Abstract

This article presents and proofs an alternative concept of democracy that seeks to overcome the limitations of rigid universalist, liberal-proceduralist conceptions by emphasizing the fundamental principles of democracy rather than combining them with culturally individualistic features. The approach presented here focuses on the fundamental principles of democracy. Democratic configurations assume that citizens’ political self-efficacy of the people is a potential basic principle behind any institutionalization of democratic order. Therefore, this article refers on a discussion of the theoretical implementation of self-efficacy in the three models of democracy: liberalism, republicanism and communitarianism. Ultimately, every political system must be studied by whether the established institutions serve this basic principle. The article illustrates the proposed approach through case studies of Singapore, Ghana, and Ireland. The empirical examples show how different institutional settings and their adjustments strengthen and hinder political self-efficacy. Therefore, this new bottom-up-approach of studying configurations of democracy may help to get better insights on the democraticness of political systems and other institutional settings.

1 Introduction

The days of democratization in the sense of promoting liberal democracy and adapting to liberal democracy are over. We are in an era of post-democratization (Chong and Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2022). The term “post-democratization” is used to describe political processes that occur after the end of the transition paradigm (Carothers, 2002) by examining two overlapping processes: the attempt of elites to autocratize themselves and a population that is increasingly disillusioned with the usual offerings of democracy. In the era of post-democratization, it can be observed that illiberal alternatives to the liberal tradition and/or populism are increasingly emerging in many regions of the world, to the point of regression or persistence in authoritarian structures (Lührmann and Lindberg, 2019; Norris and Ronald, 2019).

Against this backdrop, the paradigm of liberal democracy is increasingly being called into question (Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2023; Selk, 2023). In the political science debate, this paradigmatic narrowing of the concept of democracy is being opened up. The inclusion of marginalized meanings and understandings of democracy is long overdue (Chakrabarty, 2008; Gagnon et al., 2021; The Loop Democracy, 2021).

At the same time, it cannot be in the interests of empirically oriented democracy research and comparative politics if the theoretical and political discourse on non-Western democracies is used to covertly talk about diminished subtypes of democracy or if the concept of democracy is stretched to the extent that new forms of despotism can hide behind it.

Democracy is a latent construct and, by nature, not directly observable. Nevertheless, we need indicators and empirically observable characteristics that we can assign to specific concepts of democracy (Morlino, 2021; Stark et al., 2022). This approach can be found on the one hand in standard definitions of democracy and consequently in indices that measure the quality of democracy, or on the other hand in surveys of support for democracy, which are usually equated with the holding of free and fair elections. However, if we focus only on certain institutional patterns, which in most cases are derived from Dahl’s (1989) reflections on polyarchy, we block our view of the multiple meanings of democracy that lie beyond a liberal-procedural understanding of democracy. Therefore, it seems unavoidable to look behind the scenes and search for the underlying “core principle” which institutions, in the Western case, of liberal-procedural or representative democracy, serve (Stark et al., 2022; Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023). These perspectives align with those previously espoused by Doorenspleet (2015), Warren (2017), and Asenbaum (2022). These authors advocate a functionalist perspective on democracy that goes beyond the limits of an institutionalist approach to which the liberal model has come to be reductively equated. Democracy cannot be reduced to the domain of the state or institutions; rather, it is essential to focus on the functions of institutions for democracy (Doorenspleet, 2015; Warren, 2017). Furthermore, it is imperative to recognize that the views of the people affected by democracy should be taken seriously when determining what constitutes democracy. This necessitates moving beyond the ivory tower, where experts determine what democracy is (Doorenspleet, 2015; Asenbaum, 2022).

With reference to the configurations of democracy (Stark et al., 2022; Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023), this article would like to discuss and proof an attempt to take precisely this conceptual step. In summary, the configurations of democracy assume that the political self-efficacy of citizens is a possible basic principle behind any kind of institutionalization of democratic order and that ultimately every political system must be measured by whether the established institutions serve this basic principle. The objective of this paper is to examine whether the components of institutional arrangements and practices associated with the different conceptions of democracy serve the core principle of democracy as political self-efficacy. Additionally, this functionalist approach will be tested for its ability to distinguish between democratic and non-democratic institutions. This will provide insights into the potential of this approach for addressing the challenges in democracy research discussed in this paper.

The paper is structured as follows: The following sections present the state of the art of democracy research and conceptual and methodological approach of studying configurations of democracy in a comparative way (2 and 3). After that we present three case studies (Singapore, Ghana, and Ireland) that illustrate the logic of this approach (4). The cases of Singapore and Ghana as non-Western political systems and Ireland as a Western political system will be used as examples, from different global regions, with political regimes ranging from electoral autocracy to consolidated democracy and a variation of formal and informal institutions flanking representative elements, to show the extent to which this conceptual approach points in the right direction when it comes to breaking down the liberal-procedural narrowing of the concept of democracy without at the same time stretching the concept of democracy to the point of uselessness. These case studies are a first attempt to see whether it is possible to identify non-democratic processes with the proposed conception of democracy based on the core of political self-efficacy rather than institutions. Finally, the paper ends with an outlook (5).

2 State of the art—empirical research on democracy

This paper is based on the assumption that the meanings of democracy extend beyond the understanding of democracy as it has been operationalized in empirical democracy research to date (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2020). Furthermore, it is posited that democracy has different meanings in different contexts (Doorenspleet, 2015, p. 478). At the same time, meanings of democracy are distinct from the understanding of democracy. The understanding of democracy describes various individual representations of an essentially identical object, which allows for uniform measurement (Warren, 2017). When the term “meanings” is used (Braizat, 2010; Bratton, 2010; Chu and Huang, 2010; Diamond, 2010; Shi and Lu, 2010; Schaffer, 2014), conceptual ambiguity is permitted, taking into account both theoretical and regional variations in the concept of democracy (Weiß, 2015). In English, the term “individual understanding of democracy” is perhaps the most accurate translation, denoting the meanings that citizens associate with the D-word (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2020, p. 308).

One of the most important tasks of comparative democracy research is to systematically and empirically capture the meanings associated with the concept of democracy and to bring them together into a common, globally oriented, and transculturally based understanding of the concept (Schubert and Weiß, 2016). The expansion of the discourse on the meaning of democracy beyond the Western discourse context leads to a confrontation of globally different ideas of democracy and, as a result, to a shift in the meaning of democracy. This debate also reveals a narrowing of the concept of democracy as liberal-procedural democracy, which has been observed in empirical democracy research for decades. This debate has gained further momentum in the context of the ECPR Blog Series “The Sciences of Democracies.”

In contrast to the liberal-procedural concept of democracy, which has hitherto served as the benchmark in empirical democracy research, in some countries, citizens desire that the democratically elected elites be supported by the expertise of religious leaders or even a military takeover in the event that the government proves to be incompetent. Some reject the equal treatment of all social groups (Bratton and Mattes, 2001; Canache, 2012; Cho, 2015). The question thus arises as to whether these ideas can still be considered democratic. Other deviations from the liberal-procedural concept are less drastic but equally important. One such deviation is the strong emphasis on the participatory, deliberative, or social elements of democracy. In addition, citizens and elites of established Western democracies not only espouse a liberal concept of democracy but also exhibit community- and common-good-oriented attitudes, which are rooted in the traditions of republicanism or communitarianism (Davis et al., 2021; Wunsch et al., 2022; Häfner et al., 2023; Kaftan, 2024). These attitudes serve to complement the liberal concept of democracy. In recent years, these developments have led comparative democracy researchers to increasingly criticize the universalistic liberal concept of democracy, the standardized survey research methodology, and a fundamentally Eurocentric perspective in empirical democracy research (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2020).

Empirical evidence suggests that democracy is associated with the state and equated with certain state institutions, in particular elections forming the essential core of democracy (Warren, 2017; Manow, 2020). The supply side of democracy is therefore especially important in the tradition of democratization research, research on the promotion of democracy, and research on the stagnation of transformation processes in hybrid regimes, which have been well studied. Instead, the demand side, namely the actual meaning of democracy among the people, which corresponds to their attitudes and behavior, is far less well researched (Lu and Chu, 2022).

