- Universidade de Lisboa, Institute of Social and Political Sciences, Centre for Public Administration and Public Policies, Lisbon, Portugal

This study, grounded in an anticipatory approach and viewed from an agenda-building perspective, explores the role of the press as a key player, especially in the context of the Russia–Ukraine war. The central research question is: how can communication and the press play a role during war to break a reactive response cycle? The anticipatory approach has proven highly valuable in many fields, especially when addressing the urgency of several policy domains that require greater evidence and research. Communication, particularly the role of the press during a war, can be seen as the final layer perceived directly by the population. The agenda-building approach has been key in understanding news-making processes. From an anticipatory perspective, analyzing media coverage allows for the examination of the inter-influence between policymakers, decision-making outcomes, and various social and media agents. Methodologically, this study applies the content-analysis technique to a selection of Portuguese newspapers (daily and weekly) covering the period from 2014 to 2023. The criteria for selecting news articles included those providing political and strategic information regarding the Ukraine war, with references to international organizations, European Union actors, and Russian and Ukrainian actors. The expected results aim to provide empirical evidence of the relationship between different regimes and how policymakers and political processes are dynamically positioned for future actions, considering the role of the press.

1 Introduction

Information has always played a significant role during wars and conflicts. It facilitates contact between ordinary citizens and key players in each region, territory, nation, and state involved in a conflict. Various interests—mainly political and financial—are often active in conflicts, and information may sometimes be directed by the parties involved in the conflict. This is particularly true for democracy and decision-making processes (Bezold, 1978; Caillol, 2012; MacKenzie et al., 2023) as well as in the context of war (Hegre, 2014)—a complex domain that encompasses multiple factors such as human capacity for vision, creative thinking, strategy, politics, governance, communication, information, and so on. However, despite the expectation of impartiality and ethical rigor, complete neutrality in journalism can be challenging, especially in conflict coverage. This is one of the main journalistic challenges in conflict coverage, considering the international consequences and impacts of war—economic, political, and social. Despite the expected rigor in the press of free and democratic states, agenda-building plays a key role in shaping political regimes and is an essential player in a war.

From an anticipatory studies perspective, we argue that agenda-setting processes provide valuable insights into the inter-influence between policymakers, decision-making outcomes, and various social and media agents.

Warlike conflicts are fought on battlefields, where tactics and geo-strategy, strategic intelligence, security, and diplomacy develop and are executed. However, the press also plays an important role in war. This research, grounded in an anticipatory approach and considering an agenda-building perspective, has the following main objectives: to identify the essential communication scope, trends, main subjects, and players in the Portuguese press in a politically and strategically anchored vision from 2014 to 2023; to examine the political position of the European Union (EU) on the war in Ukraine and the political links between various political players as reflected in the Portuguese press; and to examine the news tone and press coverage of the international position on Ukraine from a Portuguese perspective. The central research question is as follows: how can communication and the press play a role during war to break a reactive response cycle? In methodological terms, this research is based on the content analysis technique applied to a selection of Portuguese newspapers (daily and weekly) covering the period from 20 February 2014 to 31 July 2023.

2 A brief chronological note on the narrative events of the war in Ukraine

The Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 was a corollary of a sequence of military operations that were being developed in a progressive Russian military positioning close to the Ukrainian borders in Belarus, Russia, and Crimea. The open conflict between Russia and Ukraine was evident, at least since the Russian annexation of Crimea in March 2014. This came shortly after the end of the Euromaidan movement, on 21 November 2013, and lasted approximately 4 months. This movement sought the resignation of the pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych, the assumption of measures against corruption in the government, and the inclusion of Ukraine in the EU. Several references have discussed a dimension of this conflict, considering a hybrid war, predominant since 2014, restrictive to military tactics and operational strategy, even considering guerrilla, subversive, and insurrectional tactics (Snegovaya, 2015; Mölder and Sazonov, 2019, 2018; Prokop, 2023). On the other hand, and alongside this perspective of war, we find the use of another dimension that is based on “information warfare forms” and “an influential part of this non-linear strategy” (Mölder and Sazonov, 2018), particularly in the Donbas conflict. In this case, the information warfare tools and technology helped construct a narrative to support a national sense of legitimacy and justification of the conflict.

The Russian intervention and the military takeover of Crimea and Sevastopol in March 2014, and the holding of a “referendum” on “Russian reunification,” aimed to legitimize the annexation of Crimea from the perspectives of the Russian Federation and Armenia, Bolivia, Belarus, North Korea, Nicaragua, Syria, Sudan, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe. Crimea's “political transfer” to Ukraine in 1954, while still part of the USSR, was not politically consensual. This measure was an initiative by Nikita Khrushchev—he was of Ukrainian origin—and was misunderstood and disapproved by several Russian factions. This transfer later became one of the most publicized historical justifications for the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation in 2014. From this perspective, Crimea's annexation is seen as a return to the “Russian homeland,” in line with what is presented as a “historical and legal Russian design.”

The war in the Donbas region, which started in March 2014, was triggered by a pro-Russian rebellion by local pro-independence groups. As in Crimea, these groups comprise a majority of Russian speakers who culturally identify themselves as Russians. However, with this annexation, Russia violated the legal principles of the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, which prohibits changing Europe's territorial borders through force. Additionally, Russia violated the 1994 Budapest Memorandum on Security Guarantees, which provided for the independence and territorial integrity of Ukraine, as well as Belarus and Kazakhstan, in exchange for surrendering to Russia and abandoning nuclear weapons.

Russian political support for the Donbas region culminated with Putin's recognition, in February 2022, of the region's independence on the eve of the so-called Russian “special military operation.” This “operation” was justified and considered essential by Putin based on arguments such as the demilitarization and denazification of Ukraine.

These arguments are forcefully presented in Russian media as logical, historical, and cultural justifications, framed primarily as necessary for the defense and protection of Russia. This was intended to preempt the imminent attack on Russia by the USA—the oft-articulated, oft-insinuated omnipresent enemy in Putin's speeches. Additionally, these justifications aimed to promote the national legitimacy of the impending invasion of Ukraine among the Russian population. Plokhy (2015, 2023) emphasizes historical events and imperial collapse as the principal reasons why Russia has never really accepted cultural fragmentation. In the same vein, Mölder (2021) highlights the “culture of fear” theory, based on the myth of a declining Europe opposed to the still resistant Russian virtues.

