- 1Department of Sociology and Work Science, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

- 2Department of Social Policy, Sociology and Criminology, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom

The study contributes new knowledge about civil society and non-profit action in superdiverse neighbourhoods that face socioeconomic challenges in England and Sweden. Locally based grassroot organisations are of special interest and demonstrate substantial voluntary altruism. Since little is known about the nature of civil society in these conditions, this paper addresses a gap in knowledge using material from interviews with founders and actors of grassroots action and micro-mapping in four neighbourhoods. The analysis draws upon perspectives within Social Sciences to shed light on the offerings of grassroots activity with a particular focus on emergence narratives. Three axes of interest frame the analysis: actors’ motivations, resources and ways of working. In short, actors base their work on lived experiences and a shared vision to mitigate inequalities not addressed by mainstream services. Actors employ a creative use of local resources to achieve shared goals, building on the diversity of local population in innovative ways and developing value-driven assets-based approaches alongside flexible ways of working.

1 Introduction

The purpose of this article is to contribute knowledge about narratives of emergent processes of civil society organisations in conditions of superdiversity and socioeconomic challenge, focusing on actors’ motivations, resources and ways of working. Civil society or non-profit organisations are widely acknowledged to offer distinctive approaches to addressing social challenges alongside bringing opportunities for self-organising around interests and activities. The organisations framed as ‘grassroots’ are of special interest (Andersson, 2022; Phillimore et al., 2018) as they may dominate in areas with high levels of diversity (Elgenius et al., 2023b). Grassroots activity, building on Smith (2000: 7), refers to locally based, autonomous, non-profit activity that demonstrate substantial voluntary altruism and use associational forms of organisation. The scale of grassroot activity is unknown but thought to considerably exceed that of action by larger formalised charities and nonprofits (MacGillivray et al., 2001; Elgenius et al., 2023b). The lack of knowledge about grassroot organisations is partly due to that they have a tendency to, in early stages of their establishment, remain off registers, which has led this part of civil society being referred to as “below the radar” (McCabe et al., 2010). The lack of quantifiable and qualitative data about grassroot organisations has been noted elsewhere and described as the ‘black box’ of civil society research (Rainey et al., 2017). The lack of knowledge is problematic because many grassroot organisations may start with informal groups and eventually evolve into formal organisations and have increasingly been understood as displaying core mechanisms to deliver important services locally (Brandsen et al., 2017). Scholars and activists have also long asserted that sub-groups of civil society such as rural or Black and minority ethnic (BME) groups develop distinctive ways of working that reflect geography and identity. It has also been suggested these organisations face a double-whammy of challenges relating to both their small scale and minoritised status meaning they struggle to access funding, pushing them to find innovative ways of working (Mayblin and Soteri-Proctor, 2011).

The argument that high levels of ethnic and racial diversity are linked to a low density of civil society activity as per Putnam’s (2007) claims about the erosion of trust in diverse areas underpin many studies even if increasingly challenged by findings of a postive relationship between diversity and civil society organisations [see, e.g., Borkowska et al. (2024)]. Moreover, studies such as these rely heavily on survey or administrative data and will exclude grassroots and the kind of actions more likely to be present in diverse areas. Thus, levels of activity may appear lower in diverse areas because researchers only look at registered activity (Elgenius et al., 2023b). In view of demographic trends and the superdiversification of many already diverse urban neighbourhoods, populations today include many smaller groups from many different countries. Their needs are determined by increasingly varied immigration statuses and variegated rights and entitlements (Vertovec, 2007; Grzymala-Kazlowska and Phillimore, 2018) which have reshaped the conditions of civil society.

Thus, little is known about the nature of civil society operating in superdiverse areas, how they emerge and evolve, the actors’ motivations, their ways of working and the resources utilised (Andersson and Walk, 2022). Our paper addresses this gap in knowledge by focusing on the emergence narratives of civil society organisations operating in conditions of superdiversity and socioeconomic challenge, the majority of whom began as grassroots organisations in smaller, informal and local constellations. The analysis draws upon perspectives from related disciplines within the Social Sciences to shed light on the offerings of grassroots activity. We utilise three axes of analysis – actors, resources and ways of working – to explore how these contribute toward shaping the emergence of organisations. Such an understanding is important from different perspectives as civil society has an increasingly critical role in the delivery of different welfare services (Mccabe, 2017), alongside the promotion of inclusion, community building and social justice. More knowledge is also needed about civil society in these conditions and how action is motivated, developed and sustained. Using data from interviews with founders of organisations which were originally initiated in different ways as grassroots actions in four superdiverse neighbourhoods in Birmingham in England and Gothenburg in Sweden, we contribute to a neglected field of research on civil society in superdiverse neighbourhoods facing socio-economic challenges where civil society actions can mitigate disadvantage and promote inclusion.

The paper commences by defining the nature and evolution of grassroots actions in the Global North and outlining the ways in which emergence processes and growth have been previously theorised with focus on actors, resources and ways of working. Thereafter, we outline our methodology and nature of materials and make a case for how retrospective interviewing can contribute to the understanding emergence processes. The material on emergence processes and the nascent phase of civil action are subsequently analysed with reference to the narratives shared by actors, before exploring their resources and ways of working. We conclude by highlighting the key role of grassroots organising at the nascent stage of civil society action and the importance of understanding how grassroots evolve in superdiverse neighbourhoods that face socio-economic challenges.

2 Grassroots actions and civil society lifecycles

Grassroots civil society actions have been described as a specific sub-sector of civil society compelled by social and ideological concerns (Sillig, 2022). Grassroots action is often distinguished from non-grassroots action as it operates on behalf of “those who are most severely affected in terms of the material condition of their daily lives” (Cajaiba-Santana, 2014: 398). The related concept grassroots innovation has also been applied to different kinds of initiatives (Hossain, 2016) and initiated from the bottom up, ideologically motivated and responding to social needs. Thus, grassroots innovations are generally founded on local community action and networks, sometimes portrayed as resisting dominant structures and contributing to institutional reform which may be particularly important in diverse areas where levels of deprivation are high. While some grassroots actions remain informal, unregistered and small-scale, others expand beyond their grassroots becoming formalized, a matter which calls for more work on emergence narratives, organisational histories and enabling opportunity structures [see, e.g., Elgenius et al. (2023a) and Phillimore (2021)].

Civil society scholars have therefore sought to understand the development and “lifecycles” of civil society organisations and development as a linear evolution from the initial idea and start up, to growth, maturity, decline and crisis. The “lifecycle” terminology serves as a heuristic tool intended to support interventions (Social Trendspotter, 2019) whereas processes for civil society organisations may not be linear at all (Zhou, 2016). Andersson et al. (2016) highlight that operations can reach a point of crisis at any point in the lifecycle, rather than after reaching maturity as has been suggested. Mitchell (2019) suggests a focus on four phases: the incubation phase where there is little engagement with stakeholders, the interaction phase where requests for funds and other kinds of support are transaction based, the immersion stage where regular service delivery is assured by activities undertaken by volunteers aligned with the missions of organisations, and the incapacity stage when organisation cease to exist. Other scholars attend to factors beyond the lifecycle, such the importance of the social, political and geographical contexts within which organisations emerge as these influences organisational goals and values (Suykens et al., 2019).

As highlighted by Peucker (2021) and Mayblin and Soteri-Proctor (2011) few studies have properly explored the early stages of civil society in diverse areas. Scholarship tends to focus on populations rather than actions serving neighbourhoods which may contain many different groups (Vertovec, 2007). Overall, we know little about civil society actions within neighbourhoods facing socioeconomic challenges where material resources are in short supply and actions may not follow the normative patterns of development observed in the wider grassroots sector. However, it is conceivable that many organisations commence as grassroots actions and that they come and go or expand beyond their grassroots origins.

