- Department of Political Science, University of Iceland, Reykjavik, Iceland

This article analyses the causal factors behind the Brexit vote, aiming to contribute to the literature on European disintegration. It addresses how, amidst external factors such as the EU debt crisis and the 2015 refugee crisis, pre-existing ideological forces deeply ingrained in a society can surface and steer a country's trajectory in relation to European integration. Employing a rigorous process-tracing design, it highlights the forces that led to the referendum and its outcome, identifying key patterns that can be extrapolated to comparable cases within the field of EU integration theory. The analysis operates at two levels: it scrutinizes the constraints faced by Cameron's government in the lead-up to the vote, and it probes the British electorate's attitude toward EU and how it was influenced by the Leave campaign. The study draws from an empirical case to identify some of the patterns of this ongoing political process.

1 Introduction

The idea that European integration could be reversed gained traction in the last decade, fuelled by events such as the 2009 European debt crisis, the 2015 refugee crisis, and the rise of openly Eurosceptic political parties in some member states. Krastev (2012) highlighted the conflict between strengthening European political institutions and increasing democratic participation of citizens as the main challenge faced by the European Union today. Furthermore, Brexit demonstrated that the dissolution of the EU is a real possibility, emphasizing the need to develop a theory of disintegration as both an outcome and a process (Rosamond, 2016). The debate on differentiated integration became prominent in the 1990s, coinciding with the establishment of the EU, as it became clear that different member states chose varying levels of involvement within the institution (Holzinger and Schimmelfennig, 2012). If we consider the possibility that the union could gradually dissolve through the secession of member states, it is essential for a theory of disintegration to analyze the causes of Brexit, which would help identify similar symptoms in other European countries. This disintegration process is influenced by a combination of structural factors, which are prominent in the institutionalist approach (Vollaard, 2014), and ideological or agency-centered factors, such as the evolution of the British Eurosceptic discourse during the UK's EU membership (Hobolt, 2016; Kostakopoulou, 2017). The question of agency and identity is also crucial when examining structural factors, which are the tangible political and economic elements shaping the Brexit process. The issue of agency resurfaces as the two main concerns addressed by the Leave campaign—intra-European migration and asylum seekers—are related to themes of social inequality and human rights (Frost, 2019). Therefore, to understand the role of these structural factors, it is necessary to first determine British voters' stances on these issues and how they were shaped over time, thus looking at main features the British European policy debate. In the Meditations, Marcus Aurelius noted how a “purple-edged robe [is] just sheep's wool dyed in a bit of blood from a shellfish.” Similarly, structural factors are merely isolated events until an ideologically charged narrative assigns them specific political meanings.

This article attempts to individuate both types of causal factors by looking at the chain of events that started with the 2014 European Elections electoral campaign, thus following an approach already adopted in the study of Brexit (Clarke et al., 2017). It uses a process-tracing design to identify Brexit's causal factors and make broader assumptions about states' behavior in the context of European integration, aiming to formulate a theory of European disintegration. The choice of process tracing derives from how this method allows the identification of threshold points in the analysis of the causal mechanism, thus highlighting which conditions were necessary for each step to take place; specifically, this work is interested in causation within the boundaries of the case addressed, namely the decision for the Brexit referendum. In order to figure out what Brexit tells us about this, the paper assesses whether it can be understood as a rational decision. This aim is achieved by testing two rival hypotheses: rationalist and constructivist. The rationalist one emphasizes the aspect of utility maximization, defined as a choice taken to maximize the utility function of the actors involved (Rosefielde, 2016; Vasilopoulou, 2016).

On the other hand, the constructivist hypothesis revolves around ideational aspects such as the notions of sovereignty, identity and independence (Fossum, 2019). The paper proposes rhetorical entrapment (Glanville, 2019) as a way of bridging the two perspectives, arguing how Brexit was the consequence of a change in the way EU membership was perceived by British society. Accordingly, and with respect to the agency-and-structure duality mentioned earlier, the position of this work is oriented toward an ideational explanation.

The main aim of the article is to develop a comprehensive framework for the analysis of the forces at play in European disintegration. To achieve this, the article meticulously describes the process leading to the Brexit vote, highlighting the interplay between structure and agency from an IR perspective. Following this introduction, the next section presents a thorough review of the existing literature on EU disintegration and Brexit. This section also introduces the two rival hypotheses, defining the constructivist and rationalist perspectives, thereby ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of the study.

Section 3 then presents a critical analysis of the 2010–2016 period leading to the referendum, discussing the main causal factors behind it and addressing the Eurozone crisis and the 2015 refugee crisis, which are considered two of the main structural factors or catalysts of Brexit. This section aims to analyze the extent to which Brexit was caused by structural constraints and a specific ideological environment respectively.

The fourth part analyses how domestic preference formation and intergovernmental bargaining at the EU level played a role in Brexit. It discusses how governmental action is the culmination of several independent decision-making processes. While these processes can be expected to be guided by rational decision-making, their interactions can lead to irrational outcomes, as actors function within a complex framework of forces and interests.

The conclusion of this research not only addresses the ideational forces at play in EU politics and their relevance to the analysis of Brexit on the ideological dimension, but also underscores the practical implications of this understanding. By contributing to the development of a theory of European disintegration, this research offers a prospective application to similar cases, integrating the retrospective understanding of the Brexit vote discussed in the earlier sections.

2 Literature review on EU disintegration and Brexit

This work addresses Brexit both as an outcome and as a process. As an outcome, Brexit is seen here as an instance of disintegration. As a process, it is discussed against the backdrop of the structure-agency debate in International Relations. The ontological divide between structural and ideological approaches within IR theory revolves around whether political phenomena can be better understood as the results of the environment in which political actors operate, or as a product of their choice and free will (Vadrot, 2019). This article draws from the definition elaborated by Alexander Wendt in his early work (Wendt, 1987); the American scholar pointed out how society simultaneously shapes and is shaped by the interactions of the social actors inhabiting it. In a more recent article, Wendt underlined how the constructivist approach does not reject the notion of social structures determining states' behavior. However, in contrast with the neorealist approach, it adopts a broader definition of structure, including practices, knowledge and norms among the constitutive elements of the international system (Wendt, 1995). In the context of EU studies, constructivism understands integration as a change in a state's collective identities and political culture. The belief that ideational factors determine national preferences enables us to account for choices at odds with the existing economic and political interests of a state, interests on which research programs grounded in a rationalist ontology are usually focused (Risse, 2009). In view of this, the purpose of this article is not to determine the primacy of ideological or structural causal factors, but rather to discuss how such factors have influenced the decision-making process of actors deeply embedded in pre-existing and mutable cultural fabrics. This analysis is necessary as understanding these factors and how they exercise their influence is central to draft a theory of disintegration, which can then be used to infer the future development of the EU.

