- School of Governance and Public Affairs, XIM University, Bhubaneswar, India

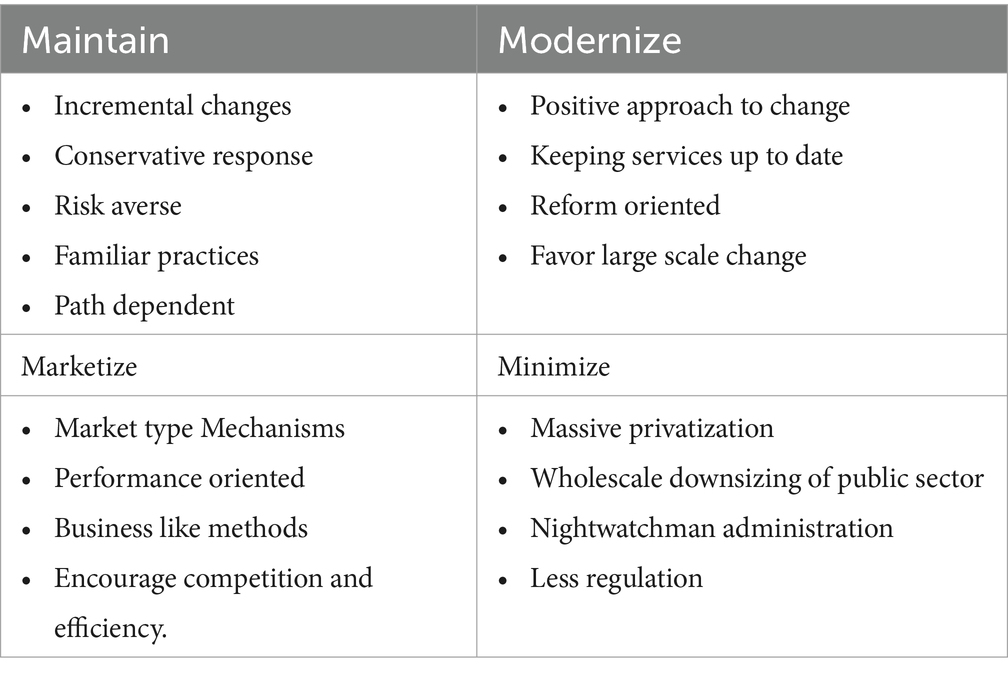

Public policy management has an intractable nature, and the institutional complexity of governance further exacerbates its practice. Transnational learning cutting across countries and policy areas can contribute to this policy knowledge in dealing with multifarious issues in public management. Understanding the institutional mix in public management in various contexts enhances the existing comprehension of how the national pattern of public management works differently in different socio-economic, cultural, and political settings. The present research aims to study the institutional framework in the form of state structure (unitary or federal) and the nature of executive government (majoritarian or consensual) in delineating the influence of institutions on public management processes in divergent policy systems. The paper undertakes four in-depth country case studies and the public management reforms as a response to institutional pressure are examined using the 4 M strategy–Maintain (holding on to existing administrative structures and processes), Modernize (keeping service delivery and regulation up to date), Marketize (efficiency and user-responsive public management), and Minimize (reducing state-led regulation). The case studies highlight the differences in the broad direction and energy of implementation that characterize a particular policy style. The results of the study indicate that even though the institutional dimensions are not present in strict polarization, the impact of the institutional mix is evident in the dominant strategies of public management reforms adopted at the national level.

1 Introduction

As a conceptual device, public management continues to dominate the scholarly discussion of the organization and management of public services by the executive governments. From a rational, hierarchical Weberian model of public management to the New Public Management and Digital era Governance, the nature of public management has become more complex and variegated (Ferlie et al., 2007). As a reflection of various governmental structures, bureaucratic capacities, cultural norms, and historical experiences, public management practises can vary considerably between nations and regions (Andrews, 2010; Brans et al., 2017). Therefore, in the academic study of public management, comparative and transnational assessment is of critical importance to uncover the nuances of public management practices.

There are several studies on public management systems in the developed world (Goldsmith and Eggers, 2004; Goldfinch and Wallis, 2009; Ongaro, 2009; Bianchi and Rivenbark, 2012; Joyce et al., 2014). Peters (2000) identifies four major state traditions: Anglo-Saxon, Continental European/Germanic, Continental European/French, and Scandinavian (a mix of Anglo-Saxon and Germanic). However, the comparative literature in the developing world is limited (Huque, 2001; Newcomer and Caudle, 2011; Ghrmay, 2020; Oszlak, 2022). Developing nations have not received scholarly interest because much of the literature on public management has been predominantly Anglo phone (Australia, United Kingdom, United States, and New Zealand). The Anglophone nations also seem to occupy key positions in the international agencies such as OECD and World Bank with considerable influence on other nations. Academicians and scholars have thus based their understanding of the public management in most nations on the Anglophone sources which suggest a convergence in public management reforms internationally. However, the true picture is far more varied. The trajectories of public management reforms have been significantly different in the various types of politico-administrative regimes in the developing world. There is a kind of long-term pattern that seems to follow the paradigm of new public management. But there are various domestic factors or specific mechanisms that lead to more than one path in public management. These mechanisms relate to the procedural rules, institutional structures, and cultural norms that dominate the management of public affairs in a particular nation.

While there are a host of factors that contribute towards the success or failure of new public management reforms, it is the institutional dynamics of a nation that have influenced and shaped the public management reform trajectory in a major proportion. Rather than being situation- or actor-specific, institutions are part of formal structures that are neutral organizations founded on rules. Institutions are thus essential to public management because they provide the framework, guidelines, and operating procedures required for efficient governance and the provision of public services (DiMaggio and Powell, 1991).

The main aim of this paper is to compare diverse countries spanning a large geographical space and opening a new scope for comparing the public management systems based on institutional diversity rather than the level of development. In addition to the diverse geographical setting, the study covers the four nations of Israel, Brazil, Nepal, and Philippines as they reflect the four combinations of unitary-federal and consensual-majoritarian regimes. In the comparative research on public management reforms, the work of Pollitt and Bouckaert is considered authoritative. The 4 M (maintain, modernize, minimize, marketize) model provides a holistic framework for analyzing public sector management reforms, addressing key aspects related to management practices and outcomes that define the overall thrust of the public management system. Each “M” represents a distinct strategy or orientation that can guide decision-making and organizational behavior within the public sector. Additionally, the 4 M model of the reform trajectories in the public management systems has not been applied in the developing countries context. Most studies look at countries with similar levels of development in a limited geographical range. In other words, there is a wide scope to expand the study of diverse policy systems based on the 4 M model for the academic and theoretical enrichment of public management studies.

The paper is divided into five sections. The following section deals with the review of literature outlining the evolution of public management and delineating the institutional framework as well as the public management theoretical framework given by Pollitt and Bouckaert (2017) that is used in the present study. The third section covers the case selection briefly describing each of the four country case studies and the data used to evaluate their public management reform strategy. The fourth section outlines the results of the comparison of the four nations based on the 4 M strategy of public management reforms. The last section discusses the overall role of institutions in public management reform as well as the application of 4 M strategy in institutionally diverse nations.

2 Literature review

A large and growing literature has focused attention on the continuing evolution of the thinking and practice of public management. Beginning from the traditional model of public administration to the new models of public governance, the field of public management has always responded to new challenges and the shortcomings of the previous approaches. In response to the significant market failures, the difficulties of urbanization and industrialization, the emergence of the modern corporation, and the trust in science and development, traditional public administration (Stoker, 2006; Waldo, 2007) emerged in the United States in the late 1900s and developed fully by the mid-1900s. Strong faith in government as an agent for the common good was established by the largely positive experiences with government responses to World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II. Politics and administration were kept separate (Wilson, 1887). Through their creation and accomplishment of politically determined goals, government institutions served as the main providers of value to the public (Salamon, 2002).

Scientific management, pragmatism, and synoptic rationality (Nelson, 1985; Schracter, 1989; Bryson et al., 2014) formed the philosophical and epistemological underpinnings of traditional public administration. The works of Henry Fayol, Frank J. Goodnow, Leonard D. White, and W. F. Willoughby also supplemented the traditional paradigm of public administration. Within the traditional model of public administration, the Weberian model of bureaucracy remained widely dominant for a longer period. Numerous scholars engaged with and expanded upon Weber’s ideas over the years (Merriam, 1926; Wallace, 1941; Sayre, 1958; Van Riper, 1987). The hierarchical structure, specialization, and adherence to rules espoused by Weber influenced the efficiency and rationalization within bureaucratic structures in many nations (Gerth and Mills, 1946; Rheinstein, 1954). The traditional public administration, therefore, prioritized distinct administrative responsibility and control lines, highlighted the public agency as the fundamental analytical unit, clearly distinguished between the public and private sectors, maintained the separation of policy and administration, and heavily stressed upon the command-and-control abilities of public agencies (Appleby, 1949; Wallace and Kaufman, 1960; Downs, 1967; Pressman and Wildavsky, 1973). Naturally the traditional public administration was always more intermeshed with politics than its idealized portrayal implied (Denhardt and Denhardt, 2011), and government organizations themselves were prone to failing (Wolf, 1979).

While the Weberian model of public administration continued to garner scholarly interest, a deeper intellectual analysis revealed its shortcomings, particularly in the face of the new and emerging organizational environments (Nass, 1986; Page, 2003; Bartels, 2009). Osborne and Gaebler (1992) made the case that bureaucratic governance had been suitable for the circumstances that prevailed up to the 1960s and 1970s. However, those circumstances vanished, and new regimes of governance had started to appear, initially locally and later globally. It came to be recognized that traditional administration is deeply antidemocratic, centralized, insular, self-protective, stiff, sluggish, and rule-bound (Barzelay, 1992; Garvey, 1995). As a result, the traditional model of public administration was discredited both in theoretical and practical terms. Hierarchical arrangements were considered good only for standardization and control but not for efficiency, accountability, and innovation (Hughes, 2003).

Several studies built upon the gaps of traditional public administration dominated by Weberian bureaucracy and called for a broadening of the field from ‘administration’ to ‘management’ (Holmes and Shand, 1995; Mintzberg, 1996; Borins, 1999; Mathiasen, 1999; Terry, 1999; Lindquist, 2000; Behn, 2001). The turn of the century witnessed a boom in the field of rigorous, multidisciplinary research on public management and public governance (Rainey and Steinbauer, 1999; Heinrich and Lynn, 2000). In the narrative of public management discourse, management, marketization, and reinvention came to play significant roles. Numerous and noteworthy post-traditional intellectual advancements have occurred in public management. The 1980s and 1990s saw the New Public Management (Hood, 1991; Barberis, 1998; Kaboolian, 1998) emerge as the dominant approach to managing public affairs. Fearing that governments were failing, believing in the efficiency and effectiveness of markets, believing in economic logic, and moving away from big, centralized government agencies in the direction of devolution and privatization were the main causes of the rise of New Public Management. The new forms of public action (Felts and Jos, 2000; Salamon, 2002) necessitated the shift of focus from public agency to diverse actors and from the bureaucratic methods to the diverse tools or instruments used in public management (Linder and Peters, 1989; Meier and O’Toole, 2011; Lapenta et al., 2012).

