Abstract

This paper introduces an unsupervised framework that illustrates how insights gathered from opinion surveys regarding the functionality of democracy can be connected to social media messages of politicians on an international scale. By concentrating on the influence of social media messages from elected officials, the study adopts a “top-down” theoretical approach that links citizens’ attitudes towards democracy with the viewpoints about democracy expressed by politicians within social media discourses. Using a word embedding classification strategy, democracy-related themes are extracted from politicians’ messages. The research is conducted across 11 European countries, namely, Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Switzerland is also included in the study because of its direct democracy system. The 10th round of the European Social Survey serves as the basis for assessing citizens’ democratic attitudes. The study encompasses two main analytical segments. First, aggregated analyses conducted at the country level reveal the degree of alignment between prominent democracy-related themes present in politicians’ discourse and citizens’ perceived significance of these same themes. Second, individual-level connections between social media data and survey respondents are established through their preferred political party (or orientation). Variable importance analysis is subsequently applied to explore which democracy-related themes conveyed by politicians hold significance in predicting public contentment with democracy.

1 Introduction

Studies have found that public support for democratic principles is declining in established democracies (Inglehart, 2003; Wike and Schumacher, 2020; Wike and Fetterolf, 2021). The term “democratic backsliding” has been increasingly used to describe an overall deterioration of democratic rights and institutions (IDEA, 2018), and its effects on satisfaction with democracy (SWD) have been documented in many parts of the world (IDEA, 2020). In this context, survey research has had difficulties in capturing the complexities and public discourses that contribute to individuals’ satisfaction or motivation. Recent surveys inform us that citizens think that democracy is not delivering enough, do not always demonstrate a strong commitment to democracy, identify political and social divisions as major challenges, and want a more direct public voice (Wike and Schumacher, 2020). However, we still know little about which of the contested values and principles are most likely to be related to public (dis)satisfaction with democracy.

The present study aims to contribute to filling this gap by improving our understanding of what aspects of democracy act as salient factors in citizens’ SWD when citizens are exposed to political messages. Drawing from public opinion survey data and social media content, the study investigates how surveyed opinions about the workings of democracy might relate to politicians’ social media messages.

From a conceptual perspective, this study focuses on the importance of political discourses on citizens’ SWD. It adopts a top-down view of opinion formation by considering that certain democratic views and understandings are made more salient in the public debate by political actors’ discourse. In summary, the goal is to investigate which of these views contribute to public SWD.

It has been shown that political elites and the (new) media constitute essential sources of information (Schroeder, 2018), which likely influence citizens’ political perceptions. Our theoretical background suggests that the social media discourse from elected representatives can serve as a reliable source to uncover the democracy dimensions that are publicly discussed and contested in each country. This perspective is consistent with Zaller’s (1992). The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion, which indicates that the most politically aware citizens follow increasingly divided elites along ideological lines, leading to higher polarization. In line with the proposition that elites’ partisan ties serve as important cues in the public’s filtering of political discourse (Zaller, 1992) and act as “opinion leaders” (Katz and Lazarsfeld, 1955), we link elite discourses with citizen attitudes. This approach enables us to measure the political discourse on the meanings of democracies and to assess how these discourses resonate with citizens’ attitudes towards democracy.

To combine survey and social media data, we further combine the top-down approach with the concept of selective attention, suggesting that citizens are more likely to be receptive to (social) media content that is in line with their political preference (Wüest, 2018). More specifically, our study further focuses on opportunities from political information from social media. In today’s digital media landscape, there are important interrelations between the political and media spheres (McGregor, 2019), notably because what politicians say on social media is likely to trigger media attention. Furthermore, social media content has been shown to be influential in public agenda setting (Gilardi et al., 2022) by determining the problems that individuals should give attention to. The top-down approach can, in this view, be extended to the realm of social media discourse (Feezell, 2018). Our study assesses the extent to which the elite discourse related to democracy that is available on social media relates to public (dis)satisfaction with the workings of democracy.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Understandings of public SWD

Measuring attitudes and assessments regarding democratic legitimacy is a central aspect of the literature devoted to measuring public opinion in relation to democracy (Inglehart and Welzel, 2005). Survey research has exhaustively documented the bases for (dis)contentment with democracy, revealing public opinion about the workings of democracy. For instance, open-ended survey questions have shown that people mostly define the meaning of democracy in terms of political freedoms, civil liberties, and rights rather than institutional and procedural or socioeconomic features (Dalton et al., 2007; Shin, 2017). Furthermore, open-ended survey questions conducted in the United Kingdom and in Australia inform us that citizens mostly define democracy in terms of freedom and human rights, elections and procedures, as well as having a voice in government (Wike and Fetterolf, 2021).

Closed-ended survey questions further show that opinions on how well democracy is working relate to whether people believe their most fundamental rights are being respected (Wike et al., 2021). Furthermore, the extent to which citizens consider their political elites and institutions corrupt has been consistently found to exert a strong effect on both their trust in institutions and, thereby, their evaluation of the workings of democracy (Maciel and de Sousa, 2018; Mauk, 2021).

Despite these findings, it is often difficult to clearly assess the causes of variations in satisfaction with democracy (Ariely, 2014), as well as what representations of democracy are salient in public opinion (Dahlberg et al., 2020). The literature has also revealed significant cross-cultural variations in the understanding and expectations towards democracy (O'Donnell, 2007; Ariely and Davidov, 2011). Overall, democracy remains an “essentially contested concept” (Ariely, 2014, p. 624) whose meaning can vary greatly in diverse cultural settings.

In addition, the use of a single measure of support for democratic performance holds important weaknesses, specifically because citizens’ views of democracy impact the way this question is answered (see some critics of using a single measure: Norris, 1999; Canache et al., 2001; Schaffer, 2014; Ferrin, 2016). For instance, the SWD item (i.e., “How far are you satisfied with the way democracy is working in your country?”) is one of the most frequently used indicators in public opinion research. This single-item measure is used in the European Social Survey (ESS) and the World Values Survey (WVS) with slightly different phrasing (“On the whole, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in the [country]” and “How satisfied are you with the way democracy is developing in our country,” respectively) and answer options (10-point scale and 4-point scale, respectively). Nevertheless, Quaranta (2017) showed that the comparison of an index based on several items related to democracy evaluation and the single item SWD provides a reliable convergence across the measures at the country level and presents similar findings when used at the individual level.

To improve cross-country comparisons, sets of indicators have been developed to measure which aspects of democracy are supported and contested by citizens. A summary of the prominent dimensions for measuring citizens’ understanding and evaluation of the workings of democracy can be found in the ESS documentations for rounds 6 (Kriesi et al., 2013) and 10 of the survey (Ferrin, 2018). Overall, six dimensions aim to capture different components of democracy: electoral, liberal, social, direct democracy, inclusiveness, and type of representation dimensions. The development of these sets of indicators enables researchers to better understand what citizens want democracy to be and what adaptations are needed.

2.2 Political discourse and public opinion

The use of other data sources (e.g., social media content, comments from online news portals) might help to obtain more precise indicators of citizens’ democracy concerns. For instance, Dahlberg et al. (2020) showed that investigating democracy dimensions can be usefully applied for extracting relevant understandings from news and social online sources and, thereby, for analysing how the concept of democracy is used in its “natural habitat.” Reveilhac and Morselli (2022) have also shown the potential of relying on complementary text classification methods to classify democracy frames along the survey dimensions from the ESS.

Political discussion constitutes a core component of democratic life that is consequential for public assessments of the workings of democracy, as political discourse is heavily contextually and culturally loaded. Previous research has demonstrated that political elites’ views correlate with citizens’ broader attitudes. For instance, early expectations regarding the influence of political discourse on citizen opinions have been extensively discussed in the context of foreign policy, especially by Zaller (1992), who explains that elite discourse is the key to explaining support for war. We follow a similar top-down approach suggesting that political discourse is closely related to and, under some circumstances, might affect citizens’ attitudes towards policy issues in general and towards the working of democracy.

Zaller’s (1992) classic models of opinion formation underline the importance of opinion leaders on public opinion (Katz and Lazarsfeld, 1955), describing the role of opinion leaders in the filtering of political information on traditional media. Zaller has argued that, in the context of a democratic system, opinion leaders play a key role in informing citizens about policy issues and democratic questions. By emphasizing the importance and specific aspects of democratic life, opinion leaders can inspire individuals to change their views based on the messages they receive.

