94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Polit. Sci. , 08 March 2024

Sec. Comparative Governance

Volume 6 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2024.1331229

This article is part of the Research Topic Trust, Participation and Pandemic Politics in Africa View all 5 articles

This paper examines declining political trust at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in the informal settlements of Mukuru Kayaba, Mukuru kwa Njenga, and Mukuru kwa Ruben; part of the Mukuru Informal Settlement located in Nairobi, Kenya. The average resident lives on $1.90–$3.50/day with no financial security net. During the COVID-19 pandemic governmental restrictions on movement and business operations, residents of Mukuru living at the extreme poverty level were unable to meet their basic needs. Trust in government was diminished, made worse by excessive force from armed officers of the Provincial Administration. Using qualitative and quantitative data, this research concludes that the lack of state support during the pandemic has led to further decline of political trust from residents of Mukuru.

The proliferation of informal settlements is one of the clearest exemplifications of social exclusion in developing economies (Mahabir et al., 2016, p. 405). Slum dwellers are critically needed in terms of labor to run the city and for politicians to win enough votes to win elections yet made even poorer by social and economic exclusion. In 2010, a global assessment conducted by UN-HABITAT (2010) revealed that 828 million or 33% of the urban population in developing countries resides in slums. In sub–Saharan Africa, 62% of the urban population resides in such slums. In Nairobi, Kenya, 70% of the population live in slums (KIPPRA, 2023). Urbanization is viewed as a major factor that drives the proliferation of slums because of the phenomenal urban transition in Africa. This is evidenced by the fact that, for example, in 1950, 14.5% of the population in African countries resided in urban areas; by 2007, the level of urbanization had increased to 38.7%. These statistics concur with Ravallion et al. (2007, p. 1,415) opine that while the level of urbanization in Africa increased from 29.8% in 1993 to 35.2% in 2002, the urban share of poverty increased from 24.3 to 30.2 % within the same period. The major consequence of these developments has been the urbanization of poverty, where poverty and its concentration has moved to urban areas (UN-HABITAT, 2017, p. 24). In 2020, the state instituted containment measures in Kenya's urban capital, Nairobi. Nairobi is surrounded by nearly 19 slums. The most populous is Kibera. The largest in land size is Mukuru, divided into four quadrants and 30 villages (Pashayan, 2021, p. 3). The southernmost quadrant is Mukuru Kayaba, where qualitative interviews were held for this research. Two additional quadrants, Mukuru kwa Ruben and Mukuru kwa Njenga were accessed for gathering quantitative data. During the pandemic, the state deployed the provincial administration, a colonial relic for social control. Tasked with enforcing curfew measures, including all four quadrants of Mukuru, the restrictions on movement quickly evolved to the use of excessive force against the urban poor and distrust in the government by Mukuru locals.

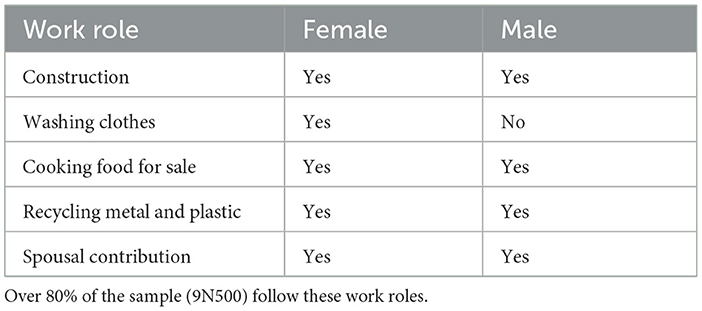

The urban poor who earn their livelihood from wage labor were affected by the closure of businesses in the industrial area. Mukuru residents who worked odd jobs as gardeners, housekeepers, or metal recyclers struggled to meet their daily needs. Many residents of informal settlements earn from $1.90 to $3.50/day and have no savings or financial safety net provided by the government. Working every day is critical to meet household needs. The Provincial Administrators used excessive force against residents who needed income to buy food and water. An extreme case is Nairobi's Kariobangi slum, bulldozed in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic (Citizen Digital, 2022). When obtaining basic needs was restricted, political distrust increased. Table 1 offers a look at comparative labor roles of men and women from Mukuru kwa Ruben and kwa Njenga slums.

Table 1. Comparative labor roles per 250 female + 250 male respondents Mukuru kwa Ruben and kwa Njenga.

The context of how the slums arose begins before Kenya's independence in 1963. Nairobi was intended by colonizers to be a simple resting stop in 1896 for construction workers building the Uganda Railway to the port of Mombasa. With its high elevation, the place of cool waters (Nyrobi) offered a cool resting campsite for construction workers. Later it boasted a railway house, workspace, and offices (Kenya Railways, 2023). As Nairobi, now spelled Nairobi, grew into a bustling hub, land surrounding the railway that was not owned by the government was bought by white settlers. After independence, the new government under President Jomo Kenyatta took ownership of land owned by the colonial government, and white settlers sold their land to private owners. Poor records were kept, and in some cases no records of land ownership were filed (Muungano Alliance, 2017).

During the onset of modernization in the 1970's, Kenyatta repurposed the land for light industry to create jobs (Muungano Alliance, 2017). Per the government decree, new landowners were stipulated to develop the land within 2 years and could not borrow against it nor could they sell the land until it was developed (Muungano Alliance, 2017). A quarry was one of the first businesses there. Other factories were added, including an air-sea-freight forwarding service owned by Mr. Ruben. Some of the land was acquired by former quarry workers in collaboration with other individuals.

By the late 1970's and early 1980's, people began streaming into the city from the rural areas in search of employment. With vacant land adjacent to the new industries offering jobs, people without means for proper housing put up shacks made of cartons, mud, discarded wood, and corrugated tin sheets. There was steady growth of these informal settlements, and the local government soon declared that the land was condemned and unsuitable for human habitation. Nevertheless, as the number of people and their dependents increased, so did the slums. These areas were especially beneficial to job seekers due to their proximity to the industrial centers and minimal cost in terms of transportation. Moreover, a community was developing.

As the size of these settlements grew, they were organized into villages. The villages eased the provision of security, services, administration, and accessibility. There was also the designation of leaders for the villages. These leaders were the overall head men, women's' leaders and youth leaders to address the needs of the local population. There has also been the proliferation of local organizations, especially for social and economic empowerment. These covered local needs such as the unity of traders, women and local saving and credit societies (SACCOs). The government, through local administration, maintains its presence in the area as Assistant County Commissioners, Chiefs and Assistant Chiefs. There are also security installations in the form of Administration Police Posts in the area to boost the area's security.

It is important to note that the social context is the setting in which the actors are situated. These actors—the subaltern communities, local administration, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs)—all have a stake in the wellbeing and governance of the communities. In this setting -pervaded by economic, social, political, cultural, and technological aspects- that is where the problem under study is situated. The new constitutional dispensation, which entrenches participation and inclusion, serves as a manifesto, a socioeconomic and political contract between the rulers and the ruled. Through its provisions, these citizens are afforded social, economic, and political rights. The access and utilization of these rights is crucial for the wellbeing and governance of subaltern communities. It is also important to address issues around the concepts of economic and social exclusion that disenfranchise millions of individuals and communities in slums. This paper then addresses inclusion and participation as fundamental rights that contribute to the dignity of the human being. It espouses principles articulated by Sen (1999, p. 10) who viewed development as the freedom to choose and chart the destiny that improves the wellbeing of individuals as they wish to live, and their communities; especially the poorest in society.

