94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 22 May 2024

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1339506

Rizal Khadafi1*

Rizal Khadafi1* Achmad Nurmandi2

Achmad Nurmandi2 Effiati Juliana Hasibuan3

Effiati Juliana Hasibuan3 Muhammad Said Harahap4

Muhammad Said Harahap4 Agung Saputra1

Agung Saputra1 Ananda Mahardika1

Ananda Mahardika1 Jehan Ridho Izharsyah1

Jehan Ridho Izharsyah1The matter of transparency regarding information and data emerges as a pivotal concern in the context of mitigating the COVID-19 epidemic in Indonesia. The regulation of public information transparency in Indonesia is stipulated in Law Number 14 of 2008, which ensures the disclosure of public information. The objective of this study is to conduct a comprehensive examination of the extent to which the Government of Indonesia adheres to the principles outlined in its legislation with regard to the implementation of transparency throughout the pandemic. The approach employed to assess the degree of adherence is normative-empirical analysis. The findings of this research analysis indicate a significant lack of transparency in the public dissemination of COVID-19 information and data in Indonesia. This lack of transparency is inconsistent with the provisions outlined in Law No. 14 of 2008, which governs the publication of public information in the country. The act of downplaying COVID-19 through the dissemination of information, along with the government's decision to withhold comprehensive data, and the prevailing skepticism toward scientific research might be characterized as efforts to impede citizens' access to precise knowledge.

Over the past 2 years, concerns about government and citizen communication during the COVID-19 outbreak have received a great deal of public attention. These concerns include a lack of efficiency, a lack of openness, and inconsistent information. The public's trust in the government has been eroded by these problems (Ciobanu and Roşca, 2021). Conclusions about the need of transparency in building public trust in the epidemic response can be drawn from South Korea's experience managing the MERS-CoV outbreak in 2015 (Kang and Lee, 2021). Pandemic-related hoaxes quickly spread on the internet and social media networks as a result of the South Korean government's incapacity to communicate with the populace at the time (Fung et al., 2015). This failure inspired the South Korean government to develop a new, improved system for information sharing and communication, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 epidemic. It is also evident in the current situation in the United States that the lack of transparency in communications from the national highest government has made it difficult for bureaucracy at all levels—federal, state, and local—to manage the COVID-19 pandemic crisis (Hatcher, 2020).

Currently, researchers in several nations around the world are concerned about the transparency of COVID-19 information and data. Researchers frequently address the themes of vaccine information transparency, protection of health workers and activists, infection rates, cure rates, mortality rates, and the way the government disseminates information. The researchers did not, however, completely rule out the possibility that the COVID-19 pandemic information transparency policies were also directly influenced by the virus's tendency to change over time, as well as by governmental structures, leadership paradigms, and socioeconomic and political circumstances in each nation (Fernandes and Badin, 2021). For instance, the COVID-19 royal order in Spain has resulted in substantial restrictions on journalists' access to information as well as constraints on social freedoms, educational opportunities, and access to clear public information (León, 2020; Cifuentes-Faura, 2021). While up until now, Spain has been a nation that supports the right to free speech.

In Ghana, failure to tackle corruption, poor and non-transparent pandemic governance severely affected public satisfaction and trust in the government, and this resulted in a lack of citizen participation in COVID-19 activities (Arkorful et al., 2021). The Israeli government's pandemic communication strategy, which has received harsh criticism from the general public, includes intimidation, inaccurate information, directives to the public that are in opposition to the health and risk communication method, and political manipulation of the COVID-19 pandemic issue (Gesser-Edelsburg and Hijazi, 2020). Even though the UK is recognized for upholding the transparency of public information, it was discovered that many health workers there were hushed for raising their worries regarding the lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) for COVID-19 (Braillon, 2021). In Indonesia, the results of a public opinion poll about government transparency in COVID-19 information releases are still at a low level, at 8%, and this leads in a minimum degree of trust in official information surrounding the pandemic (Pramiyanti et al., 2020).

No government in the world is generally entirely prepared to deal with the COVID-19 epidemic, thus the three traits of leaders in a crisis situation like this one, namely leaders who are present, show empathy, and exhibit transparent leadership, are crucial (Hayes and Cocchi, 2022). Public trust and transparency throughout the pandemic are also essential because public mistrust, worries about transparency, and evidence- and knowledge-based communication patterns in the decision-making process can affect people's perceptions of the government's response to the epidemic (Enria et al., 2021). Therefore, it is possible to define transparency of information on the COVID-19 epidemic as the government providing information that is clear and easily accessible while also taking the needs of the general public into consideration (Mimicopoulos et al., 2007).

Numerous scientific results have demonstrated the value of transparency in the pandemic era we are currently living in. There is a correlation between the total number of public reports and the total number of COVID-19 cases that are positive, according to Exploration Data Analysis (EDA) performed to examine the pattern of complaints regarding COVID-19 (Finola et al., 2020). This finding highlights the significance of good and transparent government communication because, in addition to fostering public trust that elected officials are aware of and interested in the views of the general public, it also increases citizen involvement in COVID-19 response (Anderson, 2010). As a result, the government can accomplish its objective of boosting public confidence in its decision-making procedure for handling the COVID-19 pandemic (Porumbescu, 2015).

To gain the trust of the public, public institutions must also provide information more freely. They must use this information to assess the effectiveness and safety of vaccines as well as information on how to treat COVID-19 disease (Rubin, 2020). Transparency in the modern period helps the public feel less uncertain and afraid while also helping to increase trust in health leadership and authorities (Choi and Powers, 2021). Therefore, with the help of data accessibility and openness, it is possible to promote public compliance with reasonable and responsible public health decision-making while also increasing public trust (O'Malley et al., 2009).

