95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 15 March 2024

Sec. Political Economy

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1351285

While there is no clear answer to the overall impact of Official Development Assistance (ODA) on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), it has been pointed out that Japanese ODA promotes its FDI. However, the mechanism of ODA’s impact on FDI has not been fully examined at the micro level, as most previous studies have used macro-level data. Therefore, this study examines the impact of ODA on FDI at the micro level in India, where an increase in ODA and FDI from Japan have been observed in recent years. Interviews were conducted with three Japanese firms and five Japanese public organizations, while questionnaires were administered to 33 Japanese firms. The results reveal that ODA effectively promotes FDI, albeit to a lesser extent than other FDI determinants. Economic infrastructure development through ODA, the expectations of such development, and the reception of orders for ODA Loan projects, promote FDI. Furthermore, the role of public institutions, including providing information to firms and acting as intermediaries with the government, is more effective in promoting FDI than ODA. Based on these results, in light of the OLI theory, it is suggested that a possible mechanism is that Japanese ODA promotes FDI by enhancing the “Ownership Specific Advantages” of Japanese firms and the “Location Advantages” of recipient countries. The novelty of this study lies in its clarification of the mechanism through which ODA promotes FDI from a micro-perspective, as revealed by a questionnaire survey conducted among firms. The FDI-promoting effects of ODA for economic infrastructure and ODA Loan suggested in this study not only contributes to the academic community but also have important implications for ODA policymakers.

Official Development Assistance (ODA) refers to government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries (OECD, 2023a). The ODA Charter, formulated in 1992 and revised in 2003 and 2015, defines Japan’s ODA policy. It has consistently identified Asia, a major investment destination among recipient countries, as a priority region, and has adopted a policy promoting public-private partnership (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, 1992, 2004, 2015).

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) refers to a type of cross-border investment wherein an investor from one economy establishes a lasting interest and significant influence over a company in another economy. It is also characterized by ownership of more than 10% of the voting rights of a company in one economy by investors from another economy. FDI is an important channel for technology transfer between countries and an important driver of economic development (OECD, 2024). FDI has been considered to influence economic growth directly and indirectly over the past few decades. Almfraji and Almsafir (2014) reviewed numerous studies on the relationship between FDI and economic growth from 1994 to 2012 and found that FDI positively affects economic growth in recipient countries.

Although the overall impact of ODA on FDI lacks a definitive answer (Ono and Sekiyama, 2022, 2023), Kimura and Todo (2010) and Kang et al. (2011) highlight that Japanese ODA promotes FDI. The mechanism of the impact of ODA on FDI has not been sufficiently examined at the micro level, as most previous studies have used macro-level data. Therefore, this study seeks to identify the impact of Japanese ODA on FDI by Japanese firms in India, Japan’s largest recipient of ODA disbursements over the past two decades. The identification of ODA types that promote FDI is not only an academic contribution but also useful for informing policymaking.

In the study of outward foreign direct investment, the OLI theory developed by Dunning (1979) has long been referred to as the leading theoretical framework. He identified three determinants of FDI: (i) Ownership Specific Advantages, (ii) Location Specific Advantages, and (iii) Internalization Advantages. Ownership Specific Advantages involve the advantages that a company possesses, such as its unique competitiveness. The Location Specific Advantage is the advantage that the country where the investment is made has, such as resources, social and economic infrastructure, market attractiveness, and political stability. Internalization Advantages are the advantage of doing business abroad through internalization, meaning FDI, rather than exporting or licensing.

Research on the impact of ODA on FDI is relatively novel, beginning with Karakaplan et al. (2005). Studies have gathered data on the impact of ODA on FDI, but a definitive answer to this question is lacking. While many empirical analyses have found negative results regarding the general effect of ODA on promoting FDI (Harms and Lutz, 2006; Kimura and Todo, 2010; Kang et al., 2011; Liao et al., 2020), as shown below, some previous studies have pointed out that Japanese ODA is effective in promoting FDI.

