- Political Science Department, Institute for Social Sciences, University of Kaiserslautern-Landau (RPTU), Landau in der Pfalz, Germany

Since the 1990s, the number and international authority of regional organizations (ROs) have increased significantly. Former national decisions are increasingly being taken at the regional level, affecting governance in (democratically constituted) member states. Brexit demonstrated that democratic legitimacy could play a central role for ROs. As states have different (power) resources and political cultures and often do not benefit equally from their membership, democratic legitimacy likely varies between RO member states. This contribution provides a measurement of the democratic legitimacy of a RO’s governance in member states in a selected policy field. The newly developed analytical model can be applied to various ROs and is based on input, throughput, and output legitimacy and the empirical acceptance of a RO and its processes. The requirements for democratic legitimacy vary with the authority and intervention of a RO vis-à-vis its member states, and the concept of democracy contained in input legitimacy is oriented towards the normative core of democracy. This analytical approach aims to highlight and compare the democratic legitimacy of various members of a RO in new or established policy fields and contribute to the discussion on why a member state leaves a RO.

1 Introduction

Legitimacy is understood as ‘the normative justification of political authority’ (Kriesi, 2013, 614) and is an important component of a political system’s persistence (Weber, 1922, 122–124). This also applies to the numerous international and regional organizations (IOs/ROs) that have emerged since the 1990s. Following Hooghe et al. (2017a), IOs are defined as an association of three or more states ‘having a distinct physical location or website, a formal structure (…), at least 30 permanent staff, a written constitution or convention, and a decision body that meets at least once a year’ (Hooghe et al., 2017a, 16). According to Panke et al. (2020), ROs are seen as IOs whose membership is based on geographical criteria (Panke et al., 2020, 22).

The rise of IOs/ROs is linked to an increase in international authority (Hooghe et al., 2019a, 38). With the transfer of various policy fields to arenas beyond the nation-state, many formerly domestic decisions are now made in IOs/ROs (Zürn, 2018, 109–111). For citizens of the EU as the most integrated RO, this often means little direct influence on policy outcomes that affect them directly (Schmidt, 2013, 12). This was particularly evident in the Euro crisis (Scharpf, 2014; Zeller, 2018).

In recent years IOs/ROs have become increasingly politicized and contested by societal actors and states (Zürn, 2018; Rauh and Zürn, 2019). The increasing influence of globalization-skeptical populists led to rising protectionism and nationalism (Rauh and Zürn, 2019), as demonstrated, for example, by Brexit or Donald Trump’s presidential term in office in the United States (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Whether these counter-reactions can be attributed to the rise of international authority is subject to intense debates (e.g., Rittberger and Schroeder, 2016; Zürn, 2018; Rauh and Zürn, 2019). For Schäfer and Zürn (2021), for example, the politicization of non-majoritarian institutions rises with increasing authority and unpopular decisions combined with blame-shifting over a longer period of time (Schäfer and Zürn, 2021, 118–119).

More recently, reference is often made to the legitimacy of IOs/ROs (Tallberg and Zürn, 2019, 591; Benz, 2018; Zürn, 2018). For Rauh and Zürn, there is overwhelming evidence of a severe legitimacy crisis of international authority, especially in the economic sphere (Rauh and Zürn, 2019, 23). Hooghe et al. (2019a) also ‘suggest that IO legitimacy is embedded in ideological contestation’ (Hooghe et al., 2019a, 739). Subsequently, legitimacy also plays a central role for organizations above the nation-state (e.g., Benz, 2018, 330; Tallberg and Zürn, 2019) as it is considered a justification of authority (Bodansky, 1999, 600–601): ‘If state rule is to be both effective and liberal, it thus requires legitimacy as a functional precondition’ (Scharpf, 2009, 245).

Since the 1990s ROs have broadened their policy scope (Panke et al., 2020, 35) and ‘have a considerable impact on the lives of many people throughout all regions around the world’ (Panke et al., 2020, X), Also, citizens have high expectations about regional development, security and employment, while regional integration is multidimensional and includes political, economic, social and cultural aspects. This is why the legitimacy of regional governance deserves special attention (van der Vleuten and Ribeiro Hoffmann, 2007, 4). So, I explicitly refer to ROs even though in the literature the differentiation between IOs and ROs is handled diversely: Some authors simply mention IOs (e.g., Hooghe et al., 2019a; Sommerer et al., 2022) or ‘international authority’ (e.g., Zürn, 2018) and consider them to be both IOs and ROs. Others refer to regional international organizations (e.g., van der Vleuten and Ribeiro Hoffmann, 2007; Panke, 2020), or explicitly to ROs (Panke et al., 2020) or regional institutions (Rittberger and Schroeder, 2016).

Power or authority is only legitimate if it ‘is acquired and exercised according to justifiable rules, and with evidence of consent’ (Beetham, 1991, 3). As especially in the democratic constitutional states of the West, democracy is seen as the ‘dominant idea of legitimacy’ (Westle, 1989, 22; Zürn, 2011, 604; Kriesi, 2013, 614), aspects of democratic theory must be included in the assessment of legitimacy of ROs. Around the year 2000, attention increasingly focused on deficits of the democratic legitimacy of IOs/ROs due to their growing political influence. An initial wave of studies examined how well ROs meet the standards of a legitimate political order, focusing on the EU’s legitimacy deficit. Recent research analyzes political behavior and discourse to understand how actors within ROs deal with shortcomings related to legitimacy. However, research on these questions is strongly focused on the EU, as the EU is the most integrated RO (Rittberger and Schroeder, 2016, 579–580). For less integrated ROs around the world, such as the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) or the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM), these legitimacy issues have not arisen as much, so the literature to date is highly Eurocentric.

Many contributions concerning legitimacy or politicization of IOs/ROs (e.g., Hutter and Kriesi, 2019; Rauh and Zürn, 2019) refer to the beliefs in their legitimacy. Democratic rule in IOs/ROs plays, if at all, a rather subordinate role. The fact that democratic legitimacy of ROs was often seen as unnecessary surely contributed to this: One argument was that output would compensate for the lack of participation by providing the benefits of regional cooperation in terms of prosperity and peace (e.g., Majone, 1998; Sandholtz and Stone Sweet, 1998). This argument was valid as long as ROs had little international authority. However, with increasing intervention in national affairs, governance within a RO is only democratically legitimate if input legitimacy, that is the perspective that emphasizes “government by the people” (Scharpf, 1999, 16), is given. Others consider the democratic constitution of the member states to be sufficient, as the national parliaments would approve the decisions taken at the regional level (e.g., Schmidt, 2006). This presupposes that governance in RO does not undermine the democracy of its member states. However, as the international authority of RO increases, effects on the domestic democracy of the member states cannot be ruled out (van der Vleuten and Ribeiro Hoffmann, 2007, 8). As a result, input legitimacy of RO is increasingly gaining focus. However, the elaborations on democratic legitimacy of IOs/ROs mostly refer to only one specific case (e.g., von Engelhardt, 2016) and/or do not include a deeper definition of what exactly is meant by democratic. In sum, there is not much knowledge about the democratic legitimacy of ROs except for the EU (Rittberger and Schroeder, 2016, 584) and the empirical legitimacy of specific IOs/ROs. The volume by van der Vleuten and Ribeiro Hoffmann (2007), in which Berry Tholen presents a ‘Conceptual Clarification’ on ROs’ legitimacy and democracy (Tholen, 2007) and Bob Reinalda compares ‘Input, Control and Output Legitimacy’ of 31 ROs (Reinalda, 2007), is an important exception. However, 2007 is not 2024, and the world has changed significantly since then.

The effects of the increasing authority of ROs on their acceptance and democratic legitimacy on the one hand, but also challenges such as Brexit and the increasing politicization of ROs on the other, require systematic analysis to identify cause-and-effect relationships. Understanding the democratic legitimacy of different ROs from the perspective of member states provides a basis for further analysis which does not exist so far. Therefore, this contribution aims to provide a means of measuring democratic legitimacy in various ROs for member states concerning a selected policy field. For this purpose, a theoretical framework of democratic legitimacy in ROs is developed, in which the interaction between ROs and member states serves as the analysis unit.

Most concepts of democratic legitimacy refer to the relationship between nation-states and their civil society (van der Vleuten and Ribeiro Hoffmann, 2007, 7). However, a RO is not a state actor. Thus, the concept of democratic legitimacy is applied to a different object (ROs and their member states). In order to create such an analytical framework with an associated measurement concept, research findings from the fields of international relations, comparative politics and political philosophy must be taken into account, and various steps are required: First, the causes and nature of regional cooperation must be identified, and authority and legitimacy have to be defined. Second, the most appropriate concepts for democratic legitimacy and democracy above the nation-state are needed. The criteria used to assess the suitability of the various approaches are an intrinsic logical coherence and a conception of democratic legitimacy with a vision of democracy for governance beyond the nation-state that can be applied globally. In addition, a suitable concept of democratic legitimacy for governance in ROs should be applicable to more than one case and to real processes and not just institutions. Third, a specified concept of democratic legitimacy in ROs is derived from these definitions and concepts, and variations in the requirements of democratic legitimacy in ROs are introduced. These variations are due to the decision-making and intervention modes of the RO in the affairs of member states. Fourth, variables and indicators for the requirements are proposed, and an illustration of the subsequent measurement is given. Concluding, research perspectives beyond this measurement are demonstrated.

2 Background concepts

In this chapter, the following question is to be answered: What concepts should be considered when determining the democratic legitimacy of different ROs from the perspective of their member states?

