- School of Communication and Media, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA, United States

This study expands previous research on political endorsements by focusing on the tone of the endorsement, rather than the endorser or the presence/absence of any endorsement at all. Using a 2×2 experimental design and a sample of 906 registered voters from a midwestern U.S. state, this study measures the effect of positive and negative endorsements on the voter perceptions of the endorsee, endorser, and unendorsed candidate during a partisan primary election campaign. Results support the idea that positive endorsements generally improve voters’ attitudes toward the endorsee and the endorser and negative endorsements generally hurt voters’ perception of the unendorsed candidate. Further interaction analyses show that factors such as a voter’s existing enthusiasm for politics, government, and politicians can moderate the effect of endorsements. The findings are in line with the proposition of the Social Judgment Theory and support the existing literature on the effect of endorsements.

1 Introduction

In highly competitive elections, candidates and their supporters look for any unique or compelling tactic to gain an advantage during the campaign. Moreover, when such an election takes place within the context of a highly polarized electorate, even swaying the smallest fraction of undecided voters with such a tactic may generate enough of an advantage to claim victory on election night. Kennedy’s shrewd use of television during his debates with Nixon (Donovan and Scherer, 1992), and Obama’s early use of social media and data mining (Aaker and Chang, 2009), demonstrated the impact that can result from incorporating new and unique tactics into the campaign.

In other cases, finding different ways to utilize established tactics can provide similar advantages. Hoover’s presidential victory in 1928 is credited in part to Republicans’ focus on economic issues, as exemplified in their promise of “a chicken for every pot” (State Historical Society of Iowa, 1928). Over half a century later, Democrat Bill Clinton would update this tactic by reminding voters in the 1992 presidential election that “It’s the economy, stupid” (Rosenthal, 1992). Similarly, the use of political endorsements is a long-established campaign tactic that has endured, in part, because of the way campaigns have adapted such endorsements to extend their salience, relevancy, and effectiveness. Often, the success of a political endorsement is attributed to the persuasiveness and effectiveness of the endorser, whether it be an organization (i.e., political party, newspaper, media outlet), a celebrity, or a political elite (Jackson and Darrow, 2005; Chou, 2015; Fahey et al., 2018). However, beyond the source, general persuasion research argues that the message itself contributes to the effectiveness of any persuasive message such as endorsement statements (Perloff, 2017). Perloff notes that the effectiveness of the message itself can be influenced by a series of factors, including the structure of the message, the content of the message, and the language used to convey the persuasive appeal. Despite the obvious importance of the persuasive message itself, existing research on political endorsements is generally more focused on the source rather than the content of any endorsement statement. This study examines the effect of the language and tone of an endorsement statement on voter attitudes and enthusiasm.

2 Impact of endorsements

Previous literature examining the impact of endorsements on specific elections indicates the importance of considering the type of endorser. Studies have considered the effectiveness of endorsements from groups or organizations such as newspapers (Fahey et al., 2018), political parties (Kousser et al., 2015), and advocacy groups (Gerber and Phillips, 2003). Others have examined the effectiveness of endorsement provided by an individual such as a celebrity or a political figure (Jackson and Darrow, 2005; Vining and Wilhelm, 2011). Endorsements by celebrities or political figures can have different effects; with respect to political figures, Summary (2010) notes that such endorsements are “a key variable in understanding candidate performance in the primaries and caucuses” (p. 285).

When specifically examining the impact of endorsements from political figures or political elites, the extant literature shows that such elites engage in a wide variety of elections, including ballot initiatives (Bullock, 2011), judicial elections (Vining and Wilhelm, 2011), intra-party primary elections (Cancela et al., 2016; Vizcarrondo, 2021), and general elections (Nicholson, 2011; Vizcarrondo and Painter, 2020). Some of these studies have incorporated experimental designs which allow for the measurement of causal relationships (Gay and Airasian, 2002). In some cases, endorsements were found to be effective, but issue-related information was at least as influential (Bullock, 2011).

On the other hand, endorsements could also lead to unintended effects: In his study featuring a ballot initiative, Nicholson (2011) observed a backlash effect among supporters of the non-endorsed issue, who became more polarized and engaged because of the endorsement. Similarly, Vizcarrondo and Painter (2020) observed that elite endorsements studied during the 2018 midterm elections resulted in a backlash effect, specifically on low-information voters’ evaluations of the endorsed candidate. Finally, Vizcarrondo (2021) studied the impact of partisan elite endorsements within a partisan primary. The study found that while endorsed candidates do benefit from such endorsements, opponents of the endorsed candidate experience a drop in voter affect, even if the opponent is not specifically named in the endorsement message.

This persuasive power of endorsements becomes even more important when viewed from a practical perspective. Historically, political elites endorsing candidates have typically followed an unwritten rule and avoided such endorsements within a contested partisan primary election. Recent elections, however, indicate that this unwritten rule is being violated more frequently (Zanona and Caygle, 2020). Donald Trump has consistently offered endorsements within Republican primary elections, sometimes even endorsing challengers to incumbents running for reelection (Carlsen and Grullon Paz, 2018). The trend of such intraparty endorsements, however, is not exclusive to the Republican Party: In 2020, Democratic Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez endorsed Ed Markey in his campaign to be re-elected to the U.S. Senate from Massachusetts, while House Speaker Nancy Pelosi offered a competing endorsement of Rep. Joseph Kennedy (Balz, 2019). In the early stages of the 2020 congressional elections, Democratic members of the U.S. Congress have already offered competing endorsements of two of their cohorts—Representatives Sean Casten and Marie Newman of Illinois—who are now in the same congressional district thanks to recent redistricting resulting from 2021 reapportionment efforts (LaTour, 2021).

The extant literature not only shows the impact that an endorsement can have on voters’ attitudes; it also highlights the impact that the content of the endorsement can have as well [see Bullock (2011); Nicholson (2011)]. However, while the content of the endorsement has been shown to influence voters’ perceptions, the literature has generally not examined the tone of these endorsements to see if tone—separate from content—helps explain the persuasive power of such endorsements.

One example of tone in political persuasion that has been frequently examined is the issue of negative advertising within the context of political campaigns. Negative advertising, or attack advertising, refers to one-sided targeted advertising that highlights a candidate’s flaws, poor track record, and broken promises (Merritt, 1984; Johnson-Cartee and Copeland, 1989; Pinkleton et al., 2002).

Early studies of negative advertising suggested that negative advertising has an undesirable effect on civic participation as the voters would become dissatisfied and limit their involvement in the political participation process (Ansolabehere and Iyengar, 1997; Pinkleton et al., 2002). These studies, however, also found that attack ads inversely affect the evaluation of the targeted politician and voting intention for the targeted candidate to a significantly greater extent than the evaluation of, and voting intention for, the sponsoring candidate among the members of the candidate’s political party as well as the sponsor’s political party (Kaid and Boydston, 1987; Johnson-Cartee and Copeland, 1989, 1991; Pinkleton, 1998).

More recent studies, on the other hand, have found support for a competing hypothesis that negative advertisement increases civic engagement and political participation, albeit on a conditional basis (Goldstein and Freedman, 2002; Brooks, 2006; Hopp and Vargo, 2017; Ma et al., 2019). Goldstein and Freedman (2002) argue that “Negative charges imply that one’s vote choice—and one’s vote—matters and that citizens should care about the outcome of a race” (p. 723). Attack advertising also provides a significant amount of information relevant to the voting decision, and “because such negative information may be given greater weight in political judgments than positive messages,” it can result in greater turnout.

