeter, United KingdomHilde Coffe, University of Bath, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Erzeel, Fieremans, Van Bavel, Blanckaert and Caluwaerts. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Silvia Erzeel, c2lsdmlhLmVyemVlbEB2dWIuYmU=

Silvia Erzeel

Silvia Erzeel Merel Fieremans

Merel Fieremans Anne Van Bavel

Anne Van Bavel Benjamin Blanckaert

Benjamin Blanckaert Didier Caluwaerts

Didier Caluwaerts