Abstract

Background:

The rich tapestry of student politics and movements in Bangladesh is marked by a history of significant contributions to the country's sociopolitical landscape. This study was prompted by a keen interest in exploring the dynamics of contemporary student movements at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University (BSMRSTU), Gopalganj, and their interplay with the broader sociopolitical climate of Bangladesh. A critical examination of these movements reveals a complex web of motivations, strategies, and outcomes that both mirror and influence national sociopolitical dialogues.

Methods:

Employing qualitative research methods, including in-depth interviews (IDI) with 26 individuals directly affected by the culture and mechanics of these movements, this study uncovers the nuanced ways in which student activism at BSMRSTU mobilizes cultural ideologies toward societal change. Purposive and snowball sampling techniques were utilized to select participants, revealing that the rhetoric of movements—framed around justice, rights, equality, and reform—plays a crucial role in recruiting and energizing participants.

Results:

However, this investigation also highlights a darker facet of these movements: the destructive consequences of specific actions, such as property damage, which not only impact the immediate community but also fuel further unrest. The prevalence of movements centered on themes of injustice underscores the urgent need for both governmental and academic institutions to engage more constructively with student concerns. Addressing this gap requires a nuanced understanding of the motivations behind student movements and a commitment to implementing policies that nurture a culture of dialogue and reform.

Conclusion:

This study, therefore, problematizes the contemporary student movements at BSMRSTU by questioning the balance between activism and the potential for unintended consequences, urging a reevaluation of how such movements are perceived and managed in the context of Bangladesh's evolving sociopolitical milieu. For harmful movement culture in academia to be prevented, government and university authorities must take student movements seriously and implement policies and strong norms.

1 Introduction

Students are a country's most forward-thinking, articulate, inspired, and energetic population (Tilly and Wood, 2015). Bangladesh's student politics and movements have a glorious past. Students in Bangladesh have a long and distinguished political tradition. The student body has a significant impact on Bangladeshi politics. Many politically aligned students are also preparing for future political office, creating a virtuous cycle linking political violence with party politics. The term “student movement” is widely used to describe widespread student participation in social or political activities throughout a given time. Generally speaking, secondary school, and university students participate in student movements (Dagnino, 2007). Typically, but not always, student movements are motivated by a desire to change the status quo and improve local society or politics (Bellei et al., 2014). According to UNESCO, there has been a notable rise in youth participation in worldwide social movements, mainly through student-led rallies, which have become an essential form of political action in the twenty-first century (Cabrera et al., 2017). These movements frequently emerge as a result of a shared aspiration among the student population to question and alter the existing state of affairs, with the goal of initiating transformative changes within local communities or political environments (Bellei et al., 2014). This advocacy is not only a response to present circumstances but rather a manifestation of underlying, systemic problems within educational institutions and governance systems that align with the more significant objectives of education.

Student movements have a broader impact than just achieving immediate political or social goals. They serve as a vital platform for younger generations to voice their discontent, provide alternative solutions, and actively engage in defining their future (Hodgkinson and Melchiorre, 2019). These phenomena have both immediate and indirect effects on societal norms and operations. Student movements can directly result in concrete changes in policy, educational reforms, and public attitudes toward governance and civic involvement (Rhoads, 2016). They indirectly promote a culture of critical thinking, democratic involvement, and social responsibility among students. Cultural transformation is crucial for the advancement of societies toward more inclusive, equitable, and democratic systems (Cole and Heinecke, 2020).

Furthermore, the significance of student movements in relation to the broader objectives of education cannot be exaggerated. They function as practical platforms for the implementation of civic education, fostering students' active involvement in analyzing and addressing intricate societal matters thoughtfully and productively (Bellei et al., 2014). By doing this, student movements compel educational institutions to contemplate their function in society and frequently propel the creation of more comprehensive and socially aware curricula. Thus, comprehending the intricacies of student movements, specifically in settings such as contemporary student movements at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University (BSMRSTU), provides a significant understanding of the interaction between education, societal transformation, and the quest for societal conformity in Gopalganj, Bangladesh.

In essence, the student movement is an expression of idealism. Students act on their ideals by seeking justice, the common good, and the empowerment of marginalized communities (Chan, 2016). Modern social movements were developed mainly with the emergence of nation-states to pressure governments to enact laws according to the demands of different country groups (Weldon, 2012). Social movements can influence political decisions, put emerging issues on the policy discussion, and pressure policymakers to enact policies (Kingdon and Stano, 1984; McAdam and Su, 2002).

Following the “frame of analysis” perspective, the analytical process has been able to incorporate symbolic and interpretive elements, with a primary focus on the cultural sphere. In this study, we use the highly controversial term “culture” to refer to the actions of the social movement and to understand the dynamic qualities of the resulting political culture. People often express their discontent with authorities, press for fundamental human rights, and defend their right to vote through social movements and protests (Snow et al., 2008). As a foundation for the analysis, it is essential to quickly describe Bangladesh's socio-political character and existing culture of student movements regarding current trends in university student movements. In the last few years, social movements such as student movements have experienced a new turn globally and in Bangladesh. Due to several student protests at different times, Dhaka's significant roads are typically confined to traffic. For this, everyone is scurrying on foot to get where they need to be (The Daily Star, 2018). In the name of student movements, unruly students and mobs rallied unlawfully, armed with homemade weapons, destroyed vehicles on the road, set cars on fire with petrol bombs, and harassed and beat passersby (The Daily Observer, 2015). The Bangladeshi student movement blockages would generally begin at 8 a.m. and end at 8 p.m., making it impossible to go about the city because of the prolonged blockage lasting for most of the day. Traveling away from home frustrates most people (The Daily Jugantor, 2018). When students are restricted from moving, they block roadways by burning tires and plastics. Furthermore, the student movement has resulted in severe traffic congestion (Bangla Tribune, 2021). In addition, because of Bangladesh's movement culture, legitimate violence, and the influence on social normality, the impact on the lives and employment of ordinary people held hostage by the demonstrators was more significant.

Bangladesh has experienced many movements since its birth in 1971 (Patwary, 2011) to meet the demands of different needs and rights. Interestingly, in the last decade, student movements in Bangladesh have been distinct and included quota reform, the Shahbag movement that demanded capital punishment for war criminals of the 1971 liberation war in Bangladesh, road safety, and anti-Vice Chancellor student movements at BSMRSTU, Jahangirnagar University (JU), Barishal University (BU), and Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST). Most movements took place in Dhaka's capital city and spread nationwide. Although numerous newspaper articles and blog articles have been published based on such movements, there is no sociological perspective on the movement except some newspaper articles and some Bengali books, which are only personal deductions of the authors. Research on social movements has usually addressed movement emergence and mobilization issues, yet more attention needs to be paid to their outcomes and consequences. More student movement-related literature needs to be published in the context of Bangladesh. Previous evidence shows that most Bangladeshi papers focused on specific movement dynamism, the role of media, and socio-political contexts (Patwary, 2011; The Daily Star, 2018; Al-Mamun, 2023). In the current discourse, the majority of research emphasizes the political and policy outcomes of movements, while fewer studies delve into their broader cultural and institutional effects. In light of this context, this study aims to explore the rhetoric of movement culture of contemporary student movements at BSMRSTU, examining justified violence and its impact on social normality in the Gopalganj district of Bangladesh. Hopefully, this work will bridge the gap between the scarcity of literature on student movements and their mechanisms for determining the influence of human existence as a captive of student movements in Bangladesh.

