- 1Department of Peace and Conflict Studies, Fourah Bay College, Freetown, Sierra Leone

- 2Training Department, Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Center (KAIPTC), Accra, Ghana

In the last decade, West Africa has experienced increased activities by Jihadist groups, especially after the fall of the Muammar Qaddafi regime in Libya in 2012. The activities of these groups have gradually spread in the region, with countries such as Mali and Burkina Faso experiencing continued attacks. Taking the current socio-economic, religious and political context of Senegal into consideration, this study interrogates the factors that have so far prevented attacks by Jihadist groups in Senegal, the role that women and youth could play in mitigating jihadism in Senegal, and how the existing social capital in the country, could be further mobilized to foster trust building and social cohesion, thereby enhancing the prevention of violent extremism in the country? Furthermore, the study explores the need for a regional approach in dealing with the existing and emerging threats posed by Jihadist activities in the region. Methodologically, this study uses interviews and Focus Group Discussions to collect primary data from government officials, academics, civil society and international development partners. Secondary data from a wide range of sources are used to analyze the case of Senegal.

Introduction

The 11 September, 2001 attack on the United States of America (USA) by al-Qaeda drew global attention to terrorism and Jihadism. The ensuing Global War on Terror (GWOT) launched by the administration of the then president John Walker Bush, had global consequences, with groups such as the al-Qaeda spreading their influence beyond the Middle East and Asia, in retaliation to the military operations by Western governments. While terrorist activities were on the rise globally prior to the 9/11 attack, there were minimal experiences of it in Africa, prior to the attacks on the US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania on 7 August, 1998. The Arab Spring and the consequent overthrow of the regime of Muammar Qaddafi in Libya in 2011, further exacerbated Jihadist activities, particularly in North Africa and the Sahel. Countries such as Mali and Burkina Faso are among the worst affected, with others such as Côte d'Ivoire experiencing intermittent attacks.

This study is focused on Senegal, which shares borders with conflict-stricken regions of Mali. While Mali and other countries in the region have been affected by violence related to Jihadism, Senegal has so far not experienced any Jihadist attack. This does not negate the fact that there are Jihadist operatives in the country. However, it is notable that state tactics to identify and arrest them have been yielding positive results. Despite its steadfastness, Senegal still faces a persistent terror threat due to its regional position as well as internal economic and political topography. Taking the current socio-economic, religious and political context of Senegal into consideration, this study examines critical questions such as: what has so far prevented attacks by Jihadist groups in Senegal? What measures have the state and its partners been using, to prevent Jihadist activities in Senegal? Has the country learned from the experiences of other countries in relation, and used those experiences to shape its policy approach to prevention? What risks do geography pose to Senegal, in relation to Jihadism? What role could youth play in enhancing the efforts toward the prevention of Jihadists' attacks in Senegal? How could the existing social capital in the country be further mobilized to build trust and social cohesion, thereby enhancing the prevention of violent extremism in the country?

The study is divided into eight sections. Section 2 presents a conceptual background to the spread and effects of Jihadism in West Africa; Section 3 examines the state's approach to the prevention of jihadism in Senegal; Section 4 analyses the vulnerability gap among youth in Senegal and the potential for its exploitation by jihadist groups; Section 5 interrogates the question of geography and the threat of Jihadism in Senegal; Section 6 examines the resilient factors that have prevented violence related to jihadism in Senegal; Sections 7, 8 provide reflections on policy interventions and the conclusions of the study.

Methods

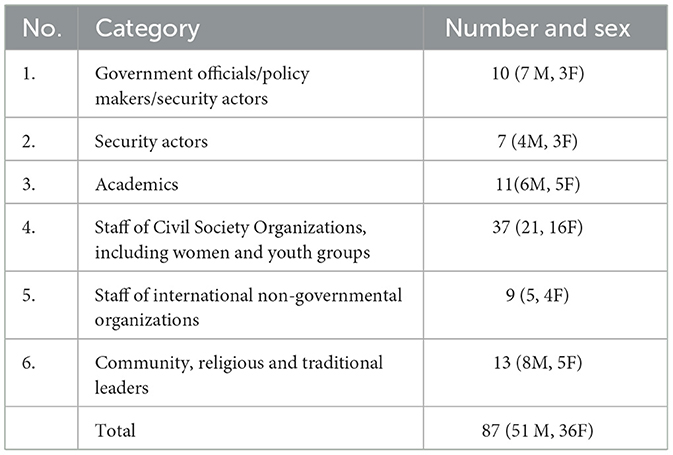

The study used a qualitative approach through semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGD) to collect data from 87 respondents (51 males and 36 females) in the capital city Dakar, and the regions of Kédougou and Tambacounda. The Kédougou and Tambacounda regions were included in the study because of their proximity to the conflict regions of Mali. They are also resource rich in gold, making them more vulnerable to attacks by Jihadist groups. Whereas, Dakar is the seat of the central government and a cosmopolitan city with people from diverse backgrounds and cultures. Collectively, the locations studied present a rich list of respondents engaged between March and May 2023. The categories, numbers and gender of the respondents are presented in below Table 1.

These actors were specifically selected as a result of their work on issues related to security, peacebuilding and social cohesion, all geared toward the prevention of violent extremism in Senegal. Thus, both purposive and snowballing sampling techniques were used to identify them. At the start of the study, an actor mapping exercise was conducted by the authors during the desk review, to have a clear picture of respondents to engage in the study. The study was conducted, with the support of two research assistants (one male and one female) based in the Kédougou and Tambacounda regions respectively. It was initially envisaged that there were going to be challenges in collecting data given the sensitivities involved with the topic, but that was not the case, as all the respective actors were willing to participate in the study, and provide the required data. Different questions were developed for each set of respondents, to ensure that the right set of data was collected from them. The Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) tool was used to analyzed the data, and the themes that the data was categorized into, helped to enhance the analysis of the data, and the also formed the respective sections of the paper. The themes include the context of Senegal, the state's approach to prevention, vulnerability gaps among Senegalese youth, geography and the potential for Jihadism, and social capital, trust building and prevention. The themes that have to do with geography, and social capital trust and prevention emerged from the data collected, and were interrogated, to have a nuanced understanding of how they could be understood and explored to strengthen Senegal approach to preventing violent extremism within its boundaries.

Conceptual overview

This section examines some of the key concepts examined in this article, and provide reflections on their relevance to the case of Senegal.

In defining the term Jihadism and the current understanding of its use, Hamid and Dar (2016, p. 1) state that:

Jihadism is driven by the idea that Jihad (religiously-sanctioned warfare) is an individual obligation (fard ‘ayn) incumbent upon all Muslims, rather than a collective obligation carried out by legitimate representatives of the Muslim community (fard kifaya), as it was traditionally understood in the pre-modern era. They are able to do this by arguing that Muslim leaders today are illegitimate and do not command the authority to ordain justified violence. In the absence of such authority, they argue, every able-bodied Muslim should take up the mantle of Jihad.

Global experiences abound point to the conclusion that jihadist groups use violence as a means of expression and pursuing their objectives. Over the years, Jihadism has been used interchangeably with terms such as “violent extremism” and “terrorism.” This interchange fundamentally stems from the fact that violent extremist groups in Africa deliberately infuse religion as a means of recruiting, radicalizing and deploying their members, and through their actions, cut across the blurred lines that distinguish Jihadism and terrorism. According to the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, terrorism involves “the intimidation or coercion of populations or governments through the threat or perpetration of violence. This may result in death, serious injury or the taking of hostages” (Office for the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2023: 1). In describing violent extremism, Koser (2015, p. 1) states that broadly speaking, it refers to “supporting or committing ideologically motivated violence to further social, economic or political objectives.” Koser further states that, it is broader than terrorism, as it “incorporates advocating, preparing and supporting violence, in addition to perpetrating it” (Koser, 2015, p. 1).

