- International Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands

In Libya’s protracted conflict, authoritarian, illiberal, and democratic practises exist at local and (inter)national levels. The repeated occurrence of crises in governance and rule of law, such as sudden restrictions on civil society or deferred elections, opens a window for the emergence of civic practice. Drawing on Kaldor’s concept of war and peace logic and a development ethics viewpoint, this study will critically discuss how manifestations of civic logic depend to start with on inclusive actor selection. This paper, based on Libyan-led co-inquiries and an analysis of dialogues and actions from an EU-funded rule of law programme, will demonstrate how the involvement of a diverse group of Libyans initiates manifestations of civic practice that are used during times of crisis.

1 Introduction

Libya is a collection of functional official and unofficial parts where authoritarian, illiberal, and democratic practises are found at local and (inter)national levels. It is not a functional state, as no formal state power is in place (Shaw, 2024). External actors recognise Libya as a state for various reasons. Europe views Libya as a crucial partner in border control and immigration, and its oil resources give it a significant global economic position. It also maintains its political influence as a founding member of the African Union. Libya is a strategically important economic power in the region, making its political instability a threat both internationally and to Libyans.

Since 2011, a struggle based on identity (Hilsum, 2012) and wealth, rather than ideology (Laessing, 2020), has driven the protracted conflict in Libya. These drivers fuel the repeated occurrence of crises such as deferred elections or sudden restrictions on civil society. This hampers governance, rule of law, and daily life. Therefore, international actors support peace-building, state-building, and humanitarian development. So far, efforts to end conflict, hold elections, and strengthen human development have had limited success.

Meanwhile, Libyans take action to advance their well-being and counter infringements on their rights. Various countries, with the European Union (EU) being the biggest donor, provide support in their efforts. This has opened a window for people to intervene. In communities around the country, people manage to shift the balance between continued conflict, recurring crises, and advancing well-being. This can be perceived as the emergence of civic practice. This article will critically examine how manifestations of civic practice start with inclusive actor selection. Can we begin to understand how people unite in times of crisis, or what could hinder this, and to what extent? Understanding the current, everyday response of people to crises reveals what uniting for civic practice entails, what it demands of those involved, and strategies for strengthening it. Drawing on a multi-year case the central question examined is ‘What are the perspectives of Libyans on conditions for actor selection and participation that contribute to civic practice in times of crisis?’

The article is organised as follows. The first section explains the theoretical framework, followed by the context in Libya and the methodology. The next four sections present the findings, focusing on actor selection and dynamics. The final section discusses the impact of the findings on the concept of civic logic. This shows that, next to authoritarian and illiberal practises, civic practices emerge and have an impact on the Libyan conflict and crisis.

2 Civic logic in practise as grounded in development ethics—theory and concepts

A range of concepts can be found to advance development over conflict: from peace-and state-building, via conflict-resolution and management to peace-and state transformation (Mac Ginty, 2013; Debiel et al., 2016; Richmond, 2018; Boege et al., 2008; Autesserre, 2017). One research line in the scholarship on conflict examines what is fuelling conflict, hindering peace-building and undermining equal, sustainable democracy and development. Scholars in this line focus on geopolitics, states and official (INGO) documentation with a Western dominant angle (Richmond and Visoka, 2021; Mac Ginty, 2021). Indeed, the conceptualisation and implementation of policy and research are firmly in the hands of mainly Western actors seeking to intervene in conflict contexts (Debiel et al., 2016). They call for localisation, participation and inclusion of different actor-perspectives, but stress how difficult this remains in practise (Autesserre, 2014; Mac Ginty, 2013; Richmond, 2018; Boege et al., 2008). With international actors dominating not only the design of interventions but also their evaluation, the lack of capacities at the national and local level is highlighted as one of the possible problems and not elements of the liberal peace paradigm itself (Richmond and Mitchell, 2012). The discourse and principles of interventions (often ‘blue-prints and toolboxes’) are studied. What is not specifically addressed though is by whom exactly (successful) efforts to build peace are locally conceptualised and conducted.

Apart from the way the discourse plays out, what happens in practise is important to achieving (competing) ambitions amongst a variety of actors with different roles and dynamics. Normative descriptions of concepts such as the everyday, local ownership, and participation then come alive. A focus on the micro-context is found in the concept of the study on ‘the everyday’ in which people, with their actions, create elements of transition. People’s interactions are often ignored as drivers of peace (Mac Ginty and Richmond, 2015), while the resulting ‘everyday peace’ can be found in abundance in conflict settings (Mac Ginty, 2021). For Mac Ginty, ‘everyday peace’ is the social interaction between people that can disrupt conflict. Diversity, as the opposite of a homogeneous understanding of the world, plays an important role in this concept (Mac Ginty and Williams, 2016; Richmond, 2018). While the diversity of people in their communities may thus be acknowledged, it remains difficult to grasp how the top-down and international efforts interact with the bottom-up and local processes. Acknowledging power dynamics and examining them is needed to do so.

The concept of ‘hybridity’ in peace and state-building highlights the importance of a dynamic and divers social process that includes power at the international and local levels in peace-and state-building (Mac Ginty and Williams, 2016; Richmond, 2018). It has been criticised for reinforcing binaries and oversimplification, resulting in a concept of ‘critical hybridity’ (Forsyth et al., 2017, p.407). This concept examines the complexity of the level of action, the multiple actors, the variety of value systems and their interaction (Forsyth et al., 2017). Hybridity is used in a descriptive and prescriptive way that could be successful if multi-actor dynamics and power are considered contextually and the tendency to design interventions that follow a script is avoided. The inclusion of different perspectives and understandings may thus be required from the start to advance peace or development (Wallis and Richmond in Forsyth et al., 2017). For this to happen, people become important actors in policy, research and practise.

Studies on people’s perspectives, actions and participation employ a dominant (inter)national angle. (Inter)national actors are deciding on how peace or a state can be built, and they limit the actor group, ambitions and approaches (Richmond, 2022; Mac Ginty and John, 2022). The research on localised and bottom-up interventions often avoids addressing power dynamics (Richmond and Visoka, 2021). This may have to do with the dominant liberal perspective of the local arena and the actors where intervention is needed. Local actors in local spheres are seen as responding to interventions via resistance, cooptation, contestation, or acceptance (Richmond, 2018; Ware and Ware, 2021). Their independent position in the process is less considered. This is examined in a case study on Syrian civil society participation. The consistent inclusion of local people from a variety of backgrounds and their ideas and reflections contributed to the peace process. The study demonstrated that it took over 3 years to lobby for civil society to play a role in informing the peace process. Ultimately, this worked by creating a space for civil society meetings that was kept apart from the official peace talks. Amongst the political stakeholders and the civil society actors, different views remained on the roles, positions and level of inclusion that were preferred. Despite this limited involvement, the civil society presence yielded results not only in transforming the political process and behaviours of (inter)national actors but also in bridging differences amongst the broad group of civil society actors and inserting a sense of civil influence or logic. The study further highlights how exceptional even the ‘controlled participation’ of those affected most remains in the efforts to address conflict (Theros and Turkmani, 2022).