Slums are portrayed as institutional failures in housing policy, housing, finance, public utilities, local governance, and management of land tenure (Mahabir et al., 2016, p. 404). Strategies adopted by African countries to tackle the problem have ranged from benign neglect, forced evictions, and demolitions as in the case of Nairobi's Kariobangi slum, bulldozed in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic (Kinyanjui, 2020, p. 1). Other approaches include; resettlement or relocation, elemental slum upgrading and other enabling strategies (Nabutola, 2004, p. 7; Seeta, 2019, p. 3). Although many of these strategies have failed, they are still being persistently implemented across the continent (Nzau and Trillo, 2020, p. 2).

The Provincial or Public Administration (PA) is a creature of the colonial era (Omanga, 2015, p. 5). It was established as an instrument of the state whose activities included general representation of the authority of the executive at the local level, co-ordination of government activities in the field and chairing several committees at the local level. Under the old constitution, the co-ordination of central government policies and development programs at the local level was done by this department (Bagaka, 2011, p. 3). The Provincial Administration was a department in the Office of the President. The system divided Kenya into eight provinces; and then into districts, division, locations, and sub-locations. They supervised central government ministries at the provincial and district levels but also coordinated their programs and policies. They served as the representatives of the President in local areas and exercised upward accountability because they served at the pleasure of the president. One of the reasons activists and architects of the new constitution sought for the scrapping of this outfit is that they followed the orders of the executive without question. This meant that even when people were disenfranchised as a result, they could not change their actions. They, therefore, came to symbolize repression, dictatorship, impunity, and authoritarianism (Bagaka, 2011, p. 4).

The new constitution phased out provinces and introduced 47 counties which are further sub-divided into sub-counties, wards, locations, and sub-locations. Some of the powers the PA had were taken away and given to the County Executive Committee (CEC). The CEC is headed by a governor and has a cabinet of county executive committee bureaucrats (Bagaka, 2011, p. 6). The transfer of powers from a central government bureaucrat to a locally elected governor is meant to establish a culture of accountability. The fear of arbitrary uses of power in Kenya is still eminent with the retention of the PA (Mbai, 2003, p. 115). Even the restructuring of the outfit has not led to better sentiments. Some reasons give observers pause; such as the fact that under the Constitution of Kenya (2010), the functions of the CEC and the PA bear a resemblance. The 2007 Scheme of Service for field administrative officers within the PA lays out their roles in the field. Some of the role's conflict with those of the CEC as mentioned above. Scholars such as Bagaka (2011, p. 7) have argued that they now form the basis of the intergovernmental relationship between the central government and the county governments.

Intergovernmental relations are the complex network of overlapping and interlocking roles with various levels of government. They go deeper and are more involved than the formal understanding of devolution (Bagaka, 2011, p. 10). They also refer to the set of policies and mechanisms by which the interplay between various levels of government serves a common geographical area (Shafritz et al., 2010, p. 152). Inter-governmental relations are oriented toward governmental issues rather than political ones. In Articles 176, 186, and 189 of the Constitution of Kenya (2010), provision for a political structure is made. Under this constitutional structure, there is an administrative structure created to carry out specific governance functions. The reality is that both the political and administrative structure are important in governing the country.

Although the Constitution of Kenya (2010) enumerates the functions of both the national and county governments, implementing a constitution is more than ceding and sharing authority. There are issues such as education, health, terrorism, security, disaster management and peacebuilding that have both national and local implications. They are then in the purview of various levels of government. This system in Kenya then acts as a nexus between national and county governments (Bagaka, 2011, p. 7). In 2012, following the signing of an Executive Order by the then President Kibaki, officers from the former arrangement were formally designated as national government administrative officers (NGAO; The Standard, 2014, p. 1). They included 47 County Commissioners, Deputy County Commissioners, Assistant County Commissioners, Chiefs and Assistant Chiefs.

Section 17 of the Constitution of Kenya (2010) stipulates that within 5 years the “new” formations should have undergone a restructuring. This, however, has not happened and the administrative operatives function as they did before. Therefore, to an extent, they maintain the same aloofness in their operational history (Constitution of Kenya, 2010, p. 6) Also, the vestiges of the past in the form of consolidation of power by Kenya's post-colonial rulers has affected their ethical standards (Mbai, 2003, p. 114). This has exacerbated the marginalization of local administration and led to weak accountability and capacity to respond efficiently to all residents. The inability to devise effective strategies to deal with informal settlement communities has affected the lives of the residents (Menon et al., 2008, p. 21).

The use of created or invited spaces as entrenched in the new constitutional dispensation is a contested notion. However, these “new” spaces can be contextualized and used to achieve social sustainability of these communities. The Constitution of Kenya (2010) entrenches the concept of citizen participation as well as the expansion of social and economic rights (Article 213). These second-generation rights are further girded by the articulation of civil and political rights. This is a departure from the ideas of Marshall which mostly dealt with political and civil rights. This is by virtue of the Constitution of Kenya (2010, 12) emphatically laying out in Article 1 that all power and sovereignty lies with the people. This greater enunciation and articulation of the bundle of rights due to an individual serves as the bedrock on which there can be a contextualization of the articulation of the rights, powers, and spaces that the urban poor can agitate for. The urban poor are also a significant bloc whose needs stand at the periphery of the mainstream. The problem of marginalization and exclusion affects how the needs and rights of these communities are addressed. As noted by various scholars such as Kabeer (2002, p. 31), it is important that the rights of such subaltern communities are organized from the bottom through the applied agency of these communities.

The UNDP defines trust in public institutions as “the trust that members of a community have in the institutions presiding over that community;” a conceptual framework between citizens and their leaders for improved governance (2021). Theoretically, Anthony Giddens adds notions of vesting confidence in persons or systems made from a “leap of faith” or lack of information (1991). to the lack of information coupled with independent components within government, the System Wide Trust theory posits that “failure in one component can have a negative effect on trust in other components.” However, through Vertical Trust, the opposite contagion can occur. Vertical trust is a form of political trust and refers to trust that spans from lower to higher government authorities, while horizontal or social trust refers to trust in other people at the same level of authority (Eek and Rothstein, 2005, p. 3). The contagious spread of mistrust can be reversed with contagious spread of trust if governments invest in meaningful engagement.

The World Bank open knowledge repository posits vertical trust as a “key factor” of morale across varying cultures and institutions (Kumagai and Iorio, 2019). The willingness of people to obey the law and to trust authorities is closely related to whether they consider they received fair treatment by authorities, both in terms of procedures and outcomes. If authorities allocate outcomes according to procedures that are regarded as fair, recipients are more willing to voluntarily accept the outcomes they receive from the authorities. This is known as the fair process effect (Eek and Rothstein, 2005, p. 3). Recipients judge the outcome they are allocated through fair procedures as better than outcomes from unfair procedures, even if the substantial outcome is negative. Perceived procedural fairness is only relevant for judging the outcomes received when people lack information about whether the authority cannot be trusted.

