95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 07 June 2024

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1334827

This article is part of the Research Topic Trust, Participation and Pandemic Politics in Africa View all 5 articles

The COVID-19 pandemic generated an unprecedented global crisis with long-lasting consequences. In this study, I examine the bi-directional nexus between public trust and the management of the pandemic in Nigeria. I argue that there is a relationship between government management of public policies and the level of public trust. The research draws on the Theory of Trust, in-depth interviews (IDI), and focus group discussions (FGD) and is supported by other secondary sources. I found that the main reason for citizens’ resistance to major policies introduced to contain the spread of the pandemic was due to an entrenched lack of trust in the government, its agencies, and officials. The findings also indicate that a lack of transparency and accountability in the management of the pandemic deepened the already fractured public trust. This was particularly visible in the shrouded pattern of disbursing cash transfers, allegations of corruption against the managers of the pandemic, and evidence of concealed palliatives meant to cushion the negative economic effects of the pandemic. The article recommends that the government needs to promote public trust by adopting an open governance approach that institutionalises transparency and accountability, fosters constant and consistent citizen engagement on government policies and programmes, strengthens critical agencies, and engenders a sense of belonging for all citizens.

Public trust is one of the important ingredients with which the legitimacy and effectiveness of government can be realised and even sustained. Scholars have stated that public trust is crucial for political participation, social cohesion, and galvanising public support for effective implementation of public policies (Marien and Hooghe, 2010; Kumagai and Iorio, 2020; Holum, 2022). However, public trust in government, politicians, government institutions, and its officials has been eroding, giving rise to heated debates about the health and stability of democratic systems around the world (Citrin and Stoker, 2018; Bertsou, 2019). Bertsou (2019) argued that citizens’ mistrust of government has become the norm rather than an exception since the 1970s, when the scholarly community was first alerted to the trends of declining political trust across established democracies. Declining public trust contributes to non-compliance with government directives and policies, including non-payment of taxes by citizens and other serious concerns (Jung and Sung, 2012; Tanny and Al-Hosseinie, 2019; UNDP Oslo Governance Centre, 2021). This is because without public trust in government, its institutions lack a reservoir of goodwill to support policy implementation; support for necessary reforms will be difficult to mobilise (OECD, 2013; Hetherington and Rudolph, 2015).

That is why scholars have been arguing for a deliberate investment in trust because it constitutes a new and central approach to restoring economic growth through support for government policy innovations that may trigger instant economic hardship (Mikitin, 1995; OECD, 2013). Bertsou (2019) finds that citizens who trust their government and political institutions behave in a cooperative manner, complying with policy decisions regardless of the outcome and, in turn, allowing political institutions to function efficiently. The degree to which institutions are responsive and reliable in delivering policies and services and act with openness, integrity, and fairness are important drivers of trust in government institutions (OECD, 2022). This article, using Nigeria as a case study, considers whether distrust arises as an expression of dissatisfaction towards underperforming incumbents or if it is an inevitable by-product of rising citizen expectations, as demonstrated by scholars such as Bertsou (2019). With a population of over 218 million (World Bank Data, 2022) and a governance deficit (Adeyemo et al., 2012; Hamalai et al., 2015; Mutiullah et al., 2016; Tolu-Kolawole, 2022) over the years, Nigeria’s public trust challenges are significant.

Suffice it to note that Nigeria is a sovereign country located in the area of West Africa, bordering on the west by the Republic of Benin and the Republic of Cameroon, on the south by the Atlantic Ocean, and on the north by the Niger Republic and the Republic of Chad. The country has a total area of 923,769 sq. km (Onah, 2014), a little more than twice the size of California and the third largest country in Sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, it lives on the fear of suspicion due to its heterogeneity in terms of hundreds of ethnic groups and religious organisations. There are many ethnic groups, roughly categorised into the majority ethnic groups and the minority ethnic groups. The majority groups are, namely, the Hausa-Fulani of the North, the Yoruba of the South-West, and the Igbo of the South-East. The so-called minority ethnic groups (about 250) are scattered throughout the country (Osaghae, 1998). The country, which gained independence in 1960, has witnessed military coups (January 1966, July 1966, July 1975, December 1983, August 1985, and November 1993) and coup attempts (February 1976 and April 1990) because of various corruption and administration deficiency allegations (Kemence, 2013). However, the reoccurring circumstances of governance and administration deficits in the current fourth republic are affecting public trust in government activities, leading to stiff resistance towards major public policies.

The low level of trust by the citizens in the state was an issue defining state–society relations long before COVID-19. This mistrust stems from several factors, including prolonged mismanagement of public affairs, poor economic performance, an increasing rate of unemployment, gagged freedom of speech and media, a lack of basic amenities, the management of corruption, heightened insecurity, and bad leadership (Saka, 2020). These, to a greater extent, affected some of the policies of the government during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), including hand washing, social distancing, travel restrictions, school closures, restrictions on businesses, closures of activity in places (lockdowns), mask mandates, and restrictions on working and socialising; and the test-trace-isolate-track (TTIT) system introduced at the both initial and advance stages of the pandemic to slow down and curtail the spread.

This bi-directional nexus between public trust and the management of the pandemic in Nigeria generates a pair of questions: first, how has the level of public trust affected the management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria? Second, and more specifically, how did the management of the COVID-19 pandemic shape (increase, sustain, or reduce) public trust in Nigeria? In other words, what did the government do or fail to do during the COVID-19 pandemic to increase or reduce public trust? To answer these questions, the application of qualitative research methods supported by other authoritative secondary sources was adopted in the study. Following this introduction, the article proceeds to discuss the theory related to trust, research design, discussion of findings and results, and then a conclusion with policy recommendations. The answers to these questions are crucial to understanding the extent to which public trust could either weaken or enhance the performance of public policy.

The basic idea of trust is said to be based on reliance, which comes from experience, encounter, and performance (Wierzbicki, 2010). Wierzbicki (2010) argued that the experience that culminated into trust (and/or distrust) is a relationship between a trustor and a trustee. The existence of this relationship can be represented as a specific state of the trustor, especially within the context of how the trustor manages the affairs of people and the properties put in his/her care. While placing special attention on belief, evaluations, and expectations, Castelfranchi and Falcone (2011) explained that trust is basically a mental state, a complex attitude of an agent X towards another agent Y about the behaviour/action relevant to the result (goal) (p. 64).

The study adopts the three constructs from McKnight and Chervany’s (1996) model with the basics of trust, such as trusting beliefs, trusting intention, and trusting behaviour as defined in Table 1.

The study relied on the Theory of Trust as the lens of interrogation. Throughout the article, the term human trust refers to a mental state of humans that affects behaviour towards an object, an individual or group, an entity, etc. The way and purpose of such a concept in this article have to do with the relationship between the state (country) and its citizens and, more importantly, how such a relationship affects duties and responsibilities at both ends. The benefit of a trusting relationship is that people are more likely to comply with public policies during periods of crisis or uncertainty, such as the recent pandemic.

This research is anchored on the application of the qualitative research method, supported by other authoritative secondary sources. Specifically, a non-probability purposive sampling approach was used for the study (Babbie and Mouton, 2011; Gray, 2014) to select core participants in the COVID-19 pandemic management, oversight, and public reactions that led to the spontaneous nationwide protests, anger, and attacks on major government stores between 8 October 2020 and November 2020. As explained by Babbie and Mouton (2011), purposive sampling assists the researcher in studying a select group of participants that are able to provide informative and adequate responses to the research questions. Thus, the research primarily collected data through in-depth interviews (in-person and/or through telephone) with nine (9) key players in the management of COVID-19 such as the Chairman, House Committee on COVID-19 Pandemic (P1), National Coordinator, Presidential Taskforce on COVID-19 (P2), representatives of the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management (P3), Ministry of Finance (P4), Ministry of Information (P5), and civil society organisations (independent COVID-19 funds oversight groups) such as BudgIT (P6), Policy and Legal Advocacy Centre (PLAC) (P7), Yiaga Africa (P8) and two (2) academic members from the University of Abuja (P9) and the National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies (NILDS) (P10).1

Research also entailed Focused Group Discussions (FGDs) for major participants in the spontaneous attacks and looting of palliative stores in five major affected states (Lagos—FGD 1, Federal Capital Territory-Abuja—FGD 2, Plateau—FGD 3, Kaduna—FGD 4, and Cross Rivers—FGD 5).2 The two sides of IDI and FGD provided a detailed and balanced information into what could have triggered such spontaneous actions and inactions of the public to government efforts during the pandemic.

It also made use of social media data mining (Facebook—SMDM 1, Instagram—SMDM 2, and Twitter—SMDM 3),3 especially various protest videos and major television discussions and analyses. The triangulation of these sources explained various contours and variations in the perceptions of the public and stakeholders on the issue of trust and the management of COVID-19.