Inexperience in dealing with violent extremist groups in West Africa led to the use of a largely militarized approach by affected states in combating the threats. However, this approach has proven to be ineffective as it further pushes communities to accept extremist groups. Heavy handed and militarized tactics by security actors in countries such as Mali, Burkina Faso and Nigeria, marked by human rights violations and state orchestrated violence have undermined citizens' confidence and trust in them. Even after close to two decades of dealing with Jihadist activities in the region, not much has changed, as states appear to be more reactive rather than being proactive in dealing with Jihadist activities.

This article focuses on the need for a public policy approach in Senegal that focuses on strengthening preventing the spread and potential violence of Jihadist groups in Senegal. Prevention in this article speaks to the approaches or steps, beyond security measures, that should be taken by the state, to ensure that Senegal does not experience the presence, spread and consequent violent acts of jihadist groups in the country. These steps as argued throughout the article, should be grounded on an integrated human security approach, that is centered on factors such as good governance, addressing the vulnerabilities of women and youth, and having them at the heart of prevention efforts. Central to this process should be a people-centered and community focused approach that identifies and report potential threats or concerns to state authorities. Authors such as Skoczylis (2015) have argued that prevention strategies rely on local communities and the trust in the police and other state authorities, to succeed. This is in line with the arguments made in this article.

It is worth noting that countries such as the United Kingdom (UK) have undertaken specific prevention programmes (Home Department, 2011) that have proven to be effective in preventing subsequent attacks after the 7 July, 2005 terrorist attacks in London. The UK's approach to prevention is part of its wider counter-terrorism strategy, which is based on four Ps, prevent, pursue, protect and prepare (Home Department, 2011) of which prevention is a principal component.

While the UK has to a large extent succeeded in its approach to prevention and the use of the four Ps, countries such as Nigeria continue to struggle, because of trust deficit between local communities and security actors. Additionally, the conditions, such as bad governance, poverty, and the socio-economic marginalization of youth, women and minority groups, that allowed for the emergence and spread of Boko Haram, persist (Murtala, 2020). Furthermore, Knoechelmann (2014) states that other factors undermined Nigeria's approach to prevention, which include the government perception of the group being exclusively an ideological group “disregarding the ethnical background of the group,” and the “indiscriminate violence” against innocent civilians (Knoechelmann, 2014, p. 3). The experience of Nigeria, provide vital lessons on the adoption by African countries of public policy approaches, used by other countries outside of the continent, and the contextual realities and challenges that they are faced with. From this study, it was observed that most of the countries that have policies related to jihadism, are those that are currently experiencing it. Most of the countries in coastal West Africa, do not have such policies, as is the case of Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and the Gambia. Importantly, based on interviews conducted for this study, policy makers in countries such as Senegal are largely not familiar with the Prevent Strategy of the UK and other similar policies. Thus, this study argues that there is the need for them to interrogate such policies, with the aim of learning from them, and using good practices from their implementation, to prevent jihadist activities in Senegal.

Jihadism in coastal West Africa: spread and effects

During Muammar Qaddafi's 42-year reign in Libya, Islamist groups were forced underground, fled into exile, or faced imprisonment as the regime clamped down, arrested and jailed their members (Mezran, 2021). However, the political landscape in the country changed following Qaddafi's capture in October 2011. In the resulting power vacuum, several factions contended for the right of the legitimate use of violence. Additionally, the Western backed transitional council headed by Mustafa Abdul Jalil that was installed in 2011, and the government that succeeded it in 2012 (The Guardian, 2011) were weak and unable to stabilize the country. Islamist groups resurfaced and now occupy, a diverse ideological spectrum, ranging from advocates of democracy to extremist factions affiliated with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. Since then, Islamist extremism or radicalization has been spreading across the Sahel and reaching coastal West Africa, with significant effects across the region.

The rise of Jihadism in Mali can be traced back to the aftermath of the Libyan civil war in 2011, which resulted in the proliferation of weapons and fighters across the Sahel region and into Mali, mainly through countries such as Algeria and Niger that border Mali. Both countries have also been battling with violent extremist groups for years. The weakening of the Malian government and the proliferation of arms created an environment for Jihadist groups to exploit existing grievances, such as political instability, marginalization of certain ethnic groups, and economic challenges (Shaw, 2013). Over the past decade, violent extremism has been responsible for instability, violence and humanitarian crises, thus posing threat to the security and stability of coastal West African countries.

Key among the groups that are posing significant threat in West Africa are the Jama'at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM), the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Boko Haram and the Islamic West African Province (ISWAP) (Bangura and Mbawa, 2023). The expansion of Jihadist groups, such as Boko Haram and ISWAP from northeast Nigeria, where they originated, has spread to West African countries such as Niger, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, and has had a massive impact in the region (Aduloju et al., 2014). Forming alliances with local extremist groups has facilitated the spread and operations of groups such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in the region. This has partly been fueled by religious and ethnic dynamics; the region is home to diverse ethnic and religious communities, and Jihadist groups have exploited existing tensions among them to gain support and recruits (Ibrahim, 2017). These groups use a religious ideology that calls for the establishment of an Islamic State, based on their extremist interpretation of Islam and a rejection of Western education and ideologies. This ideology has resonated with some marginalized groups such as youth, women and people living in remote and isolated communities that are mostly cut off from the presence of the state. Socioeconomic factors including poverty, unemployment and a lack of fundamental services such as healthcare and education have also contributed to the spread of Jihadism in coastal West Africa. Violent extremist groups have managed to attract recruits, especially among the youth who are vulnerable to radicalization, by promising economic opportunities and social justice (Ibrahim, 2017).

The effects of Jihadism in coastal West Africa are ongoing and have been detrimental to the affected areas. Jihadist groups have carried out a range of violent attacks, including bombings, assassinations, and abductions (Bangura and Mbawa, 2023). Targeting civilians, government institutions and security forces has led to displacement, widespread fear and suffering among local populations, killing and disruption of economic activities, thereby undermining stability and development in the region. By seeking to expand their networks and establish links with other extremist groups in the Sahel and beyond, the spread of Jihadist groups also has regional and international security implications. This has raised concerns about the potential spillover effects and exportation of extremism and terrorism to neighboring countries (Lacher, 2012). To address and prevent this threat in West Africa, alliances and initiatives have been established. For instance, the Accra Initiative, which consists of Benin, Burkina Faso, Togo, Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire was established in 2017, and is anchored on “three pillars: information and intelligence sharing; training of security and intelligence personnel; and conducting joint cross-border military operations to sustain border security” (Kwarkye et al., 2019). The G5 Sahel was created “to address the everyday challenges of terrorism and transnational organized crime among the five member states (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger)” (Edu-Afful et al., 2022). The Accra Initiative has been mainly formal than operational, and contends with the financial challenges that limits its activities. Additionally, the G5 Sahel has also been contending with financial challenges, and political instability in the region. This has rendered the force less effective than it should have been.

Mali, Nigeria and Burkina Faso have longstanding conflicts between farmers and herders. The conflicts typically erupt from competition for scarce natural resources, such as land, water as well as issues related to ethnicity and livelihood. However, the conflicts have been exacerbated by the effects of climate change and a surge in population growth over the past 20 years. The latter has led to an increased need for arable land, resulting in farmers encroaching on protected land. In central Mali, northern Burkina Faso, and parts of Nigeria, violent extremist groups have exploited and conflated farmer-herder conflicts to foster recruitment and gain territory (Le Roux, 2019). The increase in violence has led security forces to intervene, and ironically, even though the majority of farmers/herders are not associated with Jihadist groups, they have been labeled as terrorists or insurgents by states simply because of their physical proximity to locations that are occupied by the groups.

