- 1Technology, Policy and Management, Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands

- 2Media, Technology & Society, Inholland University of Applied Sciences, Hoofddorp, Netherlands

Accountability is considered a cornerstone of public administration and good governance. This study characterizes the relationship between the Dutch Intelligence and Secret Service (“AIVD”) and citizens (represented by parliament, courts, and oversight boards) as a complex actor-forum relationship. We utilize different accountability principles of public administration found in international and Dutch instruments and academic literature to propose workable principles of accountability for the AIVD. These proposed principles of accountability can be summarized as acting within duty, explainability, necessity, proportionality, reporting and record keeping, redress, and continuous independent oversight. Similarly, there are some conditions to support the workability of accountability principles. These conditions may be characterized as productive actor-forum relationships, cooperation, flexibility, value alignment, and learning and improving opportunities.

1 Introduction

Driven by broad debates on the appropriate governance of intelligence and security operations in democratic societies, accountability mechanisms, such as oversight, in many democratic countries have changed considerably in the past decades, affecting in some way privacy and data protection regulations as well as intelligence and security operations (Rekenkamer, 2021).

Accountability in public administration is an essential element for good governance (Aucoin and Heintzman, 2000). For example, the Australian Government has its own Public Governance and Accountability Act, which declares that the government and all its organizations need to meet high standards of accountability, which includes providing meaningful information to the public they serve (Newberry, 2015). Accountability promotes trust and legitimacy of intelligence and security operations (Dommering et al., 2017). Similarly, oversight as an accountability mechanism can contribute to ensuring that all actors are accounted for their actions (MacAskill, 2018).1

The deployment of intelligence and security operations are necessary to protect a country from threats (van Buuren, 2009, p. 2). However, in recent years, the use of technological tools in security and intelligence domains has given attention to concerns regarding privacy safeguards and the need for adequate oversight measures in the intelligence and security domains (Cayford et al., 2018). For instance, in the wake of the Snowden revelations, the European Parliament called Member States, such as the Netherlands, to look closely at the Rule of Law, Fundamental Rights, and European Union Values when assessing the use of technologies for government surveillance, data processing, and sharing with other counterparts (European Parliament, 2014).

Intelligence and security work cannot be treated in isolation because they concern society. In one way or another, citizens may be affected or caught in the sphere of intelligence and security work (Braat et al., 2017; Jaffel and Larsson, 2023, p. 234). Thus, the study of the operations of intelligence and security domains can assist society in providing an understanding of how and why intelligence and security domains operate. Similarly, the study of these domains can assist in promoting accountability principles that can balance the interest of national security and the protection of fundamental rights (Naarttijärvi, 2018; Commissie van Toezicht op de Inlichtingen-en Veiligheidsdiensten, 2021). To guide our study, we have formulated the following research questions:

• RQ1: What common principles of accountability exist in democratic societies?

• RQ2: Why is accountability relevant for national intelligence and secret services?

• RQ3: Which common principles of accountability can be applied to the AIVD?

• RQ4: What are the tensions between different accountability principles when applied to the AIVD?

This study provides two main contributions: it characterizes the relationship between the Dutch Intelligence and Secret Service (“AIVD”) and citizens (represented by parliament, courts, and oversight boards) as an actor-forum relationship. Second, it proposes workable principles of accountability to be implemented among intelligence and security domains.

We have structured this paper into four sections to answer our research questions. Section 3 describes accountability and argues for an actor-forum relationship between the AIVD and citizens represented through parliament, courts, and independent oversight boards. Similarly, this section outlines the benefits of accountability and oversight to society and intelligence and security domains. Section 4 adopts common public service accountability principles to develop workable principles of accountability that can be applied to intelligence and security domains. This section outlines seven principles: acting within duty, explainability, necessity, proportionality, reporting and record keeping, redress, and continuous independent oversight. Similarly, there are some conditions to support the workability of accountability principles. These conditions may be characterized as productive actor-forum relationships, cooperation, flexibility, value alignment, and opportunities for learning and improving. Section 5 discusses our proposed workable principles of accountability in intelligence and security domains as an alternative to deal with AIVD's current struggles regarding satisfying accountability principles. Lastly, Section 6 provides conclusions and possibilities for future empirical research.

2 Methodology

To answer our research questions and elaborate on the proposed principles of accountability in intelligence and security domains, we have combined literature regarding general studies on accountability in public administration and more targeted studies on accountability in intelligence and security domains applied to democratic societies such as the Netherlands. The proposed principles were built considering the added value to national interests and futureproofing with upcoming international frameworks, such as Convention 108+.

The Intelligence and Security Services Act 2017, or in Dutch de Wet van inlichtingen en veiligheidsdiensten 2017 (Wiv 2017), served as a point of reference to focus on two key aspects directly concerning intelligence practitioners: national security and privacy in the digital ecosystem. The selection of sources to develop our workable principles of accountability in the intelligence and security domains was structured into three tiers:

• International instruments, analysis regarding accountability in the intelligence sector.

• Dutch instruments, analysis regarding accountability in the intelligence sector.

• Literature review of accountability principles widely accepted among democratic states.

The proposed workable principles of accountability in intelligence and security domains will be utilized in future empirical research through case studies and semi-structured interviews with Dutch intelligence practitioners to study how they deal with these accountability principles in practice. We have made initial contact with the Dutch AIVD to engage in subsequent research, and they have expressed willingness to collaborate. Thus, focusing on accountability practices in intelligence and security domains, such as the Dutch AIVD, is the most logical course of this research.

3 Section 1. Accountability and oversight in Dutch intelligence and security domains

3.1 Defining accountability

According to Docksey and Propp (2023), accountability can sometimes be understood as responsibility, answerability, controllability, liability, transparency, and a synonym for good governance. The notion of accountability varies in different senses and can be seen by scholars in a narrow and broad approach (van Puyvelde, 2013). For instance, Bovens (2010) describes that there is no consensus regarding accountability and that accountability perceptions or interpretations will vary according to the era, societal roles, organizations' agendas, and political views.

Fest et al. (2022) state that accountability can be regarded as having responsibility. However, they add that accountability also means the implementation of transparency. Equally, Flyverbom (2016) portrays accountability as a process that may be implemented through transparency requirements.

Hood (2010) describes accountability as the duty of an individual or organization to be answerable for their actions. Similarly, van Buuren (2009, p. 3) indicates that accountability may be described as a liability that involves a dynamic of actor-explanation-giving.

The Venice Commission 20072 addresses accountability as taking responsibility for errors and putting matters right. Unlike this understanding, van de Poel et al. links accountability, responsibility, and liability. van de Poel et al. (2012) suggests that accountability may be understood as the moral obligation to account for one's actions; in this sense, the notion of accountability as responsibility or liability is not mutually exclusive.

Furthermore, Cobbe et al. (2023, p. 1187), argue that accountability can be understood as a mechanism. These mechanisms can be institutionalized through oversight boards (Bovens, 2010). Likewise, Korff et al. (2017) and Fox (2007), state that accountability can be materialized by setting up oversight institutions that, in turn, will adopt other accountability mechanisms, such as transparency, to complete the performance of supervisory duties in the light of accountability.

Accountability is applied in different fields, such as climate change, medicine, technology, law, and public administration. For instance, accountability in the medical field is applied as a social responsibility concept where all actors involved have a high degree of responsibility and accountability due to the significant impact of their work on society (Mohammadi et al., 2020). Bagave et al. (2022) argue that accountability applied in human-technology studies requires professionals to explain their decisions when using data or technological tools to support their tasks. This requirement can enable legal consequences on actors to justify their conduct or behavior (Bagave et al., 2022). Docksey and Propp (2023) have established that accountability is also used in the legal field; for example, the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) recognizes accountability as the legal responsibility of data controllers to ensure data quality. Hood (2010) explains that accountability is a central point in public administration. It can be said that accountability in democratic societies supports the Rule of Law, subjecting all government organizations to the same scrutiny standards as the ones applied to citizens, preventing government arbitrariness against citizens (Naarttijärvi, 2019, 2023, p. 48; Cobbe et al., 2020).

