- Department of Psychology, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, United States

Introduction: Psychological factors linked to political participation are largely understudied in American Indians. Prior work notes relatively low levels of participation compared to other racial and ethnic groups and suggests that identification with being American Indian is linked to overall levels of civic engagement in part through perceptions of group discrimination.

Methods: In the current work, in a sample of 727 American Indian adults, we created two groups: Group 1 (N = 398) reported perceived discrimination related to race, and Group 2 (N = 329) reported perceived discrimination not related to race or ethnicity. We investigated the relationships between individual experiences of everyday discrimination related to race, levels of political efficacy, and political participation (Group 1), and individual experiences of everyday discrimination not related to race or ethnicity, political efficacy, and political participation (Group 2).

Results: We found that greater experiences of everyday discrimination related to race was associated with higher levels of political participation through increased levels of internal and collective efficacy. In contrast, greater experiences of everyday discrimination related to race was associated with higher levels of political participation through lower external political efficacy. For Group 2, we found that greater experiences of everyday discrimination not related to race or ethnicity was not directly associated with political participation, but mediation analyses revealed a relationship with lower levels of political participation through decreased internal and collective efficacy. The indirect effect through external political efficacy was not significant.

Discussion: Given low levels of American Indian political participation, political efficacy could be a target for interventions aiming to increase participation in the political system.

Introduction

Civic engagement, or individual and collective actions designed to identify and address public issues, is well-studied in the arena of political science. In this area of study, attention has been devoted to understanding and identifying motivators and barriers to civic engagement. One form of civic engagement is political participation, and there are a growing number of studies that focus specifically on differences in levels of political participation related to racial and ethnic identity (Min and Savage, 2014; Littenberg-Tobias and Cohen, 2016; Huyser et al., 2017). Generally, this literature indicates that racial and ethnic minorities have lower levels of political participation compared to non-Hispanic White people. However, the literature on American Indian political participation is relatively limited. Given that American Indians face persistent health inequities largely linked to historical trauma, cultural oppression, and continued systemic discrimination (Gone and Trimble, 2012; Thornton et al., 2016), identifying predictors of behaviors that are linked to positive health outcomes is imperative for this population. Increasing political participation among American Indians may be an important avenue to consider given recent findings that inequalities in political participation are associated with increased health disparities, even when controlling for factors such as poverty, rates of smoking, and other potential confounders (Reeves and Mackenbach, 2019). Identifying factors that motivate or deter political participation among American Indians is also necessary given the implications that participation has for American Indians, as well as the entirety of the democratic system.

Seminal research on American Indian political participation acknowledged that before European colonization, American Indian communities were governed by unique political structures overseen by members of their tribes. As a result, this body of work notes that American Indians are more likely to support candidates who are in tune with tribal issues and needs rather than voting based on cultural connections or political party affiliations (Huyser et al., 2017). In line with this, tribal endorsements can significantly influence voting patterns (Corntassel and Witmer, 1997) often driven by a desire to protect and defend their sovereignty (Kahn, 2013). Previous studies on American Indian political participation have largely focused on demographic factors including marital status, age, gender, household size, education, and veteran status. Extant work indicates that in non-congressional years, compared to non-Hispanic White people, American Indians have lower levels of political participation (Huyser et al., 2017). Ongoing barriers (e.g., long travel time to voting places, and photo identification requirements) likely contribute to relatively low levels of American Indian political participation (Sells, 2012). In addition, distinctions made in the broad American Indian population (e.g., tribal vs. urban, and Western-educated vs. traditional education) contribute to a lack of social cohesion which limits political mobilization.

For racial and ethnic minorities, the relationship between perceived discrimination and political participation is complex. For example, in Black youth, perceived institutional discrimination was positively related to levels of civic engagement (Hope and Jagers, 2014). It is posited that both an awareness of existing inequalities, as well as an understanding of why these inequalities exist can mobilize individuals and groups to engage civically and politically (Hope and Jagers, 2014). Similarly, ethnic minorities in Great Britain who experienced greater political discrimination (e.g., policies and practices used to take rights and resources) reported greater political participation (Oskooii, 2020). However, the relationship between experiences of societal discrimination (e.g., discriminatory acts such as intimidation, antagonism, etc. inflicted by another individual) and voting was not significant (Oskooii, 2020). One consideration regarding these findings is that political discrimination was measured as experiences of discrimination: “(1) when dealing with immigration or other government offices or officials, (2) when dealing with the police or courts, or (3) in domains such as colleges or universities or (4) when applying for a job or promotion” (Oskooii, 2020). While this measure of discrimination is related to more “political” settings, the act of discrimination could very well be interpersonal, and thus, arguably reflect a personal experience of discrimination. Nonetheless, this nuance speaks to the potential differential impact that the type of perceived discrimination (e.g., group vs. individual) may have on political participation. For example, when examining experiences of discrimination among Muslim Americans in the post-September 11, 2001 United States, a positive association was revealed between individuals' self-reported levels of anxiety, group discrimination (e.g., having friends and family who experienced discrimination), and political participation (Jalalzai, 2010). However, personal experiences of discrimination were unrelated to political participation (Jalalzai, 2010). Importantly, the author notes that “personal discrimination should not be discounted” (Jalalzai, 2010), based on previous findings that personal experiences of discrimination can increase perceptions of group discrimination, but not the other way around (Taylor et al., 1991). In line with this, studies have shown that experiences of interpersonal discrimination such as microaggressions were associated with increased civic engagement in Black college students (White-Johnson, 2012). It is important to note that various factors may influence an individual's perceptions of discrimination. For example, in a study on American Indian adults, a strong sense of identity as a Native American was associated with greater recognition of omission of their group from society, greater perceived group discrimination, and ultimately greater levels of civic engagement, including participation in political activities (Dai et al., 2023).

