- 1Department of Political Science, University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

- 2LIER-FYT, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris, France

This article adopts a Durkheimian perspective and employs a socio-pragmatic method of inquiry, with a specific focus on analyzing “scandals” as critical junctures and the interpretations provided by social actors. The aim is to explore the development of corruption as a social issue in Romania over the past four decades. In contrast to two prevailing explanatory approaches in Romania, labeled here as fatalistic and voluntarist, we propose a more reflective approach. This perspective illustrates how the increasing division of labor and the subsequent rise in individualization within social relations have progressively influenced the tendencies and sensitivities of various social groups in Romanian society, particularly regarding what this study refers to as “illegal personal enrichment” (IPE). By focusing on discourse analysis of debates on corruption, this study analyses the evolution of the politicization of corruption—a subject still largely unexplored but highly prevalent in the public sphere—in conjunction with the structural changes in Romanian society. Consequently, three stages can be identified: IPE as a discursive tool for denouncing political adversaries, IEP as a generator of political conflicts, and IEP as a public issue.

1 Introduction

There are many discourses by scientists, politicians, and journalists that portray corruption as a Romanian cultural characteristic. It is believed to correspond to local norms in this country, which means that this phenomenon would be deeply rooted in social expectations, and that the actors would perceive it as self-evident. If this were the case, however, one wonders how to explain the increasing politicization of “corruption” over the last thirty years. This is the paradox that lies behind the present research.

A common explanation for this paradox lies in the hypothesis that the growing condemnation of corruption in contemporary Romania is the result of external pressure, primarily emanating from institutions and agents of the European Union, and therefore remains superficial. This article starts from a different perspective: the increase in intolerance toward corruption, far from resulting solely or primarily from exogenous pressures, originates from endogenous transformations within Romanian society – through which these exogenous pressures come to be more favorably received than they were before. Inspired by a Durkheimian perspective, and combining it with a socio-pragmatic investigative methodology (especially focused on the analysis of “scandals” and the interpretations given by the actors), this study demonstrates how the increase in the division of labor and consequently, the progression of individualization norms within social relationships, have gradually modified the predispositions and sensitivities of different social groups constituting Romanian society in regards to corruption. Thus, that the increase in anti-corruption receptivity in Romania over the past thirty years results from structural social transformations. However, it is not a matter of stating that the discourse of the European Union and adherence to international institutions have no effect on the fight against corruption. If they have an effect – which is easy to demonstrate – we will argue that it is mainly because there are internal transformations happening in Romania. This is manifested by the existence of social groups that share the values of the European Union.

Given the identified paradox outlined above, this investigation holds a dual purpose in addressing the research question. Conceptually, the aim is to demonstrate an interest in surpassing prevailing paradigms in the examination of corruption in Romania, succinctly termed as fatalistic and voluntaristic in this study. Aligned with the ongoing constructivist perspective, this study advocates for a socio-pragmatic approach intertwined with the Durkheimian tradition. This novel perspective on corruption prompts the adoption of an approach centered on endogenous transformations within Romania, allowing for an exploration of the increasing politicization of “corruption” by analyzing its meaning construction. By linking discourse analysis on the subject—acquired through public media, both national and international, as well as communist archives—to the social transformations occurring over the last four decades and the subsequent individualization of social norms, this study aims to illustrate that the heightened visibility of this public issue on the political and media agenda primarily stems from internal transformations occurring in Romania, manifested by the presence of social groups sharing similar concerns. Consequently, this paper presents an analytical model that paves the way for future research focusing on a nuanced understanding of the emergence of anti-corruption movements in Romania.

This paper is organized as follows: in the first section, we address the theoretical background while providing a comprehensive presentation of an innovative methodological approach to understanding the politicization of corruption and its underlying conceptual origins, while comparing it to other dominant approaches of the matter. The second section addresses the methodological perspectives and conceptual framework, advocating for the use of a more impartial term, such as “illegal enrichment practices,” to describe corrupt activities in order to reach a better understanding of the phenomenon. The subsequent section is dedicated to delving into our empirical data, examining how Romanian society elucidates the nature of “corruption” and its evolution over time. As a result, three stages can be identified: IPE as a tool for denouncing political adversaries, IEP as a source of political conflicts, and IEP as a public concern. Lastly, we draw conclusions regarding the applicability of our analytical model and its relevance.

2 Literature overview

First order of questions: how social science researchers themselves go about explaining the nature of the phenomenon and its persistence? Indeed, as we will see, in Romania, and also in ex-communist societies, the works of social scientists and experts are often mobilized by “laypeople” in the social struggles they engage in, regarding the utility of combating “corruption” and how to go about it. If such mobilizations take place, it is also because a certain number of interpretative patterns and normative judgments are spontaneously shared between some researchers and non-researchers. That is why, in the following lines, we offer a brief overview of the approaches available within the scientific and expert literature regarding the anti-corruption struggle in former communist countries and in Romania in particular. Two major bodies of work, as we have already mentioned, will emerge: those we will group under the label of “fatalistic” approaches, and those we will group under the label of “voluntarist” approaches. We will argue for the possibility of a third type of approach, in our view, properly sociological, whose characteristics and requirements we will attempt to determine.

2.1 Essentialism and culturalism: fatalistic approaches and their limits

The approaches developed in this section are part of the first group- that this research refers to as “fatalistic”- and they emphasize culturalist and essentialist understandings of the phenomenon of corruption in Romania. This perspective is generally reflected in conceiving corruption as a cultural trait, meaning it corresponds to societal norms, something accepted and even morally mandatory.

The questioning of the existence of a historical discourse of essentialist nature, which holds the past (recent or more distant) responsible for the widespread practices of corruption present within the political elite, is analyzed by a plurality of social scientists– historians, linguists, sociologists, and political scientists – in Central and Eastern Europe. According to this approach, more distant periods – specifically the Phanariote or communist eras – are deemed to have permeated the country with practices that persist to the present day and would serve as an explanation for the current situation of underdevelopment.

Following their logic, Gallagher (2005, p. 2) emphasizes the heavy influence of the communist legacy on political practices in the new democratic configuration. “In terms of exploitation, incompetence, and mismanagement of national resources, the communist regime (1946–1989) was the worst Romania has experienced. But many elements indicate that it intensified negative political behaviors that already existed and created new ones”. Developing a sociology of transition, Sandu (1996, p.21) underscores the influence that the former communist regime had on the current “political culture” and corrupt practices, through the development of an underground black market that gave rise to a new type of interpersonal relationships.

However, this approach is not specific to Romania. On the contrary, this discourse, attributing the widespread presence of corrupt practices to the Ottoman and communist past, can also be found in other societies in the Balkan region. Looking near the country’s Southern border, specifically in Bulgaria, studies like those of Gehl and Roth (2013) or Schüler (2013) show that informal practices have been and continue to be an integral part of everyday culture in Southeastern Europe, as an extension of its political culture. Thus, the Ottomans and communists have contributed to the creation of a community of people divided between “us” and “them,” the powerless and the victims against those in power, generally perceived as “maskari”.1 This type of essentialist studies reaches the conclusion that “Bulgaria entered the post-socialist period with a double historical legacy, that of the Ottoman era and half a century of communist rule, a legacy that has a lasting impact on the construction of society itself and the resulting social relations” (Gehl and Roth, 2013, p. 202). To summarize this approach, Iancu and Todorov (2018) identifies what we have just outlined as dominant approaches, recalling two categories of sources of corruption. On the one hand, the communist legacy is always considered as the “culprit in service,” (p. 15) and on the other hand, there is talk of the “notorious baksheesh Europe” (p. 15).

