Abstract

This article explores the role of Estonian community houses in supporting sustainable cultural development and the vitality of communities in a turbulent era of global change. It poses the following questions: (1) How do the representatives of community houses perceive their roles and challenges? (2) How does organizational agency and cultural policy (at national and sub-national level) contribute to cultural sustainability in the context of such disruptions? To answer the first question, in 2022 an online questionnaire survey targeting representatives of Estonian community houses was conducted. The article is based on quantitative and qualitative analysis of 126 responses. The second question provides historical, political, and cultural context to address the first. Estonian community houses, numbering 376 in operation today, are a unique network to study. In the nineteenth century, these cultural hubs became the basis for the system of non-formal life-long education, arts and culture, and later regulated and developed within the subnational politics of culture and education in the Estonian nation-state (1918–40), in the Soviet Union (1940–91), and in today's Estonia (1991–2023) as part of the European Union. The COVID-19 pandemic added a new set of disruptions. In this light, the continuity of the functioning of community houses, alongside their ability to adapt, becomes particularly important for both local communities and sustainable cultural development.

1 Introduction

This article contributes to the growing literature on cultural sustainability with a case study of Estonian cultural centers, called community houses (rahvamaja), which form an important network through which to study national and local cultural policies of different political systems. Since the nineteenth century, built by local communities, these cultural hubs enabled rural populations to participate in new types of cultural and lifelong learning practices (Bildung), and formed a public cultural sphere. Later, their activities were developed by the cultural politics and policy in the first Estonian republic (1918–40) and regulated in the Soviet Union (1940–91) as well as in today's Estonian Republic (1991–2023). Estonia's first network of cultural institutions, with 376 buildings still in use today (Kulbok-Lattik, 2015, 2016, 2018; Kulbok-Lattik et al., 2021, 2023).

Cultural centers are not Estonian-specific phenomena, as they also act as key local institutions in other Baltic and Nordic countries, as well as all over Europe, providing a myriad artistic and cultural activities for citizens as audiences and active practitioners (Bogen, 2018; Pfeifere, 2022). Although, there is no single definition of the characterization and legal form (private or state-owned) of cultural centers in Europe, they share similarities in roles and impact on society. Pfeifere (2022) offers as features characteristic of cultural centers the presence of art and culture, education and leisure, and recreation and sociality. Further, an important common feature of cultural centers is that both they and their activities facilitate cultural democracy (Duelund, 2009) and citizen participation. Participation, which is a malleable concept with many meanings and values attached (Carpentier, 2011; Eriksson et al., 2019), is one of the central concepts relating to cultural centers, cultural policies and sustainability.

The concept of cultural participation covers both people's passive and active behavior and includes cultural consumption as well as activities undertaken within the community (Kangas, 2017). For instance, in Finland, cultural centers offer a multitude of cultural activities and cultural participation has been a key concept of Finnish national cultural policies, increasing equality and accessibility in society (Kangas, 2017). Participation in cultural centers was studied at a European level by the “RECcORD” research project (Eriksson et al., 2019, 2020) and in a Danish context in the “DELTAG” project (2019-22). Further examples of increasing interest in “participation” research include “Removing Barriers: Participative and Collaborative Cultural Activities Kuulto” action research in Finland (Kangas, 2017), in Danish and Finnish cultural centers (Järvinen, 2021), and also on the roles of, and challenges faced by, Estonian community houses (Kulbok-Lattik et al., 2021).

This current turbulent era of global economic, ecological, technological, cultural, and political change, including migration and unimaginable war in Europe, further emphasizes an urgent need to research the different participation practices and societal functions of cultural centers as well as their organization and historical transformations. Using a recent case study of Estonian network of community houses, this article seeks to understand their roles in supporting sustainable development in changing contexts and cultural disruptions. Our approach, here, is based on sociological study and analysis of cultural policy. Contextualizing community houses as Estonia's first cultural institutions and interpreting recent data gathered in 2022 by Kulbok-Lattik and Roosalu, the article first asks how the representatives of community houses perceive their roles and challenges faced, and second, how organizational agency and cultural policy (at national and subnational level) contribute to cultural sustainability in the context of disruptions.

Also, we use the historical perspective of cultural policy research. Estonia has a distinctive experience of the cultural policy practices of different systems, which we have conceptualized as of multiple modernities (Eisenstadt, 2000, p. 1–3; Wittrock, 2000, p. 66–67). Accounting for the experiences of different systems—Western modernity (1920–40), Soviet cultural policy (1940–1991), transition to EU membership and Europeanisation (1991–2004, 2004–2023)—gives a valuable opportunity to observe the influence of national cultural policy on cultural practices at different levels. The use of a historical approach makes it possible to trace the original roles of community centers and to observe different discourses, discontinuity, and sustainability at national and subnational levels of cultural policy, and their interrelations with supranational policy discourses (Kulbok-Lattik, 2015, 2018).

Indeed, as the key concepts of the global discourse of Bildung and sustainability are not static, there is a need to rethink what cultural sustainability means within the context of the diversity and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) adopted by the United Nations in 2015, and how this is reflected at the local level. In order to address these issues, this paper will, first, provide the theoretical context and the central concepts of the Bildung and sustainable development; second, we briefly map the roles and impact of Estonian community houses in different eras; and third, we present some key results of our empirical research.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Theoretical context

There is a remarkable variety of cultural policies and cultural institutions, which depend considerably on their specific historical socio-economic background: politics, the historically formed social order, system of values, and dominant ideologies.

Laclau and Mouffet (2014) suggest that culture, economy, and society can and should be analyzed as discourses, as no meaningful phenomenon can exist outside discourse. In this study, we use the term “discourse” in the Foucauldian sense within the framework of social theories (Ruiz, 2009), as being linked to power and state, insofar as the control of discourses is understood as a hold on reality itself (e.g., if a state controls the official rhetoric and media, they control the “rituals of truth”). Foucault (1991, p. 194) views power as a mechanism, and a network which interacts not only from top to bottom but also vice versa. Although the pyramidal structure of power has its clearly defined “head”, the institutional apparatus as a whole produces power.

Therefore, the concepts of culture and cultural policy are discursive, socially constructed and not neutral, as cultural policy never exists in isolation from the prevailing debates (ideologies) and political discourse, as noted by several scholars (Kangas, 2004; Kangas and Ahponen, 2004; Kangas and Vestheim, 2010; Kulbok-Lattik, 2015; Sevänen and Häyrynen, 2018). Thus, cultural policy has a direct impact on state-supported cultural practices and institutions, which then constitute and reproduce hegemonic discourse and ideologies. As a result, the goals and instruments of state cultural policy, as well as the functions of cultural institutions, are determined by hegemonic discourse. In this article, we observe cultural policy as modern state practice, with roots in the emergence of Herderian romantic nationalism and post-Enlightenment nation-states when culture—interpreted as arts—became linked to the administrative apparatus of state. In respect of different cultural practices, fields and forms of arts, decisions regarding exclusion or inclusion made by the state and institutions are determined by a specific historical outline of systemic values, the orientation of which is specific to each country (Kulbok-Lattik, 2015).

2.1.1 Modern state, cultural policy

Defining the concept of culture, we use the concept of societal cultures, which is closely connected to the process of modernization. Kymlicka (2009, p. 255) refers to Gellner (1994), who argues that the modern nation-state with its institutions, standardized education, media, economy etc., is one of the agents able to create a common socio-economic, political and public space which is meaningful for the whole population and can guarantee the sustainability of societal culture.