A psychological factor that may influence levels of American Indian political participation is political efficacy, or “the feeling that political and social change are possible, and that the individual citizen can play a part in bringing about this change” (Campbell et al., 1954, p. 187). In this way, efficacy can be viewed as a cognitive resource that reduces barriers to participation, thereby promoting engagement. Political efficacy includes internal efficacy, or an individual's self-perception of their capability to participate in political processes, and external efficacy, which reflects the degree to which individuals feel they have a say in what the government does and the degree to which they feel the government is responsive to citizens' demands, and collective efficacy which refers to an individual's belief in the abilities of the public to achieve a desired outcome (Lee, 2006). The relationship between political efficacy and political participation is also complex. For example, a study by Leighley and Vedlitz (1999) found that while political efficacy was associated with greater participation among White people and Mexican Americans, this relationship among African Americans and Asian-Americans was not significant. In another study, political efficacy was positively associated with civic engagement among Black Youth (Hope and Jagers, 2014).

The Social Identity Model of Collective Action (SIMCA), which integrates elements from social identity theories and collective action research, provides a theoretical framework for findings related to discrimination, political efficacy, and political participation (van Zomeren et al., 2008). SIMCA posits that group identity plays a significant role in the mobilization of collective actions, including political participation (van Zomeren et al., 2008). As mentioned, a strong sense of group identity can increase one's awareness and the saliency of perceived injustices and discrimination, which can ultimately lead to political participation (Dai et al., 2023). Further, SIMCA posits that belief in the effectiveness (i.e., efficacy) of collective action (e.g., political participation) influences individuals' motivations to participate (van Zomeren et al., 2008). Research has also shown that perceived discrimination is associated with an increased sense of efficacy when considering engagement in future civic behaviors (Rubin, 2007). Thus, the relationship between perceived discrimination, political efficacy, and political participation warrants further investigation.

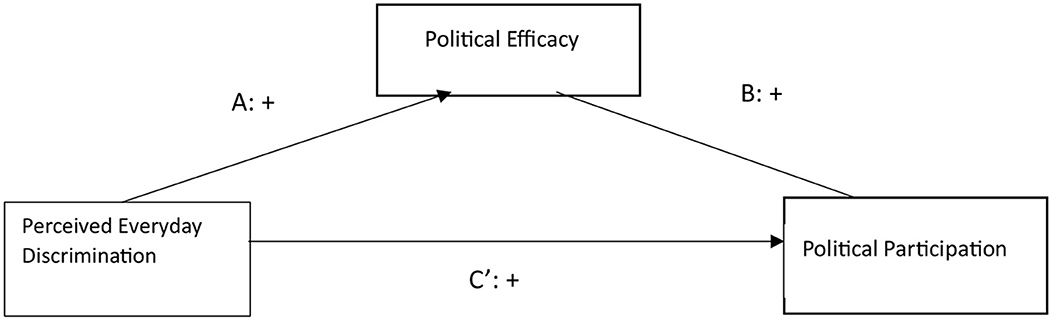

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to investigate the relationships between individual experiences of perceived everyday discrimination, political efficacy, and levels of political participation in American Indian adults. Discrimination occurs in a variety of forms and may be perceived as result of a variety of individual characteristics (e.g., weight, religion, race, etc.). Thus, the current study aimed to examine differences in the relationship between discrimination, political efficacy, and political participation between AIs that reported perceived discrimination related to race and those that reported perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity (e.g., weight, height, age, etc.) Based on previous work on perceived discrimination, political efficacy, and civic engagement in other racial and ethnic groups (Hope and Jagers, 2014), we hypothesize that experiences of discrimination related to race will be positively related to political efficacy and levels of political participation. We also hypothesize that there will be an indirect effect of perceived discrimination related to race on political participation through each subscale of political efficacy (see Figure 1). To test these hypotheses, we compared participants who reported perceived discrimination based on race to those who reported perceived discrimination not related to race/ethnicity.

Methods

The current study was approved by the X Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study. Qualtrics recruited a sample of 882 self-identifying American Indian adults (18 years or older) currently living in the United States. Qualtrics draws participants from established niche research panels for groups that less accessible including American Indians. These panels are established through targeted recruiting. All data was collected by Qualtrics and was screened for quality before being sent to investigators. This data screening included removing participants who completed the survey in less than the median time of survey completion. After data screening, all deidentified data was sent to the investigators in an excel file, and was subsequently transferred to SPSS (IBM, version 28) for analyses.

Measures

Everyday discrimination scale

The Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS; Williams et al., 1997) was used to measure self-reported frequency of routine, discriminatory experiences in everyday social situations. Respondents are asked how often a list of nine experiences happen to them in their day-to-day life. Participants respond using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “everyday”. Responses to each item are summed to create a total score for everyday discrimination. As part of this scale, participants are asked to identify the reason for perceived unfair treatment (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity). For the purposes of the current study, we included one group of participants who selected race as a reason for experiences of everyday discrimination and another group that did not select race/ethnicity as reasons for experiences of everyday discrimination.

Political efficacy

Political efficacy was measured across three subscales including internal, external, and collective efficacy (Craig et al., 1990; Geurkink et al., 2019). Respondents are asked to report their level of agreement (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) with nine statements regarding their sense of political efficacy. Three items measured participants' internal political efficacy (e.g., “Please rate your agreement with the following statement: I consider myself well qualified to participate in politics). Three items measured participants' external efficacy (e.g., “Please rate your agreement with the following statement: Politicians are not interested in what people like me think). All 3 external efficacy items were negatively phrased and thus were reverse coded. Finally, 3 items measured participants' collective political efficacy (e.g., “Please rate your agreement with the following statement: Together, Native Americans can create political change.) Higher scores across all subscales indicated higher levels of political efficacy. Cronbach's alpha was 0.88 for the internal efficacy scale, 0.81 for the external efficacy subscale, and 0.90 for the collective efficacy scale.

