- ERCOMER, Department of Interdisciplinary Social Science, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

Political campaign slogans, such as “Make America Great Again” or “The Netherlands Ours Again,” indicate that right-wing populists in Western countries use nostalgia to depict the national past as glorious. At the same time, populist radical-right parties (PRRP) portray this glorious past as being in stark contrast with the gloomy present of their country, which is portrayed as being in a state of decline. This suggests that PRRP in Western societies draw on both societal discontent (i.e., the belief that society is in decline and poorly functioning) and national nostalgia (i.e., a longing for the good old days of the country) to mobilize their voters. Although there is a burgeoning literature on reasons for PRRP electoral support, fewer studies have focused on its emotional or affective underpinnings. While scholars have proposed that both societal discontent and national nostalgia are an integral piece of a new master-frame employed by PRRP in Western countries to increase their electoral appeal, these elements have hardly been empirically studied in reference to voters. Relying on an integration of research in political science and social psychology, we hypothesized that both societal discontent and national nostalgia go together with a greater sympathy, and likelihood of voting, for PRRP. In addition, we predicted that national nostalgia is an explanatory mechanism that links societal discontent to more support for PRRP. These hypotheses were tested in the context of the Netherlands, among a representative sample of native Dutch voters, using the Dutch Parliamentary Elections Study of 2021. Results demonstrated that while both societal discontent and national nostalgia were relevant predictors of PRRP support, there was no strong evidence for national nostalgia as an explanatory mechanism of the link between societal discontent and PRRP support.

1 Introduction

For a few decades now, support for populist radical-right parties (PRRP) is on the rise in Western Europe. Long-standing PRRP, such as the Le Pen’s National Rally and predecessor Front National, The Austrian Freedom party and Swiss People’s Party see that their party-family member in other countries have become successful as well. Younger PRRP in Western Europe, such as The Sweden democrats (SD), the Brothers of Italy (Fdl) and the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV) have recently also become influential players in politics. All these parties employ an exclusionary version of populism based on their nativist ideology (Mudde, 2007) that divides society into two antagonistic groups: the pure people with a native ethnic background versus the corrupt elite and dangerous others (those with a non-native background). Their nativist agenda is mainly directed toward returning to an ethnically and culturally homogeneous nation (Bar-On, 2018) and/or toward opposing further diversification and immigration. In Western societies that have witnessed changing composition due to immigration, PRRP often link newcomers to a range of societal problems and criticize other (mainstream) parties for their failure to control immigration and to protect national culture. As a result, their party programs mostly focus on protecting the nation from perceived (further) threats from immigration and the European Union (Lubbers and Coenders, 2017). Although PRRP are democratically elected, they oppose fundamental elements of liberal democracy, such as the idea of pluralism within the nation state and the protection of minority rights (Rydgren, 2007). Their increasing power hence forms an important political challenge to the liberal democracy of European nations. Important research questions for scientists therefore center on the factors that can explain the increasing demand for these parties from the perspective of voters (Lubbers et al., 2002; Van der Brug and Fennema, 2007; Golder, 2016).

There is a long tradition and burgeoning scientific literature on the reasons for PRRP electoral support, particularly in political science (for reviews see: Golder, 2016; Rydgren, 2018). However, few studies have focused on the emotional/affective underpinnings that could explain the electoral appeal of PRRP (Rico et al., 2017; Salmela and Von Scheve, 2017). This is remarkable given the strong affective components that are present in their rhetoric. PRRP leaders in Western societies often talk about the glorious days of the nation when there was less globalization and ethno-cultural diversity and they put this past in stark contrast with the present and future of the country which are portrayed as being in decline due to imminent threats to the nation, such as immigration and European integration (Betz and Johnson, 2004; Smeekes et al., 2021). This suggests that Western PRRP draw on both societal discontent (i.e., the belief that society is in decline and poorly functioning) and national nostalgia (i.e., a longing for the good old days of the country) to mobilize their voters. This rhetoric resonates with the widespread feelings of societal discontent and nostalgia for the country’s past that are present among voters in present-day Western European societies (De Vries and Hoffmann, 2018, 2020; Ipsos, 2023). Trend surveys indicate that both societal discontent and national nostalgia have been relatively stable sentiments across Western Europe between 2015 and 2023, with around 70% of the population reporting that their country is heading in the wrong direction and between 50 and 60% indicating that they long for their country of the past (Eupinions, 2023; Ipsos, 2023).

Although there is some research that has investigated societal discontent and national nostalgia as predictors of PRRP support (Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018; Van der Bles et al., 2018; Smeekes et al., 2021), these affective elements have not been empirically studied in tandem. More specifically, there are some studies that have shown that societal discontent is more strongly present among PRRP supporters and increases the chance of voting for PRRP in Western Europe (Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018; Van der Bles et al., 2018), but these studies have not empirically assessed national nostalgia. On the other hand, there are some recent studies that have shown that national nostalgia is linked to stronger support for PRRP (Smeekes et al., 2021), but these studies have not considered societal discontent as a relevant predictive factor. In addition, recent studies that have empirically studied national nostalgia with respect to PRRP support have not yet examined to what extent this emotion distinguishes PRRP voters from voters of other political party families. In other words, previous research has not yet investigated whether PRRP supporters are the only nostalgia voters in the political spectrum.

In this paper, we contribute to the literature that seeks to better understand the affective appeal of PRRP by linking societal discontent and national nostalgia to PRRP ideology and support in the context of the Netherlands. Based on an integration of political science and social psychological research on societal discontent and PRRP support with social psychological research on national nostalgia and intergroup dynamics, we test the hypothesis that both societal discontent and national nostalgia go together with stronger feelings of sympathy for PRRP and a greater likelihood of voting for PRRP compared to other political parties. In addition, we propose a model in which national nostalgia forms an explanatory mechanism that links societal discontent to more support for PRRP. These hypotheses were tested among a representative sample of native Dutch voters, using the Dutch Parliamentary Elections Study of 2021.

Political scientists propose that the main features of PRRP’ ideology are populism, nativism and authoritarianism (Mudde, 2007; Golder, 2016; Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018). Populism is generally understood as a set of ideas that divides society into two antagonistic groups: the pure people versus the corrupt elite and as striving for the defense of popular sovereignty (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018). Populism can be found across the political spectrum and is not solely connected to PRRP. It is therefore considered to be a thin-centered ideology that is in most cases attached to thicker ideological elements, which in the case of PRRP concerns their nativist ideology. Nativism consists of a combination of ethnic nationalism and xenophobia, and can be defined as an ideology which holds that “states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (‘the nation’) and that nonnative elements (persons and ideas) are fundamentally threatening to the homogeneous nation-state” (Mudde, 2007, p. 19). The authoritarian aspect of PRRP’ ideology relates to the idea that these parties want society to be strictly ordered and they therefore advocate a strong law-and-order system that severely punishes deviant behavior (Mudde, 2007).

Scholars have proposed that PRRP rely on an exclusionary form of populism based on nativism that divides society into broader antagonistic groups, namely the pure people with a native ethnic background versus corrupt elites and dangerous others, who have formed a strategic alliance in depriving the pure native people of their national identity and prosperity (Albertazzi and McDonnell, 2007). In this rhetoric, the identification of dangerous “others” can be adjusted to the context. This othering has been more prominently directed to immigrants (or citizens with an immigrant background). Research shows that PRRP voters stand out in negative attitudes on immigration (Lubbers et al., 2002; Van der Brug and Fennema, 2007; Rooduijn et al., 2017). In the context of Western Europe and the Netherlands, Muslim immigrants and their offspring are targeted by PRRP in particular. Scholars have argued that in Western countries, Islamophobia has become the main form of xenophobia upon which PRRP build their exclusionary populism (Hafez, 2014; Kallis, 2018). PRRP in these contexts have redefined the “us” versus “them” opposition in terms of a clash between Western societies or civilizations on the one hand and Islam and Muslims on the other. In these discourses, the Muslim way of life is often portrayed as illiberal and therefore incompatible with the values of Western majority members. There is also empirical evidence that attitudes toward Muslims play a role in the vote for PRRP, next to attitudes to immigrants and Euro-skepticism (Lubbers and Coenders, 2017).

The extent to which PRRP voters are also characterized by affective and emotional sentiments is less well evidenced (Rico et al., 2017). Although not at the forefront of theorizing on PRRP voting, an increasing body of work argues that nostalgia for the good old days of the country forms a key element in PRRP ideology and has become part of a new master-frame that is used to attract voters (Betz and Johnson, 2004; Mols and Jetten, 2014; Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018; Smeekes et al., 2021; Lubbers and Smeekes, 2022). PRRP are often described as reactionary, because they seek to restore an idealized or even mythical version of the national past, in which the country was supposedly more simple, safe and secure because it was ‘just us’–that is, an ethnically and culturally homogeneous nation that was inhabited by natives only (Betz and Johnson, 2004; Rydgren, 2004; Duyvendak, 2011; Marzouki and McDonnell, 2016). Taggart (2004) describes this nostalgic portrayal of the nation as the heartland, which refers to a conception of an ideal society of the past, but one that is being romanticized and constructed and as such never really existed. However, PRRP across Europe also show differences in their nostalgic portrayal of the heartland. For example, some PRRP in Western Europe, argue for the protection of important liberal values and traditions (such as freedom of speech and gender equality) against the growing presence of immigrants with more traditional or conservative values (Spierings, 2020). In contrast, PRRP in Central-Eastern Europe often emphasize traditional family values and oppose further emancipation of women as important national values that should be protected. As such, while PRRP mostly share a nativist nostalgic portrayal of the heartland, there are some contextual differences when it comes to the values that they seek to maintain in the ethnically homogeneous nation.

A recent line of social psychological research proposes that that PRRP’ nostalgic portrayal of the past can strengthen the persuasiveness of their exclusionary populism based on nativism because it uses the positive portrayal of the past to more strongly demarcate exclusionary group-boundaries. That is, by portraying national past as glorious versus a present that is in decline PRRP mark group boundaries between ‘old-timers’ (i.e., the pure people with a native background that have always been here and are hence part of this positively remembered past) versus those who came later ‘the newcomers’, who are portrayed as threatening or ruining this glorious past and causing societal decline (Smeekes et al., 2021). Empirical studies within this line of work have shown that feelings of national nostalgia –i.e., a longing for the good old days of the country – tend to result in exclusionary understandings of national identity based on ancestry and descent (i.e., ethnic nationhood) and negative attitudes toward (Muslim) immigrants (Smeekes, 2015; Smeekes et al., 2015). Moreover, recent empirical work has demonstrated that the exclusionary responses that follow from national nostalgia can explain the link with PRRP support (Gest et al., 2018; Lammers and Baldwin, 2020; Schreurs, 2021; Versteegen, 2024). More specifically, it was found that national nostalgia among native Dutch majority members relates to more PPRP support because it translates into stronger support for their nativist ideology in the form of ethnic nationhood and anti-Muslim attitudes (Smeekes et al., 2021).