The preceding studies on the impact of ODA on FDI can be organized in light of the OLI theory as follows: an empirical study that suggests that ODA has promoted FDI by enhancing “Ownership Specific Advantages” is the study by Kimura and Todo (2010), who noted the “vanguard effect.” Kimura and Todo (2010) found that Japanese ODA has a “vanguard effect” that promotes Japanese FDI in recipient countries. They attributed the vanguard effect to the Japanese government’s intentional use of ODA to promote FDI and the close cooperation between the public and private sectors regarding ODA. Specifically, it is considered that ODA promotes FDI by enhancing “Ownership Specific Advantages,” such as transferring knowledge, skills, and institutions specific to the donor country to the recipient country. Similarly, Kang et al. (2011) demonstrated that Korea’s ODA, with aid practices similar to those of Japan, has the effect of promoting FDI in their country. Additionally, Nishitateno (2023) found that 17% of the total number of overseas infrastructure projects contracted by Japanese firms between 1970 and 2020 can be attributed to Japanese ODA, indicating that ODA helps firms from donor countries win infrastructure projects in recipient countries.

Regarding “Location Specific Advantages,” Donaubauer et al. (2016) found that ODA for economic infrastructure has two effects: an “indirect effect,” in which ODA promotes FDI by developing economic infrastructure, and a “direct effect,” in which ODA creates expectations among investors for infrastructure development and promotes FDI. The effect of ODA for economic infrastructure can be summarized as the promotion of FDI by improving the “Location Specific Advantages” of the recipient country. Lee and Ries (2016) also demonstrated that ODA for economic infrastructure facilitates FDI from donor to recipient countries. Regarding the effect of Japanese ODA on FDI, Blaise (2005) analyzed China using state-level data from 1980 to 1999 and found that Japanese ODA had the effect of promoting FDI. They also considered that improvements in economic infrastructure led to FDI promotion because Japanese ODA in China concentrated on economic infrastructure.