The public management reform model that was subsequently established placed a great deal of emphasis on the features of the current administrative and political systems as determining factors in the management change processes. According to several studies in the field of public management (Savoie, 1994; Wollmann, 2003a; Lynn, 2006; Bouckaert and Halligan, 2008; Pollitt, 2013), a model or tool of management can have quite different outcomes depending on the context. While being conceptually the same, or at least comparable, management reforms take on distinct development patterns depending on the national, sectoral, or local environment in which they are implemented (Wollmann, 2003b; Schedler and Proeller, 2007). Fabbrini and Sicurelli (2008) assert that political systems have a major impact on governments’ capacity to make legislation as well as how they do it.

Particularly, the institutional and structural variations in the national political systems have significant impact on the public management practices and outcomes (Mahoney and Thelen, 2010; James, 2016). There has been significant diversity among approaches to the definition of the notions of institution and institutionalism (Scott, 1987). Institutions serve as a “representation of socially sanctioned, that is, collectively enforced expectations with respect to the performance of certain activities or the behavior of particular categories of actors” (Streeck and Thelen, 2005). Formal regulations, compliance protocols, and standard operating procedures that organize people’s interactions with different political and economic entities are among them (Hall and Taylor, 1996). According to this notion, institutions are “regularised practices that have a rule-like quality in that the actors expect the practices to be observed; and which are sometimes reinforced by formal sanctions” (Hall and Thelen, 2008). Theories of institutions initially developed in the context of economic institutions and their impact on growth. The seminal works are Downs (1967); Black (1958); Buchanan and Tullock (1962); Arrow (1963); Olson (1965); and Niskanen (1971). Building on the foundation of economic dimension, institutional theory subsequently captured the attention of political scientists who theorized on public institutions and policy choice (McKelvey, 1976; Shepsle, 1979; Riker, 1980; Miller and Moe, 1983; Enelow and Hinich, 1984; Tsebelis, 1995 and Krehbiel, 1996).

In public management, public institutions play a dual role - as change agents and objects of change (Hammond and Knott, 1999). The policy capacity of a state is seen to be contingent on the structural arrangements of the political system (North and Weingast, 1989; Menahem and Stein, 2013; Mukherjee et al., 2021). Scholars have explored the role of institutions across a wide variety of themes, including institutional development, the interaction of formal and informal rules in organizational settings, and organizational legitimacy (Hambleton, 1983; Baez and Abolafi, 2002; Barzelay, 2003; Wanna et al., 2021). Several studies find that institutional context (both formal and informal) plays a role in the constraints and opportunities faced by public managers in devising strategies to navigate and improve public management practices (May, 2005; Scott, 2008; Jacobs and Matthews, 2017). The aspects of institutional isomorphism and the pressures to conform to institutional norms and practices have also been studied to uncover the tendency of public management within a field or sector to become similar in structure, practices, and behavior (Hall and Taylor, 1996; Larimer and Peterson, 2019).

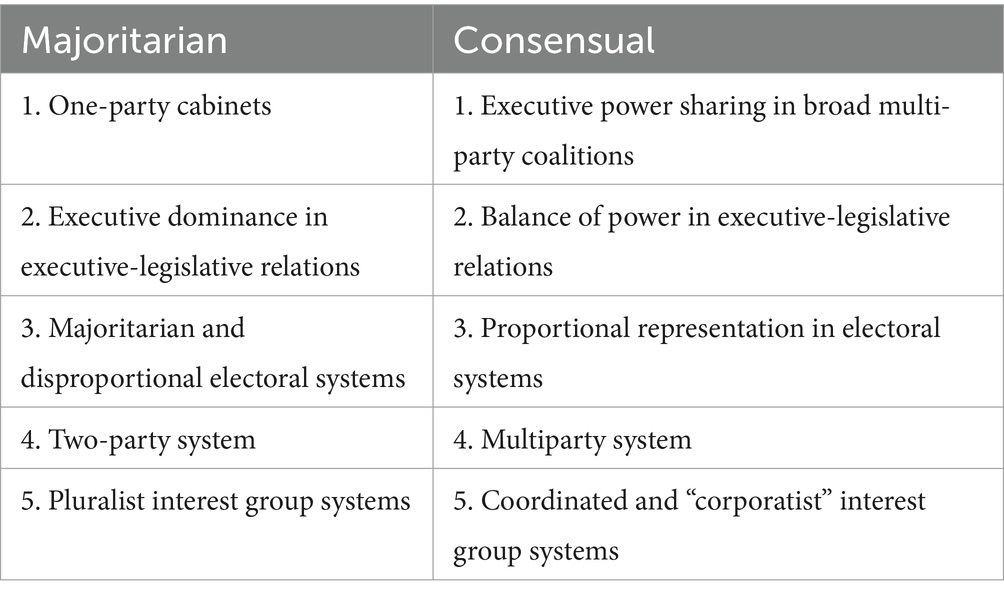

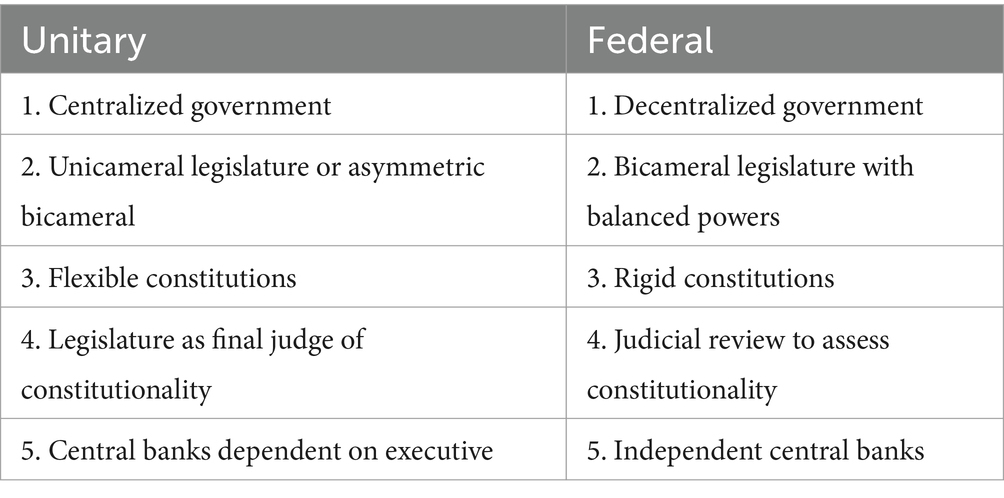

Relying on the corpus of comparative research work in the field of politics and public administration, the two features that serve as the most illuminating basis for comparing nations are the state structure as unitary or federal (Wright, 1975; Lester, 1986; Sabatier, 1986; Imperial, 2023) and the nature of the political executive as majoritarian or consensual (Lijphart, 1985; Anderson and Guillory, 1997; Scruggs, 1999; Croissant, 2002). As noted by Linder (1989, 1994) the institutional framework of unitary-federal and majoritarian-consensual system forms an important aspect of the governance style and public management processes adopted by a nation. The unitary system with its concentration of political power in the union level institutions leads to a centralized, hierarchical, top-down style of public management (Andrews and Boyne, 2010; Ramay and Babur, 2020). On the other hand, public management in a federal state structure is characterized by a more decentralized and diverse approach and involves navigating the balance between regional and national interests (Krane, 1993; Christensen and Wise, 2009). There is interjurisdictional cooperation and competition in a federal setting which leads to participative style of governance (McGuire, 2006; Holtmann and Rademacher, 2016; Daniell and Kay, 2017). A majoritarian political executive often prioritizes policy consistency and coherence (Persson and Tabellini, 2004). It can implement its preferred policies and maintain a unified approach across different areas of public management. This consistency can result in clear directives, streamlined procedures, and efficient implementation of policies. However, Majoritarian political executives may be more prone to centralization of power and populism (Geissel and Michels, 2018; Dussauge-Laguna, 2022). On the other hand, negotiation, compromise, and consensus-based decision making characterizes a consensual political executive (Dryzek, 2010). Scholars find that a consensual political executive often results in policy moderation and balance and extreme or polarizing policy options are more likely to be tempered or mitigated (Bogaards, 2017; Bernaerts et al., 2023). With multiple parties involved in the political executive, there is a greater potential for checks and balances in public management in a consensual style of governance (Dalton, 2008).

As the institutional and cultural differences and their impact on public management became more and more apparent, the body of knowledge in comparative public management also started to intensify (Heady, 2001; Manning and Parison, 2004; Jreisat, 2011). Several methodological and conceptual frameworks have been developed to make a comparative analysis of the public management reforms (Gerring, 2007; Farazmand, 2009). Adopting a broad comparative perspective, scholars have been looking for the national trajectories of public management reforms with a discernible pattern of similarity and differences (Pollitt, 2007). With the spread of new public management and the new methods of policy implementation, the success or failure of the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of different government regimes has been enriching our analysis by uncovering the range of implementation styles. Comparative research recognizes the complexity and challenges inherent in conducting sound research across countries (Eglene and Dawes, 2006). Rather than a common pattern in cross national comparison, the clear and pure types of public management reforms are more an exception. Still, while acknowledging the intractable and poorly specified nature of reform trajectories in comparative public management, the need to record and analyze the broad energy and direction of implementation is also regarded as worthy of academic study. Pollitt and Bouckaert (2017) developed the 4 M model of public management reform trajectories that stands for Maintain, Modernize, Marketize, and Minimize. Variants of politico-administrative regimes can thus be analyzed using the 4 M model that reflects the four ideal types of public management reform trajectories. Although the actual reforms defy pure polar types and represent a mix of different types of strategies for public management, the 4 M model has a heuristic value in reflecting the underlying assumptions and values held by political leaders and policy executives.