To assess the level of trust in the Nigerian government over time, the study utilises extant data such as the International Budget Partnership (IBP), Afrobarometer, Transparency International (TI), and content analysis of newspapers to understand the aged performance issue of government as well as the current status of public perception of transparency and accountability in government affairs.

In the sampling method, and importantly, to identify and reach out to the respondents, the study used purposive and snowball sampling methods. This is because the study could easily identify the stakeholders within the government and citizens, which translated into the identification of others in the management of COVID-19 and the citizens’ responses to the government’s efforts. The sample size was determined by the extent of access and linkages to various respondents through purposive and snowball. Ethically, the study involving human participants was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies. The participants provided their written informed consent for participation in the study.

Using the theoretical framework developed by McKnight and Chervany (1996), the article seeks to explain citizens’ reactions during the pandemic. The goal of the study is to gather enough evidence to inform our understanding of public trust across different groups from the north, west, and south of the country. One of the first findings that became apparent from the data, despite the different cultural and religious background and orientations, is that participants who explained their experience and opinion of government followed the same direction, and its analysis contributed to rebuilding the existing knowledge base on trust and affected public policy formulation and implementation. While there are varying instances, the way they expressed their disappointments, which informed the level of trust in government intentions, policies, and activities, is the same. The analysis and discussion presented below are conducted using all materials from primary (KII and FGD), secondary (literature, Afrobarometer, TI-CPI, and IBP), and social media data mining (from Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter). The KII and FGD were done in the language participants employed in the discourse.

Another finding shows that Nigerians trusted the government more in the post-independence decades of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. As espoused by McKnight and Chervany (1996), most citizens hoped to benefit from democratic dispensation and good governance (FGD 1, FGD 2, FGD 3, FGD 4, and FGD 5). However, the hardship in economic activities, rising inflation, and heightened unemployment, coupled with the insecurity, worsen trust (FGD 1, FGD 2, FGD 3, FGD 4, and FGD 5). Such trusting intention and behaviour were diminishing. Meanwhile, events between 2015 and 2023 were one of the many periods that have aggravated public distrust in the government, including what the government did or failed to do during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this section, the drivers of trust as provided by the OECD (2022) as education, health, security, and corruption were used to explain the current status of public trust in Nigeria. Despite the enactment of the Freedom of Information Act (2011) and the constitutional responsibility of the legislature, records indicate a lack of openness, integrity, fairness, transparency, and accountability in the activities of government, which has continuously triggered public mistrust in government, its institutions, and officials (P5, P6, P7, and P8).

This has affected a number of good policies, such as the removal of fuel subsidies, an increase in taxes, and recent issues surrounding the management of the COVID-19 pandemic (P5). At the height of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, when the world was mourning and counting its casualties, Nigerians were violating the government’s directives on social distancing, travel restrictions, restrictions on businesses or closures of activity in places or sectors (“lockdowns”), mask mandates, and socialising (Gulleng and Musa, 2020; Saka, 2020; Shodunke, 2022). In the later years, when the vaccine was ready to be administered, fewer people were ready to be vaccinated (Afrobarometer, 2022, June 7). To understand the Nigerian issue of public mistrust and how it has affected the management of COVID-19, the major drivers of mistrust as highlighted by the OECD (2022) were used as indicators to measure government performance as follows:

The challenges associated with public trust by the government, its institutions, and officials are caused by the long years of non-performance of the state in the provision of public goods. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2022) highlighted major drivers of trust in government institutions as the degree to which institutions are responsive and reliable in delivering policies and services and act in line with the values of openness, integrity, and fairness, as well as the government’s capacity to address essential services such as education, health, security, job creation, etc. Specifically, the major drivers of mistrust as highlighted by the OECD were used one after the other to explain issues of public trust in Nigeria.

For instance, Nigeria’s educational system is suffering from deteriorating infrastructure, inadequate welfare and incentives for teachers and lecturers, ill-prepared personnel, and incessant strike actions at all levels. In 2022, the Academic Staff Union of the Universities (ASUU) launched a strike action that lasted for 8 months (Tolu-Kolawole, 2022). From 1999 to June 2022, ASUU, an umbrella body of the teaching staff of federal and state government-owned universities in Nigeria, used a total of more than 1,420 days to go on strike.4 Meaning, close to 4 years had gone by since the boycott of classrooms by the lecturers and the blackout of the knowledge base of the country and the young generation. However, the data presented have not included other university unions or other tertiary institutions’ strike actions. This, amongst others, contributed to the non-competitive and weak status of Nigerian education amongst the community of nations. As of January 2022, Nigeria’s best university—University of Ibadan—is 1,172nd in the world with impact ranks—2,251 and excellence rank—1,373 (Centre for World University Rankings, 2022). As the population keep increasing, access, quality, and output are seriously affected, and citizens continue to face the challenges of access, though infrastructure is really in a bad state. The supervising entrance institution, the Joint Admission and Matriculation Board (JAMB), has limited space as millions of applicants are emerging every year. Data available revealed that between 2010 and 2015, 26% of the 10 million applicants gained entry into Nigerian tertiary institutions (Kazeem, 2017). Nearly the same result was recorded in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Just like in education, infrastructure decadence, brain drain, low doctor-to-patient ratio, and incessant strike actions by health workers have crippled the services within the health sector in Nigeria. Of the total 187 months spent between 29 May 1999 and 31 December 2014, 80 months (representing 43%) recorded one form of strike or another ranging from warning strikes of a few days to indefinite strikes that lasted months (Hamalai et al., 2015). In addition, between 2013 and 2021, another report from the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR) stated that Federal Government-run hospitals in Nigeria lost about 300 working days between 2013 and 2021 (ICIR, 2021, December 17). Typically, strikes rupture operations of health facilities, prevent access to healthcare, which is a constitutional right of citizens, and worsen Nigeria’s health status in the global ranking. Nigeria improved with a lower rate in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) health system ranking from 187 out of 191 countries in 2001 (two decades ago) to 163 out of 191 countries in 2021 (The Guardian Newspaper, 2021b, November 26). It also suffers from lower health personnel compared to the population. At present, Nigeria has a doctor-to-population ratio of about 1:4,000–5,000, which falls far short of the WHO recommended doctor-to-population ratio of 1:600 (The Guardian Newspaper, 2022, April 24). Unfortunately, a higher number of Nigerian health workers are scattered all over foreign countries, while hundreds of others are busy applying for visa abroad.

In the security sector, Nigerians have been facing major attacks from left and right, front and back. From extremism in the North to separatist insurgency in South-East, banditry and kidnapping in the North-West and North-Central, herders-farmers clashes in South-West and North-Central, oil militancy in the South–South, and other violent attacks, human lives are lost or permanently damaged (Tanko, 2021, July 19), and faith in state and its institutions is diminishing. Confronted with a seemingly helpless situation, state governors and political leaders in the Nigerian federation have resorted to self-help, setting up regional security outfits (This Day Newspaper, 2021, June 28) and directing residents of the state to acquire guns to defend themselves against the predators (Maishanu, 2022, June 26). Unfortunately, security architecture at all levels is weak and cannot combat the criminal tendencies of the society. Various groups and individuals are easily terrorising the lives of the citizens without consequence. That gives more groups of kidnappers and criminals to surface. Over time, Nigerians have witnessed a devastating effect of insecurity. There are incidences ranging from kidnapping for ransom to ritual killings, assassination, attacks on schools, detaining and torturing students and teachers, armed robbery, banditry, and insurgency. According to the Nigeria Security Tracker (NST) of the Council on Foreign Relations, as of March 2022, Nigeria has recorded 87,903 deaths from all forms of violent attacks. Unfortunately, the efforts of the government and its related agencies are not significant. This makes average Nigerians secure vigilante or private security personnel to guarantee their safety.

