- School of Governance, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

The role of emotions in politics is drawing increasing scholarly attention. Yet, despite this heightened interest, the ways in which politicians concretely appeal to emotions of their target audience are still blurry. Let aside how they do so in different contexts. This article focuses on an affect that is frequently mentioned as the key driver explaining the electoral appeal of populist radical right-wing parties (PRRPs): resentment. In that respect, several authors have used the term “the politics of resentment,” even though the exact definition of resentment often remains unclear. In this article, we theorize what resentment precisely is and how it is used politically, and hypothesize how it is mobilized in different ways by PRR parties in different contexts. Empirically, then, we employ content analysis to study a corpus of party documents of PRRPs in three West and two East European countries from 2004 onwards and identify three types of resentment mobilized by the radical right: (1) redistributive resentment; (2) recognitory resentment; and (3) retributive resentment. Despite being expressed in a more heterogeneous way than we theoretically expected, these forms of resentment share important commonalities that, we argue, can help to better understand the electoral appeal of radical right-wing parties.

Introduction

From the field of social movements studies (Goodwin et al., 2001; Jasper, 2018; Knops and Petit, 2022) to political theory and philosophy (Nussbaum, 2013; Lordon, 2016; Rosanvallon, 2021), the role of emotions in politics is drawing increasing scholarly attention (Thompson and Hoggett, 2012; Demertzis, 2013; Jasper, 2018). In the field of political behavior, this trend is illustrated by a growing interest in “affective” rather than “ideological” polarization (Iyengar et al., 2012, 2019). The underlying “affective turn” (Clough and Halley, 2007, see also Marcus, 2002; Knudsen and Stage, 2015), however, has only been limitedly explored by researchers studying the populist radical right, especially when it comes to the political supply side. As Betz and Oswald (2022), p. 136 recently put it: “What we are still largely missing are discourse-oriented studies that explore how right-wing populist parties concretely appeal to emotions, what tropes and rhetorical devices they use to evoke and elicit an affective response among their target audience.”

In this article, we aim at filling this gap in the literature, by focusing on the affect of resentment, which has frequently been identified as a crucial factor to understand contemporary political behavior. For instance, as the “affective driver of reactionism” (Betz and Oswald, 2022, p. 122), as “one of the motivating factors behind a populist-inspired Euroscepticism” (Abts and Baute, 2022, p. 44)” as well as “the main driver behind the rise of identity-based particularism” and “affective polarization” on both sides of the Atlantic (Betz, 2021). Correspondingly, resentment constitutes one of “the most prominent emotions cited in the literature on populism in general and radical right-wing populism in particular.” (Betz and Oswald, 2022, p. 122). This prominence not only applies to the demand side, but also to the supply side, i.e., to the mobilization of resentment, which has primarily been associated with radical right-wing parties and leaders, whose rhetoric is “designed to tap feelings of ressentiment and exploit them politically” (Betz, 2002, p. 198).1

Despite its prominent position in the existing literature, and the ample attention given to “the politics of resentment” (e.g., Wells and Watson, 2005; Cramer, 2016; Fukuyama, 2018; see also Nord, 1986), the precise meaning of the notion of resentment remains unclear. Moreover, the “politics of resentment” has been studied in different contexts—particularly on the demand side—ranging from politically dissatisfied shopkeepers in London (Wells and Watson, 2005) to rural residents in Wisconsin feeling that they do not get their fair share (Cramer, 2016). To the best of our knowledge, though, the potentially different ways in which resentment is mobilized by different political actors in different political contexts have not been investigated yet.

To fill this gap, we build on existing literature to theorize (1) what resentment is; (2) how it is mobilized by populist radical right-wing parties; and (3) how these mobilizations manifest themselves differently in different contexts. By providing a clear, more operational, definition of the “politics of resentment” that allows for cross-case analyses, the article thereby innovates on what already exists theoretically. On the empirical side, the article contributes to the literature by offering a unique examination of how PRRPs tap into this affect in different political contexts, identifying key differences between established and new democracies. Focusing on relevant party documentation of PRRPs in three West and two East European countries—France, Italy, the Netherlands, Bulgaria, and Poland—we show the various ways in which these parties mobilize resentment, based on different types of perceived injustice and by referring to different in and outgroups. In the remainder of this article, we will first focus on our theoretical framework and empirical strategy, before presenting the results of this examination. In the concluding section then, we will reflect on the limitations of our study as well as the implications of our findings.

Theoretical framework

In this section, we answer three theoretical questions. First, what is resentment? Second, how is it mobilized by populist radical right-wing parties? And third, how are the politics of resentment expected to differ across different contexts?

What is resentment?

Resentment, as Betz (2021) put it, “is a highly complex, equivocal and ambiguous emotion.” An emotion, moreover, that tends to be treated as “an affective catch-all concept, covering a wide range of sentiments” (Abts and Baute, 2022, p. 40; see also Fanoulis and Guerra, 2017; Capelos and Demertzis, 2018; Capelos and Katsanidou, 2018), including powerlessness, fear, anger, bitterness, and shame (Banning, 2006, p. 83). To get a better grasp of this complex affect, it is helpful to follow Demertzis’s distinction between a Nietzschean and a non-Nietzschean understanding of resentment (Demertzis, 2006, see also Oudenampsen, 2018a).2 Nietzsche (2013), who wrote in German but consistently used the French word ressentiment, famously conceived the latter as a chronic, interiorized form of vengefulness among the weak and powerless, based on envy and impotence (Fassin, 2013), leading to passivity and inaction (Demertzis, 2006, p. 107). Along similar lines of persistence, passivity, and noxiousness, Nietzsche’s follower Scheler (1961) described ressentiment as lasting “rancor” (Groll), and characterized it as a “self-poisoning of the mind,” leading to “value delusions.”3 Resentment from a non-Nietzschean perspective, on the other hand, which is written in English and can be traced back to the writings of Hume (1986) and Smith (1759),4 (see also Fassin, 2013; TenHouten, 2018)—rather constitutes a form of moral anger or righteous indignation, in reaction to injury or inequality, and may inspire action, including class struggle. Resentment, then, is not necessarily impotent or helpless but can also be productive and forceful (Capelos and Demertzis, 2018, p. 412; TenHouten, 2018, p. 52–53; Abts and Baute, 2022, p. 43; see also Rawls, 1971; Marshall, 1973; Barbalet, 1998; Strawson, 2008). In this article, we take a non-Nietzschean stance. Accordingly, we refrain from using the French term ressentiment and define the notion of resentment as “a hostile emotion, qualified by the perception of having suffered a wrong” (Miceli and Castelfranchi, 2017:17).

It is important to emphasize that resentment differs from “anger” and “indignation,” two notions that tend to be associated with a non-Nietzschean conceptualization of resentment. More precisely, following Miceli and Castelfranchi (2017), p. 16, we conceive resentment (just as indignation) as distinct from the broader affect of anger, in that it is necessarily elicited by perceived injustice, whereas anger is not. Put differently, anger is about perceived harm-doing, whereas resentment (just as indignation) is primarily about perceived wrongdoing.5 This characteristic makes resentment a more clearly moral emotion than is simple anger (TenHouten, 2018, p. 54; see also Grant, 2008). While sharing the moral character with indignation, resentment differs from the latter, in the sense that it can be viewed as being a less “detached” emotion. That is, indignation constitutes a reaction to the wrongs suffered by other people, whereas resentment concerns reactions of people who are, or whose ingroup is, directly involved in a situation of perceived injustice (Miceli and Castelfranchi, 2017, p. 16; see also Rawls, 1971; Strawson, 2008).

Importantly, these situations of perceived injustice occur when valued resources (including status) that otherwise would be available to subjects are denied to them by an external agency, which privileges itself and/or outgroups instead (Abts and Baute, 2022, p. 44; see also Barbalet, 1992; Solomon, 1994).6 Our theorization of resentment, then, is fundamentally rooted in what sociologists call “relative deprivation,” i.e., a feeling that one (or one’s ingroup) is unfairly disadvantaged compared to a relevant referent or outgroup (Runciman, 1966; Pettigrew, 2016).7 As indicated by our emphasis on the “external agency,” it should be noted that this understanding, in addition to a “membership reference group” and a “comparative reference group” (Runciman, 1966), also implies a “wrongdoer” responsible for the perceived “situation of uncompleted equality” (Grandjean and Guénard, 2012, p. 13), thus triggering “the goal to retaliate” (Miceli and Castelfranchi, 2017, p. 21). That is, the desire to alter the subjectively unacceptable situation, by making the wrongdoers pay and “get even” with those who are considered to receive morally unfair privileges (Ibid., see also Rostbøll, 2023).8 To summarize, resentment, in our view, thus contains the following three key elements:

1. A situation of perceived injustice, occurring when valued resources (including status) are denied, and/or when outgroups are (considered to be) privileged.