In the context of public information transparency in Indonesia during the pandemic, numerous studies imply that the government is not transparent when it comes to COVID-19 information and statistics. The government's capacity to disseminate information about the pandemic can be evaluated by examining the stories told by well-known individuals who mock COVID-19 (Asmorowati et al., 2021). Additionally, the government's public outreach during the pandemic has been exceedingly inconsistent and varied (Herman, 2021), and as a result, the general public rates the government's publication of COVID-19 data as being insufficiently transparent (Pramiyanti et al., 2020). In August 2021, the COVID-19 mortality data was withdrawn by the Indonesian government in order to evaluate the success of community activity restrictions (PPKM) (bbc.com, 2021), however, this decision was opposed by a number of parties, and ultimately the government's reliance on this revocation was only temporary (Adjie and Bahari, 2021; kominfo.go.id, 2021).

The Act No. 14 of 2008, which maintains the Openness of Public Information, is a legislative measure enacted in Indonesia in 2008. It was officially passed on 30 April 2008 and became effective 2 years subsequent to its passage. The set of legislation encompassing these 64 articles imposes a duty upon all public entities to grant access to any individual seeking public information, with the exception of specific types of information.

Undoubtedly, the endeavor of campaigning for this legislation entails a protracted and arduous undertaking. 42 coalitions of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) advocated for the passage of this bill, a significant development that occurred 8 years after the commencement of the year 2000. Originally, this legislation was referred to as the Freedom of Access to Public Information Act. The Public Information Opening Act has been a prominent legislative initiative of the People's Council of Representatives Initiative (DPR) since its establishment from 1999 to 2004. The Public Information Opening Act has been the subject of discussion since 1999, following a lengthy nine-year process. This deliberation was prompted by the growing demand for good governance, which emphasizes the importance of accountability, transparency, and public participation in all public policy processes. Consequently, the KIP Act was officially approved by the House on April 3, 2008, and subsequently passed on April 30, 2008.

The enactment of Act No. 14 of 2008, pertaining to the Opening of Public Information, is grounded upon several considerations. Firstly, it recognizes that information is a fundamental necessity for individual growth and social development, and plays a crucial role in bolstering national resilience. Secondly, it acknowledges the right to information as a fundamental human right, and emphasizes that the transparency of public information is a vital characteristic of a democratic state that upholds the sovereignty of its citizens, thereby facilitating the establishment of a well-functioning government. Thirdly, it underscores that the availability of open information serves as a means to enhance public oversight over the state and other public entities, as well as any matters that impact the public interest. Lastly, it recognizes that effective management of public information is a key endeavor in fostering the development of an information society.

The primary objective of Law No. 14 of 2008 on Open Public Information is to ensure the fulfillment of citizens' right to access information pertaining to public policy formulation, public policy programs, and public decision-making processes, as well as the rationale behind such decisions. Additionally, the law seeks to promote active public engagement in the public policy-making process, thereby fostering effective governance and responsible management of public institutions. Furthermore, it aims to establish a well-organized state apparatus characterized by transparency, effectiveness, efficiency, accountability and responsibility. Another objective is to enable the public to comprehend the underlying reasons behind public policies that directly impact the general population. Moreover, the law aims to contribute to the advancement of knowledge and the enlightenment of the nation. Lastly, it strives to enhance the management and provision of information services within public agencies, with a focus on delivering high -quality information services.

Information refers to descriptions, statements, ideas, and signs that possess values, meanings, and messages. It encompasses data, facts, and explanations that can be perceived through visual, auditory, and textual means. These forms of information are presented in various packages and formats, adapting to the advancements in electronic and non-electronic information and communication technology.

Public information refers to information that is produced, stored, managed, communicated, and/or received by a governmental entity in relation to the administration and operation of the State or any other public entity established and regulated under the provisions of this legislation. It also encompasses additional information that is deemed significant to the public's interest.

Public bodies refer to the executive, legislative, judicial, and other entities primarily responsible for upholding the functions and operations of the State. These derive their resources either partially or entirely from the State Revenue and Purchasing Budget and/or the Regional Revenues and Purchase Budget bodies. Alternatively, they may be non-governmental organizations that receive funding from the National Revenues and Purches Budget and/or the Regional Income and Purpose Budget, public contributions, and/or foreign sources.

The Information Commission is an autonomous entity responsible for the enforcement of the aforementioned Act and its accompanying rules. Its primary functions include the development of technical recommendations for ensuring the provision of standardized public information services, as well as the resolution of public information disputes through mediation or non-litigation support.

A public information dispute refers to a conflict that arises between public entities and individuals seeking access to and utilization of public information in accordance with legal provisions. Mediation refers to the resolution of a public information dispute between parties involved with the assistance of a mediator appointed by an information commission. Adjudication refers to the formal procedure employed for the resolution of public information disputes between the concerned parties, ultimately culminating in a decision rendered by the information commission. A public official refers to an individual who is designated and allocated to hold a specific job within a government entity. Information and Documentation Officers are individuals who have official positions and are entrusted with the tasks of managing, organizing and providing access to information inside public institutions.

In accordance with the provisions outlined in this legislation, the term “person” encompasses an individual, a collection of individuals, a legal entity, or a governmental entity. A public information user refers to an individual who utilizes public information in accordance with the provisions outlined in this legislation. The individual or organization applying for public information is a citizen of Indonesia or a legally recognized body, which files a request for public information in accordance with the provisions outlined in this legislation.