The spread of Jihadism in coastal West Africa has complex and multi-faceted roots, fueled by religious, ethnic and socioeconomic dynamics. The violence, insecurity, humanitarian crises, erosion of governance, and regional security implications pose formidable challenges to the affected countries, and require comprehensive and coordinated efforts at local, regional, and international levels to effectively address the threat them, and even in cases where they are caught in areas captured by such groups.

While some of the factors that have been responsible for the spread of Jihadism in some of the countries examined above, do exist in Senegal, including poverty, unemployment, and the perception of the marginalization of youth, this study examines, Senegal has not experienced jihadism. This study draws on especially the situations in Mali, Burkina Faso and Nigeria, to interrogate questions on why Senegal has not experienced jihadism, while others have.

A reflection on an evolving context

On 1 August, 2023, two people were killed, with five injured, when an assailant threw a petrol bomb on a bus in the capital city, Dakar. The bus was attacked by youth, who robbed the money and items of the passengers (Africanews.com, 2023). This came in the midst of political tension and months of protests against the government for the arrest and detention of opposition leader Ousmane Sonko. While the government is claiming that this was a terror related attack, it is becoming apparent that the country's youth are becoming restive. Coupled with this, the emergence of street gangs, consisting mainly of youth, who feel marginalized by their state, and are seeking alternative means of expression, mainly through the association with, and the use of violence. The section on youth below, expands on their vulnerabilities, and how it could be exploited by Jihadist groups.

Over the years, religion has had a strong influence on the culture and traditions of a country with a population that is more than 90 per cent Muslim. As noted by Gierczynski-Bocandé (2007, p. 106) in a brief on Islam and Democracy in Senegal:

Religion holds an eminent position in Senegal, the crisis of the last decades having given a boost especially to Islam which ninety percent of the population of this west African country profess … Senegal's Sufism-oriented Islam is organized in brotherhoods with a dynastic and hierarchical order. Such a brotherhood is headed by a caliph who is succeeded by his brother or son. His regional and local representatives are called marabouts, and belonging to the family of a marabout may open many doors.

In the last decade and half, there have been emerging strands of Islam that seek to uproot the influence of the Sufist brotherhood in Senegal. As far back as 2003, Quinn and Frederick (2023, p. 89) wrote that:

Islam in Senegal is at the threshold of political change, as a shift in power takes place among the Sufi brotherhoods (tariqa). Within the next decade, the growing Mouridiya brotherhood, founded by Amadou Bamba (1850–1927), is likely to overwhelm its rivals, such as the Tijaniya, an outgrowth of a Sufi mystical movement led by El Hajj Umar Tall, and later led by the Wolof cleric, Malik Sy (c.1855–1922).

Sufism has been a controversial and usually misunderstood form of Islam, and as such has principals and traditions that are at odds with the views of modernists (Baldick, 2012). Similar to the arguments of Baldick, Heck (2007, p. 148) states:

Despite diverse expressions and modernist and reformist attempts to disassociate it from Islam, Sufism is the spirituality of Islam. Sometimes saint based, sometimes text based, it aims to bring the soul into relation with the sanctity of the other world, thus orienting it to divine truth. Sufism thus sees itself as the completion of Islam, its living embodiment, in contrast to legal formalism and theological scholasticism, but not in opposition to Muslim laws and doctrines. Its goal is sanctity, embodiment of the godly holiness described by the Qur'an.

The rivalry between Islamic sects, the decline in democracy, and the growing disenchantment among the youth, resulting from the negative perception of corruption among the political elites and the growing economic hardship in the country (Jusu and Sen, 2022), present opportunities that could be exploited by Jihadist groups, as argued throughout the article.

Examining the state's approach to preventing jihadism in Senegal

Although Senegal has not suffered direct attacks, like other West African countries, it is grappling with the influence and spread of a number of Jihadist groups. Among these groups is the Katiba Macina, which originated from Mali, and has been accused of establishing cells in Senegal. Additionally, Amadou Kouffa, a founding member of JNIM is leading one of the most active Jihadist armed groups in Mali today. Kouffa gained recognition in the late 2000s as an Imam in central Mali for his preaching and piety, and later turned toward radicalism, possibly after encountering Iyad Ag Ghali, through the local Tablighi Jama'at movement known as the Da'wa. Iyad Ag Ghali is the head of the Group supporting Islam and Muslims (GSIM); an alliance consisting of four al-Qaeda affiliates operating in Mali. Thus, he is the head of al-Qaeda in Mali (Oxford Analytica 2017). After establishing a base in Mali and exploiting the ongoing civil war in the country, the group gradually embarked on recruiting members in neighboring countries, including Mauritania and Senegal. As a result, regions such as Kèdougou and Tambacounda are facing direct threats as activities of jihadist groups encroach upon them (Toupane, 2021).

Aware of the increasing threat to their country, Senegalese authorities have been working on identifying and arresting people suspected of being either recruiters or members of cells established by Jihadist groups in their country. For instance, on 9 February, 2021, The Defence Post (2021, p. 1) reported that:

Gendarmes arrested four men in late January in the eastern town of Kidira, which lies on the border with Senegal's war-torn neighbor Mali, according to the Liberation newspaper. A shopkeeper who has been under surveillance for 2 years was among the men who were arrested, it added. The shopkeeper's telephone number reportedly appeared on a Whatsapp group linked to the Katiba Macina Jihadist group. Although he denies affiliation with the group, he is suspected of acting as a recruiter inside Senegal.

In addition to the above, the United States Department of States. (2021, p. 2) in its 2020 Country Reports on Terrorism states that:

At the end of 2020, Senegalese courts were considering at least three cases with possible terrorist links. One case involved a French National of Senegalese descent, also wanted by French authorities, who was apprehended while trying to depart Senegal with the suspected intent of fighting for ISIS. A second case involved a Senegalese national accused of threatening to blow up a Dakar French restaurant to protest the display of blasphemous images of the prophet Mohammed in France. The third case involved another Senegalese national arrested … he admitted that after traveling to several northern African countries to advance his Quranic studies he joined a Jihadist group in Libya and underwent accelerated training in military tactics. Additionally, Senegalese authorities arrested, detained, and deported a German terrorism suspect who was transiting through its international airport and was identified through an INTERPOL Red Notice.

The quotes above point to the risks Senegal is facing; and for which the country has been setting up military perimeters on its eastern borders to deal with the threats, whilst also working closely with “U.S. military and law enforcement officials to strengthen its counter-terrorism capabilities” The Defence Post (2021, p. 1). Alongside this, Senegal coordinates with its neighbors, mainly Mali and Mauritania on dealing with the threat of Jihadism. However, respondents noted that there is ineffective harmonization of efforts at the regional and sub-regional levels, when it comes to the implementation of frameworks developed to counter and prevent terrorism in Africa. Some of these frameworks include the ECOWAS Political Declaration and Common Position against Terrorism of 2013 and the Organization of African Unity's (OAU) Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism of 1999.

