- 1Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences, Bayero University Kano, Kano, Nigeria

- 2Department of Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Sokoto, Sokoto, Nigeria

The article examined the manifestations of political trust deficits associated with people's response to policy choices of Nigeria's government during the COVID-19 pandemic. Like many other states, the African states and particularly the Nigerian government adopted WHO-recommended containment measures to limit the spread of the virus and the associated catastrophe. These measures included lockdowns, shutdowns, social distancing, and personal hygiene among other preventive procedures. Even though the pandemic was relatively less endemic in Africa, as per official statistics, African states swiftly implemented the WHO containment measures, which impacted negatively on the livelihood of the average household, who depends on daily incomes for survival. The worsening living condition caused by the containment measures expectedly deepened resentment against governments in Africa with already poor records of public service delivery, accountability, transparency, and human rights. Nigeria was one of the African countries that experienced citizens' backlash and violent outrage against government policy choices during the COVID-19. Under the guise fighting police brutality, youths staged mass anti-government protests that transformed into large scale violence, particularly in the southern parts of the country otherwise known as the “EndSARS Protests.” The protests were conceived against police brutality in the enforcement of COVID-19 measures. This article examined the outbreak of EndSARS protests as a transformation of the deepening of political trust deficits in age of COVID-19. It adopted qualitative approach using documentary evidence such as newspaper reports and official documents as instruments of data collection. The Institutional Performance Theory guided the article. The theory assumes that the actual performance of government determines citizens' level of trust and confidence in public institutions. The article found that perennial government inefficiency, limited accountability and transparency as well as poor human rights records of the government and its agencies, particularly the police exacerbated an already existing political trust deficits amongst the people in Nigeria. This was manifested in the outburst of a large-scale violent outrage by the youths as protest to the government containment measures and widespread dysfunctional governmental institutions and particularly police brutality. The article concluded that building trust is particularly important for governments, as this can be achieved through output sense, the provision of public goods, or social support.

Introduction

Political trust in Nigeria has been a contentious issue for many years. The Nigerian government has often been criticized for not being transparent and accountable to its citizens. This has led to a lack of confidence in the government and its ability to deliver on its promises. However, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic brought about a shift in perception, as the government took decisive measures to address the crisis. The Nigerian government implemented various measures to curb the spread of the virus, such as the closure of schools, borders, and other public places, as well as the imposition of lockdowns in some states. These measures were received positively by the public, at the onset, but outraged by the flagrant inefficiency in the distribution of relief materials and the mismanagement of funds allocated for the COVID-19 response. This therefore, exacerbated the already existing political trust deficits in the country.

It should be noted that Corona Virus exploded and raged around the world for more than a year, which claimed millions of lives. While Europe, North America, Asia and other parts of the world responded well and vaccinated themselves out of the crisis, one region of the world seems to have gotten off relatively lightly: Sub-Saharan Africa. This is as per official statistics, which suggest a looming disaster on the continent, largely on account of poor records. However, an examination of the official COVID-19 case numbers and deaths in the region shows that the region weathered the storm relatively well (Rieger and Wang, 2022). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), sub-Saharan Africa accounts for only about 2 percent of all global cases (WHO, 2023).

The severity, immediacy and complexity of the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed weaknesses in the kind of institutional capacities that are typically theorized as essential in crisis situations. The basis for the functioning of institutional capacities, especially in a crisis whose solution depends on the behavior of individuals, is public trust and political legitimacy. By taking this action, one could have predicted that Nigeria would falter in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic as, in the year after the outbreak, socio-political tensions spilled over into an anti-government mass protest, which was seen in the form of EndSARS.

Indeed, the Nigerian government has been swift to institute intrusive measures to mitigate transmission of COVID-19 and the measures though adopted without adequate arrangements for the expected and unexpected consequences. For example, the government instituted the type of population-wide lockdown common in countries across the Americas, Europe and Asia and other parts of Africa (Jennings et al., 2020). Barely 6 months after the official community-wide lockdowns precisely in October 2020, Nigeria experienced ENDSARS mass protests, periodic street violence, large-scale arrests of students and anti-government demonstrators, and “flash mob” style confrontations between protesters and police in various districts, shopping malls and commercial centers. Trust in government was thus eroded by widespread perceptions of government inaction in dealing with the demands of protesters, with the government slow (some claimed recalcitrant) in withdrawing legislation that would allow Nigerian citizens to be extradited, though the case remain inconclusive.

Trust in government, which is the extent to which citizens depend on the government to fulfill its commitments, is primarily influenced by government performance, as noted by Jack and Laura in 2018. This performance assessment includes citizens' observations of the actions of political leaders, their effectiveness in crime control, economic management, avoidance of scandals, and other subjective performance criteria. Based on these evaluations, individuals determine the level of trust they place in the government, as emphasized by Keele (2007).

Trust can also be achieved through output sense, the provision of public goods, or social support. Building trust is particularly important for governments, as this will enable them to govern without coercion, thereby reducing transaction costs and increasing their efficiency and effectiveness.

Arguably the most difficult test of governments capacity in the new millennium, COVID-19 caught the world unprepared. To contain the spread of the virus, governments have had to respond quickly and comprehensively: strict lockdowns, restriction on movement, masks and social distancing measures that draw not only on public funds but also on the support and cooperation of civil society. Citizens' compliance and cooperation are based on trust in state institutions. In this respect, the pandemic was also a stress test for trust in the government.

Political trust is therefore probably based on the performance assessment of political institutions and depends on the extent to which citizens believe that the governance has led or can lead to desired results (North, 1990). Most empirical studies focus on macroeconomic performance (Van der Meer and Hakhverdian, 2017), while paying less attention to other areas such as other emergency policy decisions (Kumlin, 2017).

The global COVID-19 pandemic offers a unique opportunity to monitor government responses and political confidence during the crisis. In fact, some authors argue that poor performance and unresponsiveness of political institutions during the crisis are even more important causes of falling confidence levels than the economic crisis itself (Rieger and Wang, 2022).