Cultural and linguistic ties between Russia and Ukraine have been important political assets in this conflict. There have been different positions and evolutions regarding Ukrainian as a state language, mainly since the end of the nineties. According to the Ukrainian 2001 census, Russian was the second most spoken language in Ukraine after Ukrainian, with over 14 million Ukrainians speaking this language. The importance of the Ukrainian language was guaranteed by the 1996 Constitution, which formalized Ukrainian as the official language. However, it also guaranteed the use of Russian and other languages by national minorities in Ukraine. This was never a peaceful or consensual decision. It was partially questioned and reversed when 2012, during Yanukovych's Presidency, a law allowing bilingualism in certain regions was enacted. After the overthrow of his government, the Ukrainian Parliament repealed the law. In 2018, the Verkhovna Rada reinforced the decision, following a law from the Constitutional Court of Ukraine. Furthermore, in 2019, the Ukrainian language was legally defined as the state language.

The personification of political decisions has been a characteristic of Putin's mandate (as happened with most of his predecessors). The state controls the propaganda machinery and communication campaign based on nationalist principles and a strong historical identity. These principles revert to the ancestral idea of a post-revolutionary Russia, politically planned and ideologically united, despite being composed of “multiple nations”—and, in Putin's words, being supported by different but solid cultural ties, which promote Russia's progress.

Ukraine and Russia are significantly involved in constructing the war narrative. The fourth power can only be truly immune to the pressures of the political stages and arenas, where conflicts are installed when there is still a democratic safeguard (the one that derives from the power of the people). The power of information resembles a polyhedron that mirrors, with a greater or lesser range of focus and light, the dimensions of the objects/contents that capture or are allowed to capture, explained in an agenda-setting hypothesis. Its framing depends on contexts, civic and political cultures, and the ability to decode.

The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology conducted a survey from 3 May to 26 May 2022 examining the sources from which Ukrainians gathered information during the war. It was commissioned by OPORA. The results referred to the previous 2 months. The results indicated that social networks emerged as the most popular source of information (76.6%), followed by television (66.7%) and the broader Internet (excluding social networks) (61.2%). Only 28.4% of respondents obtained information by listening to the radio, and a small share of 15.7% used the press (OPORA Report, 2022, p.3).

Currently, the main Russian public channel, Channel 1 (Первый канал, Pervyy kanal), airs a highly rated daily program (Time will tell—время покажет – vremya pokazhet) in which several guests discuss the “special operation in Ukraine.” The program is characterized by the assertive tone of the presenter and the enthusiasm of certain guests, in accordance with the motto and theme of each program (normally centered on current international news and with international guests, including Americans). Since the beginning of the so-called “Russian special operation” (as is known, the term “war” cannot be used in Russia), this program has highlighted the factors that Russia considers as legitimate reasons to launch the conflict: safeguarding Russia against the “Ukrainian Nazi forces” that are “installed in Ukrainian power and society” (Russia has given the example of Ukraine's national hero, Stepan Bandera, as an exponent of Ukrainian extremism). It emphasizes and justifies the hypothetical separatist “right” and the conflict in the Donetsk and Lugansk regions, which has lasted since 2014 and would have provoked the “genocide” of the Russian populations in these regions without the “West caring.” Military intervention in Ukraine is justified in light of separatist “law” in these regions. Russian “military operations” are focused and justified, some of which are not even reported in the West, and Ukraine is blamed for Russian intervention. Information in the Russian public domain does not encompass the extent of the conflict, the level of human suffering, the displacement of millions of people, and the destruction of Ukraine. Dissidents of the regime essentially consider the information broadcast on Russian channels as propaganda. They are proven right by the limited and selective news coverage. Additionally, it is a crime if journalists and other citizens transmit messages “subversive and contrary to the Russian order.”

In Ukraine, broadcasts are mainly from two television channels, and the other channels merely retransmit. They inform the public about the progress of events and play videos published by President Zelensky on social media. Twitter—now renamed X—is the most used means of communication to communicate with the Ukrainian population and the international community. Its daily intervention focuses on appeals for the support of the international community in strategic and economic visions and, in particular, at a time when the economic sanctions against Russia worsen. Zelensky's popular, emphatic, and emotional communication style increased his political popularity and contrasted with Putin's distant, seemingly “neutral,” cold, and institutional style. Zelensky enjoys the full support of the Ukrainian media (mainly television), which convey his messages as acts of resistance and heroism, not propaganda.

The Portuguese press mainly depends on direct/ground sources embedded in the battlefield, in addition to the daily reports published by Zelensky and information provided by Putin and the Kremlin. Additionally, specialists in military matters and international relations help decode this information and comment on the dynamic war situations.

In a democracy, politicians are elected by performing their roles publicly. Negrine and Stanyer (2007, p. 72) argue that politicians become “recognized performers” and “intimate strangers” at the same time. In this sense, the press has played a key role despite the crucial contributions of social media (Blumler, 2001).

3 The fourth power and agenda-building from an anticipatory perspective

Power is added to the battlefront, already stated as the fourth, in addition to Montesquieu's three classics, in his De l'Esprit des Lois, published in Geneva in 1748 without the author's name to circumvent censorship and protect the author. Montesquieu (1748/2003) dealt with different forms of government (monarchy, aristocracy, republic, and despotism) and their laws and reflected on the need to separate the three essential powers of the state: laws, governance, and justice. A fourth would be added to the three fundamental powers of the state—a power that, in its ideal dimension and mission of equidistance and distancing between powers, would more closely resemble a “counter-power.” In terms of its meaning and fundamental role, in the 19th century, the functionality of the fourth estate gained prominence from the thinking of Macaulay (2004), supposedly in 1828, referring to the role of the guardian of the citizen press against an abusive and autocratic power. The press would be the counter-power or the true power, representing all citizens and allowing the balance of power suffocated by few in the 19th century, emanating from parliaments. However, the information and press powers could only maintain their autonomy and reliability when executed in an impartial, independent, informative, non-ideological or manipulated manner by any other power, especially the executive power. Carlyle (1866/2013) defended the role of the press to achieve a more inclusive society.