2.1 Three axes of analysis for the emergence processes of grassroot action

Andersson (2022) identifies several gaps in knowledge about the evolution of nonprofit and grassroot action, including the evolution and experience of non-registered organisations in the period before being registered. Edenfield and Andersson (2018) explore the transformation from informal initiatives to formal organisations as part of the lifecycle model. They highlight that attention must be paid to the emergence of new non-profit initiatives and the characteristics of actions at the nascent or pre-venture stage and the start-up stage because these shape organisations longer-term functions and structures. They also argue for the study of transition saying it is ‘essential to begin to comprehend how an organisation’s identity, structures, operational norms etc. become imprinted onto new organisations’ (Edenfield and Andersson, 2018: 1033). Thus, a focus on the early stages of action attends to how actors, resources and ways of working come together before formalised actions are initiated and enables the identification of actors’ and initiators’ motivations. Edenfield and Andersson (2018) stress the need to look at resources and early-stage systems such as financial and management structures and the formation of roles, responsibilities and procedures that come together in ways of working. Undertaking research with organisations at the nascent and start-up phases is clearly challenging because they lack visibility at these stages. Overall, three axes of interest are identified in our research on the nascent phases of civil society action and work as a framing for the analysis; actors and their motivations, resources utilised and the ways in which organisations work.

2.1.1 Actors and their motivations

Martens et al. (2021) emphasise that grassroots actions emanate from individuals who share a vision with a larger group and initiate a participatory governance process. Initiators tend to respond to unmet needs or the failures of the welfare state. Jungsberg et al. (2020) also highlight that individual innovations are important in the initiation phase alongside exploring how local associations and authorities facilitate grassroots actions whereas Sillig (2022) mentions that actors are linked to a network or actor-world wherein shared visions provide a uniting perspective. For instance, centering on Muslim activism Peucker (2021) finds that action was motivated by experiences of inequalities and the need to tackle misconceptions or prejudice of fellow Muslims. Thus, a common cause or shared ideology are key motivators for actors of grassroots innovation. Social movement theory has also contributed to understanding mobilisation as a result of structural strains as has the relative deprivation thesis which specifically highlights that people are driven to act when they experience inequality, which connects to the core ideas around grassroot motivations in the nascent stage (Gurr, 2015). Social constructivist approaches have partly shifted away from emphasising the emergence of grassroot action because of class-struggle to that of collective identity organising around gender or ethnicity. In sum, grassroot actors and organisations prioritise the common good and their communities rather than having expansionist agendas, even if little is known about the extent to which ideologies are retained when organisations expand beyond their nascent phase.

2.1.2 Resources

Civil society often rely on funds from multiple sources (Bothwell, 2002) and actors mobilise various kinds of resources to generate action which may include material resources, solidarity, strategies and social networks, human capital through leaders and volunteers and cultural resources such as the experience of activism (Edwards and McCarthy, 2004). Grassroot action is hereby distinguished from market-based innovations by the nature of its actor-network and the balance between the internal and external networks. Internal networks consist of individuals operating locally and cooperating with authorities whereas external networks refer to funding, offices, volunteers and other support (Hatzl et al., 2016). External funding is generally only available to registered organisations (Hyde, 2000) as is membership fees that enable self-funding (Papakostas, 2011) and income raised through activities (Waters and Davidson, 2018). Knowledge of rules and regulations around financial management and safeguarding are therefore key and organisations often need to mobilise overlapping forms of resources to allow for individuals to achieve a common purpose.

As Smith (2000) argues, voluntary altruism is core to grassroot activity and involves qualities such as care and sharing of self. Individuals bring skills and experience (Maton, 2000) a range of emotional resources and social capital, often in the form of volunteers as the main human resource (Smith, 2000) and engaging and retaining volunteers demands certain skills and conditions (Hasenfeld and Gidron, 2005). Affective ties are important to connect volunteers and employees together enabling companionship and loyalty (Mirza and Reay, 2000: 525). These are also related to moral resources ‘by and for’ and the capability of representing particular groups or places and constitute a marker of moral capital (Hasenfeld and Gidron, 2005). Similarly, moral and cognitive legitimacy has been identified as key to organisations formation, voice, formalisation and impact (Cannon, 2020) sometimes as a result of avoiding formalisation and co-option by the state (Soteri-Proctor and Alcock, 2012). Legitimacy or insider status is seemingly critical for grassroot action in the emergence stages in diverse neighbourhoods where levels of trust are potentially low (Putnam, 2007).

Since grassroots organisations are frequently run by a small number of leaders, new leaders are nurtured through training volunteers, skills mobilisation and learning civic skills (Chetkovich and Kunreuther, 2006; Hasenfeld and Gidron, 2005) building on local and insider knowledge when dealing with specific groups. Elsewhere Yosso (2005) writes about the importance of resources brought by ‘Communities of Color’ and calls for a cultural wealth approach which highlights resources neglected in civil society scholarship. These include familial, aspirational, linguistic, resistant and navigational resources and enable new ways of civil society organising. Individuals with diverse backgrounds can also bring more diverse skills and expertise to civil society given that they hail from many different countries with varying welfare state and civil society conditions. Overall, civil society benefits from such embeddedness and inter-organisational networks that mobilise social, economic and political resources.

2.1.3 Ways of working

Grassroots actions are often determined by mechanisms such as learning by doing, relationships and trust, rather than relying on experts (Mccabe, 2017). Van Lunenburg et al. (2020) highlights bricolaging as central to grassroots innovation where actors create resources from whatever is available. Phillimore et al. (2018) show how grassroots actors act as bricoleurs within local health and welfare ecosystems, filling gaps in provision of services. Organisations worked flexibly tailoring their services to individual needs, and possessed knowledge about local resources and networks which enabled them to utilise resources and expertise beyond the reach of the state. Luthra (2018) has identified creative agency and innovative leadership as key aspects of the grassroot ethos which enable the creation of new platforms and practices in response to identified challenges. Florian (2018) found that flexible and egalitarian ways of working and the social proximity between leadership and membership was important in emerging grassroot processes and Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2019) emphasises strategic innovation and specialised approaches around new technologies to overcome resource shortages. Elgenius (2023) has outlined civil society’s multidimensional pathways to inclusion and integration paying attention to the importance of socio-psychological factors such as support, compassion, aspirations, hope and resistance against destructive narratives. In all such cases, grassroot action is highlighted as a case of problem-solving rather than of gaining social power.

The ways in which civil society action is sustained and expanded has been explained by the term ‘constrained innovation’ (Campbell, 2005) characterised by smaller changes observable over time (Gåsemyr, 2015). Arvidson (2018) also highlights the conceptual pairing of change and tension and point toward non-linear and ever-evolving processes. Thus, grassroot innovation is a bottom-up process and the social nature of initiatives are driven by the desire to achieve impact (van Lunenburg et al., 2020). Some grassroots organisations may scale up and seek to embed their innovation within institutional structures, while others may scale out trying to impact more people by replicating their work in different geographical areas as in the case of supporting young people with their homework (Elgenius et al., 2023a). However, little is known about the ways in which grassroots organisations emerge, evolve, establish services and ensure longevity, in conditions of superdiversity and socioeconomic challenge.