3.1.1 Actor-forum relationship

In accountability theory, historically, the actor was understood as the “accounter” and the forum as the “account holder” (Pollitt, 2003). Thus, it can be said that the actor-forum relationship requires at least two parties involved.

Bovens and Wille (2021) understand that in this actor-forum relationship, the actor must justify their conduct. Then, the forum may formulate questions and pass judgment on the actor, leading to potential consequences (Bovens and Wille, 2021). It may be explained as follows: Party “A” (one or more actors) should account (explain and or justify) for a particular task entrusted by party “B” (the forum or forums). Party “B” is considered the “recipient of accountability,” where party “B” has the right to ask questions and demands and can ultimately pass sanctions where appropriate (Durán, 2016).

Similarly, Grant and Keohane identify the actor-forum relationship as a principal-agent relationship,3 stating that this relationship implies a particular obligation on the part of the actor or agent to behave in a certain way (Grant and Keohane, 2005). This type of figure is commonly used or known in Anglo countries where the “principal-agent” relationship arises from a trusted assignment (Wills and Vermeulen, 2011; Durán, 2016). Either connotation would result in the same outcome: requiring the actor or agent to provide an account or to be responsible before their forum or principals.

It is worth noting that it is not feasible for citizens to govern directly. Instead, in democratic societies, citizens elect their representatives and executive government to govern their nation (Aucoin and Heintzman, 2000). Hence, the end recipient to demand accountability is the people -the forum. However, people entrust forum powers to their parliamentarians and executive government to control, question, examine, or pass judgment on other actors entrusted with a particular task or power (Wills and Vermeulen, 2011). The accountability relationship may be illustrated through a recent scandal concerning the Dutch government. The outgoing Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, was caught in one of the major scandals in recent Dutch history: the toeslagenaffaire (see text footnote 3). Rutte's government was held accountable for targeting vulnerable families and falsely accusing them of tax fraud. Rutte and his ministers -the actors- were called by the parliament -the forum- to render an account of the events. The Rutte administration was forced to resign, and the government was obligated to compensate the victims of the toeslagenaffaire.

In light of the above finding, we define accountability as the actor's duty to provide meaningful answers about their actions, which includes explaining and justifying decisions, to the forum. Depending on the context, this duty to account for actions may raise posterior consequences such as political responsibility and or legal liability. We also note that accountability as a big umbrella can include different mechanisms or principles, such as oversight or transparency, to assure good governance in public and private organizations.

3.2 Intelligence and security work

Security work is characterized as defensive, meaning that it is designed to protect national security (van Buuren, 2009, p. 3). The main feature of intelligence work is offensive, characterized by investigations made abroad in the interest of national security. Security work requires intelligence to collect small pieces of information to prevent possible unwanted events threatening national security (Cayford and Pieters, 2018).

Traditionally, national security was seen as a necessity to protect from war. However, in recent years, protecting national security is also concerned with protecting the legal order. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has established that the legal order may be understood as upholding the values of the rule of law, which the European Union has adopted.4 The Dutch government has broadly defined national security as the protection against threats that may jeopardize one or more critical interests of the Dutch state and the legal order that could result in social disruption (Ministerie van Justitie en Veiligheid, 2019).

Protecting the legal order may also be understood as fighting terrorism (Korff et al., 2017; Neumann, 2023, p. 18), which translates to international cooperation among intelligence and security organizations by processing and sharing data to combat common “enemies” (e.g., terrorism, extremism, cybercrime) that threaten European Values and Human Rights (van Puyvelde, 2020). For example, the Dutch government supports data sharing and international cooperation with other intelligence and secret services to combat jihadist terrorism (Belgian Standing Intelligence Agencies Review Committee, 2018, p. 3). These dynamics enable different actors, beyond traditional intelligence and security work, to cooperate and share information -including personal data- internationally (Bigo, 2019). Thus, it may argued that the work of intelligence and secret services has changed from the traditional view of national security and intelligence to protect the nation from war. With new threats, including cyber-attacks on the nations' infrastructures, intelligence and security operations have expanded to international cooperation with other partners. This cooperation includes deploying digital surveillance and sharing processed data to protect the legal order and prevent crime or terrorism (Arnold, 1952; Braat et al., 2017; Bigo, 2019; Jaffel and Larsson, 2023, p. 221).

In the Netherlands, the tasks of the Dutch Intelligence and Secret Service (“AIVD”) include conducting investigations and intelligence analyses against persons or organizations that may represent a threat to the democratic legal order, safety, or other vital interests of the Dutch nation.5 Similarly, they are tasked with security screenings.6 The scope and powers to conduct these investigations and intelligence analysis are governed under their legal framework, the Intelligence and Security Services Act 2017, or in Dutch de Wet van inlichtingen en veiligheidsdiensten 2017 (“Wiv 2017”). The AIVD is legally allowed to process data -including personal data- to protect national security, the legal order, and any other interests of the Dutch nation.7 For example, suppose the AIVD is granted permission to investigate a target suspected of terrorism. In that case, they may request airline passengers' data from Dutch customs to analyze data streams regarding the assigned task. However, the power or scope to conduct these investigations is limited to this specific target. It means that the AIVD cannot -or should not- use these powers to pursue other investigations, such as security clearance assessments regarding other individuals. In essence, the AIVD must not misuse their power to request information for purposes outside their assigned task. Otherwise, the misuse of power can lead to risks such as unlawfully breaching fundamental rights—e.g., the right to privacy.8

Intelligence and security work is a challenging task. Intelligence and security domains face different levels of complexity; every day, they deal with threats that may determine the stability or instability of a nation (Menkveld, 2021). Cayford and Pieters describe intelligence and security work as a difficult puzzle because apparent insignificant pieces of data or information may become significant. In contrast, apparent significant pieces of data or information may become insignificant. For instance, certain protestors may represent a more significant deal than others, leading to tipping points and major events. However, one of the problems that intelligence and security work face in identifying these risks is knowing where the “edge of chaos” lies.9 This point of uncertainty has led intelligence and secret services to favor gathering bulk datasets to fight potential threats.10 At this stage, it must be acknowledged that intelligence and security domains' role -or duty- is to save lives by preventing threats against national security and society (Cayford and Pieters, 2018). Thus, their work is essential because they assist decision-makers in becoming aware of threats and act against them (van Buuren, 2009, p. 5).

3.3 Privacy and data protection caveats

The previous section will inevitably lead us to consider privacy and data protection caveats in the work of intelligence and security domains. In principle, the term privacy can be vague and ambiguous (Solove, 2007, p. 754, 755). For example, the Wiv 2017 only provides us with the meaning of data, personal data, and data processing. However, the Wiv 2017 is unclear and does not define the meaning of privacy.11

Pierucci and Walter, members of the Committee of Convention 108+, have declared that privacy and data protection are fundamental rights that must concern a democratic society living in the digital age. They have stated that these rights need adequate protection and cannot be compromised (Pierucci and Walter, 2020). Pierucci and Walter have stressed that this condition of a fundamental right is also recognized by the United Nations (Resolution 68/167), outlining that privacy and data should not be subject to unlawful or arbitrary surveillance because it violates the right to privacy and undermines a democratic society (Pierucci and Walter, 2020).

Naarttijärvi notes that under Articles 7 and 8 of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights (“the Charter”) and Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (“ECHR” “the Convention”) (Naarttijärvi, 2018), privacy is a concrete recognized fundamental right as well as data protection.12 Zuboff (2019) reflects on the right to privacy, outlining that it entails protecting one's information because privacy belongs to the most intimate sphere of a person. Although privacy, or the right to private life, has been settled by different national and international courts as a fundamental right protected against government intrusion, such as surveillance, the right to privacy is not absolute and is to be measured against other necessities, such as national security (Taylor, 2011).