Having outlined this background, it is now appropriate to explain the limits of this approach from a sociological perspective and the relevance of using the label “fatalistic” to summarize it. We believe that the fatalistic approach perceives corruption as an element of democratic lag. Consequently, following Rubi Casals (2014), this article does not focus on presenting political corruption as an “inherent element of developing regimes or the deceptive North–South divide,” a source of division between Western European countries and the new democracies of Eastern Europe. Furthermore, we believe that understanding and explaining the presence of corruption in a culturalist manner specific to the Balkan region does not align with sociological thinking, as it proves highly deterministic, portraying this phenomenon as inevitable, and suggesting that these societies can never emancipate themselves from it.

2.2 Legalism and the rejection of local particularities: voluntarist approaches and their limits

Let us now consider the second dominant approach in Romania, which we refer to as “voluntarist.” This type of scientific discourse explains the construction of corruption as a public problem through the norm of “good governance experts,” to use the words of Blundo (2012), who emphasizes Western norms and values in this regard, through international institutions, and especially the European Union. This approach assumes a transfer of “good practices,” considered to be the foundation of the anti-corruption establishment in countries with a longer democratic tradition. It involves imposing frameworks and tools from “abroad” that would help address an existing “democratic lag.” For proponents of the voluntarist approach, putting forward the thesis of external conditionality (Bratu, 2016; Văduva, 2016) specifically that of the European Union, would explain the development of a legal and social framework for anti-corruption, the construction of the phenomenon as a public issue, as well as the local resistance to these efforts.

Nevertheless, there are voices that indicate it is not easy to fight the widespread corruption because certain constraints within Romanian society make anti-corruption efforts challenging. Michael Hein, among others, highlighted in 2015 how the progress in recent years in anti-corruption – following Romania’s accession to the European Union – is reflected only at the level of norms but not in actual practices. According to him, this is mainly explained “by political culture, persistent patrimonial networks, historical heritage, weak economic capabilities, and strong economic inequalities” (Hein, 2015, p.772).

In the end, we can observe that, according to the voluntarist approach, it is always the imposition of an external norm that will ultimately lead to the change in the indigenous norm regarding anti-corruption. The continuation of campaigns in this direction would be the key to success, ensuring the complete adaptation of local legal norms to European ones, which would then lead to a gradual change in behavior. Taking into account the moment of Romania’s accession to international structures, in attempting to trace the process of constructing the phenomenon of corruption as a public issue, is undoubtedly useful and cannot be ignored. However, this research diverges from this approach to try to demonstrate that the change in the local norm does not occur exclusively and primarily in relation to external pressure from international actors, as the desire to change the norm in this regard and adhere to the European one cannot be solely explained by the act of accession itself.

2.3 The sociological perspective: between social necessity and denaturalization

The ambition of this article is to go further and suggest a more reflective approach than the one proposed by fatalistic and voluntarist perspectives. The aim is to break away from essentialist logic and attempt to outline the relationship established between corruption and the new Romanian democracy after the fall of communism, without denying, of course, the importance of historical legacies and cultural factors. This entails asserting that there is a kind of “social imperative for corruption,” which would account for its widespread presence without, however, treating this imperative as inherent. Sociology, avoiding naturalization, aims to elucidate these social imperatives, revealing how the institution of corruption is sustained in social practices. Acknowledging a dynamic of change, this social imperative is neither predetermined nor everlasting.

Hence, the approach advocated by this study embodies a third perspective, which resonates with the constructivist view of phenomena (Dreyfus, 2002; Marton and Monier, 2017; Engels et al., 2018), as inferred by the reader. Additionally, other research such as that undertaken by Rothstein and Uslaner (2005) employs cross-national statistical data to introduce the idea of “social trust,” as an explanatory concept, demonstrating how corruption thrives amidst economic inequality, low trust, and inadequate government performance.

Compared to the constructivist perspective, without denying its merits, the approach proposed by this study, inspired by pragmatic sociology and the Durkheimian thought, aims to be more reflective. Here’s the explanation: by advocating for a non-mechanical holism proposed by Durkheim (1960), we consider that individuals’ reasoning can only be analyzed in relation to the community or society to which they wish to belong (Karsenti and Lemieux, 2017). Thus, by placing less emphasis on economic explanations, without ignoring their importance, this perspective aims to denaturalize the social order, proposing an analytical model that takes into account local specificities. Firstly, the Durkheimian tradition directs our attention toward the political and moral consequences of the growing division of labor. Secondly, pragmatic sociology encourages us to “follow the actors,” meaning to understand how they interpret phenomena related to corruption and discuss these matters among themselves. We will elaborate extensively on these two aspects of our approach and discuss their conceptual and methodological implications for our investigation.

Prior to embarking on this endeavor of theoretical grounding, it is imperative to state that our research embraces a Durkheimian perspective of “corruption,” wherein it is viewed as a social phenomenon characterized by a certain regularity, thereby implying a sense of “normalcy.”(Durkheim, 1960, pp. 65–72). Then, the Durkheimian tradition (Durkheim, 1960; Durkheim, 2013) will first lead us to prioritize a morphological approach to Romanian society and its evolution. In other words, we need to take into account the changes that have occurred in the structure of society. Secondly, we are led to consider how the proliferation of division of labor gives rise to new moral values and ideals or prompts their reevaluation and adaptation. More precisely, how can one explain the relationship that is established between the position occupied by a profession within the general division of labor and the predilection of its members for certain worldviews and ideologies? In this context, we need to delve into the process of “ideation” that has unfolded in Romania over the past five decades, driven by politicians and intellectuals. This ideation serves to rationalize the anti-corruption fight and link it to a particular vision of society. Additionally, we must examine how this ideation and its resonance among segments of the population are influenced by shifts in the division of labor. This approach will entail examining the socio-professional groups within society that actively oppose corruption and those that exhibit less or no interest. In accordance with Durkheimian thought, the increased division of social labor within Romanian society post-communism fosters the development of individualistic norms. Thus, the proliferation of social groups during the transition to democracy results in elevated individualism present in political engagements, individual accountability, and personal autonomy and therefore a heightened sensitivity to injustices stemming from corruption. Consequently, we believe this approach offers explanatory power and enhances predictability. Moreover, such reasoning can help to elucidate a non-contingent and non-random dynamic, highlighting the argument of society’s endogenous transformation. Thus, as society becomes more entrenched in norms of individualization, there is greater responsiveness to the issue of corruption, and consequently, the injustices it engenders.

The second theoretical standpoint which belongs to pragmatic sociology, urges us to capture how social actors interpret phenomena associated with IPEs and engage in discussions about them. Thus, the concept of politicization – understood as the production of descriptive and interpretive narratives, as well as the search for solutions (Cefaï, 1996, p. 48) – proves its analytical utility. As a consequence, adopting this a socio-historical approach allows a better understanding of how corruption has increasingly become a significant concern within Romanian society since the 1990s.

In practice, this analytical framework enables the examination of the operations through which participants in the public debate either normalize or denormalize corruption. Therefore, this approach not only has the ambition of putting forward the specificities of the anti-corruption fight in post-communist societies but it can also offer an endogenous model of analysis of the phenomenon in societies with a longer democratic tradition.

3 Aims and methodology

From a methodological perspective, it’s imperative to emphasize the importance of applying the principle of symmetry (Lemieux, 2018a,b) in all these analyses. This entails granting equal status to both social actors who perceive corruption as a concern for the new democratic regime and those who do not prioritize this matter, without prejudging the superiority of one over the other in practice or principle. This approach enables the examination of the relation established between the two of them. Therefore, we need to study in detail and without preconceptions how actors (activists, media, politicians, etc.) demonstrate to each other the existence of corruption and denounce it or not.

