- Institute of Intercultural and International Studies and Collaborative Research Centre 1342 “Global Dynamics of Social Policy, ” University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered turbulent times across the globe, reminding us of the highly multidimensional and interdependent nature of today's world. Next to diverging national attempts to constrain the spread of the virus, numerous international organizations worked intensely to minimize the impacts of the disease on a regional or/and global scale. Albeit not considered a conventional agency responsible for global infectious diseases, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has surprisingly been one of the most proactive IOs in the pandemic response. In this context, this article examines to what extent the OECD's COVID-19 pandemic response adheres to the role of a global crisis manager. By adapting the theoretical concepts of crisis leadership, we explore the extent of sense-making, decision-making, and learning capacities of the OECD during the pandemic, upon which we draw the organization's position-making. Based on expert interviews and document analysis, this article illustrates that the OECD's concerns regarding the pandemic's severe effects across socioeconomic sectors focused exclusively on its member states. This sense-making enabled prompt and multilayered top-down as well as bottom-up decision-making to provide member states with policy options as solutions to the new challenges. However, the OECD's engagement during the crisis was proactive only to the extent that several limitations allowed, such as resource inflexibility and internal dynamics between the Secretariat and member states. In conclusion, we argue that the OECD did not present itself to be a global crisis manager during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather, the IO's responses consolidated its position-making as a policy advisor for member states.

1 Introduction

In the last 20 years, the world has undergone multiple global infectious diseases, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002, Influenza-A-Virus H1N1 (swine flu), Ebola virus disease, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and Zika virus disease in 2015. Despite this intense experience with novel diseases, COVID-19 revealed that most countries were poorly prepared for a world-wide pandemic. The situation led to dreadful outbreaks of “medical nationalism,” in which countries hoarded medical supplies for domestic use, regardless of external costs (Youde, 2020). For instance, vaccine hoarding resulted in the extreme heterogeneity of the global vaccine distribution by the end of 2021, with some countries succeeding to build herd immunity while others reaching less than two percent vaccine coverage in adults (Moore et al., 2022). Confronting the challenges posed by the pandemic, the world apparently fragmented precipitously into state-defined entities.

On the level above individual state solutions, International Organizations (IOs) sought to inspire global cooperation to overcome the pandemic. However, IOs' approaches and reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic varied, ranging from sending out mere verbal responses lacking relevant action to initiating new policies and programs (Brown and Ladwig, 2020; Gallagher and Carlin, 2020; Debre and Dijkstra, 2021; Dimitrakopoulos and Lalis, 2022). Some studies show what determines the extent of engagement in the pandemic response. Van Hecke et al. (2021), for example, argue that IOs' institutional and political context, governance structure, and degree of autonomy shape their reactions. In the same vein, Debre and Dijkstra (2021) suggest that IOs' bureaucratic capacity is a significant factor that allows them to expand policy scope and instruments in reacting to the pandemic. Other scholars assess the outcomes of IOs' pandemic-related activities. For instance, Duggan et al. (2020) point out that the World Bank's lending to low-income countries was disproportionate to the economic impact of the crisis. More generally, Leisering (2021) argues that IOs' normative models for redressing social inequality exacerbated by the pandemic did not result in new ideas or institutionalized policies. As these studies highlight, some IOs engaged distinctly in coping with the crisis, resulting in a variety of responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite the OECD's unprecedented response to the COVID-19 pandemic both in width and depth, little attention has been paid to it. While the OECD as an organization has been dealing with health governance since its inception in 1961, only in the early 2000s has it been recognized as a more visible actor in the health governance field (Kaasch, 2021, p. 243). During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the OECD became an even more significant IO in the context of a global health crisis. The extent of the OECD's involvement in the fight against such a global disease was extraordinary. Since March 2020, the IO released nearly 250 policy briefs and ample data on its digital COVID-19 hub, established shortly after the pandemic was declared. The data points, for instance, range from comparisons of countries' vaccination rates to international scientific collaboration on COVID-19-related research. Moreover, while the policy briefs and data were published timely, keeping pace with the rapid development of the pandemic situation, the analysis exceeds a mere aggregation of simple data points. For instance, when examining the status of data infrastructure in the OECD countries, the IO measured timeliness, quality, and coverage of national healthcare datasets of the OECD countries (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2022a). Such engagement conveys the impression that the OECD was using the pandemic as a window of opportunity to expand its position to a global crisis manager. Thus, we ask in this article: To what extent can the OECD's pandemic response be evaluated as the role of a global crisis manager?

Considering the scope and scale of its mandate, it is reasonable to assume that global crises may serve for IOs to use them as windows of opportunities to expand their realm of influence. IOs are strategic actors that choose deliberate responses to external pressures in order to remain effective, autonomous, and secure (Barnett and Coleman, 2005). The OECD's work domain and the raison d'être have continued to develop throughout the IO's history (Leimgruber and Schmelzer, 2017, p. 25, 26): It “reinvent[ed] itself after it had lost its original purpose at the end of the Marshall Plan” and “developed into a warden of liberal capitalism and the West”, the role which it “redefine[d] again after the fall of the Berlin Wall” (Schmelzer, 2016, p. 29). Moreover, the OECD successfully used and profited from the 2007 Global Financial Crisis to evolve its role in global governance by complementing its economic growth narrative with inclusive, sustainable, and well-being components and contributing to the institutionalization of the G20 (Eccleston, 2011; Woodward, 2022, p. 47, 48). Given that the OECD not only has managed to survive but proactively exploited the drastically changing global circumstances, one can assume that the OECD may have used the COVID-19 pandemic once again for its internal deliberations in the realm of health.

In this setting, we investigate the OECD's response to the COVID-19 pandemic within the time frame between January 2020 and September 2022. Interview data and documents are analyzed using a heuristic frame of IOs as global crisis managers in health governance. As Olsson and Verbeek (2018) point out, approaches to crisis leadership tend to focus dominantly on the domestic level. Building primarily on the existing models (e.g., Boin et al., 2016), we distinguish between four phases of IO crisis management: sense-making, decision-making, learning, and position-making. By applying this framework, this research reviews the OECD's pandemic response and examines the extent to which the OECD functioned as a global crisis manager, given its unprecedented activities in global health governance during COVID-19. For the purpose of this article, a global crisis manager refers to those responsible for steering through transboundary crises as a control tower, coping with crises to protect the global population. A global crisis manager's maneuver encompasses entire managerial practices to non-routine phenomena, including prevention, mitigation, and removal of crises (Comfort, 1998). Being the first in-depth case study of the OECD's global pandemic response, this article opens up the black box of crisis management within the OECD and contributes to research on IO's crisis management.