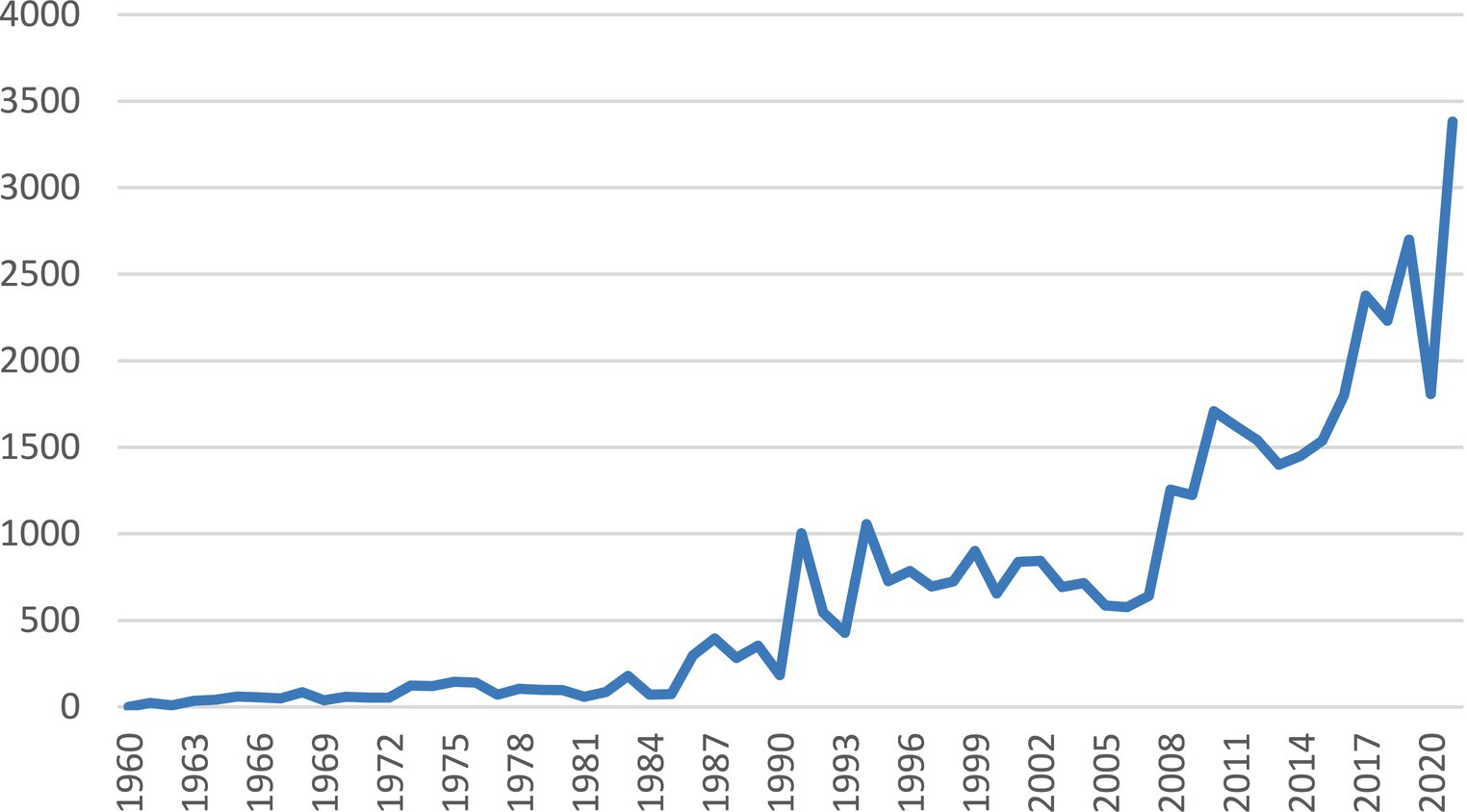

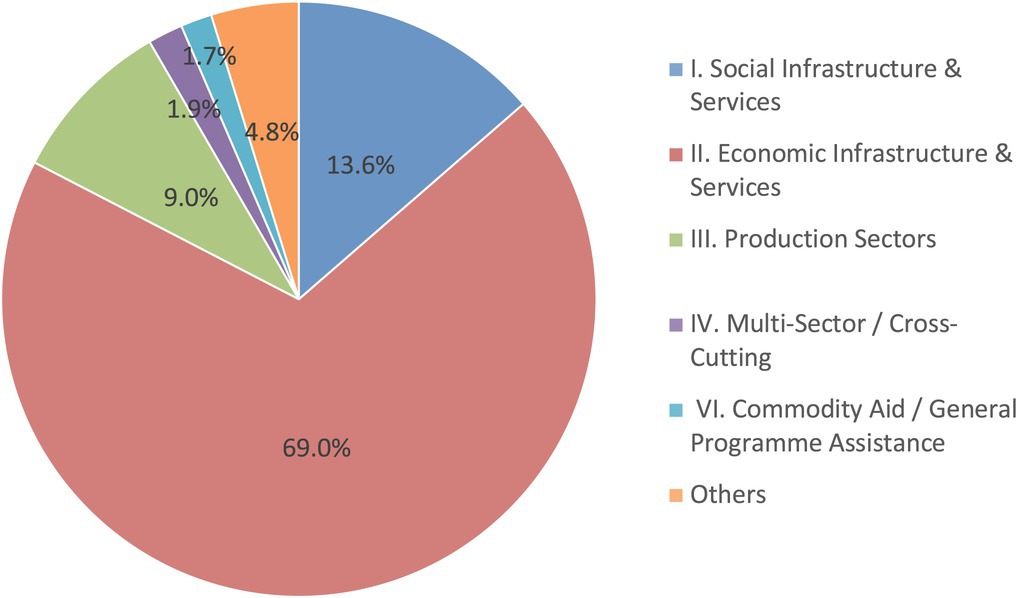

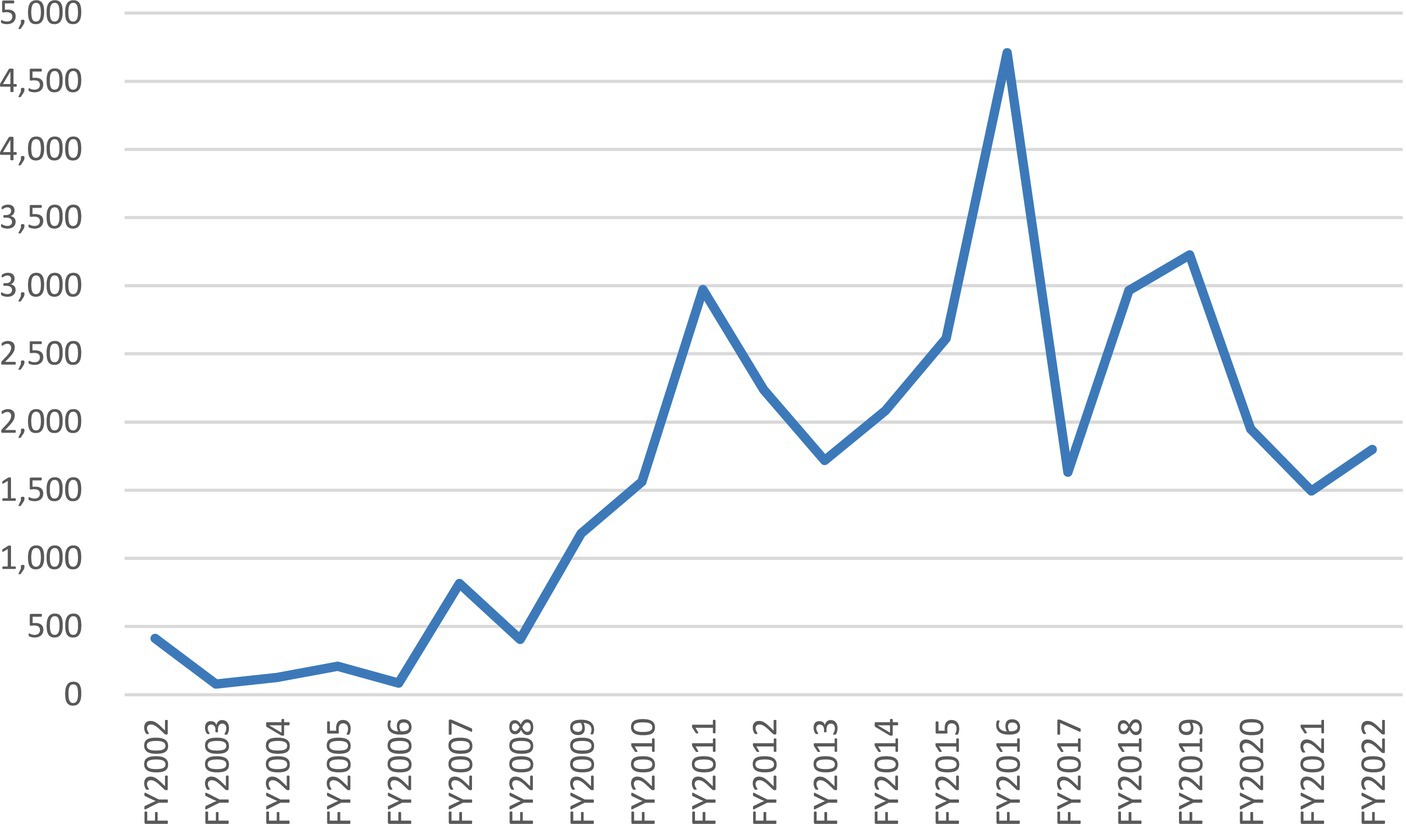

This study focuses on India, which has been Japan’s largest spending destination over the past two decades (2002–2021), as shown in Table 1. ODA from Japan to India has gradually increased since the late 1980s and rapidly increased since the late 2000s, as shown in Figure 1. A sectoral breakdown of Japan’s ODA to India is shown in Figure 2, with economic infrastructure ODA accounting for approximately 70% of the total. FDI from Japan to India has been increasing since the late 2000s, as shown in Figure 3. While there is active research on FDI in India (Beladi et al., 2016; Nayyar and Mukherjee, 2020; Nepal et al., 2021; Friedt and Toner-Rodgers, 2022; Chawla and Kumar, 2023; Kumari and Ramachandran, 2023), the impact of ODA on FDI is not yet available to the best of our knowledge.

Figure 1. Official development assistance (ODA) disbursements from Japan to India (million USD). Source: OECD.Stat.

Figure 2. Official development assistance disbursements from Japan to India by sector (2002–2021). Source: OECD.Stat.

Figure 3. Foreign direct investment inflow from Japan to India (million USD). Source: Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India (2023).

As discussed above, while the macro-level effects of Japanese ODA in promoting FDI have been clarified, the specific mechanisms through which Japanese ODA promotes FDI at the micro level remain unclear. Therefore, this study examines how Japanese ODA has promoted FDI in India—where ODA and FDI from Japan have been increasing in recent years—employing an interview and questionnaire survey targeting firms in light of the OLI theory.