Importantly, in this social psychological literature, a distinction is made between personal and group-based nostalgia, where the former refers to feelings of nostalgia for things from the unique personal past and the latter is defined as a longing for objects, periods or events from one’s group past (Smeekes et al., 2015). Hence, where personal nostalgia is about a longing for ‘the way I was’, group-based nostalgia is about a longing for ‘the way we were’. Group-based nostalgia is hence an emotion that is based on collective memories that are shared with fellow group members and are passed on from generation to generation, for example via media channels and family members (Smeekes, 2019). This means that group-based nostalgia can also be experienced by individuals from younger generations who have not lived the collective past. Group-based nostalgia experiences can be shared by whole societies or groups (i.e., collective nostalgia), but this emotion can also be individually experienced when group membership becomes psychologically salient. National nostalgia can be seen as a specific form of group-based nostalgia that is based on national group membership. This means that, when their national identity is salient, individuals can feel nostalgic for things from their national group past. In this contribution we focus on individually experienced national nostalgia as an element that distinguishes Dutch PRRP voters from voters of other parties. This approach also extends earlier theorizing about the importance of national group membership and identification for radical right-voting in times of perceived crises (Lubbers, 2019), to an affective longing for an imagined national past that is shared with fellow group members.

In PRRP rhetoric in Western countries, this nostalgic portrayal of the past is inextricably linked with their discontent about the nation’s present and future. In contrast to the glorious past, PRRP in Western societies present an alarmist narrative about the present and future which are portrayed as being in decline and going in the wrong direction (Mols and Jetten, 2014). This sense of society or the people being in peril is a widespread sentiment among Western European voters, especially among those who support populist radical-right parties (De Vries and Hoffmann, 2018; Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018). Research indicates that people’s dissatisfaction with specific societal issues (e.g., the economy, immigration, crime) are highly related to one another and can be grouped together in an underlying factor that pertains to this general sense of societal discontent (Van der Bles et al., 2015, 2018). Hence, for many people, specific social problems are connected to one another and hereby contribute to their overarching negative view about the state of society as a whole. However, societal discontent itself can be understood as a rather unspecific feeling, because it is not about single societal issue, but about society as a whole (Gootjes et al., 2021). As such, societal discontent can be defined as “the feeling of belief that society, at large, is in a state of decline and is poorly functioning” (Gootjes et al., 2021, p.2).

The idea that voters are influenced by their evaluation of the way things are going in their society has a long tradition in the voting literature. For example, studies have addressed the role of retrospective and prospective voting, with vote choice being influenced by past (in the literature mostly economic) performance or expected future (economic) outlooks (Uslaner, 1989; Lubbers, 2001). In 1981, Kinder and Kiewiet already introduced the term “sociotropic voting” to refer to voting that is mainly driven by concerns about the state of the country’s economy, as opposed to voting that is mainly driven by concerns about one’s own personal economic circumstances (“egotropic voting”) (Kinder and Kiewiet, 1981). This line of work indicates that sociotropic concerns influence voting choices and in the economic voting literature these concerns are considered to be more influential in shaping voting behavior than egotropic concerns (Duch, 2009). The idea is that even though people are doing well financially on a personal level, they can still feel that the national economy is going in the wrong direction and this can affect their voting behavior. While personal and societal discontent reflect a broader concern about the way things are going on a personal and societal level (and not only the economy), a similar logic applies: people can feel that society is going in the wrong direction even though they are optimistic about their personal lives. This so called ‘optimism gap’ is a widespread phenomenon across Europe, where overall 58% feels pessimistic about their country’s future versus 42% who feels pessimistic about their personal future (De Vries and Hoffmann, 2018). Moreover, in his book titled “I’m fine, but we are not doing well,” Dutch sociologist Schnabel (2018) showed that during the last decades Dutch people have been generally very satisfied with their own lives, while at the same being dissatisfied with the state of society.

The idea that societal discontent is particularly strongly present among PRRP and their electorates in Western countries is in line with the new political cleavage structure of ‘opportunity versus risk’ that is present in Western Europe (Azmanova, 2011). This cleavage structure has also been described as ‘liberal versus authoritarian’ (Kitschelt, 1995), ‘cosmopolitism versus nationalism’ or broader, the GAL (Green-Alternative-Liberal) versus TAN (Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist) (Kriesi et al., 2008). These approaches all attest that that this new axis of political competition cuts across the traditional left–right ideological divide and centers on globalization-related opportunities versus risks. The idea is that, as a consequence of increasing globalization, society has become divided into groups that perceive either insecurities (risks) or increasing possibilities (opportunities) related to this development. Parties that find themselves at the risk axis emphasize both the economic risks (such as decreasing welfare security) as well as the cultural risks (loss of national culture and traditions) related to the increasingly globalized world and are therefore in favor of both cultural protectionism (lower immigration and less European integration) and economic protectionism (a closed economy with more welfare benefits). PRRP, but also some radical-left parties, can be found at the risk axis and their societal discontent rhetoric hence centers around these risks of globalization which are portrayed as being the cause of society being in decline (Betz and Johnson, 2004). More specifically, in the case of PRRP in Western countries, this rhetoric and the accompanying position of economic and cultural protectionism follows their nativist agenda and the idea of ‘own people first’. More than radical-left parties, PRRP in Western Europe want to protect both the cultural and economic position of native majority members against the risks of globalization which are mainly seen as stemming from increasing immigration and European integration (Rydgren, 2007).

A well-known explanation of PRRP voting that has been put forward in the literature and that is related to societal discontent is the idea of the protest vote (Van der Brug and Fennema, 2007). The protest vote approach suggests that some voters express their discontent with the political system by voting for populist parties that are antiestablishment and hence highly critical of the dominant elite (Lubbers et al., 2002; Rooduijn et al., 2016). According to this literature, populist parties are an attractive electoral option for politically discontented citizens because both of them voice strong criticism of the establishment (Akkerman et al., 2017). The idea that the elite is partly responsible for the downfall of society, is strongly present in the rhetoric of societal decline of populist parties in general (both left and right), including PRRP. As such, previous studies have often measured societal discontent in the form of a lack of political trust in the national government and parliament, showing that it predicts voting for both populist radical-left and -right parties (Akkerman et al., 2017; Rooduijn et al., 2017; Van der Bles et al., 2018; Giebler et al., 2021). The societal discontent of voters that we are interested in centers on a broader concern about the state of society and this could include, but is not restricted to, a lack of trust in or dissatisfaction with the political elite. In line with recent research (Gootjes et al., 2021), we therefore combine measures of political distrust with a general measure of societal pessimism (i.e., the belief that society is going in the wrong direction) in order to tap the underlying sentiment of societal discontent. Since PRRP in Western societies thrive on a combination of societal discontent and national nostalgia, these feelings should also be observable among the people who vote for them, and even more so than voters of other parties. We therefore formulated the following hypotheses:

H1a: When Dutch natives are more societally discontent they are more likely to vote for PRRP compared to other party families.

H1b: When Dutch natives are more nostalgic for the good old days of the country they are more likely to vote for PRRP compared to other party families.

Although most people in Western countries vote for other parties than PRRP, they can still feel sympathy for PRRP, which may result in voting for these parties in the future or supporting them in other ways (e.g., on social media, becoming a party member). We therefore consider PRRP sympathy as another indicator of PRRP support in this study and hypothesize that:

H2: Societal discontent and national nostalgia are related to stronger feelings of sympathy for PRRP among Dutch natives.

Scholars of group-based and collective nostalgia in sociology, anthropology and social psychology, agree that this emotion is particularly triggered in times of rapid social-change and uncertainty (e.g., Davis, 1979; Boym, 2001; Milligan, 2003; Smeekes, 2019). Already in 1979, sociologist Fred Davis argued that nostalgia is a response to ‘fears, discontents, anxieties, or uncertainties’ (1979, p. 34). Social psychological research has theorized and empirically demonstrated that one of the most important triggers of both personal and group-based nostalgia is a sense of identity discontinuity–the perception that there is an unwanted disruption between one’s past, present and future identity (Smeekes and Verkuyten, 2015; Smeekes et al., 2023). The reason is that longing for the past helps people to understand what the valued aspects of their identity are that they wish to hold on to (and hence protect) in the present. In this way, both personal and group-based nostalgia are understood as an emotional coping response to unwanted changes in the present. The concept of discontinuity is clearly reflected in the notion of societal discontent, as the latter centers on the idea of society changing in the wrong direction and hence forming a break (i.e., discontinuity) with the more positive past. It is therefore likely that national nostalgia forms a way to emotionally cope with the idea that society is in decline.

According to the intergroup emotions theory (IET; Mackie et al., 2009), the function of group-based emotions is to regulate attitudes and behaviors toward one’s own group (ingroup) and relevant other groups (outgroups). Similar to other psychological theories on emotion, IET proposes that the way in which group-based emotions affect group attitudes and behaviors depends on the particular function of the emotion. Psychologists have shown that both personal and group-based nostalgia have a restorative function – that is, in both cases, nostalgia helps to restore a sense of continuity of one’s identity (Sedikides et al., 2015; Wohl et al., 2023). Therefore, it is likely that the behaviors that follow from national nostalgia have the goal of protecting the continuity of the national ingroup. In line with this prediction, research has shown that national nostalgia among native Dutch majority members results in cultural protectionist attitudes and behavioral intentions, in the form of protecting traditional national culture and rejecting immigrants (Smeekes, 2015; Smeekes et al., 2023). Voting for PRRP and feeling sympathy for these parties can be seen as a behavioral and affective manifestation of the wish to protect the continuity of the national majority group, as cultural and economic protectionism are at the heart of Western European PRRP’ nativist party programs. Based on the theoretical reasoning above, we predict that:

H3: National nostalgia partly explains the positive association between societal discontent and both forms of PRRP support (voting and sympathy).

1.1 The case selection for the present study: the Netherlands

The populist radical-right has become increasingly successful in the Netherlands over the last two decades. The most successful PRRP in the Netherlands is the Party for Freedom (PVV), which is led by Geert Wilders and is represented in parliament since its foundation in 2006. In the national elections between 2010 and 2021, the PVV has received between 10 and 16% of the votes and this increased to 23.5% in the recent national elections in November 2023, making it the largest party in the country (Kiesraad, 2023). The ideology of the PVV can be described as exclusionary populism based on nativism with a strong focus on safety and law and order to protect the nation. In nativism of the PVV, Muslims and Islam and the ‘corrupt elite’ are considered the most important ‘dangerous others’ and the party has a strong call for ‘own people first’ when it comes to protecting the nation and redistributive social justice (Holsteyn, 2018). In their most recent election program of 2023 titled “Dutch people back at 1” (PVV, 2023), the PVV calls for an asylum stop and restrictive immigration policies, de-Islamization of the country, and leaving the European Union. In addition, the PVV claims to defend core progressive Dutch values, such as gender equality and homosexuality, against foreign (Islamic) influences. Next to cultural protectionist policies, the party also strongly calls for economic protectionism with a closed national economy with welfare chauvinistic (own people first) policies regarding housing, healthcare and taxes.