2.1 ROs—characterization, authority, power, and legitimacy

ROs often emerge because of international cooperation or integration. Significant reasons for intergovernmental cooperation include realizing objectives (Keohane, 1984, 51–52), reducing transaction costs (effectiveness), and facilitating issue linkages ‘within regimes and between regimes’ and processes ‘that are consistent with the principles of the regime’ (Keohane, 1984, 244). Different integration theories emphasize the different motives that motivate nation-states to cooperate or integrate.1 However, the importance of the output of regional cooperation should not be underestimated in the context of the reasons why ROs were established. The resulting organizations can have few member states like the Economic Community of the Great Lakes Countries or many member states like the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and their policy scope can be selective as with the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, or encompassing as with the African Union (Panke and Starkmann, 2019; Panke et al., 2020, 15–22). With the emergence of ROs governance transcends state borders and is increasingly taking place in multilevel systems (Benz, 2010, 66). Multilevel means that ‘actors from different levels˗nation state, regional, local, and international’ (Trein et al., 2019, 343) are involved in finding common policy solutions.

Organizations like ROs can also be seen as natural, rational or open systems (Scott and Davis, 2016, 35–106) or as a political system, as Schmidt and Schünemann do with the EU, for example. Here, the political system consists of the RO and its institutions as well as its member states. The demands and aggregated interests from the member states represent the inputs, the adopted legal acts the outputs (Schmidt and Schünemann, 2013, 54–57). In contrast to output, which means a result of the processes of the political system, outcome refers to the long-term effects that result from the output. Based on this, ‘efficiency is the ratio between inputs and outputs, whereas effectiveness is the degree to which the desired outcomes result from the outputs’ (Pollitt and Buchaert, 2011, 15). It should be noted that ROs, like states and other organizations, are exposed to external influences that go beyond the “normal” inputs and affect their performance. These may include environmental disasters, terrorist attacks, pandemics or other crises such as the global economic and financial crisis from 2008 onwards. Whether the resulting crisis management is successful depends on both, governance capacities and governance legitimacy (Christensen et al., 2016, 887). It is not only in crisis management that the outcomes of ROs may not fit all member states in the same way: In addition to possibly different systems of government and types of capitalism, there may also be different expectations of citizens and cultural constraints in the member states (Christensen et al., 2016, 895). This means that a RO may be recognized differently in its member states.

For Hooghe et al. (2017a), IOs/ROs are ‘the principal source of political authority’ (Hooghe et al., 2017a, 121) on the international level. Their creation raises the question of how to justify delegating authority and power to governing bodies (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, 2017, 197). However, power and authority are terms that are interpreted differently (Voelsen and Schettler, 2019), and these terms must be seen in the context of domination. For Weber, ‘authority’ and ‘domination’ are synonymous and determine if certain (or all) commands of a given group of people will be obeyed. In doing so, he distinguishes authority from other forms of power: people obey the orders of authority not out of self-interest or fear but because they recognize the authority’s right to give orders (Voelsen and Schettler, 2019, 543). Here, authority is a special form of power. Power in the sense of Weber’s influential definition means the chance to impose one’s will within a social relationship even against resistance, regardless of what this chance is based on (Weber, 1922, 28); that is, authority is ‘legitimate power’:

‘One speaks of authority if B regards A’s command as legitimate and correspondingly has an obligation to obey. Authority implies power, but power does not imply authority. Whereas power is evidenced in its effects irrespective of their cause, authority exists only to the extent that B recognises an obligation resting on the legitimacy of A’s command’ (Hooghe et al., 2017a, 14).

There are two dimensions of authority of IOs/ROs: delegation, where member states delegate authority to an independent body above the nation-state and pooling, as collective governance by the member states (Hooghe et al., 2017a, 21–23; Sommerer et al., 2022, 819–820). Zürn’s (2018) reflexive concept of authority ‘sees authority in global governance as deriving from epistemic foundations that include the permanent monitoring of authorities’ (Zürn, 2018, 41). He distinguishes between political authority ‘to make decisions’ and epistemic authority ‘to make interpretations’ (Zürn, 2018, 50–51). His measurement of international authority, therefore, includes recognizing an institution’s interpretations and decisions, delegated or pooled competences, and mandates (Zürn, 2018, 108–109). Moreover, the authority of IOs/ROs varies between organizations and over time as well as between policy fields within an IO/RO (Hooghe et al., 2017a, 117–132; Zürn, 2018, 109–111; Hooghe et al., 2019b, 38–43; Panke et al., 2020).

Inter-state relations, as occur in ROs, also touch on the question of power, and potential and real power imbalances between states should not be ignored either. According to Farrell and Newman (2021), complex systems tend to produce asymmetric network structures that can be a starting point for ‘weaponized interdependence’ in which some states can use interdependent relations to coerce others (Farrell and Newman, 2021, 21). In the context of IOs/ROs and legitimacy, this could mean that if powerful states permanently impose their will within an IO/RO at the expense of weaker states, the legitimacy of an IO/RO from the perspective of the weaker states is undermined.

The considerations so far lead to the following conclusion: If the authority of ROs, internal power structures between RO member states as well as different national circumstances and different policy outcomes in member states of a RO are to be taken into account when considering legitimacy of a RO, the member state level must be part of the analysis. Subsequently, the interaction between ROs and member states should be the analysis unit. Also, the policy scope and authority of IOs/ROs vary considerably between IOs/ROs and policy fields within an IO/RO. Therefore, not all policy fields of a RO can be investigated simultaneously, but the investigation must refer to one policy field per analysis unit.

What is meant by legitimacy in the context of IOs/ROs? Even with regard to the state, legitimacy is a complex, multidimensional and ambiguous concept (Wiesner and Harfst, 2019, 12, Tholen, 2007, 18). It is ‘the central issue in social and political theory’ (Beetham, 1991, 41), and is understood in different ways. The theoretical approaches to legitimacy can be distinguished by their different consideration of normative and empirical criteria. Normative conceptions of legitimacy refer to a political order’s acceptability and justification (Habermas, 1976, 39; Zürn, 2011, 606). The acceptability of a political system results from its compatibility with basic normative principles shared and anchored in the society concerned (Abromeit and Stoiber, 2007, 36; Zürn, 2011, 606). Habermas, for example, sees the acceptability of a state only as given when its fundamental rights and positive law have been established by applying the principle of discourse (Habermas, 1992, 151–165). Empirical conceptions focus on a political system’s recognition or the belief in its legitimacy by its citizens (Beetham, 1991, 5–6). The emphasis here is on the public perception of economic performance, political responsiveness, or satisfaction with democracy per se (Carstensen and Schmidt, 2018, 756–757). These conceptions can be traced back to Weber. For him, legitimacy is closely linked to the willingness to obey authorities: if the governed believe in the legitimacy of a relationship of rule, it can be maintained collectively in a binding manner without the use of violence (Weber, 1922, 122–124; Lauth, 2019, 841) and replace coercion (Rittberger and Schroeder, 2016, 580). Weber focuses on the causes of citizens’ beliefs in legitimacy, distinguishing rational, traditional, and charismatic rule (Weber, 1922, 122–124). Rational rule, which includes democracy, becomes legitimate through adherence to formally established ‘procedures of political will formation’ and the belief in the legitimacy of the rulers (Westle, 1989, 23ff). Theoretical approaches that are more management-oriented also relate to empirical concepts, for example by defining legitimacy as ‘a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’ (Suchman, 1995, 574). In another perspective, a political system is legitimate only if it fulfils normative requirements and is recognized as legitimate by the citizens affected. This is the view of Beetham (1991), for example. For him, ‘[…] the threefold normative structure of legitimacy [is defined] as validity according to rules, the justifiability of rules in terms of shared beliefs, and expressed consent on the part of those qualified to give it’ (Beetham, 1991, 97).

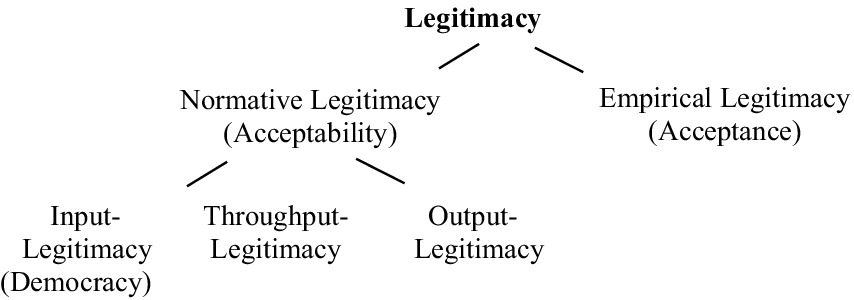

In addition, normative legitimacy approaches can be differentiated according to their consideration of input-, throughput- and output-legitimacy. Scharpf introduced the input- and output-oriented legitimacy of the EU with reference to Lincoln’s ‘government of the people, by the people, and for the people’. His input legitimacy focuses on political representation and responsiveness, while output legitimacy mostly refers to effectiveness and performance (Scharpf, 1999, 16–28). Later, Schmidt added throughput legitimacy, which focuses on the procedural quality of governance (Carstensen and Schmidt, 2018, 757; Schmidt, 2013). These different components of legitimacy are summarized in Figure 1.

Furthermore, there is a distinction between legitimacy as a state and legitimation as a process in which legitimacy is created (Abromeit and Stoiber, 2007, 37; von Engelhardt, 2016, 30–32). Hereafter, the focus is on legitimacy as a state, and legitimation is only briefly considered: Numerous publications address the legitimation of organizations or IOs/ROs (e.g., Suchman, 1995, 585–601; Dingwerth et al., 2019; Moschella et al., 2020) and their politicization (e.g., Zürn, 2013; Hutter and Kriesi, 2019; Rauh and Zürn, 2019). Regarding the EU, for example, EU-skeptical, populist parties have been the main drivers of its politicization, especially in times of crises (Hutter and Kriesi, 2019, 1012–1014). However, the link between authority, politicization and (de)legitimation often does not run in a straight line but is mediated by specific events or national contexts. Generally, a higher degree of international authority means a higher likelihood that international institutions will be questioned in the national public sphere (Rauh and Zürn, 2019, 5). The greatest threat to international governance presently arises from ‘its perceived failure to help large numbers of voters at home’ (Hooghe et al., 2019a, 733). This could be observed, for example, in the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement initiated by the United States as of 2017. Moreover, national party systems vary, which must also be considered (Hutter and Kriesi, 2019, 1000–1003).