This article is structured in the following way. It begins by outlining the conceptual framework for the analysis of crisis response. This section introduces how we conceptualize IO crisis management and how this frame can be applied to the OECD's activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Then, we briefly give an overview of the methodology and data collection applied for this study. The subsequent section explores the OECD's pandemic response by dividing the organization's engagement into four parts based on the conceptual framework. This analytic frame supports us in the empirical investigation of the unknown area of IOs' crisis leadership during an emergency. This work therefore neatly speaks to the study of IOs as autonomous actors (Barnett and Finnemore, 2004; Barnett and Coleman, 2005) as well as to the body of literature on reform processes in IOs (e.g., Bauer and Knill, 2007). Finally, drawing upon the analysis, the conclusion ties up the findings and answers whether the OECD's position during the COVID-19 pandemic can be consolidated as a global crisis manager.

2 A theoretical approach for analyzing IOs' crisis management

Today, we live in a “risk society,” in which collective as well as individual security pertains to one of the top priorities of political agenda (Beck, 1992). In such a risk society, various types of crises occur that may, at the core, threaten the fundamental structure, values, and norms of a system (Rosenthal et al., 2001; Coombs, 2007). Given the magnified scope, complexity, and political salience of modern crises, crisis leadership performance became more important than ever before (Boin and Hart, 2003). In times of a crisis, public leaders are expected to protect society with maneuvers, strategies, and actions, which, as a whole and in sum, formulate what encompasses crisis leadership (Muffet-Willett and Kruse, 2009; Boin et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2021). While scholars have expended efforts to build the body of crisis leadership literature, research in this field remains fragmented and is yet to outline comprehensive aspects of crisis leadership (Wu et al., 2021). One aspect of crisis leadership studies focus on is response strategies and patterns of specific levels of leaders in different crisis contexts: Boin et al. (2016), for example, offer a compelling theoretical framework to disentangle crisis leadership tasks, which outlines the critical stages in accordance with the proceeding phases of the crisis. Similarly, Pearson and Clair's (1998) crisis management procedure constitutes evolving strategic stages from the early perception phase to the final outcome phase. Likewise, Comfort (2007) describes four primary decision points in explaining emergency management process. What these frameworks have in common is that they differentiate between stages allowing for conceptualizing the extent to which a crisis has been managed by the significant actors.

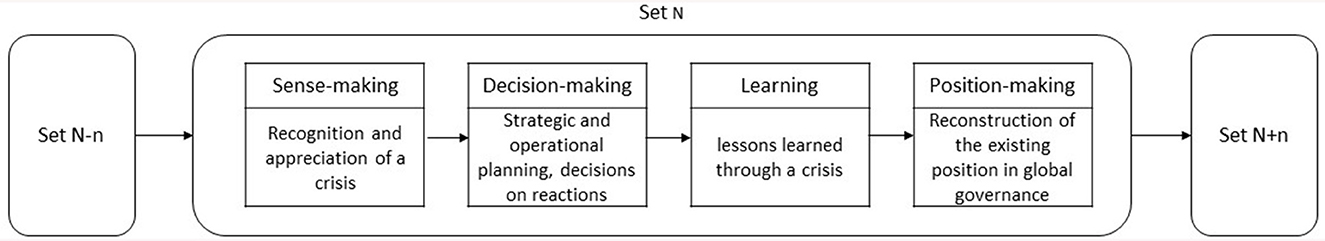

While such frameworks are initially developed for assessing crisis leadership of national governments, we adapt them for the analysis of IOs, such as the OECD, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic response. Our framework for analyzing IO crisis management comprises of four core stages: sense-making, decision-making, learning, and position-making (see Figure 1). First, sense-making indicates the recognition of a threat as a looming crisis. It is the first phase of crisis management which an IO invokes to monitor and catch threat signals that alert the potential to become a severe crisis. Sensing a crisis also includes the cognitive appraising; how significant the threat is and identifying to whom or to what the crisis poses a threat (Boin et al., 2016, p. 38). Second, the consecutive stage of decision-making requires appropriate reactions to the crisis. An IO decides how to cope with the situation, including concrete measures to remove the crisis and address the impacts. Countless factors intervene in the decision-making process, such as identifying the potentials of institutional settings and the possibility of coordination among involved groups (Sommerer et al., 2021). Third, reflecting on the crisis response, learning takes place and lessons are drawn. In this phase, an IO expands its range of potential behavior by processing information and experience it gathered and recognizing useful knowledge (Huber, 1991). This way, a crisis becomes a “collective memory” and serves as “a source of historical analogies for future leaders” (Boin et al., 2016, p. 15).

Forth, building upon the three previous stages, IOs can reconstruct their places in global governance in a position-making stages. Position-making occurs in the post-crisis phase as an aggregative construction of its locus in global social governance. As Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992) call it “position-taking,” IOs seek, conserve, and transform their positions in relations to other actors within their policy fields to accumulate resources and power. Unlike policymakers in national governments who are elected or endowed with certain positions, IOs compete to claim their identity and demarcate domains from each other to secure their positions in the policy networks they are involved in Kranke (2022). Thus, each IO's position changes over time as they respond to evolving circumstances (Béland and Orenstein, 2013). Previous studies indicate that some IOs used the COVID-19 crisis as an opportunity for institutional development or strategy enhancement (Ansell et al., 2020; Debre and Dijkstra, 2021; Ulybina et al., 2022). In reflecting on the peculiarity of IOs in crisis, it can be assumed that the OECD's pandemic response may have changed its position in the architecture of global social governance by reducing, remaining, consolidating, or constructing its scope of work domain and capabilities. Therefore, utilizing position-making, the OECD's eventual reconstruction of its position in global health governance can be evaluated.

In this framework of IOs' crisis management, earlier stages lay the basis for the later stages. That is to say, each of the four stages occurs in sequence within one set of crisis management. For instance, the OECD's sense-making of the COVID-19 pandemic shapes its decision-making. If we posit that the OECD perceived the pandemic as innocuous, no significant decision-making on how to react to the pandemic will follow. Put differently, non-decision-making will be the result of the decision-making in this case. Earlier experiences of crisis management (set N-n) may also pave the way for the current crisis management (set N) and future ones (Set N+n). From the standpoint of the scholarship of organizational learning, an organization learns through accumulating experiences and reflecting on them for better performance (Argote, 2011). Hence, crisis leadership may learn from the last cycles of crisis tasks. For instance, if the OECD created a crisis response mechanism during the 2008 global financial crisis and it did not prove effective, it would not use the exact mechanism for the next financial crisis. Likewise, the position the OECD built through past situations may configure its role during subsequent emergencies. In this regard, crisis leadership tasks are interlinked, both within a series of crisis tasks and beyond.