The major goal of this study is to offer a fresh perspective on how Indonesia, the third-largest democracy in the world, applies the principles of good governance when informing the public about the pandemic. This issue will be examined through an examination of media content and indicators included in Law Number 14 of 2008 Governing Information Disclosure in Indonesia. This Act expressly regulates four significant issues as its legal foundation. First, it is everyone's right to access information; second, it is the Public Agency's responsibility to fulfill information requests quickly, on schedule, cheaply and simply; third, exceptions are strictly regulated; and fourth, it is the Public Agency's responsibility to enhance the documentation system and information services (peraturan.bpk.go.id, 2008). As a result, this study will be the first to evaluate the Indonesian government's transparency during the pandemic using the metrics set forth in Law No. 14 Year 2008.

This study uses a descriptive qualitative methodology with media content analysis methodologies and empirical normative analysis based on the indicators in Law No. 14 of 2008. In this study, Google Dork was used as a data collection method. Dork is a simple hacking technique that uses Google Search to find security holes in the programming and setup of websites (techtarget.com, 2014). Using this method, the data are initially selected, and the search results are narrowed down to those that are pertinent to the topic of the study. For instance, the keyword “COVID-19+Indonesia+Data+Transparent” might be used to look for data without prejudice. Additionally, the code “inurl:”= “intext:” Indonesian COVID-19 data will be used to demonstrate the search. The phrases “not transparent,” “already transparent,” and similar expressions were avoided in the search to prevent the idea that the data collection was conducted unjustly.

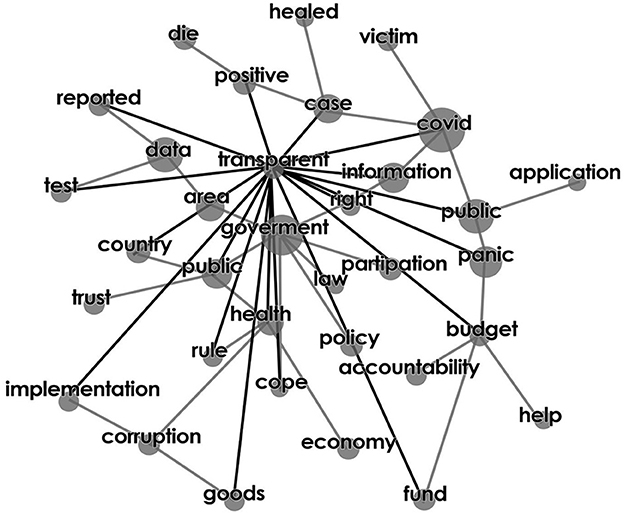

The information gathered from the research data sources (Table 1) was then selectively chosen. By taking into account the reliability of the internet media as well as looking at the credibility of the informants who are used as references by journalists, data sourced from online news stories will be divided according to the topics addressed. Data on infection rates, fatality rates, and cure rates were also gathered by keeping an eye on COVID-19 cumulative data in Indonesia, which may be read at https://covid19.go.id/. According to information obtained from all Indonesian regional governments, data on COVID-19 is periodically updated in Indonesia. In general, the mapping of public information transparency issues in Indonesia can be seen in Figure 1.

Additional information was gathered from internet comments, speeches made in public, and discussions with government officials about the transparency of COVID-19 data in Indonesia. Documents in the form of data will be gathered from books, journals, proceedings, and scientific records as well as official government documents. To support the findings of the research, data will also be used from reports, interviews, and investigations conducted by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and the media regarding the transparency of COVID-19 data in Indonesia. All of the data used was made available online. Data that has been chosen and processed as a whole has entered the public domain and is freely accessible. Therefore, there is no conflict of interest in the way the data were used for this research. In order to respond to research concerns about the transparency of COVID-19 information according on Law No. 14 of 2008, the data that has been acquired is evaluated using analytical techniques that are in accordance with research demands. The study was carried out between March 2021 and February 2022.

The world health organization (WHO) officially announced the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in China in September 2019 (WHO, 2020). The first virus case in Indonesia was discovered on March 2, 2020, but the government did not start the process of teaching and alerting the public about COVID-19 until then. After the first case of COVID-19 infection was discovered, the Indonesian government failed to release comprehensive information on the outbreak. Additionally, the case-tracking procedure is not made public, the statements made are inconsistent, and the rules put into place are closed (Al Farizi and Harmawan, 2020). Low public trust and low public support for the government's securitization efforts as a result of the government's tardy response to COVID-19 have also prevented the government from taking immediate action in response to the COVID-19 threat (Chairil, 2020).

Furthermore, it appears that discussions, deliberations, and development of public policy related to COVID-19 occurred without consideration for openness or other principles of good governance (Ayuningtyas et al., 2021). It was also discovered that the elite role played a very dominant part in the process of establishing policies, giving little heed to the usage of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in determining public preferences (Ramdani et al., 2021). The integrity and transparency of COVID-19 statistics are of particular concern to epidemiologists, who contend that a lack of data will make it difficult for the government to combat the COVID-19 pandemic (cnnindonesia.com, 2020).

The information in Figure 2 demonstrates a link with the conclusions of earlier investigations. The government sub-concept of transparency draws a distinct boundary with other ideas. The relationship between the transparent idea and cases demonstrates that data openness with regard to positive COVID-19 cases, the number of patients who have recovered, and the number of victims who died is given particular consideration. The line that links the idea of transparency with data also demonstrates the need for greater transparency regarding the quantity of tests and tracking the government conducts.

Figure 2. Media content analysis on COVID-19 data transparency in Indonesia. Source: Leximencer Media Content Analysis 2021 (https://www.leximancer.com/).