2 Contextualizing movement rhetoric and the cultural repertoire

This study examines a popular form of ideology: discourse on the “public” or “common good.” The claim to the common good is often implicit, but we differentiate public good rhetoric from “interest-group” or “constituent benefit.” The claims instead center on what is required to establish a decent and just society, with how this society safeguards the common good left unsaid. Our primary worry is how the cultural context from which movement frames are drawn affects the substance of those frames (the specific appeals to action and change). The movements under consideration here use public good language, like any ideological argument, to attract members, persuade bystanders, and neutralize opponents (Richter et al., 2020). The public good is an essential but nebulous political symbol that is hard to define and fight for McAdam et al. (1997). Challenger movements, which have less solid ground to stand on, benefit significantly from generally accepted vocabulary such as the public good. However, the precise nature of any public good vision could be more evident; indeed, it is often left purposefully nebulous to smooth over disputes between various movement factions and potential supporters. According to Tilly and Wood (2015), political movements have a limited (but not entirely unrestricted) “repertoire” of collective actions at their disposal. While the repertory renders some activities impossible (regardless of how likely they are to be effective), it also provides a readily interpretable blueprint for insiders and outsiders to the movement. It informs the public on the movement's “up to” in the political sphere (Jackman, 2021).

In social movement politics, the accessibility of cultural assets becomes particularly apparent. Social movements are “challengers” that are often compelled to resort to non-institutionalized tactics of obtaining political power (Gamson, 2013). It is more typical of “interest groups” than “social movements” to engage in compromise deal-making and back-room negotiations, which demand resources different from public politics (Useem and Zald, 1982). It is common knowledge that movements struggle to maintain public resources through behind-the-scenes politics (Benford and Snow, 2000). Cohen (1993) shows how controversial the public good can be by analyzing political disputes over local economic development. Both camps claim to represent the interests of the greater good (or “community”) while presenting the other side as motivated solely by self-interest. Both groups see “community” as a desirable concept, but definitions vary widely depending on the participant—a “morally dubious” idea (McAdam et al., 1997). Simply put, the rhetorical methods of social movements have both internal and exterior effects. In order to inspire people to take action, movement groups must develop persuasive ideological arguments. Concurrently, legitimate cultural resources as a channel for power are necessary for entry into public political arenas. To grasp the cultural assets of movements, we must first investigate the connections between macro-level cultural environments, collective action frames that are likely to be successful, and the interpretive meaning-work done at the meso-level by individual movements.

2.1 Student rhetoric in BSMRSTU movements

The student movements at BSMRSTU speak from a place of profound social justice, equality, and the need for academic liberties. Through the perspective of collective action, students express their complaints by viewing their conflicts as a more significant battle against what they regard as injustices within the university system and, consequently, in the social structures of Bangladesh. Slogans such as “against systemic oppression” and “for the betterment of the student community” often appear in their speeches, suggesting that they are united in their opposition to societal and institutional injustices (Al-Mamun, 2023). In response to insensitive or abusive administrative procedures, students who take part in the movements justify their activities saying they are necessary. They portray themselves as change-makers in their discourse, standing up for both their rights and the rights of generations to come. A student activist once said, “We are the voice of the unheard,” expressing a sense of obligation and responsibility to their peers and society as a whole.

The failure of more conventional means of communication is frequently used to justify more violent or disruptive types of protest. For instance, by stating, “When voices are silenced, action speaks,” they emphasize how their actions should be seen as a final resort to bring about change. This narrative implies that activism could be approached pragmatically, with students adapting their protest tactics according to the level of institutional resistance they have encountered.

Students at BSMRSTU used a variety of rhetorical approaches to get their point across and rally support. The narratives of individual student experiences served as the foundation for the movement's moral and emotional appeal, highlighting the power of storytelling (Tilly and Wood, 2015). Watches and the wearing of particular colors were examples of symbolic gestures that people took part in to visibly express their cause and foster a sense of community and belonging.

Student discourse found a critical voice on social media, which allows for instantaneous information transmission, support mobilization, and audience involvement. In this case, they were trying to rally more public support for their cause by appealing to people's sense of fairness, justice, and the common good through the use of well-chosen words. Identity, justice, and resistance have been intricately woven within the discourse of BSMRSTU student movements. Both the particular dynamics of BSMRSTU and the impact of student action on Bangladeshi society norms and policies can be better understood with this knowledge.

3 Methodology of the study

A qualitative phenomenological strategy was employed to complete the research. In-depth interviews (IDI) were embraced to acquire a complete picture of the BSMRSTU student movement and its effects on social normality in Bangladesh. This study's mode of description suggested a qualitative method (Newman and Benz, 1998). By taking notes during interviews, participants can give more insight into the research topic. Analyzing the participant's views using qualitative research methods is possible, resulting in new knowledge (Creswell, 2013). Our in-depth analysis of the matter at hand was meant to provide the groundwork for standardizing the reporting of qualitative research. Our research is accessible as Supplementary material and was written following the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) recommendations (O'Brien et al., 2014) for qualitative research designs.

We made a concerted effort to ensure that the core notions of SRQR retained their flexibility. Primary and secondary sources were accessed to triangulate verification and interpretive methodologies, ensuring consistent results across the broadest possible contexts. Additionally, several literary works focusing on student movements and their effects on the general public were critically examined. We looked for reviews of university student movements across various sources, including Google Scholar, Scopus, Web of Science, daily newspapers, and more. We gathered all the relevant information and papers, assessed them carefully, studied them extensively, and concluded by making the required suggestions.

3.1 Study design and sample size

This study used a descriptive research strategy and acquired qualitative information. We chose a qualitative methodology because it allows us to understand better the subjective experiences, judgments, and views that underpin human behavior, thought, and action (Maher and Dertadian, 2018). A series of pilot surveys was developed to determine the questionnaire's dependability. The checklists used in the research were included in the Supplementary material to clarify the results.

According to Sandelowski (1995), while conducting qualitative research on relatively similar human subjects, a sample size of 10 is adequate. Charmaz (2004), for instance, argued that for modest tasks, a group size of 25 is sufficient. Moreover, Guest et al. (2014) amended Bertaux (1981) and stressed that 15 participants are appropriate for systematically selecting qualitative case studies in each qualitative research. However, we chose 26 in-depth interviews in which participants agreed to participate (Table 1). The final number of all samples has been determined during the conduction of data collection based on the rate of data saturation.