Without this principle of symmetry, the sociological perspective, as presented above, would be a compromised because instead of focusing on describing and understanding social actions, the focus becomes to criticize them. Hence, during the development of this research, we found it crucial to reflect on the appropriateness of the term “corruption.”

This term is broad and polysemic. Legally, it has a narrow definition, while its common usage is more expansive and varied. Consequently, comprehensive definitions of corruption beyond the legal perspective have been scarce. According to Mark Philip (2015), this is due to the inherently normative nature of “corruption” and the emotionally charged perceptions surrounding it.

Given the concerns and negative connotations associated with the term “corruption,” we question its appropriateness for a symmetrical analysis of two modernizing projects. Despite the formal existence of the term in Romanian during Nicolae Ceaușescu’s era, Party propaganda portrayed corruption as an exogenous concept, leading to its limited use by social actors. This highlights the need for a more neutral and empirical term to describe these practices during both the communist period and the post-Revolution era. We propose “illegal personal enrichments” (IPE) as a more flexible and relevant label for the Romanian context. This term also captures the persistent inequality among citizens from the communist era to the transition to democracy, providing insight into societal tolerance for this disparity.

To show the evolution of IPE as a public issue in post-communist Romania, we opted for a qualitative methodology, more precisely discourse analysis of mainly the media debates. Considering the long period of time investigated, the discourse analysis of public media will focus on critical junctures. Due to the absence of digitalized Romanian journals, the research involved examining the newspapers issue by issue to identify the relevant articles. In this perspective, being guided by the idea that corruption scandals “reveal the vulnerability of the normative order” (De Blic and Lemieux, 2005, p. 11) as moments when actors will test their common sense of right and wrong this article focuses on the study of four major scandals that occurred over the past forty years. Various inclusion and exclusion criteria led to the selection of four focal points, among many others existing “corruption scandals” during the post-communist Romanian history.

“The Wine Affair,” dating back to 1978, holds the interest of immersing us in the communist era and allows us to question not only the existence, in Ceaucescu’s Romania, of forms of illegal personal enrichment, but it also is one of the rare moments when IPE take a visible and publicly recognizable form under the communist regime. More specifically, it allows us to observe the transformations in the discourse of relativizing IPE, particularly the adjustments made at the boundary between what is considered “normal” and “abnormal” practice, before and after the fall of the Ceausescu regime.

In the 1990s, Bancorex is analyzed as the first “big corruption scandal” to break out in the media, initiating a series of subsequent scandals as a result of the privatization process. On one hand, this case serves as a pretext to understand the relationship with the former communist regime and the perpetuation of its elites through the FSN (The National Salvation Front) power. On the other hand, it also marks the first political instrumentalization of IPE – in the context of the initial alternation of power, with the electoral victory of the Romanian Democratic Convention (CDR) – highlighting the relationship between Bancorex and the Văcăroiu government (PSDR).

After Traian Băsescu’s victory in the 2004 presidential elections, driven by an anti-corruption agenda, the main political divide in post-revolutionary Romania, previously centered on ties to the Old Regime, began to shift. With no clear right–left ideological distinction, the focus turned to corruption allegations against political rivals. Băsescu’s campaign targeted the legacy of the preceding four-year social-democratic government, led by Adrian Năstase, which the media often equated with “governmental corruption.” This justifies the analysis of three cases involving Năstase.

In the Zambaccian scandal (2004), prosecutors accused Năstase of receiving $630,000 in bribes from Irina Jianu to secure her position as chief inspector of the State Building Inspection (Năstase, 2005, p.5). In June 2006, the Aunt Tamara scandal saw Năstase facing new bribery charges. On July 9, 2008, the National Anticorruption Directorate (DNA) launched the Trofeul Calității case against him, accusing him of illicitly financing his electoral campaign and abusing his political office and party position. Năstase’s subsequent conviction made him the highest-ranking official imprisoned for corruption in Romania, a development that resonated significantly in the national press and within the European Union.

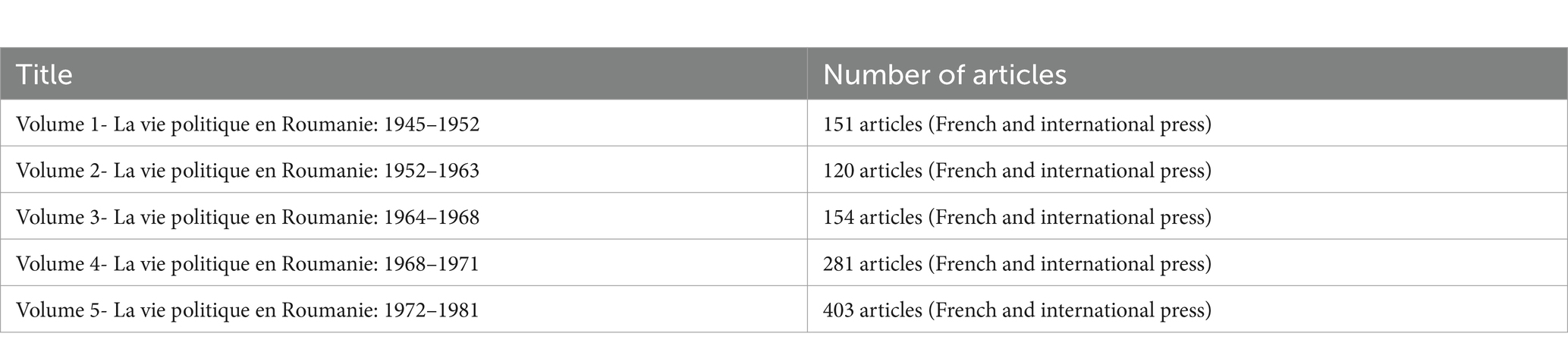

On October 30, 2015, the Colectiv nightclub fire, which killed 64 and injured 147, ignited protests under the slogan “Corruption Kills.” This marked a shift in public attitude, as civil society blamed officials for allowing unsafe conditions. The fire catalyzed the anti-corruption movement, peaking in early 2017 with the #rezist protests against the social-democratic government’s attempts to weaken anti-corruption laws. To investigate the politicization of IPE in the Romanian society, we primarily rely on press archives. For the communist period, two categories of press archives are analyzed. On one hand, there is the national communist press, available in print at the Central University Library of Bucharest. This involves the study of two publications from that time: Scânteia (The Spark) – the most widely circulated national daily at the time, exclusively dedicated to political issues, and Flacăra (The Flame) – a weekly magazine covering artistic, literary, and social themes. On the other hand, this research uses international press, centralized by the archives of Sciences Po Paris. Specifically, it involves the press file titled “La vie politique en Roumanie de 1945 à 1981,” (The Romanian political life between 1945 and 1981) which consists of 5 digitized volumes (see Appendix Table A1).

As for the period starting from 1989, three national publications have been chosen: Romania Libera (Free Romania)- appearing as early as December 22, the daily newspaper immediately becomes the bearer of a strong anti-communist message, Evenimentul Zilei (The event of the day)- a newly introduced tabloid in 1992, initially taking an anti-communist position, and Adevărul (The Truth) – the successor to the Scânteia newspaper (the official press outlet of the Communist Party) this newspaper supports the FSN and presents a critical discourse toward anti-communist forces. All publications are available in print at the Central University Library of Bucharest. This corpus allows for an examination of the variation in media discourse based on each publication of the time, as well as its connection to power, given that the politicization of the media was a significant issue during this period (Gross, 2015). The limit of this research has been the lack of digitization of Romanian press archives, preventing a quantitative and more systematic investigation that could provide a very useful overview.