Here, the historical role of the cultural policies of the nation-state appears with a primary goal to form and develop an institutionalized context for the education system, the arts, and cultural practices. Within these connections also lies a further historical aim of the politics of culture: education, refinement, and civilization (i.e., nation-building and Bildung), which are imposed by inclusion- and exclusion mechanisms of state support and financial aid for different cultural practices. However, the concept of cultural policy was developed by twentieth-century post-war European welfare states in the 1960s and 1970s, when new concepts were introduced in international discussion (cultural development, democratization of culture, cultural democracy, socio-cultural animation, cultural rights), alongside novel practices through which attempts were made to strengthen the status of culture (the arts and cultural heritage) and cultural policy in nation-states (Kangas, 2017).

2.1.2 Pre-state politics of cultural and civil activism—Bildung and the nation building

In the Estonian case, the roots of cultural policy lay in the civil activism (seltsiliikumine) of Estonians in the Tsarist Empire from the second half of the nineteenth century onwards. This civil activism and societal movement is inherently linked to national awakening or emancipation and the public sphere. It is evidenced by the appearance of newspapers, community houses etc., where it was reflected by, and mediated and constructed in the cultural and social practices of the people, as scholars of Estonian nation-building (e.g., Karu, 1985; Raun, 2001, 2009; Jansen, 2007) have shown. Important preconditions for national cultural emancipation were widespread literacy among Estonians, and the agrarian reforms of the nineteenth century which had a direct impact on the majority of the Estonian population as the native population became landowners and the capitalist economy developed. Originating in national awakening, the development of Estonia could well be characterized by general Western modernization starting with the reorganizing of the static agrarian society into a modern European nation-state.

Conceptualizing modernization, we rely on Martinelli (2005, p. 19), who defines it as a set of transformations that had begun in Western Europe by the late eighteenth century referring to the socioeconomic (e.g., industrialization, urbanization), political (e.g., democratization and mass participation), and intellectual (e.g., secularization, mass literacy). Specific feature of the modern cultural code is expressed through the German tradition of Bildung, which emerged in the eighteenth century, corresponding to the ideal of education in the work of Wilhelm von Humboldt. Bildung refers to the tradition of self-cultivation, wherein philosophy and education are linked to a process of both personal and cultural maturation. The concept and practices of Bildung become a lifelong process of human development, rather than mere training in gaining a certain external knowledge or skills.

The idea of Bildung had a remarkable effect on popular education work in the cultural centers or community houses that began in nineteenth-century Europe, including in Finland, and the Nordic and Baltic countries. The modernist ethos of an established favorable ground for socio-economic, cultural and national emancipation went hand in hand with political emancipation (Bildung and nation-building) among the small oppressed European nations (the Finns, Estonians, Latvians, Slovaks, and Slovenians, for example), as empirically analyzed by the prominent theorist of nations (Hroch, 1985, 1996).

According to Hroch (1996) the modernization of those nations in Eastern Europe who lacked previous political statehood happened in a similar way: cultural emancipation developed into a wider cultural public, which allowed for the formation of their political public and the emergence of nation states when various empires collapsed in the twentieth century. For these nations, the end of the First World War and the final disintegration of empires was an opportunity to realize aspirations for national self-determination and to establish modern nation-states (Kulbok-Lattik, 2015).

Thus, one of the important historical roles of cultural centers (community houses) has been their specific ability to create a national and local public sphere. The shared identity of a society was formed through shared narratives, which were shaped by participants in the common practices of culture and education (Guibernau, 2007; Wodak et al., 2009). Several researchers (Ojanen, 2016; Andersen and Björkman, 2017) claim that the idea of Bildung and popular education work was a major factor in the creation of the Nordic social model. In their book, The Nordic Secret, Andersen and Björkman (2017), a Dane and a Swede, explain how folk-Bildung, that is, liberal education, is the “secret” behind the Nordic countries' economic and social success story. However, the concepts of modernity, as well as Bildung are not static. Social scientists (Eisenstadt, 2000, p. 1–3; Wittrock, 2000, p. 66–67) are of the opinion that in view of the divergent developments and different political systems of civilisations and regions, it is more appropriate to speak of ‘multiple modernities'. We suggest that Estonia, like the other Baltic states, shares different modernities or experiences of modern state practices, and its discursive interventions of state arts and educational policies. For example, this includes experiences of Western (nation-state) and Soviet modernities with the corresponding forms of the different practices of Bildung.

Finnish scholar, Lahti (2019) discusses the changing (discursive) nature of the concept of Bildung, pointing to Finland's national philosopher Snellman (1806–81) who thought that “the idea that Bildung is something timeless is utterly unrealistic. Instead, Bildung develops and changes over time, and it has to be redefined in each era.”

Lahti (2019) concludes that Bildung should be recognized as a dynamic, or active and living concept, and defines the idea of changing Bildung as follows: “While in the early twentieth century Bildung had a nationalistic objective to build the nation state and lay the foundation of our welfare state, it could now play a major role in a novel societal transformation—the change required for solving the complex problems of our time.”

2.1.3 Sustainability—new Bildung

The concept of sustainable development, defined as an harmonious development of social, economic and environmental areas, has long conceptual roots, and international organizations have played a significant role in contesting the meaning of the term and its content, as it has been shown by Kangas et al. (2018).

The concept developed in the context of the transformation process of the green movement, and first came to prominence in 1980, when the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources presented the World Conservation Strategy with “the overall aim of achieving sustainable development through the conservation of living resources”. The evolution of the concept developed into the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015. At its heart are the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDG United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, 2015), adopted by the United Nations in that year which represent an urgent call for action by all countries in global partnership. They recognize that ending poverty and other deprivations must accompany strategies that improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth—all while tackling climate change and working to preserve the oceans and forests.

Nevertheless, none of these goals referred to integrating culture into sustainable development planning and decision-making. Duxbury et al. (2017, p. 214–230) argue that culture's absence from sustainable development debates have been rooted within the longue durée interplay among theoretical and policy debates on culture in sustainable development and on cultural policy since the mid-twentieth century. They propose four roles cultural policy can play toward sustainable development: “first, to safeguard and sustain cultural practices and rights; second, to ‘green' the cultural sector's operations and impacts; third, to raise awareness and catalyze actions about sustainability and climate change; and fourth, to foster ‘ecological citizenship'.” In this regard, the challenge for cultural policy is to embody very different co-existing and overlapping roles in relation to sustainable development.

Cultural sustainability tends to be defined in two ways. On the one hand, it refers to the sustainability of cultural and artistic practices and patterns, including, for example, identity formation and expression, cultural heritage conservation, and a sense of cultural continuity. On the other, it also refers to the role of cultural traits and actions in informing and composing part of the pathways toward more sustainable societies.

We believe culture lies at the core of practices and beliefs that can support or inspire the necessary societal transition to more sustainable living. These narratives, values, and actions contribute to the emergence of a more culturally sensitive understanding of sustainable development and to clarifying the roles of art, culture, and cultural policy in this endeavor.

2.1.4 18th sustainable development goal: viability of the Estonian cultural space

In addition to the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), which are common for all countries, Estonia has developed its own priorities for sustainable development since 2005. The National Strategy on Sustainable Development “Sustainable Estonia 21” (hereafter, SE21) was produced by a wide-scale consortium of experts and approved by the Estonian Parliament on 14 September 2005. The main goals set out in SE21 were the vitality of Estonian cultural space; increase in people's welfare; socially coherent society; and ecological balance. In the context of SE21, the Estonian cultural space is defined as an arrangement of social life based on Estonian people, traditions, and the Estonian language.