Trust is an important parameter in understanding the societal behavior of citizens. Here it is common to measure the level of social capital in representative samples of different nations. Yamagishi (1986, p. 5) developed a tool to measure the level of horizontal trust; low-, medium-, and high- level trusters on the trust scale. This scale has been employed at a national level to understand national differences in the relationship between the horizontal trust of people and their willingness to co-operate with one another. High levels of horizontal trust correlate with several societal outcomes such as greater economic growth, functioning democratic processes and happier and healthier citizens. High levels of horizontal trust also led to high levels of vertical trust. The logic is that when people lose their trust in a person who represents a key authority, they reason that if the authority is bad/unfair then others might be equally bad (Oyugi and Ochieng, 2020, p. 225). So, vertical trust affects horizontal trust: how people relate with authorities affects how they relate to one another.

Political scientists Pye (1991, p. 489) and Welch (2013, p. 10) opined that political culture is a crucial component in people accepting the legitimacy of the political system of their country. It is how people view the political system and their belief in its legitimacy. Therefore, the building blocks of a political culture are the beliefs, opinions, and emotions of the citizens to their form of government. Dalton (2005, p. 150) carried out a study on data generated from advanced economies into levels of trust in government held by individuals in these countries. He concluded that it was due to the changing expectations of citizens rather than the failure of governments in leadership that led to a loss of political support in these countries. He also noted that in most instances, it was the upper classes that seem to unfairly benefit and have a greater appreciation and understanding of the political system's workings.

This contrasts with development, in that governments have failed to provide even the most basic needs. This has led to the erosion of political support and goodwill, especially among the lower classes that are most desperately in need of government largesse. Efforts to improve the situation have led to radical changes in national constitutions. These legal, economic, and social documents have been changed to reflect societal desire for equity and justice. The legal thresholds and definitions enshrined in the supreme law of the land are meant to act as a lever to open up spaces; especially invited spaces. The challenge then becomes making the citizen an active participant in the process of governance.

Almond and Verba (1963a, p. 231) identified three types of orientation of the citizen's attitude toward participation. They theorized that the first orientation was parochial; this individual does not participate and has no knowledge or interest in the domestic political system. The second individual was described as a subject; one that has some interest in and awareness of political institutions and rules. The last individual is a participant who indeed has a strong sense of confidence and influence in understanding the domestic political system. This typology goes hand in hand with their definition of political culture. They define the political culture of a nation as a pattern of political attitudes that fosters democratic stability (Almond and Verba, 1963a, p. 232). These are attitudes toward the entire political system and how the individual perceives their participation in it. Political culture is a tool that fosters stability of the democratic system. It is a key component that leads to articulation of the political, social, and economic rights of individuals within the existing political system. An environment that fosters the right political culture is important in improving the perceptions and participation of individuals of low social classes. Therefore, as Dalton (2005, p. 150) notes, the reforms that are made in the political system are not needed to change citizens' negative attitude toward government. Instead, they should improve the democratic process. This will make the system more inclusive and participatory for the more vulnerable classes in society.

Citizens participate in government because they want to influence the government to meet their needs, support their priorities and protect their rights. Direct engagement with government bodies is one of the ways in which citizens interact with governments (Satterthwaite et al., 2007, p. 274). This form of citizen participation has the capacity to improve peoples' lives. It can reduce the immediate causes of poverty and the factors that perpetuate them. It can also contribute to better resource allocation and utilization. There is also an avenue to make representative democracy more accountable to lower income groups. In informal settlements in developing economies, few of the poor's physical needs are met. Representative democracy has done little for poor living in informal settlements (Cornwall, 2006, p. 73). Issues with the quality of housing, water supply, electricity, food, healthcare, and education are of great concern. If most citizens have their physical needs met and their civil rights protected, then society is more likely to be content with representative democracy. Deprivations by the urban poor are experienced locally (Satterthwaite et al., 2007, p. 275; Satterthwaite et al., 2011, p. 4). These local deprivations will not be addressed by external sources; there must be changes in the system of local governance to increase the power of the needs of those whose needs have not been adequately met. In many urban centers the proportion of the population facing such deprivation is also greatly influenced by the extent to which local governments and local institutions act to ease the cost of living. They also develop the capacity to provide certain key services that are available to all, independent of their income.

The extent to which the national government can support the development of stronger local institutions is an important aspect of its mandate (Cornwall, 2006, p. 74). These are institutions that deliver for those with limited incomes and are accountable to them. This means not only providing basic services but also to protect civil, political, and resource-using rights, enforcing the rule of law to shield the poor from powerful vested interests; to strengthen and secure land tenure on which people build their homes in informal settlements. Participatory government emphasizes the inclusion of marginalized people in conventional governance. It also implies the introduction or strengthening of mechanisms to encourage direct involvement of those who find it difficult to participate in state structures and processes (Kabeer, 2002, p. 33). It also implies an arena of action that goes beyond a specific project and involves government engagement with civil society groups. It is the inclusion of people and their interests which tend to get marginalized in representative democracy.

The interest in participatory governance is based on the need to extend the work on poverty beyond income and consumption and to pivot instead, to civil, social, and political rights. Governance is a concept that recognizes that power also exists outside the formal authorities and institutions of government. It is the construction of new relationships between citizens and their governments. Governance is defined as a concept that covers the institutions and processes; both formal and informal, which provide for the interaction of the state with a range of other stakeholders affected by the activities of government. It includes a larger group of actors: institutions and organizations that influence the processes of governance. Participatory governance means that there is a scope for participation between citizens and government. Participatory governance seeks to make government more inclusive and more effective in poverty reduction in informal settlements. With greater participation, communication, and influence from groups of the poor, state policies and practices are set to improve. It also offers a greater scope for action by organized civil society groups to show the importance of citizen movements. It may be an avenue for governments to increase their legitimacy by regaining citizen confidence by offering inclusive decision making.

The “Mukuru Belt” of informal settlements consists of Mukuru Kayaba, Mukuru kwa Njenga, Mukuru kwa Reuben, and Viwandani. The study looked at the informal settlement of Kayaba, kwa Ruben, and kwa Njenga, three of the four quadrants of the belt. All three slums are a part of the County of Nairobi, and slum dwellings are easily identifiable on Google Earth by density and corrugated tin rooftops. Mukuru Kayaba is in the sub-county of Starehe, population 210,423 (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2010), the majority if not all living in the slum (Google Earth, 2023). Mukuru kwa Ruben spans across two of Nairobi's sub-counties; (1) Makadara, population 189,536, and (2) Embakasi, population 988,808 (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), 2020). Disaggregated, the kwa Ruben slum population is roughly 150,000. Mukuru kwa Njenga is mostly in the subcounty of Embakasi, disaggregated to ~450,000 slum residents. The entire Mukuru slum has an estimated population of 527,526–700,000 people (about half the population of Hawaii) living in 193,539 households and occupying 52.5 sq., km of land (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2010). Some calculate up to 825,000 residents living in the slum of Mukuru (Pashayan, 2023, p. 3) based on analysis of satellite images from Google Earth.

The most current Kenyan Census conducted in 2019 shows an increase in population (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, 2010). Sixty percent of the inhabitants earn <10,000 shillings per month ($67USD/month), ~$1.90 or less per day inconsistently. Some live on 0.50 cents per person in a household per day and live on <½ a dollar per person per day (Save the Children, 2003). The poorest earn <5,000 shillings per month, about $USD33/month (World Bank, 2022). This area was selected for the study because it is close to the Industrial Area, which acts as a job–seeking hub for the casual laborers in this area. This study site witnesses higher interaction between the subaltern communities and the local administrators in the form of assistant county commissioners, chiefs, and assistant chiefs. There is also a clear indication that due to the existing poverty and lack of basic amenities, the locals rely on the government as well as non-governmental organizations for subsistence.