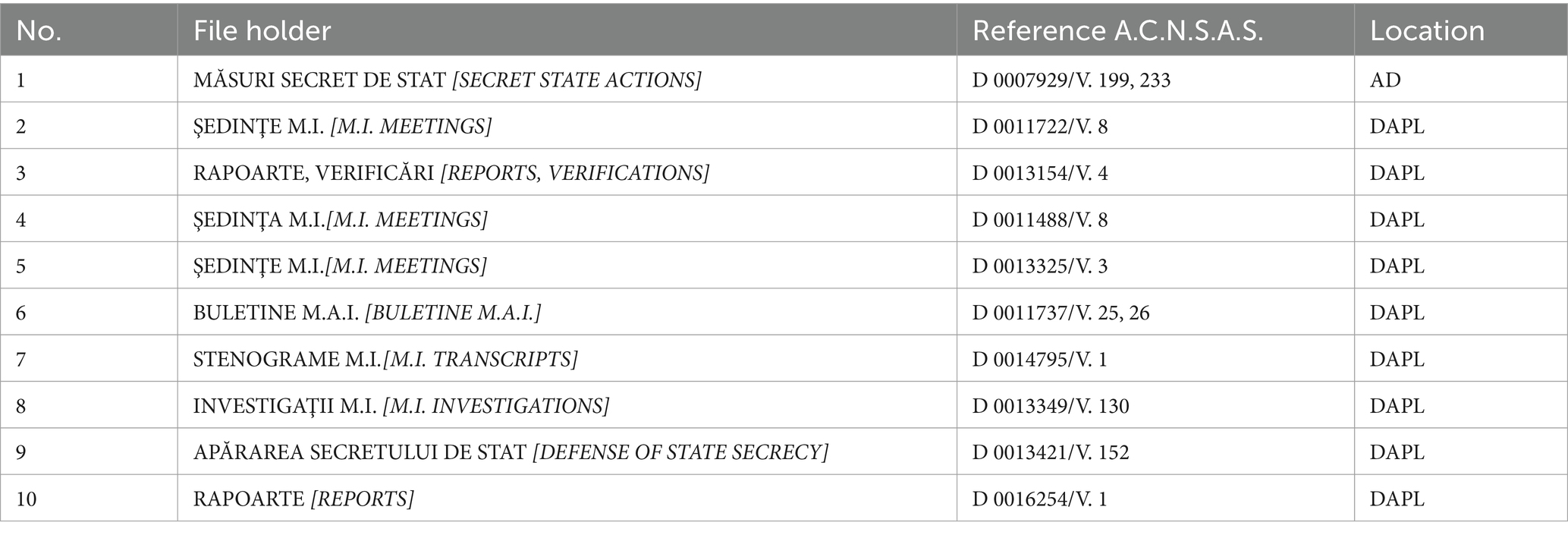

The press discourse is complemented by official texts, legal documents, information bulletins, and meetings of the Ministry of the Interior condemning certain illicit practices, available in the archives of the National Council for the Study of the Security Archives (Appendix Table A2).

The Durkheimian tradition will lead us, first and foremost, to prioritize a morphological approach to Romanian society and its evolution in order to link it to the politicization of the phenomenon of IPE. In other words, we will need to analyze the changes that have occurred in the structure of society. To do this, we will make use of statistical data that allows us to identify general trends, presented with the aim of demonstrating the employment dynamics by sector of activity, both for the communist and democratic periods. The data used for this purpose is provided by secondary sources such as the Central Electoral Bureau, the National Agency for Workforce Occupation, and the National Institute of Statistics as well as other sociological researches.

To clarify, our approach is not to conduct thorough historical research, which would require extensive archival consultation and a reconstruction of society’s overall state during each scandal. Instead, our goal is to trace the general evolution and identify key milestones that have shaped the rise of anti-corruption awareness in Romanian society over the past four decades. Therefore, the interest is in selecting historically significant moments—particularly highly publicized and impactful “corruption scandals”—and utilizing press archives related to these cases to search for signs of social actors’ reflexivity on the issue. By analyzing these focal points, three stages of politicization of IPEs can be identified: IPE as a discursive tool for denouncing political adversaries, IEP as a generator of political conflicts, and IEP as a public issue.

4 Analysis

4.1 “Illegal personal enrichment” as a discursive tool for denouncing political adversaries

Using the term “corruption” to describe illicit practices during Nicolae Ceaușescu’s era might appear surprising to a Romanian who lived through the communist regime. Despite its formal inclusion in dictionaries, this word wasn’t commonly used in everyday language before 1989. Moreover, reading the official party publication, Scânteia, often shows endeavors not to use the term to describe everyday realities in Romania. Nevertheless, the newspaper’s articles primarily employ the term to depict issues related to foreign political life. Thus, sections such as “The world of capital in its true light” or “International life” repeatedly report on the existence of business affairs and corruption scandals shaking the Western world. In this regard, behaviors associated with corruption are described as an integral part of the daily life of capitalist societies, carriers of illusions, intrinsically decadent, and imbued with mafia-like elements. Thus, the term “corruption” was mostly associated with “Western” matters and customs officers’ dealings, making it a somewhat technical concept within police jargon. However, the purpose of this section was to demonstrate that practices similar to what we now label as “corruption” existed within socialist society, even though they were not explicitly labelled as such. Examining these practices, which we have grouped under the label of “illegal personal enrichments,” revealed how publicly and officially denouncing such exchanges during Ceaușescu’s rule served to reaffirm the existence and fundamental legitimacy of socialist property that needed protection from foreign and corrupting influences. This comes as a result of the communist society being ideologically rooted in a fundamental contradiction between individual monopolization of goods and socialist ethics.

Consequently, while illegal personal enrichments were criticized in both propaganda discourse and the law (Law no. 3, 20 April 1972, chapter 6, art. 71), they were not explicitly referred to as “corruption.” Nevertheless, the presence of foreign media discourse exposing systemic corruption in Romania (Poulet, Le matin,1982; Fejtő, 1981) forced Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime to respond. Therefore, starting from the 1970s, addressing this issue became a priority and an active concern for the Romanian state, leading to the criminalization and denunciation of so-called “antisocial” practices such as bribery, tipping, speculation, and social parasitism as the Executive board meetings of the leadership council of the Ministry of Internal Affairs show (1981).

As Holstein and Miller (1990) rightly emphasize, establishing a direct link between a social problem and a category of victims contributes to its prominence in the public sphere. This leads to what Barthe (2017) calls a “causality policy,” which encompasses all actions aimed at establishing direct connections between the facts behind the problem and the resulting harm. Having that in mind, the main identified victim of “illegal personal enrichments” is the communist state itself, specifically the “socialist property,” and implicitly, all “honest” citizens. “Illegal personal enrichments “primarily lead to higher prices, shortages, and repercussions on service quality and fair wage principles.

“There are a significant number of services whose prices are set by the state for the welfare of citizens, where the practice of "bribery" causes prices to increase. […] People don't realize that they themselves are the victims, that they are mistaken, and that they contribute to deceiving others through such actions.” (Radu, 1971, p. 5)

Communist society thus faces two dangers: an internal one rooted in the past—the Phanariot and bourgeois era—that still exists in individuals who persist in seeking privileges, and an external one, the ideological enemy, the “bourgeoise” element developing within society (Scânteia, 4 April 1981, p. 2). This element is an enthusiast of corrupt practices typical of capitalist societies, based on individual enrichment and resource monopolization. Victims of such behavior are predominantly found in urban areas, among socio-professional categories that allow for a degree of autonomy, often due to contact with Western norms (Editorial office of Scânteia, 1974, p.5).