A meta-analysis of negative advertising studies found that studies tying negative ads to a large decline in the evaluation of the targeted candidate typically have a smaller sample size than studies finding a small or negative decline in the evaluation of the target candidate (Lau et al., 2007). Regarding the backlash for the sponsoring candidate, the analysis found evidence that the affect for the attackers declines at a more considerable pace—even when adjusted for sampling error. Lau et al. (2007), however, note that because the results for targets and attackers are not paired from the same studies, they “do not directly gauge the net effect of going negative on affect for attackers” (p. 1183).

Overall, there is scientific evidence that negative advertising does have an effect, but there is no consensus on whether it has the intended effect on voting behavior, the evaluations of the sponsor, and the target. This lack of consensus highlights the need to further evaluate the effect of negative ads in more contexts. As an example, when an attack ad comes from a political elite other than the candidate, what is the effect on the evaluation of the sponsor, the sponsored, and the target? The present experiment seeks to examine whether such endorsements have the intended effect for the endorsee and whether they have any effect on the endorser and the unendorsed.

3 Theoretical foundation

The belief-based models of attitude are premised on the notion that attitudes toward an object are based on the strength of salient beliefs that one holds about that object and the evaluations of those beliefs (Fishbein, 1967; Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975; Ajzen and Fishbein, 1977; O’Keefe, 2002).

The effect of persuasive messages (such as political ads or endorsements) depends on how the receiver of the message perceives the persuasive messages. Under a social judgment theoretic approach, the receivers’ preexisting attitudes (or beliefs) toward the propositions made in the persuasive messages prompt them to evaluate each proposition relative to a range of possible alternatives and form an attitude of acceptance, noncommitment, or rejection (Sherif et al., 1965; Granberg, 1982; Atkin and Smith, 2008).

Sherif et al. (1965) argue that the receivers of persuasive messages judge the range of alternatives individually, but that these judgments can be combined to paint a picture of the prevailing patterns of attitudes among particular groups of people. They also argue that members of these groups take cues from the social norms and adopt “practices, customs, traditions, and definitions” that they will then use to evaluate the propositions presented in persuasive messages.

In social judgment theory, the latitude of acceptance refers to the positions that the receiver finds acceptable; the latitude of noncommitment refers to the positions that the receiver finds neither acceptable nor unacceptable; and the latitude of rejection refers to the positions that the receiver of the persuasive message finds unacceptable. The salient belief that the receiver of the persuasive message holds among the possible alternatives is referred to as the anchor point (Atkin and Smith, 2008).

The Social Judgment Theory is audience-focused, in that the theory helps to explain the effectiveness of a persuasive appeal by examining how an audience processes such appeals. More recently, researchers have begun to look at the message itself as a separate variable that impacts the effectiveness of persuasive messages. Indeed, Appelman and Sundar (2016) have noted that less attention is typically given to examining the message itself (vs. the source or the audience) when developing a theoretical perspective of the communication process. These authors have argued that a scale measuring the credibility of a message “would have significant use for multiple fields” (p. 60). The researchers developed a Multiple Indicators and Multiple Causes (MIMIC) model to measure message credibility specifically when studying news stories. The MIMIC model specifically identified concepts of accuracy, authenticity, and believability as components of message credibility. The researchers noted that the scale, with some modification, could be used in persuasion-oriented applications such as strategic communications.

McCracken’s Meaning Transfer Model recognized the importance of the message and its meaning, specifically within a persuasive context (McCracken, 1986). Initially developed to explain the persuasive process of advertising on consumer attitudes and behavior, the MTM has been applied to other persuasive situations including celebrity endorsements of consumer brands (Miller and Allen, 2012), celebrity endorsements of political issues (Jackson and Darrow, 2005), and political elite endorsements of candidates (Vizcarrondo, 2021).

McCracken uses advertising as an example of the meaning transfer process, beginning with the persuader deciding the “cultural meanings” intended as the focus of the persuasive message. To determine these cultural meanings, the persuader must identify “objects, persons, and context” already familiar to an audience and use these elements as components of the predetermined cultural meaning (McCracken, 1989, p. 314). According to McCracken, these components allow the communicator to present the cultural meaning “in visible, concrete form” (p. 314). This “concrete form” is the message created by the persuader. A successfully created message allows for a transfer of cultural meaning from the elements (i.e., objects, persons, and context) to the focus of the persuasive message (e.g., consumer product or political candidate). Ultimately, the receiving audience (e.g., consumers, voters, etc.) “must take possession of the meanings and (construct) their notions of the self and the world” (p. 314). While both the persuader and the audience are participants in this process, the Meaning Transfer Model’s focus on combining elements into a “concrete form” highlights the importance of the message itself and in doing so, makes a compelling argument for examining messaging (and hence, message credibility) as a separate theoretical concept.

4 Empirical expectations and hypotheses

Beyond the impact that tone (e.g., positive vs. negative messaging) in political advertising can have on voters’ attitudes and behaviors, is it possible that the tone can also be an influencing variable in the persuasiveness of political endorsements? This proposed study seeks to identify and measure such influences, specifically within the context of a competitive intra-party contest.

First, the study will examine if and how the tone of endorsement statements impacts the candidates in the targeted partisan primary:

H1: Endorsements, by a party elite featuring a positive tone will benefit the endorsed candidate as reflected by higher evaluations of the candidate.

H2: Endorsements by a party elite featuring a negative tone will negatively impact the unendorsed candidate as reflected by lower evaluations of that candidate.

Because intra-party endorsements have typically been viewed as potentially damaging to the cohesiveness and unity of a political party, such endorsements may also impact voters’ assessment of the political party as well as the partisan elite offering the endorsement. In terms of the Social Judgment Theory, depending on the ego-involvement of the endorsed or unendorsed candidate, voters may find it more within their latitude of acceptance to change their attitude toward the endorser and the party, should they find the endorsement itself in their latitude of rejection. Therefore, this study further hypothesizes:

H3: Partisan elites offering an endorsement within a partisan primary will experience a more favorable change in their evaluations among voters who see a positive-tone endorsement than among voters who see a negative-tone endorsement.

H4: Endorsements made by partisan elites within a partisan primary will lead to lower evaluations of the political party among those self-identifying with that party.

5 Scope of study

For this study, it is important to note the differences between political endorsements and political advertisements. Both are important and influential examples of political communication; however, there are key differences between the two that justify the need to examine each as separate forms of political communication, with different effects on a targeted voting audience.

One difference between advertisements and endorsements acknowledges a different “spokesperson” delivering these messages. A large portion of political advertisements—when used within the context of electing specific candidates—are messages from the candidate himself to a broad or specific segment of the potential voting population. To be sure, some political advertisements may be messages from non-candidates such as political action committees. However, both types of political advertisements can often appear to the average voter as if it is a message directly from the actual candidate. As such, viewers of political advertisements usually evaluate such messages by considering the credibility of the candidate, as he or she is considered to be the messenger of the advertising communication. On the other hand, political endorsements are, by design, statements from a third party indicating their support of a particular candidate. A voter’s evaluative process of a political endorsement, therefore, will likely consider the credibility of the endorser as the messenger of the communication, rather than considering the credibility of the candidate when evaluating a political advertisement.