On 25 June, 2021, Senegal passed counter-terrorism laws. However, the laws were criticized by civil society actors, who argued that the they could be used to silence dissent. They have called for amendments to the laws in order to safeguard them from possible abuse by the government. As stated by Human Rights Watch. (2021, p. 2):

The laws define “terrorist acts” to include, among others, “seriously disturbing public order,” “criminal association,” and “offenses linked to information and communication technologies,” all punishable with life in prison. This vague definition could be used to criminalize peaceful political activities and infringe on freedom of association and assembly … The laws make it a criminal offense to “incite others” to perpetrate terrorism, but the laws do not define incitement, putting at risk media freedoms and freedom of expression by providing a potential basis for prosecuting free speech.

The review of the law during this study concluded that the fears of civil society is legitimate, as the provision are vague, and places significant powers in the hands of state authorities, who can abuse those powers. Coupled with this, the fear of the politicization and instrumentalization of the laws by the state to tighten its grip on power and limit the freedoms of civil society undermines public trust and confidence in them; and the consequent ability of the laws to make a difference in the prevention of Jihadist activities in Senegal. Thus, there needs to be a platform for the state and civil society to engage on reviewing the laws, with the aim of addressing the existing concerns, and having laws that will be of value to the state and its citizens, instead of backfiring on the state by fostering further marginalization and feelings of resentment amongst ordinary people.

It was observed based on interviews conducted with government officials that the approach to the Jihadist threat facing Senegal is mainly militarisation, which most of the non-state actors interviewed are against. The methods adopted that the government actors interviewed indicated include, Senegal having troops deployed in the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), increasing troop presence in the eastern borders, and investing in training of security sector actors on counter-terrorism measures. While these methods may be effective to some extent, they have their limitations, and may not necessarily prevent the recruitment of Senegalese into Jihadist movements.

The policy regime is weak on prevention, and it was observed during the study that the policy makers engaged during the study are not familiar with the prevention approaches used in other countries. In addition to this, the government itself has not focused on prevention, as stated throughout the paper. In interviews with state actors on the need for the government to adopt non-militarized approaches to preventing jihadism, and how the government could develop and roll them out, the majority of them indicated that they do understand the benefits of using broader approaches, encompassing civil society, but pointed at the need for resources to undertake such efforts. This argument was countered by non-state actors interviewed, as they stated that militarized approaches, are more costly. Most of the non-state actors interviewed, argued that with a good prevention approach, a militarized approach, will become less relevant. The non-state actors however, argued that there should be a dual approach used, as a balanced approach, will help to further prevent Senegal from attacks by jihadists in the future. This point was made by a respondent (male civil servant in Dakar, Interview 12):

The military approach is mainly used, because we believe that dealing with jihadist groups and preventing their activities, should include the military and the police. That is true, but that in some cases also undermine what we do. When there is a working relationship and a common understanding between civilians and security actors, it becomes easier to have civilians lead the process, and provide the required information and intelligence that is required to deny jihadist access to communities. We can have guns around, but the voices of the people, and their leadership is the most important of all actions.

A police officer (senior male police officer deployed in Kedougou: Interview 23) agrees with the point made by the civil servant, and he noted that there needs to be an urgent shift from a militarized approach, to an approach that integrates religious and community leaders, who are the gate keepers and opinion leaders in local communities. He argued that their buy-in, will make the work of the military and other security actors easier. The officer further noted that a militarized approach are usually not people friendly, and they push vulnerable people and communities, further into the hands of extremist groups, as is currently experienced in Mali and Burkina Faso. The comment of the officer was contested by two military officers in Kédougou and one police officer in Tambacounda, who stated that the activities of jihadist groups can only be contained or prevented by the use of force and military operations. They are of the opinion that civilians present risks to the collection and use of intelligence, and that they are untrained in identifying the threats posed by jihadist groups. The perception of the officers is problematic and depicts how some of them think, which affects the ability of the government to have a common approach that is human security based. It was observed that there were no known initiatives on the part of the security actors, that are centered on understanding the needs of the public, on how they could support prevention approaches.

The bus attack on 1 August, 2023, has left Senegalese concerned, with interviewees accusing the government of sending mixed messages on what happened. The government blames the opposition leader Ousmane Sonko, for the deteriorating security situation in the country, and points to the incident, as an act of terror, without accusing any terror related group in the region (Reuters., 2023). While the reasons for the attack remains unclear, banditry and the growing violence between the youth and state security actors have been pointed at by observers, as probably responsible for what happened on that day. Whatever the case maybe, most of the respondents stated that the attack provides an indication of the growing discontent in the country, and the potential for the rise of homegrown terrorism, if the socio-economic and political contexts are not improved.

In this study, most of the civilian respondents noted that that Senegal's approach to preventing violent extremism is largely ineffective, which most of the state actors disagree with. The reasons proffered by the non-state actors interviewed include, the lack of a human security-based approach that must address the vulnerabilities of the people, failure to involve religious, traditional, and community leaders, women and youth organizations, and networks developing and implementing preventative measures, as well as the perception of the politicization of laws used to prevent Jihadist activities (as noted above).

A respondent (female civil society activist in Dakar: Interview 09) had this to say:

The threat facing Senegal is grave. We fear that it is all a matter of time before we experience attacks. Jihadist groups have operatives all over the country, and Senegal is strategic for them, as it is a gate way to other countries in West Africa, and provides financial possibilities, and means of transferring funds, and also stable internet facilities for engagements. To deal with this threat, you need people, not only guns and bombs. People will provide the required intelligence, and will discourage their loved one and acquaintances from joining those groups. The government needs to change its strategy and focus on setting up systems in communities that will support its efforts, otherwise they will not succeed in stopping the activities of these groups.

Similar to the view of the CSO respondent referenced above, a (male former civil servant: Interview 08) stated:

Senegal should learn from other countries; the use of a militarized approach alone, will not succeed. For Jihadists to succeed, they need the people, if the people reject them, then there is no place for them to hide. In this fight, the most important actors are those in local communities, not the gendarmes or the military. The people need to see genuine efforts on the part of government to engage and work with them on preventing this menace that hangs over our heads.

Most of the state actors interviewed, argued that while there is more that could be done, Senegal is on the right track, and the fact that despite all that is happening in Mali, the country has remained safe. They further argued that people are always critical of what the government does, without seeking to understand what government is doing in preventing jihadism in the country. One of the respondents (female community leader in Kédougou: Interview 64), counter argued that, people criticize government because government does not engage or communicate to them, what they are doing. She stated that government should enhance its approach to communicating information that have to do with the security of the state, and should be seen proactively include civil society in the work that they do. The existing gap is leading to mistrust and suspicion on the part of the public, over the approach used by the government in preventing jihadism in Senegal.

Respondents also appeared to concerned over the potential of the government to use prevention of jihadism in the country, to clampdown on opposition and civil society. Thus, as indicated by majority of the respondents, it is essential that the government focuses on preventing violent extremism without using it as a means to suppress the oppositions and dissenting voices. The fear of potential abuse has eroded the trust of the people in its ability to address the threat. The respondents noted that the government should use a people-centered approach to preventing violent extremism, as that will build a collective approach, that is owned and led by citizens. They noted that the ability of a state to succeed in preventing violent extremism, depends largely on its people, especially its youth. The section below interrogates the vulnerability of youth and the challenges that that pose to the security of Senegal.

Youth and a “vulnerability gap” in Senegal

Like other countries in the region, Senegal has a very youthful population, with over 60 per cent of the population under the age of 25 (Borgen Project, 2019). It is worth noting that young people do not necessarily become violent as a result of lack of employment opportunities, but rather the lack of opportunities should be tied onto the broader frustrations that they also contend with in their society (Bangura, 2022). Often, factors such an unemployment, political marginalization and social disenfranchisement, mean that young people feel an acute lack of agency, identity, voice and recognition in their communities. Violent extremism, whether in the form of religious fundamentalism or political terrorism, can seem attractive for marginalized young people yearning for respect (Keen, 2002). The fear and intimidation that can be commanded through the barrel of a gun, then replaces the void of the “Waithood” of youth with purpose, and access to resources that they believe the state had previously denied them. The absence of the state in the lives of young people have negative physical and emotional impacts on them, thereby rendering them vulnerable and pushing them toward extremist ideologies (Bangura, 2022).