This top-down approach to public opinion is thus well suited to examine the relationship between political discourse and public understandings of democracy. In general, political discourses are an important part of a country’s political climate (Flores, 2018), which might be related to people’s understanding of reality (Careja, 2016). Evaluations of the role of political elites in shaping attitudes towards societal issues have been conducted on different topics. For instance, Czymara (2020), relying on opinion survey data and party manifesto data, has investigated how political elites can play a key role in fostering or impeding immigrant integration by shaping public opinion. The impact of elite discourse on citizens’ attitudes has also been investigated in other policy domains, such as trade agreements (Dür and Schlipphak, 2021), gender equality (Jones and Brewer, 2020) and European policy (Kortenska et al., 2020).

2.3 Exposition to social media political messages

The perspective of political elites’ discussions and views can act as drivers of the public evaluation of democracy (Dalton et al., 2007; Norris, 2017) also makes sense when extended to the realm of social media political discourses. Indeed, users who are highly active and vocal on social media tend to form an elite network, particularly in the case of Twitter (Blank and Lutz, 2017), which can influence opinions circulating online but also affect their dissemination in public opinion offline. For instance, political users can gain access to exposure on traditional media by voicing their positions and interests on social media (Dubois and Gaffney, 2014), thereby indirectly affecting public knowledge about policy issues. Social media content is indeed increasingly reported in news media by journalists (McGregor, 2019), facilitating the diffusion of the political content discussed on these platforms even to citizens who are not active on social media. In addition, Newman et al. (2017) demonstrated that up to 42% of the European population follows at least one politician on social media.

Social media provides new opportunities for political communication by allowing a closer interaction between the public and political elite (Ceron and Memoli, 2016; Newman et al., 2017). In particular, voices that contest prevalent democratic principles can reach a wide audience via social media platforms (Hameleers, 2018). Most notably, the challenge to moral principles and institutional arrangements in stable democracies has been associated with the rise of populist ideas (Rooduijn et al., 2014; Norris and Inglehart, 2016; Norris, 2017).

Therefore, in addition to the top-down approach, our study draws from the observation that citizens can endorse selective attention to political content. For instance, Wüest (2018) demonstrated that citizens’ attention to given policy issues and their related subtopics is partly correlated with respondents’ media consumption preferences. This suggests that citizens might give different amounts of attention based on the accessibility (or resonance) of political information based on shortcuts and affinities.

With respect to political discourse, it can be expected that when faced with complex policy issues, citizens are more receptive to messages from their preferred politicians (or politicians with whom they share a similar ideology) to reach informed preferences (McDermott, 2005). Citizens might thus be more likely to incorporate political information that is congruent with their existing political orientations into their own views (Steppat et al., 2022). This is also in line with the extensive literature on the role of social media in promoting polarized discourse (see review by Kubin and von Sikorski, 2021). The extent to which citizens are receptive to political messages might also depend on their level of interest in politics (Otjes and Rekker, 2021).

3 Data and methods

3.1 Selection of countries

In this study, we merge social media and opinion survey data sources at the individual level based on citizens’ political orientation to better understand the relationship between political discourse and public SWD. We adopt a cross-country perspective, investigating a selection of diverse democratic systems. To minimize cultural confounding, although preserving some heterogeneity, we limited our selection of countries to the Western European context. This focus is on countries within the Schengen area to ensure a consistent context of freedom of movement and common policies that might influence political discourse and public opinion. The inclusion of Switzerland and the UK, although non-EU countries, is justified by their significant political and economic interactions with the EU, making their political dynamics relevant for comparative analysis. More specifically, we choose countries belonging to the Schengen Area that took part in round 10 of the ESS (European Social Survey) and that did not undergo a parliamentary election during the ESS fieldwork.

A final selection of eleven countries met these criteria: Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. Table 1 reports the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU)’s democracy index (2021)1, showing that the selected countries rank high on the list of the 167 investigated countries.

Table 1

| Country | Last election | ESS fieldwork | Response rate (ESS data) | Mean SWD (ESS data) | EIU’s democracy index (rank) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Sept. 29, 2019 | 30-08-2021-06-12-2021 | 33.7 | 5.44 | 8.07 (20) |

| Finland | Apr. 14, 2019 | 31-08-2021-31-01-2022 | 41.1 | 7.33 | 9.27 (3) |

| France | Jun. 12, 2022 | 23-08-2021-31-12-2021 | 39.6 | 5.17 | 7.99 (22) |

| Germany | Sept. 26, 2021 | 05-10-2021-04-01-2022 | 37.0 | 5.93 | 8.67 (15) |

| Greece | Jul. 7, 2019 | 09-11-2021-23-05-2022 | 48.0 | 5.03 | 7.56 (34) |

| Italy | March 4, 2018 | 25-10-2021-26-04-2022 | 49.8 | 5.12 | 7.68 (31) |

| Netherlands | March 17, 2021 | 01-10-2021-03-04-2022 | 35.7 | 6.20 | 8.88 (11) |

| Spain | Nov. 10, 2019 | 21-01-2022-31-05-2022 | 35.5 | 4.65 | 7.94 (24) |

| Sweden | Sept. 9, 2018 | 10-12-2021-17-01-2022 | 37.9 | 6.22 | 9.26 (4) |

| Switzerland | Oct. 20, 2019 | 04-05-2021-02-05-2022 | 49.5 | 7.65 | 8.90 (9) |

| United Kingdom | Dec. 12, 2019 | 15-08-2021-02-09-2022 | 20.9 | 5.21 | 8.10 (18) |

List of selected countries.

ESS refers to the European Social Survey, SWD refers to satisfaction with democracy, EIU refers to the Economist Intelligence Unit.

This selection allows us to cover a range of different democratic systems. For instance, in Switzerland, voters are called to the polls up to four times annually, while combined ballots are exceptional measures that take place only every few years in other countries (e.g., France and Sweden). However, the average voter turnout in Switzerland is relatively low as a reflection of the frequency and complexity of the objects. Furthermore, participation in (action) groups (such as trade unions or civic organizations) is comparatively low in Switzerland. These differences can affect rankings of democracy quality, such as the EIU’s democracy index, as these processes might not be completely reflected in expert indexes.

3.2 Survey and social media data

To determine citizens’ SWD in their country, we used data from round 10 of the ESS. In particular, we retrieved the SWD item “How satisfied with the way democracy works in country.” The response scale ranges from 1 “Not at all satisfied” to 10 “Very satisfied.” This item constitutes the dependent variable.

The specific module of round 10 of the ESS emphasizes different dimensions of democracy while also differentiating between the meaning (e.g., support for the idea that it is important to live in a country governed democratically) and the satisfaction/evaluation (e.g., how far people think democracy lives up to this ideal in practice) of these dimensions (see Table 2). Politicians’ discourse on democracy was analysed to assess the extent to which the emphasis (or salience) of specific dimensions relates to citizens’ SWD. We use emphasis as a good approximation of the extent to which a democracy dimension is central to party communication and, thereby, the extent to which it is accessible to the public. To do so, we classified the tweets according to the democracy dimensions described by Kriesi et al. (2013) and Ferrin (2018). More specifically, we focused on the following democracy dimensions (see third column of Table 2): competition (or fairness of electoral procedures), representation, accountability, voice, institutional participation, social and political equality, efficiency, social and political fairness, institutional participation, voice, freedom and rule of law, responsiveness to citizens, and responsiveness to other stakeholders. We also included sovereignty (e.g., referring to defending a nation’s political autonomy, preserving cultural identity, and shielding the domestic economy), as well as political efficiency (e.g., referring to political authorities’ corruption and mismanagement of resources but also to the guaranty of parliament and government independence) as additional dimensions.

Table 2

| Variables | Statements (in country or importance) | Democracy dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| fairelc(c) | National elections are free and fair | Competition |

| dfprtal(c) | Different political parties offer clear alternatives to one another | Representation |

| medcrgv(c) | The media are free to criticise the government | Accountability (horizontal) |

| gptpelc(c) | Governing parties are punished in elections when they have done a bad job | Accountability (vertical) |

| rghmgpr(c) | The rights of minority groups are protected | Fairness |

| gvctzpv(c) | The government protects all citizens against poverty | Fairness |

| grdfinc(c) | The government takes measures to reduce differences in income levels | Fairness |

| votedir(c) | Citizens have the final say on political issues by voting directly in referendums | Participation (institutional) |

| wpestop(c) | The will of the people cannot be stopped | Voice (any actions) |

| cttresa(c) | The courts treat everyone the same | Rule of law |

| viepol(c) | The views of ordinary people prevail over the views of the political elite | Responsiveness (to citizens) |

| keydec(c) | key decisions are made by national governments rather than the European Union | Responsiveness (to other stakeholders) |

| / (not in ESS) | The defence of a nation’s political autonomy, preserving cultural identity, and shielding the domestic economy | Sovereignty |

| / (not in ESS) | Political authorities’ corruption and mismanagement of resources, but also to the guaranty of parliament and government independence | Political efficiency |

Description of ESS statements about democracy and their reduction in core democracy dimensions.