Next, to the PVV, there are two smaller PRRP in the Netherlands: Forum for Democracy (FvD) and JA21. These are relatively new parties that have, respectively, been established in 2016 and 2020. The FvD received 1.78% of the votes in 2017, which increased to 5.02% in 2021, but dropped to 2.23% in the 2023 elections. JA21 received 2.37% of the votes in the 2021 elections and this dropped to 0.68% in the 2023 elections. Similar to the PVV, these parties can be characterized as having an exclusionary populist ideology that is rooted in nativism and that is combined with a strong focus on law and order (Rooduijn, 2021; Lubbers, 2022). However, there are also some differences between these parties in how they implement their nativist ideology (Rooduijn, 2021; Lubbers, 2022). Compared to the PVV, FvD and JA21 are less strongly focused on Islam in their anti-immigrant stances. In addition, the party program of FvD is more strongly focused on the corrupt and malicious political elite than the other two PRRP. The differences between these parties are bigger when it comes to the economic political axis, where JA21 and FvD are more economically right-wing (less government intervention/free market) compared to PVV, which is more economically left-wing (more government intervention/state regulation). The Netherlands forms a relevant context for our study, as all PRRP make appeals to societal discontent and national nostalgia to justify their nativist standpoints. These parties present an alarmist narrative about the state of current Dutch society being in decline and the country heading in the wrong direction while at the same time portraying the past as a better time that needs to be restored. The PVV has campaigned with the slogan “Making the Netherlands ours again,” FvD with “Vote the Netherlands back” and JA21 with “The Netherlands back on track.” Qualitative research has demonstrated the nostalgic elements in Wilders’ political speeches (Mols and Jetten, 2014) and leader of the FvD, Thierry Baudet, has been labeled a “nostalgic populist” who is reactionary in his desire to restore the ethnically and culturally homogenous national past (Entizinger, 2019).

2 Materials and method

2.1 Data, participants, and procedure

We used data from a representative sample of Dutch adults from the Dutch Parliamentary Election Study 2021 (DPES; Jacobs et al., 2021; Sipma et al., 2021). The DPES is part of the National Election survey, which measures the opinion of Dutch voters on social and political issues since 1971. For this study we only used the post-election survey which was collected among the LISS panel (Longitudinal Internet Studies for the Social Sciences), administered by CentERdata (Tilburg University, the Netherlands). The LISS panel consists of 5,000 households, comprising approximately 7,500 individuals, who regularly complete web-based surveys. The panel is based on a true probability sample of households drawn from the population register of Statistics Netherlands, which includes households without Internet access (which are provided with computer and internet connection for the surveys).

A total of 2,797 LISS panel members were invited for the post-election survey and in total 2,313 respondents participated. Of this sample we selected participants with a Dutch background (i.e., two parents born in the country), resulting in a sample of N = 1,829. Furthermore, 31 participants had missing values on national nostalgia, societal discontent and both of the dependent variables and these were hence excluded from the data. This resulted in a final analytical sample of N = 1,798.

This sample consisted of 44.5% males and 55.5% females. The ages ranged between 18 and 103 with a mean age of 55.47 (SD = 17.42). In terms of educational level, 5.2% completed primary school, 20.6% completed intermediate secondary education, 10.1% completed higher secondary education, 24.5% completed intermediate vocational education, 28.6% completed higher vocational education and 11% completed university.

Informed consent was provided at the beginning of the survey and participation was anonymous and voluntary. Participants could skip questions they preferred not to answer and they could withdraw from the survey at any time.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 PRRP support

We used two measures to assess PRRP support (the dependent variables). The first measure, PRRP vote, is based on the party a respondent indicated having voted for in the last parliamentary elections in 2021. We compared PRRP voters to different relevant groups of voters, namely those of the radical left (RL), mainstream left (ML; social democratic parties) and mainstream right (MR; liberal, conservative and Christian democratic parties) and non-voters. An overview of the parties and how we grouped them into the party families can be found in Supplementary Table 1A. Second, we created a measure of PRRP sympathy, which was based on sympathy scores provided for each PRRP. Respondents were asked ‘How sympathetic do you find the following political parties?’ They could subsequently provide a response for each political party in parliament on a scale ranging from 0 (very unsympathetic) to 10 (very sympathetic). We averaged the scores of the three Dutch PRRPs (PVV, FvD and JA21) into a mean scale for of PRRP sympathy (α = 0.81). This scale contained 13.3% (N = 240) missing values.

2.2.2 Societal discontent

Following previous work by Gootjes et al. (2021), we assessed societal discontent by combining questions on political distrust with a general question about societal pessimism. For political distrust, we selected “trust in the government” and “trust in the national parliament” from the “trust in institutions” questions, where participants were asked how trustworthy they found a different institutions on a scale ranging from 1 (very much) to 4 (not at all). Societal pessimism was measured with one item based on previous research by Steenvoorden (2015). On a scale ranging from 1 (fully agree) to 5 (fully disagree), participants were asked to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “For most people in the Netherlands, life is getting worse rather than better.” The last item was recoded so a higher score reflected more societal discontent. We averaged the scores of the three items into a mean scale (α = 0.74). This scale contained 8.8% (N = 159) missing values.

2.2.3 National nostalgia

National nostalgia was assessed with two items derived from previous research by Smeekes et al. (2015). Participants indicated the extent to which they experienced the following when thinking about their country: “nostalgic about the sort of place the Netherlands was before” and “nostalgic about the good old days of the Netherlands.” Response labels ranged from (1) never to (5) very often. The items were combined into a scale (rSpearman-Brown = 0.86). This scale contained 12.8% (N = 231) missing values.

2.2.4 Control variables

We included gender (1 = female, 0 = male, and coded ‘other’ as missing), age, education, and anti-immigrant attitudes as control variables. The first three are socio-demographic variables that are well-known correlates of PRRP voting (e.g., Lubbers and Coenders, 2017; Rooduijn et al., 2017). Education was measured by asking participants to indicate their highest level of completed education, ranging from (1) primary education, to (6) university. In addition, there is a large body of work that has demonstrated the importance of anti-immigrant attitudes for PRRP support (e.g., Lubbers and Coenders, 2017). Anti-immigrant attitudes were assessed by asking participants to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the following items: ‘Immigrants are generally good for the Dutch economy’, ‘The Dutch culture is threatened by immigrants’ and ‘Immigrants increase crime rates in the Netherlands’. Response options ranged from 1 (fully agree) to 5 (fully disagree), and the last two items were recoded to that a higher score reflected stronger anti-immigrant attitudes. Items were combined into a mean scale (α = 0.78).

2.3 Analyses

Descriptive results and analyses were performed in SPSS 28.0. To test hypotheses 1a and 1b, we conducted a series of multinomial logistic regression analyses in Mplus 8.0 to investigate whether societal discontent and national nostalgia distinguish PRRP voters from MR, ML, RL and non-voters when taking into account socio-demographic factors (i.e., age, gender and education) and anti-immigrant attitudes (as a potential confounder). To test hypothesis 2, we performed another series of linear regressions to test whether societal discontent and national nostalgia relate to stronger sympathy for PRRP when taking into account socio-demographic factors and anti-immigrant attitudes.

Subsequently, we conducted two separate regression-based mediation analyses in Mplus 8.0 to test the hypothesis (H3) that societal discontent is related to a stronger likelihood of voting PRRP vs. other political parties (Model 1) and greater PRRP sympathy (Model 2), via stronger feelings of national nostalgia, controlling for gender, age, and education. Given the explanatory role of anti-immigrant attitudes in linking national nostalgia to PRRP support that has been observed in previous studies (e.g., Smeekes et al., 2023), we additionally estimated two mediation models in which we looked at whether societal discontent and national nostalgia are linked to PRRP voting and PRRP sympathy via anti-immigrant attitudes.

We estimated these path models with observed (manifest) constructs. Missing values were estimated through Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) which allows for unbiased estimates when data are missing at random (Wang and Wang, 2019).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive results

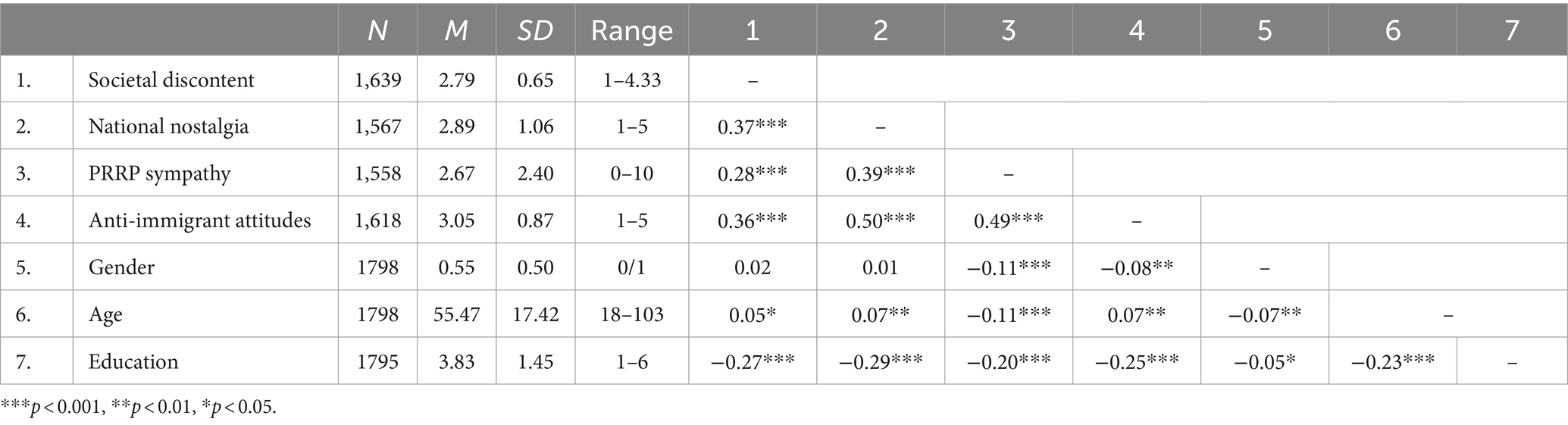

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations between societal discontent, national nostalgia and PRRP sympathy. Correlations between the key variables were significant and in the expected positive direction. Participants displayed on average moderate levels of societal discontent and this was significantly above the midpoint (median = 2.67) of the scale, t (1638) = 7.42, p < 0.001. On the other hand, participants displayed, on average, somewhat low levels of national nostalgia, as a t-test against the scale midpoint indicated, t (1566) = −4.16, p < 0.001. In addition, 12.6% of all the participants who voted in the 2021 national elections voted for a PRRP.