3 Methodology and data collection

The analysis of the OECD's COVID-19 pandemic response is based on a qualitative approach consisting of expert interviews and document analysis. Between October and November 2022, we conducted interviews with OECD Officials (n = 14) whose composition mirrors the organization's complex structure with various work areas and hierarchy levels. The interviewees were officials of the OECD Health Division (n = 8) and of other various Divisions and Directorates (n = 6). According to the snowball principle, we first contacted 3 core actors within the OECD who provided a representative overview of the IO's pandemic response and then reached out to additional key informants. In principle, in-person interviews were conducted in a one-on-one setting at the OECD headquarters in Paris and OECD Boulogne. Two interviews were conducted in a one-on-two setting on request, in which we interviewed two respondents at once in each session. Three interviews were conducted online. Interviews were semi-structured and ranged in length from 50 min to 70 min. A semi-structured approach allowed each interviewee to propose topics of relevance from their interests and experiences besides the pre-structured interview guide. The interview data were transcribed verbatim. The Interview data were coded using MAXQDA qualitative data analysis software in a combination of deductive and inductive coding techniques. The four stages of the aforementioned framework served as deductive categories for clustering data. Data within each category were then inductively subcategorized to find patterns in data. Additionally, we supplemented the interview findings with relevant documents published by the OECD and academic literature to gain an in-depth understanding of the interview data. For analyzing the OECD's pandemic-related policy proposals, we use the policy briefs released on the OECD's digital COVID-19 hub as well as the regular publications authored by various Directorates and Divisions. To understand the internal dynamics within the IO, we refer to the Secretary Generals' statements and the Council meeting reports. In sum, we traced and analyzed the process in which the OECD dealt with the COVID-19 pandemic from early 2020 until late 2022.

4 OECD's response to COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has been an unprecedented crisis that affected every part of the world and brought significant changes in the everyday lives of the global population. The COVID-19 pandemic exemplifies a crisis case as it posed threats to established regularities, and called for urgent reactions in an uncertain setting (Rosenthal et al., 2001). What makes the COVID-19 pandemic more prominent than other earlier pandemics was its transboundary nature, as the world has grown exponentially interconnected over the last decade. The dynamics of crises often cross geographical, functional, and temporary conditions, affecting broader regions and domains (Ansell et al., 2010). Responding to such border-crossing crises is challenging because it requires deliberation on competing interests, values, and opinions; the ability to improvise in the face of disturbed routines; horizontal and vertical communications; and societal trust and support (Behnke and Eckhard, 2022). As the world witnessed, the coronavirus rapidly invaded extensive areas and became one of the most challenging crises of the era across regions and domains. In this section, we explore how the OECD responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by applying the four stages: sense-making, decision-making, learning, and eventually position-making.

4.1 Sense-making

The OECD's institution-wide acknowledgment of the coronavirus was formulated at the end of February 2020 (Interview #3, #8, #10, #11, #13), which was followed by the official statement announced by the Secretary General at that time (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020a). Considering that the WHO's initial report on the novel coronavirus dates back to January 5th, nearly 2 months of a gap exists between the outbreak of the virus and the OECD's full-scale sense-making of the phenomenon. In these 2 months, when there was little information about the virus, different perceptions circulated within the organization.

On the one hand, the OECD Secretariat did not consider the virus a threat at all in the first month after its emergence. The spread speed and mortality rate of the coronavirus were not known at this point, which prevented the OECD from anticipating its significant effects. Also, at this early stage, the OECD did not consider itself to be a relevant party in taking specific actions to cope with the virus since the IO's mandate in global health does not include monitoring the emergence of a novel virus or its development into a pandemic (Interview #3, #10, #13). Although the global health governance has developed into the complex structure with multilayered actors including increasing number of IOs, it remains without dispute the WHO's official authority and responsibility to trace and report on pandemic-inducing viruses. Hence, the OECD neither felt the need for sense-making nor felt to have the jurisdiction to take action to inspire global sense-making of the coronavirus in the early phase.

Both the OECD Secretariat and the member states did not suppose the OECD as the appropriate leadership to confront the coronavirus. The OECD member states are precautious about the OECD's expansions of the work domains because they are keen to avoid overlapping responsibilities of multiple IOs for which they have memberships (Interview #14). In this context, when it comes to the health sector, the OECD member states tend to disapprove that the OECD has duplicate duties with the WHO (Interview #3, #8). Moreover, the member states anticipated such a novel contagion would emerge in low-income countries, specifically in countries of the Global South, and would not severely affect OECD countries (Interview #3, #12). In accordance with this perception, the OECD had no relevance to global infectious diseases. Interestingly, even though a limited part of the OECD Health Division was aware of the emergence of a pandemic that may well affect high-income countries and thus made claims for more tools to model those potentials, the member states refused to allocate budgets for them (Interview #8). As a result, when the coronavirus emerged, the OECD was “more or less invisible (…) because we (the OECD) weren't in a position to take a bold stand” (Interview #14).

On the other hand, the leading group of the OECD Secretariat, consisting of top-level officers of each Directorate, has paid close attention to the coronavirus since shortly after the outbreak. It suddenly became a central topic among them as early as mid-January through an external visit: The OECD holds monthly briefings where higher-level OECD Secretariat officials inform national ambassadors in the OECD Council on current economic, financial, and social issues. The G20 Sherpa of that time, from Saudi Arabia, participated in one of the briefings held in January and nervously sought expert opinions on the prospects regarding the coronavirus, raising awareness of the virus' potential economic impacts (Interview #10). Considering that the G20 Sherpa track discusses non-financial issues expanded from the G20 agenda, such as growth, trade, and environment, the meeting at the OECD may have been concerned with potential global economic impacts induced by the massive surge of the infection in China, which could disrupt manufacturing, trade, and other economic activities. Although the meeting led to the early recognition of the threat, the sense-making was limited to economic perspectives and did not extend to a more multidimensional contemplation (Interview #10).

The institution-wide sense-making of the crisis began only after the coronavirus spread to the European continent at the end of February 2020. Different parts of the OECD experienced anecdotal viral transmission firsthand and on a personal level: For example, a high-level official became a contact person from the first COVID-19 cases in Europe from a ski region in Austria, which hastened quarantine measures within the OECD; the very early, but rapidly spreading infections in the Lombardy region were perceived by some OECD officials with medical training as the lightbulb moment; the subsequent rapid spread of the virus in Northern Italy and the European countries made it clear to several OECD staff that the coronavirus would not remain one of the issues but become the only issue for the entire year (Interview #8, #10, #11, #13).