3 Materials and methods

Researching emergence processes is inherently challenging since grassroots groups must exist as an entity and be visible before it is possible to engage with them and once they are visible the nascent stage is likely to have passed. There are also particular difficulties identifying emergent grassroots actions run for and by minoritized populations where actors may operate “under the radar” (Elgenius et al., 2023b; Mayblin and Soteri-Proctor, 2011). To mitigate these challenges, we have used retrospective interviewing asking actors to narrate the life-course of their initiatives from a perspective of identifying ‘grassroots roots’. Retrospective interviewing, wherein respondents are asked to examine their original motivations for formation, the development, growth or decline alongside key moments, enabled the collection of detailed data about emergence narratives and processes. Retrospective interviewing is not without limitations particularly around individuals’ ability to recall emergent processes which is invariably selective. Scholars have highlighted problems associated with ‘moment in time’ approaches (Sundblom et al., 2016) and concerns around recall were partly addressed by ethnographic work wherein we spent months in the neighbourhoods and visited interviewees on several occasions. Several respondents from the same organisations were also interviewed to move beyond the “snapshot” data sometimes associated with one-off interviews.

This paper is based on data collected for a study focusing on how civil society contributes to integration in conditions of socioeconomic challenge and superdiversity. Four neighbourhoods were selected in two large post-industrial cities, Birmingham in England and Gothenburg in Sweden. Both cities have benefitted from the migration of workers into their former manufacturing industries and are home to residents from over 160 countries of origin. In Birmingham, the majority migrated from Bangladesh, India and Pakistan, and parts of the Caribbean whereas the largest migrant populations in Gothenburg originate from Syria, Iraq, Finland, Poland, Iran, Somalia, Afghanistan and the former Yugoslavia. These populations are internally differentiated by levels of education, immigration status and associated rights and entitlements. Both Birmingham and Gothenburg have experienced diversification processes in the last two decades with the arrival of many smaller and larger groups of labour migrants and forced migrants from across the world.

The four neighbourhoods in our study share socio-economic challenges and have been described as deprived with, higher than city average levels of unemployment, lower levels of income levels alongside higher levels of diversity. In Birmingham, the neighbourhoods selected have amongst the highest multiple deprivation scores in England (Birmingham City Council, 2019) and in Gothenburg the neighbourhoods have been classified as ‘especially vulnerable’ to crime by the Swedish Police (Söderström and Ahlin, 2018). England and Sweden sit within the context of different welfare states, wherein successive UK governments have, in comparison to Sweden, prioritised self-help in the face of austerity measures and reduced investment in the welfare state. In addition, Sweden favours a membership approach to civil society including grassroots activity (Papakostas, 2011) whereas England tends to rely heavily on volunteers (Mccabe, 2017).

The data collection for this study was undertaken between 2019 and 2023 with help of micro-mapping techniques to identify informal/formal civil society activities by following and tracing information available from local notice boards, webpages, signage and word of mouth, conversing informally with local residents and actors and participating in local events and meetings. A purposeful sampling strategy was undertaken from a local neighbourhood perspective and registered organisations and their leader(s) were approached in person, e-mailed or telephoned to request an interview whereas informal initiatives were found through micro-mapping and other actors. The researchers have experience of interviewing in conditions of socioeconomic challenge and superdiversity, which informs their reflections and observations in the field. The authors collaborated with representatives of organisations and local communities which in some cases have included co-researching (Elgenius et al., 2023a; Elgenius and Aziz, 2024; Pemberton et al., 2023).

The same topic guide was utilised in both countries. However, the nature of civil society makes a flexible approach necessary where some topics would be investigated in more detail and for this paper the saturated category was “emergence narratives” and processes along the lines of what Charmaz (2015) calls theoretical sampling, to make sure organisations at different stages and junctures were included. The data used for this article are constituted by interviews with founding member for 24 organisations particularly selected for their suitability to analyse emergent processes, actors’ motivations, resources used and ways of working, since interviewees retrospectively recalled and narrated the emergence stories of their organisations. We refer to emergence narratives since we recognise that the organisational histories told reflect the narratives of emergence the founders chose to tell or recall rather than our observations of emergence.

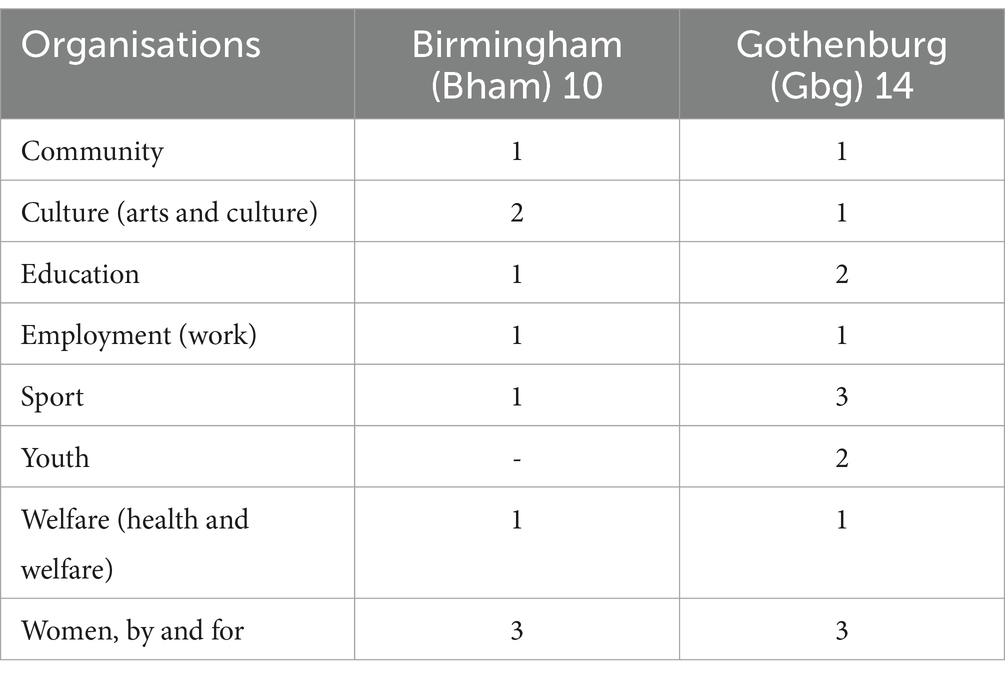

Of the 24 founding leaders the sample comprise 12 female and 12 male; 14 are of the first generation migrants and 10 are children of migrants born in England/Sweden or without a migration history. The selected civil society initiatives had been established between 4 and 29 years. At the time of writing 22 of the 24 initiatives had formalised although remained relatively small in scale and all had less than five full-time equivalent employees. All initiatives spent time as unregistered grassroots initiatives before transitioning into small-scale registered organisations. Below (Table 1) we categorise the actions undertaken into eight types of activities focusing on the community as a whole, culture, heritage and arts, education and employment, welfare/health and sports. We include the categories ‘youth’ and ‘women’ for organisations that work especially with these subpopulations. Notably, many of the organisations are multipurpose [see Elgenius (2023)] and work to provide several different activities for instance, the two community organisations in the table below also work with advocacy, culture and education, employment and youth.

Interviews were undertaken in English and Swedish then transcribed and translated where necessary. The analysis identified narratives around emergent processes of relevance such as actors, resources utilised and ways of working to start-up and sustain actions.

Ethical approval was granted by relevant ethics review committees in England and Sweden. Interviewees signed consent forms and could withdraw from interviews at any time. For purposes of anonymity, we have excluded details of interviewees’, their country of origin and the names of the neighbourhoods and organisations using instead action focused pseudonyms. Thus, in text we refer to the activity by main purpose, city and number (where relevant). For example, CommunityBham and CommunityGbg denotes two organisations that works to promote local community work in Birmingham and Gothenburg.