In his ‘Theory of Global Governance’, Zürn (2018) explains the connection between legitimation, delegitimation, and legitimacy beliefs:

‘Legitimacy beliefs are […] based on information that is derived from interpretative struggles about international authorities. […] While the objective features of IOs set certain parameters, contestation and justification of IOs affect how these features translate into legitimacy beliefs. […] it seems unreasonable to assume that legitimacy beliefs are completely unrelated to IOs, their procedures, and their policies. […] The process of legitimation and delegitimation is thus decisive for the development of legitimacy beliefs’ (Zürn, 2018, 67–68).

This corresponds to the rising efforts by IOs/ROs to increase their legitimacy using various legitimation strategies (e.g., Dingwerth et al., 2019; Tallberg and Zürn, 2019; Moschella et al., 2020). Furthermore, there is evidence of correlations between domestic political interference of an IO/RO and pressure on political elites to provide legitimacy (Rittberger and Schroeder, 2016, 587). ‘International institutions now are evaluated against normative standards and they need to be justified by reference to common norms’ (Zürn, 2018, 9). Since democracy is seen as the best possible form of political rule, this implies that the authority of collective actors exercised beyond democratically constituted states should also meet the standards of democratic rule (Benz, 2018, 330). This is why this contribution concentrates on democratic legitimacy.

Summarizing, acceptability and acceptance of those ‘affected’ should be part of legitimacy assessments: Since empirical support strongly depends on economic performance or individual satisfaction (Fuchs, 2002; Armingeon et al., 2015), autocracies and dictatorships can also be recognized and supported by their citizens. If the democratic constitution of a political system is also to play a role in assessing its legitimacy, the acceptance of a political system should not be used alone to justify its legitimacy. However, because ‘legitimacy convictions have an essential significance for system stability’ (Westle, 1989, 27), even a political system worthy of acceptability cannot exist in the long run without empirical acceptance. In many cases, ROs ‘were not perceived as democratizing agents but, on the contrary, as bulwarks for elitist policy making in the interest of some happy few’ (van der Vleuten and Ribeiro Hoffmann, 2007, 3). However:

‘The perception of legitimacy matters, because, in a democratic era, multilateral institutions will only thrive if they are viewed as legitimate by democratic publics. If one is unclear about the appropriate standards of legitimacy […], then public support for global governance institutions may be undermined […]’ (Buchanan and Keohane, 2006, 407).

In addition, determining the acceptability of ROs requires input, throughput and output legitimacy to be considered: Since achieving goals that cannot be reached alone is an important reason for international cooperation (Keohane, 1984, 51–52), output legitimacy is an important element of democratic legitimacy in ROs. In order to include democratic aspects in the assessment of the legitimacy of ROs, input and throughput legitimacy must also be part of the assessment.

2.2 Democratic legitimacy concepts and democracy beyond the nation-state

The next step is to identify a suitable concept of democratic legitimacy for governance in ROs which meets the abovementioned requirements. Therefore, various conceptions of democratic legitimacy are briefly outlined and their suitability is examined.

Several authors have dealt with democratic legitimacy of IOs/ROs without a special focus on the EU (e.g., Bodansky, 1999; Abromeit, 2002; Moravcsik, 2004; Buchanan and Keohane, 2006; Abromeit and Stoiber, 2007; Tholen, 2007; von Engelhardt, 2016). Abromeit (2002) and Abromeit and Stoiber (2007) developed a measurement system for democratic legitimacy in postnational constellations which also considers the social context, the type of governance and the complexity of a decision. This measurement system is very complex and has hardly been used so far. Moravcsik’s (2004) analytical framework to assess democratic legitimacy draws on elements of liberal, pluralist, social democratic and deliberative democracy. But its concrete application to the EU is general in nature and does not address specific policy fields or the nation-state level. Tholen’s ‘Conceptual Clarification’ on the legitimacy and democracy of RO is based on Scharpf’s theoretical elaborations, but they are specified to enable extended measurements. Tholen considers input legitimacy at the supranational level to be guaranteed if either parliamentary representatives or, under certain conditions, non-governmental organizations are involved in decision-making. Furthermore, he suggests adding control legitimacy to input and output legitimacy. In order to comply with the control dimension, judicial review and effective parliamentary or corporatist control are required. With regard to output legitimacy, consideration should also be given to the extent a RO contributes to the realization of democracy and the rule of law in the member states (Tholen, 2007, 23–25). Tholen’s concept offers an interesting approach, but does not consider the national level and does not contain a detailed definition of what is meant by democracy. As mentioned above, acceptability consists of input, throughput, and output legitimacy. In the discussion on the European democratic or legitimacy deficit (e.g., Scharpf, 1999; Moravcsik, 2002; Schmidt, 2013; Carstensen and Schmidt, 2018), from the 1990s till the outbreak of the Euro crisis, output legitimacy was sufficient for the acceptability of inter- and supranational institutions (e.g., Majone, 1998; Moravcsik, 2002). For an optimal output, a technocratic throughput was preferred to a popular input (Carstensen and Schmidt, 2018, 759). Since the Troika actions during the Euro crisis (Zeller, 2018, 114), there has been an increasing demand for more input and throughput legitimacy in the EU. Especially the contributions of Scharpf are powerful in the consideration of political input and output in multilevel systems (Schmidt, 2019, 512) and are exemplary for this development: Here, input legitimacy is based on participation and consensus. The legitimating power decreases with increasing distance between the governed and the governors. As soon as majority decisions are necessary, the question of the justification of majority rule arises (Scharpf, 1999, 17). To ensure that the overruled minority recognizes the vote of the majority, trust in the goodwill of fellow citizens is essential (Scharpf, 1999, 17–18). Moreover, majority decisions are more problematic in more heterogeneous societies (Scharpf, 1999, 168). Output legitimacy is derived from the ability to solve problems that call for collective solutions, and this requires sufficiently large common interests that justify institutional agreements for collective action (Scharpf, 1999, 20–28). Without the fulfilment of the function of the common good, the legitimacy of a political regime is endangered.

Between the nation-states and the European level, there is a two-tier legitimacy relationship between the citizens and the nation-states on the one hand and the nation-states and the EU on the other. Legitimacy is focused here from the perspective of the member state willing to comply (Scharpf, 2009, 253). This perspective is confirmed by most international law scholars, who see the democratically constituted nation-state as an essential framework for realizing the democratic principle and as a cardinal point of the international system (von Engelhardt, 2016, 98–99).

Governing in multilevel systems like ROs also results in an effectiveness-legitimacy dilemma: nation-states are shifting competences to supranational levels to solve numerous problems, but democratic legitimacy cannot be sufficiently provided there (Schmidt, 2019, 252). In examining the causes of states’ willingness to comply with EU regulations, Scharpf identifies different ‘types of Europeanisation’ (Scharpf, 2002, 71), the first differentiated assessment of legitimacy depending on the type of decision-making. In unanimous intergovernmental agreements, the legitimacy of political decisions can be derived from the democratic legitimacy of the national governments. Supranational bodies legitimize themselves solely through faith in the authority of law and the problem-solving ability of technically qualified authorities (Scharpf, 2002, 75). In the mode of policy interdependence [Politikverflechtung], the legitimacy of the Council of Ministers’ decisions diminishes with the increasing influence of supranational bodies (European Commission or European Central Bank). Alternatively, with legitimacy sources, such as the openness of decision-making processes, the responsiveness of European networks to mediate interests and deliberation in comitology are emphasized. Due to the lack of transparency in diverse procedures, Scharpf doubts that those affected can understand what happens at the European level (Scharpf, 2002, 80–81).

Moreover, the intervention in national affairs should not be neglected. The interventions of ROs in member state affairs gained attention especially during the saving of the Euro (Scharpf, 2014; Armingeon et al., 2015; Zeller, 2018). However, there is no general definition for the domestic political interference of an IO/RO. Considering the Euro crisis, the current ROs and their authority as well as their policy fields (Hooghe et al., 2017a; Panke and Starkmann, 2019; Zürn et al., 2021), I propose the following definition: The interventions of ROs in member state affairs result from a combination of the authority of a RO with the influence of the respective political decisions on legislation, the state budget, and state-determined transfers to citizens or wages for state employees in the member states. During the Euro crisis, European institutions influenced the living conditions of millions of citizens and exercised political power directly and visibly. Even input legitimacy on the national level was practically suspended (Scharpf, 2014; Zeller, 2018, 114–117). Scharpf classifies the saving of the Euro as foreign rule combined with an authoritarian regime of experts, denying its legitimacy (2014). This view is shared by various parties [e.g., European Parliament (EP), 2014; Armingeon et al., 2015; Puntscher Riekmann, 2016, 214–219]. Carstensen and Schmidt (2018) also see a problem for national input legitimacy as the EU interfered increasingly in national decision-making (Carstensen and Schmidt, 2018, 760). The former trade-off between input and output, where good policy outcomes compensate for the lack of citizen participation, seems to have disappeared with the saving of the Euro. Throughput legitimacy does not compensate for input or output deficits. While high throughput legitimacy has no problematic consequences for input and output legitimacy, low throughput legitimacy can undermine input and output legitimacy (Schmidt, 2013, 19).

