- 1Department of Political Science, Central European University, Vienna, Austria

- 2CEU Democracy Institute, Budapest, Hungary

It is often assumed that right-wing authoritarian and populist parties appeal primarily to negative feelings such as frustration, fear or alienation, and that positive sentiments appear in their discourse mostly in the form of nostalgia. Our hypothesis is that this description fails to apply to leaders in power. This article employs a mixed-methods approach, using a novel dataset of Viktor Orbán’s (Fidesz - Hungary) and Jarosław Kaczyński’s (PiS - Poland) speeches. After grouping positive sentences, a structural topic model identifies central topics, while the qualitative part describes and contextualizes the nature of the detected positive messages. Our analysis reveals that Orbán and Kaczyński incorporate various types of positive sentiments, such as optimism, pride, and efficacy, into their discourse. Contrary to popular belief, they dedicate considerable attention to discussing the future and utilize various rhetorical devices to convey positive messages. These messages are intrinsically interwoven with the leaders’ visions of past and future, offering insights into the underlying framework of their fundamentally conflict-centered and illiberal worldview. This study challenges the notion that right-wing authoritarian politics rely solely on “politics of fear”. Instead, it suggests that such leaders employ positive affective appeals as a form of emotional governance.

1 Introduction

After the collapse of Communism, June the 4th became a day of angry, mostly far-right, protest actions in Hungary. June the 4th of 1920 was the day when the post-WWI peace treaty was signed in the Grand Palace of Trianon in Versailles, France, codifying the loss of two-thirds of Hungary’s previous territories. A considerable portion of the population has never accepted the new borders, and this issue played an important role in polarizing Hungarian society once political contestation became possible. The left-wingers and liberals stood for good relations with the neighbors and considered the issue of the peace treaty as politically irrelevant, while the radical nationalists were adamant to demonstrate outrage on this day. The mainstream right was in perpetual dilemma how to behave.

When Fidesz gained power in 2010, it turned June the 4th into an official memorial day, the Day of National Unity. The Orbán-government elevated the century-old events into the very focus of national memory politics, just like the radicals wished, but with a positive spin. The newly introduced memorial-day celebrations left ample room for airing grievances, but the emphasis was placed on the fact that the nation, as a cultural body, survived the historical tragedy and was able to re-emerge as a powerful, cohesive force, despite the divisions created by the new national borders. Even more importantly, at least from a practical-political perspective, June the 4th became the day when the discourse could focus on the efforts (both symbolic and material) of the government aimed at improving the lives of Hungarians across the Carpathian Basin. The day of domestic tension was turned into a guaranteed annual PR-stunt for the governing party.

This reframing of the historical memories encapsulates the intricate interplay of negative and positive emotions in the discourse of right-wing authoritarian actors. It also indicates the ability of such actors to instrumentalize history, and to channel negative sentiments into uplifting narratives that strengthen the legitimacy of the government.

This context lays the foundation for our research question, which was triggered by two, widely shared, observations. The first one is that right-wing authoritarian and populist parties tend to appeal to negative feelings, such as frustration, fear, and alienation (Wodak, 2015; Salmela and von Scheve, 2017; Kinnvall, 2018), and positive sentiments appear in their discourse mostly in the form of nostalgia for an idealized past (Betz and Johnson, 2004; Busher et al., 2018). The second is the similarly well-established assumption concerning the difference between incumbents and opposition (Nai, 2020): while opposition parties are expected to emphasize the negative aspects of political processes, to express the concerns of citizens and to cast doubt on the ability of authorities to tackle social problems, government parties are supposed to radiate optimism, highlight achievements, and present social challenges as manageable (Thesen, 2013; Seeberg, 2017).

Our research question, following from the juxtaposition of these two observations, is: How should the discourse of governing authoritarian parties look like? Given the expectations listed above, such actors must be under cross-pressure. Most authoritarian-minded parties of democratic regimes come to power on a wave of discontent. In power, they are in continuous tension with the international elites and with the various authorities of the liberal international world order. As a result, a considerable degree of negativity must be built into their public discourse. At the same time, being in government, they must sell their time in office as a success. They must convince the doubters, including domestic voters and international investors that their governance is stable, effective, and has a promising future. This implies reliance on positive messages.

The small body of literature addressing cross-pressures faced by governing right-wing authoritarian and populist forces focuses either on the question of whether these parties moderate or on how voters react to incumbency (Luther, 2011; Bobba and McDonnell, 2016; Kim, 2021). The conundrum of affective party discourse has received little attention so far.

In order to examine how the countervailing pressures play out, we select two authoritarian actors in power within the European Union: Viktor Orbán (Fidesz - Hungary) and Jarosław Kaczyński (PiS - Poland). Orbán is in office continuously since 2010 (13 years); altogether he has been PM for 17 years, so far. Kaczyński’s party has been in office between 2005 and 2007, and then between 2015 and 2023, altogether he and his party have dominated the Polish government for 10 years, so far.

First, we review the most relevant theoretical expectations. Then, after explaining the selection of the cases, we introduce our sources and empirical methods. The bulk of the article is devoted to the quantitative and qualitative analysis of major political speeches. Finally, we identify major similarities and differences between the Polish and the Hungarian material, with a focus on the modes of combining positive and negative emotions. We detect in the speeches a future-oriented, hopeful perspective, a “we can do it” approach. This perspective acknowledges the existence of existential threats and conflicts, but it projects self-confidence. The speakers combine performance-based and ideological justifications, basing their righteousness on the assumed moral superiority of communitarianism over individualism and on the unity between the party, the leader, and the nation.

2 Theory

The relevance of emotion in party rhetoric is increasingly recognized by academic research. Emotions were found to affect various aspects of political behavior such as opinion formation, group norms and or party choice (for a review see Brader and Marcus (2013)). Therefore, it also comes to no surprise that political actors use emotions strategically to appeal to voters (Kosmidis et al., 2019).

While all politicians employ emotions when addressing voters, right-wing authoritarian leaders have been shown to be particularly likely to use narratives of disaster, insecurity, and threat, in order to appear as heroic fighters for their people (Eatwell, 2018). Anxiety, anger and fear have been particularly often associated with right-wing authoritarian politics (e.g., Wodak, 2015). These sentiments can frame a wide array of social issues, from immigration to ethnic relations, or employment. The negative framing strategy can help to capture the support of the losers of globalization, the ‘left behind’ (Betz, 1993). The insecurity and distrust caused by the economic and social changes of the last decades further widened the possibility of appealing to resentment and hatred against supposedly threatening outgroups (Salmela and von Scheve, 2018).

The anger felt toward the present is often combined with a positive orientation toward the past (Wodak, 2015; Hochschild, 2016), a nostalgic longing for secure, essentialist and stereotypical social identities and roles. In Europe in particular, the desires for restoration are focused on a monocultural, racially homogeneous, and neatly defined collection of separate societies (Norocel et al., 2020). Having said that, it is important to note that the talk about past glory can have future-oriented implications, as exemplified by the “Make America Great Again”-type slogans.

The emphasis on negative sentiments has deep intellectual and academic roots in the research of authoritarianism. The psychoanalytic model that dominated the literature for many decades linked authoritarianism to resentment, desire for revenge, lack of self-worth and punitiveness (Adorno et al., 1950). Reich’s (1970) theory identified sexual frustration as the root cause. The empirical literature that points to disgruntled young men as the main source of right-wing authoritarian parties contributes further to the bleak portray of authoritarianism.

Interestingly however, not all psychological research equates authoritarianism with negative emotions. Altemeyer (1983), while confirming that fear from a dangerous world plays a major role behind the submissiveness, aggressiveness, and conventionalism of right-wing authoritarians, detected a force that is as important as fear, but is gratifying: self-righteousness, the firm belief that one is on the right side of history.