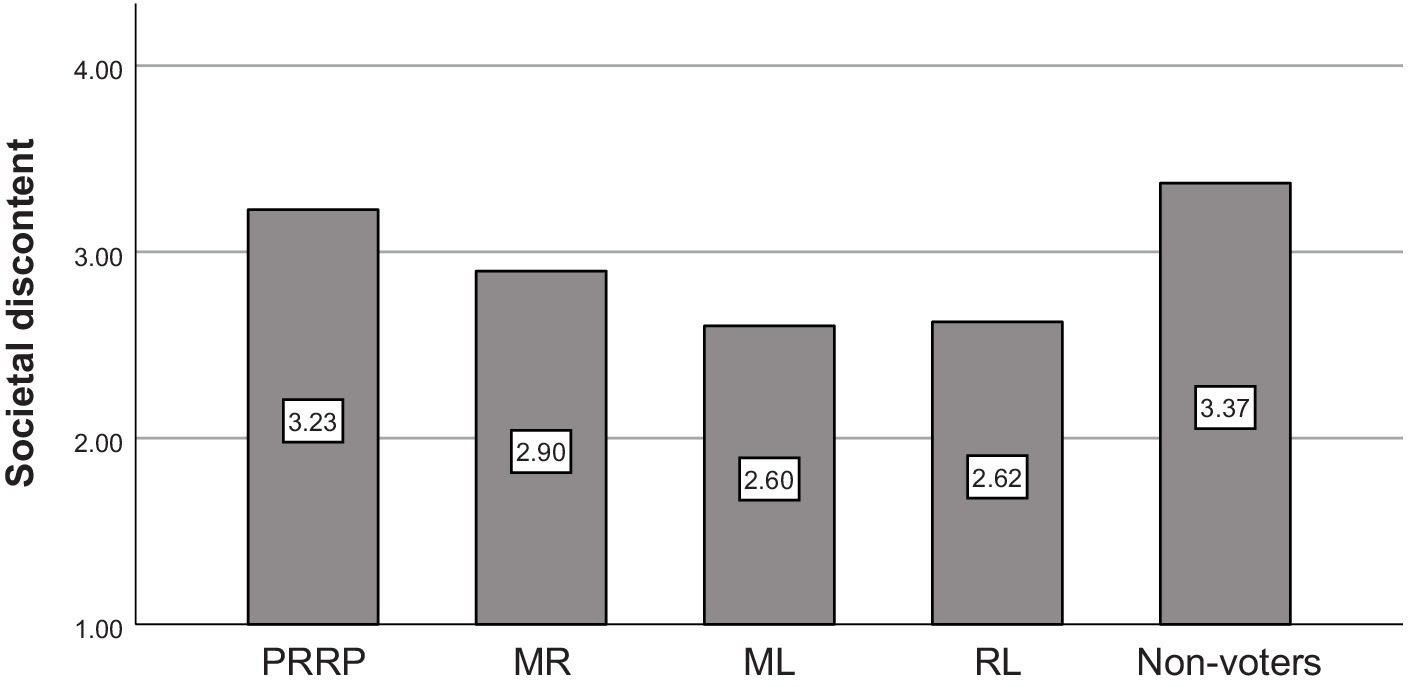

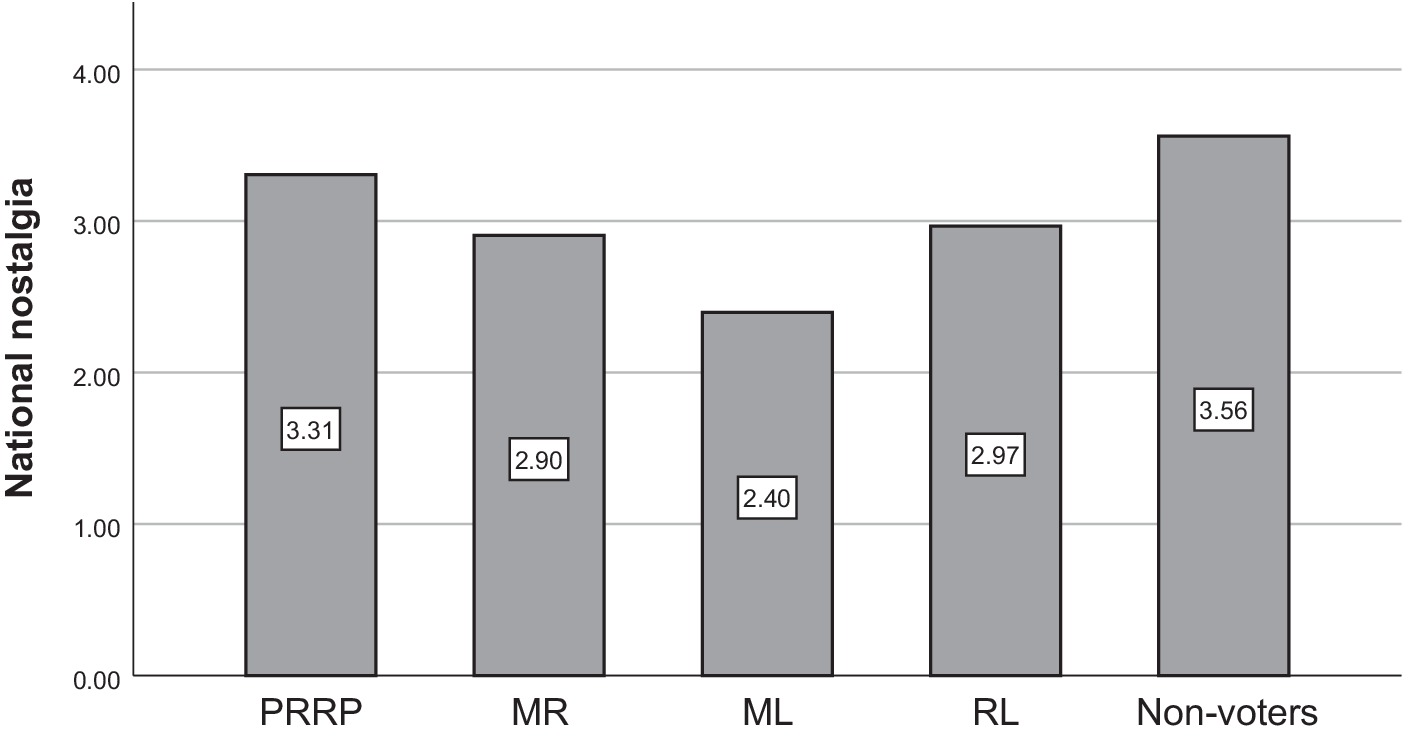

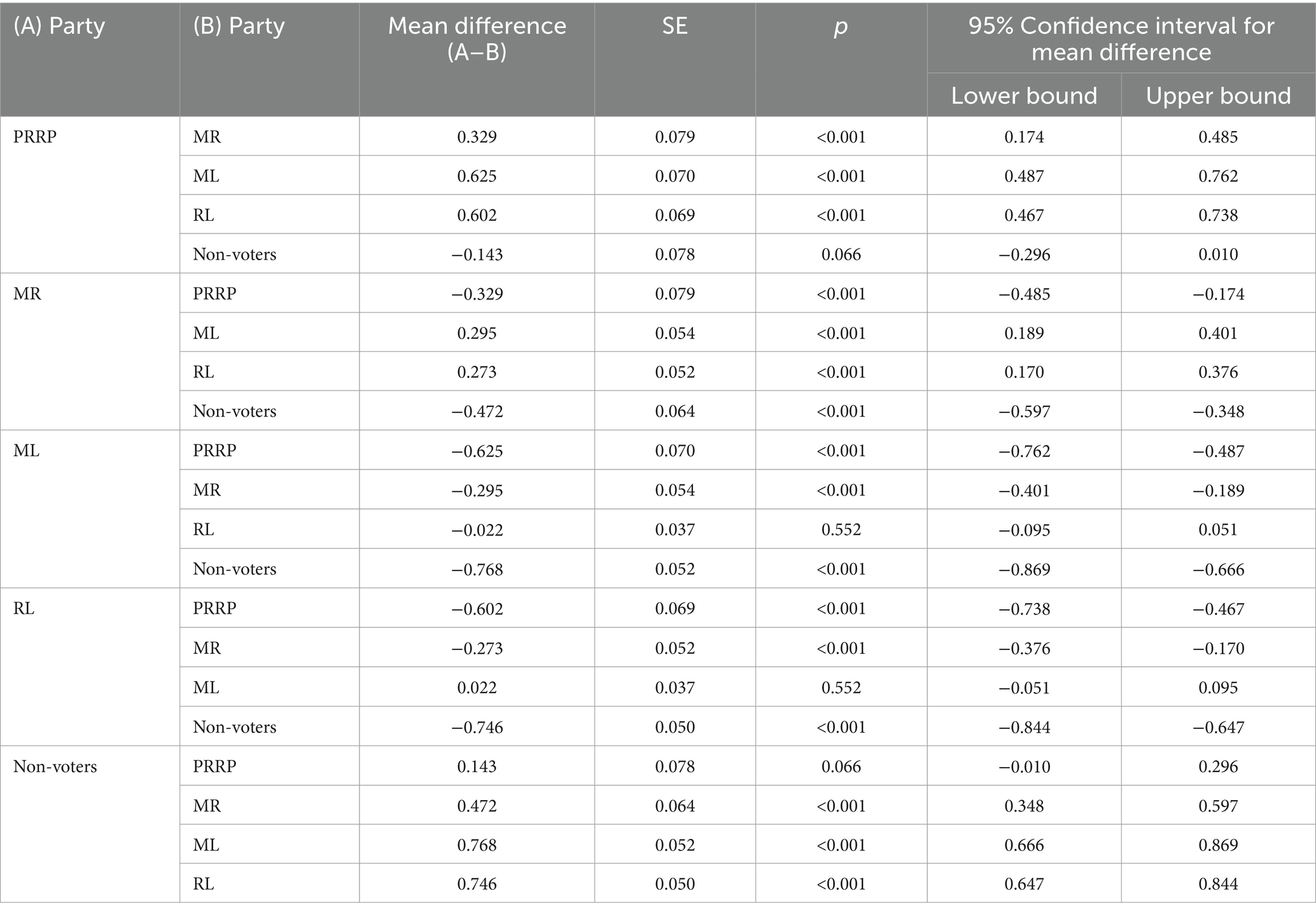

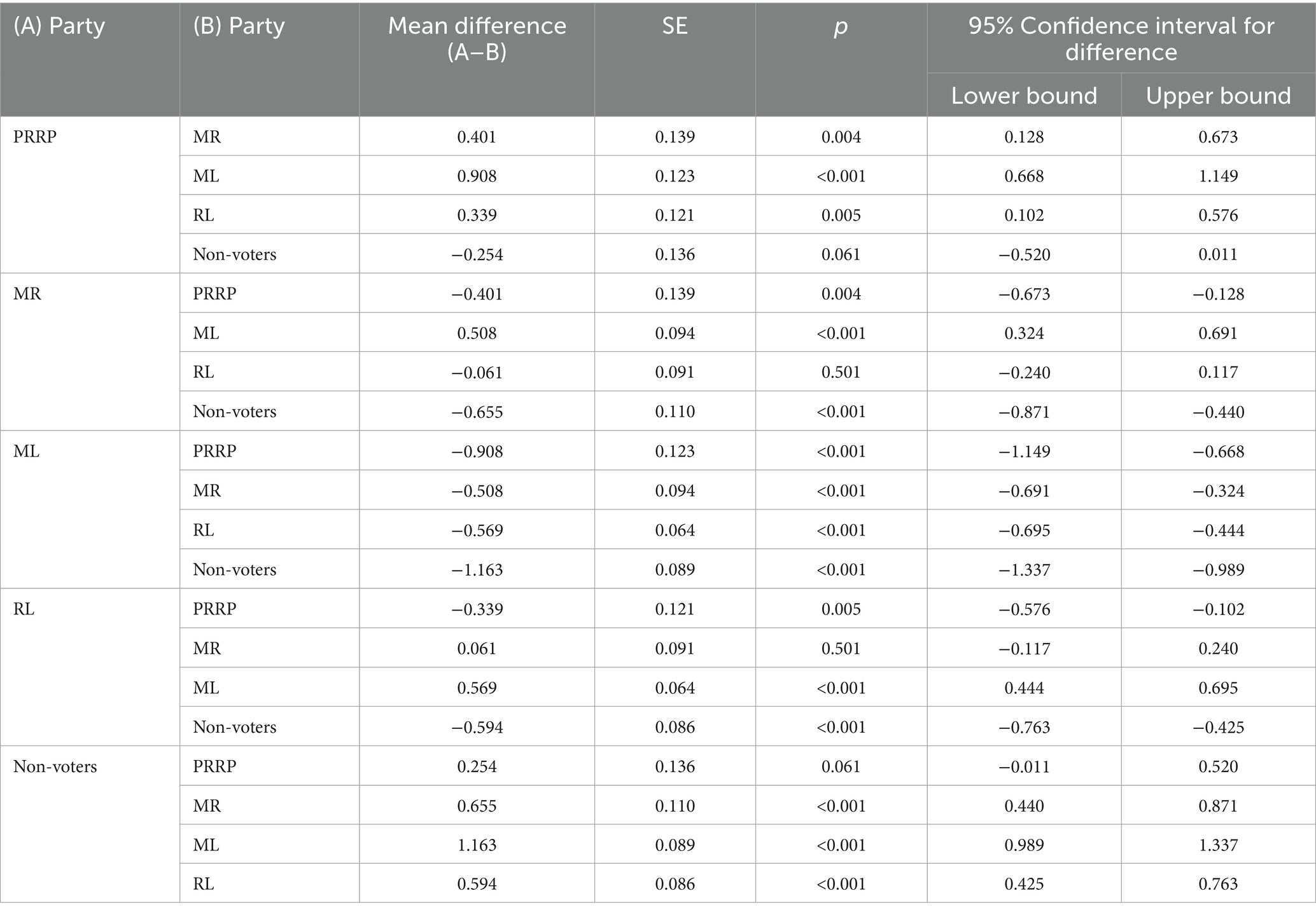

In addition, Figures 1, 2 display the mean levels of societal discontent and national nostalgia across the political party categories. We also performed ANOVA’s with pairwise comparisons to compare the mean differences in societal discontent and national nostalgia across the political party categories. The results are displayed in Tables 2, 3. All mean differences are significant, except for the following: the difference between PRRP voters and non-voters in societal discontent and national nostalgia, the difference between ML and RL voters in societal discontent, and the difference between RL and MR in national nostalgia. Taken together, this means that PRRP voters and non-voters stand out as being the most societally discontent and nostalgic for the country of the past.

3.2 Main results

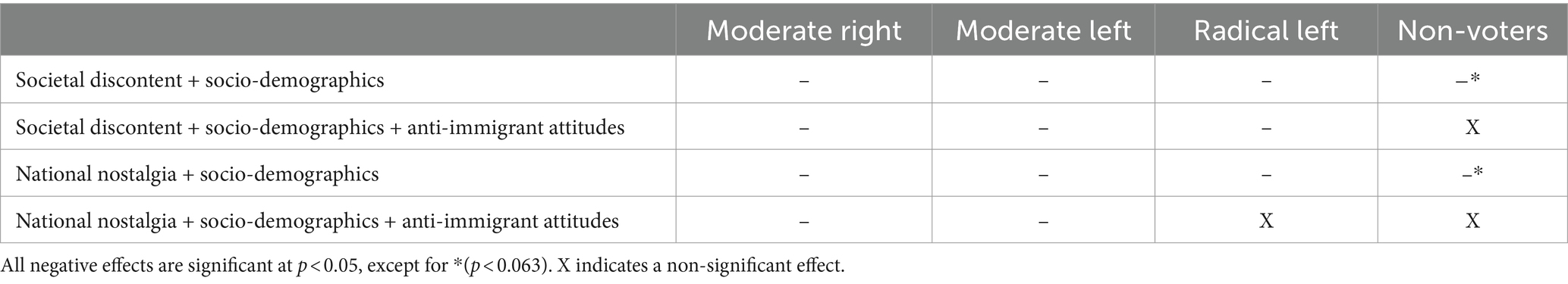

We subsequently tested whether these observations hold in multivariate models, in which we contrasted PRRP voters with voters of the other party families, and non-voters, when looking at feelings of societal discontent and national nostalgia. Table 4 displays the direction and significance of the societal discontent variable and the national nostalgia variable, which were estimated separately in several multinomial logistic regression models, in which we first added socio-demographics as a control variables (i.e., age, gender and education) and subsequently anti-immigrant attitudes. In these models PRRP is the reference category (results of these multivariate models can be found in Supplementary Tables A2–A5).