This work aims to discuss whether the impact of these forces increased due to the external factors discussed earlier. The guiding assumption is that Eurosceptic positions found a broad audience in the country, gradually leading political actors (who had previously been open to a certain degree of European integration) to switch their preferences; this, in turn, led to the normalization of the nationalistic positions that caused the referendum.

Due to the qualitative nature of the research questions, the article will use the outcome-explaining variant of process tracing. This choice is motivated by the method's empirical rigor and its capacity to track complex causal processes (Waldner, 2015). In this case, the analysis is based on two rival hypotheses, i.e., rationalist and constructivist. Precisely because Brexit appears to be driven to a significant extent by ideational factors (as captured in the constructivist hypothesis), it is necessary to opt for the outcome-explaining variant in order to consider all possible causes without being limited to one single theoretical framework (Beach and Pedersen, 2011). Even though the hypotheses are derived from prominent theoretical perspectives (rationalism and constructivism), the primary purpose of this work is not to test the validity of a given theory or to elaborate a model applicable to other instances. Instead, it proposes an explanation of Brexit, thus offering a retrospective understanding of the process leading to it, while also addressing its significance for developing a theory of European disintegration, thus allowing a prospective application to other member states.

2.1 Rationalist-exogenous

Regarding the relationship between structure and agency, understanding European institutions as the product of interactions between social actors allows for some considerations on the nature of both. This work distinguishes between states and institutions and the social reality that generated them (Koslowski, 1999); the former are structures created by pre-existing actors, and the latter is a continuum composed of actors, norms, and practices. Over time, social structures emerge, are shaped, and change according to the repetition of certain practices and the internalization of specific behavioral norms.

This article discusses how structural and ideological factors influence each other. It starts from a concrete case to examine how member states' economic and strategic interests tie themselves to the intrinsic properties of the practices and norms existing at a given moment. As best portrayed by Gifford (2016), one of the main causal factors of Brexit was the United Kingdom's model of political economy, which is characterized by a strong executive and treasury; hence, the country's opposition to the European Monetary Union (EMU), a stance shared by both Conservative and Labor governments. After the 2009 European debt crisis, these pre-existing tensions played a central role in British political debate, with several politicians promoting the conceptualization of the UK as an international financial player whose sovereignty was restrained by unelected European bureaucrats. This rhetoric was also favored by the country's weakness during the Eurozone crisis, which becomes evident when looking at the Treaty on Stability, Coordination, and Governance negotiation process in the Economic and Monetary Union (Thompson, 2017). This example shows how a government faced with structural constraints, understood both as those coming from being part of a supranational organization and as external crises, might opt for an apparently disadvantageous course of action due to the influence of consolidated political practices and an ideologically charged discourse. In the United Kingdom's case, these practices coincided with the defense of its sovereignty and the need to maintain a higher degree of independence from the EU's regulatory structures. This behavior of the UK's government, which for the purpose of this work is seen as the leading actor behind Brexit alongside the pro-Leave forces, is in line with the core assumption of rational choice theory, which states that actors will try to maximize their utility functions while being subject to external constraints (Pollack, 2007).

2.2 Constructivist-endogenous

In the context of the relations between London and Brussels, the British government and, in particular, the Conservative party were affected by the need to reconcile EU membership and the need to act in line with a narrative that saw the UK in a vulnerable position due to financial instability and migrants, both elements associated with the above-mentioned membership. These constraints are of an ideological nature, and the impact they had in the Brexit process, and hence on European disintegration, can be analyzed through rhetorical entrapment. European studies generally employ this concept to analyze the EU's attitude toward enlargement (Schimmelfennig, 2009). It can be summarized as the tendency for a political actor to conform to a specific behavioral pattern, against its long-term interests, since acting differently would contrast with positions and norms previously promoted by the same actor for rhetorical purposes. These preferences are dictated by the need to reach short-term interests, often of an electoral nature, and to act according to an image previously crafted by the political actors. In this case, the British government's propensity to antagonize the EU in the field of economic policy, combined with the Eurozone crisis, led to the escalation of pre-existing contrasts. This work adopts an inclusive ontological framework (Kauppi, 2010), capable of reconciling an exogenous formal logic of action with an endogenous substantive one. According to this view, actors follow a logic of action based on accumulating valuable resources, a logic shared by different institutions and social spheres; actors' values and practices are determined by the framework in which they operate, thus endogenously (Kauppi, 2018, p. 38). In the context of EU studies, the exogenous formal logic of action is driven by a member state's objectives, e.g., improving its economic position and its influence. The endogenous substantive one, on the other hand, is driven by the way the goals mentioned above are pursued according to ideational factors.

The following section explores the context preceding the referendum to analyze the actors involved and the ideological forces affecting them. It also relies on the concept of international socialization. The term indicates the mechanism by which actors adopt the norms of a given community, “switching from a logic of consequences to a logic of appropriateness” (Checkel, 2015, p. 804). In the case of Brexit and regarding European disintegration in general, it might be more accurate to speak of reverse socialization. In line with this understanding of the concept, this article refers to a process involving states moving from a course of action based on a rational calculation of costs and benefits to one they consider ideologically appropriate. However, the process distinguishes itself from conventional instances of socialization because this change in preferences did not happen to comply with the rules of external institutions. The hypothesis of this study is that this was caused by a shared sense of national identity and a deep-routed diffidence toward external interferences, which led a substantial part of the political class and the British electorate to consider it necessary to leave the European Union. Both these causal factors derive, in turn, from the long-standing features of the British political debate on EU integration, which have been discussed at length by a consolidated literature.