Interestingly, the OECD did not pay much attention to the non-European member states in which the first confirmed COVID-19 cases were reported earlier than the European member states, such as South Korea and Australia. This behavior can be attributed to the OECD's euro-centricity: Not to mention that the IO's founding members were dominantly Western European countries, the majority of the membership today still consists of European countries; a part of health-relevant projects at the OECD is funded by the European Commission; that the headquarter is located in Paris makes it difficult for non-European countries, especially countries in the Southern hemisphere, to participate in exchanges and decision-making processes in person (Interview #1, #10). Hence, the euro-centric view appears to have hindered the OECD from becoming attentive to the early experiences of non-European member countries.1

When the WHO's pandemic declaration was announced on March 11th, 2020, the OECD's sense-making followed promptly. However, it perceived the COVID-19 pandemic as an economic shock caused by a health crisis that affected all areas of society in the OECD member states (Interview #1, #14). This sense-making disentangles two salient features. First, the OECD's primary focus was the pandemic's economic costs – The IO defined the pandemic as an exogenous shock to the global economy resulting from the measures against the spreading of the disease, such as lockdown, and the consequent disruptions of economic systems and activities, for instance, supply chains, business, and labor market (Interview #4, #10, #13, #14). Unlike numerous other health-related IOs that perceived the pandemic as a health crisis per se, the OECD, primarily an economic organization, saw the health sector as only one among many sectors hit by the pandemic. Second, the OECD's sense-making exclusively concerned its member states. Previous global health diseases were out of the IO's interest due to their limited or virtually no impact on OECD countries (Interview #1). Hence, the OECD did not see a parallel between the COVID-19 pandemic and those earlier diseases that had had a major effect on public health in low- and middle-income countries. Instead, it rather appraised the 2008 global financial crisis and the looming climate crisis as equivalent comparisons to the COVID-19 pandemic regarding the economic impacts that burden the OECD countries (Interview #1, #2, #13). In other words, if the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic had not been significant enough on the economy of the OECD countries, the OECD would not have become alert on the pandemic.

4.2 Decision-making

Based on the sense-making of the COVID-19 pandemic as an economic shock that spilled over across all policy areas in the OECD countries, the OECD's decision-making accordingly supported the member states by minimizing the pandemic's encompassing impacts. For this purpose, the OECD's decision-making combined multifaceted top-down and bottom-up models that led to its horizontal approach to the COVID-19 pandemic response.

The Secretary-General's leadership was decisive in making top-down decisions within the OECD. In the first year of the pandemic, the OECD was undergoing internal dynamics with the upcoming election for a new Secretary-General since Angel Gurría, the incumbent Secretary-General at the time, was about to resign after 15 years of serving in this position. The OECD member states strengthened the checks and balances against the Secretariat, and they wanted to ensure the Secretariat's loyalty in supporting the member states by preserving their interests as the focus of the organization. As a result, the Secretariat was cautious in taking a bold stance (Interview #13, #14). This explains the OECD Secretariat's silence on some OECD member states' politicization of the pandemic, especially regarding the vaccine hoarding. When the OECD Secretariat criticizes some of the OECD countries' hindrance of global cooperation to distribute essential medical goods and vaccines, the concerned countries were uncomfortable about the critiques, leading the Secretariat to withhold its critical voices (Interview #10). In the unfavorable constellation, the Secretary-General decided to prove the OECD as a useful organization for the member states by supporting them in preserving their interests (Interview #11, #13, #14). Unsurprisingly, his decision-making led to the safe choice of utilizing the OECD's entrenched comparative advantage in analytical capabilities. He ordered the working bodies to provide the member states with evidence-based policy analyses through data points and policy briefs in a broad spectrum of policy sectors (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020b). To accelerate the process, each working body was allowed to decide on specific topics for policy analyses (Interview #11). Moreover, the Secretary-General ordered the establishment of a digital COVID-19 platform to use as a central channel to release all pandemic-relevant data points and policy briefs, which was a new type of communication next to conventional meetings and publications (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020b). This way, the Secretary-General's top-down decision-making set the direction for the organization's pandemic response in serving the member states as the provider of evidence-based policy options.

Accordingly, each Directorate and their Divisions set up their policy sector-specific strategies in both top-down and bottom-up directions within the units. Various units formed task force groups similar to the ones built in the earlier crisis during the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan (Interview #13). Other units relied on their management group consisting of senior officials (Interview #7). These groups served as decentralized centers across the OECD and concretized the implementation plans for the digital COVID-19 platform. In filling the platform with data points and policy briefs, their first decision-making included adapting the previously decided budgets and projects to the current situation to support the member states. Since the fixed budgets and projects allowed limited flexibility for adaptations, Directorates and Divisions restructured task priorities. This process picked up specific ongoing projects relevant to the pandemic, and then “covidized” them by integrating the pandemic as a central variable (Interview #4, #5). To provide simple examples, the regular data collection of member states' annual mortality added excessive mortality to assess deaths caused by the pandemic, and the indicators to measure health care performance appended the number of intensive care units (Interview #8). Staff of all levels proactively communicated and made suggestions based on their expertise in this decision-making process, and skipped lengthy approval procedures for timeliness (Interview #2, #8).

In addition, the decision to support the member states with analytical capabilities was strengthened by the OECD's government-like multisectoral structure. While known for the multidisciplinary approach with numerous Directorates and Divisions working on extensive policy fields, each part of the OECD presents different priorities and research directions. Such a structure often leads to differing – sometimes even contradictory - policy conclusions within the OECD, which challenges the consistency of the IO's core claims as an organization (Deacon and Kaasch, 2008; Mahon, 2009). They often work in silos, which explains different, competing, or even contradictory views and policy recommendations across sectors on the same topic (Interview #10). Aware of the tendency to function as independent units, the Secretary-General called for a whole-of-OECD response to the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the coherence across various sectors, represented by the term horizontality (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020b). This way, the OECD aspired to bridge the individual silos to each other. In other words, the whole-of-OECD approach served as an institution-wide core principle for the pandemic response, preventing “different heads of the same body [from] coming up with messages that are conflicting” (Interview #8). Toward this end, the OECD reeinforced intra-organizational arrangements and peer reviews across Directorates. In addition, policy briefs went through a quality control process to check whether the messages the different briefs delivered were consistent (Interview #8, #10, #13). For instance, the OECD avoided a policy brief claiming against the lockdown's fatal impacts on the economy in general, while arguing for the importance of the lockdown to protect the populations' health in another policy brief. Instead, approaching from the whole-of-OECD view, it suggested that despite the effectiveness of the lockdown as a containment measure, the lockdown may result in negative consequences in specific sectors, such as tourism (Interview 4, #10). Moreover, multisectoral collaboration within the organization was more encouraged than ever. As a result, new collaboration among units emerged, while the pre-existing collaboration became more intensive. For example, the Health Division newly partnered with the Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation in tracking the development of vaccines and expanded the previous collaboration with the Center for Entrepreneurship, SMEs and Cities for analyzing health inequalities at the regional level into investigating the pandemic's unequal impacts on the health status of socio-demographic subgroups (Interview #1, #4, #9). In this manner, the OECD improved its multidisciplinarity to interdisciplinarity for channeling coherent messages.