Indirect confirmation of public attention to President Joko Widodo's speech that not all information linked to COVID-19 can be transmitted to the public since it is thought that it may cause panic is provided by the line connecting the transparent idea with the concepts of society and panic (Kompas.com, 2020). During COVID-19, there was emphasis paid to the transparency of how the budget was used, how things were purchased, and how the government assisted the community, as seen by the line connecting the concepts of funds, budget, and goods. However, the lines that connect the concepts of information, public, and rights show that there is a need from the public for the right to transparent information on the COVID-19 epidemic.

The government body in charge of communicating and spreading information regarding COVID-19 at the beginning of the pandemic was the Task Force for the Acceleration of Handling COVID-19 (COVID-19 Task Force), which was established in accordance with Presidential Decree No. 7 Year 2020 (peraturan.bpk.go.id, 2020a). This task force is part of the National Disaster Management Agency of the Republic of Indonesia (BNPB RI), and it includes local government, the Indonesian National Police (POLRI), the Indonesian National Army (TNI), and the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia (KEMENKES RI). Based on Presidential Decree No. 82 of 2020, this entity was subsequently abolished on July 20, 2020 (peraturan.bpk.go.id, 2020b). The authority for this agency was later transferred to the COVID-19 Handling Task Force at the COVID-19 Handling Committee and National Economic Recovery (KPEN). But up to this point, the objectives and responsibilities of this task group have largely stayed the same.

The COVID-19 Task Force has five spokespeople in its capacity as an official government-appointed organization charged with informing the general public. The first spokesperson is the leader of the expert team handling COVID-19; the second is the task force's official spokesperson; the third is a representative of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia (KEMENKES RI); the fourth is a representative of the Food and Drug Supervisory Agency of the Republic of Indonesia (BPOM RI); and the fifth is a representative of the State Pharmaceutical Company (BIOFARMA). Five government-appointed spokespersons have been given the responsibility of disseminating information regarding the overall control of COVID-19, scientific aspects relating to vaccines, vaccine safety, quality, and efficacy, government vaccination programs, logistical availability and distribution of vaccines, aspects of vaccine licensing, and healthy living recommendations and preparation to the new normal (covid19.go.id, 2020b).

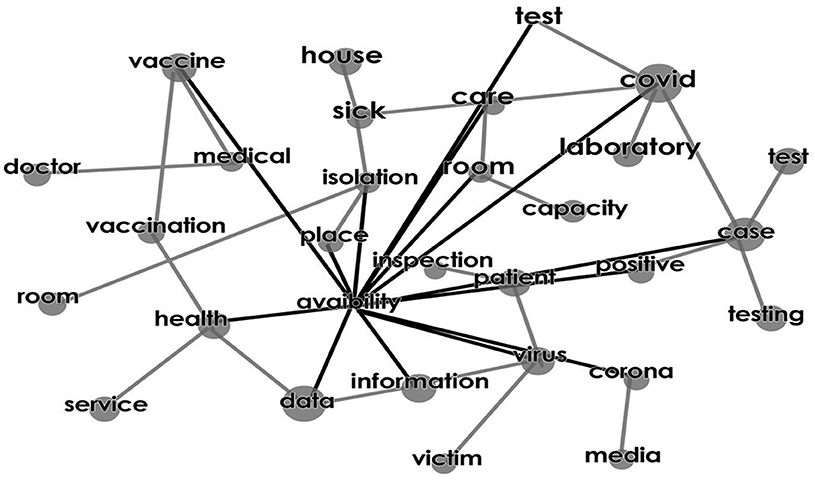

Regarding the data in Figure 3, the availability idea, which is a sub-concept of data, does specifically pertain to vaccinations. This demonstrates a reasonably high public desire for knowledge on vaccines to be accessible. The public needs to know whether hospital isolation rooms are available for patients who are positive for COVID-19 because the word availability also directly refers to locations, isolation, and rooms. Additionally, the availability of locations and information for doing laboratory tests for COVID-19 is the factor that is highlighted the most. The last point being emphasized is the accessibility of data and information pertaining to COVID-19 as a whole.

Figure 3. Media content analysis on the availability of COVID-19 data in Indonesia. Source: Leximencer Media Content Analysis 2021 (https://www.leximancer.com/).

The selection of the five spokespeople in the manner previously mentioned merits praise since it allows the public to witness individuals designated to disseminate information about COVID-19 who are competent and knowledgeable in the disciplines of health, vaccinations, and medicine. This is consistent with the analysis's findings, which indicated that there was a great desire for comprehensive information about the immunization program. The five spokespeople's appointment did not, however, appear to address the core issues with positive numbers, test and tracing numbers, cure rates, and death rates. Government appointments and assignments show that the government is more concerned with the immunization program and getting ready for the new normal.

The Indonesian government launched the www.covid19.go.id website, which contains information linked to the development of information on COVID-19 in Indonesia, in order to meet the demands of internet-based information disclosure. However, as there isn't much high-quality information on the site, its existence is likewise of less importance. It is feared that the inability to create effective coping mechanisms for the current circumstances will result in long-term losses due to the lack of high-quality data available to the public and academics in Indonesia, particularly for epidemiologists to analyze the development of the current epidemic (Januraga and Harjana, 2020).