3 Developing country case studies

3.1 Case selection

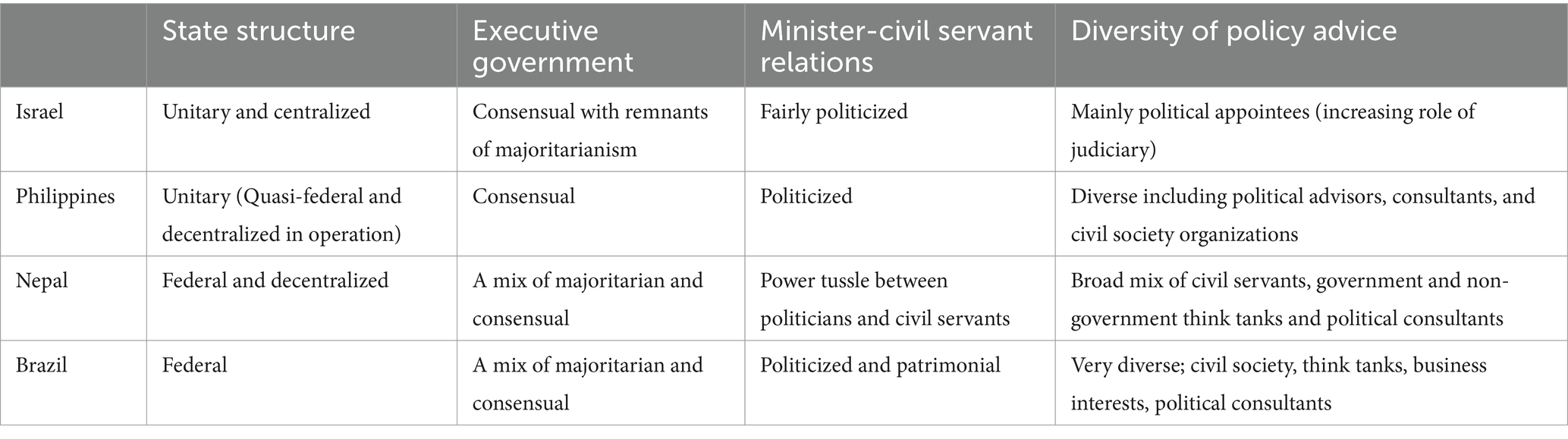

In order to explore the scope or universality of the 4 M model of public management reform trajectories across nations, the paper has selected diverse political systems along the two dimensions of state structure and nature of political executive. As a comparative research study, the aim is to study the generality of the 4 M strategy as a framework of public management strategy in divergent policy systems (Table 1). The study takes into consideration two dimensions – state structure (unitary-federal) and nature of political executive (majoritarian-consensual) (Tables 2, 3). The state structure reflects how authority is shared at different levels of government as well as the diffusion or concentration of political power in terms of either the vertical dispersion/concentration of authority or the horizontal coordination/fragmentation of authority. The second dimension of the nature of executive government refers to the working habits and entrenched conventions of the government. Comparative political scientists (Steiner, 1971; Powell, 1982, 2000; Lijphart, 1984) have developed the typology to capture the speed, scope, and intensity of public management reforms. The categories are not to be seen as water-tight compartments. The broadly majoritarian governments tend to behave in consensual manner and the broadly consensual governments tend to behave in majoritarian fashion (Table 4).

Comparing similar countries or countries from the same geographical region may obscure the more significant nature of transnational disparities. Therefore, the study has selected countries with a wider geographical range. Brazil is situated in Latin America; Nepal in South Asia; Israel in the Middle East region; and Philippines in the Southeast Asia (Figure 1). Apart from variations in the state structure and nature of political executive, these countries also differ vastly in their socio-economic and cultural dynamics.

3.1.1 Israel

The state of Israel was founded on a very unitary and centralized political structure that was devoid of any regional component (Elazar, 1977). The central government, which is composed of a coalition of parties, chooses how much authority to assign to different local organizations. Central authorities exercise strong budgetary control and make policy choices, which are then carried out by local authorities with limited discretionary power (Yonah, 2000). The legislative power resides in a unicameral parliament (Knesset) and the constitution is largely flexible (Weill, 2023). Based on proportional representation, Israel’s political structure permits several parties. Over the years, the requirement to forge coalitions and reach consensus in the Israeli political system tempers the majority-rule impact but not fully. As the leader of the coalition in power, the prime minister has a big say in determining the government’s goals and defining the policy agenda. The politicization of civil service has prevented the latter from acting as a catalyst for change (Cohen, 2016). There is a lack of institutional autonomy, public endorsement, and consistency within the Israeli civil service (Beeri, 2021). The judiciary has been increasing its oversight and involvement in policy advice to compensate for the influence of partisan politics in policy making.

3.1.2 Philippines

The Philippine government had been a democratic unitary presidential constitutional republic till the call for federalism arose amidst the political and economic dominance of Manila over other regions (Lasco, 2015). The nature of political system is best described as an operative quasi-federal system that has moved away from a strictly unitary political system (Tigno, 2017). The country is governed by a rigid constitution that is equally applicable throughout. The electoral system is a mix of plurality and proportional representation. The multi-party system is weak and incoherent as it is dominated by patronage and personality orientation (Quimpo, 2007). The civil service is politicized and is inflicted with graft, red tape, and inefficiencies in public service delivery (Brillantes and Fernandez, 2010). Despite being a unitary state, the Philippines has a decentralized policy style known as “local autonomy” or “a kind of maximum decentralization, short of federalization.” The Senate and the House of Representatives make up the Philippines’ bicameral legislature. Through citizen participation in decision-making, public consultations, and participatory budgeting throughout time, the Philippines has adopted the concepts of consultative government.

3.1.3 Nepal

According to the country’s 2015-adopted constitution, Nepal is formally a federal democratic republic. The provincial assemblies in each province are elected, while the National Assembly and House of Representatives make up the bicameral federal parliament. Like many other parliamentary systems, Nepal’s political executive dominates in several different ways. The Prime Minister and the cabinet play crucial responsibilities in recommending and carrying out laws and public policy, and the executive branch has significant policymaking authority. In the multi-party competition through a mix of plurality and proportional representation, the party with a majority in the House of Representatives forms the government and has relatively easy access to making decisions and developing policies. The civil service in Nepal is unable to function efficiently due to lack of support from the political leaders and the struggle for power over policy management (Paudel and Gupta, 2019). Nepal has a strong civil society with organized interest groups, non-governmental associations, the commercial sector, and unions (Pasanen et al., 2019). Nepal’s system aims to bring together the inclusiveness of a consensual system with the decision-making effectiveness of a majoritarian system (Bajpai, 2014).

3.1.4 Brazil

Brazil is a federal state with a bicameral legislature. The electoral system is a mix of proportional elections, plurality with single-member districts, and absolute majority with single-member districts (Mainwaring, 1991). The federal form of state and the electoral system has been leading to a weak multi-party system and proliferation of multiple interests and actors in policy making (Desposato, 2004). A diverse range of actors, including ministers, academics, staff members of NGOs and international organizations, are involved in the promotion, legitimation, mediation, and implementation of policies. By including a variety of stakeholders in the governance process, this participatory method promotes the development of consensus. However, the Brazilian state and the politico-administrative system is also described as patrimonial and extractive (Pereira, 2016). The provincial decrees have been used by the political executive branch to exert extraordinary power and influence over the legislature (Arberry, 2013).

3.2 Data collection

Case study research involves a combination of several data collection methods (Symonds and Ellis, 1945; Small, 2011). Owing to the different national level data collection methodologies, data from national level databases was not considered suitable for transnational comparison. The nations in the present study differ in their research and statistical data compilation capacity which leads to a lack of harmonized standards for the various categories of official statistics (Franchet, 1991). Therefore, the author has relied on data from international organizations such as the World Bank Group, Heritage Foundation, World Economic Forum, and World Intellectual Property Organization. The study also utilizes secondary data sourced from annual reports, archival databases, and national statistical accounts for analyzing the impact of institutional framework on public management in the respective nations. The country specific data on public management reforms is derived from the national level newspapers, government reports and official accounts.

4 Results

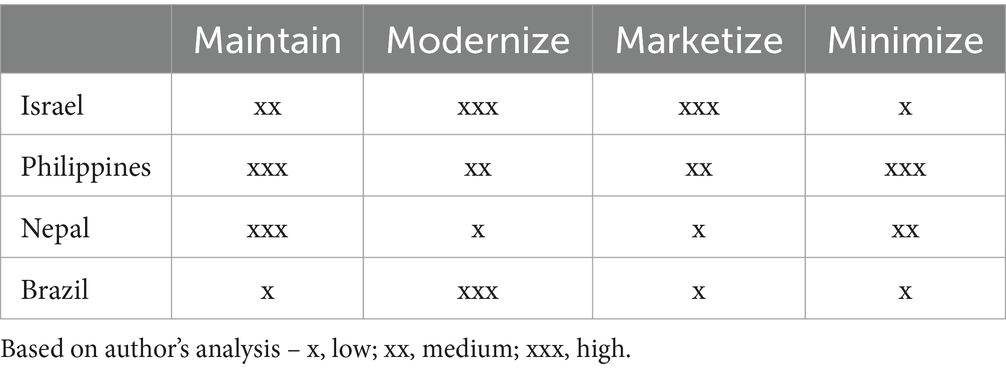

The study has endeavored to develop case study analysis for divergent policy systems in the four selected nations of Brazil, Israel, Nepal, and Philippines. Comparative assessment of the public management systems and the public management reform trajectories of these nations reveals a mix of the 4 M strategies given by Pollitt and Bouckaert (2017).

4.1 Maintain

Maintain is a conservative reaction that seeks to adhere as closely as possible to the current modes of operation. Of course, these “existing ways” vary greatly between nations. The public management approach is characterized by an aversion to disruptive changes and placing stability and security ahead of prospective benefits or innovations. Public managers prioritize prudence and reduce exposure to potential dangers resulting in a risk-averse management style. Due to worries about possible negative outcomes, risk-averse public managers may be reluctant to implement new policies, programmes, or technology. Instead of adopting novel and unproven techniques, they would rather stay with conventional strategies and approaches– tightening up rather than fundamental restructuring. In determining the path dependency and the tendency of governments to maintain the status quo in public management with only incremental changes, three main aspects are investigated. Firstly, whether the nation has followed a top-down or a bottom-up public management. Secondly, if the nation has created new structures or institutions to reform the public management. And lastly, if the nation has pursued changes or reforms in public management through a majoritarian or consensual approach.

Although there are some elements of both top-down and bottom-up approaches to public governance, Israel has a predominantly top-down government style. The unitary institutional framework of Israel is widely seen as an important factor for its top-down nature of policy formulation and implementation. The middle eastern nation has undertaken several efforts, created new organizations and structures, and improved administrative effectiveness to change public management such as the Government Companies Authority (GCA); the Efficiency and Innovation Authority; the National Economic Council; and the Digital Government Initiative. However, the extreme centralization, secrecy, territorial protection, and tradition of improvisation in Israel’s political-administrative culture have an impact on decision-making and management. Most reforms in Israel are carried out in majoritarian manner. Brazil’s long tradition of social movements and social justice advocacy has encouraged bottom-up efforts and citizen involvement in crafting governmental policy. A decentralized government is possible because of the nation’s federal framework. The Ministry of Economy was created in Brazil in 2019 with the merger of numerous ministries. Through this consolidation, the government hoped to improve cooperation and efficiency in the creation of economic policies and public administration while also streamlining government operations and reducing bureaucracy. Additionally, the Brazilian Investment Partnerships Programme (PPI), the Federal Secretariat of Digital Government, and the National School of Public Administration (ENAP) are new organizations for public management. Brazil’s multi-party coalition system constrains a predominantly majoritarian approach to public management reforms. However, in the interaction between the legislature and the executive, the type of management style that dominates (leadership, cooperation, or impasse) is seen to be dependent on a particular reforms’ content. Nepal is a unique case of public management reform. While the shift towards federalism has reduced regional inequalities, advanced inclusiveness, and strengthened local authority, the top-down mode of policy implementation still exists to a large extent. While new structures have been created for public management in Nepal (National Planning Commission; Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority; Good Governance Committees; and Digital Governance Initiatives), the political instability and the path dependent bureaucratic culture has constrained the development of citizen-centric approach to public management. Nepal’s fledgling democracy is yet to adopt a fully consensual reform approach. Philippines again has a top-down model of public management with extreme centralization of formal decision-making processes. The Philippines has started reforms in the areas of public procurement, bottom-up budgeting, the seal of good (local) governance, reducing red tape, and the citizen satisfaction index system in recent decades. But in the Philippines, the issue of public sector performance is still a persistent and long-standing worry. Government operations are hampered by corrupt practises, and nepotism harms the nation. The nation fits well with Riggs prismatic model as the gap between legal norms and actual functioning is quite large. While Philippines political executive is characterized as consensual, in practice, it is marked by covert majoritarianism driven by nepotism and oligarchic patrimonialism.