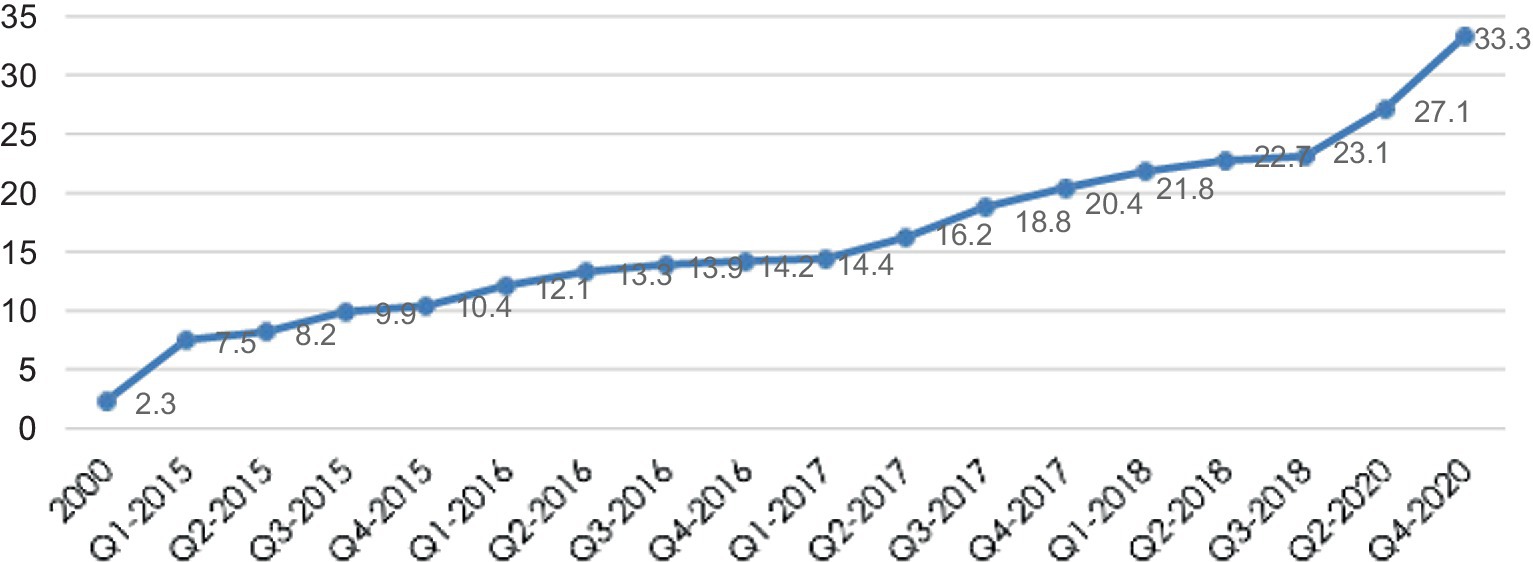

The state of security, as described above, is compounded by the increasing unemployment situation in the country. The government has neither been able to provide jobs nor conducive environment for the investors who could provide alternatives to public space. Since 1999, unemployment rates have kept increasing (see Figure 1), while the tertiary institutions kept producing millions every year for the economy. Thus, leaving millions of new entrants to shrouded fate.

Figure 1. Rates of unemployment in Nigeria (%), 2000–2020. Source: National Bureau of Statistics Labour Force Report (2000–2020).

Some research links this high unemployment rate with social, psychological, and economic consequences such as an increase in crime rate, loss of respect and identity, reduction in purchasing power, psychological injuries, and corruption, amongst others (Omitogun and Longe, 2017).

Another trigger of mistrust between the public and the state is the increasing magnitude of corruption, especially by high-profile officials and the institutions of government. The rate of corruption in Nigeria persists at an alarming rate, to the extent that Nigeria was ranked 52 as the least corrupt nation out of 175 countries in 1997, only to jump to 152 in 2005. According to the 2019 ranking, Nigeria is now the second most corrupt ECOWAS country (Transparency International, 2018, 2019). In 2020, corruption in Nigeria increased to 149 (Transparency International, 2020) out of 180 countries surveyed (see Figures 2–4). Meanwhile, there is other evidence likening the management of the Nigerian state to corruption, lack of transparency, accountability, and fiscal indiscipline (Adeyemo et al., 2012; Uzor, 2017). Mutiullah et al. (2016) stated that the primordial instinct of the ruling elite is to loot the national treasury, perpetuate themselves in power, and brutally suppress all dissent and opposition. Worse, the booty is not invested in Africa but in foreign banks and countries. As a matter of fact, a former Head of State has been humorously described as one of the ancestors of Nigeria who has been donating money generously to successive governments from the land of the dead, as his loot was outrageous (Nwabughiogu, 2020). Sani Abacha looted an estimated $5 billion during his tenure from 1993 to 1998 (8 March 2020). The most recent account of prominent and politically motivated corrupt practices with its proceeds as deduced from the newspapers include: N24 billion Police Pension Scam (Premium Times, 2016, February 10), Ekiti electoral gate in 2016, Oil Subsidy Scam, Malabo oil deal involving former Attorney General of the Federation (AGF), 15 million dollar arms scandal transported and intercepted in Johannesburg in 2014 (Ibekwe, 2014), 13 March 2015 Abba Moro’s Nigeria Immigration Service job recruitment scandal, National Assembly’s subsidy probe scandal involving $3 million; and recently N109 billion naira fraud charges against the suspended Accountant General of the Federation by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) (Premium Times, 2022, July 21).

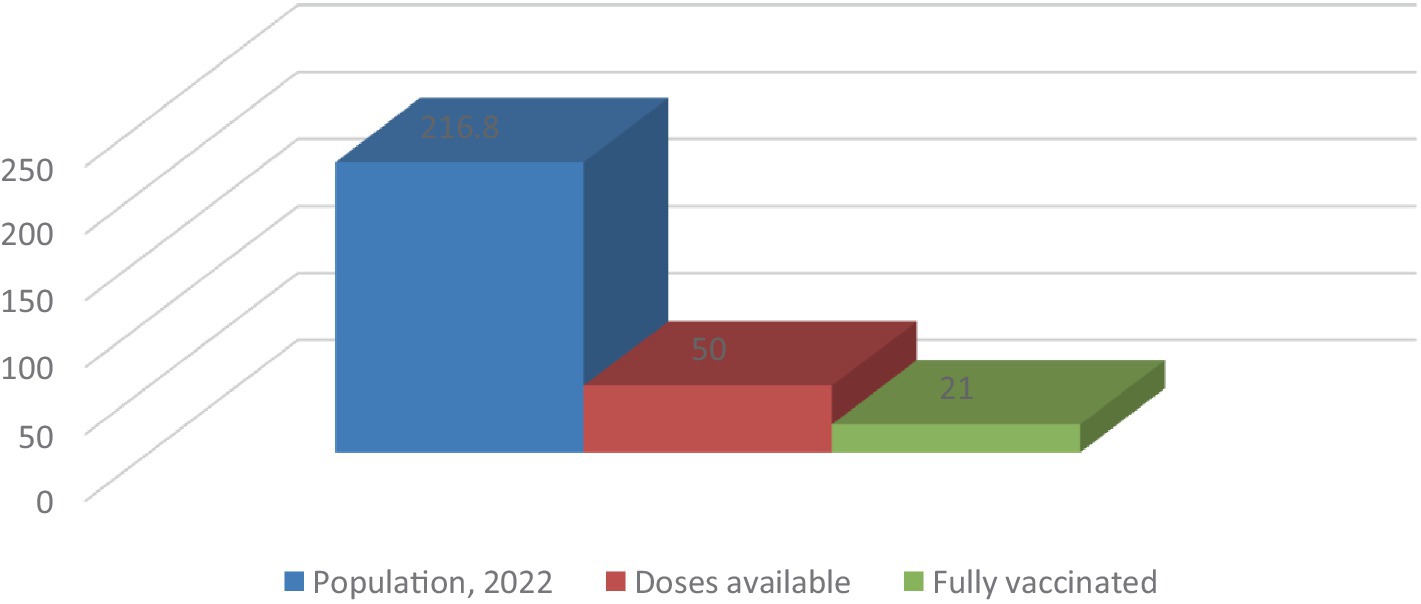

Figure 2. Nigeria’s population, available vaccine, and fully vaccinated as of 30 June 2022. Source: Worldomerter, 30 June 2022 and WHO Coronavirus Dashboard, 30 June 2022.

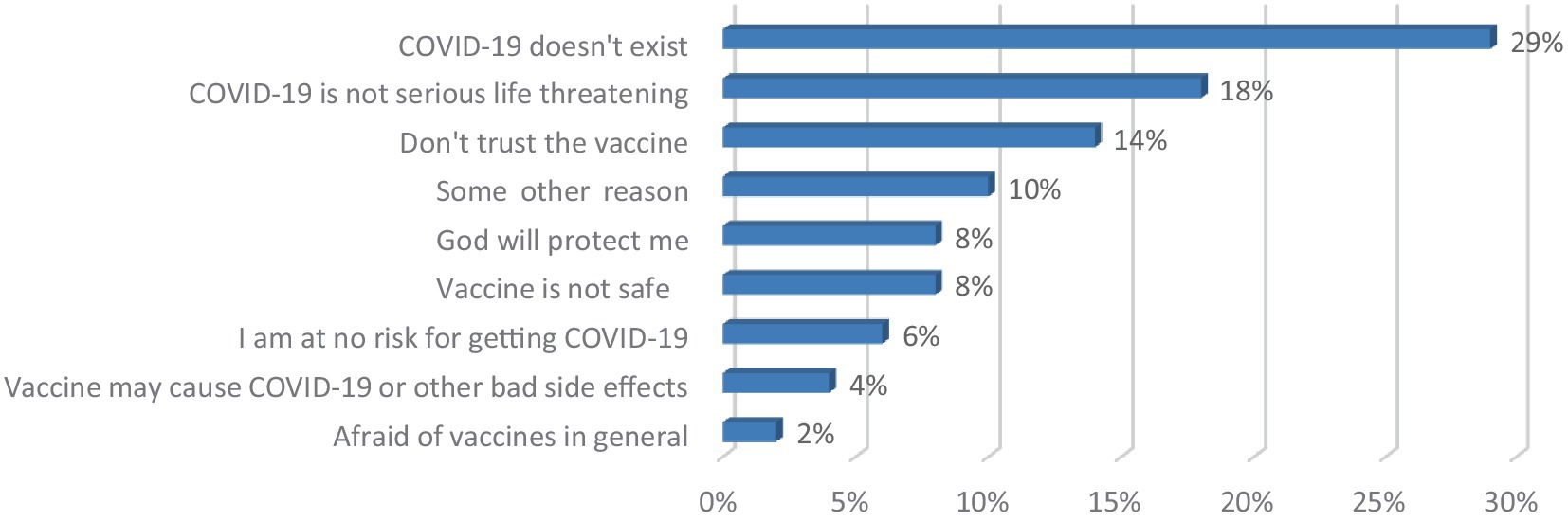

Figure 3. Main reason for vaccine hesitancy in Nigeria, 30 June 2022. Source: Afrobarometer’s News Release, 7 June 2022.