A second difference between political advertisements and political endorsements focuses on how these persuasive messages may be communicated to the general public. While endorsements may be incorporated in a political advertisement sponsored by the candidate, they may also be presented to the general public as a newsworthy story. In such a case, an endorsement may once again be evaluated as more credible than a political advertisement. In this case, however, this credibility advantage may be attributed to the way in which is presented rather than to the person delivering the endorsement message.

These two characteristics illustrate the different persuasive processes an audience may use when analyzing a political endorsement instead of a political advertisement. At a minimum, these differences highlight the importance of examining these two types of political communications separately to better understand the persuasive impact of each. As shown in the literature review, much has been written about the tone of political advertisements (e.g., negative vs. positive), but far less attention has focused on the impact of the tone of political endorsements. This study specifically focuses on the persuasive process and effectiveness of political endorsements within the context of a specific political campaign.

6 Method

6.1 Selection of targeted election

As with most midterm elections, the election of 2022 was seen by many as a referendum on the sitting president (Jacobson, 2019). However, the continued investigations related to the January 6, 2021, protests on Capitol Hill also kept former President Trump prominently in the news and the midterm election debates. As such, both President Biden and President Trump had the potential to motivate voters in both parties. While most predicted a return of the U.S. House of Representatives to Republicans, control of the U.S. Senate became less certain throughout the 2022 campaign (Jacobson, 2022).

With the Senate in a 50/50 deadlock for most of the 117th session of Congress leading up to the midterms, each party prioritized several key states to break that deadlock. One of these key states was Missouri, where incumbent Roy Blunt had announced he would not seek reelection, thereby creating an open seat (Gabriel, 2021). While Missouri had long been viewed as a toss-up or bellwether state for presidential elections, results beginning with the 2012 election showed a trend towards decisive victories for Republican party nominees Mitt Romney in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020 (Ballotpedia, 2023a). Despite this trend toward the Republican Party in presidential elections, Missourians had continued to show an independent streak during U.S. Senate elections: Since 2006, three of the five U.S. Senate general elections in Missouri had been decided by less than six percentage points, or an average of 3.6% across those elections (Ballotpedia, 2023b). Moreover, two of these three close elections featured an incumbent senator, clearly showing that the power of incumbency could not be a forgone conclusion with such independent-minded voters as those in Missouri. Before the general election, both the Democratic and Republican parties held primary contests that proved to be competitive for different reasons.

Among Republicans, several well-established candidates with previous election successes were running for the statewide office, including two sitting Congresspersons and two candidates who had each won previous statewide elections. The primary gained increased attention when former Gov. Eric Greitens announced he was a candidate (Friess, 2022). Greitens was expected to be a formidable candidate, with a solid base of loyal supporters who identified with an anti-establishment political philosophy as advocated by former President Trump (Gabriel, 2021). However, when personal scandals led to his resignation as Missouri’s governor, Greitens’ popularity among mainstream Republicans dropped significantly. Greitens was seen as potentially unable to garner a majority of Republican primary voters, but in an expected multi-candidate primary, he could have enough support to win the primary without a majority of Republican voters. A total of 21 Republicans were listed on the Republican primary ballot, ensuring a competitive election in which the outcome could be influenced by different variables, including endorsements (State of Missouri, 2022).

The Democratic Party had a competitive primary as well, albeit for different reasons. First, the two leading candidates were relatively unknown to statewide voters. One candidate—Lucas Kunce—had unsuccessfully run for office before, but the election was a local, state representative election (Kite, 2022). As such, Missouri voters outside of that senate district were unfamiliar with Kunce. His opponent—Trudy Busch Valentine—had never run for elective office before. While not well-known politically, she did benefit from wide name recognition as the daughter of the late “Gussie” Busch, longtime chairman of St. Louis-headquartered Anheuser Busch brewery and owner of the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team (History of the Busch family, 2008). Second, the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson, which effectively overturned Roe v. Wade, was announced 5 weeks prior to the primary election (Friess, 2022). As such, many Democrats fearing the nationwide loss of abortion rights became even more motivated to participate in the upcoming mid-terms which, for Missourians, would begin with the party primaries a mere 29 days after the Dobbs decision was announced.

Given the recent history of close elections in Missouri U.S. Senate elections, the independent voting history of Missouri voters, and the unique characteristics leading to competitive primaries for both parties, the midterm primaries for Missouri’s U.S. Senate election proved to be a meaningful venue to use as the focus of this study.

6.2 Participants and design

A 2×2 experimental design was used with two endorsers (i.e., Democrat and Republican) and two mock endorsements (i.e., positive and negative) by each endorser. As discussed earlier, there is a rich literature in support of the notion that people often do not seek out political information themselves, preferring instead to use shortcuts such as endorser messages (Boudreau, 2020). Moreover, endorsements can significantly influence voter attitudes whether they come in the form of rational political advice (Calvert, 1985), interest group endorsements of policies (McKelvey and Ordeshook, 1985), or whether they present positive or negative cues (Grofman and Norrander, 1990). These findings support the idea that voters will use information from endorsements as “if they had better, or complete, information” (Lupia, 1992, p. 397) when casting their vote. As such, the inclusion of a control group in this experimental design to establish the presence of an effect attributed to endorsements is unnecessary.

Participants for the online experiment were recruited through Dynata, a third-party, global market research firm offering services including survey panel recruiting and data collection. Using a third party to recruit participants enabled the efficient administration of an online experiment involving registered voters in Missouri.

The experimental survey was administered from June 30, 2022, to July 5, 2022, approximately 1 month before Missouri’s primary elections. Thus, the timing was close enough to the election that most voters were somewhat familiar with the election. This contributed to a wider distribution among voters with respect to their leanings toward a particular candidate, the strength of these leanings, and voters’ likelihood to vote in the upcoming election. On the other hand, the timing was not so late in the campaign that any “endorser” used in the stimulus had announced a public endorsement of one of the candidates. Overall, 906 registered voters participated in the experiment, but after removing incomplete responses and participants who failed the instructional manipulation check, the sample was reduced to 776.

6.3 Procedure

Participants in the online experiment completed a pretest questionnaire designed to capture general information including demographics, partisanship, and political information efficacy. In addition, the survey included questions designed to measure traits such as voter enthusiasm and evaluations of the major candidates in the primary election. Participants were asked which party they more closely aligned with; those who did not self-identify as a Republican or Democrat—to some degree—were not included in the study. Based on their party identification, participants were randomly assigned to view one of two sets of stimuli specifically designed for that party.

6.4 Independent variables

For Democrats, the first set featured two mock articles announcing an endorsement from former Sen. Claire McCaskill of Trudy Busch Valentine. The tone of the statement was positive and focused on the complementary characteristics of Valentine. Among these characteristics were statements that Valentine “will fight for all of our state’s citizens” and is “committed to fighting for the rights of women and all Missourians.” The first article was presented as an online article from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the largest newspaper by circulation in Missouri (AgilityPR, 2022). The second article seen by this group was also positive but was a shorter, online “Breaking News” story that appeared to be posted on the website of The Kansas City Star, Missouri’s second-largest newspaper as measured by circulation. The stimuli presented to the second group of Democratic participants again featured similarly created news stories reporting on Sen. McCaskill’s endorsement of Valentine. In this case, however, the tone was more negative, and prominently featured criticisms of Valentine’s opponent, Lucas Kunce. Kunce’s shift in his abortion stance was used as a way to distinguish the two candidates in McCaskill’s “endorsement announcement.” The message described Kunce as someone who “has ‘evolved’ on one of the most basic freedoms that women now are in danger of losing.”