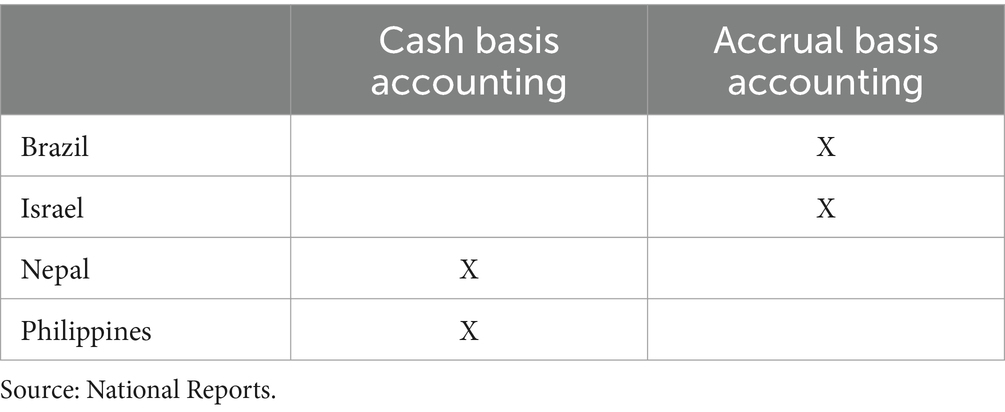

The budget practices of a nation can also reveal the extent of conservative management technique. Accounting techniques that are used to record and present financial transactions include the cash basis and accrual basis. Even though they are generally employed for financial reporting within businesses, when used in government accounting, they may provide light on a country’s financial situation and management style. Table 5 provides the prevalence of cash-based or accrual-based accounting systems in the four nations. While Brazil and Israel have adopted accrual systems in national accounting, Nepal and Philippines use the cash-based system. The move towards the accrual system reflects a break from the traditional cash-based system.

4.2 Modernize

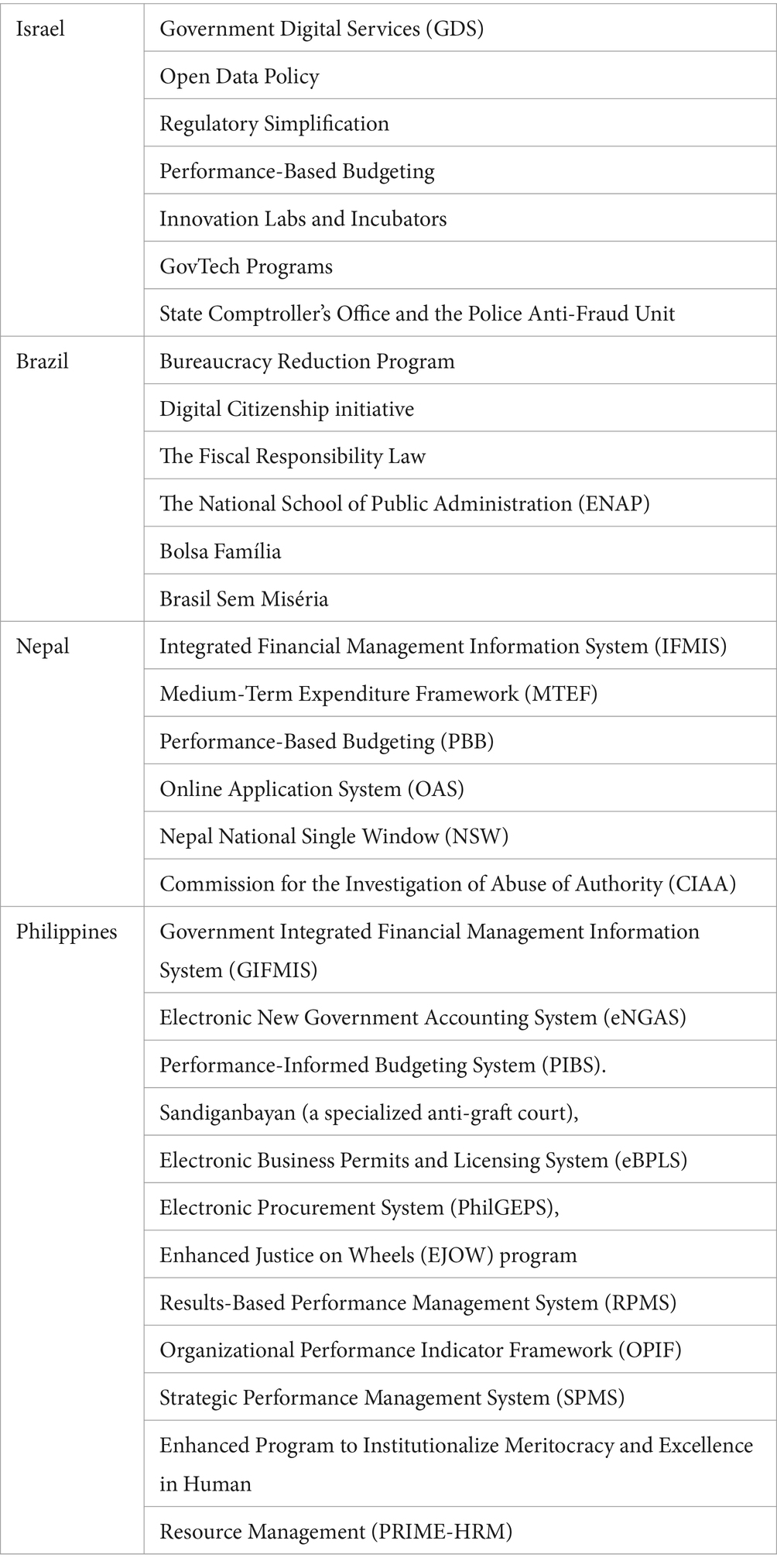

In line with the new public management and subsequent developments in the field of public management, nations have made fundamental changes in modernizing the public service delivery system. In an endeavor to maintain the state apparatus completely professional and up to date, modernizers have an upbeat perspective towards change and see potential for greater services and better regulation if significant changes are undertaken. Such a strategy is predicated on the premise that the state machinery can be relied upon to produce strong policies and high-quality services if it is continuously modernized. The modernizing strategy recognizes the necessity for some pretty substantial reorganizations of the administrative structure. These modifications typically included budget changes that moved towards some form of results- or performance-based budgeting, a loosening of personnel restrictions (though not necessarily a giving up of the idea of a distinct career in public service), extensive decentralization and delegation of authority from central ministries and agencies, and a reinforced devotion to improving the quality and adaptability of public services to citizens. There are various modernization strategies employed by this group of modernizers, such as managerial modernization (which focuses on management structures, instruments, and strategies) and participatory modernization (which emphasizes developing user-responsive, high-quality services and avenues for public participation). Some of the reforms and initiatives undertaken by Israel, Brazil, Nepal and Philippines to modernize public management and governance are mentioned in Table 6.

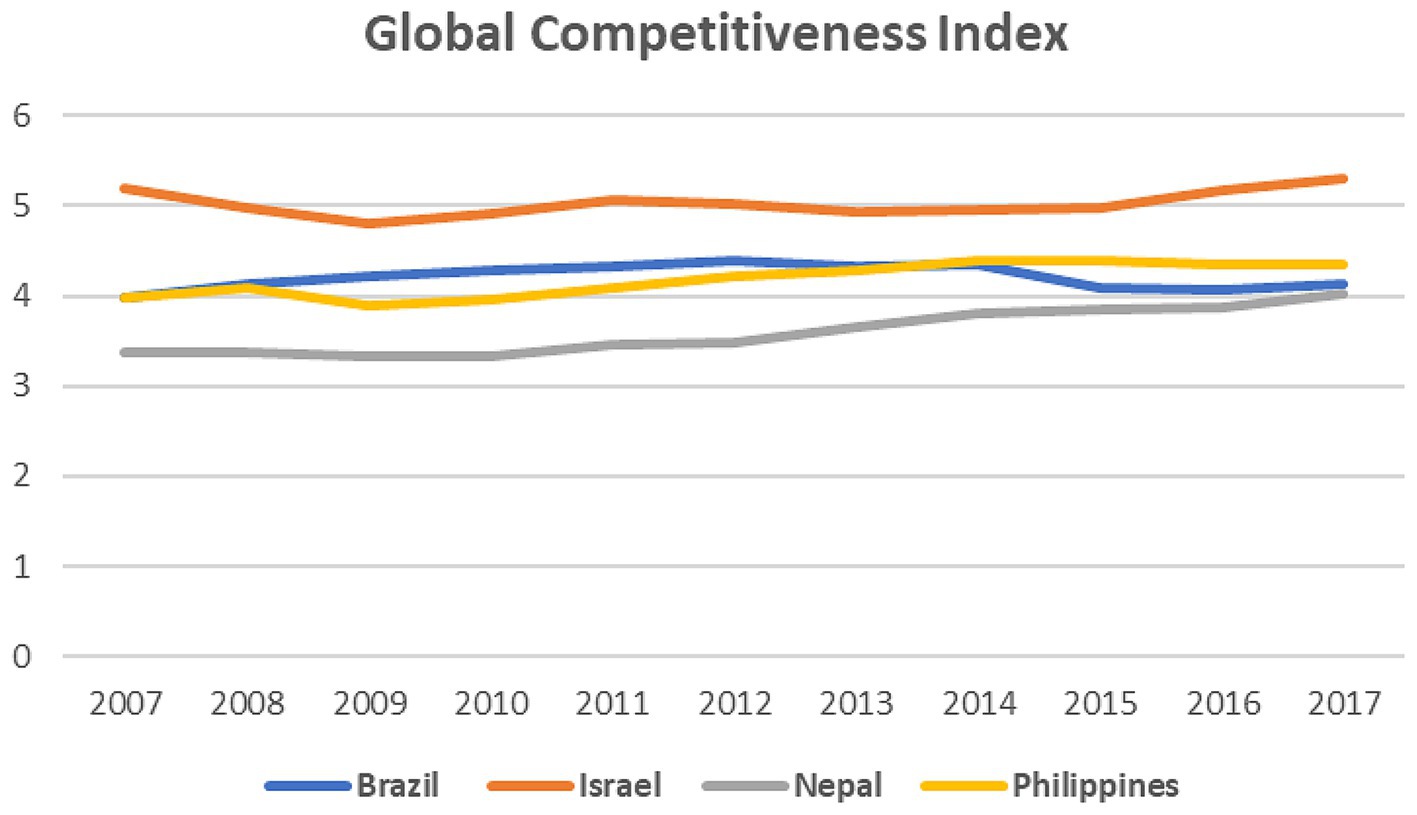

To make a comparative assessment of the modernizing tendencies in public management, global indices of innovation and competitiveness have been used. Figure 2 highlights the Global Competitiveness Index from 2007 to 2017. The World Economic Forum (WEF) releases a study every year called the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI). It gauges a nation’s competitiveness using a set of metrics that evaluate various facets of its institutional structure and economic performance. The GCI seeks to shed light on the elements that influence a nation’s productivity and long-term economic growth. Higher-ranked nations are regarded as being more competitive and modern in terms of their capacity to provide long-term economic growth. While it is no surprise to find Israel ranked the highest in GCI among the four nations, Brazil and Philippines have followed a very close trajectory in terms of global competitiveness. Nepal ranks lower consistently. Interestingly, Brazil and Philippines have their consensual political executive in common.