The other major alternative (or version) of authoritarianism in political psychology is social dominance orientation (SDO), the demand for a hierarchical world in which one’s group subdues others (Pratto et al., 2006). SDO may be a negative orientation in terms of its social impact, but for those who are characterized by such sentiment it is functionally positive, unlike anger, frustration, or fear.

Further studies noticed the occasional presence of pride, enthusiasm, joy and hope in the discourse of the far right, largely stemming from the positive affect toward the national in-group and major historical events (Pilkington, 2016; Widmann, 2021; Doroshenko and Tu, 2023). By presenting a secure, prosperous, and glorious future and by promising a wealthy and homogeneous society, nationalist politicians give voters uplifting emotional tools to cope with contemporary social challenges (Wahl, 2020).

In fact, right-wing authoritarianism entails some degree of positivity by definition, as the in-group must be constructed as a morally valuable and comparatively superior social unit. Nationalist-authoritarian forces can be expected to refer to themselves, to those represented by them, and to the potential inherent in their group even more appreciatively than other political actors (Benoit et al., 1998) in order to stress the valuable nature of group membership. The established feelings of belonging and solidarity can be then further utilized, by political actors (for an overview see Cox, 2021).

When considering the broader political context of such actors, the necessity of positive messages to show strength and superiority also becomes apparent. Most liberal democratic arrangements, including internationalism, free markets, multiculturalism, mobility across countries and the emancipation of minorities (especially sexual minorities) are considered by experts, academia, and the political mainstream not only morally valuable but also, to some extent, inevitable, being part of social development, modernization, and in general, change of time. Those who are opposed to liberal democracy must challenge the inevitability-argument and they must point out the existence of alternative arrangements. Particularly in contrast to the widely assumed deterministic nature of globalization and multiculturalism, they must argue that operating a homogeneous society in the 21st century is possible, and it is compatible with (or even conducive to) economic prosperity, efficient state management, safety, individual happiness, and technological development. Given that the illiberal authoritarian forces are in minority in the European Union, they must project the ability to buck the trend.

In other words, “we can do it” must be an important message of such forces. But how can they make such an argument look plausible and how can this optimistic message square with the appeals to negative sentiments? Where do these parties find the positive energy given their permanently conflictual relationship with the liberal establishment?

In order to answer these questions, we examine how the past, the future and the in-group are constructed by Fidesz and PiS and how positive and negative sentiments are linked to their ideological worldview.

3 Case selection

Fidesz and PiS (Law and Justice, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość) are the two most prominent right-wing authoritarian parties in Europe. They are also the only two right-wing authoritarian parties that have dominated the executive, the legislative and the judiciary branches of government for a considerable time. These two parties and their governments also stand out as being in continuous conflict with the authorities of the European Union. In 2017, the European Commission initiated a procedure under Article 7 against Poland for violating rule of law and European Union values. The European Parliament started a similar procedure against Hungary in 2018 (European Commission, 2017, 2018). Additionally, Fidesz was forced to leave the European People’s Party in 2021 (Reuters, 2021).

Fidesz and PiS exhibit considerable amount of nativism, anti-liberalism, populism, homophobia, Euroscepticism and disrespect of judicial independence. Therefore, the literature studying populist and radical right-wing parties or maverick actors such as Donald Trump is relevant and applicable. But because both analyzed forces are mainstream parties in their own national contexts, the radical right concept, typically associated with niche, oppositional parties, is not the most adequate. The terms ‘(neo)authoritarian’ or ‘illiberal’ fit them better, as these terms do not imply a marginal position within the party system, while at the same time they emphasize opposition to liberal democratic principles such as state neutrality, rule of law, checks and balances, pluralism and non-discrimination based on ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, or race (Enyedi, 2020, 2024).

4 Materials and methods

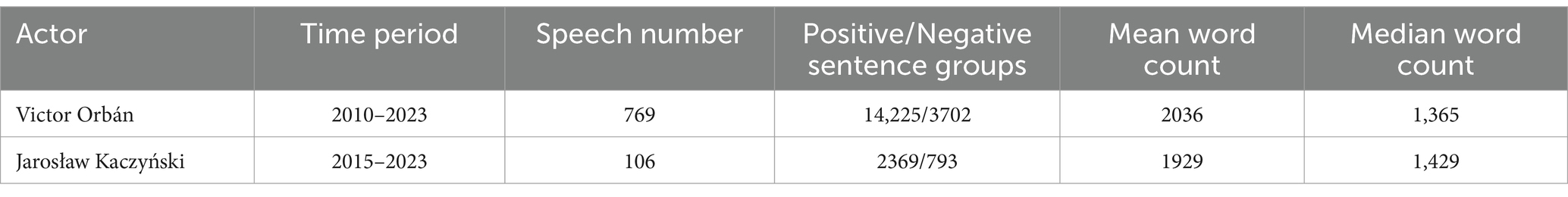

To address the above-mentioned questions, we are focusing on official speeches delivered by the two leaders. Our database includes speeches since the moment of government participation, which is 2010 for Orbán and 2015 for Kaczyński. The cut-off date for both cases is the 2023 Polish election. For the Orbán-related data set, we are analyzing speeches translated to English by official sources1. The large amount of care Orbán’s administration invests into publishing and translating these speeches indicates that they are particularly relevant for the self-representation of the Hungarian leader. This is less so with Jarosław Kaczyński, who speaks less frequently and does not have officially translated speeches. His speeches were transcribed and translated from video recordings by PiS as well as TVP Info, a Polish public broadcaster.2 Table 1 shows an overview of the data used for the analysis.