Summing up these considerations on democratic legitimacy in ROs, it means that both the type of decision-making and the level of intervention into nation-state affairs matter for the future assessment. The analysis of European integration demonstrated furthermore, that up to a certain degree of interference in national affairs, throughput and output legitimacy might be sufficient for the democratic legitimacy of governance within a RO. However, deep interventions in national state affairs, such as the measures to save the Euro, require democratic input legitimacy (Scharpf, 2014, 56–58). In this case input, throughput and output legitimacy are needed in order to be acceptable. In doing so, an element of control should be considered, too.

To further specify democratic legitimacy, input legitimacy must be defined more precisely than has been the case so far. This specification is directly related to the underlying definition of democracy. The term ‘democracy’ is composed of the Greek words ‘demos’ and ‘kratein’ and can be translated as the rule of the people (Schmidt, 2019, 1); however, the exact meaning of democracy is controversial (Merkel, 2015, 9).

The concept of democracy has undergone various transformations (Dahl, 1994). Since representative democracy cannot be transferred to ROs for various reasons mentioned below, the definition of democracy used here is oriented towards its normative core. To elaborate on this core, Dahl’s transformations are supplemented by significant democratic theory concepts from the corresponding era.

According to Dahl (1994), the first transformation took place in Greece when monarchic, aristocratic, and oligarchic city-states became democratic city-states. Democracy was almost exclusively related to small city-states and the assembly in which citizens were authorized to participate (Dahl, 1994, 25), demonstrating that citizen participation has always been a core element of democracy. Aristotle sees democracy as a rule for the benefit of the destitute. His counterpart to democracy is ‘Politie’. There, the noble, free, and rich men administer the state regarding the common good. When the rulers start to rule for their benefit instead of the common good, the rule becomes defective (Aristotle, 2003, 168–170). Freedom and equality are also important elements of democracy for Aristotle: ‘If […] freedom prevails first in a democracy […] and equality, then it should exist primarily where all together participate in the same way, especially in the constitution of the state’. Also, state constitutions and thus democracy no longer exist if voting results are above the laws (Aristotle, 2003, 212–213). Thus, the rule of law is also considered an important element of democracy.

The second democratic transformation occurred when ‘the idea of democracy was transferred from the city-state to the much larger scale of the national state’, made possible by representation (Dahl, 1994, 25). In the Federalist Papers, the authors consider representation to extend the republic (the former name for democracy) to a larger territory. Elected representatives oriented toward the common good in a large, federally structured republic are necessary to protect the public good and private rights (Schmidt, 2019, 91). To ensure the negative freedom rights of citizens (Scharpf, 2009, 247) and protect the republic from a tyranny of the majority, political rule must be limited to a greater extent. Therefore, the republic is provided with elements of control consisting of a combination of separation and entanglement of powers and the primacy of the constitution. Even though white men (but not women and enslaved people, Schmidt, 2019, 92–96) are regarded as equal, the Federalist Papers place a much higher value on freedom than on the equality of all citizens.

The third democratic transformation must take place because the transnational system reduces the political, social, cultural, and economic autonomy of the nation-states and external actors are increasingly influencing the lives of citizens of the state but cannot control them, and often their national governments cannot either (Dahl, 1994, 26). The concepts of representative democracy assume congruence between decision-makers and those affected by their decisions. In multilevel systems created by ROs, numerous actors are active at different levels from local to international, and decision-making processes are often non-transparent. When decisions cross state, regional, or local boundaries, not all those affected can blame the decision-makers (Benz, 2010, 66). Often, national parliamentary majorities are expected to ratify legal acts that were negotiated at the level above the nation-state (Neyer, 2013, 50), and decisions at the EU level limit the ability of national parliaments to shape policy (Voigt, 2013, 22–23). This was particularly evident in the Euro crisis (Kerwer, 2016, 72). Subsequently, the currently prevailing representative democracy is not easily transferable to governance in the ‘postnational constellation’ (Habermas, 1998) respective of economic globalization (Rodrik, 2011). A deliberative democracy involving all stakeholders is not a solution either, as the ability to make decisions on complex tasks across different levels would be at the expense of quick decisions. In addition, deliberative processes are often dominated by experts and there is a risk of dominance by experts (Benz, 2010, 66–67).

As nation-states can only face cross-border challenges together, it is necessary to rethink democracy beyond the nation-state. To cope with this third transformation of democracy, a return to the normative core of democracy is proposed. Therefore, the focus is primarily on core principles associated with democracy. In summary, participation, freedom, equality, control, and the rule of law are identified as the normative core of democracy. In some democratic theories, the common good is also considered an essential principle of a democratic constitution. Here it can be equated with effectiveness, which plays an important role in governance above the nation-state (see chapter 3.1). Therefore, democracy is seen as a constitution in which the exercise of power or rule is based on political freedom and equality and citizens’ comprehensive political participation rights (Schmidt, 2019, 2). Comprehensive political participation rights can be interpreted as the participation of individuals in decisions that affect them and to which they are subjected. Merkel’s minimalist model of democracy demonstrates that a political system must include participation in terms of universal, free, and equal elections to be considered a democracy (Merkel, 2015, 10–11). Thus, considering the above-mentioned two-level structure of democratic legitimacy beyond the nation-state, if genuine democratic input is required, this means that member states’ elected representatives must have a choice between alternatives on RO level. This choice must be meaningful, giving representatives real power to shape policy. For this participation to succeed, the freedom and equality of the member states affected by a far-reaching decision must be secured through control mechanisms. To enable the governed to recognize who decided on what and hold the governors accountable later, transparency and throughput legitimacy are required. Only then can citizens participate adequately.

3 Democratic legitimacy in ROs

To provide the theoretical basis for measuring democratic legitimacy in ROs, the dimensions, elements and variations of democratic legitimacy in ROs are derived from the previous elaborations. Since the member states of a RO may differ in many respects, the national approval of a RO may vary greatly. Therefore, the member state level must be considered when determining democratic legitimacy in ROs. Thus, the analysis unit of the measurement concept will be the interaction between a RO and its member state. In addition, the findings of Hooghe et al. (2017a), Zürn (2018), and Panke et al. (2020) demonstrate that the policy scope and authority of IOs/ROs vary considerably between IOs/ROs and policy fields within an IO/RO. Therefore, the investigation must refer to one policy field per analysis unit.

The politicization and contestation of an IO/RO are likely to vary with its degree of international authority (Rauh and Zürn, 2019, 5) and the degree of intervention in the affairs of member states. Since the interventions in member state affairs also include the authority of a RO, there should be a variance in legitimacy requirements depending on the degree of intervention in the affairs of member states. Considering the different dimensions and aspects of international authority, the future measurement should also include a reference to the authority of a RO to make binding decisions for its member states. This authority can be assessed through various elements (Hooghe et al., 2017a, 9–21; Zürn, 2018, 107–111).

Political decisions are legitimate from an input-oriented perspective if they can be democratically attributed to the members of a community. For the assessment of democratic legitimacy per analysis unit and policy field, decision-making is therefore of particular interest because this demonstrates whether political decisions can be traced back to the voters of the member states. In the case of unanimous decisions at RO level, input legitimacy is already given, so no further requirements for input legitimacy arise in this case. In the case of majority decisions at RO level, input legitimacy exists to a limited extent, but it does not exist in the case of supranational decisions at RO level. Therefore, the requirements for democratic legitimacy in ROs are lower for unanimous intergovernmental decisions made with the participation of government members than for supranational decisions by technocrats, for example. In this latter case, input legitimacy needs to be ensured through alternative control mechanisms, such as parliamentary ratification of RO decisions or referenda.

Governance within ROs complements the member states’ democracy in areas where nation-states have delegated competences to ROs. Thus, the democratic legitimacy of ROs consists of two levels: the level of the nation-state and the level above the nation-state (international). If the member state is not constituted democratically, this state’s governance in a RO cannot be democratically legitimate either. Nevertheless, it can be legitimate. Legitimacy in ROs is thus a continuous variable that can assume any value between zero (no legitimacy), a threshold value for legitimacy, and a maximum value of democratic legitimacy.

Furthermore, the discussion of democratic legitimacy concepts demonstrated that the acceptability based on democratic principles and those ‘affected’ should be included in democratic legitimacy assessments. For the reasons outlined in Chapter 3, the democratic legitimacy of RO therefore has to include both acceptability and acceptance.