The sustainability of the Estonian nation and culture constitutes the cornerstone of sustainable development of Estonia also today. The viability of the Estonian cultural space has been agreed to be the 18th Sustainable Development Goal in Estonia until the year 2030. The development goal postulating this has a fundamental meaning: the persistence of Estonian-hood is the highest priority among the development goals. The Estonian cultural space has been also developed in the Estonian community houses as part of the natural and living environment.

2.2 Historical roles of community houses and context of national and subnational cultural policy

Estonian community houses (rahvamaja) have their roots in the nineteenth-century tradition of grass-roots-level social activism. Estonian Societies were established according to the example of local German Societies in both town and country. During the Tsarist empire, from the 1870s onwards, community houses were built by ordinary people, aiming to offer a space for new types of cultural activities such as choirs, plays, orchestras, libraries and public festivities for local communities. These cultural hubs became pre-state cultural institutions with civilizing aims (Bildung) for Estonian communities, where the development of a wider public sphere evolved in the circumstances of being under the rule of Baltic German landlords and the restrictive tsarist state.

Estonian national aspirations (which were initially connected with cultural goals) became more political over time, demanding equal rights compared to the ruling Baltic-German nobility with regard to participation in the administration of local affairs. Thus, the construction of community houses has a social and political dimension, as an act of collective will to create room/space for cultural activities for Estonians, where a democratic public in the Arendtian sense (Arendt, 1985) could appear.

However, with the construction of community houses, Estonians, as a colonized ethnic group with the lowest status in society, created not only a cultural and political public, but also a new spatial model for their cultural development that could be seen as an informal (or “bottom-up”) educational system and cultural policy arising from civil society.

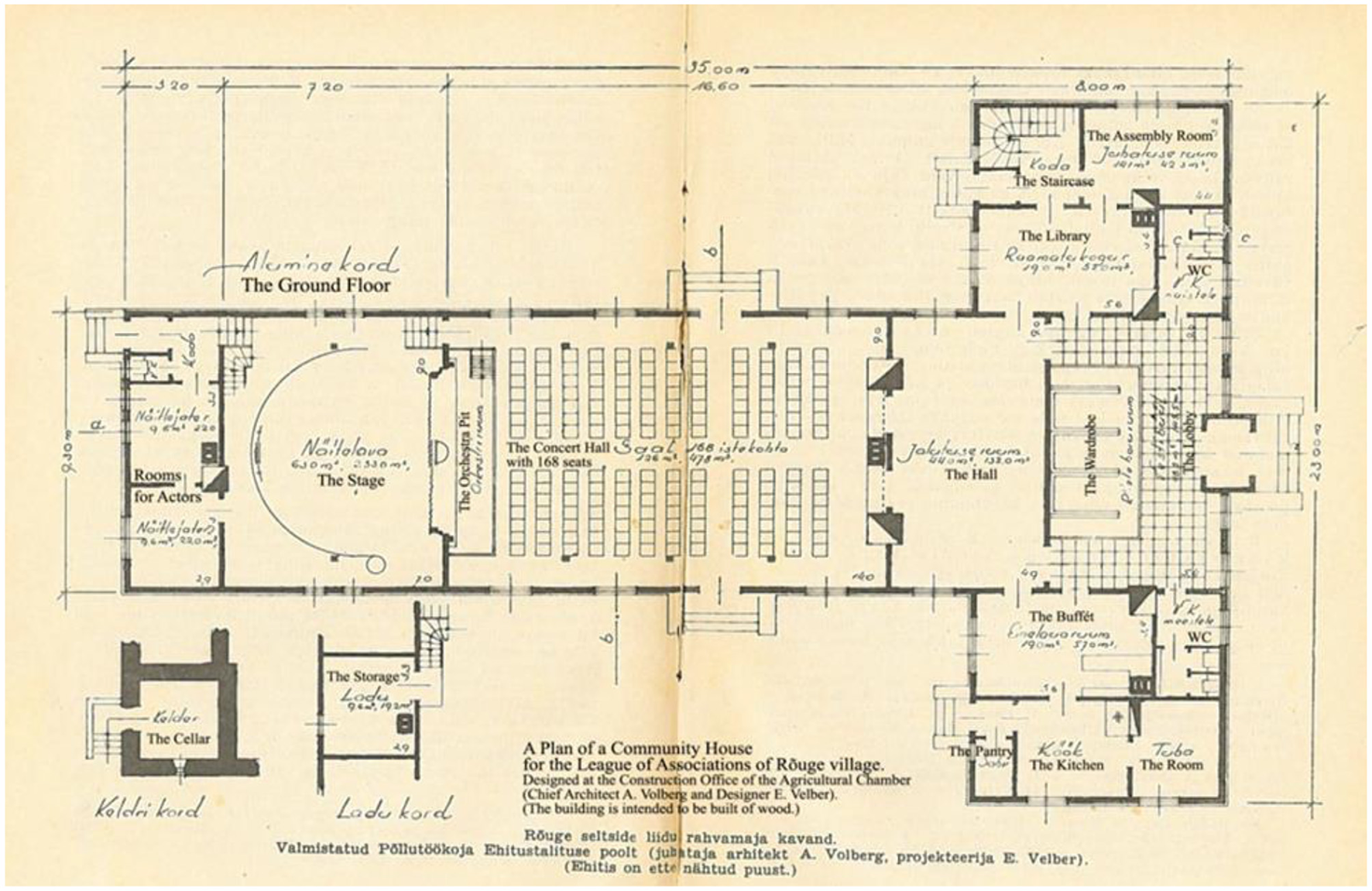

This had the specific type of room program modeled according to that of an opera house or theater, with stage, hall, buffet, library etc. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Typical plan of community houses with the stage, hall etc. (Kurvits, 1935).

From 1880, historical research and statistics reveal constantly an increasing cultural participation by Estonians, until it is possible to speak of cultural mass-participation by the first half of twentieth century. Hence, we can see a new spatial model of culture which created opportunities for both cultural development and social interaction, while collective action ensured the spread of national ideas to the masses, on the basis of which the emerging economic and political elite could make political demands. It is in these links that the relationship between cultural public sphere and the political public sphere becomes clear, which can be summarized as follows: the cultural public sphere legitimates and justifies the demand for political self-determination (Kulbok-Lattik, 2018).

This new spatial model for culture became the basis for artistic hobbies and lifelong learning-system of informal education, which later was regulated and developed within the politics of culture and education in the various eras until today's. This system of artistic and cultural practices, together with informal education, forms an essential basis of the national system of innovation (Johnson, 1992; Kulbok-Lattik and Kaevats, 2018).

During the first Estonian Republic (1918–40), the network of community houses was set up by the state. By 1940, there were more than 400 community houses (Kulbok-Lattik, 2015, p. 155) all over Estonia, which operated as local institutions for the development of Estonian cultural policy, being the expression of the socio-economic and cultural vitality of Estonian rural regions.