According to O'Leary (2010, p. 161), the target population is “…the total membership of a defined class of people, objects or events.” The target population of this study was the population of the Mukuru Kayaba, kwa Ruben, and kwa Njenga. Therefore, the unit of analysis were the individuals who inhabit this locale. In this case, these are adults both male and female who are 18 years and above.

Knowing that a sample is a subset of the population, the research objectives and characteristics of the study population were used to determine which and how many participants to select (Mack et al., 2005, p. 21). This study follows purposive sampling to investigate the phenomenon under study. Peoples (2021, p. 49) argue that in the case of transcendental phenomenology which seeks to describe lived experiences, research saturation can be typically attained with two to 10 participants. Creswell and Creswell (2018, p. 10) recommends that a phenomenological study should involve long interviews with up to 30 participants. This view is further buttressed by Mack et al. (2005, p. 20) who argue that sample sizes are also determined by the point of theoretical saturation which is the point at which new data no longer provides additional insights to the research questions.

Participants for insights on political trust were from the population of Mukuru Kayaba. A sample of 30 individuals were purposively selected was based on meeting criteriaa and snowball sampling. As a frequent academic visitor to the community, no research assistants were needed for the sample. Visiting four central locations within the slum, predetermined criteria (Patton, 2001) consisted of one key criterion that qualified participants for further interview: (1) Have you lived in the area within the past year? If the predetermined criterion was met, a nearby outdoor space was used for an open-ended interview with prompts on political trust. In general, demographics were collected, and questions were posed such as:

1) “Do you trust your government,” and

2) “What was your experience with government during COVID-19?”

In terms of Gender, it was easier to access female participants. This could be attributed to the commonality of females running small businesses in the community where they live. Other participants were community health volunteers who play a key role in informal settlements as mobilisers of various initiatives, including snowball sampling for research.

Ethical considerations of researcher acceptance outweighed notions of researcher bias. Being a female Kenyan with the ability to speak in English and Kiswahili provided an ethos of favorable reception. After explaining that no personal identifiers would be kept, informed consents were explained and signed. The data was collected by hand notes and transferred to a spread sheet. Interviews continued over the course of 1 week. Table 2 is a descriptive representation of the Mukuru Kayaba sample. It captures participant gender, age, occupation, and the number of years they have lived in the settlement.

The sample population from Mukuru kwa Ruben and kwa Njenga were 250 male and 250 female participants (N500), with question on political participation and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the health risks of proximity during COVID-19, a computer aided approach was used to ask 33 questions in open-ended, Likert scale, multiple choice and rating scale format using e-tablets and mobile phones. Participants were administered surveys at the well-known community hub, the Ruben Center, in coordination with the centers administrative staff who acted as support to four key Research Assistants.

The assistants were selected based on knowledge of socio-political issues in Mukuru, ability to speak English and Kiswahili, age of adulthood, respect from the local community, and gender (two female, two male). Each assistant was trained over a period of 5 days on how to use a mobile phone data collection application, provided to them free of charge. One of the 5 days was used for collecting and submitting test data. Another day was used to practice reading and explaining the informed consent.

Demographic questions (age, place of residence, and daily earnings) helped to qualify the respondents in terms of being over the age of 18 and living in Mukuru slums. No personal identifiers were a part of the survey. In addition to collection of quantitative survey data, a dialog box for qualitative answers was offered for questions that may provoke participants toward expanded answers. The survey asked many questions related to poverty and development, however the data shared in this paper is related to political trust during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To ensure the quality of the data, we relied on the integration of data is quality-assured based a systematic method derived from the statement of the problem as the guiding developed by the researcher (Maxwell, 2005). Data collection tools were pre–tested by piloting to ensure the study addresses the problem being analyzed, and the research procedures were reproducible (Yin, 2003; Rudestam and Newton, 2007).

Table 3 is a descriptive representation of the N500 sample based on age range in comparison to the overall population as per the Nairobi, Kenya Census 2020.

The qualitative study was carried out in 2019/2020 following approvals from the National Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI). The quantitative study was carried out in 2020, following approvals from the Institutional Review Board at Howard University in Washington, DC. The researcher further obtained clearance from the National and County Government through the offices of the County Commissioner, County Education Office and the Area Chief in Mukuru Kayaba. Piloting of the study was carried out in the informal settlement of Tetra Pak to clarify that the study parameters were sufficient to proceed to the actual study site. Informed consent included the explanation of their rights including the right to abandon the interview at any time without consequences.

The study generated data in the form of documents, interview transcripts and focus group discussion transcripts, qualitative answers, and empirical data. This study adopted the categorizing strategies of key themes that developed in the data. Coding and thematic analysis were applied. Meanings were formulated using clusters of emergent themes. The coding included division of demographic categories i.e., age over 45 (code 1), age under 45 (code 2). Other variables such as gender, years lived in the slums, and political participation in the most recent election were also ascribed code 1 or code 2 for simplicity. All interviews were coded manually. Saldana (2009) defines a code as a word or a short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence-capturing and evocative attribute for a portion of language-based or visual data. This type of coding was used for qualitative questions that prescribed symbolism. for easier data analysis (Owen, 2013). From verbatim transcripts, 73 significant codes were derived. The first cycle coding used narrative coding to look at the verbatim transcripts. After which, the codes were categorized to generate categories based on the underlying meanings generated from the interviews. Clusters of meaning were formed by grouping together leading to the emergent themes (Saldana, 2016).

Using qualitative methodology and quantitative data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mukuru, the paper raises questions of political trust and interactions with local government during the COVID-19 pandemic. It problematizes the concerns of the subaltern, their place and knowledge as perceived by their interactions with local administration and the national government. The main findings illustrate the callousness of government during the pandemic leading to tensions with activists and the residents of Mukuru. The relevance of this work is Kenya's decline in political trust and increased precariousness of local and national politics.

For the purposes of this study, two main themes were relevant:

1) Citizenship and Public Trust, and

2) Apathy and Exclusion.

These themes from data analysis highlight the most powerful perceptions of the study participants at the height of COVID-19 restrictions in their community.

The lived experiences of the study participants as citizens living in informal settlements are problematic. They are bounded by a lack of agency; in that, the individuals and the community do not know how and when to exercise their rights as citizens (Lister, 2003, p. 20). Their agency is diminished because it is confined to being expressed by voting only. They opined that even with voting, there is little improvement in their livelihoods. The representatives they elect exclude them by failing to engage with them directly, preferring to use agents. The study participants expressed the fact that their views were not taken seriously by their leaders; they may listen to them at the barazas but fail to act on their input (Moore and Putzel, 1999, p. 15). This leaves the community with the perception that their views are not important. Joseph1 explained that:

“…the first thing is that they lack voice and they can attend public participation and when they speak, they are asked to select two or three people to speak on their behalf…but those who are chosen do not follow up because each one of them has their own personal daily activities, so at the end of the day or the year, nothing happens to what they discussed.”