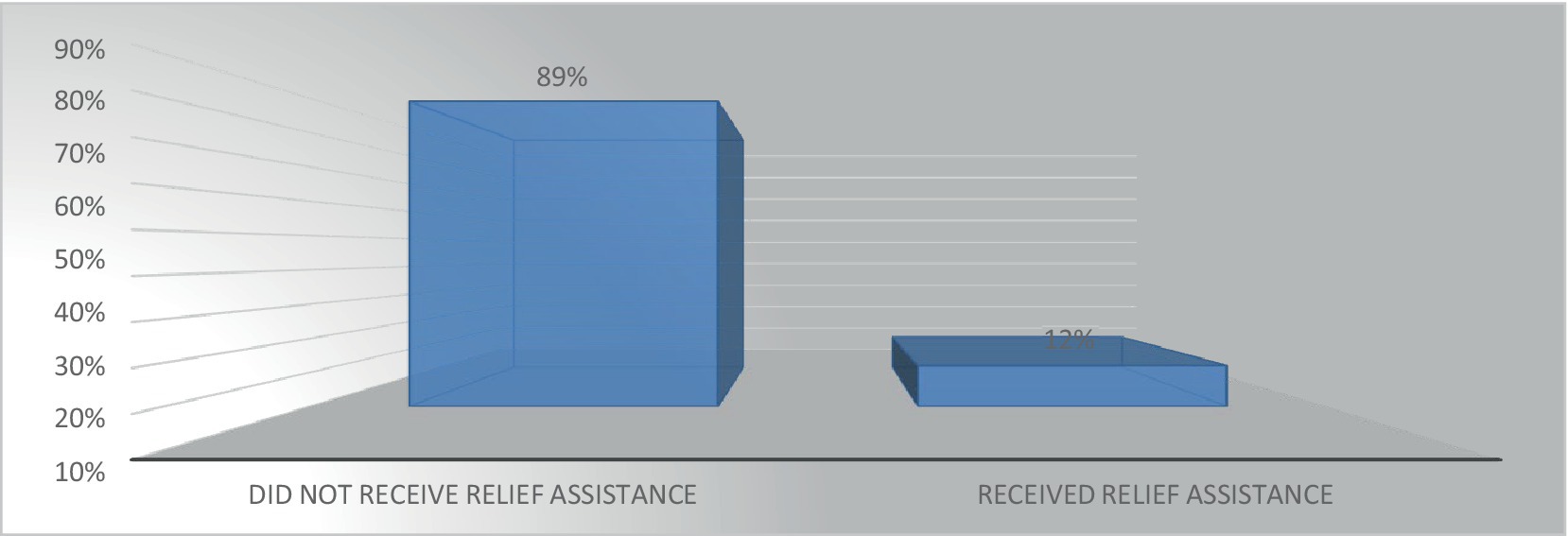

Figure 4. Access to COVID-19 relief assistance. Source: Afrobarometer (2022).

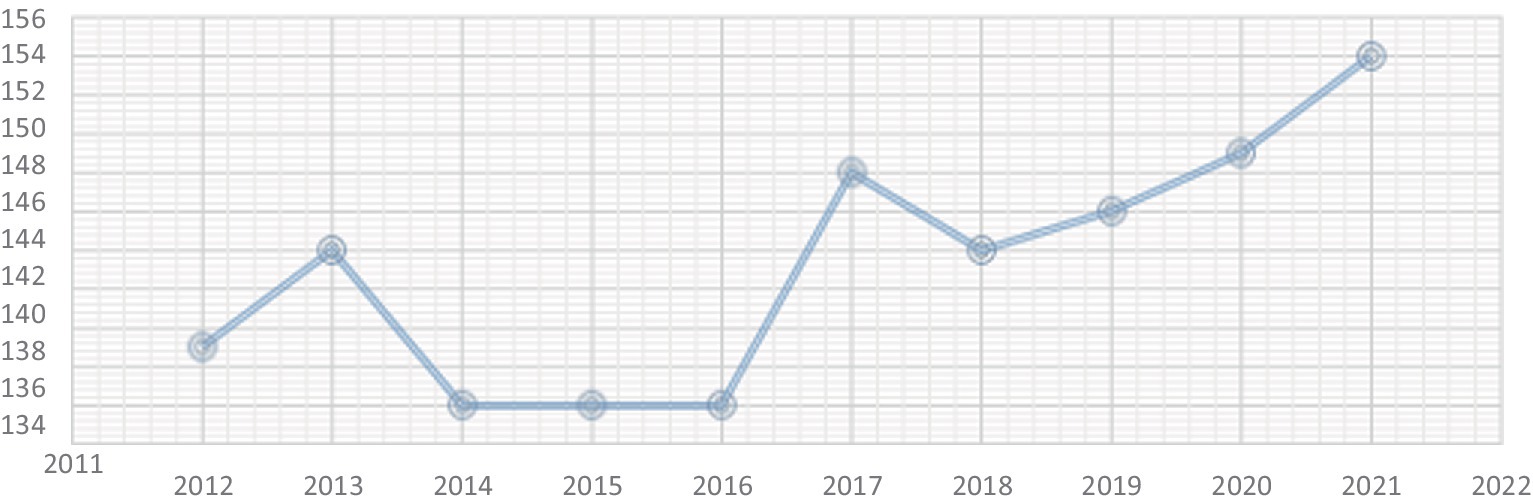

Authoritative sources such as the International Budget Partnership (IBP), Afrobarometer, and Transparency International (TI) also corroborated the incidences as discussed above. The trend in the cross-country open survey of the International Budget Partnership (IBP) from 2008 to 2021 dataset indicated a large deficit between Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, and Nigeria. The better result for Nigeria was in 2021, where it scored 45 against 56, 50, and 86 in Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa, respectively. The same experience was witnessed in Transparency International’s (TI) corruption perception index (CPI). In comparison with other African countries, the CPI results indicate a devastating level of public sector corruption in Nigeria. Accordingly, it covers bribery, diversion of public funds, officials using their public office for private gain without facing consequences, the ability of the government to contain corruption, excessive red tape in the public sector, nepotistic appointments in the civil service, the extent of implementing laws ensuring that public officials disclose their finances and potential conflicts of interest, legal protection for people who report cases of bribery and corruption, state capture by narrow vested interests, and access to information on public affairs/government activities. Specifically, Nigeria is the 154 least corrupt nation out of 180 countries, according to the 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index reported by Transparency International (2022). Nigeria’s position has worsened since 2016 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Nigeria’s position in the global ranking of corrupt countries, 2012–2021. Source: Transparency International (website: https://www.transparency.org/), 2022.

Despite mass orientation, precautions, and protocols, many Nigerians underestimated the danger of the pandemic. Respondents who participated in the KII and FGD expressed disappointments in the way and manner in which the government has been treating the citizens in terms of public goods. According to statements directly quoted from the FCT-Abuja FGD (FGD 2). A participant who is a bus driver and partook in the attacks and looting of government palliative stores in Gwagwalada stated:

‘Since I was born and through the various experience I have while growing up, I have not benefitted anything from the Nigeria government. My parent struggled to train me and my 4 siblings to school, and none of us have a job.’ (FGD 2).

Another participant, who is also a bus driver buttressed, quoted as:

‘I am always angry with anything that has to do with government and I have vowed not to be part of the government in any circumstances. This is because my parent died while on hard work without enjoying anything in life. And see me now, I work like hell to provide everything for myself and family. We know how citizens of other countries such as United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Qatar, South Africa, etc. are enjoying because they have good government. For instance, I paid for my children to go to school, pay electricity bill without enjoying it, pay for vigilante and join others to move around midnight to secure our lives and that of our family. Tell me, what is the purpose and usefulness of government you are talking about?’ (FGD 2).