The level of mean public satisfaction with respect to each of these democracy dimensions is given in Table 3. We see that “responsiveness to citizens,” “institutional participation” and “voice” are the dimensions on which satisfaction is the lowest on average across countries.

Table 3

| Accountability | Competition | Fair | Institutional participation | Representation | Responsiveness to citizens | Responsiveness to other stakeholders | Rules | Voice | Overall mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | 7.9 | 9.3 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 6.3 | 7.1 |

| Switzerland | 7.2 | 8.3 | 6.4 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 6.2 | 7.0 |

| United Kingdom | 6.6 | 8.2 | 5.4 | 6.1 | 7.4 | 4.6 | 7.6 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 6.4 |

| Sweden | 7.2 | 8.7 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 6.3 |

| Netherlands | 6.7 | 8.2 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 6.7 | 4.4 | 6.3 | 7.2 | 5.2 | 6.1 |

| Austria | 6.2 | 8.1 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 4.0 | 5.7 |

| Germany | 6.8 | 8.2 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 6.6 | 4.0 | 5.6 |

| Spain | 5.7 | 7.5 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 4.9 |

| France | 5.7 | 7.2 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 4.9 |

| Greece | 5.2 | 7.3 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 4.9 |

| Italy | 4.7 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| Overall mean | 6.3 | 7.8 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 6.1 | 3.9 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 4.7 |

Mean satisfaction with democracy dimensions (item asking how far people think democracy lives up to this ideal in practice).

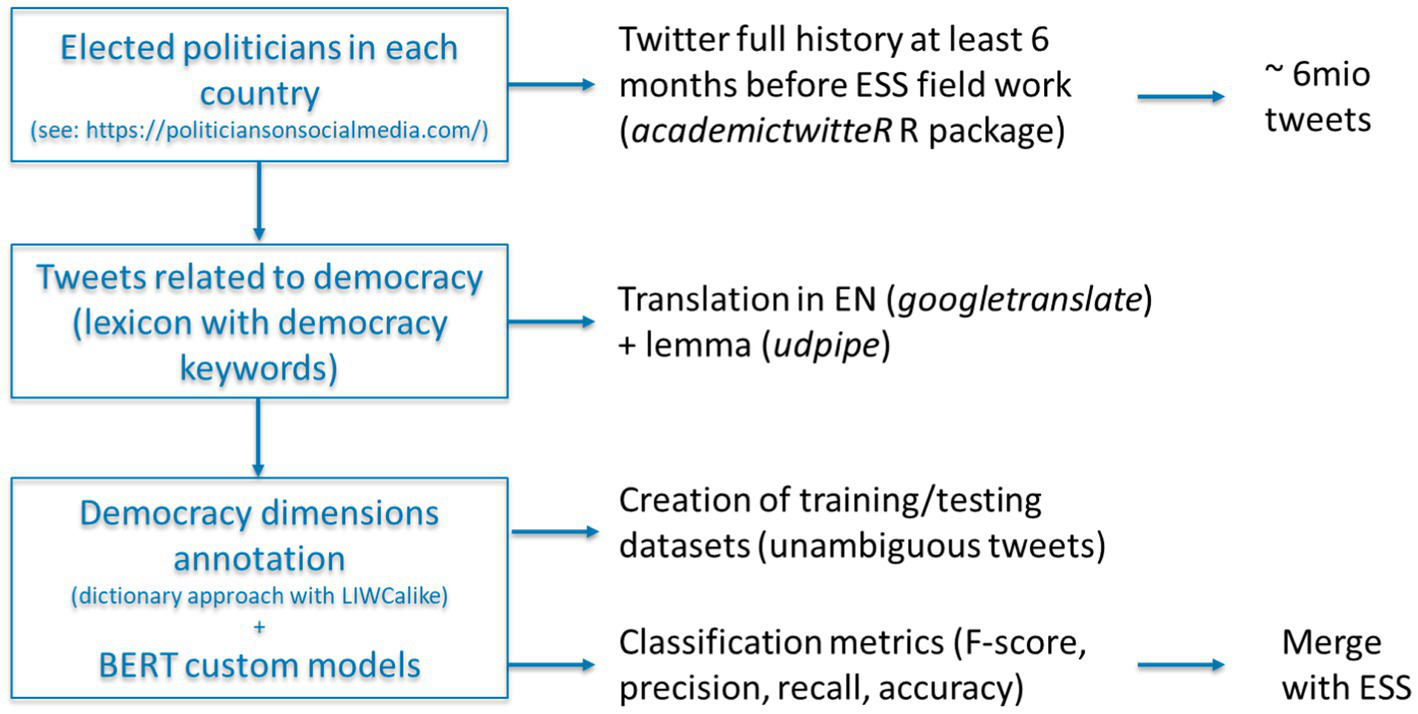

To capture the main framings associated with national and partisan democracy opinions, we extract tweets by elected politicians in each country. Figure 1 summarizes the different steps involved in the collection, filtering, and classification of politicians’ tweets. The list of politicians’ accounts was obtained from the Politicians on Social Media project (Haman and Školník, 2021) and updated manually for countries in which a more recent parliamentary election has been held. We focused only on politicians with an active political mandate. Twitter data were collected for a period of 6 months before the starting date of the ESS fieldwork in the respective countries.

Figure 1

Steps involved in the collection, filtering, and classification of politicians’ tweets.

Regarding data collection, we used Twitter’s Academics API to access politicians’ full tweet history (original tweets, retweets and replies). We relied on the academictwitteR wrapper (Barrie and Ho, 2021) from the R programming language. For each politician, we also specified his political affiliation.

As our focus is on tweets related to democracy ideas and perceptions, we filtered tweets containing specific keywords. The keywords were first generated based on Wordnet and the RelatedWords2 webpages to retrieve synonyms and words associated with the term “democracy.” A list was elaborated based on the identified candidate terms in English. Then, the authors independently coded the candidate terms for their inclusion or exclusion in the final list (Cohen’s kappa 0.76). The divergences were discussed, and a final list (see Supplementary Table S1 for the English terms) was elaborated and translated into the different country languages by native speakers. Our final corpus of selected tweets related to democracy contains 16,505 tweets from 167 Swiss politicians and 474,751 tweets from 3,075 other politicians.

After selection based on keywords related to democracy, preprocessing steps were conducted, which included the removal of URLs as well as the division of concatenated hashtags (e.g., “#RuleOfLaw” becomes “rule of law”). On this basis, the tweets were translated into English using Google Translate. Once translated, the tweets are lemmatized using the udpipe library from the R programming language (Wijffels et al., 2018). We also considered only words with more than two characters. Thus, after removing any unconventional features, we converted the remaining text to lowercase. We also removed any stop words from a document (e.g., “the,” “and” “are”), which have little bearing on the overall meaning of the document. Additionally, we removed words that are specific to Twitter terminology (e.g., “&,” “rt”).

Then, to assess the prevalence of the specific democracy dimensions (see Table 2), we draw on a custom dictionary containing 1,072 words validated in a previous study (Reveilhac and Morselli, 2022). The dictionary was applied to the collected tweets using the liwcalike function from the quanteda.dictionarie package for the R programming language. The function tags each tweet with the proportion of words that fall into each dimension. We randomly sampled 1,000 tweets from each democracy dimension to train the classification model. To label each tweet, we selected the dimension corresponding to the higher proportion. We did not assign a label to tweets having the same proportion on several dimensions. The tweets that could be labelled by the dictionary can be considered as “emblematic” of each democracy dimension and were used as a training set to train a classification model based on the BERT (Devlin et al., 2018) algorithm for Python. The classification accuracy for each democracy dimension is given in Table 4. The resulting classification model was applied to unseen tweets.

Table 4

| Dimension | Precision | Recall | F1 score | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accountability | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.87 |

| Competition | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.93 |

| Efficiency | 0.69 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.84 |

| Fair | 0.89 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.73 |

| Institutional participation | 0.43 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.99 |

| Representation | 0.60 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.82 |

| Responsiveness to citizens | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.81 |

| Responsiveness to other stakeholders | 0.94 | 0.75 | 0.84 | 0.87 |

| Rules | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.85 |

| Sovereignty | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| Voice | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.90 |

Classification accuracy from the training set for each dimension.

The chosen classification model involves unsupervised pretraining based on word embeddings (Mikolov et al., 2013; Joulin et al., 2017). More specifically, our custom BERT model was pretrained on our training dataset to generate context-specific embeddings. We then conducted multinomial regression on the top of the BERT representation for predicting democracy dimensions. We assessed the classification accuracy by applying the model to a held-out test dataset (which represents 20% of the labelled tweets).