To identify the specific mechanisms through which Japanese ODA facilitates FDI, this study focuses on India, a significant beneficiary of Japanese ODA over the past two decades (OECD, 2023b) and a major recipient of Japanese FDI. We conducted a survey targeting Japanese companies operating in India and experts in ODA and FDI. There are approximately 1,400 Japanese companies in India (Embassy of Japan in India, 2023).

To formulate a hypothesis, we conducted an interview survey first. In the interview survey, questions were asked about the relationship between ODA and FDI in India. From May 22 to May 25, 2023, interviews were conducted in Delhi in five public institutions and two Japanese companies; one interview was conducted online.

In addition to interviewing experts and Japanese companies, we invited 400 companies to participate in a questionnaire survey through their respective company websites. Companies were asked about their investment behavior. Based on the interview results and previous studies, hypotheses regarding the effects of ODA on FDI were formulated and tested through a questionnaire survey. The questionnaire was distributed online.1 The following hypotheses 1–5 were tested for ODA and hypothesis 6 was tested for factors other than ODA. Consent to participate in the questionnaire survey was obtained from the participants via an online form.

H1: ODA for economic infrastructure promotes FDI:

Donaubauer et al. (2016) demonstrated that ODA for economic infrastructure pro-motes FDI both indirectly and directly. In the OLI theory framework, ODA for economic infrastructure is thought to promote FDI by increasing “Location Specific Advantages.” Therefore, the questionnaire survey examined the indirect effect of ODA, whereby ODA promotes FDI by improving economic infra-structure. Additionally, it investigated the direct effect of ODA, where the expectation that ODA would improve economic infrastructure facilitates FDI.

H2: Receiving ODA project orders promotes FDI:

The interview survey revealed cases of Japanese companies entering India to participate in ODA projects. Given the OLI theory framework, ODA is expected to promote FDI by increasing the “Ownership Specific Advantages” of firms from donor countries, for example, by making it easier for firms from donor countries to obtain information about ODA projects. Therefore, the questionnaire survey examined the effect of receiving ODA projects on FDI promotion.

H3: ODA for human resource development that builds bridges between developing countries and Japan promotes FDI:

There is an example of an internship done during a study abroad program through ODA that contributed to the development of the company’s business in the intern’s home country (JICA, 2022). Viewed within the framework of OLI theory, ODA is considered to enhance the “Ownership Specific Advantages “of firms from donor countries and promote FDI by ensuring that firms from donor countries recruit human resources familiar with a developing country through ODA. Therefore, the questionnaire survey aimed to verify whether FDI is facilitated by human resources fostered through ODA, which serves as a bridge between developing countries and Japan.

H4: ODA for human capital development promotes FDI in developing countries:

Noorbakhsh et al. (2001) demonstrated that the quality of human capital promotes FDI in developing countries. Considering the OLI theory, ODA for human capital is thought to promote FDI by increasing “Location Specific Advantages.” Therefore, the questionnaire survey examined whether ODA promotes FDI by improving the quality of human capital in developing countries.

H5: ODA for investment environment development promotes FDI:

Contractor et al. (2020) demonstrated that the investment environment, such as the strength of contract enforcement in the recipient country, is a determinant of FDI. Within the framework of OLI theory, ODA for investment environment development is thought to promote FDI by increasing “Location Specific Advantages.” Therefore, the questionnaire survey tested whether FDI is promoted by improving the investment environment through ODA.

H6: Factors other than ODA promote FDI:

The questionnaire tested various factors, such as market size, labor cost, labor quality, trade openness, infrastructure, taxation, economic agglomeration, geographic location, and country risk, that have been identified as major factors promoting FDI (Fukao and Hoon, 1996; Arben et al., 2018). Further, the questionnaire examined factors such as market growth potential, procedures, religion and culture, language, international political climate, and information provided by public institutions, which were revealed during the interview stage.

While some public organizations expressed negative opinions about the impact of ODA on FDI, stating, “I have the impression that ODA and FDI are not necessarily linked in India,” and “not many companies are utilizing ODA,” others supported the infra-structure effect, stating, “there may be a long-term effect from infrastructure development.” The Japanese firms generally expressed negative opinions about the FDI-promoting effects of ODA. For example, they stated, “there may not be much benefit to Japanese companies from ODA,” “it is possible that ODA is increasing because Japanese FDI is increasing,” “large amounts of ODA in India seem to have strong political connotations,” and “Japan used to be price competitive, but now it is difficult to secure ODA projects.” However, there were some cases in which ODA had an impact on FDI, as evident by statements such as “we entered the Indian market because one of our targets was to secure ODA Loan orders.”