Table 1

| Participants (code) | Sex | Occupation | Socioeconomic status | Family structure/marital status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Male | Vegetable vendor | Middle | Nuclear |

| A2 | Male | Shopkeeper | Low | Extended |

| A3 | Female | Home maid | Low | Extended |

| A4 | Male | Businessman | High | Nuclear |

| A5 | Female | Housewife | Middle | Widow |

| A6 | Male | Drinking water supplier | Low | Extended |

| A7 | Male | Bus driver | Low | Nuclear |

| A8 | Female | Ice-cream vendor | Middle | Nuclear |

| A9 | Female | Home maid | Middle | Extended |

| A10 | Male | Fruit vendor | Low | Extended |

| A11 | Female | Street food vendor | Low | Widow |

| A12 | Male | Bus helper | Low | Extended |

| A13 | Male | Day laborer | Middle | Extended |

| B1 | Female | Housewife | High | Nuclear |

| B2 | Male | Shopkeeper | Low | Extended |

| B3 | Male | Private sector employee | High | Nuclear |

| B4 | Female | Home maid | Middle | Nuclear |

| B5 | Male | Street food vendor | Middle | Extended |

| B6 | Male | Rickshaw puller | Middle | Extended |

| B7 | Male | Day laborer | Low | Extended |

| B8 | Female | Housewife | Middle | Divorced |

| B9 | Male | Drinking water supplier | Middle | Divorced |

| B10 | Male | Shopkeeper | Low | Extended |

| B11 | Male | Rickshaw puller | Low | Extended |

| B12 | Male | Street beggar | Low | Single |

| B13 | Male | Government employee | High | Nuclear |

Characteristics of in-depth interview participants.

Source: Field survey, 2022 (developed by authors).

3.2 Study participants and sampling techniques

In the course of this study, data was collected through open-ended questionnaires from local individuals who had experienced the direct impact of student movements, embodying what can be described as victims of innocence within the movement culture and its mechanisms. The selection of participants was meticulously designed to ensure a diverse representation of perspectives and experiences related to the impact of student movements. Initially, this was accomplished by using purposive sampling, which is a way of selecting participants based on specified criteria and qualities that are relevant to the study subject. This system was included shopkeepers whose businesses were disrupted, bus owners who experienced financial losses due to movement activities, residents who faced difficulties during emergency medical situations, and other individuals who unintentionally became part of the ramifications of these movements.

After identifying the initial participants, the study increased the number of participants adopting snowball sampling. This method entails current study participants utilizing their networks to discover and recommend future individuals who have also been affected by student movements. The utilization of snowball sampling in this study was particularly advantageous in that it included a more comprehensive range of victims whose experiences may not have been attainable solely through purposive sampling. By adopting this strategy, the research was able to include a broader spectrum of individuals who were affected, thereby enhancing the study's understanding of the various impacts that student movements have on local communities.

The participants were selected and recruited on the basis of the following criteria:

-

i. Residents (both permanent and temporary) of Gopalganj district;

-

ii. Individuals who experienced devastating situations (resulting from student movements) that were reported to have more critical consequences than in usual times;

-

iii. Individuals whose livelihoods were severely disrupted by the BSMRSTU student movement outbreaks including a lack of access to safe affordable food, daily necessities, etc.;

-

iv. Consented to the interview.

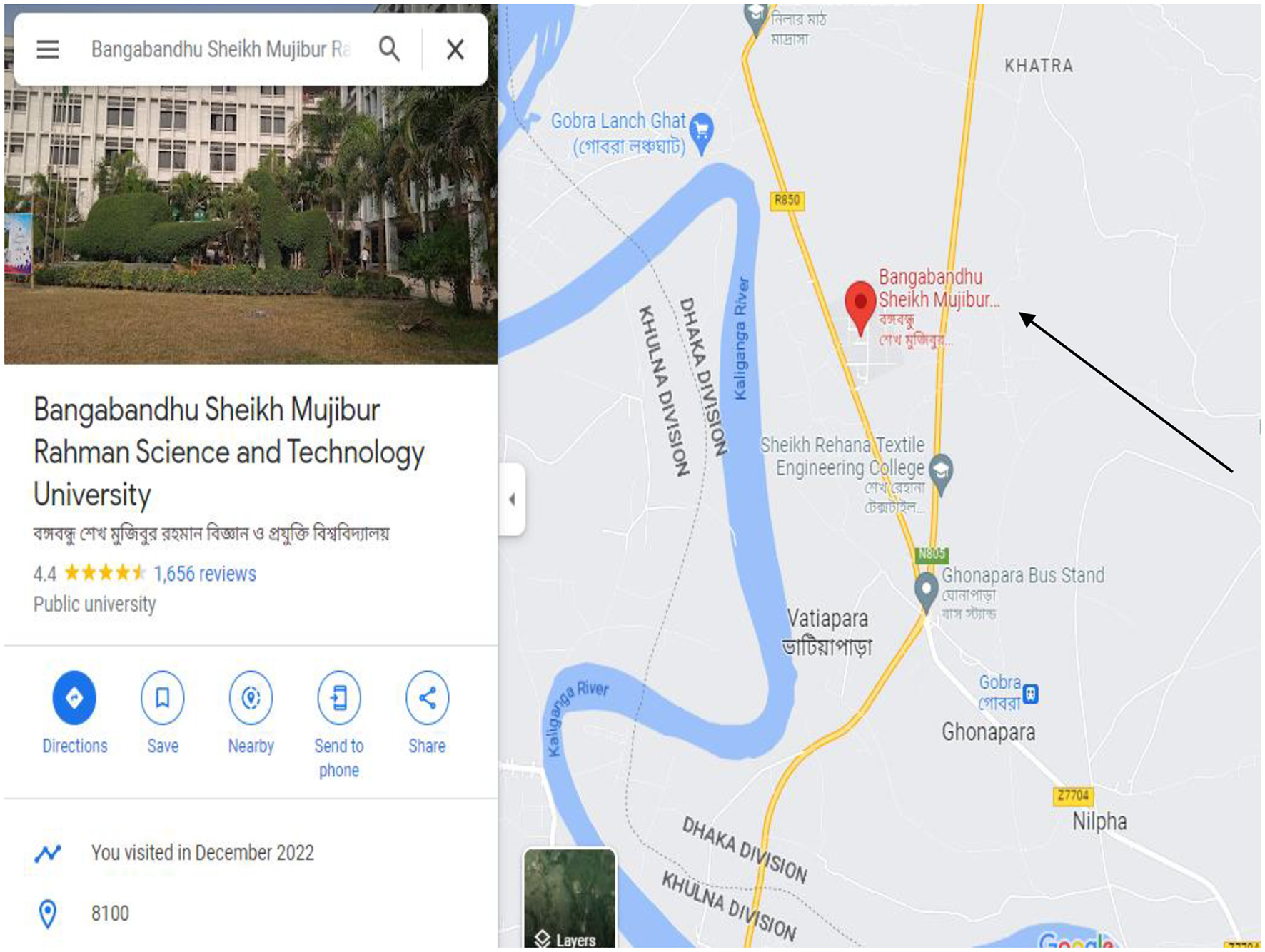

3.3 Area of the study

This research examines various student movements that have taken place at BSMRSTU, including the anti-VC movement, rape violence, road safety, local movements against students, and those demanding student rights. Our research focuses explicitly on the Gobra region near the BSMRSTU campus, located in the Gopalganj district of Bangladesh (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Area of the study (collected from BSMRSTU official website: https://www.bsmrstu.edu.bd/s/).