In practise, the power to decide who gets a place at the table remained in (inter)national political hands, even though alternative solutions may have been found by acknowledging the power exerted by local actors. They have the capacity to independently create interventions and move beyond resistance or acceptance. The independent capacity featured in the efforts of scholars, international development organisations and donors looking to improve the outcome and impact of external support on development. They aimed to generate, test and refine context-specific solutions in response to locally nominated and prioritised problems, and during this process to expand the community of practise to share and learn at scale (Fritz, 2007; Andrews et al., 2017). This way of working favoured a focus on local problems, of multiple actors and with attention to flexibility, dynamics and complexity around development (Pett, 2020). The use in more technical or more political arenas (Parks, 2016) and limited research so far (Dasandi et al., 2019) has not let to proof of effectiveness of the concept. More importantly, this approach continued to start with and rely on external support to address development problems. It remains a widespread assumption that this is essential (Autesserre, 2017). External actors stress the importance of the inclusion and participation of local stakeholders and local ownership but remain in control themselves. Only in incidental cases, local actors are truly in the lead, as is shown by Ibrahim who developed her model and approach to participation and empowerment based on her research with, by and for poorer groups in society (Ibrahim, 2017).

This study is grounded in the described body of knowledge. It starts with bottom-up, contextualised approaches next to top-down interventions, acknowledging the dynamic relationship between the international and the local, the institutional and the individual, and drawing attention to diverse actor perspectives. The study’s focus is on two identified gaps. People, rather than external actors, are less frequently studied as the driving force behind interventions. This also emphasises the lack of attention to value-laden discourse and approaches. To examine these gaps, this study used the concept of civic logic (Kaldor, 2020), with a development ethics perspective (Goulet, 1997; Crocker, 2014), and focused on practises (following Glasius, 2018) of inclusion and participation, as explained below.

Freedom House reported in 2023 that an increase in democracy is no longer evident and authoritarianism is on the rise. Regardless of the political system that is in place, popular movements around the world are churning, and people continue to defend their rights and rally against oppressive systems to advance their well-being. This struggle, including in Libya, can be understood as driven by ‘three logics of public authority’ (Kaldor and Radice, 2022, p.125). Public authority is defined as any conglomerate of people voluntarily uniting for a cause, be it states, communities, or action groups. Two of the logics used to pre-or describe the functioning of the public authority tend to fuel conflict (Theros and Kaldor, 2018). The first logic, the political marketplace, is driven by financial transactions for loyalties, and the second, identity politics, mobilises people to support sectarian and often excluding agendas. The third, civic logic can be found in the way actors aim to unite and find common goals and services that shift the balance between conflict and development. Here, people with different perspectives join forces for shorter or longer periods to advance common goals of collective well-being. This way, they change the way authority is defined and exercised, and may shift the social condition of conflict (Kaldor et al., 2021). Public authority can use the three logics to impact the balance between conflict and development in the actual and everyday reality of people.

In reality, the theoretical knowledge available on advancing development and ending conflict has limited use, as dominant (conflict) perspectives and habits hinder the expected positive contribution of moral and social diversity (Loschi and Strazzari, 2018; Richmond, 2013; Debiel et al., 2016; Mac Ginty, 2011). In addition, impact on human development requires, alongside a theoretical framework, lived experiences (Gasper, 2009). Lived experiences or practises can be indicators of what moves people, what dynamics emerge, and what shifts occur in a context. Inviting the actors who are truly impacted in a moral-social debate can indicate that ‘every’ person can gain from development and that all stand together to achieve this (Keheler in Drydyk and Keleher, 2020). This draws attention to ‘configurations of actors in organised contexts’ and looks beyond the state and regime level (Glasius, 2018) to understand what alternative efforts can work. Glasius proposes to look at authoritarian practises. She examines their presence and emergence within society at large instead of being solely connected to the state level. Authoritarian practises can be defined as ‘a pattern of actions, embedded in an organised context, sabotaging accountability to people over whom a configuration of actors exerts a degree of control, or their representatives, by disabling their voice and disabling their access to information’ (Glasius, 2023, p. 10). These practises can coincide with illiberal practises, a separate category that infringes on the autonomy and dignity of a person.

Like authoritarian regimes, democracies can also be studied as practises. There is a large body of literature on democracy (Downs, 1957; Dahl, 1971; Beetham, 2008) with a focus on elements of a regime such as elections and institution building. Corresponding democratic practises can, in line with Glasius, be seen as strengthening accountability. Civic practice is then something different, connected to the use of rights and adherence to obligations by autonomous people. This practise can be beneficial to addressing the complex process of diminishing conflict and advancing well-being. This would start with including diverse perspectives and, thus, people.

The sought change depends on understanding what inclusiveness and participation entail. These concepts are closely aligned and examined in a comprehensive way in the inclusion project (Bell, 2019). Inclusion is described as having many angles. These range from the diversity of actors, to their perspectives, their agenda setting, the arenas they use and the process they follow. Different actors agree on inclusiveness being important for conflict and development, but not necessarily on what this entails and how to obtain inclusion. Ultimately, what is needed for inclusion is to manage the presence of the different actors (and not exclude actors), accept the ‘imperfect’ of solutions and acknowledge the multilevel overlapping processes (Bell, 2019, p.15–16).

This study uses inclusion as referring to the process of engaging a range of actors, such a various ethnicities, genders, or power-holders. This inclusion also refers to the different perspectives the actors have and, what agenda they set for the process at hand. This inclusion depends on participation. In this study I refer to participation as a process that allows people to have presence. Lederach refers to this presence as the time allowed by all actors, time used for exchange and listening to what everyone feels, and values next to their ambitions or needs (Lederach, 2019). In this sense, participation is about engagement between actors. It is a process between people and not one group of actors declaring another group should participate. All actors can decide for themselves whether they join in a process. The inclusion and presence wicked challenges people face today require not only a bottom-up or top-down driven process, but engagement of actors (Leal, in Cornwall and Eade, 2010).

To ensure actors can be part of the process as described above, it matters in the first place who decides what actors are invited to participate. This will be examined using the central question: ‘What are the perspectives of Libyans on conditions for stakeholder selection and participation that contribute to civic practice in times of crisis?’

3 The emergence of civic practice in Libya: context, materials and methods

Since the revolution toppled the autocratic regime of Colonel Qaddafi in 2011, Libya has been in conflict, with parties nurturing incompatible goals (Jabri, 1996). Practically, the country is divided into two parts without an elected central government. The UN first recognised the Government of National Accord (GNA) (UNSG Resolution 2259, 2015), followed by the Government of National Unity (GNU). They were put in place to prepare for what was seen as the most important task, elections in December 2021. The government’s legitimacy remained contested, with UN recognition overtaken by a vote in the Libyan House of Representatives on March 10, 2021. This Parliament was elected in 2014, and its term has long since expired. The GNU controls a part of Tripolitania. A larger part of the country in Cyrenaica and Fezzan is under the effective control of General Hafter, who also operates without a legitimate power base. Both central authorities have twin institutions in place and rely for the execution of their power on communities and a variety of armed groups to exert power locally and keep areas afloat.

There is thus no legitimate power in place, and this status quo is upheld as actors in and outside the country benefit from it. Authorities hold positions and wealth due to the political deadlock and continued oil exports, bringing in resources and keeping the economy going. Armed groups generate funds with their control of areas while legal and illegal trade continues. Violence erupts occasionally between communities, i.e., between neighbouring towns or between armed groups, often in Tripoli. At the national level, the stalemate between parties continues, with occasional efforts to extend their control, most recently in the summer of 2023. Libya’s recognition as a state accommodates national-level negotiations for political settlements. It suits the international community, as Libya is important due to its resources and geographic location. The relative stability in this protracted conflict context also benefits the people to a certain extent. Schools remain open, funds are generated, and life goes on. Yet the de facto costs are immense for citizens, immigrants, refugees, and the country itself (Amnesty International, 2020; Human Rights Watch, 2023). So far, international interventions and national negotiations have neither contributed nor resulted in a settlement amongst parties or durable peace.