3.3 Merging strategy of both data sources

We relied on the ESS items asking respondents to mention their proximity to major parties in each country. For each respondent, we assigned the preferred party preference. If no party was mentioned, we assigned the political orientation measured on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 “Extreme left” to 10 “Extreme right,” which we recoded into three categories (1–4 as “left,” 5–6 as “centre,” and 7–10 as “right”). We also assigned a similar left/centre/right categorization to each party mentioned.

For each country, we merged survey and social media data using political orientation as an aggregating variable. Individual-level responses to the ESS were averaged by the respondent’s left/centre/right classification. Similarly, Twitter data were classified as left/centre/right depending on the party orientation of the politician. We aggregated only tweets emitted 6 months prior to respondents’ date of survey completion. We add one column per democracy dimension, and each column represents the share (or salience) of tweets dedicated to the specific dimensions. When merging the data, we used party preference when available or the political left-centre-right orientation if otherwise.

3.4 Analytical strategy

Our analytical strategy aims for a detailed exploration of the role that political information plays in a real-world assessment of democracy. To do so, we rely on a multistep strategy:

First, we rely on Spearman rank correlation between survey answers (satisfaction) and salience in politicians’ tweets of the democracy dimensions.

Second, we display the distance between surveyed attitudes towards democracy dimensions (items about the “importance” of each dimension) and the prevalence of political discourse on Twitter on the same dimensions.

Third, we rely on density plots to highlight the (theoretical) exposition of respondents to political messages (tells us how likely democracy dimensions are accessible to citizens given their political orientation).

Fourth, we use random forest-based variable importance analysis to determine how politicians’ emphasis on democracy dimensions is related to citizens’ SWD.

The reliance on variable importance analysis is inspired by previous studies that have used social media data to understand public opinions and attitudes (e.g., climate change beliefs as in Kirilenko and Stepchenkova, 2014 or Cody et al., 2015) and to elucidate the constituent factors that contribute to individuals’ opinions (Bennett et al., 2021). Variable importance analysis is based on the idea that the more a model relies on a variable to make predictions, the more important this variable is for the model. The relative importance for a single independent variable can be determined by deconstructing the model weights. This enables us to reveal the relative relevance (or degree of association) of a certain explanatory variable for the response variable. Random forest offers several advantages. First, it can account for nonlinear relationships and interactions in the data without the need to specify them (Molina and Garip, 2019). Second, it can handle cross-level data, as we are studying individual-level SWD and contextual emphasis on democracy. Third, random forest allows us to quantify the importance of a variable.

In our study, we used the average Gini impurity to measure how well the data were split, that is, how well it correctly predicts respondents being satisfied or dissatisfied with democracy (i.e., Gini = 0 if a covariate perfectly splits the data, Gini>0 for an imperfect split). Specifically, we use a random forest model (as implemented in the R package randomForest from Liaw and Wiener, 2002) that estimates the importance of variables in a model: if the trees in the forest split the sample by dimension A more than by dimension B, then dimension A is more important to the model. We use the results from the variable importance analysis to assess which democracy dimension most affects SWD with mean Gini impurity as the threshold when other control variables (e.g., gender, age, education and political interest) are included in the model. This allows us to make comparisons across the effect of the emphasis of the democracy dimensions on citizens’ SWD.

4 Results

4.1 Correlation between public opinion and social media discourse

The analysis of the correlation between citizens’ satisfaction with each democracy dimension and the salience of these dimensions in politicians’ tweets is calculated based on Spearman rank correlation. We only included democracy dimensions that were also surveyed (thus, efficiency and sovereignty are excluded from Table 5). There is variability across the countries, as the correlation is high for Germany, Austria, and Finland (ρ >0.3). It is moderated for the United Kingdom and Greece and low for Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands, France and Sweden. It is even negative for Spain. This might suggest that the dimensions that are considered the least satisfactory from citizens’ perspective are not necessarily the ones emphasized in politicians’ tweets. Low and negative correlations might even indicate a disconnect between citizens’ preoccupations and politicians’ emphasis.

Table 5

| Country | Spearman correlation |

|---|---|

| Germany | 0.60 |

| Austria | 0.33 |

| Finland | 0.32 |

| UK | 0.18 |

| Greece | 0.10 |

| Italy | 0.09 |

| Switzerland | 0.05 |

| Netherlands | 0.02 |

| France | 0.02 |

| Sweden | 0.00 |

| Spain | −0.34 |

Correlation between citizens’ satisfaction and salience in politicians’ tweets.

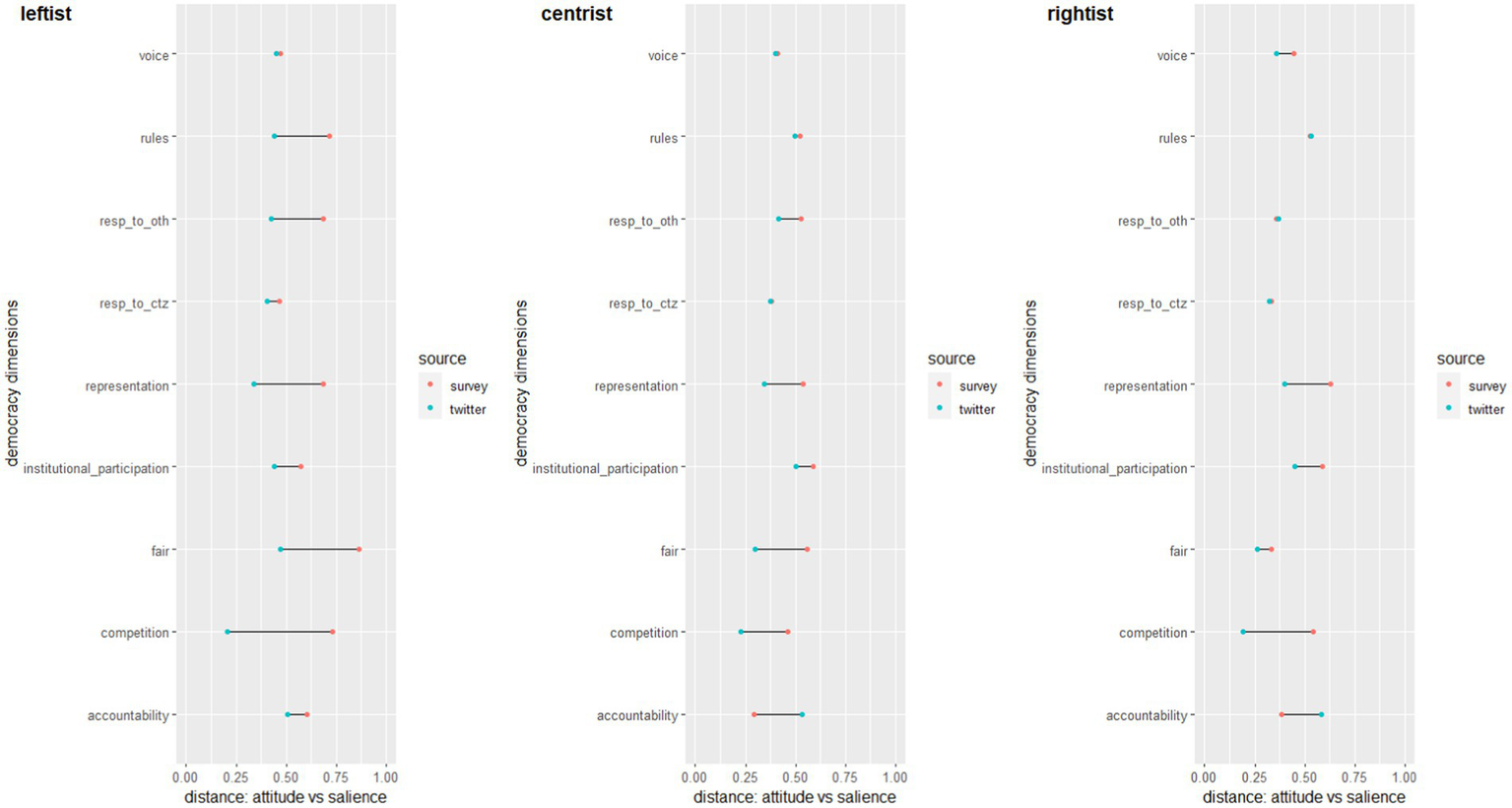

4.2 Density plots: exposition of citizens to political discourse

Figure 2 presents a measure of distance between the attitude towards each democratic dimension (item asking survey respondents to what extent the dimension “is important”) and the salience in politicians’ tweets by political orientation. Both measures are standardized between 0 and 1. The smaller the distance between surveyed attitudes and tweet salience, the higher the resonance between public opinion and politicians’ discourse, while a large distance implies a gap between citizens’ opinions and politicians’ discourse. We only included democracy dimensions that were also surveyed (thus, efficiency and sovereignty are excluded from Figure 2). Furthermore, the item on “responsiveness to other stakeholders” is reversed.