After the invasion and occupation of the Baltic states by the Soviet Union in 1940–1941 and after 1944, extensive restructuring, with the nationalization of private property, began. Thus community houses and their property were expropriated. The Sovietization of community houses meant also the importation of the Soviet cultural canon (its norms and values) and cultural policy model. Bottom-up initiatives by societies were prohibited and all organizations operated and guided by the state. The Soviet cultural policy model was fully implemented in Estonia. The final aim of the Soviet cultural policy was to transform people's behavior and create the Soviet person—a mass-man in an atomized society, as Arendt (1985) has described. New buildings for cultural centers (in the monumental Stalinist architectural style) were constructed by the Soviet authorities in Estonia and by 1950 there were 651 clubs and cultural centers (as community houses were called during the Soviet era) (Kulbok-Lattik, 2015, p. 156).

However, widely accessible, publicly funded homogeneous mass and folk culture accounted for a substantial part of Soviet cultural welfare. At the same time as traditional cultural practices as the official canon of Soviet cultural policy were mediated, national resistance was also promoted in community houses. These cultural practices and national resistance finally lead to the mass mobilization of the population in the form of the Estonian Singing Revolution and re-establishment of the independent Estonian republic in 1991 (Kulbok-Lattik, 2015).

Since then, community houses have gradually lost their national importance as a tool of state cultural policy, since the main aim of the Estonian state was the promotion of professional culture and the responsibility for the development of amateur culture was left to local municipalities (Aadamsoo et al., 2012; Kultuuripoliitika, 2014; Kulbok-Lattik et al., 2023). Although state support for cultural institutions continued, community houses have been supported financially, administratively and politically mostly by local governments. The budget of a municipality depends on county population figures as well as residents‘ income levels. Due to this, a considerable decline in the budgets of community houses has occurred.

A significant change took place in 2004 when Estonia joined the European Union and transnational cultural policy has also started to affect decisions made at national and municipal levels. The cultural policy of the EU highlights issues such as participation, equality, sustainability, heritage, etc. that all belong to the core values of Estonian community houses (Kulbok-Lattik et al., 2023, p. 165–166). The vitality of cultural space is thus measured according to the scope, functionality, temporal continuity and plasticity of Estonian culture. In this rhetorical context, community houses should play a central role in ensuring cultural continuity and accessibility, especially in rural areas.

However, due to urbanization and migration (in 2004, the European labor market opened partially to Estonian citizens), the population of Estonia—and especially in the countryside—has been in constant decline. The situation sets up two challenges related to financial and human resources: since both the number (~500 in the 1940s, 651 in the 1950s and 376 in 2022) and budgets of community houses are diminishing, the sustainability of the community houses is increasingly put at risk. It is noteworthy that the 376 community houses currently employ only 543 staff members. It means that the agency, i.e., self-determination and functioning of community houses, is weakening, threatening the sustainability of cultural networks and communities.

As many municipalities currently lack the human resources for the development of local cultural policy, different networking institutions have been established during the period of independence but joining these networks has been voluntary, and there is no coherent cultural policy tackling the functioning of community houses.

In 2023, 1.3 million inhabitants lived in Estonia, out of which 462,000 were situated in the capital city of Tallinn. As noted above, the population has been in steady decrease during the previous decades because of emigration. A low birth rate contributes to the phenomenon, although a change has been observed due to immigration from Ukraine since 2022. Estonia is a sparsely populated country with 31.4 inhabitants per km2 and 46% of the whole population lives on the northern coast around the capital (Statistics Estonia).

As seen above, community houses have experienced different cultural political practices in the context of different modernities—Western and Soviet—as well as several transformations and disruptions. First, as a new spatial model for culture, community houses became the basis for refinement, artistic hobbies, and the lifelong learning-system of non-formal education, which was later regulated and developed with the politics of culture and education.

All these transformations signify that each political system creates a specific set of management and institutional tools for cultural production and education in society, in order to legitimize the state as an apparatus and as well as its political authority. As state interference shapes the discursive narratives, instrumental concepts and practices related to culture, education, and creativity, it has a broad impact on the identities and life of individuals, as well as on society as a system of innovation (Potts and Hartley, 2014). Hartley and Potts have developed the theory of culture as an evolutionary adaptation system which is not only an efficient mechanism to carry and replicate existing knowledge (as well as to facilitate in-group coordination and cooperation), but also a mechanism to make new knowledge. From this perspective, they explore how creativity, novelty and innovation evolve in society though the formation and interaction of cultural groups. We can see how innovation springs from the activities of civil society agents and how state interference in culture and education becomes a central coordinator in shaping cultural practices (Kulbok-Lattik and Kaevats, 2018).

3 Empirical study of Estonian community houses in 2022

To capture experiences and narrative strategies of representatives of community houses, a sociological study was carried out early 2022. Our empirical study inquires into organizational agency in the context of disruptions, exploring how the representatives of community houses present their role, their challenges and tasks ahead. This mixed-method study had three steps: pilot interviews with key stakeholder representatives to discover key topics of relevance; an online questionnaire survey targeting community houses (126 responses were received, while 71 of these were fully completed); and the most recent events were taken into account when interpreting the results. In this way, theoretical and historical background, current social context and studies from other countries provide the basis for interpreting the results.

The online survey was carried out using the LimeSurvey institutional platform at Tallinn University. It covered 24 different topics, including altogether more than 350 sub-questions, many of which were formulated as open-form questions, offering respondents a chance to express themselves in the way that best fits the situation of their community. This means that the survey was rather extensive and not everyone who started filling it had the patience or time to answer all the questions, therefore, when presenting the results, we have also highlighted how many answers each of the questions had received.

In this article, to discuss the role of Estonian community houses as the key actors on local level cultural policy, three themes form our focus. First, we explore what the roles that representatives of the community houses see they serve in their communities are, and who they see as their main target group. Second, we map their reflections on COVID 19-related interruptions and innovations. Third, we provide an overview of future visions the representatives of community houses create. Such a research strategy, focusing on qualitative analysis of open answers from a stakeholder online survey, reliably reveals patterns in local level understanding of the role of community houses in this new reality, and enables us to provide a typology of local reactions to recent challenges, and helps to highlight their visions of future.

4 Key results

4.1 Community houses: functions and target groups

The survey posed an open question on this, and 71 answers were received. The analysis revealed that only twelve representatives did not explicitly mention their target group alongside naming their core functions, leaving the supposed beneficiaries more implicit. Others mentioned the community at large [on 36 occasions], people [6], (local) population [4] and residents (of village/region) [5] or used some age indication to determine their target group (e.g., children, pupils, youth, parents, adults, the elderly, the retired, whole family). On a few occasions, the (local) hobby groups or the whole region was mentioned as target groups benefitting. So, most representatives of community houses defined their expected target group when thinking of their most important roles for their community.

The axial coding analysis of the open answers revealed eight larger groups of roles:

-

Social communication, social capital: enabling community-based participation and communication [49 responses]: center for social communication; most important meeting place; true community center; place for socializing; glue for the local community.

-

Non-formal education and lifelong learning: providing opportunities for engaging in hobby activities [28]: place for leisure; place for self-expression; place for engaging with recreational activities; place for hobby groups to gather and rehearse; place for participation in folk dance and acting; place to widen one's horizon; work with children and youth; hobby education for locals from 7 to 90 years of age.

-

Mediating professional arts and meaning-making through culture: organizing events, mediating culture and providing access to professional culture [27]: we bring professional theater and concerts close to home; we educate people in culture and health; we are key organizer of cultural events within the community; we provide possibilities for enjoying culture; we meet the demand for culture in the community; we promote events of folk culture; we organize celebrations according to the folk calendar.

-

Providing services to the local community [11]: nowadays it is also a place where people come to ask for help; people often contact the manager of the community house who then gives advice and provides help; people approach us with their troubles (e.g. bank transactions, printing Covid-19 certificates); our house provides social services, also the library is very popular; our community house is the house for the community and we provide several social services, e.g., laundry, hairdresser and a beautician.