Political participation

A 6-item subscale was included to measure participants' involvement in politics (Ballard et al., 2020). The subscale includes items related to engagement with politic news, discussing politics, and participating in political clubs or organizations (e.g., “Please rate how often you have participated in each activity in the past month: participated in a political party, club, or organization”). Cronbach's alpha for the standard political subscale in the present sample was 0.82.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 24; IBM, Armonk, NY). Continuous covariates were standardized using z-score normalization prior to being used in analyses. From the original sample of 882 American Indian adults, we filtered data to select one group of individuals who indicated that they perceived discrimination related to their race in their everyday life, resulting in a sample of 398 American Indian adults. We also filtered data to select individuals who indicated that they perceived discrimination not related to their race/ethnicity, resulting in a sample of 329 American Indian adults. We used hierarchical linear regressions to investigate the relationship between individual experiences of perceived discrimination unrelated to racial identity and each subscale of political efficacy, and separate hierarchical regressions to investigate the relationship between individual experiences of perceived discrimination unrelated to race and political participation. We included age, sex, and income as covariates based on prior work indicating relationships between these variables and civic engagement (Kröger et al., 2015; Huyser et al., 2017). To test for potential indirect effects of race-related and non-race-related discrimination on political participation through each subscale of political efficacy, following suggestions by Preacher and Hayes (2004), we used a bootstrapping approach in which the point estimate of the indirect effect is derived from the mean of 5,000 estimates of the indirect pathways, and 95% percentile-based confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using the cutoffs for the 2.5% highest and lowest scores of the distribution. The indirect effect is considered statistically significant if the CI does not cross zero. For these analyses, we used the previously described covariates.

Results

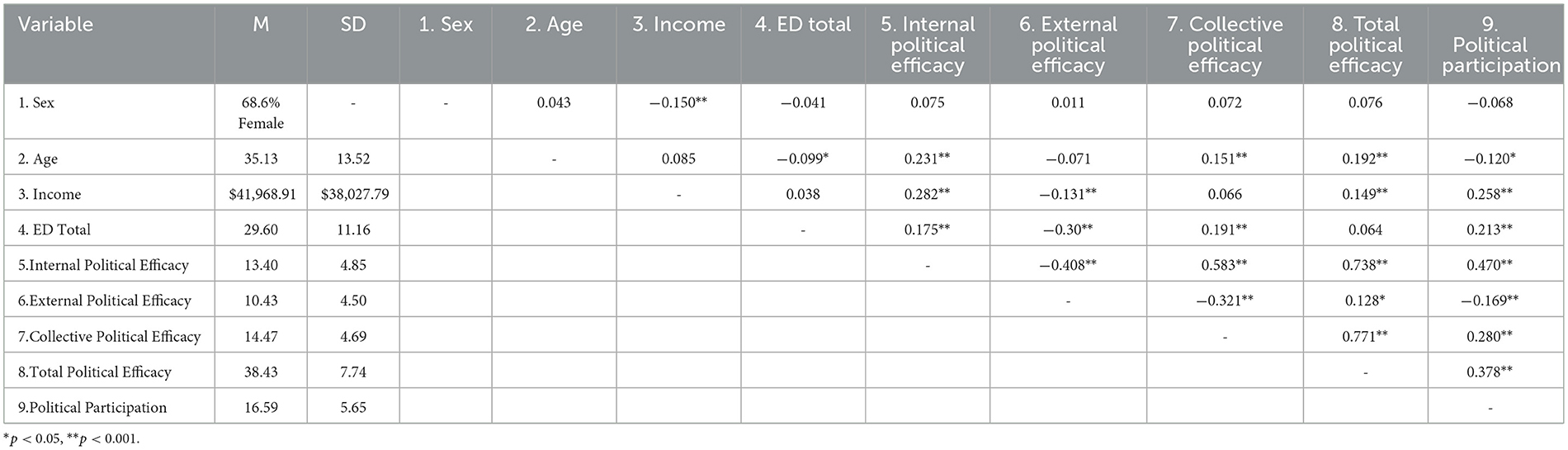

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are reported in Tables 1, 2. Of interest to the current study, perceived everyday discrimination related to race was positively associated with political participation (r = 0.213, p < 0.001), with participants who reported greater levels of discrimination reporting higher levels of political participation. Perceived everyday race-related discrimination was positively associated to internal (r = 0.175, p < 0.001) and collective (r = 0.191, p < 0.001) political efficacy, and was negatively associated with external political efficacy (r = −0.30, p < 0.001). Internal political efficacy and collective political efficacy were positively associated with political participation (r = 0.470, p < 0.001) and (r = 0.28, p < 0.001) respectively, with individuals who reported higher levels of internal and collective political efficacy reporting more political participation. External political efficacy was negatively associated with political participation (r = −0.169, p < 0.001).