The prevailing approach to measuring democracy, and to a considerable extent the manner in which the meaning and understanding of democracy is surveyed, is almost exclusively deductive, based on Western (democratic) theory. Data on approval or agreement is collected on the basis of a uniform, liberal-procedural understanding of democracy, as exemplified by Vanhanen, Polity and Freedom House, and also V-Dem (V-Dem, 2021). It appears that there is an underlying assumption that there is a de facto consensus on a precise definition of democracy. Consequently, there is a tendency to assume that a justification or explanation of the concept of democracy, which is used is unnecessary (Lauth, 2004, p. 298). These assumptions have led to the results, that the majority of the measurements of democracy (indices) are based on a universally applicable definition of democracy in the form of a root concept that underlies all definitions of democracy. This concept is Dahl’s (1989) concept of polyarchy, which has become the most frequently cited reference term in empirical democracy research in recent decades. The majority of indices utilized for measuring democracy are based on Dahl’s (1989) procedural understanding of democracy, which posits that democracy is comprised of two attributes: competition and participation or inclusion.

The theoretical foundation of the Vanhanen Democracy Index is directly based on Dahl’s (1971) polyarchy concept, which measures the extent of participation in the form of voter turnout and the extent of public competition.

Likewise, the democracy measurements in the polity studies (Jaggers and Gurr, 1995) focus on the degree of competition in political participation and the distribution of political offices, on the accessibility of government offices, the extent to which the executive branch is limited in its power, and the regulation of political participation (Gaber, 2000, p. 114; Berg-Schlosser, 2004).

The Freedom House Index is composed of political and civil rights, and, like the Polity studies, is based on a concept of democracy that embraces the principles of institutionalized competition and horizontal power limitation and the guarantee of personal and political freedoms (Gaber, 2000, p. 115f).

In the last decade, the V-Dem has become the dominant tool for measuring democracy and has largely displaced other indices in the field. What set V-Dem apart from other democracy measurement instruments was its assertion that democracy is an inherently contested concept. As a consequence of this fundamental assumption, V-Dem not only developed one index to measure democracy, but five separate indices: for electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian democracy. However, V-Dem places the electoral principle at the center of its analysis. “We would not want to call a political regime without multiparty elections ‘democratic’” (Coppedge et al., 2020, p. 27). The complementary principals (liberal, majoritarian, consensual, participatory, deliberative, and egalitarian) flank electoral democracy. While V-Dem continues to produce data on all these concepts of democracy and makes it available to the scientific public, an increasing liberal-procedural narrowing of the concept of democracy can be observed in scientific publications and politically oriented reports. This narrowing follows previous traditions of measuring democracy and exclusively uses a supposedly universal understanding of democracy as liberal democracy. Furthermore, V-Dem’s definition of democracy is limited to Western understandings, and it fails to incorporate the perspectives of citizens from non-Western societies (Wolff, 2023; Schäfer and Osterberg-Kaufmann, 2024).

One criticism that unites all the “existing measurement instruments” outlined here is that they “are limited in focus, dealing only with political elites and electoral procedures” (Doorenspleet, 2015, p. 470).

The research into the extent of support for democracy and the understanding of democracy (World Value Survey, 2017) also remains within this research tradition, and it asks about the support for elements of liberal procedural democracy. By pursuing an imperialism of categories (Rudolph, 2005), it attempts to define the characteristics of democracies and the desirable forms of governance. In doing so, it identifies typical liberal-democratic elements that are distinct from social elements and from elements that are not considered democratic.

Two central steps follow from these observations: (1) We must overcome the narrowing of the concept of democracy in empirical research on democracy, which is reduced to the liberal-procedural perspective on democracy. (2) We must expand the perspective of democracy as an organizational form from the perspective of the state and institutions (Warren, 2017). Instead, the perspective of citizens on democracy and how society should be organized should be taken into account. This is in accordance with the principle of “bringing the people back in,” as proposed by Doorenspleet (2015) and Asenbaum (2022).

However, this opening cannot simply consist of stating that liberal democracy, including the principle of representation and free and fair elections as the core of democracy, is no longer the ideal we aspire to (Warren, 2017). Nor can it consist of imagining deliberative democracy, for example, as an alternative ideal democracy and then rejecting everything that wants to call itself a democracy in the future, regardless of whether it has deliberative participation formats. The opening consists of stepping back from the institutions and asking what purpose or function they serve (Warren, 2017). What is the basic principle of all democracies, regardless of their type and form? Ultimately, it does not matter which institutions we find empirically, but rather which basic principle the institutions serve. The aim is to find this underlying principle and thus approach a singular core (which may also hold democracy together as an essentially contested concept; Gallie, 1956). From the perspective of political theory, it is possible to argue that a singular core has a renewed universal orientation. However, from the perspective of empirical research on democracy, which also wants to compare, we need some form of comparative criterion. The singular core of democracy would have to meet this requirement and at the same time be so abstract that it can claim global validity. This opening up is therefore not only associated with theoretical/conceptual challenges, but also with methodological and empirical challenges.

One approach to conceptualize democracy from such a suggested functionalist approach is the configurations of democracy project (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023).

3 Configurations of democracy

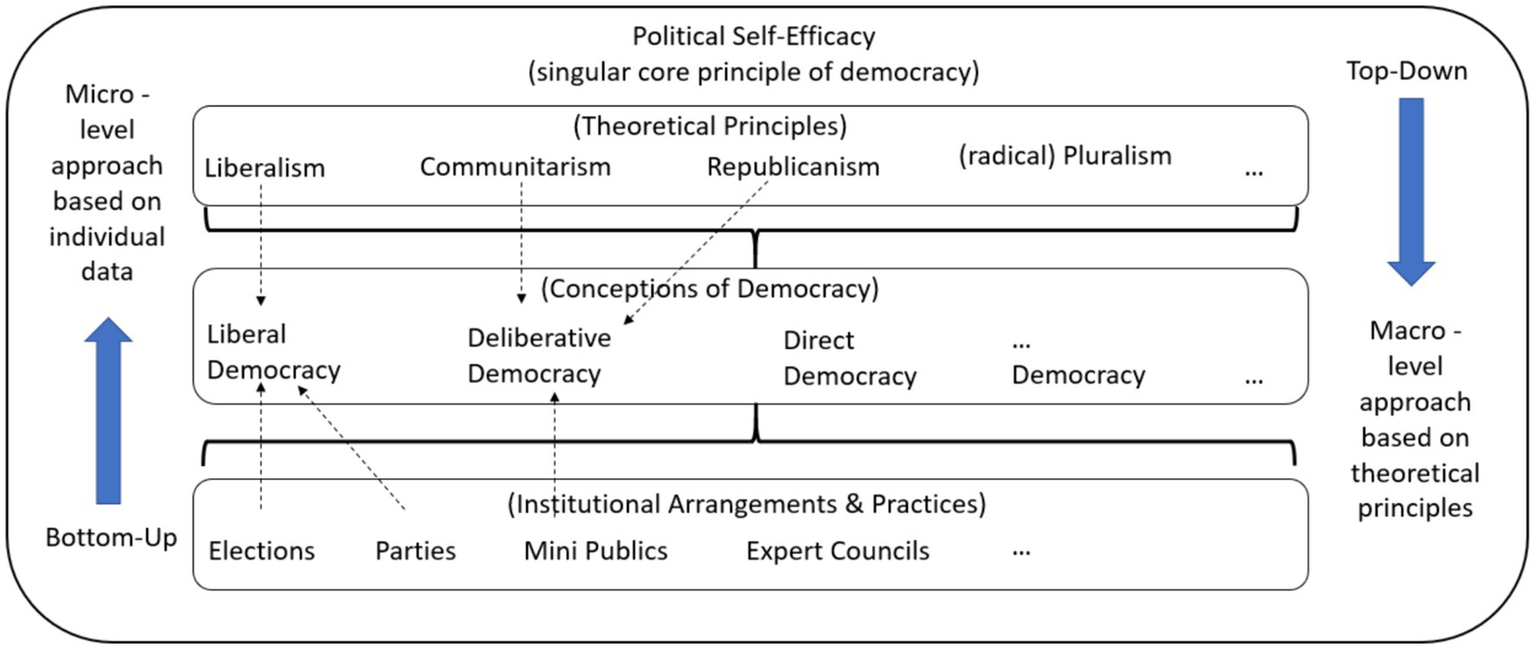

From an empirically-oriented or so-called bottom-up perspective, the fundamental principle of democracy can be identified by starting with the empirically observable institutions in a country and then moving up the ladder of abstraction to identify the underlying principles. Consequently, the common underlying principle is identified regardless of whether the principle is implemented, for instance, through the conceptualization of liberal or deliberative democracy (Figure 1). Even though a Western perspective shapes that proposal, the authors conclude that proceeding from the liberal, communitarian and deliberative perspective, the singular core principle that all conceptions of democracy might seek to realize is political self-efficacy (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023) of the people, of those who are affected by politics in the reading of Kelsen (1925).1

Figure 1

Concept tree of the new concept “singular core principle of democracy.” Source: Own compilation, based on Stark et al. (2022) and Osterberg-Kaufmann et al. (2023).