In the previous section, we acknowledged that the work of security and intelligence domains can be difficult because sometimes they work under information uncertainty, making the case for justifying data processing. However, while acknowledging the necessity to protect the country from national threats, it is appropriate to highlight that collecting bulk datasets by intelligence and security domains is an intrusive method against the right to privacy. Thus, the collection of bulk datasets not only targets criminals or suspects of a crime but also targets innocent civilians who do not threaten national security. In this regard, intelligence and security work needs to be considered from both angles: the one that protects national security from threats and the one that requires due observance of fundamental rights, such as the right to privacy and data protection.

In summary, national security and privacy protection matter. Intelligence practitioners deal with threats to national security daily; they are bound to encounter uncertainties that must be untangled before they start putting puzzles together to protect national security. This challenge creates room for a gray area where intelligence practitioners face tradeoffs and decision-making that must be measured against a dynamic society governed by the rule of law. For instance, times of peace may not require the deployment of special powers that intrude into the right to privacy, while unsettling times may require the exercise of special powers. Not an easy task indeed. However, in democratic societies, these dilemmas warrant addressing accountability and oversight of intelligence and security domains (Naarttijärvi, 2019, p. 40; Hansén, 2023).

3.4 Types of intelligence oversight

Grant and Keohane (2005) identify different accountability mechanisms, such as accountability within organizations, the state, courts, and peer accountability. Accountability may be materialized by introducing oversight to scrutinize the individual's or organization's use of public resources and supervising the use of legal powers or mandates (Wills and Vermeulen, 2011).

According to van Puyvelde, intelligence oversight in democratic nations has adopted different forms, such as implementing institutionalized mechanisms to supervise intelligence and security operations. These institutionalized mechanisms are predominately the legislative, the parliament, and the judiciary (van Puyvelde, 2013). Similarly, independent and objective media, interest groups, and civil society play a role as overseers (Born and Wills, 2012, p. 6). However, their role is restricted due to intrinsic facts surrounding intelligence, such as access and release of classified information (van Puyvelde, 2013).

Oversight mechanisms, such as parliament, judiciary, and independent boards, are also present in European intelligence and security work (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2023, p. 10). For instance, in the Netherlands, the General Intelligence and Security Services (Algemene Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdienst) (AIVD) is governed under different types of oversight: judicial, parliamentary, independent boards, and internal organizational control (Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties, 2023a).

3.4.1 Judicial oversight

The Vienna Commission 2007 has established the authority of courts of law in intelligence oversight to be the key holder of safeguards when intelligence and securities services exercise special powers such as electronic surveillance against individuals or organizations. Similarly, this oversight control by the courts includes the powers to hear complaints and provide sanctions for wrongdoing (see text footnote 2). For instance, in the Netherlands, the courts can hear matters related to national security and deal with disputes between citizens and the AIVD.13

Born and Wills state that intelligence and security services fall under the oversight jurisdiction of courts. The reason is that courts have a duty to administer justice and make the rule of law prevail. Thus, judges have to scrutinize the activities of intelligence and security services (Born and Wills, 2012, p. 13). However, the work of courts has sometimes been restricted by the executive and -parliament- through laws that allow immunity and secrecy in matters related to national security (van Buuren, 2009, p. 4).

3.4.2 Parliamentary oversight

Bochel and Defty (2017, p. 103) state that parliament oversight in intelligence and security domains is significant because it provides public trust and enables legitimacy to intelligence and security services. The oversight duties of parliament toward intelligence and secret services may include conducting budgetary audits, legal and policy compliance audits, providing education programs, investigating complaints, and facilitating information to society (Born and Wills, 2012, p. 11).

Despite having parliament oversight with committees focussing on security and intelligence operations. Parliament oversight has received criticism on the basis that it lacks specialized knowledge and appropriate time to conduct oversight of intelligence and secret services (van Buuren, 2009, p. 4; Hijzen, 2014). For instance, in the Netherlands, traditionally, the parliament had exercised oversight of intelligence and security work (Frissen, 2016). However, Dutch parliamentary oversight has captured criticism among scholars because of being too secretive about intelligence work (de Graaff and Hijzen, 2018). Dutch parliament in the 1970s was characterized as a ritual dance between parliamentarians -the forum- and the secret service -the actors. It was said that parliament was unwilling to supervise the work of intelligence and security operations truly (Hijzen, 2014; Braat, 2016; Gill, 2020). To amend these shortcomings, in recent years, the Dutch government has implemented independent oversight boards besides parliament oversight. In practice, the parliament has broader powers to oversee the functionality of Dutch intelligence and secret services and the legality, effectiveness, and efficiency. Independent oversight boards are only tasked with legality assessments regarding the work of intelligence and secret services (AIVD/MIVD) (Born and Wills, 2012, p. 12).

3.4.3 Independent oversight boards

Different stakeholders have widely accepted independent oversight boards as an accountability mechanism (Bovens and Wille, 2021, p. 856; Docksey and Propp, 2023). For instance, in 1997, the Dutch Parliament acknowledged the need for independent oversight boards parallel to parliamentary oversight. During the Parliamentary sittings 1997–1998, the legislators mentioned the desirability of having a specific board to supervise the legality in which the Dutch intelligence and security services operate (Kamer, 1998). The Parliament considered the importance of balancing the exercise of special powers given to intelligence and security services and protecting fundamental rights. They considered that the use of special powers by the Dutch secret services warranted independent oversight to ensure the legality of intelligence and security operations (Kamer, 1998). The legislator justified the need for independent oversight based on the principle of accountability (Kamer, 1998). Moreover, the reason for introducing independent oversight boards is based on the necessity to protect civilians' fundamental rights from the unwarranted interference of intelligence and security domains (Jansen, 2021).

The Wiv 2017 enables independent oversight boards to supervise the legality of the Dutch AIVD and MIVD operations (Gill, 2020). For instance, Articles 32 and 97 of the Wiv 2017 implement two oversight boards: Toetsingscommissie Inzet Bevoegdheden (TIB) and the Commissie van Toezicht op de Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdiensten (CTIVD), both tasked to conduct legality assessments regarding the operations of the AIVD. The TIB oversees prior intelligence operations, while the CTIVD supervises ongoing and concluded operations of the (AIVD). The mandate of the TIB is to review the lawfulness of operations of the Dutch AIVD. The TIB carries out legality assessments to provide written prior permissions for the AIVD to exercise special powers. The decisions of the TIB are binding on the AIVD.14 The CTIVD assesses whether the measures adopted by the AIVD are proportional and necessary to safeguard national security.15 The CTIVD can access all places and request information held by the AIVD.16 The CTIVD has binding powers to conduct investigations regarding the (mis)conduct or operations of the AIVD.17

In summary, we have outlined that judicial oversight, parliament oversight, and independent oversight boards act as primary accountability mechanisms regarding the work of intelligence and security domains. Arguably, in the Netherlands, the primary accountability mechanism regarding the legality of intelligence and secret services operations is conducted through independent oversight boards, with a lesser degree of parliamentary oversight. Similarly, in the case of the Netherlands, court oversight is visible in exceptional matters.

3.5 Intelligence and security in a complex actor-forum relationship

The Vienna Commission 2007 said intelligence services are accountable -or scrutable- under the same principles of accountability governing all public servants (see text footnote 2). Stottlemyre outlines that intelligence officials do not serve the ruling regime in office. Instead, they serve the people; intelligence practitioners provide security for the people. Therefore, their assignment is “protecting individuals from fear -regardless of the political context” (Stottlemyre, 2023).

In the Dutch context, Wills and Vermeulen (2011, p. 41) are of the view that the Dutch intelligence and security services, as well as its ministers, ought to comply with the law and be subject to accountability. Similarly, Wills and Vermeulen (2011, p. 41) agreed that intelligence and security domains should account for their actions. This accountability process may be carried out through parliament oversight or independent oversight boards appointed by the parliament (Wills and Vermeulen, 2011, p. 41).