Figure 2

Normalized score between ESS attitudes and Twitter salience across dimensions for each political orientation.

Figure 2 shows a smaller distance among right-wing oriented citizens and politicians. Wide gaps were found among the left, especially in relation to rules, fairness, responsiveness to other stakeholders, competition, and representation, with politicians massively underdiscussing the dimensions compared to the importance given to them by their electorate. It is also worth noting that survey responses on these dimensions indicated a higher importance among left-wing respondents than centre and right-wing respondents. Accountability was the only dimension to be overstressed by (right and centre) politicians when compared to their electorate.

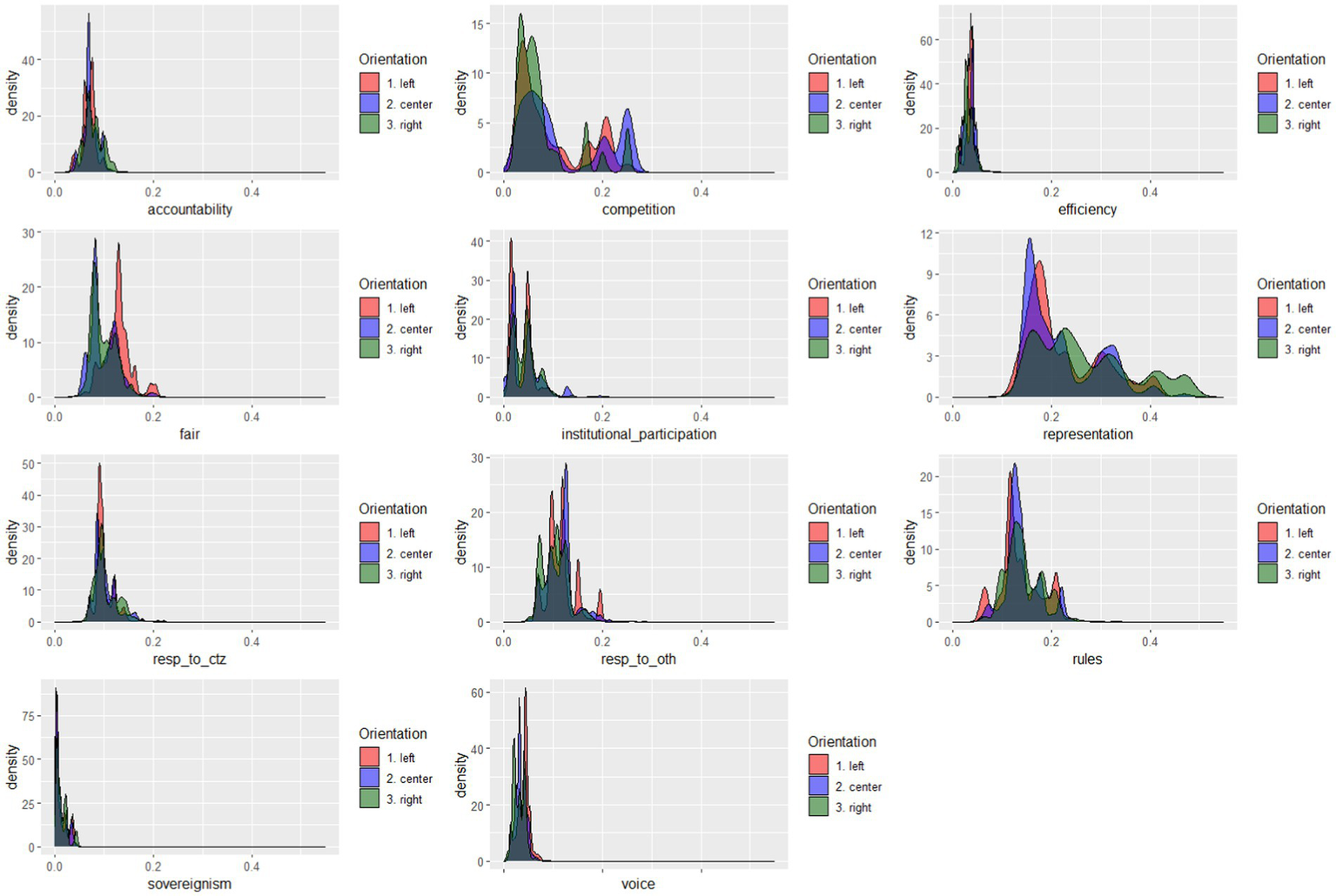

To further assess which political messages citizens are more likely to be exposed to, Figure 3 displays the density plots of the saliency of each democracy dimension in the tweets of politicians, according to their political orientation. All democracy dimensions are considered, and Figure 3 provides the average scores across countries. One-way ANOVA test with country as the grouping variable shows significant differences across countries for accountability (with Finland displaying the highest salience and the United Kingdom displaying the lowest salience, p < 0.05), competition (with Germany displaying the highest salience and Spain displaying the lowest salience, p < 0.05), efficiency (Netherlands highest and France lowest, p < 0.05), fairness (Spain highest and Greece lowest, p < 0.05), institutional participation (Switzerland highest and Finland lowest, p < 0.05), representation (Sweden highest and Germany lowest, p < 0.05), responsiveness to citizens (Switzerland highest and Germany lowest, p < 0.05), responsiveness to other stakeholders (Switzerland highest and Sweden lowest, p < 0.05), responsiveness to other stakeholders (Switzerland highest and Sweden lowest, p < 0.05), rules (Spain highest and Sweden lowest, p < 0.05), and voice (Netherland highest and Austria lowest, p < 0.05).

Figure 3

Density plot for all countries.

Figure 3 and one-way ANOVA with political orientation as the grouping variable show that citizens with a right-wing orientation are more likely to be exposed to discourses about accountability, representation, institutional participation, rules and sovereignty. Citizens with a left-wing orientation are essentially exposed to the dimensions related to fairness, responsiveness to other stakeholders, and voice. Exposition specific to centrist citizens is less clear-cut, but electoral competition, efficiency and responsiveness to citizens appear as salient dimensions. Some dimensions are salient across ideological preferences, such as competition and representation.