This loss of hope in government and its activities as exhibited in the Federal Capital Territory (FGD 2) was also a concern deduced with other participants in Lagos (FGD 1), Plateau (FGD 3), Kaduna (FGD 4), and Cross Rivers (FGD 5). Citizens expressed frustrations because of a lack of trust in people representing them in government, nor having means to influence the decisions of the government that is pro-people in nature. Participants explained: “you see people at the National and various States Assemblies are not representing us, they only represent their interests and pockets” (FGD 3 and FGD 1). “The definition of democracy in Nigeria is the government of the few, for the few and by the few” (FGD 1). In Cross Rivers, one focused group participant asked the interviewer, thus: “why are even asking us these kind of questions, are you not a Nigerian or you are not living in Nigeria? Cannot you see that in Nigeria, the government have destroyed our education system, health infrastructure is disarray, there is high rate of insecurity, employment rate is increasing, and there is hunger in the land. Cannot you see it yourself and stop asking us these questions” (P2 in FGD 5). This anger and disappointment from a range of participants highlights that there is an existence of entrenched public trust in Nigeria.

Apart from the lamentation revolving around lack of public goods and weak institutions, another factor respondents talked about was the issue of corruption. Corruption, misappropriation of funds, and mismanagement of government resources by the political class and government officials were attributed to the reason they (participants) considered the pandemic as one of the ways government officials were designed to milk public resources (FGD 1, FGD 2, and FGD 5). Citing various cases of disasters and crises, P9 lamented that there were issues in the past where government officials and the political class used to feed their pocket. P10 also stated that government actions are usually likened with corruption and corrupt practices because of the experience. “We cannot rule out the fact that the responses from the government are layered with corruption” (P10).

As a result of these experiences, interviewees gradually came to see the betrayal of public trust as the norm. Naturally, in Nigeria, people smell and consider government actions as acts of selfishness, deceit, dishonesty, and lying (P6, P7, P8, P9, and P10). These are the major reasons public support is difficult to mobilise for government decisions and policies (P9). Thus, the experience during the COVID-19 pandemic also followed the same sequence.

Between 27 February 2020, when the country reported its first COVID-19 case (Federal Ministry of Health 2020; Federal Ministry of Health – Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, 2021), and now, Nigeria has suffered the outbreak and three distinct waves of infection (June 2020, January 2021, and August 2021) that have resulted in thousands of deaths, economic loss, and the loss of citizens’ primary source of income, depression, and a rise in domestic violence (Premium Times, 2022).

On how public trust in the government affected the efforts put in place to manage and curtail the spread of the pandemic, participants from the multi-sectoral COVID-19 Preparedness Group stated that poverty, poor health facilities, inadequate testing centre, shortage of health workers, and a low level of informed populace constituted major challenges that confronted the management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria (P1, P2, P3, P4, and P5). Beyond these, it was also found that distrust in the government and its activities was a major problem in COVID-19 management. The strong indication of this is that the NCDC protocols such as social distancing, wearing of facemasks, constant cleaning of hands with soap and sanitisers, no public gathering, etc. were said to have received a low level of compliance (P1 and P2). The Presidential Task Force (PTF) stated that close monitoring of activities shows that the level of compliance is unsatisfactory (P2). In fact, at the peak of the pandemic that necessitated total lockdown measures, many Nigerians were non-chalantly moving on with their daily business. A senior member of the PTF stated that “it is terrifying to understand the danger and gravity of threat while the subjects are seeing it as a deceit” (P20). Some of the participants during the FGD in Lagos, FCT, and Kaduna concluded that:

‘Do you belief in that thing called COVID? Do not disturb yourself at all. Our government officials are only want to use it to siphon public pulse’ (FGD 1, FGD 2, and FGD 4).

In addition, media sources reported that Nigerians were consistently playing five-aside football matches, going to clubhouses (The Guardian Newspaper, 2021a, January 9), worshipping in congregation (The Guardian Newspaper, 2021c, December 25), and doing business in the markets and elsewhere. In fact, some hundreds burnt down police stations over suspension of congregational prayers (Punch Newspaper, 2020b, March 29; Vanguard News, 2020, March 29) and others converged to stone the Sultan of Sokoto and Amir Muslims (Nigeria) for the cancellation of the year-2020 Eid congregation prayer because of the COVID.

Hesitancy to directives such as taking a vaccine, masking, washing hands and using sanitiser, reducing socialising, lockdown flaunting, praying in congregation, clubbing, etc. Nigerians actually partook in these activities while the pandemic was at the peak. Most of the key players (P2, P1, P3, P5, P8, and P10) expressed dissatisfaction with the attitude of most Nigerians towards government responses, saying those responses were in the best interest of the populace. To P2, the government cannot fold its hands while allowing its citizens to die of avoidable diseases like the pandemic. The pandemic ended up taking 6,329,275 lives (as of 29 June 2022), with cumulative 542,188,789 cases (as of 29 June 2022) throughout the world (WHO COVID-19 Dashboard, 2022, June 29). In it, Nigeria had confirmed cases of 256,958 and 3,144 deaths (WHO COVID-19 Dashboard, 2022, June 29). Despite this serious posture and data, up until now, many Nigerians, including the educated ones, are still running away from vaccination.

Vaccine hesitancy is disturbing, especially amongst government staff and other formal and informal sectors. The number of people taking vaccines in the ratio of population to vaccines available has shown a drastic fall, despite the mass orientation and public awareness launched by the government and its agencies at various levels. On 2 March 2021, Nigeria took delivery of 3.9 million doses of the much-anticipated Oxford Astrazeneca vaccine. Similarly, it also received 177,600 Johnson & Johnson vaccines on 12 August 2021. Other doses in millions continue to flow in the country. At a point when the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported that Nigeria had received a total of 50.6 million doses of vaccines (WHO COVID-19 Dashboard, 2022), only 21 million people had been fully vaccinated (see Figure 2).

Vaccine hesitancy was also affected by a lack of trust in the system and its actors. Citizens’ narratives across regions show that they believe that the system, including government institutions, political actors, and government officials, is untrustworthy, and therefore, any acceptance of what comes from them, especially on something sensitive as vaccine, will expose citizens to risk (FGD 1, FGD 2, FGD 3, FGD 4, and FGD 5). Understanding deeper narratives of untrustworthiness of the system and the perception that it will expose the citizens to a high risk, three evaluative components emerged:

a. political trust;

b. mythology on the vaccine;

c. capacity of the health facilities.

P2 stated that the government faced a problem of trust in the pandemic at the beginning of the campaign. According to him, citizens do not believe that such a thing exists, suggesting that the government elites are just using such events to fill their pockets. Another instance that has to do with political trust, in the view of P9, is that people are already hungry and angry; however, the directives during the pandemic are too restrictive, and there is no provision of relief, called palliatives. Unfortunately, and unlike the causalities in other countries of the world, the Nigerian situation remains mild and not intense. The whole thing was affected by mistrust caused by government irresponsibility and non-performance, amplified by the level of corruption and mismanagement of public resources.

The second component has to do with myths and controversies surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, which were complicated by the hesitancy of vaccine. There were numerous identified self-created myths spreading quickly on social media, which was validated during the survey of this study to have been scaring the citizens away from the vaccine centres. The following are the major responses to why the respondents are not taking vaccines in Nigeria:

a. there is no COVID-19 in Nigeria;

b. vaccine is a bad chemical that’s meant to reduce potency and childbearing;

c. COVID is malaria packaged for us as a pandemic; local herbs are enough to manage it;

d. COVID-19 vaccine makes the recipient’s body magnetic;

e. vaccine is only necessary if I want to travel out of the country;

f. even if the government is paying people for taking vaccine, I will not take it;

g. we are not sure if the vaccine is properly managed and safe;

h. I do not want Nigeria to use me for an experiment.

In response to citizens’ hesitancy, the government threatened and applied a stringent rule to enforce compliance. Some of these include the federal and some state governments ‘no vaccination, no entry into work places’ policy (Channels Television, 2021, 15 September; Premium Times, 2021, October 13; Nigerian Tribune Report, 2021, 1 December). Unfortunately, the Federal High Court in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, with suit marked FHC/PH/FHR/266/2021, granted an order restraining Edo Governor and the state government from restricting unvaccinated persons from attending mass gathering as of September 2021 (Muanya et al., 2021, September 1). This court order ended the sanction(s) proposed by the government to enforce vaccination. Thus, the hesitancy grows wider alongside the myths. There are still hundreds of thousands of workers in both formal and informal industries who are neither taking nor refusing vaccine (Afrobarometer’s News Release, 7 June 2022). As a result, millions of vaccines have expired and been destroyed (Adebowale, 2021, December 22).

Relatedly, one of the leading empirical platforms in Africa, Afrobarometer, stated in its recent publication (7 June 2022) that “one-third of Nigerian adults say they are unlikely to try to get vaccinated against COVID-19, including many who say they do not believe the virus exists, thought “the vaccine pose a serious threat.” See the hierarchy of the main reasons for vaccine hesitancy as published by Afrobarometer (2022) in Figure 3.

Apparently awed by the endless consequences of public distrust of the government and the officials, the great efforts and resources devoted during the management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria could have been pronounced and effective.