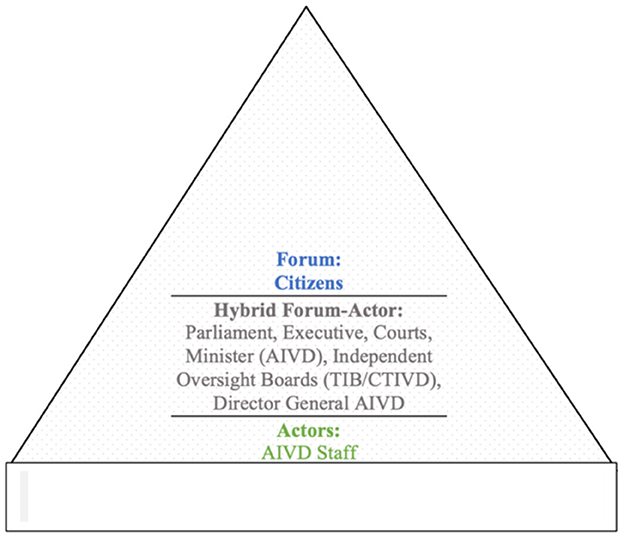

In intelligence and security domains, the actor-forum relationship can be complex due to a multi-layer of actors and forums, on occasion, playing hybrid roles. The complex actor-forum relationship involving citizens, their representatives, and other actors can be explained in Figure 1: citizens sit at the top of the pyramid, leading to different scenarios. Firstly, citizens entrust parliament to exercise control over the executive in national security administration. In this case, the distinction between actor and forum is straightforward: Citizens, as primary recipients of accountability, are considered the forum, while the parliament entrusted with scrutiny duties are the actors. The forum can punish the actors for their shortcomings by voting them out of parliament. A second scenario may arise; parliamentarians can become a forum to the executive or a particular minister -the actor- entrusted or assigned with national security and protection of fundamental rights. In this scenario, the executive or the concerned minister acts as accountable figures for their national intelligence and secret services and the scrutiny of the parliament. These political figures are responsible for providing an account to the public through the work of the parliament (Wills and Vermeulen, 2011, p. 41). There is a third scenario, and feasibly more, arguably more complex because one or more actors become a forum and vice versa. For instance, intelligence and security practitioners may be answerable to several forums. An intelligence practitioner -the actor- may be accountable to their director or leading minister -the forum. Simultaneously, intelligence practitioners and their organizations -as actors- may be required to provide account to independent oversight boards -the forum.18 Thus, intelligence practitioners are accountable actors caught in a complex actor-forum relationship. The complexity of the relationship between the actor and the forum may also lead to different challenges or frictions.19

Lastly, it is relevant to acknowledge that in holding an organization, such as intelligence and security domains, accountable, some literature may present a valid caveat: the problem of many hands (Cobbe et al., 2023, p. 1194). This problem argues that it is challenging to ascertain the responsibility of individuals who work as a collective (Bovens, 1998). Although, in legal or administrative terms, it may be challenging to ascertain individual responsibility -and liability, the literature supports that in this type of scenario, individuals are expected to act with a moral duty to act or behave positively (van de Poel et al., 2012). Thus, addressing and acknowledging that intelligence and security services are also bound under the same accountability principles of public service, being characterized as accountable intelligence actors, may provide an initial step toward solving the problem of many hands. Additionally, even in cases where legal or administrative individual responsibility is a challenge, the organization, the minister, and the government carry legal and political burdens to be accounted for (van de Poel et al., 2012, p. 14, 15; Bovens and Wille, 2021).20

To summarize this section, we highlight the following: first, intelligence and security domains are to be treated under the same rules of public service accountability. Intelligence and secret services are accountable to the people they serve. The people are the forum, which delegates forum powers to the parliament to conduct oversight of intelligence and secret services. Similarly, the people have legitimized the parliament to extend forum powers to courts of law and oversight boards to supervise the lawfulness in which intelligence and security domains operate (van Puyvelde, 2013).

3.6 Benefits of accountability and oversight in intelligence and security domains

In broad terms, there are several reasons why democratic societies are or should be interested in accountability principles in public service organizations such as intelligence and secret services (van Buuren, 2009, p. 4). It is argued that accountability can motivate public servants, including intelligence and secret services, to uphold positive practices (Bagave et al., 2022). Newberry21 considers that accountability in public service serves at its heart as a tool to protect citizens from potential abuse of powers from both the government in office and the parliament itself. Similarly, the Vienna Commission 2007, about the work of intelligence and secret services, urges the implementation of accountability safeguards to prevent misuse of power and to provide learning opportunities (see text footnote 2).

3.6.1 Benefits of accountability

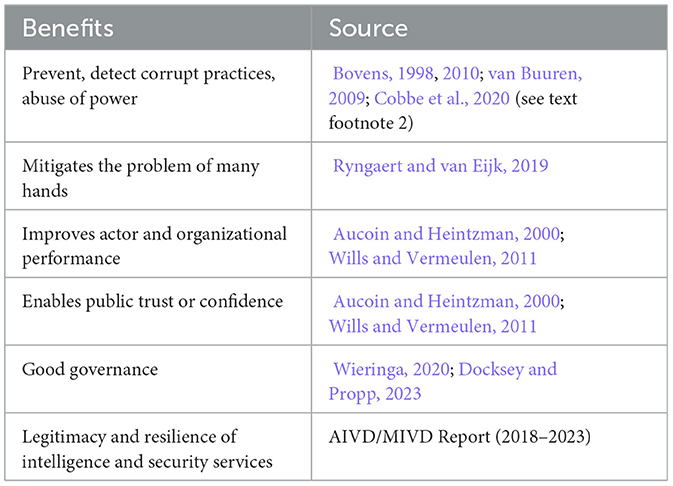

This study has found different benefits that accountability brings to intelligence and security domains. For instance, in Table 1, we observe an agreement between Bovens (2010) and Cobbe et al. (2023), to establish that accountability is vital in a democratic society because it enables the supervision of different actors to prevent and detect corrupt practices and abuse of power in government services. Similarly, van Buuren (2009, p. 3–4)22 states that intelligence and security services' accountability prevents abuse of powers and infringement of civil liberties and promotes good governance. Furthermore, according to Ryngaert and van Eijk (2019), accountability provides benefits such as ascertaining responsibilities and potentially mitigating the problem of many hands.

Aucoin and Heintzman recognize that accountability mechanisms or safeguards provide public trust and encourage and promote continuous organizational learning in government services. Similarly, Wills and Vermeulen (2011, p. 41) have established that accountability is vital because it improves the organization's performance and provides public confidence.

Wieringa (2020) establishes that accountability is a mechanism that facilitates better behavior of actors, allowing good governance. Similarly, in the words of Docksey and Propp (2023), accountability is the proactive commitment of actors to uphold ethical and legal frameworks for good governance in a democratic society.

The AIVD/MIVD 2018-2023 Report addressing the functioning of the Dutch intelligence and secret services (Verslag van het functioneren van de diensten) reveals that accountability contributes to the legitimacy and resilience of the intelligence and security services. This benefit of accountability was established by former director-general of the Dutch Intelligence and Security Services, Arthur Docters van Leeuwen (Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties, 2023b).