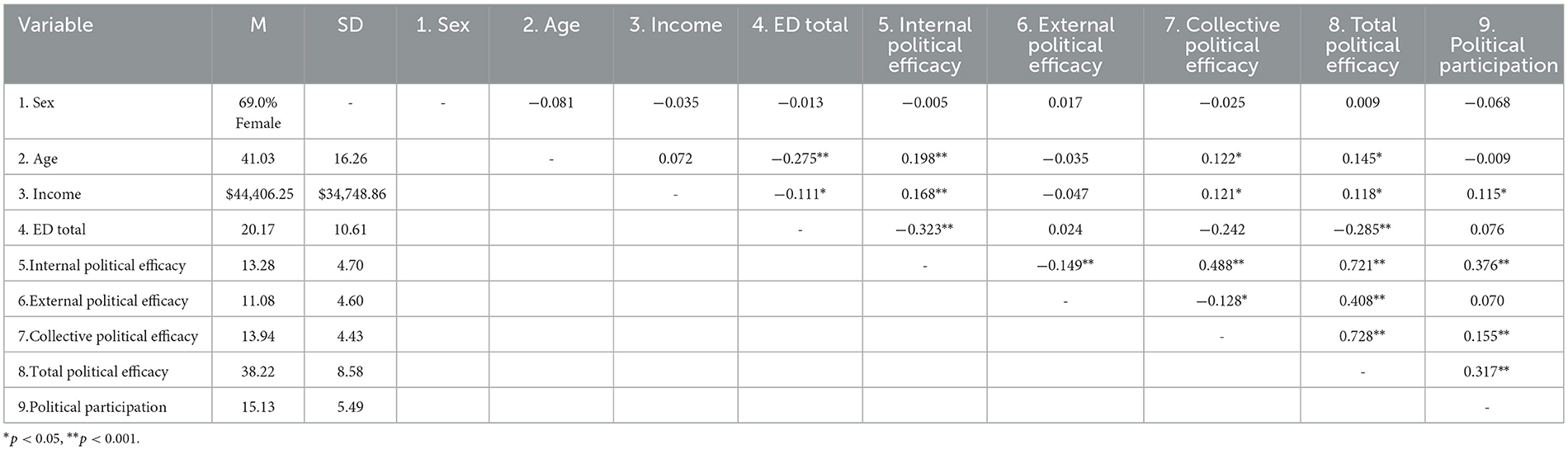

Perceived discrimination unrelated to race was negatively associated with internal political efficacy (r = −0.323, p < 0.001) and total political efficacy (r = −0.285, p < 0.001) with participants who reported greater levels of discrimination not related to race reporting lower levels of internal and total political efficacy. As opposed to perceived race-related discrimination, perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity was not significantly associated with political participation (r = 0.076, p < 0.001). Internal (r = 0.376, p < 0.001), collective (r = 0.155, p < 0.001), and total (r = 0.317, p < 0.001) political efficacy were positively associated with political participation.

Perceived race-related discrimination and political efficacy

In separate hierarchical linear regressions predicting each dimension of political efficacy, we entered the previously described covariates in Step 1, and individual experiences of perceived discrimination related to race in step 2. Perceived everyday discrimination related to race was a significant predictor of internal political efficacy [B = 0.18, t(352) = 3.68, p < 0.001, r2 change=0.032, F(1,352) = 17.90, p < 0.001], external political efficacy [B = −0.29 t(381) = −5.88, p < 0.001, r2 change = 0.08, F(1,381) = 10.80, p < 0.001] and collective efficacy [B = 0.21 t(381) = 4.23, p < 0.001, r2 change = 0.043, F(1,381) = 7.70, p < 0.001].

Political efficacy and political participation

In three separate hierarchical linear regressions predicting total political participation, we entered the previously described covariates in Step 1 and subscales of political efficacy in step 2. Internal political efficacy was a significant predictor of political participation [B = 0.49, t(352)=10.19, p < 0.001, r2 change = 0.21, F(1,352) = 35.42, p < 0.001], as was collective political efficacy [B =0.31, t(381) = 6.56, p < 0.001, r2 change =0.09, F(1,381) = 20.80, p < 0.001], and external political efficacy [B = −0.15 t(381) = −3.15, p = 0.002, r2 change = 0.02, F(1,381) = 11.74, p < 0.001].

Perceived race-related discrimination and political participation

In a separate hierarchical linear regression predicting political participation, we entered the previously described covariates in Step 1, and perceived discrimination related to race in step 2. Individual experiences of perceived discrimination related to race was a statistically significant predictor of political participation [B = 0.19, t(381) = 3.91, p < 0.001, r2 change = 0.04, F(1,381) = 13.20, p < 0.001].

Political efficacy as a mediator of race-related discrimination and political participation