The third component is the capacity of the related institutions and officials to manage and retain the quality of the vaccine. This was expressed by the participants (FGD 1, FGD 2, FGD 3, FGD 4, and FGD 5), and some of the key players in the management of COVID-19 (P2, P7, and P8). Citizens are terrified because of the technical evaluations of the system in the areas of “management of things” (P9, P10, FGD 1, and FGD 2), “getting things done rightly and correctly” (P1, P2, and FGD 1), “state of health facilities and infrastructure issues” (P1, P2, P3, FGD 1, FGD 2, and FGD4), “general infrastructure and epileptic power supply” (P6, P7, and P8), and lastly, “state of the country and the bad economic outcomes” (FGD 1, FGD 2, and FGD 3). These assessment outcomes are very key and in line with the literature that highlights the importance of economic and institutional performance in ensuring public trust (see Mikitin, 1995; Dalton, 2004; Marien and Hooghe, 2010; OECD, 2013, 2022).

To begin with, what did the government do or fail to do during the COVID-19 pandemic that either increased, sustained, or reduced public trust? Government responses to the shocking world pandemic since 2020 fall into four main domains (P2):

a. containment;

b. public health measures,

c. social and economic policies, and

d. fund raising.

In terms of quick strategy for containment and public health measures, the government was highly commended for its responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (P6, P7, P8, P9, and P10), especially in its quick setting up of clinics and testing centres (in Lagos, FCT, and other flag points). However, government handling and implementation of social and economic policies, including funds and hoarded social stimulus called palliatives, raised questions about the accountability of the government both at national and sub-national levels (P7, P8, P9, and P10). This was said to have led to aggressive citizens’ reactions, such as the recorded spontaneous looting of warehouses where COVID-19 relief materials were kept in some states (Aluko, 2020).

The tracing of contacts, treatments, and investment in the various means adopted for public awareness, including other stringent non-pharmaceutical interventions such as lockdown, which include stay-at-home orders, cessation of non-essential movements and activities, closure of schools and workplaces, bans on religious and social gatherings, cancellation of public events, curfews, restrictions on movement, and cessation of interstate and international travel, were acknowledged to go a long way in containing the spread of the pandemic. However, major activities surrounding the shrouded nature of the activities, especially the lack of transparency and accountability of the funding and social stimulus interventions (such as the palliatives and the cash transfer), have worsened the deteriorating level of distrust in the government (FGD 1, FGD 2, FGD 3, FGD 4, and FGD 5).

People were sceptical about the daily numbers given out by the government, which do not corroborate with reality. Citizens thought that either ‘no such thing as COVID’ or ‘it is not serious life threatening’ (FGD 1, FGD 2, FGD 3, and FGD 5), or ‘government is just increasing the numbers to increase their entitlement with development agencies and governments’ (FGD 1, SMDM 1). Despite the fact that there were verifiable centres, victims’ accounts, and daily casualties recorded, several wondered why they could not see someone close or someone who knows someone who has been contracted with COVID (Survey Report, 2022). Evidence shows that there is high conviction amongst Nigerians that COVID-19 is a ruse, either meant to siphon public pulse or big man disease and weapon of the developed countries to deal with themselves. Up until now, the government has been unable to demystify all these misconceptions.

Unfortunately, the government failed to account properly for the management of donations and other funds from appropriations raised to finance the COVID-19 pandemic. This ignited several allegations of mismanagement of COVID-19 funds from Nigerians, especially the coalition of Civil Society Organisations (P6, P7, and P8). There were more than N99 billion and millions of dollars in recorded donations from individuals, domestic, and international organisations (Okeowo et al., 2021). CSOs alleged massive looting and spending shrouded in secrecy (P6 and P7). An empirical report also suggests citizen’s perceived massive corruption in combating and responding to the pandemic (Afrobarometer, 2022). This was a major concern of the respondents during the interviews (FGD 1, FGD 2, FGD 3, FGD 4, and FGD 5).

In addition, most countries in the world launched several welfare schemes to help their citizens to survive the effects of the pandemic. For instance, Kazakhstan provided social and economic supports to its citizens and industry (Jones and King, 2021); Singapore also announced and implemented four budgets for COVID-19 support measures that came from past reserves to support businesses and ensure job retention (Peralta-Santos et al., 2021); the Afghanistan government provided free bread to the poor in Kabul with more than 1.5 million beneficiaries; Canada has greater support for Indigenous communities and has spent more than $290 billion in direct aid to households and firms, including wage subsidies, payments to workers without sick leave, parental support, etc. The United States has social scheme for older Americans and others at high risk, etc. (IMF COVID-19 Policy Tracker, 2021, July 2). In African countries, records of social protection and economic stimulus were imminent, such as in Senegal, South Africa, and Kenya. The Senegal government provided food aid for one million households (FCFA 64 billion), and utility payments (for water and electricity) for poorer customers were suspended for a 2-month period (FCFA 15.9 billion); South Africa assisted companies and workers facing distress through the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF); workers with an income below a certain threshold received a small tax subsidy for 4 months; and the most vulnerable families received temporarily higher social grant amounts until the end of October 2020. A new temporary COVID-19 grant was created to cover unemployed workers, and funds were made available to assist SMEs under stress, especially small-scale farmers operating in the poultry, livestock, and vegetable sectors. The Kenyan government initiated economic stimulus package that includes a new youth employment scheme, the provision of credit guarantees, fast-tracking payment of VAT refunds and other government obligations, increased funding for cash transfers, and several other initiatives (IMF COVID-19 Policy Tracker, 2021, July 2).

In Nigeria, there were social-economic policies and programmes such as cash transfer ($52 to the poor registered in the National Social Register), food assistance by the Federal Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management, economic stimulus from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), and the palliative. Unfortunately, evidence suggests that people neither heard of the schemes nor benefitted from them (FGD 1, FGD 2, FGD 3, FGD 4, and FGD 5). Several other studies found that even very poor people had not received anything from the government during the lockdown (Eniola, 2020, April 29; Afrobarometer, 2022), while CSOs alleged massive corruption (Sahara Reporters, New York, 2022, March 31). However, the representatives of the leading agencies in the management of the pandemic, especially the Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management, and Social Development (P3), stated that each state government was responsible and had been saddled for organising the distribution of items and cash transfers in its localities. Only a small fraction of the population received the relief materials and cash transfer. Aside from government officials, most Nigerians who partook in this study claimed to be only aware of the schemes and materials in the media (see Figure 4). It was noted that the federal and state governments involved handed the palliatives over for political settlement and benefits, which resulted in the stockpiling of foods and other relief materials. The transparency and accountability of various programmes were highly compromised.

Essentially, the last straw that broke the camel’s back was the deep-seated disappointment and anger exhibited by the deeply hungry citizens, especially youths, when they found a number of hidden palliative warehouses across the states of the federation, including FCT (SMDM 1, SMDM 2, and SMDM 3). On 8 October 2020, the youth of the country began a protest with the hashtag #ENDSARS# aimed at curbing police brutality. Amid the protests was the strangest occurrence that saw the discovery of a large warehouse in Mazamaza, Lagos, where COVID-19 palliatives were stored (SMDM 1). Looting of palliatives operation began in Lagos, Nigeria, on Thursday, 22 October 2020. With justification that the government officials must have hidden it for personal gain, the angry and hungry masses descended on the supplies and emptied the warehouse within hours (SMDM 1). This opened the eyes of other protesting youths in other states such as Oyo, Edo, Kwara, Plateau, Enugu, Anambra, Osun, Taraba, Kaduna, Adamawa, and Delta. Abia, Cross River, FCT, and others to locate and loot COVID-19 palliative warehouses (The Guardian Newspaper, 2020, October 30). Unfortunately, the lootings were fuelled further because of spiralling food prices, high unemployment rate, and anti-police brutality protests that turned violent in October, completely eroding trust in the government and its officials. After the looting of the noticed government warehouses, the hoodlums hijacked the event and descended on the politicians across the countries where it’s on record their houses and other investments were looted and burnt (Punch Newspaper, 2020a, October 26; SMDM 1, SMDM 2, SMDM 3). Private business, individual houses, and investments were looted in Oyo, Lagos, Osun, Kwara, Adamawa, Plateau, and a few others (SMDM 1). Oyo Central Senatorial District accounted for constituency projects and looted materials as over 350 motorcycles, 400 deep freezers, 350 generators, grinding machines, sewing machines, hairdressing and barbing salon materials, vulcanising machines, and many more (Premium Times, 2020, October 25).