Governments are the trustees whose performance would be evaluated by the citizens (Hartwig and Hoffmann, 2021). Assuming a rational Bayesian update process as a benchmark, people would revise their previous beliefs by incorporating new information. The prior belief can be formed based on past performance, which is determined by government effectiveness in our analysis. It is a measure of government quality and competence based on track record. We expect that more effective governments will gain more political trust from their citizens. COVID-19 is a new, invisible and unknown threat.

Prior to the development of a vaccine, individuals in Africa adhere to stringent preventive health practices and curtail their social interactions to mitigate the virus's transmission. Consequently, governments in the region have instituted a range of restrictive measures. Two potential mechanisms influence the execution of these measures. The first mechanism involves government authorities exercising stringent control over citizens' behavior, and a strong sense of trust in the government motivates individuals to willingly comply with governmental directives. This obedience is analogous to enforcing a quasi-house arrest, necessitating the government to possess substantial social control capabilities.

Reactions of citizens across the world has been recorded in a number of literature. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Global Protest Tracker 2020 traces hundreds (100) of anti-government protests that erupted around the world, from election protests in Honduras to Petro Caribe in Haiti, term limits in Guinea, pension reform strike in Greece, police brutality in Germany, Great March return protests in Gaza (Carnegie, 2022).

Three Years is Enough protests in Gambia, Black Lives Matter protests in the United States, corruption protests in Egypt, autonomy protests in Hong Kong, slave protests in Hungary, penal code protests in Indonesia, fuel increase protests in Iran, protests against the Corona virus in Israel, economic protest in Liberia, ethnic violence protest in Mali, religion law protest in Montenegro, racial equality protest in New Zealand, police brutality protest in Portugal, coronavirus restriction protest in Russia and protest against police brutality in United States of America (Carnegie, 2022). All of these protests took place between 2017 and 2020.

These protests across the world were largely influenced by perceived and observed inefficiencies, weak institutional capacities and corruption associated with governments of various countries. Thus the COVID-19 policy measures only exposed the fragile trust base of the citizens and instigated a variety of radical backlashes in form of antigovernment protests and civil disobedience. This was the case with the Nigeria's EndSARS Protests. Hooghe's thesis on mass protests in both developing and developed countries suggests that these protests are frequently driven by common factors, transcending the economic and political differences between nations. Key motivators include perceived governmental failure, a shared desire for political change, solidarity with global social movements, increased connectivity and information dissemination through social media, and economic pressures. Hooghe's perspective underscores the universal aspects of discontent that lead to mass protests while acknowledging the importance of considering local contexts and nuances. This approach aids in comprehending and responding to these protests in a globalized world (Marien and Hooghe, 2011).

Anti-government mass movement arise from tensions in social justice, political and economic realities, and the protesters' actions serve as a tool that many government officials fear and see as a threat to the political system. The global past and current events of protest history represent collective efforts to advocate for change in the political, economic, religious and social issues affecting people. This article thus examined the political trust deficits and EndSARS Protests in Nigeria in age of COVID-19. The next section provides the context of Nigeria's political system and the nature trust deficits and legitimacy crisis as a build up to the theoretical framework for the article. Subsequent sections provided the background to the misconceptions of the EndSARS protests and the role of trust in the instigation of the EndSARS protests in Nigeria.

The Nigerian system and the legitimacy crisis

The departure of the British in 1960 witnessed rising expectations from Nigerian citizens as the country's economic, social, and political sectors suffered drastically from decades of European imperialism. Nationalists who eventually took over the government promised all Nigerians a bright future. This is a situation where colonial exploitation would be replaced by plentiful rewards for hard work and individual citizens would be offered unrestricted opportunities to achieve their legitimate economic and socio-political goals (Njoku et al., 2020).

The history of Nigeria has been wrapped in a robe of leadership failure, taunted by cynical Nigerian citizens working overtime. As a result, in his seminal work The Trouble with Nigeria, Achebe (1983) summarized that the problem with the country is simply a failure of leadership. Three decades later, his observations are still resonating; there are so many points in history where Nigeria had to face anti-government protests which erupts into crisis and conflicts of ethnic and religious diversity however, this time around the ENDSARS protest depicts the mistrust citizens have for the government and that leadership failure has never been more blatant than in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, Nigeria's leadership, in its shaky approach to dealing with emergencies despite timely knowledge of the devastating catastrophe of the pandemic elsewhere, has painted a vivid picture of an uninspiring leadership culture. Nigeria has experienced economic crises in recent years, 2008/2009 and 2016. All of the previous crises in Nigeria are widely believed to be associated with a sudden and prolonged drop in the price of oil in the international market (Cortina and Schmukler, 2018).

The poor leadership of Nigerian leaders since independence has affected the political, social, economic, and health sectors; the decay of the latter led to an increased mortality rate in Nigeria. Therefore, there is a need to grow the economy by exploiting natural resources and investing wealth in critical sectors of healthcare and education. According to Obi-Ani et al. (2020), an ailing economy is feared by those seeking to take over the realms of power; especially since the economy of every nation is the lynchpin of its entire machinery of government. In contrast, this fear has not been shown by Nigerian leaders, who since the country's independence have dashed the hopes of its citizens with gross corruption, tribalism and nepotism (Achebe, 1983). Similarly, the elite group spawned by the country's colonial rulers, which had no revolutionary bent, repeated the same colonial violence (Njoku et al., 2020).

The act establishing the NCDC was signed by President Muhammed Buhari, The establishment of the National Center for Disease Control (NCDC) was officially confirmed and legitimized when President Muhammed Buhari, in his capacity as the head of state, signed the relevant legislation into law. This act of signing signified the government's commitment to and support for the NCDC's mission and objectives, including the prevention, detection, and control of diseases in Nigeria. By putting pen to paper, President Buhari effectively acknowledged the importance of the NCDC's role in safeguarding public health and demonstrated the government's dedication to its functioning and success (Obi-Ani et al., 2020, p. 6). This comes after Bill Gates criticized Nigeria's poor funding of its primary healthcare system (Etteh et al., 2020). However, in the same year, despite criticism from Gates, only N654 million out of a total proposed budget of N1.9 billion was released by NCDC (Chidebe, April 4, 2020).