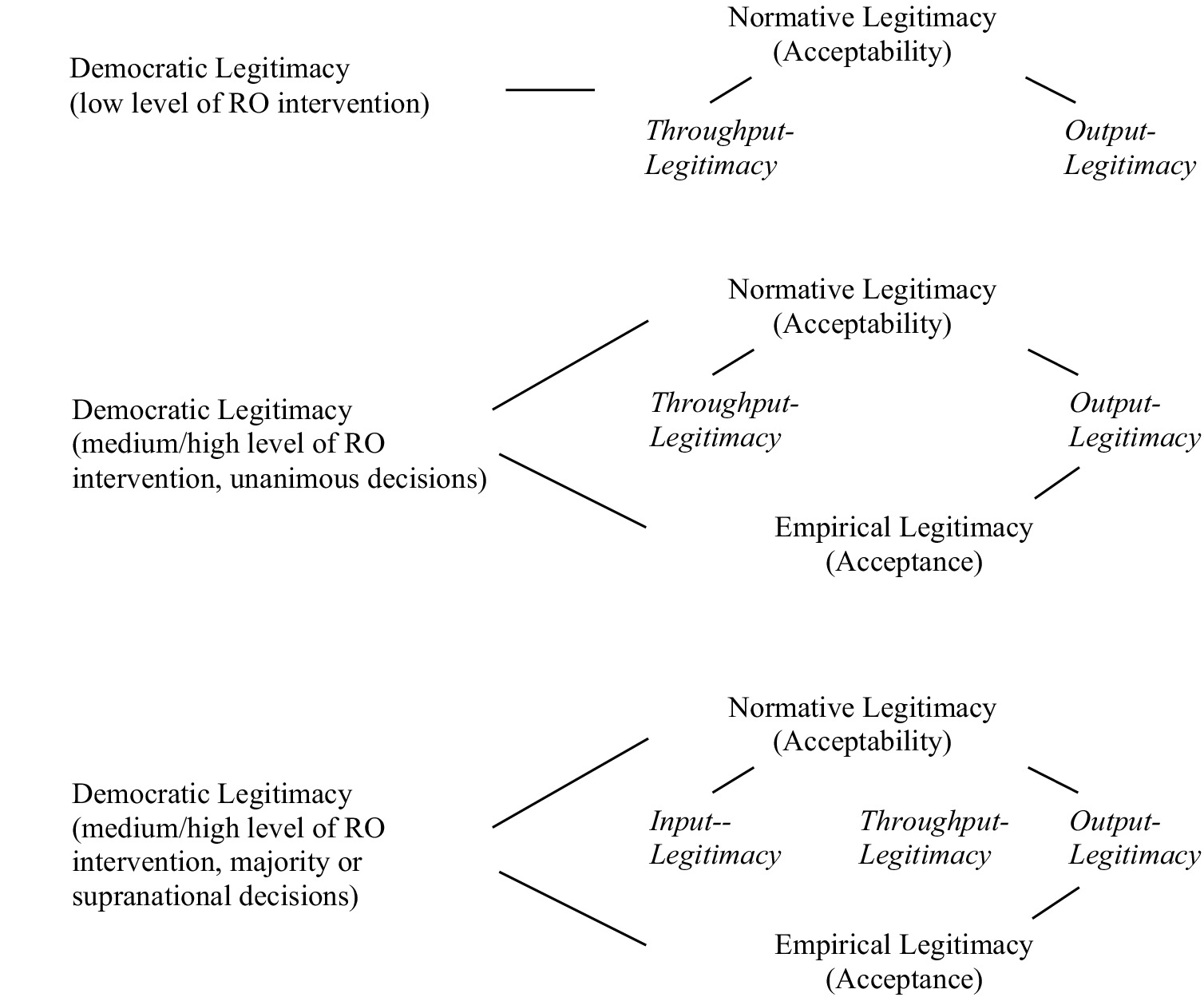

Summarizing all these considerations, the following model of democratic legitimacy for ROs can be drawn (see Figure 2). The basic prerequisite for the existence of democratic legitimacy of a RO in relation to a nation-state is always that the nation-state is constituted democratically (otherwise one can speak of legitimacy, but not of democratic legitimacy). In the case of a low level of RO intervention in national affairs, throughput and output legitimacy are sufficient to speak of democratic legitimacy of a RO in relation to a policy field and a specific nation-state. If there is a medium level of RO intervention in combination with unanimous decisions at the RO level, throughput and output legitimacy as well as empirical acceptance of the RO’s decisions by the citizens of the nation-state under study should be present in order to speak of democratic legitimacy. The link between output legitimacy and empirical legitimacy indicates that the output (and the subsequent outcome and impact) may affect the acceptance of a RO. In the case of a medium or high level of intervention and majority or supranational decisions, input, throughput and output legitimacy as well as empirical acceptance of the decisions by the citizens of the nation-state under study are required in order to speak of democratic legitimacy of a RO with regard to a policy field and this nation-state. An explanation of how the different levels are differentiated is given below.

Since representative democracy, which is dominant today, cannot simply be transferred to ROs, the focus of input legitimacy is on the normative core of democracy. Here, democracy is a form of government in which the exercise of power or rule is based on comprehensive political participation rights of citizens, which are secured by political freedom, equality, control, and the rule of law. Democratic participation means having a choice between alternatives. Consequently, elected representatives need to have real power to shape policy. For this participation to be successful, the freedom and equality of the member states concerned must be ensured through control mechanisms. For adequate citizen participation, throughput legitimacy or transparency is essential, not only within a RO. To hold the governors accountable later, the governed must be able to see who decided what.

And the common good? Regarding governance within a RO and its inherent orientation towards results and effectiveness, reasons for its existence, a focus on at least one result could be helpful. If democracy is seen as a good thing, governance within a RO should ensure that democratically governed states can remain democratically governed states.

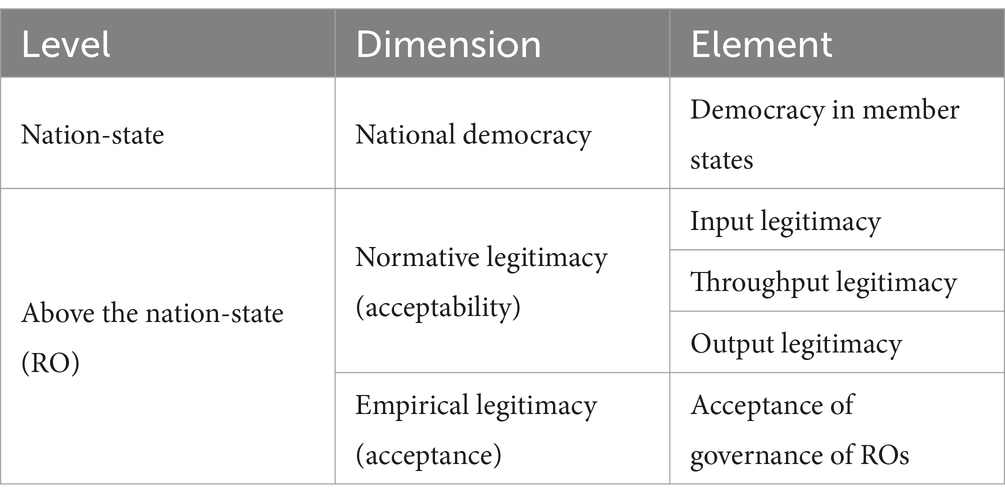

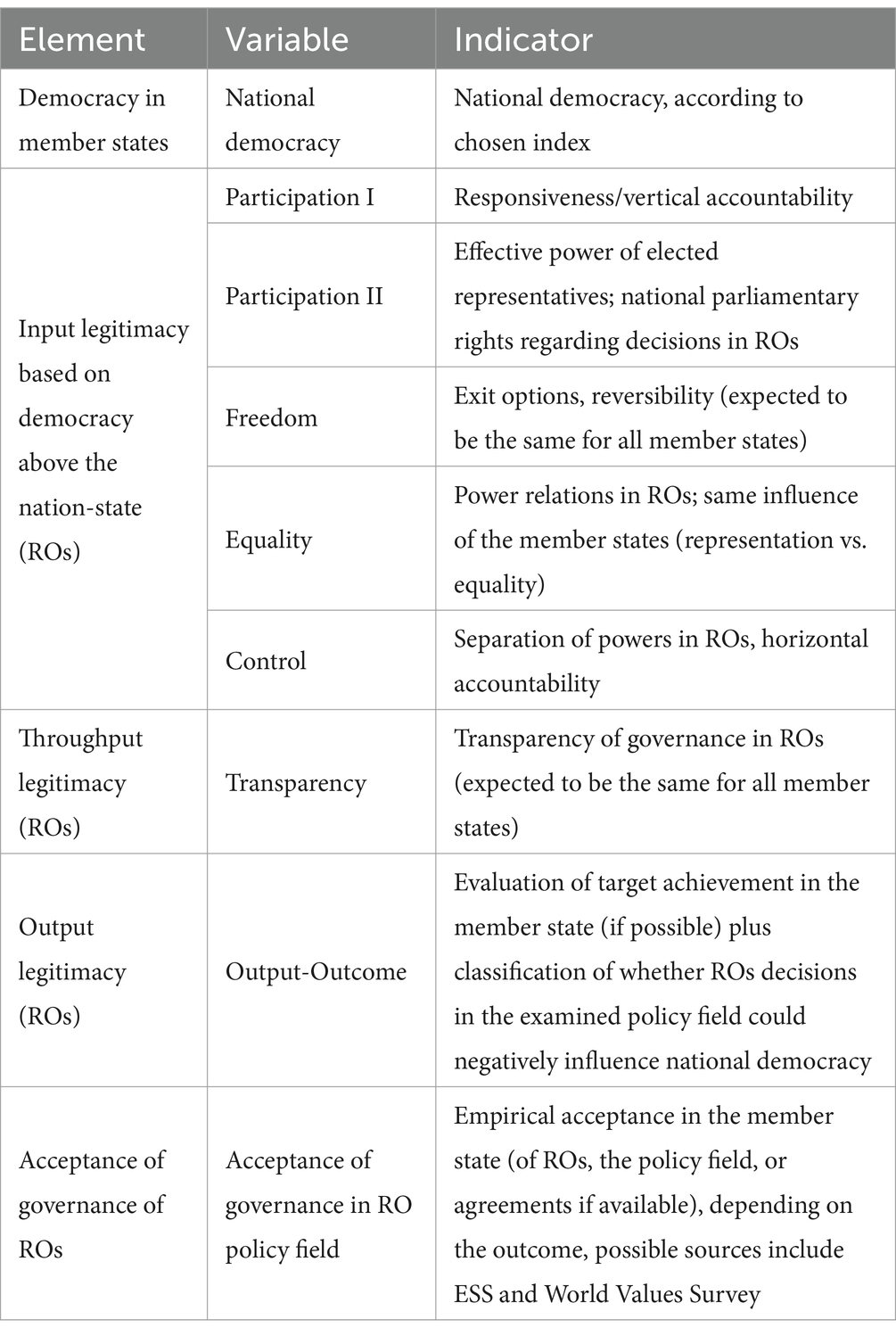

Building on these considerations, democratic legitimacy in ROs exists when democratically legitimate governance at the nation-state level is complemented by democratically legitimate governance above the nation-state in areas where authority has been transferred. The dimensions of democratic legitimacy in ROs are thus national democracy and normative and empirical legitimacy above the nation-state. In the case of the maximum requirements for democratic legitimacy in ROs (medium/high depth of RO intervention, majority or supranational decisions), this corresponds to the following elements: democracy in member states, input legitimacy based on democracy above the nation-state, throughput legitimacy, output legitimacy, acceptance of governance of ROs. These considerations are summarized in Table 1.