Based on the discussion so far, the study established that the public trust issue is orchestrated by the government’s inability to provide public goods such as security, employment opportunities, education, health services, level of corruption, poor economic management, lack of transparency and accountability in the affairs of the government, etc., which has greatly affected the efforts and investments to manage the pandemic. Unfortunately, the level of current public trust was further fractured by the way the Nigerian government manages the COVID-19 pandemic, especially the lack of transparency and accountability in donations and allocations, cash transfer, and the distribution of relief materials, also known as palliatives, which later escalated and resulted in anger, attacks, and spontaneous looting of government-owned stores, politician houses, and private individual investments. In order to build public trust and enhance public support for government interventions in Nigeria, the following are policy options and recommendations:

a. First, major institutions such as the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), the police, military, and intelligence agencies; the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC); the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC); the Auditor-General of the Federation; the Attorney-General of the Federation, etc. are protected from political interference. To guard democracy and promote public trust in critical institutions, a constitutional amendment is proposed for a special committee including the representatives of parliament, judiciary, executive, civil society groups, youth groups, intelligence agencies, etc. to see to the appointment of leadership and day-to-day operation of the agencies above. Candidates to be considered for the leadership position should neither have been members of nor have an interest in membership in a political party.

b. Second, there is a need to promote citizens’ engagement at all levels and in government decisions. Engaged citizens can play a critical role in making public institutions more transparent, accountable, and effective and contributing innovative solutions to public issues. For instance, including CSOs in the distribution oversight of the palliatives and the management of the cash transfer scheme would likely have reduced opportunities for corruption.

c. Third, criminalising excessive secrecy amongst government officials could advance accountability. In this context, implementing the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act is important at this critical period. All officials must understand the importance of being transparent and accountable to the public.

d. Fourth, the government needs to be proactive in attending to citizens’ concerns and welfare. Services such as education, health, employment creation, institutionalised welfare safety net for the unemployed and senior citizens, etc. are key to redeeming the image of the government. The strikes in health, education, and other essential institutions are damaging when there are information of corruption involving hundreds of billions of naira amongst the officials and institutions of the government. The welfare of the staff and facilities of these institutions should be prioritised by the government. This will go a long way in promoting the public trust. Therefore, the government should provide the citizens with proper and adequate social security nets that will help cushion the effects of poverty and unemployment and increase people’s faith in the government.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The study involving human participants was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies. The participants provided their written informed consent for participation in the study.

KA: Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The American University, Washington DC, United States provided funding for publication.

The author would like to thank the following organisations and individuals who have provided platforms for intellectual engagements and feedback on this work: American Political Science Association (APSA), Africa Research Development Group (ARDG), African Politics Conference Group (APCG), Prof. Carl Levan, Prof, Chris Isike, Prof. Yahaya Baba, Prof. Saka Luqman, Prof. Fatai Aremu, Dr. Adewale Aderemi, Dr. Leo Igbanoi, Dr. Ganiyu Ejalonibu as well as other colleagues at the National Institute for Legislative and Democratic Studies (NILDS), Nigeria.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^Key Informant Interview (KII) Code: P1–P10 as used in the research design are codes used to differentiate between various participants during the KII. P1 is Participant 1, P2—Participant 2, P3—Participant 3, P4—Participant 4, P5—Participant 5, P6—Participant 6, P7—Participant 7, P8—Participant 8, P9—Participant 9, and P10—Participant 10.

2. ^Focused Group Discussion (FGD) Code: FGD 1–FGD 5 as used are codes given to the focused group discussions in Lagos—FGD 1, Federal Capital Territory-Abuja—FGD 2, Plateau—FGD 3, Kaduna—FGD 4, and Cross Rivers—FGD 5.

3. ^Social Media Data Mining (SMDM) Codes: SMDM 1–SMDM 3 as used are codes given to the social media platforms as follows: Facebook—SMDM 1, Instagram—SMDM 2, and Twitter—SMDM 3.

4. ^Using national dailies, it was noted that Nigerian public universities had been under lock since the beginning of the fourth republic, as follows: 1999 (5 months), 2001 (3 months), 2002 (2 weeks), 2003 (6 months), 2005 (2 weeks), 2006 (6 days), 2007 (3 months), 2008 (1 week), 2009 (4 months), 2010 (5 months), 2011 (59 days), 2013 (5 months), 2013 (1 month), 2018 (3 months), 2020 (9 months), and 2022 (8 months).

Adebowale, N. (2021). COVID-19: Nigerian govt. destroys over 1 million doses of vaccines. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/502061-covid-19-nigerian-govt-destroys-over-1-million-doses-of-vaccines.html.

Adeyemo, O. O., Akindele, S. T., Aluko, O. A., and Agesin, B. (2012). Institutionalizing the culture of accountability in local government Administration in Nigeria. Pol. Sci. Int. Relat. 6, 81–91. doi: 10.5897/AJPSIR11.127

Afrobarometer (2022). ‘COVID-19 doesn’t exist’ tops list of reasons among vaccine hesitant Nigerians, Afrobarometer survey shows. Afrobarometer News Release. Available at: https://www.afrobarometer.org/articles/covid-19-doesnt-exist-tops-list-of-reasons-among-vaccine-hesitant-nigerians-afrobarometer-survey-shows/

Aluko, O. (2020). ‘Hoarded’ CoVID-19 palliatives put governors under the spotlight. Punch. Available at: https://punchng.com/hoarded-covid-19-palliatives-put-governors-under-the-spotlight/

Babbie, E., and Mouton, J. (2011). The practice of social research. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

Bertsou, E. (2019). Political distrust and its discontents: exploring the meaning, expression and significance of political distrust. Society 9:72. doi: 10.3390/soc9040072

Castelfranchi, C., and Falcone, R. (2011). Socio-cognitive theory of trust. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266039117_Socio-Cognitive_Theory_of_Trust

Centre for World University Rankings (2022). Global 2000 list by the Centre for World University Ranking. Available at: https://cwur.org/2022-23.php.

Channels Television (2021). COVID-19: Edo Govt wokers without vaccination cards barred from office, September 15. Available at: https://www.channelstv.com/2021/09/15/covid-19-edo-workers-without-vaccination-cards-barred-from-govt-offices/

Citrin, J., and Stoker, L. (2018). Political trust in a cynical age. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 21, 49–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050316-092550

Dalton, R. J. (2004). Democratic challenges, democratic choices: the erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eniola, T. (2020). “We hope our cries will attract attention”. Afr. Aff. Available at: https://africanarguments.org/2020/04/vulnerable-covid-19-we-hope-our-cries-will-attract-attention/

Federal Ministry of Health (2020). Health Minister: First case of COVID-19 confirmed in Nigeria. Available at: https://www.health.gov.ng/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=613:health-minister-first-case-of-covid-19-confirmed-in-nigeria#:~:text=The%20Federal%20Ministry%20of%20Health,in%20China%20in%20January%20.

Federal Ministry of Health – Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (2021). One Year After: Nigeria’s COVID-19 Public Health Response (February 2020 – January 2021). Available at: https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/media/files/COVIDResponseMarch1.pdf

Gray, D. E. (2014). Doing Research in the Real World, 3rd edition. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239938424_Doing_Research_in_the_Real_World_3rd_edition

Gulleng, D., and Musa, S. Y. (2020). Governance, police legitimacy and citizen’s compliance with Covid-19 guidelines in plateau state, Nigeria. Acta Criminol. 33, 90–107. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350042776_Governance_police_legitimacy_and_citizen’s_compliance_with_Covid-19_guidelines_in_Plateau_State_Nigeria

Hamalai, L., Aremu, F. A., and Umar, A. (2015). Industrial strikes in the health sector: Incidence, causes and solutions. National Institute for Legislative Studies Policy Paper Series.

Hetherington, M., and Rudolph, T. (2015). Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust and the Governing Crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Holum, M. (2022). Citizen participation: Linking government efforts, actual participation, and trust in local politicians. Int. J. Public Adm. 46, 915–925. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2022.2048667

Ibekwe, N. (2014). We can’t return Nigeria’s seized $15million arms money without due process – South Africa. Premium Times. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/169486-we-cant-return-nigerias-seized-15million-arms-money-without-due-process-south-africa.html?tztc=1

ICIR (2021). How Nigeria lost nearly 300 working days to hospitals strikes in eight years, December 17. Available at: https://www.icirnigeria.org/how-nigeria-lost-nearly-300-working-days-to-hospital-strikes-in-eight-years/.

IMF COVID-19 Policy Tracker (2021). Policy tracker by country. International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19.

Jones, P., and King, E. J. (2021). COVID-19 response in Central Asia: a cautionary tale. In S. L. Greer, E. J. King, E. M. Fonsecada, and A. Peralta-Santos (eds.) Coronavirus politics: The comparative politics and policy of COVID-19. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press

Jung, Y., and Sung, S. Y. (2012). The Public’s declining Trust in Government in Korea. Meiji J. Polit. Sci. Econ. 1:2012. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/51180866.pdf

Kazeem, Y. (2017). Only one in four Nigerians applying to university will get a spot. Quartz. Available at: https://qz.com/africa/915618/only-one-in-four-nigerians-applying-to-university-will-get-a-spot

Kemence, K. O. (2013). Understanding the root causes of military coups and governmental instability in West Africa. US Army Command and General Staff College. Available at: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA599175.pdf

Kumagai, S., and Iorio, F. (2020). Building Trust in Government through citizen engagement. World Bank Group. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33346/Building-Trust-in-Government-through-Citizen-Engagement.pdf

Maishanu, A. A. (2022). Terrorism: Buy guns, defend yourselves, Zamfara govt tells residents. Premium Times. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/539237-terrorism-buy-guns-defend-yourselves-zamfara-govt-tells-residents.html.