2. A feeling of hostility vis-à-vis the perceived wrongdoer(s)—i.e., those seen as providing unfair privilege(s) to another group—and the perceived receivers of these privileges (which can be the same group).

3. A desire for retaliation, by making the wrongdoer(s) pay and “get even” with those who are seen as unfairly privileged.

How do PRR parties mobilize resentment?

Existing studies point at structurally different forms of resentment mobilization by the actors that are most frequently associated with “the politics of resentment”: i.e., populist radical left-wing parties, on the one hand, and populist radical right-wing parties, on the other (e.g., Betz and Oswald, 2022). The political programs of radical left-wing parties (and socialist movements more broadly) tend to be characterized by a bipartite structure. That is, these parties generally conceive “the people” in economic terms—through signifiers such as “the poor,” the “exploited,” or the “99 percent”—and oppose them to “big business” and “rich elites” that are held responsible for existing inequalities. The political agenda of radical right-wing parties, by contrast, is not based on socialism and its ideal of equality (Bobbio, 1996), but primarily characterized by anti-egalitarian nativism. That is, the idea “that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (“the nation”) and that non-native elements (persons and ideas) are fundamentally threatening to the homogenous nation-state” (Mudde, 2007, p. 19; see also Carter, 2005; Kitschelt, 2007; Betz, 2017). Accordingly, their rhetoric is not dyadic, but has a tripartite structure (see also Judis, 2016).9 Put differently, whereas populist radical left-wing parties tend to mobilize resentment by targeting financial, economic, and political elites while being relatively inclusive toward ethnic, religious, and racial “others” (Decker, 2008, p. 123; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2013), the discourse of populist radical right-wing parties is based on resentment toward elites and minorities (Banikowski, 2017; Brubaker, 2017; Gidron and Hall, 2017).10 Within this tripartite structure, notably associated with the radical right, we theoretically expect two forms of resentment to be relevant: redistributive resentment (which is about material resources and socio-economic opportunities) and recognitory resentment (which is about the symbolic appreciation of group identities).11

Redistributive resentment

When it comes to the mobilization of resentment in the realm of socio-economic opportunities and material resources, populist radical right-wing parties are expected to follow two distinct rhetorical routes: via welfare chauvinism and via culturalized producerism.12 Welfare chauvinism refers to the exclusion of non-natives from national welfare arrangements (Andersen and Bjørklund, 1990; Kitschelt and McGann, 1995; de Koster et al., 2013; Ennser-Jedenastik, 2016; Schumacher and van Kersbergen, 2016; Lefkofridi and Michel, 2017; Otjes et al., 2018). More specifically, PRR parties tend to depict non-natives in a hostile way, as unfairly privileged—e.g., regarding healthcare, jobs, housing, etc.—while pitting them against natives “who are entitled to keep the entire cake for themselves” (Rydgren, 2008, p. 746). Accordingly, welfare chauvinism relates to the promise of PRR parties to give priority to the deserving native people—notably the elderly, the sick, and the disabled (Ennser-Jedenastik, 2016)—through a sort of “reversed affirmative action” (Rydgren, 2008, p. 746), thus making them “get even” with those who are seen as unfairly privileged.

The second approach of radical right-wing parties to mobilize redistributive resentment is rooted in so-called “producerism” (Kazin, 1998; Kochuyt and Abts, 2017; Abts et al., 2021), according to which people who contributed more to society should be advantaged. By using this principle in a culturalized way, radical right-wing parties tend to support native “producers” (or “makers” as Rathgeb (2020) would say), whom they portray as the morally virtuous backbone of the economy (e.g., the “hard-working”) in opposition to non-native “profiteers” (or “takers”) that are depicted as “lazy free riders” who “exploit public welfare without contributing to it,” because they would be unable or unwilling to work (Rathgeb, 2020, p. 642, see also Lamont et al., 2017; Stockemer and Barisione, 2017; Ivaldi and Mazzoleni, 2019; Abts et al., 2021).13 By juxtaposing the distribution of resources and opportunities not only based on in/outgroup distinctions, but also on how much one group has put it versus another, the rhetoric of PRR parties fosters feelings of relative deprivation and hence feeds into what we refer to as resentment.

Importantly, in line with our conceptualization of resentment, which includes responsible “wrongdoers,” PRRPs are not only expected to target “profiteers” and “takers” (“below”) when mobilizing redistributive resentment—whether through welfare chauvinism or culturalized producerism—but also denounce political elites (“above”). This is done by portraying the latter as “self-serving” (Rathgeb, 2020) and criticizing them for supporting a welfare state that neglects the interests of the deserving common man while prioritizing undeserving recipients, notably immigrants (Abts et al., 2021, p. 35).

Recognitory resentment

The second form in which we expect PRR parties to mobilize resentment does not so much relate to the realm of material resources and opportunities, but rather to the domain of symbolic recognition given to different social groups. Admittedly, political representation is always symbolic (Bourdieu, 1991), and redistribution also implies recognition (see, e.g., Fraser and Honneth, 2003). For instance, when deserving “hard-working” citizens are contrasted to non-deserving “profiteers.” Yet, whereas redistributive resentment primarily relates to socio-economic issues, recognitory resentment relates to the politics of identity and difference. In that cultural domain, some groups “appear to have gained in visibility and recognition, such as ethnic and sexual minorities, while others have been losing out” (Betz, 2021). More specifically, as Brubaker (2017), p. 372 observed, “restrictions on speech deemed offensive or harmful to minorities, discourses and practices of multiculturalism, diversity, affirmative action, and minority rights, and the stigmatization of opponents of such discourses and practices as racist, xenophobic, or Islamophobic,” together with “the expanding recognition of LGBT rights and the stigmatizing of opponents of such rights as homophobic or (more recently) transphobic,” have created opportunities for populist radical right-wing parties to “attack political correctness and to speak in the name of a symbolically neglected, dishonored, or devalued majority,” thereby defending “traditional forms of marriage and family and traditional norms of gender and sexuality against the perceived symbolic elevation and special treatment of gender and sexual minorities.”14 In other words, as with redistributive resentment, recognitory resentment implies the idea of “reversed affirmative action” (Rydgren, 2008, p. 746). Not so much with respect to a material “cake” or socio-economic opportunities, though, but pertaining to the political appreciation of a group’s symbolically neglected, dishonored, or devalued identity. Accordingly, just as with redistributive resentment, recognitory resentment, when mobilized by the radical right, also implies a tripartite structure, in which political elites are portrayed as responsible “wrongdoers,” favoring the symbolic status of outgroups to the detriment of the “true” native population.

The politics of resentment across contexts

Based on the expectations described above, we argue that the political mobilization of resentment by PRR parties, while sharing a common core—i.e., three key elements within a tripartite structure—may differ in different contexts. Not only with respect to the situations of perceived injustice, but also with respect to the targeted outgroups and supported ingroups.

Redistributive resentment: welfare state versus aid chauvinism

When it comes to redistributive resentment, this variation is expected due to the fact that the in- and outgroups and the origins of what is to be shared may differ quite a lot. While similar in the logic of emphasizing disadvantage of a particular group, how Central and East European PRRPs approach welfare chauvinism is different since the outgroup has traditionally been formed by ethnic minorities and discriminatory discourse has only in recent years extended to immigrants as well (Cinpoeş and Norocel, 2020). What is key to distinguish here, is whether the outgroup is one that enjoys the same political rights as the ingroup, or not. Not only because of the potential effect on how parties mobilize against (or for) the former. But also because it has implications for the extent to which the “fate” of the outgroup is politically debated and by how many parties—i.e., as a niche or a central debate.

A second important factor for being able to evaluate the extent to which the politics of redistributive resentment operates differently in different contexts is that of the origin of the pie. In Western Europe, this often refers to a strong system of welfare support, which is perceived to be threatened or further exhausted by newcomers.15 In Eastern Europe, on the other hand, since most of these states are much poorer than their EU counterparts, a large part of what is considered as “the pie” are not welfare funds but structural aid funds from the EU. Given that the latter come in hand-in-hand with criteria on spending, conditions, and follow-ups, there are grievances of a part of the native population against minorities, which they are asked to treat as equals.16 In that sense, the term welfare chauvinism, which has originated with developed democracies’ socio-political situations in mind, can be revised to aid chauvinism regarding less or underdeveloped countries. The specific type of chauvinism—welfare or aid chauvinism—may also reflect the perceptions of different “wrongdoers”—while in Western Europe it is primarily the country’s own government (since it is responsible for immigration policy and how benefits get distributed). In Eastern Europe, we argue, the perceived wrongdoer for PRRPs is embodied, for a significant part, by the EU itself (since the EU provides conditions and asks for accountability for the use of its funding). Hence, in these countries, we would expect PRRPs redistributive political rhetoric to target both the country’s government and the EU.