As can be seen in Table 4, when controlling for socio-demographics only, PRRP voters stood out as the most societally discontent and nostalgic compared to other voters and non-voters. When also controlling for anti-immigrant attitudes, societal discontent still significantly distinguished PRRP from voters of other party families, but not from non-voters. This means that H1a is supported by these results: societal discontent was related to a greater likelihood of PRRP voting compared to other party families (but not compared to non-voters). For national nostalgia, when also controlling for anti-immigrant attitudes, it still significantly distinguished PRRP voters from MR and ML voters, but not from RL and non-voters. This means that H1b is partly supported by these results: national nostalgia was related to a greater likelihood of voting for PRRP compared to MR and ML voters, but not compared to RL and non-voters.

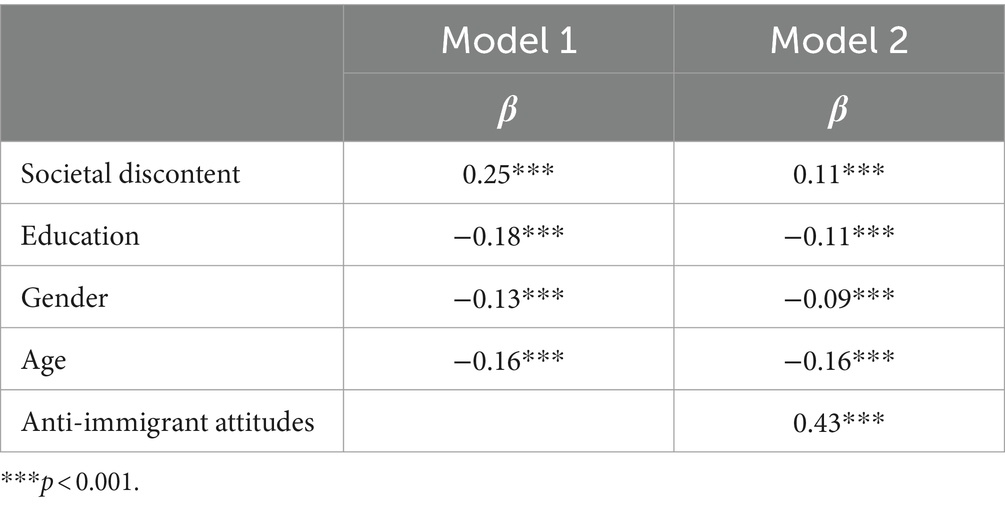

We subsequently examined the importance of societal discontent and national nostalgia in predicting feelings of sympathy for PRRP. Tables 5, 6 indicate their standardized effects in a model controlling for socio-demographics (Model 1) and in a model in which anti-immigrant attitudes was added on top of socio-demographics as a control (Model 2). As can be seen in Table 5, the effect of societal discontent on PRRP sympathy was positive and significant in both models, but became substantially smaller in Model 2 when anti-immigrant attitudes was added as a control. Table 6 reveals the positive and significant effects of national nostalgia on PRRP sympathy in both models and indicates that the effect was also substantially reduced when anti-immigrant attitudes was added as a control variable in Model 2. These results support H2: Societal discontent and national nostalgia are related to stronger feelings of sympathy for PRRP among Dutch natives. As the effects of both societal discontent and national nostalgia were substantially reduced when controlling for anti-immigrant attitudes, these results furthermore suggest that anti-immigrant attitudes may be an additional explanatory (mediating) factor in linking societal discontent and national nostalgia to PRRP support (see last part of the results section).