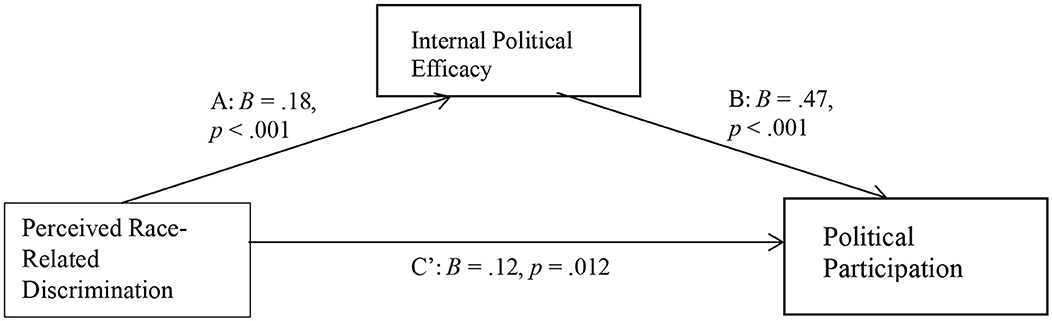

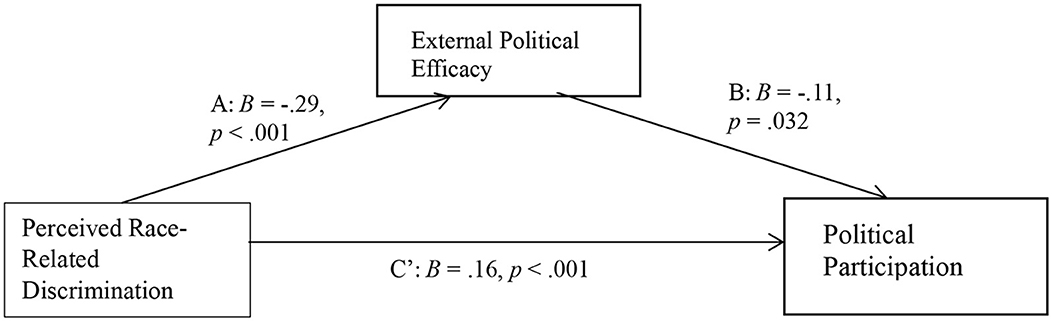

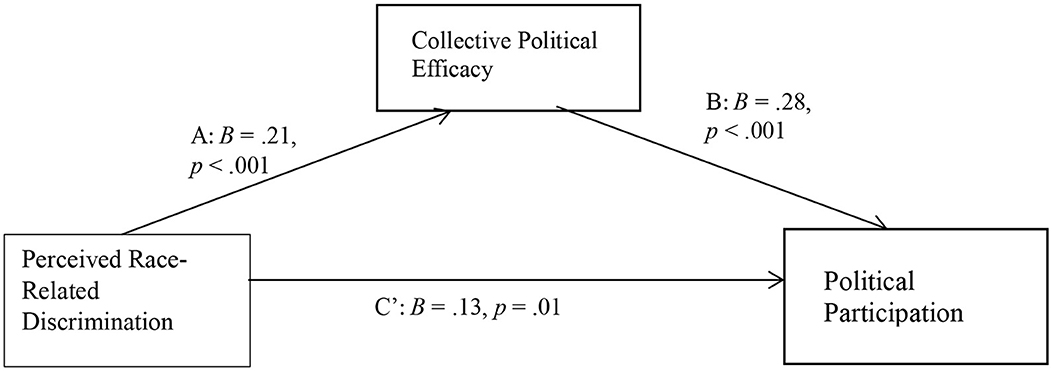

Using the previously described method (Preacher and Hayes, 2004), we found a statistically significant indirect effect of race-related discrimination on political participation through internal political efficacy (B = 0.09, SE = 0.03, CI [.04, 0.14]), through collective political efficacy (B = 0.06, SE = 0.02, CI [0.03, 0.10]), and through external political efficacy (B = 0.03, SE = 0.02, CI [0.0008, 0.06]. The results of the mediation models are depicted in Figures 2–4.

Figure 2. Mediation model of internal political efficacy on relationship between perceived race-related discrimination and political participation.

Figure 3. Mediation model of external political efficacy on relationship between perceived race-related discrimination and political participation.

Figure 4. Mediation model of collective political efficacy on relationship between perceived race-related discrimination and political participation.

Perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity and political efficacy

In separate hierarchical linear regressions predicting each dimension of political efficacy, we entered the previously described covariates in step 1, and individual experiences of perceived discrimination unrelated to race in step 2. Perceived everyday discrimination unrelated to race or ethnicity was a significant negative predictor of internal [B = −0.303, t(285)= −5.03, p < 0.001, r2 change = 0.076, F(1,285) = 12.203, p < 0.001] and collective [B = −0.235, t(315) = −3.97, p < 0.001, r2 change = 0.046, F(1,315) = 6.439, p < 0.001] political efficacy, but was not a significant predictor of external political efficacy [B = 0.004, t(315) = 0.069, p = 0.945, r2 change = 0.000, F(1,315) = 0.282, p = 0.890].

Political efficacy and political participation (race not selected)

In three separate hierarchical linear regressions predicting total political participation, we entered the previously described covariates in step 1 and subscales of political efficacy in step 2. Internal political efficacy was a significant predictor of political participation [B = 0.377, t(285) = 6.57, p < 0.001, r2 change = 0.129, F(1,285) = 12.61, p < 0.00], as was collective political efficacy [B = 0.161, t(315) = 2.78, p = 0.006, r2 change = 0.024, F(1,315) = 3.33, p = 0.011], while external political efficacy was not a significant predictor of political participation [B = 0.070 t(315) = 1.28, p = 0.203, r2 change = 0.005, F(1,315) = 1.78, p = 0.133].

Perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity and political participation

In a separate hierarchical linear regression predicting political participation, we entered the previously described covariates in step 1, and perceived discrimination unrelated to race in step 2. Perceived discrimination unrelated to race or ethnicity was not a statistically significant predictor of political participation [B = 0.093, t(315) = 1.49, p = 0.139, r2 change = 0.007, F(1,315) = 1.923, p = 0.106].

Political efficacy as a mediator in relationship between discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity and political participation