“The wine scandal” is a relevant case from this perspective. In the 1970s, the name of Gheorghe Ștefănescu was well-known in Bucharest, especially among the people in the city center. To begin with, he was the manager of the warehouse for wine and spirits sales to the public at 325 Calea Griviței, in the 8th district of the capital, where he sold bulk wine. Among his regular customers were high-ranking politicians and members of the Securitate (the Romanian secret police); that’s how popular and appreciated this wine store was. Paradoxically, it was precisely here that a major case of bootleg alcohol took place, which later became known as “the largest affair of the Nicolae Ceaușescu era” (Stănilă, 2019). In March 1984, this story inspired the script for a propaganda film titled “The Secret of Bacchus,” a humorous production directed by the renowned screenwriter Titus Popovici, who was close to Nicolae Ceaușescu. The film featured a very popular cast at the time and remains well-known and widely broadcast in Romania to this day. Hence, “The wine scandal” was one of the rare moments when the communist press openly discussed what we can now refer to as both big and petty corruption.

The case of Gheorghe Ștefănescu serves as an example of how the regime used this situation to point out the presence of “parasitic elements”2 within society, which were believed to be undermining the national economy. Despite being minoritarian, these individuals were considered a significant factor in the widespread shortages that afflicted Romania in the late 1970s. The media and cinema portrayed individuals like Ștefănescu as outsiders, associating their corrupt behavior with capitalist societies marked by social inequality and the accumulation of wealth at the expense of others (Cristache, 1978).

“The communists in the department, along with honest workers, are right to question this exceptional case. Ștefănescu is truly a swindler, a bandit. His four previous convictions speak volumes about him: he wanted to steal, deceive; he was apprehended and placed among the ranks of swindlers. However, this case highlights the issue of others, those who—consciously or by omission—facilitated the actions of the bandits and allowed the unfolding of this illicit activity.” (Florescu, Scânteia, 1978).

By turning the “wine affair” into a political issue, the Romanian state shaped a public discourse that encompassed both small daily instances of illegal enrichment and more extensive clientelist networks. The regime’s goal was to address the problem of “illegal personal enrichment” without directly challenging the core issue criticized by international media – the privileges of the elite and the nomenklatura. Nevertheless, the Party used this scandal to reveal certain deviant cases within the ruling “new class,” notably through Tudor Bălătică, the First Secretary of the Communist Party Committee in the 8th district and a central figure in Ștefănescu’s network (Florescu, 1978). Despite the press directly addressing the political associates of the accused, the supposed uniqueness of the situation failed to provide evidence of the injustices stemming from certain privileges held by the nomenklatura.

Thus, our argument is that, discursively, “illegal personal enrichments” were criticized during Ceaușescu’s era as well as after the regime’s fall. However, there is a fundamental difference between the articulation of public discourse under communism and that in a liberal democracy. Before 1989, the regime sought to monopolize both the description and critique of these practices. Starting from the 1990s, which marked the opening of public discourse to various actors, the phenomenon began to be politicized differently, in a pluralistic manner, encompassing multiple competing discourses. Therefore, we consider that analyzing the last decades of communism enables us to identify a historical shift in a dual process. The official discourse on illegal personal enrichments during the communist period suggests that this phenomenon was the result of “abnormal” individuals. This discursive dynamic underwent a complete transformation after 1989. What was once presented as an isolated, pathological, and relatively manageable issue in Ceaușescu’s Romania—because it concerned socialist goods and was in every citizen’s interest to correct their behavior—later emerged as a systemic, widespread phenomenon in which individuals had little power to act. This implies a different relationship with political elites, which were now considered the main source of “corruption,” with every individual seen as a victim.

In conclusion, IPE becomes a discursive tool for denouncing political adversaries, manipulated by both the communists and liberal democracies. “The reality” of corruption acts varies depending on the interests of the actors manipulating this label. Thus, as stated by Petr Kupka and Naxera (2023) for the Czech case “beyond existing knowledge on corruption, we could say that corruption has become one of the primary lenses through which the negative effects of the post-communist transition are interpreted. In this respect, corruption can be read as a historical discourse.” (p. 24).

4.2 “Illegal personal enrichment” as a political conflict generator

Faced with constant and growing criticism from the liberal modernization model, practices associated with illegal enrichment emerge in communist propaganda discourse as behaviors isolated to individuals who fail to integrate professional norms, ethics, and socialist morals. However, unintentionally, through a discourse on illegal enrichment linked to social parasitism, the state proceeds to de-individualize misfortune and thus contributes to an initial attempt at politicizing illegal enrichment. Now, it is necessary to take a further step to understand what has become of this denunciation of illegal enrichment after the fall of communism and how this legacy is instrumentalized in relation to the fight against corruption, starting from 1990.

Following the downfall of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s communist regime, in the absence of a clear ideological divide between the “left” and the “right,” the focal point of political discourse—especially within partisan and media circles—lies in the relationships of new political actors with the Old Regime. Thus, shortly after the Revolution, “anticommunism” takes on an ideological value, embodied in this case by the so-called “historical” political parties. Regarding this initial complexity of the post-revolutionary Romanian political scene, Radu, A. (2010) suggests that it would be legitimate to speak of a “Romanian specificity of the communist-anticommunist divide,” a division that did not exist before 1989 and was subsequently manifested by the opposition between “the neo-communist revolutionaries of the FSN and the historical parties.”

In this context, one could ask what was the socio-economic and demographic profile of the individuals who endorsed the anti-communist agenda? A study published in 2011, analyzing the political orientation of Romanians from 1990 to 2009 – based on data centralized by the Central Electoral Bureau, the National Agency for Workforce Occupation and the National Institute of Statistics (Boamfă, 2011) yields relevant conclusions for our research. Taking into account elements such as age, ethnicity, religion, and profession of the population, the education of the interviewees, their occupation, income, and their willingness to actively engage in public demonstrations following the revolutionary moment, the mentioned study outlines the median profile of individuals more inclined to support the “anti-communist” project and those who did not conceived the presence of former communist elite in the new democratic configuration as a problem. It appears that the latter category was formed by rural population engaged in the primary sector, those most profoundly impacted by the socio-economic changes triggered by communism’s collapse, guided by Orthodox Christian morality. Starting from 1992, this includes those who are unemployed and have difficulty finding employment. Conversely, the “anti-communist” agenda garners favor among urban population working in the secondary and tertiary sectors. This is an educated population – mostly with higher education – with an above-average standard of living, generally working in non-agrarian sectors. Additionally, the Hungarian minority, characterized by values related to Catholic and Calvinist morality, is concentrated in the eastern part of Transylvania (Boamfă, 2011).

In this political context of the transition period, as our observations reveal from the press analysis, illegal personal enrichments were regarded as an “ordinary social fact” (Hurezeanu, 1996), a characteristic of both the era and the region. It is worth emphasizing that this type of condemning IPE implies corruption among the elite. Through examples of banking system scandals- directly linked to the privatization of the banking system- we aim to demonstrate how this theme was manipulated during the democratization, highlighting the rising influence of a third actor, the press.