In 2019, it was hoped that healthcare sector funding would improve dramatically, but amazingly, the year marked the worst budget allocation to NCDC, releasing N224 million from a budget of N1.4 billion. Similarly, in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, only a meager amount was released to the NCDC despite donations to Nigeria from individuals, international organizations and other world governments. As a result, COVID-19 testing labs and centers were sparsely distributed. In a country of over 200 million people, as of April 17, 2020, the country had just 169 ventilators serving an estimated 1,266,440 people per ventilator (Marks, April 18, 2020). Moreover, 70% of the ward health centers are severely outdated, dilapidated and lack essential and affordable medicines, with many epidemiological cases gaining importance.

The country's budget was originally created with an oil price of $57 per barrel (Oluwapelumi, 2020). The post-approval budget became obsolete as a result of the drop in oil prices to $30 barrels caused by the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theoretical framework

Protests are widely discussed aspects of citizens' political participation in the literature. Protests could be linked to broad issues such as political trust deficits, legitimacy crisis and sometimes narrow issues such as reactions to events linked to government policy choices. People take part in protests to express their anger at relative deprivation, frustration, or perceived injustice (Gurr, 1970; Berkowitz, 1972, cited in Klandermans and van Stekelenburg, 2013, p. 888). Wright et al. (1990) also list three characteristics to understand protest as follows:

(i) Protest occurs as an action aimed at improving one's personal situation (individually) or as an action aimed at changing the conditions of a group (collective action).

(ii) The second distinction is between acts conforming to the norm of the existing social system, normative acts such as petitioning and participating in demonstrations.

(iii) Non-normative acts such as illegal protest and civil disobedience (cited in Klandermans and van Stekelenburg, 2013, p. 887).

To this effect, observers of protest movements believe that most anti-government mass- movements are sparked by collective grievances between groups. Protest groups have many strategies to keep the protest going. These include petitions, legal opportunities, lobbying and other means of pressure from the legislature in a democratic state (Wright et al., 1990).

It is largely in the context of diverse theoretical leanings on protests that this article isolates Institutional performance theory as the guiding theoretical framework. It is a framework for understanding how individuals develop trust in political institutions. According to this theory, trust in political institutions is based on how well these institutions perform their functions and how effectively they meet the needs and expectations of citizens. The EndSARS protests in Nigeria provide an interesting case for understanding how institutional performance theory applies to political trust deficits leading to outbreak of mass protests. The EndSARS protests were driven by a low level of trust in the Nigerian Police Force, which had been accused of human rights violations and abuse of authority.

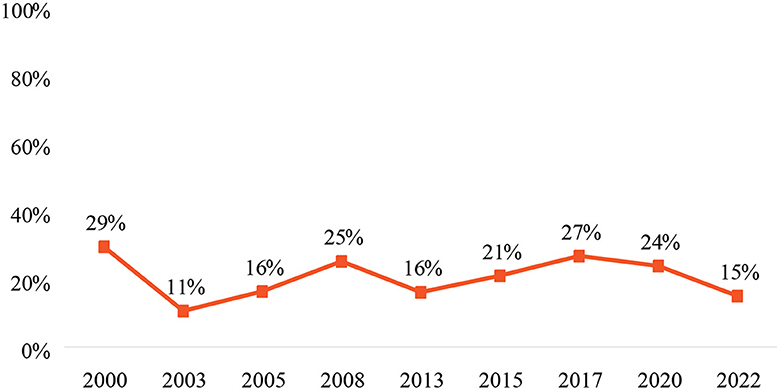

The protesters demanded justice for victims of police brutality and an end to police impunity. As shown in Figure 1 above, these demands were rooted in a belief that the police had failed to perform their functions effectively and had instead become a threat to the safety and security of citizens. Institutional performance theory would suggest that the lack of trust in the police was a result of their poor performance. When citizens believe that the police are not performing their functions effectively, such as ensuring public safety and protecting citizens' rights, they are less likely to trust the institution. This lack of trust can manifest in protests, as citizens demand change and accountability from their political leaders.

Figure 1. Trust the police “somewhat” or “a lot” | Nigeria | 2000–2022. Source: Adopted AFROBAROMETER, 2023; Respondents were asked: How much do you trust each of the following, or haven't you heard about them to say: The police? (% who say “somewhat” or “a lot”).

Furthermore, institutional performance theory suggests that political trust is not static but can change over time. When institutions fail to perform their functions effectively, trust can erode, leading to political instability and unrest. This was evident in the EndSARS protests, which saw widespread demonstrations across the country and demands for police reform and accountability. The protests highlighted the need for institutional change and signaled a loss of trust in the police and the Nigerian government.

Again, institutional performance theory provides a useful framework for understanding how trust in political institutions is developed and maintained. The EndSARS protests in Nigeria demonstrated how a lack of institutional performance, specifically in the case of the Nigerian Police Force, can erode trust in political institutions and lead to widespread protests and demands for change. Institutional Performance Theory is thus premised on the assumption that political leaders must recognize the importance of institutional performance and work to improve the effectiveness of these institutions in order to build and maintain trust among citizens.

The misconceptions of EndSARS as anti-government mass protest

The Nigeria Police Force is one among public institutions in Nigeria with the lowest trust level among the citizens. This is evident from the previous and recent data about citizens' level of trust on public institutions in Nigeria. Impliedly, the public image of the police is very bad. A wide range of fraudulent and illegal practices such as bribery, extortion, torture, illegal arrest and unlawful detention, extrajudicial killings, and ineffective prosecution constitute the image of the police in Nigeria. Many citizens and their loved ones, particularly the youths have been the victims of the police brutal conduct and inefficiency as an institution. The formation of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) further escalated the brutal and corrupt disposition of the Nigeria Police. Thus, at the height of the enforcement of the COVID-19 containment measures, the Police brutality was intensified. This instigated the framing of the EndSARS protests. EndSARS participants held the view that the portrayal of the EndSARS protest as anti-government needed rectification, as they believed this narrative was intentionally propagated by the government to undermine the legitimacy of the protest (Oduala, 2022). The EndSARS protest was about police brutality and human rights violations by SARS and the protesters demanded for justice and police reform.