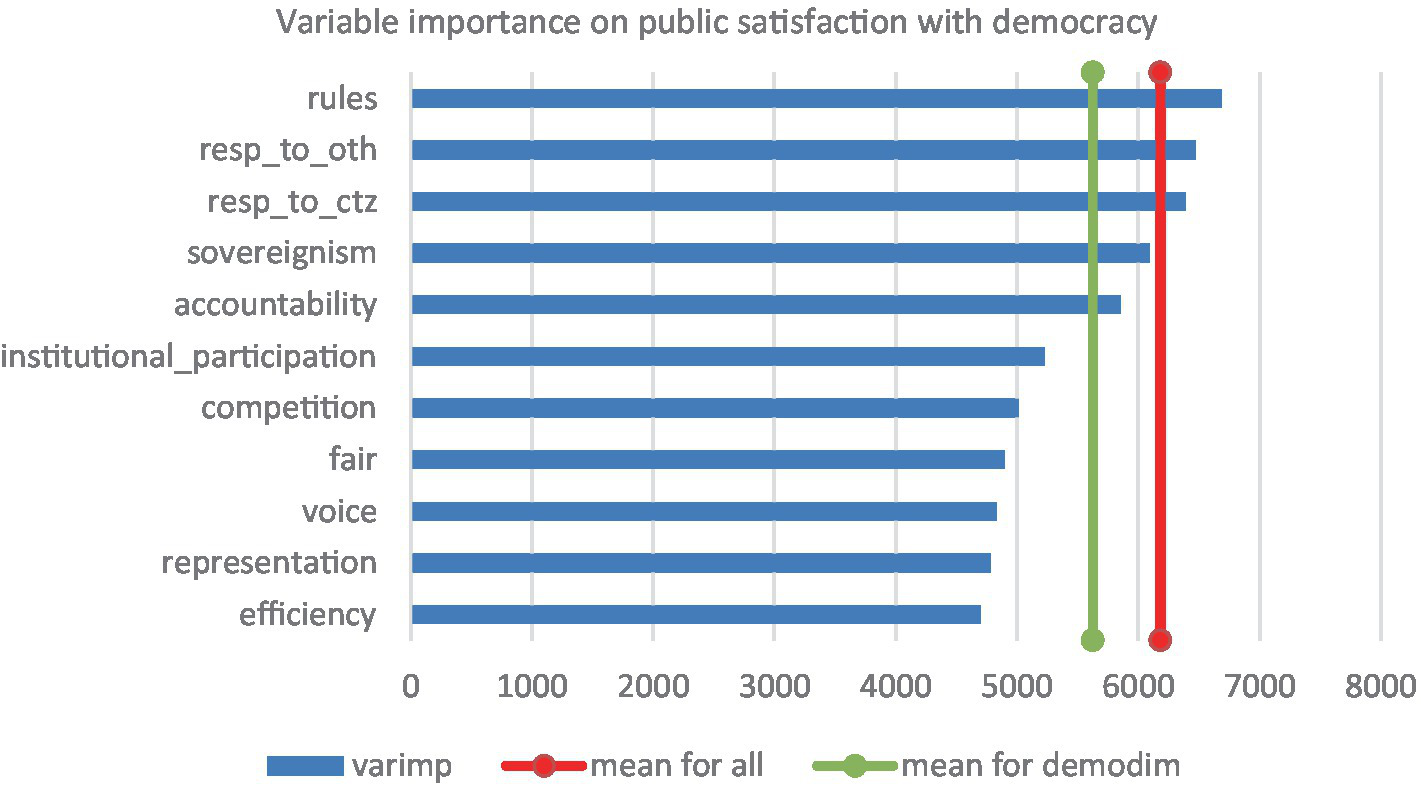

4.3 Variable importance analysis: impact of democracy dimensions on citizens’ SWD

Figure 4 displays the results of variable importance to predict respondents’ SWD (controlled by gender, age, years of education, political interest, and country). The grey vertical line corresponds to the mean variable importance for the variables related to the democracy dimensions, while the red line also accounts for the control variables. The democracy dimensions that have values above these thresholds are the most important for predicting SWD.

Figure 4

Variable importance for all countries. “Resp_to_ctz” means “responsiveness to citizens,” and “resp_to_oth” means “responsiveness to other stakeholders.”

Figure 4 shows that rules and responsiveness to other stakeholders and to citizens are the most important dimensions for predicting citizens’ SWD across countries. These results suggest that discourses from the right generally have more influence on predicting citizens’ SWD. It is also noticeable that the voice, sovereignty and accountability dimensions are impactful if we take the mean threshold for all democracy dimensions. The least important dimensions to predict overall satisfaction with democracy are voice, representation and efficiency. The other dimensions remain below the threshold values but can nevertheless be more impactful in some countries. For instance, institutional participation is moderately important, but analyses for individual countries (not shown here) demonstrate that this dimension can be salient in some contexts (e.g., in France, political discussions asking for more direct democracy procedures were prevalent in relation to the Yellow Jackets claims).

5 Discussion of main findings

The correlation between citizens’ satisfaction and salience in politicians’ tweets resonates with previous research (e.g., Hobolt et al., 2021) on national political cultures that state that congruence between the offerings of political discourse and citizens’ attitudes is a source of greater satisfaction with democracy. For instance, countries with higher correlations, such as Germany, Austria, and Finland, might exhibit more congruence between citizens’ satisfaction levels and the dimensions emphasized in political discourse due to specific political dynamics or media environments that facilitate alignment. However, countries with a high SWD, such as Switzerland, reflect the multifaceted nature of democratic evaluations and the intricate interplay between political rhetoric and public sentiment. Furthermore, in contexts with moderate correlations such as United Kingdom and Greece, citizens’ attitudes might be influenced by a combination of political discourse and broader sociopolitical factors. The identification of low and negative correlations, particularly in Italy and Spain, suggests a potential misalignment between citizens’ concerns and the themes emphasized by politicians. This observation resonates with the role of political elites in shaping the public agenda (Gilardi et al., 2022). Such a disconnect can undermine the legitimacy of political institutions and underscore the need for responsive communication strategies.

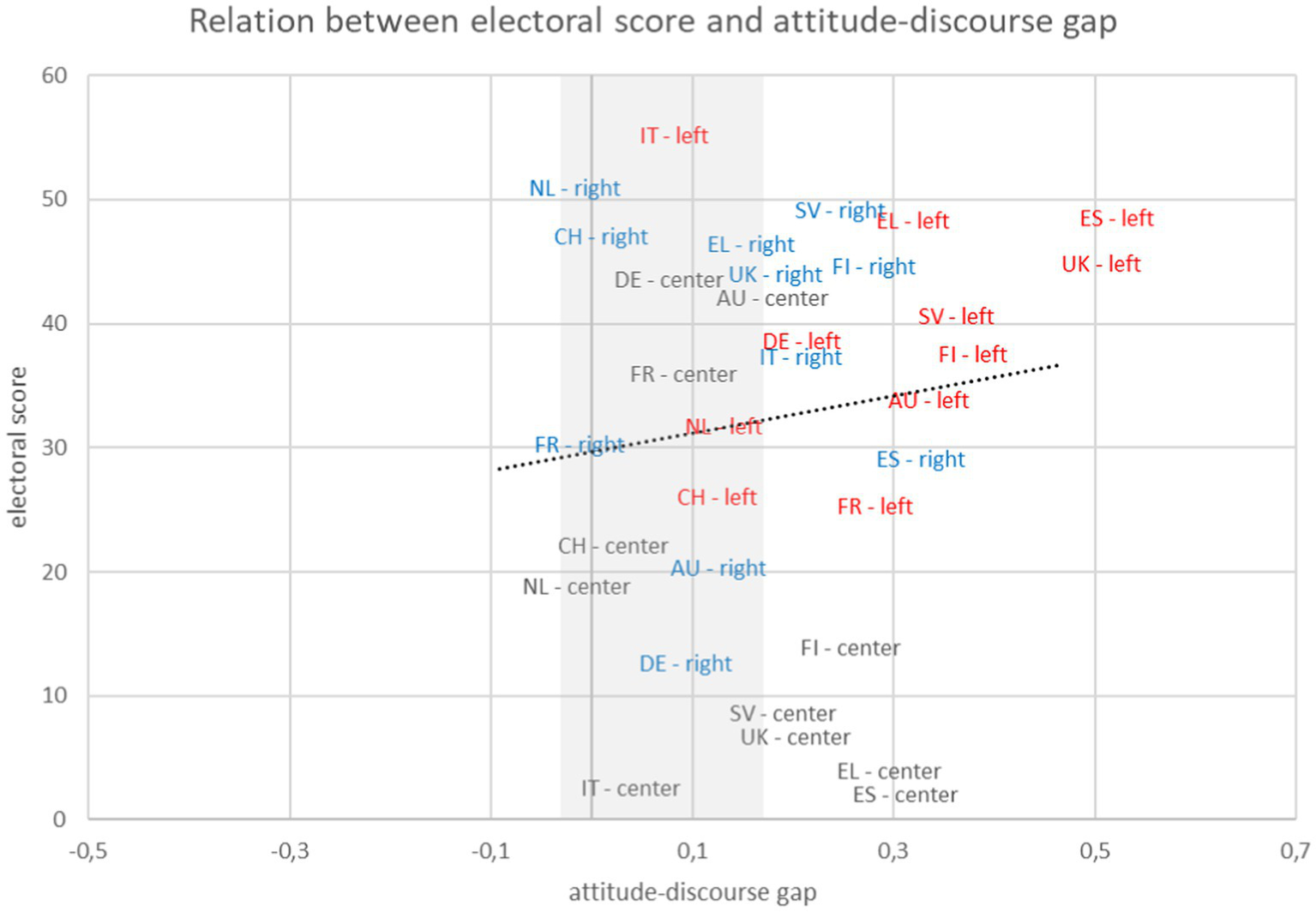

Our analysis of the distance between politicians’ tweets and survey responses also shows that the gap is not the same across the different political orientations, with right-wing politicians being more in line with their electorate, while wider gaps have been found on the left. Figure 5 displays the relationship between electoral score (aggregated by party orientation: left-centre-right) and attitude-discourse gap for each country. Overall, there is a weak positive correlation: higher electoral scores are associated with a higher attitude-discourse gap. In other words, this aggregated finding shows that a wider gap does not necessarily lead to a higher probability of losing electorate. A more fine-grained analysis could be conducted by focusing on populist parties only, thus concurring in the explanation of the electoral success of the right-wing party that Europe has been witnessing in recent years. However, further evidence is needed on this matter.

Figure 5

Relation between electoral score and attitude-discourse gap.