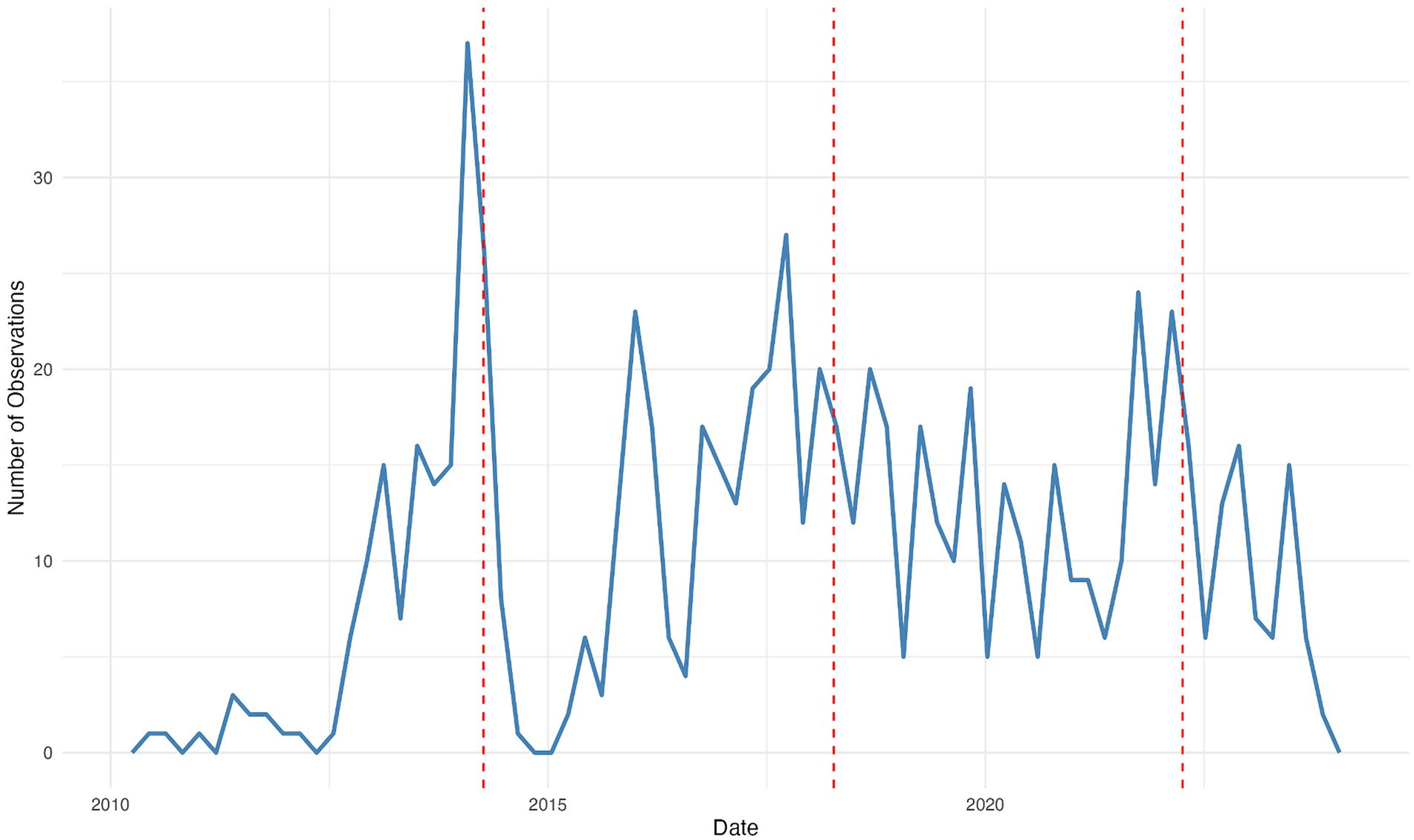

The larger number of Orbán-speeches reflects both the longer time of Orbán in office and the fact that for him public lectures are much more important than for Kaczyński, who prefers to work behind the scenes. Figures 1, 2 show the time points of the speeches. The data is not entirely balanced across time due to the larger time period and higher speech frequency of the Hungarian case, however, since we are interested in the overall discourse, the low number of speeches of some years does not pose a problem.

Figure 1. Speech distribution across time for Viktor Orbán. Elections are indicated by the red-dotted line.

Figure 2. Speech distribution across time for Jarosław Kaczyński. Elections are indicated by the red-dotted line.

Emotions in political texts can appear in two ways: in nouns and adjectives that directly refer to emotions and in emotional connotations. Nouns like anger, fear, pride, and adjectives like loving, afraid, or angry are straightforward examples of the former categories. Emotional connotations refer to words that are not emotional terms per se but signify a value judgment or an opinion related to the emotional attitude of the speaker such as referring to challenges versus opportunities.

To measure the sentiment of the speeches, we rely on the Lexicoder Sentiment Dictionary (LSD), a dictionary which has been trained on political texts. LSD assigns a value from 1 (positive) to −1 (negative) to each word and then takes the average for the respective unit of analysis such as sentences (Young and Soroka, 2012). We have separated each speech in groups of three sentences3 and measured their sentiment using LSD.

In the next step, in order to dig deeper into the nature of the positive sentences (meaning those that had a value higher than 0), we performed initial pre-processing steps such as tokenization, removal of non-relevant text elements (i.e., stop words, punctuation), and stemming to reduce words to their root form. Then we have created a topic model using each pre-processed sentence group as input. Using the stm library for R (Roberts et al., 2019), we employed a Structural Topic Model (STM) that considers the prevalence of multiple topics within a document. Furthermore, document metadata such as dates and the legislative period have been added to the model as covariates and thus have been considered when calculating the topics. The number of topics was established based on the most reasonable trade-off according to the model diagnostic values and interpretability.

Below we report on the results of the topic model analyses, complementing the quantitative analyses (see Supplementary material for an overview) with qualitative observations. For the qualitative analyses of Orbán’s discourse we have focused on the 12 speeches given at the Transylvanian Free University (Băile Tușnad) between 2010 and 2023. These annual speeches are treated are given very prominently by Orbán and his administration as they are designed to give a holistic picture of world politics and the government’s goals within the international context. For Kaczyński we have included all available Independence Day speeches as well as major PiS speeches such as the PiS Congress or program conventions in our time-frame, altogether 21 speeches.

5 Results

Before turning to the topic model analyses and to the qualitative interpretation of the leading emotions and arguments, let us consider the ‘big picture,’ the overall ratio of positive and negative sentiments in the speeches. The results of the LSD-analysis showed that the two leaders strike a very similar balance between positivity and negativity, devoting about 70% of their sentences to positive emotions. More precisely, the ratios of positive sentences were 67% in case of Kaczyński and 74% in case of Orbán. It seems that the cross-pressure that exists between the need to express grievances and to radiate confidence was largely solved in favor of the latter.

5.1 Hungary

For the Orbán speeches STM resulted in the identification of 18 topics. Table 2 presents them in the order of decreasing relevance.

5.1.1 The west declines, but…

As Table 2 shows, the mapping of the topics of positive sentences produced a somewhat paradoxical result: the most prominent topic, Questioning European Politics and Identity, has some pronounced negative aspects. This observation also applies to the sixth topic, National Sovereignty and Border Defense. Through these topics Orbán discusses socio-political developments seen as detrimental such as immigration, the federalization of the European Union and the rule of political correctness. The discussion of these phenomena often contains criticisms of specific EU policies, such as the sanctions against Russia or the migration- and border policies, but it is also integrated into a generic and historical ‘decline of the West’ narrative. Within this frame the speaker frequently reminds the audience that the share of Europe in world economy, population, influence, or technological achievements is rapidly diminishing.

These topics show that Orbán does not shy away from discussing negative phenomena, even in otherwise positive sentences. But how can the respective sentences become ultimately positive? The answer is in the rhetorical means and arguments that turn the negative aspects of reality into positive factors. The scrutiny of the STM topics and of the chosen Transylvanian speeches reveal the techniques.

First, while Europe is declining, the West is doomed, and the European Union mismanages the challenges, the rest of the world is described as thriving. Already in 2010 Orbán declared, for example, that “the whole of the Western world is in crisis, while in India and China there is economic growth of 5–10%. We get news that the euro is crackling and crumbling…. it is worth remembering that it is actually Western-style capitalism that has been in crisis for the last 10 years… other areas than Europe have risen with tremendous speed because they have held on to certain values” (2010-T).

The intention to contrast the West with the rest remained a leitmotif across the entire period. In 2023 he sounded just like 13 years earlier: “the current trends favor Asia and China – be those trends in economics, technological development, or indeed military power… Asia, or China, stands before us fully attired as a great power. It has a civilizational credo: it is the center of the universe, and this releases inner energy, pride, self-esteem and ambition. It has a long-term plan” (2023-T). Or consider the 2012 speech on the very same topic: “The crisis is not a world crisis, because in fact only the United States and Europe are struggling with similar issues. The countries of Asia, meanwhile, are developing, the countries of South America are prospering, and the peoples of Africa, although they started from the bottom, are undoubtedly moving upwards. So, something has gone wrong in the Western world, not in the world, but in the Western world, and in Europe in particular, things are going wrong” (2012-T).

But why should his listeners who are Europeans be happy about this news? How can this be uplifting? The 2012 speech shows the way how Orbán turns the topic around. After making the point that in Europe “things are going wrong” he continued: “while Western Europe is not coping with the crisis, and is even getting deeper into it, Central Europe is becoming more confident in its crisis management.” So, the speaker divides Europe into two hostile units, the Eastern and the Western parts, and identifies with the former.