“The phenomenon of corruption is perceived in today's Romania as a kind of unavoidable alternative to normality. It is most often seen as a multi-faceted manifestation of the abrupt and erratic transition from a planned economy and a police state to a market economy and an open society. In some reflections, especially in the press, it appears as a related occupation of parliamentarians, bankers, capitalists, politicians from the ruling party, ministers, politicians from coalition parties- resembling the ‘Directorate of the sixth year after Ceaușescu.’" (Hurezeanu, 1996)

This press fragment should be understood in the context of the emerging scandals within the banking system, which have shed light on various aspects of Romania’s political landscape that were previously overlooked. Their exposure has sparked extensive media discussions regarding the connections between the PDSR (Party of Social Democracy in Romania) – heir of FSN- and corrupt activities, especially within the banking sector. Additionally, these scandals’ historical origins, which are linked to the former Communist Party, have become subjects of debate. This discourse is further complicated by the change in political leadership. It wasn’t until the 1996 election campaign that IPE started to gain more prominence in public discourse, eventually becoming a key government concern. The press played a crucial role in uncovering these “corruption cases,” subsequently turning them into significant scandals, which effectively placed the issue of illegal enrichment practices on the political agenda, especially after the change in government. This period of transition and the 1996 election campaign (won by Emil Constantinescu and the Democratic Convention – an anti-communist political alliance) represent the first successful exploitation of “corruption scandals” for political gain, although they still remained secondary in significance compared to the central cleavage between anti-communism and neo-communism.

Additionally, these scandals emphasize the significant problem of privatizing state-owned assets, which is viewed as the main source of IPE (Tismăneanu, 2007). As a result, an exclusively economic understanding of IPE emerges during the period being examined, a perspective that evolves after the 2000s. This realization prompts a wider conversation about defining the limit between the public and private sectors within a democratic framework. Ultimately, the primary focus of the discussion shifts toward “institutional corruption,” which erodes public trust in state institutions.

In conclusion, it can be asserted that the anti-communist project instrumentalizes the theme of “corruption” to secure electoral victories, aligning with Western norms and employing a narrative that portrays IPEs as systemic among former communist elites who have transitioned into capitalists. What’s noteworthy is that, following these scandals, a new perspective on how “corruption” is conceived and defined has emerged. Notably, from the 2000s onward, this issue gained more prominence and became increasingly visible.

“Ongoing legal proceedings against prominent figures in corruption suggest a shift in the justice system. This marks a notable political commitment to address Romania's crucial issue. But, the government's failure to confront Romanian oligarchs highlights the widespread nature of this problem. These major corrupt figures are like inoperable tumors in our ailing society: the doctor opens the patient, looks, whistles in amazement, stitches them up, and sends them home.” (Cartarescu, 2005).

As one can see from reading this press fragment, the normalization of illegal enrichment as a defining feature of the transition period has gradually changed. Thus, despite the prevailing fatalism associated with the normalization of this phenomenon, we perceive a form of reflection emerging around the issue of illegal enrichment. This helps us underscore the central hypothesis of our research, which posits that the growing intolerance toward IPE is not solely or primarily a result of external pressures from the European Union but rather originates from internal transformations within Romanian society, making it more receptive to these external pressures.

Through an analysis of the “corruption scandals” related to former Prime Minister Adrian Năstase and the interpretations put forth by various actors, we aim to demonstrate how the increasing division of labor and the subsequent evolution of norms related to individualization within social dynamics have gradually influenced the attitudes and sensitivities of different social groups comprising Romanian society regarding “the illegal personal enrichments.” More precisely, the confrontation between the former social-democratic Prime Minister, Adrian Năstase, involved in three “corruption scandals” (from 2004 to 2008) and Traian Basescu (president of Romania from 2004 to 2014 and champion of the anti-corruption fight) leads to a dynamic relevant to our research. This conflict must be placed in the socio-economic context of Romania in the 2000s, with the increasingly visible rise of an urban, educated, and private-sector-active middle class. The 2004 elections, as indicated by Cistelecan (2014), mark the first electoral moment when social issues take a backseat in discursive terms, being replaced by the ideas of transparency and good governance. This discourse primarily tackles a social actor who is gaining more and more influence, which is what makes this shift feasible: a growing middle class that occupies an increasingly significant part of the electorate.

“Băsescu succeeded in convincing the urban, young, dynamic, and change-seeking electorate that he can represent their interests and free them from the stagnation of the Năstase government” (Clucer, 2004). This actually represents the foundations of the anti-corruption modernization project: the opposition between the individual and the system, portrayed as corrupt and distant from society.

“Of all the parties that parade on the political stage, only one consistently defends its corrupt members: THE PSD. As the biological offspring of the odious FSN, the party inherited and led by Ion Iliescu continues to provide evidence of its solidarity with criminals.” (Cartianu, 2012)

For this electorate, the illegal personal enrichments became a form of injustice rather than a norm, specific to the region and the transition period. From an ideological standpoint, we can say that the era of Traian Băsescu laid the groundwork for Romanian neoliberalism, which resonated strongly with this middle class that identifies with Western values (Radulescu, 2008, p. 8).

In the face of this issue, the supporters of Adrian Năstase, contrast social concerns and the living conditions of Romanians. Consequently, it primarily addresses the working-class population, those without means, who have been neglected by the state. For them, moral issues related to illegal enrichment practices and good governance are not a priority, as no connection is made between these issues and the precarious living. So, in the words of Năstase (2006, p.143):

“Romania has fewer cases of extreme poverty than Brazil, but if we continue to focus solely on the wealthiest three hundred individuals and not on the one million poorest Romanians, we will witness the breakdown of bridges, the emergence of exclusion, and, implicitly, violence. In our country, the analysis of such a serious issue occurs, at most, in academic circles or within civil society. The current government has not initiated any studies and clearly lacks a strategy in this regard. In fact, for the current political leadership, this issue doesn't even register. They consistently wave the flag of European integration, understood solely as a bundle of paperwork on which bureaucrats in Bucharest or Brussels place their focus.”

As shown above, IPE can be understood as a conflict generator- heir of the anti-communist – neo-communist cleavage- that, since the 2000s, has oversimplified the depiction of the social landscape.

4.3 “Illegal personal enrichment” as a public issue

It is now time to explore the politicization of IPE starting from 2012. We’ve pinpointed this year as a turning point when the theme of “anti-corruption” gains momentum and becomes increasingly prominent in the public discourse. From this moment on, Romania has experienced a series of popular protests. In 2012, Romanians took to the streets to protest against austerity measures taken by the government. Between September 2013 and February 2014, new demonstrations occurred against the PSD government of Victor Ponta, who, despite his electoral promises, gave green light to mining and shale gas extraction at Roșia Montană, Romania’s largest gold mine, by a Canadian corporation. This decision was seen as detrimental to the environment and the national economy. At the end of 2015, a fire at the Colectiv nightclub led to a major political scandal, ultimately resulting in the fall of the Victor Ponta government. “Deprived of emergency exits, spectators found themselves trapped in the concert hall. The tragedy claimed 27 lives and left nearly 150 injured, with 35 succumbing to their injuries in the following weeks in the capital’s overloaded and severely underequipped hospitals. This incident highlighted the state of decay in the country and its hospitals, where, for instance, diluted disinfectant was used to cut costs” (Roux, 2022) wrote the international press. On February 13, 2017, Romanians took to the streets once again, this time against a new PSD government, led by Sorin Grindeanu, following the government’s attempt to pass Ordonanța 13 (Governmental ordinance no. 13). This was an executive decision to amend the Penal Code, with the most contested amendment by civil society being related to public office abuse, which would no longer have been considered a criminal offense unless the damage exceeded 200,000 lei. This timeline of protest movements culminated in the “great gathering of the diaspora” (France 24, 2018) on August 10, 2018, when a large number of Romanian expatriates came to claim “Justice, not corruption!” These movements were suppressed by the military police in a highly violent manner, using tear gas, a level of violence deemed unprecedented in Romania’s post-communist history.