This assumption needs to be constantly reviewed in the research process. This can be done by analyzing formal and informal institutions, but also by comparing the normative concepts of order of the citizens affected by the institutions and evaluating the political systems in which they live on this basis (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023).

In light of the aforementioned considerations, it is evident that the future research agenda must include the following: What purpose, what function, and what principle should democracies serve? The answer to this question leads to the core principle of democracy, which should have global validity beyond its specific institutionalization. For example, political self-efficacy. In which institutions could this purpose, function, or principle be implemented? This question leads us to concrete institutionalizations or social practices (also beyond the state). These include elections, political parties, mini publics, expert committees, and even tribal assemblies. The respective institutionalizations correspond to certain conceptions of democracy (or models of democracy according to Held, 2006 or Warren, 2017), which can be broadly classified as liberal democracy, deliberative democracy, direct democracy, or even new conceptions. From a theoretical perspective, it is possible to inquire as to which theoretical principles are reflected in the ideas of democracy. These, in turn, can be located in certain theoretical principles, including liberalism, republicanism, communitarianism, and so forth. This cycle is conceivable in both directions. On the one hand, it is possible to investigate the purpose, function, and principle of democracy based on individual data. This can be done by asking citizens, political elites, or experts about their perceptions of democracy. This approach is inductive. Conversely, from a theoretical perspective, an attempt is made to identify the fundamental principles of democracy by examining the available empirical evidence. This evidence is derived from texts on democratic theory, traditions, or other sources. Both approaches aim to incorporate previously marginalized ideas of democracy or even new, innovative ideas of democracy into the global concept of democracy. Upon completion of this research cycle, it is possible that a different core principle of democracy may emerge than that which is currently assumed, with regard to political self-efficacy. Furthermore, the outcome of this process may be that this one core principle does not exist at all.

The insights gained from surveys (deductive) on the purpose, function, and principle of democracy and its respective institutional implementation could be fed back into survey research in a subsequent step. This would entail examining how citizens, elites, and experts evaluate the actual existing democracy in light of the identified core principle.

In order to reach a transglobal comparative theory of democracy, a new, interdisciplinary approach to thinking about democracy is needed. This also means the dismantling of the constructed opposition between qualitative and quantitative methods as well as between theory and empiricism. The classifications leading to a global, valid core concept of democracy must therefore allow for a top-down and bottom-up production of knowledge, which is, by the way, the key concept to solve social problems in democratic systems (Lindblom, 1990). This implies a permanent interplay of deductive and inductive methods, and a constant dialogue between theory and empiricism. The inductive approach, which is understood as an open approach because it starts with a specific set of observable facts or ideas to form a general principle, aims at the genesis of different meanings of democracy. To this end, it makes use of methodologically diverse approaches with a focus on qualitative methods. By means of the deductive approach, existing understandings of democracy can be measured, which together with the meanings draw the most valid picture of a singular core principle of democracy (Osterberg-Kaufmann and Stadelmaier, 2020; Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023).

In summary, the paradigm evolution that this approach (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023) is intended to inspire cannot simply consist of stating that liberal democracy, including the principle of representation and free and fair elections, is no longer the (unspoken) ideal we aspire to. The evolution of the paradigm does not entail positing deliberative democracy as the ideal democracy and then measuring all future democratic systems against the criterion of deliberative participation. The paradigm evolution entails a shift from the conventional institutional perspective to an inquiry into its underlying purpose (Doorenspleet, 2015; Warren, 2017). What is the underlying core principle of all democracies, regardless of their type and form, which is attempted to be realized with the most diverse institutions? Which ideas of democracy and institutions ultimately best do justice to this basic principle depends on the fundamental perspective and view on the organization of societal interests. If we explain the world with a republican, communitarian, or even liberal logic, it will be different processes or institutions that help to realize the basic principle of democracy in the best possible way, and this will result in different conceptions of democracy, such as representative democracy, direct democracy, deliberative democracy, and so on (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023).

This approach contributes to Doorenpleet’s (2015, p. 469) call to put people at the center of democracy measurement as a counter-movement to democracy research, which has reinforced the idea that democracy is primarily a domain of the state with its procedures, institutions and political elites. And this approach, in all its diversity, is ultimately a singular conception of democracy that is at the same time open to decentralization of democratic scholarship (Fleuß, 2021) and flexible enough to reflect innovations and future conceptions of democracy.

4 Illustrating case studies: Singapore, Ghana, and Ireland

Every empirically identifiable meaning of democracy must be evaluated to determine whether the core concept of political self-efficacy of all citizens is possible. The established parliamentary models of democracy seem to no longer fulfil the political self-efficacy of the people to a sufficient degree, as discussed in the enormous discourse of crisis of democracy in the last decades (f.e. Keane, 2009; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2019; Mounk, 2022; van Beeck, 2022). Processes of additional parliamentary deliberations and consultations, for example, represent a very popularly discussed alternative possibility for political debate in parliamentary institutions and provide the basis for the elites’ assertion that the public interest is represented in policy formulation. Such a process can involve individuals or groups in state-supported or state-sponsored paths of political participation, thereby helping them to achieve political self-efficacy beyond the election. At the same time, the dominant political and bureaucratic elites are granted greater control over who participates and how this is implemented, and can thus limit or even prevent the political self-efficacy of selected population groups (Rodan, 2018, p. 31). In this case, there can no longer be any question of democracy.

This section employs three case studies to illustrate the extent to which the functionalist approach, which conceptualizes democracy in terms of a fundamental principle rather than institutions, permits the differentiation between democracy and non-democracies. Singapore, as the first empirical case, illustrates a sanctimonious justification strategy of using Confucian and communitarian values to establish a façade of deliberative and consultative forms of participation that ultimately do not serve to expand the citizens’ opportunities for participation but to secure control over civil society and the legitimacy of the political system. Even if it looks like democratic participation, the deliberative and consultative forms of participation in Singapore do not enable the citizens’ political self-efficacy. As a second example, we take a look at the presidential democracy in Ghana. Here we can observe the strengthening of political self-efficacy through civil society organizations. Although people take part in the electoral process, they use civil society as a tool of social or bottom-up accountability to balance the weakness of horizontal accountability. The third and final case study focuses on Ireland and brings a Western case into the debate. Since Ireland had a longer history of political conflicts that lead to a legitimacy crisis in the country, it introduced – backed by scientific experts – the institution of citizen assemblies into the political process to rebuild trust in political institutions and strengthen political self-efficacy in the public.

4.1 Singapore: undermining democratic legitimacy from within through consultative participation

Against the background of liberal democracy, all terms used to describe Singapore in the literature (Hadenius and Teorell, 2006; Ortmann, 2011; Schedler, 2013; Geddes et al., 2014; Morgenbesser, 2020) consider Singapore’s combination of formal democratic institutions with autocratic ruling practices. Since 1959, the government has been under the control of one and the same party, the PAP (People’s Action Party). Since that time, the government has been confirmed by regular elections (last decade, e.g., 75.3% in 2001, 66.6% in 2006, 60.1% in 2011, 69.9% in 2015; see Elections Department Singapore). Opposition parties are tolerated but systematically disadvantaged, so that party competition is restricted. This implies that the elections are free, but not fair.