Jane, a female CHV (Community Health Volunteer), says that:

“Citizen participation is beneficial because they [the community] can understand themselves …but they don't have a lot of power …powers to act are what they do not have a lot of …because they have been captured mostly in the village …those powers have been taken over by the village elders and the Chief… Now, in the way that when they call for a meeting, they call for barazas…the Chief's baraza …then they create a …then people can discuss in the open forums…they talk. You see, the more they talk, the more it becomes beneficial…it widens peoples' minds…a person is able to know their rights…they know that if I do this, maybe it is not a mistake.”

Hezekiah also finds that there is strength in number because:

“Voice to people requires that…we look at the number of people that live in a certain area …how many are they? Because this is what will give them a voice …. not the kind of noise that they can make on the streets …if you find that a certain area has many people …that is the voice they have they have that will affect anything they get from the government.”

The study participants expressed their lived experiences of viewing representation as an avenue of agency in their community (Fung and Wright, 2001, p. 10). It is an often underutilized path to gain communal and individual agency. Joseph also stated:

“…empowerment is very important and it is what is making the community lag behind …if public participation was present there would have been empowerment…people would get…the youth, even women will get the information about access, like the women fund, the youth fund…but you find that we have very many young people here…there are those who have moved a bit higher like the youth in other areas in Buruburu and other areas who have accessed public participation.”

They opined that if they choose their own leaders directly, especially the chairpersons, and the chief, they will select locals of integrity who understood their needs and had the local social networks to address them by accounting for local nuances (Barnes, 1999, p. 75; Geffen, 2001, p. 2). Although the Constitution of Kenya (2010, p. 24) guarantees a “new” bundle of rights- social, political, economic-the study participants expressed their views that politics of the day, the allocative function affects the availability of certain assistance. The views of Joseph and Alex, respectively are that,

“…awareness…people should be made aware; it should be explained to them. Public participation should be explained to them without any representation or any other people interfering in the process…”

“…their rights are still low, they don't have it really in their hands…for many of them, their understanding is still low…they don't understand and that is why sometimes we do (sic) wrong elections.”

Miriam explains the importance of their participation as citizens:

“…like the meetings they usually call us for in Starehe, when we go there, they don't know where each one of us is coming from …once they open the meeting, it is up to us to open up and speak about the places where we have come from, so that they will know that people from a certain place have attended the meeting…so it is necessary that we attend and represent…and there are no restrictions…we are all free to speak.”

Associations and relationships between gatekeepers who are the chairpersons, and chiefs are well-connected individuals who will affect the ability of ordinary citizens to get assistance they need. It may require that they liaise with certain individuals to access the assistance they need (Escobar, 1995, p. 23). This introduces issues of corruption, bribery, and nepotism. Wycliffe explains that:

“…these days, it looks like you need to bribe the chairman, then you bribe another one and then you go to the chief…you find that somebody can give up along the way.”

“If people hear about an empowerment programme that is originating from the chief's office, you just know that it is full of corruption …in your mind you know it is corrupt …you need to look for some money …then I will get it …I must have some money before I can access it.”

From the empirical data of N500, 30% view “bad governance” as a contributor to their own poverty, with 9% adding tribalism to the category. A higher percentage (52%) site corruption as a key factor of poverty, inclusive of political corruption. The responses point to government-imposed oppression, reduction of the ability to get ahead financially, and lack of good political leadership. Some of the expressions of respondents on causes of setbacks were:

“Corruption based on tribalism and tribalism.”

“Bribery to get jobs.”

“Corruption and bad governance.”

“Bribery made word during coronavirus.”

“Bad politics, corruption, and unemployment.”

Loss of public trust is a major lived experience for people living in informal settlements. Many of the study participants expressed their frustration with their service to the local community (Almond and Verba, 1963b, p. 215; Dalton, 2005, p. 150; Muungano wa Wanavijiji, 2021, p. 1); Alex says that:

“…you understand the chiefs don't like doing it, they only do it when it comes up as a security matter, only when things become bad do they call for a meeting.”

Together with other leaders, they have superficial reach and interaction with the locals. The study participants expressed the view that there are interior areas of the informal settlement that get little attention from their leaders (Roy, 2005; Roy, 2011, p. 225; Lindell and Ampaire, 2016, p. 258); John who has lived in Mukuru Kayaba for over 25 years opines that:

“…the leaders just move on the main roads and claim that they have reached the locals, but they have not gone into the interior to see…passing on the main roads is not the way to reach the local peoples…”

This means that conditions in those areas are worse off than in other areas. There is also a perception of distrust in their welfare from their leaders (Gaventa, 2006, p. 26; Yiftachel, 2009, p. 90). This was strongly expressed by female participants of the study who are CHVs as they spoke of the need for ARVs, cancer medication, contraception, and the distribution of jobs to “outsiders” (Morange and Spire, 2019, p. 14); Anne who is a CHV in Mariguini village explains how preferential treatment and local politics hurts the community:

“…even the way those ARVs [got here] …the foreigners said that they would not bring them, but when they came and had a meeting, that is when the medication started to flow again …we saw that people were receiving help.”

Rose, a local primary school teacher expresses the same frustration.

“…you can even get that it is a whole family that is getting access…a whole family and the other members of the community are just left wondering” Christopher, a university student who has had to defer his studies says that: “I can back him a bit…the issuing of bursaries here in Nairobi South, when you go to the chief's (office) the same people you find denying your application will serve in that office for years and that person lives with you here …and then 1 day you have a disagreement …a small one …and then you try and go for a bursary there …do you think that guy will give it to you? He will say ‘that woman was rude to me.”'

From the empirical study (N500), 93% of the respondents confirmed they voted in the 2022 Kenya Presidential Election, yet the lack of political trust is compounded by mistrust of other outsiders connected to government:

“It takes more time to achieve things, this is because the government and other NGOs bring programs for [us] but do not consult the people.”

“They bring projects [that are] not relevant to the needs of the people” “The government is not doing enough, and our problems are passed from on government to another. They come during elections to ask for votes, thereafter they go never to come back for any meaningful development.”

When asked why they voted, 86.6% of the respondents answered, “I want things to change.” A lesser percent (9.8%) answered “everyone votes,” and 5.6% answered, “I want my tribe to stay in power.” This indicates that slum residents of Mukuru are looking for political change regardless of tribal affiliation. A total of 57% acknowledged that their government provides them with fresh water, yet 98.4% believe their government has funds to help them but chooses not to help them. And 28.6% believe their government does not care at all about them, that they are being used to gain aid funds that never reach them:

“Most of the time the money intended for poverty reduction in the slum end up being used for other things by the leaders (stolen) or because of corruption only little is left available for use to benefit the community.”

“These programs are surrounded by corrupt individuals, especially the leadership who are the first people to know about such programs. They determine who is to benefit.”

“Benefits go to family members and friends of organizations leaders, or people who bribe to be put on the list of beneficiaries.”

For many, the idea of corruption at such a level is abhorrent. For Mukuru residents it is an everyday occurrence that leads to political distrust. Considering that only 57% acknowledge that their government provides them with fresh water lends itself beyond political distrust, to a violation of human rights.