Accordingly, this work argues that Brexit results from a clash between two ideological forces: the EU's normative influence and that of Eurosceptic parties and actors within the UK. A distinction can be made between two types of indirect normative power: the concept of socialization discussed above and emulation. The latter refers to the process by which the practices of a given actor are judged desirable and repeated by others (Lenz, 2013). Both effects have been explored in the context of European studies (Börzel and Risse, 2012) to provide a constructivist explanation of integration. However, in the UK, both processes have been hindered by diametrically opposed ideological forces throughout the country's history in the EU.

3 A critical analysis of the pre-referendum period (2010–2016)

The following section has a 2-fold objective. Firstly, it aims to uncover the reasons behind the UK government's decision to hold the 2016 Referendum. Second, it examines the factors that influenced the British population's choice in the vote. This analysis of the British political debate is crucial for understanding the causal mechanism that led to the referendum, helping us identify the causal links around which our analysis is structured. It begins by identifying the causes behind the Brexit vote and then proceeds to analyze how these factors contributed to the outcome. The analysis considers the interplay between structural and ideological factors. Additionally, it assesses how existing ideological forces were affected by the external socio-political context. In this context, it is important to address the two major crises that impacted the EU in the years leading up to the referendum: the Eurozone debt crisis and the 2015 refugee crisis. Both of these have been identified as key drivers in the rise of Euroscepticism in several member states (Taggart and Szczerbiak, 2018).

3.1 Brexit's causal factors

The refugee and economic crises are intertwined with two other structural factors, which had significant ideational consequences on the political debate preceding the Referendum. The first is intra-European immigration to the United Kingdom, mainly the migration flows that followed the EU's enlargement in the early 2000s. The second one is the crisis in the neoliberal system that characterized the years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The link between the first factor and the Referendum's outcome emerges particularly from an analysis of the Leave campaign's main arguments (Vasilopoulou, 2016). This characterization of immigrants as an obstacle to the economic wellbeing of British citizens has been associated by Bailey (2018) with a broader crisis of the British capitalist system, leading to the dilemma of aspiring simultaneously to membership in the single market and maintaining control over migration policies.

3.1.1 Evidence for the constructivist hypothesis

On a cultural level, looking at the UK's attitude toward European integration throughout its membership may be helpful. In 1975, 2 years after the country entered the European Economic Community (EEC), the first referendum on membership saw a clear victory for the Remain side. In the almost two decades of Conservative governments that followed, during which the EU was founded by the Maastricht Treaty, the UK's membership was not questioned again. However, the country remained outside any project concerning further monetary integration. In the Blair and Brown years, despite the presence of governments that were more favorable to the EU, the British public's attitudes toward the EU remained rather tepid (Allen, 2013).

Overall, while the country's governments have held various positions concerning Europe, the population has never been particularly enthusiastic about European integration compared to other large member states, as shown by an empirical macro analysis by Anderson and Hecht (2018). In the 2010s, the public perception of the EU further deteriorated, mainly due to the considerable extension of Brussels' competencies after the Lisbon Treaty. Moreover, since 2010, the UK saw a resurgence of the Conservative party, historically characterized by an antagonistic stance toward EU integration, albeit at the same time generally supportive of the economic aspects of EU integration understood as a better opportunity for trade. This stance is evident from Cameron's pledge to renegotiate the terms of Britain's relationship with the EU and to validate the negotiation's outcomes through a referendum (Copsey and Haughton, 2014). However, leaving the EU was arguably not the goal of the Cameron cabinet, as it can be inferred from the government's pro-Remain position before the 2016 vote (HM Government, 2016).

There are at least three elements that can explain this contradiction. The first is rhetorical entrapment: For decades, the EU had been portrayed as an obstacle to British sovereignty and used as a scapegoat in the context of migration and economic policies. This view was shared by Cameron's party and a considerable portion of the British press (Allen, 2013, p. 118). As a result, the political costs of canceling the referendum seemed too high to be considered. The second factor is the miscalculation of Britain's position in the negotiations with the other member states before and after the referendum. In hindsight, it might have been beneficial for the EU to adopt a more conciliatory stance toward the United Kingdom, but it's important to consider how Britain was already subject to unique and advantageous conditions compared to the other member states (Glencross, 2015). Lastly, it might be argued that both the UK (here understood as the actors behind the Leave campaign) and the EU failed to grasp the ideological forces asserting themselves in the years immediately preceding the referendum. The emergence and the impact of right-wing populism, nativism, and widespread anti-elitist stances were not fully grasped by mainstream political parties before Brexit. These ideological forces contributed to shaping both the results of the referendum and the political debate preceding it (Iakhnis et al., 2018). Cameron's government may have underestimated this changing zeitgeist due to the successes achieved in the 2014 Scottish Independence referendum and the 2015 General Elections.

A similar phenomenon, namely, a political leader binding the future of his government to a referendum, can be found in the case of the 2016 Italian constitutional referendum. Emboldened by his party's results in the 2014 European Elections, Italian PM Matteo Renzi staked his political capital in an attempt to pass the reform mentioned above, the failure of which led to his resignation (Ceccarini and Bordignon, 2017). Alongside Donald Trump's victory in the 2016 Presidential elections, Brexit can be studied as a turning point for the assertion of a new type of political discourse. The three factors listed above explain Cameron's excessive confidence in the outcomes of both the negotiations and the referendum. Concerning the question of why the British PM deemed it necessary to prioritize the issue of EU membership, the answer may lie in a combination of electoral calculation and party politics. Specifically, Cameron's goals were to avoid losing votes to the UKIP, and to resolve what he perceived as a weakness and a point of contention within his party (Smith, 2018). He attempted to achieve both goals by moving toward more Eurosceptic positions, even though moving toward these positions may have increased the electorate's Euroscepticism.

In the context of the United Kingdom's complex relationship with EU institutions, it's important to consider the country's history, particularly its role as the center of the world's largest colonial empire. Even after the decline of the British Empire, the UK maintained a special relationship with most former colonies, primarily through the Commonwealth. However, in geopolitical terms, the main factor influencing the British attitude toward EU integration might be its ties with another former colony, the United States. The special relationship between the US and the UK, strengthened through two world wars and the common threat of the Iron Curtain, appears to have had an impact that extends beyond economic, military, and strategic levels, influencing the cultural identity of the UK (Startin, 2015). Perhaps, after losing its empire, the country managed to uphold its sense of importance by positioning itself as a partner in the American one.