The presence of diverse communities, with people voicing different viewpoints within and amongst them, requires attention to be given to pluralism in politics, constructing (limited consensus), and transparency (Wehrey, 2018). This tolerance for diversity has been lacking in Libya since 2011. After the revolution, several moments provided a chance for political stability, such as the elections in 2012 and the different successful municipal elections. Yet rampant corruption, a lack of infrastructure, and state institutions have diminished public trust in democracy and government (Wehrey, 2018). Interference from outside has further fuelled conflict. In addition, both religious and secular viewpoints have an impact on Libya. This further increases polarisation and is especially challenging for women aiming for a more equal place in society. ‘There was a big disagreement about the justice of Libyan laws and the granting of rights to women, as the audience was divided into those who believe that Libyan laws are fair to women and we only have to apply them fairly, and there are those who believe that there are no Libyan laws that protect and guarantee women’s rights, and the law must be developed to grant the rights of women’ (032-DR1, 2023).

Despite some progress, such as the number of women holding jobs, participating in politics, or being able to travel alone, women remain vulnerable, as can be said of the youth. They make up 50% of the population but are disengaged from politics, with 26% being unemployed while seeing the success of armed groups enforcing power with impunity (Khalifa and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2022). These armed groups provide for and undermine security. Together, these political, social, economic, and religious entities, structures, and systems share power and form a fractured landscape that lacks stability, legitimacy, and a vision for the future.

In this context, people play an important role. They organise themselves in community groups, known in Libya as civil society organisations (CSOs). They operate as a civil society with a focus on the association of people (following the definition of Biekart and Fowler, 2022), yet they are by no means professional organisations. The CSOs working on governance, the rule of law, and human rights operate against the grain despite serious challenges and personal risks. In their communities, they examine the possibilities and take action to influence developments in Libya civilly. This could be said to be true of all times and places. In Libya, it is less acknowledged, recognised, or researched as an element that may shift the dynamics in the country. This study highlights the efforts of these Libyans and the impact they have.

4 The SHARP approach: civic practice emerges

There is a modest yet active civil society, voicing different opinions across the country. In general, one or two active people take the initiative to inform community members and engage them in locally developed activities in the domains of governance, human rights, and the rule of law. The leading figures are not seen as representatives of a community, and they operate separately from the authorities. They see mobilising people, framing collective ambitions based on existing needs, and achieving progress as their tasks. These community activists or groups are known in Libya as civil society organisations (CSOs). They are best described as community groups of engaged people. They combine features of civil society by fostering social ties and uniting ambitions, with those social movements challenging the order through positive unconventional contributions in the political process (Della Porta, 2020). While thus often being engaged people, following the custom in Libya, they are referred to as CSOs in this article.

In December 2019, the Shared Action for Rule of Law Progress (SHARP) was co-created by an international think tank, an international implementing partner, and Libyan representatives from the judiciary, academia, and civil society activists from across the country. The European Union (EU) funded SHARP to launch a mix of dialogues and project opportunities on governance and rule of law issues that matter to Libyans (SHARP O&M 2019/2022). SHARP had an adaptive management approach, facilitating adjustments, and in this way, it supported Libyans in growing a network where people meaningfully advance governance and the rule of law.

From December 2019 until February 2024, a network of 64 locally supported CSOs across the country emerged. Participation was open to all CSOs contributing to the rule of law, with a free choice of topics and approaches. The groups came from across the country, across political divides and ethnicities (see Map 1).

MAP 1. CSO participation in SHARP. Source: authors’ adaption of Map No 3787 rev. 10, United Nations, November 2015.

Civil society organisations organised the key SHARP element, dialogue sessions between Libyans, aiming to build (partial) consensus on priorities and match concrete actions needed for progress in governance. Two hundred and fifty nine dialogues were held in communities amongst the general public, with 4,137 participants of whom 44% were women. They offered a platform for individuals to express and test their ideas about possible actions that promote the rule of law in Libya and have a direct impact on citizens. Participants were challenged and encouraged by each other. Once collective ambitions emerged, they could join the second SHARP programme element, a sub-contracting facility. This fund disbursed funds of up to EUR 25,000 to 54 projects designed and implemented by eligible CSOs. Their actions reached over 7,000 people. The activities included all types of gatherings that are conducive to improving and promoting the rule of law, such as public advocacy, training of police officers, education programmes for the youth, and creating access to justice for women. Initiatives were always supported by at least two organisations in a community, such as the municipality or a legal association. Libyans thus initiated, supported, and implemented dialogues and actions across the political fault lines and multiple power bases.

5 Methodology

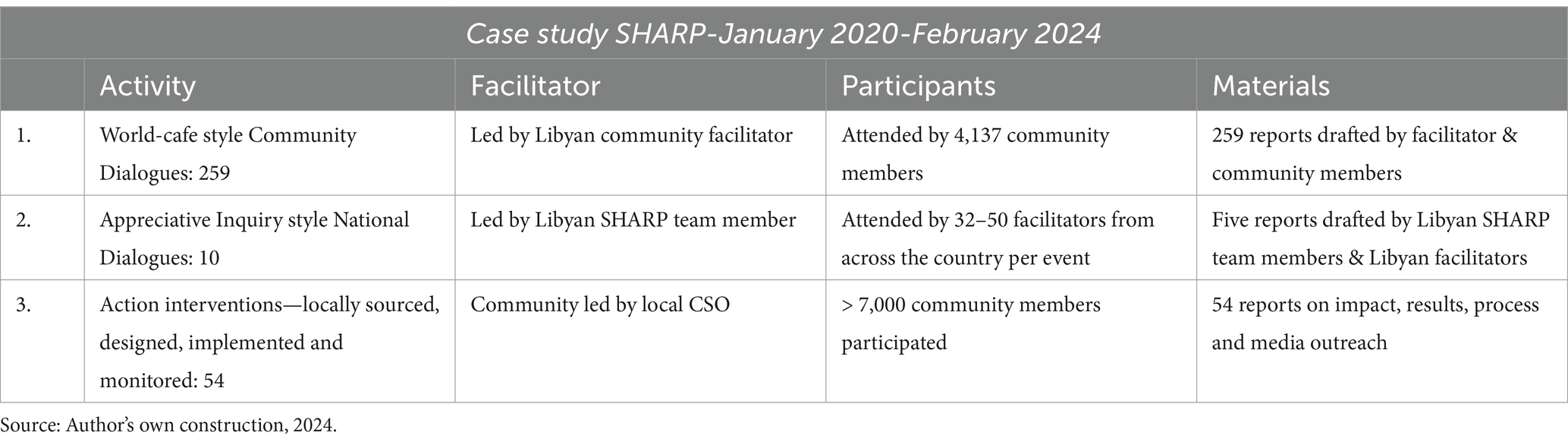

This article draws on the data collected as shown in Tables 1, 2. All dialogue sessions were prepared and reported on by Libyan CSOs with their respective communities. Participants came from urban and rural settings, different education levels, professional backgrounds and included minority groups, youth and elders. In the dialogue sessions examined, 4,137 participants joined of which 44% were female. The implemented actions were also entirely designed and implemented by Libyans and reached over 7,000 community members of which 50% were female. All dialogues and interventions were conducted in Arabic and reports were translated by the same Libyan translator for analysis.

Based on the initial findings, the main research question was further examined in a set of three Libyan led co-inquiries. Ten Libyan research practitioners, five men and five women, joined a short training session and participated in the co-enquiry design. Their provided comments improved the materials for the sessions. All preparations for the implementation, including timing, invitations, and reporting, were in Libyan hands. They selected local actors interested in advancing Libyan development and willing to share their opinions and experiences in the co-enquiries. The participants, on average 15 people, shared their individual experiences and ideas based on three questions related to development ethics: on actor selection, on the ambitions of actors and on the approaches they see as important for strengthening the rule of law and improving well-being.