3.6.2 Benefits of independent oversight

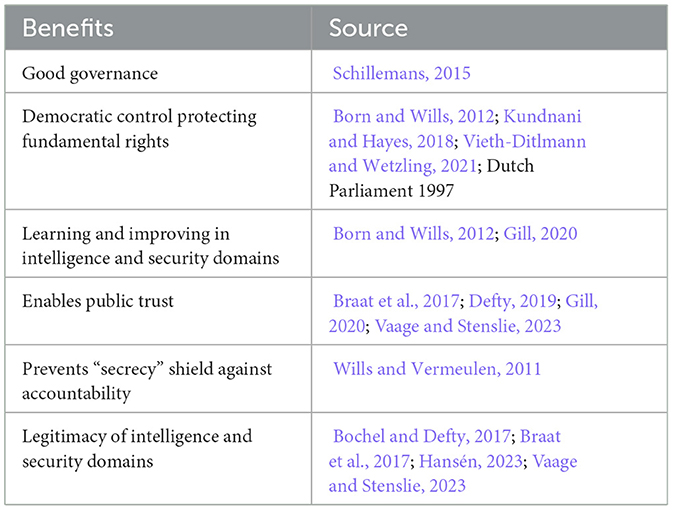

In Table 2, we observe that according to Schillemans (2015), independent oversight is an opportunity for an organization to show its willingness to be accounted for, displaying good governance practices. Furthermore, Born and Wills (2012, p. 17) sustain that intelligence oversight is essential because it can work as a tool to enhance democratic control. This view aligns with Wetzling and Dietrich, who stated that intelligence oversight is important because it can prevent misuse of power and protect fundamental rights (see text footnote 1). This line of thought appears to have consensus among scholars and political actors. For instance, Kundnani and Hayes (2018, p. 18) believe that independent oversight assures intelligence practitioners are accountable in cases of excess abuse of powers. For example, independent oversight can call out unlawful or oppressive policies that harm fundamental rights, cases where human rights defenders or journalists may be exposed to unlawful surveillance practices that affect fundamental rights (Kundnani and Hayes, 2018, p. 17). Similarly, the Dutch Parliament 1997 established that independent oversight prevents abuse of power in the intelligence and security services. Thus, to counterbalance the work of intelligence and security operations, independent oversight is required to allow adequate and effective safeguards against potential breaches of fundamental rights, such as the right to privacy and data protection (Kamer der Staten-Generaal, 1998).

Additionally, Born and Wills (2012, p. 17) have established that intelligence oversight can enable the effectiveness and efficiency of intelligence and secret services. Similarly, Gill (2020) states that intelligence oversight allows intelligence and security domains to learn and improve from past actions to ensure that the powers of intelligence and security domains are correctly used.

In the same line of thought, Wills and Vermeulen (2011, p. 85, 86) combine the benefits of independent oversight of intelligence and security domains, establishing that oversight can prevent using secrecy, inherent to intelligence and security work, as a shield to cover up malpractices. Thus, intelligence oversight helps intelligence and security domains to stay focused on their tasks and purposes.

Furthermore, according to Hansén (2023), the importance or benefit of independent oversight in intelligence and security domains is that it provides legitimacy to the work of these agencies because oversight can encourage intelligence practitioners to uphold the rule of law. Bochel and Defty (2017, p. 109), Braat et al. (2017, p. 223), and Vaage and Stenslie (2023), concur with this view of the benefit of accountability, establishing that intelligence oversight provides greater accountability of intelligence and security domains, strengthening their legitimacy.

In addressing the accountability of government services for using algorithmic methods, Meijer and Grimmelikhuijsen (2020, p. 54) have stressed the importance of citizens' trust in legitimizing the government. Likewise, Gill (2020), when referring to intelligence and secret services, states that intelligence oversight allows trust in the operations of intelligence and security domains. Similarly, other scholars such as Braat et al. (2017, p. 223), Defty (2019), and Vaage and Stenslie (2023), also consider that intelligence oversight enables public trust for the work performed by intelligence and secret services.

To summarize this section, intelligence and security domains, using data and technologies in their everyday tasks, need to be subject to democratic control (Gill, 2020). Independent oversight boards enable democratic control, supporting fundamental rights and providing means for resilient and trustworthy intelligence and security domains. The dismissal of accountability and oversight mechanisms in intelligence and security domains harms the institution's legitimacy and harms a democratic society (Solove, 2007, p. 766).

In answering question one, some of the common principles of accountability in democratic societies are taking responsibility, being answerable, explaining and justifying decisions, and fostering oversight (the actor-forum relationship). In answering question two, following Tables 1, 2, we have identified some common agreement regarding the benefits of accountability and oversight to society and intelligence and security communities: preventing or detecting corrupt practices and abuse of power, protecting fundamental rights, mitigating the problem of many hands, improving individual and organization performance, enables public trust, provides legitimacy and resilience of intelligence and security domains.

4 Section 2: workable principles of accountability for intelligence and security domains

In Section 3, “Accountability and oversight in dutch intelligence and security domains”, we have provided an inventory of the different definitions or conceptualizations of accountability in public service that can be useful to intelligence and security domains. We have also highlighted the importance of accountability in the actor-forum relationships between the AIVD and citizens, represented by supervisors such as the CTIVD, TIB, parliament, and judicial oversight.

In Section 4, we conduct desk research analysis, including a literature review and national and international legal and policy instruments, to gather some fundamental accountability principles commonly applied to public service, including intelligence and security domains, to develop Table 3, “Key accountability principles applicable to intelligence and security domains”. These proposed principles can be summarized as acting within duty, explainability, necessity, proportionality, reporting and record keeping, redress, and continuous independent oversight. These intertwined principles aim to provide a starting point to address the challenges in intelligence and security domains regarding protecting national security and fundamental rights. Similarly, in our study, we found that different scholars have suggested that the viability of applying accountability principles across organizations would depend on the conditions supporting the good intentions of accountability. This factor is summarized in Table 4, “Conditions supporting workable accountability”: productive actor-forum relationships, cooperation, flexibility, value alignment, and learning and improving opportunities.

4.1 Acting within duty

When studying accountability applied to intelligence and security domains, it may be helpful to refer to international frameworks such as the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in the Big Brother Watch and Others v. the UK (no.58170/13) case. The ECtHR has established that the work of intelligence and security domains needs to be confined to strictly acting within their legal duty, in other words, to act under the scope of their legal duty and power (see Table 3). This same principle was also confirmed by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in La Quadrature du Net and Others (ECLI:EU: C:2020:791). Acting with the duty may be understood as applying what is prescribed or written by the law. The CJEU, in the matter of La Quadrature du Net and Others (ECLI:EU:C: 2020:79) (para 132), established that in cases of government surveillance and collection of bulk data, clear rules needed to be established by the law to enable intelligence practitioners to follow these rules. For instance, clear rules must be established to indicate how intelligence and security practitioners must handle personal data. These rules include the scope of their mandate and the safeguards implemented to minimize harm to fundamental rights when executing intelligence operations such as bulk interception of personal data.23

In Table 3, we also find consensus within Dutch legal instruments regarding intelligence practitioners acting under their legal duty. For instance, Article 8 of the Wiv 2017 imposes a general duty of care on Dutch intelligence and security practitioners in the Netherlands. This duty of care may be understood as protecting national security, the legal order, or other national interests. Furthermore, Article 24 of the Wiv 2017 directly imposes a duty of care on the services regarding technologies and data processing.24 It requires the AIVD to process data with due observance, meaning that the processing must have a specific purpose and be necessary to fulfill the tasks given to the AIVD.25 This duty means implementing measures to ensure the quality of data processing, which, for example, requires the accuracy and completeness of data being processed, including algorithms.26

Furthermore, in Table 3, we also find agreement among academic scholarship. Academics have found that, in practical terms, intelligence and security domains need to act within their duty. For instance, Vaage and Stenslie (2023) frame that an essential element of accountability in intelligence and security domains demands intelligence practitioners to follow the duty to speak the truth to decision-makers, meaning that intelligence and security practitioners must avoid contaminating the truth by the desires of political actors. van Buuren (2009, p. 5) supports this framing and endorses that the duty of speaking truth -or providing information- to decision-makers (e.g., political decision-makers or police enforcement) is within the context of acting in the best interest of national security and protecting the nation from threats.

The previous findings allow us to infer that a first step forward in finding workable accountability principles is to determine the scope of the duty of intelligence and secret services so they can have clear boundaries to act upon and to be accountable for. We denominate this first principle applicable to intelligence and security domains as the “acting within duty” principle.

4.2 Explainability

Previously, we stated that in the context of intelligence and security domains, establishing a duty and acting within the duty is necessary to enable the accountability process within these organizations. Similarly, the accountability process is supported by explaining or justifying actors' actions.