-

Renting rooms [8]: we rent out rooms for private events; it is a good place for private parties; families can rent the rooms for social events (e.g. birthdays or funerals).

-

Political representation: mediating community and local authorities [6]: the community house represents the community; the community house is the place for the local authority to engage with local people; the community house is used for elections; it is an apolitical space; ever since the local government reform, the community house has a crucial role in mediating information with the local government.

-

Institutional networking: bringing third parties together for cooperation and joint activities [4]: we work together with local NGOs; we cooperate with other actors and contribute to joint events; we communicate with different communities and support organizing events with our know-how; the community house has the key role in the region together with school, library, youth center and local society.

-

Physical culture, sports, exercises: organizing sports events and activities [3]: we organize regional competitions in chess and drafts; we educate people on health; we provide options for sporting activities.

On several occasions, the social emphasis of the community house was underlined through different activities:

We provide our community the opportunities to learn, relax and enjoy culture, but most of all to escape the daily routine. However, as we also host a youth center and there is a primary school is nearby; it is a safe place for the students to spend their time after school, as parents know where their children are.

So, for adults the community house offers chances to relax and to learn, just like children. In fact, many other responses listed several key roles, pointing to the fact that the combination of more than one activity focus is essential in serving the community in the best way. An example of complex and intertwined roles puts emphasis even further on local identity and social cohesion:

It is a local cultural establishment in the community, which serves in maintaining traditions, arranging cultural life, keeping traditions alive. It also increases the sense of home, protecting and building local identity and the like. Such a local cultural institution adds value to the whole region, supporting and promoting social cohesion in the area with its existence and activities. It provides opportunities for spending leisure time. It offers people the chance to engage in hobby groups on local premises. It mediates professional culture.

Apart from these concrete functions, on 28 occasions other elements were emphasized that mean community houses carry a unique role. These highlighted the feeling that their community house is useful, very important, has a prominent place, plays a rather big role—or very big role. The use of those superlatives and emphasis on the relevance of the role shows those working for the community house have a clear understanding of that role.

In some cases, this role was underlined by visioning a dystopian alternative: destroying the community house means downward development in the village and degrading the quality of the living environment. Here, the mission of keeping the community house operational is clearly motivated by avoiding larger losses. Others emphasized the relevance of keeping up their hard work clear role for the community house exists, but a lot of work is still required in the community so that people would find their way to the community house -, indicating that not all the communities were fully ready to make use of their community house.

This non-participation is related to the lack of health or other resources (time and money), but also to apathy—people have learned to cope without the community and community houses. From this background, the relevance of the COVID-19 pandemic for community houses deserves a more specific examination.

4.2 COVID disruption: change and innovation?

The open question about COVID-19 impact was worded as follows: how did practices change during COVID pandemic since March 2020? To what extent are these changes related to the direct impact of COVID?

We received 63 full responses to this question. Most of them showed that the representatives of community houses did not have a good systematic overview of the changes, their nature and the factors behind them, and indeed they may lack resources (e.g., working time, accounting systems etc.) to estimate the extent. Among those who did express their experiences as negative, some used words that indicate something extreme:

COVID influenced all of the activities of the community house.

Our activities have been practically put on pause/limited to a minimum .

COVID has largely decreased [the number of events and audience].

It has very much changed individual behavior.

This emotional connection to the significance of COVID impact, even though COVID had been around for a while by the time of the study (the survey was carried out in January 2022, but impact of COVID pandemics in Estonia can be traced back to March 2020), indicates its devastating effect on the everyday life and work of the community houses, pointing to inevitable interruptions. We can reveal four types of negative impact:

People [35 answers]: audience numbers decreased; people are more passive; it is more difficult than before to get people out of their homes; many are fearful; the elderly do not dare to come out. Related to this is the direct impact of vaccine pass requirement[11]: many people do not trust vaccines; in some communities those that have decided not to get vaccinated used to be among the most active community members, but access to events is restricted without a vaccine pass (or testing)

Events [20]: number of events decreased; organizing of events practically non-existent; cooperative events, e.g., with local schools, have been canceled.

Hobby groups [8]: hobby group activities are seriously affected or entirely stopped; as getting together is very difficult, this has created tensions among group members.

Economic—rental and other income [4]: decrease in rental of rooms (e.g., before 2020, the community house was fully booked at weekends) and other alternative income basis, combined with increasing prices.

COVID-19 has thus clearly interrupted some of the community houses' most important contributions. Whereas there may still be services to provide (that do not require also serving as a meeting place) or political representation functions to fulfill, the key aspects—providing space and occasions to meet, events to take part in and learning activities to engage in—were seriously affected.

On a positive note, innovative solutions were reported in 11 answers, e.g., making use of outdoor possibilities, going more actively onto social media or launching entirely new practices:

our activities are now carried out mostly outdoor, or only when events are outdoor and the weather is nice we have the same participation numbers than before [COVID],

Facebook and other social media have been reported to be helping keeping contacts alive between the members of hobby groups.

Clearly, then, these interruptions have also brought positive aspects. It generally seems, indeed, that it is only the attitudes of the representatives of community houses that helps them cope with what otherwise might be a hopeless situation. This is reflected either in their experience that some problems have been solved, or their hope that (maybe with enormous work) they could be solved in the future, as indicated in these answers:

Everything has changed. It is hard and we are working very much to keep all our activities alive and sustainable .

I guess the direct impact is only on the way still. Our [amateur] theater group has not been able to meet […] We hope for the best , so it will be sustained, and new wonderful plays will be staged.

COVID has had an impact on all the activities of the community house, so one has to search very hard for new ways to organize and carry out events, how to reach your target groups, and also how to carry out the hobby activities. On the other hand, it seems that had we already lost some of our audiences even before COVID, and COVID just accelerated the trend.

The last example in particular helps to see COVID-19 experiences in a more strategic perspective: if experience with COVID-related, somewhat forced innovation helps the community house find new ways to reach the community, this might actually help to support the strengthening of the role of the community houses. This leads us to the next section on the question of future outlook.

4.3 Future outlook: problems and expectations

To put the mapping of future outlook in context, it should be mentioned here that according to our survey that just 18 of the participants confirmed their community house as having a strategic action plan, whereas 41 said they do not have their own strategic plan and when planning their activities, they follow the more general strategic plans for the sphere of culture that their local government has prepared. Another 18 admitted that their community house is somewhat improvising when setting its daily priorities ad hoc. Three respondents stated they are not aware of how their strategic decision making really works. This summary shows that only a minority of respondents have the resources with which to engage in systematic strategic planning.

It might also mean, therefore, that the discussion of problems, expectations and future outlooks that follows offers some mapping of individual stakeholder views rather than providing insights to the community houses as institutions. Conversely, in many cases the survey was answered by those who run the daily activities in the community house they represented, thus allowing us to conclude that the views expressed here indeed offer a very important insight into the worries and hopes of community houses in Estonia.

During the survey, we invited respondents to rank the challenges and problems that community houses in Estonia face in 2022, providing a list of issues and offering the possibility to also add others. Altogether, 71 respondents engaged in this exercise.