Physical repression to maintain power is rather secondary. Politically undesirable action is enforced through more or less subtle techniques of social control and depoliticization of citizenship (George, 2007). At the same time, citizens are politically co-opted by a pronounced dependence on the state through access to housing, employment, business contracts and personal savings (Rodan and Hughes, 2014). What the government of Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (1959–1990) recognized early on was that without improvements in the material living conditions of the citizens, neither ideological appeals nor repression could guarantee the maintenance of power (Rodan, 2008, p. 263). Therefore, the achievement and preservation of general prosperity has always had a high priority in the PAP’s calculation of power. Since independence in 1965, the city-state has developed into one of the wealthiest non-oil-exporting countries in the world (Ventura, 2024).

Additionally, the one-party rule of the PAP is closely linked to the successful establishment of the ideology of pragmatism. The PAP “deploys the rhetoric of pragmatism to link the notion of Singapore’s impressive success and future prospects to its ability to attract global capital” (Tan, 2012c, p. 67). This success, however, is always considered as fragile. With reference to Singapore’s size, possible economic crises, the outbreak of disease, terrorism, religious and racial conflicts as well as the volatile relations with its neighbors Malaysia and Indonesia, speeches, reports and interviews of the state-directed media repeatedly refer to the specific national challenges which Singapore has successfully fought against in the past to “come from the Third World to the First” (Yew, 2012) and which must be fought against in the future in order to preserve Singapore’s success (Tan, 2012c, p. 70). For decades, Singapore’s ruling elite has tried to legitimize its rule by claiming to be a talented and competent elite that has made Singapore an exception among its neighbors.

Additionally, the PAP in Singapore instrumentalized the Asian values debate (Kausikan, 1997) to strengthen the commitment to the collective through individual interests in business, politics and social life. As a basis for government, the value of the national was placed above the community, the value of the community above the self, the family as a basic unit of society was formulated, and consensus was placed above contest—i.e. communitarianism (Chua, 2018, p. 659). As Chua (2017) notes, the PAP’s governing philosophy of society over the individual has been historically flexible, drawing on notions of communitarianism and “Asian values,” also tying into the parameters of the PAP’s social democratic origins as a political party founded on the doorstep of Singaporean political independence. The nationalization of land for public housing, the role of sovereign wealth funds and industry alignment strategies, and the management of racial, cultural, and linguistic diversity in the service of “racial harmony” are just a few examples that illustrate these policies (Lim, 2018).

What we can observe here is what Thompson calls “reactionary culturalism” (Thompson, 2019). This term refers to a strategy of legitimation that “is based on the perception of particularistic national or cultural values, notions of ethical rule and rejection of a foreign ‘other’” (Barr, 2020, p. 2). The initiated Asian values discourse was nothing less than a Confucian revival to prepare a social ground for “the importance of an ethical rule embedded in Confucianism in the midst of rapid economic modernization while resolutely resisting steps towards political liberalization” (Thompson, 2019, p. 78). Pragmatic Confucian democracy,2 which also differs from communitarian Deweyian democracy (Dewey, 1981; Tan and Whalen-Bridge, 2008),3 derives its value “from its institutional and instrumental ability to effectively and legitimately coordinate complex social interactions among citizens with different moral and material interests” (Kim, 2017, p. 244–45). The emphasis on communitarian or Confucian ideas can not only be found in Singapore, but also in other Asian countries like Meiji Japan or post-Mao China, and the Prussian way (instead of Confucianism) in Imperial Germany as a historical European example (Thompson, 2019).

In order to remain within the democratic discourse, however, two fundamental ideas of democracy had to be reinterpreted by the Singaporean government: rule of law and political representation. Building on the argumentation that puts the public above individual rights, the British common law tradition would have to be adapted to local specificities, which is why certain laws would have to be used to guarantee the national survival and security of the island state. Only then could the law be fairly and equally applied to all individuals and the government. As a result, many conventional freedoms and civil society activities are restricted in Singapore. The special geopolitical context of Singapore must also serve to justify the redefining of the conditions of electoral democracy in terms of economic success and political and social stability. The principle of trusteeship over collective interests was placed above the representation of the interests of constituencies. The Asian Model of Democracy, or Asian Governance Model as Gilley (2014) put it, stands for a strong state that focuses on the delivery of economic growth, political stability, public order, efficient services, and the like, while emphasizing that the public good takes precedence over more particular interests.

It should also be made clear at this point that cultural differences and their influence on the meaning of democracy should not be denied, but that it is important to point out that authoritarian rulers like those in Singapore instrumentalize and politicize cultural differences “in order to reject ‘Western’ democracy in the name of ‘Asian values’” (Tan, 2012c, p. 79). What Gilley (2014) called the Asian Governance Model is based on the tradition of Confucian communitarianism. In this tradition of thought, the interest and values of the community take priority over those of the individual. Political problems always focus on the community, not the individual. The community or collective interests and values can replace individual interests and values. A conflict of individual rights and interests with the interests of the state or society does not exist in Confucian social and political theory (Hall and Ames, 1998; Wong, 2011). In this logic, a strengthening of the state’s power and an orientation toward elitism appear to make sense. The stronger the state, the more likely it is to guarantee that the individual can achieve his or her interests (Hu, 2007). Emphasizing precisely these norms and values, the PAP in Singapore has, as stated above, successfully legitimized its rule for decades.

The first time in the 1980s and more recently again in the 2011 and 2020 elections, the PAP lost a substantial share of the vote to the opposition. Since the 1980s, the PAP has tried to address this development with the strategy, or ideology, as Rodan (2018) calls it, of consultative representation.

Consultative representation “emphasizes the problem-solving benefits of involving stakeholders, interests, and/or expertise in public policy processes to ensure more effective functioning of economic, social, or political governance. These ideologies privilege such problem-solving over political competition, thereby limiting the political space for competing normative positions on fundamental public policy goals through the new space of technocratic governance. Importantly, broad consultation with experts and other groups and individuals in the context of deliberative or consultative representation does not infer or imply collective or equal power in decision-making, nor does it imply that those consulted have any democratic authority to represent others” (Rodan, 2018, p. 30–31).

Consultative ideologies promote the depolarization of a society, but they do so through a process that relegates the political character of decision-making to the background in order to increase political control (Burnham, 2001), not political self-efficacy. He and Warren (2011) refer to this controlled form of participation, which is widespread in authoritarian regimes in Asia, as deliberative authoritarianism.

One of the first reactions to the seat gains of the opposition was the introduction of non-constituency members of parliament (NCMPs) in 1984, which gave the opposition’s strongest losers in the general election at least three seats with limited voting rights. By providing NCMPs in a PAP-controlled environment, the PAP hoped to demonstrate the uselessness of the opposition while appearing tolerant of it (Rodan, 2018). The strategy to increase opportunities for political and public participation included parliamentary government committees, periodic large-scale public surveys, and the formation of a public policy think tank, the Institute of Public Policy. On the one hand, this opened the possibility for the university-educated Singaporean middle class to help shape public policy in the elite meritocracy of the PAP, and on the other, to respond to the profound problem of how to channel the concerns of social forces into institutional channels that would then in turn support technocratic approaches and solutions to social conflict.

One of the key pieces of the PAP strategy to promote alternatives to competitive party politics was the establishment of the Feedback Unit (FU) within the Ministry of Community Development in 1985, which was renamed “Reaching Everyone for Active Citizenship @ Home” (REACH) in 2006. Its purpose was to facilitate individual and group feedback on public policy, as well as to disseminate information on government policies. Over time, the program developed a variety of electronic and in-person mechanisms to engage the public, mostly as individuals but also in selected forms of group consultations. Another example of such consultative instruments was the creation of the nominated members of parliament in 1990, which allows non-elected members of parliament (NMPs) to incorporate. The NMPs were explicitly intended as an alternative to democratic representation. They are publicly nominated by a special parliamentary committee dominated by the PAP, which makes recommendations on who should be appointed. Appointed NMPs have voting rights which are comparable to those of NCMPs.