4 Results: narratives of emergent processes and the nascent phase

This paper seeks to address gaps in knowledge by identifying common aspects of narratives about the emergence processes of organisations in superdiverse areas that face socioeconomic challenges, and is not offering a comparison between different opportunity structures in England and Sweden. Instead, we explore narratives of emergent processes with a focus on actors, resources and ways of working. We commence by highlighting that all organisations featuring in our analysis started as grassroots actions run for and by local people and sought to address different gaps in mainstream welfare provision. The period between initiation and formalisation varies between a few months to many years, for instance WomenGbg1 took 3 years to register, EducationBham took nine years whereas WomenGbg3 have no plan to formalise and acts as a collective of leaders.

4.1 Actors

All but four founders resided in the neighbourhoods in which their organisations are based and had arrived as migrants or were children of migrants. The majority of founders were familiar with the geography and population diversity of the area, one of several important factors in their gaining legitimacy as ‘insiders’ (Basir et al., 2022). Interviewees explained their desire to address ‘local problems’ and challenges and how they eventually encountered other actors with whom they shared objectives and, as Carman and Nesbit (2013) suggest, shifted focus from unmet individual needs to identifying a larger cause and forming a group (Lejano et al., 2018). Interviewees explained they wish to give something back to their local communities, contribute to the lives of minoritised populations and resist destructive narratives and stigmatisation.

In England, EducationBhm was founded in 1980s by a small group of teachers from various minority groups wanting to improve the life chances of local children. One of its leaders registered the organisation in the beginning of the 1990s and described herself as connected to the local area. She witnessed her migrant parents going through difficulties she later observed among newcomers to the area and was keen to contribute so they would have a better experience than her parents. She established the organisation leaning on her local knowledge, insider status and lived experience:

I think coming to England as a 10-year-old as a refugee of Anonymised, and then watching my parents struggle, I think was a big motivation… My mum struggled; she had no English… She was widowed young because of the stresses. My father could not get a job although he was a bespoke tailor for Anonymised and he spoke English. The racism was really quite high… She (my mother) managed, and she managed on family credit, benefits, and all her children went to university. (EducationBham).

Likewise, other local organisations, such as CommunityBham, WelfareBham and CultureBham2 were all founded by local people. They emphasise their close connection to the area, their experiences of growing up locally and the difficulties faced by local people. Addressing those ‘difficulties’ was core to these organisations’ identities including mitigating disadvantages in “the intolerable areas of poverty in the hearts of the inner cities” and with reference to “the extreme inequalities in wealth and status” (WelfareBham).

Several actors were motivated by informal reciprocity (Phillimore et al., 2018) and the wish to repay the help they had once received from other actors, organisations or local populations when they originally moved into the neighbourhood. Another founder emphasised that “it is instilled in us from a young age, so it is about respect, about giving back, and how you are with people.” (CommunityBham). Another founder of WelfareBham recalled how he was helped to fight the attempt to remove him from the UK in the 1970s. Subsequently he contributed to anti-deportation campaigns of undocumented migrants and originally established an organisation to give something back to the ‘community’ that had helped him decades before.

In Sweden, EducationGbg1, was initiated by local fathers who wanted to improve their childrens’ educational achievements. The founder described turning to a well-networked local faith actor who together with a local housing company were able to offer a space for supplementary educational activities. The founder described how this organisation’s focus also shifted from individual to collective needs:

We discussed back and forth; how can we give our children the possibility to manage elementary school and to get in to High School? It is known that children in the area we live in does not… Then we contacted some authorities that could support and asked if they could help us with facilities and with support for actual homework assistance by hiring (university) students (EducationGbg1).

Anther organisation, EducationGbg2, was also initiated by local men. The interviewee described connecting local children with graduates and teachers familiar with local challenges who offer a few hours each week to help tutor local children:

We have the same experiences and have had the same stuggles or problems in life that these people have, and we can better identify with those we help (EducationGbg2).

Responding to experiences of disadvantage was a core motivator for all organisations and echoing the experience of inequality as the key motivator for action (Gurr, 2015). Several organisations sought to improve opportunities for children. Actors in Birmingham and Gothenburg said they were motivated by inequalities, unequal opportunities and the fear that children would get involved in the drugs trade. Moreover, challenges that motivated organisations include overcrowding, unemployment and low educational attainment. One leader of EducationGbg told of an encounter with a 14-year-old who told him to “fuck school” and explained that “the school was not for local kids.” This incident made him realise he had to do something for young people in the area to hope for a future. The founder of YouthGbg1 recalled how one of his relatives “took the wrong path” causing their family huge distress. He decided to generate alternative paths to aid young people who felt they had little choice but to engage in criminality. These grassroot initiators and those running sports associations (SportGbg1,2,3) all highlighted the need for local people to engage in physical activity and “to keep young men out of trouble.”

Actors in both cities recognised that large families could not afford to pay tuition fees and club memberships and that overcrowding meant children have no place to study within their own homes, which stands in stark contrast to the compulsory schools’ compensatory aim (Elgenius and Aziz, 2024). A leader of EmploymentBham had previously worked in various roles wherein which they learned that many local people could not afford to eat. They decided to help local people to work toward employment because “having a good job would help people have better lives.” Similarly, EmploymentGbg explained they decided to create opportunities and local internships for women without work experience to build their confidence and experiences in being able to work.

In Birmingham some founders describe being motivated by the desire to highlight gaps in welfare provision for minoritized populations and to mitigate institutional neglect of their neighbourhood. Organisations said they pushed back against racism and sought ways to celebrate their wide-ranging cultures and to rebuild self-esteem in the face of the discrimination they faced in the 1970s and 1980s. For instance, WelfareBham and WomenBham2 described how they originally sought to address inter-racial and inter-faith tensions by connecting individuals from different faiths to run activities seeking to heal rifts generated by the Partition of India or new patterns of settlement (Connell, 2019). Today, these organisations continue to be motivated by the lack of recognition and representation, a matter articulated by a leader of CultureBham1 who lobbied the local authority to involve their local community in consultations about local policies in a similar fashion to the longer-established communities (Elgenius, 2017). In Gothenburg, the many volunteers of WelfareGbg worked to attend to the health and welfare of refugees and undocumented migrants. Representatives of EducationGbg1,2 identified with communities that had arrived relatively recently and wanted to challenge the stigmatisation of the neighbourhood (as well as their ethnic groups) and specified that they wanted to address the racism they experienced in the local media, and by the Police and other authorities. Their motivations reflected those identified by Peucker (2021) when studying small-scale Muslim activism.

Several actors mentioned that they wanted local people to appreciate their neighbourhoods. Organisations such as CommunityGbg emerged around the desire to “flip the narrative” of deprived neighbourhoods by focusing on local achievements. The founder of CultureBham2 mentioned they sought to showcase the achievements and richness of local cultures and heritages of their residents. CultureBham1 wanted to highlight the culture of particular ethno-national groups by putting on exhibitions of minority artists, enabling migrants and minorities, to take pride in their culture and the founder explained:

My father came here to service the Industrial Revolution, he worked in the manufacturing sector, I am a son of the Industrial Revolution and here not by accident. By right, I own this place, this is mine by right and it is really, really important for us as people of colour to understand that we have contributed. (CultureBham1).