Only 33 of the 400 Japanese companies that requested the survey responded, as many companies had a policy of not responding to surveys. The responses reflect the opinions of individuals, not the views of public institutions or companies. Questions on individual firms were adjusted based on the number of Japanese firms in India in the respective industry to which the responding firms belong (33 firms). Question (1) was rated on a scale of −5 to 5 because some items could have a negative effect on FDI decisions, while question (2) was rated on a scale of 0 to 10 based on the assumption that public institutional support would have at least no negative effect.

Each firm rated, on a scale of −5 to 5, the impact of each of the 19 factors on its decision to consider making FDI in India. A score of −5 indicates that the factor contributed significantly to the decision to “not make FDI,” a score of 0 or +/− 0 indicates that the factor had no effect on the decision to “make FDI,” and a score of 5 indicates that the factor contributed significantly to the decision to “make FDI.” The results are shown in Table 2. The results for all factors are positive. The factor that contributed the most to the decision to “make FDI” was “market growth potential,” followed by “market size” and “labor cost.” Public support is ranked 11th and 14th out of 19 factors. The contribution of “information support or mediation by public institutions” exceeds that of “receiving project orders or financial support from public institutions,” which includes ODA.

Each firm rated, on a scale of 0 to 10, the impact of each of the following 14 public institutional assistance factors on its decision to engage in FDI in India. A score of 0 indicates no impact on the decision to “make FDI,” 5 suggests a slight contribution to the decision, and 10 denotes a significant contribution to the decision to “make FDI.” The results are shown in Table 3. The JICA item represents ODA. The top two factors con-tributing to the decision to “make FDI” were “information provision and business matching by JETRO” and “offers and introductions by the Japanese government to the partner government,” which are support unrelated to ODA. Among ODA indicators, the top factors are economic infrastructure following the completion of construction, expectations for the completion of economic infrastructure, and ODA Loan project orders.

Interviews and questionnaire surveys conducted with firms and experts revealed that all items tested are positive determinants of FDI, albeit with varying contributions. Thus, Hypotheses 1–6 suggested to be valid. Financial support from public institutions, including ODA, was found to positively affect FDI, while its contribution was smaller than that of other FDI determinants. Notably, the contribution of “information or intermediary support” from public sector outweights that of ODA. Among ODA factors, support for economic infrastructure and securing ODA Loan projects emerge as the most significant contributors.

The questionnaire survey revealed that the receiving of orders for ODA Loan projects affects firms even more than receiving orders for ODA Grant projects. This finding may be attributed to some firms only bidding for ODA Loan projects, which are larger in project size than ODA Grant projects, as mentioned by two out of three firms in the interview survey. The interview survey revealed examples of companies that entered India with the purpose of securing ODA project orders, and in order to make their prices competitive, FDI was implemented in the form of establishing joint ventures with local companies.

The results support the indirect and direct effects economic infrastructure aid, as noted by Donaubauer et al. (2016). The findings also suggest that the FDI-promoting effect of ODA Loan, highlighted by Ono and Sekiyama (2023), is not solely attributed to the effect of economic infrastructure. Rather, it may also result from the possibility that FDI is promoted by the receipt of ODA Loan projects. Furthermore, the results suggest that the role of public institutions in providing information to firms and serving as intermediaries with recipient countries is more effective in promoting FDI than the effect of ODA on FDI, as discussed in previous studies.

Based on these results, and aligning with the OLI theory, the following mechanisms through which ODA affects FDI are discussed. First, Japanese ODA Loan projects may enhance the “Ownership Specific Advantages” of Japanese firms. Firms from donor countries may have easier access to information on ODA projects than firms from other countries. Additionally, donor governments may have an incentive to design ODA projects utilizing their technologies to benefit firms of donor countries. Japan, for instance, offers a type of ODA Loan known as Special Terms for Economic Partnership (STEP) to utilize Japanese technologies (JICA, n.d.). Through this mechanism, Japan’s ODA Loan projects in India may bolster the “Ownership Specific Advantages” of Japanese firms and facilitate their FDI in India. In support of this, Nishitateno (2023) demonstrates that the Japanese ODA facilitates the awarding of infrastructure projects in recipient countries to Japanese firms.