Qualitative research can be viewed as subjective. The chance to pick up on things that are not there or to miss issues that seem obvious remains. By including people from various backgrounds and cities, I tried to acknowledge the range of perspectives and approaches in the research that exist in Libyan reality. It could be said that topics and insights that recurred gained importance. By analysing reports of dialogues that were held over several years and using different rounds of inquiry, I have tried to create room for topics that had not emerged initially, or reinforce the importance of the earlier mentioned issues. This way, I hoped to prevent a certain discourse from becoming dominant or issues from being swept under the rug.

The focus on dialogue and action interventions tried to capture what remains hidden when using questionnaires and interviews. The motivation and workings of actions require research that grasps the invisible considerations of people, as Roelofs showed in her study on the perceptions of good governance (Roelofs, 2023). Multiple understandings and highly contextual ‘invisible’ values are what drive people. Picking up on these understandings was helped by not just analysing the mere text of reported viewpoints, but also reading into them.

The analysis of the data allowed for an investigation of the actor dynamics and variety of perspectives on ambitions and approaches that make up the people’s response in their search for change. The choice for this participatory action research was made to ensure people directly involved in the case are part of the research process. They are best placed to examine what matters to local people and how they understand their context and arrive at actions. This approach was used in all SHARP activities, as well as in the co-enquiries organised for this study, thus giving Libyans ‘leading, owning, and delivering’ the results (Lilja and Höglund, 2018, vol. 24, p. 416).

The data have been analysed in two rounds of coding, manually and via Atlas.ti. The elements to code with were distilled from the concept of civic logic (Kaldor and Radice, 2022) and practise (Glasius, 2018; Glasius, 2023), and the initial dialogue reports. For this study, they focused on diversity of actors, inclusion, and trust. In the next three sections, the findings of the study are presented with a concluding case of civil society dialogue and action during crisis.

6 Findings

What are the perspectives of Libyans on conditions for actor selection and participation that contribute to the emergence of civic practice? This has been observed in dialogue and actions in Libya between 2020 and 2024. In this chapter, these observations are presented and analysed using the identified elements of inclusion, trust, legitimacy, values and customs.

In the first section, the inclusiveness of actor selection is examined in communities (6.1) and with national actors and across commutes (6.2). The actor variety is presented and the challenges and opportunities discussed. How people as legitimate actors united in times of crisis is then presented in a specific case study (6.3). The next section then discusses the findings and includes Libyan considerations for future efforts relating to actor selecting (6.4). The study investigates what civic activity looks like in (post-)conflict by investigating which actors engage and what obstacles may exist. This sheds light on alternative behaviour for development interventions to manifest themselves, as discussed in the conclusion (6.5).

6.1 Inclusiveness requires engagement

Libyans discovered that the sharing of perspectives, ideas and knowledge benefits from broad engagement. In communities, lively debates were locally facilitated with participants from different backgrounds. They were united in their ‘willingness to participate’, mentioned facilitators from all regions (CIR-1, 2023). People organising the dialogues did this in their own time and only out-of-pocket costs were reimbursed. Participants attend as they were interested in obtaining or sharing their knowledge and experience. This way, inclusive gatherings took place. Here, fellow community members engaged across divides of profession, age, or gender.

People came from a variety of backgrounds and professions. Most of them were ordinary people. They identified themselves as lawyers, legal advisors, judicial engineers, health workers, media representatives and government officials. Next to this, people mentioned to be working with NGOs, and politicians participated once invited. Next to those (academic) educated people, there are many traditional family men and women, being housewives or working in the oil industry, banking sector or small businesses.

The SHARP programme and consequent co-inquires took place across the country. The people participating in legitimate advocacy in dialogues and actions for change came from all social strata in communities: lay(wo)men, experts, such as engineers, lawyers, and health workers, media representatives, academics, politicians, government officials, and tribal elders. Participants were recognised as being ‘a diverse class belonging to different political affiliations and tribes’ and from all ethnicities, ‘Arab, Touareg, Amazigh, and Tebu’ (CIR-1, 2023). Different ethnicities and tribes were thus represented in the communities they live. In Cyrenaica, more tribal elders participate while in Tripolitania the representation of Amazigh is high, like in Zuwara and Gharyan. In the south, the Tuareg and Tebu are well represented as native of the area.

The diversity amongst participants ensured conversations were not dominated by one or two experts. This was supported by following agenda’s, limiting the time for introducing of a topic to on average 20% of the time of a meeting.1 This led to meetings were people were invited to contributed their knowledge and experience. This fuelled participation. ‘When the dialogue began, the debate intensified by brainstorming through the information presented as well as value added by the participants. The final impression was excellent and approximately 75% of the participants expressed a desire to repeat the experience of attending such a dialogue on other important topics’ (022-DRX, 2022). It could be said that all participants felt to be experts: as speciality that they are knowledgeable in what matters in their local community, from their different perspectives. The wide participation of women ensured the difference between men and women, and between women due to their profession, believe or origin, are well taken into account.

Groups led by and focused on women’s issues joined SHARP from the start. Women encouraged, informed, and strengthened their capacities and that of the men participating. The presence of women was not evident from the start in all communities, while in others it played a central role to ‘empower women within decision-making areas [.] and develop their capabilities through capacity-building programmes’ (051-DR3, 2023). Women were recognised as having different contributions to make. ‘The role of women in municipal councils is not limited to social affairs and women’s affairs, but their tasks are not less than any other male member of the various committees and they must exercise their roles’. The participants in the session agreed on several points related to women and their rights, which the Libyan Constitution clearly ignored and instead used broad and superficial expressions (046-DR1, 2022).

Within a year, all groups included women, leading to the overall participation of women at around 45%. In a conservative town, the first meeting had only male attendants, but proposing the idea to invite women ensured their continued presence over the years. Women stated that this had to do with informing men about the importance of equal participation. The men in the events experienced women’s participation, which is crucial for advancing development and lasting peace.

Women not only participated, but they also actively voiced concerns and ideas and their input was reflected in dialogue and action reports. In a southern town, women noted how the culture of law was entering the women’s domain (002-DR1, 2020). The presence of women also contributed to successful engagement with (security) officials and armed groups. Women trained the representatives of these groups on how vulnerable victims are, and they also informed other women about their rights. A balanced dialogue was reported in the community between victims, security officials, and the judiciary. Women operating in their communities had a voice and felt able to speak up in public for a cause (023-AR, 2022).

In addition, both women and men named their shared values and customs as unifying elements for their contributions. Libyans agreed important values were Reconciliation, Community balance; Relationships, engagement, Mediation, Equality, inclusiveness, diversity, participation, honesty and credibility (CIR-1, 2023). They felt these played a role in their daily lives. Customs were used to indicate the engagement amongst people. Respect plays an important role, between people in general, and especially towards those of older age. It also has a more negative connotation, the cultural heritage of the tribal influence, the position of ‘elders’ across society and the influence this has on the position of women.

The inclusion of youth proved harder to achieve. Youth groups did emerge, but at a much slower pace. Youth saw they faced an uphill battle in a society that cherishes old age, participants note. Once a group of youngsters united, for example, in schools and universities, they had to find a respectful way of engaging with the elderly. The youth then increased in influence due to the qualities they bring, especially in the use of (social) media and finding IT solutions. People noticed the value of these different skills and perspectives for the community. As one participant mentioned, young women faced the most challenges. She saw the solution in strengthening equality in all (professional) roles in society. ‘Once people encounter not only women politicians but also female janitors or truck drivers, equality and inclusiveness are expected to grow’ (032-DR1, 2022).