The mass protests depicted a movement that reflected the outcry of Nigerian Youths across the country while the EndSARS was deeply rooted in the South, parts of the North also joined and participated in the protest. Youth across different socio-economic class were seen on the streets of Lagos, Abuja, and Kaduna participating in the protest hence class was not a defining metric for co-opting protesters as police brutality affected youth as a demography.

The EndSARS protests in Nigeria were not anti-government protests, as some have portrayed them. The narrative that the protests were anti-government was pushed by the government in an attempt to delegitimize the protesters and their demands. The protests were about police brutality and human rights violations committed by the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) of the Nigerian Police Force. The protesters voiced their demands for the cessation of police brutality, seeking justice for victims of such misconduct and advocating for comprehensive police reform. It's crucial to clarify that their objective was not the overthrow of the government, but rather urging the government to tackle the pressing concerns related to police brutality and human rights violations. A prevailing misunderstanding regarding the EndSARS protests is the assumption that they exclusively occurred in the southern region of Nigeria.

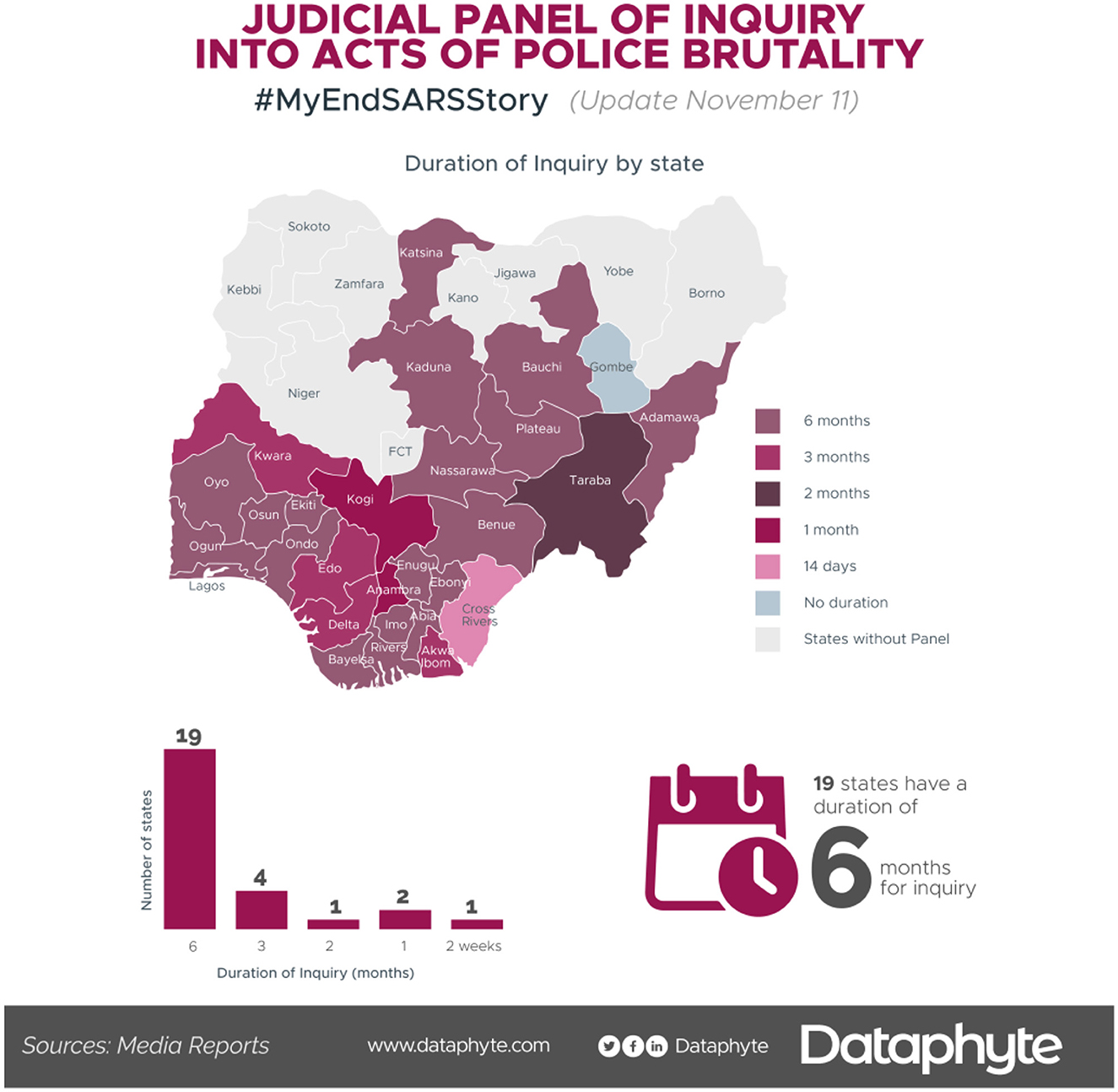

According to Figure 2 above, it shows the duration of Inquiry for Judicial Panels on Police Brutality in Nigeria also suggest some of these states participated in the EndSARS protest. While the protests were more intense in the southern states, there were also protests in the northern parts of the country. In fact, some of the largest protests took place in the northern states of Kano and Kaduna. The protests were a reflection of the widespread discontent with police brutality and human rights violations across the country.

Figure 2. A map of Nigeria showing the judicial panel of enquiry into the Acts of Police brutality across the 36 states.