From an agenda-building perspective, politics is far from being a central issue for most people, and “rather than seeking out diverse sources of information, people tend to screen out potentially dissonant information and perceive political stimuli selectively in terms of preconceived notions” (Cobb and Elder, 1971, p. 897). Referring to this introductory study from Cobb and Elder (1971), applied to political content in the media, agenda-building refers to a process that studies why content and sources are selected and included in media decisions and, consequently, in the news. From another perspective, McCombs and Shaw (1972)'s seminal contribution to agenda-setting introduced a key milestone in media studies by referring to and focusing on the effects of the media agenda on the public agenda. In other words, although the two processes are closely interconnected, the construction of agenda-building precedes the agenda-setting process and allows an essential angle in observing media options prior to and based on the media-building agenda. According to Vu (2020), “the agenda-building approach refers to the process in which salience of an issue is formed in the news agenda through reciprocal interactions between actors, including the news media, the public and political figures.” Only after the agenda-building process occurs does agenda-setting occur. Thus, agenda-building options influence the public agenda and the way the public perceives news agenda options. This is why, when considering the agenda-building process, one can infer the salience of an issue and the reciprocal interactions between actors, including the news media, the public, and political figures (Vu, 2020).

The study and perspective of agenda-building facilitate a dynamic internal examination of the media and enable explanations based on the source and content of the media agenda choices. From this perspective, the use of specialized sources in journalism introduces a different level of credibility and a deeper angle of analysis and salience of an issue. An example of this highly systematic use was studied by Lopes et al. (2023) on journalistic coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Higher levels of specialization and knowledge on the part of readers lead to greater use of specialized sources in the press. Several studies on the role of specialized sources highlight their relevance in political and social terms (Boyce, 2006; Berkowitz, 2009; Albæk, 2011; Fisher, 2018).

There is a key distinction between anticipatory and anticipative approaches. Referring to the latter, Rosen (1985)'s seminal contribution reinforced that “what differentiates living systems and inorganic systems is anticipation.” In other words, anticipation refers to an adaptive strategy of a living system. Following Rosen's contribution and clarifying the meaning of anticipation, Dubois (1998, p. 3) establishes a comparison between taking an umbrella on a winter day and participating in a conference: “This is the internalist anticipation. In the first case, the externalist anticipation is dependent on the environment. In the second case, the internalist anticipation creates its own future events and manages to meet these anticipated events.”

Rosen (1985, p. 341) argues that the anticipatory approach is “a system containing a predictive model of itself and/or of its environment, which allows it to state at an instant in accord with the model's predictions pertaining to a later instant.” Those are usually “reflexive political systems,” which are participative and deliberative, unlike the vision and approach of a “reactive political system” based on “reactive control” (Voinea, 2023). These two approaches bring two different interaction paradigms between the citizens and the government: a reactive system (based on influence vs. responsiveness) and a complex system (based on participative and deliberative decisions).

Following the systemic model and a self-observation approach, Dubois and Sabatier (1998) and Dubois (1998, 2002) studied the political system from a “cybernetic” and “computing anticipatory systems” perspective. Dubois (1998, p. 3) considered, “What means computing anticipatory systems for systems without a conscious and intentionality? The why no longer exists. The show is the subject of science in explaining natural systems by using mathematical models, for example. However, the question is, why is philosophy a subject.” Science transforms the why into the how by recursive arguments. Until now, only recursive functions are computable by artificial devices, such as computers.

Three key elements contextualize the political system, political culture, and the dynamics and scenarios of political participation, helping to define which political models and expectations can be developed in the future. In other words—and according to a perspective where the political system can be viewed as an open (democratic) system (Easton, 1957, 1965; Fuchs, 2004)—inputs and outputs are as dynamic as interactions, and the structural organization of each context flows and develops. Knowing the characteristics and perceiving the internal dynamics of a system, the anticipatory approach provides or aims to provide elements about “future desirable state(s)” (Voinea, 2023). This is explained by the mathematical model applied by Voinea (2023), considering “reflexive systems” and political culture as a “complex system with anticipatory capabilities which are acquired from the complex evolutions of its internal models,” considering the parameters, “anch(t),” “v(t),” and “att(t).” This is applied to study the political participation scenario based on the “value mappings and anticipatory methodology.” In Voinea (2023)'s contribution, the question was: How to facilitate the emergence of future (desirable) states? The hypothesis was confirmed as “all systems include internal models,” based on the following interpretation: “The political culture may achieve a desirable state by identifying the desirable number of participants, the desirable attitude toward ‘policy' or ‘government,' or the desirable (shared) aim of participants (deliberation).” This contribution was based on “a content-based anticipatory methodology aiming to acquire (self)reflexivity and identify what is ‘desirable' state in the anticipatory system.” One of the main arguments of Voinea's (2023) contribution defends resilience as a means “against public threats, security threats.”

Following an anticipatory approach, research on democracy and decision-making processes (Bezold, 1978; Caillol, 2012; MacKenzie et al., 2023) examines the complexity of power structures, particularly highlighting people's ability to develop rational solutions through information and communication as key tools for political decision-making. Democratic processes were also questioned during the war (Hegre, 2014), causing additional challenges regarding future studies and anticipatory approaches. Considering democratic states, the author argues that they have a “lower risk of interstate conflict than other pairs hold up” (Hegre, 2014, p. 159), which should also be considered when combined with pre-existing socioeconomic conditions and “democratic institutions.” This is the case of the current context under analysis: Ukraine, which is a young democracy (Maoz and Russett, 1992), where we find economic (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2006) and social discontent (Eck and Hultman, 2007) in a corrupt context under a strong influence of Russian culture and politics, particularly until 2014.

The pillars of the democratic state of law are supported by the power of information, which is its permanent mission of monitoring powers. The question is: what is the power of the press when the space of the people, owing to imperative circumstances, is subtracted and replaced by the martial imposition of the state? This research focuses on the options for agenda-building of the press and how these constitute, although of political interest, a key tool that should be viewed as having an anticipatory role, considering that information enables sustained decisions if employed as a political tool for the public interest.

4 Methodological note

Methodologically, this study applies the content analysis technique to a set of selected Portuguese (daily and weekly) newspapers from 20 February 2014 to 31 July 2023.