Similarly, CommunityGbg wanted to push back against the stereotyping and the stigmatisation of their neighbourhood. The founder of YouthGbg1 explained he began voluntary work as a teenager by “helping out” and later sought to encourage a sense of pride and belonging in the neighbourhood as residents had said they were ashamed to admit where they lived. The founders of two organisations for and by women, WomanGbg2,3, wanted to work against the “vulnerability” label and labelling of 61 areas in Sweden as vulnerable/especially vulnerable to crime, including the description of their neighbourhoods being “resource-poor” (BRÅ. The Swedish National council for Crime Prevention, 2017; Elgenius, 2023). The most recent list identified 59 areas with varying degrees of vulnerability (The Swedish Police, 2023). One of the founders explained that she had been inspired by the realisation following a fire and bereavement, that local people could mobilise to help other residents in moments of crisis. This organisation thereafter sought to empower others to make a difference without relying on help from outside actors. Such an approach was also exemplified by CommunityBham which organised a Garden competition to provide free vegetation for people to plant around the neighbourhood to improve their environment.

In both cities, founders recalled their desire to make life better for local people to settle and enjoy life. Many interviewees told of their parents’ arrival experiences and drew parallels with newcomers currently struggling to make sense of new systems and languages. Several organisations, EducationBham, EducationGbg1, EmploymentGbg, WelfareBham, WomenBham2 and WomenGbg1, also addressed the isolation of migrant women who lacked opportunities to engage in work or education. These organisations adopted what van Lunenburg et al. (2020) describe as a social constructivist approach to find ways to improve the lives of local women. Founders explained that they were motivated by seeing female relatives and neighbours suffering in improverished conditions or controlling relationships and wanted to empower women of all ages, promote gender equality and ensure more equal opportunities for the next generation. Young women of the second generation especially worked to support older women who faced challenges and explained:

These women usually live in destructive relationships where they do not have a lot of say. Not destructive in the sense that they get beaten or hit or anything like that but that power is unevenly distributed, it is unequal, it is the man who holds all the strings. There are women who have no education at all…There is usually some sickness…we create a sense of community and feelings of sisterhood. It feels like we are changing the view of women and the generations (of women) we have in front of us. We are changing the views of women themselves. We are breaking new ground. (WomenGbg1).

WomenGbg1 and WomenGbg2 focused on the inclusion and social integration of the first-generation women and and EducationBhm and WelfareBham on activities where women would learn English and develop social networks, having noticed that mothers became isolated and depressed after their children left home.

4.2 Resources

The resources utilised by actors and founders took multiple forms. Interviewees connected across local actor-worlds (Sillig, 2022) with others who share similar ideologies or visions for the neighbourhood and moved from acting on individual interests to establishing or joining group actions (Martens et al., 2021) and building on various forms of capital. As Edwards and McCarthy (2004) argue it is important to identify resource mobilisation at this early stage, alongside the various forms resources take and the ways they are used.

Founders explained that they relied on volunteers as one of the organisations core resources. Organisations’ internal actor-networks (Hatzl et al., 2016) also comprised connections to external networks of local professionals who possessed skill-sets or knowledges that founders saw as important to addressing their objectives. Those working with young people said it was important to access professional teaching staff. For instance, one of the leaders of EducationGbg1 remembered meeting an ex-teacher who was “down and out” and he paid her to teach his children English and Swedish, before mobilising collective resources through extended networks to pay university students by the hour and establishing EducationGbg1 with other local actors. EducationGbg2 also used volunteer teachers, university students and academics for homework and mentoring. CommunityBham explained that they appealed to local teachers to volunteer two hours per weekend to help local children and EducationBham1 asked professionals to volunteer to teach English. Once these founders formalised their actions they sought funds to pay teachers on a sessional basis. CultureBham1 used the European Commissions’ Erasmus programme to find interns from European universities who worked with them for months at a time. EmploymentGbg and EmploymentBham developed volunteering programmes, wherein the latter worked with the private sector to tutor people to be successful in job interviews:

…we also have a very strong corporate volunteering programme, where we have groups of business and professional men and women from businesses across the City, who will come and spend a day or half a day at Anonymous supporting our clients. (EmploymentBham).

The volunteering profile of those leading and initiating grassroots organisations in both Birmingham and Gothenburg appeared to be considerably younger than the age of volunteers working in larger formalised organisations (Cattan et al., 2011). Interviewees told us that young people were motivated to make a difference locally, and that they had seen civil society organisations help their parents and now wanted to reciprocate. The founders of youth organisations described contributing toward training local people to become sports coaches. These young people became role models as others locally began to follow their example and see volunteering as desirable.

Founders outlined relying heavily on networks, and connections with other organisations and authorities but stressed that their engagement with authorities needed to be framed on their own terms. EducationBham and EducationGbg1 said they worked closely with other local organisations who were invited to “reach in” and raise awareness about issues such as FGM, domestic violence and addiction, utilising the local organisational ecosystem to build their own capacity and expertise. Several organisations also connected to local faith organisations, local schools, libraries and housing companies to publicise their services and to secure access to premises, volunteers and donations. EmploymentBham connected to the financial corporations in Birmingham and acted as a conduit for donated interview clothes and advice from these partners.

Well if people cannot afford to put food on the table, how are they going to be able to afford to buy interview clothing to go and make that first impression count in a job interview. So, it was my aspiration to talk to some of the businesses that collect food for the food bank. I wanted to say, if you are collecting food, could you collect smart workwear as well, so that we are able to provide support for some of our clients that are going for job interviews (EmploymentBham).

Echoing the claims by Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (2019) regarding the distinctiveness of grassroots actions, founders explained how, at the beginning of the lifecycle, they adopted specialised, strategically innovative approaches to overcome resource constraints. Lack of space to house their organisation was a key difficulty even for well-established organisations. The absence of a formal structure and premises led actors, particularly at the early stages of their work, to borrow spaces or identify free spaces in which they could operate. Interviewees used their external actor-networks to help access material and symbolic resources (Hatzl et al., 2016). WelfareBham recalled finding an empty shop and asking the owner if they could use it as a base, while many other organisations such as EducationGbg1, WomenGbg2,3 and YouthGbg1,2,3 approached local authorities, churches, schools and housing companies to ask to use their premises. During start-up phases, founders said that spaces to meet were changed regularly depending on opportunity and demand. Founders communicated with local people by social media to ensure that users knew where to go. CommunityGbg highlighted the timeconsuming nature of “finding a room” or, rather, “a proper meeting place” before any activities could take place. As the organisation highlighted, having a space would mean “we can have more people coming and going and helping on the activities.” (CommunityGbg).

Organisations also said they used donated items to help deliver services. EmploymentBhm realised they could use existing foodbanks as hubs to collect clothes to distribute to local people. WelfareBham used donated furniture to furnish their donated premises and took turns to provide tea and coffee. WomenGbg3 said they shared the costs of food between them and WomenGbg1 contacted local companies or approached friends or wealthy donors to fund specific items. Founders also recalled receiving unsolicited offers of large donations which enabled them to, for example, run a festival celebrating the diversity of the area. Several organisations also turned to external national, regional or local sources to apply for funding once they were formalised.

Food featured heavily as a resource in the organisational emergence narratives and as a resource to bring people together and help raise funds or reward volunteers. Several of the women’s organisations played to the abilities of local women who were skilled cooks. The founders of WomenGbg3 typically organised activities around donated food preparing and selling meals and using the money raised to fund projects in their countries of origin and to help local families encountering hardship. One of the founders started their grassroots organisation by helping a single family in need. They soon realised they could run bigger events and help more families. They recalled how they scaled up during the pandemic:

We were asking; what can we do to help these families? We’ll get them food for three, four, five days…They do not have to worry. We’re the ones who do the cooking. We contribute with what we can. We buy and shop so that there is food, because that’s, like, the worst thing. You do not have time to buy food when you are grieving. (WomenGbg3).