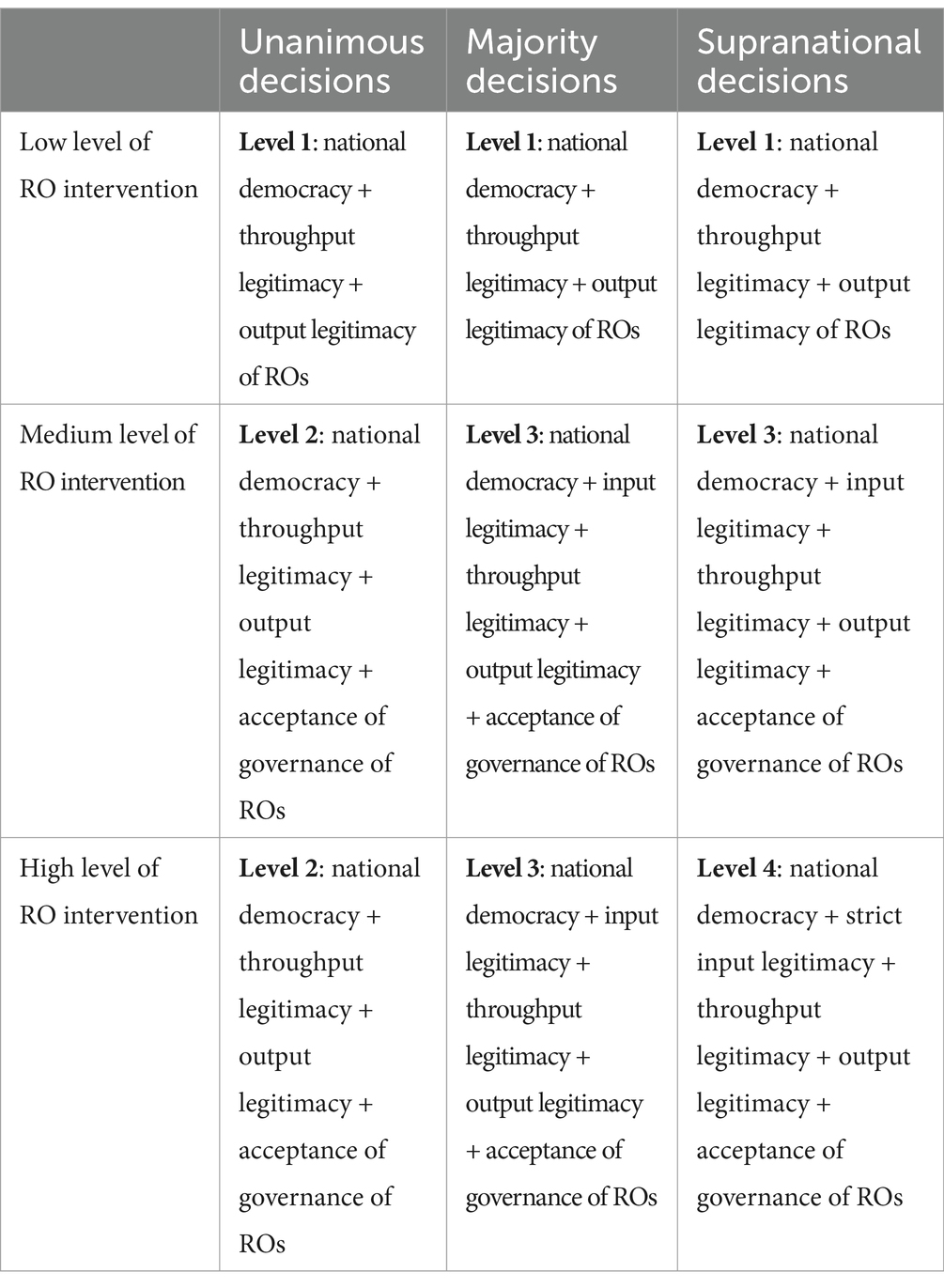

As mentioned above, the requirements for the democratic legitimacy of ROs depend on decision-making in the RO policy field under study and its intervention into nation-state affairs. These can be taken from the decision-making/intervention matrix (see Table 2). This matrix differentiates three types of decision-making and three levels of intervention in nation-state affairs.

For decision-making, these are unanimous intergovernmental decisions, several kinds of majority decisions, and supranational decisions. Why should majority decisions in ROs require higher legitimacy than consensual/unanimous decisions? In German federalism, for example, citizens have choices at the state and federal levels. Even if one’s own state is outvoted in the Bundesrat, the citizen still has the chance to influence the composition of the Bundestag and thus the next federal government, which introduces the laws into the Bundestag, with their electoral decision in the next Bundestag election. In ROs, except in the case of the European Parliament (EP), citizens cannot elect their legislature if their own country has been outvoted several times, and even in the case of the EU, the EP has no right of initiative for new legislative proposals, and this lies with the Commission. However, citizens cannot vote for the Commission. As EU majority decisions can lack accountability, they must meet higher legitimacy requirements than decisions taken unanimously or by consensus. The legitimacy requirement is even higher when decisions are taken supranational, and the legitimacy chain from the citizen to the supranational institution is completely broken unless its decisions must be ratified by the parliament/government or there is a referendum option. In the case of majority decisions, the own government/parliament can vote against a proposal, and if enough other states are against it, the proposed decision could be overturned. Furthermore, it is institutionally foreseen that the elected representatives of the people are involved in the vote, which is not the case with a purely supranational decision.

As described before, the intervention results from the authority of a RO in the policy field under study in combination with the influence of the respective political decisions on legislation, the state budget, and state-determined transfers to citizens or wages for state employees in the member states. In the case of a low intervention level, political decisions of a RO do not influence legislation, the state budget, state-determined transfers to citizens, or wages for state employees in the member states and RO authority does not play a role. At a medium intervention level, political decisions of a RO influence legislation in the member states, but not the state budget, state-determined transfers to citizens, or wages for state employees. Moreover, the RO must have a certain degree of authority in the policy field under study to ensure that the decisions are implemented in the member states. A high degree of intervention exists if the political decisions in a RO influence legislation in the member states and the state budget, state-determined transfers to citizens, or wages for state employees. The RO must also have a certain degree of authority in the policy area under review to implement the decisions in the member states.

To determine the authority of a RO, the existing databases on ROs decision-making by Panke et al. (2020) and on the degree of international authority of IOs/ROs by Hooghe et al. (2017b) and Zürn et al. (2021) were merged. A unified database is available on all IOs/ROs studied by the above authors with their data. Unfortunately, the authority data are not available per IO/RO and policy area but must be calculated for the IO/RO and policy area that will be examined, analogous to the approaches of Hooghe et al. (2017b) and Zürn et al. (2021).

The extent to which political decisions in the RO policy area under study influence legislation in the member states, the state budget, state-determined transfers to citizens, or wages for state employees can be deduced directly from the decisions taken by the RO in the respective policy area.

If one arranges these three gradations of decision-making and intervention in the table, the nine fields make up the decision-making/intervention level matrix (see Table 2). These fields are assigned four levels of democratic legitimacy in ROs where the requirements increase with each level. In the first level, the intervention is low, and the decision-making does not matter as many people in the participating member states will not be aware of the international rule-making. Here, the member state must be subject to democratic governance, and the throughput and output legitimacy of the multilevel governance (MLG) must be guaranteed to speak of democratic legitimacy in ROs.

In the case of unanimous decisions and a medium or high intervention level by a RO, level two is applied. These are the requirements of level one plus the empirical acceptance of the policy of the RO under study because the decisions already affect citizens, and there can be winners and losers. Since the chains of legitimacy are still intact, level two applies even with a high intervention level in member state affairs.

The requirements of level three must be fulfilled in the case of a medium intervention level in combination with majority or supranational decisions or, in the case of a high intervention level, in combination with majority decisions. This corresponds to level two plus input legitimacy. Participation and the basic democratic principles of freedom and equality should be secured in this policy field through control mechanisms.

Level four encompasses the highest requirements for democratic legitimacy in ROs. It applies when there are supranational decisions combined with a far-reaching intervention level in a policy field of a RO. In addition to level three, strict input legitimacy is required, and the member state must have an exit option if the long-term effects are too negative or citizens no longer recognize the decisions of the RO. Strict input legitimacy means that the ROs’ decisions must be ratified by the parliament/government or there is a referendum option.

4 RO democratic legitimacy variables, indicators, and illustration of the future measurement

To explore the democratic legitimacy of ROs regarding the member states of a chosen RO in a selected policy field, these theoretical considerations should be made measurable for level 2 to level 4 of the decision-making/intervention level matrix. At a low intervention level of a RO, the democratic legitimacy of the member states is to be weighted proportionally higher than that of the respective RO (Level 1, Table 2), therefore measuring the democratic legitimacy of the RO in combination with one of its member states results in little added value here. For the remaining levels variables and indicators must be assigned to democratic legitimacy in ROs (see Table 3).