3.4 Quality assurance and data analyzing

We recorded the interviews, transcribed them, and translated them into English where appropriate. Using an inductive method similar to that suggested by Braun and Clarke (2022), we thematically evaluated the qualitative data collected from the interviews. However, to simplify the consent procedure, participants were informed that their participation was optional and would be kept confidential. The participants provided verbal approval after being assured that their privacy would be respected in any report compiled from the poll. Each interview lasted 15–30 min and was recorded on a portable equipment. Sometimes, the responses were jotted down instead of recording them because some participants were not unwilling to have them recorded. Psychological characteristics, employment histories, and workplace settings were all considered. Successive research and transcribing of the taped interviews confirmed their veracity. Data transcription was performed first, followed by a coding procedure. The study goal was met by identifying overarching themes and resonating subthemes through this coding method. The following steps were taken to implement this in a five-stage process: We gleaned the information by rereading the interviews and picking out new angles (Phase 1). Phase 2 involved systematically coding the entire data set with intriguing elements from which initial themes were derived. In Phase 3, we reviewed and approved the particular topic code. In Phase 4, two authors independently classified the qualitative data under identified topics. In Phase 5 we compared the findings across topics and worked to resolve any outstanding issues (Maher and Dertadian, 2018). We returned to the data multiple times to ensure that we were collecting the interviewee's information and that our interpretation of it was correct. After compiling a preliminary list of issues that emerged from the different transcripts, we conducted interviews to determine the study's overarching and underlying themes and motifs. Where we had doubts about the data's authenticity, we contacted the subjects again to see what they thought. The data was analyzed with NVivo V.12.0. Interviewees and topics that were similar were discussed, and only descriptive qualitative research methods were scrutinized.

3.5 Ethics

Human subjects were used in this investigation; however, the regulations of the author's institution stated that the study was exempt from the oversight of an institutional review board. However, we took precautions to guarantee the confidentiality and anonymity of our study's participants at all times. The volunteers could withdraw from the research at any time and for any reason. The participants' real identities were replaced with fictitious names, and their responses were coded using unique numbers to further protect their anonymity and safety. In addition, we safeguarded all the information by storing it in a password-protected Google Drive folder that was only available to the researchers.

4 Findings

We discussed the findings using the theme analysis described in the methodological sections. The research questions were answered with data collected from a sample of people representing a range of socioeconomic status, ages, genders, educational attainment levels, and geographic locations. We reviewed and translated the data after manually coding each transcript to answer study questions. The interpretation of the collected data was discussed issue-wise within a unifying framework and recurring topics.

4.1 Demographic profile of the participants

Age, sex, education, migration history, ethnicity, religion, marital status, number of children, occupation, and household income were the socio-demographic factors based on which various index variables were constructed. Table 1 indicates that the IDI participants' ages ranged between 18 and 64 years. There was a difference in the numbers of male (n = 18) and female (n = 8) participants. People from different socioeconomic backgrounds were included (Table 1).

4.2 Exploring movement culture at university premises: the BSMRSTU case

BSMRSTU was set up as a higher education institution in 2011 (BSMRSTU official website, 2022; https://www.bsmrstu.edu.bd/s/). With a novel organizational style in public higher education, it soon became apparent that there were several flaws. Problems such as insufficient classrooms, unreliable instructors, a lack of lab facilities, and student housing issues worsened as time passed. In 2018, the vice chancellor was reinstated to his position for a second time, and with that came renewed allegations of corruption and other misconduct. From the very beginning, BSMRSTU has been featured in the media for all the wrong reasons. The lack of respect for academic freedom was cited as one of the key complaints against the university. Vice-Chancellor Khondoker Nasiruddin has been criticized by both faculty and students for his dictatorial leadership and lack of democratic transparency. Allegations also included financial irregularities and indifference to completing the university's development tasks on time. When students question the violations, they receive a show cause notice and usually a temporary suspension order. There have been numerous claims of corruption in hiring faculty and support employees. Students have complained to the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) and even tried to garner the attention of the former chancellor of the university (Al-Mamun, 2023). Since the beginning of 2018, there have been several student movements at the BSMRSTU campus, including the following:

Anti-VC movement; movement for demanding rights for students (educational facilities, reducing semester fees, creating a new environment on campus); road safety movement (cases of faculty Moshiur and student Raisul); movement for demanding justice for rape victims; master-role movement for job permanence; Shibchar (local institution under BSMRSTU) student's movement for a return to the main campus; movement of the history department for their legal recognition, and other internal issues. The organization of student movements at the BSMRSTU campus often garners attention worldwide due to their frequency, which is deeply ingrained in the institution's culture.

The impact of such issues makes the students floppy, anxious, and tense due to the loss of academic time and career planning. Students have lamented their sufferings resulting from various movements and their purpose [adapted from Al-Mamun (2023)].

“Due to consecutive movements and their legitimation in campus culture, we are bored regarding random movements. Our career will be finished for the trapping culture of demanding rights…”

“When I entered this university, I had many plans, including academic and professional career. After a while, dramatic scenes continue by students and teachers, and we are suffering this so-called demanding rights and movement.”

“…classes, exams, and other academic activities were turned off when any movement was held on this campus. Because protestors locked the administrative and academic building's main gate to demand their rights” (Al-Mamun, 2023).

Students, faculty, and university administrative staff participated in revolts and engaged in different types of activism. BSMRSTU students are concerned that their academic year will be lost if the teachers' union continues its indefinite strike to demand their rights. Disappointment among students has increased due to the suspension of all administrative and academic activities. Exams for the Political Science, Pharmacy, Computer Science, Mathematics, English, and Law departments and the midterms were scheduled to commence during this period. The protest, however, prevented that from taking place. In addition, scheduled classes could not be held either. A 2nd-year political science student who asked that her identity be withheld made the following comment [adapted from Al-Mamun (2023)]:

“Our education has been disrupted due to the teachers' protest. Our mid-term exams were supposed to be done by this time, but now we are afraid of year loss.”

Another female student said,

“We have already faced a lot of education gap because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and now the teachers have boycotted the classes. All we do is stay in our hostel, eating and gossiping. We cannot hope for a good result this way. Teachers should also think about the students.”

4.3 Impacts of movements on social normality: unraveling the hidden truth

Bangladesh has been plagued by decades of corrupt politics, much of which can be traced back to the student bodies of the country's major political parties. No one disputes the significance of student participation in helping Bangladesh achieve independence. The Bengalis may be the only people whose culture was shaped solely by student politics. Unfortunately, student politics in modern Bangladesh have become a lethal trap for young people. The nation's time and money are being squandered on political culture to no good effect. Some student political groups are wicked; we have all witnessed it personally. Currently, Bangladesh's student body represents the antithesis of what a healthy student body should not look like. It deserves no backing from a moral, ethical, and judicial perspective. Students in Bangladesh face widespread hostility from locals. Reasonable restrictions on some political rights must be upheld in the name of public policy. Lacking in both political theory and pragmatism, the parties intentionally create and nurture toxic student politics for their vested interest, to the nation's detriment.