It is significant that while this arrangement initially placed a great deal of emphasis on the individual expertise and professional qualifications of appointees, consistent with the elitist ideologies of the PAP, it was increasingly accompanied and guided by attempts to absorb new social forces and manage conflicts (Rodan, 2018, p. 49–51). While consultative processes should always take place outside the formal institutions, in Singapore the idea of democratic legitimacy is undermined from within through consultative participation (Rodan, 2018, p. 31).

With Taylor (1993), the communitarian debate also centers on the question of the social conditions under which the ideal of political self-efficacy can be realized. Like Walzer (1993) and Taylor (1993) sees civil society as a corrective to societies in which politics is primarily mediated by the state and the bureaucracy. On the one hand, state- and trans-state-sponsored participation is possible in Singapore as administrative involvement in the form of REACH, for example, and social involvement in the form of NMPs. On the other hand, however, state-autonomous participation in the form of individualized political expression in blogs or petitions, and in the form of civil society expression in the form of political parties, social movements and the like, is repressed (Rodan, 2008, p. 34). In the case of Singapore, there is no question of political self-efficacy in the sense of the communitarian debate, and certainly not in the sense of the republicanist debate.

4.2 Ghana: civil society as a potential facilitator of self-efficacy

Ghana’s transition to democracy in 1992 aligns it with the broader global development of the time, in which African authoritarian regimes were forced to implement democratic political reforms. This aligns it with the so-called “third wave” of democratisation, as defined by Huntington (1991). Since then and after the military regime of Jerry John Rawlings, Ghana’s democracy has continued to develop further, establishing a liberal democratic regime with a multiparty system. As a result, Ghana is often praised as a model of democracy in Africa (Botchway, 2018, p. 1; Asare and Frempong, 2019). Political violence is rare, and the West African country has experienced several peaceful transitions of power between the two rival political parties, which is considered one of the essential indicators of a consolidated democracy. The two dominant political parties in Ghana are the NPP (New Patriotic Party) and the NDC (National Democratic Congress), which compete in presidential elections and general elections for office.

Voter turnout in general elections is consistently between 60% (53.75% in 1992) and 80% (85% in 2008 and 78.89% in 2020), in presidential elections even higher. It can be argued that multi-party elections in Ghana enjoy considerable support. Furthermore, the electoral process in Ghana can be considered a success, despite some irregularities since its inception. This can be attributed primarily to the Ghana Electoral Commission. Its independent position, justified by the constitution, protects it to a large extent from the influence of the respective executive branch (Ayee, 1997; Gyekye-Jandoh, 2013).

The people of Ghana view elections as an important decision for choosing leaders, an expression of a popular consensus that “military rule should be a thing of the past” (Kumah-Abiwu and Darkwa, 2020) and to ensure that elections are credible (Abdul-Gafaru and Crawford, 2010). However, beyond this, voting participation in Ghana remains low. At the same time, the question of consolidated democracy is about much more than the peaceful transfer of power from one party to another, and also about much more than the friendly resolution of conflicts in connection with elections (Botchway, 2018, p. 10). A number of problems remain, including the abuse of power by the executive branch, corruption in the judiciary, unequal application of laws, the existence of paramilitary groups, and much more (Botchway, 2018, p. 11).

Based on these assumptions, we now turn to the societal level. It can be argued that the strength of Ghana’s democracy lies in its civil society, which is considered one of the key players in Ghanaian democracy (Gyimah-Boadi, 2009). Following Lindberg’s (2006, p. 146–148) assumptions, civil society organizations are one of a total of six issues that link repeated elections to improvements in civil liberties and/or democratic progress in transitional societies.

Arthur (2010, p. 211) writes that civil society organizations (CSOs) “have played crucial roles in deepening and sustaining the democratic process in Ghana.” These civil society organizations protected the values of various groups, shaped public opinion, influenced public policy and functioned as watchdog organizations (Arthur, 2010, p. 211–212). On the one hand, they mobilize citizens to participate in elections, join political parties and induce policy-related issues. Conversely, they monitor the electoral processes, campaign for a transparent policy-making process and keep an eye on the military (Arthur, 2010, p. 211–212). In summary, the active engagement of civil society in important areas of democratic progress creates the necessary incentives for democracy-friendly ideas to take root in a society (Kumah-Abiwu and Darkwa, 2020).

In order to demonstrate the impact of CSOs on the democratic development in Ghana more systematically, we describe their activities in five areas of CSO action as examples: Monitoring, advocacy, innovation, service delivery and capacity building (Najam, 2000; Botchway, 2018). The greatest strength of Ghanaian civil society organizations lies in their role as a monitoring body. This monitoring, defined here as a mechanism that ensures the honesty of policy, involves monitoring and evaluating government institutions and the effectiveness of government processes. The Institute for Democratic Governance (IDEG) is a significant example of monitor agents in Ghana, who not only monitor elections but also the behaviour of politicians, government policy or parliament. The results of the monitoring are regularly passed back to the respective institutions and shared with other civil society actors. The formation of coalitions between different civil society actors, as exemplified by the Centre for Democratic Development (CDD) and the Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO) impressively illustrates, further strengthens the effectiveness of the respective efforts. Between 2000 and 2018, for example, CODEO succeeded in training approximately five thousand election observers. In addition to this, in 2010, the Civic Forum Initiative (CFI) collaborated with the Governance Issues Forum (GIF) to establish platforms for voters and community members in selected districts. These platforms were designed to educate and empower voters to make informed choices about candidates, election issues, and their respective roles and responsibilities in community development (Gyimah-Boadi, 2009; Quashigah, 2016).

Furthermore, platforms of this nature provide an equal opportunity for all candidates to present themselves to voters. In addition, the diversity of CFI members brings a wealth of knowledge and experience to the planning, strategizing, and implementation of activities that promote national cohesion and long-term development, which in turn promotes the deepening of democracy. The intervention of civil society, combined with the vigilance of the media, has also made election campaigns largely issue-based and peaceful (Botchway, 2018, p. 9).

The second area, advocacy, refers to the role of CSOs in leading the various advocacy efforts. This consequently encompasses the many activities that CSOs undertake, such as media campaigns, public speaking, commissioning and publishing research, and conducting opinion polls, to name a few. For instance, the lobbying efforts of the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) have ensured that various civil society organizations and interest groups, as well as independent experts, have been able to submit statements and memoranda on proposed legislation before parliament. This new openness and collaboration greatly expands public participation in policymaking and supports the overall deliberative process in the country (Gyimah-Boadi, 1998). In addition to this, the IEA’s Ghana Political Parties Programme (GPPP) has facilitated a collaborative process between Ghana’s major political parties and the IEA, with the aim of considering and refining proposed legislation. This includes the Political Parties Public Financing Act, the Political Parties Act, and the Presidential Transition Act, which collectively aim to enhance the deepening of democracy and good governance in Ghana (Botchway, 2018, pp. 9–11).

Civil society organizations have made an enormous contribution to peacebuilding, particularly by ensuring multiparty democracy. In 2003, for example, the IEA brought together the general secretaries of the various political parties to bridge the gap and apparent enmity that had existed until then between the political parties in the country, particularly between the NDC and NPP. With the help of the Party Advisory Committee IPAC, as another example, it has been possible to find compromise solutions for many contentious detailed issues surrounding, for example, parliamentary and presidential elections (Frempong, 2008).

In terms of CSO-work and civic engagement, CSOs provide services in the governance process, particularly to marginalized and underserved populations. Such services include educating citizens on a range of public interest issues and providing them with opportunities to learn about these issues. With this in the background, IDEG has been organizing regular debates of parliamentary candidates since 2004. This greatly helps a multi-ethnic society like Ghana to focus the voters’ attention on issue-based politics rather than on ethnic, personal and neglected issues. One of the key services provided by the IEA to the Ghanaians is the organisation of presidential and vice-presidential debates. While elections are undoubtedly an important mechanism for popular control of government, they are only effective if there are institutions in place to ensure ongoing government accountability to the public (Beetham, 2004). The IEA presidential debate represents one of several potential avenues for the promotion of good governance and democratic consolidation (Botchway, 2018, pp. 12–13).