The date of 20 February 2014 is significant because it marks a milestone event: during his visit to Moscow, the President of the Supreme Council of Crimea, Vladimir Konstantinov, stated that the transfer of Crimea to Ukraine in 1954 was a mistake. Regarding the content analysis, first, we intended to include two phases: from 20 February 2014 to 23 February 2022 (when the conflict was restricted to Crimea and some parts of the Donbas region) and from 24 February 2022 to 31 July 2023 (after the Russian invasion of eastern Ukraine). The data available from April 2014 to January 2022 were scarce.

Due to the scarcity of data from April 2014 to January 2022, we decided to exclude this period and focus on data from before and after this interval. The 31 July 2023 has no historical or symbolic value: only a parameter of convenience (considering that the war continues thereafter).

The news corpus totalizes 1,036 newspapers and 106 journalistic pieces. The news selection criteria strictly consider the articles that focus directly on the political and strategic information regarding the war in Ukraine, referring to international organizations and EU actors, together with the Russian and Ukrainian actors.

The selected newspapers include national and reference dailies (Diário de Notícias and Público) and weekly newspapers (Expresso).

These were selected as reference newspapers with a wide readership among the general public. Data were collected from the digital versions of the periodicals.

Content analysis is based on Bardin (2004)'s methodology, focusing on categorical and quantitative types, ensuring mutual exclusivity and homogeneity of the categories. The categorization process follows a systematic procedure derived from the research objectives. These objectives are used as a starting point to identify the appropriate categories and indicators for the analyzed content. The research units that support the organization of the categorical sets are “words” and “theme,” following Bardin (2004)'s approach. The lexical framework and criteria for organizing the research included a set of words, including “war in Ukraine,” “conflict in Ukraine,” “Ukraine,” “Ukrainians,” “Zelenksy,” “Russia,” “Putin,” and “Donbas.” The use of images on page covers that suggested the conflict scenario was also a criterion for including the news pieces.

Additional criteria for the lexical search required that news titles include at least one of the words or word combinations from the defined lexical set and that the article content and meaning be directly related to the conflict and war in Ukraine within the period considered.