3.1.2 Evidence for the rationalist hypothesis

However, the ideational factors discussed above were not sufficient to prevent the UK from joining the EEC, and even the first failed attempt to leave it through a referendum was motivated by the Labor Party's skepticism toward the Community's economic stance, rather than by a fear of losing international influence (Evans, 2018). In the following years, alongside the increasing influence of European institutions, the issue of sovereignty gradually assumed a central position in the debate regarding EU membership. Despite the reluctance shown by the Thatcher government, the UK acceded to the Maastricht Treaty. This choice inevitably reinforced the pre-existing Eurosceptic tendencies shared by part of the British population. Startin lists two more external events that further strengthened these attitudes. The first one is the 2004 EU enlargement, which led to the perception that an increasing flow of migrants from the new member states would have a catastrophic impact on the British labor market. The second one is the 2007 global recession; the EU's unprecedented role in responding to the crisis made it a target for those already opposing European integration. These external events also reinforced the ideological forces mentioned above due to the role played by mass media. While it is challenging to determine to what extent media shapes people's preferences, the literature has already pointed out the role of British tabloids in shaping media discourse by portraying the EU as a center of interests in contrast with the United Kingdom (Usherwood and Startin, 2013).

Alongside this representation of the EU as a non-democratic institution, far from the interests of British citizens, another cornerstone of the Leave campaign was the issue of uncontrolled immigration to the United Kingdom. The attempt to portray immigration as a threat emerges from an analysis of the campaign's official sources (Zappettini, 2019), the claims of several political exponents, and from how part of the press approached the theme. The tone of the discourse adopted by British tabloids may be summarized by mentioning how they were admonished by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ENRI) for how they addressed the topic of migrants (Rzepnikowska, 2019). This narrative arguably had a significant effect on the working class, already impoverished by the dismantling of the welfare state since the 1980s. In turn, it led some population strata to identify the cause of their malaise in the increasing number of foreigners and, consequently, in the EU, which was seen as the driving force behind these migratory phenomena. This process led to a vicious circle in which tabloids offered arguably racist content to increase their sales; by doing so, they strengthened the pre-existing concerns of the public opinion toward foreigners, which led the public to expect more of the same contents. Against this background, it is hardly surprising that the actors involved in the Leave campaign exploited this issue to influence the referendum's outcomes. As highlighted by Zappettini, the campaign succeeded in offering an interpretation of reality based on the following causal chain: EU membership was the cause, or at least a determining factor, behind the presence of immigrants in the UK; in turn, these immigrants are a threat to the job market, to the welfare system, and domestic security. Although these claims are highly questionable, the Leave campaign had the advantage of exploiting ideas already rooted in a part of the public opinion, whereas the Remain side had the more difficult task of disproving them. In the broader scope of this article, these dynamics can be seen as preliminary to disintegrative events, inasmuch as it can be expected that the actors interested in reversing European integration will resort to similar arguments.

Two macro-areas are particularly interesting when looking at signs of malaise in a state's EU membership: the first concerns the economy, and the second security. Satnam and McGeever (2018) have identified two predominant and contrasting narratives in the Leave campaign: a sense of nostalgia for the past, traceable to Britain's imperial history, and the assumption that the United Kingdom should isolate itself from an increasingly globalized world. These two narratives can be traced back to two underlying ideas or fears. The first is that the UK economy is threatened by globalization, represented by the EU, which limits the potential of the local industry and imports workers from outside. The second is that migrants pose a threat to national security. The terrorist attacks that happened in Europe in the years immediately preceding the referendum contributed to fueling this fear; attacks that were understood, at least by part of the public opinion, as a direct consequence of the refugee crisis that followed the Syrian Civil War.

3.2 The path to disintegration

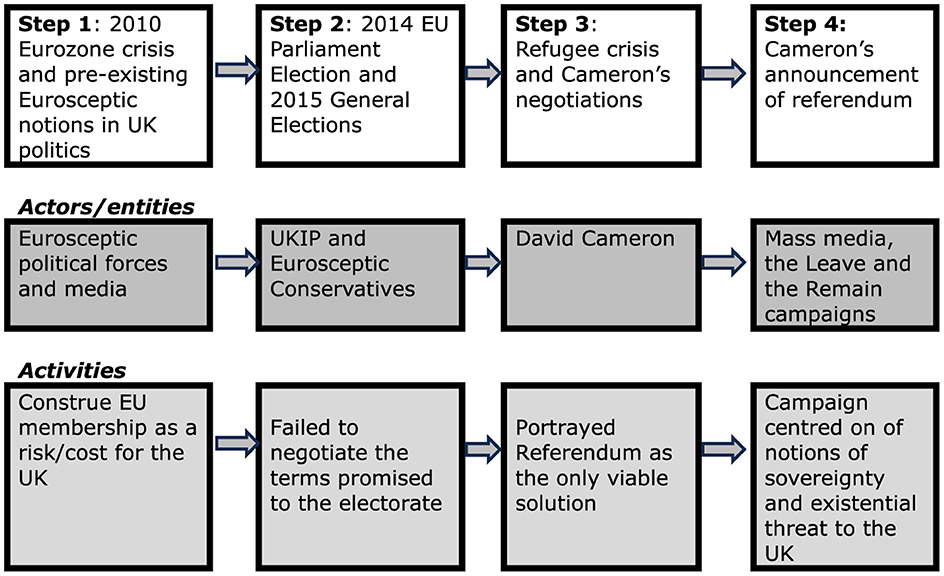

Until now, we have examined the main factors that led to the referendum and its outcomes individually. In the following section, we will look at how these factors combined over time to form a traceable process, which can then be applied to the broader issue of EU disintegration. To do this, we need to trace the period before the referendum on the United Kingdom's membership in the European Union and highlight how the ideological forces opposing integration evolved and interacted with the structural factors discussed earlier (see Figure 1).

The years leading up to Brexit were characterized by a combination of the following elements: a fertile ideological environment, multiple external crises, and individuals or groups seeking to exploit these crises to reinforce existing ideological forces. In this context, Cameron's decision to hold the referendum can be seen as an effort to win over moderately Eurosceptic voters, who had shown support for Nigel Farage's UKIP in the 2014 European Elections, and to solidify his leadership within the Conservative party. As part of this strategy, Cameron took moderately Eurosceptic positions to avoid alienating these same voters. Not holding the referendum could have led to electoral failure for the Tories and a loss of legitimacy for Cameron's leadership. However, a victory for the Leave side would have had similar consequences for the Cabinet and the Conservative leadership, suggesting that the Prime Minister may not have anticipated this outcome. Cameron's optimism can be attributed to two reasons.