3.2.1 National nostalgia as an explanatory mechanism

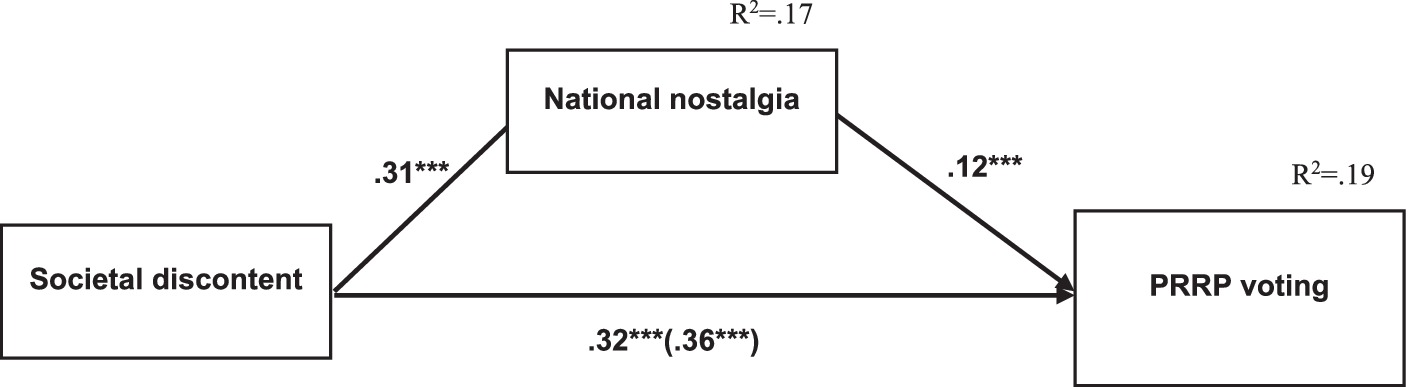

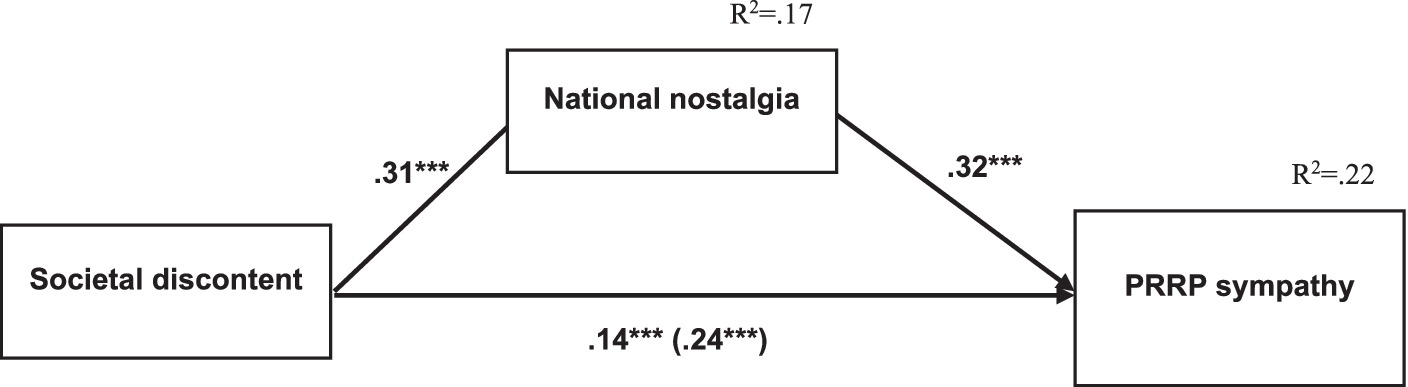

We now turn to a closer investigation of the role played by national nostalgia in linking societal discontent to PRRP support. For this mediation analysis, we looked at PRRP support in terms of voting for a PRRP versus voting for other parties (coded 1 and 0 respectively) and in terms of PRRP sympathy. We first estimated two mediation models for these two dependent variables (PRRP support in terms of voting and sympathy) separately in Mplus. We looked at whether societal discontent is linked to PRRP voting (Model 1) and PRRP sympathy (Model 2) via national nostalgia. In both models, we controlled for the socio-demographic variables. The results are displayed in Figures 3, 4. We estimated the significance of indirect effects using bootstrapping procedures (1,000 samples, 95% confidence intervals).

Figure 3. Logistic regression mediation Model 1 (N = 1,616): Relation between societal discontent and PRRP voting via national nostalgia (controlling for age, gender, and education). Path-coefficients are standardized estimates. The coefficient in parenthesis is the total effect. PRRP = Populist Radical Right Parties. ***p < .001.

Figure 4. Linear regression mediation Model 2 (N = 1,620): Relation between societal discontent and PRRP sympathy via national nostalgia (controlling for age, gender, and education). Path-coefficients are standardized estimates. The coefficient in parenthesis is the total effect. PRRP = Populist Radical Right Parties. ***p < .001,*p < .05.

As can be seen in Figures 3, 4, societal discontent was positively related to national nostalgia. National nostalgia was, in turn, positively related to both forms of PRRP support. In Model 1, there was a small significant positive indirect effect of societal discontent on PRRP voting via national nostalgia (β = 0.037, LLCI = 0.020, ULCI = 0.058) and the direct effect of societal discontent on PRRP voting remained substantial and significant. In Model 2, there was a small significant positive indirect effect of societal discontent on PRRP sympathy via national nostalgia (β = 0.099, LLCI = 0.079, ULCI = 0.122) and the direct effect of societal discontent remained significant. This means that the effect of societal discontent on PRRP voting and sympathy was only for a small part explained by feelings of national nostalgia. Taken together, while these findings are in line with our hypotheses (H3 and H4) that national nostalgia can partly explain the positive relationship between societal discontent and PRRP voting and PRRP sympathy, the indirect effect sizes are small. This indicates that national nostalgia does not play a strong explanatory role in linking societal discontent to PRRP support, but that both societal discontent and national nostalgia play a role next to one another in explaining PRRP support.

As for the socio-demographic control variables, we found that gender was unrelated to national nostalgia in both models (ps > 0.654), and was negatively associated with both PRRP voting (β = −0.11, p < 0.001) and PRRP sympathy (β = −0.13, p < 0.001). Women (compared to men) displayed weaker support for PRRP. In both models, age was unrelated to national nostalgia (ps > 0.772), and was negatively associated with both PRRP voting (β = −0.12, p < 0.001) and PRRP sympathy (β = −0.16, p < 0.001). Older (compared to younger) participants were less likely to support PRRP. In both models, education was negatively associated with national nostalgia (Model 1: β = −0.20, p < 0.001; Model 2: β = −0.20, p < 0.001). Moreover, education was negatively associated with both PRRP voting (Model 1: β = −0.11, p < 0.001) and PRRP sympathy (Model 2: β = −0.12, p < 0.001). Higher (compared to lower) educated participants were less likely to feel national nostalgia and to support PRRP.

3.2.2 Additional analyses: anti-immigrant attitudes as a mediator

We subsequently performed additional analyses with anti-immigrant attitudes as a mediator, in which we looked at whether societal discontent and national nostalgia are linked to PRRP voting and PRRP sympathy via anti-immigrant attitudes. We estimated separate mediation models for national nostalgia and societal discontent as predictors well as for the two forms of PRRP support (i.e., PRRP versus voting for other parties (coded 1 and 0 respectively) and PRRP sympathy). In all four models, we controlled for the socio-demographic variables of gender, age and education. We estimated the indirect effects using bootstrapping procedures (1,000 samples, 95% confidence intervals). Results are displayed in Supplementary Figures A1–A4.

These results showed that both societal discontent and national nostalgia were strongly and positively related to anti-immigrant attitudes. We furthermore found significant positive indirect effects of societal discontent via anti-immigrant attitudes on PRRP voting (β = 0.077, LLCI = 0.030, ULCI = 0.061) and on PRRP sympathy (β = 0.135, LLCI = 0.111, ULCI = 0.164). We also found significant positive indirect effects of national nostalgia via anti-immigrant attitudes on PRRP voting (β = 0.136, LLCI = 0.103, ULCI = 0.171) and on PRRP sympathy (β = 0.175, LLCI = 0.146, ULCI = 0.205). In all models, the direct effects of societal discontent and national nostalgia on PRRP support remained significant, indicating that anti-immigrant attitudes partially explained the positive relationship between societal discontent and national nostalgia on the one hand and PRRP support on the other.

4 General discussion

Political campaign slogans, such as “Make America Great Again” or “The Netherlands Ours Again,” indicate that PRRP in Western societies make appeals to nostalgia by depicting the national past as glorious. At the same time, these parties portray this glorious past as being in stark contrast with the gloomy present of their country, which is portrayed as being in a state of decline. This suggests that PRRP in Western countries draw on affective sentiments of societal discontent (i.e., the belief that society is in decline and poorly functioning) and national nostalgia (i.e., a longing for the good old days of the country) to mobilize their voters. In this contribution, we sought to better understand these affective appeals of PRRP in a Western context, by studying the role of feelings of societal discontent and national nostalgia (and their interplay) among voters in relation to PRRP support. We examined these relationships in the context of the Netherlands, among native Dutch voters, using the Dutch Parliamentary Elections Study of 2021.

Descriptive results first demonstrated that native Dutch PRRP voters were indeed the most societally discontent and nostalgic for their country’s past compared to voters of other party families. The highest levels of societal discontent and national nostalgia were found among PRRP voters and non-voters (and to a lesser extent among MR voters), while the least societally discontent and nostalgic were the ML voters. While RL voters were almost equally societally discontent as ML voters, they were more nationally nostalgic compared to ML voters to a comparable level of that of MR voters. This indicates that, unlike the findings of previous studies in the Western European context (e.g., Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018), in our study in the Dutch context, societal discontent was not equally present among radical right and left voters, but particularly characterized PRRP and non-voters. National nostalgia was also particularly present among PRRP and non-voters, but the finding that RL voters were equally nationally nostalgic as MR voters indicates that national nostalgia is not an inherently right-wing emotion, as previous work has suggested (Betz and Johnson, 2004; Schreurs, 2021).

Based on an integration of political science and social psychological research on societal discontent and PRRP support (Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018; Van der Bles et al., 2018; Gootjes et al., 2021) with social psychological research on national nostalgia and intergroup dynamics (Smeekes et al., 2015, 2023), we predicted that both societal discontent and national nostalgia are affective sentiments that are related to more support for Dutch PRRP in the form of: (a) a higher likelihood of voting for PRRP compared to other party families, and (b) stronger feelings of sympathy for PRRP. The results showed that, when controlling for socio-demographic factors (i.e., age, gender and education), both societal discontent and national nostalgia significantly reduced the likelihood of voting for any party–RL, ML, or MR–as well as non-voters, compared to voting for PRRP. In a full model, including anti-immigration attitudes on top of socio-demographic voter characteristics, societal discontent still significantly reduced the likelihood of voting for any party compared to PRRP, but not for non-voters. For national nostalgia, the full model including anti-immigration attitudes, significantly reduced the likelihood of voting for ML and MR parties compared to PRRP, but not for RL and non-voters. This finding is interesting, as it goes against the commonplace assumption that PRRP are the archetypical embodiment of nostalgia politics (Schreurs, 2021) and suggests that nostalgia may also have an affective appeal for radical left voters. This is in line with recent studies showing that left-wing voters in the Netherlands also experience nostalgia, but that, unlike the nostalgia of PRRP voters, which is more strongly directed toward ethno-cultural diversity and immigration, left-wing nostalgia more strongly focuses on increasing socio-economic inequality and the dismantling of the welfare state (Van der Velden et al., 2024). Concerning PRRP sympathy, we found that both societal discontent and national nostalgia were positively related to PRRP sympathy, when controlling for socio-demographics but also in a full model including anti-immigrant attitudes as a control. Taken together, these findings contribute to the broader social scientific literature on PRRP support from a demand side perspective, because they indicate that both societal discontent and national nostalgia can be considered as relevant affective explanations for PRRP support among voters on top of other well-known indicators that explain the demand side of PRRP success.