Following Mărgărit’s (2019) perspective, all these protests, while initially rooted in specific issues, eventually turned into movements with anti-government and anti-corruption narratives and demands. As a result, the public started seeing these isolated problems as signs of deeper structural issues within Romanian society, which political leaders had failed to address.

Taken separately, we believe that the Colectiv fire scandal plays a very significant role in the local construction of “corruption” as a public issue because it sparks a comprehensive debate about the challenges raised by the systemic presence of this phenomenon and thus serves as an actual illustration of the price paid by citizens. A study conducted by Gubernat and Rammelt (2021) attest who are the Romanians who have rallied against the injustices created by a perceived corrupt and flawed political system.

“Since 2012, people aged between twenty-five and forty, though previously seeming to be discouraged from civic involvement, strongly contributed to the waves of mobilization Romania has witnessed in the past few years. A new generation of protesters seemed to populate the public sphere. When assessing the sociodemographic profile of the protesters, it was found that they mainly belong to the age cohort twenty-two to forty-five, are highly educated, and their unconventional political engagement is characterized by a strong continuity over this period, with participation in prior protests. (…) Romanian analysists assert that the protests have been taken over by the ‘right-leaning middle-class,’ being the culmination of a wave of ‘middle-class activism’ prior to 2017.”

As we can see, those citizens preoccupied by issues related to IPE in 2015 are the same urban, young, dynamic, and change-seeking middle class that has been gaining more influence and autonomy since the era of Traian Băsescu. The empowerment of this middle class and its increasingly significant weight is proven by the emergence of a new “anti-corruption” political party, Uniunea Salvați România (Save Romania Union) founded in 2016, which attempts to represent its interests. “In Romania, the USR should be considered as adapting to the populist environment by recombining salient issues of anticommunism and the fight against corruption in a general anti-elitist approach” (Dragoman, 2020, p. 2). This aspect becomes even more visible when considering that party members have actively took part in social movements such as Colectiv.

Despite this citizen mobilization, opinions are not unanimous when it comes to assigning responsibility for this tragedy. Victor Ponta, the Prime Minister at that time, did not miss the opportunity to denounce a real witch hunt that has been triggered by this national tragedy, which, in itself, hinders the desire for justice. Here is the message he posted on Facebook:

“We all know that the Colectiv tragedy was exploited for political purposes to replace a government (…). That's why no one cared about seeking the truth or achieving justice! We all know that Mayor Piedone is absolutely not guilty (if Colectiv tragedy was to happen in Sibiu or Cluj, I don't think the mayor would be in prison). We all know that people are still burning in hospitals today without anyone being held accountable. We all know that concerts are still being held in basements and wholly inadequate venues. We all know we didn't want to hear about Colectiv anymore to avoid remembering the manipulation and the cynical way in which the lost lives were used. We all know that today, 'corruption no longer kills,' just like lies, stupidity, incompetence, and insensitivity. We've imprisoned Piedone and the club owners, and we carry on as if nothing happened. It's extremely sad!" (Ponta, 2022).

5 Conclusion

Establishing IPE as a public issue will continue beyond this study, extending past our analysis of the Colectiv incident. However, this research has shown how the increasing division of labor and rise in individualization within social relations have progressively shaped the tendencies and sensitivities of various social groups in Romanian society, especially concerning “illegal personal enrichment.”

Firstly, approaching “corruption” in a flexible manner and seeking to reconstruct the social dynamics behind the increasing denunciation of the illegal personal enrichments allowed us to identify the evolution of their politicization within the Romanian society, over the las forty years. Consequently, three dominant approaches emerged. During the last years of Nicolae Ceausescu’s communist regime and the early stages of transitioning to democracy, the issue of IPE was used as a means to discredit political opponents. In the absence of a clear left–right political divide, the exposure of illegal personal enrichment sparked conflicts, stemming from the historical cleavage between anti-communists and neo-communists. This eventually led to its recognition as a significant public issue, particularly evident from 2012 onwards.

A second outcome of this research involves an attempt to identify the social actors that align with “anti-corruption project” as it garners increasing momentum. This approach moves away from general and caricatured discourses on Romanian society, which either portray it as entirely supportive of corrupt practices or entirely opposed. This reveals that the denunciation of IPE within the social structure is not random or contingent; nor it is a product of chance. This observation reinforces the argument that the increased sensitivity to anti-corruption in Romania is primarily a result of an endogenous transformation within society. More precisely, it arises from the development of urban and intellectual middle-class layers that appear to be a more inclined to consider IPE a significant issue. These individuals belong to a middle class relatively isolated from material necessity, emancipated from rural and traditional integration communities, and oriented toward norms linked to normative individualism. This is reflected in their commitment to egalitarianism and the idea of justice. This educated middle class, sometimes educated abroad, is more likely to aspire to European standards of transparency and view Western liberal values as morally desirable and a key to successful governance in democratic regimes. Conversely, the fight against corruption appears to be less of a priority less-educated Romanians, mainly from the lower socio-economic classes, particularly rural areas, who often live in difficult conditions and occasionally within underprivileged social environments. Economically less autonomous and less inclined toward normative individualism in its liberal form, these individuals aspire to modernization in their living conditions without undermining the forms of solidarity and mutual assistance they benefit from.

A third and final outcome of this paper pertains to shedding light on how the relative political weight of supporters of “the anti-corruption fight” is influenced by changes in social structure. Thus, an educated middle class has gained increasing visibility in recent years in Romania and, by growing in number, has led to anti-corruption issues occupying a more prominent place on the political agenda, event for its opponents, which, in reaction, are now forced to justify practices that did not particularly need justification before. There is an explanatory aspect and a predictive aspect to this argument. The explanatory aspect is that the rise in anti-corruption sensitivity in Romania in recent decades as primarily resulting from the numerical growth of urban intellectual middle classes and their increasing interdependence with other segments of society. The aspect that is predictive is the forecast that if the division of labor further increases in Romania in the future, there is a likelihood that intolerance toward illegal personal enrichment phenomena will also increase.

In this regard, we believe that this research offers an analytical model that could be tested in other contexts and with additional empirical data. To study the denunciation of IPEs both during the communist regime and in the post-communist era, it would be valuable to shed light on more local dynamics outside the capital and especially in rural areas. For the present work, we predominantly focused on analyzing the phenomenon by examining major scandals that involved the so called “big corruption,” and that had national significance. Additionally, citizen mobilizations against IPE primarily occurred in Romania’s major cities. It is also in these urban centers that associations dedicated to anti-corruption work emerged. This observation is consistent with the idea that an anti-corruption sensitivity is mainly driven by urban intellectual middle classes. However, it is undoubtedly necessary, precisely for this reason, to investigate further into the situation at the other end of the social spectrum, particularly among lower rural classes. Moreover, additional ethnographic studies could provide data via interviews and observations, potentially proving highly valuable in validating this analytical model.

Similarly, a comparative study among several countries in the region would be useful to test the analytical model. Specifically, comparing with the Bulgarian case could provide a good space for discussion. Besides the shared experience of communism in the past, events from the recent history of both countries would justify the interest in this comparison. In 2004, Romania and Bulgaria were supposed to join the European Union alongside ten other Central and Eastern European countries. However, following monitoring reports, the accession was postponed for three years, until 2007. Among the reasons cited at the time, those recurrently found in both cases relate to “corruption” and flaws in the judicial system. In this regard, the two countries have long been regarded in the literature as the most similar in terms of deficient political representation. Furthermore, the recent years have been marked, in both countries, by protests against “the corruption” of political elites. Despite the differing scale of anti-corruption social movements, the issue of “corruption” remains significant in both cases. As Todorov (2018) points out, “in Romania, these citizen mobilizations have become recurrent; in Bulgaria, to a lesser extent, civil society has also been mobilized against corruption.”