4.3 Learning

The OECD drew several lessons for crisis management throughout its response to the pandemic. First, the pandemic response reassured the asymmetric power constellation between the Secretariat and the member states. The OECD is driven by the demands of the member states and by the constraints to the financial contribution it receives from them. Consequently, the organization's work is tied to particular topics and projects. It is even more the case when a unit, such as the Health Division, relies primarily on voluntary contribution rather than on the central budget (Interview #1). This arrangement sets the barrier for the OECD to take stronger stances or actions during the COVID-19 crisis, allowing insufficient leeway to develop extensive pandemic responses. Given the restrictive flexibility, the OECD's strategy to leverage its established comparative advantages may have been the only option. By maximizing the given leeway and counting on the conventional capabilities, the OECD seems to have proved its usefulness to the member states (Interview #6). This experience may turn into a double-edged sword: While the OECD Secretariat reassured the member states about its loyalty and competence through the pandemic response, it may not lead the member states to confer more flexibility to the Secretariat. Moreover, the dependency on the member states also became clear regarding crisis-time communication. Numerous member states were in emergency mode and overwhelmed to cope with their domestic situation, particularly in the early phase of the pandemic. As a result, some simply did not appear at regular meetings without notice, and many responded to the requests of the OECD Secretariat with unusual delays when quick correspondence was vital (Interview #9, #10). Understanding the member states' exigency, the OECD Secretariat had to find a way to reduce the burdens for them but keep collecting national data for analytics (Interview #1, #2, #9). In short, recognizing the extent of the imbalanced power constellation during the crisis, the OECD now desires more operational leeway and effective communication method as a result of the experiences during the COVID crisis (Interview #1, #3, #8, #10).

Second, the importance of health in the global economic context became internalized within the OECD. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, except for the relevant Directorates and Divisions, there was no institution-wide perception of the importance of health as a policy field for the global economy. The dominant units of the OECD considered health to be a domestic policy area (Interview #6). However, the pandemic experience made it clear that health is a fundamental pillar of the global economy for which global cooperation is required (Interview #3, #6). Throughout the pandemic, the OECD witnessed that an infectious disease, which was not anticipated to affect the OECD countries so severely (Interview #1, #3, #12), disrupted labor markets, business, trade, and further economic areas. In this sense, the pandemic brought an institution-wide appreciation of the chain between health and the global economy.

Third, the pandemic experience led the OECD to integrate resilience in a broader sense in its organizational vision for the next decade (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021a). While the IO's resilience claim was mainly used in the context of economy and environment prior to the pandemic (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2019), the new strategic orientation now concerns broader societal sectors (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020b, 2021a). The resilience discourse has already unfolded in the OECD publications across policy fields, including health (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2022b, 2023a), finance (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020c,g), agriculture (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020d, 2021b), and infrastructure (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020e). In particular, the Health Division initiated a revisit to its core economic claim on efficiency of health care systems, re-evaluating the previous focus on maximizing the value of money with the emphasis on cost-efficiency of health care spending (Interview #6). For instance, it now considers what it once called “slack,” such as idle beds in hospitals, as essential elements to prepare for future shocks, recognizing that those spare capacities in systems are the key to enduring the impacts of unexpected events and building back quickly to normality (Interview #7). Also, the Health Division's emphasis on the importance of digital infrastructure became more persuasive in the context of resilience (Interview #10). A recent publication provides a more encompassing view of resilience in conceptualizing it as health systems' capacity to prepare for, absorb, recover from, and adapt to varying types of shocks, implying that resilience is not only about reserving surplus goods or infrastructure but building a system with the flexibility (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023a). As evident in many publications, resilience has become a new buzzword of the OECD's work.

However, whether the OECD can translate the resilience debate into concrete actions is unclear at this point. While building resilient systems and infrastructures require investments, some OECD member states have already undergone budget cuts due to the recession, for instance, in the health sector, where investments in resilience are most required (Interview #1, #12). Considering that “the OECD's priorities in health are guided by the member states,” it is difficult for the OECD to expect more demands and financial contributions from them for resilience-related work “unless it's a very strong leadership from the top [leadership of the OECD] that says you (the member states) need to understand that you have to invest in health; you have to look at it as an investment, not as a cost” (Interview #1). Yet, the current top leadership is “not necessarily that interested in health,” leading one to anticipate that “there are probably temporary shifts (in the focus shift from efficiency to resilience), but in terms of the long term evolution of the organization, … (the resilience debate is unlikely) going to change the way the OECD is and as an institution” (Interview #14). Therefore, despite the burgeoning discussion on resilience within the OECD, it is uncertain whether the OECD can plan resilience-related projects in the long term.

Furthermore, different parts of the OECD grasp the concept of resilience divergently, while there is a concern that many units of the OECD approach it with economic equations, perceiving resilience as a trade-off for efficiency. However, the real world is more complex than a linear explanation of trade-offs, inhibiting a clear-cut compromise of efficiency and resilience. For instance, if companies and shops remain open to some extent during the pandemic to avoid bankruptcy instead of a complete lockdown, it would not result in a linear increase in death caused by the COVID-19 infection. Instead, the number of death cases may increase exponentially (Interview #14). Calculations based on equations and models – the traditional way the OECD approaches problems and solutions – may hinder a contemplation of a fresh approach to resilience. Since the OECD is currently elaborating on the concept of resilience, it remains to be seen how the resilience debate will unfold.

4.4 Position-making

Generally speaking, the OECD's core identity can be outlined in three features. First, the OECD is an economic organization that applies the economic lens to a broad spectrum of policy fields. Second, the OECD's portfolio comprises one of the most extensive spectrums of policy fields outside the United Nations systems. Third, evidence-based analytics is the OECD's main currency for earning authority in global governance (Carroll and Kellow, 2011; Schmelzer, 2016; Woodward, 2022). In addition, unlike other IOs that hold hard power to order states to implement specific measures, the OECD counts on soft power to influence its member states by producing expertise that serves as a reference point for policymakers (Mahon and Mcbride, 2009; Martens and Jakobi, 2010). In short, the OECD functions like a think tank that delivers evidence for policy options, applying economic approaches to various policy fields.