In addition, based on previous social psychological research on the triggers and consequences of national nostalgia (Smeekes et al., 2015, 2021), we predicted that national nostalgia would be an explanatory mechanism linking societal discontent to PRRP support. The reason is that this body of work has demonstrated that national nostalgia can be understood as an emotional coping mechanism that helps people to deal with unwanted changes and discontinuities in present-day society, which subsequently results in protectionist tendencies to restore the glorious days of the nation (Smeekes et al., 2023). In line with this literature, we found that societal discontent was positively related to national nostalgia, which, in turn, translated into more support for Dutch PRRP (both in terms of voting and sympathy). Although we found significant indirect effects of societal discontent on PRRP voting and sympathy via national nostalgia, the standardized indirect effects were rather small (especially for voting). In both cases, the direct effect of societal discontent on PRRP support remained strong and significant, indicating that national nostalgia only to small extent explained the relation between societal discontent and PRRP support. The reason is likely related to our earlier finding that national nostalgia is not a unique characteristic of PRRP voters, but is also present among other groups of Dutch voters (especially ML and RL), meaning that it can also result in a choice for other party families and not only in a PRRP vote. For the sympathy measure, we only looked at the Dutch PRRP, but given these findings it is also likely that national nostalgia relates to stronger sympathy for ML and RL parties. Taken together, these results suggests that while both societal discontent and national nostalgia form relevant affective explanations for PRRP support, national nostalgia is not a strong explanatory mechanism linking societal discontent to PRRP support in our 2021 sample of Dutch voters. Our results indicate that these affective mechanisms may operate simultaneously instead of sequentially in fostering PRRP support.

Furthermore, based on previous work that has demonstrated positive links between societal discontent and national nostalgia on the one hand and anti-immigrant attitudes on the other (e.g., Smeekes et al., 2015, 2021; Gootjes et al., 2021), and the broader literature on anti-immigrant attitudes as key predictor of PRRP support in Western countries (Lubbers and Coenders, 2017; Rooduijn et al., 2017), we examined the explanatory role of anti-immigration attitudes in linking societal discontent and national nostalgia to PRRP support in the Dutch context. Results showed that both societal discontent and national nostalgia were strongly related to anti-immigrant attitudes, and that anti-immigrant attitudes partially explained their positive relation with PRRP support. These results are in line with previous social psychological research showing that societal discontent and national nostalgia can feed into anti-immigrant attitudes (e.g., Smeekes et al., 2015, 2021; Gootjes et al., 2021), and additionally showed that one of the reasons why these two affective sentiments relate to PRRP support is because they also translate into stronger anti-immigrant attitudes. Yet, the fact that anti-immigrant attitudes partially mediated the effects of societal discontent and national nostalgia suggests that there are other explanatory mechanisms that link these affective elements to PRRP support. One relevant direction for future research would be to focus on relative group deprivation (i.e., the perception that one’s group is deprived or disadvantaged in comparison to other groups) as another possible explanatory factor linking both societal discontent and national nostalgia to PRRP support. In the rhetoric of PRRP, society’s present-day decline and loss of the glorious national past is often portrayed as the result of the malicious elites that has disadvantaged national majority group members over immigrant groups (Marchlewska et al., 2018). Empirical studies have demonstrated that relative group deprivation is associated with PRRP support and anti-immigrant attitudes (Anier et al., 2016; Marchlewska et al., 2018). Feeling that society is in decline and longing for the national past may be both a cause and consequence of the belief that the national majority group is disadvantaged over immigrant groups. Future studies could study the interplay between relative group deprivation, anti-immigrant attitudes and the affective sentiments of societal discontent and national nostalgia in relation to PRRP support.

Our work has several limitations that provide further directions for future studies. The cross-sectional design of our study does not warrant causal inferences. Although previous research has proposed societal discontent and national nostalgia as relevant predictive factors of anti-immigrant stances (Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018; Gootjes et al., 2021; Smeekes et al., 2021), it is possible that both these affective voter sentiments are not only a cause but also a consequence of their anti-immigrant stances. More specifically, when voters feel that immigrants pose a threat to the nation and its identity, this could strengthen their idea that society is decline and make them resort to nostalgia for a past that was more ethno-culturally homogenous, which could subsequently strengthen their PRRP support. Experimental and longitudinal studies could further investigate the causal mechanisms between affective sentiments and support for PRRP and their nativist ideology.

A second limitation concerns the single national context of our study, which makes it unclear to what extent the findings generalize to other contexts outside of the Netherlands. However, previous studies have demonstrated that societal discontent is linked to PRRP support across Western Europe (Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018) and scholars have argued that PRRP across Western Europe employ a comparable nostalgic discourse (Duyvendak, 2011; Mols and Jetten, 2014; Lubbers, 2019; Lubbers and Smeekes, 2022). In addition, cross-cultural research has demonstrated that national nostalgia is linked to anti-immigrant attitudes in several Western countries (Smeekes et al., 2018). As such, we propose that it is likely that both societal discontent and national nostalgia form affective explanations for PRRP support (via stronger anti-immigrant attitudes) across Western European countries. Nevertheless, we encourage future work to replicate the findings outside the Dutch and Western European context. More specifically, we encourage future studies to further explore these dynamics among voters in Central-Eastern European countries. Although PRRP in these contexts share the most important ideological components with their Western counterparts, their nostalgic nativism centers more strongly on traditional family and Christian values and anti-Roma sentiments (Cinpoeş and Norocel, 2020; Kondor and Littler, 2020). In addition, research has highlighted the importance of post-communist nostalgia (i.e., longing for the communist past of their country) in these contexts as a result of societal discontent with the present capitalist system (Prusik and Lewicka, 2016). Some PRRP in this region capitalize on post-communist nostalgia by appealing to those who feel dissatisfied with the transition to capitalism and democracy, but future studies could more closely investigate how societal discontent and national nostalgia (both in more generic and more content-specific forms) affect support for PRRP in Central-Eastern European countries.

A final limitation concerns our measurements of societal discontent and national nostalgia. We assessed these affective sentiments in a rather general way, without asking people about concrete aspects of society that they feel that are in decline or that they are nostalgic about. Yet, recent studies have demonstrated that people can experience societal discontent and national nostalgia in relation to specific societal issues (e.g., ethnic diversity, economic inequality) and that the contents of this societal discontent and national nostalgia diverge between Dutch right-wing and left-wing voters (Van der Velden et al., 2024). Follow-up research could examine in more detail how specific contents of societal discontent and national nostalgia affect support for PRRP and their nativist stances as well as support for other political parties and their ideology, in both Western and Central-Eastern European contexts.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that, among national majority members in the Dutch context, both societal discontent and national nostalgia form relevant affective explanations for PRRP support in the form of voting and PRRP sympathy, over and above well-known indicators of PRRP support (i.e., age, gender, education and anti-immigration attitudes). In addition, our study demonstrated that part of the positive effects of societal discontent and national nostalgia on PRRP support could be explained by stronger anti-immigrant attitudes. Our findings extend social psychological and political scientific research on affective explanations for PRRP success from a demand-side perspective.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://doi.org/10.17026/dans-xcy-ac9q.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Social & Behavioural Sciences (Utrecht University). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

AS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the focus area 'Migration and Societal Change' of Utrecht University as part of a Special Interest Group on "The rise of the radical right in Europe: An interdisciplinary approach". The publication costs of this article were covered by the focus area.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support provided by the focus area 'Migration and Societal Change' of Utrecht University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1390662/full#supplementary-material

References

Akkerman, A., Zaslove, A., and Spruyt, B. (2017). ‘We the people’or ‘we the peoples’? A comparison of support for the populist radical right and populist radical left in the Netherlands. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 377–403. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12275

Albertazzi, D., and McDonnell, D. (2007). Twenty-first century populism: The spectre of Western European democracy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Anier, N., Guimond, S., and Dambrun, M. (2016). Relative deprivation and gratification elicit prejudice: research on the V-curve hypothesis. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 11, 96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.06.012

Azmanova, A. (2011). After the left–right (dis) continuum: globalization and the remaking of Europe's ideological geography. Int. Polit. Sociol. 5, 384–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-5687.2011.00141.x

Bar-On, T. (2018). “The radical right and nationalism” in The Oxford handbook of the radical right. ed. J. Rydgren (New York: Oxford University Press), 17–41.

Betz, H., and Johnson, C. (2004). Against the current—stemming the tide: the nostalgic ideology of the contemporary radical populist right. J. Polit. Ideol. 9, 311–327. doi: 10.1080/1356931042000263546

Cinpoeş, R., and Norocel, O. C. (2020). “Nostalgic nationalism, welfare chauvinism, and migration anxieties in central and Eastern Europe” in Nostalgia and Hope: Intersections between politics of culture, welfare, and migration in Europe. eds. A. C. Norocel, A. Hellström, and M. B. Jørgensen (Cham: Springer Nature), 51–65.

De Vries, C.E., and Hoffmann, I. (2018). The power of the past: How nostalgia shapes European public opinion. Available at: https://eupinions.eu/de/text/the-power-of-the-past

De Vries, C.E., and Hoffmann, I. (2020). The optimism gap: Personal complacency versus societal pessimism in European public opinion. Available at: https://eupinions.eu/de/text/the-optimism-gap

Duch, R. M. (2009). “Comparative studies of the economy and the vote” in The Oxford handbook of comparative politics. eds. C. Boix and S. C. Stokes (New York: Oxford University Press), 1–49.

Duyvendak, J. (2011). The politics of home: Belonging and nostalgia in Western Europe and the United States. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Entizinger, J . (2019) Baudet: een nostalgische populist, geen migrantenhater [Baudet: a nostalgic populist, not a migrant hater], De Kanttekening. Available at: https://dekanttekening.nl/columns/baudet-een-nostalgische-populist-geen-migrantenhater. Accessed on February 23, 2024.

Eupinions. (2023). Eupinions trends/Direction of your country. Available at: https://eupinions.eu/de/trends. Accessed on February 22, 2024.