In this context, we will conclude expressing the desire to transcend both the fatalistic approaches of IPE and the voluntarist ones- articulated by scientists and think tanks, and still dominant in Romania. When it comes to the latter, we believe that a sociological approach helps us understand the limitations of the rules advocated by organizations like Transparency International, the EU, the World Bank, or certain Western governments. It’s not that these rules are necessarily bad, but if an analysis is solely based on political and legal reasoning, it overlooks the factors within the society that either enable or hinder the adoption of these rules.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AO: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Blundo, G. (2012). “Le roi n’est pas un parent. Les multiples redevabilités au sein de l’État postcolonial en Afrique” in Faire des sciences sociales. Critiquer. eds. P. Haag and C. Lemieux (Paris: OpenEdition Books), 59–86.

Boamfă, I. (2011). Orientation of the voters in the presidential elections in Romania 1990–2009. Forum Geographic 10.

Bratu, R. (2016). Corruption, informality and entrepreneurship in Romania. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 279.

Cartianu, G. (2012). Trofeul Cantității: Năstase n-are oua, Adevărul. Available at: https://adevarul.ro/blogurile-adevarul/trofeul-cantitatii-nastase-n-are-oua-650408.html (Accessed March 17, 2023).

Cefaï, D. (1996). La construction des problèmes publics. Définitions de situations dans des arènes publiques. Réseaux 14, 43–66. doi: 10.3406/reso.1996.3684

Cistelecan, A. (2014). “Ideologia Băsescu” in Epoca Traian Bãsescu. eds. F. Poenaru and C. Rogozanu (Tact: Cluj Napoca), 69–109.

De Blic, D., and Lemieux, C. (2005). Le scandale comme épreuve. Éléments de sociologie pragmatique. Politix 71, 9–38. doi: 10.3917/pox.071.0009

Dragoman, D. (2020). Save Romania union and the persistent populism in Romania. Problems of Post- Communism 68, 303–314. doi: 10.1080/10758216.2020.1781540

Durkheim, É. (2013). De la division du travail social. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 420.

Engels, J. I., Dard, O., Monier, F., and Mattina, C. (2018). Dénoncer la corruption: Chevaliers blancs, pamphlétaires et promoteurs de la transparence à l'époque contemporaine. Paris: Demopolis.

Gehl, K., and Roth, K. (2013). “The everyday culture of informality in post-socialist Bulgarian politics” in Informality in Eastern Europe. Structures, political cultures and social practices, Suisse. eds. C. Giordano and N. Hayoz (Lausanne: Peter Lang).

Gubernat, R., and Rammelt, H. P. (2021). “Vrem o ţară ca afară!”: how contention in Romania redefines state-building through a pro-European discourse. East Europ. Polit. Soc. 35, 247–268. doi: 10.1177/0888325419897987

Hein, M. (2015). The fight against government corruption in Romania: irreversible results or Sisyphean challenge. Europe-Asia Studies 67, 747–776. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2015.1045834

Holstein, A. J., and Miller, G. (1990). Rethinking victimization: an interactional approach to victimology. Symb. Interact. 13, 103–122. doi: 10.1525/si.1990.13.1.103

Iancu, A., and Todorov, A. (2018). Réformes, démocratisation et anti-corruption en Roumanie et Bulgarie: dix ans d’adhésion à l’Union européenne. Bucuresti: Editura Universitatii din Bucuresti.

Karsenti, B., and Lemieux, C. (2017). Socialisme et sociologie. Paris: Éditions de l’École des hautes études en sciences sociales.

Kupka, P., and Naxera, V. (2023). Looking back on corruption: representations of corruption and anti-corruption in Czech party manifestos between 1990–2017. Soc. Stud. 20:33476. doi: 10.5817/Soc2023-33476

Lemieux, C. (2018b). Paradoxe de la modernisation. Le productivisme agricole et ses critiques (Bretagne, années 1990-2010). Politix 31, 115–144.

Mărgărit, D. (2019). “Protestele în era anticorupției. Un caz românesc” in Corupția ucide? ed. O. Zamfirache (Bucharest: Curtea veche Publishing), 11–23.

Marton, S., and Monier, F. (2017). “Le pain et le sel” in Moralité du pouvoir et corruption en France et en Roumanie, Xviiie-Xxe siècle, Pu Paris-Sorbonne. eds. S. Marton, F. Monier, and O. Dard.

Năstase, L (2005). Procurorii anticorupție reiau cercetarea lui Adrian Năstase în dosarul ‘Zambaccian’, Adevărul, p. 5.

Philip, M. (2015). “The definition of political coruption” in Routledge handbook of political corruption. ed. P. M. Heywood (New York: Routledge), 17–29.

Ponta, V. (2022). Facebook post. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/victor.ponta/posts/570359184435653 (Accessed August 19, 2023)

Rothstein, B., and Uslaner, E. M. (2005). All for all: equality, corruption, and social trust. World Polit. 58, 41–72. doi: 10.1353/wp.2006.0022

Roux, V. (2022). Incendie d'une discothèque à Bucarest en 2015: du désastre au scandale politique. France 24. Available at: https://www.france24.com/fr/émissions/billet-retour/20201218-incendie-d-une-discothèque-à-bucarest-en-2015-du-désastre-au-scandale-politique (Accessed June 18, 2023)

Rubi Casals, M. G. (2014). La représentation de la corruption. L’Espagne dans la construction du libéralisme politique (1840–1868). In: O. Dard, J. I. Engels, and A. Fahrmeir Scandales et corruption à l’époque contemporaine, Paris: Armand Colin, coll. Recherches/ Les coulisses du politique dans l’Europe contemporaine, t. 3.

Schüler, S. (2013). Abuse of Office, Informal Networks, Moral Accountability – Political Corruption in Bulgaria, In: C. Giordano and N. Hayoz (eds), Informality in Eastern Europe. Structures, political cultures and social practices. Suisse: Peter Lang.

Stănilă, I. (2019). Povestea celui mai mare mafiot al Epocii de Aur. Cum a ajuns un falsificator de băuturi alcoolice să fie executat în 1981. Adevărul. Available at: https://adev.ro/pl75l8

Tismăneanu, V. (2007). Raportul final al Comisiei Prezidenţiale pentru Analiza Dictaturii Comuniste din România. Bucureşti: Humanitas.

Todorov, A Introduction, In: A. Iancu and A. Todorov (eds.) (2018). Réformes, démocratisation etanticorruption en Roumanie et Bulgarie: dix ans d’adhésion à l’Union européenne. Bucuresti, Editura Universității din Bucuresti, p.15.

Văduva, S (2016). From Corruption to Modernity. Germany: SpringerBriefs in Economics, Springer, edition 1.

Appendix

Table A1. List of documents consulted at CNSAS (National Council for the Study of Securitate Archives).

Keywords: corruption scandals, anti-corruption, Romania, post-communist societies, politicization, morphological explanation

Citation: Oprea A (2024) Behind anti-corruption, the transformations of society—investigation into the politicization of “illegal personal enrichment” in Romania. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1393060. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1393060

Edited by:

Kostas Gemenis, Cyprus University of Technology, CyprusReviewed by:

Marc Jacquinet, Universidade Aberta, PortugalRaluca Popp, University of Kent, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Oprea. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alexandra Oprea, b3ByZWEuYWxleGFuZHJhQGZzcHViLnVuaWJ1Yy5ybw==

Alexandra Oprea

Alexandra Oprea