The subtle approach women and youth displayed to gain their place depended on having different contributions, good facilitation skills or knowledge on media and IT. Diversity was possible even in conservative towns like Zliten, Misrata, and Bani Walid, as people shared a similar background, customs, and values. This generated trust and ensured a place for those willing to participate for the benefit of their community. Inclusiveness became a key requirement. ‘People not accepting different perspectives or those inciting against reaching consensus and presenting obstacles to any accord’ are not welcome (CIR-1, 2023). This did not mean disagreement was banned. On the contrary, people discussed openly different viewpoints, for example, whether ‘the presence of prisons and armed groups outside the authority of the state and bad treatment in cases of detention and imprisonment are a reason why people do not resort to the law’ (041-DR1, 2023).

The inclusive participation taking place with contributions being valued evenly and acceptance of difference is a starting point for inclusive processes. A word of caution was given too. Diversity amongst actors requires accurately targeting participants, taking into account their specialties and social backgrounds. This does not mean everybody is always participating, but will get the chance to do so. It is seen as a way of selecting actors, including people, who have the widest variety of knowledge and experience. The different perspectives of all actors increase the chance for different needs and ambitions to surface. This requires a broad engagement base and direct communication to start with.

Of course, not everyone in a community participated in a dialogue or activity. Asked what could be the reason for not attending Libyans named security concerns, due to appearing in the media or becoming known in the community. This reinforced the idea that the many people that did attend, often took personal risks. They did as they seek a way forward in the never ending conflict. They feel limited exposure to security risks, may bring about a transition to less conflict and more progress (CIR-1, 2023).

People also mentioned practical reasons: lack of transportation, personal/family circumstances, or social conditions. Highlighted were further the lack of commitment to bring about change of some, the unfamiliarity with governance and rule of law, lack of confidence in the possibility of change and values and norms in society that are not favourable to change. Libyans referred to their ‘cultural heritage’, the influence of conservative ideas and tribal society. Sometimes this was beneficial, as elders mediated in conflicts, or supported movements. At other times, the same attitude could block change. Raising community awareness to easing the threat to and from cultural heritage required a very contextual approach to cater to the specific ties in an area, mainly in Fezzan and Cyrenaica. Those participating mentioned that they would not easily exclude people willing to attend. If needed, this would be done if people would be extremist or not willing to accept different perspectives as important to exchange. People with strong convictions on an idea should be able to attend, but allow others to voice their convictions too (CIR-1, 2023).

6.2 Inclusiveness outside communities: national engagement and intra-community connections

A remarkable finding was the nationwide efforts community members made to engage with institutions and authorities. Libyans stated that substantial steps towards a trusted and understood rule of law in Libya can only be achieved in partnership between Libyans, their national entities, and the international community (CIR-1, 2023). Even though authorities and institutions were not trusted for various reasons, i.e., their self-interest and corruption were named, as were their efforts to positively frame their actions without changing the status quo. Yet the history of a strong national level and the need to be accepted at the international level, ensured people continued to see the importance of ‘functioning and just’ national partners. Community groups emphasised that national entities can provide unity, stability, and development. This expectation made people feel responsible for engaging with authorities via legal means and civic action, thus creating an inclusive way forward.

The focus of SHARP on inclusion, meant people extended invitations for dialogue and action to authorities and institutions fuelled a bottom-up drive for engagement. It became standard practise to invite representatives of local or national institutions to dialogue sessions. In all 54 project activities, at least two external partners provide support with knowledge and access to (security) services, contacts, or resources. These partners came from, i.e., municipalities, audit bureaus, schools, universities, prisons, the judiciary and the police. It proved to be harder to involve the national level. In exceptional cases, national institutions and authorities responded to invitations. One community worked together with the local branch of the anti-terrorist unit of the military security force, while another worked together with the office of the national prosecutor. In these cases, actors recognised ‘inclusivity and participation’ as important pillars for their development (NR-June, 2021). A focus on shared interests was driving the cooperation. ‘The municipal council expressed support for the training course [on legal culture] within the city of Derna and urged the transfer and exchange of experience amongst employees to raise the efficiency of the council employees in the suburbs of Derna, as well as stressing the importance of informing citizens and employees of the importance of the role of the local administration in terms of competencies and powers’ (022-AR, 2022).

Changes in appreciation of the police, or access to justice, thus originated in communities. In rare cases this triggered a top-down initiative or participation. A human rights officer at the ministry of defence decide to conduct a training for officers on the principles and practise of human rights in Libya. The encounters with the public played a prominent role in the design and execution of the training (030-AR, 2023). The same can be said about the design and execution of mock trials in the Fezzan for law students, who engaged with the judiciary and lawyers (012-AR, 2023). This indicated a different approach, bottom-up and top-down, that can be used to rally different actors behind a common goal: advancing human development via stronger governance and rule of law in Libya.

Throughout the SHARP dialogues and actions, Libyan people agreed that raising legal awareness and trust amongst citizens and state authorities was an essential starting point. People thus took the opportunity to make a start and empower themselves. The engagement between actors was driven by local people. It is noteworthy that while the EU supported the bottom-up approach via SHARP, they hardly engaged directly in their efforts. They continued to mainly interact with national authorities. The Libyan people did not appreciate this and considered it to be a disqualification of their efforts and to be undermining of their emerging position (CIR-1, 2023). Libyans emphasised that the collective efforts of local communities, local and national authorities, institutions and international partners had to grow. (Inter)national actors remained reluctant to accommodate this.

Meanwhile, the communities also had an additional effort to make, namely engaging across communities. For many people, the cross-country meetings organised by SHARP were an entirely new experience: a first encounter with fellow Libyans from different communities. Several participants noted how ‘bringing different people into the room breaks barriers’ (002-DR4, 2021) as they discovered other people have similar experiences, ambitions, and concerns. In total, 10 country-wide events have been held. During the initial events, people merely listened to each other and focused on their own narrative. Over time, this grew into sharing experiences and knowledge. The realisation that reaching an agreement is not always necessary contributed to improving these dialogues. Participants shared their opinions with more confidence since they learned how disagreement can open-up space to engage with others.

People reflected on their new experience: discovering that the regional diversity of representatives had a positive impact on the results of the discussions. ‘We were also able to network and establish partnerships with local civil society organisations from various regions of Libya, east and west, north and south … These changes are important because they have enabled us to know more about the community in which we work. We have also expanded [our work] into a larger geographic range, up to Ghat, which is 650 km away from our centre in the west. Likewise, we included Qatroun in the south, at a distance of 250 km, and we are looking forward to more thanks to the experience we have gained’ (003-AR, 2022). Problems were seen in a new light, and this enriched the knowledge of all actors. This is not to say no challenges remained. Communities tended to look for exclusive community benefits they could obtain in cooperation with authorities. Having information on governance and rule of law topics was also seen as valuable, and this hampered sharing it widely. Yet, at other moments, the newly developed ties across communities gave a boost to collective action. This will be discussed below in the section on the impact of a crisis.

Inclusion can thus not be said to include everyone at all times, or sharing all in knowledge with everyone in Libya. Yet with the open invitation extended in communities, a diverse group did attend. They can be seen as a representation of the common Libyans: we saw ‘the participation of a member of the municipal council, the head of the Council of Elders, a number of interested people, activists, social leaders and a number of media professionals. Strong and active participation of women with a large percentage of the total number of participants’ (071-DR2, 2023). In addition this session, as many others, was aired live on the radio, reaching more people. The many participants also advanced new initiatives. In bigger towns, different groups emerged, as people were inspired by the dialogues held and their media outreach in an area of town and then took the initiative to launch their own ‘chapter’, either based on location, to advocated for a topic (media, disability) or gender or age (women and youth).