Marien, S., and Hooghe, M. (2010). Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance. Eur J Polit Res 50, 267–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01930.x

McKnight, D. H., and Chervany, N. L. (1996). “The meanings of trust”. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/26734531/The_Meanings_of_Trust

Mikitin, K. (1995). Issues and options in the design of GEF supported trust funds for biodiversity conservation. Environment Sustainable Department, World Bank.

Muanya, C., Onyedika-Ugoeze, N., Egbejule, M., and Nwaoku, O. (2021). FG set to sanction Nigerians refusing COVID-19 vaccination. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/fg-set-to-sanction-nigerians-refusing-covid-19-vaccination/.

Mutiullah, A. O., Solomon, B. A., and Fidelis, M. A. (2016). Rethinking comparative politics in Africa. J.J. Professional Publishers. Available at: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/11948490.

Nigerian Tribune Report (2021). FG begins enforcement of compulsory COVID-19 vaccination, December 1. Available at: https://tribuneonlineng.com/fg-begins-enforcement-of-compulsory-covid-19-vaccination/.

Nwabughiogu, L. (2020). Abacha loot: how much did the late head of state steal? Vanguard News. Available at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/03/abacha-loot-how-much-did-the-late-head-of-state-steal/

OECD (2013). Trust in Government. In Government at a glance. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/gov_glance-2013-6-en.pdf?expires=1658673084&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=DB39E82B2E9048A137531E3977AEFFCC

OECD Working Papers on Public Governance (2022). Survey design and technical documentation supporting the 2021 OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Government Institutions. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/survey-design-and-technical-documentation-supporting-the-2021-oecd-survey-on-drivers-of-trust-in-government-institutions_6f6093c5-en

Okeowo, G., Kwaga, V., Bolarinwa, I., Onigbinde, O., and Ilevbaoje, U. (2021). COVID-19 fund: Introductory report on fiscal support, Palliative Analysis and Institutional Response. BudgIT. Available at: https://yourbudgit.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Pattern-of-Palliative-Distribution-Web.pdf.

Omitogun, O., and Longe, A. E. (2017). Unemployment and economic growth in Nigeria in the 21st century: VAR approach. Economica 13. Available at: https://journals.univ-danubius.ro/index.php/oeconomica/article/view/4064/4423

Onah, E. I. (2014). Nigeria: a country profile. J. Int. Stud. 10, 151–162. Available at: https://e-journal.uum.edu.my/index.php/jis/article/view/7954

Osaghae, E. E. (1998). Crippled giant: Nigeria since independence. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Peralta-Santos, A., Massard da Fonseca, E., King, E. J., and Greer, S. L. (2021). Singapore’s response to COVID-19: an explosion of cases despite being a “gold standard”. In S. L. Greer, E. J. King, E. M. Fonsecada, and A. Peralta-Santos (eds.) Coronavirus politics: The comparative politics and policy of COVID-19. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press

Premium Times (2016). N24billion Police Pension Scam: No Vouchers for N9.7 billion withdrawals – Witness, February 10.

Premium Times (2020). Looting Spree: Why I stored constituency Project items in my house – Senator, October 25. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/422977-looting-spree-why-i-stored-constituency-project-items-in-my-house-senator.html

Premium Times (2021). COVID-19: Nigerian govt makes vaccination mandatory for civil servants, October 13. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/489749-just-in-covid-19-nigerian-govt-makes-vaccination-mandatory-for-civil-servants.html

Premium Times (2022). EFCC set to arraign former accountant-general, Ahmed Idris, over N109bn fraud charges, July 21. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/544180-efcc-set-to-arraign-former-accountant-general-ahmed-idris-over-n109bn-fraud-charges.html

Punch Newspaper (2020a). Looting of Abuja warehouses continues in Gwagwalada, Idu, October 26. Available at: https://punchng.com/looting-of-abuja-warehouses-continue-in-gwagwalada-idu/

Punch Newspaper (2020b). Coronavirus: One killed as Katsina protesters burn police station over Jumah ban, March 29. Available at: https://punchng.com/coronavirus-one-killed-as-katsina-protesters-burn-police-station-over-jumat-ban/

Sahara Reporters, New York (2022). Civil Society Organisations Alleged Massive Looting of Nigeria COVID-19 Funds, Spending Shrouded in Secrecy, March 31. Available at: https://saharareporters.com/2022/03/31/civil-society-organisations-allege-massive-looting-nigeria-covid-19-funds-spending

Saka, L. (2020). Virulent virus and public mistrust: the Nigerian state and the management of COVID-19 pandemic. 360 vibes. Available at: https://360vibez.com.ng/virulent-virus-and-public-mistrust-the-nigerian-state-and-the-management-of-covid-19-pandemic-by-dr-luqman-saka/.

Shodunke, A. O. (2022). Enforcement of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown orders in Nigeria: evidence of public (non) compliance and police illegalities. National Library of Medicine. 77:103082. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103082

Survey Report (2022). The Report of the Fieldwork for Public Trust and COVID-19 Management in Nigeria Project. NILDS: Nigeria.

Tanko, A. (2021). Nigeria’s security crises – five different threats. BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-57860993

Tanny, T. F., and Al-Hosseinie, C. A. (2019). Trust in Government: factors affecting public trust and distrust. Jahangirnagar J. Admin. Stud. Department of public Administration, 12 (49–63). Available at: file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/Article-9TrustinGovernment.pdf

The Guardian Newspaper (2020). COVID-19 Palliative and its controversies: Interrogating the looting spree dimension, October 30. Available at: https://guardian.ng/saturday-magazine/covid-19-palliative-and-its-controversies-interrogating-the-looting-spree-dimension/.

The Guardian Newspaper (2021a). COVID-19: Why Nigerians fear another lockdown, yet defy safety protocols, January 9. Available at: https://guardian.ng/saturday-magazine/cover/covid-19-why-nigerians-fear-another-lockdown-yet-defy-safety-protocols/

The Guardian Newspaper (2021b). Nigeria improves on WHO health system ranking, says ACPN, November 26. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/nigeria-improves-on-who-health-system-ranking-says-acpn/.

The Guardian Newspaper (2021c). Christmas: Some worship centres flout COVID-19 protocols, December 25. Available at: https://guardian.ng/news/christmas-some-worship-centres-flout-covid-19-protocols/.

The Guardian Newspaper (2022). On medical brain drain, poor health system, April 24. Available at: https://guardian.ng/features/on-medical-brain-drain-poor-health-system/

This Day Newspaper (2021). Regional security outfits and tribal fireworks, June 28. Available at: https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2021/06/28/regional-security-outfits-and-tribal-fireworks/.

Tolu-Kolawole, D. (2022). ASUU suspends strike after eight months. Punch. Available at: https://punchng.com/breaking-asuu-suspends-strike-after-eight-months/

Transparency International (2018). Corruption Perception Index, 2018. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2018.

Transparency International (2019). Corruption Perception Index, 2019. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2019.

Transparency International (2020). Corruption Perception Index, 2020. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020.

Transparency International (2022). Corruption Perceptions Index, 2021. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2021

UNDP Oslo Governance Centre (2021). Trust in Public Institutions: A Conceptual Framework and Insights for Improved Governance Programming. Available at: https://www.undp.org/policy-centre/governance/publications/policy-brief-trust-public-institutions

Uzor, E. (2017). Reducing incentives for fiscal indiscipline at Nigeria’s subnational government level. Available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2017/01/16/reducing-incentives-for-fiscal-indiscipline-at-nigerias-subnational-government-level/ (Accessed May 26, 2020).

Vanguard News (2020). COVID: One dies, 90 arrested in Katsina for burning police station. Available at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/03/covid-19-one-dies-90-arrested-in-katsina-for-burning-police-station/

WHO COVID-19 Dashboard (2022). Number of COVID-19 Cases Reported to WHO, June 29. Available at: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases

Wierzbicki, A. (2010). Theory of trust and fairness. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251348752_Theory_of_Trust_and_Fairness

World Bank Data (2022). Population, 2022. Available at: https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/POP.pdf

Keywords: public policy, state, COVID-19 pandemic, public trust, management, transparency, accountability

Citation: Abayomi KQ (2024) Public trust and state management of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1334827. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1334827

Received: 07 November 2023; Accepted: 07 May 2024;

Published: 07 June 2024.

Edited by:

Carl LeVan, American University, United StatesReviewed by:

Zainab Ladan Mai-Bornu, University of Leicester, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Abayomi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kolapo Quadri Abayomi, a29sYXBvYWJheW9taUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.