Second, Japanese ODA Loan projects may enhance the “Location Advantages” of recipient countries. These projects improve the business environment, including economic infrastructure in the recipient country. Moreover, when firms from donor countries advance into a recipient country owing to “Ownership Specific Advantages,” it may increase the concentration of their business customers and partners from the donor country in the recipient country. Thus, the concentration of business customers and improved business environment may increase “Location Advantage,” particularly for Japanese firms through ODA Loan projects. This subsequently, may further promote FDI in India by Japanese firms. One limitation of this study is that while the questionnaire survey was distributed to randomly selected Japanese firms in India, firms with close ties to ODA responded actively. This may have introduced biased our results.

This study examined the impact of Japanese ODA on Japanese FDI in India, where an increase in Japanese ODA and FDI have been observed. Interview surveys were conducted with five public organizations and three Japanese firms. Additionally, questionnaire surveys were administered, yielding responses from 33 Japanese firms. The results of the survey verified the effectiveness of ODA in promoting FDI. On the other hand, it was found that the FDI-promoting effect of ODA was lower than that of other FDI determinants. Among ODA factors, the direct and indirect effects of ODA on economic infrastructure and the effect of securing paid financial assistance project orders were identified as FDI-promoting effects. Furthermore, the results suggest that the role of public institutions in providing information to firms and serving as intermediaries with recipient countries is more effective in promoting FDI than the effect of ODA on FDI.

The novelty of this study lies in its clarification of the mechanism by which ODA promotes FDI at the micro level, through survey questionnaires and interviews with firms. This study not only contributes to the academic community, but also provides important suggestions for policymakers in the field of ODA.

Future research, including case studies of firms, is expected to further clarify the details of the mechanisms through which ODA promotes FDI.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of privacy reasons. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to SO, ono.saori.86c@kyoto-u.jp.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because this study does not deal with data on the body, mind, behavior, or environment of individuals. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

SO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. 22KF0176) and JST SPRING (Grant No. JPMJSP2110).

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Almfraji, M. A., and Almsafir, M. K. (2014). Foreign direct investment and economic growth literature review from 1994 to 2012. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 129, 206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.668

Arben, S., Skender, A., and Hysen, I. (2018). A review of empirical studies on FDI determinants. Balt. J. Real Estate Econ. Constr. Manag. 6, 37–47. doi: 10.1515/bjreecm-2018-0003

Beladi, H., Dutta, M., and Kar, S. (2016). FDI and business internationalization of the unorganized sector: evidence from Indian manufacturing. World Dev. 83, 340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.01.006

Blaise, S. (2005). On the link between Japanese ODA and FDI in China: a microeconomic evaluation using conditional logit analysis. Appl. Econ. 37, 51–55. doi: 10.1080/0003684042000281534

Chawla, I., and Kumar, N. (2023). FDI, international trade and global value chains (GVCs): India’s GVC participation, position and value capture. Asia Glob. Econ. 3:100071. doi: 10.1016/j.aglobe.2023.100071

Contractor, F. J., Dangol, R., Nuruzzaman, N., and Raghunath, S. (2020). How do country regulations and business environment impact foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows? Int. Bus. Rev. 29:101640. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101640

Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. (2023). FDI statistics archives. Available at: https://dpiit.gov.in/publications/fdi-statistics/archives

Donaubauer, J., Meyer, B., and Nunnenkamp, P. (2016). Aid, infrastructure, and FDI: assessing the Transmission Channel with a new index of infrastructure. World Dev. 78, 230–245. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.015

Dunning, J. H. (1979). Explaining changing patterns of international production: in defence of the eclectic theory. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 41, 269–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0084.1979.mp41004003.x

Embassy of Japan in India, (2023). [List of Japanese companies in India] indo shinshutsu nikkei kigyo list. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Available at: https://www.in.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_ja/11_000001_00669.html (Accessed August 13, 2023).

Friedt, F. L., and Toner-Rodgers, A. (2022). Natural disasters, intra-national FDI spillovers, and economic divergence: evidence from India. J. Dev. Econ. 157:102872. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2022.102872

Fukao, K., and Hoon, C. (1996). Factors determining the countries of direct investment -an empirical analysis of the Japanese manufacturing industry- Tyokusetsu toshi koku no kettei yoin ni tsuite - waga koku seizo gyo ni kansuru jissyo bunseki. Japan (Tokyo): Financial review Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Finance.