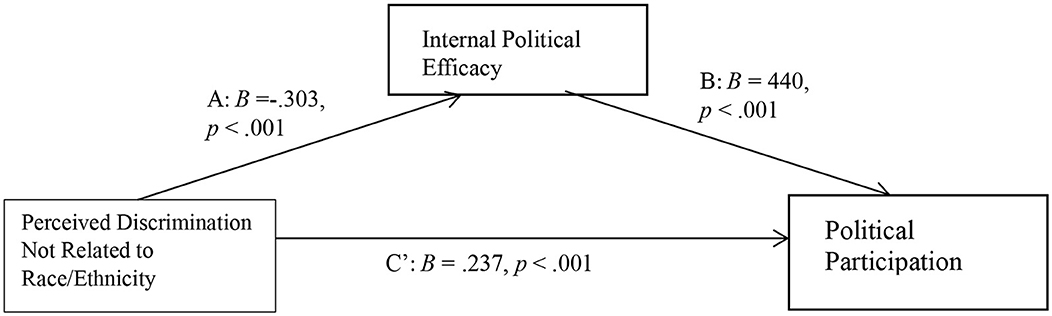

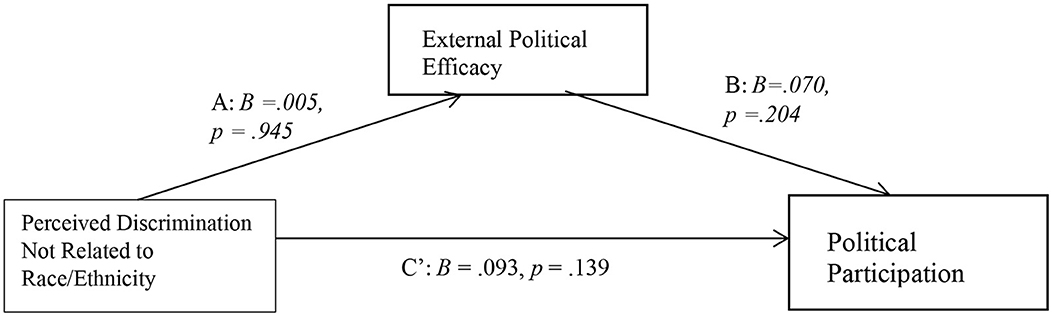

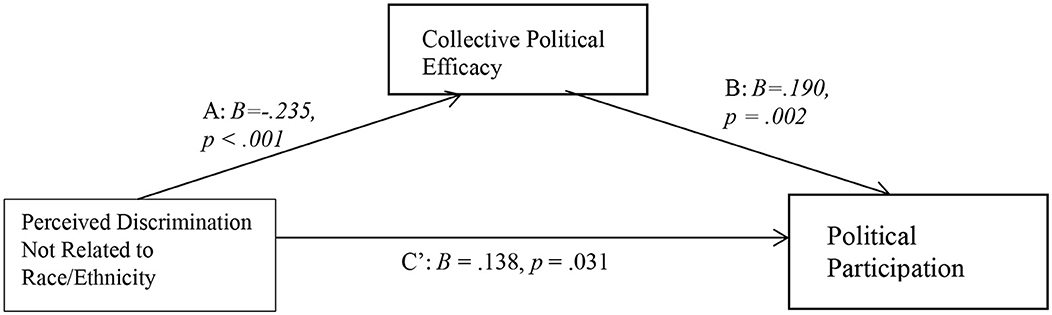

Using the previously described method (Preacher and Hayes, 2004), we found a statistically significant indirect effect of discrimination unrelated to race on political participation through internal political efficacy (B = −0.13, SE = 0.03, CI [−0.200, −0.080]), through collective political efficacy (B = −0.04, SE = 0.02, CI [−0.08, −0.01]), but not through external political efficacy (B = 0.0003, SE = 0.007, CI [−0.02, 0.01]. The results of the mediation models are depicted in Figures 5–7.

Figure 5. Mediation model of internal political efficacy on relationship between perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity and political participation.

Figure 6. Mediation model of external political efficacy on relationship between perceived discrimination not related to race/ethnicity and political participation.

Figure 7. Mediation model of collective political efficacy on relationship between perceived discrimination not related to race/ethnicity and political participation.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to explore relationships between individual experiences of perceived discrimination related to race, perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity, political efficacy, and political participation in American Indian adults. Based on previous work indicating links between perceptions of group discrimination and forms of civic engagement in other groups (White-Johnson, 2012; Oskooii, 2020), one study indicating that Native American identification is associated with increased civic engagement through increased perceptions of group discrimination (Dai et al., 2023), and previous research indicating the links between political efficacy and political participation (Hope and Jagers, 2014; McDonnell, 2020), we hypothesized that in this sample of American Indian adults, reports of more frequent individual experiences of discrimination related to race in everyday life would predict greater levels of political participation through increased political efficacy. We also aimed to compare participants who reported perceived discrimination based on race, to those who did not select race/ethnicity as reasons for experiencing discrimination. By comparing these groups of participants, we were able to investigate the differential and nuanced effects that racial/ethnic forms of discrimination have on political efficacy and political participation relative to other types of discrimination (e.g., discrimination based on weight, height, etc.). The data from the current sample of American Indian adults partially supported our hypotheses.

Perceived race-related discrimination

The relationship between perceived race-related discrimination, external political efficacy and political participation did not occur in the manner that we had anticipated. While we did not accurately predict this finding, it is not surprising. First, previous research has shown that perceptions of discrimination can be associated with lower levels of external political efficacy (Shore et al., 2019). These findings were confirmed in the current study for perceived race-related discrimination and external political efficacy, Further, the finding that lower levels in the belief that the government is responsive to demands of citizens (i.e., external political efficacy) is associated with greater political participation inherently means that individuals who believe the government is responsive (i.e., high external political efficacy) are less likely to participate in politics. Thus, if the government is responsive and cares about the people, one might not perceive a need to directly participate. Further, individuals who report higher external efficacy may be more content with their current situation, the status quo, and thus lack the motivation that often accompanies a desire for change: If I'm happy with the way things are, why spend my time on something that doesn't need fixing? Another potential explanation is that by believing political parties do not care about them, or that they are not responsive to their demands (i.e., low external political efficacy) American Indian adults may be motivated to participate politically to ensure that their voices are heard. For example, a recent study from the Netherlands found that lower levels of external political efficacy were associated with a greater likelihood of voting for a populist party (Geurkink et al., 2019). Thus, if an individual perceives the current ruling party as unresponsive and uncaring (i.e., low external political efficacy), they may be motivated to participate politically to get rid of the unresponsive party in exchange for one that is more responsive and receptive to the individual (e.g., populist party) (Geurkink et al., 2019).

In line with our hypotheses, perceived everyday race-related discrimination was positively associated with political participation, suggesting that individuals who reported more perceived race-related discrimination participated more in politics. Further, perceived race-related discrimination was positively associated with internal and collective political efficacy, both of which were positively associated with political participation.