The lack of COVID-19 data can be determined by looking at the absence of the number of tests and tracing on the official government website Covid91.go.id. The figures only contain the rates of infection, death, and cure (Covid19.go.id, 2021). Data from PCR laboratory tests at the district, city, and provincial levels are similarly not publicly available because they are not released and publicized (Kompas.com, 2021). According to an independent group that keeps track of the COVID-19 handling issue at https://laporcovid19.org/, only two of Indonesia's 34 provinces—the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (DKI Jakarta) and West Java—convey information in real time and are simple to access or download (tempo.co, 2021). The Minister of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia also acknowledged that the availability of incomplete, incomplete data, and the current system is also a problem that hinders Indonesia's handling of COVID-19 (medcom.id, 2020).

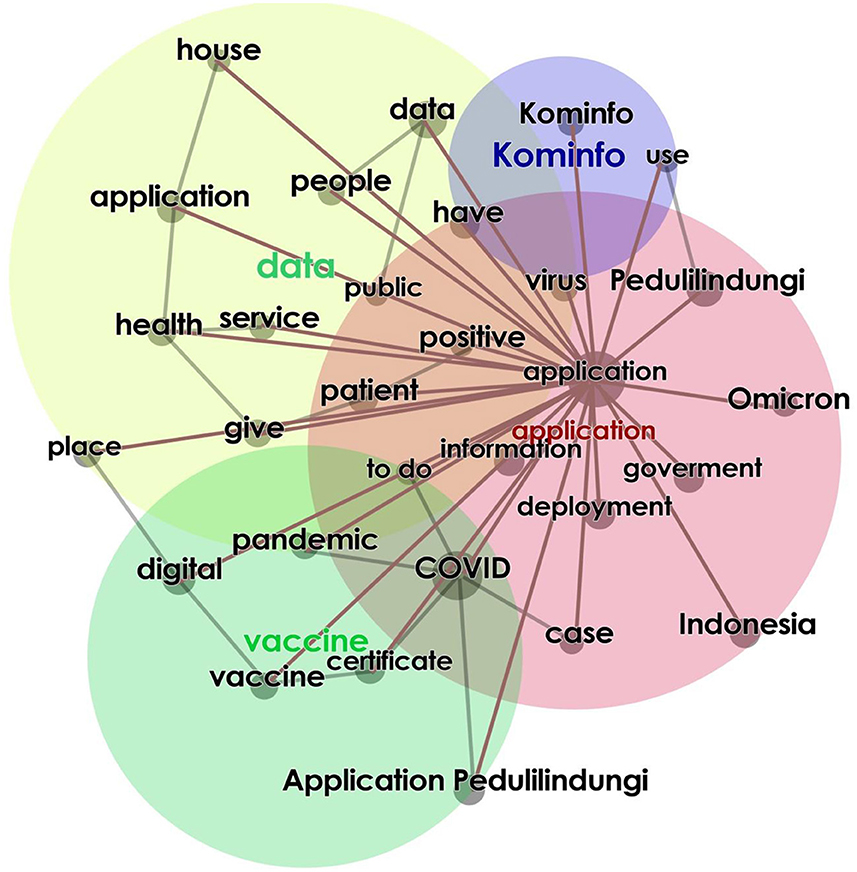

The National Disaster Management Agency (BNPB RI), the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia (KEMENKES RI), the Office of the Presidential Chief of Staff (KSP), and the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology of the Republic of Indonesia (KOMINFO RI) have worked together to present the application in order to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. The cooperation has so far produced five applications; PeduliLindungi, Rumah Aman, Bersatu Lawan COVID-19 (BLC), M-Health, and telemedicine (beritasatu.com, 2020). Both the Google Play Store and the Apple App Store offer free and open access to this application.

These five programs, in that order, perform the tasks of tracing, reporting, monitoring, prevention, and health consultation. These programs can be used to learn more about COVID-19 in general and to get vaccination-related data. Bersatu Lawan COVID-19 application, for instance, offers two features that are separately aimed at policymakers and the general public. This system offers data from 514 districts/cities and 34 provinces, including information on the population, health, and logistics for use by policymakers. These data can be utilized to develop precise, quantifiable, and efficient policies. The data can be accessible by the general public at covid19.go.id, the official website of the COVID-19 Task Force for the Acceleration of Handling, which was created for this purpose (kominfo.go.id, 2020).

The application concept builds a line to practically all other concepts using the data in Figure 4. The application theme and the vaccination theme both feature the PeduliLindungi application idea. This conclusion is consistent with the fact that it is necessary to register for vaccinations and receive vaccination certificates in order to comply with governmental laws. Additionally, the PeduliLindungi application has attracted a lot of attention from the public due to its features, which include vaccine information, vaccination schedules and locations, and basic COVID-19 information. Even though the government has released a number of applications to speed up the processing of the COVID-19 epidemic, such as the PeduliLindungi application, the public has not given these applications much attention.

Figure 4. Media content analysis of COVID-19 applications in Indonesia. Source: Leximencer Media Content Analysis 2021 (https://www.leximancer.com/).

The Indonesian government has made an effort to develop the public information service system, as evidenced by the indications of the duty of public institutions to improve the documentation system and information services. The government's release of the Bersatu Lawan Covid (BLC) system is one of its tangible actions. BLC is an integrated information system to increase the acceleration of data recording in tackling COVID-19 throughout Indonesia (covid19.go.id, 2020a). BLC also helps local governments speed up the recording of data at the level of public health facilities, hospitals, laboratories, and health services. The fact that there are several programs in place to make it easier for the general public to access information is evidence that the government is open to the development of web-based information technology. The government of Indonesia has been urged to improve the system and provide public access to COVID-19 pandemic data in order to strengthen the nation's response to the disease (Januraga and Harjana, 2020).