After Brexit, any leader faced with the choice between holding a membership referendum or risking poor performance in an election will need to consider the consequences of the British vote. However, when Cameron agreed to the referendum, there was little precedent for a state leaving the EU. The second reason can be attributed to Cameron's understanding of British public opinion. Following the vote on Scotland's independence, the Prime Minister might have assumed that public opinion would again support the status quo. This assumption would align with the Remain campaign's rhetoric, which emphasized the potentially disastrous consequences of leaving the EU (Jessop, 2017).

Cameron initiated the referendum with the hopes that it would fail and expecting it to fail. In a speech at Bloomberg, the Prime Minister outlined three major challenges for the EU: a crisis in the Eurozone, a crisis in competitiveness, and a lack of democracy in European institutions. Cameron's speech reflected a Eurosceptic stance, influenced by the political climate following the European banking crisis. The main message was that while it would be preferable for the UK to stay in the EU, this decision should be made through a referendum, after negotiating improved membership terms.

The speech can be interpreted in different ways: as a warning to the EU in the upcoming negotiations, as a way to maintain control over Eurosceptic factions within the Conservative Party, and as reassurance for moderately Eurosceptic voters. Following the 2015 General Elections, the British PM had to balance his efforts to reach a deal with the EU and project a successful image of the negotiations, while facing pressure from those who would later form the Leave campaign if the deal failed. However, the strategy to contrast Euroscepticism with soft Euroscepticism was ineffective. It's worth considering whether the outcomes of the negotiations could have been different if the EU had taken the risk of Brexit more seriously. However, agreeing to Cameron's demands would have had two significant costs for EU leaders. Firstly, it would have been hard to justify a similar approach to their own electorates, with the risk of favoring Eurosceptic parties within their countries. Secondly, a perceived weakness of the EU could have hastened the disintegration process and weakened the European position in future negotiations.

In November 2015, a letter to Donald Tusk reiterated the three points mentioned in the speech and asked for a guarantee that non-Eurozone countries cannot be financially liable for operations aimed at supporting the Euro. Additionally, it centered on the idea that the relationship between Eurozone and non-Eurozone states should be fairer. Concerning competitiveness, the British Prime Minister asked to decrease the level of regulations.

Regarding sovereignty, Cameron demanded that the United Kingdom be exempted from working toward a closer union, a more significant application of the subsidiarity principle, and an increase in the powers of national parliaments. However, this demand may appear to conflict with the EU's institutional architecture. Cameron added a fourth demand to the three points already present in Bloomberg's speech: the request to limit immigration from other member states (Weiss and Blockmans, 2016).

Tusk's response in December 2015 used optimistic tones regarding the negotiation's outcomes and tried to reconcile Cameron's demands and the position of the other member states. It concluded by remarking on how the UK will continue to play a central role in the development of the EU. The President's response reflected the European Council's willingness to grant moderate and mostly symbolic concessions to the UK, while still having a strong interest in the UK remaining in the EU (Schimmelfennig, 2018). This course of action is likely due to a wrong assessment of the likelihood of Brexit. This assessment was influenced by the substantial benefits of membership for the United Kingdom, as mentioned by Cameron himself, and the fact that no state had ever left the EU before. It is debatable to what extent the EU's response would have been different if the prospect of the UK leaving had appeared more credible. Perhaps the nature of the requests put forward by the most Eurosceptic fringes of the UK Conservative and UK Independence Party was incompatible with the EU's founding principles, making any agreement impossible, especially regarding the circulation of people.

In the February 2016 speech in which he announced the referendum date, Cameron remarked on how Britain would be stronger as an EU member while reiterating the need to reform European institutions from the inside. However, this moderate approach failed to convince the British electorate. It seems that Cameron overestimated both public opinion and the mass media's support for the EU.

Up to this point, the paper mapped the elements that combined to cause the referendum and influence its result. The following section discusses how these factors influenced both voters' preferences and the government's policies and which lessons can be drawn from Brexit with respect to the behavior of a state about to leave the EU.

4 Discussion on the lessons of Brexit for a theory of EU disintegration

The analysis of the causal mechanism so far suggests that a group of actors, including members of the mass media and the most Eurosceptic exponents of the UKIP and the Conservative party, successfully influenced the British government and the country's population over a few years. They achieved this through two interconnected activities, one related to the internal sphere and one to the external sphere.

Regarding the internal sphere, the main factor discussed here is the pressure political actors applied to Cameron's cabinet to bring about a referendum. The same Tory MPs that later formed the Leave campaign put increasing pressure on Cameron to pass a Referendum Bill, starting as early as 2011 and again in 2013 (Wintour and Watt, 2013). Cameron was also constrained by the competition of another party, i.e., UKIP, which could earn the support of those voters who were disappointed with the Conservatives' EU policies (Watt et al., 2013). Due to the first-past-the-post voting system implemented in the UK, Farage's party never managed to have more than one MP in the House of Commons. However, the UKIP's rise threatened Cameron for two reasons. Firstly, it might erode the party's majority by splitting the Conservative vote and thus favoring Labor candidates; secondly, for the risk of those dissatisfied with Cameron's leadership defecting to UKIP (Hunt, 2014).

On the external level, it is noteworthy that some mass media framed EU membership according to a specific political agenda, tying it with uncontrolled immigration, high costs, and lack of democratic representation. While the direct effect of this phenomenon on the referendum's results is challenging to measure, it appears that the mass media served as an echo chamber for the Leave campaign (Barnett, 2016). This phenomenon can be explained as a combination of ideologically driven interests and an attempt to provide their audiences with sensationalist content capable of matching the arguments and languages adopted by political actors. This process might have led to a vicious cycle in which campaigners disregard factual information (Barnett, 2016). Because of the interplay discussed above between economic interest and ideological consideration, the media conformed to this approach, thus enabling political actors to disregard reality further. The tendency to promote sensationalistic narratives was not limited to the Leave side, as we can observe a general shift in the political debate toward the employment of exaggerated claims and oversimplification (Beckett, 2016). In this context, it is unsurprising how voters with lower educational levels were more vulnerable to the arguments and strategies adopted by the Leave campaign, as pointed out by an aggregate-level analysis of the vote's results (Goodwin and Heath, 2016).