“Rhetoric about the pursuit of the common good becomes a plausible strategic consideration and a powerful recruiting and mobilizing tool” (Jackman, 2021).

In recent years, there has been a rise in student violence as a means of political participation, and students are less likely to inspire movements than they are to cause turmoil. Currently, Bangladeshi students are just as skeptical as those before them regarding politics. Bangladeshi students routinely call for both peaceful and violent demonstrations. The political positions of these student groups have been dictated by one of the two major political parties, demonstrating more of a commitment to party politics than genuine grass-roots movements. There are three major political parties in Bangladesh, each with a student wing that has access to substantial resources and, rumor has it, even swords and ancient weapons. There have been several high-profile assassinations and decades-long imprisonments of student political leaders who were never tried in court—something they were entitled to under the Constitution (Patwary, 2011). They are compelled to take political action, which includes questioning accepted wisdom because this is a matter of great political importance to them. Movements spark debate because they politicize traditionally non-partisan topics such as social justice.

4.3.1 Movements impact on public property

A student union is a group of people from different areas or countries who have come together to demand specific outcomes and are now leading a campaign to achieve those outcomes (Altbach, 1984). “Student union” means “an association of the majority of students at an institution to which this part applies whose principal aims include promoting the general interests of its members as students (Sydiq, 2022).” Typically, student unions oversee not just the cafeterias and other food service areas on campus but also small retail businesses, campus newspapers, study tour management, advocacy and administrative services, and recreational activities for the students who are members. Second, with a few exceptions, every nation has many national political parties (Andrews et al., 2016). Student unions are politicized groups that foster conditions conducive to future leadership development in such circumstances. When the road safety movement was started by BSMRSTU students, one of our field interview participants experienced violence firsthand. A tea stall vendor, Sumon (name changed), lamented his suffering when protestors broke his shop:

“I am a day laborer……. while students were agitating on Ghonapara Road (local name), I was in my tiny shop. Suddenly, I was shown they had broken down several car glasses, shop stores, and burning tires on the roadside. Protestors have made me poor in this regard; they broke my shop at that time” (A2).

A government employee also shared his sufferings when students agitated on highway roads:

“Being a government employee, I regularly went to my office at that time. Nevertheless, when the movement occurred then, I was shocked to see what the protestors had done, including road barricades, street lights, and other public property had been destroyed by the students” (B13).

A rickshaw puller, Lalu (name changed), shared a similar experience during the interview session:

“… apart from demanding rights movement, I experienced violence when the anti-VC protest was undertaken by the students. They broke my rickshaw (auto) after a while” (B6).

Public property was destroyed outside these haloed education institutions as the movement gathered momentum and non-students joined in the violence. Several news reports (The Daily Star, 2018; Bangla Tribune, 2021) asserted that during these protests, roads and rails were blocked, public property was destroyed, and markets were looted. In the movement, self-inflicted violence in the form of self-immolation rose and then waned. One street food vendor shared his experiences during the student movement in Ghonapara (a local, regional area in Gopalganj):

“A couple of times I experienced the bad student movement culture in the name of demanding their rights. Protestors were so-called students who incurred great loss for me by breaking my shop and damaging all the fruits” (A11).

Destruction of government property, on the other hand, has no apparent cost. In addition, the demonstrators hold the lives and livelihoods of regular Bangladeshis hostage to their ideology, which is already deeply embedded in the country's culture of movements. The Daily Kalerkantha (2021) reported that “unruly students and mobs” took to the streets in the name of a road safety students campaign, attacking motorists with improvised weapons and petrol bombs—several protesters also verbally and physically abused the bystanders. The incident caused 485,000 dollars in damages (Bangla Tribune, 2021).

4.3.2 “Days off:” financial impact on general public

There are checks and balances to limit violence because the state has a monopoly on it (just as it does on the creation of money), and the police are the agency that is authorized to use violence inside national boundaries. The final resort should only be the use of force by the police. However, for far too long, this “last resort” has been abused and devalued beyond all recognition to the point where it now penalizes police officers for upholding the law (Andrews et al., 2016). The influence of an ecology that sees violent protesters as victims and law enforcement as aggressors has allowed this narrative to take hold. It is challenging to conceal wrongdoings with modern instruments such as cameras on phones and in public places. No matter whether the culprits are criminals, students, or any other member of the public, including political leaders—they should be treated with zero tolerance if we, as a developing society and economic superpower, want to see a growing country free from violence. The several student movements at BSMRSTU impact human lives. Our field interview indicates that the impact of such a movement is so acute that it seems to be a burden for the general masses. A fruit vendor and a day laborer shared with us the financial impact of these movements:

“My income has been limited due to these movements. The shop remains closed for 2–3 days at a stretch. Open space shops were almost damaged by the protestors” (A10).

“Movement brings damage to us in many obstacles, including the financial crisis. Lack of customers damages the raw materials, fruits, and vegetables” (B7).

Ordinary people in this region constantly face such trouble. A drinking water supplier lamented that:

“For my business, I have to go to almost every region in Gopalganj district in my van. Due to student movement, I have remained off for days. I could not collect drinking water from the factory, so my business was also off then” (A6).

In addition, the food security situation became severe during times of movement when activists blocked roads and highways. This study revealed that the mobility of local individuals during a crisis contributes to their economic decline and hinders their ability to recover financially. Such an experience was lamented by a shopkeeper (poultry vendor) in our interview session:

“I have faced difficulties during these movements …………. I have five helpers in this shop. If a movement occurs, these five helpers have to starve throughout the day” (B10).

4.3.3 Physical harm and threatening experiences

Students are brilliant, successful, and intelligent individuals who are articulate and progressive. However, sometimes, they revolt in the name of demanding their rights. These movements would often not be successful, but public harassment, hartal, and blockage on roadsides are the methods to demand their rights. To demand student rights, they legitimize all these incidents or create violence on campus and roads and challenge social normality. Gobra regional people experienced such devastating situations through BSMRSTU student movements. Highlighting the theme of physical harm and threatening experiences during movement, a street food vendor stated:

“I am very scared for my life, tremble with fear, and worry about my health … anytime any violent situation happens. Bricks and other such threatening materials are thrown at us. These instances increase my tension regarding my life and security” (A11).

During student movements, anxiety increases among ordinary people, passersby, street vendors, customers, and many others. A street beggar shared:

“I was turned off at that time. As an old man, I felt so scared during the movement. I could not roam on the street due to the continuous outbreak of student agitations” (B12).

A private job employee explained:

“Sometimes movements become violent due to the maladjustment of some wicked people. They hamper the security of the general students as well as the local people” (B3).

During the interview session, the general public in this residential area also expressed their opinion regarding life security and physical harm:

“Most of the time, students gather at the Ghonapara edge (local region) and demand their rights on main highway roads. Due to the intervention of some local people, the situation becomes hazardous threatening life and security” (B9).