Has the OECD's ingrained position changed through the COVID-19 pandemic response? Reflecting on the OECD's sense-making, decision-making, and learning capacities during the pandemic, it seems that the OECD has remained in its entrenched position, rather than acquiring a new post or expanding the boundaries of its work into new areas. The organization's pandemic response relied heavily upon the features mentioned above. The pandemic's economic impact on the member states motivated the OECD to initiate the pandemic response. Data collection and policy analyses ensued as the major response. All branches of the OECD covered various policy fields to redress the pandemic's impacts by putting together data points and policy briefs, ranging from economy and health to education and development. The economic lens was applied to the analytics, which is evident in the organization's outputs. For instance, based on the OECD's own categorization criteria, ca. 43% of the entire policy briefs directly speaks to economic-related topics under the categories of small and medium-sized enterprises, firms, tax, employment, and job retention schemes (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023b). Policy briefs in categories that are not necessarily relevant to economic issues also primarily reflect the economic perspective. For instance, policy briefs for containment measures analyze the impact of the lockdown on economic activity (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020f). Therefore, the OECD's COVID-19 pandemic response remained in its established approaches, capabilities, and domains.

Furthermore, another noteworthy point is that the OECD remained in its position as a research institute that produces and diffuses expertise, yet without the power to drive policymakers to the implementation of the policy ideas it suggests. During the pandemic, the OECD was “whispering in the ears of policymakers” (Interview #11) of the OECD member states by providing them with policy options. The implementation of such policy options, in the end, depends entirely on the domestic policymakers. Whether the OECD's whispering translates into concrete measures in the OECD countries is unknown (Interview #6). After all, the OECD is not the only information provider for the OECD member states. Rather, it is one among countless other factors which influence domestic decision-making processes. Hence, it is safe to argue that the OECD's pandemic response produced outputs, not outcomes. In view of this aspect, the position of the OECD before the pandemic, which relied on soft power and was limited to elicit tangible outcomes, did not change during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, some aspects still leave open the possibility for the OECD to change its position by expanding its working structure and domains. First, while multisectoral collaboration was not a new method, coordination across the organization under the whole-of-OECD approach was a conscious effort to cope with the crisis more effectively. The OECD could continue to improve coherence in its voice in various policy fields, as critics have long been widespread about incoherence both from within and outside the organization before the pandemic (Interview #10, #13). Second, the OECD's work may expand to include initiatives for preparing for global infectious diseases. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the OECD member states did not expect such an epidemiological virus to cause a significant crisis in the OECD countries, and therefore did not confer the organization with the budget to work on pandemic-related issues. However, during the pandemic, they invested in tools through which the OECD predicted the unfolding of the pandemic and modeled the consequences of different policy measures (Interview #3, #8). While it may have been a one-off investment, and the subsequent budget allocations would not include funding for pandemic-related projects, the tools developed during the pandemic can be utilized for the following health crises. Third, the discourse change toward resilience that emerged during the pandemic suggests the potential reorientation of the OECD's core belief system. Yet, as discussed in the earlier section, the OECD's consideration of resilience is limited in its conceptualization and integration into the work programs at this moment. Whether the IO's resilience discourse would be temporary or a departure for a fundamental restructuring of its worldview is yet uncertain. Fourth, the digital COVID-19 hub appears to have been a new experience in channeling the OECD's work to the member states and beyond, which may remain in the future as a regular mechanism to deliver crisis responses. The idea of setting up a digital platform to bring together relevant data points and analyses is already adapted to respond to the issues around the war in Ukraine, which is structured in the same way as the COVID-19 hub. This adaptation allows us to expect the OECD to continue to use the digital channeling mechanism for significant global challenges in the future.

Overall, when comparing the OECD's pandemic response with its conventional orientations and activities, the OECD's position-making through the COVID-19 pandemic can be summarized as, at least, a maintenance of the established role as a policy advisor and, at best, a consolidation of it. It is logical that the reliance on pre-existing work modus does not result in a new position, although the pandemic response opened a new door for the OECD to supplement or alter its approaches, tasks, tools, and communication mechanism.

5 Conclusion: the traditional policy advisor, not a global crisis manager

This study aimed to assess the OECD's response to the COVID-19 pandemic to determine if the IO has undergone a shift in its global role during the crisis. By developing the framework of crisis leadership tasks, this article analyzed how the OECD applied sense-making, decision-making, learning, and position-making in a crisis situation. Based on original interview material and process tracing, our empirical analysis showed that in the sense-making phase, the OECD neither took any actions nor was prepared for the pandemic response, although the top leadership was aware of the coronavirus' potential economic impacts early on. The organization-wide sense-making was gradually built on the IO's traditional view, namely perceiving the pandemic as an economic shock that spilled over to all policy areas. In the following decision-making stage, the OECD had only limited leeway to respond to the crisis due to its institutional, rather static, set-up. As a result, the IO's strategic focus was to maximize well-established capabilities in data collection and policy analysis to provide the OECD countries with policy options based on expertise. The outputs covered an extensive spectrum of policy fields while keeping an economic focus. Whereas multisectoral collaboration was not a novel method, coordination across the organization under the whole-of-OECD approach was a new effort to cope with the crisis more effectively. The learning phase reflects the importance of health in a global economic context as well as the realization of the more profound influence of the member states on working topics, scopes, and structure as than known before the pandemic, which allowed insufficient room for the OECD to move and act as quickly as needed during the crisis. Taken together, the OECD's position-making in global governance did not show significant moves in establishing new capabilities or expanding the work domains into a new area.

In this contribution, we find that the OECD as an institution did not move beyond its previous positions in global health governance. The OECD consolidated its entrenched role as an expertise provider by utilizing its conventional comparative advantages in analytical skills, economic perspective, and multisectoral structure rather than becoming a global crisis manager. First, as shown in the section on sense-making, monitoring infectious diseases is not the OECD's responsibility. The OECD does not have a binding mandate to track the incidence and spread of viruses in populations. The OECD's pandemic response was now-casting of the development and impact of the pandemic rather than forecasting the potential of the pandemic, as reflected in both phases of sense-making and decision-making phases. Second, the OECD does not have the authority to determine or implement specific measures, considering that the OECD relies on soft power instead of hard power to drive countries to take specific actions. This is the case for the pandemic response as well, as seen in the learning and position-making phases. The organization's main function remained in producing data points and policy briefs that served policymakers as information for making decisions. Last but not least, the OECD's response was driven by and targeted exclusively the OECD member states in all crisis leadership tasks. The organization's motivation to engage in the pandemic response arose from witnessing the pandemic's surprisingly extensive impact on the OECD countries. Accordingly, the response was designed in the context of the pandemic's impacts on the OECD countries and thus best applicable in these countries. Despite its unusual prominence in health issues during the COVID-19 crisis, the OECD's crisis management did not go beyond its conventional modes of governance.