Harms, P., and Lutz, M. (2006). Aid, governance and private foreign investment: some puzzling findings for the 1990s*. Econ. J. 116, 773–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01111.x

JICA, (2022). After story of a former JICA student Moto JICA ryugakusei no after story. Available at: https://www.jica.go.jp/kansai/story/20221202.html (Accessed April 5, 2023).

JICA (n.d.). Special terms for economic partnership (STEP) | what we do—JICA JICA Available at: https://www.jica.go.jp/english/activities/schemes/finance_co/step/index.html.

Kang, S. J., Lee, H., and Park, B. (2011). Does Korea follow Japan in foreign aid? Relationships between aid and foreign investment. Jpn. World Econ. 23, 19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.japwor.2010.06.001

Karakaplan, U., Neyapti, B., and Sayek, S., (2005). Aid and foreign direct investment: International evidence (working paper no. 2005/12). Discussion paper.

Kimura, H., and Todo, Y. (2010). Is foreign aid a vanguard of foreign direct investment? A gravity-equation approach. World Dev. 38, 482–497. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.10.005

Kumari, K., and Ramachandran, R. (2023). The never-ending debate: do FDI promote institutional change? Evidence from India and partner countries. J. Policy Model. doi: 10.1016/j.jpolmod.2023.10.005

Lee, H.-H., and Ries, J. (2016). Aid for trade and greenfield investment. World Dev. 84, 206–218. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.03.010

Liao, H., Chi, Y., and Zhang, J. (2020). Impact of international development aid on FDI along the belt and road. China Econ. Rev. 61:101448. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2020.101448

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (1992). Japan’s official development assistance charter. Available at: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/summary/1999/ref1.html (Accessed June 19, 2022).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, (2004). Japan’s official development assistance charter. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Available at: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/reform/charter.html (Accessed June 19, 2022).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, (2015). Cabinet decision on the development cooperation charter. Available at: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/page_000138.html (Accessed March 9, 2024)

Nayyar, R., and Mukherjee, J. (2020). Home country impact on outward FDI from India. J. Policy Model 42, 385–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.06.006

Nepal, R., Paija, N., Tyagi, B., and Harvie, C. (2021). Energy security, economic growth and environmental sustainability in India: does FDI and trade openness play a role? J. Environ. Manag. 281:111886. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111886

Nishitateno, S. (2023). Does official development assistance benefit the donor economy? New evidence from Japanese overseas infrastructure projects. Int. Tax Public Finan. doi: 10.1007/s10797-023-09788-8

Noorbakhsh, F., Paloni, A., and Youssef, A. (2001). Human capital and FDI inflows to developing countries: new empirical evidence. World Dev. 29, 1593–1610. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00054-7

OECD (2023a). Official development assistance (ODA). Available at: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/official-development-assistance.htm (Accessed May 10, 2023).

OECD (2023b). Aid (ODA) disbursements to countries and regions [DAC2a]: Open data - bilateral ODA by recipient [DAC2a]. OECD.Stat. Available at: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=42231&lang=en# (Accessed August 13, 2023).

OECD (2024) Foreign direct investment (FDI). OECD iLibrary. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/finance-and-investment/foreign-direct-investment-fdi/indicator-group/english_9a523b18-en (Accessed May 10, 2023).

Ono, S., and Sekiyama, T. (2022). Re-examining the effects of official development assistance on foreign direct investment applying the VAR model. Economies 10:236. doi: 10.3390/economies10100236

Keywords: Japan, India, foreign direct investment, questionnaire survey, official development assistance

Citation: Ono S and Sekiyama T (2024) The impact of official development assistance on foreign direct investment: the case of Japanese firms in India. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1351285. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1351285

Received: 06 December 2023; Accepted: 04 March 2024;

Published: 15 March 2024.

Edited by:

Ian Tsung-Yen Chen, National Sun Yat-sen University, TaiwanReviewed by:

John Stephen Hoadley, The University of Auckland, New ZealandCopyright © 2024 Ono and Sekiyama. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saori Ono, b25vLnNhb3JpLjg2Y0BreW90by11Lmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.