In conclusion, Libyans actively promoted inclusiveness at their local level. Communities saw their members as trusted actors sharing customs and values. They discovered change could be made step by step, based on bringing in new local expertise via women and youth. Progress was made in the inclusion of local authorities and institutions by inviting them. This resulted in engagement based on common ambitions and interests. Local authorities could count on a more powerful role due to the lack of responsibility taken at the national level and the fact that local solutions mattered to people. So far, only limited engagement with national actors has emerged, and this has been driven bottom-up. The standing invitation from communities towards authorities had much to do with the discussed need for inclusion at the start of the programme. However, the historic and practical value people attributed to the national level ensured people saw their participation as crucial. Furthermore they sought engagement of international actors to recognising the importance of inclusion: people, national actors and international partners all had a role to play. Finally, a delicate process played out between communities. Here, over time cooperation seemed to take root. People moved from attending inter-community meetings to voluntary sharing information and even taking collective action.

In the Libyan context, advancing local practise gained bottom-up traction for improving development. Libyans counted on their street-mentality: gathering popular support, and managing the scepticism and anger towards (inter)national actors. Skills people had, like perseverance and local knowledge were proposed to be widely used (CIR-1, 2023). This street-mentality, embedded in a moral-social context encouraged small shifts in the actor dynamics and may prove to be sustainable. Civicness seemed to emerge, amongst common people, local and even national actors. The detailed case below demonstrates this continued to happen when a crisis unfolded.

6.3 United we stand: civic practice in times of crisis

The absence of a comprehensive legal framework severely hampered the growth and influence of civil society and action in Libya. Legislation on civil society was in place, but it had not been amended to reflect the current situation in Libya. The old law also contained rules that contradicted the intentions and elements of newer laws. For example, the laws regulating civil society were not aligned with the regulations of the civil society commission or with the articles on civil society in municipal laws. Finally, the eastern and western parts of the country had installed different civil society commissions. In practise, this left the door open for random incursions into popular activity, infringements on people’s rights, and the banning of CSOs. People trying to organise themselves were facing unclear and different rules. For example, the way to register a CSO changed depending on location, sudden requests from authorities for information on planned activities emerged and reporting requirements on resources were incoherent. People looking to execute their civil rights were thus left in a vulnerable position due to a legal gap (015-DR 2, 3, and 4, 2022/2023).

Libyans continued to operate in these unfavourable circumstances. The growing presence of CSOs focusing on human security and governance has led to the regular banning of their activities, threats to activists, and declaring CSOs illegal (015-DR 2, 3, and 4, 2022, 2023). The restrictions hindered the CSO’s work and created doubt in the minds of citizens about whether it was legal to participate. In terms of Glasius (2018), via authoritarian and illiberal practises, crises are created either by obstructing work via rules or by threats against human rights. As explained below, the united front CSOs created resulted in a peaceful struggle for popular power.

In early 2021, Libyan authorities proposed a draft CSO law that seriously hampered the registration and activities of CSOs. In response, an established CSO in Tripoli took the initiative to analyse and re-draft parts of the law. Initially, the CSO worked with a well-known human rights organisation in Egypt. They contributed expertise, but the initiative lacked support in Libya. To gain traction, the Libyan CSO decided to introduce their initiative on the law to other CSOs working in the domain of the rule of law. They had met before in SHARP, but so far, seeking cooperation had not happened. An invitation was extended to discuss the CSO law at a planned meeting of SHARP. The proposal was well received and led to a joint meeting of 20 CSO members in June 2021. The assembled actors found one another in a collective aim to analyse the gaps in the law, the legal framework, and its execution while proposing actions and mechanisms to resolve the obstacles (015—Report, 2021). As a participant said, ‘The discussion catered for the aforementioned law and decision, the extent of their sovereignty and their application in the Libyan state, and the opinion of the different sectors on those decisions and laws and the mechanisms for strengthening them and improving the level of benefit from them’. CSOs relied on common interests and collective experience, which gave them the confidence to stand together in their struggle for recognition as relevant actors.

The organising CSO had also invited a representative of the civil society commission. This organisation supported the government’s draft law and was the implementing organisation of the law. In that capacity, they had actively suspended CSOs, blocked activities, and requested reports or insight into budgets that were regarded as illiberal. By inviting them, a conversation on the existence and objectives of civil society became possible. This conversation led to the agreement that the draft was inconsistent and against the principles of the rule of law in Libya. It was argued that the proposed law does not protect CSO work, lacks regulating mechanisms between the state and civil society, and requires CSOs to request ‘prior permission’ for basic activities. It was also noted that the municipal law connected to civil society law further restricts CSOs’ existence. Communities rely on CSOs’ work for some of their services at the same time. Again, the common interests of different actors created the opportunity to collectively pursue adjusting the defunct law. The group decided on practical next steps, including opening the discussion with the civil society commission in the East and West of Libya, continuing dialogue sessions on the importance of civil society and the law, designing a participation and communication mechanism for authorities and CSOs, and analysing and re-drafting the law. The CSOs managed to connect different levels of actors, in different ways. Communities in the South experienced more severe crackdowns and had to halt all activities for a while. In the East, CSOs are used to closer scrutiny and contact with the authorities and use their connections to continue their work.

Formal and informal meetings took place between March and September 2021. Participants noted the positive atmosphere amongst participants and attributed this to:

• The diversity of the backgrounds of the participants, including activists and representatives of governmental and semi-governmental institutions directly related to civil society.

• Active and positive participation of all actors in the discussion.

• Adhering to the allocated time and agenda of sessions.

• A focus on coming up with concrete recommendations (Report 015-2, 2021).

The meetings were also called successful due to the contributions people made based on their actual experiences. This connected the reality of CSOs in Libya to the concept of the rule of law.

In terms of action, progress was made in drafting improved articles for the law, starting lawsuits against the authorities regarding the lack of a formal base for the proposed law, and raising awareness on the need for and legal obligation of a civil society law. It was mentioned that the government needed to break out of the ‘ego spiral’ to operate solely on its own (015-DR2, 2021). They should instead work with other involved parties to ensure a valid and just law was put in place. Furthermore, the authoritarian and illiberal practises in Libya directed at civil society were discussed in light of the law. This led to agreement on the need to ensure free participation of every citizen in organising activities in the public domain, expecting accountability and transparency in the work of authorities, and demanding the parliament take on its role to draft and pass laws, including civil society law.

In a final session in the autumn of 2021, parties closely reviewed a final draft text of the law. It had been prepared with the support of some experts. The draft took into account seven basic rights, the right to form organisations, the right to work free from the unjustified interference of the state, the right to freedom of expression, the right to seek and secure resources, the right to communication and cooperation, the right to freedom of peaceful assembly, and the state’s duty to protect. With attention to detail, long discussions followed to include elements like the position of the youth and definitions in the text like the meaning of public morals (015-DR3, 2021). The session ended with the promise to continue as a group to pressure the parliament and government to issue a draft law and have it passed and implemented.