Explainability is required for small and complex decision-making, such as human-technology interactions or assessing international data exchanges with other counterparts. For instance, Table 3 shows that the ECtHR in Big Brother Watch and Others v. the UK (paras 382, 383, 417) set explainability as a key principle of accountability. The ECtHR found that British intelligence and secret services needed to explain or justify the bulk retention, processing, and analysis of personal data.27

In the Dutch intelligence and security domains, we have noted that their legal frameworks allow them to use data and technologies. For instance, Dutch practitioners can utilize automated data analysis to analyze the bulk interception of cable communications.28 However, as shown in Table 3, Dutch practitioners are prohibited from making decisions solely based on the outcome of automated technological tools. We infer that under Article 60(3) Wiv 2017, the accountability principle conditioning the use of data and technologies is subjected to the accountability of the human in the loop to explain their decisions.

The literature provides essential clues regarding studying key accountability principles applied to public service organizations. In Table 3, we find that Doshi-Velez et al. (2017), de Bruijn et al. (2022), and Fest et al. (2022) have stressed that accountability in public service requires government bureaucrats to justify and explain their decisions, mainly when using technological development. This justification or explainability of decision-making when employing technologies in public organizations supports accountability and promotes public trust in government services (Doshi-Velez et al., 2017). For instance, Fest et al. (2022) explain that this need for explanation or justification is presented among police officers; they translate this obligation to explain or justify the use of algorithms as part of being accountable actors in public service. Following the actor-forum relationship doctrine,29 we note that the explainability element includes justifying decision-making, as Molander et al. (2012) pointed out. Similarly, the effect of explaining decisions when, for instance, dealing with data or technological tools is that it can enable citizens' trust in their governments providing services (de Bruijn et al., 2022). Meijer and Grimmelikhuijsen (2020, p. 60–62) agree with these scholars and endorse that the explainability element allows citizens to trust the government's services. Thus, humans in the loop working in public service—e.g., intelligence practitioners- are accountable to citizens for explaining how they use data and technologies (Constantino, 2022). This obligation, or burden of proof, on the part of the decision-maker to explain their decisions creates an incentive for the decision-maker to question technology outputs (de Bruijn et al., 2022). The obligation of intelligence and security domains to explain and produce justifications when utilizing personal data and technological tools supports accountability (Kamer, 1998).30

4.3 Necessity

Demonstrating necessity as part of being accountable is another element in which we found agreement across different frameworks. Necessity applied to the work of intelligence and security operations may be explained as meeting the threshold to show a reasonable, clear, and legal purpose for the use of data (Belgian Standing Intelligence Agencies Review Committee, 2018, p. 5). In Table 3, we find an agreement between the ECtHR and CJEU regarding the principle of necessity in intelligence and security operations when interfering with the right to privacy. For instance, the ECtHR in the matter of Big Brother Watch and Others v. the UK (paras 311, 334, 355, 365) established that the collection of bulk data, although it breaches the right to privacy protected under Article 8 of the ECHR, might be only allowed in certain circumstances such as protecting national security (Hages and Oerlemans, 2021). Therefore, interference with fundamental rights, such as privacy, must be reasonably justified by demonstrating genuine necessity. Contrarily, if humans in the loop working in intelligence and security domains cannot demonstrate necessity, their actions may be regarded as unlawful, breaching Article 8 of the ECHR (see: Big Brother Watch and Others v. the UK, paras 424- 426). The same reasoning was displayed by the CJEU in La Quadrature du Net (ECLI:EU:C: 2020:79) (paras 121, 129), establishing that bulk data collection or government surveillance needed to demonstrate to be necessary to protect overall the rights and freedoms of citizens fostered by the rule of law and the European Union principles.

Dutch legal frameworks have also confirmed the principle of necessity when accounting for interference with the right to privacy in intelligence and security operations. Table 3 illustrates that the Dutch Court of the Hague established that Dutch intelligence practitioners had acted lawfully in their operations, having shown the necessity to protect national security.31 The Court heard the question of whether the Dutch government was allowed to use data intercepted by the United States intelligence and secret services without knowing whether such data collection infringed fundamental rights and Dutch law. The Dutch court submitted that the AIVD was authorized to engage in international cooperation in cases where it was demonstrated to be necessary. In this matter, the ground of necessity was focused on the importance of Dutch national security. The Dutch Court established that the interests of individuals or particular groups, such as the right to privacy and data protection, were subjected to the protection of national interests.32

The requirement of necessity works to protect citizens against unwanted government intrusion. The purpose of introducing necessity as an accountability principle in intelligence and security operations is to protect citizens from disproportional government surveillance, as subscribed by Milaj (2016) in Table 3. Cooper, in Table 3, also stresses the need to introduce the necessity principle in intelligence and security operations to require the decision-maker, humans in the loop, to demonstrate that their actions warrant necessity.33 Similarly, Bigo et al. (2015) have argued that national security should not prevent the necessity principle from being overlooked in intelligence and security operations.

4.4 Proportionality

Accountability in intelligence and security operations is complex and requires more than demonstrating a legal ground or power to act. It also requires other elements, such as showing that the actions of intelligence actors were proportional. In Table 3, the CJEU in La Quadrature du Net (ECLI:EU:C: 2020:79) (paras 113, 121, 129, 130, 131) found that any measures, such as collecting citizen's data infringing the right to privacy need to have regard to the principle of proportionality. Proportionality allows a holistic assessment, weighing different values in the face of the necessity presented at a given moment.

Proportionality is also addressed in Dutch intelligence and security domains, see Table 3. For instance, Article 26 of the Wiv 2017 requires the AIVD to collect (personal) data having regard to the circumstances of the case. In other words, accountable intelligence actors, in the course of their duties, must consider the seriousness of the threat against the protected interest, including national security and privacy as fundamental rights. AIVD practitioners are called to account to assess whether the use of special powers is proportional to the threat.34

Following international and national frameworks, academics also agreed that proportionality is a key factor in balancing the powers given to intelligence and security domains. For instance, in Table 3, Enqvist and Naarttijärvi (2023) sustained that the proportionality requirement is essential because it balances the purpose for which the data is being used; this balance is measured against the protection of fundamental rights, such as limiting the right to privacy protection against an overwhelming threat to national security. Lastly, as hinted previously, these key accountability principles are intertwined in a way that it is plausible that the proportionality assessment may change according to the necessity (Belgian Standing Intelligence Agencies Review Committee, 2018, p. 5). Thus, as stated by Joel (162), it is plausible to ascertain an overlap between the necessity and proportionality principles, both heavily applied by European frameworks to call to account intelligence and security domains. Lastly, following the view of Milaj-Weishaar in Table 3, the fact that a legal mandate may allow the breach of privacy rights on the grounds of national security does not mean that necessity or proportionality assessments can be avoided. Instead, intelligence and security domains must take into account in their decision-making the necessity of the interference followed by its proportionality regarding the specific case (Milaj-Weishaar, 2020).

4.5 Reporting and record keeping

In addition to the previous accountability principles presented. Table 3 shows that record keeping and reporting are essential accountability features supported by international instruments. This principle is relevant in the work of intelligence and security domains. The record keeping requirement in intelligence and security domains is addressed by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in the Big Brother Watch and Others v. the UK (para 356), establishing that intelligence and security domains must record in detail each step of the process for bulk interception of data. This recording requirement in accountability is necessary because it enables the possibility to scrutinize the work of intelligence and security domains, opening up opportunities for organizational improvement.35

The Dutch intelligence and security domains also acknowledge reporting as an enabler of accountability. In Table 3, we describe that under Article 27 of the Wiv 2017, the AIVD is compelled to draw up a report regarding the destruction of unnecessary data collected by them. In the Dutch intelligence and security frameworks, under Article 12 of the Wiv 2017 they are also required to produce annual reports.

In the literature, we also find agreement regarding the record keeping and reporting requirement to allow greater accountability of intelligence and security domains. For instance, in Table 3, Wetzling established that accountability safeguards are tangible when implementing record keeping and reporting obligations in intelligence and security domains (Wetzling, 2019; Bagave et al., 2022, p. 23). Gill (2023) also suggests that adequate record keeping can help oversight boards identify the shortcomings of intelligence and security domains, particularly in fundamental rights breaches. Taylor (2011) identifies the failure or poor record keeping in intelligence and security operations as possibly undermining adequate oversight of intelligence and security domains. Thus, we submit that record keeping and reporting are essential features for the workability of accountability in intelligence and security domains because they enable scrutiny of intelligence and security domains, providing means to improve professional practices.