Information, which is necessary for communal and personal decision making, is also at a high premium. It is only dispensed to a few select people. It may trickle down to a few members of the community, increasing levels of exclusion and distrust (Davis, 2004, p. 8; Benjamin, 2008, p. 723; Morange and Spire, 2019, p. 14); Rose adds that:

“…you need to get someone who already knows what people need in the area. You cannot bring an activity that will not do well at that time…you go around and speak to the women…and because you live in that community you are amongst them, and you would know what they need.”

Elsa explains that accessing information on projects:

“…it is difficult…that one about the accessing of certain projects in the village is hard because the people you link up with …there must be confrontation…before you can get what you want.”

There is also a feeling of entitlement to compensation expressed by the study participants. They opine that the locals should be compensated for attending citizen/public participation barazas. This is because many of them are day laborers who wish to be paid for the time spent attending barazas (Cornwall and Gaventa, 2001, p. 4; Cornwall, 2002, p. 4). This is made worse by the fact that they perceive no tangible benefits from citizen/public participation. They opine that there are no visible outcomes of positive impact that enable people to value it. They perceive that external agendas and solutions are implemented which makes it difficult for the community to embrace the inputs and outputs of citizen/public participation as driven by their leaders (Davis, 2004, p. 8; Roy, 2011, p. 225); Joseph says:

“…but representation is where one stands in the gap to represent in [public] participation, they can bring water here, construct drainage and maybe I didn't want it or you do certain things that I do not want …that other people do not want, but when we come together in public participation own the issue and we can own the project”

Janet, who runs a small food business says:

“…If you look for a representative and you find them, they want a bribe…and, maybe that bribe, you do not have it, so that means you have to stay where you are …for example, like me…I have a husband but he is jobless…he does not have a job at all …so it means that I have no choice but to struggle and sell my githeri…to pay rent and other needs…and you know there, that business is not adequate to meet our needs of the house and as well as the needs for food I have to also leave and go to look for casual employment …maybe doing laundry …so that it can assist me a little bit.”

Christine, a student also adds on that:

“…someone like the MCA, you can tell them something here and then when they move ahead, they have forgotten and their focus has moved on to other things... and then a person like the Chief… he judges the person who is sending the message …let's say that you are just an ordinary person, he will tell that person that he will act on it so that he/she will go but he/she will not act on it.”

Jane, who is a CHV and is part of the team that runs the local women's water project says:

“ …you know participation of the local people living in the village, they feel like if they are gathered in one place for a participating exercise, they know that there is a stipend there… so most of the time, they do not want because… most of the people live here take part in informal employment especially odd jobs …now many of them are thinking about what they would gain from going for that exercise …and waste their time and they could be sitting at their kiosk and selling their wares (vegetables) to at least one person and they get at least Ksh 5 (kobole-slang)to buy paraffin to use in the evening, to buy something like soap to wash the children's clothes…it is not easy.”

Accessibility also affects the availability of public goods. For instance, the provision of water through the use of the water token is difficult because of the initial costs of setting up the service (Yiftachel and Yacobi, 2003, p. 677; Yiftachel, 2009, p. 89). This acts as a barrier to its uptake by most of the people. Also, the study participants lamented the long distances that would not allow them to access this cheaper water point. Instead, many rely on water points closer to them that sell water at higher prices. The costs of the project affect its expansion to other areas of the settlement. As expressed by the study participant, Hannah, the interests of various gatekeepers who may be owners of similar businesses have a role in stifling the expansion of the business:

“…honestly, those offices do not help ordinary citizens unless you have something to offer…” Jane adds that:

“…on your own you see an opportunity and you feel it is the right place for you to set up a kiosk to sell vegetables so that you can get your daily basic needs…that kiosk will be pulled down …unless you enquire from the village elders…and the Chiefs and then maybe they will give you the permission, they give you that portion…if they give you that portion, there is a way that you have to pay for it …there is something small that you have to pay so that you can be allocated that space…so empowerment here in the village is usually difficult because most of the time it is the Chief and the village elders that take control.”

As Christopher reiterates,

“…there is nowhere that you will go and find a straightforward process that will assist you and then it can also assist the community …all of them are corrupt…”

Esther explains that:

“These government bursaries...the chiefs and the chairmen will take them …the one who really needs them will not get them unless you go to the chief and give a bribe, then you can get it …or to the chairman who will come and offer a bribe on your behalf so that you can get it.”

Another theme that emerged from the data generated in this study was that of perceptions of exclusion and apathy toward citizen/public participation in informal settlements. Most of the participants expressed that in their experience their exclusion had led to apathy of the informal settlement communities. For instance, Joseph stated:

“…but that public participation, many times you will find out with surprise that something has started or has been agreed upon …you will find out that they have agreed between two or three people.”

Alfred also explains that:

“As we have said, there is citizen participation but people are tired of attending because even if you do attend, your ideas will not be used …also you can affect your CV (reputation) when you want to access something in the future …people take it positively and people know about it …”

A lack of continuous civic education has led to a lack of awareness and understanding of what civic/public participation is. In the interviews, out of the 30 participants interviewed, I found that more than half of them expressed their exclusion from crucial meetings (Cornwall, 2002, p. 5). The levels of exclusion are evident in the expressions such as that of Alice who stated that:

“…we usually hear about public participation, but it has never reached us.”

They opined that the meetings to discuss crucial issues were only limited to a certain group of individuals (Lefebvre, 1991, p. 28). This has led to the perception that the views of local people do not matter. The fact that public administrators only called for barazas to inform people on issues pertaining to flooding, water, public health, and disaster management does not present opportunities to provide clear information about citizen/public participation. Esther says that:

“…there are meetings but mostly it is amongst themselves, but for an ordinary citizen, it is not easy to be included …the Chief, the chairman, they just hold their own meetings, by the time an ordinary citizen is able to access such a meeting, it might be too late.”

A lack of continuous awareness creation means a generational gap between passing knowledge on citizen/public participation (Urban Areas and Cities (Amendment) Act, 2019, p. 369). As quoted from the views of one of the study participants, Hezekiah:

“… in the past we had an organization that used to create awareness…it was called GOAL. They are the ones who used to create awareness like what we should do so that when we go to the meeting …the baraza…they used to create awareness about public participation so that when you go to the baraza you can contribute. It is now more than 15 years since they closed their office.”

The passing of this key knowledge from one generation to another is disrupted. There is therefore a lack of a communal push for local development. Perceptions of apathy and exclusion are compounded when there is reluctance to speak in barazas (Habermas, 1989, p. 18). As Habermas (1989, p. 19) postulates, the public sphere is captured making exclusion evident. Elections are perceived as the only sites for exercising citizenship and participatory rights. This limits the agency of individuals and communities making them susceptible to the influences of the agendas of politicians (Moore and Putzel, 1999, p. 14). As their leaders, the politicians are unaccountable in the way that they disburse and utilize development funds. Many of the participants expressed their frustration with how these leaders, especially the Chairpersons, MCAs and MPs carry out their mandate with limited input from the local community. This quote is an example of their views as opined by Alice, who is a community health volunteer (CHV):

“…our MP has disappeared, and he cannot be found. He does not even pick our calls.”

Wycliffe further explains that:

“…but the other type of representation is where there is a go-between …you have somebody who accesses and brings those things…but this relationship is where you must exchange something…but a normal representation is a reciprocal relationship.”