Orbán acknowledges in the above cited speech that in the past Easterners imitated the West, but today, “There is no one to imitate, no recipe for success that, if translated here, in Transylvania or in Hungary, would make life easier for us. We have to figure out what the situation is, what our problems are, we have to identify our problems, and we have to find answers by incorporating the experience of others, of course, but we cannot believe that simply transplanting certain things from there will solve the difficult problems of our lives” (2012-T).

In other words, a method that was used in the past, such as imitation, does not work anymore. Is this good or bad news? For Orbán it is positive: “I see this as freedom. At first you would think that this is a problem. You could argue for it, but on the whole, it is a great intellectual freedom, a great opportunity. And if we have confidence in ourselves that we are capable of understanding the processes in which we live, if we are capable of working out solutions, solutions that bring about a better life, and if we believe that we are capable of organizing ourselves to do so, then the advantage that we have over the West in crisis management today is clearly ours. If we dare to say that there is no point in copying Western Europe, but that we must build our own economic systems in the spirit of freedom, if we dare to say that, then we will have taken a giant step toward success” (2012-T).

Clearly, in Orbán’s vision Hungary’s fate is not tied to the West. Hungary and its neighborhood are removed from Europe and can expect a very different future. Moreover, while the West is in decline, Hungary is not, thanks to the country’s unity, its loyalty to Christian roots, and the wise decisions of the leadership. Not only is Hungary more successful than the West, but the West is increasingly aware of this new configuration: “[…] the situation today is that the torch of those we could follow has been extinguished. So, the recipe for a way out of the crisis, for the right way to settle down in the new era, cannot be found in the West today. In fact, it is as if we are one step ahead of the others in finding solutions, which are then subsequently adopted by the West” (2011-T).

5.1.2 Central Europe

The unit most often contrasted with the West is Central Europe. Again, this is a region that is simultaneously part of the global West and is distinct from it. The references to the region could be found throughout most topics identified by the STM (especially Changes and Challenges and Hungary’s history and culture) and it emerged also as a distinct (and second most important) topic, labeled by us Economic Growth and Cooperation in Central Europe. The inclusion of the Balkans within this topic indicates that Orbán, a strong advocate of EU enlargement, hopes for the emergence of a sizable counter-pole to Western hegemony within the European Union. This hope is only strengthened by the repeated emphasis on Central Europe’s (economic) growth, future-oriented politics, and openness for collaboration – especially toward countries that are seen critically by the West such as China.

The contrast between the future of Central Europe and the West is profound. Already in 2011, he predicted: “in the period following the economic crisis, the center of gravity of economic growth in the European Union will be in Central Europe” (2011-T). Two years later he reasserted: “economic growth in the whole of the European Union today can come primarily from Central Europe, so that the economic reserve is actually in Central Europe, and the growth potential comes from here” (2013-T). Five years later he generalized the difference further: “And there is another Europe, the countries who were admitted to the European Union later, which is called the new Europe. This Europe is viable, full of energy, capable of renewal, and seeking answers to the new challenges. This part of our continent is prosperous” (2016-T).

5.1.3 Governmental performance

Six of the topics identified by our quantitative analysis are relatively conventional terrains for politicians in office: Political Achievements and Renewal, Hungarian Cultural and Academic Achievements, Economic Policies and Industrial Development, Urban Development and Infrastructure, Financial Policies and (Foreign) Investments and Economic Development. It is easy to understand how these topics support the feelings of satisfaction and pride. Next to presenting the Hungarian economy as robust and competitive, and the government as effective and resolute, the topic Hungarian Cultural and Academic Achievements also includes references to Hungarian successes in sport, science, or technological innovations.4 These achievements are often discussed through a contrast with a badly performing West.

Instead of hammering on past glory, the Orbán-speeches are future-looking: “In 2010 we Hungarians also decided that we wanted to regain our country, we wanted to regain our self-esteem, and we wanted to regain our future. […] In the modern world there can be no strong community or strong state in a country without growth in science and innovation, and without the ability to open up to the industries of the future. I’m not saying that we have already arrived at this position, but over the past 7 years we have at least knocked on the doors of the new industries of the future” (2016-T). The stereotypical past-oriented perspective attributed to conservatives (Lammers and Baldwin, 2018) does not apply.

The confidence is based on a long list of recent victories: “today we can say that we are sitting here with optimism, knapsacks full of plans and the feeling of gaining in strength every day.… I can inform you that today the Hungarian nation possesses the political and economic capabilities – and soon the physical capabilities also – to defend itself and to remain independent. We’ve regained our sovereignty, the IMF has gone home, we have successfully fought against Brussels and we have defended our borders. Today Hungary is on a promising course: sound finances, falling debt, strong growth, rising wages, strengthening small and medium-sized enterprises, growing families and vigorous nation-building. Of course, everyone can and should perform better. Individual Hungarian citizens, Hungarian businesses and the Hungarian government can and should do their jobs better; but the reality is that today the threat to Hungary’s continued progress on its promising course does not come from inside the country, but from outside” (2019-T). The world may have gone mad, but the Hungarian nation is intact and thriving.

5.1.4 Community and fight

Guriev and Treisman (2022) have recently argued that the discourse of ‘spin dictators’ such as Orbán is primarily framed though the terms of conventional democratic politics, such as economic growth, investment, balanced budget, etc. The five STM topics discussed above partly confirm this claim, with the caveat that the economic achievements are directly linked to international rivalry. The authors subsequent assertion, namely that leaders like Orbán are not ideological, is, however, questioned by our results. At least two of the topics, Hungarian Resilience and Hungarian Unity and Strength appear to be rather ideological, highlighting Hungarians’ persistence in the face of upheavals. The statements that belong to the Hungarian National Identity, Hungary’s Collective Success and National Pride, and Hungary’s History and Culture topics combine nationalist and patriotic slogans with commitment to Christian faith and with the insistence that the new generations are to be socialized into these values. Together with the topics Societal and Cultural Transformations and Changes and Challenges, the respective sentences venerate the historical and current struggles of the nation, emphasizing how Hungarians have persevered through the centuries and how they managed to turn the table around. These sentences fit both into a civilizationist (Enyedi, 2024) narrative and into the self-presentation of the leader as one who is capable to transform the country.

Next, to rejecting liberalism on both political and epistemological grounds, the speaker advances a moral and a realist argument. According to the moral frame historical justice guarantees future satisfactions for the nation, while according to the realist argument the illiberal systems are more robust and effective than the liberal democratic ones. Given such arguments the ambitions are unusually high: “I interpret the two-thirds victory we won in 2010 as our mandate to bring to an end two chaotic decades of transition and to build a new system…Looking back over the past years, I can tell you that we have seen the successful stabilization of a political system based on national and Christian foundations” (2018-T).

Values and achievements-based self-congratulations are fused: “When in 2011 we created the new Constitution – a Hungarian, national, Christian constitution, different from other European constitutions – we did not make a bad decision. Indeed, let us say that we did not make a bad decision, but rather made the right one; because since then we have been beset by the migration crisis, which clearly cannot be dealt with on a liberal basis. And then we have an LGBTQ, gender offensive, which it turns out can only be repelled on the basis of the community and child protection law” (2023-T).