Finally, we found a significant indirect effect of individual experiences of perceived race-related discrimination on political participation through each subscale of political efficacy. This finding raises the possibility that in American Indians, individual experiences of race-related discrimination in everyday life influence levels of political participation by affecting each subscale of political efficacy. Thus, political efficacy may be a target for interventions seeking to increase overall levels of American Indian civic engagement. Given that internal political efficacy exhibited the strongest relationship with political participation, interventions that promote political knowledge, and the ability to understand and participate in politics may be particularly impactful for bolstering political participation among American Indian adults.

Perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity

In contrast to perceived race-related discrimination, discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity was not a significant predictor of political participation. Further, perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity negatively predicted internal and collective political efficacy and did not exhibit a significant relationship with external political efficacy. Internal and collective political efficacy both positively predicted political participation while external political efficacy did not. Finally, we found a significant indirect effect of perceived discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity on political participation through internal and collective political efficacy, but not through external political efficacy.

These findings are nuanced and point to the saliency of discrimination related to race in relation to politics. First, perceived discrimination unrelated to race was not significantly predictive or political participation on its own. Further, rather than increasing a sense of one's ability to understand and participate in politics (i.e., internal political efficacy) as well as a belief that one's group can achieve a desired goal (i.e., collective efficacy), discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity negatively predicted these forms of efficacy that were positively predicted by perceived race-related discrimination. Internal and collective efficacy were still positively predictive of political participation, indicating that even due to the negative impacts that perceived discrimination not related to race has on political efficacy, those who maintain some sense of internal and/or collective efficacy are still more likely to participate in politics. This finding points to the powerful effects of political efficacy in relation to political participation. Finally, despite not directly predicting political participation, perceived discrimination unelated to race diminishes individual's internal and collective efficacy which ultimately reduces their likelihood of participating in politics.

These findings are important in that they provide evidence in support of perceived race-related discrimination as a motivating factor to participate in politics for AI adults. It also points to the resilience of AIs that despite facing discrimination based on their race, they maintain confidence in themselves (i.e., internal efficacy) and their group (i.e., collective efficacy) and actively participate in politics.

The directionality of observed relationships in the current research may be unexpected in that one could theorize that the more an individual perceives that others are discriminating against them because of their race, they may be more likely to feel individually unqualified to participate in politics (i.e., lower internal efficacy) and less likely to believe that others like them can effectively engage in the political system (i.e., lower collective efficacy), or may choose to disengage to avoid future experiences of discrimination linked to their race. However, experiencing discrimination related to race may evoke a sense of empowerment, as well as a shared identity that leads to mobilization to create change (Dai et al., 2023). To elaborate on this point, race-related experiences of discrimination could heighten one's perception of division and reduce one's sense of shared experiences and values. However, the pattern of findings in the current work suggests that more individual experiences of race-related discrimination in everyday life are instead tied to higher levels of both internal and collective efficacy.

On the other hand, the findings from the current study suggest that perceptions of discrimination unrelated to race/ethnicity may not be as politically relevant or motivating as discrimination related to race, as evidenced by a non-significant relationship between perceived discrimination related not related to race/ethnicity and political participation, as well as negative relationships between perceived discrimination not related to race/ethnicity and internal and collective efficacy. Based on the tenets of SIMCA (van Zomeren et al., 2008), it may be that an individual's sense of group identity is stronger for race/ethnicity, and thus perceptions of discrimination based on this salient group identity may be a particularly powerful motivator for political participation relative to discrimination based on other factors (e.g., weight, height, etc.) that may not evoke as strong of a sense of group identity, and result in less of desire and sense of efficacy to act collectively within that group.

There are important limitations of this research to note. First, this research is cross-sectional, and thus it is not possible to draw inferences about causality. Follow-up research should collect longitudinal daily life data (i.e., ecological momentary assessment) to investigate whether everyday experiences of race-related discrimination predict subsequent levels of internal and collective political efficacy and political participation. While in the current work, we theorize that experiences of race-related discrimination may affect political efficacy and subsequently affect levels of political participation, it is also possible that discrimination experiences may directly affect political participation which may then affect political efficacy. It will also be important to understand whether reprieves from everyday discrimination related to race would have positive or negative effects on political efficacy and levels of political participation. The current work does not include consideration of logistical barriers which may negatively affect American Indian adults to participate in the political system. Further, the wording of the political efficacy scale used in the current work is ambiguous in its reference to politics. As noted previously, tribal issues are of utmost importance to many American Indians, and as such, it is possible that the pattern of the findings observed here could be affected by the type of politics (i.e., tribal vs. national politics). In future work it will be important to understand whether race-related discrimination has unique implications for participation in tribal vs. national politics. Finally, the current study is limited in that it focuses on individual experiences of discrimination rather and does not include group-based perceived discrimination. As mentioned in the introduction, the relationship between perceived discrimination and political participation is influenced by whether the discrimination is individually experienced or group-based (e.g., Jalalzai, 2010; Oskooii, 2020). Future research would benefit from examining group-based vs. individually perceived experiences of discrimination, and how these relate to political efficacy and participation.