According to the findings of this study's investigation, the Indonesian government was not transparent with COVID-19 data. Although the requirement of public institutions to improve the documentation system through a variety of technology and information-based government initiatives has increased, the obligation of public institutions to provide individuals with the data they need has not been fully met. The findings of this investigation also revealed that the COVID-19 data transparency policy did not adhere to the requirements of Law No. 14 of 2008, which governs the disclosure of information in Indonesia.

Public transparency is one method for maintaining public trust throughout the pandemic; as a result, establishing fair and transparent norms is a prerequisite for both trust and effectiveness (Braillon, 2021). The results of this study also demonstrate a correlation with earlier findings that public perceptions of transparency in government releases of COVID-19 information are still at a low level, particularly in the setting of Indonesia (Pramiyanti et al., 2020). Additionally, the government does not publicly conduct mass testing or case tracking procedures, nor does it disclose detailed information on the outbreak in official statements (Al Farizi and Harmawan, 2020). The lack of prompt action by the government in response to the COVID-19 danger and poor public trust make this situation worse (Chairil, 2020; Olivia et al., 2020).

The formulation and implementation of public policies to address COVID-19 were deemed to have a conflict of interest since these policies were negotiated, deliberated, and developed without regard for openness or the principles of good governance (Ayuningtyas et al., 2021). In addition, in the policy-making process, a dominant elite role was found, with little attention paid to public consultation and the use of AI as a preference (Ramdani et al., 2021). The government's actions throughout the epidemic appear to have been strongly pro-market and aimed at upholding a strong power's hegemony (Masduki, 2020).

The weakness of this research lies in the source of research data that is not verified directly to the authorized officials and institutions. The analytical content media used as a method also has limitations in exploring the government's motives regarding the transparency of COVID-19 data in Indonesia. Sources of research data acquired from online media are frequently biased because they must correspond to the interests of the editor and the market need of readers, even though the author has carefully picked them to entirely adhere to the requirements of producing scientific articles. In addition, it seems that the Indonesian government's insufficient data and poor data quality cause research questions to draw conclusions before they are fully established. However, in light of the current COVID-19 pandemic, the study's conclusions have led to fresh discussions regarding how to implement Law No. 14 of 2008 on Public Transparency. The shortcomings of the research are partially mitigated by the indicators in Law No. 14 of 2008, which are used as a measuring tool to evaluate the transparency of COVID-19 data in Indonesia. This will enable more investigation into how the state's own laws don't always seem to be strictly adhered to by the government.

To maintain public credibility and trust throughout the pandemic crisis, the government is urged to use communication strategies that demonstrate empathy and concern, competence and expertise, honesty and transparency, as well as dedication and commitment (Reynolds and Quinn, 2008). It is imperative to be transparent during a pandemic crisis like COVID-19 because knowing the number of infections, testing, and fatalities implies managing human health and life. The management of the pandemic must therefore be transparent, straightforward, and coordinated between the federal government and local governments in order to prevent public confusion and to promote and enforce compliance (Rahimi and Abadi, 2020; Ghazali et al., 2021). The Indonesian government must now synchronize and enforce the principle of transparency in addition to correcting the data system, since this has been shown to be crucial to boosting public confidence in the government's ability to combat the COVID-19 outbreak (Endraria, 2020).

The study's findings indicate that the Indonesian government has not fully upheld citizens' rights to comprehensive, high-quality, and transparent information about COVID-19 data in Indonesia. A topic that receives a lot of attention is the lack of information about the quantity of tests and tracings on the official government website and in official speeches. Second, Indonesian public institutions have not effectively complied with their duty to submit information relating to COVID-19. Public attention has been drawn to the issue of incomplete data regarding the availability of isolation rooms for treating COVID-19 patients in healthcare facilities. The public also believes that the findings of laboratory tests for COVID-19 tests are not entirely available, as does the availability of data.

Third, the notion that public institutions must improve their information services and documentation systems has gained broad popular support. The advent of several technology-based tools that assist Indonesia in managing the COVID-19 outbreak has elicited this fervent response. The general public will likely find it easier to report, monitor, prevent, and get information on the virus and the COVID-19 immunization program as a result of the availability of these many programs.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

RK: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AN: Supervision, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. EH: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. MH: Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Software, Writing—original draft. AS: Formal analysis, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing. AM: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Methodology, Writing— review & editing. JI: Resources, Conceptualization, Supervision, Visualization, Writing—review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adjie, H. K., and Bahari, D. M. (2021). Examining Indonesian government strategies in the aviation sector post Covid-19 pandemic. J. Contemp. Govern. Public Policy 2, 79–91. doi: 10.46507/jcgpp.v2i2.45

Al Farizi, S., and Harmawan, B. N. (2020). Data transparency and information sharing: coronavirus prevention problems in Indonesia. Indones. J. Health Admin. 8, 35–50. doi: 10.20473/jaki.v8i2.2020.35-50

Anderson, M. R. (2010). Community psychology, political efficacy, and trust. Polit. Psychol. 31, 59–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2009.00734.x

Arkorful, V. E., Abdul-Rahaman, N., Ibrahim, H. S., and Arkorful, V. A. (2021). Fostering trust, transparency, satisfaction and participation amidst COVID-19 corruption: does the civil society matter? – Evidence from Ghana. Public Organiz. Rev. 22, 1191–1215. doi: 10.1007/s11115-021-00590-w

Asmorowati, S., Schubert, V., and Ningrum, A. P. (2021). Policy capacity, local autonomy, and human agency: tensions in the intergovernmental coordination in Indonesia's social welfare response amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Asian Public Policy 15:2. doi: 10.1080/17516234.2020.1869142

Ayuningtyas, D., Haq, H. U., Utami, R. R. M., and Susilia, S. (2021). Requestioning the Indonesia government's public policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic: black box analysis for the period of January–July 2020. Front. Public Health 9:612994. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.612994

bbc.com (2021). Angka kematian Covid di Indonesia dihapus dari indikator evaluasi, pemerintah disebut “menipu diri sendiri” - BBC News Indonesia. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/indonesia/indonesia-58171050 (accessed August 19, 2021).

beritasatu.com (2020). Aneka Aplikasi Bantu Penanganan Covid-19. Available online at: https://www.beritasatu.com/news/713733/aneka-aplikasi-bantu-penanganan-covid19 (accessed April 15, 2021).