CSOs engaged in capacity building seek to provide support to communities, government institutions, or other CSOs and related entities. Citizen education, in particular, has an important role to play in this regard. It is assumed that the empowerment of citizens and their participation in the political process will eventually spill over into other areas of the citizens’ social life. By promoting civic and political capacity development through capacity building, many CSOs in Ghana, particularly the IEA, CDD, and IDEG, serve as “free schools for democracy” (Gyimah-Boadi, 1998; Botchway, 2018, p. 13–14).

It is important to note, however, that it is not always easy for civil society organizations and citizens in general to be included in the Ghanaian political process. As Awal and Paller note, “Citizens and civil society have to wrestle political space for themselves” (Awal and Paller, 2016, p. 3). This can be seen on behalf of the decentralization process in Ghana. The established decentralized governing system should facilitate engagement with the citizens at the local level (see Crawford, 2009), but the findings are disillusioning. Crawford shows that electoral participation, attendance at local assemblies and the contact to local representatives had been quite high (Crawford, 2009, p. 64–65), which could be interpreted as a positive indicator for a vibrant democracy. On the other hand, his findings show that there is a lack of “accountability of elected representatives to the public and the district executive to elected representatives” (Crawford, 2009, p. 75). As Awal and Paller observe, the decentralization process “has in effect been used as a political tool to maintain central government control” (Awal and Paller, 2016, p. 3). Consequently, this decentralization process did not result in a responsive government, which could in the long run strengthen democracy and thereby the self-efficacy of the citizens. Nevertheless, we wish to summarize with Botchway (2018) that civil society organizations in Ghana are capable to reinforcing civic virtues in Ghanaian society, thus increasing the citizens’ “attention to public good, habits of cooperation, toleration, respect for others and for the rule of law, willingness to participate in public life, self-confidence and efficacy” (Botchway, 2018, p. 15) at the local and national levels.

The kind of democracy observed in Ghana can be related to the concept of “monitory democracy,” which describes a new form of “post-parliamentary democracy” or post-representative democracy (Keane, 2009, 2011). Monitory democracy can be “defined by the growth of many different power-scrutinizing mechanisms and by their spreading influence within the fields of government and civil society” (Keane, 2011, p. 204). While elections are an important aspect of democracy, they are not the sole defining factor (Keane, 2001). Inside and outside states, independent observers of power are beginning to have a significant impact. “By keeping politicians, parties, and elected governments permanently on their toes” (Keane, 2011, p. 205), they challenge their authority, force transparency and accountability, compliance with norms, and in some cases force them to change their plans.

It can be observed that citizens or citizen organizations, as evidenced by the example of Ghana, play a key role in controlling governments (bottom-up accountability). Political self-efficacy might be gained not only through elections, but by participating in various forms of watchdog organizations on local, national and transnational levels. These civil society organizations have an impact on the decision-making process from outside the political system and thereby maybe serve as correctives of the weakened horizontal accountability of the political system. The new power-restricting innovations of monitory democracy mean that many more citizens can raise their voices. In contrast to representative democracy, which is based on the principle of one person, one vote, one representative, the concept of monitory democracy espouses a more inclusive approach, recognizing the multiplicity of interests and voices within a given population. This is reflected in the observation by Keane (2011, p. 207) that “one person, many interests, many voices, multiple votes, multiple representatives” is the central demand in the struggle for representative democracy. These effects of monitory democracy strengthen the political self-efficacy of individuals, even in societies characterised by significant heterogeneity, such as Ghana.

4.3 Ireland: strengthening self-efficacy through citizen assemblies

Implementing deliberative systems and mechanisms like mini-publics into political decision-making processes has become a key factor in the last decade, with the aim to strengthen democracy (Parkinson and Mansbridge, 2012; Beauvais and Warren, 2019; Dryzek et al., 2019). The citizen assemblies which have been implemented in Ireland since the beginning of the 2010s are an example of this trend. The objective was to rebuild trust in the political system and its institutions and to include citizens’ opinions in a meaningful way to improve the structure of the political system and to discuss openly about key policy challenges in the country. This means that citizen assemblies are also an instrument for restoring a sense of political self-efficacy in the public sphere.

In Ireland, the process started in 2011 with a first pilot assembly, themed “We the Citizens” (Farrell et al., 2013; O’Malley et al., 2020). Between 2012 and 2014 the Irish Constitutional Convention (ICC) became the first nation-wide citizen assembly of 100 people. Two-thirds of the assembly were randomly chosen citizens, while the remainder consisted of a chair-person and 33 politicians (Suiter et al., 2016, p. 34–35; www.constitutionalconvention.ie) with the majority of randomly chosen citizens. This assembly discussed 10 topics related to the reform of the Irish constitution (Suiter et al., 2016; Farrell et al., 2020) and resulted in two referenda on marriage equality in 2015 (Suiter and Reidy, 2020) and blasphemy in 2018 (Suiter et al., 2020).

Between 2016 and 2018, a second citizens’ assembly was convened (Farrell et al., 2019), consisting of a chairperson and 99 randomly selected citizens. This assembly discussed five key topics, including fixed term parliaments or climate change (Devaney et al., 2020; Muradova et al., 2020; McGovern and Thorne, 2021). The discussion also led to a referendum on abortion rights in 2018 (Suiter, 2018; Elkink et al., 2020; Suiter and Reidy, 2020; Farrell et al., 2023). Since that time, additional assemblies have been held on various topics: a Citizens’ Assembly on Gender Equality (2019–2021), a Dublin Citizens’ Assembly (2022), a Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss (2022) and recently a Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use (2023/24).

These assemblies have demonstrated that citizens are willing and able to participate in meaningful deliberative processes, but also that in case of the resulting referenda the turnout rates had been higher compared to previous ones. The results of these referenda reflected the policy recommendations of these various assemblies. Therefore, these assemblies have had an impact on the participants and on the Irish society as a whole.

It can be reasonably assumed that deliberative tools such as citizen assemblies or mini-publics will have a positive effect on the political self-efficacy of both participants (direct effect) and the public as a whole (indirect effect). As Farrell et al. (2013, p. 106) indicate, participation in the “We the Citizen” assembly in 2011 increased the sense of efficacy, the interest in politics and the willingness to become more involved in politics. These findings confirm previous research indicating that an increase in political efficacy occurs when people hear that mini-publics affected support for policies (Boulianne, 2018) or when they participated in a deliberative event (Boulianne, 2019). Additionally, recent findings by Knobloch et al. (2020) show that greater exposure to and confidence in deliberative outputs, such as Citizens’ Initiative Review Statements can lead to higher levels of internal and external efficacy. Therefore, both positive direct (participants) and indirect effects (citizenry) can be identified by the implementation of meaningful citizen assemblies or mini-publics.

The citizen assemblies in Ireland are integrated into the classical process of political decision-making in various ways. Firstly, they are institutionalized for a specific period of time. Secondly, they have specific topics which they should focus on during this time period, although they are still open to expand the topics as seen with the ICC. Third, they are sometimes mixed-member institutions that bring together both lay citizens and professional politicians to discuss the topics at hand with experts. Fourth, they are open for submissions by the wider public on the topics discussed, which allows for the inclusion of additional opinions. Fifth, at the conclusion of the deliberative process they vote for specific decisions and therefore send a clear sign to the parliament and the wider public. Sixth, the assemblies formulate recommendations for the Irish parliament which are publicly accessible. As Suiter et al. (2016, p. 47) write concerning the ICC: “its role was advisory rather than declaratory.” As previously stated, some of the topics ended in referenda, while other recommendations had been sent to relevant parliamentary committees or government departments for further consideration (Suiter et al., 2016, p. 48).