Recognitory resentment: traditional versus secular contexts

When it comes to recognitory resentment, we, again, expect to see differences as to the groups that are supported by PRRPs as well as the rationale behind it. When it comes to the latter, authors in the existing literature tend to stress the importance of “traditional forms of marriage and family and traditional norms of gender and sexuality” among PRR parties (Brubaker, 2017, p. 372). However, these parties do not share quite the same societal values (Roy, 2019, p. 148). In fact, PRR parties in Western Europe, notably in secularized countries with a prominent protestant history, tend to support—to varying degrees and at least on the surface—individual rights and liberties, such as freedom of speech and gender equality, as well as LGBTQ rights (Meret, 2019; see also Mepschen et al., 2010; Duyvendak, 2011; van den Hemel, 2014, 2018; Oudenampsen, 2018b; Damhuis, 2019, 2020; Meret, 2019). Whereas PRRPs in Southern and Eastern parts of Europe tend to propagate more “traditional,” religiosity-based conservative societal outlooks (Meret, 2019, see also Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, 2022). And while in both contexts, PRRPs are expected to target Muslims when mobilizing recognitory resentment, existing studies regarding Eastern Europe also suggest that these parties tend to exclude the Roma minority in order to symbolically support the native ingroup (Rashkova and Zankina, 2017; Rashkova, 2021).

Empirical strategy

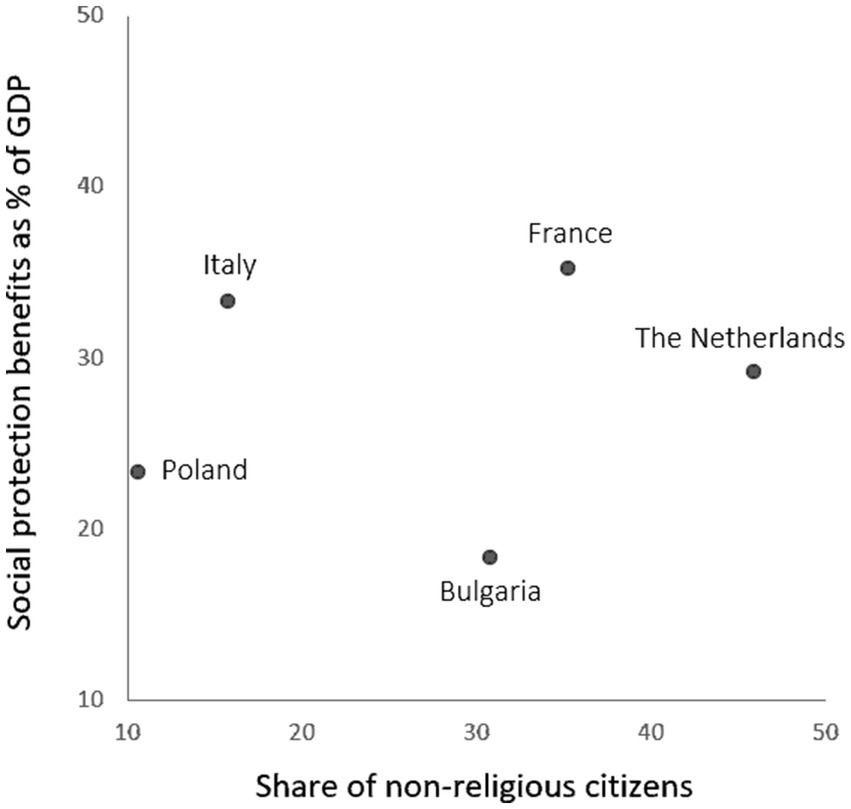

We selected five countries for our empirical analysis to assess how resentment is politicized by radical right-wing parties in different contexts:17 Bulgaria, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Poland. Our sampling strategy constitutes a balanced set of countries from both Eastern and Western Europe, which helps us understand the dynamics in each of these regions, and the differences and similarities between them, better. Moreover, as Figure 1 shows, these five countries provide a representative sample as they vary along two dimensions of our theoretical model, regarding redistributive and recognitory resentment, respectively. Concerning the former: social protection of benefits as a percentage of a country’s GDP (i.e., covering the share of valued resources that are redistributed) varies by more than 15 percentage points, with the two East European countries on the lower end of the spectrum, and the West European ones visibly higher. And in terms of the latter: the share of non-religious citizens with a country’s population (as a proxy for “traditional” versus “secular” forms of recognitory resentment), the sample of countries provides a mix, where we observe different levels of non-religious citizens that varies across the East–West dimension, with Poland, expectedly, having the lowest share of non-religious citizens and the Netherlands the highest.

Figure 1. Five selected cases along two dimensions: social protection benefits as percentage of GDP and share of non-religious citizens. Social protection benefits as percentage of a country’s GDP is based on Eurostat 2020 (European Commission 2023) Share of non-religious citizens per country is based on the Atlas of European Values Study (2017).

Within these five countries, we selected the electorally most relevant radical right-wing party over the past decades. In Bulgaria, this is the party Vazrazhdane (Revival, VZ).18 Vazrazhdane was established in 2014 as a political movement and first contested elections in 2017, when it was unsuccessful. It used the political crisis forming in Bulgaria around 2021 to enter parliament and has been the largest radical right “player” since. In France, we focus on the Front National (National Front, FN, founded in 1972 and renamed Rassemblement National, National Rally, or RN, in 2018), which has described as the “prototypical” radical right-wing party by numerous scholars (e.g., Kitschelt and McGann, 1995, Chapter 3; Rydgren, 2005; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017), and has played an important role in French politics for several decades. In Italy, we choose to examine Lega (initially Northern League, LN, rebranded as Lega in 2018), as it is the most clearly and consistently populist radical right-wing party in Italy in the period under study—more so than Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), which, despite ideological affinities with the radical right, can rather be classified as national-conservative (Bressanelli and de Candia, 2023; Vassallo and Vignati, 2023). For Poland, although there have been concerns about PiS becoming more radical, mainly due to its stances on the EU and its connection in the EP, the party as such and its core values remain mainstream. Konfederacia Wolność i Niepodległość (Confederation, KWN), on the other hand, markets itself as a radical right party and has been very active in politics as such, hence it is the case we study in Poland. Finally, in the Netherlands, we study the political discourse of Geert Wilders’ Partij voor de Vrijheid (Party for Freedom, PVV), as it has been the most important Dutch PRRP over the past decades and even became the largest party in the Netherlands in the 2023 general elections. For the purposes of this study and in order to have a balanced dataset of documents for each of the selected parties, we examine all-party electoral documents that are available on the parties’ websites for the period 2004–2023. Those include party manifestos and electoral programs for each election over the last 20 years (a full list of analyzed documents is in the Appendix). Initially, we wanted to analyze tweets, but soon realized that the use of social media differs significantly between countries, especially between regions, and therefore this was not going to lead to an informative study.

Since the goal of our analysis is not to provide frequencies or magnitudes but to give “the range of types” (Wright Mills, 1959, p. 236) of resentment mobilization by PRRPs in different contexts, we rely on a qualitative content analysis. This approach allows for describing and conceptualizing the meaning of qualitative data guided by (pre)defined rules (Krippendorff, 2019; Schreier, 2019). Our unit of analysis refers to statements, made by the selected parties, containing at least one element of resentment (out of the three described above). We have, therefore, manually read and coded each of the documents identified in our sample and retained all statements related to resentment. Following this procedure, a new statement was coded as soon as a hitherto unaddressed resentment-related statement was available in the examined document (see Bernhard and Kriesi, 2019 for a similar approach). Once we had identified all statements containing expressions of resentment, we followed an abductive coding procedure that combines both deductive and inductive aspects (Vila-Henninger et al., 2024; see also Thornberg, 2012; Tavory and Timmermans, 2014). In the first step, we coded the statements into one of the categories that were derived from our theoretical expectations. In addition to the concerned country and party, these categories concern the concrete elements of resentment (i.e., the situation of perceived injustice, intergroup hostility, and form of retaliation), as well as the type of resentment (a priori: redistributive resentment, including welfare chauvinism and culturalized producerism, as well as recognitory resentment). By doing so, we also generated inductive codes to document anomalous and surprising cases, including one type of resentment that we observed empirically, but we did not expect to find theoretically (retributive resentment). Similarly, the two redistributive forms of resentment (i.e., welfare chauvinism and culturalized producerism) were coded into several further subcategories, thus enabling us to develop and refine our theoretical expectations. In sum, our analysis is systematic in that it approaches the data in the same manner across countries and parties, yet flexible in that it allows for reconfigurations along the way.