Moreover, the protests transcended any specific socio-economic class boundaries, with individuals from various walks of life, including students, professionals, and small business owners, taking part in the demonstrations. The reason for this is that police brutality affects everyone regardless of their socio-economic status. The EndSARS protests were a reflection of the frustration and anger of the Nigerian youth, who have been disproportionately affected by police brutality. The youth demographic was the main driving force behind the protests as they have borne the brunt of police brutality for years. Therefore, the protests were not co-opted by any particular class, but rather driven by the shared experience of police brutality among Nigerian youth.

ENDSARS is a youth-led movement in Nigeria demanding an overhaul of how Africa's most populous country is governed, which began with a protest about police brutality and expanded in October into the largest popular resistance the government has faced in years. It encompasses a range of issues, from inequality to corruption and basic distrust of politicians.

The Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) was created in 1984 to combat an epidemic of violent crimes including robberies, car-jackings, and kidnappings. While it was credited with having reduced brazen lawlessness in its initial years, the police unit was later accused of becoming a criminal enterprise that acts with impunity. SARS officers were rarely held accountable for their behavior.

In addition to the against police brutality, the protesters of EndSARS also condemned government's poor response to the coronavirus pandemic, who see it as intertwined with the corruption problem and a glaring example of official indifference to the welfare of ordinary Nigerians (Abang et al., 2021). This clearly depicts a colossal picture of trust deficits amongst the citizens. This makes trust an important issue for the study of protests and social movements. It is a concept that has been studied to an extreme depth in the study of organizations but not much in studies of social movements. The study of trust in protest is important especially in cases of protest movements with no organization such as ENDSARS in Nigeria.

Between 8th to 31st October, 2020, 271 articles were published on the EndSARS protest by Daily Trust Newspaper and 131 by the Vanguard Newspaper. While most of the reports centered around the actions of the government against the Youth protesters, some reported the plight of the angry youths who sought justice. Other reports were reactions of the international bodies and various countries toward the EndSARS, frowning at the way the Federal Government responded to it. The following are the major factors responsible for the lack of trust and justification for the aggravation of the EndSARS protest during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Economic recession

The economic downturns and crises that impacted Nigeria on two occasions in 2020 were attributed to be either a direct or indirect consequence of public health emergencies, notably, the COVID-19 pandemic (Nnamani et al., 2022). As an oil dependent economy, the collapse of oil prices in the international market aggravated the economic stagnation inflicted by the COVID-19 restrictions. Foreign exchange of Nigeria dropped to all time low. Nigeria, like most Sub-Saharan countries, faces several environmental challenges such as slums in urban centers (making social distancing difficult), poor housing conditions, 23 per 1,000 population in Nigeria, with a preponderance of homelessness with 24.4 million homeless in addition to a lack of water and sanitation. Only 26.5% of the population uses an improved source of drinking water (The Guardian Newspaper., 2020). There is also lack of waste disposal options with 23.5% of the population urinating outdoors when there is increased pollution. The high level of pollution, especially in cities like Lagos, is caused by the combination of many high-emission vehicles and frequent traffic jams.

Additionally, this inability to take a systematic approach to combating the pandemic has created tremendous concern among Nigerian citizens, whose anxiety stems from the country's deliberate neglect of the healthcare system. Nigeria's youth population is enormous, accounting for more than 60 percent (This Day 3 November 2020: 32) of an estimated population of over 200 million. With the unemployment rate among the youth rising, co-opting people into the protests (EndSARS) was not a difficult task.

Security/police brutality

Another factor that affects the political trust, which legitimize protests is the security challenge in the country, where security agents abuse the law to brutalize citizens, while many places in the country are controlled by terrorists, bandits, kidnappers and armed robbers. Lekki Tollgate, the galvanizing point for the Lagos protesters, was carefully chosen as it is blatant evidence of repression in the hands of the government. The EndSARS protest was mainly a movement against police brutality, which was heightened when the government adopted the WHO strategies on prevention of COVID-19 spread. The lockdown and the restriction of movement was put in place all over Nigeria and the citizens were not ready to adapt to the conditions, whereas government agents were bent on punishing violators of the new law. Although prior to the COVID-19 pandemic police brutality has been recorded in different parts of the country, it was only intensified during the COVID-19 restrictions order. In June 2020, Amnesty International issued a report that documented at least 82 cases of torture, ill treatment and extrajudicial executions by SARS officers between January 2017 and May 2020. The victims, Amnesty said, were predominantly men ages 18 to 25 from low-income backgrounds and other vulnerable groups. On various occasions (Ibrahim et al., 2016), the Nigerian government has made efforts to reform the police unit, but these attempts have fallen short in resolving the issue. Primarily, the imposed restrictions on movement during the pandemic exacerbated incidents of police brutality in Nigeria, triggering a widespread response from the frustrated youth in the form of street protests under the banner of #EndSARS.

The media

The social media contributed to the framing of the widespread street protests, largely on account heightened anger of the youth when a video went viral showing police blatant brutality, The catalyst seemed to be an Oct. 3rd 2020 video that appeared to show the unprovoked killing of a man by black-clad SARS officers in Ughelli, a town in southern Delta state (Abang et al., 2021). Nigerian officials claimed the video that was widely shared over social media, was fake and arrested the person who took it inciting even more anger. Demonstrations erupted in Lagos, the nation's biggest city, and elsewhere around the country, driven by calls from people many of them young, organizing on social media with the EndSARS hashtag and demanding that the government eliminate the police unit. The hashtag spread internationally, with prominent actors and sports figures from across Africa to Europe and the United States sharing social media posts. The deadly suppression of a peaceful demonstration in the affluent Lekki district of Lagos on October 20th, 2020 compounded by curfews and the deployment of Nigeria's military forces to quell further demonstrations, further angered many people. Several Nigerian youths across the 36 states upon seeing the video took to streets for weeks to demand for the disbandment of the SARS unit of the Police.

Social justice

The Protest began as a peaceful one until the police started to harass and arrest the protesters. In continuing the protest, the youths demanded for the release of their fellow protesters and a compensation for all the victims that were affected. While, the Federal Government agreed to set up a panel of investigation on the police misconduct, the protest continued as a quest for social justice and this was not unconnected with the outcry of the citizens on the government's inability to fulfill its duties on its citizenry.