Food from different cultures was also used as a resource to attract “outsiders” into the neighbourhood and draw attention to the work undertaken locally by civil society actors. WomenGbg2 explained that running multicultural food events helped to build networks with authorities who were invited into the neighbourhood and shown a positive alternative to the stigmatised stereotype of “vulnerable neighbourhoods.” Several founders of groups run by, and largely for, women explained how they utilised emotional labour to address local problems and often responded to crises with love and care alongside offerings of food. In the pandemic their ability to raise funds by cooking for events was reduced but volunteers nonetheless went into the homes of the sick and dying, to offer help. Other organisations realigned their activities to respond to “food poverty” establishing food banks to “provide food to 100 families… referred to us through schools and churches, charity groups.” (CommunityBhm).

In Sweden, associations often charge “symbolic” membership fees, but several organised around loose groups of volunteers did not charge people using their services. Others such as YouthGbg1 and SportsGbg1 stated they collected “symbolic” fees to pay for material and sports equipment and stressed their fees were “the cheapest in Gothenburg.” EducationGbg1 described charging fees significantly lower than for the cost for private tuition and funds from the council and other bodies were used to pay tutors and arrange trips during school holidays. WomenGbg1 mentioned they raised funds by producing and selling products or running events, charging entrance fees for cultural events and selling their own cookery books but that they no longer found it is useful to charge membership fees:

We have taken the membership payment away. We start the annual meeting with a big food-fest, and everybody brings his or her own food and they are very generous, there is a lot of food. This makes more sense … and you can contribute in different ways. (WomenGbg1).

Having said this, external funds and membership fees also enabled some organisations to pay for staff and eventually core staff such fundraisers able to raise more funds to increase the capacity to support local people.

Over time, which in some cases could be decades, founders said that their organisations built a reputation for being effective. They learned how to navigate the local funding environment. Some turned to private or commercial donors for requests. Others were able to access small pots of money from local or national grants and run events or activities. Others secured service level agreements in which they were paid to deliver specific services to the local population. Some organisations such as CommunityBham secured sufficient funds to rent or buy their premises, whereas EducationalGbg1, YouthGbg1 and CommunityGbg were offered premises in recognition of their effective work collaborating with local housing companies and other local civil society organisations.

4.3 Ways of working

Sillig (2022) argues that a defining feature of grassroots innovation is the distinct ways in which such organisations work. Together with other key features, their ways of working stand out when action is initiated from the bottom up (Hossain, 2016) such as reframing neighbourhoods as “not-bad” (Cajaiba-Santana, 2014) or resisting structural violence from the police. Grassroot actions are also, as noted by Batliwala (2002), typically grassroots when aimed at the most disadvantaged populations most seriously effected by the lack of material and other resources. All organisations described distinct ways of working in line with their motivations, ideology and the local context (Suykens et al., 2019). The particular mix of geography, available resources and networks at the formation stages combined with the values and beliefs contributed to founders’ ways of working which we describe below.

The founders, in the absence of core funding, described their ways of working suggesting they were consummate bricoleurs (Phillimore et al., 2021). They described combining resources available within the neighbourhood in different ways to meet long-term unaddressed and emergent needs. Founders made creative and opportunistic use of space, food and volunteers shifting away from the more normative use of funds generally viewed as core to the operation of civil society. All founders described examples of actions which might be considered bricolaging. Several organisations said they paid for “talented” and “motivated” local people to take coaching courses which facilitated the development of a volunteer and leadership supply chain [see also Mathie and Cunningham (2003)]. For example, the founder of YouthGbg1 invited young residents to join as interns, trained them and then employed them on a sessional basis. CultureBham2 paid for volunteer training in specific skills such as badminton coaching and Zumba. Once qualified, individuals were expected to offer a few free sessions to repay the organisation and were then paid on a sessional basis for additional classes. SportGbg1 compensated volunteers for their labour by providing free access to training. Volunteer coaches and their children could join for free, receive free sports kits and receive meals donated by local restaurants. Coaches were said to develop a sense of companionship through eating together which further enhanced their loyalty to the cause. One founder explained:

We see our area as a village. As having the quality of a village. That is, we see young people, we train them, we make sure they become good leaders, we employ them at Anonmyous, we give them a formal title, a place to start, where they are youth leaders, they are role models. When you do this, you lift … and you inspire the other young people for the future. You give them a goal, and someone to look up to. (YouthGbg1).

WomenGbg2 recalled a mix of actions that might be described as bricolaging over many years. Despite their identification of a need to address high levels of domestic violence locally, without core funds they were unable to run a regular programme of activities. Building on lived experience and insider status, they argued that they understood the necessity of operating in ways that were not threatening to some local men and sought other organisations to reach-in and share or pool resources, for example asking a traffic safety agency to teach women to ride bicycles, facilitating their mobility and reducing their reliance on male relatives. CommunityBhm collaborated in a similar vein with SportBhm saying that teaching women to ride a bike increased their mobility, health and “challenged stereotypes.” WomenGbg1 also described using whatever resources they could mobilise to address gaps in welfare provision for local women. They used their own skills of dancing, cooking, and translation to attract local women, supplementing these with others’ donations and resources, running events with whatever was to hand. Many actors described the ways in which they used creative agency by utilising new spaces or practices to meet challenges (Luthra, 2018). In the absence of adequate resources, premises or websites, founders said they used social media to promote ideas and to communicate with local residents. YouthGbg1, for instance, made You Tube videos to share messages to counter the “drugs culture.” Similarly, EducationGbg1 and WomenGbg1 communicated with their volunteers and users via WhatsApp and Viber and advertised their services via Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram. Informal initiatives such as those run by WomenGbg3 relied entirely on social media for communicating and mobilising mothers to provide support to others in need.

Many of the founders and interviewees described themselves as “local champions” and some expressed an intense dislike of the term “community leader” for various reasons. CultureBhm2 resisted the label “community leader” on racial grounds arguing the term has become ethnified and used to essentialise minoritised populations. A founder of CommunityBhm also highlighted there were many “so called” and “self-proclaimed community leaders” who “actually did not do much” or built their own power base. Founders and interviewees therefore argued that rather than lead, they sought to empower local people to improve their opportunities. A founder of CommunityBhm suggested they were “community champions” using a “local/community asset-based approach” in which local social capital and participatory activism were utilised to promote change and decisions were made through participatory actions:

We voted in the community, and said okay, this is what we are going to take forward. So (prioritising) children and young people is one of them. With a very specific focus on more provision for young girls, because a lot of the provision out there … is very male dominated. (CommunityBhm).

This local asset-based approach, although not always labelled as such, was evident in several organisations. CommunityBham described conducting listening exercises with local people to identify priorities while YouthGbg1 responded to direct requests and suggestions from parents.

The founders interviewed may also be described as social engineers (van Lunenburg et al., 2020) as many said they tried to break away from existing institutional contexts and establish a new agenda and way of doing things. Interviewees often sought to counter the bureaucratic service delivery models which they saw as incapable of meeting the needs of local people and sometimes even having a deleterious effect by labelling local people according to ethnicity, gender or neighbourhood. The approach they adopted were said to be person-centred and flexible. The founder of EducationBham highlighted the importance of connecting with people over the long-term stating that users may also need many years of emotional support. The founder described how funding would typically be specified for education or improving qualifications and restrict the organisation’s possibilities to provide “recreational projects,” “softer projects or support” and nurturing “the emotional need” the organisations had specialised in supporting. Using funds efficiently and drawing on various resources and surpluses meant the organisation could arrange activities deemed necessary and important for users.