The widespread exposure to and influence of overly critical views on the EU within the public had an impact on the power dynamics within the Conservative party. Despite not being particularly Eurosceptic himself, Cameron had gained considerable experience in managing the more extreme elements of his party over the years. As he successfully held the party's leadership for more than a decade and won two General Elections, it could be argued that the former Prime Minister was confident in his ability to reconcile his approach to the EU with the more extreme views held by some of his MPs and voters. In this context, granting a referendum should not be seen as solely a response to external pressures faced by Cameron. Instead, it appears to be in line with Cameron's strategic approach, which had been effective up to that point (Hayton, 2018).

Considering these deep divisions within the Conservative party concerning European integration, looking at this phenomenon as an issue of party leadership and internal politics rather than a foreign policy problem may be helpful. However, to completely exclude from the causal factors those structural aspects typically associated with states' decision-making process in IR theory would be a mistake since considerations of a similar nature partly dictated the preferences of those who supported the Leave front.

One of the main arguments of those supporting leave was that the UK would have been in a better position by defining its trade agreements with the European bloc and with the rest of the world autonomously, without the inevitable limits to sovereignty resulting from EU membership and without the risk of having to use its economic resources to assist other states. Such an approach existed, but it was maintained only by a relatively limited section of the political class. However, due to the party logic set out above, the influence of this vision was amplified; due to external structural circumstances, the debt crisis and the Syrian civil war, Cameron chose to adopt a suboptimal strategy and compromise against his interests, starting the process that culminated in the referendum. This contrast between a given actor's preferences and their decisions leaves us to reflect on how a state's choices are inevitably the product of the balance between different forces with conflicting interests and objectives. In other words, Brexit results from several actors prioritizing their interests over the state's. The ideologization of structural factors, understood here as the ability to organize external events in a convincing narrative built upon pre-existing notions of sovereignty and identity, proved particularly effective for the Leave campaign. This success is due to the Leave campaign's capacity to present the referendum as the only possibility to influence what had been presented as a system, the European Union, detached from the democratic process and controlled by distant bureaucratic and political elites.

It is disconcerting to note that a significant number of voters made decisions based on incomplete or factually incorrect information. The most glaring example is the claim that post-Brexit, the UK would be able to allocate £350 million a week to the NHS, a promise swiftly disowned by Nigel Farage after the vote (Reid, 2019). This aligns with the rational irrationality model, where individuals maintain biased beliefs, even to the point of going against their own interests, due to the psychological costs of challenging their pre-existing ideas (Caplan, 2001).

In the case of Brexit, a significant portion of the voters found that the ideas presented by the Leave campaign aligned with their worldview. In a context characterized by economic instability, increasing ethnic diversity, and the threat of terrorism, the message that Britain could somehow revert to its glorious past by leaving the EU resonated with the electorate. Faced with the costs associated with obtaining information on European and International law, the micro and macro-economic consequences of EU membership, and the real causes and effects of migration, voters decided to endorse the simplified version of reality offered by the Leave campaign. They did so because the campaign was able to leverage real problems, namely the decline of the middle class, using effective communication tools to spread captivating messages. Furthermore, the Leave campaign managed to attract single-issue voters who were particularly sensitive to a specific aspect of the campaign but were uninterested in the ramifications of leaving the EU. In this regard, concerns over immigration were a significant variable in determining voting preferences (Goodwin and Milazzo, 2017). Another possible example of single-issue voting is that of fishermen, overwhelmingly in favor of Leave due to the possibility that this would help the British fishing industry, regardless of the overall effects of the negotiations on the country's economy.

Considering the above, these three elements should be included among the referendum's causal factors and understood as necessary prerequisites to the outcome researched in this work. Firstly, Cameron's decision to pursue a strategy already adopted in the past, a strategy relying on keeping the Eurosceptic fringes of his party under control by adopting a slightly toned-down version of their arguments while contemporarily appealing to the potential benefits of EU integration. Secondly, the Leave campaign's ability to present the referendum as a last resort to influence a phenomenon otherwise beyond the reach of ordinary people. Lastly, the state of deliberate and selective ignorance on the part of some of the electorate, a state reinforced by a persuasive, albeit often groundless and simplistic, campaign. These elements combined to determine the foreign policy of one of the largest states in the world, leading to a choice that can only be explained by the interaction between structural and ideological causal factors.

Moreover, it can be concluded that Leave voters were more motivated to vote. This greater propensity to participate in the Referendum is because the campaign had a more significant effect on them since it successfully presented the vote as an opportunity to democratically influence a political issue framed as outside of the voter's control.

One of the mistakes of the Remain campaign was to emphasize that the status quo was the only acceptable option. In other terms, they reinforced the vision of the EU as something inevitable, paradoxically motivating some of the voters to want to affirm their preference against this situation.

Regarding the contrast between the decision to vote Leave and a rational assessment of the consequences, this analysis indicates that voters were not interested in broadening their understanding of the issues related to the vote. Instead, they were swayed by a rhetoric focused on nationalism and economic sovereignty, as promoted by mass media and the Leave campaign. Consequently, voters chose to embrace a narrative that aligned with their preferences, rather than confronting complex issues and overcoming their ideological biases.

5 Conclusion

This paper aimed to contribute to European studies by examining the extent to which Brexit can be attributed to structural or ideological factors. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the process leading to the referendum and its outcome, identifying the main actors, their preferences and actions, and the consequences of their decisions. The study also delves into the role of the UK's government led by Cameron, the mass media, and the British electorate's ideological substratum. The focus is on the period between Cameron's pledge to renegotiate the terms of British membership and the 2016 vote. The analysis of structural factors includes the political and economic situation of the United Kingdom, while the ideological sphere is explored through the identity and preferences of the British voters and political class concerning European integration.

Our research showed how the division between agency and structure may appear challenging to mark in the analysis of this empirical case. In Brexit's case, the three main structural causal factors were the European debt crisis, the migrant crisis, and the fear on the part of some actors that the UK could see its sovereignty reduced by a higher degree of European integration. However, these elements caused the United Kingdom's exit from the EU only due to the previous ideological substratum, characterized by a historically skeptical attitude toward European integration, especially following the eastern enlargement and the increase in the number of immigrants.