The steps for conducting the future measurement of the democratic legitimacy of ROs in a selected policy field could then be as follows:

Step 1: Selecting a RO and one of its policy fields and, if applicable, an area/agreement to be analyzed within this policy field. For an overview, the new IO/RO database described above can be used.

Step 2: Selecting the RO member states to be analyzed.

Step 3: Determining the RO decision-making in the policy field selected and the intervention in national affairs (some of this information can be drawn from the new IO/RO database).

Step 4: Derive the required level of democratic legitimacy in ROs for the selected case from the decision-making/intervention level matrix.

Step 5: Analyzing and determining the indicators of the selected level of RO democratic legitimacy (level 1, 2, 3, or 4).

Step 6: Graphical representation of the results per nation-state; if appropriate, calculate an index from the individual indicator values.

To make the future assessment of the democratic legitimacy of ROs as simple as possible, indices and measurements that have already been recorded and tested should be used as far as possible. A final application could look like the following illustration using fictitious values:

Example: Determining democratic legitimacy for the crisis management in 2015 to save the Euro (a special case because it was not foreseen by the treaties, but an example of level 4 requirements that so far only exist for highly integrated ROs such as the EU to date).

When saving the Euro (here: the third bailout package for Greece), the decision-making was a mixture between majority decisions and supranational decisions of the Commission, European Central Bank (ECB), Eurogroup, and European Council. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) did not initially participate in the third bailout package for Greece in 2015, so only EU institutions were involved. Since supranational decisions were also made, the legitimacy requirements for supranational decisions apply. The intervention was also high (Zeller, 2018, 86–88), so the fourth level of the decision-making/intervention level matrix is used. The highest demands are made on the democratic legitimacy of ROs, and all variables must be determined. Since Greece, unlike Germany, was subject to the provisions of the European Commission and the ECB, the fictive values for the democratic legitimacy of ROs are significantly lower for Greece than for Germany (see Figure 3) although Germany and Greece were exposed to the same level of intervention during the crisis. The democratic legitimacy of a RO from the perspective of a member state can then be read directly from the graphical illustration: the larger the area of the graph, the higher the democratic legitimacy. The fact that such differences can be made visible is the strength of this new analytical framework.

Figure 3. RO democratic legitimacy for saving the Euro in Greece and Germany. Source: Developed by the author.

In this context, the democratic legitimacy of ROs is not considered static but dynamic and can change as soon as one of its variables changes. If, for example, the outcome in Member State X has improved after a few years and thus the acceptance for the RO under study increases, the democratic legitimacy for this analysis unit will also improve.

5 Discussion

As ROs are increasingly questioned in individual member states, stressing international governance, the question of the legitimacy of ROs increases. To date, however, no measurement tool allows for a systematic comparison of the democratic legitimacy of individual member states of ROs. This contribution provides a means of measuring democratic legitimacy in different ROs for member states concerning a selected policy field.

Therefore, a theoretical model of democratic legitimacy within ROs was developed that, for the first time, also considers the national level. The national level is relevant to clarify why ROs are questioned in certain member states and not in others. To achieve this aim, determining factors like power, authority, and legitimacy in ROs and concepts of democratic legitimacy were discussed. The new concept considers besides the nation-state level also the different requirements of democratic legitimacy of ROs depending on the decision-making and RO intervention in nation-state affairs. It is based on input, throughput, and output legitimacy and the empirical acceptance of a RO and its processes, and the concept of democracy contained in input legitimacy is oriented towards the normative core of democracy. Also, the steps for future measurements of the democratic legitimacy of ROs were presented, variables and indicators for the requirements were defined, and an illustration with fictitious values was given. The illustration with the fictitious data concerning the EU in the Euro crisis showed the most complex case (level 4), so that it should be possible to apply the analytical framework to the ROs (and their member states) mentioned in Panke and Starkmann (2019) without any problems.

It may be the case that not all indicators are already covered by data, meaning that separate data may have to be collected or indicators may have to be varied. This has to be verified in an initial application. However, this relatively superficial comparative measurement with standards brought from outside can provide initial hints of legitimacy problems in individual member states of a RO. In order to provide a comprehensive picture of the democratic legitimacy of a RO from the perspective of a member state, I recommend a more in-depth analysis based on standards generated by the citizens of the respective member states (Wiesner and Harfst, 2019, 27–28). If an assessment of the legitimacy of a RO in a specific policy field across all member states is desired, the measurement should be carried out for each individual member state. Then, an average value for the RO could be determined, for example. A subsequent application to IO with a certain depth of intervention, such as the IMF, would also be conceivable. In this case, the concept would have to be modified somewhat with regard to MLG.

How can the data be interpreted? This measurement is intended to examine and compare the democratic legitimacy of RO member states in selected policy fields and thus their potential for politicization and contestation. This applies to ‘normal’ times or times of crises. If the democratic legitimacy of a member state of a RO is very low in the policy area under investigation, this could mean a higher risk of politicization and contestation in this area. Depending on the elements and variables with low legitimacy, specific legitimation strategies could then be developed. Furthermore, this measurement creates a better understanding of the democratic legitimacy of ROs and contributes to the discussion of the democratic legitimacy of ROs.

In addition, future measurements can be used to create a basis for further analyses: As Brexit is not the only case where a member state has left a RO, it would be interesting to find out why states do so. Is there, for example, a link between the low democratic legitimacy of certain ROs in some member states and the rise of populist parties within these states?

What determines the potential for delegitimating processes of ROs in member states? Is it the democratic legitimacy in total, or does it depend on the degree of authority exercised or domestic political interference by the RO or the output/outcome?

How did ROs respond to which types of legitimacy deficits? Did legitimation strategies influence the democratic legitimacy of the RO?

Subsequently, the analysis results can be used by RO leaders to improve their democratic legitimacy through reforms and preserve democracy in their member states, if present.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^An overview of different integration theories with reference to the EU can be found in Hans-Jürgen Bieling and Marika Lerch (eds.) (2012).

References

Abromeit, H. (2002). Wozu braucht man Demokratie? Die postnationale Herausforderung der Demokratietheorie [Why do we need Democracy? The Postnational Challenge of Democratic Theory]. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Abromeit, H., and Stoiber, M. (2007). “Criteria of democratic legitimacy” in Legitimacy in an age of global politics. eds. A. Hurrelmann, S. Schneider, and J. Steffek (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 35–56.

Aristotle. (2003). Politik [Politics]. Translated and edited by F. F. Schwarz. Stuttgart: Philipp Reclam Jun.

Armingeon, K., Guthmann, K., and Weistanner, D. (2015). Wie der Euro Europa spaltet. Die Krise der gemeinsamen Währung und die Entfremdung von der Demokratie in der Europäischen Union. [How the Euro Divides Europe. The Crisis of the Common Currency and the Alienation from Democracy in the European Union]. PVS 56, 506–531. doi: 10.5771/0032-3470-2015-3-506

Benz, A. (2010). Blockiert durch Komplexität? Demokratie in Mehrebenensystemen föderaler and transnationaler Politik. [Blocked by Complexity? Democracy in Multilevel Systems of Federal and Transnational Politics]. Vorgänge 2, 64–72.

Benz, A. (2018). “Legitimität und Autorität in der globalen Ordnung [Legitimacy and Authority in the Global Order]” in Ordnung und Regieren in der Weltgesellschaft [Order and Governance in Global Society]. eds. M. Albert, N. Deitelhoff, and G. Hellmann (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 329–352.

Bodansky, D. (1999). The legitimacy of international governance: a coming challenge for international environment law? Am. J. Int. Law 93, 596–624. doi: 10.2307/2555262

Buchanan, A., and Keohane, R. O. (2006). The legitimacy of global governance institutions. Ethics Int. Aff. 20, 405–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7093.2006.00043.x

Carstensen, M. B., and Schmidt, V. A. (2018). Ideational power and pathways to legitimation in the euro crisis. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 25, 753–778. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2018.1512892

Christensen, T., Rykkja, L. H., and Lægreid, P. (2016). Organizing for crisis management: building governance capacity and legitimacy. Public Adm. Rev. 76, 887–897. doi: 10.1111/puar.12558

Dahl, R. A. (1994). A democratic dilemma: system effectiveness versus citizen participation. Polit. Sci. Quart. 109, 23–34. doi: 10.2307/2151659

Dingwerth, K., Schmidtke, H., and Weise, T. (2019). The rise of democratic legitimation: why international organizations speak the language of democracy. Eur. J. Int. Rel. 26, 714–741. doi: 10.1177/1354066119882488

European Parliament (EP). (2014). Report on the enquiry on the role and operations of the Troika (ECB, Commission and IMF) with regard to the euro area programme countries (2013/2277(INI)). DOK A7-0149/2014, 28.02.2014. Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs.

Farrell, H., and Newman, A. L. (2021). “Weaponized interdependence. How global economic net-works shape state coercion” in The Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence. eds. D. W. Drezner, H. Farrell, and A. L. Newman (Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution), 19–66.

Fuchs, D. (2002). Das Demokratiedefizit der Europäischen Union und die politische integration Europas: Eine Analyse der Einstellungen der Bürger in Westeuropa [The Democratic Deficit of the European Union and European Political Integration: An Analysis of Citizens’ Attitudes in Western Europe]. Discussion paper FS III 02–204. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Habermas, J. (1976). Legitimation Problems in the Modern State. Politische Vierteljahresschrift (PVS) 7, 39–61. doi: 10.1007/978-3-322-88717-7_2

Habermas, J. (1992). Faktizität und Geltung: Beiträge zur Diskurstheorie des Rechts und des demokratischen Rechtsstaats Between Facts and Norms. Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Frankfurt a Main: Suhrkamp.