The outcomes of this exercise suggest that the key challenge is a lack of clarity in terms of the role of community houses. Representatives perceive that the roles community houses are expected to fulfill requires further clarity at the level of state cultural policy, pointing to the lack of formal, but perhaps also informal, recognition. This is followed by concern over wages and pay levels, as well as the need to improve the technical equipment—in most general terms, their funding. All the other issues are much less relevant and even when the respondents chose to elaborate on other categories, added-in answers were never the highest priority.

We also asked what the most urgent problems that the specific community house needs to solve in their nearest future might be. Here, the largest challenge seems to be (re)connecting to the people in the community or strengthening this connection; this was mentioned in 30 responses. In some cases, this was accompanied by naming a specific target group, be it young families, children, working-age adults, schools, or multicultural communities. But mostly this just referred to the need to get people back to the community houses after being scared away by the pandemic, and thus keep hobby groups running, so that others could join them, and organize events that would be of interest to local communities.

We also asked in a more concrete way what needed to be improved so that the community houses would find it easier to fulfill their roles in their community and in Estonian society in general. The 49 answers highlight the expectations that range from honest I really cannot say and Let's just hope that nothing very crazy happens, to this realist take:

This is just a dream or a miracle that suddenly all the needs we have in cultural institutions will be met and people will just be bewitched into doing everything enthusiastically... The reality is different - there is no magic cure, and the state cannot keep supporting everyone.

In between these fatalistic laissez-faire approaches, several types of expected changes are mentioned, and our mapping exercise distinguished the following key expectations:

-

Lifting COVID restrictions is sufficient: this reflects the understanding that as soon as we get back to previous life-styles, things will turn back alright, as if the interruptions had never existed,

-

Clarification and recognition of the roles of community houses: wider understanding and agreement on the functions and roles that community houses carry, potentially not just at the community or local level but through national discussions and debates,

-

State level regulations: possibly a specific law, or otherwise some directions, so that common understanding would be secured in longer term,

-

Funding, especially for wages: funding needs to be secured at a higher and more stable level, so that it would enable the paying of decent salaries, in order to hire the most suitable people, and secure the technical needs related to buildings and equipment,

-

General regional and economic policy interventions: further external interventions are expected to secure people within the communities with better paying jobs so they could afford to invest their time and money into cultural participation, non-formal learning and social communication, so as to sustain life in the countryside and at the peripheries.

As can be seen, while some of the answers seem to be satisfied with “just” lifting COVID restrictions and others require policy interventions “to secure life in the countryside”, in the wider sense, most of the expectations are specifically related to recognizing and institutionalizing the roles and functions of community houses and securing sufficient funding for them.

In addition to this, we provided an open question for final comments to this lengthy survey, and we received 33 responses, with 21 commenting the survey itself—some technical, some expressing optimism and gratitude regarding the fact that a survey of such a nature was being carried out. There were simple words of thanks alongside hopes that the study results would be widely shared and would thus bring about some change. While there were doubts expressed that a COVID-era survey would be representative of the everyday life of community houses in Estonia, others pointed out that such an in-depth study helped them to think through different aspects related to their community house and thus answering the survey questionnaire was perceived as interesting and useful. These answers indicate that there may be insufficient chances in “normal” times to think strategically about the roles that community houses play in their communities and offering a forum to share one's thoughts with others is a welcome arena in which to do this. Perhaps opportunities like these should be created more systematically.

Other thoughts shared in the final comments touched the need for formal recognition of the work the community houses and cultural workers do in society. Seven answers mused on this theme, their thoughts ranging from suggestions to organize a Year of Community Houses that would provide the ongoing state level recognition to this topic of key relevance culturally, socially and from the point of view of regional policy, to the need to establish a specific legal regulation on community houses (introduced in Lithuania in 2004 and in Latvia in 2022), to the need to recognize that every community house needs a dedicated and decently paid employee. Recognition was also needed beyond wages, since

wages in themselves cannot really compensate for the effort cultural workers really invest in this work. The long nights, organizing, editing, managing work, sometimes the forced not-too-popular decisions, taking time at the expense of their own families.

These words or worry were echoed in another, as one respondent said in their final comment, taking an even longer view:

We are on a longer journey here and we need to pull ourselves together, so that our culture will be able to stay there forever.

Indeed, the representatives of the community houses saw themselves as being on a longer mission, clearly above daily politics, supplying their services ahead of the demands that their communities do not know to make, and the state should have the wisdom to make.

5 Conclusions and discussion

Research into cultural centers has been rare, but there is growing interest in their organization, historical changes, participation and social function (Kangas, 2017; Bogen, 2018; Kulbok-Lattik, 2018; Eriksson et al., 2019; Järvinen, 2021; Pfeifere, 2022; Kulbok-Lattik et al., 2023). It has been found that the centers and their activities facilitate cultural democracy (Duelund, 2009), education, cohesion, and citizen participation—a key concept in cultural centers, but increasingly also in other cultural institutions and cultural policies (Kangas, 2017). Traditional cultural and governance practices which support democratic cultural participation and diversity are considered to be the key to sustainable development.

Our sociological research here, carried out in early 2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic, concentrated on the challenges and disruptions in Estonian community houses and on their strategies of resilience, which is a novel approach in the field of cultural research. The use of an historical approach in the study of cultural policy makes it possible to trace the original roles of community houses and to observe different discourses, discontinuity, and sustainability in national and subnational levels of cultural policy, and their interrelations with supranational policy discourses.

Our article explored the roles and challenges of Estonian community houses as perceived by their representatives. The research outcomes have been interpreted in the historical, theoretical and political frameworks of cultural policy with focus on ideas like participation, organizational agency and sustainability.

5.1 The roles and challenges of community houses

We explored the roles that representatives of the community houses see they serve in their communities, and who they envisage as their main target group. It revealed that the basic historical roles of the community houses and practices of culture work have not changed: the representatives mentioned both social, cultural and educational functions as the main aims of their work.

First, representatives of the community houses still highlight their most important role as being bringing the community together—providing possibilities for shared togetherness. They still operate as a space where institutional meaning-making affirms local and national identities and narratives, and where important events are celebrated. It appears that these cultural and educational institutions are shaping the narratives of official (state) memory work as well as individual (local community) strategies of belonging.

Second, community houses are still places for life-long non-formal education and self-expression (music and art schools, as well as dance and theater studios, libraries, etc.) thus forming a basis for educational and regional development and acting as a proto-innovation system (Kulbok-Lattik and Kaevats, 2018).

This certainly is related to audience development, future professionals, participation and the sustainability of Estonian culture. Yet, they also provide welfare and social cohesion for aging people.

Third, the community houses continue to be the cultural hubs where traditional artforms, both amateur and professional, are mediated and practiced. By organizing major festivals and regional events, they promote regional images and bring economic benefits. Community houses more knowingly act as promoters of regional development.

Fourthly, there are also some new roles taken up by the community houses during the post-socialist period in small communities, for example, renting rooms to providers of welfare services (such as hairdressers, laundries, etc.) and state services (such as local government, post offices, or police posts).

In addition, we mapped the reflections of COVID-related interruptions, and resulting innovations by the community houses. Our research reflected an understanding among the representatives of community houses that, as soon as they return to previous arrangements, the majority of acute problems will be solved, which expresses strong institutional agency. However, the question of sustainability is whether new generations will be able and willing to keep up and build upon these traditions if it requires such heavy amount of effort and is only meagrely remunerated. Thus, it seems that cultural policy needs to raise this issue and design a more sustainable model for the local level.

Further, COVID-19 may have emphasized some of the problems, they were already there—for example, the decreasing population numbers threatening the sustainability of remote areas. In places where COVID was inspiring new possibilities, e.g., using social media and digital connectivity, the community was already likely driving such innovations beforehand.