Furthermore, the electorate's ideological preferences have been shaped by purposeful actors with a specific agenda, supported by a political discourse relying on rhetoric with low regard for factual information. In other terms, structural factors served as catalysts for a process made possible by pre-existing ideological factors and interests built on cultural and emotional elements.

The theoretical and prospective value of these findings lies in how they can be used to assess the likelihood of a state leaving the EU by verifying whether the following factors are present: a pre-existing ideological background centered around the notion of sovereignty, the presence of political forces capable of promoting an agenda of disintegration, external structural shocks capable of enhancing the appeal of those ideas for the general population. In the case of Brexit, those shocks were the debt crisis, which resonated with the idea that the UK should not be responsible for the financial difficulties of other member states, and the migrant crisis, which was exploited by the Leave campaign by relying on pre-existing mistrust toward foreign nationals living in the UK.

Moreover, the most dangerous consequence of Brexit for the EU is that the catastrophic scenarios envisioned by the Remain campaign have remained mostly unrealized, thus showing how European integration is a potentially reversible process. However, it must also be noted how the UK was in a relatively privileged position due to its economic and diplomatic weight and the fact that the country remained outside the Eurozone. Overall, European disintegration, not unlike European integration, is a complex process influenced by a combination of structural and ideological factors. The only way to predict its trajectory is to identify both possible future external shocks and the already existing ideological forces that might be strengthened by them while simultaneously keeping the actors that might benefit from disintegration under control.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VO: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. VO's research for this article was funded by a Doctoral Student Grant of the Icelandic Research Fund (IRF; Grant Number 228943-051).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The editor HKH declared a past collaboration with the author MC at the time of review.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, D. (2013). The United Kingdom: towards isolation and a parting of the ways? in The member states of the European Union, eds. S. Bulmer, and C. Lequesne (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/hepl/9780199544837.003.0005

Anderson, C. J., and Hecht, J. D. (2018). The preference for Europe: Public opinion about European integration since 1952. Eur. Union Polit. 19, 617–638. doi: 10.1177/1465116518792306

Bailey, D. J. (2018). Misperceiving matters, again: Stagnating neoliberalism, Brexit and the pathological responses of Britain's political elite. Br. Polit. 13, 48–64. doi: 10.1057/s41293-018-0072-1

Barnett, S. (2016). “How our mainstream media failed democracy,” in EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign, eds. D. Jackson, E. Thorsen, and D. Wring (New York: The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community Bournemouth University).

Beach, D., and Pedersen, R. B. (2011). “What is process-tracing actually tracing? The three variants of process tracing methods and their uses and limitations,” in APSA 2011 Annual Meeting Paper.

Beckett, C. (2016). “Deliberation, distortion and dystopia: the news media and the referendum,” in EU Referendum Analysis 2016: Media, Voters and the Campaign, eds. D. Jackson, E. Thorsen, and D. Wring (New York: The Centre for the Study of Journalism, Culture and Community Bournemouth University).

Börzel, T. A., and Risse, T. (2012). From Europeanisation to diffusion: introduction. West Eur. Polit. 35, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.631310

Caplan, B. (2001). Rational ignorance versus rational irrationality. Kyklos 54, 3–26. doi: 10.1111/1467-6435.00138

Ceccarini, L., and Bordignon, F. (2017). Referendum on Renzi: the 2016 vote on the Italian constitutional revision. South Eur. Soc. Polit. 22, 281–302. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2017.1354421

Checkel, J. T. (2015). International institutions and socialization in Europe: introduction and framework. Int. Organ. 59, 801–826. doi: 10.1017/S0020818305050289

Clarke, H. D., Goodwin, M., and Whiteley, P. (2017). Why Britain voted for Brexit: an individual-level analysis of the 2016 referendum vote. Parliam. Aff. 70, 439–464. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsx005

Copsey, N., and Haughton, T. (2014). Farewell britannia: issue capture and the politics of david cameron's 2013 EU referendum pledge. J. Common Mkt. Stud. 52:74. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12177

Evans, A. (2018). Planning for Brexit: the case of the 1975 referendum. Polit. Q. 89, 127–133. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12412

Fossum, J. E. (2019). Can Brexit improve our understanding of wicked problems? Reflections on policy and political order. Eur. Policy Anal. 5, 99–116. doi: 10.1002/epa2.1065

Frost, M. (2019). “The Ethics of Brexit,” in The Politics of International Political Theory (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 181–198. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-93278-1_10

Gifford, C. (2016). The United Kingdom's eurosceptic political economy. Br J. Polit. Int. Relat. 18, 779–794. doi: 10.1177/1369148116652776

Glanville, L. (2019). The limits of rhetorical entrapment in a post-truth age. Crit. Stud. Secur. 7, 162–165. doi: 10.1080/21624887.2018.1441624

Glencross, A. (2015). Why a British referendum on EU membership will not solve the Europe question. Int. Aff. 91, 303–317. doi: 10.1111/1468-2346.12236

Goodwin, M. J., and Heath, O. (2016). The 2016 referendum, Brexit and the left behind: an aggregate-level analysis of the result. Polit. Q. 87, 323–332. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12285

Goodwin, M. J., and Milazzo, C. (2017). Taking back control? Investigating the role of immigration in the 2016 vote for Brexit. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 19, 450–464. doi: 10.1177/1369148117710799

Hayton, R. (2018). “Brexit and the conservative party,” in Routledge Handbook of the Politics of Brexit. Routledge International Handbooks, eds. P. Diamond, P. Nedergaard, and B. Rosamond (London: Routledge), 157–166. doi: 10.4324/9781315169613-13

HM Government (2016). Why the government believes that voting to remain in the European Union is the best decision for the UK. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/515068/why-the-government-believes-that-voting-to-remain-in-the-european-union-is-the-best-decision-for-the-uk.pdf (accessed May 04, 2021).

Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. J. Eur. Public Policy 23, 1259–1277. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

Holzinger, K., and Schimmelfennig, F. (2012). Differentiated integration in the European Union: many concepts, sparse theory, few data. J. Eur. Public Policy 19, 292–305. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2012.641747

Hunt, A. (2014). UKIP: The story of the UK Independence Party's rise BBC, 21 November 2014. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-21614073 (accessed May 11, 2021).