In the months that followed, the civil society commissions in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, and the parliament were engaged in discussions on the new draft. This was celebrated amongst CSOs as a victory. New amendments were proposed, and a final draft law was presented for voting in parliament. The vote did not take place, as is the case for many other laws in Libya, due to parliamentary disfunction. Yet with the law on the agenda, over an extended period, civil society experienced greater freedom in its activities. The enabled voice and free flow of information during the collective action period not only strengthened people’s capacities, but also created a shift in the dynamic between actors. People had gained presence and became parties to take into account. This paid off during a new crisis.2

In the summer of 2023, the civil society commissions backed by national authorities proclaimed all CSOs unlawful. This posed serious problems, especially in Fezzan, where this type of government announcement is strictly followed. CSOs had to halt all activities, and leaders were brought in for questioning. In addition, the growing trust in civil society amongst people around the country was disrupted. Questions started to arise about the position and intentions of CSOs. The unity formed amongst CSOs since their work on the law, amongst others, proved to be in place and resulted in a counter-movement. The right of Libyans to unite and take action as explained in the not-yet passed but drafted CSO law, the unlawfulness of the proclamation, and the need for the law to be passed were raised by CSOs nationwide. They handled the situation not with an open and outright protest. Instead, CSOs contacted local supporters, like municipalities and armed groups. They slowed down their work and used their time to strengthen local ties. They could point out their benefits to communities and collective action for the public good. After some weeks, this paid off, and CSO activities resumed as before.

As of early 2024, the proper protection for CSOs in Libya was still not in place. This remained a threat to those continuing their work. They persevered, as they had re-gained freedom and power. Citizens, local institutions, and authorities supported their work on a larger scale. Even national authorities reached out to CSOs once in a while. Libyans stood their ground during a human rights crisis. They believed in their right to act; they adhered to reasonable rules and local customs. They gained a position. The presence and power of civil society increased due to united action when it mattered most.3

6.4 Manifestations of civic practice in the actual and everyday—discussion

The emergence of civic practice can be observed between 2020 and 2024 in Libya. By examining which actors engage, participate and what may hinder this, the article examines what civic practice looks like in (post-)conflict. This sheds light on an alternative behaviour for development interventions to manifest itself.

In its findings, the study highlights how people willing to engage in and outside their communities empower not only themselves but also their authorities and institutions. This way, they impact the power dynamics of actors, and the social processes at the core of conflict and development. In different ways, these dynamics and processes show how emerging civic practice creates the conditions to advance pockets of human development even in times of crisis. Two discoveries emphasise important implications when thinking about interventions in (post-) conflict settings and times of crisis. People demonstrate to be crucial legitimate actors, and some key attributes for peace-and state building processes can be derived at differently.

First, people united for a cause, are recognised as the most important group to launch debate and take action. The exclusive focus on national authorities as key actors for development interventions keeps in place a mere utopia of a top-down approach to solving questions of conflict and development. This is not a reflection of reality, but a confirmation of the idea of regimes controlling nations, war taking place between two identifiable sides, and international intervention being successful. In real life, Libyan people show how (only) piece-meal steps taken by ‘conglomerations of actors’ (Glasius, 2018) shift the balance between various actors and their capacity to exercise a degree of control. This is something different than claiming bottom-up processes are the only way forward. It is a call for inclusive engagement with recognition of the differences between actors. The different perspectives and positions are valuable for the long-term, multi-actor process of managing multiple dynamics on questions of diminishing conflict and advancing development.

National authorities, without legitimacy formally obtained from Libyans, try to place united citizens in a shady light. Meanwhile, united people looking to exercise their rights continue to reach out to both other communities and the authorities. Exactly this perseverance in inclusive engagement gains them their place in the process. This does not mean civil society has an exclusive claim to civic logic. Without proper legitimacy, checks, and balances in place and acted upon, all actors can resort to favouring themselves or advancing economic gain for themselves. Similarly, national authorities, by allowing people to exercise their rights, show that civic practices can emerge next to authoritarian or illegal practises.

A focus on mutual benefits proves to be a good way to reinforce the engagement between actors. It has the added advantage that vulnerable groups such as women and youth can participate. They bring different viewpoints and skills that are beneficial to arrive at practical common interests. Abstract ambitions, i.e., reconciliation, a stronger economy, or stability are broken down in smaller concrete actions, like the training of police officers showed.

Inclusion and participation also underline the focus on the moral-social quality of the debate and action. Women and men of all ages put forward Libyan customs and values for advancing their society. They prefer small steps that stand in tradition over relying on externally accepted models. As long as most actors benefit, less conflict, even if it only means a small increase in well-being, is better than none at all. Libyan solutions work in this regard, although they may require time, dedication, and perseverance. These can be seen as resources that are available at relatively low costs.

Understanding why ‘conglomerations of actors’ exist is one thing, but not enough for change to take place. These actors require recognition as legitimate actors. Not only in special forums for civil society, but as players at the table and on various topics concerning conflict and development in a country. Neglecting the agency of people as legitimate actors is undermining their status in the process of ending conflict and bringing about development in their daily lives. Remarkably, the people engaged do not neglect (inter)national actors or ask them to drop their interests. By stressing the focus on common goals that can be found amongst all the different interests that exist, change beneficial for all could be achieved. Deciding what these common goals are and what approaches can be just, is a topic for further research. That actors need to be selected from a wider circle, including local people at all stages of a process, is just a starting point, albeit an important one.

Secondly, motivations, values, and actions, including their unavoidable disagreement, guide a process of collective searching for advancing society, even during a crisis. The collectively recognised and examined ambitions, grounded in Libyan values keep a united front of people in place. The social-moral grounding of people generates a form of power. This is not to say all conflict or power differences disappear through civic practice. Holding on to principles, such as inclusiveness to acknowledge the identity politics that are at play and equality to include the economic marketplace logic matters. Together, these logics inform, guide, and create a process of advancing development and diminishing conflict on track.

The process to strengthen civic logic in practise starts with including actors who are most impacted. Ordinary people thus matter. They proof to see themselves as legitimate actors and actively engage in inclusive processes to advance development. Which actors participate is thus a relevant question. The way it is answered in Libyan practise demonstrates an alternative way to shift the conflict and development dynamics. People’s collective efforts to extend invitations to local, national and international actors is slowly gaining weight. However, the absence of legitimate national actors and inconsistent behaviour of (international) actors makes inclusion easily said, yet hard to execute.

A different perspective on inclusiveness, trust, confidence, legitimacy, accountability, and transparency is presented in practise. Common people, in their search for a more just society show the way. They do not seek to replace other authorities and institutions. They aim for subtle shifts that create opportunities for a long term process. Expecting set backs along the way is included. To make this work, (inter)national actors have to be willing to engage and reinforce the connection to the everyday actions of people. This happened in some instances when national officials participated actively with local people. In these cases, all actors showed they play a constructive, leading role in shifting power dynamics. The inclusion and participation of diverse actor perspectives require time and presence to manifest what civic practice can entail.

6.5 Concluding: inclusiveness fosters diverse perspectives and collective action

‘What are the perspectives of Libyans on conditions for actor selection and participation that contribute to civic practice in times of crisis?’ I demonstrate in this article how Libyans began to see and use inclusion of diverse actors as a critical component for pursuing just development. Even in times of crisis the engagement between various actors is seen as valuable, between people in communities, with local or national authorities, institutions and intra-communal. This process is led by people, who acknowledge and value the different qualities and power positions to make room for pockets of development.

The manifestations of civicness are grounded in the values and customs in Libya. This way, people demonstrate their belonging and reinforce their legitimacy to be part of the public authority. The social-moral discourse and action helps to unite people. The findings suggest that collective civic practice emerges, led by inclusive conglomerates of people. Civic practices differ from democratic practises, which are concerned with democracy’s processes and structures. Instead, civic behaviours reinforce the exercise of rights and the responsibilities that come with them. People understand how to use them in relation to other actors. The emergence of civicness in the occurring dynamics of actors paves the way for practical changes in for example the right to assembly, collaboration between women and the police and openly sharing information.