The findings presented above resonate with several strands of literature in political science and public opinion research. First, the identification of specific democracy dimensions that significantly impact citizens’ SWD aligns with the literature on the multidimensionality of democratic attitudes (Schaffer, 2014). This study shows that several aspects of democracy, such as competition, voice, accountability, institutional participation, and representation, contribute to citizens’ overall SWD. Second, the observation that dimensions salient to different ideological groups have varying impacts on SWD echoes the literature on ideological polarization and its influence on citizens’ attitudes (König et al., 2022; Bryan, 2023). It underscores the role of political ideology in shaping how individuals evaluate democratic performance. Third, the nuanced impact of the institutional participation and voice dimensions resonates with research that explores the influence of more direct forms of democratic participation on citizens’ democratic attitudes (Donovan and Karp, 2006; Bengtsson and Mattila, 2009; Medvic, 2019). Taken together with the findings from Figures 2, 3, the study offers a nuanced exploration of citizens’ exposure to distinct democracy dimensions based on their political inclinations. The findings provide valuable insights to learn more about what citizens expect from democracy and which dimensions are salient for them (Ariely and Davidov, 2011; Dahlberg et al., 2020). Focusing particularly on parties that have made the internet a central element of their strategy, such as the Five Star Movement in Italy, would bring more qualitative insights. Such an analysis could shed light on the unique impact of digital engagement strategies on public satisfaction with democracy and offer a deeper understanding of the relationship between political communication in the digital age and citizens’ democratic attitudes.

6 Conclusion and outlook

The research presented in this paper offers valuable insights into the connection between citizens’ opinions on democracy and the portrayal of related themes in politicians’ social media messages. The present study thus enables us to propose a complementary approach to survey measures of democracy attitudes by focusing on the content of political discourse (Schaffer, 2014; Dahlberg et al., 2020). However, there are certain limitations that should be acknowledged.

First, the research focuses on eleven Western European countries. In this research, we used Switzerland as a comparison case because of its specific direct democracy system. The limited selection of countries might not fully capture the diversity of global political contexts. Second, the study concentrates on social media messages from elected officials. However, social media platforms might not fully represent the entirety of political discourse, potentially excluding voices from nonelected officials, interest groups, and the general public. Third, the utilization of a word embedding classification strategy to extract democracy-related themes from politicians’ messages is a valuable approach, but its effectiveness is reliant on the quality and completeness of the corpus used for embedding. Fourth, the approach of connecting citizens’ attitudes to the prominence of democracy-related themes in politicians’ messages assumes a certain level of homogeneity in how citizens engage with political discourse across countries. Finally, the study’s reliance on social media data assumes a certain level of digital engagement among citizens.

Future research might also conduct additional analysis in the direction of causality. While the study explores the alignment between citizens’ attitudes, politicians’ messages, and public contentment with democracy, it definitively does not establish causal relationships. Focusing particularly on parties that have made the internet a central element of their strategy, such as the Five Star Movement in Italy, would bring more qualitative insights. Such an analysis could shed light on the unique impact of digital engagement strategies on public satisfaction with democracy and offer a deeper understanding of the relationship between political communication in the digital age and citizens’ democratic attitudes. Other factors and variables not considered in the study might also contribute to public contentment with democracy, and the analysis might not account for all potential confounding factors. Recent literature provides alternative explanations for the decline in public trust and support for democracy, which can complement and enhance the overall picture presented in this study. Bienstman et al. (2024) discuss the impact of inequality on political trust and external efficacy, offering insights into how socioeconomic factors contribute to democratic malaise. Dawson and Krakoff (2024) re-examine the critical citizen thesis, highlighting the evolving nature of political trust and its implications for democratic stability. Gherghina and Miscoiu (2022) explore the effects of direct democracy on regime legitimacy, emphasizing how different democratic practices can influence public perceptions. By incorporating these perspectives, future research can build on the insights presented here to further elucidate the complex relationship between political discourse and public satisfaction with democracy.

The main practical and theoretical contributions of this study include the research framework, cross-national analysis, utilization of social media data, and interdisciplinary approach. More precisely, it introduces an unsupervised framework that contributes to bridging the gap between citizens’ opinions on democracy and politicians’ social media messages. Furthermore, by analysing multiple democracy-related dimensions and their connection to citizens’ attitudes, the research provides a nuanced understanding of the factors that influence public contentment with democracy. Practically, the use of the 10th round of the ESS as a basis for assessing citizens’ democratic attitudes ensures a robust empirical foundation for the study’s analyses and conclusions. Furthermore, the application of variables enables us to identify which democracy-related themes hold significance in predicting public contentment with democracy, thus enhancing the precision of the findings.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the University Library Zurich for the financial support in publishing this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1385678/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^ See the EIU’s latest report (2021) here: https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2022/

References

1

Ariely G. (2014). Democracy-assessment in cross-national surveys: a critical examination of how people evaluate their regime. Soc. Indic. Res.121, 621–635. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0666-y

2

Ariely G. Davidov E. (2011). Can we rate public support for democracy in a comparable way? Cross-national equivalence of democratic attitudes in the world value survey. Soc. Indic. Res.104, 271–286. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9693-5

3

Bengtsson Å. Mattila M. (2009). Direct democracy and its critics: support for direct democracy and ‘stealth’democracy in Finland. West Eur. Polit.32, 1031–1048. doi: 10.1080/01402380903065256

4

Bennett J. Rachunok B. Flage R. Nateghi R. (2021). Mapping climate discourse to climate opinion: An approach for augmenting surveys with social media to enhance understandings of climate opinion in the United States. PloS one16:e0245319.

5

Bienstman S. Hense S. Gangl M. (2024). Explaining the ‘democratic malaise’in unequal societies: Inequality, external efficacy and political trust. Eur. J. Political Res.63, 172–191. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12611

6

Blank G. Lutz C. (2017). Representativeness of social media in great britain: investigating Facebook, Linkedin, Twitter, Pinterest, Google+, and Instagram. Am. Behav. Sci.61, 741–756.

7

Barrie C. Ho J. C. T. (2021). academictwitteR: an R package to access the Twitter Academic Research Product Track v2 API endpoint. J. Open Source Softw.6:3272.

8

Bryan J. D. (2023). What kind of democracy do we all support? How partisan interest impacts a Citizen’s conceptualization of democracy. Comp. Pol. Stud.56, 1597–1627. doi: 10.1177/00104140231152784

9

Canache D. Mondak J. J. Seligson M. A. (2001). Meaning and measurement in cross-national research on satisfaction with democracy. Public Opin. Q.65, 506–528. doi: 10.1086/323576

10

Careja R. (2016). Party discourse and prejudiced attitudes toward migrants in Western Europe at the beginning of the 2000s. Int. Migr. Rev.50, 599–627. doi: 10.1111/imre.12174

11

Ceron A. Memoli V. (2016). Flames and debates: do social media affect satisfaction with democracy?Soc. Indic. Res.126, 225–240. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-0893-x

12

Cody E. M. Reagan A. J. Mitchell L. Dodds P. S. Danforth C. M. (2015). Climate change sentiment on twitter: an unsolicited public opinion poll. PLoS One10:e0136092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136092

13

Czymara C. S. (2020). Propagated preferences? Political elite discourses and Europeans’ openness toward Muslim immigrants. Int. Migr. Rev.54, 1212–1237. doi: 10.1177/0197918319890270

14

Dahlberg S. Axelsson S. Holmberg S. (2020). Democracy in context: using a distributional semantic model to study differences in the usage of democracy across languages and countries. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft14, 425–459. doi: 10.1007/s12286-020-00472-3

15

Dalton R. J. Shin D. C. Jou W. (2007). Understanding democracy: data from unlikely places. J. Democracy18:142. doi: 10.1353/jod.2007.a223229

16

Dawson A. Krakoff I. L. (2024). Political trust and democracy: the critical citizens thesis re-examined. Democratization31, 90–112. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2023.2257607

17

Devlin J. Chang M. W. Lee K. Toutanova K. (2018). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1810.04805

18

Donovan T. Karp J. A. (2006). Popular support for direct democracy. Party Polit.12, 671–688. doi: 10.1177/1354068806066793

19

Dubois E. Gaffney D. (2014). The multiple facets of influence: identifying political influentials and opinion leaders on twitter. Am. Behav. Sci.58, 1260–1277. doi: 10.1177/0002764214527088

20

Dür A. Schlipphak B. (2021). Elite cueing and attitudes towards trade agreements: the case of TTIP. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev.13, 41–57. doi: 10.1017/S175577392000034X

21

Feezell J. T. (2018). Agenda setting through social media: the importance of incidental news exposure and social filtering in the digital era. Polit. Res. Q.71, 482–494. doi: 10.1177/1065912917744895

22

Ferrin M. (2016). “An empirical assessment of satisfaction with democracy” in How Europeans view and evaluate democracy. eds. FerrínM.KriesiH. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 283–306.