It was also observed during the study that religion has effects on the perception of some Senegalese youth, with some justifying the actions of even Al Qaeda and Islamic State linked groups in Mali and other parts of Africa. The link on religion is further exacerbated by the lack of economic opportunities, which leave them with the search for a source of hope.

It was deduced from interviews with members of youth organizations, and academics working on violent extremism, that the marginalization of youth renders them vulnerable to radicalization, with the draw of a seemingly higher calling described by respondents as “Doing God's work” and fulfilling “His purpose for them on earth” (Extracts from interviews conducted for this study). Works such as those by United Nations Development Programme (2017) and Zoubir (2017) have noted the connections between youth marginalization and violent extremism. According to majority of the respondents, the marginalization of youth, undermine their trust and confidence in the state, and pushes to search for alternatives to the state. They noted that this vulnerability is usually preyed on by violent extremist and terror related groups.

Majority of the youth respondents stated that over the last 20 years, there has been growing dissatisfaction among the youth of Senegal toward the government. The factors for such a relationship are attributed to the increased socio-economic and political marginalization, particularly among women and young people, in both rural and urban areas in Senegal.

Most of the respondents stated that, Senegal has, in the last two decades, experienced the departure of many youth from the country in search of greener pastures in Europe and beyond. Several have died trying to go through the Sahara Desert or crossing the Mediterranean Sea. In October 2020, over 140 Senegalese migrants died during a ship wreck as they tried to make their way to Europe (Peyton, 2020). The desperate drive to leave the country points to the effects of the economic hardship on the youth, and the failure of the state to address the challenges. As experienced in countries such as Nigeria, Mali and Burkina Faso, a vulnerable youth population presents a readymade army for jihadist groups, especially in this age of increased internet usage and social media.

Despite Senegal's reputation for upholding democratic and human rights standards, the country has witnessed a gradual decline in democratic governance over the past 15 years. This is laced with regular clashes between youth and opposition supporters and state security (Diop and Absa, 2021; Resnick, 2022). It was the desire to protect democratic freedoms and prevention of a breach of the constitution by the country's leaders that led to the emergence of groups like Y'en A Marre in 2012. Y'en A Marre was formed mainly by rap artists Thiat and Mallal Talla who had:

[c]leverly decided to tap into a hugely accessible and easy mode of communication and expression: music. They became the conscience of the state as politicians got trapped in a power struggle. Their interventions through music stimulated critical conversations and narratives against the drive by Wade and his allies to entrench their stay in power (Jusu and Sen, 2022, p. 87).

While groups such as Y'en A Marre have actively been combatting constitutional violations and safeguarding democratic progress in the country, the growing rate of unemployment has rendered young people vulnerable. As stated by Meribole (2020, p. 1):

Like many developing countries in Africa, Senegal's economy is growing. In fact, in 2018, the country's GDP increased by 6.766%. However, economic growth has not translated into more jobs for the younger generation, thus resulting in high youth unemployment. Young people either end up unemployed or in the informal job sector where wages are low …college graduates struggle to find jobs relating to their field of study. When looking for formal jobs, graduates face many difficulties, including a lack of connections and a failure to meet the job qualifications. Youths also lack the knowledge of where to look for formal jobs.

The economic hardship experienced in the country has effects on both youth in the rural and urban areas. The effects are worse for urban youth, due to the high level of rural-urban migration experienced in the country and the cities' limited resources and infrastructure to support such a rapidly growing urban population (Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation Development., 2023).

Given the limited opportunities available in rural areas, youth choose to migrate, particularly to the capital city Dakar with the hope of changing their economic circumstances. Their expectations are usually short lived, as they come to realize that Dakar does not necessarily present them with the envisaged opportunities. This point was also made by a respondent (youth activist in Dakar: Interview 17) “The situation in the villages is worse off for youth, and we have been running to Dakar, to live better lives. But Dakar is also a disappointment, and maybe a bigger disappointment than the villages, as we come here and get only pain and frustration at the end. That is why most young people want to leave the country.” Lacking the skills to compete for jobs, most youth end up in the informal sector (usually with low wages and with minimal labor protections), or subsequently become part of criminal networks as an alternative means of survival. Most of the female respondents stated that the socio-economic challenges are worse for women and girls, as they live in a patriarchal society, where their needs, wishes, voices and aspirations are not respected. As such, women and girls contend with multiple challenges, much more that the men and boys.

As early as 2013, the Voice of America (VoA) reported on a study conducted by Senegalese researchers with 400 respondents. The study concluded that a small percentage of Senegalese, some of them youth, support the actions of Jihadist groups in Northern Mali. The report (Voice of America., 2013, p. 1) stated that:

Researchers in Senegal say that despite the country's reputation for stability and religious tolerance, a small minority of Senegalese support last year's takeover of northern Mali by al-Qaida-linked Jihadist groups … the (Sufist) brotherhoods are no longer the solid ramparts against violence and extremism they once were … youth are looking for a religious model, and in particular something more modern, more open and more rational … the brotherhoods are functioning in such an outdated fashion that they are having trouble producing this discourse, which youth are instead finding in what are known as “reformist” movements.

Like the study mentioned earlier, this study also found that some respondents believe that some Senegalese individuals are becoming increasingly radicalized and aggressive compared to the past. The respondents noted that this change could be attributed to the messages conveyed by the political and religious figures in Senegalese society. Thus, youth are constantly challenging political leaders, and gradually questioning religious leaders, which was something that was deemed irreverent in the past. When questioned on the changes experienced among Senegalese youth, one of the respondents (female youth activist in Dakar: Interview 14) had this to say:

The systems and structures in our society do not favor young people and there is growing sense of radicalism in both rural and urban areas. The state is failing us, and at the same time, religion is becoming much more something to hold on to. The use of religion as a source of hope, is leading to youth wanting to reshape it to meet their spiritual needs. What we have in Sufism is seen to be soft and unfulfilling. Thus, there is an appeal for radical Islamism.

The appeal for a radical shift in the approach to Islam presents an opening that Jihadist groups are taking advantage of. An Islamic scholar in Dakar stated that “the existing gap has to be carefully examined by the government, to ensure that the right measures are taken to avoid their exploitation by jihadist groups.”

It was deduced from interviews conducted that both male and female youth are vulnerable and could be radicalized by Jihadist groups. Although there are no reported cases of women actively participating in Jihadist cells in Senegal, respondents indicated that women could easily be recruited and used by the cells, particularly if local communities buy into the ideologies of the groups. Most of the female respondents stated that efforts by the government, should include women leaders of diverse ages in prevention and early warning activities, as they could help to shape the approach, advocacy and messaging that could enhance prevention against jihadism in Senegal.