Results

In what follows, we summarize the trends we find in examining the evidence gathered from our sample of radical right parties. More specifically, we observed three main types of resentment: mobilized by PRRPs redistributive resentment, recognitory resentment, and retributive resentment. The following sections will present our findings in more detail.

Redistributive resentment

Of all types of resentment present in the data we studied, redistributive resentment is—by far—the most prominent form in both Western and Eastern Europe. In line with our theoretical expectations, this type of resentment notably relates to welfare chauvinism, based on the nativist principle, or “elementary rule,” as the French National Rally (2022d) described, of “putting our own before others.” This “elementary rule” was sometimes invoked in a general sense, through statements on “social benefits” and “our welfare state,” generically. Yet, both Wilders’ Party for Freedom and the French National Rally particularly emphasized two specific policy domains when it comes to welfare chauvinism: healthcare and (social) housing. In these domains, the native ingroup would suffer from a situation of injustice, as non-natives are portrayed as unduly privileged compared to non-native, non-deserving outgroups. For instance, as the PVV leader claimed regarding healthcare in the Netherlands:

[W] e cannot have Dutch people avoiding healthcare because they cannot afford it, while asylum seekers incur over a thousand euros more in healthcare costs per year than a Dutch person and get everything for free. Every fiber of my body resists this injustice.

Similarly, in the build-up to the 2022 Presidential elections, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally invoked this core idea of welfare chauvinism—i.e., the native population receiving too little in comparison to non-deserving outside groups—to the domain of social housing. According to the National Rally, extending social housing to all legal migrants would not only be “detrimental to French citizens,” but also constitute “one of the suction pumps of immigration. The principle of national priority must therefore be applied to access to social housing. Our compatriots must be the first to benefit from national solidarity.”

Interestingly, our data show that redistributive resentment is not only articulated in opposition to migrants—who are accused of being privileged by responsible political elites—but, more recently, also in relation to climate change (PVV) and regional deprivation (RN). These resentment statements do not have a tripartite structure (elites/natives/outsiders), but a bipartite one, opposing “unworldly” and metropolitan elites to unfairly disadvantaged fellow citizens. For instance, the French National Rally claimed in several electoral manifesto’s that “The Ministry of Culture’s budget gives too much priority to Paris over the provinces, and this ratio needs to be reversed.” Similarly, in its electoral manifesto of the 2021 elections, the PVV stated that:

[W] e will not be lectured to by unworldly climate preachers. That is why we will put an end to the totally radicalized climate madness: the Climate Act, the Climate Agreement and all nonsensical measures will be immediately binned. We abolish all climate and sustainability subsidies immediately. No more money for nonsensical leftist hobbies, but more money in our people’s pockets. […] Already, hundreds of thousands of households live in energy poverty: they can barely or not at all pay their energy bills and often literally sit on the couch shivering from the cold. Energy is a basic need, but the climate frenzy has turned it into an extremely expensive luxury product.

When turning to Eastern European cases, our data reveal that the mobilization of redistributive resentment is, for the most part, different. In the rhetoric of both Bulgaria’s Vazrazhdane and Ataka and Polish’ Konfederacia, we see recurrent claims that foreign forces, notably the EU, unjustifiably try to take away resources belonging to the native population. For instance, the Party Platform of Vazrazhdane reads that:

[O] ur energy sector is a field in which the strategic interests of external powers have intersected and, in the absence of statehood, important elements of our energy system have been captured by them and shared between them.

Similar rhetoric can also be observed in the Electoral Programme of Konfederacia, which claims that: “The transport industry is responsible for 6% of Polish GDP and one million jobs. It has been destroyed for years by the European Union (Mobility Package) and PO-PiS governments.”19 To be sure, PRRPs in western Europe, notably the PVV, also target the EU in their redistributive resentment claims. Yet, similar statements tend to be more explicitly based on a logic of culturalized producerism, opposing “makers” (us, natives) versus “takers” (them, abroad), whereby—contrary to the East European cases—foreign “takers” are not so much pictured as a threat to the resources of the native population but rather as a burden. In its 2012 manifesto for the general elections, Their Brussels, Our Netherlands, the Dutch Party for Freedom literally used this term when claiming that: “The essence of the European dream is that our money flows south and east. Not vice versa. They have the joys, we have the burdens.” What we also did not observe in Eastern European cases were expressions of “culturalized producerism” targeted at outgroups within the confines of the national territory, i.e., directed at (“non-Western”) immigrants, who, in the terms of Le Pen’s RN, would “unduly benefit from our solidarity,” or, as the PVV stated more bluntly, would “cheat the Netherlands” through “massive welfare fraud and abuse.”

Interestingly, the situation of perceived injustice underlying this producerist form of redistributive resentment (i.e., of giving too much to non-deserving outgroups), was not only politicized by Le Pen’s RN in a way that resonates with the culturalized producerism, where ethnic others play a key role. It is also mobilized in an explicitly class-based manner, whereby socio-economic elites (e.g., “large groups,” “big business,” and “the most privileged”) are the main targets. Accordingly, this subtype of redistributive resentment is structured in a dyadic way, rather than in a tripartite fashion. While reflecting the historical and electoral affinities of this party family with small business owners (Castel, 2003; Ivarsflaten, 2005) as well as the French context in which class politics has historically played an important role (Cagé and Piketty, 2023), Le Pen’s party specifically denounces “tax injustice” regarding the middle classes—that “are often taxed more heavily than the most privileged”—and, notably, “small and medium-sized enterprises,” described as “the driving force behind the economy and job creation,” that would unjustifiably suffer as they “pay almost three times more tax on their profits than CAC 40 companies!” What this shows is that PRRPs’ mobilization of redistributive resentment comes in very different guises in different contexts, based on different forms of perceived injustice, along both bipartite and tripartite structures, and in relation to very different ingroups and outgroups.

Recognitory resentment

The second type of resentment that we theoretically expected to find in the discourse of PRRPs is recognitory resentment. In these statements, not material resources but the symbolic appreciation of group identities is key. Remarkably, though, the latter was solely present in our Dutch and Bulgarian data, and not in any documentation of the French National Rally, the Italian Lega, or the Polish Konfederacia. A closer look on the political documentation of PRRPs in these two countries reveals that recognitory resentment tends to be articulated through an opposition between “politically correct elites” on the one hand and the culturally deprived national population on the other. The former, as Wilders’ PVV put it, would “take away everything that belongs to our culture.” Even though his party operates in one of the most secularized countries in the world, Wilders thereby supports Christian traditions, by opposing the latter to the allegedly privileged treatment of Muslims (to be sure, without highlighting any religious defense of Christianism itself).

Everything shows that the politically-correct elite has taken sides against the Netherlands. […] Why are Christmas and Easter under fire, while we see entire TV broadcasts on Ramadan? It is the world upside down.

Illustrating Wilders’ peculiar preoccupation with Islam (Vossen, 2017; Damhuis, 2020), the scandalized preferential treatment of Muslims also figures in an aspect of Dutch culture that, according to the PVV’s political documents, would be even more severely under attack by “the elite” than Christmas and Easter, i.e., the tradition of Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) and Sinterklaas. In this case, too, the PVV accuses “the elite” of inversing priorities: “Why are they trying to kill the Sinterklaas tradition with Zwarte Piet, but halal slaughter is allowed to continue?” Wilders and his party thus tend to ignite recognitory resentment through a particular depiction of victimhood, according to which the “native people” are claimed to “lose their country,” their “culture” and their “identity,” because of “politically correct” elites, who would symbolically favor non-native outgroups to the detriment of the native population.

As with the Dutch PVV, the rhetoric of the Eastern European PRRPs we studied also propagates the preservation of national identity, notably in relation to minority groups. Yet, in line with our expectations, the recognitory resentment these parties mobilize has a more “traditional” character compared to the PVV’s discourse. For instance, the Bulgarian PRRP Vazrazhdane made repeatedly promoted “positive family models,” “traditional family values” and teaching youth the proper understanding of marriage, while being against “hedonism and genderism.” Contrary to our findings regarding the PVV, these statements particularly target the LGBTQ+ community; a tendency we also observed in the discourse of the Polish PRRP Konfederacia. For instance, when it stated that:

We will defend schools against the invasion of self-proclaimed “sex educators” and propagandists of the LGBT movement. We will ensure that children’s right to respect their sensitivity and not be exposed to indoctrination or contact with age-inappropriate content is duly respected. We will guarantee the right of parents to raise their children in accordance with their values. The school is supposed to support parents in the upbringing process, not compete with them.