“During these protest movements, shops remain closed. Everyone is scared at that moment. We, the shopkeepers, keep ourselves safe behind high-walled buildings, fearing for life—a massacre-like situation was created” (A11).

4.3.4 Interruption of emergency care and physical mobility

We must remember that political rights are not absolute and are subject to many reasonable public policy restrictions. Many public universities insist on a non-political campus. Yet, the constitution and constitutional explanation would not bar the proposal for banning students' present anti-development and anti-enlightenment agitations. During student movements, it is evident that it hampered people, their different forms of livelihood, and social mobility.

A female participant shared the devastation she faced during one such student movement:

“Prolonged road blockages made the situation critical for the masses. Sometimes dying patients were not able to reach the hospitals at the right time due to these road blockages” (B8).

The movement had several impacts on the constantly happening and buzzing scenario among the public. On the issue of interruption of emergency and physical mobility, a rickshaw puller shared his opinion:

“The public faced several problems regarding movements. Road blockages hampered the long-ride passengers, and those who faced an acute problem with social mobility” (B11).

He further added,

“A critical patient died due to the severe road blockage at Ghonapara (local edge) highway.”

Encountering a student movement agitation could be scary for the general students and the general public. Socialization and physical mobility were interrupted whenever protestors organized these movements. A few participants share how their social mobility was impacted:

“Situation was more tense during the movement…traveling cost increased. Dhaka-Gopalaganj bus service remained off due to the road blockage by the protestors” (B6).

“I could not go to my office because of these movements and road blockages. Being a government employee at Khulna, I regularly traveled by bus. I still remember I was stuck for two days alone” (A7).

“The movement brought damage to people like us among the masses. I could not buy daily necessary products due to the restrictions of physical and social mobility on streets” (A11).

4.3.5 Impacts on social normality: a double burden for day laborers

The function of student organizations and the student movement today is frequently viewed in a very unfavorable light as part of a more significant decline in political ideals, demonstrated by a perceived rise in violence and corruption. Current data demonstrate student organizations' significant contribution to political violence in the nation. One of our participants, who earns her livelihood by selling street fast food, shared her experiences during the movement:

“Being a widow, I have to take care of my family myself…I have faced several obstacles while running my business. I am more tensed now on how I can manage my family” (A11).

During the last decade (2008–2018), political violence on campuses accounted for 13% of total violence in Bangladesh. Assume all political violence that occurred off-campus in which student organizations participated. By that measure, they become one of the most politically active groups, with a rate of over 27% in a calendar year (Jackman, 2021). Student violence is commonplace in Bangladesh's 20 most dangerous municipalities. Most public institutions and colleges are located in major cities where student violence is more widespread. This is the reality that the general public has to deal with. Although they were constantly losing money and starving, they saved some food. Such experiences were expressed during our field interview session:

“Before COVID-19, there was chaos between varsity students and the local people. When the clamor agitation was held, we faced the impact of continued student agitation, road blockage, price hikes, and many more. This led to huge loss among ordinary people who live hand to mouth” (A3).

“Price hikes are a new phenomenon in the BD context, Now… if movement occurs I may lose my balance in business and suffer huge losses, as I have previously experienced” (B10).

“The financial crisis triggered by the BSMRSTU student movements remains a double burden on my head. As a rickshaw puller (auto), I had turned off my income during movement days…… my income was less down as like feminine attack here” (B8).

In areas with high rates of violence, student groups are often actively involved in these events. As a result, understanding student politics can contribute to understanding Bangladesh's student movement. Due to recurrent student movements over time in this region, the ordinary people in Gopalganj are more like day laborers than general masses. They have experienced financial losses and restrictions on social, religious, and cultural due to movement restrictions. Their fear of security is quite pronounced:

“Over time, when movement occurred, I have not gone outside for walking or entertaining myself in the evening. Really, I have had to change my regular habit to sound off myself” (B12).

“I am fully dependent on students for business purposes… like me, other businessmen also depend on university students. If BSMRSTU remains closed for several days, then the inhabitants of Gobra region will remain unfed” (B5).

Student organizations remain one of the most critical breeding grounds for future political leaders, making it crucial that student groups play non-violent roles within their communities. Protesting in the streets is just one example of a social movement's use of collective action to dramatize and call attention to rights, welfare, and wellbeing among members of a particular group and spur change (Snow et al., 2008). Protests and social movements are the most common ways for individuals to express their discontent with a government or institution, advocate for fundamental human rights, and defend their right to vote. Both internationally and domestically, social movements such as the student movements have taken a new direction in recent years. The main roadways in Dhaka are usually closed to vehicles during student protests. Because of this, everyone is rushing around on foot to get to their destinations (The Daily Star, 2018).

5 Discussions

Recently, student protests in Bangladesh have been a significant topic of global conversation. The outcomes are supposed to represent the modern culture of movements for justice, equality, and reform. Politicians, the wealthy, and the capitalist class have successfully appropriated the movement's aesthetic. Political violence stems from the core cultures of intolerance, hostility, vengeance, and arrogance of social movements. Historically, politics has sanctified, inflamed, and legitimized violence as a protest technique to strive for other aims. Student movements in Bangladesh manifest the political violence that has normalized violence as a form of political expression and ingrained a culture of party violence among the country's youth (Jackman, 2021). The momentum of the movement has spread beyond the protected walls of the universities, and vandalism of public property has increased.

Our findings are supported by previous literature; various sources (The Daily Star, 2018; Bangla Tribune, 2021) attest to widespread violence and looting during this period, including blocking roads and disrupting trains, destroying public buildings, and looting stores and marketplaces. Self-inflicted violence, particularly self-immolation, reached a high point during this time and has subsequently declined. Neoliberal political battles are the primary cause of all acts of violence. This was supported by Rhoads (2016).

The activities of these political student wings illustrate how resistance to the neoliberal policy agenda is put into action in the name of students demanding rights. The action was partially effective since it led to the reevaluation, or at least the postponing of programs that were viewed as being financially motivated rather than intellectually motivated, and that impeded the ability of students to achieve their political aims. The activism of these groups also demonstrates the use of violence as a strategy of resistance and as a means of punishing and oppressing those who use violence. In this part of the world, average folks frequently encounter such tragedies. Also, the food security situation has been most severe during the period when protesters are blocking roads. This study's findings suggested that locals' inability to move forward due to a crisis contributed to their economic destruction. These findings are strongly supported by previous literature (e.g., Cabrera et al., 2017; Cole and Heinecke, 2020). Student organizations are highly involved in violent events in areas with a high crime rate. In light of this, it is vital to study student politics to learn more about the student movement in Bangladesh. Gopalganj's locals, more like day laborers than the masses, have been the target of student protests over the years. They have suffered monetarily due to relocation in addition to social, religious, and cultural disruptions.