Republican participants also saw news stories from the same newspapers announcing outgoing Sen. Roy Blunt’s endorsement of Missouri’s attorney general, Eric Schmitt. Again, the first group saw two news stories announcing a Blunt endorsement statement that was positive in tone and featured positive characteristics of Schmitt. The statement noted that Schmitt’s “record of public service is one of fighting for lower taxes and defending our Second Amendment rights.” The second group of Republican participants saw news stories featuring a Blunt endorsement statement that focused on criticisms of Gov. Eric Greitens’ ethical issues that had been a prominent issue during the campaign. The endorsement statement noted Greitens’ “track record of unethical behavior does not reflect the values of Missouri Republicans.” These different stimuli were the independent (manipulated) variables for the experiment.

After viewing the stimulus, participants completed the experiment by answering additional follow-up questions. Questions in this posttest include some of the questions asked in the pretest, particularly those questions designed to measure participants’ attitudes towards candidates, endorsers, and the upcoming primary election.

6.5 Dependent variables

To answer the research questions, changes in participants’ evaluations—as expressed in the pretest and posttest—were measured.

6.5.1 Endorsee/non-endorsee evaluation

Participants were asked to evaluate the candidates featured in this study, using a scale of zero (unfavorable evaluation) to 100 (favorable evaluation). This allowed for measuring the change in a participant’s evaluation of both the endorsed candidate as well as their opponent (i.e., unendorsed candidate), depending on whether the endorsement tone was positive or negative.

6.5.2 Endorser evaluation

Participants were also asked to evaluate the partisan elite used as the endorser in this study, also using a scale of zero (unfavorable evaluation) to 100 (favorable evaluation). As such, any changes between the pretest and posttest evaluation were captured and analyzed to see if these changes were significantly different between those who saw the positive endorsement statement and those exposed to the negative endorsement statement.

6.5.3 Party affiliation

Participants were asked to evaluate their party leanings using a five-point Likert scale. Democratic participants chose from five options, with “leaning Democrat” and “solid Democrat” at each end of the scale, and “Democrat” in the middle of the scale. Republican participants were given a similar scale using their party. Comparing the pretest and posttest evaluations helped to determine the impact that the tone of the endorsement statement had on the favorability ratings of each party among self-identified members of that party.

7 Results

7.1 Impact of endorsement’s tone on the endorsed and unendorsed candidates

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine whether endorsements have any effect on evaluations of the candidates, endorsers, and political parties. A significant main effect of endorsement emerged in the analysis F(7, 776) = 6.438, p < 0.001; Wilk’s lambda = 0.750, suggesting that endorsement does have an effect on candidate evaluation, party evaluation, and endorser evaluation. Among the four candidates, the presence of an endorsement had an effect on party voters’ evaluations of Kunce (F(3, 773) = 7.190; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.027); Schmitt (F(3, 773) = 14.519; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.053); and Valentine (F(3, 773) = 42.207; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.141), but not Greitens (F(3, 773) = 0.974; p = 0.405; R2 = 0.004). The presence of an endorsement also had an effect on party voters’ evaluations of both endorsers: Blunt (F(3, 773) = 5.940; p < 0.001; R2 = 0.023) and McCaskill (F(3, 773) = 6.561; p < 0.001; R2 =0.025) and voters’ evaluations of the Republican party (F(3, 773) = 4.286; p < 0.01; R2 = 0.016), but not the Democratic party (F(3, 773) = 0.666; p = 0.573; R2 = 0.003). Table 1 displays the results of the between-subjects analysis.

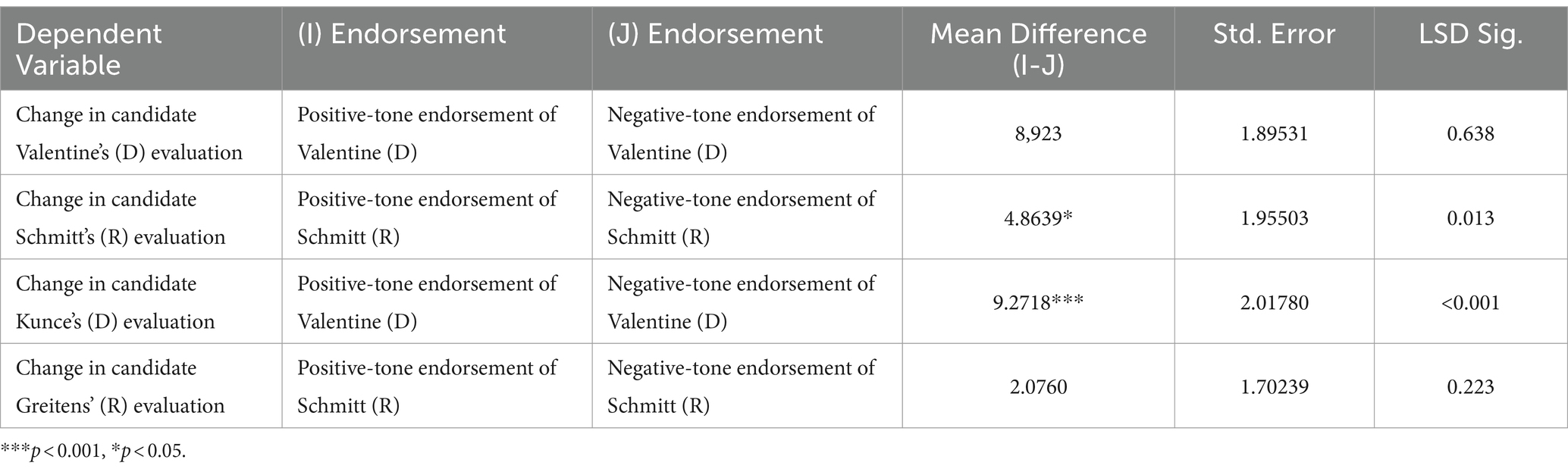

Further post hoc analyses were conducted to compare the effectiveness of positive and negative endorsements on the candidate, endorser, and party evaluations. In most cases, the results confirm a statistically significant effect on each candidate that is consistent with the predicted effect. For candidates receiving an endorsement, voters who viewed an endorsement incorporating a positive message recorded higher evaluations of the endorsee than of those viewing a negative message that was directed at the candidate’s opponent. As demonstrated in Table 2, for Valentine, this difference was marginal (i.e., a mean difference of 0.893) and not statistically significant but still in the predicted direction. Therefore, H1 is partially supported.

Voters presented with an endorsement incorporating a negative-tone message against the opponent lowered their evaluation of the unendorsed candidate. The negative-tone endorsement by McCaskill dropped Kunce’s evaluation by nine points. While Greitens’ evaluation also dropped by two points, the change was not statistically significant. Therefore, H2 is also partially supported.