Amid the pandemic, a reduction in travel led to a consistent decrease in the demand for aviation fuel and premium motor fuel, leading to adverse effects on Nigeria's oil revenues and, consequently, its foreign exchange reserves (Neely, 2005). Supply shocks ensued in the global supply chain as many importers closed their factories and closed their borders. Nigeria was seriously affected as the country's economy is import dependent. It experienced severe shortages of essential commodities such as medicines, spare parts and finished goods from China and other advanced countries.

The level of social division, distrust and hostility toward the government should be underscored as it is believed to be a major source of policy failure, or at least a potential catalyst for undermining of public health responses, which contributed to the spread of the virus and the negation of institutional capacities in the fight against the pandemic. While some respondents argue that participating actively in the protest was to secure a better future for Nigeria and its citizenry, others saw it as a survival protest. According to Oduala (2022) the protest is about advocating against oppression and not becoming a victim of oppression. It is a medium for public awareness where youths can put a spotlight on the injustices that is happening in Nigeria.

The role of trust in political protest and the EndSARS protests in Nigeria

The role of Trust in protest is an important issue for the study of social movements. It is a concept that has been studied to an extreme depth in the study of organizations but not much in studies of social movements. According to Schroeder (2021), trust play a key role in to a successful response to the COVID Pandemic. Mistrust and trust can impede effectiveness of response measures leading to many countries experiencing worse situations, particularly those countries with bad conditions and poor health care infrastructure. Trust has historical element and takes time to build within the society.

Applying institutional performance theory as suggested by Schroeder means behavior should not be theoretical or dramatic, because performance here eludes the actual focal point of the event or situation. The attention is not always on the actual target but reflects the target that is presumed to be the real target. The stakeholders are ignored and the role player becomes important through assumptions. The study of trust in protest is important especially in cases of protest movements with no organization such as EndSARS in Nigeria. While COVID-19 spreads across states in Nigeria, it evades the critical issues facing the Nigerian state and the protest was one out of many outcries of the masses to show loss of trust in the government of the day. The decline in peoples trust to the government accumulated over the years with factors like inadequate health facilities, unemployment rate, poverty and incessant security challenges making it difficult for the citizens to all of a sudden accept the restrictions in movement and the lockdown policy as a result of COVID-19.

The concept of trust plays an important role in political protest. In this article, the concept of trust is examined in the context of EndSARS protests in Nigeria. EndSARS, a peaceful protest against the government, was initiated in 2017 after series of police brutality across Nigeria. In order to ensure the success of the protest, the protesters had to rely on trust in one another. The concept of trust encompasses four key pillars: (1) Trustworthiness, which evaluates an individual's reliability in keeping promises, fulfilling requests, or committing to tasks; (2) Solidarity, indicating the extent to which one can have confidence and reliance on another person; (3) Loyalty, gauging the level of trust in a person's faithfulness and dedication to a particular cause; and (4) Fairness, assessing one's ability to depend on another person to treat them equitably. The first two tenets, trustworthiness and solidarity, play a pivotal role in the success of a protest. Without trust among the protesters themselves, the protest's effectiveness would be compromised, as would be the case if trust in the Nigerian government were absent. To comprehend the influence of trust in mobilizing people for the EndSARS protests in Nigeria, a study was conducted. This study aimed to ascertain the significance of trust and its effectiveness in rallying individuals to support the cause.

The role of trust in political protest is a complex issue for which there is no single answer. Trust is a subjective concept that can vary from person to person. When asked about the role of trust in political protest, the respondents of the study provided a variety of responses. Some of the respondents were in favor of the use of trust in political protest, while others were against it. However, the majority of the respondents agreed that trust is necessary in order to have a successful protest.

Political protests are a fundamental aspect of democratic societies. They serve as a means for citizens to express their grievances and demands, particularly when they feel that their voices are not being heard. In many cases, protests have led to significant changes in government policies and laws. However, protests can also be dangerous, particularly when they involve clashes with law enforcement agencies or government officials. Trust is a critical factor that determines the success or failure of a protest movement.

The recent EndSARS protests in Nigeria serve as an example of the critical role of trust in political protests. The EndSARS protests began in October 2020 as a peaceful movement to demand the disbandment of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), A police unit with a notorious reputation for engaging in extrajudicial killings, torture, and extortion of Nigerian citizens (Punch, 2023).

The protests swiftly escalated into violence, resulting in the loss of lives and damage to property. The Nigerian government's response to the protests faced widespread criticism for its heavy-handedness and perceived lack of empathy, eroding the trust of citizens in their government. The forceful crackdown on protesters at the Lekki Tollgate by the military, which resulted in the tragic deaths of numerous young individuals, sparked outrage against the Nigerian government's repressive measures aimed at suppressing legitimate protests. There have been allegations of the military being involved in the removal of bodies in an attempt to conceal evidence. Reports of individuals missing at the protest sites further compounded the existing trust deficits.

These brutal and repressive reactions of the government on the EndSARS protesters intensified the demand for justice, transparency and accountability of the government. The EndSARS protests in Nigeria reinvented the discourse of trust at different levels of the protests.

(i) Trust in government is essential in determining the success or failure of a protest movement. When citizens believe that their government is mired in corruption or unresponsive to their concerns, they are more inclined to resort to protests as a way of instigating change. In the context of the EndSARS protests, the dearth of trust between citizens and the government acted as a catalyst for the protests.

(ii) Despite promises of police reform and compensation for victims, many Nigerians felt that their government was not sincere in addressing their concerns.

(iii) Trust in protest leaders is also crucial in determining the success or failure of a protest movement. During the EndSARS protests, several groups emerged as leaders, including activists, celebrities, and influencers. These leaders assumed pivotal roles in orchestrating the protests, mobilizing backing, and offering a cohesive front. Nonetheless, allegations arose against certain leaders, accusing them of misappropriating funds designated for the protest, resulting in a decline of trust among the protesters (Punch, 2023). In certain cases, tensions escalated within the protest movement, leading to its fragmentation.