Finally, we provided an overview of future visions the representatives of community houses create. Several types of expected changes were revealed: recognition; state level regulations; and funding, especially for wages. It also became clear that representatives of Estonian community houses feel a lack of research and scientific reflection, cultural political attention, recognition, and support by the state. There are expectations that national-level cultural policies should help meet grassroots policy challenges and secure the sustainability of community houses.

5.2 Organizational agency, historical paths of cultural policy and sustainability

First, the study highlighted historical links between policy-making and discursive political changes at local level. It revealed that the basic historical roles of community houses and practices of culture work have not changed: the community houses have been following their historical habitus. It has been the nature (as well as one of the original roles) of community houses to contribute to the cultural, as well as the political formation of the local public sphere. Indeed, community houses have been used for political representation by the authorities during all the different political systems in Estonia. At the same time, they have always carried non-hegemonic agenda and acted as places for parties. Taken together, all dimensions of European cultural centers—art/culture, education/leisure, recreation and social (Pfeifere, 2022)—are also represented in the work of Estonian community houses.

Estonia has had a distinctive experience of the cultural policy practices of different political systems, which we have conceptualized as of multiple modernities. Observing for the different experiences of Western modernity (1920–40), Soviet modernity (1940–1991), post-modern transition to EU/Europeanisation (1991–2004, 2004–2023) provides an ample opportunity with which to study the influence of national cultural policy on cultural practices at different levels (Kulbok-Lattik, 2015).

Thus, based on the example of Estonian community houses, we can observe the historical path of the wider Estonian public sphere, where cultural dynamics appears in the forms of culture as the mechanism for creating identity and groups (Hartley and Potts, 2014), and cultural and educational emancipation as the basis for political mobilization and national system of innovation (Kulbok-Lattik and Kaevats, 2018). Further, we can see how the network of cultural organizations of the first Republic of Estonia, with its roots in the nineteenth-century societal civil activism, was subjected to governmental guardianship by the Soviet state.

Path dependency is their strength and weakness. Infrastructure, i.e., community houses built in different eras and under different ideological and political regimes, provide a thick network covering the whole country. But in the changed socio-economic context of an aging and declining population, depopulated areas, migration and urbanization, in some regions community houses lack resources, including people whom to serve. It means that the agency, i.e., self-determination and functioning of community houses, is weakening, threatening the sustainability of cultural networks and communities. Recent political, economic and social disruptions (for example, the COVID-19 pandemic) have strongly shaken the habitus of the community houses but also proven their resilience and ability for innovation.

However, it has also become very clear that Estonian community houses currently feel a lack of scientific reflection, cultural political attention, recognition, and support by the state. There are expectations that discourse—ideas, values existing in the rhetorics of state documents on cultural politics—could help meet challenges at the municipal level and a belief that centralized cultural policy could secure sustainability and diversity of culture in the regions. The centralization concerns, first, close (prescribed?) collaboration between municipal cultural institutions and, on the other hand, between state (for example, the Ministry of Culture) and municipal institutions. The community houses need financial and (cultural-) political aid but also symbolic capital (i.e., recognition and appreciation).

In conclusion, for integrating and mediating new discourses related to sustainability and European Green Deal policies as new Bildung, Estonian community houses need clearly formulated functions and future aims set by both sub- and supra-level cultural policies. A sustainable financing system that does not depend only on the number and income of local inhabitants and on the budgetary possibilities of local governments should also be created based on the functions and aims of those cultural policies. This should be considered as a tool for diminishing regional and social inequalities and assuring vitality of national and local (sub)cultures and identities.

We assume that in the context of the contemporary turbulent era of global economic, ecological, technological, cultural, and political crises (including migration and war), while the mediated public sphere has lost its reliability, physical public spaces like community houses gain an ever more significant importance in providing possibilities for participation and self-expression. However, the future of this valuable cultural network, as well as that of other regional institutions in Estonia, depends not only on cultural policy solutions but also on balanced regional and economic development.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written and oral informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants. No personal data was requested and the respondents' anonymity was guaranteed.

Author contributions

EK-L: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft. AS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research project of the article have funded by the Estonian Ministry of Culture Avaleht | Kultuuriministeerium and by the Society of Estonian Community Houses. Rahvamaja | Esileht (edicy.co). Estonian Ministry of Culture Tallinn University research grant TF2721 “Meaningful life from five to nine: interdisciplinary research network to strengthen inquiries into hobby education and serious leisure” (2022–2023).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aadamsoo M. Arujärv E. Ibrus I. Jõesaar A. Karulin O. Kulbok-Lattik E. et al . (2012). Eesti kultuuripoliitika põhimõisted ja suundumused. Tallinn: Eesti Kultuuri Koda, Kultuuripoliitika Uuringute Töörühm. Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/2288816/Eesti_kultuuripoliitika_p%C3%B5him%C3%B5isted_ja_suundumused (accessed May 21, 2022).

2

Andersen L. Björkman T. (2017). The Nordic Secret. Fri Tanke.

3

Arendt H. (1985). The Human Condition. New York: Doubleday.

4

Bogen P. (2018). Business Model Profiling of Cultural Centres and Performing Arts Organizations. Lund: Trans Europe Halles. Available online at: https://www.Creative-Lenses-Business-Models-Profiling.pdf(creativelenses.eu)

5

Carpentier N. (2011). The concept of participation. If they have access and interact, do they really participate?Commun. Manage. Q.21, 13–36.

6

Duelund P. (2009). “Our kindered nations: on public sphere and the paradigms of nationalism in nordic cultural policy,” in What about Cultural Policy? Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Culture and Politics, eds. PyykkönenM.SimainenN.SokkaS.. Jyväskylä: Minerva, p 117–130.

7

Duxbury N. Kangas A. De Beukelaer C. (2017). Cultural policies for sustainable development: four strategic paths. Int. J. Cult. Policy23, 214–230. 10.1080/10286632.2017.1280789

8

Eisenstadt S. (2000). Multiple modernities. Daedalus, Winter1, 1–29.

9

Eriksson B. Houlberg Rung M. Scott Sørensen A. (2019). Art, Culture and Participation [Kunst, kultur og deltagelse]. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

10

Eriksson B. Stage C. Valtysson B. (2020), Cultures of Participation. Arts, Digital Media Cultural Institutions. London, New York: Routledge.

11

Foucault M. (1991). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of Prison. London: Penguin Books.

12

Gellner E. (1994 [1983]). “Rahvused ja rahvuslus. [Nations and Nationalism.],” in Ajakiri Akadeemia, ed. J. Isotamm (Tartu: KE kirjastus).

13

Guibernau M. (2007). The Identity of Nations. Cambridge: Polity.

14

Hartley J. Potts J. (2014). Cultural Science: A Natural History of Stories, Demes, Knowledge and Innovation. London: Bloomsbury.

15

Hroch M. (1985). Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe. A Comparative Analysis of the Social Composition of Patriotic Groups among the Smaller European Nations.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

16

Hroch M. (1996). “From national movement to the fully-formed nation: the nation-buidling process in Europe,” in Becoming National, eds. EleyG.SunyR. G. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 60–77.

17

Jansen E. (2007). Eestlane muutuvas ajas. Seisusühiskonnast kodanikuühiskonnani. [Estonians in the Changing World: From Estate Society to Civil Society].Tartu: Eesti Ajaloo Arhiiv.