A fresh approach to diminishing conflict and promoting well-being can gradually grow, even during (post-)conflict and times of crisis. The emerging civic practice merits additional support, examination, and practise. The findings in this study suggest this can be done simultaneously and in various ways.

1. Examine and support the practise of people, more or less organised in inclusive conglomerations of actors striving to reduce conflict, and what (un)learning this necessitates for those involved in developing and implementing (external) interventions.

2. Examine what ambitions and approaches of (Libyan) actors as used in practise contribute to the balance between the various logics.

3. Combine practical support for inclusive cooperation amongst players in Libya and abroad with an examination of how partnerships between different actors can flourish.

Data availability statement

Raw data is only available upon request and if the privacy of mentioned people is upheld.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Research Ethics Committee International institute of Social studies. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

A-MB: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^This has been measured in the first 100 SHARP reports, based on the indication provided in the report by a facilitator and discussed during evaluation of the dialogues.

2. ^(https://www.icj.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/ICJ-Libya-Repressive-Frameworks-Continued-Attacks-EN.pdf; https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/04/18/libya-crackdown-nongovernmental-groups).

3. ^https://libyaherald.com/2023/04/libyan-organisations-call-on-authorities-to-stop-draconian-laws-and-civil-society-crackdown/

References

Amnesty International (2020). Libya: Oral statement at the UN Human Rights Council on Libya (Item 10: Interactive dialogue on the High Commissioner’s Report on Libya, 43rd regular session)—Amnesty International. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde19/2541/2020/en/ (Accessed June 12, 2023).

Andrews, M., Pritchett, L., and Woolcock, M. (2017). Building State Capability: Evidence, Analysis, Action. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Autesserre, S. (2014). Going Micro: Emerging and Future Peacekeeping Research. Int. Peacekeep. 21, 492–500. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2014.950884

Autesserre, S. (2017). International Peacebuilding and Local Success: Assumptions and Effectiveness. Int. Stud. Rev. 19, 114–132. doi: 10.1093/isr/viw054

Beetham, D. (2008). Assessing the Quality of Democracy. Netherlands: An Overview of the International IDEA Framework.

Bell, C. (2019). New Inclusion Project: Building Inclusive Peace Settlements (1365–0742). Andy Carl (ed.) Negotiating inclusion in peace processes (Accord 28, Conciliation Resources, 2019).

Biekart, K., and Fowler, A. (2022). A research agenda for civil society: Overview and introduction. In K. Biekart and A. Fowler (Eds.), A Research Agenda for Civil Society Edward Elgar Publishing. 1–14.

Boege, V., Brown, A., Clements, K., and Nolan, A. (2008). On hybrid political orders and emerging states: state formation in the context of “Fragility” (8). Available online at: https://berghof-foundation.org/library/building-peace-in-the-absence-of-states-challenging-the-discourse-on-state-failure (Accessed October 20, 2022).

Cornwall, A., and Eade, D. (2010). Deconstructing Development Discourse. Rugby, UK: Practical Action Pub.

Crocker, D. (2014). Development and global ethics: five foci for the future. J. Glob. Ethics 10, 245–253. doi: 10.1080/17449626.2014.969441

Dasandi, N., Laws, E., Marquette, H., and Robinson, M. (2019). What does the evidence tell us about ‘thinking and working politically’ in development assistance? Polit. Govern. 7, 155–168. doi: 10.17645/pag.v7i2.1904

Debiel, T., Held, T., and Schneckener, U. (2016). Peacebuilding in Crisis: Rethinking Paradigms and Practices of Transnational Cooperation (Routledge Global Cooperation Series). 1st Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Della Porta, D. (2020). Building bridges: Social movements and civil society in times of crisis. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 31, 938–948. doi: 10.1007/s11266-020-00199-5

Drydyk, J., and Keleher, L. (2020). Routledge Handbook of Development Ethics. 1st Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Forsyth, M., Kent, L., Dinnen, S., Wallis, J., and Bose, S. (2017). Hybridity in peacebuilding and development: a critical approach. Third World Themat.: TWQ J. 2, 407–421. doi: 10.1080/23802014.2017.1448717

Fritz, V. (2007). Development Differently: Understanding the Landscape and Implications of New Approaches to Governance and Public-sector Reforms. In Transformation, Politics and Implementation. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. 75–98.

Glasius, M. (2018). What authoritarianism is… and is not:∗ a practice perspective. Int. Aff. 94, 515–533. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiy060

Glasius, M. (2023). Authoritarian Practices in a Global Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press eBooks.

Goulet, D. (1997). Development ethics: a new discipline. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 24, 1160–1171. doi: 10.1108/03068299710193543

Human Rights Watch. (2023). Libya. Availbale online at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2023/country-chapters/libya (Accessed June 12, 2023).

Ibrahim, S. (2017). How to Build Collective Capabilities: The 3C-Model for Grassroots-Led Development. J. Hum. Dev. Capabil. 18, 197–222. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2016.1270918

Jabri, V. (1996). Discourses on Violence: Conflict Analysis Reconsidered. Manchester, UK: Manchester Univ Pr.

Kaldor, M. (2020). Evidence from the conflict research programme—submission to the integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy. Conflict Research Centre. Available online at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/106522/

Kaldor, Mary, Theros, M., and Turkmani, R.Conflict Research Programme (2021). War versus Peace Logics at local levels: Findings from the Conflict Research Programme on local agreements and community level mediation. Conflict Research Programme.

Kaldor, M., and Radice, H. (2022). Introduction: Civicness in conflict. J. Civ. Soc. 18, 125–141. doi: 10.1080/17448689.2022.2121295

Khalifa, A.Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (2022). FES MENA Youth Study: Results Analysis. (YOUTH IN LIBYA), FES MENA Youth Study: Results Analysis. Available online at: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/libyen/20080.pdf

Lederach, J. P. (2019). New Inclusion Project: Forging Inclusive Peace (1365–0742). Negotiating inclusion in peace processes (Accord 28, Conciliation Resources, 2019). ed. A. Carl.

Lilja, J., and Höglund, K. (2018). The role of the external in Local Peacebuilding: Enabling Action—Managing Risk. Glob. Govern. Rev. Multilater. Int. Organ. 24, 411–430. doi: 10.1163/19426720-02403007

Loschi, C., and Strazzari, F. (2018). Working paper on implementation of EU crisis response in Libya. EUNPACK. Available online at: http://www.eunpack.eu/publications/working-paper-implementation-eu-crisis-response-libya (Accessed, June 12, 2023).

Mac Ginty, M. R. (2011). International Peacebuilding and Local Resistance: Hybrid Forms of Peace (Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies). 2011th Edn. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mac Ginty, M. R. (2021). Everyday Peace: How So-called Ordinary People Can Disrupt Violent Conflict (Studies in Strategic Peacebuilding). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mac Ginty, M. R., and Williams, A. (2016). Conflict and Development (Routledge Perspectives on Development). 2nd Edn. London, UK: Routledge.

Mac Ginty, R, and John, A-W. (2022). Contemporary Peacemaking: Peace processes, Peacebuilding and Conflict. Palgrave Macmilan.

Mac Ginty, R., and Richmond, O. (2015). The fallacy of constructing hybrid political orders: a reappraisal of the hybrid turn in peacebuilding. Int. Peacekeep. 23, 219–239. doi: 10.1080/13533312.2015.1099440

Parks, T. (2016). ‘Fragmentation of the Thinking and Working Politically agenda: Should we worry?’ DLP Opinions.

Pett, J. (2020). Navigating Adaptive Approaches for Development Programmes (589). London, United Kingdom: ODI.

Richmond, O. P. (2013). Failed statebuilding versus peace formation. Coop. Confl. 48, 378–400. doi: 10.1177/0010836713482816