(iv) Trust in law enforcement is another critical factor in determining the success of a protest movement. Regarding the EndSARS protests, the protesters' central demand centered on the dissolution of the notorious SARS unit, known for its involvement in extrajudicial killings and various human rights abuses. When citizens witness corruption or abusive behavior within law enforcement agencies, their willingness to cooperate or adhere to their directives diminishes (Aljazeera, 2020).

(v) During the EndSARS protests, there were reports of police brutality and harassment of protesters, which further eroded trust between citizens and law enforcement agencies.

The EndSARS protests in Nigeria were fueled by a lack of trust between citizens and law enforcement agencies. The protesters believed that the police were guilty of human rights violations and abuse of power, and they demanded justice and accountability for these crimes (Adegoke, 2020). The government set up panels to investigate these allegations and to make recommendations on how to address them. Despite the protesters' initial trust in the government to abide by the recommendations of these panels, the lack of action taken so far has eroded that trust even further. The fact that the panels were set up in the first place indicates that there was some level of trust between the protesters and the government. The protesters believed that the government was serious about addressing their concerns and that the panels would provide a path toward justice and accountability.

However, the lack of action taken by the government has eroded this trust. The delay in implementing the recommendations of the panels has led to frustration and disappointment among the protesters. Many believe that the government is not serious about addressing the issue of police brutality and that the panels were set up as a way to placate them without actually addressing the root causes of the problem. Moreover, the discovery of palliative warehouses across the country during the protests further eroded the trust of the protesters in the government. The fact that these warehouses were filled with supplies that were meant for distribution to citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic but were hoarded by government officials showed that the government was not only indifferent to the plight of the people but also actively working against their interests.

Again, the lack of trust between the protesters and enforcement agencies was a major catalyst for the EndSARS protests. While the initial trust in the government to abide by the recommendations of the panels set up to address police brutality was present, the lack of action taken so far has eroded this trust even further. It is imperatively expected, given the severity of the protests that the government would take concrete actions to address the issues raised by the protesters, implement the recommendations of the panels, and work toward rebuilding the trust of the people in their institutions but to no avail.

Building trust in political protests requires a multi-faceted approach that involves the government, protest leaders, and law enforcement agencies. One of the critical ways to build trust is through transparency and accountability. In the case of the EndSARS protests, the Nigerian government could have been more transparent in its efforts to address police brutality and compensate victims. Additionally, protest leaders are also required transparent in their use of funds and communication regularly with protesters in order to build trust. Another critical trust issue is dialogue and engagement with stakeholders. In the case of the EndSARS protests, the Nigerian government could have engaged with protesters and established a framework for dialogue to address their concerns. Law enforcement agencies should have engaged with citizens to build trust and reduce tensions during protests.

Conclusion

Many societies faced existential threats at the heights of COVID-19 pandemic. The ravaging trend of the virus across the world and the colossal death tolls and health emergency that trailed many states, particularly in the developed societies, has redefined state-society relations. EndSARS is a youth-led movement demanding an overhaul of how Africa's most populous country is governed. It encompasses a range of issues of social injustice from inequality to corruption, human rights violations to fundamental issue distrust of politicians.

During the pandemic, Nigeria's main source of foreign exchange stagnated as a result low demand for oil as a result of industrial shutdowns. As an import-dependent economy, Nigeria experienced acute shortages of essential commodities such as medicines, spare parts and finished goods from other parts of the world. This literally strained and stressed the economy into two circles of recession. The study argued that the recession and economic crises that hit Nigeria twice in 2020 were believed to be caused directly or indirectly by public health crises of the COVID-19 pandemic, which closed down the global economy that hit harder on the mono-cultural and import-dependent economy of Nigeria. The resulting adversity exacerbated by the imposed restrictions worsened the daily livelihood of the populace. This was further compounded by the brutal dispositions of the security agents, particularly the police, which infuriated an already frustrated youth population leading to the outbreak of the EndSARS protests. The level of social division, distrust and hostility toward the government has been underscored. It is believed to be a major source of policy failure, or a potential catalyst for the undermining of public health responses. Findings also show that the Nigerian government has in different occasions attempted police reforms but with little or no success. This study therefore concludes that Trust can also be achieved through output sense, the provision of public goods, or social support. Building trust is particularly important for governments, as this will enable them to govern without coercion. To sum it up, the role of trust in political protests cannot be overstated. Trust in government, protest leaders, and law enforcement agencies is crucial in determining the success or failure of a protest movement. Building trust requires a multi-faceted approach that involves transparency, accountability, and dialogue. The recent EndSARS protests in Nigeria serve as a reminder of the importance of trust in political protests and the need for all stakeholders to work toward building and maintaining trust to ensure peaceful and successful protests. Thus the lack of trust in public institutions or the government as a whole could be existing over time, and for a long period without much collective reactions by the citizens. However, occasions such as the COVID-19 emergency situations could be a fertile ground for the eruption of mass protests and/or civil disobedience that could be beyond the capacity of the state to handle. In Africa and particularly Nigeria, the COVID emergency period provided the enabling environment for the outbreak of the mass protests against police brutality tagged “the EndSARS.” Similar emergency situations in Africa such as election periods could also be exploited for mass unrest and protests in response to huge trust deficits for public institutions or the government as a whole.

Author contributions

KS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YB: Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor CL declared a passed collaboration with the author KS at the time of review.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abang, S. O., Akpan, E. E., Uko, S. U., Ajayi, F. O., and Odunekan, A. E. (2021). COVID 19 protest movement and its aftermath effect on the Nigerian state. J. Public Admin. Finance Law 20, 7–18. doi: 10.47743/jopafl-2021-19-01

Adegoke, Y. (2020). Nigeria's EndSARS protests have been about much more than police brutality. Quartz Africa.