Braillon, A. (2021). Lack of transparency during the COVID-19 pandemic: nurturing a future and more devastating crisis. Infect. Cont. Hosp. Epidemiol. 42:1. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.271

Chairil, T. (2020). Indonesian government's COVID-19 measures, january-may 2020: late response and public health securitization. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial Dan Ilmu Politik 24, 128–152. doi: 10.22146/jsp.55863

Choi, S., and Powers, T. L. (2021). COVID-19: Lessons from South Korean pandemic communications strategy. Int. J. Healthc. Manage. 14, 271–279. doi: 10.1080/20479700.2020.1862997

Cifuentes-Faura, J. (2021). Transparency in Spanish government in times of Covid-19. Public Integ. 24, 644–653. doi: 10.1080/10999922.2021.1958562

Ciobanu, R., and Roşca, M. (2021). The impact of Covid-19 on the relationship between governance and society: evidence from an online survey. J. Commun. Posit. Pract. 21, 65–78. doi: 10.35782/JCPP.2021.3.06

covid19.go.id (2020a). Gugus Tugas Nasional Lakukan Peluncuran Awal Sistem Informasi Bersatu Lawan COVID - Berita Terkini. Available online at: Covid19.go.id (accessed December 21, 2020).

covid19.go.id (2020b). Inilah 5 Juru Bicara Vaksinasi COVID-19 - Masyarakat Umum. Available online at: Covid19.go.id (accessed December 21, 2020).

Covid19.go.id (2021). Peta Sebaran COVID-19. Available online at: https://covid19.go.id/peta-sebaran-covid19 (accessed April 5, 2021).

Endraria (2020). Influence of information quality on the development of COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesian. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 29, 1493–1500. Available online at: https://jurnal.umt.ac.id/index.php/JAST/article/download/5640/3094

Enria, L., Waterlow, N., Rogers, N. T., Brindle, H., Lal, S., Eggo, R. M., et al. (2021). Trust and transparency in times of crisis: Results from an online survey during the first wave (April 2020) of the COV-19 epidemic in the UK. PLoS ONE 16:e239247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239247

Fernandes, M. F. P., and Badin, M. R. S. (2021). Transparency and regulatory cooperation on international trade for medical products to tackle COVID-19: an assessment of the WTO institutional role and the Brazilian notifications under the TBT and SPS Agreements. Brazil. J. Int. Law 18, 35–54. doi: 10.5102/RDI.V18I2.7250

Finola, C. F., Nugraha, Y., Suprijono, S. A., Larrantuka, A., Kanggrawan, J. I., and Suherman, A. L. (2020). “Analysis of public complaint reports during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of Jakarta's citizen relations management,” in 7th International Conference on ICT for Smart Society, ICISS 2020. doi: 10.1109/ICISS50791.2020.9307562

Fung, I. C.-H., Tse, Z. T., Chan, B. S., and Fu, K.-W. (2015). Middle East respiratory syndrome in the Republic of Korea: transparency and communication are key. West. Pacific Surveill. Response J. 6, 1–2. doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.2.011

Gesser-Edelsburg, A., and Hijazi, R. (2020). When politics meets pandemic: How prime minister netanyahu and a small team communicated health and risk information to the Israeli public during the early stages of COVID-19. Risk Manage. Healthc. Policy 13, 2985–3002. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S280952

Ghazali, R., Djafar, T. M., and Daud, S. (2021). Policies and social advantages toward a new normal: a case study of handling the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Int. J. Organiz. Divers. 21, 71–87. doi: 10.18848/2328-6261/CGP/v21i01/71-87

Hatcher, W. (2020). A failure of political communication not a failure of bureaucracy: the danger of presidential misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Rev. Public Administrat. 50, 614–620. doi: 10.1177/0275074020941734

Hayes, M. M., and Cocchi, M. N. (2022). Critical care leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Critical Care 67, 186–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2021.09.015

Herman, A. (2021). Indonesian government's public communication management during a pandemic. Probl. Perspect. Manage. 19, 244–256. doi: 10.21511/ppm.19(1).2021.21

Januraga, P. P., and Harjana, N. P. A. (2020). Improving public access to COVID-19 pandemic data in Indonesia for better public health response. Front. Public Health 8:563150. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.563150

Kang, C., and Lee, I. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic, transparency, and “Polidemic” in the Republic of Korea. Asian Bioeth. Rev. 13, 213–224. doi: 10.1007/S41649-021-00164-4/METRICS

kominfo.go.id (2020). Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika||Aneka Aplikasi Bantu Penanganan Covid-19. Available online at: https://www.kominfo.go.id/content/detail/31754/aneka-aplikasi-bantu-penanganan-covid-19/0/sorotan_media (accessed June 26, 2021).

kominfo.go.id (2021). Kementerian Komunikasi dan Informatika||Menkominfo: Indikator Angka Kematian Covid-19 Tak Dihapus Tapi Dirapikan. Available online at: https://www.kominfo.go.id/content/detail/36319/menkominfoindikatorangkakematiancovid19takdihapustapidirapikan/0/berita_satker (accessed June 26, 2021).