Figure 2. Global Competitiveness Index in Brazil, Israel, Nepal, and Philippines (2007–2017). Source: World Economic Forum Database.

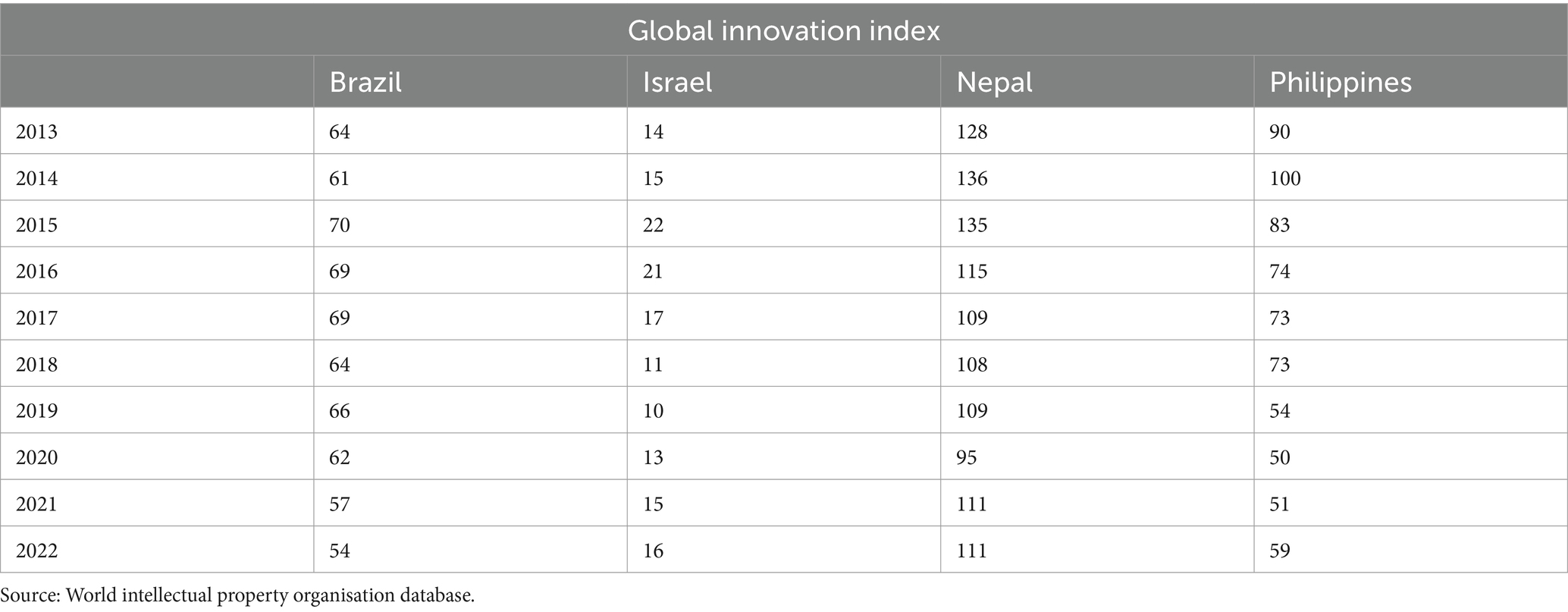

Table 7 showcases the Global Innovation Index from 2013 to 2022 for Israel, Brazil, Nepal, and Philippines. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), in collaboration with other partner organizations, publishes the Global Innovation Index (GII) as a yearly report. The GII assesses elements such institutional support, political and regulatory frameworks, the business climate, access to financing, education and research systems, infrastructure, and market circumstances in order to determine the enabling environment for innovation. These elements work together to affect a nation’s capacity to foster and maintain an environment that is favorable for innovation. Israel ranks in top 25 innovative nations as it offers a robust ecosystem that encourages innovation, which includes esteemed academic institutions, an active startup scene, and a welcoming entrepreneurial climate. Starting at low level, Philippines could rise rapidly in its innovation capacity to match the ranking of Brazil with the 55–61 range. GII ranking in Nepal has fluctuated between 95 and 136.

4.3 Marketize

Market-oriented reforms in public management have been the mainstay of New Public Management (NPM). In a reaction to traditional bureaucracy, business like management, market instruments, performance targets and incentives have been the dominant model of public management in most nations in the 1990s and the early twenty-first century. According to marketizers, market-type mechanisms (MTMs) hold the key to a public administration that is more effective and user-friendly. The introduction of private sector practises (which are thought to stimulate higher performance) into the public sector includes performance management, competitive tendering, contracting out, and “internal markets.” This reform-oriented mindset essentially involves a broad lowering of the public sector’s distinction from the private sector.

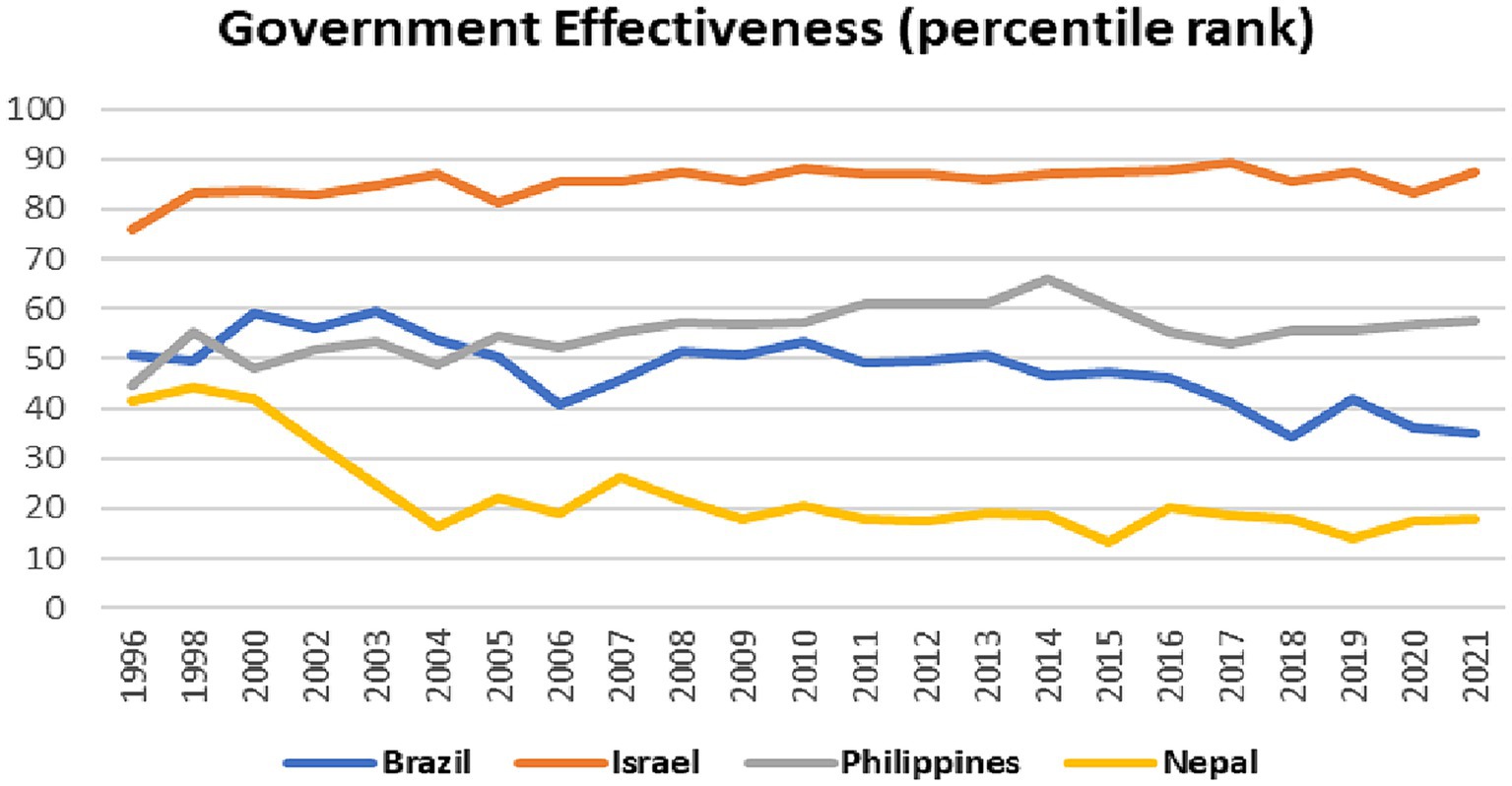

In all four nations, public-private partnerships (PPPs) have been used in infrastructure projects to use the resources and skills of the private sector in in Transportation; Water and Sanitation; Energy; Healthcare; Education; and Tourism sectors. To ensure accountability and motivate service providers to provide desired results, performance-based contracts have been implemented in public management. User fees and cost recovery methods have been adopted in several industries, especially the healthcare sector to lessen the need for government subsidies. Market-like procedures have been created via regulatory changes in industries including telecommunications, energy, and finance. Government organizations frequently hire private companies to carry out tasks like facilities management, IT support, or maintenance. A comparable global dataset pertaining to the marketizing extent in public management is not available. However, considering the fact that marketization of public management lead to better delivery of services, the author utilizes the government effectiveness index as a measure of market like efficiency in public sector. Figure 3 shows the percentile rank of government effectiveness as a measure of quality of governance in the four nations. While Israel and Philippines have been able to improve government effectiveness, albeit marginally from 1996 to 2021, the nations of Brazil and Nepal have been on the downward trajectory.

Figure 3. Government effectiveness in Brazil, Israel, Nepal, and Philippines (1996–2021). Source: World Bank Database.

4.4 Minimize

Minimizers in public management want to reduce the state machine because they are essentially dubious about it. The primary method for doing this is through large-scale privatization, together with persistent attacks on “red tape” and innovative practises to discourage authorities from enacting more rules than are strictly required. The style of governance opposes big government and supports a minimal nightwatchman public administration in the laissez faire manner. Downsizing and deregulation of the public sector is the main strategy to reduce the role of the state in the economy.

There is some overlap between the strategies adopted to marketize and minimize such as the contracting out of government services and public-private partnerships. However, the minimizing public management style is to remove the presence of government or public entities from service delivery and citizen welfare rather than making the government market-like.