The Hungarian National Identity, Hungary’s History and Culture, Hungarian Resilience and Societal and Cultural Transformation are the most past-oriented and nostalgic topics, but even these focus on the post-communist phase and not on the distant past. They specifically highlight how Orbán has improved the country, despites the many challenges, and how the government has succeeded against all odds. The terms ‘fight’ and ‘victory’ associated with Hungarian Resilience bring together the feelings of determination and efficacy. Victory is considered not only in the context of concrete results but also as something that gives moral authority to the actor. The losers are treated with a condescendence that has clear religious tones: “we must also thank those who turned against us and provided an opportunity for the good to win the day regardless, because after all, without evil, how could the good be victorious?” (2014-T).

Accordingly, in 2018 Orbán declared that the goal is no longer to work on specific policies, institutions, or even regime, but on a new ‘era’: “The foundations seem to be solid and durable, so it is not unreasonable for us to designate the task for the coming 4 years as the building of an era…. In such a situation, backed up by electoral support representing a two-thirds majority, a national government cannot commit itself to anything less than setting itself great aims: great aims of a kind that were previously unimaginable; the kind of great aims that will give meaning to the work of the years to come…With a time horizon of 2030 in mind, we want Hungary to become one of the European Union’s five best countries in which to live and work. By 2030 we want to be among the EU’s five most competitive countries. By 2030 we should halt our demographic decline. By 2030 we should physically link Hungary within its present-day borders with the other areas: motorways and dual carriageways should extend as far as the state borders. By 2030 let Hungary become independent in terms of its energy supply, which has become an important dimension of security. Let us complete the Paks nuclear power development, and start using new energy sources. We should suppress widespread illnesses, build the new Hungarian Defence Force, and set about building up the economic structure of Central Europe. This is the perspective from which everything I’m about to say will make sense. From our viewpoint here, the most important element is our plan to rebuild the entire Carpathian Basin”5 (2018-T).

In 2023 he came back to the idea of the new ‘era’ that began with the 2010 victory of Fidesz, elaborating further on its ideological foundations: “In 2010 we opened a new era, and we must not lose sight of that – whatever the difficulties we face, whatever storms, lightning bolts and thunderstorms greet us. Ours is a new era, which has spiritual and economic foundations.

First let us briefly recall the spiritual foundations of this era. These spiritual foundations are summarized in the Constitution. And the new Hungarian Constitution is the document that most clearly distinguishes us from the other countries of the European Union. If you read the constitutions of other European countries, which are liberal constitutions, you will see that at the heart of them is the “I.” If you read the Hungarian Constitution, you will see that it is centered on the “we.” The Hungarian Constitution’s essence, its founding premise, is that there is a place that is ours: our home. There is a community that is ours: this is our nation. And there is a way of life – or perhaps more precisely an order to life – which is ours: our culture and our language. Therefore, in the Constitution our spiritual starting point is that the most important things in human life are those which cannot be obtained alone. This is why the “we” is at the heart of the Constitution. Peace, family, friendship, law and community spirit cannot be obtained alone. And, Dear Summer Camp, even freedom cannot be obtained alone: the person who is alone is not free, but lonely. All the good things in life are essentially based on cooperation with others, and if these are the most important things in our lives, says the Hungarian Constitution, then these are the things that society and the legal system must protect” (2023-T).

This ‘togetherness’ is both a moral obligation for Hungarians and a source of strength. The world may be uncertain and dangerous, but given the current position of the Hungarians, they may be the ones who benefit from it: “I think we would do better to feel that the era of “anything can happen” that stands before us, although it bears with it uncertainty according to many and could even mean trouble, contains at least as many chances and opportunities for the Hungarian nation. And so instead of fear, isolation, and withdrawal, I recommend fortitude, thinking ahead and rational but courageous action for the Hungarian community of the Carpathian Basin and in fact for the whole Hungarian community scattered throughout the world. It could easily be the case that, since anything can happen, our time will come” (2014-T).

There are many hints in the speeches at upcoming conflicts, but the audience is reassured that Hungary will win them: “Hungary has ambition. Hungary has communal ambitions, and indeed national ambitions. It has national ambitions, and even European ambitions. This is why, in order to preserve our national ambitions, we must show solidarity in the difficult period ahead of us. The motherland must stand together, and Transylvania and the other areas in the Carpathian Basin inhabited by Hungarians must stand together. This ambition, Dear Friends, is what propels us, what drives us – it is our fuel. It is the notion that we have always given more to the world than we have received from it, that more has been taken from us than given to us, that we have submitted invoices that are still unpaid, that we are better, more industrious and more talented than the position we now find ourselves in and the way in which we live, and the fact that the world owes us something – and that we want to, and will, call in that debt. This is our strongest ambition.” The Hungarian expression used by Orbán in this sentence for calling in the debt is “be is fogjuk vasalni” a clear commitment that the government will impose its will on those who owe to Hungarians. In these sentences a narrative of Hungarian innocence and victimhood is combined with national pride and exceptionalism (Sadecki, 2022), and a firm belief that the nation is on the right track.

Based on the assertion that “what we Hungarians do is successful, beyond doubt,” Orbán is confident enough to identify the path Europe should follow: “I am going to tell you today what the European Union should do differently in order to banish fear and uncertainty from the lives of the people of Europe” (2016-T).

Next, to a belief in willpower, the source of Orbán’s optimism is to be found in a joyous attitude to fight. “Hungarians want to fight. They do not want to endure what is happening, they do not want to be small people who will somehow adapt in the name of survival, as has so often been the case, but they want to fight. […] the Hungarians want to fight against things at home that in the past have made us unsuccessful, untrusting and unhappy, but which we have accepted and been willing to live with, to see as part of our lives. That era is over. It is a long time since the Hungarian nation, the Hungarian part of the Hungarian nation in Hungary, has been in such a state of determination and capacity for action” (2011-T).

The idea of Hungary is a path breaker, one that faces opposition but is ultimately vindicated, is one of the most often repeated tropes of the speeches. “Indeed right now no one can rule out the European mainstream following the same path in the next few years which it has itself tried so hard to prevent Hungary following. This is how the black sheep will become the flock, and this is how the exception will become the rule” (2016-T).

Orbán claims a path-breaker role also in challenging the transnational elite: “back in 2010, well before the US presidential election, we were forerunners of this approach, the new patriotic Western politics. We ran quite a distance ahead of the others, and in politics those who run further ahead are not greeted with recognition, but with something quite different. If they can endure it, however, they may well earn their recognition, just as Hungary is earning increasing recognition” (2017-T). The message is: fighting pays off.

He frequently justifies adversarial behavior with the reference to the evil intensions of foreign actors: “Well, we have to say that Europe today has created its own political class, which is no longer accountable and no longer has any Christian or democratic convictions. And we have to say that federalist governance in Europe has led to an unaccountable empire. We have no other choice. For all our love of Europe, for all that it is ours, we must fight.” (2023-T).

The fight is heroic: “our generation has been given a historic opportunity to strengthen the Hungarian nation. This will be an unconscionably difficult struggle and we are facing an uphill battle […] We still have to answer the question of whether it is really possible […] is it possible to successfully reject migration, to protect families, to defend Christian culture, to announce a program of national unification and nation building, and to create an order of Christian freedom? Is it possible in all this to survive against the full force of an international headwind, and indeed to make it succeed? Ladies and Gentlemen, I do not think we are dreaming. Yes, all this is possible, as it has been over the last 10 years – but only if we stand up for what we think and what we want. If we are brave, if we have valor – and now we need valor – and if we unite. As this camp’s slogan says, “The camp is united!” Well, this is what our next 15 years will be about” (2019-T).

Next, to the generic “we can do it” mentality, the speeches show a more specific belief that a working formula has been found. “I can now tell you objectively that not since the Treaty of Trianon has Hungary been as close as it is today to regaining its strength, prosperity, and prestige as a European country. And not since Trianon has our nation been as close as it is today to regaining its self-confidence and vitality […] Twenty-seven years ago here in Central Europe we believed that Europe was our future; today we feel that we are the future of Europe” (2017-T).