This research extends not only our knowledge of the OECD's emergency practices in times of public health crisis, but more generally contributes to the burgeoning literature of IOs' crisis management. In our view, this research agenda can be advanced in several directions to draw more far-reaching conclusions regarding IOs' dynamics during different types of crises. Our theoretical framework for analyzing IOs' crisis management can help future research on crisis responses by further IOs and regional organizations, such as Association of Southeast AsIan Nations (ASEAN) and African Union (AU). In particular, studies on IOs that are not typically considered as a central actor in specific policy fields – as in our case the OECD in global health governance – may provide a more comprehensive picture of the architecture of global governance and the actors within it.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the interview data is not publicly available as the data includes the personal information of interviewees. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to SM, c29tZWllckB1bmktYnJlbWVuLmRl.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KM: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This article is a product of the research conducted in the Collaborative Research Center 1342 “Global Dynamics of Social Policy” at the University of Bremen. The center was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)-project number 374666841-SFB 1342. In the framework of the project, eight global and regional organizations' crisis management in the COVID-19 pandemic are analyzed.

Acknowledgments

We thank reviewers for their valuable comments. Previous versions of this work have been presented the International Political Science World Congress in Buenos Aires and the World Society Foundation-Research Committee 55 Pre-Conference to the International Sociological Association World Congress of Sociology in Melbourne in 2023. We thank the panels and their valuable comments. We also thank Dennis Niemann and Alexandra Kaasch for their constructive comments on the paper and Alfred Pallarca and Tim Frei for editing it.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The OECD's later efforts to engage with the non-European OECD countries with earlier cases were also limited, since their policy responses became close to zero-COVID strategies, which would not be applicable to the European OECD member states (Interview #10).

References

Ansell, C., Boin, A. R., and Keller, A. (2010). Managing transboundary crises: identifying the building blocks of an effective response system. J. Conting. Crisis Manage. 18, 195–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2010.00620.x

Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., and Tofring, J. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic as a game changer for public administration and leadership? the need for robust governance responses to turbulent problems. Pub. Manage. Rev. 23, 949–960. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272

Argote, L. (2011). Organizational learning research: past, present, and future. Manage. Learn. 42, 439–446. doi: 10.1177/1350507611408217

Barnett, M., and Coleman, L. (2005). Designing police: interpol and the study of change in international organizations. Int. Stu. Q. 49, 593–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00380.x

Barnett, M., and Finnemore, M. (2004). Rule for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bauer, M. W., and Knill, C. (2007). Management Reforms in International Organizations. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Behnke, N., and Eckhard, S. A. (2022). Systemic perspective on crisis management and resilience in Germany. Zeitschrift für Public Policy, Recht und Manage. 15, 3–19. doi: 10.3224/dms.v15i1.11

Béland, D., and Orenstein, M. A. (2013). International organizations as policy actors: an ideational approach. Global Soc. Policy 13, 125–143. doi: 10.1177/1468018113484608

Boin, A., Kuipers, S., and Overdijk, W. (2013). Leadership in times of crisis: a framework for assessment. Int. Rev. Pub. Admin. 18, 79–91. doi: 10.1080/12294659.2013.10805241

Boin, R. A., and Hart, P. (2003). Public leadership in times of crisis: Mission impossible? Pub. Admin. Rev. 63, 544–553. doi: 10.1111/1540-6210.00318

Boin, R. A., Hart, P., Stern, E. K., and Sundelius, B. (2016). The Politics of Crisis Management: Public Leadership under Pressure, 2nd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2016).

Bourdieu, P., and Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press

Brown, T. M., and Ladwig, S. (2020). COVID-19, China, the world health organization, and the limits of international health diplomacy. Am. J. Pub. Health 110, 1123–1172. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305796

Carroll, P., and Kellow, A. (2011). The OECD: A Study of Organizational Adaptation. Gloucestershire: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Comfort, L. K. (1998). Managing Disaster: Strategies and Policy Perspectives. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Comfort, L. K. (2007). Crisis management in hindsight: cognition, communication, coordination, and control. Pub. Admin. Rev. 67, 189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00827.x

Coombs, T. W. (2007). Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing, and Responding. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Deacon, B., and Kaasch, A. (2008). “The OECD's social and health policy: neoliberal stalking horse or balancer of social and economic objectives?” in The OECD and Transnational Governance, eds R. Mahon and S. McBride (Vancouver: UBC Press), 226–241.

Debre, M. J., and Dijkstra, H. (2021). COVID-19 and policy responses by international organizations: crisis of liberal international order or window of opportunity? Global Policy. 12, 443–454. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12975

Dimitrakopoulos, D. G., and Lalis, G. (2022). The EU's initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic: disintegration or ‘failing forward'? J. Eur. Pub. Policy. 29, 1395–1413. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2021.1966078

Duggan, J., Morris, S., Sandefur, J., and Yang, G. (2020). Is the World Bank's COVID-19 Crisis Lending Big Enough, Fast Enough? New Evidence on Loan Disbursements. CGD Working Paper No. 554. Available online at: https://www.cgdev.org/publication/world-banks-covid-crisis-lending-big-enough-fast-enough-new-evidence-loan-disbursements

Eccleston, R. (2011). The OECD and global economic governance. Austr. J. Int. Affairs 65, 243–255. doi: 10.1080/10357718.2011.550106

Gallagher, K. P., and Carlin, F. M. (2020). The Role of IMF in the Fight Against COVID-19: The IMF COVID Response Index. CEPR COVID Economics Paper no. 42. Available online at: https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2020/09/15/the-role-of-imf-in-the-fight-against-covid-19-the-imf-covid-19-response-index/ (accessed February 1, 2023).

Huber, G. P. (1991). Organizational learning: the contributing processes and the literatures. Org. Sci. 2, 88–115. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2.1.88

Kaasch, A. (2021). “Characterizing global health governance by international organizations: is there an ante- and post-COVID-19 architecture?” in International Organizations in Global Social Governance, eds K. Martens, D. Niemann, and A. Kaasch (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 233–254.