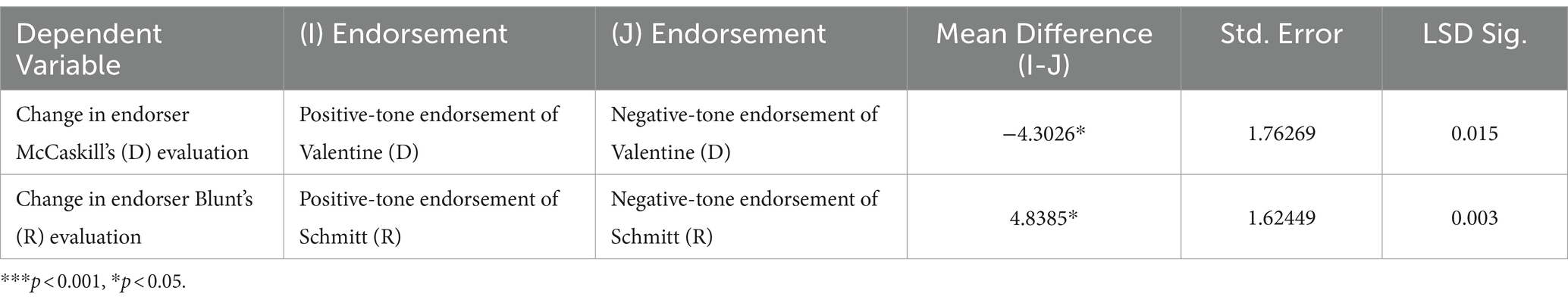

7.2 Impact of endorsement on endorser and partisanship

When examining the impact of endorsement tone on how voters evaluate the endorser, the results were statistically significant for both endorsers, but the effect was not always in the predicted direction (Table 3). As predicted, Republicans saw Blunt’s positive-tone endorsement of Schmitt responded with an increase (i.e., more positive) change in Blunt’s evaluation than those who were exposed to the negative-tone endorsement in a statistically significant manner. Among Democrats, however, those who viewed McCaskill’s positive-tone endorsement reported a change in McCaskill’s evaluation that was lower than those who viewed her negative-tone endorsement. This effect was statistically significant but in the opposite of the predicted direction. Therefore, H3 is partially supported.

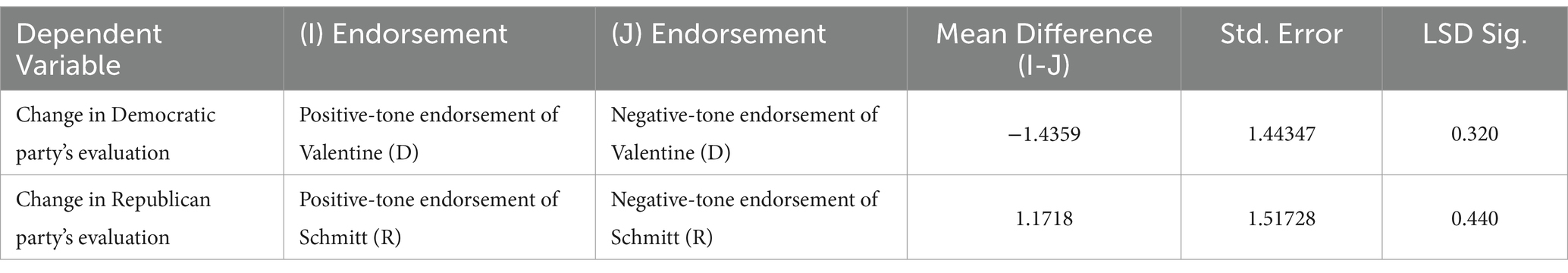

Finally, there were no statistically significant results to determine any effect of endorsement tone on voters’ evaluations of their respective political party (Table 4). Accordingly, H4 is not supported.

To explore results further, post hoc interaction analyses were conducted to determine whether the effect of endorsement is moderated by the voters’ political knowledge and their initial enthusiasm toward the government, politics the candidates, and endorsers.

Political enthusiasm1 moderated the effect of endorsement on the evaluation of Valentine F(1, 709) = 7.817, p < 0.01; McCaskill F(1, 709) = 5.841, p <0.05; and Greitens F(1, 711) = 9.003, p < 0.01. In the case of Valentine and McCaskill, higher levels of political enthusiasm resulted in an improved evaluation of the candidates and in the case of Greitens, higher political enthusiasm reinforces the adverse effect of Blunt’s endorsement of Schmitt on voter evaluation of Greitens.

Political knowledge2 did not have any interaction with the effect of endorsements on candidate evaluations. Of the participants in the study, 34% (n = 312) answered all questions designed to measure political knowledge correctly, and almost 53% (n = 479) addressed at least one question correctly.

Initial enthusiasm toward candidates and endorsers by far had the most interaction with the effect of endorsements. Enthusiasm for Greitens moderated the effect of endorsements on Valentine F(1, 709) = 8.937, p < 0.01; Kunce F(1, 709) = 8.785, p < 0.01; and Schmitt F(1, 711) = 8.224, p < 0.01. Enthusiasm for McCaskill moderated the effect of endorsements on Valentine F(1, 709) = 31.268, p < 0.001; the Democratic Party F(1, 709) = 5.264, p <0.05; and the Republican Party F(1, 711) = 3.927, p < 0.05. Enthusiasm for Schmitt only moderated the effect of endorsement on Greitens F(1, 711) = 10.883, p < 0.01 and Enthusiasm for Valentine only moderated the effect of endorsement on Kunce F(1, 709) = 19.417, p < 0.001.

Enthusiasm for political parties also interacted with endorsements. Enthusiasm for the Democratic party moderated the effect of endorsements on Valentine F(1, 709) = 30.944, p < 0.001; Kunce F(1, 709) = 4.957, p < 0.05; McCaskill F(1, 709) = 63.983, p < 0.001; and Greitens F(1, 711) = 6.147, p < 0.05. Finally, Enthusiasm for the Republican party moderated the effect of endorsements on Blunt F(1, 711) = 28.536, p < 0.001; Greitens F(1, 7,011) = 8.172, p < 0.01; Schmitt F(1, 7,011) = 25.624, p < 0.001, and Kunce F(1, 709) = 8.201, p < 0.01.

8 Discussion

The results of the MANOVAs generally support the idea that the tone of a political endorsement can and does have its intended effect on the evaluation of the targeted candidate. For positive-tone endorsements targeting the endorsed candidates, potential voters respond with an increased favorable evaluation of that candidate. Conversely, potential voters—when exposed to a negative-tone endorsement that targets the unendorsed candidate—respond with a greater negative evaluation of that candidate. One of the strengths of this study is that two different primaries were studied, and the characteristics of each primary varied in terms of the type of candidates included in the experiment. This provides an opportunity to examine different variables that may impact the effectiveness of positive and negative endorsements.

Positive-tone endorsements benefitted both endorsed candidates but only the Republican candidate benefitted in a statistically significant manner. Negative endorsements hurt both unendorsed candidates, but only the damage to the Democratic unendorsed candidate was statistically significant. Many of the respondents rated some of the candidates at the highest (i.e., 100) or lowest (i.e., 0) level possible both in the pre-test and the post-test. This implies that these individuals had already made up their minds and would not be swayed either way by the endorsement. To control for this, these individuals were removed from the sample; the resulting revised MANOVA model (See Supplementary Material), was statistically significant, but could only explain the change in Trudy Busch Valentine’s evaluation at a statistically significant level, not Eric Greitens’. Further, it is worth noting that in this model, no main effect of endorsement on the Republican Party evaluations emerged—an effect that was observed in the main model reported in the results section.