The relationship between other types of discrimination that are not related to race/ethnicity and their relationships to political efficacy and political participation warrant further investigation, particularly in situations when identification with a group based on factors such as age, weight, disability, etc. are politically relevant (e.g., changing voting age, laws affecting individuals with disabilities). In these cases, identification with the group may become more salient, perceptions of discrimination based on the group identity may increase, and a motivation and sense of capability to address the injustices may increase both political efficacy and political participation. Overall, the current work makes an initial contribution to our understanding of the relationship between individual experiences of everyday discrimination related to race and political participation in American Indian adults and highlights a potential mechanism (i.e., political efficacy) through which these individual race-related discriminatory experiences may affect political participation in this population.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Montana State University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ZW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. NJ-H: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers P20GM103474, P20GM104417, and U54GM115371 and by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MD015894. P20GM104417, P20GM103474, and R01MD015894 supported authors' time and effort toward this manuscript and U54GM115371 provided funds to support data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

Ballard, P. J., Ni, X., and Brocato, N. (2020). Political engagement and wellbeing among college students. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 71, 101209. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2020.101209

Corntassel, J. J., and Witmer, R. C. (1997). American Indian tribal government support of office-seekers: findings from the 1994 election. Soc. Sci. J. 34, 511–525. doi: 10.1016/S0362-3319(97)90009-4

Craig, S. C., Niemi, R. G., and Silver, G. E. (1990). Political efficacy and trust: A report on the NES pilot study items. Polit. Behav. 12, 289–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00992337

Dai, J. D., Yellowtail, J. L., Munoz-Salgado, A., Lopez, J. J., Ward-Griffin, E., Hawk, C. E., et al. (2023). We are still here: omission and perceived discrimination galvanized civic engagement among Native Americans. Psychol. Sci. 34, 739–753. doi: 10.1177/09567976231165271

Geurkink, B., Zaslove, A., Sluiter, R., and Jacobs, K. (2019). Populist attitudes, political trust, and external political efficacy: old wine in new bottles? Polit. Stud. 68, 247–267. doi: 10.1177/0032321719842768

Gone, J. P., and Trimble, J. E. (2012). American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 8, 131–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127

Hope, E. C., and Jagers, R. J. (2014). The role of sociopolitical attitudes and civic education in the civic engagement of black youth. J. Res. Adolesc. 24, 460–470. doi: 10.1111/jora.12117

Huyser, S., Sanchez, G. R., and Vargas, E. D. (2017). Civic engagement and political participation among American Indians and Alaska natives in the US. Polit. Groups Ident. 5, 642–659. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2016.1148058

Jalalzai, F. (2010). Anxious and active: Muslim perception of discrimination and treatment and its political consequences in the post-September 11, 2001 United States. Polit. Relig. 4, 71–107. doi: 10.1017/S1755048310000519

Kahn, B. A. (2013). A place called home: Native sovereignty through statehood and political participation. Nat. Res. J. 53, 1–53.

Kröger, H., Pakpahan, E., and Hoffmann, R. (2015). What causes health inequality? A systematic review on the relative importance of social causation and health selection. Eur. J. Public Health 25, 951–960. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv111

Lee, F. L. F. (2006). Collective efficacy, support for democratization, and political participation in Hong Kong. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 18, 297–317. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/edh105

Leighley, J. E., and Vedlitz, A. (1999). Race, ethnicity, and political participation: competing models and contrasting explanations. J. Polit. 61, 1092–1114. doi: 10.2307/2647555

Littenberg-Tobias, J., and Cohen, A. K. (2016). Diverging paths: understanding racial differences in civic engagement among White, African American, and Latina/o Adolescents Using Structural Equation Modeling. Am. J. Community Psychol. 57, 102–117. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12027

McDonnell, J. (2020). Municipality size, political efficacy and political participation: a systematic review. Local Govern. Stud. 46, 331–350. doi: 10.1080/03003930.2019.1600510

Min, J., and Savage, D. (2014). Why do American Indians vote democratic? Soc. Sci. J. 51, 167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2013.10.015

Oskooii, K. (2020). Perceived discrimination and political behavior. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 50, 867–892. doi: 10.1017/S0007123418000133

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Meth. Instrum. Comp. 36, 717–731. doi: 10.3758/BF03206553

Reeves, A., and Mackenbach, J. P. (2019). Can inequalities in political participation explain health inequalities? Soc. Sci. Med. 234:112371. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112371

Rubin, B. C. (2007). “There's still not justice”: youth civic identity development amid distinct school and community contexts. Teachers College Rec. 109, 449–481. doi: 10.1177/01614681071090020

Sells, B. L. (2012). “The Voting Rights Act in South Dakota: One litigator's perspective on reauthorization,” in The Most Fundamental Right (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press), 188.

Shore, J., Rapp, C., and Stockemer, D. (2019). Health and political efficacy in context: what is the role of the welfare state? Int. J. Comp. Sociol. 60, 435–457. doi: 10.1177/0020715219899969

Taylor, D. M., Wright, S. C., and Ruggiero, K. M. (1991). The personal/group discrimination discrepancy: responses to experimentally induced personal and group discrimination. J. Soc. Psychol. 131, 847–858, doi: 10.1080/00224545.1991.9924672

Thornton, R. L., Glover, C. M., Cené, C. W., Glik, D. C., Henderson, J. A., and Williams, D. R. (2016). Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Affairs. 35, 1416–1423. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1357

van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., and Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: a quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 134, 504. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

White-Johnson, R. (2012). Prosocial involvement among African American young adults: Considering racial discrimination and racial identity. J. Black Psychol. 38, 313–341. doi: 10.1177/0095798411420429

Keywords: American Indian, discrimination, political efficacy, political participation, race/ethnicity

Citation: Wood ZJ and John-Henderson NA (2024) Perceived discrimination, political efficacy, and political participation in American Indian adults. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1328521. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1328521

Received: 26 October 2023; Accepted: 21 February 2024;

Published: 22 March 2024.

Edited by:

Yuan Wang, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Alexander Jedinger, GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, GermanyDavin Phoenix, University of California, Irvine, United States

Copyright © 2024 Wood and John-Henderson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Neha A. John-Henderson, bmVoYS5qb2huaGVuZGVyc29uQG1vbnRhbmEuZWR1

Zachary J. Wood

Zachary J. Wood Neha A. John-Henderson

Neha A. John-Henderson