Aljazeera (2020). Nigeria's SARS: A Brief History of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad | Protests | Al Jazeera 2020. Available online at: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/10/22/sars-a-brief-history-of-a-rogue-unit (accessed March 24, 2024).

Berkowitz, L. (1972). Frustrations, comparisons, and other sources of emotion arousal as contributors to social unrest. J. Soc. Issues 28, 77–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1972.tb00005.x

Carnegie (2022). Global Protest Tracker - Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available online at: https://carnegieendowment.org/publications/interactive/protest-tracker (accessed March 24, 2024).

Cortina, J. J., and Schmukler, S. L. (2018). Research and policy briefs. The Fintech Revolution: A Threat to Global Banking, 4. Available online at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/516561523035869085/pdf/125038-REVISED-A-Threat-to-Global-Banking-6-April-2018.pdf (accessed March 13, 2022).

Etteh, C. C., Adoga, M. P., and Ogbaga, C. C. (2020). COVID-19 response in Nigeria: health system preparedness and lessons for future epidemics in Africa. Ethics, Med. Public Health 15:100580. doi: 10.1016/j.jemep.2020.100580

Hartwig, R., and Hoffmann, L. (2021). Focus | AFRICA Challenging Trust in Government: COVID in Sub-Saharan Africa. GIGA Focus | Africa | Number 3. Available online at: www.giga-hamburg.de/en/publications/giga-focus/

Ibrahim, B., Saleh, M., and Mukhtar, J. I. (2016). “An overview of community policing in Nigeria,” in A paper presented in International Conference of Social Science and Law-Africa (ICSS Africa). Nigerian Turkish Nile University (NTNU). Available online at: https://gsdrc.org/document-library/an-overview-of-community-policing-in-south-africa/#:~:text=Thebiggestproblemsoccurwhere,hasnotundertakenradicalreform

Jennings, W., Valgarð*sson, V., Stoker, G., Devine, D., Gaskell, J., and Evans, M. (2020). Political Trust and the Covid-19 Crisis: Pushing Populism to the Backburner? A Study of Public Opinion in Australia, Italy, the Uk and the USA. Available online at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c21090f8f5130d0f2e4dc24/t/5f71a55572b74043619ae25b/1601283437226/Published+report+-+covid_and_trust.pdf (accessed March 18, 2022).

Keele, L. (2007). Social capital and the dynamics of trust in government. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 51, 112–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00248.x

Klandermans, B., and van Stekelenburg, J. (2013). “Social movements and the dynamics of collective action,” in The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, eds L. Huddy, D. O. Sears, and J. S. Levy. 774–811.

Kumlin, S. (2017). The welfare state and political trust: bringing performance back in staffan. Handb. Polit. Trust 1999, 1–6. doi: 10.4337/9781782545118.00029

Marien, S., and Hooghe, M. (2011). Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance. Eur. J. Polit. Res. 50, 267–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01930.x

Neely, C. J. (2005). An analysis of recent studies of the effect of foreign exchange intervention. FRB of St. Louis Working Paper No. doi: 10.20955/wp.2005.030

Njoku, L., Godwin, A., Akinboye, O., and Agboluaje, R. (2020). Endsars Protest Renews Debate for, against State Police. Lagos.

Nnamani, K. E., Ngoka, R. O., Okoye, K. M., and Nwoke, H. U. (2022). The Nigerian state and the realities of managing COVID-19 pandemic: whither political restructuring and economic diversification? African Ident. 2022, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/14725843.2022.2028603

North, D. C. (1990). A transaction cost theory of politics. J. Theor. Polit. 2, 355–367. doi: 10.1177/0951692890002004001

Obi-Ani, N. A., Anikwenze, C., and Isiani, M. C. (2020). Social media and the Covid-19 pandemic: observations from nigeria. Cogent Arts & Humanities 7:1. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2020.1799483

Oduala, R. (2022). EndSARS Report: I Do Not Regret Pulling out of Lekki Panel, Says Activist Rinu Oduala - Punch Newspapers. Punchng. Available online at: https://punchng.com/endsars-report-i-do-not-regret-pulling-out-of-lekki-panel-says-activist-rinu-oduala/ (accessed March 24, 2024).

Oluwapelumi, E.-A. (2020). Covid-19 and Democratic Backsliding. Linnaeus University Sweden. Available online at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1565223/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed May 14, 2021).

Punch (2023). #EndSARS: Police Atrocities Could Provoke Fresh Protests. Punchng. Available online at: https://punchng.com/endsars-police-atrocities-could-provoke-fresh-protests/ (accessed March 23, 2024).

Rieger, M. O., and Wang, M. (2022). Trust in government actions during the COVID-19 crisis. Soc. Indic. Res. 159, 967–989. doi: 10.1007/s11205-021-02772-x

Schroeder, S. A. (2021). Democratic values: a better foundation for public trust in science. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 72, 545–562. doi: 10.1093/bjps/axz023

Van der Meer, T., and Hakhverdian, A. (2017). Political trust as the evaluation of process and performance: a cross-national study of 42 European countries. Polit. Stud. 65, 81–102. doi: 10.1177/0032321715607514

WHO (2023). Coronavirus Disease (Covid 19) Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus

Keywords: political trust, legitimacy crisis, COVID-19, mass anti-government protests, Nigeria

Citation: Sanusi Gumbi K and Baba YT (2024) Political trust and legitimacy crisis in the age of COVID-19: an assessment of the EndSARS protest in Nigeria. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1334843. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1334843

Received: 07 November 2023; Accepted: 13 February 2024;

Published: 24 April 2024.

Edited by:

Carl LeVan, American University, United StatesReviewed by:

Oluwakemi Udoh, Covenant University, NigeriaKemi Okenyodo, The Rule of Law and Empowerment Initiative, Nigeria

Copyright © 2024 Sanusi Gumbi and Baba. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Khadijah Sanusi Gumbi, Z2FkZWVndW1iaUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Khadijah Sanusi Gumbi

Khadijah Sanusi Gumbi Yahaya T. Baba2

Yahaya T. Baba2