Habermas, J. (1998). Die postnationale Konstellation. Politische Essays [The Postnational Constellation. Political Essays]. Frankfurt a Main: Suhrkamp.

Hooghe, L., Lenz, T., and Marks, G. (2019a). Contested world order: the delegitimation of international governance. Rev. Int. Organ. 14, 731–743. doi: 10.1007/s11558-018-9334-3

Hooghe, L., Lenz, T., and Marks, G. (2019b). A Theory of International Organization. A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Vol. IV. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Lenz, T., Bezuijen, J., Ceka, B., and Derderyan, S. (2017a). Measuring International Authority. A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, Vol. III. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Lenz, T., Bezuijen, J., Ceka, B., and Derderyan, S. (2017b). Measuring International Authority. MIA-Authority. Annual aggregate scores for delegation and pooling for each IO. Available at: https://garymarks.web.unc.edu/data/international-authority/ (Accessed May 27, 2024).

Hutter, S., and Kriesi, H. (2019). Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 26, 996–1017. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2019.1619801

Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. (2017). “Legitimacy” in Handbook on Theories of Governance. eds. C. Ansell and J. Torfing (Cheltenham/Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing), 197–204.

Keohane, R. O. (1984). After Hegemony. Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kerwer, D. (2016). “Ein Imperium im Wandel? Wie die Eurokrise die Europäische Union verändert [An Empire in Transition? How the Euro Crisis is Changing the European Union]” in Europäische Staatlichkeit. Zwischen Krise und Integration [European Statehood. Between Crisis and Integration]. eds. H.-J. Bieling and M. G. Hüttmann (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 71–89.

Kriesi, H. (2013). Democratic legitimacy: is there a legitimacy crisis in contemporary politics? PVS 54, 609–638. doi: 10.5771/0032-3470-2013-4-609

Lauth, H.-J. (2019). “Legitimacy and legitimation” in The SAGE Handbook of Political Science. eds. B. Badie, D. Berg-Schlosser, and L. Morlino (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 841–459.

Majone, G. (1998). Europe’s 'democratic deficit': the question of standards. Eur. Law J. 4, 5–28. doi: 10.1111/1468-0386.00040

Merkel, W. (2015). “Die Herausforderungen der Demokratie [The Challenges of Democracy]” in Demokratie und Krise. Zum schwierigen Verhältnis von Theorie und Empirie [Democracy and Crisis. On the Difficult Relationship Between Theory and Empiricism]. ed. W. Merkel (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 7–42.

Moravcsik, A. (2002). Reassessing legitimacy in the European Union. J. Common Mark. Stud. 40, 603–624. doi: 10.1111/1468-5965.00390

Moravcsik, A. (2004). Is there a “democratic deficit” in world politics? A framework for analysis. Gov. Oppos. 39, 336–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00126.x

Moschella, M., Pinto, L., and Diodati, N. M. (2020). Let's speak more? How the ECB responds to public contestation. J. Eur. Publ. Policy 27, 400–418. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1712457

Neyer, J. (2013). Globale Demokratie. Eine zeitgemäße Einführung in die Internationalen Beziehungen [Global Democracy. A Contemporary Introduction to International Relations]. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Norris, P., and Inglehart, R. (2019). Culturals Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Panke, D., Stapel, S., and Starkmann, A. (2020). Comparing Regional Organizations. Global Dynamics and Regional Particularities. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Panke, D., and Starkmann, A. (2019). ROCO II 14 11 2019.tab. Regional Organizations’ Competencies (ROCO), Harvard Dataverse, V1, UNF:6:EBnC4CTA8SezzL0f6sNujg== [fileUNF]. doi: 10.7910/DVN/UBXZHC/OJTTZH

Panke, D. (2020). Compensating for limitations in domestic output performance? Member state delegation of policy competencies to regional international organizations.. International Relations. 1–36. doi: 10.1177/0047117820970320

Pollitt, C., and Buchaert, G. (2011). Public management reform. A comparative analysis-new public management, Goverance, and the neo-Weberian state. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Puntscher Riekmann, S. (2016). “Geld und Souveränität. Zur Transformation der Europäischen Union und der Mitgliedstaaten Durch die Finanz- und Fiskalkrise (2008-2013) [Money and Sovereignty. On the Transformation of the European Union and the Member States by the Financial and Fiscal Crisis (2008-2013)]” in Europäische Staatlichkeit. Zwischen Krise und Integration [European Statehood. Between Crisis and Integration]. eds. H.-J. Bieling and M. G. Hüttmann (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 203–221.

Rauh, C., and Zürn, M. (2019). Authority, politicization, and alternative justifications: endogenous legitimation dynamics in global economic governance. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 27, 583–611. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2019.1650796

Reinalda, B. (2007). “The question of input, control and output legitimacy in economic RIOs,” in Closing or widening the gap? Legitimacy and democracy in regional integration organizations, eds. A. Ribeiro Hoffmann and A. Vleutenvan der, 49–82. Aldershot, Burlington: Ashgate.

Rittberger, B., and Schroeder, P. (2016). “The legitimacy of regional institutions” in The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism. eds. T. A. Börzel and T. Risse (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 579–599.

Rodrik, D. (2011). Das Globalisierungs-Paradox: die Demokratie und die Zukunft der Weltwirtschaft The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of Global Economy. München: Beck.

Sandholtz, W., and Stone Sweet, A. (1998). European integration and supranational governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schäfer, A., and Zürn, M. (2021). Die demokratische Regression [Democratic Regression]. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Scharpf, F. W. (1999). Regieren in Europa. Effektiv und demokratisch? [Governance in Europe. Effective and Democratic?]. Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag.

Scharpf, F. W. (2002). Regieren im europäischen Mehrebenensystem – Ansätze zu einer Theorie. Governance in the European Multilevel System - Approaches to a Theory. Leviathan 30, 65–92. doi: 10.1007/s11578-002-0011-8

Scharpf, F. W. (2009). Legitimität im europäischen Mehrebenensystem. [Legitimacy in the European Multilevel System]. Leviathan 2, 244–280. doi: 10.5771/9783845220376-297

Scharpf, F. W. (2014). “Die Finanzkrise als Krise der ökonomischen und rechtlichen Überintegration The Financial Crisis as a Crisis of Economic and Legal Over-Integration” in Grenzen der europäischen Integration. Herausforderungen für Recht und Politik Limits to European Integration. Challenges for Law and Politics. eds. C. Franzius, F. C. Mayer, and J. Neyer (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft), 51–60.

Schmidt, M. G. (2019). Demokratietheorien. Eine Einführung [Theories of Democracy. An Introduction]. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Schmidt, S., and Schünemann, W. J. (2013). Europäische Union. Eine Einführung [European Union. An Introduction]. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Schmidt, V. A. (2006). Democracy in Europe. The EU and National Polities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schmidt, V. A. (2013). Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: input, output and ‘throughput’. Polit. Stud. 61, 2–22. doi: doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x

Scott, W. R., and Davis, G. F. (2016). Organizations and Organizing. Rational, Natural, and Open System Perspectives. London/New York: Routledge.

Sommerer, T., Squatrito, T., Tallberg, J., and Lundgren, M. (2022). Decision-making in international organizations: institutional design and performance. Rev. Int. Organ. 17, 815–845. doi: 10.1007/s11558-021-09445-x

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 571–610. doi: 10.2307/258788

Tallberg, J., and Zürn, M. (2019). The legitimacy of international organizations: introduction and framework. Rev. Int. Organ. 14, 581–606. doi: 10.1007/s11558-018-9330-7

Tholen, B. (2007). “RIOs, Legitimacy and Democracy. A conceptual Clarification,” in Closing or widening the gap? Legitimacy and democracy in regional integration organizations. eds. A. Ribeiro Hoffmann and A. Vleutenvan der (Aldershot, Burlington: Ashgate), 17–31.

Trein, P., Thomann, E., and Maggetti, M. (2019). Integration, functional differentiation and problem-solving in multilevel governance. Public Administration 97, 2, 339–354. doi: 10.1111/padm.12595

van der Vleuten, A., and Ribeiro Hoffmann, A. (2007) “Legitimacy, democracy and RIOs: where is the gap?,” in Closing or widening the gap? Legitmacy and democracy in regional integration organizations, eds. A. Ribeiro Hoffmann and A. Vleutenvan der, (Aldershot, Burlington: Ashgate) 3–13.

Voelsen, D., and Schettler, L. V. (2019). International political authority: on the meaning and scope of justified hierarchy in international relations. Int. Relat. 33, 540–562. doi: 10.1177/0047117819856396

Voigt, R. (2013). Alternativlose Politik? Zukunft des Staates – Zukunft der Demokratie [Politics without Alternatives? Future of the State - Future of Democracy]. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

von Engelhardt, B. (2016). Die Welthandelsorganisation (WTO) und demokratische Legitimität. Globale Ordnung zur Regelung wirtschaftlicher Interdependenzen und ihre Auswirkungen auf territorial organisierte Demokratie [The World Trade Organization (WTO) and Democratic Legitimacy]. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Weber, M. (1922). Grundriss der Sozialökonomik. III. Abteilung. Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft [Outline of Social Economics]. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck).

Westle, B. (1989). Politische Legitimität – Theorien, Konzepte, Empirische Befunde [Political Legitimacy - Theories, Concepts, Empirical Findings]. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlags-Gesellschaft.

Wiesner, C., and Harfst, P. (2019). “Legitimität als "essentially contested concept" [Legitimacy as ‘essentially contested concept’]” in Legitimität und Legitimation. Vergleichende Perspektiven [Legitimacy and Legitimation. Comparative Perspectives]. eds. C. Wiesner and P. Harfst (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 11–32.