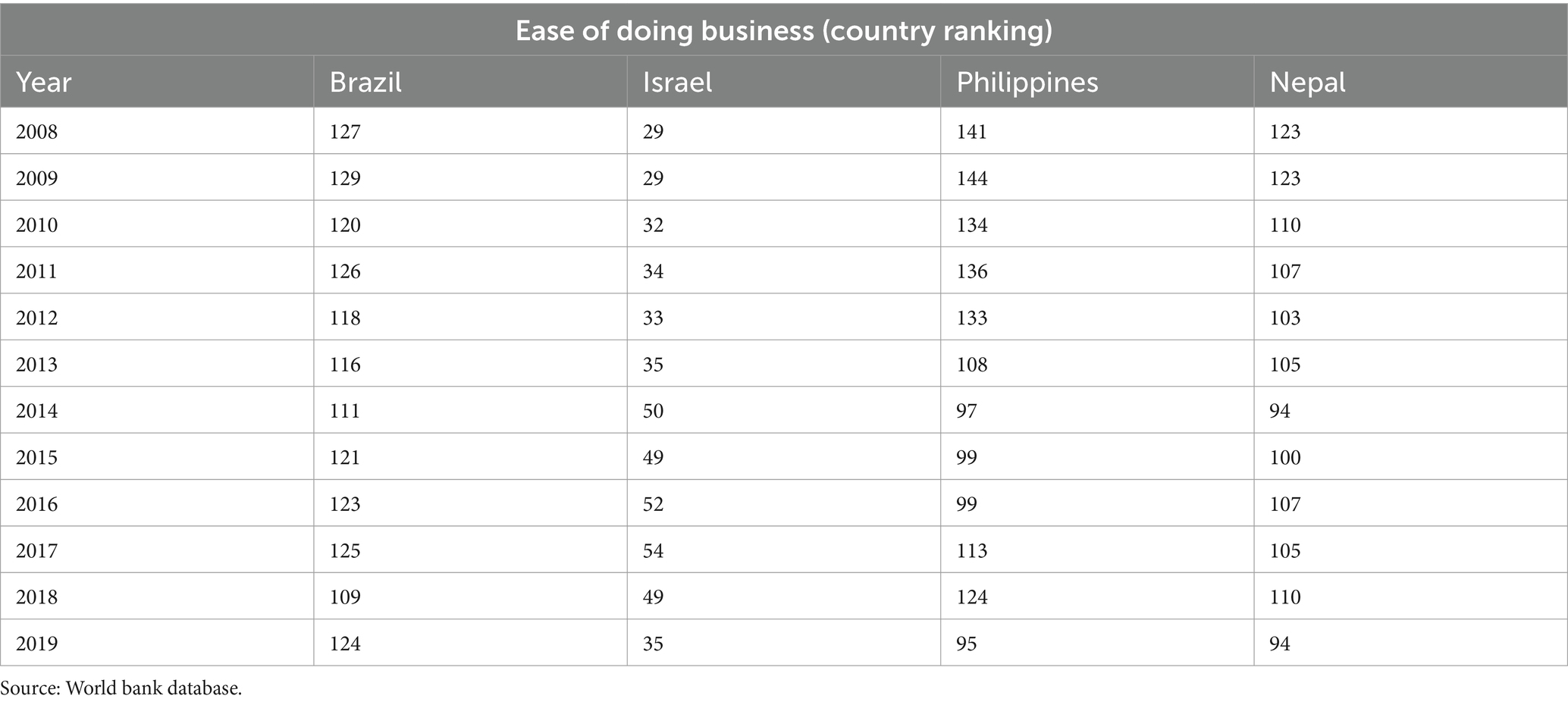

The World Bank Group developed the Ease of Doing Business (EoDB) index, a grading system that offers useful insights into a country’s regulatory environment and business friendliness. Ease of doing business rates economies from 1 to 190, with 1 being the easiest to conduct business in. Usually, the higher rank also reflects stronger safeguards of property rights and better, typically simpler, regulations for enterprises. Israel ranks high compared to Brazil, Philippines, and Nepal. While Philippines and Nepal have improved their ranks over the years, Brazil has not been able to move much higher in the ranking (Table 8).

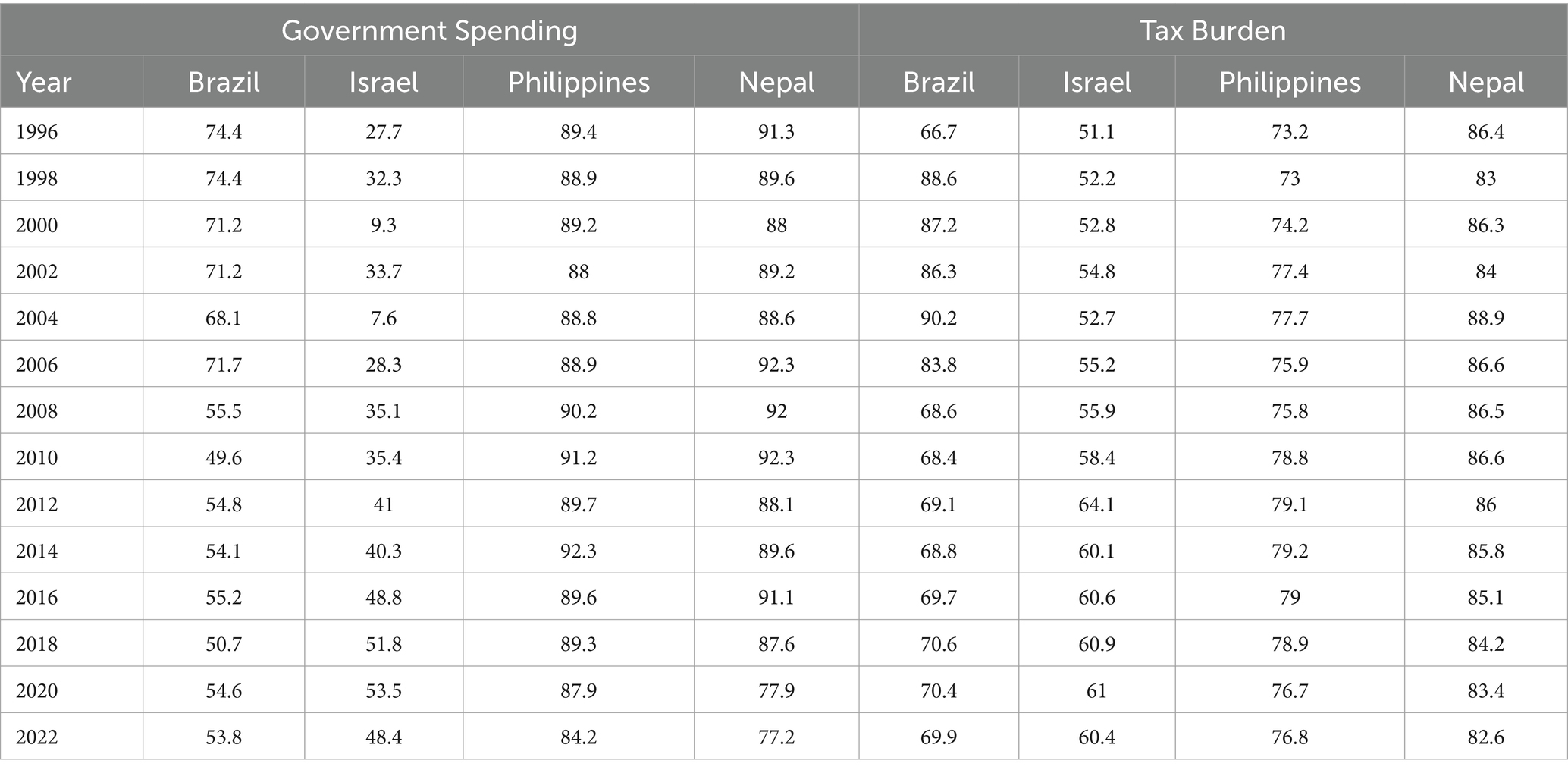

Another measure of minimizing public management is the government size. The index of economic freedom published by the Heritage Foundation captures the pillar of government size through government spending and tax burden. For a minimizing public management approach, the government size should be less for efficient service delivery.

Government spending is financed by high taxes and involves an opportunity cost, which is the worth of the consumption or investment that would have taken place had the resources been left in the hands of private entities. Government spending in Philippines is the highest, followed by Nepal, Brazil, and Israel. The extent of government involvement is also measured by the tax burden. High tax burden implies more government and less economic freedom. Tax burden is highest in Nepal followed by Philippines, Brazil, and Israel (Table 9).

5 Discussion and conclusion

From the comparative analysis of public management reform trajectories in the four selected countries, a few findings are evident. The four nations have displayed different extents of the 4 M strategies of public management reforms (Table 10). The study has attempted to situate the findings within the broader context of the institutional framework. The two institutional dimensions of unitary-federal and majoritarian-consensual shape up distinct public management reform trajectories in the selected nations that underscores the link between institutions and the direction and intensity of public management reforms.

5.1 Unitary-consensual and public management

The two unitary nations of Israel and Philippines differ vastly in the dominant strategies adopted for public management reform. While Israel seems to have pursued modernizing and marketizing approaches to public management, Philippines has strived to maintain the past policy practices and minimize the involvement of state in public management. The inference that can be drawn is that the forces of marketization and modernization can grow and spread in a unitary and centralized state. The example of Israel and Philippines defies the institutional impact logic, but not fully. Israel and Philippines share the common features of a unitary state structure, a consensual political executive, and a politicized bureaucracy. However, there are remnants of majoritarianism in Israel and decentralization in Philippines. The degree of diversity in terms of the source of policy advice is narrow in Israel and wider in Philippines. Therefore, depending on how it is designed, the environment in which it operates, and whether there are competing interests, a public management system may or may not result in improved development.

5.2 Federal-majoritarian and public management

The federal states of Nepal and Brazil also have a different mix of public management strategies. Nepal seems to follow the dominant strategy of maintaining past policy preferences and to some extent minimizing the role of state in service delivery. Brazil follows a dominant modernizing strategy in public management. Nepal and Brazil share the common features of a federal polity; mix of majoritarianism and consensual political executive; and a high degree of diversity in policy advice. However, in Nepal the political control of bureaucracy is not very much entrenched. Additionally, Nepal is more decentralized and less majoritarian than Brazil. The comparison defies the logic that participative (in terms of diverse policy actors) style of governance aids in breaking away from traditional system of public management. Brazil has the advantage of the decisiveness of a majoritarian system. Decentralized governance, on the other hand, can constrain the modernizing tendencies in public management, as evident in Nepal.

The final observations defy a strong straightforward link between the institutional blend and the public management reform that prevails. Based on the individual country analysis, the trajectories taken by each country in its economic and political evolution since 1980 can serve as a possible explanation. Even as a unitary state, Israel has undergone a political cycle marked by a high degree of political polarization and existence of coalition governments. However, the economic modernization in Israel has been quite fast paced with a strong emphasis on technology, innovation, and integration into the world economy. Philippines has struggled to establish a stable democracy from the beginning, plagued with periodic instability, political corruption, and military dominance. Unlike Israel, the economic path of development has not been progressive in Philippines. Philippines economy has been stressed under inflation and unemployment because of natural disasters, global economic recession, and the uncertainty in the political landscape. Nepal has again had a fragile transition from monarchy to a federal democratic republic. Political turmoil continued behind the façade of multi-party democracy. This has led to the slow pace of economic modernization. The Nepalese economy has been reeling under the dependence on foreign aid and inadequate foreign investment to build the industrial and infrastructural foundation. The political development in Brazil has been marked by the recurring dominance of political corruption and coalition governments. Brazilian economy, however, has been less susceptible to political instability than Philippines and Nepal. The adoption of neo-liberal economic policies has resulted in a steady economic growth, albeit accompanied by inequality and environmental concerns.