Iakhnis, E., Rathbun, B., Reifler, J., and Scotto, T. J. (2018). Populist referendum: Was ‘Brexit'an expression of nativist and anti-elitist sentiment? Res. Polit. 5, 1–7. doi: 10.1177/2053168018773964

Jessop, B. (2017). The organic crisis of the British state: putting Brexit in its place. Globalizations 14, 133–141. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2016.1228783

Kauppi, N. (2010). The political ontology of European integration. Compar. Eur. Polit. 8, 19–36. doi: 10.1057/cep.2010.2

Kauppi, N. (2018). Toward a Reflexive Political Sociology of the European Union: Fields, Intellectuals and Politicians. Berlin: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71002-0

Koslowski, R. (1999). A constructivist approach to understanding the European Union as a federal polity. J. Eur. Public Policy 6, 561–578. doi: 10.1080/135017699343478

Kostakopoulou, T. (2017). What fractures political unions? Failed federations, brexit and the importance of political commitment. Eur. Law Rev. 42, 339–352. Available online at: https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/id/eprint/89268/

Krastev, I. (2012). European disintegration? A fraying union. J. Democr. 23, 23–30. doi: 10.1353/jod.2012.0064

Lenz, T. (2013). EU normative power and regionalism: Ideational diffusion and its limits. Coop. Confl. 48, 211–228. doi: 10.1177/0010836713485539

Pollack, M. A. (2007). “Rational choice and EU politics,” in Handbook of European Union Politics, 31–55. doi: 10.4135/9781848607903.n3

Reid, A. (2019). Buses and breaking point: freedom of expression and the ‘Brexit'campaign. Ethical Theory Moral Pract. 22, 623–637. doi: 10.1007/s10677-019-09999-1

Risse, T. (2009). “Social constructivism and European integration,” in European Integration Theory, eds. A. Wiener, and T. Diaz (Oxford: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/hepl/9780199226092.003.0008

Rosamond, B. (2016). Brexit and the problem of European disintegration. J. Contemp. Eur. Res. 12:807. doi: 10.30950/jcer.v12i4.807

Rosefielde, S. (2016). Grexit and Brexit: rational choice, compatibility, and coercive adaptation. Acta Oecon. 66, 77–91. doi: 10.1556/032.2016.66.s1.5

Rzepnikowska, A. (2019). Racism and xenophobia experienced by Polish migrants in the UK before and after Brexit vote. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 45, 61–77. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1451308

Satnam, V., and McGeever, B. (2018). Racism, crisis, brexit. Ethn. Racial Stud. 41, 1802–1819. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2017.1361544

Schimmelfennig, F. (2009). Entrapped again: The way to EU membership negotiations with Turkey. Int. Polit. 46, 413–431. doi: 10.1057/ip.2009.5

Schimmelfennig, F. (2018). Brexit: differentiated disintegration in the European Union. J. Eur. Public Policy 25, 1154–1173. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1467954

Smith, J. (2018). Gambling on Europe: David Cameron and the 2016 referendum. Br. Polit. 13, 1–16. doi: 10.1057/s41293-017-0065-5

Startin, N. (2015). Have we reached a tipping point? The mainstreaming of Euroscepticism in the UK. Int. Polit. Sci. Rev. 36, 311–323. doi: 10.1177/0192512115574126

Taggart, P., and Szczerbiak, A. (2018). Putting Brexit into perspective: the effect of the Eurozone and migration crises and Brexit on Euroscepticism in European states. J. Eur. Public Policy 25, 1194–1214. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1467955

Thompson, H. (2017). Inevitability and contingency: the political economy of Brexit. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 19, 434–449. doi: 10.1177/1369148117710431

Usherwood, S., and Startin, N. (2013). Euroscepticism as a persistent phenomenon. JCMS 51, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2012.02297.x

Vadrot, A. B. (2019). “Knowledge, International Relations and the structure–agency debate: towards the concept of epistemic selectivities,” in The Structural Change of Knowledge and the Future of the Social Sciences (London: Routledge), 61–72. doi: 10.4324/9781315159362-6

Vasilopoulou, S. (2016). UK Euroscepticism and the Brexit referendum. Polit. Q. 87, 219–227. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12258

Vollaard, H. (2014). Explaining European disintegration. JCMS 52, 1142–1159. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12132

Waldner, D. (2015). “What makes process tracing good? Causal mechanisms, causal inference, and the completeness standard in comparative politics,” in Process tracing: From metaphor to analytic tool, eds. A. Bennett, and J.T. Checkel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 126–52. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139858472.008

Watt, N., Wintour, P., and Clark, T. (2013). David Cameron offers olive branch on EU referendum as Ukip soars The Guardian, 14 May 2013. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/may/13/david-cameron-eu-ukip (accessed May 10, 2021).

Weiss, S., and Blockmans, S. (2016). The EU deal to avoid Brexit: Take it or leave. Centre for European Policy Studies. Available online at: https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/eu-deal-avoid-brexit-take-it-or-leave/ (accessed May 10, 2021).

Wendt, A. (1987). The agent-structure problem in international relations theory. Int. Organ. 41, 335–370. doi: 10.1017/S002081830002751X

Wintour, P., and Watt, N. (2013). EU referendum: Cameron snubbed by 114 Tory MPs over Queens' speech The Guardian, 16 May 2013. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2013/may/16/cameron-snubbed-tory-eu-referendum (accessed May 13, 2021).

Keywords: Brexit, EU disintegration, member state politics, United Kingdom, referendum, constructivism

Citation: Orlando V and Conrad M (2024) Agency and structure in the age of European disintegration. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1383485. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1383485

Received: 07 February 2024; Accepted: 25 June 2024;

Published: 09 July 2024.

Edited by:

Maria Sigridur Finnsdottir, University of Victoria, CanadaReviewed by:

Simon Usherwood, The Open University, United KingdomTamas Ziegler, Eötvös Loránd University, Hungary

Copyright © 2024 Orlando and Conrad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vittorio Orlando, dmlvMTRAaGkuaXM=

Vittorio Orlando

Vittorio Orlando Maximilian Conrad

Maximilian Conrad