Geography and the threat of jihadism in Senegal

According to majority of the respondents engaged during this study; the threat of jihadism is much more imminent as a result of the geographical location of Senegal. Its proximity to Mali, which has become a hotspot for jihadist activities in the West Africa, makes Senegal especially vulnerable. Respondents indicated that there are close cross border and communal activities between regions bordering Senegal and Mali, and Senegal and Mauritania. With porous borders between these countries that are busy routes for informal transnational trade and livelihood, and have several unsecured crossing points, it becomes difficult to determine who is a jihadist or not. A respondent (female teacher in Kédougou, Interview 20) had this to say:

The daily cross-border activities by traders, aid workers, and other people make it difficult to determine how best to secure the border areas against the influx of Jihadists. There are marriages between community members in the border areas of Mali and Senegal, and as such we live under constant fear that one day our communities will be attacked. There is high military presence, but that is not much as sometimes we hear the fighting going on across the border and we get very worried. We have refugees from Mali, and we cannot send them back, but truly sometimes we are not even sure of who they are.

While the proximity of Senegal to Mali renders the country vulnerable to potential attacks, what makes the situation much more precarious, as stated by most respondents, is the fear of the exploitation of natural resources by Jihadists in the gold rich regions of Kédougou and Tambacounda to finance their activities. Some studies have already pointed to the risk of jihadist groups seeking to eventually control these regions in a bid to expand their activities in West Africa (Toupane et al., 2021). In Burkina Faso, Jihadist groups have stolen approximately $140 million from raiding gold mines since 2016 (Alternative Africa., 2020). Thus, it is important to carefully investigate the activities of Jihadists' cells in the regions, as their interests do not lie merely in the recruitment of potential members, but also in utilizing resources in the region to generate funds to finance their activities.

Respondents engaged in the Kédougou and Tambacounda regions noted that most of those involved in the collection of intelligence on suspected Jihadist operatives are members of the state security sector. They argued that those who are most important, including community stakeholders are left out of the process and that this needs to change, as the safety of their communities can only be enhanced by using an inclusive approach. It was observed from interviews and FGDs that communities in the regions visited, do not have much faith in the state security apparatus to combat the threat of jihadism in Senegal.

A critical point noted by security personnel interviewed in the Kédougou and Tambacounda regions, is that while some jihadists may be interested in attacking, or exploiting the gold rich regions, others are using Senegal as a gateway to other parts of West Africa and the Sahel. According to a respondent (male gendarme stationed in Kédougou: Interview 46):

Senegal appears to be serving several purposes for Jihadist groups, including using the country to travel to other parts of the world, and even the internet and communication services in the country to carry out their financial and other activities. It was to stop some of these activities that the anti-terrorism laws were passed. It is difficult to ascertain who a Jihadist is, that is why we need both artificial and human intelligence to combat this growing threat.

Senegal's proximity to both Mali and Mauritania, present the need for extra vigilance, with the country working with the government in those countries to collectively secure the border areas, and use proactive approaches in preventing and countering jihadist activities in their border areas. Both state and non-state actors interviewed indicated that local communities bordering, especially Mali and Mauritania, have a leading role to play in mitigating jihadist groups from using them, as hubs to carry out their activities in Senegal. This again reinforces the need for an integrated, human security and community-based approach to prevent jihadism in Senegal.

Resilient factors that have prevented violence related to jihadism in Senegal

A critical question that was examined in this study is: how has Senegal managed to prevent Jihadist attacks, despite the vulnerabilities and gaps related to the threat of Jihadism—unlike its neighboring countries like Mali, Burkina Faso and Côte d'Ivoire? The answers provided by respondents point at the existence of a strong and stable state, the influence of religion, family and cultural ties, and a sense of patriotism among Senegalese.

On the reference of a strong and stable state, most respondents argued that since independence, Senegal has enjoyed stability and democracy. The state has democratic institutions that have been largely functional, with democratic transitions taking place peacefully. The decline in democratic practices has been experienced only in the last decade, undermining relationship between the state and its youth, and other dissenting voices. Regardless of this, the Senegalese state is much more functional, unlike the experiences in Mali and Burkina Faso, which are currently have military regimes, with Mali contending with a full-blown civil war. As indicated by a respondent (male engineer in Dakar: Interview 37):

Senegal has been relatively stable since independence and we have managed to deal with our political challenges without resorting to military coups or outright instability. The country has also succeeded in preventing escalations beyond Casamance, a region that started the struggle for independence in 1982. Thus, there is limited fragility in the Senegalese system, unlike the cases of several other countries in West Africa. We pray that the current president will respect the call for a smooth transition after his term, as failing to do so will have implications for Senegal.

It appeared during the data collection process that Senegalese take pride in the country's history of smooth democratic transitions, with civic consciousness to challenge leaders who tend to stray from that path. This was the case of President Abdoulaye Wade in 2012, and also in the case of the incumbent President Macky Sall, when they were challenged by their people, to not breach the constitution, by seeking a third-term mandate, which would have eroded the democratic process in the country.

Tied to the above, most of the respondents that participated in this study, stated that there is a strong sense of patriotism among Senegalese, and they find it difficult to join external forces that have the intention of creating mayhem in their country. Majority of the respondents indicated that despite the economic hardship in the country, it will be difficult for Senegalese to knowingly accept foreigners or their nationals that are seeking to wreak havoc on the society. While this may be true, Jihadist groups have been able to use diverse methods to establish their networks and cells in several countries in the world, including Senegal. The use of religion as a tool for radicalization is very effective, and with time, locals come to recruit those within their societies. Thus, there are several other socio-economic and political considerations, such as poverty, marginalization and lack of access to social services, especially in the rural areas that should be addressed by the state to prevent Jihadist activities in Senegal. The current political climate in Senegal, and the uncertainty that clouds the upcoming elections in 2024, has the tendency of further undermining the trust of the youth and other demographics in it. The state should also work toward regaining their trust, as it will limit the potential for violent reactions against it, by its citizens.

In relation to the influence of cultural and familial ties, of the respondents noted that family elders have strong influence on the youth, and this tie has existed for centuries in their society. Thus, it becomes difficult for young people to think of involving themselves in violence, especially if that violence is not sanctioned by their elders. The bulk of the respondents indicated that Senegalese are generally peaceful, and families eat and pray together, which helps to deepens their bond. It is hard for youth, more so in rural areas, to break the cultural norms and ties that bind them. The seventeen per cent of the respondents, consisting mainly of state authorities, especially security actors indicated that while there is the perception that Senegalese youth are peaceful, youth have become much more confrontational, and suspicious of state authorities. This current relationship is expected, as youth have over the years felt marginalized and stereotyped by the state. The lack of platforms for engagement between the youth and elites, continue to deepen the negative perception between them.

It was observed during the study that while the practice and understanding of religion, especially Islam, is becoming contentious, with some youth questioning the influence of the Sufist brotherhoods, it still serves as a central rallying point for Senegalese. The bulk of Senegalese society depend on their religious leaders for spiritual support and guidance. This, however, presents both an opportunity and a risk. The influence of the religious leaders, could be used to prevent Jihadism, if they are given adequate support to develop counter-narratives and embark on prevention and advocacy campaigns. On the other hand, the emergence of radical sheiks with violent tendencies could lead to a shift in the Senegalese society. Some of the state officials interviewed during this study are concerned that the growing influence of radical sheiks pose significant security risk to the Senegalese society, and that the state should consider surveilling them, to assess whether they have connections with jihadist groups. Such a drive could be counter-productive, and lead to confrontations between clerics and the state. Despite the existing suspicious, religion is central to the stability of the country, and also presents a social capital, that could be used to further strengthen the approach to prevention in Senegal.