In response to these pressures, political and social movements are working to alter the economic and social norms that sustain low incomes, as ideologically driven challenger movements often feel compelled to resort to “uncivil” techniques to achieve their goals and face an especially dire need for legitimacy. This was a political issue for them, and they must take political action by challenging commonly held assumptions and biases. The contentious nature of the topic of development and society is at the core of groups that seek to politicize it (McAdam and Su, 2002). The evidence has shown that a valid argument can be constructed by relying on well-established ideological resources from the cultural lexicon, as demonstrated by studies such as those conducted by Bellei et al. (2014), Hodgkinson and Melchiorre (2019), and (Richter et al., 2020). Talking of the common good could be a strategic factor in decision-making, and how it could be used as a rallying cry for support. In terms of rhetorical models, there is no universal method. A democracy's pillars include a free press, the rule of law, transparency in government decision-making, government accountability to the people and parliament, an independent judiciary, gender equality, and a healthy civil society. Democracy rests on the pillars of peaceful coexistence, tolerance, and respect for one another (Bebbington, 2007).

6 Limitations and future research directions

The student movement in Bangladesh's universities has become a significant concern for the country's future. Research and programming are needed to understand the entire breadth of the problem and develop workable solutions. The study's methodology could be better, and the data could be more balanced. Due to its heavy reliance on anecdotal evidence, the present investigation is not immune to such problems. Therefore, no inferences can be made, or statistical conclusions can be drawn. Despite the study's limitations, the researchers did their best to collect reliable data. However, extensive quantitative samples or a hybrid approach can be used in future research. An extensive study of this issue is required to find a solution. Literature on various aspects of student migration, especially in Bangladesh, reveals many unanswered questions. The following topics will be the focus of subsequent research: more research is needed into a variety of issues related to student protests, such as the media's role and responsibility in depicting the true nature of these movements, the political stigma attached to labeling them as such, the growing desire of the general public to share stories of their tragedies, the insecurity of the ruling power, and the legitimacy of political parties based on the support of fictitious masses. In order to close these knowledge gaps, countries and institutions must engage in relevant research.

7 Conclusion and policy recommendations

The history of student politics in Bangladesh is rich and illustrious. From the liberation war and the democratic movement of the 1990's (Moniruzzaman, 2009) to the language movement, several student leaders have played crucial roles in Bangladesh's national politics. There have been numerous student movements worldwide during the past few decades. Bangladesh has seen a rise in this practice in recent years. The movement (standalone) in Bangladesh is a case where such movements are central to the political history of the country, uniting key groups across society around issues of injustice and reform to confront regimes and bring about significant political transformation despite being undervalued in the study of authoritarianism and often argued to play a minor role in such transitions. Students in Bangladesh have long been at the forefront of political events and activities, providing a well-organized, widely representative, and ready pool of potential workers. It has been crucial to bring about political change through alliances between different organizations, sometimes with students at the core, but most notably including the organizational might of political parties. These movements have been incredibly influential in times of autocratic government when there is minimal political competition. As a result, the instance contradicts the generalization that social movements do not threaten the continued existence of authoritarian regimes.

This study hints that the opposition's employment of contentious political forms could decide the length of authoritarian rule, but only if these forms have become “institutionalized” within the relevant context and are now widely acknowledged as a mechanism by which a dictatorship can be overturned. No type of violence is promoted in this study. However, it brings up questions about what is driving the violence during student demonstrations. It raises concerns about the prevalence of a culture of student movements that values wickedness over critical thought and where social responsibility prevails. In Bangladesh, the growth and durability of democracy are hindered by a deep flaw in the country's political culture. Student protests, for all their apparent shortcomings, are a necessary component of the system. Evidence-based policy recommendations can play a crucial role in addressing the challenges highlighted by the student movements and in fostering a positive environment for dialogue, reform, and societal progress. Here are several policy recommendations outlined as follows:

-

Enhance communication channels between students and university authorities: Establish regular, structured forums for dialogue between students and university administration to discuss grievances, suggestions, and reforms. This proactive approach can prevent misunderstandings from escalating into larger conflicts (Rhoads, 2016).

-

Implement conflict resolution training and workshops: Incorporate conflict resolution training into the university curriculum for both students and staff. Workshops focusing on negotiation, mediation, and peace building techniques can equip all parties with the skills needed to address disputes constructively.

-

Strengthen student governance structures: Support the development of robust student governance bodies that can effectively represent student interests, participate in university decision-making processes, and serve as a liaison between the student body and the administration.

-

Promote civic education: Integrate civic education into the university curriculum to enhance students' understanding of their rights and responsibilities. This includes education on non-violent protest methods, civic engagement, and the importance of democratic participation.

-

Create policies for safe and peaceful protests: Develop clear policies that outline the right to peaceful protest while ensuring the safety and security of all university members. These policies should include guidelines for conducting protests, ensuring they are non-disruptive and non-violent.

-

Engage in community service initiatives: Encourage and facilitate student involvement in community service and development projects. Engagement can help channel student activism toward positive social change, building bridges between the university and the wider community.

-

Implement restorative justice practices: In cases of protest-related infractions, adopt restorative justice approaches that focus on reconciliation, restitution, and the rehabilitation of offenders through reconciliation with victims and the community at large.

-

Regularly review academic and administrative policies: Establish a mechanism for the regular review of academic and administrative policies to ensure they remain relevant and responsive to the needs of the student body. This should include avenues for student input and feedback.

-

Conducting research and monitoring: Support ongoing research and monitoring of student movements and their impact on society. This can inform policymakers, academic leaders, and the public, providing insights into the causes of student unrest and effective strategies for managing it.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MA-M: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The study was conducted as part of the fulfillment of an undergrad's thesis. First, the lead author (MA-M) would like to thank the Department of Sociology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University (BSMRSTU), Gopalganj-8100 for approving this work. Then, I am thankful to my honorable supervisor, AK (Azad) Sir, Assistant Professor of the Sociology Department BSMRSTU, whose constant and systematic supervision and inspiration enabled me to carry out this research. Further, it cannot be expressed properly by printed words. However, I would also like to express my gratitude to my loving parents (Md. Sirajul Islam and Mst. Taslima Begum), who inspired me at every stage of my work and made me confident to do this hard work very efficiently. Then special thanks and gratitude goes to my loving friend Pranto Kumer Das who give me his own gadget (laptop) for completing such study. Then, I would thank my research assistants (RA) Nurul Islam Uzzal and Md. Jahangir Alom, who are considering my loving juniors for their field-level support and encouragement to enrich this study. At the same time, the authors thank the editor and reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpos.2024.1307615/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

VC, Vice Chancellor; IDI, In-depth Interview; ACC, Anti-Corruption Commission; BSMRSTU, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University; JU, Jahangirnagar University; BU, Barishal University; SUST, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology.

References

1

Al-Mamun M. (2023). Movement Culture, Legitimate Violence and its Impact on Social Normality: A Qualitative Study on Recent Trends at BSMRSTU Student Movements in Bangladesh. An Unpublished Undergrad Thesis. Available online at: https://rb.gy/qcstb (accessed August 27, 2023).