In the main model, among Republicans, the endorsed candidate—Eric Schmitt—benefitted from a higher evaluation among those who saw the positive-tone endorsement, and this change in the evaluation was statistically significant. However, while the unendorsed candidate—Eric Greitens—experienced a predicted decline in his evaluation among participants who saw the negative-tone endorsement, this change was not statistically significant. To understand this anomaly, two characteristics of the Republican primary may provide some explanation. First, the Republican candidates examined in this study were political veterans who were likely more recognizable names and personalities. Both candidates had previously run—and won—statewide elections. On the other hand, the candidates studied in the Democratic primary were not as well-known throughout the state. Only one Democratic candidate—Lucas Kunce—had previously run for political office, and that was a local election for the Missouri state legislature (i.e., not a statewide election). Indeed, previous research has suggested (but not confirmed) that “endorsements of lesser-known candidates may have a greater impact on those candidates’ evaluations than better-known and more established candidates” (Vizcarrondo, 2021, p. 11). Second, as a candidate, Eric Greitens was both controversial and polarizing. In reporting his entry in the primary, Gabriel (2021) referred to the candidate as a “scandal-haunted former Missouri governor” whose “candidacy set off a four-alarm fire with state party leaders” (para. 5). However, Gabriel also noted that Greitens “remains popular with a core of Republican voters” and “has both grass-roots supporters and high-profile enemies in the Missouri G.O.P.” (para. 9). As such, Greitens likely had an unusually large number of voters with strong, entrenched opinions of him, which would be less likely to change as the result of a political endorsement, regardless of the tone.

From a Social Judgment Theory perspective, the findings suggest that for Republican voters Schmitt, who was a relatively known figure in the state, had more ego involvement and when he was positively endorsed, the endorsement fell squarely in the voters’ latitude of acceptance. As a result, the voters responded by evaluating the endorsed candidate highly. Conversely, Valentine, who had never run for public office in the state, had a smaller ego involvement and was not central to the Democratic voters’ self-identity, which can explain why Democratic voters were more likely to find the negative endorsement more in their latitude of acceptance and lower their evaluation of Valentine’s opponent.

Beyond the impact of endorsements on the political candidates, this study also offers strong evidence of an effect on the endorser, not just the endorsee. Both the Republican and Democratic endorsers experienced a more favorable change in their evaluations among voters who saw the positive-tone endorsement over those voters who saw the negative-tone endorsement. Such findings point to the potential risks and rewards for a political elite considering endorsing a candidate within an intra-party contest. In particular, a negative-tone endorsement may succeed in lowering voters’ assessments of the unendorsed candidate, but this “success” may come at the expense of the reputation of the endorser himself. Given the differences previously described between the characteristics of the two primaries studied, this potential backlash effect on the endorser appears to be a possibility, regardless of whether the primary election or a particular candidate is controversial or polarizing.

While there may be a backlash effect felt by the elite endorser, this study did not provide any support for the idea that the tone of an intra-party endorsement impacts voters’ attitudes towards their respective political parties. These findings can be explained by the Social Judgment Theory: It appears that the political candidates and partisanships both have varying degrees of ego involvement and play central roles in voters’ self-identity. This results in the voters evaluating the message of the endorser. If the message has a negative tone toward a candidate who is important to the voters’ self-identity, the message is placed in the latitude of rejection. Since the message is rejected, the messenger—i.e., the endorser—is also rejected and evaluated lower than before.

As more political elites offer endorsements during a partisan primary, party leaders have expressed concern that this trend could divide a party and weaken its chance for victory in the general election. This study does not provide support for this concern, but one key characteristic should be noted: This experimental study was conducted during the primary campaign and before the actual election. As a result, it is possible that a supporter of the unendorsed candidate may have a negative impression of the endorser, but still maintain a positive view of his or her party while the primary campaign is still underway. However, it cannot be concluded that after the election, supporters of a defeated candidate would still view the political party in positive terms. It could be hypothesized that such supporters grow disillusioned with the political party, in part because of the endorsements from established elites within the party during the primary election.

Although not every interaction was statistically significant, the study found that initial enthusiasm for party, candidates, and endorsers moderates the effect of endorsements. Enthusiasm for the party moderated the effect of endorsement on eight out of ten occasions. Enthusiasm for the candidates moderated the effect on five occasions and enthusiasm for the endorsers moderated the effect on three occasions. The study also found that general enthusiasm for government and politics tends to reinforce the effects of endorsements. In fact, the strongest interaction was observed in relation to the effect of Schmitt’s endorsement on Greitens, who was anti-establishment and the most polarizing figure among the politicians in this study. These findings can be explained by Social Judgment theory, as the initial enthusiasm for politics and political entities represents the preexisting attitudes and the endorsements represent the alternatives presented to the participants. The closer these preexisting beliefs are to the alternatives presented, the stronger the effect of endorsement (Paek et al., 2005; Wei and Lo, 2007; Reid, 2012).

The absence of any interaction with political knowledge can be explained by the absence of any meaningful variation in the political knowledge of the participants and by the findings of earlier studies suggesting that voters are not motivated enough to amass political knowledge and use endorsements as informational shortcuts (Calvert, 1985; Lupia, 1992; Boudreau, 2020).

While this study did look at similar primary elections for both major political parties, one limitation to the study may be that these primaries were in the same state. As such, it may be argued that the political landscape and/or voting behavior in different states might have led to different results from a similar experiment. Indeed, this study has acknowledged some unique characteristics to certain candidates and internal party dynamics; broadening such a study to incorporate multiple elections during the same primary season may yield additional insights that could strengthen the understanding of how intra-party endorsements impact primary elections.

In addition, since the endorsements used in this study were not real endorsements, it is possible that voters—particularly highly knowledgeable voters—may not have felt as much of an impact from the “endorsements” as if the endorsements had been real. On the other hand, any effect may have been minimized by the fact that the two endorsers in this study had not publicly endorsed any candidate at the time of the experiment. As such, even highly knowledgeable voters could have concluded that the stimuli used in this study were “real time” updates to the election season.

9 Conclusion

Building upon a basic concept of the Meaning Transfer Model, this study reaffirms the importance of the message itself when examining persuasion communication and validates Appelman and Sundar (2016) call to consider the message as a separate element when considering credibility (ethos) as a component of persuasive power. In this case, this study goes beyond traditional advertisements to show that the tone of political endorsements can also have effects on voters’ attitudes. It is important to note, however, that the impact the tone of an endorsement may have can vary and can be influenced by additional variables. Ego involvement of the endorsed and unendorsed candidates—or the degree to which the candidates play a role in the voter’s self-identity, impacts the placement of the endorsement in the voters’ judgment category. For example, the findings show that for well-known candidates (like Schmitt, presumably with a higher ego involvement) a positive endorsement is placed in the latitude of acceptance. On the other hand, lesser-known candidates (like Valentine, presumably with a lower ego involvement) may benefit from a negative endorsement in the form of reduced evaluation of their opponents by the voters as they find it more within their latitude of acceptance to avoid the opponent than to gravitate toward the endorsed candidate.