These points put forth by the respondents indicate the existence of social capital or resilient factors in Senegal that are essential to the prevention of jihadism in their society. If this social capital is harnessed through platforms for constructive engagement between youth and the elites, the tendency for jihadist groups to succeed in Senegal will be limited. Social capital is critical to the prevention of the involvement of youth in violence, and Bangura (2019) presented it as a critical factor that deterred Guinean youth from involving in the violence that ensured in the Mano River Basin between 1989 and 2010. Given the strong socio-cultural ties within the Senegalese society, it can be used as a prevention mechanism. The existing social capital could be mobilized, and supported to address the trust deficit within the Senegalese society. Authors such as Vuong et al. (2021) have argued that one of the most effective means of preventing terrorism is through trust building. The existence of trust between the government and the people, and social cohesion within communities, will strengthen Senegal's security and stability, thereby making it difficult for jihadist groups to penetrate and cause havoc in the country.

Policy reflections on preventing jihadism in Senegal

The respondents suggested that the Senegalese government has taken certain actions to prevent the spread of Jihadist cells and activities within its borders. These actions include continuing to strengthen Senegal's democratic good governance, and providing the platform for greater socio-economic opportunities and socio-political representation of youth, women, minorities and other vulnerable groups. Additionally they suggested that the government and its development partners should enhance the role of the media, civil society, and religious leaders in preventing violent extremism; develop strategies that promote community-driven resilience-building measures, with communities playing a leading role in preventing violent extremism; and the need for an integrated regional approach, with regional centers, and national centers that coordinate efforts with them (information and intelligence sharing).

All of the respondents indicated that the question of good governance is central to the prevention of jihadism, as the bulk of the respondents noted that the vulnerability experienced among young people could be attributed to their perception of corruption, socio-economic marginalization and their neglect by the state. Thus, they noted that the government should focus on addressing the existing gaps by providing medium and long-term socio-economic opportunities, especially to vulnerable youth and women. Majority of the respondents stated when interviewed that youth and women focused investments in education, agriculture, especially the value chain component, and career development in both urban and rural areas will go a long way in mitigating the involvement of youth in the activities of Jihadist groups. The perception of the involvement of the state in the lives of youth, will lead to the state gaining the trust and confidence of its youth, which is essential in mitigating Jihadist activities in the country. Tied to this, all the female respondents stated that, prevention initiatives should be gender responsive, with them tailored to mainstream women, and address the concerns of women and girls.

All of the point made above, underscore the need for a human security-based approach, alongside, a security-based approach, to preventing jihadism in Senegal. Security and intelligence actors need to work with civil society leaders and other stakeholders in communities such as women, young people, labor and agricultural unions, tradesmen as well as researchers and policymakers to develop and support early warning systems; and to enhance the effective functioning of the existing system. The establishment of such systems at the local and national levels, alongside activities that are aimed at reducing the vulnerabilities of youth and women will help build resilience that is normally lacking in the settings in which Jihadist groups thrive. However, initiatives developed have to be community-based, with feedback mechanisms established that will allow the relevant authorities to respond quickly and effectively. That said, for such initiatives to succeed, state security actors have to be trained on how to effectively work with communities and allowing the communities to own and lead the process. This will require political will, which could be mobilized during a genuine process of dialogue and engagement among national stakeholders.

Most of the respondents noted that working with communities will help to build the trust and confidence of community members in the process. In contrast, a militarized and heavyhanded approach by state security actors will only succeed in driving communities in the hands of Jihadist groups. Experiences of human rights violations and heavy handedness by state security actors in countries such as Nigeria (Amnesty International., 2023) have had negative effects on those states, examples that Senegal and other countries can learn from.

A proactive approach to prevention could be framed through working with religious leaders to identify the approaches that Jihadist groups use to recruit members and also the narratives they use for their radicalization. Religious leaders have a better grasp of the Quran, and can produce narratives that will create awareness in communities. Respondents noted that sermons by revered Imams are usually effective in passing messages among the respective demographics in Senegalese society. Thus, counter-narratives developed through a collaborative working relationship between the state, religious leaders and civil society could be used, especially during the Friday Jumma prayers.

Some respondents, mainly academics and civil society actors noted that the media houses in the country can be further utilized to strengthen public awareness on the prevention of violent extremism in Senegal. The media provides a wide-reaching platform, especially community radio stations, which are usually the only means of accessing news in remote and isolated communities. Messages and counter-narratives developed should also be disseminated through the use of social media, which both young and old people use in Senegal. Noting that Jihadist groups use social media to radicalize, in particular the youth, respondents argued that it could also be a good tool to discourage youth from joining them.

Finally, given the transnational nature of Jihadism and violent extremism in West Africa, there needs to be a much more proactive regional approach to countering and preventing them in West Africa. Senegal needs to be part of for instance, the Accra Initiative, and use that as a leverage to push for an effective approach to preventing the spread of extremist activities in its region. The country is in a difficult place, given its proximity to some of the hotspots in the region, Mali and Mauritania, and as such needs to work with regional bodies such as the African Union (AU) and ECOWAS to create specific regional and national centers to counter and prevent Jihadism. As stated by a security expert (male: Interview 29):

The most effective way of countering and preventing Jihadist operations in West Africa, is to have national and regional centers that will coordinate their activities and support response operations in each member state and across border areas. The national centers could link to the regional center, and the regional center can support operations and the collection, processing and dissemination of information and data related to Jihadist groups and their activities in the region. The center can work with academic and civil society organizations to have a holisitic and credible approach to dealing with the existing and evolving threat in the region.

The government of Senegal should promote an integrated approach to preventing Jihadist activities through working with academic institutions and think-tanks to ensure that policies developed are based on studies conducted. The use of evidence-based policies will yield better results as they will help Senegal to prevent the spread of Jihadism within its borders. Of relevance to this process, will be the integration of practitioners in the fields of peace, security and development. A collective approach will better shape the prevention and response to Jihadist activities in Senegal.

Conclusion

Since the fall of the Qaddafi regime in Libya, West Africa and the Sahel have experienced the spread of Jihadist movements, with countries such as Mali and Burkina Faso among the worst affected. Despite the proximity to Mali, coupled with the socio-economic challenges among youth and women in Senegal, the country has not experienced any violent attack by Jihadist groups. This study concludes that the reasons for factors such as the existence of a strong and stable state, the influence of religion, family and cultural ties, and a sense of patriotism among Senegalese, have so far prevented violent extremist attacks on Senegal. This however, does not negate the fact that Jihadist groups are present in the country and have active cells.

While Senegal has a strong Islamic culture and traditions, with the brotherhoods being a rallying source of unity in the country, there appears to be a growing disenchantment and even resentment among the youth of the brotherhood. In addition to this, the state is becoming much more repressive and democracy is on the decline in Senegal. This has led to frequent confrontations between the state, its youth and others with dissenting views. The resulting political tensions and instability present an opportunity for Jihadist groups to recruit and radicalize people. This could be seen with the 1 August, 2023 attack in Dakar, an example that others could follow.

The study also concludes that geography poses risks in relation to jihadism, as Senegal shares boundary with Mali. There are fears that Jihadist groups in Mali are using Senegal for resource mobilization, to finance their activities. Thus, the gold mines in regions close to Mali, are perceived by respondents, to be areas that are of interest to Jihadist groups in Mali, and could be targeted by the said groups.