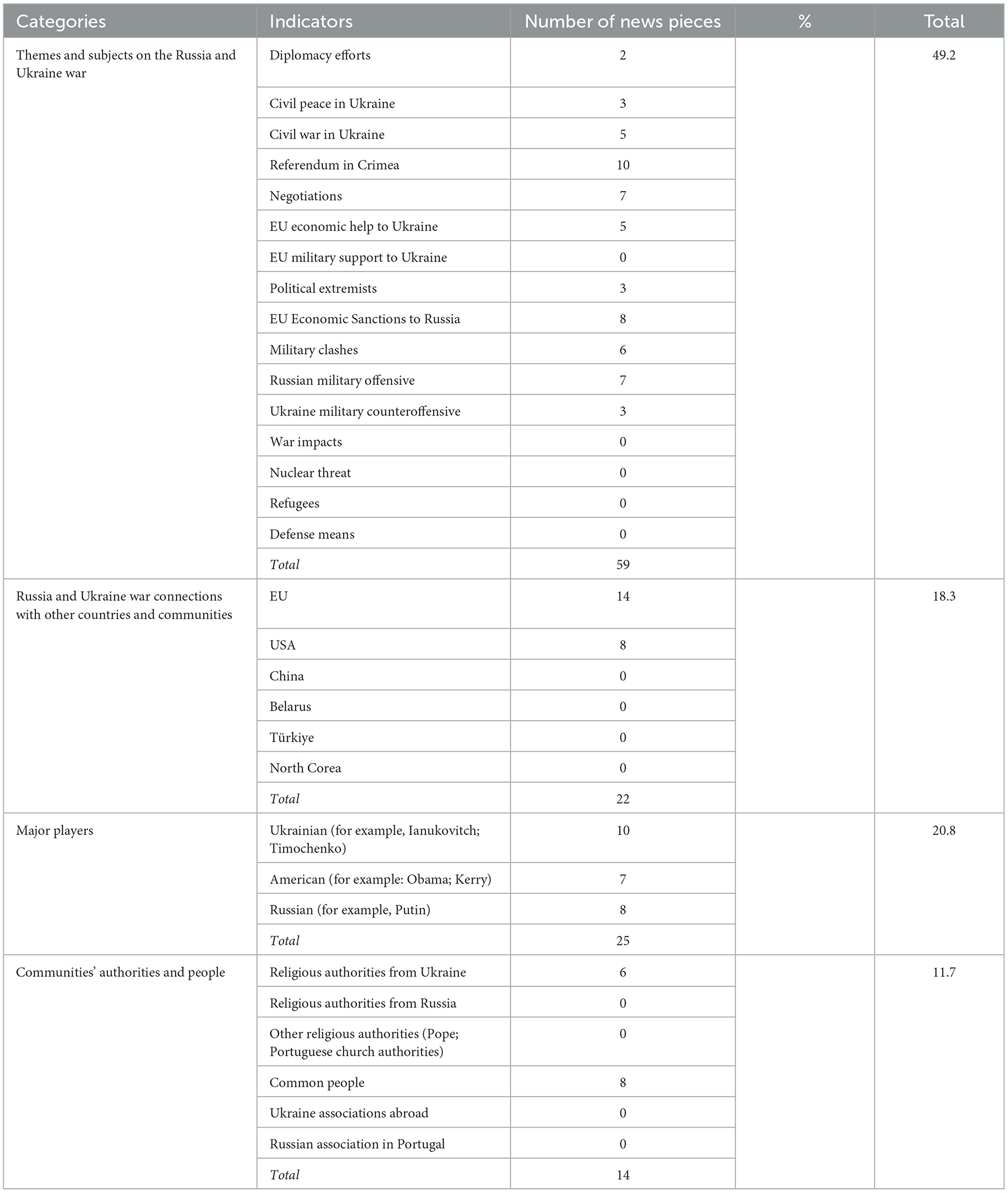

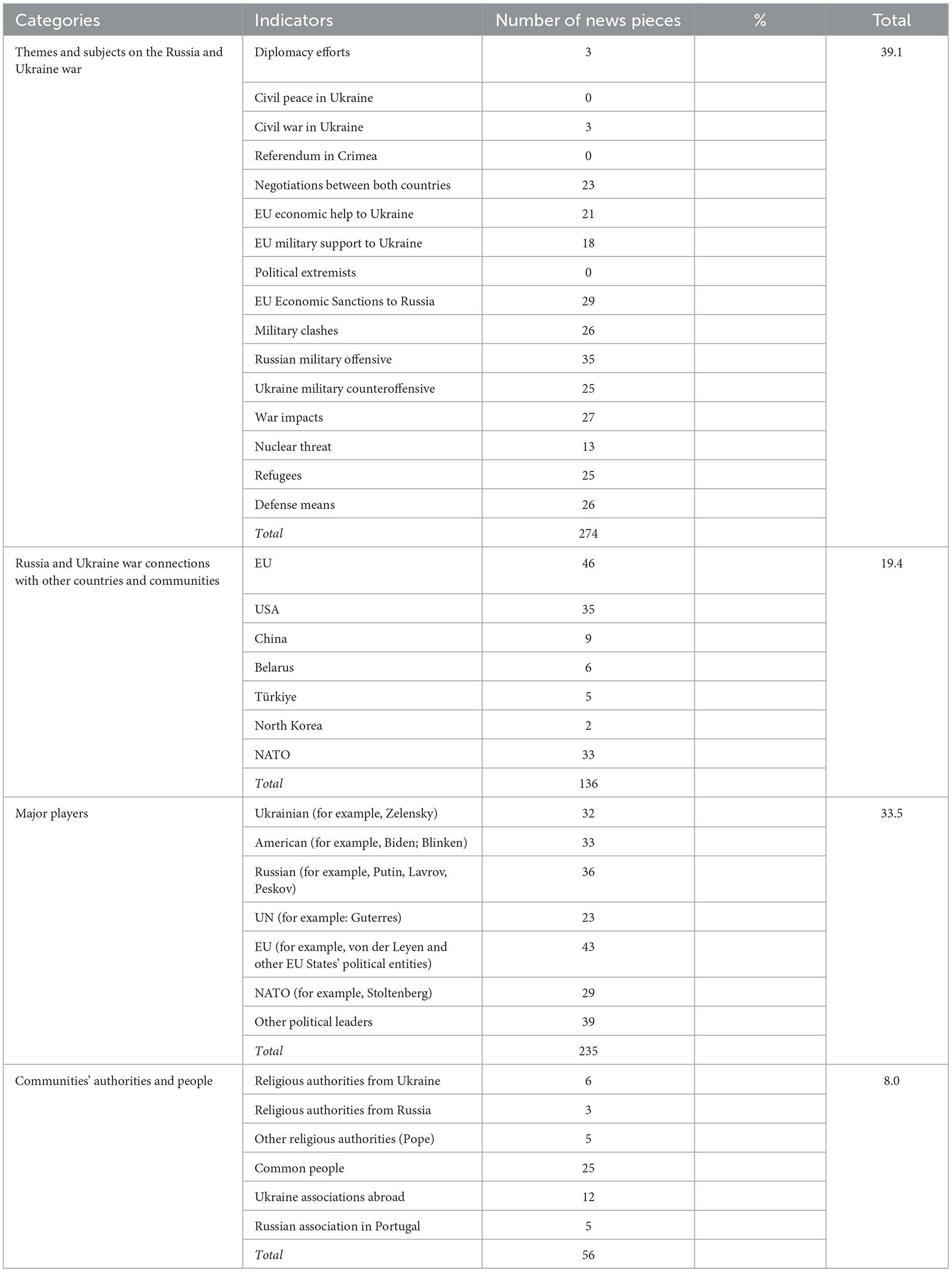

The first thematic axis characterizes the news corpus. And defines the main themes, based on four macro-categories: themes related to Russia and the Ukraine war, Russia and Ukraine war connections with other countries and communities, and community authorities. The identified indicators and categories are presented in Tables 1, 3.