WomenBham1 also spoke about using a holistic approach to nurturing users, in this case migrant women, and highlighted the length of time it took to identify and “amplify” their strengths. Approaches adopted appeared to be value bound (Florian, 2018) with actors saying they engaged with individuals because of care and concern for their wellbeing. WomenGbg1 said they sought to identify and build on the skills of older women in order to build their self-esteem. Such micro-actions they argued could challenge gender norms by showing local men that “women have backbone.”

Some organisations had moved on from being emergent small-scale initiatives. We found that scaling (van Lunenburg et al., 2020) occurred in different ways and was rarely part of a strategy to expand or increase power. Instead, scaling was articulated as a desire to help more people. Organisations such as YouthGbg1 scaled out to new geographical areas and implemented their models in other neighbourhoods in conjunction with other actors in those places who had been inspired by their approach and invited them to come and assist. EducationGbg1,2 set up spin-off activities in nearby neighbourhoods and EdcuationGbg1 expanded to provide homework clubs for adults. They and WomenGbg1 recounted receiving visitors from other cities, who wished to learn from them and replicate their approach. CultureBham2 retained its neighbourhood commitment but scaled beyond its original foci which promoted the heritage of the area and began addressing health problems. YouthGbg1 scaled out by petitioning local politicians demanding that they witness the way they had transformed the neighbourhood. Having convinced politicians that they had been able to engage local youth, YouthGbg1 was offered core funds and premises as policymakers sought to replicate their approach elsewhere. WomenGbg1 actively recorded their successes so they could prove to authorities and sponsors that they were effective. Similarly, another organisation in Birmingham transformed their ways of working into a social enterprise enabling them to “promote” their relational approach across the city and convince authorities that their way of working should be part of the municipal offer to all newcomers. During the pandemic this social enterprise also collaborated with health professionals to promote better healthcare locally:

The main thing is that they (the health service professionals) do not have relationships (with local people) and if you do not, you do not have trust and you are not gonna be able to speak to people… I understand, you cannot build a relationship with every single patient, but you are gonna be able to build relationships with at least key individuals in a neighbourhood which they have not done.” (CommunityBham).

All of the organisations interviewed began their organisational life as grassroots organisations. But not all organisations reached all points of the non-profit lifecycle phases and stages (Andersson et al., 2016; Mitchell, 2019). While some followed the typical lifecycle others did not. For instance, WomenGbg3 operated as a network collective to provide support to local people. They expressed no intention to formalise or to grow. In fact, the organisation was described as very fluid with leadership coming from those who had time to lead at different moments and in the face of different situations. The work they did also depended on the extent of volunteer participation and available resources which ebbed and flowed. EducationGbg2, YouthGbg1 and CulturalBham2 on the other hand appeared to follow the organisational lifecycle to a higher degree by moving from an informal initiative to formal organisation, by expanding their scale and by showing signs of maturity, having established premises and developed strong relations with other local organisations and authorities.

Whereas these organisations were on the ascent other organisations we interviewed had seemingly declined (Andersson et al., 2016) or reached an incapacity stage (Mitchell, 2019). SportGbg1 tried and failed to expand their offer to girls and struggled to access volunteers as they found their best football players were recruited by other clubs. WomenGbg2 spent many years moving around in temporary rooms without offering a fixed programme of activities and their membership had declined by two-thirds over several years. WelfareBham and WomenBham2 were in crisis when their premises where first visited in 2019 and with their service offers hugely reduced since their heydays pre-2010 when they were well-funded. The models they had once used, accessing regeneration funds, were obsolete in the new political environment of austerity measures wherein civil society organisations were expected to provide services and operate under specified contracts rather than apply for funds to run projects. Further, their innovative ideas, to open a refuge and care home for minoritised women and elders, had been mainstreamed by, for instance, housing providers with greater capacity. By the time we returned to the neighbourhood post-pandemic these organisations had closed. However, other organistions such as CommunityBham and EmploymentBham were surviving in the new funding environment but without the core funds they had previously received. At the time of our interviews, they were entirely dependent on tendering for funds to deliver services. Much time was spent on funding applications which reduced their ability to be creative and perhaps had to compromise their original objectives undermining their early motivations for action.

5 Discussion

This article has contributed new knowledge about narratives of emergent processes of civil society organisations in superdiverse areas that face socioeconomic challenges. Below we highlight main points about the actors and founders who base their work on lived experiences and a shared vision to mitigate inequalities not addressed by mainstream services. Their creative bricolaging of local resources to achieve shared goals, building on the skills of diverse local populations in innovative ways, made it possible to develop value-driven assets-based approaches alongside flexible ways of working.

In terms of motivations, actors and founders recall how they were inspired to act in response to the failure of welfare states and to meet needs of local populations for instance in different areas of integration, e.g., by improving access to employment, welfare and support. Actors narrated their desire to support local people to overcome the harms generated by racism and problematised negative discourses of their neighbourhoods. Grassroot actions were often undertaken by local founders for local people often based on lived experience and insider knowledge and trust, key to identifying needs and gaining legitimacy. All these organisations were in their early grassroot stages, and adopted an inclusive approach (Burton, 2019), which sustained as they grew. Some actions were initiated by local founders who connected with the specific profile of their neighbourhoods. Starting from their own motivations, most initiators shared a vision with others and together formed outward looking groups displaying distinctive features of grassroots activism by shifting from individual needs to collective ones. In the early stages, governance tended to be participatory without formal structures and inspired by conversations with local people and with active attempts to consult the local population (Martens et al., 2021).

Suykens et al. (2019) notes how context shapes the goals, values and resources of grassroots organisation and we concur that the nature of the local area, its challenging socio-economic context and superdiversity shaped the actions initiated, the latter for instance with reference to refugees and undocumented migrants’ health and welfare. Founders’ desire to address the exclusion of other populations such as minoritised youth and women, also came from the recognition that needs were not addressed by mainstream services. Their aspiration to address unequal structures, discrimination and racism, was said to relate to the areas’ history of migration. In Sweden, a shared motivation was also the desire to push back against the label of being a “vulnerable area” (Elgenius and Aziz, 2024). Founders in both Birmingham and Gothenburg said their insider status gave them legitimacy and respect (Cannon, 2020) which was an important criteria for growth and sustainability. Lived experience and what we have called insider status enabled individuals to organise around a collective identity (Basir et al., 2022), being a migrant, belonging to the neighbourhood or to a particular language or faith group. The diversity of the local population was found to be a key resource used in innovative ways. Edwards and McCarthy (2004) highlight the importance of social networks, human capital and understanding local issues in small scale actions. Informal reciprocity as emphasised by Phillimore et al. (2018), and the willingness of local people to volunteer, to give back, and sharing resources were key to organisation’s emergence.

Traditional surveys of civil society participation would typically ask questions around donations of money or time from adults over the age of 18 (i.e., Initlive, 2021) and in so doing omit the wide range of resources found in the material of this study. These resources include borrowed spaces, donated foods, the efforts of young people utilised in the neighbourhoods and the mentoring of users into new leaders none of which would not have been recorded in a traditional survey and may constitute a distinct feature of grassroots action in superdiverse neighbourhoods. The emergent processes of grassroots innovation narrated and recalled by founders appeared to have shaped the identity and structure of organisations as they grew or formalized (Edenfield and Andersson, 2018). The desire to empower constitutes a key theme that developed into an assets-based approach and once formalised, founders continued to build on the capacity of local people, volunteers, paid employees, coaches, tutors and mentors.