The importance of this idea led Orbán to repeat the last sentence 1 year later: “30 years ago we thought that Europe was our future. Today we believe that we are Europe’s future” (2018-T). Hungarians have all the attributes of success: “Once more we are strong, we are determined, we are brave, and we have our vigor, money and resources. And over the past few years we have proved to our neighbors that whoever cooperates with the Hungarians will prosper. Now is the time to rebuild the Carpathian Basin.” (2018-T).

5.2 Poland

The STM identified 9 major topics in the positive statements of Kaczyński (Table 3). These topics primarily refer to the activities and achievements of the Polish government under his party’s leadership and his visions for the country.

5.2.1 The harmony of state and nation and the social mandate for change

A major bloc of Kaczyński’s positive statements rests on the claim that the radical transformation started by him and his party in 2015 significantly improved social care and education and has even led to the re-establishment of national sovereignty (Economic and Social Development). A more democratic order was achieved, one dominated by fundamental Polish values, such as honor and commitment to family (Polish Democracy). The main rival, Civic Platform, is considered as being non-democratic because while it was in government it “made no secret of the fact that its aim was to annihilate the only real opposition, namely Law and Justice” (2016/09/05).

The defense of unique Polish interests and values appears in virtually all topics, dominating the one labeled by us as Patriotic Governance. Within this topic the issue of secure national borders looms large. In Kaczyński’s understanding, patriotism very specifically calls for the defense of the nation’s honor against accusations made by foreigners, such as concerning the role of Poles in the Holocaust. The commitment of PiS to the nation and the mandate for transformative changes is also central to the Political Leadership topic.

Kaczyński’s speeches tend to be confined more narrowly to political matters than Orbán’s speeches, often discussing procedures and institutions such as the government, the Prime Minister, Civic Platform, constitution, program, panels, etc. This is particularly true for the topic of Political Vision and Policy Framework, used primarily for the elaboration of the party’s and the government’s program.

As indicated by some of the descriptions above, and similarly to the Hungarian case, one can detect shadows even in the positive segments of Kaczyński’s rhetoric. They come out most clearly in the topic of State Control and Manipulations, where the speaker contrasts the regained power of the genuinely Polish state with the dark manipulations of the media. By highlighting the evilness and the wide-ranging influence of hostile media actors, he can present his ability to govern the country in a different direction as an even more formidable performance.

5.2.2 Promises kept

The close reading of the 21 speeches shows that, in contrast to Orbán, Kaczyński places more emphasis on fulfilled promises: “Our party must become, to some extent it already is, but it must become, entirely the party of the dreams of the Poles. And if we start from this starting point, we can say with no small satisfaction that the Law and Justice Party has proved in these 3 years, but also in 2005–2007, that it can govern, that it can govern honestly, that it can be credible, that it can do everything that promised” (2018-C2). The PiS government has a “difficult uphill road” ahead, but “we can do it, we can do it, we have proved it!” (2019-EC).

In line with the dominant position of the Economic and Social Development topic, Kaczyński frequently returns to the topic of economic growth relative to Western European standards. This is often expressed in percentages: “in 14 years we can catch up with the European Union average. Today we have only 71%, but in 21 we can catch up with Germany. And it’s not just this current thesis. Maybe it will be even faster.” (2019-PC). The development is typically discussed in a historical perspective: “for many years on our territory we could not do what was necessary from the point of view of our interests. And today we are showing that we can, that that time that ended on the one hand 30 years ago but elements of it still persisted and continue is coming to an end. Post-communism is coming to an end. What is needed, ladies and gentlemen? What is needed is good governance” (2019-C).

The confidence of winning uphill battles is firmly rooted in recent experience. In 2016, for example, he remembered 2011 when his opponents were in control of all positions: the government, the president, all the “control institutions,” the local authorities, the courts, and the media, they even had “the support of so-called celebrities.” The situation was dire: “It seemed that we had no chance.” But then, “[w]e showed determination. We showed toughness. And we won! Resistance, toughness, determination were important, necessary, absolutely essential conditions for this victory. But it was also very important that we had invention, that we had ideas, that we were able to show the public, despite the media blockade that there is an alternative” (2016-Co).

5.2.3 Against all odds

The formidable nature of the challenges is given ample room in the speeches. When speaking about the attacks against his government he stated “[i]n those attacks, we observe elements of preparation, perhaps even training. This attack is an attack that is meant to destroy Poland. It is meant to lead to the triumph of those forces whose rule will virtually end the history of the Polish nation as we have known it till this day” (2020-D). The evil forces are omnipresent: “[t]he process we undertook had to and did take place amidst battles, internal and external battles, battles against total opposition and pressure from outside, from other countries, those who wanted to see Poland just as helpless in the face of external forces, and inside directed by elites.” These forces are, however, ultimately defeated. “But the question has to be asked: after these almost 6 years, can one speak of success? Yes, ladies and gentlemen, one can speak of success. We have changed the system. We have changed it in the state dimension, in the social dimension” (2021-Co).

Just as in case of Orbán, the audience is not only assured that the party is victorious in the fights, but also that these fights are epic. The narrative presented is similar to the story of David against Goliath, combining excitement with the sense of historical (or divine) mandate: “in the face of the fact that the opposition took on the unprecedented character of total opposition and began to resort to external forces, we had to stand up. We had to answer the question of whether it was possible to make an attempt. And we made an attempt. […] Never has any government, and I say this for the entire period of 6 years, done as much for Poland as we have. And that’s why I conclude with one call, forward, forward and once again forward to victory” (2022-C).

In a less sharp and aggressive tone, but otherwise similarly to Orbán, Kaczyński also highlights the divergence between his country and the rest of Europe. Speaking about the attacks against family and Church, he stated: “We must defend ourselves against this. We must defend our freedom, because this is the defense of our freedom. And Poland, this I repeat again and again, must be a state of freedom. Even if everywhere else in Europe this freedom had in fact been abolished” (2015-I). The European context presents various threats to Poland, a new direction would be needed, but one needs a leap of faith to hope for a better future for the continent: “It is possible to say that today only we and the Hungarians are in favor of change in the European Union, but no one else. […] One should, ladies and gentlemen, one should believe that the impossible can be possible. One must believe that we can prevail” (2016-I). It is uncertain whether this struggle will be successful, but the fate of Poland, just as the fate of Hungary in Orbán’s speeches, is not tight to Europe: “Poland should be an island of freedom, even if everywhere else it will be limited. We were once an island of tolerance in Europe, and now we should become an island of freedom” (2016-FD). The ‘tolerance’ that he demands is the toleration of views that are marginalized by political correctness.

Again, just as Orbán, Kaczyński radiates confidence in terms of domestic rule, but somewhat differently than the Hungarian leader, he keeps relating this confidence to the ability of fulfilling campaign promises. He considers his party, “a center for sensible, rational thinking about Europe. We must be aware of this, and we should not have any complexes. We must, ladies and gentlemen, move forward. I repeat, we must keep our promises. We must be competent and honest. We must reject complexes. […] We must, ladies and gentlemen, move forward with confidence and formulate new proposals, new proposals for society” (2016-Co).