Retributive resentment

Thus far, our findings are largely in line with our theoretical expectations. Yet, during the data analysis, one other main type of resentment showed up in the Dutch and French cases that we did not anticipate. This type can be described as retributive resentment and relates to one of the key features of the ideology of populist radical right parties: authoritarianism.20 Following Mudde (2007), p. 23, (see also Brewster Smith, 1967; Altemeyer, 1983), this notion can be defined as “the belief in a strictly ordered society, in which infringements of authority are to be punished severely.” Similar infringements of authority are particularly problematic, according to the PVV and RN, as perpetrators would receive a morally unjustifiable privileged treatment, while “ordinary citizens” would bear the brunt, due to overly lax judges and politicians. One thinks of Wilders’ PVV, who claimed that: “Our judiciary is riven with left-wing magistrates who consider the rights of offenders more important than the injustice done to victims.” Or of Le Pen’s RN, stating that: “All too rarely do victims benefit from the moral reparation that, in any civilized society, the punishment of the perpetrators of offenses constitutes.” Retributive resentment—occurring when the wellbeing and security of offenders are protected by some responsible outgroup, whereas ordinary citizens, portrayed as victims, get unfairly punished—thus bears resemblance to the concept of “penal populism” (Pratt, 2007), in the sense that the latter also “speaks to the way in which criminals and prisoners are thought to have been favored at the expense of crime victims in particular and the law-abiding public in general.” (Ibid., 12). That is, to use the language of the PVV, when “the scum” are “subsidized and cuddled” rather than being “caught and deported.”21 Similarly, as Le Pen’s party claimed in its 2012 electoral manifesto:

Far from tackling the root causes of the problem, since 2009 our governments have preferred to encourage impunity for certain offenders: sentences of less than two years’ imprisonment are now rarely carried out, and 80,000 sentences handed down have never been carried out. In the end, in France, only the victims are executed!

Discussion

In recent years, scholars have shown an increasing interest in the role of emotions to understand political behavior. Yet despite this “affective turn,” important gaps can still be found in the literature—even when it comes to the party family that is by far best studied by political scientists: the populist radical right (Mudde, 2016, p. 2). In particular, we know little about the role of affect in the political supply of these parties (Betz and Oswald, 2022). This article has therefore taken up the suggestion of Betz and Oswald (2022), p. 136 to explore how PRRPs “concretely appeal to emotions, what tropes and rhetorical devices they use to evoke and elicit an affective response among their target audience.” We thereby focus on the affect of “resentment,” which, despite being oft-cited in the literature as a crucial driver of PRRP support, remains rarely theorized, let aside operationalized and empirically analyzed in a systematic way.

Theoretically, we argue that resentment is rooted in what sociologists call (fraternalistic) relative deprivation (Runciman, 1966; Pettigrew, 2016) and consists of three key elements: (1) a situation of perceived injustice; (2) a feeling of hostility vis-à-vis the perceived wrongdoer(s); and (3) a desire for retaliation. Empirically, we used this conceptualization of resentment to analyze the political discourse of PRRPs in five different European countries. By doing so, we identified three types of resentment that were mobilized by PRRPs: redistributive resentment (concerning the allocation of material resources and socio-economic opportunities), recognitory resentment (revolving around the symbolic appreciation of group identities), and retributive resentment (concerning the treatment of perpetrators and victims). The first of these two types were largely in line with our theoretical expectations, including our anticipations regarding: the presence of welfare chauvinism and culturalized producerism in redistributive resentment statements; the absence of welfare chauvinism in the rhetoric of Eastern European PRRPs; as well as a stronger focus on traditional values in that context compared to Western Europe. However, we did not theoretically expect to find the third type of resentment—retributive resentment. The latter does resonate, though, with the existing notion of “penal populism” (Pratt, 2007), as well as previous studies pointing at the importance of authoritarianism and crime. Not only when it comes to radical right’s supply (Mudde, 2007), but also with regard to the political attitudes and preoccupations of PRRP voters (e.g., Hooghe et al., 2002; Dinas and van Spanje, 2011; Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Future studies could focus more directly on the role of retributive resentment to better understand the crime-related discourse of PRRPs as well as the “authoritarian” traits of their voters.22

In a similar vein, the first type of resentment we empirically observed (redistributive resentment) turned out to be mobilized in a more heterogeneous way than we theoretically anticipated. More specifically, we identified several subtypes of this form of resentment, which (unexpectedly) share a binary structure rather than a tripartite one. Accordingly, immigrants (“below”) are absent, and only elites (“above”) are present as targeted outgroup. In addition to this commonality, these subtypes of redistributive resentment revolve around highly different situations of perceived injustice, notably concerning place, class, foreign influence, and the costs of the ecological transition. While our observations regarding the first of these subtypes (place) add to the growing literature on so-called “regional” or “place-based resentment” (Cramer, 2016; Munis, 2020; De Lange et al., 2023, see also Guilluy, 2019), by showing how place-based resentment figures in the rhetoric of the radical right; our findings regarding climate-based resentment speak to recent research on “green deservingness” (Gengnagel and Zimmermann, 2022), as they indicate how PRRPs express anti-environmental stances in a resentful way, based on two deservingness criteria (cf. van Oorschot et al., 2017): identity, i.e., the native people are seen as more deserving (one thinks of the PVV’s opposition between “unworldly climate preachers” versus “our people’s pockets”); and need, i.e., natives with greater need are seen as more deserving (remember the PVV’s support for “hundreds of thousands of households [living] in energy poverty” who would “often literally sit on the couch shivering from the cold”). Future research could cross-sectionally study in which ways this specific form of redistributive resentment figures within the radical right’s opposition to climate mitigation policies (see, e.g., Hess and Renner, 2019), and how these statements resonate with the political preoccupations of PRRP voters (see, e.g., Mau et al., 2023). In addition, future studies could compare the other two subtypes of redistributive resentment, regarding class and foreign influence, with the ways in which populist radical left-wing parties mobilize resentment. Not only because class and foreign political influence also tend to figure in the discourse of parties on the radical left. But also since the political rhetoric of the latter tends to be structured in a bipartite rather than tripartite way (Judis, 2016, p. 12), just as we observed in these subtypes of redistributive resentment.

On a more general level, the heterogeneity of (sub)types of resentment we identified—relating to different issue domains and variegated situations of perceived injustice—resonates with the observation that the electorates of PRRPs are not monolithic but also have a heterogeneous character, consisting of voters with different social backgrounds, preoccupations, and position-takings (see, e.g., Ivarsflaten, 2005; Mudde, 2007; Damhuis, 2020). In that respect, our findings are congruent with Roger Eatwell’s idea that, rather than offering standardized “products” to a general electorate, PRRPs tend to use forms of “product differentiation” in order to appeal to different groups of voters (Eatwell, 2000, p. 361).