Building on lifecycle theory our work suggests that processes of change can be described as evolution by opportunity and that opportunities evolved as founders responded to the availability of local assets and demographic change. Scaling out occurred when opportunities arose, through conversations with neighbouring activists and scaling up resulted from the ability to demonstrate to authorities that alternative approaches were effective and demonstrating legitimacy through delivery, which in turn could influence mainstream policy and practice. Such legitimacy work does not happen without risk and some organisations shifted their ways, working to contract directly with the state and appeared to lose their ability to innovate becoming dependent on all-encompassing service contracts. At the same time the failure to evolve could also result in senescence. The desire to generate change featured heavily in founders’ and actors’ narratives and several did eventually scale up and/or scale out. Their evolution supports the contention that rather than moving through a lifecycle wherein change occurs at critical junctures, innovation consist of gradual changes occurring over time and as new opportunities or challenges arise (Gåsemyr, 2015). Arvidson (2018) therefore argues that small-scale organisations should be conceptualised as movements because they constantly evolve.

Another key feature of grassroots innovation in the evolution of civil society was the ability to bricolage local resources to achieve shared goals. Organisations were, in their emergent phases, and for those who had not been subsumed into service level agreements at later stages, extremely flexible (Florian, 2018). As Fernández Guzmán Grassi and Nicole-Berva (2022) argue, tailor made support builds resilience in grassroots organisations. Founders’ ability to work with individuals, meeting evolving need, differentiated organisations from public sector services and reinforced the legitimacy of organisations by demonstrating authentic caring. In many respects founders operated as social engineers (van Lunenburg et al., 2020) through their accounts of attempts to secure change, either by demonstrating how things can be done differently or by lobbying for resources to enable a break with mainstream approaches to problem-solving.

In sum, we have shown how organisations beginning as grassroots actions utilised a wide range of resources to facilitate their work and evolving into larger scale organisations over time. The combination of lived experience, inside-knowledge and ability to mobilise diverse local resources enable organisations to attempt to meet diverse needs in areas facing socio-economic challenges. Given the reported importance of the nascent, grassroots phase in lifecycles, whether in securing legitimacy not possessed by the welfare state, or in being able to build connections across populations, it is important to think about how grassroots organisations might be supported to innovate, evolve and sustain. We argue that provision of small-scale flexible funds could help organisations to establish. Although formalisation is not always the desired outcome, support could be provided for those who wish to formalize. Organisations ‘insider’ status was said to bring insight missing from wider welfare provision too. Perhaps civil society organisations in superdiverse areas could be resourced to share some of their insight with other providers, helping to build overall capacity to meet diverse needs. Thus, our analysis of founders’ and actors’ narratives of emergence processes has shed light on how they describe the offerings of grassroots organisations in superdiverse areas that face socioeconomic challenges and highlighted their creative use of local resources, some of which relate to the diverse offerings available at neighbourhood level and value-driven and flexible working approaches. More research is clearly needed about emergent processes in different neighbourhoods and with reference to the crisis or incapacity stages of grassroots activities. Such work could also focus on the reasons why organisations fail, their limitations of resources or absence of legitimacy.

Data availability statement

The dataset presented in this article is not readily available following ethical guidelines and ethical reviews in England and Sweden and access is restricted to the research team.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Etikprövningsmyndigheten) for the University of Gothenburg and by the University of Birmingham’s Ethical Review Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded in part by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare FORTE (2018–00181) and the Swedish Research Council VR (2019–02167) Elgenius (PI) and Phillimore (Co-I). This manuscript is published under a Creative Commons CC-BY license as per funders recommendations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amanj Aziz, Surinder Guru, and Annsofie Olsson who have contributed to this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andersson, F. O. (2022). The exigent study of nonprofit organizational evolution: illuminating methodological challenges and pathways using a nonprofit entrepreneurship Lens. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 33, 1228–1234. doi: 10.1007/s11266-021-00391-1

Andersson, F. O., Faulk, L., and Stewart, A. J. (2016). Toward more targeted capacity building: diagnosing capacity needs across organizational life stages. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 27, 2860–2888. doi: 10.1007/s11266-015-9634-7

Andersson, F., and Walk, M. (2022). “Help, I need somebody!”: exploring who founds new nonprofits. Nonprofit Manag.Lead. 32, 487–498. doi: 10.1002/nml.21494

Arvidson, M. (2018). Change and tensions in non-profit organizations: beyond the isomorphism trajectory. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 29, 898–910. doi: 10.1007/s11266-018-0021-z

Basir, N., Ruebottom, T., and Auster, E. (2022). Collective identity development amid institutional Chaos: boundary evolution in a Women’s rights movement in post Gaddafi Libya. Organ. Stud. 43, 1607–1628. doi: 10.1177/01708406211044898

Batliwala, S. (2002). Grassroots movements as transnational actors: implications for global civil society. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 13, 393–409. doi: 10.1023/A:1022014127214

Birmingham City Council (2019). Deprivation in Birmingham: Analysis of the 2019 Indices of Deprivation. https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/downloads/file/2533/index_of_deprivation_2019

Borkowska, M., Kawalerowicz, J., Elgenius, G., and Phillimore, J. (2024). Civil society, Neighbourhood diversity and deprivation in UK and Sweden. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 35, 451–463. doi: 10.1007/s11266-023-00609-4

Bothwell, R. O. (2002). Foundation funding of grassroots organisations. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 7, 382–392. doi: 10.1002/nvsm.195

Brandsen, T., Trommel, W., and Verschuere, B. (2017). The state and the reconstruction of civil society. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 83, 676–693. doi: 10.1177/0020852315592467

BRÅ. The Swedish National council for Crime Prevention (2017). Utvecklingen i socialt utsatta områden i urban miljö 2006–2017: En rapport om utsatthet, otrygghet och förtroende utifrån Nationella trygghetsundersökningen. Report 2018:9. https://bra.se/publikationer/arkiv/publikationer/2018-06-29-utvecklingen-i-socialt-utsatta-omraden-i-urban-miljo-2006-2017.html

Burton, W. (2019). Mapping civil society: the ecology of actors in the Toronto region greenbelt. Local Environ. 24, 712–726. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2019.1640666

Cajaiba-Santana, G. (2014). Social innovation: moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 82, 42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2013.05.008

Campbell, J. L. (2005). Where do we stand? Common mechanisms in organizations and social movements research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cannon, S. M. (2020). Legitimacy as property and process: the case of an Irish LGBT organization. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 31, 39–55. doi: 10.1007/s11266-019-00091-x

Carman, J. G., and Nesbit, R. (2013). Founding new nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 42, 603–621. doi: 10.1177/0899764012459255

Cattan, M., Hogg, E., and Hardill, I. (2011). Improving quality of life in ageing populations: what can volunteering do? Maturitas 70, 328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.08.010

Charmaz, K. (2015). Grounded theory. In Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. ed. J. A. Smith (London, England: Sage) 3rd ed., 53–84.

Chetkovich, C. A., and Kunreuther, F. (2006). From the ground up: Grassroots organizations making social change. Cornell University, USA: Cornell University Press.

Connell, K. (2019). Black Handsworth: Race in 1980s Britain. Oakland, California: University of California Press.

Edenfield, A. C., and Andersson, F. O. (2018). Growing pains: the transformative journey from a nascent to a formal not-for-profit venture. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Org. 29, 1033–1043. doi: 10.1007/s11266-017-9936-z

Edwards, B., and Mccarthy, J. D. (2004). Strategy matters: the contingent value of social capital in the survival of local social movement organizations. Soc. Forces 83, 621–651. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0009

Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M. (2019). Competition and strategic differentiation among transnational advocacy groups. Interes. Groups Advocacy 8, 376–406. doi: 10.1057/s41309-019-00055-y