Both leaders consider inferiority complex as their main enemy, both claim competence, but honesty is more central to Kaczyński than to Orbán, and the Polish leader is more focused on the fight against what he calls the pedagogy of shame. “Our pride has been degraded for over 20 years; we were taught to be ashamed; our image was discredited outside our borders; we fell victim to slanders. We can and we will stand up against this phenomenon in Poland, by changing our education programs and introducing new cultural values, but we will also stand up on the international and global scene. We must want to defend our pride and dignity in order to be what we ought to be – a great European nation!” (2015-E) “The assault of putting to shame everything that is Polish (the so-called “pedagogy of shame”), all this offensive, which undermines our community values, our national values, fortunately this assault is in a large part defeated. And it is losing ground among all generations – in particular, among our youth. Good is again separated from evil. Everything that was done to confuse good and evil is now dwindling” (2016-FD).

Six-seven years after the above-quoted speeches this issue still concerned him. In his 2022 Independence Day speech he called again for the “[r]ejection of the pedagogy of shame, but rejection not only in the declaration, but also in school programs, in teaching, in social pedagogy, in art” (2022-I). Such repetitions also indicate that the struggle to regain national self-confidence is a never-ending one.

History and identity are important in the speeches of the Polish leader. The very foundations of the values of PiS are located in Polish history, and he also asserts that the “state must be deeply rooted in history, in tradition, in the values of the nation” (2015-I). But history does not dominate, the expressed attitudes are typically forward-looking: “Above all, we need to get our economy moving more than before, on the basis of technological progress. Progress brought about by the most advanced technologies of today” (2023-C). The values rooted in the past are brought together with the aspired progress “Poland must be modernized, in terms of organization, in terms of technology, in terms of social services, yes, we will modernize Poland, but we will not modernize the Polish spirit. Because it must be the basis of all that we will do. It will lead Poland to regain its strength, to the greatness that we Poles deserve” (2015-I).

To the extent history appears in the speeches, this is primarily through the memory of fights, struggles, multiple defeats, and occasional victories. There is, in fact, very little nostalgia in this discourse: “Polish history has unfolded in such a way that the very notion of a nation, and in particular the notion of the Polish nation and the very existence of the Polish nation, has sometimes been questioned, and not only by our external enemies, but also by our internal opponents” (2019-PC).

The past is, mainly, dark, the future is, mainly, bright: “We really are beginning to be able to afford to undertake it, to undertake the rebuilding of all that we have lost in this difficult history of ours” (2023-PC1). Moreover, the memory of the historical difficulties is a resource in itself. For example, speaking about the conflict with the EU (concerning the independence of the judiciary) he said: “It is difficult, but remember that it is not difficult compared to what it was 103 years ago” (2021-I).

6 Discussion

The analyzed positive sentence-clusters of the speeches share a surprisingly large number of commonalities. First, and most importantly from our point of view, they give more attention to the future than to the past. This may be so partly because these leaders in general speak less about the past than typically assumed, and/or partly because most of their sentences referring to the past are negative and therefore, they do not appear in the above STM analysis. The qualitative analyses of selected speeches allow for both interpretations.

Second, virtually all speeches contain references to dangers. But these dangers are overcome with courage, hard work and determination. It is important to emphasize that the future-oriented, hopeful perspective is not harmonious. It is built on fight, though one that promises to be victorious. Together with a heavy use of moralized language (typical of far right discourse, cf. Lamont et al., 2017), both politicians present themselves as courageous actors who have prevailed against evil and are saving their country.

To conclude, and contrary to the expectations derived from the bulk of the literature, the two illiberal and authoritarian leaders have been found to be largely positive in their discourse. They do not project a Pollyannaish, everything-is-great, image of the world, they actually frequently address negative phenomena. But they turn negativity into positivity through various rhetorical means and arguments. Their audiences learn that these leaders can shelter them from negative world tendencies, that loyalty to historical values can be combined with competence and professionalism, and that the regained sovereignty allows the respective countries to follow their own path. The occasional references to historical defeats are primarily used to highlight resilience.

We have also detected differences between the two leaders. Kaczyński has a somber, organization-centered, relatively conventional rhetoric, with hints of harbored grievances, while Orbán occasionally reveals that the political fight is source of joy for him. Furthermore, Orbán represents a slightly different discourse by being more radical in challenging liberal democratic norms and by placing his struggles more consequently into a global perspective. But both leaders present their countries as islands of peace and freedom in a world gone mad and both consider their parties’ rule as ushering in a new historical period in the countries’ history. The projection of unity between the party and the nation, the claim of replacing individualism with communitarian spirit provides them with moral superiority over their liberal opponents. They are also similar in associating the governmental achievements with the nationalist, conservative and anti-communist value agenda of their parties. The performance-based and ideological justifications go hand in hand.

7 Conclusion

This study has investigated the interplay of positive and negative emotions as well as the prevalence and the role of visions of past and future in speeches of Viktor Orbán and Jarosław Kaczyński. One general conclusion to be drawn from these two cases is that major political actors need to employ a complex array of emotions, and that positive appeals are part of the package even in conflict-ridden contexts. The authoritarian actors, who increasingly occupy office in (formerly) liberal democratic countries, need to project stability and success of their government to secure re-election. This fact, together with the recent failures of liberal democracies and together with the positive aspects of right-wing authoritarianism, such as the belief in the strength of the community, the assumed competence of the leaders and moral self-righteousness, pave the way in front of a fundamentally optimistic outlook.

While many of the contemporary social processes have been discussed in negative light in the analyzed discourses (just like in case of radical right parties, cf. Steenvoorden and Harteveld, 2018), the assurance of a great future dominated. This outlook is embedded in similar trajectories: both partied had their roots in anti-communist opposition, both were defeated after a short spell in government, and both emerged victoriously, beating the odds. This temporal dynamic gave credence to the “we can do it” mentality. The many half-hearted and failed attempts of international actors, including the European Union itself, to discipline the two governments, just boosted their feeling of invincibility. The protest rhetoric has not been abandoned, but it became packaged into the main message of ability to govern. Notwithstanding the specificities of the two trajectories, the discursive templates used by Kaczyński and Orbán are accessible, and most likely used, by other forward-looking illiberal leaders around the world.

Given that we considered only two political actors, we must be cautious about generalizing our findings. Many authoritarian, populist and illiberal parties and leaders never get into power. The examined actors were atypical also because they were examples of ‘radicalized mainstream parties,’ and not rebels from the fringes such as other Central and Eastern European populist right-wing parties (Gherghina et al., 2021). These, and other, specificities have undoubtedly shaped their rhetoric. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that academia should pay more attention to the uplifting, future-looking and optimistic appeals of the opponents of liberal democracy in order to understand their success. The victory of Giorgia Meloni in Italy, the move of Marine Le Pen toward the mainstream, and her increased chances to capture the executive power in France, or the good electoral performance of Geert Wilders in the Netherlands suggest that the marriage of governmental responsibility with neo-authoritarian value priorities is increasingly a realistic possibility. Most analysts predict for such situations the toning down of the radical value positions, but our results point to an equally likely option: the embedding of the authoritarian values into positive, competence-centered narratives.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

FW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZE: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the HORIZON EUROPE European Research Council: [Grant Number 101060899].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1390587/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^https://2015-2022.miniszterelnok.hu/en/ and its archived versions as well as https://abouthungary.hu/speeches-and-remarks and https://2010-2014.kormany.hu/en/prime-minister-s-office/the-prime-ministers-speeches

2. ^Transcription was done using happyscribe.com and translation into English are based on DeepL. Both were checked for accuracy by native speakers.

3. ^The same has been tried with both smaller and larger sentence groups, but three sentences seem to provide the right amount of contextual information to correctly measure the sentiment while also providing enough information for a topic model. Groups of three sentences also results in feasible text lengths for the STM as their mean is a length of 71/62 words. This is relevant for topic models such as STM that assume the presence of multiple topics within one document, which can particularly affect the accuracy of analyzing texts with less than 50 words (Vayansky and Kumar, 2020).