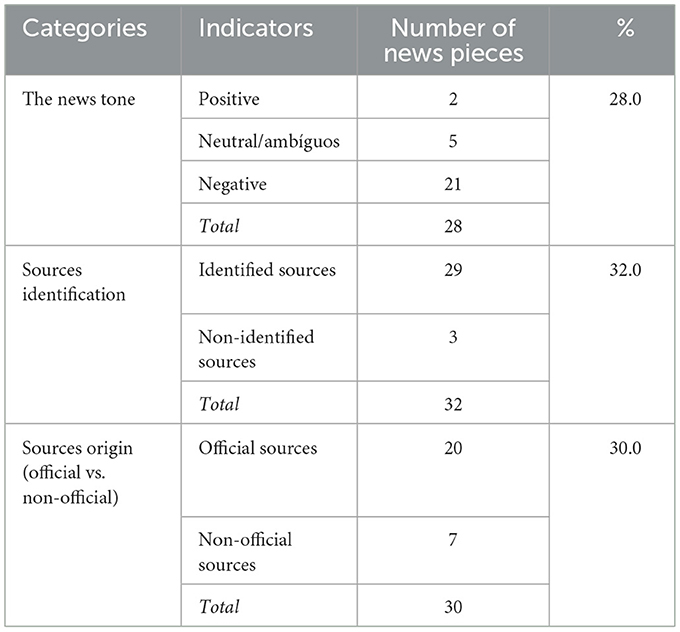

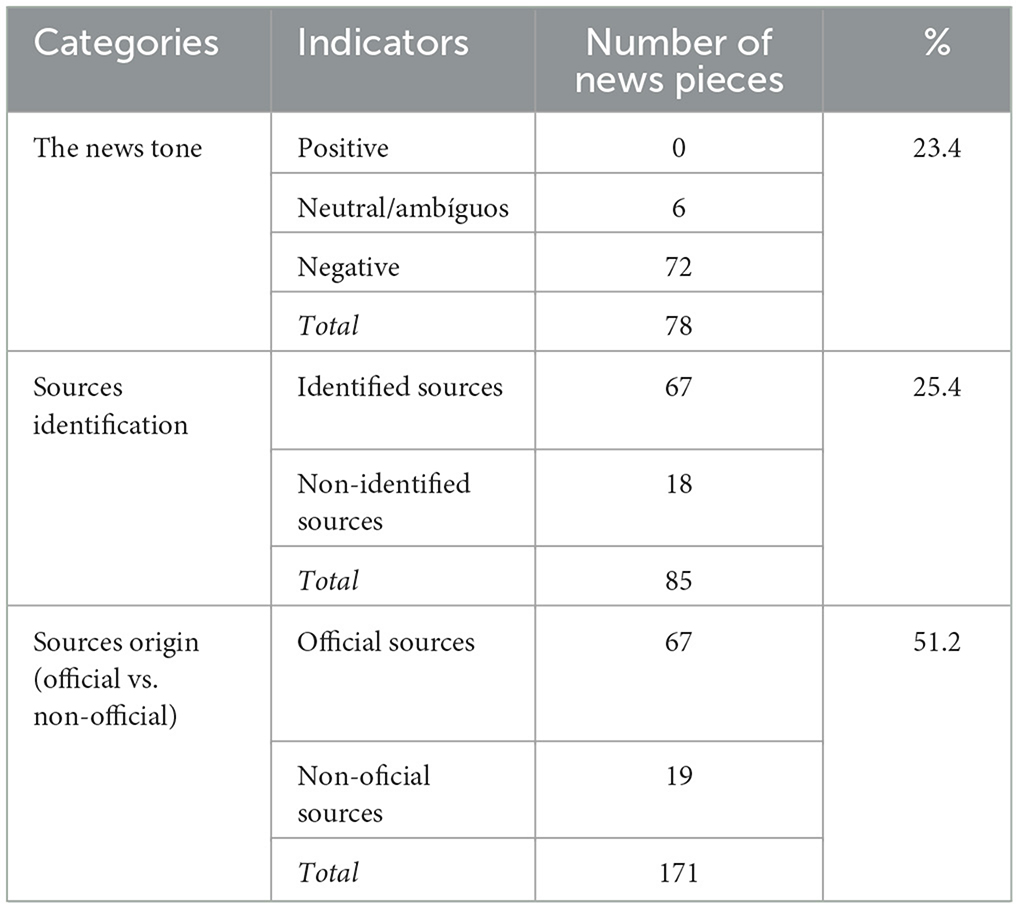

The second thematic axis focuses on the tone of the news and press coverage regarding international positions on the Ukraine war. It is based on two macro-categories (see Tables 2, 4): the tone of the news and the use and type of sources. Each category includes several indicators: positive, neutral, and negative tones; use of identified or non-identified sources; and use of official and non-official sources. The planning for the codification of categories and indicators was based on the “miles” approach (Bardin, 2004), where the data obtained and the objectives defined guided the framing and criteria for codification.

Table 2. The news tone and the press covering the international positions toward the Russia-Ukraine war (2014).

5 Content analysis of the Portuguese press on the Ukraine war (February 2014–July 2023): analyses and discussion

The press content analysis for 2014–2023 facilitated a diagnosis based on news criteria selection due to agenda-building processes and editorial decisions. Based on the anticipatory approach, the results provide the required support for further analysis and discussion.

As mentioned above, the objectives of the research are as follows: to identify the essential communication scope, trends, main subjects, and players in the Portuguese press in a politically and strategically anchored vision from 2014 to 2023; to examine the political position of the EU on the Ukraine war and the political links between the various political players based on the Portuguese press analysis; and to examine the news tone and press coverage of the international position on the Ukraine war, from a Portuguese perspective. The research question is as follows: how can communication and the press play a role during war to break a reactive response cycle?

The analysis did not include a follow-up between 2014 and 2023, despite the beginning of the conflict in 2014. We may concentrate on the news regarding the beginning of the conflict in February and more rarely in March 2014, and very few references to the conflict in Ukraine in the following months of 2014. Between 2015 and January 2022, the number of references to the Ukrainian conflict meeting the defined criteria is scarce in the press. Therefore, Table 1 is centered on the data available in 2014 in the selected newspapers. Another observation is that compared to daily newspapers, the interest of the weekly newspapers in the war is lower when compared to the reference to the war in the cover news pieces. Despite the inclusion of a few articles in weekly newspapers, these news pieces were not always highlighted on the cover page.

Front-page images from a few of the selected newspapers (see set of Images 1, 2, and 3) illustrate the strong public effect sought by the press by covering at least the 1st days and weeks of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The images accompanying the news about this war cover more than half a page and are impressive and emphatic, engendering emotional, and political effects.

Regarding content analysis, when analyzing the two temporal phases observed, we identified that in 2014 (see Table 1), the “Referendum in Crimea” was, by far, the most covered topic in the press, followed by “negotiations” and the “Russian military offensive.” “Diplomatic efforts” were rarely covered. In terms of the most cited contexts, we identified “EU,” followed by the “USA.” “Ukrainians” and “Americans” are the most mentioned “major players.” “Common people” is the most significant indicator in the “communities” authorities and the “people” category.

Table 2 reveals the predominance of the “negative/ambiguous” tone, “identified sources,” and “official sources.” These trends are confirmed by similar research on the news coverage of political entities, particularly regarding health issues (Araújo and Lopes, 2014) and the coverage of Ukraine's President's actions and speech interventions (Espírito Santo and Lopes, 2019). The predominance of “official sources” is explained by their proximity to the media and the issues in question.

Compared with the second phase of analysis, Table 3, namely from 2022 to 2023, shows a significant difference in the newspaper coverage, which is the diversity of approach angles, most of which have a high score in terms of news interest. As Table 3 shows, this is the case with the following indicators, referred to as “themes and subjects”: “Negotiations between both countries,” “EU Economic sanctions to Russia,” “Russian military offensive,” and “war impacts.” Conversely, “diplomacy efforts” are rarely mentioned, just as they were rarely mentioned in 2014.

Table 3. Main trends: themes, subjects, and players in the Russia–Ukraine war, in press (2022–2023).