To conclude, while the institutional mix in a nation can be a useful analytical framework to assess the kind of public management that dominates in a nation, there are many endogenous and exogenous factors that explain the reform trajectory. The economic and political cycles of stability, contraction or expansion can dilute or accelerate the tenor of public management reforms in seemingly convergent institutional arrangements. There is no watertight compartmentalization in the strategies adopted by national governments in managing public affairs. The institutional framework within which policy implementation takes place explains to some extent the broad style of public management reform. The world of public management and policy implementation has transformed radically since the new public management movement began in the late 1970s. The implementation of public policies and the overall thrust of government in public management differs vastly across nations. The present study calls for further research in appreciating diversity, identifying patterns, and developing a nuanced understanding of public management in diverse policy systems.

5.3 Limitations of the study and scope for future research

The study is a preliminary secondary data based comparative analysis of four nations. Lack of comparable data at global level is a major limitation in comparing nations. Further research is needed to compare nations following different institutional and policy mix at a wider scale.

Author contributions

VS: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson, C. J., and Guillory, C. A. (1997). Political institutions and satisfaction with democracy: a cross-National Analysis of consensus and majoritarian systems. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 91, 66–81. doi: 10.2307/2952259

Andrews, M. (2010). Good government means different things in different countries. Governance 23, 7–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01465.x

Andrews, R., and Boyne, G. A. (2010). Capacity, leadership, and organizational performance: testing the Black box model of public management. Public Adm. Rev. 70, 443–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02158.x

Arberry, Lance L. (2013). The Evolving Executive: Provisional Decrees and Their Impact on Brazil's Executive-Legislative Relationship. Honors College Theses. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/honors_theses/9

Baez, B., and Abolafi, A. M. Y. (2002). Bureaucratic entrepreneurship and institutional change: a sense-making approach. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 12, 525–552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003546

Bajpai, A. (2014). Public value’ as a normative framework: A comparative evaluation and recasting of administrative culture in India and Nepal. 23rd Congress of International Political Science Association (IPSA), Montreal, Canada, 1–20.

Barberis, P. (1998). The new public management and a new accountability. Public Adm. 76, 451–470. doi: 10.1111/1467-9299.00111

Bartels, K. P. R. (2009). The disregard for Weber’s “Herrschaft”: the relevance of Weber’s ideal type of bureaucracy for the modern study of public administration. Administrative Theory & Praxis 31, 447–478. doi: 10.2753/ATP1084-1806310401

Barzelay, M. (1992). Breaking through bureaucracy: A new vision for managing in government. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Barzelay, M. (2003). Introduction: the process dynamics of public management policymaking. Int. Public Manag. J. 6, 251–282,

Beeri, I. (2021). Lack of reform in Israeli local government and its impact on modern developments in public management. Public Manag. Rev. 23, 1423–1435. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2020.1823138

Bernaerts, K., Blanckaert, B., and Caluwaerts, D. (2023). Institutional design and polarization. Do consensus democracies fare better in fighting polarization than majoritarian democracies? Democratization 30, 153–172. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2022.2117300

Bianchi, C., and Rivenbark, W. C. (2012). A comparative analysis of performance management systems: the cases of Sicily and North Carolina. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 35, 509–526. doi: 10.2753/PMR1530-9576350307

Bogaards, M. (2017). “Comparative political regimes: consensus and majoritarian democracy” in Oxford research Encyclopaedia of politics. ed. W. Thompson (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Borins, S. (1999). Trends in training public managers: a report on a commonwealth seminar. Int. Public Manag. J. 2, 299–314. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7494(00)89039-X

Bouckaert, G., and Halligan, J. (2008). Managing performance: International comparisons. New York, NY: Routledge.

Brans, M., Geva-May, I., and Howlett, M. (2017). Routledge handbook of comparative policy analysis. 1st Edn: Routledge, Abingdon Oxon UK.

Brillantes, A. Jr, and Fernandez, M. T. (2010). Toward a reform framework for good governance: Focus on anti-corruption. Philippine Journal of Public Administration, 54, 87–127.

Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., and Bloomberg, L. (2014). Public value governance: moving beyond traditional public administration and the new public management. Public Adm. Rev. 74, 445–456. doi: 10.1111/puar.12238

Buchanan, J. M., and Tullock, G. (1962). The Calculus of consent: Logical foundations of constitutional democracy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Christensen, R. K., and Wise, C. R. (2009). Dead or alive? The federalism revolution and its meaning for public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 69, 920–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02041.x

Cohen, N. (2016). Forgoing new public management and adopting post-new public management principles: the on-going civil service reform in Israel. Public Adm. Dev. 36, 20–34. doi: 10.1002/pad.1751

Croissant, A. (2002). Majoritarian and consensus democracy, electoral systems, and democratic consolidation in Asia. Asian Perspect. 26, 5–39. doi: 10.1353/apr.2002.0022

Dalton, R. J. (2008). The quantity and the quality of party systems: party system polarization, its measurement, and its consequences. Comp. Pol. Stud. 41, 899–920. doi: 10.1177/0010414008315860

Daniell, K. A., and Kay, A. (2017). “Multi-level governance: an introduction” in Multi-level governance: Conceptual challenges and case studies from Australia. eds. K. A. Daniell and A. Kay.

Denhardt, J. V., and Denhardt, R. B. (2011). The new public service: Serving, not steering. 3rd Edn. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Desposato, S. W. (2004). The impact of federalism on National Party Cohesion in Brazil. Legis. Stud. Q. 29, 259–285. doi: 10.3162/036298004X201177

DiMaggio, P. J., and Powell, W. W. (1991). New institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dryzek, J. S. (2010). Foundations and frontiers of deliberative governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dussauge-Laguna, M. I. (2022). The promises and perils of populism for democratic policymaking: the case of Mexico. Policy. Sci. 55, 777–803. doi: 10.1007/s11077-022-09469-z

Eglene, O., and Dawes, S. S. (2006). Challenges and strategies for conducting international public management research. Administration & Society 38, 596–622. doi: 10.1177/0095399706291816

Elazar, D. J. (1977). “The compound structure of public service delivery systems in Israel” in Comparing urban service delivery systems: Structure and performance. eds. V. Ostrum and F. Pennel Bish (Beverly Hills: Sage), 47–82.

Enelow, J. M., and Hinich, M. J. (1984). The spatial theory of voting: an introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fabbrini, S., and Sicurelli, D. (2008). Bringing policy-making structure Back in: why are the US and the EU pursuing different foreign policies? Int. Politics 45, 292–309. doi: 10.1057/ip.2008.5

Farazmand, A. (2009). Building administrative capacity for the age of rapid globalization: a modest prescription for the twenty-first century. Public Adm. Rev. 69, 1007–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02054.x

Felts, A. A., and Jos, P. H. (2000). Time and space: the origins and implications of the new public management. Admin. Theory Praxis 22, 519–533. doi: 10.1080/10841806.2000.11643469

Ferlie, E, Lynn, L. E., and Pollitt, C. (2007). The Oxford handbook of public management. Oxford University Press.

Franchet, V. (1991). International comparability of statistics: background, harmonization principles and present issues. J Royal Stat. Soci. Ser. A 154, 19–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.1991.tb00269.x

Garvey, G. (1995). False Promises: The NPR in Historical Perspective. in D. F. Kettl & J. J. DiIulio Jr. (Eds.), Inside the Reinvention Machine: Appraising Governmental Reform (Washington, DC: Brookings), 87–106.

Geissel, B., and Michels, A. (2018). Participatory developments in majoritarian and consensus democracies. Representation 54, 129–146. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2018.1495663

Gerring, J. (2007). Case study research: Principles and practices. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gerth, H. H., and Mills, C. W. (1946). From max weber: Essays in sociology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ghrmay, T. M. (2020). New public management and path dependence in public organizations in Ethiopia: a multiple case study. in Public Administration in Ethiopia: Case Studies and Lessons for Sustainable Development. Eds. B. K. Debela, G. Bouckaert, M. A. Warota, D. T. Gemechu, A. Hondeghem, and T. Steen, et al. (Belgium: Leuven University Press), 251–278. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv19m65dr

Goldfinch, S. F., and Wallis, J. L. (2009). International handbook of public management reform. UK: Edward Elgar.

Goldsmith, S., and Eggers, W. D. (2004). Governing by network: The new shape of the public sector. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Hall, P. A., and Taylor, R. C. R. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Pol.l Stud. 44, 936–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

Hall, P. A., and Thelen, K. (2008). Institutional change in varieties of capitalism. Soc. Econ. Rev. 7, 7–34. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwn020

Hambleton, R. (1983). Planning systems and policy implementation. J. Publ. Policy 3:397. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X00007534

Hammond, T. H., and Knott, J. H. (1999). Political institutions, public management, and policy choice. J. Pub. Admin. Res. Theory 9, 33–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024406

Heady, F. (2001). Public administration: A comparative perspective. 6th Edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Heinrich, C. J., and Lynn, L. E. Jr. (2000). Governance and performance: New perspectives. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Holmes, M., and Shand, D. (1995). Management reform: some practitioner perspectives on the past ten years. Governance 8, 551–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.1995.tb00227.x

Holtmann, E., and Rademacher, C. (2016). Decentralization of power and of decision-making — an institutional driver for systems change to democracy. Hist. Soci. Res. 41, 281–298,

Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Adm. 69, 3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

Hughes, O. E. (2003). Public management and administration: an introduction. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Huque, A. S. (2001). Governance and public management: the south Asian context. Int. J. Public Adm. 24, 1289–1297. doi: 10.1081/PAD-100105940

Imperial, M. (2023). Implementation Structures: The Use of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches to Policy Implementation. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Available at: https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-1750 (Accessed June 15, 2023).

Jacobs, A. M., and Matthews, J. S. (2017). Policy attitudes in institutional context: rules, uncertainty, and the mass politics of public investment. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 61, 194–207. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12209

James, T. S. (2016). Neo-statecraft theory, historical institutionalism and institutional change. Gov. Oppos. 51, 84–110. doi: 10.1017/gov.2014.22

Joyce, P., Bryson, J. M., and Holzer, M. (2014). Developments in strategic and public management: Studies in the US and Europe. UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jreisat, J. E. (2011). Commentary -comparative public administration: a global perspective. Public Adm. Rev. 71, 834–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02434.x

Kaboolian, L. (1998). The new public management: challenging the boundaries of the management vs. Administration Debate. Pub. Admin. Rev. 58, 189–193. doi: 10.2307/976558

Krane, D. (1993). American federalism, state governments, and public policy: weaving together loose theoretical threads. PS. Pol. Sci. Polit. 26, 186–190. doi: 10.2307/419826

Krehbiel, K. (1996). Institutional and partisan sources of gridlock: a theory of divided and unified government. J. Theor. Polit. 8, 7–40. doi: 10.1177/0951692896008001002

Lapenta, A., Fattore, G., and Dubois, H. F. W. (2012). Measuring new public management and governance in political debate. Public Adm. Rev. 72, 218–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02497.x

Larimer, C. W., and Peterson, S. A. (2019). Biological approaches to public administration and public policy: introduction. Politics Life Sci. 38, 113–116. doi: 10.1017/pls.2019.19

Lasco, Gideon . (2015). Imperial Manila. Inquirer.net, December 28. Available at: http://opinion.inquirer.net/91545/imperial-manila.