The inconclusive results related to an endorsement’s influence on voters’ attitudes towards Eric Greitens, for example, provide evidence that such endorsements will not always lead to a measurable or conclusive level of influence. However, this finding is consistent with the wealth of previous research related to positive versus negative political advertising: Both can impact voters’ attitudes, but in different ways and for different reasons.

The study also shows that the tone of a political endorsement can affect more than just voters’ perceptions of the candidates. Such endorsements also influence voters’ attitudes toward the endorsers, but the impact can vary. As such, political elites considering endorsing a candidate – particularly within a partisan primary—would be advised to consider the impact such actions may have on the endorser, not just the candidates. The study also provides some hints to political strategists when considering using endorsements within a primary election; this study supports the idea that lesser-known candidates tend to see a greater benefit from intra-party endorsements, so the risk–reward calculus can vary from one candidate to another.

While political partisans often express concerns that endorsements within a party’s primary may exacerbate divisions and dissension within the party, this study did not provide evidence of such an impact from intra-party endorsements. However, future studies that control for additional variables may lead to different conclusions. For example, this study was an experimental study that took place before the primary elections, so participants would not have known whether or not their preferred candidate had won the primary election. Would a voter—upset over his candidate losing the primary—be more apt to express dissatisfaction with his party in that case? Additionally, if the party’s nominee subsequently lost the general election, would partisan voters begin to view their party more negatively? Future studies exploring this possibility should be considered to expand the knowledge of the effect of such endorsements within a primary election. Similarly, voters’ attitudes towards their respective parties may not be influenced by an endorsement tone—where the voter attitude is the dependent variable—but future studies may consider “party loyalty” or “party affinity” as a moderating factor along with other potential variables combining with the impact of endorsement tone.

This study did not examine if and how the tone of political endorsements may impact voters’ attitudes toward the general political process. Existing literature supports the idea that endorsements can affect voters’ attitudes towards the general political process, and that advertising tone (e.g., positive vs. negative) can impact such attitudes as well. It is understandable, therefore, to ask if endorsement tone—like advertising tone—may also impact voters’ faith in the electoral process. Moreover, negative changes in voters’ attitudes towards the electoral process could lead to less enthusiasm for the specific election at hand. As such, any direct benefit a candidate sees from an endorsement may be lost if voters also lose faith in the electoral process and decide not to vote. A candidate’s increased favorability is meaningless if the potential voter is still not motivated enough to actually vote in that particular election. Future studies may examine the effect of intra-party endorsements on voters’ attitudes and enthusiasm toward a specific election. While political endorsements have long been used in the political process, the tendency for such endorsements to occur within party primaries seems to be more common and more accepted. However, such endorsements may affect more than just the targeted candidate. As this aspect of political persuasion continues to increase, the importance of understanding the impact on candidates, voters, and the overall political process will increase as well.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Kennesaw State University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TV: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. TV was supported by a 2022 Kennesaw State University, Norman J. Radow College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Scholarship Support Grant.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Media Southeast Colloquium 2022 and the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Media 2023. We thank the conference discussants and fellow presenters for their helpful suggestions on making this manuscript better. We would also like to acknowledge Kennesaw State University’s High-Performance Computing (HPC) cluster that made analyzing our data possible (Research Computing, Kennesaw State University, 2023).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1363974/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Political enthusiasm was measured through the level of agreement with a battery of items such as, “I trust the government to do what is right;” “The government is pretty much run for the benefit of all the people,” “Most people running the government are honest,” etc.

2. ^Political knowledge was measured by asking “Which party currently has a majority of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives?” “What job or political office is currently held by John Roberts?” and “Which of the following currently serves as a U.S. Senator from Missouri?”

References

Aaker, J., and Chang, V. (2009) Obama and the power of social media technology. Available at: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/case-studies/

AgilityPR. (2022), Top 10 Missouri daily newspapers by circulation. Agility PR Solutions. Available at: https://www.agilitypr.com/resources/top-media-outlets/top-10-Missouri-daily-newspapers-by-circulation/

Ajzen, I., and Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 84, 888–918. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

Ansolabehere, S., and Iyengar, S. (1997). Going negative: how political advertisements shrink and polarize the electorate. New York: Free Press.

Appelman, A., and Sundar, S. S. (2016). Measuring message credibility: construction and validation of an exclusive scale. J. Mass Commun. Q. 93, 59–79. doi: 10.1177/1077699015606057

Atkin, C. K., and Smith, S. W. (2008). “Social judgment theory” in The international encyclopedia of communication. ed. W. Donsbach (New York: John Wiley and Sons).

Ballotpedia. (2023a). Presidential voting trends in Missouri. Available at: https://ballotpedia.org/Presidential_voting_trends_in_Missouri

Ballotpedia. (2023b). United States Senate Election in Missouri. Available at: https://ballotpedia.org/United_States_Senate_election_in_Missouri,_2018

Balz, D. (2019). Yes, the republican party has changed since 2016. You think the democratic party hasn’t? Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/yes-the-republican-party-has-changed-since-2016-you-think-the-democratic-party-I/2019/03/09/b3a8f376-41da-11e9-9361-301ffb5bd5e6_story.html.

Boudreau, C. (2020). “The persuasion effects of political endorsements” in The Oxford handbook of electoral persuasion. eds. E. Suhay, B. Grofman, and A. H. Trechsel (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 224–243.

Brooks, D. J. (2006). The resilient voter: moving toward closure in the debate over negative campaigning and turnout. J. Polit. 68, 684–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00454.x

Bullock, J. G. (2011). Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 105, 496–515. doi: 10.1017/s0003055411000165

Calvert, R. L. (1985). The value of biased information: a rational choice model of political advice. J. Polit. 47, 530–555. doi: 10.2307/2130895

Cancela, J., Dias, A. L., and Lisi, M. (2016). The impact of endorsements in intra-party elections: evidence from open primaries in a new Portuguese party. Politics 37, 167–183. doi: 10.1177/0263395716680125

Carlsen, A., and Grullon Paz, I. (2018). Trump’s endorsements: the loyalists, rising stars, and safe bets he’s picked. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/08/14/us/elections/trump-endorsements-midterms.html

Chou, H. Y. (2015). Celebrity political endorsement effects: a perspective on the social distance of political parties. Int. J. Commun. 9, 523–546.

Fahey, K., Weissert, C. S., and Uttermark, M. J. (2018). Extra, extra, (don’t) roll-off about it! Newspaper endorsements for ballot measures. State Polit. Policy Q. 18, 93–113. doi: 10.1177/1532440018759269

Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Friess, S. (2022). A bloody republican primary. Available at: https://www.magzter.com/stories/News/Newsweek-Europe/A-Bloody-Republican-Primary

Gabriel, T. (2021). Republicans fear flawed candidates could imperil key senate seats. New York: The New York Times.