Finally, the approach used by the state to prevent violent extremism and jihadism are mainly militarized, with the policy regime not focused on prevention so far. Additionally, it was concluded from the study that Senegal has not tapped into the experiences of other countries in relation to prevention. This gap needs to be addressed, if Senegal in mitigating any potential threat from jihadists. Furthermore, the government should promote democratic good governance, with basic social services provided across the country. Prevention initiatives should integrate and support youth to play a meaningful role in preventing jihadist activities in the country. Youth can undertake peer-to-peer education, and use popular arts used among others to create awareness on the prevention of Jihadism. The involvement of youth will be very effective, and will encourage their peers to join their efforts. Furthermore, Senegal should collaborate with ECOWAS and its other member states to establish a regional approach to preventing and countering violent extremism. The approach should aim at bringing together academics, policy makers and practitioners in the fields of peace, security and development to maximize the potential for a pragmatic and positive outcome. A successful approach to prevention could provide lessons for other countries in the region and beyond to learn from.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

This author contributed equally to the development of the manuscript. As such, the final product is owned by them all. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aduloju, A. A., Opanike, A., and Adenipekun, L. O. (2014). Boko Haram insurgency in North-Eastern Nigeria and its implications for security and stability in West African sub-region. Int. J. Dev. Conflict 4, 102–107. Available online at: http://www.ijdc.org.in/uploads/1/7/5/7/17570463/de2.pdf

Africanews.com (2023). Two Dead, Five Wounded in Senegal Bus Petrol Bomb Attack. Available online at: https://www.africanews.com/2023/08/02/two-dead-five-wounded-in-senegal-bus-petrol-bomb-attack (accessed January 10, 2024).

Alternative Africa. (2020). Jihadists Stole $140m Gold from Burkina Gold Mine Raids. Available online at: https://www.ocnus.net/artman2/publish/Africa_8/Jihadists-stole-140m-gold-from-Burkina-gold-mine-raids.shtml (accessed January 7, 2024).

Amnesty International. (2023). The State of the World's Human Rights-Nigeria. London, UK. Available online at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/location/africa/west-and-central-africa/nigeria/report-nigeria/ (accessed January 5, 2024).

Bangura, I. (2019). Resisting war: guinean youth and civil wars in the mano river basin. J. Peacebuild. Dev. 14, 36–48. doi: 10.1177/1542316619833286

Bangura, I. (2022). Youth-Led Social Movements and Peacebuilding in Africa. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003253532

Bangura, I., and Mbawa, H. (2023). “Emerging trends: DDR and countering violent extremism in Africa,” in Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration of Ex-Combatants in Africa, ed. I. Bangura (London: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781003390756

Borgen Project (2019). Top 10 Facts About Living Conditions in Senegal. Tacoma, Washington, USA. Available online at: https://borgenproject.org/tag/youth-population-in-senegal/ (accessed January 1, 2024).

Diop, B. B., and Absa, M. S. (2021). “Senegal: Impunity for Macky Sall's Regime Must End. Al Jazeera. Available online at: http://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/3/10/senegal-impunity-for-macky-salls-regime-must-end (accessed January 1, 2024).

Edu-Afful, F., Andrew, T., and Yaw, E. (2022). Shifting from External Dependency: Remodelling the G5 Sahel Joint Force for the Future. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2023). Poor Conditions are Causing Rural Exodus. Available online at: https://www.bmz.de/en/countries/senegal/social-situation-48600 (accessed January 8, 2024).

Gierczynski-Bocandé, U. (2007). Islam and Democracy in Senegal. 106–136. Available online at: https://www.kas.de/documents/252038/253252/7_dokument_dok_pdf_12801_1.pdf/f37cf0d6-9e1f-29b9-7e40-8cac2ba9ef47?version=1.0andt=1539671007056 (accessed January 10, 2024).

Hamid, S., and Dar, R. (2016). Hamid, Islamism, Salafism, and Jihadism: A Primer. Brookings Institute. Washington DC, USA. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2016/07/15/islamism-salafism-and-jihadism-a-primer/ (accessed January 10, 2024).

Heck, P. L. (2007). Sufism – what is it exactly? Relig. Compass 1, 148–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2006.00011.x

Home Department (2011). Prevent Strategy. The Stationery Office, Government of the United Kingdom, London. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a78966aed915d07d35b0dcc/prevent-strategy-review.pdf (accessed December 5, 2023).

Human Rights Watch. (2021). Senegal: New Counterterror Laws Threaten Rights. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/07/05/senegal-new-counterterror-laws-threaten-rights#:~:text=The%20laws%20make%20it%20a,basis%20for%20prosecuting%20free%20speech (accessed January 7, 2024).

Ibrahim, I. Y. (2017). The wave of jihadist insurgency in West Africa: global ideology, local context, individual motivations. West African Papers, No. 07, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Jusu, B. P., and Sen, S. (2022). “86 making change happen: music and youth-led social movements in Senegal,” in Youth-Led Social Movements and Peacebuilding in Africa (London: Routledge), 86–99. doi: 10.4324/9781003253532-6

Keen, D. (2002). Since I am a Dog, Beware my Fangs: Beyond a Rational Violence Framework in the Sierra Leonean War. Working paper for the Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, London School of Economics.

Knoechelmann, M. (2014). Why the Nigerian Counter-Terrorism policy toward Boko Haram has failed: A cause and effect relationship. Herzliya, Israel: International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT).

Koser, K. (2015). Explainer: The Fight against Violent Extremism. World Economic Forum. Davos, Switzerland. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/11/explainer-the-fight-against-violent-extremism/?DAG=3andgclid=Cj0KCQjwgLOiBhC7ARIsAIeetVCG6LQ2954_gy791lDPDHnEyEl4no0PgzgtwDN2sgjPbOEVc84OWBAaAqlOEALw_wcB (accessed January 10, 2024).

Kwarkye, S., Abatan, E. J., and Matongbada, M. (2019). Can the Accra Initiative prevent terrorism in West African coastal states? Institute for Security Studies. Available online at: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/can-the-accra-initiative-prevent-terrorism-in-west-african-coastal-states (accessed January 10, 2024).

Lacher, W. (2012). Organized Crime and conFlict in the Sahel-Sahara Region (Vol. 13). Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt6wpjcm.7

Le Roux, P. (2019). Responding to the Rise in Violent Extremism in the Sahel. Africa Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense Univ Fort Mcnair DC Washington, United States.

Meribole, J. (2020). Fighting Youth Unemployment in Senegal. Borgen Project. Washington, USA. Available online at: https://borgenproject.org/youth-unemployment-in-senegal/ (accessed December 5, 2023).

Mezran, K. (2021). Libya 2021: Islamists, Salafis and Jihadis. Washington, DC, USA: Wilson Center. Available online at: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/libya-2021-islamists-salafis-jihadis (accessed August 10, 2023).

Murtala, W. (2020). Challenges and prospects in the counter terrorism approach to boko haram: 2009–2018. Global Polit. Rev. 6, 40–56.

Office for the High Commissioner for Human Rights (2023). Terrorism and Violent Extremism. Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/topic/terrorism-and-violent-extremism (accessed April 29, 2023).

Peyton, N. (2020). Senegalese youth decry illegal migration after surge in deaths at sea. Reuters News Agency, New York, USA. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-senegal-migrants-trfn-idUSKBN27T2FY (accessed November 11, 2023).

Quinn, C. A., and Frederick, Q. (2023). Islam in Senegal: Maintaining A Delicate Balance, Pride, Faith and Fear: Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa. New York: Oxford Academic.

Resnick, D. (2022). Senegal's Democratic Backsliding Is a Threat to African Democracy. Foreign Policy. Available online at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/07/29/senegal-sall-democratic-backsliding-african-democracy/ (accessed November 13, 2023).

Reuters. (2023). Two burned to death in attack on Senegal bus. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/two-burned-death-attack-senegal-bus-interior-ministry-2023-08-01/ (accessed January 8, 2024).

Shaw, S. (2013). Fallout in the Sahel: the geographic spread of conflict from Libya to Mali. Canad. Fore. Policy J. 19, 199–210. doi: 10.1080/11926422.2013.805153