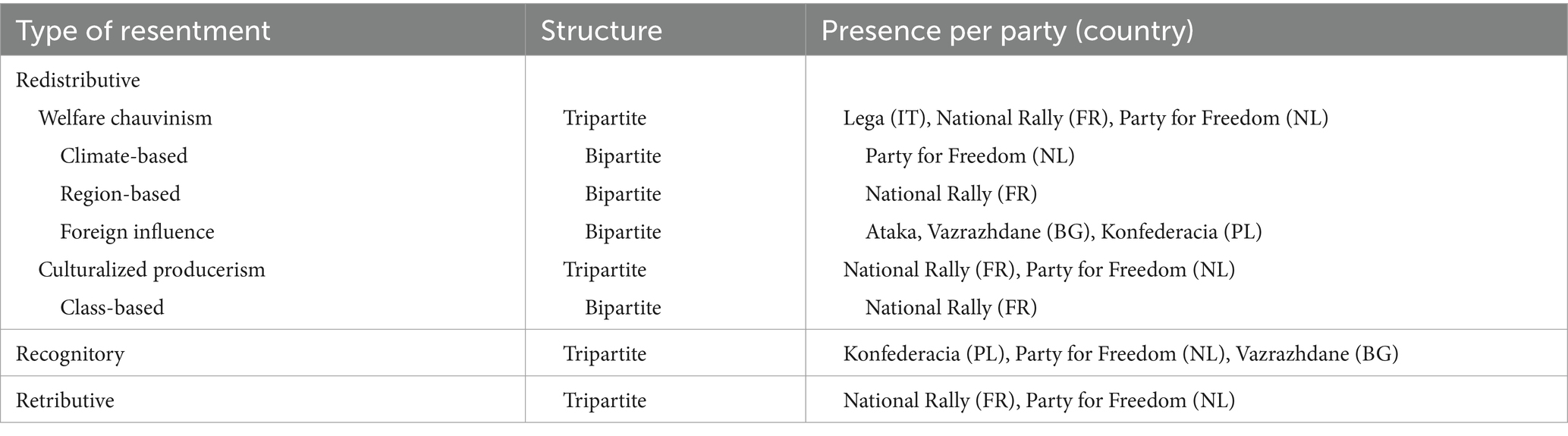

At the same time, as Table 1 shows, we did not observe all the different (sub)types of resentment in all the five selected countries. In addition to contextual differences, we believe this may have to do with the data we used. On the positive side: our empirical sources (mainly party manifesto’s) have advantages in terms of cross-case analysis—especially when covering a longer period of time, as we do here. Yet, their content is also likely to be less “confrontational” compared to political statements expressed via media such as newspapers (e.g., Kriesi et al., 2008) or Tweets (e.g., Damhuis, 2020). Since “hostility vis-à-vis perceived wrongdoers” constitutes a central element in our conceptualization of resentment, statements containing the latter may thus be more frequently observable in other data sources, notably Tweets. For exactly that reason, we considered using Twitter/X messages. However, it turned out that, in addition to temporal limitations (after all, Twitter/X is a relatively recently used medium by political leaders and organizations), there are hardly any Tweets posted by the Bulgarian radical right, thus impeding systematic cross-case analyses in the countries we selected. Consequently, for future research, we suggest using different types of data, including Tweets, to assess the extent to which our exploratory findings can travel, and to further tease out different mobilizations of resentment by PRRPs in different contexts.

Table 1. Overview of different types of resentment mobilized by radical right parties in five countries.

On a final note, it should be stressed that the different forms of resentment mobilized by the radical right—despite the heterogeneity we observed—do share a common core. Specifically, non-deserving outgroups are unfairly privileged, by some wrongdoer, to the detriment of a virtuous ingroup. Moreover, pertaining to all the three main forms of resentment we distinguished, the underlying situations of injustice are not so such framed in an ideological way (e.g., through oppositions between “progressive cosmopolitans” versus “conservative nationalists”). Instead, they are more commonly portrayed as “insidious inversions of commonsensical priorities” (Pratt, 2007, p. 12). Regarding these priorities in the realm of redistributive resentment, one thinks of Le Pen’s RN “elementary rule” of “putting our own before others.” When it comes to recognitory resentment, the inversion of similar priorities was exemplified by Wilders’ denouncement that political elites, while banning the religious traditions of the historical majority group (“Why are Christmas and Easter under fire…”), would support the religious activities of a minority group of newcomers (“…while we see entire TV broadcasts on Ramadan?”). And regarding retributive resentment, the inversion of commonsensical priorities was illustrated by the RN’s claim that “in France, only the victims are executed!” Recent studies indicate that similar commonsensical prioritizations—and the perceived provocation thereof—are crucial to understand the political reasoning of ordinary citizens, in which moral intuitions and affectively charged group distinctions, taken from the domain of everyday life, loom particularly large (one thinks of “hard-working,” “lazy-bones,” “do-gooders,” “rule breakers,” etc.; see, e.g., Bornschier et al., 2021; Mau et al., 2023; Damhuis and Westheuser, 2024; Zollinger, 2024). Accordingly, future research could focus more closely on the different mobilizations of resentment we identified, and the corresponding “inversions of commonsensical priorities” they entail, to develop a better understanding of the electoral appeal of PRRPs.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

KD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ER: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the focus area ‘Migration and Societal Change’ of Utrecht University as part of a Special Interest Group on “The rise of the radical right in Europe: An interdisciplinary approach”. The publication costs of this article were covered by the focus area.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support provided by the focus area ‘Migration and Societal Change’ of Utrecht University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Illustratively, these parties have been described by Rosanvallon (2021), p. 53 as “entrepreneurs of resentment.”

2. ^This distinction overlaps with TenHouten’s (2018) opposition between “helpless” resentment and “forceful” resentment.

3. ^Accordingly, the Nietzschean (and Schelerian) view on ressentiment, carrying connotations of “lasting bitterness” (Banning, 2006, p. 73), is intimately related to the etymological origin of the term, as it derives from the French verb ressentir (to re-feel). As Scheler (1961), p. 2 put it: “ressentiment is the repeated experiencing and reliving of a particular emotional response reaction against someone else. The continual reliving of the emotion sinks it more deeply into the center of the personality, but concomitantly removes it from the person’s zone of action and expression.”

4. ^For Smith (1759), as Fassin (2013) put it, resentment represents “a passion, which can be a legitimate response to a wrong committed against the person and lead to a fair punishment of the perpetrator.”

5. ^As Hume (1986), summarized by Baier (1980), p. 138, cited in TenHouten (2018), p. 54 already argued: “Resentment is not simply anger, it is the form anger takes when it is provoked by what is seen as a wrong.”

6. ^This is conceptualization in line with one of the rare (and rather loose) definitions of ‘the politics of resentment’ that can be found in the literature: according to Wells and Watson (2005), p. 262, the latter “answers the classic question of politics, “who gets what and why” with “they get everything because we get nothing.”’

7. ^More specifically, following Runciman (1966), p. 33–34, (see also Vanneman and Pettigrew, 1972), a distinction can be made between egoistic and fraternalistic deprivation. The former pertains to a perception of deprivation arising from individual comparisons with other members of one’s ingroup, while the latter is founded on comparisons between one’s ingroup and other (out)groups. Political parties and leaders advocating or opposing structural societal changes are instigated by fraternalistic deprivation, as their rhetoric revolves around the relative standing of groups within society. Accordingly, we focus exclusively on fraternalistic deprivation.

8. ^Along very similar lines, Rostbøll (2023) notes that: “Resentment is based on the feeling that one is regarded and treated wrongly by other people, and it is an incipient demand to be regarded and treated differently.”

9. ^On a more conceptual level, taking a Weberian closure-perspective, this difference between bipartite and tripartite structures can be understood as a difference between “usurpationary” and “dual closure” (see Parkin, 1979; Damhuis, 2020).

10. ^Several studies indicate that these different structures, i.e., bipartite versus tripartite, also apply to the demand side (e.g., Schwartz, 2009; Burgoon et al., 2019; as to the radical right, see, e.g., Flecker, 2007). Similarly, Fukuyama (2018) stated that: “The resentful citizens fearing loss of middle-class status point an accusatory finger upward to the elites, to whom they are invisible, but also downward toward the poor, whom they feel are undeserving and being unfairly favored.” Similarly, Wells and Watson (2005), p. 261 noted that: “They [London shopkeepers] resent local and national government for what they perceive as the unfair distribution of [political and economic] resources, both to “asylum-seekers” below them and to corporate capital above them.”

11. ^To a certain extent, these two dimensions relate to the literature on spatial, or “place-based” resentment (Cramer, 2016; Munis, 2020; De Lange et al., 2023). Place-based resentment has been defined by Munis (2020), p. 1057 as “hostility toward place-based outgroups perceived as enjoying undeserved benefits beyond those enjoyed by one’s place-based ingroup”. Despite different spatial foci—e.g., Cramer (2016) centering on “rural resentment” and De Lange et al. (2023) on “regional resentment”—these studies point at three similar dimensions of perceived unfairness on which resentment is based: a cultural dimension (being looked down upon, qua values and lifestyles, by an outgroup), an economic dimension (not getting one’s fair share of resources), and a representational dimension (being ignored by decision-makers). Although the cultural dimension does not correspond to our conceptualization of resentment, the economic dimension overlaps with what we describe as redistributive resentment, whereas the representational dimension bears resemblance to what we term recognitory resentment.

12. ^To be sure, this dimension of redistributive resentment also applies to the radical left, where it is typically formulated in terms of class-based struggle, rooted in the frustration among members of lower classes regarding higher classes’ privileges and their responsibility for the injustice and exploitation under which one’s own class is suffering (Marshall, 1973; TenHouten, 2018).

13. ^Along similar lines, Banikowski (2017), p. S202 speaks of “resentment toward those who are seen as receiving higher levels of government assistance, or greater incomes for ostensibly less work.”

14. ^In that light, Norris and Inglehart (2019), p. 46, speak of “resentment against ‘political correctness.’”

15. ^Interestingly, the latter are not only refugees and migrants with non-European background, but as Chueri (2023) shows, there is an increasing support within PRRPs for restriction on intra-EU migrants’ access to the welfare state.