Gay, L. R., and Airasian, P. (2002). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications. Hoboken: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Gerber, E. R., and Phillips, J. H. (2003). Development ballot measures, interest group endorsements, and the political geography of growth preferences. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 47, 625–639. doi: 10.1111/1540-5907.00044

Goldstein, K., and Freedman, P. (2002). Campaign advertising and voter turnout: new evidence for a stimulation effect. J. Polit. 64, 721–740. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00143

Granberg, D. (1982). Social judgment theory. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 6, 304–329. doi: 10.1080/23808985.1982.11678502

Grofman, B., and Norrander, B. (1990). Efficient use of reference group cues in a single dimension. Public Choice 64, 213–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00124367

History of the Busch family. (2008). St. Louis Post-Dispatch [St. Louis, MO], A6. Available at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A181131722/STND?u=kennesaw_mainandsid=bookmark-STNDandxid=42512a77

Hopp, T., and Vargo, C. J. (2017). Does negative campaign advertising stimulate uncivil communication on social media? Measuring audience response using big data. Comput. Hum. Behav. 68, 368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.034

Jackson, D. J., and Darrow, T. I. A. (2005). The influence of celebrity endorsements on young adults’ political opinions. Int. J. Press Polit. 10, 80–98. doi: 10.1177/1081180x05279278

Jacobson, G. C. (2019). Extreme referendum: Donald Trump and the 2018 midterm elections. Polit. Sci. Q. 134, 9–38. doi: 10.1002/polq.12866

Jacobson, L. (2022). Wide-open primaries complicate competitive November senate races. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/news/elections/articles/2022-03-10/wide-open-primaries-complicate-competitive-november-senate-races

Johnson-Cartee, K. S., and Copeland, G. (1989). Southern voters’ reaction to negative political ads in 1986 election. Journal. Q. 66, 888–986. doi: 10.1177/107769908906600417

Johnson-Cartee, K. S., and Copeland, G. (1991). Candidate-sponsored negative political advertising effects reconsidered. Boston: Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication.

Kaid, L. L., and Boydston, J. (1987). An experimental study of the effectiveness of negative political advertisements. Commun. Q. 35, 193–201. doi: 10.1080/01463378709369680

Kite, A. (2022). Lucas Kunce is betting outspoken populist message can turn Missouri senate seat blue. Available at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A710739982/STND?u=kennesaw_mainandsid=bookmark-STNDandxid=16e1bdc0

Kousser, T., Lucas, S., Masket, S., and McGhee, E. (2015). Kingmakers or cheerleaders? Party power and the causal effects of endorsements. Polit. Res. Q. 68, 443–456. doi: 10.1177/1065912915595882

LaTour, A. (2021). Heart of the Primaries 2022, Democrats. Available at: https://ballotpedia.org/Heart_of_the_Primaries_2022

Lau, R. R., Sigelman, L., and Rovner, I. B. (2007). The effects of negative political campaigns: a Meta-analytic reassessment. J. Polit. 69, 1176–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00618.x

Lupia, A. (1992). Busy voters, agenda control, and the power of information. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 86, 390–403. doi: 10.2307/1964228

Ma, T., Atkin, D., Snyder, L. B., and van Lear, A. (2019). Negative advertising effects on presidential support ratings during the 2012 election: a hierarchical linear modeling and serial dependency study. Mass Commun. Soc. 22, 196–221. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2018.1536997

McCracken, G. (1986). Culture and consumption: a theoretical account of the structure: a theoretical account of the structure and movement of the cultural meaning of consumer goods. J. Consum. Res. 13, 71–84. doi: 10.1086/209048

McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. J. Consum. Res. 16, 310–321. doi: 10.1086/209217

McKelvey, R. D., and Ordeshook, P. C. (1985). Elections with limited information: a fulfilled expectations model using contemporaneous poll and endorsement data as information sources. J. Econ. Theory 36, 55–85. doi: 10.1016/0022-0531(85)90079-1

Merritt, S. (1984). Negative political advertising: some empirical findings. J. Advert. 13, 27–38. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1984.10672899

Miller, F. M., and Allen, C. T. (2012). How does celebrity meaning transfer? Investigating the process of meaning transfer with celebrity affiliates and mature brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 22, 443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.11.001

Nicholson, S. P. (2011). Polarizing Cues. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 56, 52–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00541.x

Paek, H.-J., Pan, Z., Sun, Y., Abisaid, J., and Houden, D. (2005). The third-person perception as social judgment: an exploration of social distance and uncertainty in perceived effects of political attack ads. Commun. Res. 32, 143–170. doi: 10.1177/0093650204273760

Perloff, R. M. (2017). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Pinkleton, B. E. (1998). Effects of print comparative political advertising on political decision-making and participation. J. Commun. 48, 24–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02768.x

Pinkleton, B. E., Um, N.-H., and Austin, E. W. (2002). An exploration of the effects of negative political advertising on political decision making. J. Advert. 31, 13–25. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2002.10673657

Reid, S. A. (2012). A self-categorization explanation for the hostile media effect. J. Commun. 62, 381–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01647.x

Research Computing, Kennesaw State University. (2023). Digital commons training materials. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/training/10

Rosenthal, A. M. (1992). On my mind; It’s the economy, stupid: [Op-Ed], New York Times. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/on-my-mind-economy-stupid/docview/428730041/se-2?accountid=11824

Sherif, C. W., Sherif, M., and Nebergall, R. E. (1965). Attitude and attitude change: the social judgment-involvement approach. Westport: Greenwood Press.

State Historical Society of Iowa. A Chicken for Every Pot. (1928). Available at: https://iowaculture.gov/history/education/educator-resources/primary-source-sets/great-depression-and-herbert-hoover/chicken

State of Missouri. (2022). Official election returns. Available at: https://www.sos.mo.gov/CMSImages/ElectionResultsStatistics/PrimaryElectionAugust2_2022.pdf

Summary, B. (2010). The endorsement effect: an examination of statewide political endorsements in the 2008 democratic caucus and primary season. Am. Behav. Sci. 54, 284–297. doi: 10.1177/0002764210381709

Vining, R. L., and Wilhelm, T. (2011). The causes and consequences of gubernatorial endorsements. Am. Politics Res. 39, 1072–1096. doi: 10.1177/1532673x11409666

Vizcarrondo, T. (2021). It’s my party, I’ll endorse if I want to: effects of intra-party endorsements. Southwestern Mass Commun. J. 37:91. doi: 10.58997/smc.v37i1.91

Vizcarrondo, T., and Painter, D. L. (2020). Do endorsements trump issues? Heuristic and systematic cues in midterm elections. Florida Commun. J. 48, 67–92.

Wei, R., and Lo, V. H. (2007). The third-person effects of political attack ads in the 2004 U.S. presidential election. Media Psychol. 9, 367–388. doi: 10.1080/15213260701291338

Zanona, M., and Caygle, H. POLITICO. (2020), Pelosi, AOC, Gaetz: the dam is breaking on playing in primary battles. Available at: https://www.politico.com/news/2020/08/28/pelosi-ocasio-cortez-gaetz-congress-support-primary-battles-403794.

Keywords: political endorsement, elections, message tone, partisan primaries, social judgment theory, Meaning Transfer Model

Citation: Vizcarrondo T and Minooie M (2024) It’s not just what you say: the impact of message tone on intra-party endorsements. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1363974. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1363974

Edited by:

Marco Lisi, NOVA University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Antonella Seddone, University of Turin, ItalyLuciana Manfredi, ICESI University, Colombia

Copyright © 2024 Vizcarrondo and Minooie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tom Vizcarrondo, dHZpemNhcnJAa2VubmVzYXcuZWR1

Tom Vizcarrondo

Tom Vizcarrondo Milad Minooie

Milad Minooie