These assemblies made it clear that they add to the political decision-making process and engaged citizens in the process beyond elections and referenda. Secondly, political parties continue to play a pivotal role in interest aggregation and articulation, and they are not supplanted by these new institutions. This results in a higher acceptance of the assemblies’ outputs by politicians in parliament. Thirdly, the political discussions in the assemblies can be transmitted through media such as websites (which serve as public archives) and can therefore educate the citizens concerning the broader process.

The Irish example demonstrates how democratic innovations like citizen assemblies can strengthen both liberal and republican norms and values. They bring in “ordinary people” in the political process and strengthen their feeling of political self-efficacy. These people then can serve as multiplicators through their self-made experience, how difficult it is to find solutions for various societal problems. And they also reduce the “imagined distance” between politicians and citizens, which has been criticized in the debate of “post-democracy” (Crouch, 2004) as a major fallacy of representative democracies.

Therefore, these assemblies function as bridging institutions that not only bring together citizens from different spheres of society, but also citizens and professional politicians (and experts). In this way they have a double-bridging function (citizens-citizens and citizens-politicians) and may also strengthen a sense of community and therefore communitarian values to kind of build a “strong democracy” (Barber, 2003 [1984]) on the Irish national level. As Deligiaouri and Suiter (2023) recently proposed, this kind of enhanced representative democracy can be labeled “hybrid representative democracy” and is a model in which “representation and sortition can complement each other” (2023, p. 140) and a type of “collaborative governance” (Devaney et al., 2020, p. 145; also Ansell, 2012).

5 Conclusion

In this article we refer to the configurations of democracy as a new global core concept of democracy which focuses on the role of the citizens´ political self-efficacy as its basic principle. All conceptions of democracy with all their specific institutional settings have to serve this principle. Political self-efficacy refers to the citizens’ central role in political opinion-forming and decision-making processes. Every political system must be measured by whether the established institutions serve this basic principle.

Within the configurations of democracy, theoretical principals, such as liberalism, communitarianism and republicanism are defined. Different concepts of democracy are based on theoretical principles, which require specific institutional arrangements and practices. In its original form, liberalism assumes that citizens can express their interests and integrate them into the political system through civil society and political actors. It is the responsibility of politics to translate particular interests into a common good outcome through consensus or compromise (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023, p. 84). In liberalism, “the common good is achieved through the implementation of particular interests that are capable of winning a majority” (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023, p. 84). Republicanism is understood as a countermovement to liberalism. In contrast to liberalism, which focuses on the individual, republicanism prioritizes the community. In contrast to republicanism, communitarianism is similar in that it is also concerned with the communitas, the shared life of the people who form a community. However, while republicans are concerned with the res publica, the common good, in the sense of a community of self-governing citizens who are oriented towards the common good, communitarians are concerned with the communitas. While republicanism is based on the political self-efficacy of the individual and therefore enables and protects it, communitarianism is not focused on the individual, but only on the community. The two modes of thought share a commonality in their respective emphases on the social person, as opposed to the individualistic notions of freedom and individual rights espoused by liberalism (Dagger, 2004; Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023, p. 84). From an institutional perspective, this means that liberal democracy is oriented towards the logic of presidentialism and parliamentarism, while deliberative models of democracy are the institutional counterpart of republicanism. The concept of democratic configurations suggests that institutionally defined criteria serve the normative core of democracy in various ways, promoting the political self-efficacy of citizens (Osterberg-Kaufmann et al., 2023, p. 84).

In this respect, the preliminary examples of Singapore, Ghana and Ireland illustrate various aspects that arise from the respective institutionalization of republican, communitarian and liberal considerations: Singapore comes quite close to communitarian, but its institutional implementation (NCMPs, FU, REACH, NMPs) shows mechanisms that prevent rather than enable political self-efficacy because they disregard liberal rights and norms. In Ghana, on the other hand, we observe a different, non-institutional mechanism. Here, citizens strengthen their political self-efficacy by using civil society as a kind of bottom-up accountability mechanism, which is reflected in the idea of “monitory democracy” (Keane, 2009). This is a mechanism that can also be observed elsewhere, for example in Japan as a reaction to corruption in Japanese politics (Hirata, 2004). In Ireland, the implementation of citizen assemblies as a tool to improve the public discourse on various political issues helps in two ways. On the one hand the new hybrid representative democracy sticks with the liberal representative tradition of democracy and therefore does not rebuild the system from the scratch. On the other hand, through these assemblies and the public discourse about them and the issues discussed it strengthens both republican and communitarian values because it bridges the crucial gap between the public and politics and serves the participatory wishes of the citizens. It takes them serious and thereby improves the political self-efficacy of the citizens both directly (through engagement) and indirectly (through witnessing the engagement via the public discourse).

The idea of placing political self-efficacy at the center of a global configuration of democracy broadens the view of the concept of democracy and also allows more conceptual flexibility. On this basis, it is possible to examine the degree of political self-efficacy that respective political systems ensure and to better understand the different ways in which these possibilities are institutionalized in the context of different social values and norms. And, what the illustrating cases have shown, this functionalistic approach clearly allows to distinguish between democracy and autocracy. It is possible to operationalize and monitor certain institutional conditions. However, observing whether a function is fulfilled or not requires a much more interpretive approach. Democracy is more than free elections or other mechanisms for choosing rulers. Democracy is a way of life, and political self-efficacy is the best way to help shape the concrete expression of that way of life.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NO-K: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CM-K: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Duisburg-Essen.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ In accordance with Kelsen’s (1925) assertion, those whose lives are affected by political decisions must also be able to perceive themselves as the authors of these decisions. In representative democracy, the political self-efficacy that this implies is institutionalized through the election of representatives by those they represent (Merkel, 2023, p. 15).

2.^ For the general debate on Confucianism and democracy, we would like to refer to the work of Tan (2012a, 2012b).

3.^ Dewey (1981) understands democracy, in contrast to the Schumpeter (1942) understanding of democracy as a method, as a lifestyle and habitus of democratic citizens who enjoy popular sovereignty, self-government and political equality.

References

1

Abdul-Gafaru A. Crawford G. (2010). Consolidating democracy in Ghana: progress and prospects?Democratization17, 26–67. doi: 10.1080/13510340903453674

2

Ansell C. (2012). “Collaborative governance” in The Oxford handbook of governance. ed. Levi-FaurD. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 498–511.

3

Arthur P. (2010). Democratic consolidation in Ghana: the role and contribution of the media, civil society and state institutions. Commonwealth Comp. Polit.48, 203–226. doi: 10.1080/14662041003672510

4

Asare B. Frempong A. (2019). Selected issues in Ghana's democracy. Tema, Ghana: Digibooks Ghana Ltd.

5

Asenbaum H. (2022). Rethinking democratic innovations: a look through the kaleidoscope of democratic theory. Political Studies Rev. 20, 680–690.doi: 10.1177/16094069221105072

6

Awal M. Paller J. (2016). Who really governs urban Ghana? Africa Research Institute. Available at: https://media.africaportal.org/documents/ARI-CP-WhoReallyGovernsUrbanGhana-download.pdf (Accessed April 01, 2021).

7

Ayee J. (1997). The December 1996 general elections in Ghana. Elect. Stud.16, 416–427. doi: 10.1016/S0261-3794(97)84379-X

8

Barber B. (2003). Strong democracy. Participatory politics for a new age. Berkeley u.a: University of California Press.