2

Altbach P. G. (1984). Student politics in the Third World. High. Educ.13, 635–655. 10.1007/BF00137017

3

Andrews K. T. Beyerlein K. Tucker Farnum T. (2016). The legitimacy of protest: explaining White Southerners' attitudes toward the civil rights movement. Soc. Forc.94, 1021–1044. 10.1093/sf/sov097

4

Bangla Tribune (2021). Law and Crime. Available online at: https://www.banglatribune.com/law-and-crime/movement (accessed August 27, 2023).

5

Bebbington A. (2007). Social movements and the politicization of chronic poverty. Dev. Change38, 793–818. 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2007.00434.x

6

Bellei C. Cabalin C. Orellana V. (2014). The 2011 Chilean student movement against neoliberal educational policies. Stud. High. Educ.39, 426–440. 10.1080/03075079.2014.896179

7

Benford R. D. Snow D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Ann. Rev. Sociol.26, 611–639. 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

8

Bertaux D. (1981). Biography and society: the life history approach in the social sciences. Oral Hist. Rev.10, 154–156. 10.1093/ohr/10.1.154

9

Braun V. Clarke V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualit. Psychol.9, 3–26. 10.1037/qup0000196

10

Cabrera N. L. Matias C. E. Montoya R. (2017). Activism or slacktivism? The potential and pitfalls of social media in contemporary student activism. J. Div. High. Educ.10, 400–415. 10.1037/dhe0000061

11

Chan C. P. (2016). Post-umbrella movement: localism and radicalness of the Hong Kong student movement. Contemp. Chin. Polit. Econ. Strategic Relat.2, 885–908.

12

Charmaz K. (2004). Premises, principles, and practices in qualitative research: revisiting the foundation. Qual. Health Res.14, 976–993. 10.1177/1049732304266795

13

Cohen R. (1993). When the Old Left Was Young: Student Radicals and America's First Mass Student Movement, 1929-1941. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

14

Cole R. M. Heinecke W. F. (2020). Higher education after neoliberalism: student activism as a guiding light. Pol. Fut. Educ.18, 90–116. 10.1177/1478210318767459

15

Creswell J. W. (2013). Steps in Conducting a Scholarly Mixed Methods Study. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dberspeakers/48/ (accessed August 26, 2023).

16

Dagnino E. (2007). “Challenges to participation, citizenship and democracy: perverse confluence and displacement of meanings,” in NGOs Make A Difference? The Challenge of DevelopmentAlternatives, Ch. 3, eds. A. Bebbington, S. Hickey and D. M. Can (London: Zed), 3.

17

Gamson W. A. (2013). Injustice Frames. The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

18

Guest G. MacQueen K. Namey E. (2014). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publication.

19

Hodgkinson D. Melchiorre L. (2019). Introduction: student activism in an era of decolonization. Africa89, S1–S14. 10.1017/S0001972018000888

20

Jackman D. (2021). Students, movements, and the threat to authoritarianism in Bangladesh. Contemp. South Asia29, 181–197. 10.1080/09584935.2020.1855113

21

Kingdon J. W. Stano E. (1984). Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. Vol. 45 (Boston, MA: Little, Brown), 165–9.

22

Maher L. Dertadian G. (2018). Qualitative research. Addiction113, 167–172. 10.1111/add.13931

23

McAdam D. Su Y. (2002). The war at home: Antiwar protests and congressional voting, 1965 to 1973. Am. Sociol. Rev.5, 696–721. 10.1177/000312240206700505

24

McAdam D. Tarrow S. Tilly C. (1997). Toward an integrated perspective on social movements and revolution. Comparat. Polit.1997, 142–73.

25

Moniruzzaman M. (2009). Party politics and political violence in Bangladesh: issues, manifestation and consequences. South Asian Surv.16, 81–99. 10.1177/097152310801600106

26

Newman I. Benz C. R. (1998). Qualitative-Quantitative Research Methodology: Exploring the Interactive Continuum. Carbondale, IL: SIU Press.

27

O'Brien B. C. Harris I. B. Beckman T. J. Reed D. A. Cook D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med.89, 1245–1251. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

28

Patwary M. E. U. (2011). Recent trends of student politics of Bangladesh. Soc. Change4, 67–78.

29

Rhoads R. A. (2016). Student activism, diversity, and the struggle for a just society. J. Div. High. Educ.9, 189–202. 10.1037/dhe0000039

30

Richter J. Faragó F. Swadener B. B. Roca-Servat D. Eversman K. A. (2020). Tempered radicalism and intersectionality: scholar-activism in the neoliberal university. J. Soc. Iss.76, 1014–1035. 10.1111/josi.12401

31

Sandelowski M. (1995). Qualitative analysis: what it is and how to begin. Res. Nurs. Health18, 371–375. 10.1002/nur.4770180411

32

Snow D. A. Soule S. A. Kriesi H. (2008). The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

33

Sydiq T. (2022). Youth protests or protest generations? Conceptualizing differences between iran's contentious ruptures in the context of the December 2017 to November 2019 protests. Middle East Crit.31, 201–219. 10.1080/19436149.2022.2087951

34

The Daily Jugantor (2018). Bangladesh Road-Safety Protests by Students. Available online at: https://www.jugantor.com/online (accessed August 27, 2023).

35

The Daily Kalerkantha (2021). Students Protests Continue for 7th Day. Available online at: https://www.kalerkantho.com/print-edition/news/2021 (accessed August 27, 2023).

36

The Daily Observer (2015). JU Proctor Resigns amid Student Movement. Available online at: https://www.observerbd.com/ (accessed August 27, 2023).

37

The Daily Star (2018). The Rise and Silencing of a Mass Student Movement. Available online at: https://www.thedailystar.net/news/star-weekend/cover-story/the-rise-and-silencing-mass-student-movement-1618390 (accessed August 27, 2023).

38

Tilly C. Wood L. J. (2015). Social Movements (London: Routledge), 1768–2012. Available online at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315632070/social-movements-1768-2012-charles-tilly-lesley-wood (accessed August 27, 2023).

39

Useem B. Zald M. N. (1982). From pressure group to social movement: organizational dilemmas of the effort to promote nuclear power. Soc. Probl.30, 144–156. 10.2307/800514

40

Weldon S. L. (2012). When Protest Makes Policy: How Social Movements Represent Disadvantaged Groups (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press), 243.

Summary

Keywords

BSMRSTU, Gopalganj, manifestation, student movements, social normality

Citation

Kalam A and Al-Mamun M (2024) Analyzing the rhetoric of contemporary BSMRSTU student movements: manifestations and social implications in Gopalganj, Bangladesh. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1307615. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1307615

Received

04 October 2023

Accepted

16 April 2024

Published

06 June 2024

Volume

6 - 2024

Edited by

Ismail Suardi Wekke, Institut Agama Islam Negeri Sorong, Indonesia

Reviewed by

Ufuoma Patience Ejoke, University of the Free State, South Africa

Yamina El Kirat El Allame, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Morocco

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Kalam and Al-Mamun.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Md. Al-Mamun 17soc044@bsmrstu.edu.bd; mamunsiraji6576@gmail.com

†ORCID: Abul Kalam orcid.org/0009-0006-8372-1840

Md. Al-Mamun orcid.org/0000-0002-4133-757X

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.