Kompas.com (2020). Jokowi Akui Pemerintah Rahasiakan Sejumlah Informasi soal Corona. Available online at: https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2020/03/13/16163481/jokowi-akui-pemerintah-rahasiakan-sejumlah-informasi-soal-corona (accessed August 21, 2021).

Kompas.com (2021). Transparansi Data Penanganan Covid-19 di Indonesia Masih Jadi Persoalan Halaman all Kompas.com. Available online at: https://nasional.kompas.com/read/2021/04/08/14562041/transparansi-data-penanganan-covid-19-di-indonesia-masih-jadi-persoalan?page=all (accessed August 21, 2021).

León, P. G. (2020). The path of transparency in Spain during COVID-19. Revista Espanola de la Transparencia 11, 21–30. doi: 10.51915/ret.119

Masduki, M. (2020). Blunders of government communication: the political economy of COVID-19 communication policy in indonesia. Jurnal Ilmu Sosial Dan Ilmu Politik 24, 97–111. doi: 10.22146/jsp.57389

medcom.id (2020). Atasi Covid-19, Ketersediaan Data Jadi Kendala Jalankan Kebijakan – Medcom.id. Available online at: https://www.medcom.id/ekonomi/makro/GNlqJayb-atasi-covid-19-ketersediaan-data-jadi-kendala-jalankan-kebijakan (accessed September 12, 2021).

Mimicopoulos, M., Kyj, L., and Sormani, N. (2007). Public Governance Indicators: A Literature Review, United Nations, 1–55. Available online at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/745453?v=pdf (accesed February 9, 2021).

Olivia, S., Gibson, J., and Nasrudin, R. (2020). Indonesia in the time of Covid-19. Bull. World Health Organ. 56, 143–174. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2020.1798581

O'Malley, P., Rainford, J., and Thompson, A. (2009). Transparency during public health emergencies: from rhetoric to reality. Bull. World Health Organ. 87, 614–618. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.056689

peraturan.bpk.go.id (2008). UU No. 14 Tahun 2008 tentang Keterbukaan Informasi Publik [JDIH BPK RI]. Available online at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/39047/uu-no-14-tahun-2008 (accessed March 15, 2021).

peraturan.bpk.go.id (2020a). KEPPRES No. 7 Tahun 2020 tentang Gugus Tugas Percepatan Penanganan Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [JDIH BPK RI]. Available online at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/134544/keppres-no-7-tahun-2020 (accessed March 15, 2021).

peraturan.bpk.go.id (2020b). PERPRES No. 82 Tahun 2020 tentang Komite Penanganan Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) dan Pemulihan Ekonomi Nasional [JDIH BPK RI]. Available online at: https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Details/141403/perpres-no-82-tahun-2020 (accessed March 15, 2021).

Porumbescu, G. A. (2015). Using transparency to enhance responsiveness and trust in local government: can it work? State Local Gov. Rev. 47, 205–213. doi: 10.1177/0160323X15599427

Pramiyanti, A., Dwi, I., Reni, M., Yasinta, N., and Firdaus, D. (2020). Public perception on transparency and trust in government information released during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Public Opini. Res. 8, 351–376. doi: 10.15206/ajpor.2020.8.3.351

Rahimi, F., and Abadi, A. T. B. (2020). Transparency and information sharing could help abate the COVID-19 pandemic. Infection Cont. Hosp. Epidemiol. 41:1. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.174

Ramdani, R., Agustiyara, P., and Purnomo, E. P. (2021). “Big data analysis of COVID-19 mitigation policy in Indonesia: democratic, elitist, and artificial intelligence,” in 10th International Conference on Public Organization, ICONPO 2020, 717. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/717/1/012023

Reynolds, B., and Quinn, S. C. (2008). Effective communication during an influenza pandemic: the value of using a crisis and emergency risk communication framework. Health Promot. Pract. 9, 13S–17S. doi: 10.1177/1524839908325267

Rubin, R. (2020). More transparency needed for COVID-19 emergency authorizations. JAMA. 324:2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24201

techtarget.com (2014). What is Google dork? - Definition from WhatIs.com. Available online at: https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/Google-dork-query (accessed May 23, 2021).

tempo.co (2021). Lapor Covid-19 Sebut Situs Data Corona Jakarta dan Jawa Barat Terbaik - Nasional Tempo.co. Available online at: https://nasional.tempo.co/read/1534348/lapor-covid-19-sebut-situs-data-corona-jakarta-dan-jawa-barat-terbaik (accessed August 16, 2021).

WHO (2020). WHO Timeline - COVID-19. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline—covid-19 (accessed June 4, 2021).

Keywords: COVID-19, policy, transparency, information, data, Indonesia

Citation: Khadafi R, Nurmandi A, Hasibuan EJ, Harahap MS, Saputra A, Mahardika A and Izharsyah JR (2024) Assessing the Indonesian government's compliance with the public information disclosure law in the context of COVID-19 data transparency. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1339506. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1339506

Received: 16 November 2023; Accepted: 22 April 2024;

Published: 22 May 2024.

Edited by:

Muhlis Madani, Muhammadiyah University of Makassar, IndonesiaReviewed by:

Francesco Mureddu, The Lisbon Council for Economic Competitiveness and Social Renewal, BelgiumCopyright © 2024 Khadafi, Nurmandi, Hasibuan, Harahap, Saputra, Mahardika and Izharsyah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rizal Khadafi, cml6YWxraGFkYWZpNzcyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.