4.6 Redress

Accountability principles also foster redress because they allow the identification and address of injustices made to citizens who have suffered wrongdoing by the government (Braithwaite, 2006, p. 35). In Table 3, we observe that international frameworks such as the ECtHR in Big Brother Watch and Others v. the UK (no.58170/13) (paras 359, 413, 425) stressed the need for redress as part of accountability in intelligence and security domains. In the case of unjustified or unlawful data processing in the context of national security, redress may be operationalized by providing binding powers to independent boards to require the destruction of data unlawfully obtained by intelligence and security domains (Bovens and Wille, 2021). Similarly, the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights supports that redress can be used to require intelligence and security domains to destroy personal data unlawfully obtained (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2023, p. 27).

Table 3 shows that Dutch intelligence and security domains are subjected to redress principles. For instance, the AIVD can amend or prevent unnecessary infringement of privacy rights by destroying personal data that have lost purpose or are unnecessary in fulfilling intelligence and security duties.36 Similarly, Article 124 of the Wiv 2017 provides redress measures by imposing administrative sanctions on the AIVD. These administrative sanctions may be materialized in orders to terminate intelligence and security operations or orders against the AIVD to delete or destroy data they process.37

There is an overwhelming agreement across scholars regarding redress. For instance, in Table 3, we observe that Braithwaite (2006, p. 35), Fox (2007), Doshi-Velez et al. (2017), Korff et al. (2017, p. 12), Bovens and Wille (2021), and Docksey and Propp (2023), agree that a tangible characteristic of accountability in intelligence and security domains is the implementation of redress measures. In summary, we have learned that redress in intelligence and security services is materialized through binding orders to require accountable intelligence actors to stop or destroy unlawful or unneeded data processing.38

4.7 Continuous independent oversight

Another key principle of accountability in intelligence and security domains is the operationalization of independent oversight. This section observes the agreement across different authorities regarding the implantation of oversight in intelligence and security domains.

In Table 3, we observe that the ECtHR established the requirement of oversight in intelligence and security domains. For instance, in the case of Big Brother Watch and Others v. the UK (no.58170/13) (paras 350, 361, 381), the ECtHR said that in matters of government surveillance, it is necessary to have continuous appropriate oversight to supervise the use of special powers—such as surveillance and bulk data processing—of intelligence and security actors. The ECtHR established that continuous oversight is the counterbalance to safeguard fundamental rights against the powers given to intelligence and security domains (paras 349–350, 354). Similarly, the ECtHR highlighted that independent oversight boards' powers must be robust to limit the effects of the infringement on fundamental rights (para 356).

Furthermore, Table 3 shows this trend in accepting independent oversight to protect fundamental rights against the powers given to intelligence and security domains. For instance, the Vienna Commission 2007 has stated that to foster accountability in intelligence and security domains, independent oversight needs to be done end-to-end (prior, during, and after) (see text footnote 2). Similarly, in 2014, the European Parliament called on the Netherlands to put independent intelligence oversight boards in place to satisfy the European Convention on Human Rights (European Parliament, 2014).

In Table 3, we observe that, in 1997, the Dutch Parliament agreed that intelligence and security domains must welcome the opportunity to be subjected to end-to-end independent oversight to protect fundamental rights, such as the right to privacy (Kamer, 1998). This desire from the Dutch parliament to implement end-to-end independent oversight was materialized through Article 36(2)(3) of the Wiv 2017, introducing the TIB, which conducts prior legality assessments regarding the AIVD's operations. Similarly, under Article 97(3)(a) Wiv 2017, a second oversight board, the CTIVD is tasked with assessing the lawfulness of the AIVD's operations.39 The CTIVD supervises the AIVD's ongoing and completed operations.

International and national instruments and scholars agree upon the need for continuous independent oversight. In Table 3, Vieth-Ditlmann and Wetzling (2021) agreed that independent oversight in intelligence and security operations is necessary to safeguard citizens' rights against unlawful intrusive measures exercised by intelligence and security domains. Similarly, Aucoin and Heintzman (2000), van de Poel et al. (2012), and Bovens and Wille (2021) conceive the idea of continuous independent oversight as a tool to mitigate human or organizational errors that may harm citizens. While Ryngaert and van Eijk (2019) suggest that independent oversight of intelligence and security domains contributes to privacy and data protection safeguards.

Lastly, Ossege (2012) addresses independent oversight of intelligence and security domains, outlining the complexities this mechanism may bring to the actor-forum relationship. The caveat regarding oversight is that, in some cases, it may be treated as a power game rather than a tool to safeguard citizens' rights and provide a means for organizational improvement. Making independent oversight work in the actor-forum relationship will require productive relationships between the parties to achieve workable accountability principles in intelligence and secret services. For instance, it may be necessary for the actor to be more cooperative while the forum to be more flexible. This last caveat regarding oversight will be addressed in the following paragraphs.

4.8 Conditions supporting workable accountability

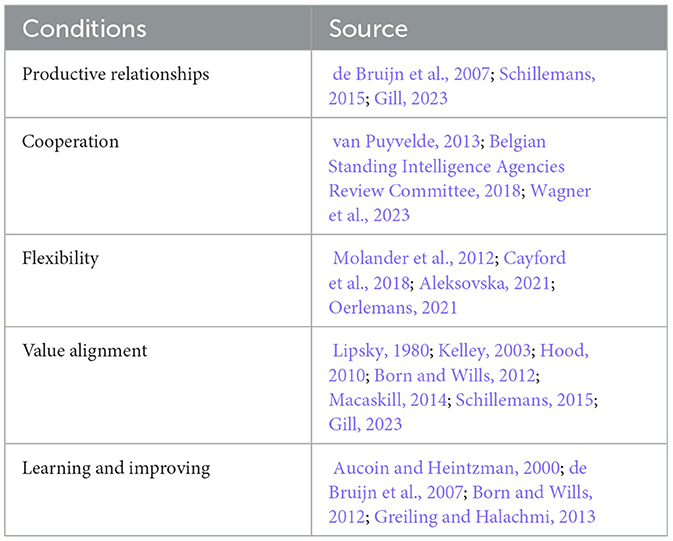

Previously, we have addressed some key principles of accountability that can be implemented in intelligence and security domains to safeguard fundamental rights. In this section, we will detail some conditions that support the workability of these accountability principles in a way that provides room for intelligence and security operations while safeguarding other fundamental rights. These conditions supporting workable accountability are summarized in Table 4.

4.8.1 Productive actor-forum relationships

Gill (2023) describes that, on occasions, accountability and oversight in intelligence domains have been regarded as a constant contest for control. Thus, the most sensible option is to foster productive relationships to achieve workability of accountability principles in intelligence and security domains (see Table 4).

In Schillemans' work, he conducts research among public service managers to investigate how they see, feel, and cope with accountability. Schillemans (2015) found that accountability can be an “intrusive and annoying process [that] may on the balance be helpful to public managers and organizations [to achieve] organizational changes”. Schillemans (2015) emphasizes that approaching accountability from a productive relationship perspective is focused on being constructive instead of oppressive (see Table 4).

Accountability is positive when it allows space for actors to explain their actions rather than imposing an oppressive approach. In Table 4, de Bruijn et al. (2007, p. 18) also subscribe that accountability in the actor-forum relationship requires a productive relationship to achieve workable arrangements to allow both actors and forums to conduct their duties. The opposite of a productive relationship approach to accountability may be reduced to a sanctioning or oppressive style of accountability. This approach to accountability undermines the opportunities to learn and improve de Bruijn et al. (2007, p. 20). Accountability may be intrusive to actors' actions. Still, it can lead to improving organizational practices if productive relationships are developed.