Empirical data that explored top issues during COVID-19 reveal that hunger, lack of income, and lack of commerce (ability to earn income) were critical (Table 4). These issues are related to the lack of responsibility the government has for Mukuru residents. Hunger, along with the other issues in Table 4 can be linked with a derelict of managing basic needs for citizens.

Out of 500 respondents, 436 went hungry during the pandemic due to the government failure to provide adequate services in informal settlements, making another negative impact on political trust. In a final question, respondents were asked if they wished to add anything else to their survey answers. The word “government” had the highest frequency of mentions, with all other words having frequencies of 9% or less.

Exclusion in informal settlements emerges as a key theme in the process of documentary analysis (Urban Areas and Cities (Amendment) Act, 2019, p. 369; Kenya School of Government, 2015, p. 3). This is because the documents analyzed give instances of the exclusion of the communities in several ways. First, by highlighting geographical exclusion; the sites of these communities are always located on sub-prime, government and contested lands. The lack of the most basic amenities on these settlements serves as a sign of the depth of their exclusion. Geographic and service exclusion is the basis of the key representations of the communities. These communities are marginalized in terms of the policies and practices of urbanization (Intergovernmental Relations Technical Committee, 2019, p. 9). The arbitrary nature of their construction and their livelihoods further compound their peripheral location in society. Although the type of housing has evolved to more permanent structures, fundamental issues in the land tenure system exacerbate the precarious circumstances of all the main stakeholders of these settlements. The existence of policies that address vulnerabilities have had minimal impact on informal settlements because of their conflated context. What people fail to understand is that informal settlements provide important services to more formalized arrangements of urban areas (Mahabir et al., 2016, p. 403).

This research brings to the fore the need to understand the meanings and the role of citizen participation and public trust. The stakeholders need to know when and how to exercise their rights as citizens (Cornwall and Gaventa, 2001, p. 4). There is also a need to empower the youth as future mobilisers of change in informal settlements. As citizens, people need to highlight the fact that representation is a viable and valuable way in which citizens can see the rights as “makers and shapers” come alive for their families and communities. The lack of public trust is a key theme as voiced by the lived experiences of informal settlement communities. This is because they did not trust the government officials. This is because there are superficial interactions with their leaders. They also expressed that they had a limited reach into the community. Both factors meant there was limited impact of any of their development impacts due to the lack of public trust. Many of the study participants expressed that in their view, it was necessary to incentivize citizen participation engagements. The explanation was that it was a way of compensating many of the locals who are casual laborers and always felt that it was a waste of time to attend these barazas. However, their idea of incentivizing citizen participation is problematic in practice because it denotes the wrong premise for community involvement. Monetary or in-kind compensation does not give the community the agency it requires to dialogue with external stakeholders. The local community needs to find and perceive value for money in citizen participation.

Apathy and exclusion are key themes highlighted by both interviews and document analysis. In subaltern studies, explain the peripheral position of informal settlement communities. Antonio Gramsci coined the term subaltern to explain the concept of subordination and inferiority of the poor and vulnerable people in society. It explains the geographical, political, and social exclusion of subaltern communities echoed in this research's findings. Guha and Spivak who also write on Subalternity point to marginalized groups in society, the poor, women and the disabled. The findings of the themes of apathy and exclusion in both interviews and document analysis are consistent with the literature on citizen participation at the local level. Cornwall (2002, p. 26) illustrates how the spaces created/invited for citizenship are bounded by both inclusionary and exclusionary tendencies that affect the participation of subaltern communities. The perception and reality of living and practicing their citizenship on the periphery reflects the positionality of individuals and their community. The findings of the theme of apathy and exclusion in both the interviews and document analysis are consistent with the literature on citizenship studies. Dalton (2005, p. 150) opines that changing expectations of citizenship rather than government failure are the reasons why there is an increase in apathy and exclusion amongst citizens especially those living in informal settlements. Almond and Verba (1963a, p. 402) also postulate that if a political culture were to develop, then there would be development and empowerment of a democratic process. However, for a citizen to become an active citizen, there needs to be perceptions that enable them to take up that place as active citizens who actively engage and take part in the life of the communities.

The meanings and practices of citizenship illustrate the problematic relationship between the essence of citizenship and the practice of citizen participation. This is consistent with literature from scholars such as Mamdani (1996, p. 18) who articulate the dual nature of the African as both a citizen and a subject. This dichotomy is evident in Intergovernmental Relations Technical Committee (2019, p. 33) who describes citizenship as both a status and a practice. Cornwall (2002, p. 24) highlights the problems with the practice and meanings of citizenship especially for vulnerable communities such as the informal settlement communities. Citizenship as a theme is conceptualized because of the nature of the emergence of the meanings and practices of citizenship that by their very nature tied to the emergence of the nation-state, which is a Western concept. This means that most of the people living in the informal settlements have little attachment to the practice of citizenship because it has yet to find full expression in their lived experiences as a marginalized community. Although citizenship has connotations of exclusion and inclusion bound in the definitions, the struggle for recognition of marginalized societies is affected by how people experience these issues which are at the periphery of most governmental concerns.

Loss of public trust is depicted in the literature on the spatial dimensions of citizen participation (Lefebvre, 1991, p. 26) and the infiltration of the public sphere by government officials (Habermas, 1989, p. 21). Communities lose trust in the administrators of the system and the system itself because it does not account for the needs of those it purports it was designed to assist. The findings of the research highlight the disillusionment of individuals and communities with the officials, systems and processes that govern citizen publication. The spaces for citizen participation are affected by a lack of nuance and context of local communities to improve the adoption and effectiveness of policy changes and acceptance by communities. The loss of public trust as a theme is consistent with studies on participation by scholars such as Lefebvre (1991, p. 25) who opines that these ‘new' spaces reflect the old spaces. They may sometimes be used to limit the poor. The study participants said that opening these spaces may not be viewed as an improvement. Cornwall (2002, p. 27) notes that inequalities of the past are often reproduced in the spaces of participation. This is because the act of space making is an act of power. As Lefebvre (1991, p. 24) explains that those who make up and fill these spaces are positioned actors. These are actors who may act as gate keepers and set the agenda for engagement in those spaces. Habermas, the pioneer of the theory of public space expounds on the differences in what people consider as important or meeting community interests. Colored by the meanings and practices of citizenship as a theme that carries the vestiges of the past. Because of the historical basis of the concept of citizenship, it means that implicitly, there are boundaries for the marginalized communities.

As Colantonio (2009, p. 8) opines, which is consistent with the findings of the study, empowerment, participation, and access are some of the subthemes linked to citizenship. Through these concepts, citizenship finds its expression in the lives of subaltern communities living on the periphery. The study participants also expressed their frustration with how to understand and practice their citizenship considering the new realities as expressed through the extended bundle of rights—social, political, economic, and cultural. The citizen living in the informal settlement faces many challenges compared to those who live in more formalized arrangements. Their lived experiences as citizens are made even more difficult as they expressed by the difficulty in expressing themselves as citizens with all the rights due to the individual. Social sustainability studies research emphasizes the loss of public trust, which is a research theme. By incorporating social equity and justice so that urban informal settlements can be suitable places to live. This is consistent with the findings of the study where these concepts of social equity and justice are important for social sustainability of informal settlements. The contestations of power as a theme in terms of the social sustainability of informal settlements in terms of the lived experiences of subaltern communities who want to participate are unable to do so.