The observations in Table 4 follow the same trend identified in Table 2: the predominance of the “negative/ambiguous” tone, “identified sources,” and “official sources.” The negative tone is a predominant trend that follows a Western media trend, markedly exposing the scourge of war in a vivid manner via text and images. A significant conclusion is that the tendency shown by the Portuguese press in terms of lack of interest in covering the conflict in Ukraine, starting in 2014, may induce the conclusion that this topic was not significant enough from the European or even international perspective. The same did not occur after the military action on the Ukraine frontier in February 2022. Thereafter, the news coverage was daily, expansive, and nuanced in terms of journalistic and public interest. Looking back at 2014 and the following years and considering an anticipatory perspective, we may argue that the crucial signs were neglected in Portuguese/EU terms. They should have been considered significant from the EU perspective, and more fierce measures should have been adopted to contain the conflict. In the future, despite a reactive social and communication cycle and vision, one may experience a low interest in diplomatic efforts and greater attention to strategic and military means, which will predominate in war coverage from an agenda-building perspective.

Table 4. The news tone and the press covering the international positions toward the Russia–Ukraine war (2022–2023).

As previously mentioned, based on the anticipatory approach, the observation of the democratic system and decision-making processes (Bezold, 1978; Caillol, 2012; MacKenzie et al., 2023) reveals the complexity of powers. These are accompanied by people's involvement and participation based on information and communication as key reference tools for public opinion. This is a unique characteristic of the current communication process, which aims, in public terms, to promote the involvement of political democratic communities and the public sphere—in particular, within the scope of international political involvement. However, in a war situation, together with previously fragile democratic institutions, as is the case in Ukraine, these tools not only enable an extreme exposure of internal and external ties, support, and threats but also correspond to an ideal and desirable situation, aiming for a peaceful and strong institutional democratic state. This is one of the conclusions derived from this approach. This study follows the perspective of Voinea (2023) by highlighting the value of resilience as a means and response to “public” and “security threats.” Based on the available evidence, it is concluded that, despite the complexity of this war, there is a political vision based on a communication strategy that involves the international community, political actors, and the public sphere. This indicates a greater, long-lasting, large-scale conflict that requires resilience, and positioning of international players. Based on the research and from an anticipatory approach, responding to the research question (how can communication and the press play a role during war to break a reactive response cycle?), some steps and evidence exist. The EU has managed to maintain an option and vision of political union and expressed support for Ukraine and its integration into the EU. This indicates a strategic option of strengthening Ukraine politically, financially, and militarily by almost all Member States. The expansion of the EU to Ukraine could induce an expectation of political reinforcement of the European project, which could experience a new political impetus by combining efforts of a strategic nature despite the natural doubts inherent to the conditions of preparation and viability of Ukraine to integrate into the European project. However, the greatest challenge and risk will emanate from Finland and Sweden's accession to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). This could trigger a Russian military strategy of self-protection and self-justification of the expansion of defense/invasion/war against the potential dangers arising from the expansion of NATO next to its borders.

6 Concluding remarks

It is difficult to predict an outcome of this war that satisfies both parties, Russia and Ukraine, both proclaiming an eminent and irreducible position in terms of hypothetic future negotiations. Additionally, it is unlikely that this conflict will end within the next few years. However, all options remain open, especially if diplomatic channels and United Nations intervention are intensified.

The geopolitical effect of continuing this war would be a demarcation of positions in terms of support on the part of the states that share a direct economic and political relationship with Russia—especially China. Thus, depending on the support that Russia obtains, a greater distance and strategic positioning will be felt, with economic effects—on a European and global scale—in terms of energy, inflation, scarcity of raw materials and cereals, and food insecurity in territories dependent on Ukrainian agricultural production, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Additionally, there would be a general deterioration of the living conditions of the global population—more markedly in Europe—with a deep and persistent economic recession and the accentuation of the differences between the rich and the poor. The eventual change of the geopolitical balance and economic, diplomatic, and military relations resulting from the reorganization and emphasis on the role of NATO may potentially escalate this conflict, with drastic consequences for NATO members.

The recessive economic cycle of several states, including the richest countries, is one of the most immediate consequences, given the macroeconomic plan of interrelations and dependencies in terms of productive and commercial chains with China and the USA. Furthermore, in addition to the impact on production, there would be impacts on international trade, companies operating on a global scale, and the imbalance of financial markets. In other words, the escalation of the Russia–Ukraine conflict will accentuate the recession levels. This is due to the effects of energy production and distribution, interruption of production and distribution chains, and shortage of agricultural products, especially cereals. The aggravation of the recession will deepen people's economic and social gaps, with drastic humanitarian consequences.

The role to be played by Europe, China, and the USA will be crucial, especially if the diplomatic path is accentuated, given the alarming state of devastation, destruction, and economic slowdown. Diplomacy is the last—and probably the only—resource, especially if we consider the need to contain the possible indirect effects of other countries (such as the USA, via NATO), with irreversible consequences in a potential conflict escalation on a global scale. In other words, if diplomatic channels and the UN do not impose themselves on this war, achieving the expected peace and containment of the economic recession will be difficult.

The Europe–USA relationship rests on an axis of deepening a transversal and common ideal of defending the democratic ideals of freedom, equality, transparency, political scrutiny, and promotion of historical ties. However, regarding the geopolitical and geostrategic forums, there was not always convergence and support for the American policies of military intervention in international conflict scenarios, which led to some isolation and distancing of some European States in relation to the strategic options of the USA and especially within the NATO. This war helped revitalize the meaning of the Atlantic Alliance concept, hopefully, now with a greater sense of geostrategic sharing and scrutiny of NATO's military options.

The power of communication, combined with the mobilization of Western public opinion in a context of war such as the one experienced today in Ukraine, is expected to challenge impartiality. Balancing the executive and information power, even in times of war, information can be equidistant and independent. During the Ukraine war, information proved to be effective as an instrumental force for the mobilization of one of the parties in conflict: Ukraine. Whether it will be enough to bring peace? We could say that the fourth power could mark the history of humanity in previous conflicts and wars; this will be no exception.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

PE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Portuguese national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, under project UIDP/00713/2020.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acemoglu, D., and Robinson, J. (2006). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511510809

Albæk, E. (2011). The interaction between experts and journalists in news journalism. Journalism 12, 335–348. doi: 10.1177/1464884910392851

Araújo, R., and Lopes, F. (2014). Olhando o agenda-building nos textos de saúde: Um estudo dos canais e fontes de informação. Jornalismo Soc. 6, 749–753.

Berkowitz, D. (2009). “Reporters and their sources,” in The handbook of journalism studies, eds. K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch (New York: Routledge), 102–115.