Kranke, M. (2022). Exclusive expertise: the boundary work of international organizations. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 29, 453–476. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2020.1784774

Leimgruber, M., and Schmelzer, M. (2017). The OECD and the International Political Economy Since 1948. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Leisering, L. (2021). Social protection responses by states and international Organizations to the COVID-19 crisis in the global south: stopgap or new departure? Global Soc. Policy. 21, 396–420. doi: 10.1177/14680181211029089

Mahon, R. (2009). The OECD's discourse on the reconciliation of work and family life. Global Soc. Policy 9, 183–204. doi: 10.1177/1468018109104625

Mahon, R., and Mcbride, S. (2009). Standardizing and disseminating knowledge: the role of the OECD in global governance. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1, 83–101. doi: 10.1017/S1755773909000058

Martens, K., and Jakobi, A. P. (2010). Mechanisms of OECD Governance: International Incentives for National Policy-Making? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moore, S., Hill, E. M., Dyson, L., Tideslev, M. J., and Keeling, M. J. (2022). Retrospectively modeling the effects of increased vaccine sharing on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Med. 28, 2416–2423. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02064-y

Muffet-Willett, S., and Kruse, S. (2009). Crisis leadership: past research and future directions. J. Bus. Continuity Emerg. Plan. 3, 248–258.

Olsson, E. K., and Verbeek, B. (2018). International Organizations and crisis management: do crises enable or constrain IO autonomy? J. Int. Relat. Dev. 21, 275–299. doi: 10.1057/s41268-016-0071-z

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2019). 2019 Strategic Orientations of the Secretary-General. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/SOs%20SG%20-%20CMIN(2019)1%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed February 1, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020a). Coronavirus (COVID-19): Joint Actions to Win the War. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/about/secretary-general/Coronavirus-COVID-19-Joint-actions-to-win-the-war.pdf (accessed August 31, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020b). 2020 Strategic Orientations of the Secretary-General. (2020). Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/mcm/SO-CMIN-2020-1-EN.pdf (accessed February 1, 2023.).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020c). Tax and Fiscal Policy in Response to the Coronavirus Crisis: Strengthening Confidence and Resilience. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tax-and-fiscal-policy-in-response-to-the-coronavirus-crisis-strengthening-confidence-and-resilience-60f640a8/ (Accessed february 1, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020d). COVID-19 and the Food and Agriculture Sector: Issues and Policy Responses. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-the-food-and-agriculture-sector-issues-and-policy-responses-a23f764b/ (accessed February 1, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020e). Building Resilience: New Strategies for Strengthening Infrastructure Resilience and Maintenance. OECD Public Governance Policy Paper no. 5. Paris: OECD.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020f). Walking the Tightrope: Avoiding a Lockdown while Containing the Virus. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/walking-the-tightrope-avoiding-a-lockdown-while-containing-the-virus-1b912d4a/ (accessed February 1, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020g). Supporting the Financial Resilience of Citizens throughout the COVID-19 Crisis. Available online at: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=129_129607-awwyipbwh4&title=Supporting-the-financial-resilience-of-citizens-throughout-the-COVID-19-crisis (accessed February 1, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2021a). Trust in Global Cooperation: The Vision for the OECD for the Next Decade. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/mcm/MCM_2021_Part_2_%5BC-MIN_2021_16-FINAL.en%5D.pdf (accessed September 1, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2021b). Keep Calm and Carry on Feeding: Agriculture and Food Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/keep-calm-and-carry-on-feeding-agriculture-and-food-policy-responses-to-the-covid-19-crisis-db1bf302/ (accessed February 1, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2022a). Health Data and Governance Developments in Relation to COVID-19: How OECD Countries are Adjusting Health Data Systems for the New Normal. OECD Health Working Paper no. 138. Available online at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-data-and-governance-developments-in-relation-to-covid-19_aec7c409-en (accessed August 31, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2022b). Investing in Health Systems to Protect Society and Boost the Economy: Priority Investments and Order-of-Magnitude Cost Estimate (abridged version). Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/investing-in-health-systems-to-protect-society-and-boost-the-economy-priority-investments-and-order-of-magnitude-cost-estimates-abridged-version-94ba313a/ (accessed February 1, 2023).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2023a). Ready for the Next Crisis? Investing in Health System Resilience. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2023b). Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/policy-responses (accessed June 1, 2023).

Pearson, C. M., and Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. The Acad. Manage. Rev. 23, 59–76. doi: 10.2307/259099

Rosenthal, U., Boin, R. A., and Comfort, L. K. (2001). Managing Crises: Threats, Dilemmas, Opportunities. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas PublisherLTD.

Schmelzer, M. (2016). The Hegemony of Growth: The OECD and the Making of the Economic Growth Paradigm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sommerer, T., Squatrito, T., and Tallberg, J. (2021). Decision-making in international organizations: institutional design and performance. The Rev. Int. Org. 17, 815–845. doi: 10.1007/s11558-021-09445-x

Ulybina, O., Ferrer, L. P., and Pertti Alasuutari, P. (2022). Intergovernmental organizations in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: organizational behaviour in crises and under uncertainty. Int. Sociol. 37, 415–438. doi: 10.1177/02685809221094687

Van Hecke, S., Fuhr, H., and Wolfs, W. (2021). The politics of crisis management by regional and international organizations in fighting against a global pandemic: the member states at a crossroads. Int. Rev. Admin. Sci. 87, 672–690. doi: 10.1177/0020852320984516

Woodward, R. (2022). The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 2nd Edn. London: Routledge.

Wu, Y. L., Shao, B., Newman, A., and Schwarz, G. (2021). Crisis leadership: a review and future research agenda. The Leadership Q. 32, 101518. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101518

Youde, J. (2020). How ‘Medical Nationalism' is Undermining the Fight Against the Coronavirus Pandemic. World Politics Review. Available online at: https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/how-medical-nationalism-is-undermining-the-fight (accessed February 1, 2023).

Keywords: OECD, COVID-19, crisis management, pandemic response, global health governance

Citation: Meier S and Martens K (2024) A global crisis manager during the COVID-19 pandemic? The OECD and health governance. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1332684. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1332684

Received: 03 November 2023; Accepted: 18 January 2024;

Published: 06 February 2024.

Edited by:

Eric E. Otenyo, Northern Arizona University, United StatesReviewed by:

Phillip Nyinguro, University of Nairobi, KenyaAliaksandr Novikau, International University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Copyright © 2024 Meier and Martens. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sooahn Meier, c29tZWllckB1bmktYnJlbWVuLmRl

Sooahn Meier

Sooahn Meier Kerstin Martens

Kerstin Martens