From the findings of the research, there is a lack of provision for the practice of citizen participation in informal settlement communities and other poor communities (Muungano wa Wanavijiji, 2021, p. 2). What exists is a conflation of the provisions of citizen participation into opportunities and resources available for all the citizens of a nation (Urban Areas and Cities (Amendment) Act, 2019, p. 370–372). They fail to consider that context and nuance in informal settlements impact the direction, context, and priorities of citizen participation in informal settlements. Apathy and exclusion in the context of subaltern communities is a serious deterrent Apathy means that in informal settlements, people are disillusioned by how they are unable to access, interpret and utilize the existing provisions for citizen participation (Cornwall and Gaventa, 2001, p. 10). It shows that individuals are not able to participate as citizens, and this exacerbates their exclusion. Exclusion then takes various forms that further disenfranchises the poor and vulnerable (Das and Espinoza, 2020, p. 22). Apathy and exclusion in Mukuru Kayaba mean that people rarely attend barazas and other community meetings. In their estimation, the costs of citizen participation far outweigh any perceived benefits. People would rather find other ways of constructively using their time instead of sitting through the proceedings of a baraza that ignores and sidelines their contributions (Bayat, 2007, p. 10).

Citizenship and public trust go hand in hand because the study shows that in subaltern communities, the concept of citizenship is affected by the realities on the ground (Isin and Turner, 2000). It is the effect on citizenship that leads to a loss of public trust. The idea of citizenship presupposes all citizens of a country experience it the same way (Aiyar, 2010, p. 211). However, studies have shown that there is always a differentiation in the perceptions and practices of citizenship (Lister, 2003, p. 10). The exclusion of place, policy and lived experiences means that subaltern communities are affected in ways that their power of their citizenship is diminished by their circumstances (Lefebvre, 1991, p. 24). All participants expressed their dissatisfaction with their citizenship, which is not in line with the letter and the spirit of the new dispensation of the constitution. The extended bundle of rights as articulated in the Bill of Rights, Article 19(2) of the Constitution of Kenya (2010, p. 16) seeks to ensure Kenyans from all levels of society live life to the highest standards possible. However, socioeconomic, and political realities make it difficult to experience this ideal.

From this research, exclusion is a clearly identified theme affecting informal settlement communities. Exclusion is an issue that affects the quality of life of these settlements. This may be geographic, material and policy exclusion; in the sense that their location is far removed from the built-up of the area causing them to be affected by a lack of access to basic human amenities. Secondly, material exclusion is reflected through the lack of physical assets required for socially sustainable development. Policy exclusion is also depicted by a lack of political will and expediency to pass Bills that would improve the practice of citizen participation in informal settlement communities. The peripheral position of the informal settlement communities is depicted by the perceptions of apathy and exclusion in the functioning of their citizenship.

The meaning of their citizenship and its practice is bound by their interactions with leaders and public administrators. A loss of public trust is evidenced by their expressions of a reluctance to fully utilize the baraza as a space for public participation. The baraza, bound by colonial vestiges, acts both as an opportunity and a constraint on public participation and social sustainability of their community. As citizens, people need to highlight the fact that representation is a viable and valuable way in which citizens can see the rights as “makers and shapers” come alive for their families and communities. The lack of public trust is a key theme as voiced by the lived experiences of informal settlement communities. This is because they did not trust the government officials. This is because there are superficial interactions with their leaders. They also expressed that they had a limited reach into the community. Both factors meant there was limited impact of any of their development impacts due to the lack of public trust.

Many of the study participants expressed that it was necessary to incentivize citizen participation engagements. The explanation was that it was a way of compensating many of the locals who are casual laborers and always felt that it was a waste of time to attend these barazas. However, their idea of incentivizing citizen participation is problematic in practice because it denotes the wrong premise for community involvement. To reiterate, no monetary or in-kind compensation does not give the community the agency it requires to dialogue with external stakeholders. The local community needs to find and perceive value for money in citizen participation at local and national levels.

CONSIDERING political participation initiatives in the development sector, including theories of Michael Cernea, Putting People First (1985), Amartya Sen Development as Freedom (1999), Mahbub al Haq, Human Development Report (1992), David Korten and Rudi Klauss, People-Centered Development (1984), collaborative authors of “Shaping the twenty-first Century” (1996), published in the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) report of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

HAVING REGARD for people-centered development promotion at institutions inclusive of The Institute for Human Centered Design, the World Bank, USAID, House of Democracy, Human Restoration Project, and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

RECOGNIZING the dynamism of discourse on people's participation at international conferences such as the International conference on Population and Development (1994), the Summit for Social Development (1995), the UN Conference to create the Human Development Index (1990), the Wilson Center Conference Examining Democracy, Governance and Peacebuilding in Africa (2023), annual conferences of the International Public Policy Association and the Human Development Conference.

AFFIRMING the African continental support for political participation and human centered approaches at the Political Parties in Africa Conference (2018), the African Association of Political Science Biennial Conference (2023), the UN Africa Day—High-level Political Forum (2023), and the African Human Capital Heads of State Summit (2023).

We recommend the following polices be considered to improve political trust in Kenya:

1. Counter social exclusion of Nairobi's urban slum population with inclusive dialogue with government public officials on political issues that foster increased state support.

2. Prioritize socio-economic rights of slum dwellers, including health, education, food, housing, water, and emergency social security nets.

3. Facilitate political localization in communities through open dialog across vertical levels of power i.e., citizens, local leaders, chiefs, district officers, and government appointed officials, with written reports accessible to the public.

4. Implement meaningful engagement between political actors, social advocates, and slum residents for the purpose of building a political culture of trust.

5. Ensure that girls and boys have quality education on political participation based on issues that affect their daily lives.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by National Council for Science, Technology and Innovation and Howard University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

RM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. AP: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Tables and statistics.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for the publication of this journal article was provided by the American University, Washington, DC.

RM acknowledges Le Van for the opportunity to participate in this writing project as well as the introduction to AP, co-author of this journal article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^We use pseudonyms in this journal article to show that the participants names have been changed to protect their anonymity.

Aiyar, Y. (2010). Invited spaces, invited participation: effects of greater participation on accountability in service delivery. India Rev. 9, 204–229.

Almond, G. A., and Verba, S. (1963b). The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton University Press. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt183pnr2

Bagaka, O. (2011). Restructuring the provincial administration: An Insider's view. Constitution Working Paper Series No.3. Society for International Development, Nairobi. Available online at: https://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/the_provincial_administration-an_insiders_view-wp3.pdf (accessed May 20, 2023).

Barnes, M. (1999). Users as citizens: collective action and the local governance of welfare. Soc. Policy Administr. 33, 73–90. doi: 10.1111/1467-9515.00132

Bayat, A. (2007). The quiet encroachment of the ordinary Chimurenga, 8–15. Available online at: https://chimurengachronic.co.za/quiet-encroachment-of-the-ordinary-2/

Benjamin, S. (2008). Occupancy urbanism: radicalizing politics and economy beyond policy and programs. Int. J. Urban Regional Res. 32, 719–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00809.x

Citizen Digital (2022). President Ruto abolishes Kazi Mtaani Programme, says it's outdated. Available online at: https://www.citizen.digital/news/president-ruto-abolishes-kazi-mtaani-inurban-areas-n308112 (accessed October 20, 2022).