Bezold, C. (1978). Anticipatory Democracy: People in the Politics of the Future. Penguin: Random House.

Blumler, J. (2001). The third age of political communication. J. Public Affairs 1, 201–209. doi: 10.1002/pa.66

Caillol, M. H. (2012). Political anticipation: observing and understanding global socioeconomic trends with a view to guide the decision-making processes. Int. J. General Syst. 41, 77–90. doi: 10.1080/03081079.2011.622094

Carlyle, T. (1866/2013). On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Cobb, R. W., and Elder, C. D. (1971). The politics of agenda-building: an alternative perspective for modern democratic theory. J. Polit. 33, 892–915. doi: 10.2307/2128415

Dubois, D. M. (1998). “Computing Anticipatory Systems with Incursion and Hyperincursion,” in Computing Anticipatory Systems: CASYS'97, AIP Proceedings, ed. D.M. Dubois (American Institute of Physics), 3–29. doi: 10.1063/1.56331

Dubois, D. M. (2002). “Theory of incursive synchronization of delayed systems and anticipatory computing of chaos, in Cybernetics and Systems, 1, ed. R. Trappl (Vienna: Austrian Society for Cybernetic Studies), 17–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4471-0123-9_5

Dubois, D. M., and Sabatier, P. (1998). “Morphogenesis by diffuse chaos in epidemiological systems,” in Computing Anticipatory Systems: CASYS'97, AIP Proceedings, ed. D.M. Dubois (American Institute of Physics), 295–308. doi: 10.1063/1.56307

Easton, D. (1957). An approach to the analysis of political systems. Quart. J. Int. Relat. 9, 383–400. doi: 10.2307/2008920

Eck, K., and Hultman, L. (2007). One-sided violence against civilians in war. J. Peace Res. 44, 233–246. doi: 10.1177/0022343307075124

Espírito Santo, P., and Lopes, F. (2019). Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, a popular president who has all the media coverage: content analysis of the press (2016-2018). Observ. J. 2019, 001–013. doi: 10.15847/obsOBS13420191474

Fisher, C. (2018). “News sources and journalist/source interaction,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication (Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.849

Fuchs, C. (2004). “The political system as a self-organizing information system,” in Trappl, R. Cybernetics and Systems, 1, ed. R. Trappl (Vienna: Austrian Society for Cybernetic Studies), 353–358.

Hegre, H. (2014). Democracy and armed conflict. J. Peace Res. 51, 159–172. doi: 10.1177/0022343313512852

Lopes, F., Araújo, R., Magalhães, O., and Santos, C. A. (2023). The visibility of specialised sources in journalism: the example of COVID-19. Comun. Soc. 43:e023011. doi: 10.17231/comsoc.43(2023).4270

Macaulay, T. B. (2004). Critical and Historical Essays, Part 1 (The Complete Writings of Lord Macaulay). Whitefish: Kessinger Publishing.

MacKenzie, M., Setala, M., and Kyllönen, S. (2023). Democracy and the Future. Future Regarding Governance in Democratic Systems. Edinburgh: Edinburg University Press. doi: 10.3366/edinburgh/9781399512749.001.0001

Maoz, Z., and Russett, B. (1992). Alliances, wealth, contiguity and political stability: is the lack of conflict between democracies a statistical artifact? Int. Interact. 17, 245–267. doi: 10.1080/03050629208434782

McCombs, M., and Shaw, D. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin. Q. 36, 176–187.

Mölder, H. (2021). “Culture of fear: the decline of Europe in Russian political imagination,” in A Continent of Conspiracies: Conspiracy Theories in and about Europe, eds. A. Krouwel, and A. Önner-fors (London: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781003048640-12

Mölder, H., and Sazonov, V. (2018). Information warfare is the hobbesian concept of modern times. It consists of principles, techniques, and tools of Russian information operations in Donbass. J. Slavic Military Stud. 31, 308–328. doi: 10.1080/13518046.2018.1487204

Mölder, H., and Sazonov, V. (2019). The impact of Russian anti-western conspiracy theories on the Status-related conflict in Ukraine—The case of flight MH17. Baltic J. Eur. Stud. 9, 96–115. doi: 10.1515/bjes-2019-0024

Montesquieu (1748). De l'Esprit des Lois. Paris : Gallimard, Folio Essais, 2003. doi: 10.1522/cla.moc.del7

OPORA Report (2022). Mедіаспоживання українців в умовах повномасштабної війни. Опитування ОПОPИ, Available at: https://www.oporaua.org/polit_ad/mediaspozhivannia-ukrayintsiv-v-umovakh-povnomasshtabnoyi-viini-opituvannia-opori-24068 (accessed March, 2023).

Prokop, M. (2023). Russia -Ukraine: Difficult Neighbourly Relations. The Russa-Ukraine war of 2022. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003341994-2

Rosen, R. (1985). Anticipatory Systems: Philosophical, Mathematical & Methodological Foundations. Oxord: Pergamon Press.

Snegovaya, M. (2015). Putin's Information Warfare in Ukraine: Soviet Origins of Russia's Hybrid Warfare. USA: Institute for the Study of War.

Voinea, C. F. (2023). “Political Participation and Anticipatory Democracy. An Anticipatory System Approach” in (paper presentation) ECPR General Conference. 4-8 September 2023. Charles University of Prague. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/373679347_Political_Participation_and_Anticipatory_Democracy_An_Anticipatory_System_Approach (accessed March, 2023).

Keywords: anticipatory approach, war, Ukraine, agenda building, content analysis, Portuguese press

Citation: Espírito Santo P (2024) Anticipatory approach to war and agenda building: a content analysis study of Portuguese press coverage of the Ukraine war (2014–2023). Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1341515. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1341515

Received: 20 November 2023; Accepted: 30 August 2024;

Published: 20 September 2024.

Edited by:

Natalia Petiy, Uzhhorod National University, UkraineReviewed by:

Vladimir Sazonov, University of Tartu, EstoniaMaryana Prokop, Jan Kochanowski University, Poland

Copyright © 2024 Espírito Santo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paula Espírito Santo, Z2Fib3JvbmUyMDA4QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Paula Espírito Santo

Paula Espírito Santo