4. ^Maerz and Schneider (2020) also found strong links between sport achievements, national pride, and collective memory.

5. ^Note that most of the territory of the Carpathian Basin does not belong currently to Hungary.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., and Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Benoit, W. L., Blaney, J. R., and Pier, P. M. (1998). Campaign’96: A functional analysis of acclaiming, attacking, and defending. Westport, Conn: Praeger.

Betz, H. G. (1993). The new politics of resentment: radical right-wing populist parties in Western Europe. Comp. Polit. 25, 413–427. doi: 10.2307/422034

Betz, H. G., and Johnson, C. (2004). Against the current—stemming the tide: the nostalgic ideology of the contemporary radical populist right. J. Polit. Ideol. 9, 311–327. doi: 10.1080/1356931042000263546

Bobba, G., and McDonnell, D. (2016). Different types of right-wing populist discourse in government and opposition: the case of Italy. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 21, 281–299. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2016.1211239

Brader, T., and Marcus, G. E. (2013). “Emotion and political psychology” in The Oxford handbook of political psychology. eds. L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, and J. S. Levy (New York City: Oxford University Press), 165–204.

Busher, J., Giurlando, P., and Sullivan, G. B. (2018). Introduction: the emotional dynamics of backlash politics beyond anger, hate, fear, pride, and loss. Human. Soc. 42, 399–409. doi: 10.1177/0160597618802503

Cox, L. (2021). “Conclusions: the emotional power of nationalism” in Nationalism: themes, theories, and controversies. ed. L. Cox (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan), 133–147.

Doroshenko, L., and Tu, F. (2023). Like, share, comment, and repeat: far-right messages, emotions, and amplification in social media. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 20, 286–302. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2022.2097358

Eatwell, R. (2018). “Charisma and the radical right” in The Oxford handbook of the radical right. ed. J. Rydgren (New York City: Oxford University Press), 251–268.

Enyedi, Z. (2020). Right-wing authoritarian innovations in central and Eastern Europe. East Eur. Polit. 36, 363–377. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2020.1787162

Enyedi, Z. (2024). Illiberal conservatism, civilisationalist ethnocentrism, and paternalist populism in Orbán’s Hungary. Contemporary Politics, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/13569775.2023.2296742

European Commission. (2017). Proposal for a COUNCIL DECISION on the determination of a clear risk of a serious breach by the Republic of Poland of the rule of law. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52017PC0835 (Accessed November 15, 2023).

European Commission. (2018). European Parliament resolution of 1 march 2018 on the Commission’s decision to activate article 7(1) TEU as regards the situation in Poland. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2018-0055_EN.html (Accessed November 15, 2023)

Gherghina, S., Miscoiu, S., and Soare, S. (2021). “How far does nationalism go? An overview of populist parties in central and Eastern Europe” in Political populism. eds. R. Heinisch, C. Holtz-Bacha, and O. Mazzoleni (Baden-Baden: Nomos), 239–256.

Guriev, S., and Treisman, D. (2022). Spin dictators: the changing face of tyranny in the 21st century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in their own land: a journey to the heart of our political divide. New York: New Press.

Kim, S. (2021). Because the homeland cannot be in opposition: analysing the discourses of Fidesz and law and justice (PiS) from opposition to power. East Eur. Polit. 37, 332–351. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2020.1791094

Kinnvall, C. (2018). Ontological insecurities and postcolonial imaginaries: the emotional appeal of populism. Human. Soc. 42, 523–543. doi: 10.1177/0160597618802646

Kosmidis, S., Hobolt, S. B., Molloy, E., and Whitefield, S. (2019). Party competition and emotive rhetoric. Comp. Pol. Stud. 52, 811–837. doi: 10.1177/0010414018797942

Lammers, J., and Baldwin, M. (2018). Past-focused temporal communication overcomes conservatives’ resistance to liberal political ideas. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 114, 599–619. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000121

Lamont, M., Park, B. Y., and Ayala-Hurtado, E. (2017). Trump's electoral speeches and his appeal to the American white working class. Br. J. Sociol. 68, 153–180. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12315

Luther, K. R. (2011). Of goals and own goals: a case study of right-wing populist party strategy for and during incumbency. Party Polit. 17, 453–470. doi: 10.1177/1354068811400522

Maerz, S. F., and Schneider, C. Q. (2020). Comparing public communication in democracies and autocracies: automated text analyses of speeches by heads of government. Qual. Quant. 54, 517–545. doi: 10.1007/s11135-019-00885-7

Nai, A. (2020). Going negative, worldwide: towards a general understanding of determinants and targets of negative campaigning. Gov. Oppos. 55, 430–455. doi: 10.1017/gov.2018.32

Norocel, O. C., Hellström, A., and Jørgensen, M. B. (2020). Nostalgia and hope: Intersections between politics of culture, welfare, and migration in Europe : Springer Nature.

Pilkington, H. (2016). Loud and proud: Passion and politics in the English defence league : Manchester University Press.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., and Levin, S. (2006). Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: taking stock and looking forward. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 17, 271–320. doi: 10.1080/10463280601055772

Reuters. (2021). Hungary's Fidesz quits European conservative group: 'Time to say goodbye'. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hungary-politics-fidesz-epp-idUSKBN2BA2CA (Accessed November 15, 2023)

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., and Tingley, D. (2019). Stm: an R package for structural topic models. J. Stat. Softw. 91, 1–40. doi: 10.18637/jss.v091.i02

Sadecki, A. (2022). From defying to (re-) defining Europe in Viktor Orbán’s discourse about the past. J. Eur. Stud. 52, 255–271. doi: 10.1177/00472441221115565

Salmela, M., and von Scheve, C. (2017). Emotional roots of right-wing political populism. Social Science Information, 56, 567–595. doi: 10.1177/0539018417734419

Salmela, M., and von Scheve, C. (2018). Emotional dynamics of right-and left-wing political populism. Human. Soc. 42, 434–454. doi: 10.1177/0160597618802521

Seeberg, H. B. (2017). What can a government do? Government issue ownership and real-world problems. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 56, 346–363. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12175

Steenvoorden, E., and Harteveld, E. (2018). The appeal of nostalgia: the influence of societal pessimism on support for populist radical right parties. West Eur. Polit. 41, 28–52. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2017.1334138

Thesen, G. (2013). When good news is scarce and bad news is good: government responsibilities and opposition possibilities in political agenda-setting. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 52, 364–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02075.x

Vayansky, I., and Kumar, S. A. (2020). A review of topic modeling methods. Inf. Syst. 94:101582. doi: 10.1016/j.is.2020.101582

Wahl, K. (2020). “Fear, hate, and Hope: a biopsychosociological model of the radical right” in The radical right. (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 21–60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-25131-4_2

Widmann, T. (2021). How emotional are populists really? Factors explaining emotional appeals in the communication of political parties. Polit. Psychol. 42, 163–181. doi: 10.1111/pops.12693

Wodak, R. (2015). The politics of fear: what right-wing populist discourses mean. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Keywords: speeches, authoritarianism, emotional governance, positive emotions, Hungary, Poland

Citation: Wagner F and Enyedi Z (2024) They can do it. Positive Authoritarianism in Poland and Hungary. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1390587. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1390587

Edited by:

Ekaterina R. Rashkova, Utrecht University, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Sergiu Miscoiu, Babeș-Bolyai University, RomaniaFernando Casal Bertoa, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Wagner and Enyedi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Franziska Wagner, d2FnbmVyX2ZyYW56aXNrYUBwaGQuY2V1LmVkdQ==

Franziska Wagner

Franziska Wagner Zsolt Enyedi

Zsolt Enyedi