Lester, J. (1986). “Intergovernmental relations and ocean policy: marine pollution, dumping, and incineration of hazardous wastes” in Ocean resources and intergovernmental relations. ed. M. Silva (Boulder: Westview).

Lijphart, A. (1984). Democracies: Patterns of majoritarian and consensus government in twentyone countries. London: Yale University Press.

Lijphart, A. (1985). Non-majoritarian democracy: a comparison of federal and Consociational theories. Publius 15, 3–15. doi: 10.2307/3329961

Linder, A. (1989). Democratic Political Systems: Types, Cases, Causes, and Consequences. Journal of Theoretical Politics 1, 38–48. doi: 10.1177/0951692889001001003

Linder, S. H., and Peters, B. G. (1989). Instruments of government: perceptions and contexts. J. Publ. Policy, 9, 35–58. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X00007960

Lijphart, A. (1994). Democracies: Forms, performance, and constitutional engineering. Journal of Political Research, 25, 1–17.

Lindquist, E. A. (2000). Reconceiving the center: leadership, strategic review and coherence in public sector reform OECD, Government of the Future, OECD Publishing, Paris. doi: 10.1787/9789264189775-en

Mahoney, J., and Thelen, K. (2010). Explaining institutional change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mainwaring, S. (1991). Politicians, parties, and electoral systems: Brazil in comparative perspective. Comp. Polit. 24, 21–43. doi: 10.2307/422200

Manning, N., and Parison, N. (2004). International public administration reform: Implications for the Russian Federation. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Mathiasen, D. G. (1999). The new public management and its critics. Int. Public Manag. J. 2, 90–111. doi: 10.1016/S1096-7494(00)87433-4

May, P. J. (2005). Regulation and compliance motivations: examining different approaches. Public Adm. Rev. 65, 31–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00428.x

McGuire, M. (2006). Intergovernmental management: a view from the bottom. Public Adm. Rev. 66, 677–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00632.x

McKelvey, R. (1976). Intransitivities in multidimensional voting models and some implications for agenda control. J. Econ. Theory 12, 472–482. doi: 10.1016/0022-0531(76)90040-5

Meier, K. J., and O’Toole, L. J. (2011). Comparing public and private management: theoretical expectations. J. Pub. Admin. Res. Theory 21, i283–i299. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur027

Menahem, G., and Stein, R. (2013). High-capacity and low-capacity governance networks in welfare services delivery: a typology and empirical examination of the case of Israeli municipalities. Public Adm. 91, 211–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.2012.02044.x

Merriam, C. E. (1926). American political ideas: Studies in the development of American political thought, 1865–1917. New York: Macmillan.

Miller, G. J., and Moe, T. M. (1983). Bureaucrats, legislators, and the size of government. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 77, 297–322. doi: 10.2307/1958917

Mintzberg, H. (1996). Managing government, governing management. Harvard Business Review, 74, 75–83.

Mukherjee, I., Coban, M. K., and Bali, A. S. (2021). Policy capacities and effective policy design: a review. Policy. Sci. 54, 243–268. doi: 10.1007/s11077-021-09420-8

Nass, C. I. (1986). Bureaucracy, technical expertise, and professionals: a Weberian approach. Sociol Theory 4, 61–70. doi: 10.2307/202105

Nelson, D. (1985). Frederick W). Taylor and the rise of scientific management. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

Newcomer, K., and Caudle, S. (2011). Public performance management systems: embedding practices for improved success. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 35, 108–132. doi: 10.2753/PMR1530-9576350106

North, D. C., and Weingast, B. R. (1989). Consti tutions and commitment: the evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. J. Econ. Hist. 49, 803–832. doi: 10.1017/S0022050700009451

Olson, M. Jr. (1965). The logic of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Osborne, D., and Gaebler, T. (1992). Reinventing government: How the entrepreneurial Spirit is transforming the public sector Reading. MA: Addison-Wesley.

Oszlak, O. (2022). Trends of public management reform in Latin America. Int. J. Public Adm. 45, 308–318. doi: 10.1080/01900692.2021.2008962

Page, E. C. (2003). Farewell to the Weberian State? Classical Theory and Modern Bureaucracy. J. Comp. Gov. Eur. Pol. 1, 485–504. doi: 10.1515/zfse.1.4.485

Pasanen, T., Befani, B., Rai, N., Neupane, S., Jones, H., and Stein, D. (2019). What drives policy change in Nepal? A comparative analysis. ODI Report. Overseas Development Institute (ODI), London.

Paudel, R. C., and Gupta, A. K. (2019). Performance in Nepali bureaucracy: What does matter? Research Journal of Economics 3, 1–6. https://bit.ly/3XGnJq1

Pereira, A. W. (2016). Is the Brazilian state “patrimonial”? Lat. Am. Perspect. 43, 135–152. doi: 10.1177/0094582X15616119

Persson, T., and Tabellini, G. (2004). Constitutional rules and fiscal policy outcomes. Am. Econ. Rev. 94, 25–45. doi: 10.1257/000282804322970689

Peters, B. G. (2000). Policy instruments and public management: bridging the gaps. J. Pub. Admin. Res. Theory 10, 35–47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024265

Pollitt, C. (2007). The new public management: an overview of its current status. Administratie si Management Public 8, 110–115,

Pollitt, C. (2013). Context in public policy and management; the missing link? Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Pollitt, C., and Bouckaert, G. (2017). Public management reform: A comparative analysis into the age of austerity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Powell, G. B. (2000). Elections as instruments of democracy: Majoritarian and proportional visions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Powell, G. B. Jr. (1982). Contemporary democracies: Participation, stability and violence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Pressman, J. L., and Wildavsky, A. (1973). Implementation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Quimpo, N. G. (2007). The Philippines: political parties and corruption. Southeast Asian Affairs, Vol, 2007 277–294. doi: 10.1355/SEAA07N

Rainey, H. G., and Steinbauer, P. (1999). Galloping elephants: developing elements of a theory of effective government organizations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 9, 1–32. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024401

Ramay, S. A., and Babur, A. (2020). Characteristics of Chinese governance model. In Sustainable Development Policy Institute, Governance and development model of China. Islamabad, Pakistan: Sustainable Development Policy Institute Press. Available at: 2–9. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep29104.4

Rheinstein, M. (1954). The constitutional bases of jurisdiction. University of Chicago Law Review, 22, 775–824.

Riker, W. H. (1980). Implications from the disequilibrium of majority rule for the study of institutions. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 74, 432–446. doi: 10.2307/1960638

Sabatier, P. A. (1986). Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: a critical analysis and suggested synthesis. J. Publ. Policy 6, 21–48. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X00003846

Salamon, L. (2002). The tools of government: A guide to the new governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sayre, W. S. (1958). Premises of public administration: past and emerging. Public Adm. Rev. 18, 102–105. doi: 10.2307/973789

Schedler, K., and Proeller, I. (2007). Public management as a cultural phenomenon: revitalizing societal culture. Int. Pub. Manag. Rev. 8, 186–194,

Schracter, H. L. (1989). Frederick Taylor and the public administration community. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

Scott, W. R. (1987). The adolescence of institutional theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 32, 493–511. doi: 10.2307/2392880

Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and Organizations: Ideas and Interests,. 3rd Ed. Sage Publications, Los Angeles, CA.

Scruggs, L. A. (1999). Institutions and environmental performance in seventeen Western democracies. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 29, 1–31. doi: 10.1017/S0007123499000010

Shepsle, K. (1979). Institutional arrangements and equilibrium in multidimensional voting models. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 23, 27–59. doi: 10.2307/2110770

Small, M. L. (2011). How to conduct a mixed methods study: recent trends in a rapidly growing literature. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 37, 57–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102657

Steiner, J. (1971). The principles of majority and proportionality. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 1, 63–70. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008942

Stoker, G. (2006). Public value management: a new narrative for networked governance? Am. Rev. Pub. Admin. 36, 41–57. doi: 10.1177/0275074005282583

Streeck, W., and Thelen, K. (2005). Introduction: institutional change in advanced political economies. in Beyond continuity: institutional change in advanced political economies. Eds. W. Streeck and K. Thelen (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press), 1–39.

Symonds, P. M., and Ellis, A. (1945). The case study as a research method. Rev. Educ. Res. 15, 352–359. doi: 10.2307/1168314

Terry, L. D. (1999). From Greek mythology to the real world of the new public management and democratic governance (Terry responds). Public Adm. Rev. 59, 272–277. doi: 10.2307/3109958

Tigno, J. (2017). Beg your pardon? The Philippines is already federalized in all but name. Pub. Pol. J., XVI–XVII, 1–14.

Tsebelis, G. (1995). Decision making in political systems: veto players in presidentialism, parliamentarism, multicameralism and multipartyism. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 25, 289–326. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400007225

Van Riper, P. P. (1987). “The American administrative state: Wilson and the founders” in A centennial history of the American ad- ministrative state. ed. R. C. Chandler (New York: Free Press), 3–36.

Waldo, D. (2007). The administrative state: A study of the political theory of American public administration. London, UK: Routledge.

Wallace, S. C. (1941). Federal Departmentalization: a critique of theories of organization. New York: Columbia University Press.

Wallace, S. S., and Kaufman, H. (1960). Governing new York City: Politics in the Metropolis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Wanna, J., Ayres, R., Head, B., and Mercer, T. (2021). Public policy theory, practice and skills: advancing the debate. in Learning policy, doing policy: Interactions between public policy theory, practice and teaching. Eds. T. Mercer, R. Ayres, B. Head, and J. Wanna. 1st ed (ANU Press), 311–330. Canberra, Australia: ANU Press.

Weill, R. (2023). War over Israel’s Judicial Independence. VerfBlog. Available at: https://verfassungsblog.de/war-over-israels-judicial-independence/

Wolf, C. (1979). A theory of nonmarket failure: framework for implementation analysis. J. Law Econ. 22, 107–139. doi: 10.1086/466935

Wollmann, H. (2003a). Evaluation in public sector reform: Trends, potentials and limits in international perspective. in Evaluation in public policy reform. Ed. H. Wollmann (Cheltenham: Cheltenham/Northampton, England: Edward Elgar Eward Elgar), 231–259.

Wollmann, H. (2003b). Evaluation in public-sector reform: Concepts and practice in international perspective. Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Wright, D. S. (1975). Intergovernmental relations and policy choice. Publius 5, 1–24. doi: 10.2307/3329348

Keywords: political executive, institutionalism and institutions, public management, state structure, comparative politics

Citation: Singh V (2024) Role of institutions in public management: developing case studies for divergent policy systems. Front. Polit. Sci. 6:1258811. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2024.1258811

Edited by:

Wenfang Tang, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ChinaReviewed by:

Anthony Costello, Liverpool Hope University, United KingdomErnesto Vivares, Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences Headquarters Ecuador, Ecuador

Marc Jacquinet, Universidade Aberta, Portugal

Copyright © 2024 Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vaishali Singh, dmFpc2hhbGlAeGltLmVkdS5pbg==

Vaishali Singh

Vaishali Singh