9

Barr M. (2020). Authoritarian modernism in East Asia. J. Contemp. Asia50, 675–678. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2019.1650196

10

Beauvais E. Warren M. E. (2019). What can deliberative mini-publics contribute to democratic systems?Eur. J. Polit. Res.58, 893–914. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12303

11

Beetham D. (2004). Towards a universal framework for democracy assessment. Democratization11, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13510340412331294182

12

Berg-Schlosser D. (2004). Democratization: The state of the art. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

13

Botchway T. (2018). Civil society and the consolidation of democracy in Ghana’s fourth republic. Cogent Soc. Sci.4, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2018.1452840

14

Boulianne S. (2018). Mini-publics and public opinion: two survey-based experiments. Polit. Stud.66, 119–136. doi: 10.1177/0032321717723507

15

Boulianne S. (2019). Building faith in democracy: deliberative events. Polit. Trust Efficacy Polit. Stud.67, 4–30. doi: 10.1177/0032321718761466

16

Braizat F. (2010). What Arabs think. J. Democr.21, 131–138. doi: 10.1353/jod.2010.0015

17

Bratton M. (2010). Anchoring the "D-word" in Africa. J. Democr.21, 106–113. doi: 10.1353/jod.2010.0006

18

Bratton M. Mattes R. (2001). Support for democracy in Africa: intrinsic or instrumental?“British Journal of. Policy. Sci.31, 447–474. doi: 10.1017/S0007123401000175

19

Burnham P. (2001). New labour and the politics of depoliticisation. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat.3, 127–149. doi: 10.1111/1467-856X.00054

20

Canache D. (2012). Citizens’ conceptualizations of democracy. Comp. Pol. Stud.45, 1132–1158. doi: 10.1177/0010414011434009

21

Carothers T. (2002). The end of the transition paradigm. J. Democr.13, 5–21. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0003

22

Chakrabarty D. (2008). Provincializing Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

23

Cho Y. (2015). How well are global citizenries informed about democracy? Ascertaining the breadth and distribution of their democratic enlightenment and its sources. Polit. Stud.63, 240–258. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12088

24

Chong J. Osterberg-Kaufmann N. (2022). Post-democratizing politics in southeast and Northeast Asia. Pac. Aff.95, 417–440. doi: 10.5509/2022953417

25

Chu Y. Huang M. (2010). Solving an Asian Puzzle. J. Democr.21, 114–122. doi: 10.1353/jod.2010.0009

26

Chua B. (2017). Liberalism disavowed. New York: Cornell University Press.

27

Chua B. (2018). “Asian model of democracy” in The SAGE handbook of political sociology. eds. OuthwaiteW.TurnerS. P. (Los Angeles, A. O.: Sage), 652–668.

28

Coppedge M. Gerring J. Glynn A. Knutsen C. H. Lindberg S. I. Pemstein D. et al . (2020). Varieties of democracy: measuring two centuries of political change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

29

Crawford G. (2009). Making democracy a reality’? The politics of decentralisation and the limits to local democracy in Ghana. J. Contemp. Afr. Stud.27, 57–83. doi: 10.1080/02589000802576699

30

Crouch C. (2004). Post-Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

31

Dagger R. (2004). “Communitarianism and republicanism” in Handbook of political theory. eds. GausG. F.KukathasC. (London: Sage), 167–179.

32

Dahl R. A. (1971). Polyarchy. Participation and opposition. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

33

Dahl R. A. (1989). Democracy and its critics. The democratic process - and its future - as examined by one of the world's preeminent political theorist. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

34

Davis N. T. Goidel K. Zhao Y. (2021). The meanings of democracy among mass publics. Soc. Indic. Res.153, 849–921. doi: 10.1007/s11205-020-02517-2

35

Deligiaouri A. Suiter J. (2023). Oscillating between representation and participation in deliberative fora and the question of legitimacy: can ‘hybrid representative democracy’ be the remedy?Representation59, 137–153. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2021.1950040

36

Devaney L. Torney D. Brereton P. Coleman M. (2020). Ireland’s citizens’ assembly on climate change: lessons for deliberative public engagement and communication. Environ. Commun.14, 141–146. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2019.1708429

37

Dewey J. (1981). The philosophy of John Dewey. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

38

Diamond L. (2010). Introduction. J. Democr.21, 102–105. doi: 10.1353/jod.2010.0003

39

Doorenspleet R. (2015). Where are the people? A call for people-Centred concepts and measurements of democracy. Gov. Oppos.50, 469–494. doi: 10.1017/gov.2015.10

40

Dryzek J. S. Bächtiger A. Chambers S. Cohen J. Druckman J. N. Felicetti A. et al . (2019). The crisis of democracy and the science of deliberation. Science363, 1144–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw2694

41

Elkink J. A. Farrell D. M. Marien S. Reidy T. Suiter J. (2020). The death of conservative Ireland? The 2018 abortion referendum. Elect. Stud.65:102142. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102142

42

Farrell D. M. O’Malley D. Suiter J. (2013). Deliberative democracy in action Irish-style: the 2011 we the citizens pilot citizens’ assembly. Irish Polit. Stud.28, 99–113. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2012.745274

43

Farrell D. M. Suiter J. Cunningham K. Harris C. (2023). When Mini-publics and maxi-publics coincide: Ireland’s National Debate on abortion. Representation59, 55–73. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2020.1804441

44

Farrell D. M. Suiter J. Harris C. (2019). Systematizing’ constitutional deliberation: the 2016–18 citizens’ assembly in Ireland. Irish Pol. Stud.34, 113–123. doi: 10.1080/07907184.2018.1534832

45

Farrell D. M. Suiter J. Harris C. Cunningham K. (2020). The effects of mixed membership in a deliberative forum: the Irish constitutional convention of 2012–2014. Polit. Stud.68, 54–73. doi: 10.1177/0032321719830936

46

Fleuß D. (2021). Gagnon’s 'data mountain': a lookout point for revolutions to come. The Loop. ECPR’S Political Science Blog. Available at: https://theloop.ecpr.eu/gagnons-data-mountain-a-lookout-point-for-revolutions-to-come/ (Accessed January 30, 2024).

47

Frempong A. K. (2008). “Innovations in electoral politics in Ghana’s fourth republic: an analysis” in Democratic innovation in the south: Participation and representation in Asia, Africa and Latin America. eds. VorstC. R.DagninoE. (Buenos Aires: Clasco), 183–204.

48

Gaber R. (2000). “Demokratie in quantitativen Indizes: Ein mehr- oder eindimensionales Phänomen” in Demokratiemessung. Konzepte und Befunde im internationalen Vergleich. eds. LauthH. L.PickelG.WelzelC. (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien), 112–131.

49

Gagnon J.-P. Asenbaum H. Fleuss D. Bussu S. Guasti P. Dean R. et al . (2021). The marginalized democracies of the world. Democratic Theory8, 1–18. doi: 10.3167/dt.2021.080201

50

Gallie W. B. (1956). Art as an essentially contested concept. Philos. Q.6, 97–114. doi: 10.2307/2217217

51

Geddes B. Wright J. Frantz E. (2014). Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: a new data set. Perspect. Polit.12, 313–331. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714000851

52

George C. (2007). Consolidating authoritarian rule: calibrated coercion in Singapore. Pac. Rev.20, 127–145. doi: 10.1080/09512740701306782

53

Gilley B. (2014). The nature of Asian politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

54

Gyekye-Jandoh M. (2013). Electoral reform and gradual democratization in Africa: the case of Ghana. Afr. J. Soc. Sci.3, 74–92.

55

Gyimah-Boadi E. (1998). African ambiguities: the rebirth of African liberalism. J. Democr.9, 18–31. doi: 10.1353/jod.1998.0025

56

Gyimah-Boadi E. (2009). Another step forward for Ghana. J. Democr.20, 138–152. doi: 10.1353/jod.0.0065

57

Hadenius A. Teorell J. (2006). Authoritarian regimes: stability, change, and pathways to democracy, 1972-2003. Notre dame: Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies: Citeseer.

58

Häfner L. Landwehr C. Stallbaum L. (2023). German legislators‘conceptions of democracy and process preferences: results from a new survey. German Polit., 1–26. doi: 10.1080/09644008.2023.2279183

59

Hall D. L. Ames R. T. (1998). Thinking from the Han: Self, truth, and transcendence in Chinese and Western culture. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

60

He B. Warren M. E. (2011). Authoritarian deliberation: the deliberative turn in Chinese political development. Perspect. Polit.9, 269–289. doi: 10.1017/S1537592711000892

61

Held D. (2006). Models of democracy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

62

Hirata K. (2004). Civil society and Japan’s dysfunctional democracy. J. Dev. Soc.20, 107–124. doi: 10.1177/0169796X04048306

63

Hu S. (2007). Confucianism and contemporary Chinese politics. Policy Polit.35, 136–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-1346.2007.00051.x

64