4.8.2 Cooperation

Accountability and oversight require a collective effort of all parties involved in the actor-forum relationship. Cooperation among the different parties is necessary to support and foster accountability principles. In Table 4, we observe Wagner et al. (2023), pointing out that the cooperation of actor and forum is indispensable to make accountability work (Schillemans, 2015). Similarly, van Puyvelde (2013) states that cooperation includes welcoming a plurality of oversight groups immersed in the accountability process, facilitating accountability in the intelligence and security domains, and supporting intelligence organizations to embrace best practices in a democratic society (Born and Wills, 2012, p. 7). For instance, Cooperation means facilitating cooperation among oversight boards from different jurisdictions to compare investigative methods, interpret legal frameworks, and discuss practical and legal problems concerning intelligence communities.40

The Belgian Standing Intelligence Agencies Review Committee agrees with cooperation as an enabler of accountability and has stated that cooperation can help to alleviate oversight gaps where different boundaries limit oversight bodies (see text footnote 2). In summary, accountability requires the cooperation of all parties: actors and forums.

4.8.3 Flexibility

In Table 4, we observe that Oerlemans and Cayford et al. hint at applying flexibility in the accountability process of intelligence and security domains. For instance, Oerlemans mentions that the law must be flexible for national security purposes to allow security and intelligence practitioners to perform their jobs.41 Similarly, Molander et al. (2012) argue that public decision-makers need to be judged with flexibility regarding their decision-making so these public servants can work in an environment where they can apply discretion in fulfilling their duties. Aleksovska (2021) reveals that the Dutch government is exploring ways to create more flexible accountability mechanisms to avoid public servants' decision-making being restricted to stringent accountability mechanisms. For instance, inflexible -or unworkable- accountability can lead to public servants spending too much time on irrelevant -even unnecessary- compliance procedures, making public service organizations less efficient (Aleksovska, 2021). Thus, there is a need for flexibility and a less stringent application of accountability (Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Force, 2017, p. 4). Of course, this flexibility should be conducted in light of all the above principles of accountability asserted (Naarttijärvi, 2019, p. 46).

4.8.4 Value alignment

Professional values of the individual and the organization should embrace accountability mechanisms, such as independent oversight, which play an essential role in having workable accountability. In Table 4, we observe that Schillemans (2015) agrees that professional values can play a role in the success of accountability principles; values can be a course or a blessing because of the different internal and external relationships and values concerning the organization that are at stake. Macaskill (2014) states that the Snowden case has revealed the challenges that professional values and the internal culture in intelligence and security domains can pose to upholding democratic values regarding safeguarding data and privacy.42 Similarly, Gill speaks about the accountability culture within British security and intelligence agencies, finding that double standards have tainted accountability principles regarding reporting obligations. Gill (2023) found that British intelligence agencies failed to apply reporting obligations policies into practice. And Born and Wills (2012, p. 8) hint at the importance of value alignment in intelligence and security domains when fostering independent oversight to promote the protection of fundamental rights. Similarly, Kelley states that one of the problems ın American intelligence communities is the need for adequate human capital to respond to value alignment to satisfy legal duties, such as protecting national security and fundamental rights.43 In the work of Lipsky (1980), comparable dilemmas across street-level bureaucrats are revealed. Lipsky points out the difficulty of delivering the good intentions of public policy to the people they serve when other individual and organizational values are not aligned with policy reforms to improve government services.

In Table 4, reflecting on the value alignment of the actor-forum relationship, Hood illustrates that accountability can sometimes be like an awkward couple where some of their interests or values from actors and forums may be in tension with one another. In this complex relationship, both parties must compromise to make accountability work (Hood, 2010). For example, in the pursuit of protecting the country from national threats or protecting citizens' rights from privacy violations, frictions or conflicting interests may arise, which may require certain compromises. Thus, the interaction of parties involved, actor and forum, AIVD and TIB or CTIVD, requires a combination of different approaches to accountability, such as productive relationships, flexibility, cooperation, and finding common ground on value alignment between the parties.

In short, value alignment refers to the effort from the actor and forum to uphold accountability principles. The efforts are expected from the entire organization, from management to staff at the bottom of the chain, to adhere to and promote a workable accountability culture (Born and Wills, 2012, p. 9).

4.8.5 Learning and improving

In Table 4, Aucoin and Heintzman (2000) agreed that accountability must be embedded as a continuous human and organizational learning and improvement process. Similarly, continuous learning may be possible by implementing continuous independent oversight that embraces productive relationships. Thus, as Born and Wills (2012, p. 6) stressed, it is preferable to have ongoing independent oversight of intelligence and security domains to allow continuous improvement and learning of individuals and organizations.44 Lastly, de Bruijn et al. (2007, p. 18) provide a valuable approach to accountability, framing it as the opportunity for supervisors or oversight boards to take a pedagogical approach to allow room for learning and improvement. For instance, a pedagogical approach to foster awareness regarding the adequate protection of fundamental rights in intelligence and security operations. Greiling and Halachmi (2013) agree with this approach and establish that accountability as the opportunity for learning and improvement is more promising than implementing accountability as the chance to blame people.

In answering question three, which common principles of accountability are appropriate for the AIVD? We can conclude that acting within duty, explainability, necessity, proportionality, reporting and record keeping, redress, and continuous independent oversight can be applied to the work of intelligence and security domains such as the AIVD. Similarly, in making the above principles workable, we submit that the actor and forum -for instance, AIVD, TIB, and CTIVD- may engage in productive actor-forum relationships, cooperation, flexibility, value alignment, and learning and improving opportunities. Accountability principles do not need to be seen as a negative trait (Tian, 2017). Rather, accountability should be seen as a festivity and accepted as part of holding a public service position (Schillemans, 2015). Accountability can contribute to long-term learning opportunities in the organization (Greiling and Halachmi, 2013).

5 Section 3: discussion

In Section 3, “Accountability and oversight in Dutch intelligence and security domains”, we have provided an inventory of the different definitions or conceptualizations of accountability in public service that can be useful to intelligence and security domains. We have also highlighted the importance of accountability in the actor-forum relationships between the AIVD and citizens, represented by supervisors such as the CTIVD, TIB, parliament, and judicial oversight. Similarly, in Section 4, “Workable principles of accountability for intelligence and security domains”, we have established that to support the workability of these accountability principles, actors and forums are encouraged to engage in productive relationships, which include cooperation, flexibility, value alignment, and learning and improving opportunities.

Section 5 discusses how the proposed workable principles of accountability may come together to provide some coping mechanisms for the tensions between the Dutch AIVD -the actors- and oversight boards, the CTIVD or TIB -the forum. We discuss how our proposed workable principles of accountability might work in practice to allow productive actor-forum relationships between actor and forum in a way that the actors (AIVD) can have room for maneuvering when it comes to protecting national security while allowing adequate empowerment to the forum (TIB, CTIVD, citizens) to comply with its tasks of safeguarding the protection of fundamental rights.

5.1 Defining tensions

The Netherlands Court of Audit (Rekenkamer, 2021), in its 2021 Report, highlights some of the tensions -or struggles- in the AIVD and the implementation of accountability principles imposed by the Dutch Intelligence and Security Services Act 2017 (Wet op de inlichtingen- en veiligheidsdiensten 2017, “Wiv 2017”). The legislation brought forward two oversight boards to supervise the AIVD to safeguard fundamental rights against the prerogative given to the AIVD to deploy special powers on the grounds of national security. These supervisory boards are the TIB and CTIVD (see 3.4.3 Independent oversight boards). These boards have been tasked to enforce principles of accountability, such as conducting legality assessments primarily focusing on necessity and proportionality in the operations of the AIVD (TIB Annual Report 2021).

The Report has established that the accountability principles brought by the Wiv 2017 have been underestimated and challenging, stating no fault of the AIVD, the TIB, or the CTIVD in implementing accountability. Instead, the Report considers that the parliament and executive needed to evaluate the practical consequences more in-depth regarding the implementation and capabilities for compliance with these new accountability principles in the AIVD. For instance, there is a need to invest resources in more specialized staff to ensure compliance with principles of accountability.