16. ^Similarly to Bustikova (2014), who observes a link between minority advancement and far-right voters, Hlatky (2021) finds that EU Regional Policy, which is partially used to politically and economically accommodate minorities, is related to increased vote for Eurosceptic parties. He argues that “voters choose Eurosceptic electoral options when they possess sufficient grievances with minority groups” (Hlatky, 2021, p. 349).

17. ^For clarity’s sake—and following the title of this paper—we thus do not focus empirically on resentment as such, but on the mobilization of resentment (i.e., on the politics of resentment), whereby, in the terms of Betz and Oswald (2022), political parties use different rhetorical devices to evoke and elicit an affective response among target audiences.

18. ^In Bulgaria, the first and most active radical right party was Ataka (Attack). Established in 2005, it had a strong presence in the national parliament (7–9%) between 2005 and 2013. After 2014, the party started losing support and has collected less than half percentage of the vote in the last several elections. The loss of Ataka opened the Bulgarian radical right political space for other players, the most prominent of which has been Vazrazhdane (Revival, VZ).

19. ^Similarly, the Bulgarian party Ataka claimed that: “We are fourth in Europe in terms of gold deposits, but today the profit from gold mining flows out. Ataka wants the return of all these resources into Bulgarian hands.”

20. ^According to Mudde (2007), the other two key ingredients are populism and (most importantly) nativism.

21. ^Resonating with Weber’s (1978), p. 46 observation that different motives for the closure of relationships between social groups are usually combined (see also Steinert, 2004; Bartolini, 2005), retributive resentment is sometimes linked directly by the PVV, to the morally unfair socio-economic circumstances of virtuous, yet deprived native groups: “Compared to prisoners, the elderly, chronically ill and disabled have no rights in our healthcare institutions. This is an eyesore for us. Criminals in prisons have a right to leisure, to airing, to TV, to smoking in the room, free clothes and you name it. The PVV wants the elderly and disabled in care institutions to be given far more rights and, on the contrary, prisoners to have rights taken away.”

22. ^For insightful critiques of “working-class authoritarianism” (Lipset, 1959), a concept that has influenced numerous studies in this field, see Hamilton (1972), Chapter 11 and Ehrenreich (1989), Chapter 3.

23. ^A document entitled “Motion for Vote of Non-Confidence in the Health Minister” dated 2022, which is available on the party’s website, was also examined, but no resentment-related statements were found there.

References

Abts, K., and Baute, S. (2022). Social resentment, blame attribution and Euroscepticism: the role of status insecurity, relative deprivation and powerlessness. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 35, 39–64. doi: 10.1080/13511610.2021.1964350

Abts, K., Dalle Mulle, E., van Kessel, S., and Michel, E. (2021). The welfare agenda of the populist radical right in Western Europe: combining welfare chauvinism, producerism and populism. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 27, 21–40. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12428

Andersen, J. G., and Bjørklund, T. (1990). Structural changes and new cleavages: the progress parties in Denmark and Norway. Acta Sociol. 33, 195–217. doi: 10.1177/000169939003300303

Banikowski, B. (2017). Ethno-nationalist populism and the mobilization of collective, resentment. Br. J. Sociol. 68, S181–S213. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12325

Barbalet, J. M. (1992). A macro sociology of emotions: class resentment. Sociol. Theory 10, 150–163. doi: 10.2307/201956

Barbalet, J. M. (1998). Emotion, social theory, and social structure: a macrosociological approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bartolini, S. (2005). La formation des clivages. Rev. Int. Polit. Comp. 12, 9–34. doi: 10.3917/ripc.121.0009

Bernhard, L., and Kriesi, H. (2019). Populism in election times: a comparative analysis of 11 countries in Western Europe. West Eur. Polit. 42, 1188–1208. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2019.1596694

Betz, H.-G. (2002). “Conditions favouring the success and failure of radical right-wing populist parties in contemporary democracies” in Democracies and the populist challenge. eds. Y. Mény and Y. Surel (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan), 197–212.

Betz, H. G. (2017). Nativism across time and space. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 23, 335–353. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12260

Betz, H.-G. (Ed.) (2021). We are not worthless: resentment, misrecognition and populist mobilization. Oslo: Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right Available at: https://www.radicalrightanalysis.com/2021/07/13/we-are-not-worthless-resentment-misrecognition-and-populist-mobilization/

Betz, H.-G., and Oswald, M. (2022). “Emotional mobilization: the affective underpinnings of right-wing populist party support” in The Palgrave handbook of populism. ed. M. Oswald (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 115–144.

Bobbio, N. (1996). Left and right: the significance of a political distinction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bornschier, S., Häusermann, S., Zollinger, D., and Colombo, C. (2021). How ‘us’ and ‘them’ relates to voting behavior—social structure, social identities, and electoral choice. Comp. Pol. Stud. 54, 2087–2122. doi: 10.1177/0010414021997504

Bressanelli, E., and de Candia, M. (2023). Fratelli d’Italia in the European Parliament: between radicalism and conservatism. Contemp. Ital. Polit., 1–20. doi: 10.1080/23248823.2023.2285545

Brewster Smith, M. (1967). “Foreword” in Dimenions of authoritarianism: a review of research and theory. eds. J. P. Kirscht and R. C. Dillehay (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press), v–ix.

Burgoon, B. S., van Noort, S., Rooduijn, M., and Underhill, G. (2019). Positional deprivation and support for radical right and radical left parties. Econ. Policy 34, 49–93. doi: 10.1093/epolic/eiy017

Bustikova, L. (2014). Revenge of the radical right. Comp. Pol. Stud. 47, 1738–1765. doi: 10.1177/0010414013516069

Cagé, J., and Piketty, T. (2023). Une histoire du conflit politique. Elections et inégalités sociales en France, 1789–2022. Paris: Seuil.

Capelos, T., and Demertzis, N. (2018). Political action and resentful affectivity in critical times. Humanit. Soc. 42, 410–433. doi: 10.1177/0160597618802517

Capelos, T., and Katsanidou, A. (2018). Reactionary politics: explaining the psychological roots of anti preferences in European integration and immigration debates. Polit. Psychol. 39, 1271–1288. doi: 10.1111/pops.12540

Carter, E. (2005). The extreme right in western europe: success or failure? Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Chueri, J. (2023). What distinguishes radical right welfare chauvinism? Excluding different migrant groups from the welfare state. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 33, 84–100. doi: 10.1177/09589287221128441

Cinpoeş, R., and Norocel, O. C. (2020). “Nostalgic nationalism, welfare chauvinism, and migration anxieties in Central and Eastern Europe” in Nostalgia and hope: intersections between politics of culture, welfare, and migration in Europe. eds. O. C. Norocel, A. Hellström, and M. B. Jørgensen (Cham: Springer), 51–65.

Clough, P., and Halley, J. (2007). The affective turn: theorising the social. Durham: Duke University Press.

Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Damhuis, K. (2019). Why Dutch populists are exceptional. A ‘Muslims in the West’ reaction essay. Washington: Brookings Institution Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-dutch-populists-are-exceptional/

Damhuis, K. (2020). Roads to the radical right. Understanding different forms of electoral support for radical right-wing parties in France and the Netherlands. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Damhuis, K., and Westheuser, L. (2024). Cleavage politics in ordinary reasoning: how common sense divides. Eur. Soc., 1–37. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2023.2300641

de Koster, W., Achterberg, P., and van der Waal, J. (2013). The new right and the welfare state: on the electoral relevance of welfare chauvinism and welfare populism in the Netherlands. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 34, 3–20. doi: 10.1177/0192512112455443

De Lange, S., van der Brug, W., and Harteveld, E. (2023). Regional resentment in the Netherlands: a rural or peripheral phenomenon? Reg. Stud. 57, 403–415. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2022.2084527

Decker, F. (2008). “Germany: right-wing populist failures and left-wing successes” in Twenty-first century populism: the spectre of Western European democracy. eds. D. Albertazzi and D. McDonnell (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan).

Demertzis, N. (2006). “Emotions and populism” in Emotions, politics and society. eds. S. Clarke, P. Hoggett, and S. Thompson (Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan), 103–122.

Demertzis, N. (2013). Emotions in politics. The affect dimension in political tension. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Dinas, E., and van Spanje, J. (2011). Crime story: the role of crime and immigration in the anti-immigration vote. Elect. Stud. 4, 658–671.