23

Ferrin M. (2018). The European social survey round 10 question module design teams (QDT) stage 2 application. Available at: https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round10/questionnaire/ESS10_ferrin_proposal.pdf (Accessed on March 1, 2021).

24

Flores R. D. (2018). Can elites shape public attitudes toward immigrants?: evidence from the 2016 US presidential election. Soc. Forces96, 1649–1690. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy001

25

Gilardi F. Gessler T. Kubli M. Müller S. (2022). Social media and political agenda setting. Polit. Commun.39, 39–60. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2021.1910390

26

Gherghina S. Miscoiu S. (2022). “Les effets de la démocratie directe sur la confiance dans les institutions et la démocratie,” in Démocraties directes. eds. Magni-BertonR.MorelL., (Bruxelles: Bruylant), 293–300.

27

Haman M. Školník M. (2021). Politicians on social media. The online database of members of national parliaments on twitter. Profesional de la información30:e300217. doi: 10.3145/epi.2021.mar.17

28

Hameleers M. (2018). A typology of populism: toward a revised theoreticoal framework on the sender side and receiver side of communication. Int. J. Commun.12:20.

29

Hobolt S. B. Hoerner J. M. Rodon T. (2021). Having a say or getting your way? Political choice and satisfaction with democracy. Eur J Polit Res60, 854–873. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12429

30

IDEA (2018). Inspiring change, achieving results. Annual Outcome Report 2018. Available at: https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/reference_docs/INT_IDEA_2018_Outcome_Report_15-04-19_spread_0.pdf (Accessed on March 1, 2021).

31

IDEA (2020). The global state of democracy. Populist government and democracy: An impact assessment using the global state of democracy indices. Available at: https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/populist-government-and-democracy-impact-assessement-using-gsod-indices.pdf (Accessed on March 1, 2021).

32

Inglehart R. (2003). How solid is mass support for democracy: and how can we measure it?Polit. Sci. Polit.36, 51–57. doi: 10.1017/S1049096503001689

33

Inglehart R. Welzel C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

34

Jones P. E. Brewer P. R. (2020). Elite cues and public polarization on transgender rights. Politics, Groups Identities8, 71–85. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2018.1441722

35

Joulin A. Grave E. Bojanowski P. Nickel M. Mikolov T. (2017). Fast linear model for knowledge graph embeddings. arXiv. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1710.10881

36

Katz E. Lazarsfeld P. F. (1955). Personal influence, the part played by people in the flow of mass communications. New York, NY: The Free Press.

37

Kirilenko A. P. Stepchenkova S. O. (2014). Public microblogging on climate change: one year of twitter worldwide. Glob. Environ. Chang.26, 171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.02.008

38

König P. D. Siewert M. B. Ackermann K. (2022). Conceptualizing and measuring citizens’ preferences for democracy: taking stock of three decades of research in a fragmented field. Comp. Pol. Stud.55, 2015–2049. doi: 10.1177/00104140211066213

39

Kortenska E. Steunenberg B. Sircar I. (2020). Public-elite gap on European integration: the missing link between discourses among citizens and elites in Serbia. J. Eur. Integr.42, 873–888. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2019.1688317

40

Kriesi H. Morlino L. Magalhães P. Alonso S. Ferrín M. (2013). European social survey round 6 module on Europeans’ understandings and evaluations of democracy – Final module in template. London: Centre for Comparative Social Surveys, City University London.

41

Kubin E. von Sikorski C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: a systematic review. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc.45, 188–206. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2021.1976070

42

Liaw A. Wiener M. (2002). Classification and regression by randomForest. R news2, 18–22.

43

Maciel G. G. de Sousa L. (2018). Legal corruption and dissatisfaction with democracy in the European Union. Soc. Indic. Res.140, 653–674. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1779-x

44

Mauk M. (2021). Quality of democracy makes a difference, but not for everyone: how political interest, education, and conceptions of democracy condition the relationship between democratic quality and political trust. Front. Polit. Sci.3:637344. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.637344

45

McDermott M. L. (2005). Candidate occupations and voter information shortcuts. J. Polit.67, 201–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00314.x

46

McGregor S. C. (2019). Social media as public opinion: how journalists use social media to represent public opinion. Journalism20, 1070–1086. doi: 10.1177/1464884919845458

47

Medvic S. (2019). Explaining support for stealth democracy. Representation55, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2019.1581076

48

Mikolov T. Yih W. T. Zweig G. (2013). Linguistic regularities in continuous space word representations. In Proceedings of the 2013 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: Human language technologies.

49

Molina M. Garip F. (2019). Machine learning for sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol.45, 27–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041106

50

Newman N. Fletcher R. Kalogeropoulos A. Levy D. A. L. Nielsen R. K. (2017). Reuters institute digital news report 2017. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of journalism. Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Digital%20News%20Report%202017%20web_0.pdf

51

Norris P. (1999). Critical citizens: Global support for democratic government. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

52

Norris P. (2017). Is Western democracy backsliding? Diagnosing the risks. J. Democr. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2933655

53

Norris P. Inglehart R. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. Harvard: Harvard JFK School.

54

O'Donnell G. (2007). Dissonances: democratic critiques of democracy. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

55

Otjes S. Rekker R. (2021). Socialised to think in terms of left and right? The acceptability of the left and the right among European voters. Elect. Stud.72:102365. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102365

56

Quaranta M. (2017). How citizens evaluate democracy: an assessment using the European social survey. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev.10, 191–217.

57

Reveilhac M. Morselli D. (2022). Dictionary-based and machine learning classification approaches: a comparison for tonality and frame detection on twitter data. Polit. Res. Exchange4:2029217. doi: 10.1080/2474736X.2022.2029217

58

Rooduijn M. De Lange S. L. Van Der Brug W. (2014). A populist zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe. Party Polit.20, 563–575. doi: 10.1177/1354068811436065

59

Schaffer F. C. (2014). Thin descriptions: the limits of survey research on the meaning of democracy. Polity46, 303–330. doi: 10.1057/pol.2014.14

60

Schroeder R. (2018). Towards a theory of digital media. Inf. Commun. Soc.21, 323–339. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1289231

61

Shin D. C. (2017). “Popular understanding of democracy” in Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. ed. ThompsonW. R. (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

62

Steppat D. Castro Herrero L. Esser F. (2022). Selective exposure in different political information environments–how media fragmentation and polarization shape congruent news use. Eur. J. Commun.37, 82–102. doi: 10.1177/02673231211012141

63

Wijffels J. Straka M. Straková J. (2018). Package ‘udpipe’. Available at: https://cran.microsoft.com/snapshot/2018-06-12/web/packages/udpipe/udpipe.pdf (Accessed on March 1, 2021).

64

Wike R. Fetterolf J. (2021). Global public opinion in an era of democratic anxiety. Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/12/07/global-public-opinion-in-an-era-of-democratic-anxiety/

65

Wike R. Schumacher S. (2020). Democratic rights popular globally but commitment to them not always strong. Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/02/27/democratic-rights-popular-globally-but-commitment-to-them-not-always-strong/ (Accessed on March 1, 2021).

66

Wike R. Silver L. Fetterolf J. Fagan M. Huang C. Connaughton A. et al . (2021). Freedom, Elections, Voice: How People in Australia and the UK Define Democracy. Accessed at: https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2021/12/PG_2021.12.07_UK-Australia_FINAL.pdf

67

Wüest B. (2018). Selective attention and the information environment: citizens’ perceptions of political problems in the 2015 Swiss Federal Election Campaign. Swiss Polit. Sci. Rev.24, 464–486. doi: 10.1111/spsr.12325

68

Zaller J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Summary

Keywords

democracy, public opinion, social media, politicians, natural language processing

Citation

Reveilhac M and Morselli D (2024) Augmenting surveys with social media discourse on the workings of democracy from a cross-national perspective. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1385678. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1385678

Received

13 February 2024

Accepted

30 August 2024

Published

17 September 2024

Volume

6 - 2024

Edited by

Nargiz Hajiyeva, Azerbaijan State University of Economics, Azerbaijan

Reviewed by

Giovanna Campani, University of Florence, Italy

Sergiu Miscoiu, Babeș-Bolyai University, Romania

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Reveilhac and Morselli.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maud Reveilhac, m.reveilhac@ikmz.uzh.ch

†ORCID: Maud Reveilhac, orcid.org/0000-0001-9769-6830

Davide Morselli, orcid.org/0000-0002-1490-9691

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.