18

Järvinen T. (2021). Strategic Cultural Center Management (Routledge Research in the Creative and Cultural Industries).London: Routledge.

19

Johnson B. (1992). “Institutional learning,” in National Systems of Innovation. Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning, ed. LundvallB. A. (London: Anthem Press), 21–45.

20

Kangas A. (2004). “New clothes for cultural policy,” in Construction of Cultural Policy (Helsinki: Minerva Kustannus), 21–41.

21

Kangas A. (2017). Removing Barriers: Participative and Collaborative Cultural Activities in KUULTO Action Research. Helsinki: Cupore – Kulttuuripolitiikan tutkimuskeskus, 44. Available online at: http://www.cupore.fi/images/tiedostot/2017/cupore_kuultoresearch_final.pdf (accessed August 17, 2023).

22

Kangas A. Ahponen P. (2004). Construction of Cultural Policy. Helsinki: Minerva Kustannus, 94.

23

Kangas A. Duxbury N. De Beukelaer C. (2018). Cultural Policies for Sustainable Development. London, New York: Routledge.

24

Kangas A. Vestheim G. (2010). Institutionalism, Cultural Institutions and Cultural Policy in the Nordic Countries. London: Nordisk kulturpolitisk tidskrift, 13. Available online at: http://www.idunn.no

25

Karu E. (1985). On the development of the association movement and its socio-economic background in the Estonian countryside. Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis–Studia Baltica Stockholmiensia2, 271–282.

26

Kulbok-Lattik E. (2015). The Historical Formation and Development of Estonian Cultural Policy: Tracing the Development of Estonian Community Houses (Rahvamaja).Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University Printing House. Available online at: https://jyx.jyu.fi/dspace/handle/123456789/47243 (accessed January 8, 2023).

27

Kulbok-Lattik E. (2016). Seltsi- ja rahvamajad - eesti uus ruumiline kultuurimudel lääneliku moderniseerumise ja kujuneva kultuuripoliitika kontekstis. Acta Hist. Tallinnensia22, 44–66.

28

Kulbok-Lattik E. (2018). “Community Houses. Modern Cultural and Political Public Space in Estonia,” in Spectra Transformation. Arts Education Research and Cultural Dynamics, eds. B. Jörissen, L. Unterberg, L. Klepacki, J. Engel, V. Flasche, T. Klepacki (New York, Münster: Waxmann Verlag GmbH), 139–151.

29

Kulbok-Lattik E. Kaevats M. (2018). Vaimult suureks. Ühiskondliku innovatsiooni alused [Great in Spirit. The Basis of Social Innovation] Available online at: https://rito.riigikogu.ee/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Vaimult-suureks.-%C3%9Chiskondliku-innovatsiooni-alused.-Kulbok-Lattik-Kaevats.pdf (accessed March 17, 2023).

30

Kulbok-Lattik E. Paulus K. Suurmaa L. (2023). Igal vallal oma ooper. Eesti rahvamajade lugu. [Each Municipality Has its Own Opera. The Story of Estonian Community Houses.]Tallinn: MTÜ Eesti Rahvamajade Ühing.

31

Kulbok-Lattik E. Raud Ü. Saro A. (2021). “Arts and hobby education within the shifting paradigm of education: the Estonian case,” in Arts, Sustainability and Education. Yearbook of the European Network of Observatories in the Field of Arts and Cultural Education (ENO), eds. WagnerE.Svendler NielsenC.VelosoL.SuominenA.PachovaN. (Singapore: Springer), 73–96

32

Kultuuripoliitika (2014) Kultuuripoliitika = Kultuuripoliitika põhialused aastani. Tallinn: Riigi Teataja 2014, 2 .

33

Kurvits A. (1935). Rahvamaja: käsiraamat rahvamajade asutamise ja ülalpidamise, ruumide ja ümbruse korraldamise ja kaunistamise ning tegevuse juhtimise ja edendamise alal. [Community houses: a handbook on establishing and maintaining community houses, organising and decorating their premises and surroundings, and managing and promoting their activities.]Tallinn: Kirjastus kooperatiiv.

34

Kymlicka W. (2009). “Freedom and Culture, Multicultural citizenship. A Liberal Theory of Minority Right,” in Rahvuslus ja patriotism. Valik kaasaegseid filosoofilisi võtmetekste. [Nationalism and patriotism. Selection of key texts of modern philosophy], ed. PiirimäeE. (Tartu: Ülikooli eetikakeskus), 253–309.

35

Laclau E. Mouffet C. (2014). Hegemony And Socialist Strategy: Towards A Radical Democratic Politics. New York: Verso Books.

36

Lahti V.-M. (2019). Gaps in Our Bildung. Available online at: https://www.sitra.fi/en/publications/gaps-in-our-bildung/ (accessed February, 2020).

37

Martinelli A. (2005). Global Modernization: Rethinking the Project of Modernity. London: Sage.

38

Ojanen E. (2016). “Valkoliljojen maa ja aikakauden henki,” in Mikä ihmeen sivistys? eds JantunenT.OjanenE. (Critical Academy).

39

Pfeifere D. (2022). The issues of defining and classifying cultural centres. Sciendo Econ. Culture19, 2022. 10.2478/jec-20220013

40

Potts J. Hartley J. (2014). “Toward a new cultural economics of innovation,” in Conference Paper, Association for Cultural Economics International, Montreal, Canada.

41

Raun T. (2001). Estonia and the Estonians. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press.

42

Raun T. (2009). “Eesti lülitumine modernsusesse: ‘Noor-Eesti' roll poliitilise ja sotsiaalse mõtte mitmekesistamisel. [The Estonian Engagement with Modernity: The Role of Young-Estonia in the Diversification of Political and Social Thought],” in Tuna 2, Tallinn, 39–50.

43

Ruiz J. R. (2009). Sociological–discourse analysis: methods and logic. Forum: Qual. Social Res. 10, 26.

44

SDG United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (2015). Available online at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed 28 March, 2020).

45

SE21 “Eesti säästva arengu riikliku strateegia “Säästev Eesti 21” heakskiitmine,” in Riigi Teataja .

46

Sevänen E. Häyrynen S. (2018). “Collection “Art and the Challenge of Markets” Volume I,” in National Cultural Politics and the Challenges of Marketization and Globalization, eds V. D. Alexander, S. Hägg, S. Häyrynen, E. Sevänen (London, Palgrave MacMillan).

47

Statistics Estonia. Available online at: https://www.stat.ee/en/find-statistics/statistics-theme/population (accessed 20 December, 2023) .

48

Wittrock B. (2000). Modernity: one, none, or many? European origins and modernity as a global condition. Daedalus, Winter 2009, 129.

49

Wodak R. De Cillia R. Reisigl M. Liebhart K. (2009). The Discursive Construction of National Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Summary

Keywords

cultural policy, roles of community houses, COVID-19 pandemic, sustainability, regional development

Citation

Kulbok-Lattik E, Roosalu T and Saro A (2024) Cultural sustainability and Estonian community houses. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1305143. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1305143

Received

30 September 2023

Accepted

22 January 2024

Published

27 March 2024

Volume

6 - 2024

Edited by

Anita Kangas, University of Jyväskylä, Finland

Reviewed by

Svetlana Hristova, South-West University “Neofit Rilski”, Bulgaria

Tobias Harding, University of South-Eastern Norway (USN), Norway

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Kulbok-Lattik, Roosalu and Saro.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Egge Kulbok-Lattik egge.kulboklattik@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.