Eatwell, R. (2000). “Ethnocentric party mobilization in Europe: the importance of the three-dimensional approach” in Challenging immigration and ethnic relations politics. eds. R. Koopmans and P. Statham (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Ennser-Jedenastik, L. (2016). A welfare state for whom? A Group-based account of the Austrian freedom party’s social policy profile. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 22, 409–427. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12218

Eurostat (2020): European Commission (2023). Social protection statistics - overview. Eurostat. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Social_protection_statistics_-_overview&oldid=637670 (Accessed August 30, 2023).

Fanoulis, E., and Guerra, S. (2017). Anger and protest: referenda and opposition to the EU in Greece and the United Kingdom. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 30, 305–324. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2018.1431766

Fassin, D. (2013). On resentment and ressentiment: the politics and ethics of moral emotions. Curr. Anthropol. 54, 249–267. doi: 10.1086/670390

Flecker, J. (Ed.) (2007). Changing working life and the appeal of the extreme right. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Fraser, N., and Honneth, A. (2003). Redistribution or recognition? A political-philosophical exchange. London: Verso.

Fukuyama, F. (2018). Identity: the demand for dignity and the politics of resentment. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Gengnagel, V., and Zimmermann, K. (2022). Green deservingness, green distinction, green democracy? Towards a political sociology of a contested eco-social consensus. Cult. Pract. Europeanizat. 7, 292–303. doi: 10.5771/2566-7742-2022-2-292

Gidron, N., and Hall, P. (2017). The politics of social status: economic and cultural roots of the populist right. Br. J. Sociol. 68, S57–S84. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12319

Goodwin, J., Jasper, J. M., and Polletta, F. (Eds.) (2001). Passionate politics: emotions and social movements. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Grandjean, A., and Guénard, F. (2012). “Introduction: Logiques du ressentiment” in Le ressentiment, passion sociale. eds. A. Grandjean and F. Guénard (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes), 11–17.

Grant, P. R. (2008). The protest intentions of skilled immigrants with credentialing problems: a test of a model integrating relative deprivation theory with social identity theory. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 687–705. doi: 10.1348/014466607X269829

Guilluy, C. (2019). Twilight of the elites. prosperity, periphery, and the future of France. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hess, D., and Renner, M. (2019). Conservative political parties and energy transitions in Europe: opposition to climate mitigation policies. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 104, 419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2019.01.019

Hlatky, R. (2021). EU funding and Euroskeptic vote choice. Polit. Res. Q. 74, 348–363. doi: 10.1177/1065912920904996

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., and Wilson, C. (2002). Does left/right structure party positions on European integration? Comp. Pol. Stud. 35, 965–989. doi: 10.1177/001041402236310

Hume, D. (1986) in Enquiries concerning the human understanding and concerning the principles of morals. ed. L. A. Selby Bigge. 3rd ed (Oxford: Clarendon).

Ivaldi, G., and Mazzoleni, O. (2019). Economic populism and producerism: European right-wing populist parties in a transatlantic perspective. Populism 2, 1–28. doi: 10.1163/25888072-02011022

Ivarsflaten, E. (2005). The vulnerable populist right parties: no economic realignment fuelling their electoral success. Eur J Polit Res 44, 465–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00235.x

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., and Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfs038

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., and Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Judis, J. B. (2016). The populist explosion: how the great recession transformed American and European politics. New York: Columbia Global Reports.

Kitschelt, H., and McGann, A. J. (1995). The radical right in Western Europe: a comparative analysis. Ann Arbour, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Kitschelt, H. (2007). Growth and persistence of the radical right in postindustrial democracies: advances and challenges in comparative research. West Eur. Polit. 30, 1176–1206. doi: 10.1080/01402380701617563

Knops, L., and Petit, G. (2022). Indignation as affective transformation: an affect-theoretical approach to the Belgian yellow vest movement. Mobilizat. Int. Q. 27, 169–192. doi: 10.17813/1086-671X-27-2-169

Knudsen, B. T., and Stage, C. (2015). Affective methodologies: developing cultural research strategies for the study of affect. London, UK: Palgrave McMillan.

Kochuyt, T., and Abts, K. (2017). Ongehoord populisme: gesprekken met Vlaams Belangkiezers over stad, migranten, welvaartsstaat, integratie en politiek. Brussels: ASP.

Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., and Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lamont, M., Yun Park, B., and Ayala-Hurtado, E. (2017). Trump’s electoral speeches and his appeal to the American white working class. Br. J. Sociol. 68, 153–180. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12315

Lefkofridi, Z., and Michel, E. (2017). “The electoral politics of solidarity: the welfare agendas of radical right” in The strains of commitment: the political sources of solidarity in diverse societies. eds. K. Banting and W. Kimlycka (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Democracy and working-class authoritarianism. Am. Sociol. Rev. 24, 482–501. doi: 10.2307/2089536

Marcinkiewicz, K., and Dassonneville, R. (2022). Do religious voters support populist radical right parties? Opposite effects in Western and East-Central Europe. Party Polit. 28, 444–456. doi: 10.1177/1354068820985187

Marcus, G. E. (2002). The sentimental citizen: emotion in democratic politics. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Marshall, T. H. (1973). “The nature of class conflict” in Class, citizenship and social development: Essays 164–73. ed. T. H. Marshall (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press).

Mau, S., Westheuser, L., and Lux, T. (2023). Triggerpunkte: Konsens und Konflikt in der Gegenwartsgesellschaft. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

Mepschen, P., Duyvendak, J. W., and Tonkens, E. H. (2010). Sexual politics, orientalism and multicultural citizenship in the Netherlands. Sociology 44, 962–979. doi: 10.1177/0038038510375740

Meret, S. (2019). Islam and the Danish-scandinavian welfare state. A ‘Muslims in the West’ reaction essay. Washington: Brookings Institution Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/islam-and-the-danish-scandinavian-welfare-state/

Miceli, M., and Castelfranchi, C. (2017). Anger and its cousins. Emot. Rev. 11, 13–26. doi: 10.1177/1754073917714870

Mudde, C., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2017). Populism: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C., and Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2013). Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Gov. Oppos. 48, 147–174. doi: 10.1017/gov.2012.11

Munis, B. K. (2020). Us over here versus them over there… literally: measuring place resentment in American politics. Polit. Behav. 44, 1057–1078. doi: 10.1007/s11109-020-09641-2

Nord, P. (1986). Paris shopkeepers and the politics of resentment. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: trump, brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2013). Politcal emotions. Why love matters for justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Otjes, S., Ivaldi, G., Ravik Jupskås, A., and Mazzoleni, O. (2018). It's not economic interventionism, stupid! Reassessing the political economy of radical right-wing populist parties. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev. 24, 270–290. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12302

Oudenampsen, M. (2018a) The return of ressentiment. In Sjoerd Tuinen van (ed.) The polemics of ressentiment. Variations on Nietzsche. New York: Bloomsbury.

Parkin, F. (1979). Marxism and class theory: a bourgeois critique. New York: Columbia University Press.

Pettigrew, T. F. (2016). In pursuit of three theories: authoritarianism, relative deprivation, and intergroup contact. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033327

Rashkova, E. R. (2021). Gender politics and radical right parties: an examination of Women’s substantive representation in Slovakia. East Eur. Polit. Soc. 35, 69–88. doi: 10.1177/0888325419897993

Rashkova, E. R., and Zankina, E. (2017). Are (populist) radical right parties Männerparteien? Evidence from Bulgaria. West Eur. Polit. 40, 848–868. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2017.1285580

Rathgeb, P. (2020). Makers against takers: the socio-economic ideology and policy of the Austrian freedom party. West Eur. Polit. 44, 635–660. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2020.1720400

Rostbøll, C. F. (2023). “Recognition and the politics of resentment” in Democratic respect populism, resentment, and the struggle for recognition. ed. C. F. Rostbøll (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 22–48.

Runciman, W. (1966). Relative deprivation and social justice: a study of attitudes to social inequality in twentieth century England. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rydgren, J. (2005). Is extreme right-wing populism contagious? Explaining the emergence of a new party family. Eur J Polit Res 44, 413–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2005.00233.x

Rydgren, J. (2008). Immigration sceptics, xenophobes or racists? Radical right-wing voting in six west European countries. Eur J Polit Res 47, 737–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00784.x

Schreier, M. (2019). “Content analysis, qualitative” in Sage research methods foundations. ed. P. Atkinson (London: SAGE Publications Ltd.).

Schumacher, G., and van Kersbergen, K. (2016). Do mainstream parties adapt to the welfare chauvinism of populist parties? Party Polit. 22, 300–312. doi: 10.1177/1354068814549345

Schwartz, O. (2009) Vivons-nous encore dans une société de classes? La vie des idées. Available at: https://laviedesidees.fr/Vivons-nous-encore-dans-une.html