Gest, J., Reny, T., and Mayer, J. (2018). Roots of the radical right: nostalgic deprivation in the United States and Britain. Comp. Pol. Stud. 51, 1694–1719. doi: 10.1177/0010414017720705

Giebler, H., Hirsch, M., Schürmann, B., and Veit, S. (2021). Discontent with what? Linking self-centered and society-centered discontent to populist party support. Polit. Stud. 69, 900–920. doi: 10.1177/0032321720932115

Golder, M. (2016). Far right parties in Europe. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 19, 477–497. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042814-012441

Gootjes, F., Kuppens, T., Postmes, T., and Gordijn, E. (2021). Disentangling societal discontent and intergroup threat: explaining actions towards refugees and towards the state. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 34, 1–14. doi: 10.5334/irsp.509

Hafez, F. (2014). Shifting borders: islamophobia as common ground for building pan-European right-wing unity. Patterns Prejud. 48, 479–499. doi: 10.1080/0031322X.2014.965877

Holsteyn, J. J. M. (2018). “The radical right in Belgium and the Netherlands” in The Oxford handbook of the radical right. ed. J. Rydgren (New York: Oxford University Press), 478–505.

Ipsos. (2023). Global trends 2023: A new world disordered? Navigating a polycrisis. Available at: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/2023-Ipsos-Global-Trends-Report.pdf. Accessed on February 22, 2024.

Jacobs, K., Lubbers, M., Sipma, T., Spierings, N., and van der Meer, T. W. G. (2021). Dutch parliamentary election study 2021 (DPES/NKO 2021). DANS Data Station Soc. Sci. Human. doi: 10.17026/dans-xcy-ac9q

Kallis, A. (2018). Populism, sovereigntism, and the unlikely re-emergence of the territorial nation-state. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 11, 285–302. doi: 10.1007/s40647-018-0233-z

Kiesraad. (2023). Tweede Kamer 22 november 2023. Available at: https://www.verkiezingsuitslagen.nl/verkiezingen/detail/TK20231122 Accessed February 22, 2024.

Kinder, D. R., and Kiewiet, D. R. (1981). Sociotropic politics: the American case. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 11, 129–161. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400002544

Kitschelt, H. (1995). Formation of party cleavages in post-communist democracies: theoretical propositions. Party Polit. 1, 447–472. doi: 10.1177/1354068895001004002

Kondor, K., and Littler, M. (2020). “Invented nostalgia: the search for identity among the Hungarian far-right” in Nostalgia and Hope: Intersections between politics of culture, welfare, and migration in Europe. eds. A. C. Norocel, A. Hellström, and M. B. Jørgensen (London: Springer Nature), 119–134.

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Lammers, J., and Baldwin, M. (2020). Make America gracious again: collective nostalgia can increase and decrease support for right-wing populist rhetoric. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 943–954. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2673

Lubbers, M. (2001). Exclusionary electorates: Extreme right-wing voting in Western Europe [Doctoral dissertation, Radboud University]. Available at: https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/146820/146820.pdf?sequence=1

Lubbers, M. (2019). What kind of nationalism sets the radical right and its electorate apart from the rest? Pride in the nation’s history as part of nationalist nostalgia. Nations Natl. 25, 449–466. doi: 10.1111/nana.12517

Lubbers, M. (2022). “Competition on the radical right – explanations of radical right voting in the Netherlands in 2021” in Migration and ethnic relations: Current directions for theory and research. Liber Amicorum for Maykel Verkuyten. eds. A. Smeekes and J. Thijs (Utrecht: Utrecht University), 115–131.

Lubbers, M., and Coenders, M. (2017). Nationalistic attitudes and voting for the radical right in Europe. Europ. Union Polit. 18, 98–118. doi: 10.1177/1465116516678932

Lubbers, M., Gijsberts, M., and Scheepers, P. (2002). Extreme right-wing voting in Western Europe. Eur J Polit Res 41, 345–378. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.00015

Lubbers, M., and Smeekes, A. (2022). Domain-dependent National Pride and support for the radical right: pride in the Nation's history. Sociol. Forum 37, 1244–1262. doi: 10.1111/socf.12837

Mackie, D. M., Maitner, A. T., and Smith, E. R. (2009). “Intergroup emotions theory” in Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination. ed. T. D. Nelson (New York: Psychology Press), 285–308.

Marchlewska, M., Cichocka, A., Panayiotou, O., Castellanos, K., and Batayneh, J. (2018). Populism as identity politics: perceived in-group disadvantage, collective narcissism, and support for populism. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 9, 151–162. doi: 10.1177/1948550617732393

Marzouki, N., and McDonnell, D. (2016). “Introduction: populism and religion” in Saving the people: How populists hijack religion. eds. N. Marzouki, D. McDonnell, and O. Roy (New York: Oxford University Press), 1–11.

Milligan, M. J. (2003). Displacement and identity discontinuity: the role of nostalgia in establishing new identity categories. Symb. Interact. 26, 381–403. doi: 10.1525/si.2003.26.3.381

Mols, F., and Jetten, J. (2014). No guts, no glory: how framing the collective past paves the way for anti-immigrant sentiments. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 43, 74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.08.014

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C., and Kaltwasser, C. (2018). Studying populism in comparative perspective: reflections on the contemporary and future research agenda. Comp. Pol. Stud. 51, 1667–1693. doi: 10.1177/0010414018789490

Prusik, M., and Lewicka, M. (2016). Nostalgia for communist times and autobiographical memory: negative present or positive past? Polit. Psychol. 37, 677–693. doi: 10.1111/pops.12330

PVV (2023). Nederlanders weer op 1: PVV Verkiezingsprogramma 2023 [Dutch people back at 1: PVV Election program 2023]. Available at: https://www.pvv.nl/verkiezingsprogramma.html. Accessed 22 February 2024.

Rico, G., Guinjoan, M., and Anduiza, E. (2017). The emotional underpinnings of populism: how anger and fear affect populist attitudes. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 444–461. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12261

Rooduijn, M. (2021). Radicaal-rechts komt in drie smaken in de Kamer. Wat zijn de verschillen? [The radical-right comes in parliament in three flavours: What are the differences]. De Correspondent. Available at: https://decorrespondent.nl/12221/radicaal-rechts-komt-in-drie-smaken-in-de-kamer-wat-zijn-de-verschillen/f46cc601-6871-0eb7-1e64-b79c6800b06e. Accessed February 22 2024.

Rooduijn, M., Burgoon, B., Van Elsas, E. J., and Van de Werfhorst, H. G. (2017). Radical distinction: support for radical left and radical right parties in Europe. Europ. Union Polit. 18, 536–559. doi: 10.1177/1465116517718091

Rooduijn, M., Van Der Brug, W., and De Lange, S. L. (2016). Expressing or fuelling discontent? The relationship between populist voting and political discontent. Elect. Stud. 43, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.006

Rydgren, J. (2004). The populist challenge: Political protest and ethno-nationalist mobilization in France. New York: Berghahn Books.

Rydgren, J. (2007). The sociology of the radical right. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 33, 241–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131752

Salmela, M., and von Scheve, C. (2017). Emotional roots of right-wing political populism. Soc. Sci. Inf. 56, 567–595. doi: 10.1177/0539018417734419

Schnabel, P. (2018). Met mij gaat het goed, met ons gaat het slecht: Het gevoel van Nederland [I’m fine, but we’re not doing well: Feeling of the Netherlands]. Amsterdam: Prometheus.

Schreurs, S. (2021). Those were the days: welfare nostalgia and the populist radical right in the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden. J. Int. Comp. Soc. Policy 37, 128–141. doi: 10.1017/ics.2020.30

Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Routledge, C., and Arndt, J. (2015). Nostalgia counteracts self-discontinuity and restores self-continuity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 45, 52–61. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2073

Sipma, T., Jacobs, K., Lubbers, M., Spierings, N., and Van der Meer, T.W.G. (2021). Dutch parliamentary election study 2021: research description and codebook. Available at: https://ssh.datastations.nl/file.xhtml?fileId=25752andversion=2.1

Smeekes, A. (2015). National nostalgia: a group-based emotion that benefits the in-group but hampers intergroup relations. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 49, 54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.07.001

Smeekes, A. (2019). “Longing for the good old days of ‘our country’: understanding the triggers, functions and consequences of national nostalgia” in History and collective memory from the margins: A global perspective. eds. S. Mukherjee and P. S. Salter (Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers), 53–77.

Smeekes, A., Jetten, J., Verkuyten, M., Wohl, M. J. A., Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Ariyanto, A., et al. (2018). Regaining in-group continuity in times of anxiety about the Group’s future. Soc. Psychol. 49, 311–329. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000350

Smeekes, A., Sedikides, C., and Wildschut, T. (2023). Collective nostalgia: triggers and consequences for collective action intentions. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 62, 197–214. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12567

Smeekes, A., and Verkuyten, M. (2015). The presence of the past: identity continuity and group dynamics. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 26, 162–202. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2015.1112653

Smeekes, A., Verkuyten, M., and Martinovic, B. (2015). Longing for the country’s good old days: national nostalgia, autochthony beliefs, and opposition to Muslim expressive rights. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 54, 561–580. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12097

Smeekes, A., Wildschut, T., and Sedikides, C. (2021). Longing for the “good old days” of our country: national nostalgia as a new master-frame of populist radical right parties. J. Theoretic. Soc. Psychol. 5, 90–102. doi: 10.1002/jts5.78

Spierings, N. (2020). “Why gender and sexuality are both trivial and pivotal in populist radical right politics” in Right-wing populism and gender: European perspectives and beyond. eds. G. Dietze and J. Roth (Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag), 41–58.

Steenvoorden, E., and Harteveld, E. (2018). The appeal of nostalgia: the influence of societal pessimism on support for populist radical right parties. West Eur. Polit. 41, 28–52. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2017.1334138

Steenvoorden, E. H. (2015). A general discontent disentangled: a conceptual and empirical framework for societal unease. Soc. Indic. Res. 124, 85–110. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0786-4

Taggart, P. (2004). Populism and representative politics in contemporary Europe. J. Polit. Ideol. 9, 269–288. doi: 10.1080/1356931042000263528

Uslaner, E. M. (1989). Looking forward and looking backward: prospective and retrospective voting in the 1980 federal elections in Canada. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 19, 495–513. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400005603

Van der Bles, A. M., Postmes, T., LeKander-Kanis, B., and Otjes, S. (2018). The consequences of collective discontent: a new measure of zeitgeist predicts voting for extreme parties. Polit. Psychol. 39, 381–398. doi: 10.1111/pops.12424

Van der Bles, A. M., Postmes, T., and Meijer, R. R. (2015). Understanding collective discontents: a psychological approach to measuring zeitgeist. PLoS One 10:e0130100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130100

Van der Brug, W., and Fennema, M. (2007). Causes of voting for the radical right. Int. J. Public Opinion Res. 19, 474–487. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edm031